1. Introduction

Recent global concerns regarding environmental sustainability and public health have underscored the need for wellness businesses to embrace innovative service practices (Adams, Jeanrenaud et al. 2016). While tourism development can foster economic, social, and environmental benefits in destinations worldwide (Hall 2008), it often brings challenges, including rising living costs, congestion, cultural heritage deterioration, and shifts in local lifestyles (Erul, Uslu et al. 2023). It is essential to integrate the perspectives of multiple stakeholders into sustainable development strategies for the tourism industry (Erul, Uslu et al. 2023).

Wellness tourism is travel to maintain or enhance personal well-being (GWI 2023). The wellness tourism destination contains a core and support area, which should have strong functional connections. The core area has unique resource advantages, while the support area can provide an industrial linkage platform for the core area and strong guarantees for public service systems such as public leisure, information consultation, tourism safety, and leisure education (NTA 2016). Wellness tourism champions the long-term sustainability of environmental resources and the welfare of stakeholders (Wiltshier 2020). The industry must actively involve local communities in decision-making processes, prioritize the protection of resources, and recognize the significant challenges these communities encounter during development, especially in wellness tourism (Moayerian, McGehee et al. 2022). The cultural resource endowments of wellness tourism destinations can protect cultural heritage resources and revitalize resource elements by developing the wellness industry (Liu, Wang et al. 2022). Sustainable management of cultural heritage resources requires a collaborative approach incorporating diverse input from all segments of society, including government, local communities, tourism organizations, and visitors (Roodbari and Olya 2024, Wang, Damdinsuren et al. 2024). This engagement fosters value co-creation among stakeholders, which is essential for the long-term success of wellness tourism and facilitates the transition from theory to practical implementation (Li, Myagmarsuren et al. 2023).

Community support for service innovation is crucial for its success, leading to significant research on its determinants. Studies show that a sense of place fosters meaningful memories and connections. Place attachment develops through place-based identity and dependence, helping individuals form self-identities aligned with specific community goals (Proshansky 1983, Cross, Keske et al. 2011). Generativity also influences intentions to preserve environments, driven by emotional ties to destinations and anticipated benefits of sustainable (Han, Olya et al. 2024). These elements collectively form the basis for residents’ emotional engagement in sustainable initiatives.

Despite this understanding, some scholars emphasize the need for a deeper exploration of service innovation performance from the residents’ perspective (Kabus and Dziadkiewicz 2022). They advocate for a refined understanding of how place attachment and generativity translate into motivation, perceived value, and engagement behaviors (Wang, Yao et al. 2023, Han, Olya et al. 2024). This insight is essential for effectively leveraging the factors to encourage residents’ support for service innovation in wellness tourism.

Service innovation represents organizations‘ care about future production capacity and engagement in practical activities that benefit long-term sustainable development (Gustafsson, Snyder et al. 2020). Service innovation motivates community residents‘ intentions to cooperate in ways that preserve their cultural environment and their concern for valuable, sustainable utilization for generations. This dynamic motivation creates an essential link between the generative-based community concept and resident engagement in sustainable development. In contrast, earlier studies have examined the influence of service innovation in the wellness tourism sector, such as destination attraction (Andreu, Font-Barnet et al. 2021), industry performance (Li, Myagmarsuren et al. 2023), employment of community residents (Page, Hartwell et al. 2017), and sustainable development of tourism communities (Esfandiari and Choobchian 2020). There is limited investigation into the relationship between generative-based community engagement and service innovation from residents‘ perspective.

This study seeks to develop and validate a framework examining different factors that affect service innovation from residents’ perspectives to fill this research gap. The research poses three key questions: (1) How does place attachment influence generativity? (2) In what ways does generativity influence residents’ engagement in service innovation? (3) What strategies can be implemented to effectively manage a generative-based community group to enhance sustainable development? This research takes Gongtan Town, southeast of Chongqing City, a small town with a thousand-year history surrounded by beautiful scenery of mountains and Wujiang River, as a case study to explore these questions. Specifically, this study analyses the questionnaire survey data from residents through a comprehensive examination, employing diverse methodologies such as structural equation modeling (SEM) and fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (fsQCA) to provide a nuanced understanding of the intricate relationships and potential synergies between the variables. Through a sustainability lens, this research advances theoretical insights into generative-based wellness tourism service innovation. Moreover, the findings offer critical guidance for practitioners and policymakers dedicated to enhancing and balancing sustainable development.

This overview investigates the realm of service innovation, emphasizing the principal theoretical frameworks identified in the literature. It is succeeded by meticulously describing the research methodologies employed, guaranteeing clarity and the possibility of replication. Afterward, the results section offers an extensive analysis utilizing SEM and fsQCA. Lastly, the discussion integrates these findings into the broader research context. The paper concludes this research by proposing future suggestions for service innovation, sustainable attempts, and implementation activities.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Service Innovation Theory

Innovation is a new product or process, an improved product or process, or a combination (MSTIA 2018). It represents a substantial departure from the unit’s prior products or processes. It is available to potential users (for products) or implemented in practice (for processes) by the respective enterprises (units). According to (Tidd and Hull 2003) research, innovation improves or redevelops products and services to survive. It manifested as endowing products with a new value or providing a unique service experience, such as business process innovation. Under the service-dominant logic (SDL), services are the basis of all economic exchanges, and products are the carriers for providing services (Lusch and Nambisan 2015). Therefore, services should not be a comparison of products, but services represent the exchange process’s general situation and are an expanded exchange concept (Lusch and Nambisan 2015). Subsequently, service innovation theory was extended from single-dimensional innovation to a value co-creation service ecosystem (Tran, Mai et al. 2021). In the research of the service innovation ecosystem, researchers must analyze not only the dynamic capabilities (Helfat and Peteraf 2003) from the resource-based view (RBV) (Wernerfelt 1984) but also the customer, competitor, inter-functional, market-oriented theory (Chikerema and Makanyeza 2021).

Moreover, the emerging prominence of the service-dominant logic and knowledge-based view as key frameworks in service innovation has led to a surge of interest among researchers, including individual, firm, and country levels (Chopra, Saini et al. 2021). Although the enables of service innovation have been extensively summarized, there is a growing interest in customer values (Heymann 2019), enterprise management (Schultz 2019), employee engagement (Schultz 2019), and community engagement (Anthony Jr 2024), which have been recognized and identified as critical to service innovation. Studies in management research underscore the significance of identifying essential factors and central themes from various angles. It includes developing new services, implementing service innovations, sustainability-driven approaches, and the influence of social media and information technology on digitization and service innovation (Peixoto, Paula et al. 2023).

2.2. Generativity Theory

Generativity is an individual’s desire to establish connections with and mentor the next generations during mid-adulthood (Escalona 1951). Kotre further developed and proposed that generativity reflects a person’s wish to invest in daily life and jobs that will benefit themselves and others even after dying (Kotre 1984), which emerges throughout an individual’s lifespan. In a cross-cultural study, some scholars identified various motivational sources and features of generativity, including cultural expectations, inner desires, concern for others, beliefs, commitment, actions, and storytelling (McAdams and de St Aubin 1992). Moreover, Gergen described generativity as the individual’s capacity to challenge the status quo, transform reality, and take action (Gergen 2009).

At its core, generativity encompasses the ability to originate, produce, or procreate, involving rejuvenating, reconfiguring, reframing, and revolutionizing processes. Rejuvenating and reconfiguring involve generating new configurations or altering existing possibilities, while reframing pertains to how we perceive and interpret the world (Slife and Richardson 2010). Conversely, revolution entails challenging established norms and practices (van Osch and Avital 2010, van Osch 2012). Hofer further proposed the positive relationships between inner desire, generative concern, and generative commitment in 2008, 2016, and 2020 (Hofer and Bond 2008, Villar, Serrat et al. 2024). Eventually, he tested the cross-cultural project on successful aging. He proposed that specific reminiscence functions motivate generative behavior, for example, using experience to solve a problem at hand, and further research finds the universal effects of implicit motive identity commitment and well-being(Hofer and Busch 2024). Moreover, the components of generativity have been conceptualized and examined in both specific domains and more general goals (e.g., community volunteerism), forms of engagement, and perceptions of achievement (Villar, Serrat et al. 2024). It coincides with the viewpoint of this study, which is the theoretical basis and antecedent variable for generative-based community sustainable development.

2.3. Place Attachment and Generativity

The concept of place offers individuals stability and a sense of meaning in their lives (Hallak, Brown et al. 2013). The interactions between people and their environments foster emotional connections, reinforcing that place is not merely a physical location but a significant center of human existence (Relph 1976, Lewicka 2011, Bonaiuto, Alves et al. 2016). Place attachment is the positive emotional bond individuals develop with a particular place (Altman and Low 1992), connected with human geography and environment psychology (Gu and Ryan 2008).

Stokols and Shumaker suggested that place attachment comprises two subdomains: place dependence (Stokols 1981), which reflects the functional role of a place in helping individuals meet their needs and achieve their goals, and place identity, which encompasses a resident’s beliefs, and sense of self-related to a specific location (Jorgensen and Stedman 2001). This duality indicates that place attachment is connected to generative actions to maintain the place’s current state (Han, Olya et al. 2024).

Furthermore, place attachment can enhance a specific tourism community’s social capital and cohesion and foster a sense of place stability among community residents (Zhang, Zhang et al. 2014) while promoting a positive awareness and desire to transmit culture and history. It is the essence of personal identity and pride in one’s place (Luo and Ren 2020). Thus, place attachment is an essential source of regional economic resilience for tourism communities facing long-term structural change, particularly in historical towns with millennia of heritage, as is the focus of this research (Bec, McLennan et al. 2016). Based on these insights, here propose the following two hypotheses:

H1. Place-based identity has a positive impact on resident generation capacity.

H2. Place-based dependence has a positive impact on resident generation capacity.

2.4. Generativity and Resident Engagement

Engagement has traditionally been examined from customers’ interactions with focal objects, such as firms or brands (Viglia, Pera et al. 2018). However, there is an emerging recognition that residents now have new opportunities to engage meaningfully in municipal decision-making processes related to community development (Friedman 2023). Insights from residents who are actively engaged in Resident Associations (RAs) or serve as executive officers of Resident Associations (RAEMs) can highlight strategies to make critical knowledge more accessible to the community, thereby enhancing residents’ ability to provide input and participate in local issues (Butt, Smith et al. 2021). Resident engagement is a complex and long-term process that fosters community members‘ inner connections and outer side relationships with society. Johnston proposed that this effort promotes the sharing and learning of social knowledge, enhances awareness of hazard risks, accesses necessary resources for hazard response, and maintains a social orientation that emphasizes helping each other (Johnston, Taylor et al. 2024). Generativity promotes individual participation in social learning and experiences, leading to shared responsibility.

Research has shown that generativity positively influences resident engagement (Guo, Zhang et al. 2018). For instance, (Luo and Ren 2020) examined how generativity affects residents’ hopes and expectations regarding the heritage site’s conservation and restoration in tourism destinations. This finding implies that fostering generativity toward future generations influences residents’ value perceptions, affecting their capabilities, engagement motivations, and behaviors in engagement and development efforts, particularly in community-based sustainable development. Therefore, here is the proposed following hypothesis:

H3. Generativity toward future generations positively influences residents’ engagement behaviors.

2.5. Generativity, Resident Engagement, and Service Innovation

Various factors drive service innovation, and for residents, the ultimate goal is to achieve environmental sustainability while enhancing their quality of life. Previous studies have indicated that community-based sustainable development is influenced by residents’ perceptions and the value co-creation among tourism companies’ residents, tourists, and employees (Li, Myagmarsuren et al. 2023). For instance, Lee proposed that resident engagement enhances the perceived benefits of tourism development, positively contributing to residents’ engagement behavior (Lee 2013). Similar findings have been reported in subsequent studies (Luo and Ren 2020, Kim, Hall et al. 2021), demonstrating that residents are concerned about the future impacts of cultural and environmental protection on their living environment and that these concerns significantly shape their engagement behavior. Therefore, here is the proposed following hypothesis:

H4. Generativity positively influences service innovation performance.

This hypothesis suggests that fostering a sense of generativity, where residents feel responsible for supporting future generations, can improve service innovation performance, ultimately aligning with community development goals. Community sustainable development is also motivated by their engagement behavior, mainly based on their motivation and value perception and depending on their capability (Han, Olya et al. 2024). There is a correlation between motivation, value perception, and values and support for environment protection policies (Sharpe, Perlaviciute et al. 2021). Indeed, individuals’ concern for cultural and environmental protection and their actual engagement in service innovation stem from generative ideas and place attachment (Brown 2014). This connection naturally aligns with the principles of community-based sustainable development. Therefore, here is the proposed following hypothesis:

H5. Residents’ engagement positively influences service innovation performance.

The hypotheses suggest that enhancing motivation, value perception, and place attachment among residents can lead to more significant support for cultural environmental protection policies and increased involvement in service innovation efforts to achieve sustainable development outcomes.

2.6. Moderating Effect of Digital Technology and Knowledge Management System

When RAs and RAEMs initially developed the concept of community engagement, they analyzed the knowledge formed progress in the community. Scholars focusing on community engagement have claimed that resident engagement influences digital technology innovation through generative (Hopkins, Tidd et al. 2011, Bird, McGillion et al. 2021).

However, some studies have demonstrated that variations in individual engagement can arise from using digital technology and knowledge management systems. For instance, digital technology can enhance communication and collaboration among residents, tourists, and stakeholders, thus facilitating the co-creation process and enabling more effective sharing of knowledge and resources. Knowledge management systems can further support individuals by providing access to relevant information and expertise, enabling them to engage more meaningfully in cultural, environmental protection, and service innovation initiatives. These tools can shape how individuals interact with their environment and each other, influencing their levels of engagement in initiatives without geographical restrictions between generative (Cennamo, Dagnino et al. 2020). Therefore, here is the proposed following hypothesis:

H6. Digital technology positively influences resident engagement.

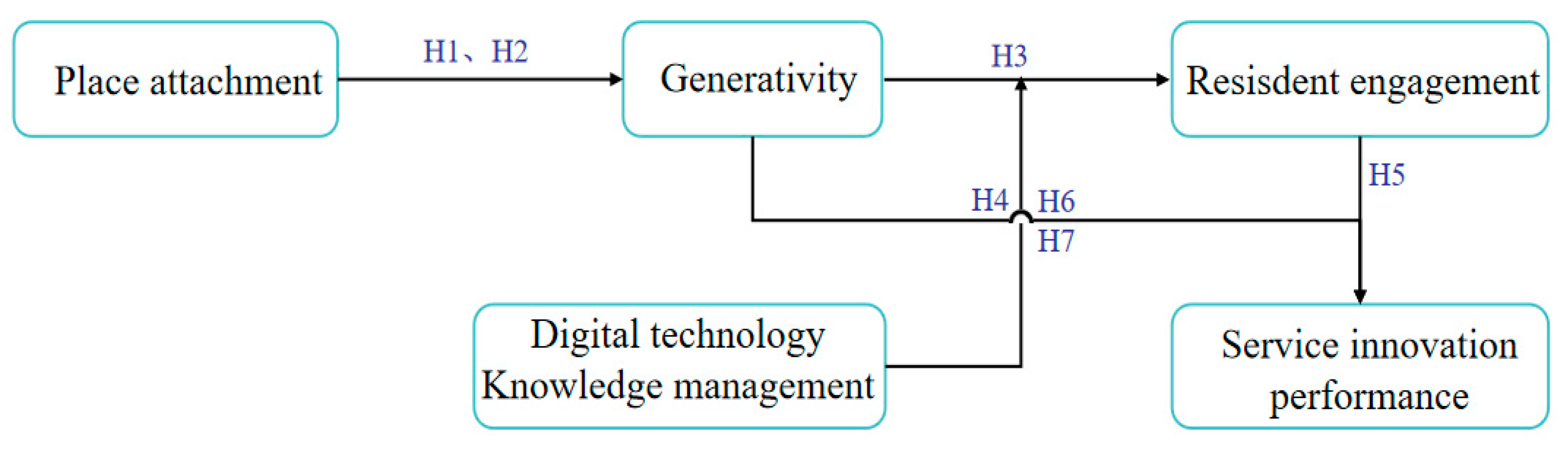

Some studies found knowledge management differences in resident engagement. Schmitt proposed that a knowledge management system promotes community knowledge transactions between generativity (Schmitt 2020). Muniz also found that a knowledge management system develops residents‘ communication capability with tourists (Muniz, Dandolini et al. 2021). These studies explained that knowledge management systems as external environmental conditions are concerned about the community knowledge flow, influencing the generativity-based community’s service ecosystem. Thus, the hypothesis about the knowledge management system’s influence on the residents‘ behavior is as follows. The research model of this research is shown in

Figure 1.

H7. knowledge management positively influences resident engagement.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. The Research Site

Gongtan Town, west of Youyang in Chongqing City, exemplifies cultural-based wellness tourism in China. This town is celebrated for its rich cultural heritage, breathtaking natural landscapes, and unique local traditions, making it an appealing destination for those seeking wellness experiences grounded in culture. Visitors to Gongtan town can enjoy a range of traditional Chinese therapeutic practices, including herbal medicine, acupuncture, and tai chi, all of which have been integrated into wellness programs designed to enhance physical and mental well-being. The town also offers immersive cultural experiences, such as participating in local festivals, exploring historical sites, and savoring regional cuisine, all of which contribute to a holistic wellness experience.

Moreover, Gongtan’s commitment to preserving its cultural identity and natural environment is central to its tourism strategy. The local community maintains the town’s cultural authenticity while promoting sustainable tourism practices. This approach enriches the visitor experience and fosters a sense of pride and connection among residents, ultimately leading to more significant support for cultural heritage protection and sustainable initiatives. Therefore, Gongtan Town serves as a model for how cultural-based wellness tourism can thrive by intertwining wellness practices with cultural preservation and resident engagement in service innovation, thereby contributing to the sustainable development goals of the local area and the broader tourism industry in China.

3.2. Methods

This research employed a mixed-methods approach to analyze the research objectives concerning the promotion of service innovation. Initially, this research conducted a quantitative survey to collect residents’ perspectives, which aimed to test a conceptual model predicting residents‘ support for service innovation. Subsequently, expert interviews were conducted to understand better the interactions among variables and the mechanisms. More detailed descriptions of each method can be found as follows.

3.2.1. Quantitative Survey

This research utilized a quantitative approach through a questionnaire survey administered to residents of Gongtan, which consisted solely of closed-ended questions. The survey items assessed various dimensions relevant to service innovation of wellness tourism, including place attachment, generativity, factors influencing resident engagement, and service innovation performance.

Place attachment was measured through two dimensions: place-based identity (comprising four items) and place-based dependency (also four items), following the frameworks established by Chen and Ramkissoon (Ramkissoon, Smith et al. 2013, Chen, Tang et al. 2024). Generativity was evaluated in four parts, drawing on the work of Urien and Wells (Urien and Kilbourne 2011, Wells, Taheri et al. 2016). Many items measure the level of engagement among residents based on the methodology outlined by Wang (Wang, Wang et al. 2020). The category of service innovation performance encompassed a range of indicators, including financial, customer-related, and internal indicators, with twelve items adapted from Storey and Hsueh (Storey and Kelly 2002, Hsueh, Lin et al. 2013). This research utilized a five-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree) to rate the survey items, and a comprehensive overview of the items can be found in

Appendix A.

A professional translator translated all initial English-language items into Chinese to enhance the questionnaire’s accuracy and reliability. Subsequently, a back-translation was conducted to compare the original English version with the translated Chinese version. Three master students specializing in tourism management checked the items to assess their appropriateness for measuring individual support for service innovation. Following this, seven undergraduate students in tourism management participated in a preliminary survey to analyze their understanding of the questions and the time required to answer the questionnaire. This process makes the questionnaire understandable.

3.2.2. Sampling and Data Collection

From July 10 to September 24, 2024, this study conducted a snowball sampling technique among the residents of Gongtan town with the Raosoft sample size calculator for an ever-expanding set of potential respondents (Goldenberg, Han et al. 2009, Stevens, Loudon et al. 2013). This method calculates the valid collection data from many respondents within a 5% margin of error, 95% confidence level, and 50% response distribution. There are 17665 residents living in Gongtan town. There are 267 questionnaires for the minimum sample size, and 376 questionnaires are the recommended sample size from Raosoft. Three experienced researchers introduced the purpose to the participants.

At the beginning of the survey, this study provided a consent form with the necessary information for participants to clarify several key points. This study informed the participants about the study’s purpose and the proposal of voluntary behavior. Therefore, the participants could withdraw at any time without consequence. Participants were informed about the study’s objectives and voluntary participation, allowing them to withdraw freely without consequences. We assured them their identities would remain confidential, ensuring their privacy throughout the research process.

Additionally, we provided information regarding the number of questions and the estimated time needed to complete the survey. We emphasized that all data would be kept private and utilized exclusively for academic purposes. Lastly, participants were informed that they could access the research outcomes once the study was concluded, along with other relevant information. This approach aimed to build participant trust and facilitate informed consent.

There are 455 residents take part in the survey. The questionnaire answer time was considerably shorter than anticipated, prompting the exclusion of responses from individuals who identified as non-residents of Gongtan town. Consequently, the study yielded 408 valid questionnaires, resulting in an 89.6% response rate.

3.2.3. Data Analysis

Table 1 indicates a higher proportion of males in the sample, likely due to the prevalence of manual workers and small business entrepreneurs along the Wujiang River. The age distribution was primarily skewed toward older adults, especially those aged 51-60, while most respondents had a secondary school education. Additionally, the annual income of the respondents predominantly ranged around 80,000 yuan (approximately 11,320 US dollars), reflecting the living standards of older residents and students in the town. SEM has become an increasingly recognized methodology for data analysis in empirical research within the social sciences (Chatterjee and Kar 2020). Accordingly, this research employs it to test the proposed model empirically.

It is an empirical method for QCA, grounded in Boolean algebra and fuzzy set theory (Ragin 2009). The conditions and outcomes relations could be examined from a configurational perspective instead of a purely correlational (Senyo, Osabutey et al. 2021). QCA uses empirical data to analyze causal relationships related to specific questions, particularly in the context of small sample studies. It elucidates the essential factors contributing to events and explores the complex causal relationships between them (Ragin 2009). The crisp set QCA, fuzzy set QCA, and multi-value QCA are popular QCA (Ragin 2009).

4. Results

The measures were validated through Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA). Subsequently, this research utilized SEM to analyze the data and estimate the measurement and structural models. In addition, the fsQCA analyses the same data to identify the configurations of antecedent conditions leading to the specified outcomes (Ragin 2009, Hair, Risher et al. 2019).

4.1. CFA Results

Hair proposed that the CFA measurement model showed an acceptable fit on seven constructs, and the goodness-of-fit measures were within the acceptable threshold range (Hair 2011). The chi-square (χ²) statistic was 1124.366, indicating the model fit well. The normed chi-square (χ²/df) ratio is 1.103, and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) score is 0.018, along with the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) and Root Mean Square Residual (RMR) values of 0.016 and 0.05, respectively, further support this conclusion, showing a good model fit. Additionally, the Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) and Adjusted Goodness of Fit Index (AGFI) scores were 0.91 and 0.905, respectively, while the Normed Fit Index (NFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and Comparative Fit Index (CFI) scores were 0.901, 0.989, and 0.99, all indicating the model fit is adequate (Byrne 2001).

4.2. PLS-SEM Analysis Results

4.2.1. Measurement Model

The standardized Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.888, over the 0.8 threshold and indicating high constructs‘ reliability. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure yielded a 0.767 value, within 0.7 and 0.8, signifying suitable data for factor analysis (see

Appendix A). As presented in

Table 2, the standardized factor loading (SFL) for all items exceeded 0.68, which is above the acceptable level of 0.6, confirming the adequacy of indicator reliability (Hair, Risher et al. 2019).

Fornell and Larcker proposed that internal consistency reliability was assessed with both Cronbach’s alpha (CA) and composite reliability (CR) (Fornell and Larcker 1981, Hair, Risher et al. 2019).

Table 2 demonstrates that all indicators exceeded the threshold of 0.7, showing satisfactory measurement reliability. The study employed the average Variance extracted (AVE) to evaluate convergent validity, which exceeded 0.5, confirming good internal consistency (Hair, Risher et al. 2019).

Discriminant validity was assessed using the Fornell-Larcker criterion (Fornell and Larcker 1981). The square root of the AVE is more significant than the correlations among variables, affirming the discriminant validity of the measurement model in

Table 3 (Hair, Risher et al. 2019).

4.2.2. Common Method Bias

This study employed Podsakoff’s research about Harman’s one-factor test to assess the potential for Common Method Bias (CMB) in the current study. The findings in

Table 4 reveal that the first factor explains 19.464% of the Variance. This value falls below the critical threshold of 40%, indicating that CMB is unlikely to significantly compromise our results’ validity.

4.2.3. Structural Model

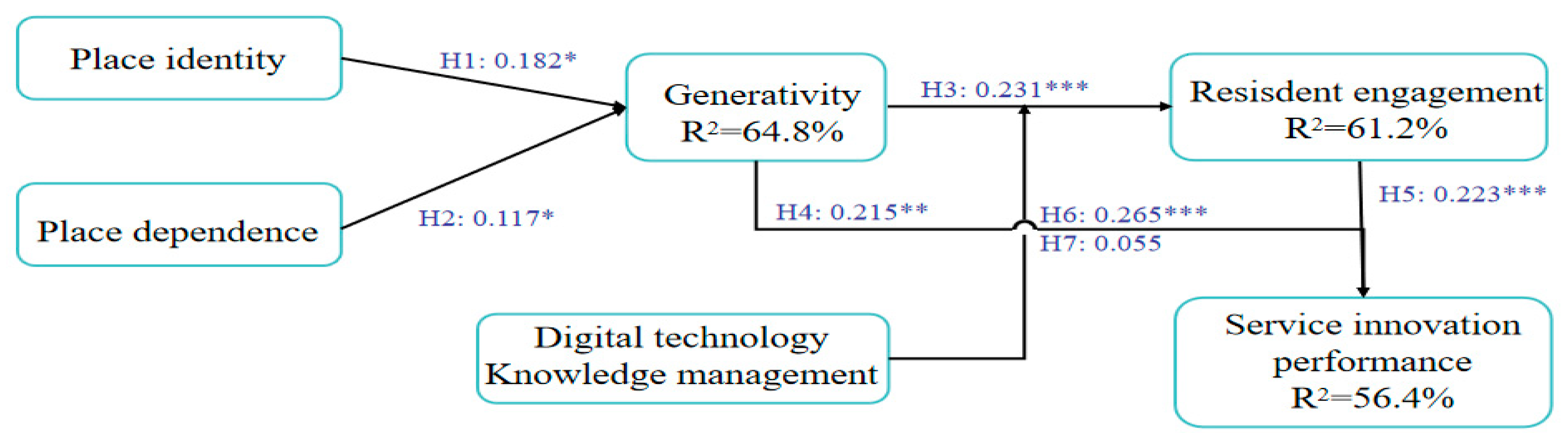

The findings from the SEM analysis demonstrate a robust fit for the proposed model, as indicated by various fit indices: χ²/df = 1.774, GFI = 0.906, CFI = 0.989, NFI = 0.900, RMSEA = 0.009, SRMR = 0.052. Together, these indices indicate that the model adequately represents the data. The final structural model is depicted in

Figure 2. The analysis reveals that both place identity (β = 0.182, ρ < 0.05) and place dependence (β = 0.117, ρ < 0.05) significantly influence generativity, thereby providing support for Hypotheses 1 (H1) and 2 (H2). In contrast, while generativity (β = 0.231, ρ < 0.001) and digital technology (β = 0.265, ρ < 0.001) showed relationships with resident engagement, the relationship between knowledge management (β = 0.055, ρ > 0.05) and resident engagement did not reach statistical significance. This lack of significance may be attributable to the absence of an effective knowledge management system in Gongtan Town. Additionally, residents communicate information to tourists based on personal experiences and memory rather than structured knowledge transfer. Consequently, Hypotheses 3 (H3) and 6 (H6) are supported, while Hypothesis 7 (H7) is not.

Furthermore, regarding the direct impact of individual psychological factors and behavioral characteristics on service innovation performance, the results presented in

Figure 2 indicate that both generativity (β = 0.215, ρ < 0.01) and resident engagement (β = 0.223, ρ < 0.001) significantly contribute to the outcome variable. Thus, Hypotheses 4 (H4) and 5 (H5) are substantiated.

4.3. fsQCA Analysis Results

This research utilizes fsQCA to explore the causal processes that yield specific outcomes and to address causal complexity. The analysis follows six key steps. First is model construction. Establishing the theoretical framework and identifying relevant causal factors. The second is sampling. Selecting diverse cases to provide a robust analysis. The third is data calibration. Converting raw data into fuzzy sets to accurately represent variable membership scores. Next is necessary condition analysis. Identifying conditions that must exist for the outcome to occur. Fifth is sufficient condition analysis. Check for combinations of sufficient causal conditions to produce the desired outcome. Last is result interpretation. Analyzing and contextualizing the results to draw meaningful conclusions about the relationships among causal factors. The study aims to reveal the intricate configurations contributing to successful outcomes by following steps.

4.3.1. Calibration

This study employs fsQCA 4.0 software to calibrate the data. The dataset used is the same as the former SEM analysis data and is transformed into fuzzy sets. In this calibration process, 0 indicates full non-membership in the set, while 1 signifies full membership. The analysis reveals multiple combinations yielding equivalent results, as

Table 4 outlines.

4.3.2. Necessary Conditions Analysis

The necessary conditions analysis checks the factors essential for producing a specific outcome. According to previous studies, a consistency value exceeding 0.9 indicates that a condition is necessary for the corresponding outcome variable (Ragin 2009). As shown in

Table 5, there are no factors that satisfy this criterion for high quality of service innovation performance (“SIP”) or for low quality of service innovation performance (“~SIP”).

4.3.3. Result Interpretation

This study employs a truth table to systematically show the various conditions and combinations that may cause the desired outcome, specifically, the high quality of SIP. Constructing this truth table is a prerequisite for prioritizing core factors and identifying the most plausible combinations implicated in SIP. In this analysis, the frequency threshold for consistency is conventionally set at 0.8. Rows that do not meet this threshold are coded as one and subsequently eliminated from further consideration. For the raw consistency, a threshold of 0.8 is established, while the PRI consistency is set at 0.7.

4.3.4. Sufficient Conditions Analysis for SIP

The standard analysis conducted using fsQCA software yields complex, intermediate, and simple solutions that elucidate the combinations of conditions leading to the high quality of SIP and the negative result, as summarized in

Table 6. It is important to emphasize that no individual condition is sufficient to achieve ’SIP’. Furthermore, the consistency scores for all three identified pathways exceed the threshold of 0.8, indicating that each variable contributes sufficiently to the outcome.

4.3.5. High Quality of SIP Results

As illustrated in

Table 6, place attachment, digital technology, and knowledge management emerge as core conditions across different configurations. This finding underscores residents’ motivation to drive wellness tourism service innovation. Notably, digital technology and knowledge management are essential conditions for enhancing SIP.

Solution a demonstrates that combining place attachment and knowledge management as core conditions, along with the absence of generativity and resident engagement as peripheral conditions, leads to a high quality of SIP. Solution b suggests that place attachment, digital technology, knowledge management, and generativity can collaboratively yield favorable outcomes for SIP. Solution c indicates that prioritizing digital technology as the core condition, with resident engagement as a peripheral condition and excluding other factors, is sufficient to achieve a significant level of adoption in service innovation practices.

The fsQCA results reveal that the presence or absence of a single factor is not necessary for achieving high-quality SIP. In the three configuration paths analyzed, no individual element is consistently present or absent across all cases. Furthermore, knowledge management emerges as a core condition in solutions a and b. In contrast, the SEM analysis indicates that the impact of knowledge management on SIP is significantly mediated by resident engagement. This pattern is also observed with the digital technology variable. These findings highlight that fsQCA provides a complementary perspective to the net effect approach commonly utilized in SEM, emphasizing the complex interplay of conditions that influence service innovation performance.

4.3.6. Low Quality of SIP Results

In contrast to traditional SEM and regression model methods, fsQCA is particularly adept at addressing causal asymmetry (Ragin 2009). This study applied the same threshold settings to investigate the conditions combined to negate the outcome (~SIP) in

Table 6. It indicates that two configurations are sufficient and empirically relevant in explaining it. It is supported by the consistency and coverage of each configuration, which exceeds 0.8. Moreover, these configurations collectively account for 79% of the sample, demonstrating a significant association with low quality of SIP.

Upon examining

Table 6, it becomes clear that two configurations contribute to negating low-quality SIP. In the first configuration (solution

d), place attachment and resident engagement are absent as core conditions. Meanwhile, the second configuration (solution

e) highlights the absence of resident engagement, digital technology, and knowledge management as core conditions. These findings illustrate an asymmetrical relationship with low-quality SIP, whereby the absence of these critical factors uniquely contributes to diminished performance. This series of results further underscores the phenomenon of causal asymmetry, indicating that the lack of certain conditions, rather than the presence of neutral factors, plays a significant role in adversely affecting SIP.

5. Discussion

5.1. Findings

5.1.1. The Antecedents of Resident Engagement

This study investigates the antecedents of resident engagement, emphasizing its role in fostering SIP within wellness tourism destinations. While prior research predominantly highlights the positive outcomes of resident engagement, understanding the root causes is essential for strategic planning and implementation. Resident engagement behavior links to positive emotional states, which catalyze active participation in activities that promote environmental protection, cultural heritage enhancement, service innovation, and economic development in tourism. This study builds upon existing literature by establishing the outcomes and precursors of effective resident engagement.

The findings from the SEM analysis illuminate the significant influences of four key factors on resident engagement: place attachment, generativity, digital technology, and knowledge management. Residents‘ emotional bonds to their locality significantly foster engagement, as a strong sense of identity and belonging prompts proactive contributions to community initiatives. Moreover, generativity reflects residents’ motivations to contribute positively to their communities and promote long-term sustainability, reinforcing their engagement efforts. Furthermore, the increasing prevalence of digital tools facilitates communication and knowledge sharing, creating interactive platforms for engagement and community involvement. Effective knowledge management systems enhance the flow of information, fostering collective learning and empowering residents to engage meaningfully in community development (Zhang, Zhang et al. 2014, Li, Myagmarsuren et al. 2023). This study employs fsQCA to reveal differing configurations of factors that lead to various quality outcomes in SIP. This nuanced approach underscores the complexity of resident engagement dynamics and invites further exploration into how these configurations can be optimized in diverse contexts.

5.1.2. The Antecedents of Service Innovation Performance

This study integrates insights from SEM and fsQCA to identify key factors influencing SIP in wellness tourism destinations. The findings highlight that resident engagement is a significant determinant of the high quality of SIP. Conversely, the absence of resident engagement is a fundamental condition linked to low-quality SIP outcomes. It emphasizes the essential role of fostering resident engagement, aligning with prior research(Sharpe, Perlaviciute et al. 2021). Therefore, it is vital that the design of service innovations specifically targets factors that enhance resident engagement, namely place attachment and generativity. Service innovation should prioritize fostering a sense of ownership among residents, reinforcing their sense of belonging and pride in the regional identity (Luo and Ren 2020).

Additionally, incorporating a community-oriented approach into service innovations is crucial. Such approaches facilitate communication and interaction among residents and future generations, leading to a generative-based community social network (Bird, McGillion et al. 2021). In this context, cultivating a distinctive and unique sense of place identity and place dependence is essential for instilling a sense of responsibility among residents. Furthermore, digital technology is critical to information exchange within this generative community network.

Interestingly, while SEM analysis did not find a direct effect of knowledge management on SIP, diverging from previous studies (Hopkins, Tidd et al. 2011), the fsQCA results reveal a more nuanced relationship. Although these factors may not act as primary determinants in isolation, they become critical when combined with other variables. It suggests integrating digital technology and effective knowledge management under specific conditions, such as place attachment and generativity, can significantly enhance resident engagement (Cennamo, Dagnino et al. 2020). The fsQCA analysis also indicates that the absence of digital technology and knowledge management constitutes a core condition for low-quality SIP. This observation raises considerations regarding the influence of individual behaviors on SIP. Residents may be less inclined to engage in service innovation initiatives without access to valuable, engaging information, mainly through digital platforms and social media. Therefore, it is essential to prioritize the development of media and platforms that facilitate effective information transmission. Service innovation designs should focus on precise delivery and communication strategies, particularly regarding inter-generational knowledge flow and engagement, to ensure that residents are well-informed and motivated to participate.

In summary, the SEM analysis results indicate that place attachment, generativity, and digital technology significantly influence resident engagement, ultimately enhancing the quality of SIP. This analysis also identifies predictive factors for SIP within wellness tourism destinations, including place attachment, generativity, digital technology, knowledge management, and resident engagement. Moreover, the findings from the fsQCA complement the SEM results by providing deeper insights into the complex causal relationships at play. The fsQCA identifies three configurations associated with high SIP and two configurations associated with low SIP, which are not captured by the SEM approach. It illustrates the value of considering combinations of conditions to understand SIP’s intricacies better.

A comparative analysis with existing literature reveals that some findings align with established research, underscoring that scholars widely recognize certain factors as critical. However, notable discrepancies arise regarding the impact of digital technology and knowledge management on SIP. These differences may stem from the specific context of this study and a more comprehensive analytical method. Furthermore, the impact of specific factors evolved alongside community social network development. Thus, this research aims to provide new insights into SIP while advocating for establishing a generative-based community model, emphasizing the significance of resident engagement in fostering service innovation.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

This research contributes significantly to the literature on service innovation within generative-based community wellness tourism destinations. Firstly, it addresses a notable gap in the existing literature, which has not systematically explored service innovation performance through the lens of resident engagement. By linking sustainable development to the concept of generative communities, this study enhances the understanding of the factors influencing service innovation. The findings confirm the substantial roles of place attachment and generativity in shaping residents‘ sense of responsibility, thereby influencing SIP outcomes within the wellness tourism context. It enriches the theoretical discourse surrounding resident engagement and SIP.

Secondly, this study adopts a holistic and integrative framework for examining resident engagement in SIP, contributing to the broader literature on SIP. A singular perspective is often insufficient to capture the complexity of these relationships. Therefore, this study employs multiple theoretical lenses to comprehensively understand SIP in this context. While previous research has primarily addressed SIP from the viewpoints of customers or employees, this study distinguishes itself by focusing on resident engagement characteristics and integrating generativity theory to analyze the impact of place attachment. Additionally, by exploring the antecedents of SIP and incorporating service innovation theory, this research overcomes the limitations of using a single model, thereby deepening the understanding of generative-based community service innovation.

Lastly, from a methodological standpoint, this study highlights the complementary strengths of SEM and fsQCA in investigating SIP. Many prior studies have relied on various methodologies, including multiple regression models, SEM, and PLS, to examine the net causal effects of individual antecedents on dependent variables. However, these approaches often lack a comprehensive understanding of the complex relationships involved. By employing fsQCA alongside SEM, this study reveals diverse configurations that illustrate causal conditions’ complex, non-linear, and asymmetric effects on SIP outcomes. This methodological innovation adds depth to the existing SIP research, facilitating a more nuanced exploration of the underlying mechanisms at play.

5.3. Managerial Implications

This research offers valuable management insights to enhance service innovation performance within generative-based communities. Firstly, the findings illustrate that the community environment influences residents’ motivation. When residents feel a sense of ownership and attachment to their community, they are more likely to actively identify their roles, take pride in their contributions, and become more responsible. It fosters a strong focus on activities related to service innovation, significantly boosting resident engagement in wellness tourism destination’s sustainable development. To leverage this, wellness tourism vendors should prioritize experiential aspects of service innovation. Collaborative initiatives with the community to enhance residents‘ sense of place identity and dependence are vital, as is promoting awareness of service innovation through inter-generational outreach.

Secondly, the study underscores that resident engagement is closely linked to their acceptance of service innovation information from external sources. While residents may not actively engage in service innovation simply for information acquisition, lacking adequate information flow can lead to rejecting innovation efforts. Utilizing community-focused social media platforms can facilitate the timely dissemination of service-related information, fostering trust and interest in innovation among residents. Enhancing the efficiency of social media use and stabilizing the community’s knowledge management system is critical. Consequently, managers should develop comprehensive strategies for community information flow through technology and management systems. It will enhance resident engagement and build a more informed community poised to support service innovations.

5.4. Limitations and Future Directions

This research predominantly focused on residents as the primary actors in SIP, whereas existing literature has highlighted the importance of multi-actor engagement, including customers and employees. Future studies could seek to integrate these multi-actor dynamics to explore a more comprehensive set of influencing factors on SIP, thereby addressing the limitations of the current research.

Secondly, this study is geographically restricted to Gongtan town and does not account for resident engagement in SIP across other cities or countries. Variations in cultural, social, and economic contexts may lead to different engagement patterns and outcomes. Therefore, future research should aim to conduct surveys across multiple cities and countries to facilitate a broader and more universal understanding of resident engagement in SIP, expanding the applicability of the findings to diverse settings.

6. Conclusions

This study highlights the transformative role of service innovation in advancing sustainable development. Residents’ engagement in service innovation is vital for enhancing their quality of life and safeguarding cultural heritage for future generations. Despite the growing importance of this topic, research on resident engagement in service innovation is still in its early stages, necessitating additional exploration. This research seeks to provide a nuanced understanding of resident engagement in service innovation performance (SIP) within generative-based communities by utilizing generativity theory and service innovation theory as foundational frameworks. Through applying SEM and fsQCA, we examine both the direct effects and combined influences on SIP. These findings contribute to the theoretical discourse on resident engagement in service innovation and present practical implications for stakeholders in wellness tourism. By emphasizing the factors that enhance SIP, this research offers actionable insights for practitioners aiming to foster resident engagement and promote sustainable tourism development. In summary, this study advances the understanding of how community engagement in service innovation can drive sustainable development in wellness tourism, highlighting the need for continued research to explore this dynamic interplay further.

Author Contributions

All authors meet the journal’s authorship guidelines. LW performed the analysis and prepared the original manuscript. YHQ, and XBP supervised and validated the study. LW, YHQ, and XBP contributed to interpreting the results and the original draft’s review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by 2024 National Social Science Fund Major Project “Theoretical Construction and Practical Path of Modernization of China’s Rural Governance System and Governance Capacity” (Approval No.: 24&ZD107).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We are also indebted to Professor Dingxiang Liu for his guidance and to the participants who answered the questionnaire.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Appendix A

| Items |

Detail |

Author |

| PAI1 |

I identify strongly with my community. |

Williams, D.R.; Vaske, J.J. (2003) |

| PAI2 |

I feel that my community is a part of me. |

| PAI3 |

I am very attached to my community. |

| PAI4 |

My community means a lot to me. |

| PAD1 |

My community is the best place to do what I like to do. |

| PAD2 |

No other place can compare to my community. |

| PAD3 |

I gain more satisfaction from my community than from any other. |

| CNN1 |

I like to visit tourist attractions of the city. |

Wang et al.,2014 |

| CNN2 |

I am glad to see new tourism development in the city. |

| CNN3 |

I like to help promote my city’s tourism if needed. |

| ATT1 |

I like to make tourists feel welcome when visiting our city. |

| ATT2 |

I am happy to help tourists visiting my community. |

| ATT3 |

I would feel guilty if I did not interact with tourists visiting my community. |

| SIF1 |

New service development boosts the profitability of wellness program. |

Storey & Kelly (2002)

Hsueh et al. (2010)

Yang &Tian (2015)

Li et al. (2017) |

| SIF2 |

New service development boosts return on investment for wellness businesses. |

| SIF3 |

New service development improves customer usage and sales. |

| SIC1 |

I am very satisfied with the innovative service activities (**) provided by the wellness community. |

Storey & Kelly

(2002)

Hsueh et al. (2010)

Yang &Tian (2015)

Li & Xu (2015) |

| SIC2 |

I am willing to continue to stay in the wellness community and participate in the company’s innovative service activities (**). |

| SIC3 |

I would like to recommend this wellness community to others. |

| SIC4 |

I would like to spend more time in the wellness communities and consume again. |

| SII1 |

The service innovation carried out by the wellness community (**) has improved our customer participation activity. |

Storey & Kelly (2002)

Tang (2017)

Hsueh et al. (2010)

Yang &Tian (2015)

Li et al. (2017) |

| SII2 |

Service innovations in wellness communities (**) has strengthened internal collaboration between customers and front-liners (communication efficiency, Problem feedback, efficiency improvement, etc.) |

| SII3 |

The service innovations carried out by the wellness community (**) has improved the quality of new products/services. |

| GEN1 |

I try to pass along the knowledge I have gained through my experiences. |

Wells et al., 2016;

Urien & Kilbourne, 2011 |

| GEN2 |

I do not feel that other people need me. |

| GEN3 |

I feel as though I have made a difference to many people. |

| GEN4 |

I have made and created things that have had an impact on other people. |

| GEN5 |

I try to be creative in most things that I do. |

| GEN6 |

I think that I will be remembered for a long time after I die. |

| GEN7 |

Others would say that I have made unique contributions to society. |

| GEN8 |

I have important skills that I try to teach others. |

| GEN9 |

In general, my actions do not have a positive effect on other people. |

| GEN10 |

I feel as though I have done nothing of worth to contribute to others. |

| GEN11 |

I have made many commitments to many different kinds of people, groups, and activities in my life. |

| GEN12 |

Other people say that I am a very productive person. |

| GEN13 |

I have a responsibility to improve the neighborhood in which I live. |

| GEN14 |

People come to me for advice. |

| DT1 |

The community has a full range of social media |

Leonard-Barton & Deschamps (1988)

Jayachandran et al. (2005)

Trainor et al. (2014)

Chuang (2020) |

| DT2 |

The community’s social media technology is fully functional |

| DT3 |

The community’s social media technology is maintained by specialized technicians |

| DT4 |

I used social media every day |

| KM1 |

Experts guide the service, provide continuous tracking services by dedicated personnel, and train users. |

Cui, A. S., & Wu, F. (2016). |

| KM2 |

Enterprises establish customer service desks and cross-departmental teams to provide customer services, analyze customer needs, monitor customer satisfaction and loyalty, and organize internal meetings to share customer knowledge. |

| KM3 |

Collect customer service needs through emails, visits, surveys, and telephone calls, understand user knowledge background when solving user problems, adopt user suggestions, and hire experts to solve company problems. |

| KM4 |

Statistical analysis of customer needs through modern social media, establishment of platforms such as knowledge learning communities to increase knowledge sharing between employees and customers, and rewards for customers who promote service innovation. |

References

- Adams R, Jeanrenaud S, Bessant J, Denyer D, Overy P (2016). Sustainability-oriented innovation: A systematic review. International Journal of Management Reviews18(2): 180-205. [CrossRef]

- Altman I, Low SM (1992). Place Attachment Plenum Press. New York-London 262.

- Andreu MG, Font-Barnet A, Roca ME (2021). Wellness tourism—new challenges and opportunities for tourism in Salou. Sustainability 13(15): 8246. [CrossRef]

- Anthony Jr B (2024). The role of community engagement in urban innovation towards the co-creation of smart sustainable cities. Journal of the Knowledge Economy 15(1): 1592-1624. [CrossRef]

- Bec A, McLennan CL, Moyle BD (2016). Community resilience to long-term tourism decline and rejuvenation: A literature review and conceptual model. Current Issues in Tourism 19(5): 431-457. [CrossRef]

- Bird M, McGillion M, Chambers EM, Dix J, Fajardo CJ, Gilmour M, Levesque K, Lim A, Mierdel S, Ouellette C, Polanski AN (2021). A generative co-design framework for healthcare innovation: development and application of an end-user engagement framework. Research Involvement and Engagement 7: 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Bonaiuto M, Alves S, De Dominicis S, Petruccelli I (2016). Place attachment and natural hazard risk: Research review and agenda. Journal of Environmental Psychology 48: 33-53. [CrossRef]

- Brown SH (2014). Place-attachment in heritage theory and practice: a personal and ethnographic study (Doctoral dissertation). http://hdl.handle.net/2123/15976.

- Butt S, Smith SM, Moola F, Conway TM (2021). The relationship between knowledge and community engagement in local urban forest governance: A case study examining the role of resident association members in Mississauga, Canada. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 60: 127054. [CrossRef]

- Byrne BM (2001). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts. Applications, and programming 20(01).

- Cennamo C, Dagnino GB, Di Minin A, Lanzolla G (2020). Managing digital transformation: Scope of transformation and modalities of value co-generation and delivery. California Management Review 62(4): 5-16. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee S, Kar AK (2020). Why do small and medium enterprises use social media marketing and what is the impact: Empirical insights from India. International Journal of Information Management 53: 102103. [CrossRef]

- Chen X, Tang J, Liu P (2024). How place attachment affects pro-environmental behaviors: The role of empathy with nature and nature relatedness. Current Psychology 1-3. [CrossRef]

- Chikerema L, Makanyeza C (2021). Enhancing the performance of micro-enterprises through market orientation: Evidence from Harare, Zimbabwe. Global Business and Organizational Excellence 40(3): 6-19. [CrossRef]

- Chopra M, Saini N, Kumar S, Varma A, Mangla SK, Lim WM (2021). Past, present, and future of knowledge management for business sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2021 Dec 15;328:129592. [CrossRef]

- Cross JE, Keske CM, Lacy MG, Hoag DL, Bastian CT (2011). Adoption of conservation easements among agricultural landowners in Colorado and Wyoming: The role of economic dependence and sense of place. Landscape and Urban Planning 101(1): 75-83. [CrossRef]

- Erul E, Uslu A, Cinar K, Woosnam KM (2023). Using a value-attitude-behaviour model to test residents’ pro-tourism behaviour and involvement in tourism amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Current Issues in Tourism 26(19): 3111-3124. [CrossRef]

- Escalona S (1951). Childhood and Society. Erik H. Erikson. New York: Norton, 1950. 397 pp. $4.00. Science113(2931): 253-253.

- Esfandiari H, Choobchian S (2020). Designing a wellness-based tourism model for sustainable rural development. [CrossRef]

- Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of marketing research 18(1): 39-50. [CrossRef]

- Friedman A (2023). A Need for Sustainable Urban Environments. In the Sustainable Digital City, Springer: 17-37. Cham: Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Gergen KJ (2009). Relational being: Beyond self and community. Oxford university press.

- Goldenberg J, Han S, Lehmann DR, Hong JW (2009). The role of hubs in the adoption process. Journal of marketing 73(2): 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Gu H, Ryan C (2008). Place attachment, identity and community impacts of tourism—the case of a Beijing hutong. Tourism management 29(4): 637-647. [CrossRef]

- Guo Y, Zhang J, Zhang Y, Zheng C (2018). Catalyst or barrier? The influence of place attachment on perceived community resilience in tourism destinations. Sustainability 10(7): 2347. [CrossRef]

- Gustafsson A, Snyder H, Witell L (2020). Service innovation: a new conceptualization and path forward, Sage Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA. 23: 111-115.

- GWI (2023). Global Wellness Economy Monitor 2023.

- Hair JF (2011). Multivariate data analysis: An overview. International encyclopedia of statistical science: 904-907. [CrossRef]

- Hair JF, Risher JJ, Sarstedt M, Ringle CM (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European business review 31(1): 2-24. [CrossRef]

- Hall, C. M. (2008). Tourism planning: Policies, processes and relationships, Pearson education.

- Hallak R, Brown G, Lindsay NJ (2013). Examining tourism SME owners’ place attachment, support for community and business performance: The role of the enlightened self-interest model. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 21(5): 658-678. [CrossRef]

- Han S, Olya H, Kim MJ, Kim T (2024). Generative-based community sustainable tourism development: From conceptualization to practical framework. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 61: 34-44. [CrossRef]

- Helfat CE, Peteraf MA (2003). The dynamic resource-based view: Capability lifecycles. Strategic management journal 24(10): 997-1010. [CrossRef]

- Heymann M (2019). The changing value equation: Keeping customers satisfied while meeting bottom-line objectives in the service industry. Global business and organizational excellence 38(6): 24-30. [CrossRef]

- Hofer J, Bond MH (2008). Do implicit motives add to our understanding of psychological and behavioral outcomes within and across cultures. Handbook of motivation and cognition across cultures: 95-118.

- Hofer J, Busch H (2024). Culture and Generativity. The Development of Generativity across Adulthood: 321.

- Hopkins MM, Tidd J, Nightingale P, Miller R (2011). Generative and degenerative interactions: positive and negative dynamics of open, user-centric innovation in technology and engineering consultancies. R&d Management 41(1): 44-60. [CrossRef]

- Hsueh JT, Lin NP, Li HC (2013). The effects of network embeddedness on service innovation performance. InAdvances in Service Network Analysis 2013 Sep 13 (pp. 143-156). Routledge.

- Johnston KA, Taylor M, Ryan B (2024). Evaluation of community engagement for resilience outcomes: A pre-engagement approach. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 110: 104613. [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen BS, Stedman RC (2001). Sense of place as an attitude: Lakeshore owners attitudes toward their properties. Journal of environmental psychology 21(3): 233-248. [CrossRef]

- Kabus J, Dziadkiewicz M (2022). Residents‘ Attitudes and Social Innovation Management in the Example of a Municipal Property Manager. Energies 15(16): 5812. [CrossRef]

- Kim MJ, Hall CM, Bonn M (2021). Can the value-attitude-behavior model and personality predict international tourists’ biosecurity practice during the pandemic?. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 48: 99-109. [CrossRef]

- Kotre JN (1984). Outliving the self: Generativity and the interpretation of lives. (No Title).

- Lee TH (2013). Influence analysis of community resident support for sustainable tourism development. Tourism management 34: 37-46. [CrossRef]

- Lewicka M (2011). Place attachment: How far have we come in the last 40 years?. Journal of environmental psychology 31(3): 207-230. [CrossRef]

- Li W, Myagmarsuren D, Yadmaa Z (2023). Digital Technology, Superior Support, and Employee Participation in Service Innovation Performance of Wellness Industry—Based on fsQCA Method. J. Manag. Innov 1: 1-8.

- Li W, Myagmarsuren D, Yuan Hao Q, Yadmaa Z, Togtokhbuyan L (2023). Assessing the determinants of time banking adoption intentions in wellness tourism destinations: a unified theory of acceptance and use of technology (UTAUT). International Journal of Spa and Wellness 6(2): 201-220. [CrossRef]

- Li W, Myagmarsuren D, Yuanhao Q, Yadmaa Z, Shanshan L (2023). Customer Engagement in Service Innovation Performance of the Wellness Industry-Based on the fsQCA Method. Phys. Med. Rehabil. Int 10: 1212. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y, Wang Y, Dupre K, McIlwaine C (2022). The impacts of world cultural heritage site designation and heritage tourism on community livelihoods: A Chinese case study. Tourism Management Perspectives 43: 100994. [CrossRef]

- Luo JM, Ren L (2020). Qualitative analysis of residents’ generativity motivation and behaviour in heritage tourism. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 45: 124-130. [CrossRef]

- Lusch RF, Nambisan S (2015). Service innovation. MIS quarterly 39(1): 155-176. [CrossRef]

- McAdams DP, de St Aubin ED (1992). A theory of generativity and its assessment through self-report, behavioral acts, and narrative themes in autobiography. Journal of personality and social psychology 62(6): 1003. [CrossRef]

- Moayerian N, McGehee NG, Stephenson Jr MO (2022). Community cultural development: Exploring the connections between collective art making, capacity building and sustainable community-based tourism. Annals of Tourism Research 93: 103355. [CrossRef]

- MSTIA (2018). Oslo Manual 2018.

- Muniz EC, Dandolini GA, Biz AA, Ribeiro AC (2021). Customer knowledge management and smart tourism destinations: a framework for the smart management of the tourist experience–SMARTUR. Journal of knowledge management 25(5): 1336-1361. [CrossRef]

- NTA (2016). Demonstration destination of health and wellness tourism.ICS 03.200 A 12 LB. LB/T 051-2016. N. T. A. o. t. P. s. R. o. China.

- Page SJ, Hartwell H, Johns N, Fyall A, Ladkin A, Hemingway A (2017). Case study: Wellness, tourism and small business development in a UK coastal resort: Public engagement in practice. Tourism Management 60: 466-477. [CrossRef]

- Peixoto MR, Paula FD, da Silva JF (2023). Factors that influence service innovation: a systematic approach and a categorization proposal. European Journal of Innovation Management 26(5): 1189-1213. [CrossRef]

- Proshansky HM (1983). Place identity: Physical world socialisation of the self. J. Environmental Psychology 3: 57-83. [CrossRef]

- Ragin CC (2009). Redesigning social inquiry: Fuzzy sets and beyond. University of Chicago Press.

- Ramkissoon H, Smith LD, Weiler B (2013). Testing the dimensionality of place attachment and its relationships with place satisfaction and pro-environmental behaviours: A structural equation modelling approach. Tourism management 36: 552-566. [CrossRef]

- Relph E (1976). Place and placelessness. Pion Limited 156.

- Roodbari H, Olya H (2024). An integrative framework to evaluate impacts of complex tourism change initiatives. Tourism Management 100: 104829. [CrossRef]

- Schmitt U (2020). Designing decentralized knowledge management systems to effectuate individual and collective generative capacities. Kybernetes 49(1): 22-46. [CrossRef]

- Schultz JR (2019). Think tank—Breaking through to innovation. Global Business and Organizational Excellence 38(6): 6-11. [CrossRef]

- Senyo PK, Osabutey EL, Seny Kan KA (2021). Pathways to improving financial inclusion through mobile money: a fuzzy set qualitative comparative analysis. Information Technology & People 34(7): 1997-2017. [CrossRef]

- Sharpe EJ, Perlaviciute G, Steg L (2021). Pro-environmental behaviour and support for environmental policy as expressions of pro-environmental motivation. Journal of Environmental Psychology 76: 101650. [CrossRef]

- Slife BD, Richardson FC (2010). Review of Relational Being: Beyond Self and Community, by Kenneth Gergen: Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009. 418 pp. ISBN 978-0-19-530538-8. $36.00, hardcover, Taylor & Francis.

- Stevens RE, Loudon DL, Cole H, Wrenn B (2013). Concise encyclopedia of church and religious organization marketing, Routledge. [CrossRef]

- Stokols D (1981). People in places: A transactional view of settings. Cognition, Social Behavior, and the Environment/Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Storey C, Kelly D (2002). Innovation in services: the need for knowledge management. Australasian Marketing Journal 10(1): 59-70. [CrossRef]

- Tidd J, Hull F (2003). Service Innovation: Organizational responses to technological opportunities & market imperatives. Imperial College Press.

- Tran TP, Mai ES, Taylor EC (2021). Enhancing brand equity of branded mobile apps via motivations: A service-dominant logic perspective. Journal of Business Research 125: 239-251. [CrossRef]

- Urien B, Kilbourne W (2011). Generativity and self-enhancement values in eco-friendly behavioral intentions and environmentally responsible consumption behavior. Psychology & marketing 28(1): 69-90. [CrossRef]

- van Osch W (2012). Generative collectives, Universiteit van Amsterdam [Host].

- van Osch W, Avital M (2010). Generative Collectives, Proceedings of the 2010 International Conference on Information Systems 175.

- Viglia G, Pera R, Bigné E (2018). The determinants of stakeholder engagement in digital platforms. Journal of Business Research 89: 404-410. [CrossRef]

- Villar F, Serrat R, Pratt MW (2024). Theory and Methods in Recent Research on Generativity across Adulthood. The Development of Generativity across Adulthood 1.

- Wang G, Yao Y, Ren L, Zhang S, Zhu M (2023). Examining the role of generativity on tourists’ environmentally responsible behavior: an inter-generational comparison. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 57: 303-314. [CrossRef]

- Wang L, Damdinsuren M, Qin YH, Gonchigsumlaa G, Zandan Y, Zhang ZL (2024). Forest Wellness Tourism Development Strategies Using SWOT, QSPM, and AHP: A Case Study of Chongqing Tea Mountain and Bamboo Forest in China. Sustainability 16(9): 3609. [CrossRef]

- Wang S, Wang J, Li J, Yang F (2020). Do motivations contribute to local residents’ engagement in pro-environmental behaviors? Resident-destination relationship and pro-environmental climate perspective. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 28(6): 834-852. [CrossRef]

- Wells VK, Taheri B, Gregory-Smith D, Manika D (2016). The role of generativity and attitudes on employees home and workplace water and energy saving behaviours. Tourism Management 56: 63-74. [CrossRef]

- Wernerfelt B (1984). A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic management journal 5(2): 171-180. [CrossRef]

- Wiltshier P (2020). Health and welfare at the boundaries: community development through tourism. Journal of Tourism Futures 6(2): 153-164. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Y, Zhang HL, Zhang J, Cheng S (2014). Predicting residents’ pro-environmental behaviors at tourist sites: The role of awareness of disaster’s consequences, values, and place attachment. Journal of Environmental Psychology 40: 131-146. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).