1. Introduction

Transvaginal ultrasonography is vital in modern fertility management, enabling the monitoring of uterine and ovarian physiological changes including follicular development, endometrial development, and blood flow during assisted reproduction techniques (ART). Three-dimensional ultrasonography using power Doppler angiography (3D-CPA) allows for the accurate measurements of endometrial volume and vascular parameters, including the vascularization index (VI) (indicating the number of blood vessels), the blood flow index (FI) (reflecting blood flow strength over time), and the vascularization flow index (VFI) (indicating the combined blood flow and vascularization in the region). Together, these parameters indirectly reflect endometrial and placental blood supply [

1].

Doppler technology can demonstrate fluctuations in blood supply that are related to hormonal changes during the menstrual cycle. This is done by means of color Doppler imaging. Previous reports noted a significant correlation between endometrial receptivity and endometrial vascularity and suggest that such observations help in the understanding of the factors that may aid embryonic growth and development [

2]. A study by Choi et al. showed that inadequate blood flow causes endometrial and sub-endometrial hypoxia thus lowering receptivity and reducing successful implantation as well as increasing spontaneous miscarriages [

3].

Modern lifestyles have meant that an increasing number of women delay having children. Increasing age at conception is thus now a critical risk factor for female infertility. While maternal age is widely recognized as a key factor in declining oocyte quality and an increased incidence of chromosomal abnormalities in both oocytes and embryos, all of which are associated with declining fertility, age-related changes in endometrial physiology and function may also significantly affect implantation and successful pregnancy rates, and overall female fertility [

4]. Research on endometrial physiology and function as it pertains to implantation and successful pregnancies is however limited. Investigating endometrial physiology and function could enhance our comprehension of endometrial aging from a biological and clinical perspective and perhaps pave the way for not only modifying these physiological changes to improve implantation and successful pregnancies but may allow for the possibility of investigating interventions that could reduce the risks associated with age-related female infertility. Doppler imaging allows a non-invasive means of studying endometrial vascular changes which can be considered as proxy to physiology and function. Previously we investigated endometrial vascularity in normally menstruating women and those in other physiological states using the same technology [

5]. The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of aging on the different ultrasound (US) parameters that we used in our previous study assess endometrial vascularity building on our findings and expertise [

5].

2. Methods

We previously published our methods in a cross-section study [

5] which will be briefly outlined here. As this was a retrospective study, consent was not required from the women (data were accessed anonymously). Approval for the study was obtained from the Feto Maternal Centre Institutional Review Board (IRB Ref No of FMC/IRB/003/23rd March 2023).

2.1. Experimental Design

This was a cross-sectional retrospective study of patients seen at our center between 2022 and 2023. All patients attending for gynecological consultation routinely have a transvaginal 2-D/3-D ultrasound scan for the assessment of the pelvis. At this procedure the endometrial vascularity is also obtained with power Doppler. All the imaging was performed by experienced clinicians. For the purposes of this study, we opted to review only the images from one (BA) of the consultants to minimise inter-observer variability.

The records of those who met the inclusion criteria were retrieved and various variables extracted. The inclusion criteria were (a) healthy women attending for gynaecological check-up, typically prior to embarking on pregnancy or undergoing ART, (b) between the ages of 20 and 50 years and having normal menstrual cycles (c) not on any hormonal treatment and (d) certain of their last menstrual period. The imaging performed by the consultant (BA) was with a General Electric (GE) Voluson 10 ultrasound machine using a 5-9mHz 3-D transvaginal probe. The wall filter was set at low and the pulse repetitive frequency (PRF) at 0.7. A longitudinal view of the uterus was obtained in 2-D. The 3-D program was then switched on, and an image obtained with the power Doppler mode on. A multiplanar image was generated and stored for later analysis.

2.2. Data Acquisition

Firstly, a truncated sector defining the area of interest was obtained with the volume mode on. The probe was next moved and adjusted, and the sweep angle set to 90° to ensure that a complete uterine volume encompassing the entire sub-endometrium was obtained [

5,

6]. The women were advised to remain as still as possible to minimize inappropriate movements of the transducer that would generate noise in the image during this period. A three-dimensional data set was next acquired using the medium speed sweep mode. The resulting multiplanar display was examined to ensure that the area of interest had been captured in its entirety with special attention paid to the coronal image in the C plane, specific to the 3-D ultrasound, which provides more spatial information than the transverse or longitudinal planes. The images were stored on the hard drive of the Ultrasound machine if the volume was complete with no artifacts, however, where artifacts were present or the image was judged to have failed pre-defined set criteria, imaging was repeated until satisfactory ones were obtained.

2.3. Data Analysis

A single operator (a technician within our team) retrieved and analyzed the stored 3-D images to generate the various variables studied. The Virtual Organ Computer-Aided Analysis (VOCAL

TM) program was used for the 3-D endometrial volumetric analysis. This program enables the use of a standard computer mouse to manually define the volume of interest as the data set is rotated about a central axis [

6]. Plane C (coronal image), obtained by rotating plane A (longitudinal plane) using the 9

O rotation step, was used for all the measurements which were made manually. Because the dataset is rotated by 180

O, the 9

O rotation makes available 20 planes to calculate individual volumes. This has been shown to represent the best compromise between reliability, validity, and time to define initial volume [

7].

After defining the endometrium, the power Doppler signal within it was quantified through the ‘histogram facility’ of the program, which employs specific mathematical algorithms to produce three indices of vascularity [

8] which are representative of either the percentage of power Doppler data within the defined volume (the VI; vascularization index), the signal intensity of the power Doppler information (the FI; Flow index) or a combination of both factors (the VFI; vascular flow index) and have been suggested as representative of vascularity and flow intensity [

9].

Table 1 shows the definitions of these indices. Following assessment of the endometrium, the sub-endometrium was then examined through the application of ‘shell-imaging’, which allows the user to generate a variable contour that parallels the originally defined surface contour. Shell-imaging was used in this study to define a 3-D region within 5 mm of the originally defined myometrial/endometrial contour and then the power Doppler signal within this sub-endometrial region was quantified. Although this is an arbitrary distance, it is one that reflects the inner third of the myometrium and the region supplied by the radial arteries [

10].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was done using SPSS 29.0.0.0. The data were de-identified before analysis. Patients were divided into 3 groups based on age. Group 1 (20-29 years), group 2 (30-29 years), and group 3 (40-49 years). Outliers, defined as those with values >2 standard deviations from the mean, were excluded from this analysis. The one-way ANOVA test was used to test for differences in the 6 main parameters: uterine volume, VI, FI, VFI, endometrial volume, and endometrial thickness between the age groups within each phase of the menstrual cycle. Student’s T test was used to test differences in the 6 parameters between the follicular and luteal groups. Results are presented as mean and standard deviation where data were normally distributed. The Kolmogorov Smirnov test was used to test for normality of data. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

A total of 907 women were included in the study—427 (47.1%) in the follicular phase and 480 (52.9%) in the luteal phase. There were 297 (32.7%) (131 follicular and 166 luteal) in the age group 20-29 years, 471 (51.9%) (240 follicular and 231 luteal) in the age group 30-39 and 139 (15.3%) (56 follicular and 83 luteal) in the age group 40-49. The variables studied were next analyzed based on age and the phase of the menstrual cycle.

3.1. Follicular Phase

Table 2 shows the mean parameters measured in the 427 women studied in the follicular phase. A one-way ANOVA was used to compare the means between the three different age groups. Age had a significant negative effect on the variables measured. The effect size was moderate for vascularization index (η² = 0.034), and vascularization flow index (η² =0.023), and mild for flow index (η² = 0.017). Age also had a significant effect on endometrial thickness, volume, and uterine volume. The effect size was moderate for endometrial thickness and volume (η² = 0.042 and 0.073), and strong for uterine volume (η² = 0.235).

3.2. Luteal Phase

Table 3 shows the mean parameters measured in the 480 women in the luteal phase. A one-way ANOVA was used to compare the means between the three different age groups. Age had no significant effect on the vascular indices (VI, VFI and FI) but had a significantly positive effect on endometrial thickness, volume, and uterine volume. The effect size was very mild for endometrial thickness and volume (η² = 0.01 and 0.02 respectively) and moderate for uterine volume (η² = 0.12).

3.3. Comparison of Follicular vs. Luteal

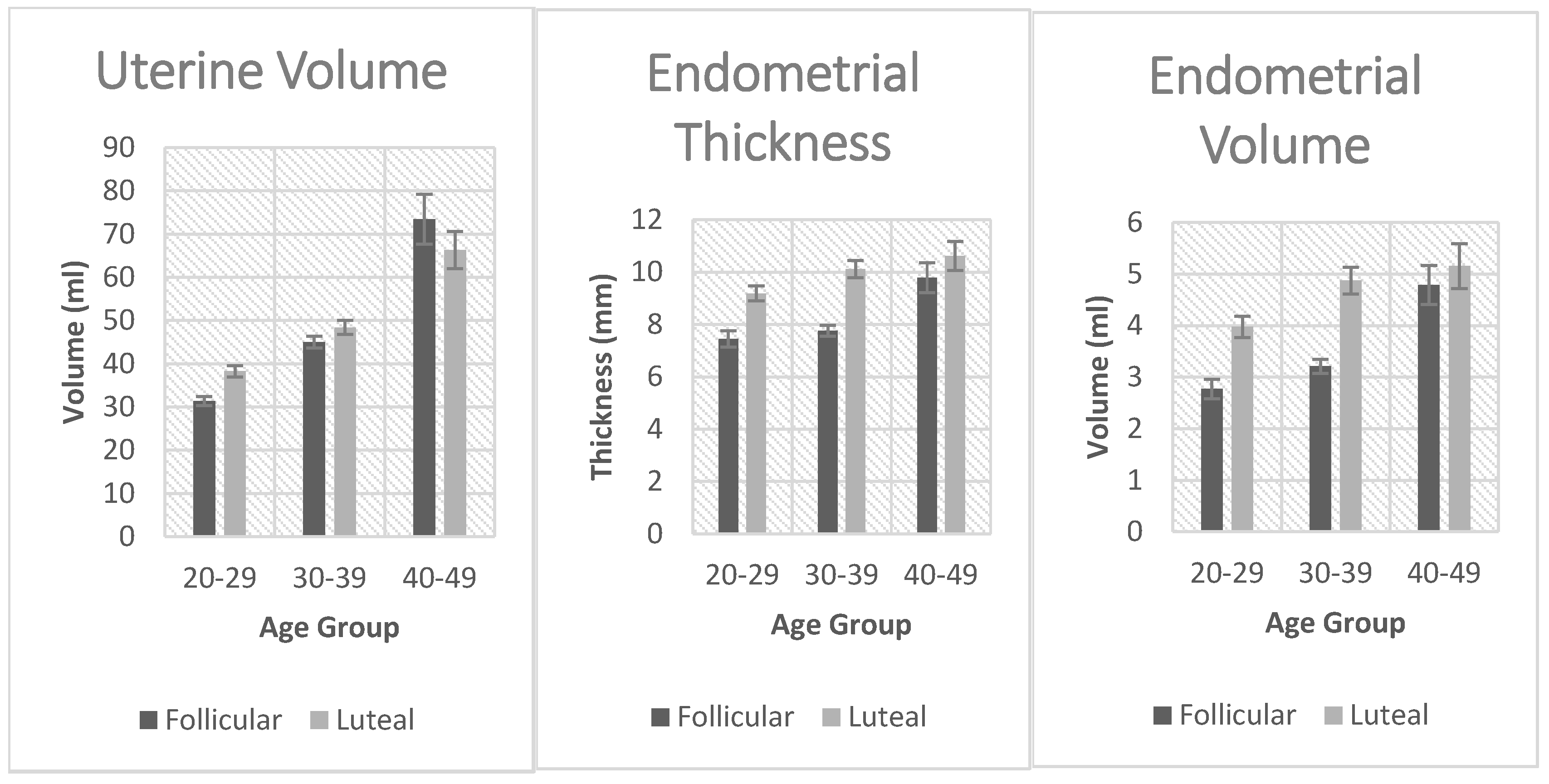

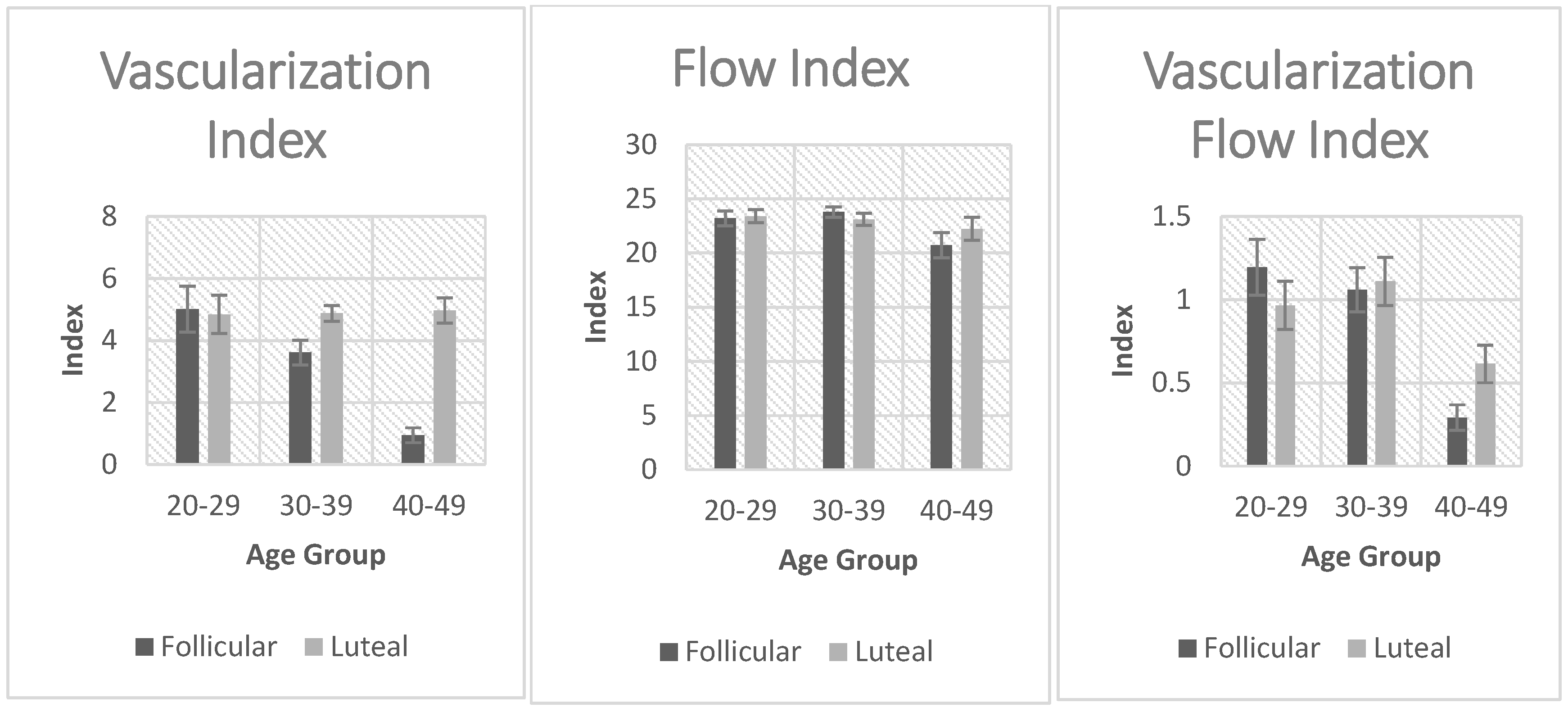

To compare the measured variables between the follicular and luteal phase groups, we used the Games-Howell post hoc test. This is a post hoc analysis method for making multiple comparisons among two or more samples. We used it because it does not assume equal sample sizes and variances among the studied groups. It is used to identify which groups are significantly different if the ANOVA test is significant. These comparisons are shown in

Figure 2. Uterine volume was significantly affected by age in both the luteal and follicular phases. There was a significant increase in uterine volume with age. Vascularization index was significantly decreased with age but only in the follicular phase. The same applied to the Flow index and Vascularization flow index. Endometrial thickness was significantly affected by age in the follicular and the luteal phases. Endometrial volume was also significantly affected by age in the follicular and the luteal phase.

Figure 1.

Comparison of vascularization index, flow index, and vascularization flow index between the follicular and luteal phase groups.

Figure 1.

Comparison of vascularization index, flow index, and vascularization flow index between the follicular and luteal phase groups.

4. Discussion

The main findings in this study were that age had a significant effect on all the variables (VF, FV, VFI, endometrial thickness, volume, and uterine volume) studied in the follicular phase. While all the vascular indices decreased with age, the measured dimensions (endometrial thickness and volume and uterine volume) increased with age. In the luteal phase, the vascular indices were unaffected by age, but the measured dimensions also increased with age.

Uterine ageing has not been very well-studied although described changes have been associated with abnormal hormonal levels that occur especially around menopause [

11]. Furthermore, endometrial ageing has been shown to negatively impact implantation, clinical pregnancy, and live birth rates. Our data show that age is associated with changes not only in the endometrial morphology (as measured by ultrasound) but also by its vascularity. Endometrial vascularity emerges as a crucial factor in successful implantation [

12]. In our data, vascularity diminishes with age, notably declining after 39 years, coinciding with a significant drop in implantation rates. In fact, the highest vascularity was observed in the 20-29 age group which is in general regarded as the age of optimum reproductive outcome [

13]. Recently, there have been some studies on the significance of age-related epigenetic alterations using the epigenetic clock to predict the biological age of the endometrium in certain endometrial disorders and in infertility [

4]. A combination of these and vascularity changes could have a compounding effect on reducing successful implantation rates with ageing.

The most notable morphological change in the ageing uterus is uterine collagen deposition. This is associated with chronic inflammation involving various mediators like interleukins, growth factors, oxidative stress products, and senescent cells. Estrogen plays a role in fibrosis and senescence activation through specific signaling pathways. Senescence is observed in the ageing uterus, resulting in cells with reduced proliferation. Studies in mice and humans have also shown that ageing is associated with changes in gene expression related to cell proliferation and the appearance of senescent cells. Endometrial cystic hyperplasia can increase uterine volume with age, while endometrial atrophy occurs in postmenopausal women. These changes are linked to poor reproductive outcomes, emphasizing the need to address uterine function and ageing before irreversible morphological changes occur. Our findings of the changes in uterine morphometry with age may be partly explained by these mechanisms [

11].

Our utilization of 3D Doppler ultrasound to elucidate the changes in the ageing endometrium was motivated by several factors. In recent years, there has been significant progress in the development of 3D colour Doppler ultrasound technology, marked by enhanced resolution and expanded capabilities for measuring parameters previously beyond reach. Furthermore, transvaginal ultrasound is unique as a noninvasive diagnostic modality. Lastly, the simplicity and cost-effectiveness of ultrasound measurements facilitate widespread applicability and generalizability.

Our findings of a significant increase in uterine volume with ageing is consistent with studies that have shown a peak in uterine volume at around 35-40 years, which then declines by 50-60 years [

14]. Uterine growth generally continues during the reproductive years and ceases at menopause, ultimately regressing in size to approximate its pubertal form. This direct correlation between age and uterine size/volume was observed in numerous other studies and may be attributed to the decrease in ovarian estrogen secretion that occurs with ageing. Studies have also shown a positive correlation between parity and uterine volume, which could also be an underlying factor that plays a role in increasing uterine volume [

15].

Endometrial volume was significantly affected by age in both the follicular and the luteal phases as seen in

Table 2 and

Table 3. Endometrial volume, often not previously well studied as a proxy for assessing endometrial receptivity, is increasingly being considered as a comprehensive marker of receptivity. Recent ultrasound advances have enabled research on its correlation with embryo implantation and indeed considering it a valuable marker for evaluating endometrial receptivity. Endometrial volume has been suggested as a potential predictor for successful

in-vitro fertilization (IVF), with a study using a 3.2 ml cut-off on the day of embryo transfer reporting 80% sensitivity and 77.1% specificity [

16]. Another study suggested endometrial volume as a promising alternative to using traditional thickness in predicting IVF success, revealing significant differences between pregnant and non-pregnant women on crucial treatment days [

17]. However, Boza et al., [

18] in their study of 142 patients contradicted this by showing that 3D transvaginal ultrasound-assessed endometrial volume was not a reliable predictor in single blastocyst embryo transfer cycles, with an AUC of 0.48. This discrepancy underscores the need for further research to establish a consensus on the efficacy of endometrial volume as a predictive marker in assisted reproductive technologies. In summary, while endometrial volume was unlikely to serve as a predictive factor for pregnancy, it is worth noting that patients with an endometrial volume less than 2.0–2.5 ml may experience a significantly reduced pregnancy rate [

19].

Endometrial thickness was also significantly affected by age in both the follicular and the luteal phases as shown in

Table 1 and

Table 2. This increase in endometrial thickness with ageing has also been observed in previous studies. One study noted that women aged 32–36 years and 37–45 years had a maximum thickness of 15.3mm and 15.9mm during the secretory phase, respectively, surpassing those of younger age groups (21–25 and 26–31 years) with a maximum thickness of 12.1mm and 13.4mm, respectively. However, the determination of the impact of age-related variations in endometrial thickness on pregnancy rates has not been conclusively established [

20,

21].

Statistically significant associations with ageing were observed for Flow index, Vascularization index, and Vascularization flow index, specifically in the follicular phase (as opposed to the luteal phase). This distinction was an intriguing and surprising observation. A separate study (Burger et al., 2008) showed that estradiol (E2) levels in the follicular phase were elevated in older women (>45 years) compared to younger women (20-35 yrs) [

22]. This was mainly explained through a hypothesis whereby the feedback mechanism controlled by inhibin B was affected earlier in life as compared to E2 secretion. Thus, with ageing, as follicle numbers decrease, inhibin levels decrease leading to increased FSH secretion. Over time, this will drive an increase in E2 levels and thus enhance endometrial growth. This hypothesis could possibly explain the discrepancy observed in the three ultrasound parameters (FI, VI, and VFI) between the follicular and luteal phases of these women [

22]. These ultrasound indices have been shown in studies to be a useful parameter in the prediction of pregnancy in frozen embryo transfer cycles [

23].

5. Conclusions

Our findings suggest a detrimental influence of ageing on endometrial biology. The findings demonstrate a correlation between uterine ageing and vascular and morphological changes and provides a possible explanation for diminished fertility with age. Insights into age-related alterations in endometrial vascularity, thickness, and volume enhance our understanding of factors impacting reproductive outcomes. However, the study’s limitations, such as its retrospective nature and clinic-specific focus, necessitate cautious interpretation. Further research is imperative to thoroughly investigate the intricacies of uterine ageing and its implications for female fertility.

6. Strengths and Limitations

A main strength of our study is the large number of patients involved. Furthermore, limiting the scanning to one clinician minimized inter-observer variability. Limitations to our study include its retrospective nature with well acknowledged shortcomings. Despite the removal of outliers, there were still some challenges, such as the use of anonymous data, potentially leading to information gaps. Variability among patients, both in medical history and demographics, may confound the study’s outcomes. The stringent inclusion and exclusion criteria, focusing solely on women undergoing routine ultrasound at one center, may limit the external validity of our findings.

Author Contributions

Justin C Konje and Ahmed Badreldeen conceived the idea. Both Badreldeen Ahmed and Justin Konje performed the ultrasound scan and contributed to writing the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors confirm that there are no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Tan, S.-Y.; Hang, F.; Purvarshi, G.; Li, M.-Q.; Meng, D.-H.; Huang, L.-L. Decreased endometrial vascularity and receptivity in unexplained recurrent miscarriage patients during midluteal and early pregnancy phases. Taiwan. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 54, 522–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, E.H.Y.; Chan, C.C.W.; Tang, O.S.; Yeung, W.S.B.; Ho, P.C. Endometrial and subendometrial vascularity is higher in pregnant patients with livebirth following ART than in those who suffer a miscarriage. Hum. Reprod. 2006, 22, 1134–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.J.; Lee, H.K.; Kim, S.K. Doppler ultrasound investigation of female infertility. Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. 2023, 66, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathare, A.D.S.; Loid, M.; Saare, M.; Gidlöf, S.B.; Esteki, M.Z.; Acharya, G.; Peters, M.; Salumets, A. Endometrial receptivity in women of advanced age: an underrated factor in infertility. Hum. Reprod. Updat. 2023, 29, 773–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, A.A.; Al-Motawa, A.; Halabi, N.; Ahmed, B.; Rafii, J.A.; Konje, J.C. An investigation of endometrial vascularity in normally menstruating women and those in other physiological states using 3D ultrasound imaging. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2024, 165, 1172–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raine-Fenning, N.; Campbell, B.; Collier, J.; Brincat, M.; Johnson, I. The reproducibility of endometrial volume acquisition and measurement with the VOCAL-imaging program. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2002, 19, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raine-Fenning, N.J.; Clewes, J.S.; Kendall, N.R.; Bunkheila, A.K.; Campbell, B.K.; Johnson, I.R. The interobserver reliability and validity of volume calculation from three-dimensional ultrasound datasets in the in vitro setting. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 21, 283–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pairleitner, H.; Steiner, H.; Hasenoehrl, G.; Staudach, A. Three-dimensional power Doppler sonography: imaging and quantifying blood flow and vascularization. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 1999, 14, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Järvelä, I.Y.; Sladkevicius, P.; Tekay, A.H.; Campbell, S.; Nargund, G. Intraobserver and interobserver variability of ovarian volume, gray-scale and color flow indices obtained using transvaginal three-dimensional power Doppler ultrasonography. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2003, 21, 277–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulletti, C.; Jasonni, V.M.; Tabanelli, S.; Ciotti, P.; Vignudelli, A.; Flamigni, C. Changes in the uterine vasculature during the menstrual cycle. Acta Eur Fertil. 1985, 16, 367–371. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S. Unveiling uterine aging: Much more to learn. Ageing Res. Rev. 2023, 86, 101879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sardana, D.; Upadhyay, A.J.; Deepika, K.; Pranesh, G.T.; Rao, K. Correlation of subendometrial-endometrial blood flow assessment by two-dimensional power Doppler with pregnancy outcome in frozen-thawed embryo transfer cycles. J. Hum. Reprod. Sci. 2014, 7, 130–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellieni, C. The Best Age for Pregnancy and Undue Pressures. Journal of Family & Reproductive Health 2016, 10, 104–107. [Google Scholar]

- Well, D.; Yang, H.; Houseni, M.; Iruvuri, S.; Alzeair, S.; Sansovini, M.; Wintering, N.; Alavi, A.; Torigian, D.A. Age-Related Structural and Metabolic Changes in the Pelvic Reproductive End Organs. Semin. Nucl. Med. 2007, 37, 173–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olayemi, O.; Omigbodun, A.A.; Obajimi, M.O.; Odukogbe, A.A.; Agunloye, A.M.; Aimakhu, C.O.; Okunlola, M.A. Ultrasound assessment of the effect of parity on postpartum uterine involution. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2002, 22, 381–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zollner, U.; Specketer, M.-T.; Dietl, J.; Zollner, K.-P. 3D-Endometrial volume and outcome of cryopreserved embryo replacement cycles. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2012, 286, 517–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maged, A.M.; Kamel, A.M.; Abu-Hamila, F.; O Elkomy, R.; A Ohida, O.; Hassan, S.M.; Fahmy, R.M.; Ramadan, W. The measurement of endometrial volume and sub-endometrial vascularity to replace the traditional endometrial thickness as predictors of in-vitro fertilization success. Gynecol. Endocrinol. 2019, 35, 949–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boza, A.; Oznur, D.A.; Mehmet, C.; Gulumser, A.; Bulent, U. Endometrial volume measured on the day of embryo transfer is not associated with live birth rates in IVF: A prospective study and review of the literature. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2020, 49, 101767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaman, C.; Mayer, R. Three-dimensional ultrasound as a predictor of pregnancy in patients undergoing ART. J. Turk. Gynecol. Assoc. 2012, 13, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ugwu, H.; Onwuzu, S.; Agbo, J.; Abonyi, O.; Agwu, K. Sonographic prediction of successful embryonic implantation in in-vitro fertilization and embryo transfer cycle procedures, using a multi-parameter approach. Radiography 2022, 28, 473–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y. The effect of endometrial thickness and pattern measured by ultrasonography on pregnancy outcomes during IVF-ET cycles. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2012, 10, 100–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burger, H.G.; Hale, G.E.; Dennerstein, L.; Robertson, D.M. Cycle and hormone changes during perimenopause. Menopause 2008, 15, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, V.V.; Agarwal, R.; Sharma, U.; Aggarwal, R.; Choudhary, S.; Bandwal, P. Endometrial and Subendometrial Vascularity by Three-Dimensional (3D) Power Doppler and Its Correlation with Pregnancy Outcome in Frozen Embryo Transfer (FET) Cycles. J. Obstet. Gynecol. India 2016, 66, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).