Submitted:

20 January 2025

Posted:

21 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Mathematical Model Formulation

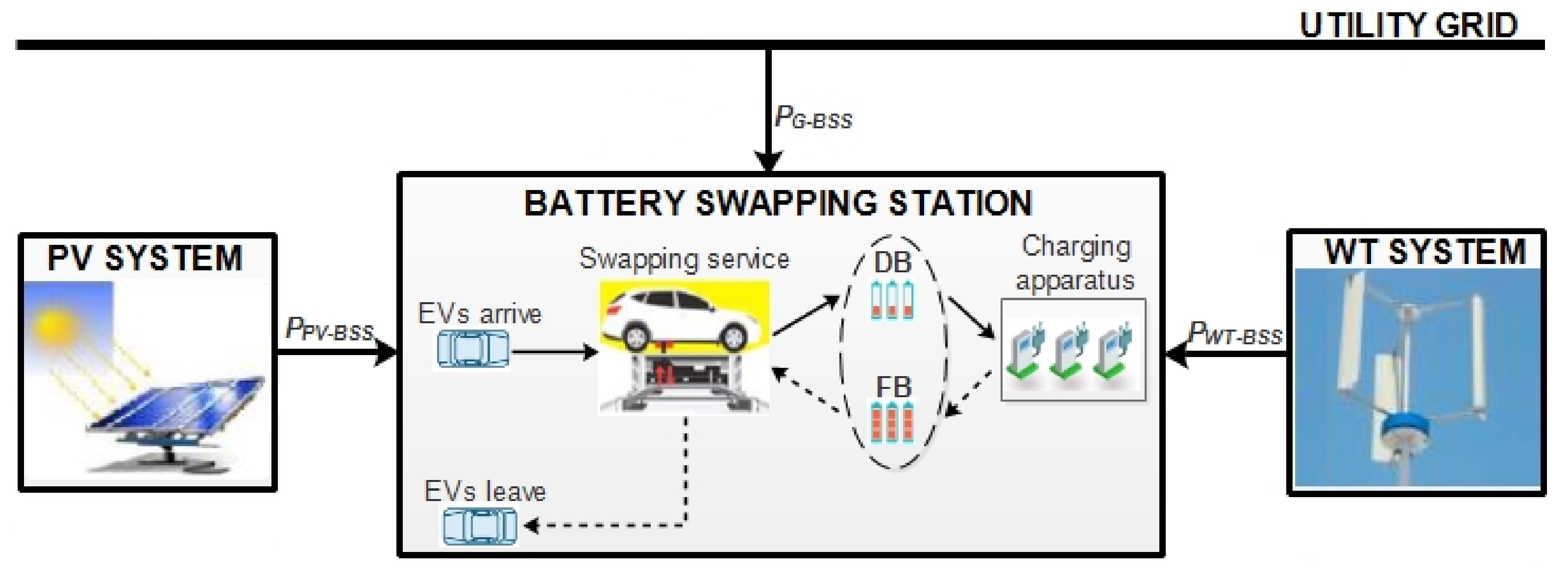

2.1. Schematic Model Layout

2.2. Sub-Models of the Proposed System Components

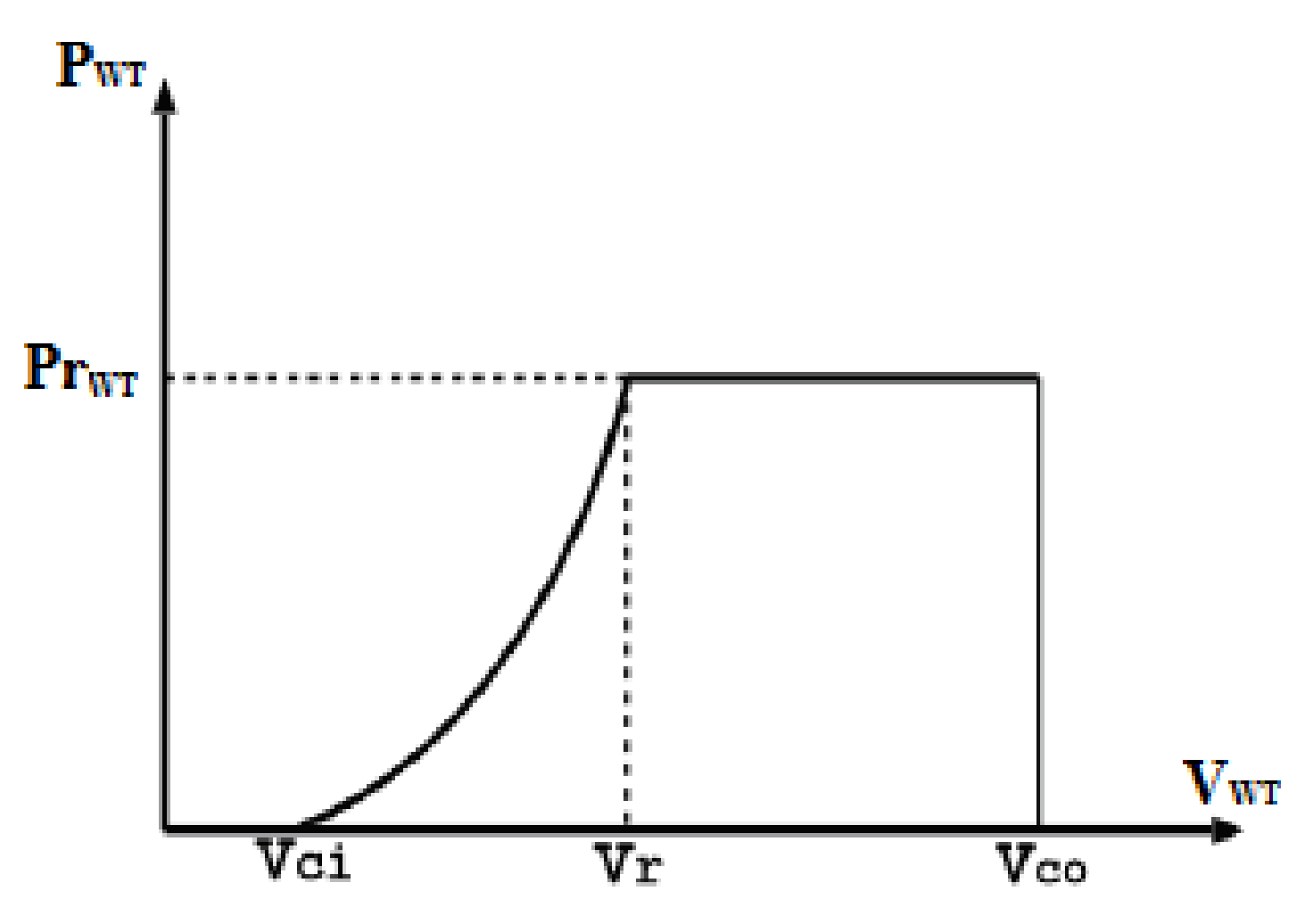

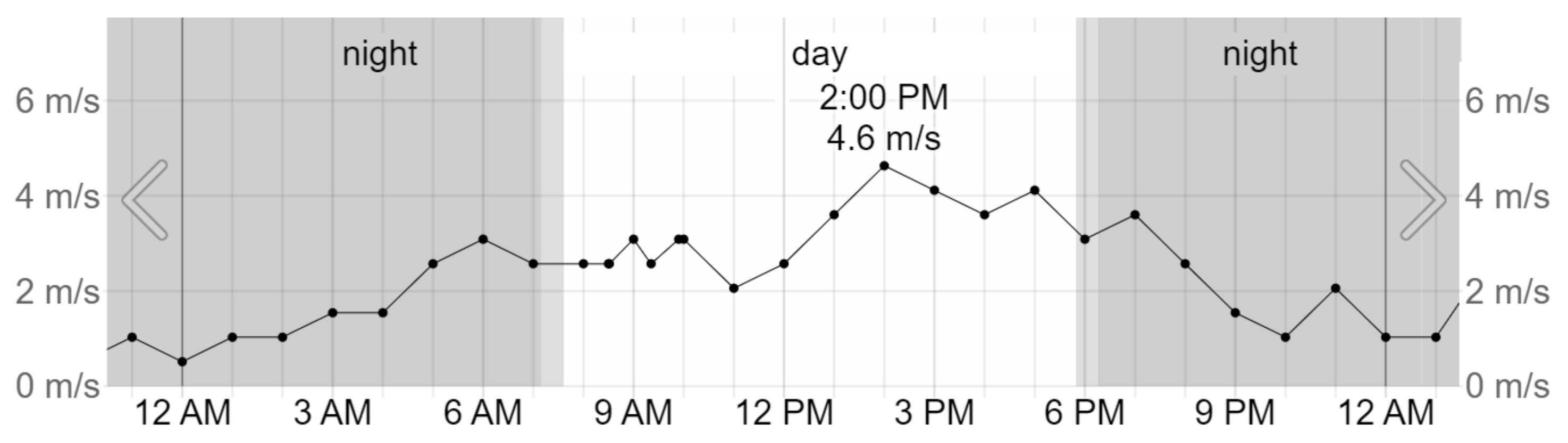

2.2.1. Wind Turbine System

2.2.2. Solar Photovoltaic System

2.2.3. Inverter

2.2.4. Utility Grid Power Supply System

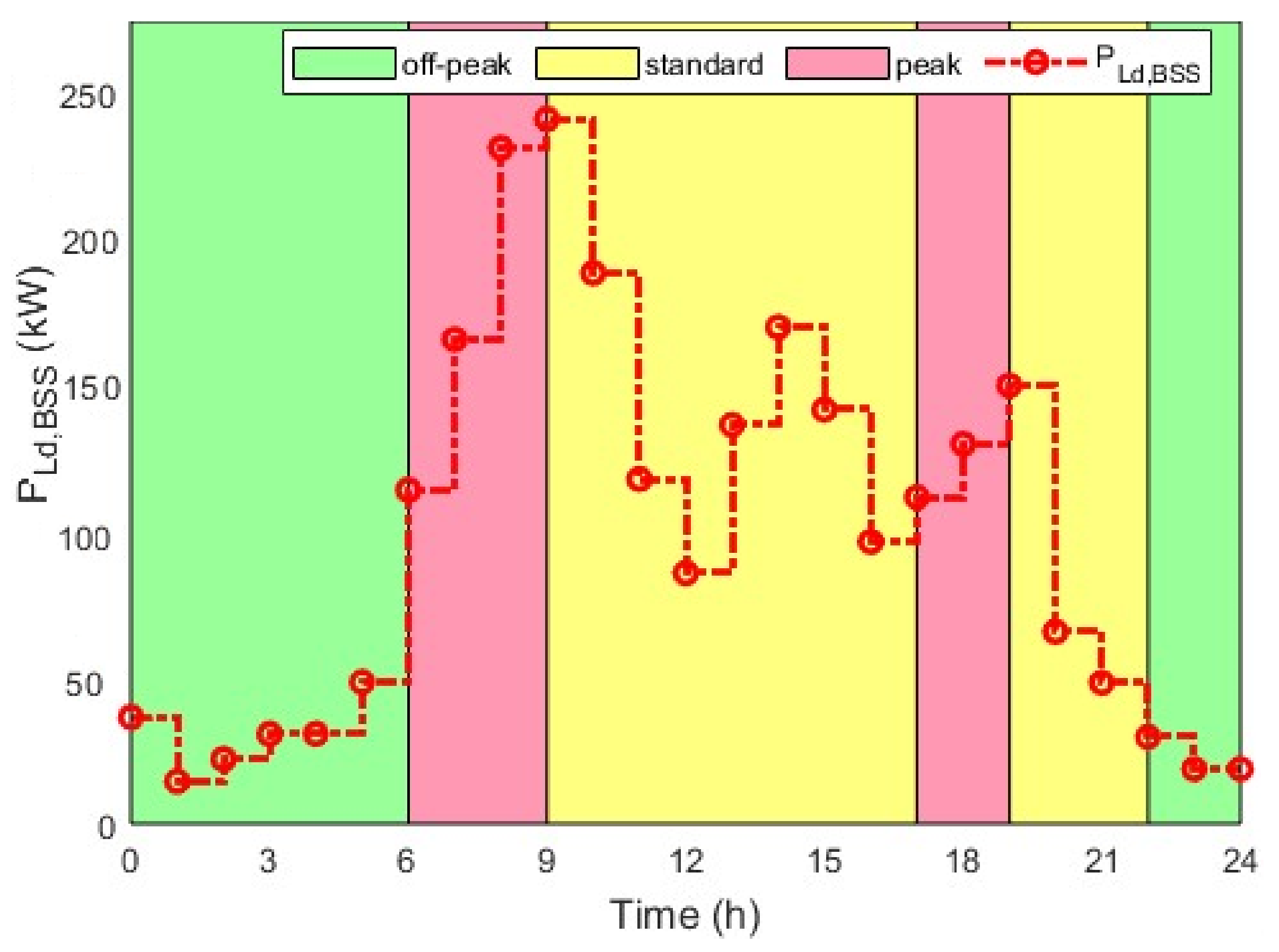

2.2.5. Battery Swapping Station Power Demand Mathematical Modelling

2.3. Technical and Economic Parameters of the Proposed System

2.3.1. Economic Evaluation Parameters of the Proposed System

- a)

- LCC of the wind turbine system

- b)

- LCC of the photovoltaic system

- c)

- LCC of the inverters

2.3.2. Reliability Consideration of the Proposed System

2.4. Optimisation Problem Formulation and Proposed Algorithm

2.4.1. Objective Function

2.4.2. System Constraints

2.4.3. Algorithm for Solving the Optimisation Problem

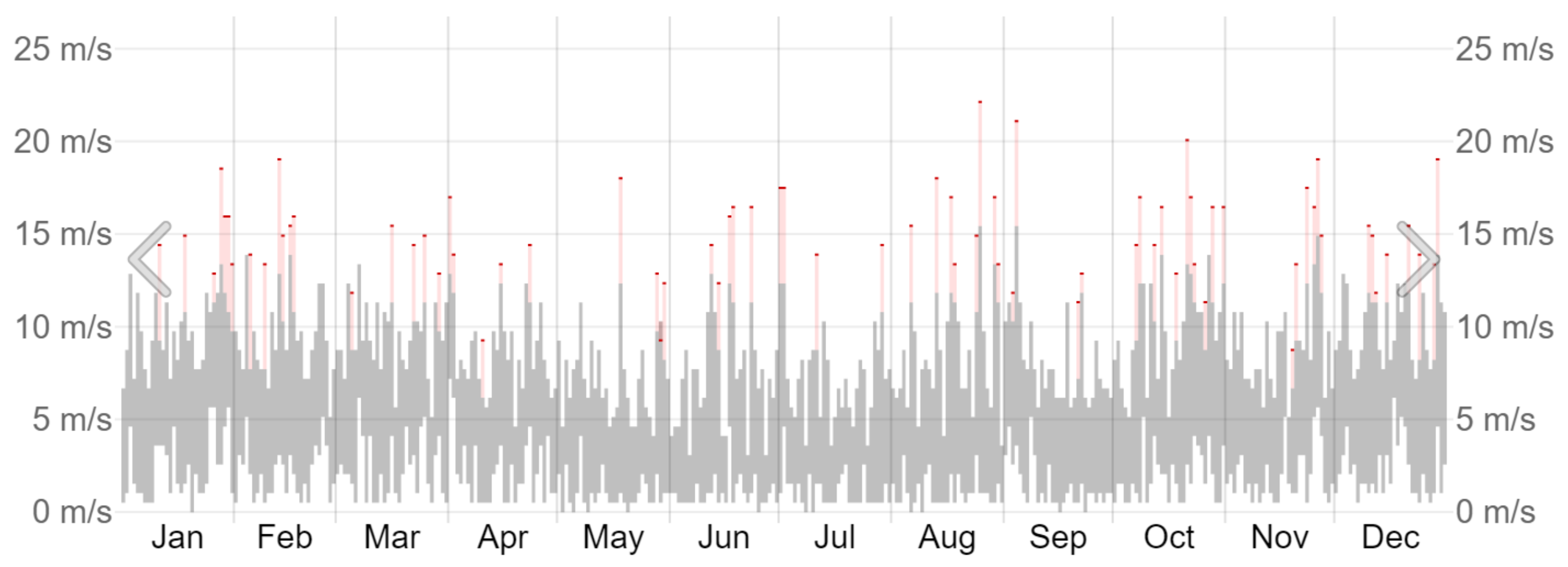

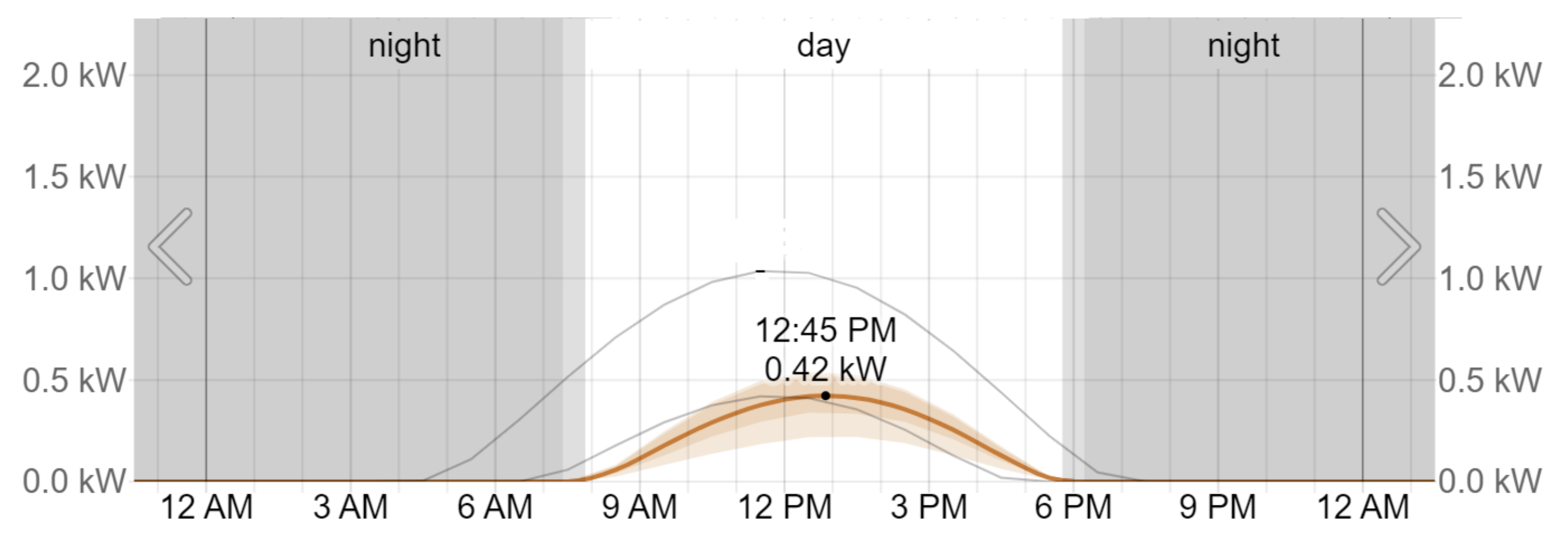

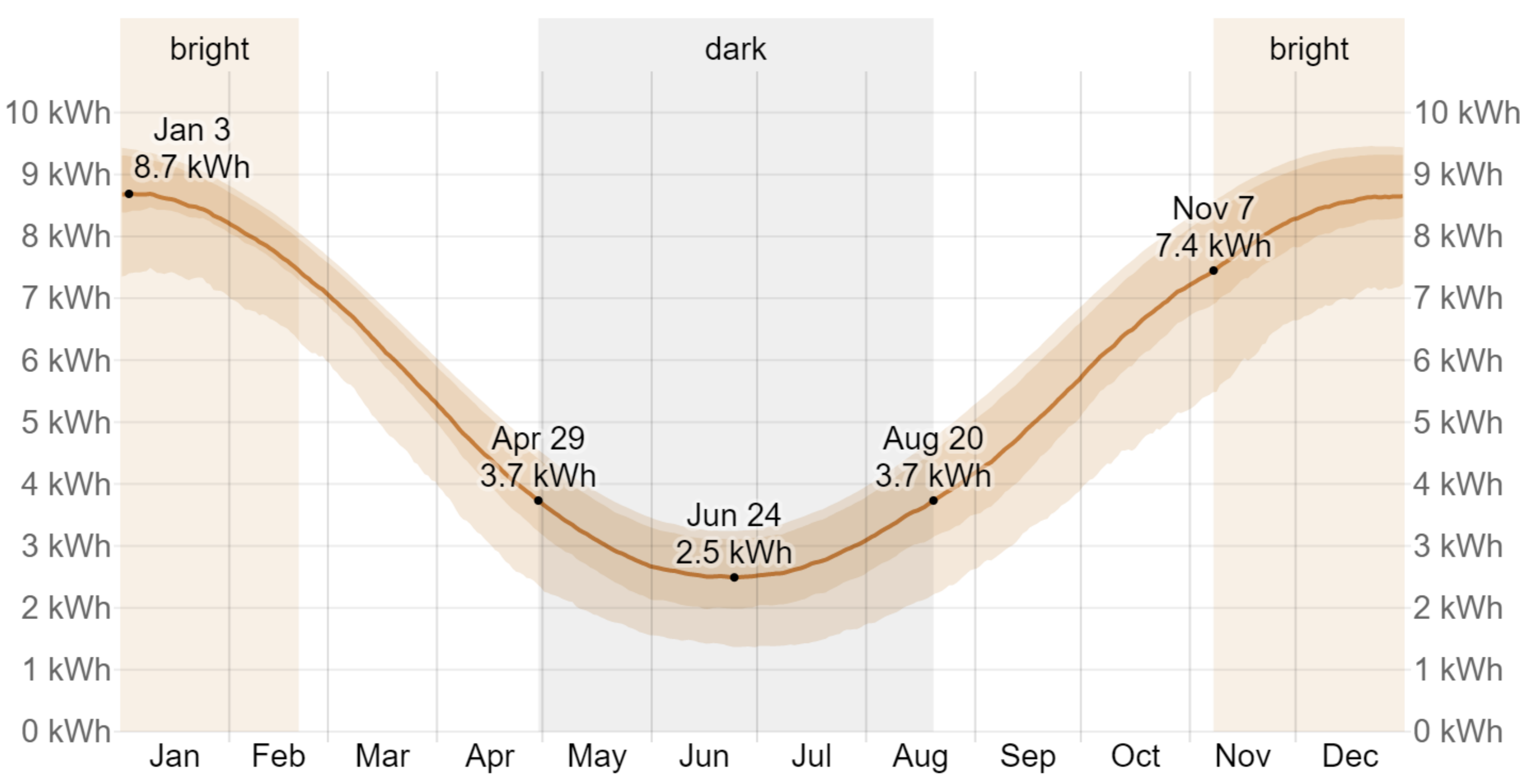

3. General Data

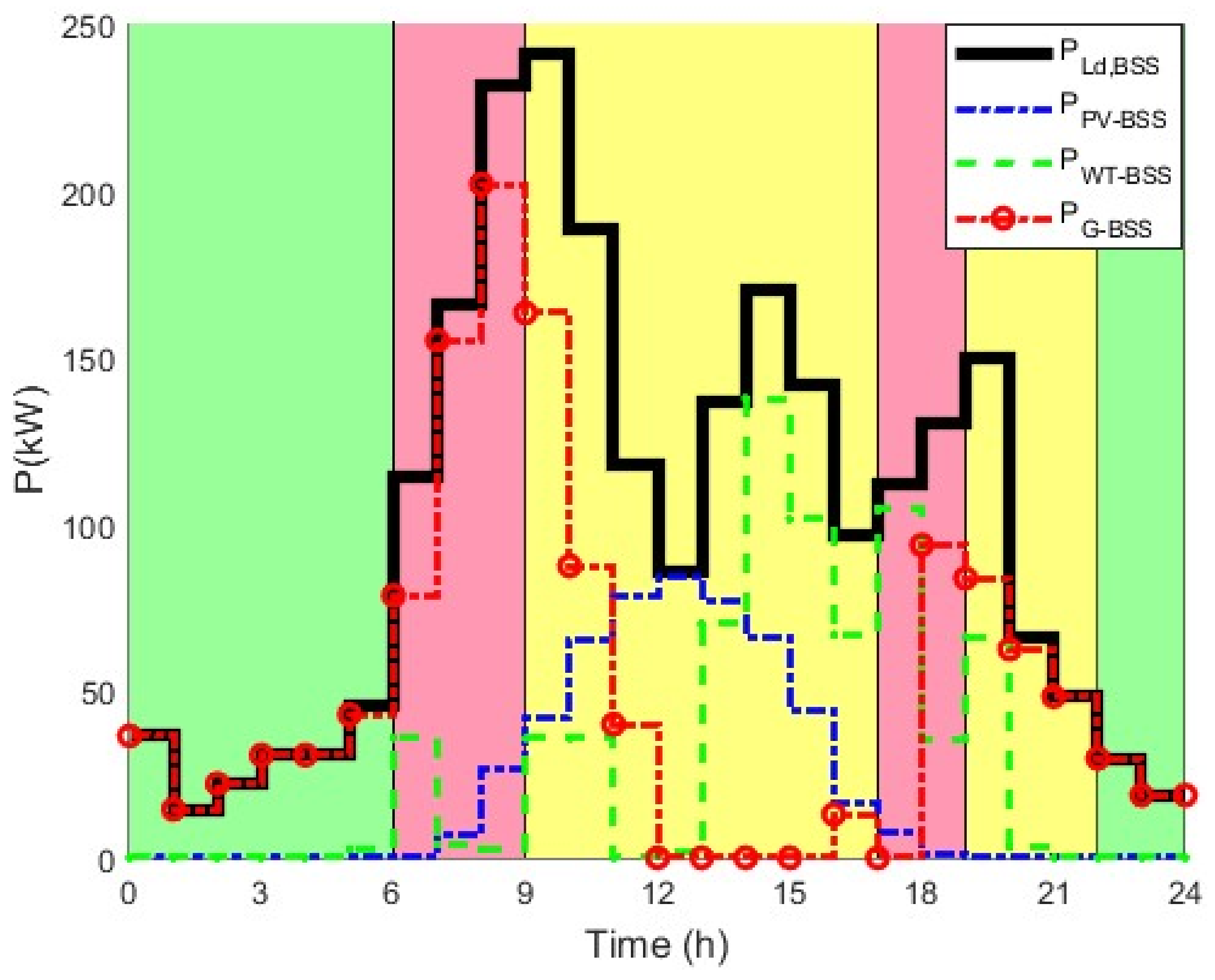

3.1. EV BSS Power Demand Load Profile

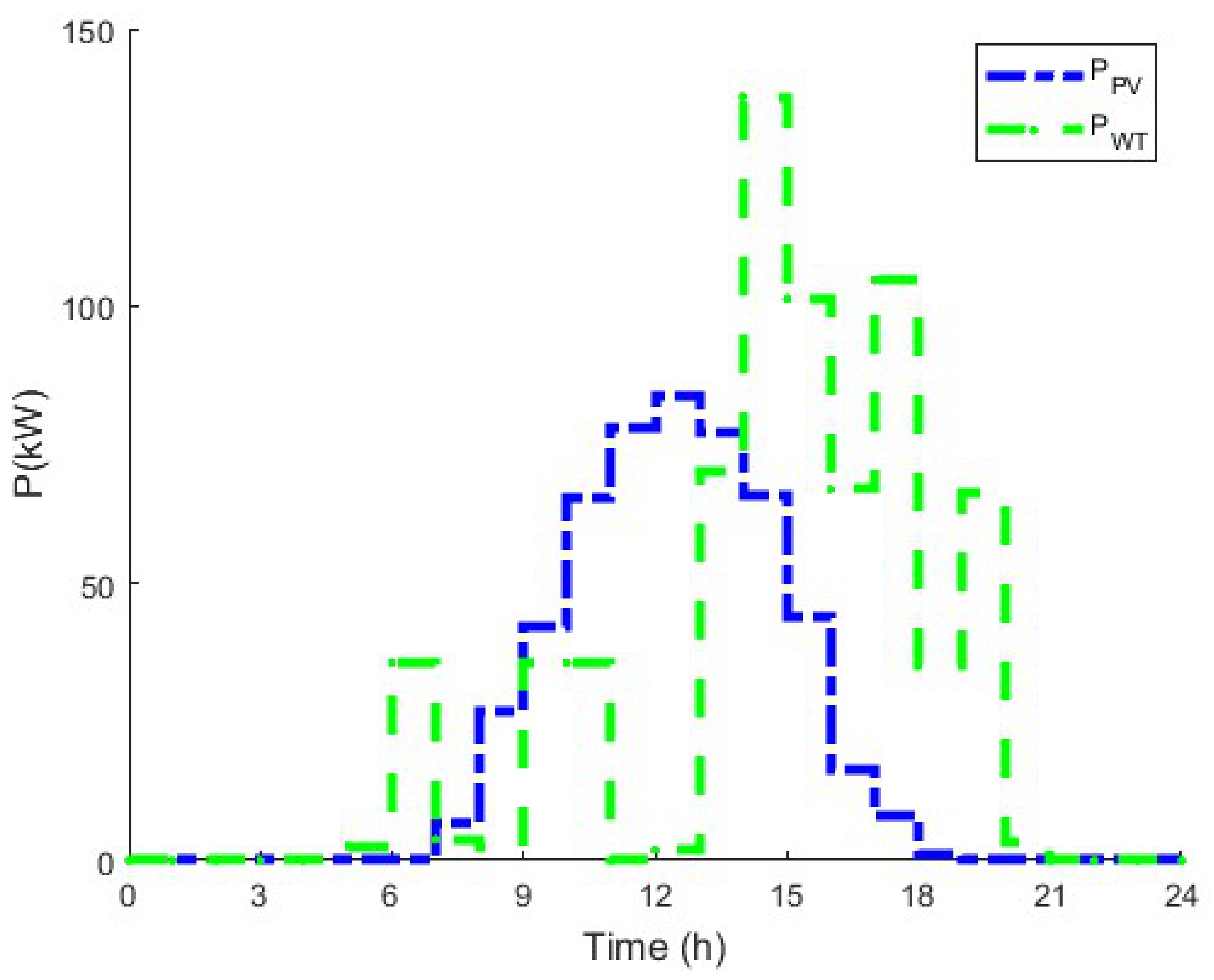

3.2. Renewable Energy Power Supply

3.3. Time-of-Use Electricity Tariff

4. Simulation Results and Discussion

4.1. Optimal Hybrid Power System Sizing and Management Strategy

4.2. LCC Analysis for the Payback Period

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Skovgaard, J. EU climate policy after the crisis. Environmental Politics 2014, 23(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J. A socioecological fix to capitalist crisis and climate change? The possibilities and limits of renewable energy. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 2015, 47, 2485–2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eder, L.; Provornaya, I. Analysis of energy intensity trend as a tool for long-term forecasting of energy consumption. Energy Effciency 2018, 11(8), 1971–1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenny, A. The rise and fall of Eskom and how to fix it now. Policy Bulletin South African Institute Race Relations (IRR) 2015, 2(18), 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Giglmayr, S.; Brent, A.C.; Gauch´e, P.; Fechner, H. Utility-scale PV power and energy supply outlook for South Africa in 2015. Renewable Energy 2015, 83, 779–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, W.; Ahmad, F.; Alam, M.S. Fast EV charging station integration with grid ensuring optimal and quality power exchange. Engineering Science and Technology, an International Journal 2019, 22, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asaad, M.; Ahmad, F.; Alam, M.S.; Rafat, Y. Iot enabled monitoring of an optimized electric vehicles battery system. Mobile Networks and Applications 2018, 23(4), 994–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, F.; Alam, M.S.; Asghar, M.; Ahmad, F. Blackout mitigation of voltage stability constrained transmission corridors through controlled series resistors. Recent Advances in Electrical & Electronic Engineering (Formerly Recent Patents on Electrical & Electronic Engineering) 2018, 11, 4–14. [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency. Global EV Outlook 2021. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2021.

- Alexander, M.; Tonachel, L. Projected greenhouse gas emissions for plug-in electric vehicles. World Electric Vehicle Journal 2016, 8(4), 987–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sujitha, N.; Krithiga, S. Res based ev battery charging system: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2017, 75, 978–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, F. Electric Vehicles: Benefits, Challenges, and Potential Solutions for Widespread Adaptation. Applied Sciences 2023, 13(10), 6016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, W.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Liu, P.; Cui, D.; Dorrell, D.G. A review of siting, sizing, optimal scheduling, and cost-benefit analysis for battery swapping stations. Energy 2022, 124723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dharmakeerthi, C.; Mithulananthan, N.; Saha, T. Impact of electric vehicle fast charging on power system voltage stability. International Journal of Electrical Power& Energy Systems 2014, 57, 241–249. [Google Scholar]

- Nyamayoka, L.T.; Masisi, L.M.; Dorrell, D.G.; Wang, S. Optimisation Design of On-Grid Hybrid Power Supply System for Electric Vehicle Battery Swapping Station. In 2023 IEEE International Future Energy Electronics Conference (IFEEC) 2023, 296-299. IEEE.

- Fan, Y.; Guo, C.; Hou, P.; Tang, Z.; et al. Impact of electric vehicle charging on power load based on tou price. Energy Power Eng 2013, 5, 1347–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehar, F.; Pipattanasomporn, M.; Rahman, S. Demand management to mitigate impacts of plug-in electric vehicle fast charge in buildings with renewables. Energy 2017, 120, 642–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, S.S.; Jadid, S.; Saboori, H. Multi-objective optimum charging management of electric vehicles through battery swapping stations. Energy. 2018, 15(165), 549–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu-Gyamfi, G.; Song, H.; Nketiah, E.; Obuobi, B.; Adjei, M.; Cudjoe, D. Determinants of adoption intention of battery swap technology for electric vehicles. Energy 2022, 15(251), 123862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danilovic, M.; Liu, J.L.; Müllern, T.; Nåbo, A. Almestrand Linné, P. Exploring battery-swapping for electric vehicles in China 1.0.

- Chen, X; Xing, K; Ni, F; Wu. Y; Xia, Y. An electric vehicle battery-swapping system: Concept, architectures, and implementations. IEEE Intelligent Transportation Systems Magazine 2021, 14, 175–194.

- Lebrouhi, B.E.; Khattari, Y.; Lamrani, B.; Maaroufi, M.; Zeraouli, Y.; Kousksou, T. Key challenges for a large-scale development of battery electric vehicles: A comprehensive review. Journal of Energy Storage 2021, 44, 103273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R; Zhang, X; Xie, J; Ju, L. Optimizing electric vehicle users’ charging behavior in battery swapping mode. Applied Energy 2015, 155, 547–559. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X; Yao, L; Zeng, P; Liu, Y; Cai, T. Architecture and performance analysis of a smart battery charging and swapping operation service network for electric vehicles in china. Journal of Modern Power Systems and Clean Energy 2015, 3(2), 259–268. [CrossRef]

- Yan, J; Menghwar, M; Asghar, E; Panjwani, M.K; Liu, Y. Real-time energy management for a smart-community microgrid with battery swapping and renewables. Applied Energy 2019, 238, 180–194. [CrossRef]

- Mahoor, M; Hosseini, Z.S; Khodaei, A. Least-cost operation of a battery swapping station with random customer requestsests. Energy 2019, 172, 913–921. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X; Zhao, T; Yao, S; Soh, C.B; Wang, P. Distributed operation management of battery swapping-charging systems. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2018, 10, 5320–5333.

- Yang, S; Yao, J; Kang, T; Zhu, X. Dynamic operation model of the battery swapping station for ev (electric vehicle) in electricity market. Energy 2014, 65, 544–549. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D; Wen, F; Huang, J. Optimal planning of battery swap stations. International Conference on Sustainable Power Generation and Supply (SUPERGEN 2012) 2012, 2012, 153.

- Zheng, Y; Dong, Z.Y; Xu, Y; Meng, K; Zhao, J.H; Qiu, J. Electric vehicle battery charging/swap stations in distribution systems: comparison study and optimal planning. IEEE transactions on Power Systems 2013, 29, 221–229.

- Wu, S; Xu, Q; Li, Q; Yuan, X; Chen, B. An optimal charging strategy for pv based battery swapping stations in a dc distribution system. International Journal of Photoenergy 2017, 2017.

- Tan, X; Sun, B; Tsang, D.H. Queueing network models for electric vehicle charging station with battery swapping. in 2014 IEEE International Conference on Smart Grid Communications (SmartGridComm) 2014, 1–6.

- Wu, H; Pang, G. K. H; Choy, K. L; Lam, H.Y. An optimization model for electric vehicle battery charging at a battery swapping station. IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology 2017, 67(2), 881–895.

- DoT. Green Transport Strategy for South Africa: (2018-2050), Department of Transport, Pretoria, South Africa February 2019.

- Ahjum, F; Godinho, C; Burton, J; McCall, B; Marquard, A. A low-carbon transport future for South Africa: Technical, Economic and Policy Considerations. 2020.

- Pillay, N. S; Nassiep, S. Employment in automotive parts with electric vehicle market penetration in South Africa. 2020.

- Moeletsi, M. E; Tongwane, M.I. Projected direct carbon dioxide emission reductions as a result of the adoption of electric vehicles in Gauteng province of South Africa. Atmosphere 2020, 11(6), 591. [CrossRef]

- Lamedica, R; Santini, E; Ruvio, A; Palagi, L; Rossetta, I. A MILP methodology to optimize sizing of PV-Wind renewable energy systems. Energy 2018, 165, 385–398. [CrossRef]

- Banks, D.; Schaffler, J. The potential contribution of renewable energy in South Africa. Sustainable Energy & Climate Change Project (SECCP) 2005.

- Diaf, S.; Belhamel, M.; Haddadi, M.; Louche, A. Technical and economic assessment of hybrid photovoltaic/wind system with battery storage in corsica island. Energy policy 2008, 36(2), 743–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaf, S.; Diaf, D.; Belhamel, M.; Haddadi, M.; Louche, A. A methodology for optimal sizing of autonomous hybrid pv/wind system. Energy policy 2007, 35(11), 5708–5718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkaid, A.; Colak, I.; Isik, O. Photovoltaic maximum power point tracking under fast varying of solar radiation. Applied energy 2016, 179, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbes, D.; Martinez, A.; Champenois, G. Life cycle cost, embodied energy and loss of power supply probability for the optimal design of hybrid power systems. Mathematics and Computers in Simulation 2014, 98, 46–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazem, H.A.; Khatib, T. Techno-economical assessment of grid connected photovoltaic power systems productivity in Sohar, Oman. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments 2013, 3, 61–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramli, M.A.; Hiendro, A.; Twaha, S. Economic analysis of pv/diesel hybrid system with flywheel energy storage. Renewable Energy 2015, 78, 398–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokopane, L.; Kanzumba, K.; Vermaak, H. Is the south african electrical infrastructure ready for electric vehicles? 2019 Open Innovations (OI). IEEE 2019, 127–131. [Google Scholar]

- Dane, A.; Wright, D.; Montmasson-Clair, G. Exploring the policy impacts of a transition to electric vehicles in South Africa. Pretoria: Trade & Industrial Policy Strategies 2019.

- Sooknanan Pillay, N.; Brent, A.C.; Musango, J.K.; van Geems, F. Using a system dynamics modelling process to determine the impact of ecar, ebus and etruck market penetration on carbon emissions in South Africa. Energies 2020, 13(3), 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenna, M.; Foiadelli, F.; Leone, C.; Longo, M. Electric vehicles charging technology review and optimal size estimation. Journal of Electrical Engineering & Technology 2020, 15, 2539–2552. [Google Scholar]

- Hemmati, R. Chapter 3 - integration of electric vehicles and charging stations. In Energy Management in Homes and Residential Microgrids: Short-Term Scheduling and Long-Term Planning; Hemmati, R.; Elsevier, 2024; pp. 79–140.

- Evans, A.; Strezov, V.; Evans, T.J. Assessment of sustainability indicators for renewable energy technologies. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2009, 13(5), 1082–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adefarati, T.; Bansal, R.C.; Shongwe, T.; Naidoo, R.; Bettayeb, M; Onaolapo, A.K. Optimal energy management, technical, economic, social, political and environmental benefit analysis of a grid-connected PV/WT/FC hybrid energy system. Energy Conversion and Management 2023, 292, 117390. [CrossRef]

- Al-Sharrah, G.; Elkamel, A.; Almanssoor, A. Sustainability indicators for decision-making and optimisation in the process industry: The case of the petrochemical industry. Chemical Engineering Science 2010, 65(4), 1452–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, M.; Oladigbolu, J.O.; Mujeeb, A.; Al-Turki, Y.A. Cost-effective optimization of on-grid electric vehicle charging systems with integrated renewable energy and energy storage: an economic and reliability analysis. Journal of Energy Storage 2024, 100, 113170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sediqi, M.M.; Furukakoi, M.; Lotfy, M.E.; Yona, A.; Senjyu, T. Optimal economical sizing of grid-connected hybrid renewable energy system. Journal of Energy and Power Engineering 2017, 11(4), 244–253. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Maleki, A.; Rosen, M.A.; Liu, J. Optimization with a simulated annealing algorithm of a hybrid system for renewable energy including battery and hydrogen storage. Energy 2018, 163, 191–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaabeche, A.; Belhamel, M.; Ibtiouen, R. Sizing optimization of grid-independent hybrid photovoltaic/wind power generation system. Energy 2011, 36(2), 1214–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamjoo, A.; Maheri, A.; Dizqah, A.M.; Putrus, G.A. Multi-objective design under uncertainties of hybrid renewable energy system using NSGA-II and chance constrained programming. International journal of electrical power & energy systems 2016, 74, 187–194. [Google Scholar]

- Duffie, J.A.; Beckman, W.A.; Blair, N. Solar engineering of thermal processes, photovoltaics and wind, 5th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, 2020.

- Eltamaly, A.M.; Mohamed, M.A. Optimal sizing and designing of hybrid renewable energy systems in smart grid applications. in Advances in renewable energies and power technologies Elsevier, 2018, 231–313.

- Askarzadeh, A.; dos Santos Coelho, L. A novel framework for optimization of a grid-independent hybrid renewable energy system: A case study of Iran. Solar Energy 2015, 112, 383–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maleki, A.; Pourfayaz, F.; Rosen, M.A. A novel framework for optimal design of hybrid renewable energy-based autonomous energy systems: a case study for Naming, Iran. Energy 2016, 98, 168–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anoune, K.; Ghazi, M.; Bouya, M.; Laknizi, A.; Ghazouani, M.; Abdellah, A.B.; Astito, A. Optimization and techno-economic analysis of photovoltaic-wind-battery based hybrid system. Journal of Energy Storage 2020, 32, 101878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bénichou, M.; Gauthier, J.M.; Girodet, P.; Hentges, G.; Ribière, G.; Vincent, O. Experiments in mixed-integer linear programming. Mathematical programming 1971, 1, 76–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penangsang, O.; Sulistijono, P. Suyanto, Optimal power flow using multi-objective genetic algorithm to minimize generation emission and operational cost in micro-grid. International Journal of Smart Grid and Clean Energy 2014, 3, 410–416.

- Gunantara, N. A review of multi-objective optimization: Methods and its applications. Cogent Engineering 2018, 5(1), 1502242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://weatherspark.com/y/82961/Average-Weather-in-Cape-Town-South-Africa-Year-Round#Figures-WindSpeed (accessed on 25 November 2023).

- Hoppmann, J.; Volland, J.; Schmidt, T.S.; Hottmann, V.H. The economic viability of battery storage for residential solar photovoltaic systems–A review and a simulation model. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2014, 2014 39, 1101–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G. Development of a general sustainability indicator for renewable energy systems: A review. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2014, 31, 611–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sichilalu, S.; Mathaba, T.; Xia, X. Optimal control of a wind–PV-hybrid powered heat pump water heater. Applied energy 2017, 185, 1173–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| 4 |

| Parameters | Symbol | Values |

|---|---|---|

| Installation lifetime | 20 years | |

| Sampling period | N | 24 |

| Sampling time | 1 h | |

| Weighting factor | 0.5 | |

| Upper bound | ||

| Lower bound | ||

| Inflation rate | r | 4.60% |

| Interest rate | i | 8.25% |

| PHOTOVOLTAIC SYSTEMS | ||

| Lifetime of the PV system | 25 years | |

| Rated power of the PV panel | 0.545 kW | |

| Conversion efficiency of the PV panel | 19.4% | |

| Rated efficiency of the PV panel | 18.1% | |

| Initial cost of the PV panel | 3 199.99 ZAR | |

| Annual O & M cost of PV | 1% of | |

| Capital cost of the solar PV per kW | 8 220.16 ZAR/kW | |

| WIND TURBINE SYSTEMS | ||

| Lifetime of the WT system | 25 years | |

| Rated power of the WT generator | 8 kW | |

| Rated WT speed | 12 m/s | |

| Cut-in WT speed | 2.5 m/s | |

| Cut-out WT speed | 25 m/s | |

| WT gearbox efficiency | 90% | |

| WT generator efficiency | 80% | |

| Air density | 1.225 kg/m3 | |

| WT power coefficient | 0.48 | |

| Initial cost of the WT | 10 580,63 ZAR | |

| Annual O & M cost of WT | 5% of | |

| Capital cost of the WT per kW | 15 403 ZAR/kW | |

| INVERTER | ||

| Lifetime of the inverter | 15 Years | |

| Efficiency of the inverter | 98% | |

| Inverter factor | 1.25 | |

| Initial cost of the inverter | 38 860.00 ZAR | |

| Capital cost of inverter per kW | 3 108.80 ZAR/kW |

| Number of WTs | Number of PV panels | Total life cycle cost |

|---|---|---|

| 64 | 420 | 1 963 520.12 ZAR |

| Baseline cost | Optimal cost | Cost saving | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daily | 7 676.39 ZAR | 4 483.53 ZAR | 3 192.5 ZAR |

| Annualized | 1 165 262.5 ZAR |

| Components | Costs (ZAR) |

|---|---|

| Wind turbines | 677 160.32 |

| Solar photovoltaic | 1 286 359.80 |

| Inverters | 77 720 |

| Installation cost | 649 975,98 |

| Accessories | 3 000 000 |

| Total investment capital cost | 5 691 216.10 |

| Years | Annual O & M cost (ZAR) | Annual optimal cost benefit (ZAR) | Total | Discount factor (1+d) | Discounted cash flows | Cumulative cash flows |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1.00 | (5 691 216.10) | (5 691 216.10) | |||

| 1 | (46 721.61) | 1 165 390.25 | 1 118 668.64 | 0.96 | 1 079 275.10 | (4 611 941.01) |

| 2 | (47 389.73) | 1 182 055.33 | 1 134 665.60 | 0.93 | 1 056 158.93 | (3 555 782.07) |

| 3 | (48 067.40) | 1 198 958.72 | 1 150 891.32 | 0.90 | 1 033 537.87 | (2 522 244.20) |

| 4 | (48 754.77) | 1 216 103.83 | 1 167 349.07 | 0.87 | 1 011 401.32 | (1 510 842.89) |

| 5 | (49 451.96) | 1 233 494.12 | 1 184 042.16 | 0.84 | 989 738.89 | (521 104.00) |

| 6 | (50 159.12) | 1 251 133.08 | 1 200 973.96 | 0.81 | 968 540.43 | 447 436.43 |

| 7 | (50 876.40) | 1 269 024.29 | 1 218 147.89 | 0.78 | 947 796.00 | 1 395 232.43 |

| 8 | (51 603.93) | 1 287 171.33 | 1 235 567.40 | 0.75 | 927 495.88 | 2 322 728.31 |

| 9 | (52 341.87) | 1 305 577.88 | 1 253 236.02 | 0.72 | 907 630.56 | 3 230 358.87 |

| 10 | (53 090.35) | 1 324 247.65 | 1 271 157.29 | 0.70 | 788 190.71 | 4 018 549.58 |

| 11 | (53 849.55) | 1 343 184.39 | 1 289 334.84 | 0.67 | 869 167.24 | 4 887 716.82 |

| 12 | (54 619.60) | 1 362 391.92 | 1 307 772.33 | 0.65 | 850 551.21 | 5 738 268.03 |

| 13 | (55 400.66) | 1 381 874.13 | 1 326 473.47 | 0.63 | 832 333.90 | 6 570 601.93 |

| 14 | (56 192.89) | 1 401 634.93 | 1 345 442.04 | 0.61 | 814 506.78 | 7 385 108.72 |

| 15 | (56 996.44) | 1 421 678.31 | 1 364 681.86 | 0.58 | 797 061.48 | 8 182 170.20 |

| 16 | (57 811.49) | 1 442 008.31 | 1 384 196.82 | 0.56 | 779 989.84 | 8 962 160.04 |

| 17 | (58 638.20) | 1 462 629.03 | 1 403 990.83 | 0.54 | 763 283.83 | 9 725 443.87 |

| 18 | (59 476.72) | 1 483 544.62 | 1 424 067.90 | 0.52 | 746 935.64 | 10 472 379.50 |

| 19 | (60 327.24) | 1 504 759.31 | 1 444 432.07 | 0.51 | 730 937.60 | 11 203 317.10 |

| 20 | (61 189.92) | 1 526 277.37 | 1 465 087.45 | 0.49 | 715 282.20 | 11 918 599.30 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).