1. Introduction

Biomaterials must present good mechanical properties, corrosion resistance and biocompatibility. The Young’s modulus is essential due to the stress shielding phenomenon, as it influences the stress difference between the implant and the adjacent bone, which can potentially lead to bone resorption and failure of the implant [

1,

2,

3,

4]. In biomedical applications, high corrosion resistance is essential to ensure the longevity and safety of implants. The results suggest that optimizing the composition of Ti-Nb alloys can lead to improved performance in corrosive environments, which is particularly important in the human body [

5]. Studies have shown that this difference can increase porosity and compromise bone adhesion [

6,

7,

8].

The biomedical materials that are widely used for hard tissue replacement and their Young’s modulus are stainless steel alloys 316L (200 GPa), Co-Cr-Mo alloys (210 GPa) [

9], Ti-6Al-4V alloys (110 GPa), and CP Ti (103 GPa). However, they still have a much higher Young’s modulus (3 to 6 times) than that of human bone (30 GPa) [

10].

The Ti-6Al-4V alloy, used as biomedical implants, offers greater mechanical strength, corrosion resistance, and hardness when compared to CP Ti . However, the release of toxic aluminum (Al) and vanadium (V) ions can cause serious long-term health problems, including neurological disorders and Alzheimer’s disease associated with Al, and V ion toxicity that can negatively affect the respiratory system [

11]. Therefore, there is a significant need to develop new titanium alloys to reduce Young’s modulus, increase mechanical strength and not contain Al and V, such as alloys incorporating Mo, Nb, Ta, and/or Zr, based on the formation of substitutional solid solutions.

Researchers have observed that martensitic Ti-Nb alloys with relatively low Nb content can have Young’s modulus comparable to β phase alloys [

12,

13]. Studies on the mechanical properties of binary Ti-Nb alloys have revealed significant results. These studies involve Ti–xNb (x = 0,1, 2 wt.%) [

14,

15,

16], Ti–xNb (x = 5, 10 wt.%) [

17], Ti–xNb (x = 10, 15 wt.%) [

18,

19], Ti–xNb (x = 15–20 wt.%) [

20,

21], and Ti–xNb (x = 20, 25 wt.%) [

22]. Depending on the chemical composition and thermomechanical treatment, Ti-Nb alloys form solid solutions based on α and β titanium modifications, such as stable α, β, and metastable phases α’, α’’, and ω [

23]. The addition of Nb influences the stability of different phases in titanium alloys. Specifically, it suppresses the formation of the alpha (α) phase and reduces the volume fraction of the omega (ω) phase. This suppression is beneficial as it enhances the mechanical properties of the alloy, making it more suitable for applications such as biomedical implants. A study of the Ti-10Nb alloy identified α’ or α’’ phases. The α’’ phase showed a similar reflection to β-Ti, except for broad peaks at large angles. Additional microstructural analysis is required for precise identification of these phases. Optical metallography results confirmed the presence of the α’’ phase, evidenced by needle-like structures in the metastable martensite region [

24,

25]. Martensite α’’ phase needles are predominant at the sample’s edges, reaching up to 300 microns in length by about 10 microns in width, while these structures are not observed in the sample’s interior. The reason for this is that as the ingot cools, it transitions from metastable conditions at the surface to an equilibrium state in the center, causing changes in the cooling mode [

26].

The molybdenum (Mo) stabilizes the β phase in Ti alloys [

27] and it’s effective in the design of β alloys. Hanada et al. [

28] observed the formation of the α’’ phase in Ti-Mo alloys with Mo content between 11% and 18% during cold working.

A study concluded that the addition of niobium (Nb) significantly affects the microstructure of Ti-xNb-5Mo (x = 0,10,20,30 wt.%) alloys. As the Nb content increases, there is a notable decrease in the alpha (α) phase and a corresponding increase in the beta (β) phase and the average crystallite size of both the α and β phases increases with the addition of Nb [

29]. This transition is crucial for enhancing the mechanical properties of the alloys, potentially leading to improved ductility and toughness, making them more suitable for various application.

Recent investigations have shown that in addition to increasing the β-stabilizer content, thermomechanical treatment is an effective approach to suppress the formation of α″ martensite. For example, the martensitic transformation from β to α″ can be effectively suppressed by grain refinement, which can be achieved by severe plastic deformation and recrystallization [

28,

29,

30]. This means that with the help of thermomechanical treatment, the martensitic transformation can be suppressed in the β phase with low β-stabilizers, which is favorable for obtaining the β-Ti alloys with low Young’s modulus.

In the case of Ti-Mo-Nb alloys, the development of microstructures with a β-Ti matrix containing metastable α’’ precipitates can contribute to the synthesis of materials with lower Young’s modulus, superior hardness, compressive strength, and wear resistance compared to conventional titanium alloys containing V, Ta, and/or Zr, which is desirable for the development of biomedical implants [

31,

32,

33,

34].

In this context, this study investigated the compressive mechanical properties and microstructures of Ti-15Mo-xNb (13, 15, and 19 wt.%) alloys, synthesized via arc melting followed by heat treatment and cold working.

2. Materials and Methods

The Ti-15Mo-xNb (x = 13, 16, 19 wt.%) alloy was prepared with high-purity metal sheet elements, Ti, Mo, and Nb, and weighted in the aimed composition with a total 30 g mass ingots using an analytical scale (0.1 mg precision). Information about the purity (

Table 1).

The ingots of ternary alloys Ti-15Mo-xNb (x = 13, 16, 19 wt.%) were synthesized by arc melting with a non-consumable tungsten electrode under an argon (Ar) atmosphere, four purges were performed using argon gas with 99.999% purity and a vacuum pump at 10⁻² mbar. The samples were remelted five times to ensure uniform chemical composition. The ingots were machined to the dimensions of Ø12x50 mm (±0.1) mm to fit the internal diameter of the forging die.

The ingots were swage forged at room temperature. The diameter was reduced by approximately 0.8 mm per pass until a final diameter of approximately 5 mm was achieved, representing a diameter reduction of 70%. The samples were encapsulated in a quartz tube under an Ar atmosphere and heat treated at 1100 °C for 2 h and 800 °C for 0.5 h before and after forging, respectively, and quenching to ensure the formation of the β-Ti phase, according to the experimental procedures of Guo et al. [

13].

Microstructural characterization of the samples was performed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM), Hitachi model TM3000, with an energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) detector for microanalysis. X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of these samples were obtained using an Empyrean XRD 3rd generation (Malvern, Panalytical) X-ray diffractometer, operating at room temperature, 40kV and 30mA with Cu-Kα radiation, diffraction angle (2θ) between 10 and 90°; angular step of 0.05° and counting time per step of 80 s. The phases present in the samples were indexed using Person’s Crystal Data files version 1.0.

Mechanical characterization was performed using microhardness measurements and compression tests. For the Vickers microhardness tests, the ASTM 384 [

35] standard was used. Fifteen measurements were taken across the sample surface using a load of 200 gf (2.05 N) for 15 s on a table-top microhardness tester, model MicroMet 6020 (Buehler). Compression testing of the alloys after cold forging and heat treatment was carried out at room temperature in accordance with ASTM E9 [

36]. Three specimens of each alloy were used following standard procedures on a servo-hydraulic universal testing machine with axial actuator and Dynacell model 8801 compression tests, with a capacity of 10 tonnes, a test speed of 0.5 mm/min and a 250 kN load cell (Instron).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Microstructural Characterization

The uniformity of the ingot’s composition was checked using SEM-EDS, where measurements were taken at specific points on the cross-section surface (

Table 2). The analysis included areas near the edge and closer to the center of the ingot. The results showed that the nominal composition by SEM-EDS wt.% of each ingot stayed the same throughout its volume.

There was no sign of zone segregation in the ingots observed in the alloys after heat treatment at 800ºC for 0.5 h with different amounts of Nb, which often happens due to incomplete or uneven remelting. These findings were also confirmed by optical metallography (

Figure 4) of the ingots’ cross-sections. Structural differences, like variations in the appearance of zones or differences in grain size in certain areas, were not found on the cross-section surface after processing the alloys, was not observed on the surface of the section after alloy treatment.

In titanium alloys, the utilization of significant quantities of chemical elements to stabilize the β phase, followed by heat treatment under rapid cooling conditions, results in the formation of substantial amounts of martensitic α’’ (orthorhombic) phases. Consequently, the resultant quantity of the β phase can exhibit variability, thereby affecting both microstructural and mechanical properties. The presence of the α’’ phase distinctly influences a critical property for biomedical alloys: the modulus of elasticity. Accordingly, heat treatment temperatures of 1100°C and 800°C were established, which correlate closely with the beta-transus temperature for these β-type titanium alloys (β-Ti) [

38,

39].

The Mo equivalence method (Mo

eq) is used to predict the stability of the β phase in β-type titanium alloys (β-Ti) and to evaluate the effect of β-stabilizing elements. Mo, a primary β-stabilizer, is used as a reference point, and other elements are normalized to this Mo

eq value [

40,

41]. Typically, the β phase becomes dominant in titanium alloys when the Mo content reaches 10 wt.%, and higher Mo

eq values usually result in more stable β-Ti alloys [

42,

43].

Using equation (1), Mo

eq was calculated for the designed alloys. The results presented in

Table 3 show that the Ti-15Mo-xNb alloys (with x = 13, 16, and 19 wt.%) have Mo

eq values above 10 wt.%, indicating that these alloys should have a β phase microstructure. However, since the Nb content is relatively low in weight percent, the β phase also includes the metastable α’’ phase formation [

44].

The XRD analysis was performed on Ti-15Mo-xNb alloys (x = 13, 16, 19 wt.%) to elucidate their crystalline microstructural characteristics. The phases present in the material were identified using GSAS II

® software and the International Crystal Structure Database (ICSD). The phases were validated by comparing the obtained diffraction patterns with reference data [

45], confirming the preference for the β-Ti phase. Through the most intense diffraction peaks, it was possible to identify the majority of the β phase.

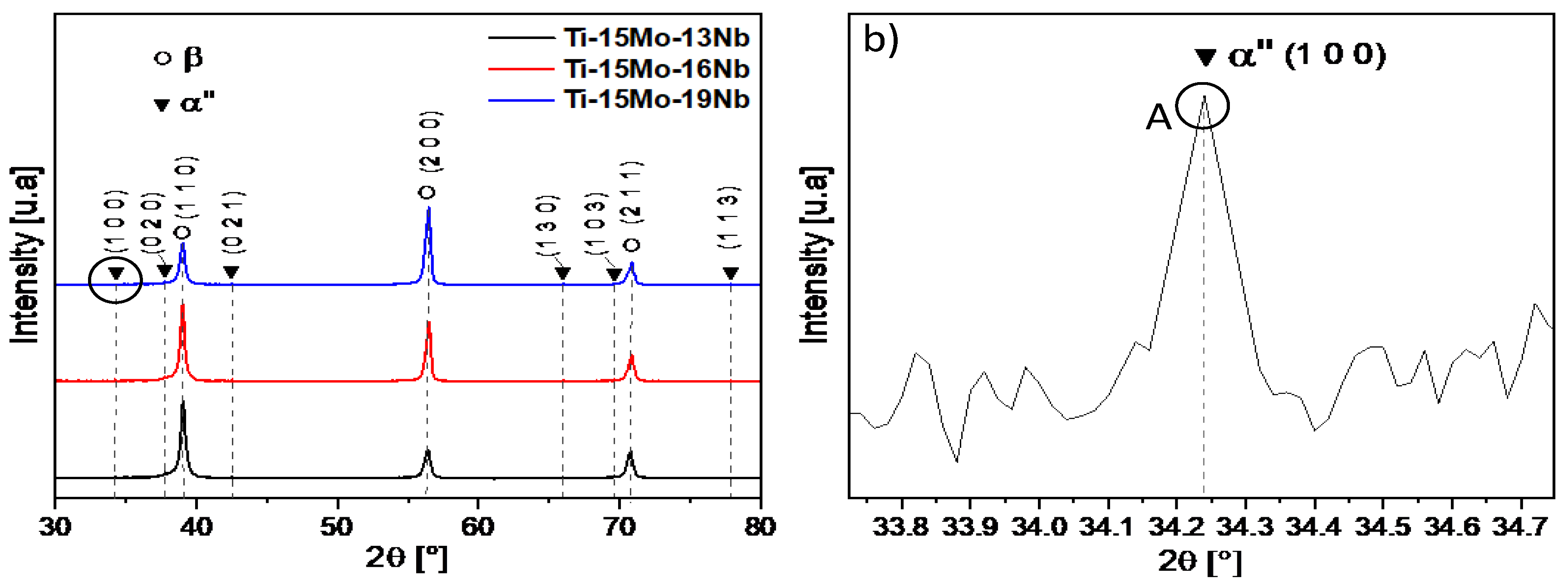

Figure 1(a) shows the XRD patterns of the samples forged and heat treated at 800ºC for 0.5 h. A study reveals that the start temperature for the α″ phase transformation is consistently above that of the ω phase transformation across various Ti-Nb alloys [

18]. This indicates that the α″ phase begins to form at higher temperatures, which is crucial for understanding the thermal behavior of these alloys during cooling and processing [

19]. Because this, the temperatures heat treatment at 800°C. The temperatures were also selected based on the specific compositions of the Ti-Nb alloys studied. Different alloy compositions can lead to variations in phase stability and transformation temperatures. By choosing a range of temperatures, the researchers could assess how these factors influence the overall behavior of the alloys, providing a comprehensive understanding of their thermal propertie. The samples analyzed are Ti-15Mo-13Nb, Ti-15Mo-16Nb and Ti-15Mo-19Nb. One phase is evident in the microstructures. The experimental results indicate that the alloys are predominantly composed of the β body-centered cubic (BCC) phase. Since the alloys studied are metastable, a slower XRD scan was performed to better evaluate some peaks associated with the α

’’ phase, as shown in

Figure 1(b). In all the alloys analyzed, intense and predominant β-Ti peaks were identified compared to Ti CP, particularly in the 2θ regions of (39.02°, 56.46° and 70.86°). In addition to these peaks, the Ti-15Mo-13Nb alloy shows low intensity peaks of the α

’’ phase that were also indexed in the nominal 2θ composition regions (34.24°, 37.76°, 42.54°, 66.15°, 69.6° and 77.84°) after heat treatment at 800ºC for 0.5h.

For alloys after cold forging, the intense and predominant diffraction peaks of β (200) and β (211) decreased in intensity. In addition, Ti-15Mo-13Nb new peaks for α

’’ (020) and α

’’ (100). The volume fraction of this phase remains constant. This suggests that the martensitic transformation was induced by stress and/or deformation during cold forging. After heat treatment at 800ºC for 0.5 hours, the α

’’ martensite formed by quenching and cold forging, as the formation of other phases was not observed as the percentage of Nb increased [

16,

24].

In the XRD patterns shown in

Figure 1, it is evident that the niobium atoms are dissolved into these crystalline structures, with this trend being more pronounced in the Ti-15Mo-19Nb alloy. This observation is consistent with the results of previous studies [

11,

13].

3.2. Lattice Parameter, Crystallite Size and Microstrain of the Phase β-Ti

In order to understand the microstructural changes in the studied alloys and to correlate them with their mechanical properties, it was necessary to calculate several parameters: lattice parameter, crystallite size, and microstrain of the undispersed β-Ti phase. The Ti-α’’ phase was not observed due to its low volume fraction.

Among these parameters, the lattice parameter represents the distance between atoms that are periodically repeated in a crystalline structure, as described by Brag

g’s law in equation (2) [

45].

where n is the order of diffraction (typically n=1), λ is the wavelength of X-rays, and d is the spacing between planes with specified Miller indices h, k, and l. In the β-Ti (BCC) structure, the interplanar spacing d is related to the lattice parameter a=b=c and the Miller indices by the following relationship, as given in equation (3) [

45].

To calculate the crystallite size and microstrain, we used the Williamson-Hall (W-H) equation from the Uniform Stress Deformation Model (USDM), as shown in equation (4). In this equation, D represents the crystallite size, λ is the wavelength of Cu-Kα radiation, θ is the Bragg reflection angle, K is the Scherrer constant (typically K=0.94, depending on the symmetry of the crystal structure), and B is the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the diffraction peak. The equation (5) represents the W-H equation for the USDM, where the lattice strain ε is replaced by the stress σ according to Hook

e’s law (σ=E

h,k,lε) [

46].

For cubic crystals, the Youn

g’s modulus E

h,k,l is given by equation (6) [

43].

S11, S12, and S44 are elastic compliances for Ti. The values of S11, S12 and S44 are

9.9×10

-12, -4.7×10

-12 and 21.4×10

-12 Pa

-1, respectively [

47].

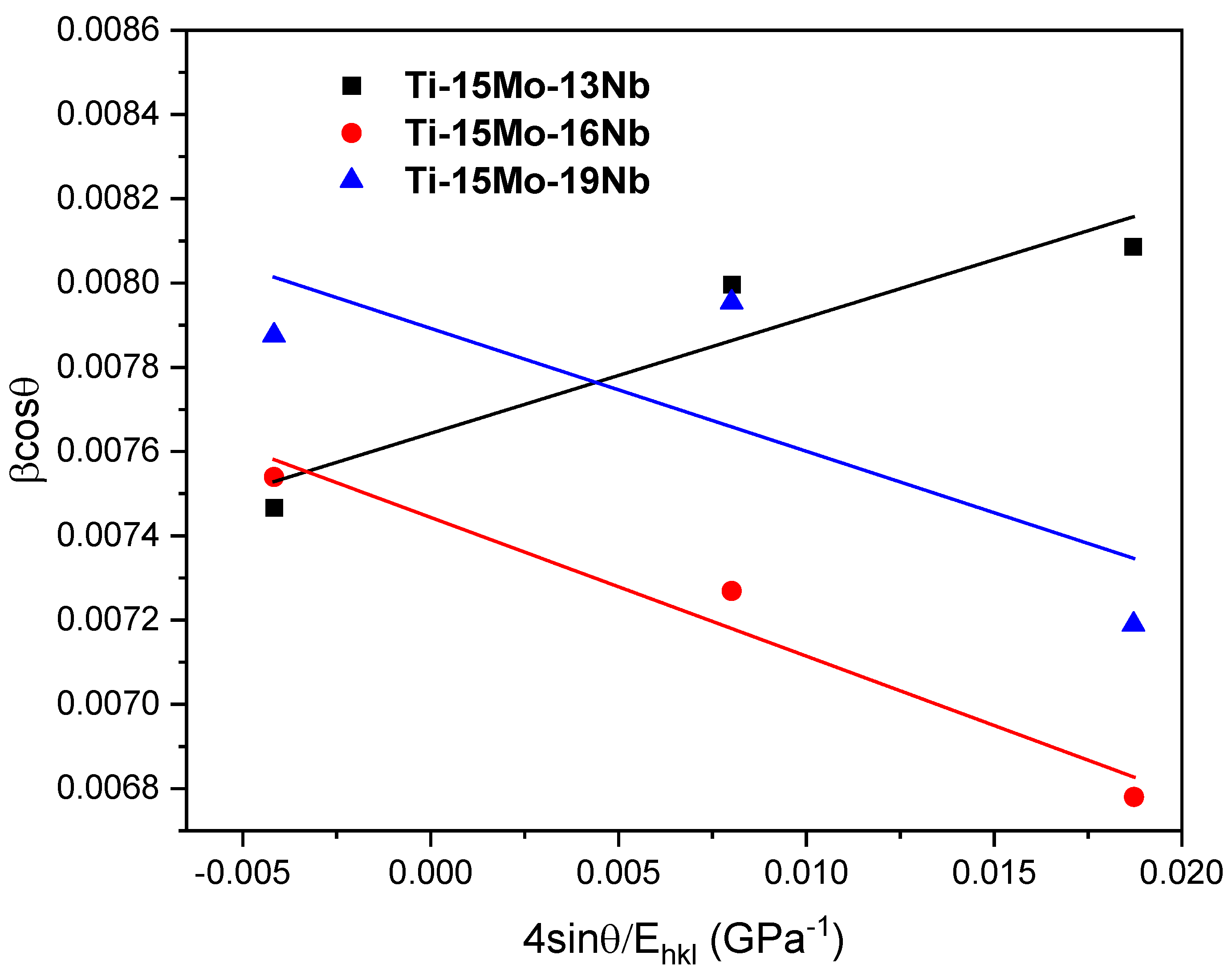

Figure 2 shows a graphical representation of the relation between Bcosθ and 4sinθ/E

h,k,l for the three alloys studied.

Using equation (3), it is possible to calculate the lattice parameter of the samples by comparing it with the standard lattice constant of β-Ti [

48]. In addition, the crystallite size and microstrain can be determined using the linear equation of the lines in

Figure 2, as shown by the results in

Figure 3.

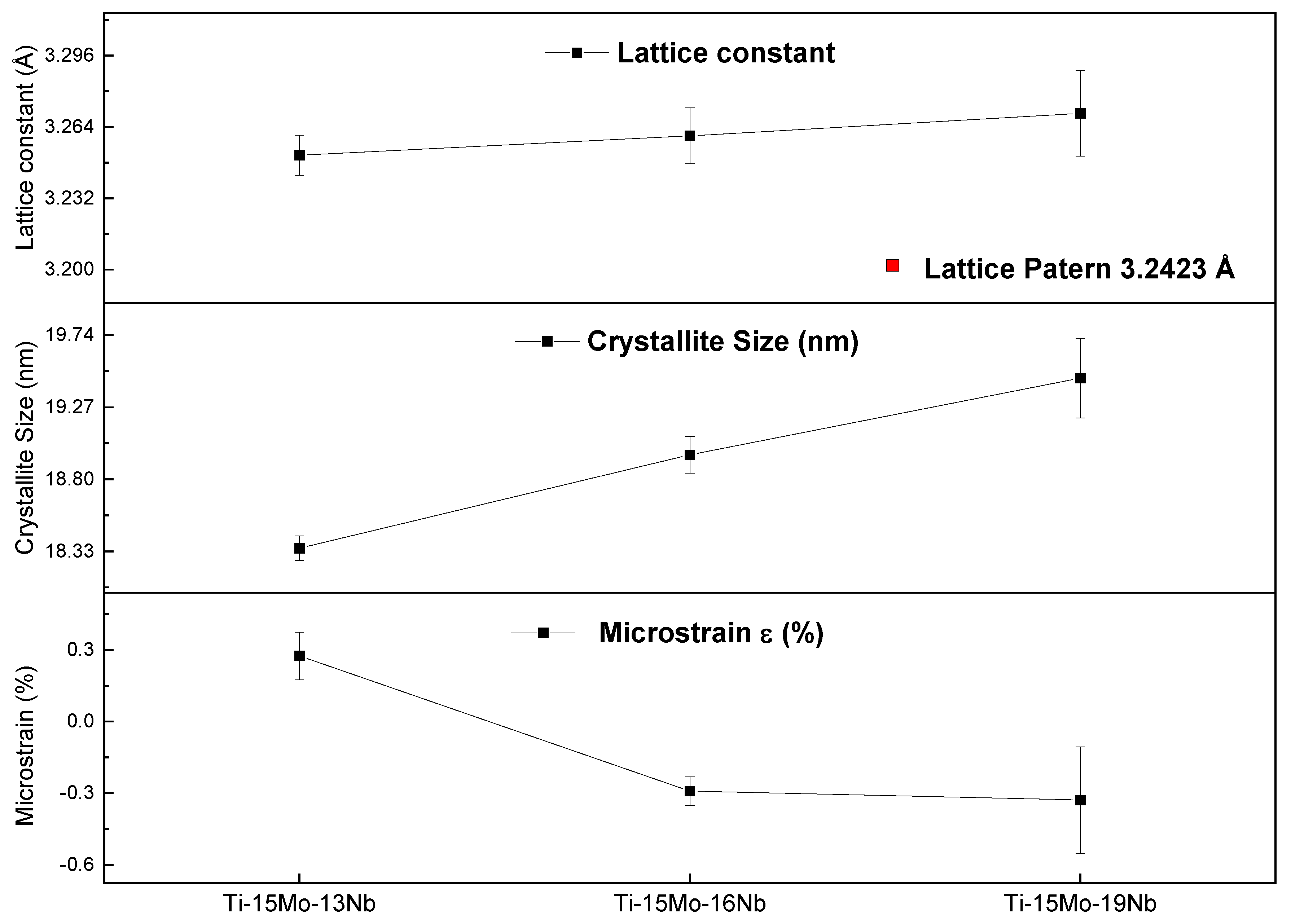

As shown in

Figure 3, different lattice parameter values are observed in the alloys after heat treatment at 800ºC for 0.5 h. There is a gradual increase in the lattice parameter from 3.2450 Å at 13% Nb content to 3.2650 Å at 19% Nb content. This indicates distortions in the crystalline lattice structure with increasing Nb content. With the addition of Nb, the average crystallite size of the β phase increases from 18.33 nm at 13 wt.% Nb to 19.58 nm at 19 wt.% Nb. This is due to the distortion caused in the lattice by Nb atoms that are larger than Ti and Mo atoms. This result is consistent with similar observations reported by Chen et al.[

49] and Santos et al.[

50] in their studies evaluating β-stabilizing element additions. In the Ti-15Mo-13Nb alloy, the positive tensile microstrain (0.248%) may be related to the homogeneous distribution of Nb atoms. As the Nb content increases to 16% and 19%, the microstrain shifts to compression (-0.2916% and -0.3292%, respectively), possibly due to the precipitation of small fractions of the α” phase. It is reasonable to consider this transition as a less homogeneous distribution of Nb atoms with increasing Nb content in the designed alloys.

These alloy samples are based on substitutional solid solutions where the addition of niobium increases the microhardness. There is a trend of approximately 33% increase in microhardness with increasing concentration of niobium due to the larger atomic radius of niobium (0.156nm) compared to the titanium it replaces (0.148nm) [

51,

52]. By replacing titanium atoms in the crystal structure, niobium atoms can prevent the movement of dislocations, contributing to greater mechanical strength [

53]. It is therefore believed that the addition of niobium can help to strengthen the solid solution by preventing the movement of atomic dislocations. Therefore, the increase in microhardness in these alloys is due to the addition of niobium to the composition.

Many other transition metals act as substitutional elements, but not with a beta-stabilizing character like niobium. The presence of metastable phases can enhance desirable properties such as wear resistance and comprehensive, important for a metallic biomaterial. For instance, the α″ phase in Ti-Mo with Nb alloys is associated with these properties, and knowing that it can coexist with the metastable ω phase allows for the design of alloys that maximize these effects while minimizing potential drawbacks like embrittlement [

54,

55].

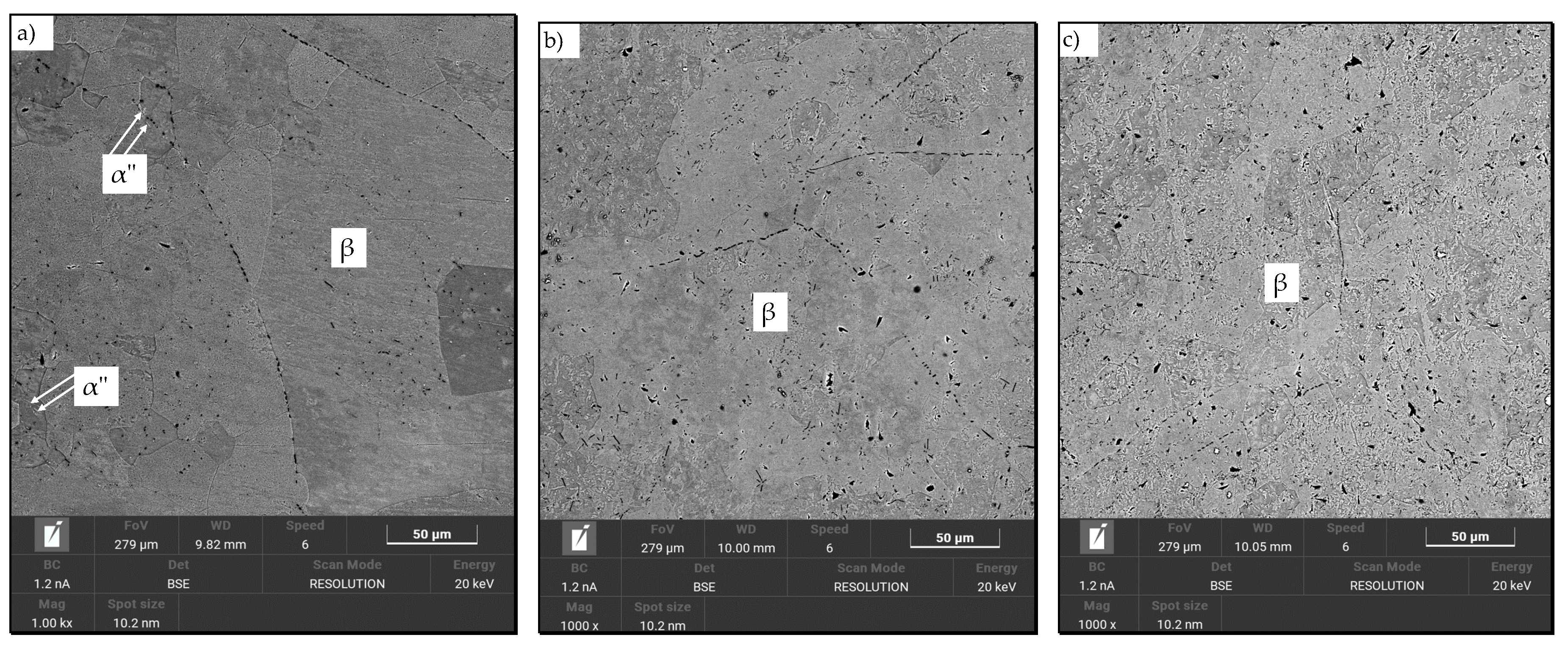

Figure 4 shows the scanning electron micrographs of the Ti-15Mo-xNb alloy samples (x = 13, 16, 19 wt.%) after heat treatment at 800ºC for 0.5 h. In

Figure 4a, the microstructure of the Ti-15Mo-13Nb alloy is composed mainly of the β phase and a small fraction of the phase in the form of fine, reduced acicular needles and lamellar structures typical of the martensitic α” phase at the grain boundary of the β phase. The martensitic α” phase in this alloy has a fine needle morphology according to [

16,

24].

Figure 4b and 4c shows the microstructure of the Ti-15-16Nb and Ti-15Mo-19Nb alloys is mainly composed of the β phase present and consists only of grain boundaries of the β phase. Therefore, the microstructure of the alloys studied was sensitive to the addition of Nb, with the number of needles characteristic of the α” phase decreasing as the content of the stabilizing element β-niobium increased. Thus, the addition of niobium reduces the transition to the α” phase of martensite and stabilizes the β phase of the alloys in these Ti-15Mo-xNb alloys (x = 13, 16, 19 wt.%). These results are consistent with the XRD patterns shown.

Figure 4.

Micrographs of a) Ti-15Mo-13Nb, b) Ti-15Mo-16Nb, and c) Ti-15Mo-19Nb alloys after heat treatment at 800°C for 0,5h. Presence of a β-Ti matrix and α” precipitates only Ti-15Mo-13Nb.

Figure 4.

Micrographs of a) Ti-15Mo-13Nb, b) Ti-15Mo-16Nb, and c) Ti-15Mo-19Nb alloys after heat treatment at 800°C for 0,5h. Presence of a β-Ti matrix and α” precipitates only Ti-15Mo-13Nb.

3.3. Mechanical Characterization

Table 4 shows the Vickers microhardness results for the alloys after heat treatment at 800°C for 0.5 h. The Ti-15Mo-13Nb and Ti-15Mo-19Nb alloys presented the lowest and highest microhardness values, respectively, which is related to the increased niobium content. Niobium acts as a grain refiner and helps to reduce the grain size in the alloy’s microstructure. The fine-grained Ti-15Mo-19Nb sample has smaller grains and consequently higher microhardness, making it more resistant than the coarser-grained Ti-15Mo-13Nb sample. This is because the former has a larger total grain boundary area to impede the movement of dislocations [

52]. Regarding the microhardness values evaluated in this study, it is also interesting to note that the values found are higher than those of the commercial alloys evaluated by Wataru et al.[

53] as shown in

Table 5. This increase in microhardness compared to commercial alloys indicates that the samples produced have superior mechanical strength.

Table 5 also compares the microhardness values after cold forging and after heat treatment. The microhardness of Ti-15Mo-xNb (x = 13, 16, 19 wt.%) alloys decreased following the heat treatment at 800°C for 0.5 hours. This decrease is probably related to the coalescence of grains in the samples after heat treatment, which reduces their effectiveness in hindering dislocation movement during plastic deformation. As a result, the material becomes less resistant to compressive deformation and consequently less hard.

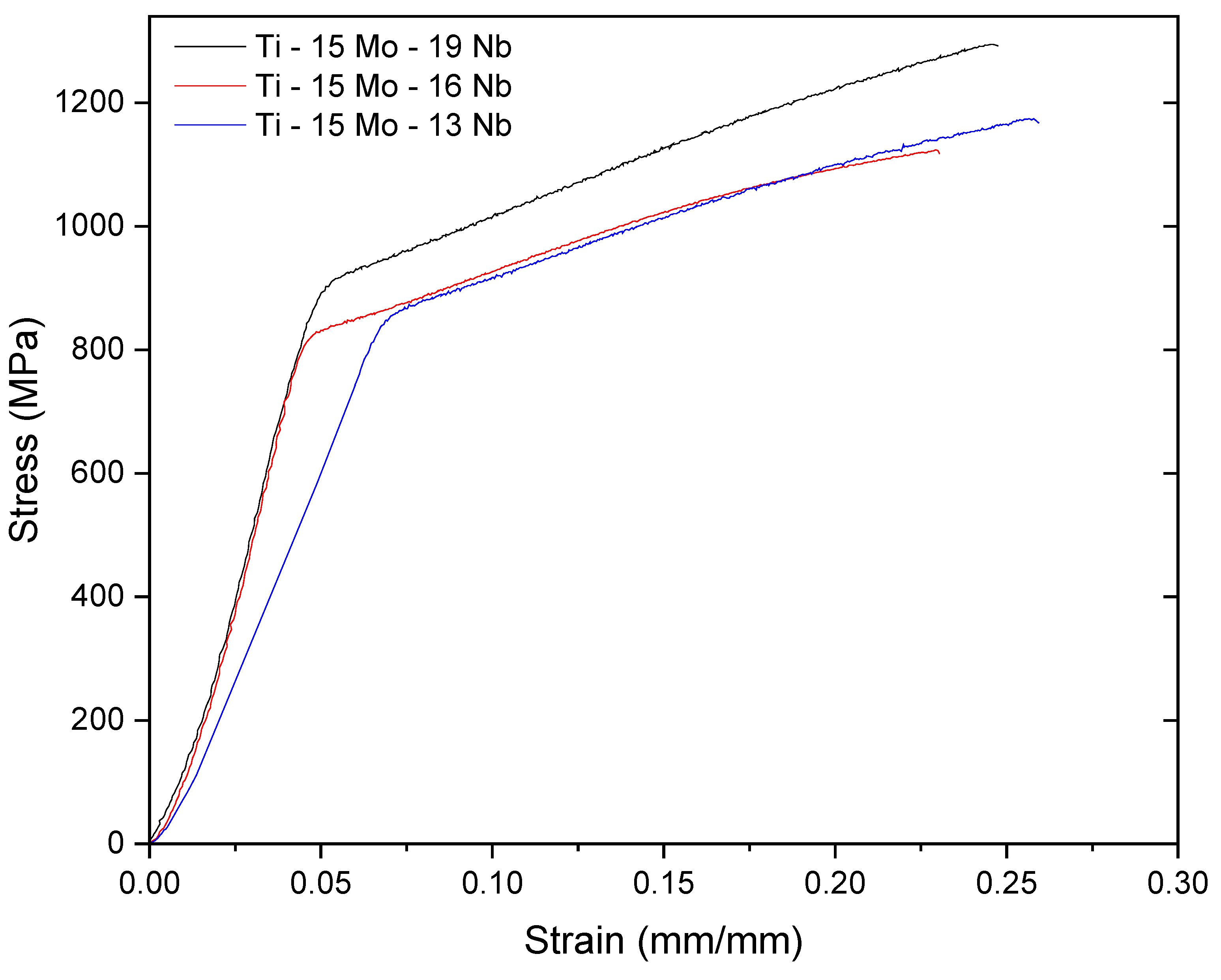

Figure 5 shows the stress-strain curves for the Ti-15Mo-xNb (x = 13, 16, 19 wt.%) alloys after heat treatment (800°C for 0.5 hours) obtained from compression tests at room temperature. The addition of niobium increases the strength of Ti-15Mo-xNb (x = 13, 16, 19 wt.%) alloys while maintaining their ductility. Li et al.[

54] also observed an increase in strength with the addition of Nb in Ti-Mo-Nb alloys. The yield strength (σₑ) and 0.2% offset yield strength (σ₀.₂) obtained from the stress-strain curves are listed in

Table 3. The Ti-15Mo-13Nb alloy has the lowest σₑ (740 MPa) and σ₀.₂ (845 MPa), while the Ti-15Mo-19Nb alloy has the highest σₑ (792 MPa) and σ₀.₂ (905 MPa) among the alloys studied. Indeed, both σₑ and σ₀.₂ values increase with higher Nb content. Thus, the addition of Nb not only stabilizes the β phase in the alloys but also increases strength while maintaining ductility. Comparing the Ti-15Mo-xNb (x = 13, 16, 19 wt.%) alloys after heat treatment (800°C for 0.5 h) with their compression test results at room temperature, it is evident that the Ti-15Mo-19Nb alloy, which presents the highest Vickers microhardness, also exhibits a steeper compression curve, with higher yield strength and ultimate compressive strength values and lower total strain, as shown in

Figure 5.

In the Ti-15Mo-19Nb alloy, the increase in yield strength, compressive strength, and ultimate tensile strength is associated with solid solution hardening (Mo and Nb) of the β phase, as well as the contribution of precipitation hardening from the α” phase during plastic deformation of the materials.

Adding Nb to the composition promotes the formation of these structures, resulting in increased hardness and strength of the materials. During the compression tests of the Ti-15Mo-xNb (x = 13, 16, 19 wt.%) alloys after heat treatment at 800ºC for 0.5 h the formation of dislocations in the microstructure of the materials also contributes to strain hardening. In particular, the combination of improved mechanical properties with solid solution strengthening and grain size refinement is evident. Alloys with higher Nb contents have smaller grain sizes (

Figure 2). During plastic deformation, dislocation movement occurs across grain boundaries. The atomic disorder at these boundaries contributes to additional mechanical strength by impeding dislocation slip. The Ti-15Mo-19Nb alloy exhibits higher yield strength and compressive strength when compared to the Ti-6Al-4V alloy while maintaining a transverse coefficient of thermal expansion similar to the CP Ti alloy, as shown in

Table 6 and

Table 7.

The Youn

g’s modulus of the designed alloys as a function of Nb concentration is shown in

Table 6. A slight increase in Youn

g’s modulus is observed with the addition of Nb [

55,

56], where a decrease in the network parameter of the β-phase is reported for Nb concentrations of 19% in Ti alloys. This occurs because the β phase is stabilized and the atomic bond energy increases, resulting in a smaller lattice parameter [

57,

58]. Despite the relatively low Youn

g’s modulus of these alloys, the higher Vickers hardness observed in all samples under the same processing conditions is consistent with the X-ray diffraction results [

59]. (

Figure 1b) shows the Ti-15Mo-13Nb alloy, indicating an extremely low presence of the metastable α

” phase, which may be responsible for maintaining the lower Youn

g’s modulus value. In the α

’’ (orthorhombic) crystal structure, the titanium atoms, almost 2/3 of which are located further apart in a lattice parameter

, provide a lower attraction force between the Ti-β atoms. There is a tendency for the Youn

g’s modulus to decrease with the addition of β-stabilizing elements in Ti alloys, as observed by Zhang et al.[

11], Correa et al.[

60], Kuroda et al.[

61] and Martins Júnior et al.[

62].

The Ti–15Mo–13Nb alloy (66 ± 2 GPa) has the lowest elastic modulus value among the studied samples, closer to human cortical bone (∼30 GPa), another favorable condition for applying this alloy as a biomaterial for implants [

63].

Ti β-alloys tend to have the lowest values of elastic modulus and hardness, and since Nb is a stabilizing element of this phase, the two mechanical properties studied vary in the same proportion. Thus, a good parameter to evaluate the best mechanical performance of Ti alloys with Nb is calculating the hardness/modulus (H/E) ratio [

64].

The H/E ratio is proportional to the wear resistance of alloys, which is related to the elastic deformation of the material. Materials with high wear resistance have a longer service life[

65]. To calculate the H/E ratio, Eq. 7 was used to convert the HV values to GPa.

Table 6 shows the results of the calculated H/E for the studied alloys. Previous studies have indicated that materials with a H/E ratio ≥0.04 exhibit good wear resistance [

66]. The Ti–15Mo–13Nb, Ti-15Mo-16Nb and Ti–15Mo–19Nb samples showed results higher than 0.04, possibly showing adequate wear resistance for a metallic biomaterial[

67]. The Ti–15Mo–19Nb alloy showed the best H/E ratio (0.055 ± 0.005).

Table 6.

Compression properties values of Ti-15Mo-xNb alloy specimens (x = 13, 16 and 19 wt.%) after heat treatment at 800°C for 0.5h and H/E ratio of the alloys as a function of Nb content.

Table 6.

Compression properties values of Ti-15Mo-xNb alloy specimens (x = 13, 16 and 19 wt.%) after heat treatment at 800°C for 0.5h and H/E ratio of the alloys as a function of Nb content.

| Alloy |

Yield Strength [MPa] |

Young’s Modulus [GPa] |

Compressive Strength [MPa] |

Strain [mm/mm] |

Tranverse Thermal Expansion Coeficient [mm/mm] |

H/E |

| Ti-15Mo-13Nb |

845±36 |

66±2 |

1121.2±49 |

0.2517 |

0.19 |

0.046± 0.006 |

| Ti-15Mo-16Nb |

826±23 |

69±3 |

1172.7±19 |

0.2311 |

0.20 |

0.051± 0.004 |

| Ti-15Mo-19Nb |

905±27 |

75±2 |

1295.6±30 |

0.2458 |

0.15 |

0.055± 0.005 |

Table 7.

Compression properties of Cp-Ti and its commercial alloys [58.59].

Table 7.

Compression properties of Cp-Ti and its commercial alloys [58.59].

| Alloy |

|

Yield Strength [Mpa] |

Young’s Modulus [GPa] |

Compressive Strength [Mpa] |

Tranverse Thermal Expansion Coeficient [mm/mm] |

H/E |

| Cp-Ti [68] |

|

692 |

104 |

785 |

0.15 |

0.019 |

| Ti-13Nb-13Zr [69] |

|

836 |

84 |

973 |

0.10 |

0,035 |

| Ti-6Al-4V [70] |

|

860 |

111 |

1036 |

0.12 |

0,024 |

4. Conclusions

Based on the results of this study, the following conclusions can be drawn:

The processing route and parameters used to prepare the Ti-15Mo-xNb alloys (x = 13, 16, 19 wt.%) after heat treatment at 800°C for 0.5 h produced homogeneous materials.

The β-Ti phase was predominantly formed in the Ti-15Mo-xNb alloys (x = 13, 16, 19 wt.%) in the molten state after heat treatment by quenching. The alloys were composed of β-Ti matrices. The Ti-15Mo-13Nb alloy showed an extremely low presence of dispersed α” precipitates.

By determining the lattice parameter, crystallite size and microdeformation, it was observed that the microdeformation changed from tensile (0.244%) to compressive (-0.2916% and -0.3292%) with the increase in Nb content, affecting the Young’s modulus from 66 GPa to 75 GPa, respectively.

Increasing the amount of Nb in the nominal composition, and consequently a β-Ti matrix in the microstructure of the alloy, resulted in higher values of Vickers microhardness, yield strength, compressive strength and tensile strength of these alloys, along with a reduction in total deformation and Young’s modulus.

The β Ti-15Mo-xNb alloys (x = 13, 16, 19 wt.%) exhibited superior mechanical properties compared to the CP Ti, Ti-13Nb-13Zr, and Ti-6Al-4V alloys using metastable phase precipitation strengthening mechanisms.

The high hardness of the heat treated Ti-15Mo-13Nb alloy gave this sample a good H/E ratio result 0,046, indicating possible good wear resistance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.M. and L.F.; methodology, H.M. and P.C.; software, E.B. and K.S.; validation, E.B. and K.S.; formal analysis, H.M. and P.C.; investigation, H.M.; resources, H.M. and L.F.; data curation, H.M.; writing—original draft preparation, H.M.; writing—review and editing, E.B., P.C., and G.S.; visualization, E.B. and K.S.; supervision, G.S.; project administration, H.M.; funding acquisition, H.M. and L.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors would like to thank the support for this research provided by the Brazilian Federal Government and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) and CAPES for financing this research.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the support for this research provided by the university EEL-USP for the material donation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interest or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Xu, L.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Z.; Kong, F. The microstructure and properties of Ti-Mo-Nb alloys for biomedical application. J. Alloy Compd 2024, 453, 320–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymski, D.; Walter, N.; Hierl, K.; Rupp, M.; Alt, V. Direct hospital costs per case of periprosthetic hip and knee joint infections in Europe—A systematic review. J. Arthroplasty 2024, 39, 1876–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marin, E.; Lanzutti, A. Biomedical applications of titanium alloys: A comprehensive review. Materials 2024, 17, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, S.; Yue, X.; Wang, H. Predictability of different machine learning approaches on the fatigue life of additive-manufactured porous titanium structure. Metals 2024, 14, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.J.; Choi, Y.S.; Hwang, Y.H.; Cho, H.W.; Lee, D.G. Biocompatibility and Biological Corrosion Resistance of Ti-39Nb-6Zr+0.45Al Implant Alloy. J Funct Biomater. 2021, 12, 10002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihalcea, E.; Vergara-Hernández, H.J.; Jimenez, O.; Olmos, L.; Chávez, J.; Arteaga, D. Design and characterization of Ti6Al4V/20CoCrMo–highly porous Ti6Al4V biomedical bilayer processed by powder metallurgy. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2021, 31, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Liu, S.; Sun, Z.; Li, K.; Su, N.; Yang, G. In situ X-ray imaging and quantitative analysis of balling during laser powder bed fusion of 316L at high layer thickness. Mater. Des. 2024, 113, 113442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Ding, X.; Zhang, H.; Hu, T.; Xu, S.; Duan, P.; Huang, B. Topology optimization of embracing fixator considering bone remodeling to mitigate stress shielding effect. Med. Eng. Phys. 2024, 125, 104122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehtemam-Haghighi, S.; Liu, Y.J.; Cao, G.H.; Zhang, L.C. Phase transition, microstructural evolution, and mechanical properties of Ti-Nb-Fe alloys induced by Fe addition. Mater. Des. 2016, 97, 279–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Che, L.; He, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, P.; Li, X. Preparation of High-Quality Mo-Nb (Ti/Ni-Ti) Sputtering Target by Hot Isostatic Pressing. Materials Research Proceedings, 2023, 38, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kent, D.; Wang, G.; John, D.S.; Dargusch, M. An investigation of the mechanical behaviour of fine tubes fabricated from a Ti-25Nb-3Mo-3Zr-2Sn alloy. Mater. Des. 2015, 85, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Elaziem, W.; Darwish, M.A.; Hamada, A.; Daoush, W.M. Titanium-based alloys and composites for orthopedic implants applications: A comprehensive review. Mater. Des. 2024, 241, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wu, M.; Huang, X.; Zhang, L.; Qu, X. Investigations of the microstructure and mechanical properties of the Nb-Ti/Nb-Ti-Ni brazed joints. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 35, 352–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, H.C.; Hsu, S.K.; Wu, S.C.; Lee, C.J.; Ho, W.F. Structure and mechanical properties of as-cast Ti–5Nb–xFe alloys. Mater. Charact. 2010, 61, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.K.; Kim, J.Y.; Hwang, M.J.; Song, H.J.; Park, Y.J. Effect of Nb on the microstructure, mechanical properties, corrosion behavior, and cytotoxicity of Ti-Nb alloys. Materials 2015, 8, 5986–6003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.J.; Xiao, S.L.; Jing, T.; Chen, Y.Y.; Huang, Y.D. Microstructure and dry wear properties of Ti-Nb alloys for dental prostheses. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2019, 19, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Chang, K.; Ebel, T. Microstructure and mechanical behavior of metal injection molded Ti–Nb binary alloys as biomedical material. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2013, 28, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Xiao, W.; Ren, L.; Fu, Y.; Ma, C. The roles of oxygen content on microstructural transformation, mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of Ti-Nb-based biomedical alloys with different β stabilities. Mater. Charact. 2021, 176, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, W.; Han, C.; Choma, T. Effect of Nb content on microstructure, property and in vitro apatite-forming capability of Ti-Nb alloys fabricated via selective laser melting. Mater. Des. 2017, 126, 268–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banumathy, S.; Prasad, K.S.; Mandal, R.K.; Singh, A.K. Effect of thermomechanical processing on evolution of various phases in Ti-Nb alloys. Bull. Mater. Sci. 2011, 34, 1421–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidaux, J.E.; Pasquier, R.; Rodriguez-Arbaizar, M. Low elastic modulus Ti–17Nb processed by powder injection moulding and post-sintering heat treatments. Powder Metall. 2014, 57, 320–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.F.; Rossi, M.C.; Vidilli, A.L.; Amigó Borrás, V.; Afonso, C.R.M. Assessment of β stabilizers additions on microstructure and properties of as-cast β Ti-Nb based alloys. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 22, 3511–3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calazans Neto, J.V.; Celles, C.A.; de Andrade, C.S.; Afonso, C.R.; Nagay, B.E.; Barão, V.A. Recent advances and prospects in β-type titanium alloys for dental implants applications. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2024, 10, 6029–6060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Kim, J.H.; Kang, S.W.; Kim, J.H.; Nam, T.H.; Yeom, J.T. Superelastic metastable Ti-Mo-Sn alloys with high elastic admissible strain for potential bio-implant applications. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2023, 163, 45–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvaro, Mariana; Oliveira, Joao; Rezende, Monica; Santana, Ana; Almeida, Luiz; Borborema, Sinara. Mechanical characterization of homogenized ti-12mo-13nb and ti-10mo-20nb alloys. Revista Contemporânea. 2024, 4, e6451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, F.; He, X.; Lv, Y.; Wu, M.; He, X.; Qu, X. Selective laser sintered porous Ti-(4–10)Mo alloys for biomedical applications: Structural characteristics, mechanical properties and corrosion behaviour. Corros. Sci 2015, 95, 117–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chu, K.; He, S.; Wang, B.; Zhu, W.; Ren, F. Fabrication of high strength, antibacterial and biocompatible Ti-Mo-5Ag alloy for medical and surgical implant applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2020, 106, 110165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narushima, T. New-generation metallic biomaterials. In Metals for Biomedical Devices 2019, 55, 495–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, Giovana Collombaro; Kuroda, Pedro Akira Bazaglia; Grandini, Carlos Roberto. Influence of Nb addition on the structure, microstructure, Vickers microhardness, and Young’s modulus of new β Ti-xNb-5Mo alloys system, Journal of Materials Research and Technology, 2023, 25, 3061–3070. [CrossRef]

- Guo, Shun; Meng, Qingkun; Liao, Guangyue; Hu, Liang; Zhao, Xinqing. Microstructural evolution and mechanical behavior of metastable β-type Ti–25Nb–2Mo–4Sn alloy with high strength and low modulusMicrostructural evolution and mechanical behavior of metastable β-type Ti–25Nb–2Mo–4Sn alloy with high strength and low modulusretain. Progress in Natural Science: Materials International 2013, 23, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, L.P.; Kim, H.Y.; Hosoda, H.; Miyazaki, S. Effect of Nb content and heat treatment temperature on superelastic properties of Ti-24Zr-(8–12)Nb-2Sn alloys. Scr. Mater. 2014, 95, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandiran, N.; Asgari, H.; Dibia, F.; Eybel, R.; Muhammad, W.; Gerlich, A.; Toyserkani, E. Effects of post heat treatment on microstructure and mechanical properties of Ti5553 parts made by laser powder bed fusion. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 938, 168616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.B.; Wang, K.Z.; Xu, L.J.; Xiao, S.L.; Chen, Y.Y. Effect of Nb addition on microstructure, mechanical properties, and castability of β-type Ti-Mo alloys. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China, 2015, 25, 2214–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borborema, Sinara & Ferrer, Vitor & Rocha, Adriana & Cossu, Caio & Nunes, Aline Raquel & Nunes, Carlos & Malet, Loic & Almeida, Luiz. Influence of Nb Addition on α″ and ω Phase Stability and on Mechanical Properties in the Ti-12Mo-xNb Stoichiometric System. Metals, 2022, 12, 1508. [CrossRef]

- Standard Test Method for Microindentation Hardness of Materials; ASTM E 384-22; American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- Standard Test Methods of Compression Testing of Metallic Materials at Room Temperature, ASTM E9-19, American Society for Testing and Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2019.

- ASTM. F2066-23: Standard specification for wrought titanium-15 molybdenum alloy for surgical implant applications (UNS R58150). ASTM International 2023. [CrossRef]

- Yong, Niu, Zhi-qiang, Hong, Yao-qi, Wang, Yanhui, Zhu. Machine learning-based beta transus temperature prediction for titanium alloys. Journal of materials research and technology, 2022, 23, 515–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damian, Kalita., K., Mulewska., I., Jóźwik., Agata, Zaborowska., M., Gawęda., W., Chromiński., K., Bochenek., Ł., Rogal. Metastable β-Phase Ti–Nb Alloys Fabricated by Powder Metallurgy: Effect of Nb on Superelasticity and Deformation Behavior. Metallurgical and Materials Transactions 2024. [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.F.; Rossi, M.C.; Vidilli, A.L.; Amigó Borrás, V.; Afonso, C.R.M. Assessment of β stabilizers additions on microstructure and properties of as-cast β Ti–Nb based alloys. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 22, 3511–3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, J.; Hastings, G. Titanium and titanium alloys. Handbook of Biomaterial Properties 1998, 24, 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babanli, M.; Huseynov, S.; Demchenko, L.; Huseynov, V.; Titenko, A. Effect of Low-Temperature Aging on Mechanical Behavior of Metastable β-Type Ti-Mo-Sn Alloys. IEEE 12th International Conference Nanomaterials: Applications & Properties (NAP), 2022, 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Kaur, M.; Singh, K. Review on titanium and titanium-based alloys as biomaterials for orthopaedic applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 102, 844–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathebula, C.; Matizamhuka, W.; Bolokang, A.S. Effect of Nb content on phase transformation, microstructure of the sintered and heat-treated Ti (10–25) wt.% Nb alloys. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 108, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cullity, B.D.; Smoluchowski, R. Elements of X-ray diffraction. Phys. Today 1957, 10, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivakumar, M.; Dasgupta, A.; Ghosh, C.; Sornadurai, D.; Saroja, S. Optimisation of high energy ball milling parameters to synthesize oxide dispersion strengthened Alloy 617 powder and its characterization. Adv Powder Technol 2019, 30, 2320–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabiei, M.; Palevicius, A.; Dashti, A.; Nasiri, S.; Monshi, A.; Vilkauskas, A.; Janusas, G. Measurement modulus of elasticity related to the atomic density of planes in unit cell of crystal lattices. Materials, 2020, 13, 4380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanapaakala, G.; Subramani, V. A Review on β-Ti Alloys for Biomedical Applications: The Influence of Alloy Composition and Thermomechanical Processing on Mechanical Properties, Phase Composition, and Microstructure. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part L: Journal of Materials: Design and Applications, 2023, 237, 1251–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Yan, H.; Wang, Z.; Wang, K.; Yves, N.I.; Tong, Y. Effects of Mo content on the microstructure and mechanical properties of TiNbZrMox high-entropy alloys. Journal of Alloys and Compounds, 2023, 930, 167373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.F.; Rossi, M.C.; Vidilli, A.L.; Borrás, V.A.; Afonso, C.R.M. Assessment of β stabilizers additions on microstructure and properties of as-cast β Ti–Nb based alloys. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 22, 3511–3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoemmes, A.; Bataev, I.A.; Lazurenko, D.V.; Ruktuev, A.A.; Ivanov, I.V.; Afonso, C.R.M.; Jorge, A.M. Microstructure and lattice parameters of suction-cast Ti–Nb alloys in a wide range of Nb concentrations. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2021, 818, 141378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Z.; Zhang, D.; Guo, L.; Lin, J.; Li, Y.; Wen, C. Spinodal Zr–Nb alloys with ultrahigh elastic admissible strain and low magnetic susceptibility for orthopedic applications. Acta Biomaterialia 2024, 184, 444–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wataru, T.; Akiyama, Y.; Koyano, T.; Miyazaki, S.; Kim, H.Y. Martensitic transformation and shape memory effect of TiZrHf-based multicomponent alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 931, 167496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Ma, X.; Tong, T.; Wang, Y. Microstructural and mechanical properties of β-type Ti–Mo–Nb biomedical alloys with low elastic modulus. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 815, 152412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez, J.A.; Deshmukh, A.J.; Robinson, J.; Cornell, C.N.; Rasquinha, V.J.; Ranawat, A.S.; Ranawat, C.S. Reproducible fixation with a tapered, fluted, modular, titanium stem in revision hip arthroplasty at 8–15 years follow-up. J. Arthroplasty 2024, 29, 214–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, P.; Tian, F.; Wang, Y. Effect of Mo on the phase stability and elastic mechanical properties of Ti–Mo random alloys from ab initio calculations. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2017, 29, 435703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nnamchi, P.S.; Obayi, C.S. A novel combinatorial design strategy for biomedical Ti-based alloys. Irish Int. J. Eng. Sci. Stud. 2022, 5, 4, https://aspjournals.org/Journals/index.php/iijess/article/view/103. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Song, B.; Choi, S.K.; Shi, Y. A topology strategy to reduce stress shielding of additively manufactured porous metallic biomaterials. Int. J. Mech. Sci. 2021, 197, 106331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yueyan Tian, Ligang Zhang, Di Wu, Renhao Xue, Zixuan Deng, Tianlong Zhang, Libin Liu. Achieving Stable Ultra-Low Elastic Modulus in Near-β Titanium Alloys through Cold Rolling and Pre-Strain. Acta Materialia 2025, 120726. [CrossRef]

- Correa, D.R.N.; Rocha, L.A.; Donato, T.A.G.; Sousa, K.S.J.; Grandini, C.R.; Afonso, C.R.M.; Hanawa, T. On the mechanical biocompatibility of Ti-15Zr-based alloys for potential use as load-bearing implants. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 1241–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuroda, Pedro Akira Bazaglia; Cardoso, Giovana Collombaro; Grandini, Carlos Roberto. The effect of Nb on the formation of TiO2 anodic coating oxide on Ti–Nb alloys through MAO treatment. Journal of Materials Research and Technology, 2024, 29, 1165–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins Júnior, J.R.S.; Matos, A.A.; Oliveira, R.; Buzalaf, M.A.R.; Costa, I.; Rocha, L.A.; Grandini, C.R. Preparation and characterization of alloys of the Ti–15Mo–Nb system for biomedical applications. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. Part B: Appl. Biomater. 2018, 106, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, M.-K.; Kim, J.-Y.; Hwang, M.-J.; Song, H.-J.; Park, Y.-J. Effect of Nb on the Microstructure, Mechanical Properties, Corrosion Behavior, and Cytotoxicity of Ti-Nb Alloys. Materials. 2015, 8, 5986–6003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, A.R.V.; Gabriel, S.B.; Nunes, C.A.; Araújo, L.S.; Baldan, R.; Mei, P.; Almeida, L.H.D. Microstructure and mechanical properties of Ti-12Mo-8Nb alloy hot swaged and treated for orthopedic applications. Materials Research. 2017, 20, 526–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Shizhong, and Liujie Xu. Review on research progress of steel and iron wear-resistant materials. Acta Metall Sin. 2019, 4, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozan, S.; Lin, J.; Li, Y.; Ipek, R.; Wen, C. Development of Ti-Nb-Zr alloys with high elastic admissible strain for temporary orthopedic devices. Acta Biomater. 2015, 20, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jinfeng Ling, Dandan Huang, Kewu Bai, Wei Li, Zhentao Yu, Weimin Chen, High-throughput development and applications of the compositional mechanical property map of the β titanium alloys. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2021, 71, 201–210. [CrossRef]

- Standard Specification for Unalloyed Titanium for Surgical Implant Applications (UNS R50250, UNS R50400, UNS R50550, UNS R50700); ASTM F67–24; American Society for Testing Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2024.

- Standard Specification for Wrought Titanium-13Niobium-13Zirconium Alloy for Surgical Implant Applications (UNS R58130); ASTM 1713-21; American Society for Testing Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- Standard Specification for Wrought Titanium-6 Aluminum-4 Vanadium ELI (Extra Low Interstitial) Alloy for Surgical Implant Applications (UNS R56401); ASTM F136–13; American Society for Testing Materials: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2013.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).