Submitted:

17 January 2025

Posted:

17 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

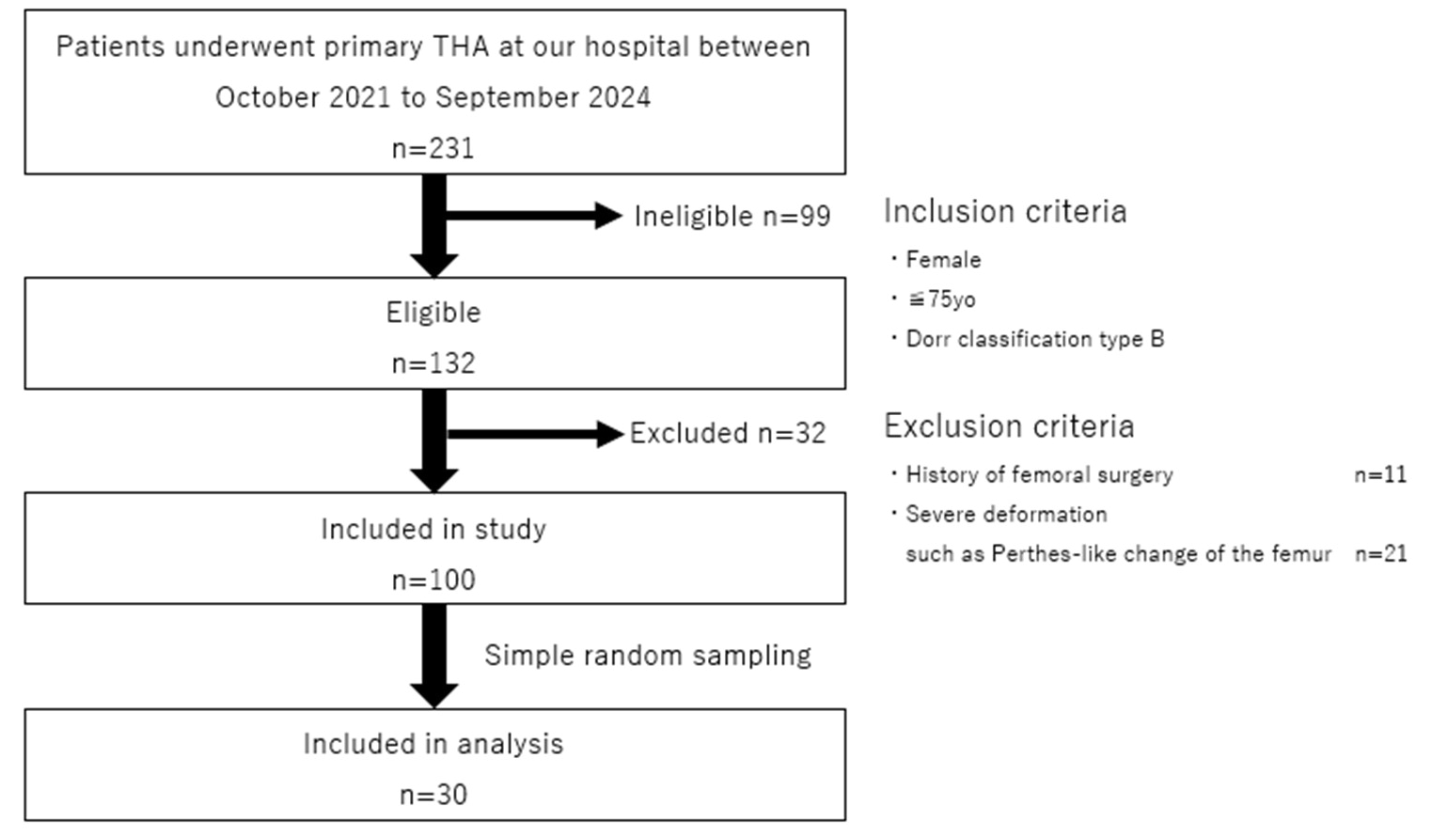

2.1. Study Setting and Design

2.2. Study Samples

2.3. Finite Element Analysis

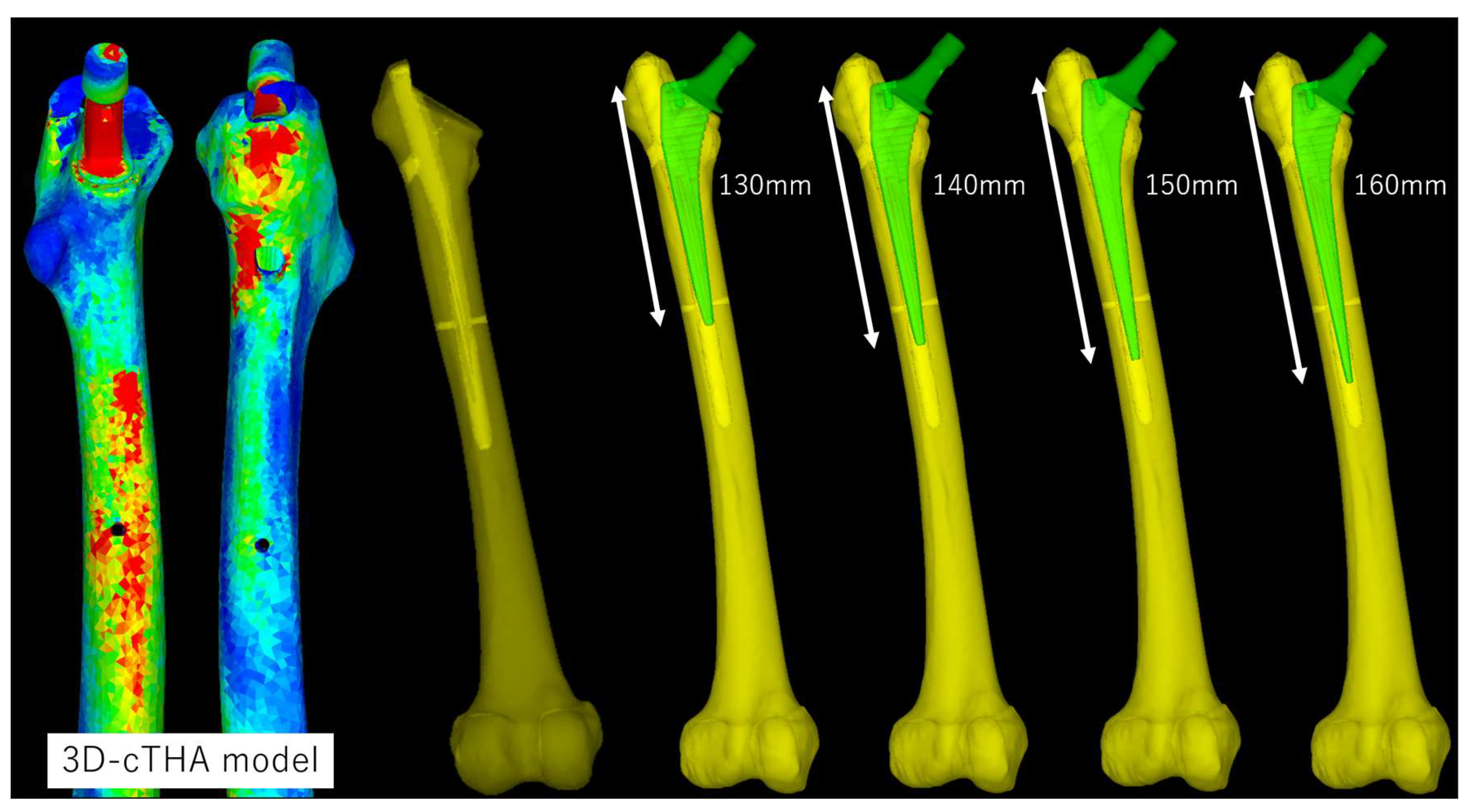

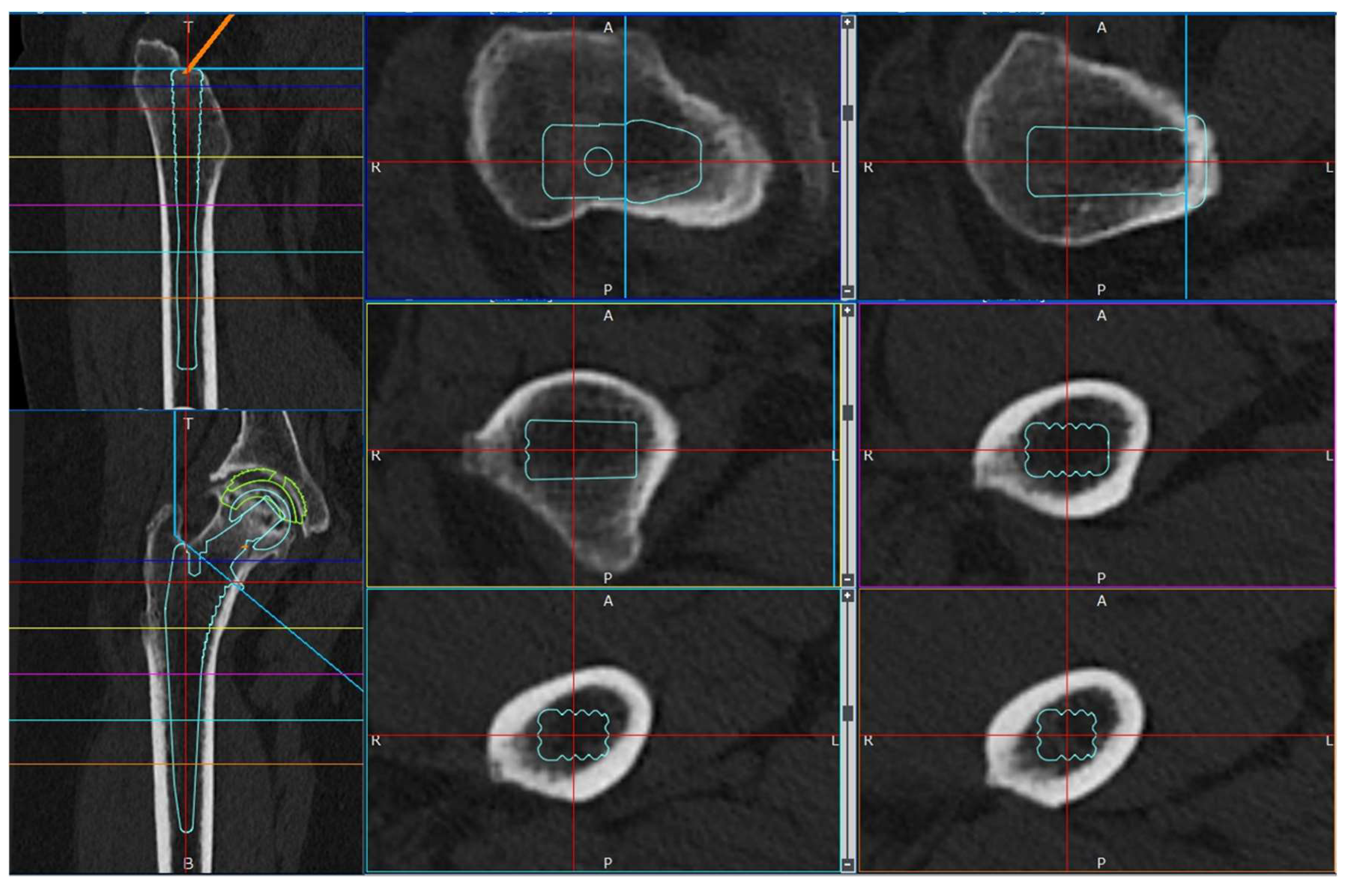

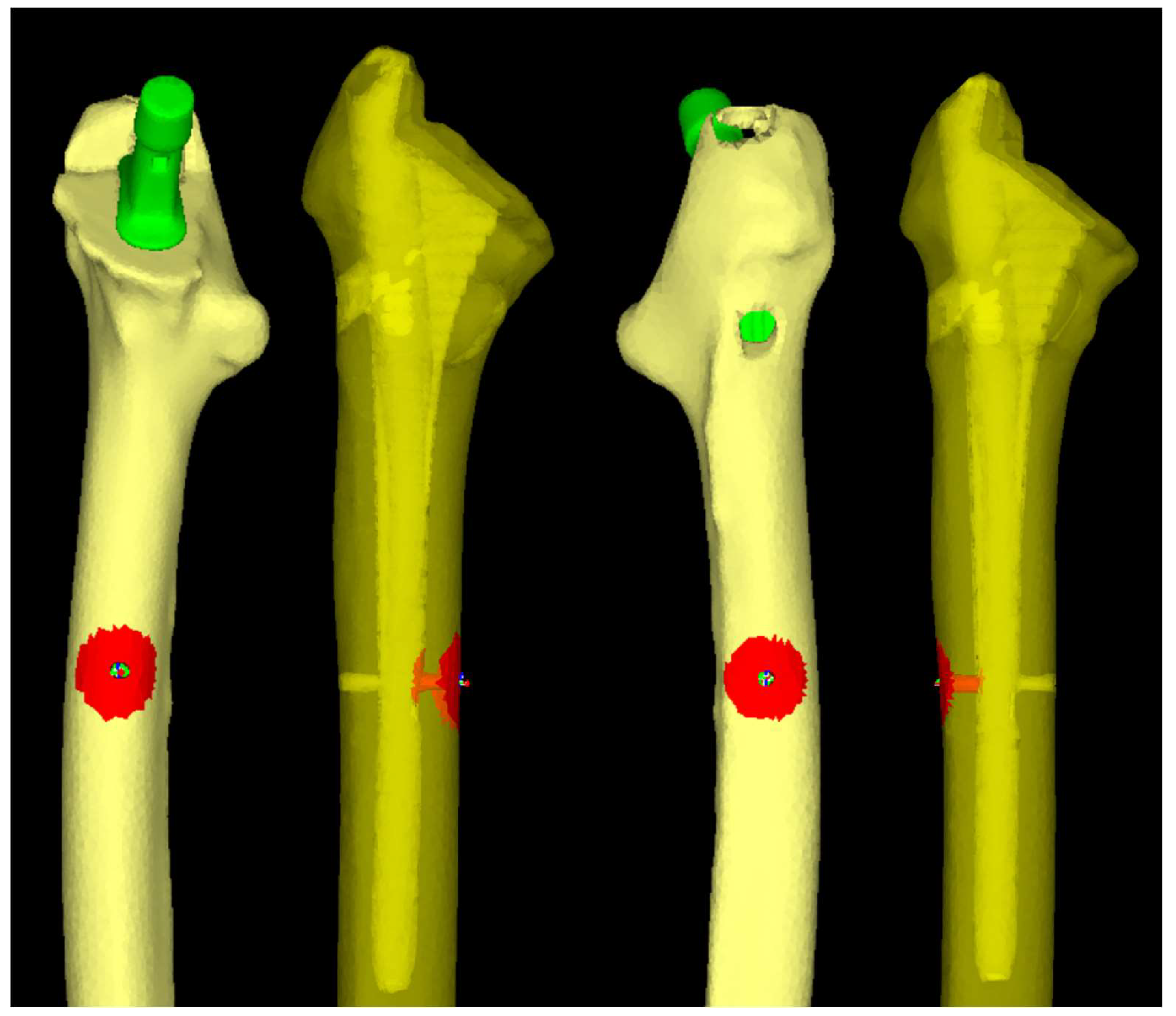

2.3.1. Software and Modeling

2.3.2. Material Parameters

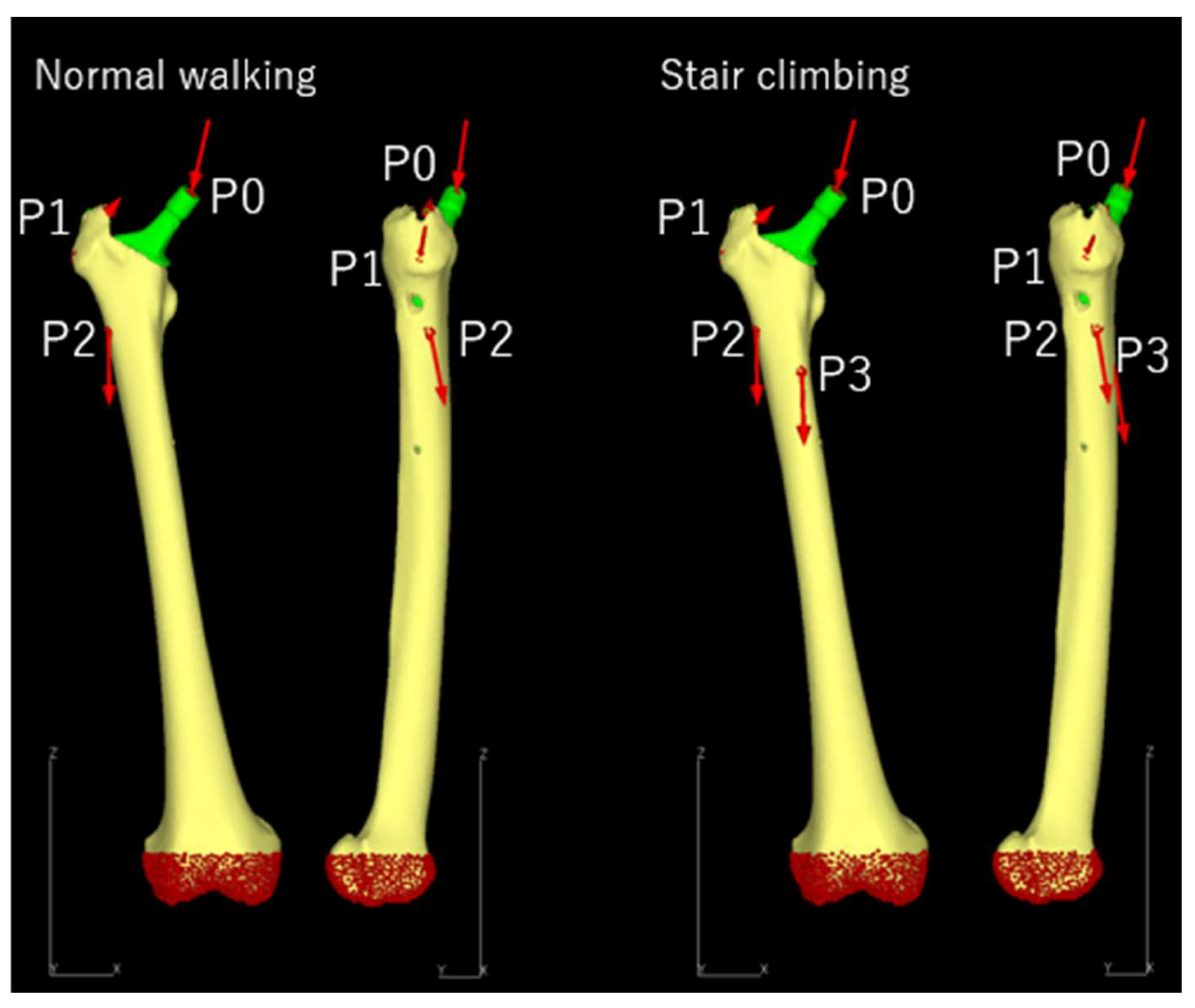

2.3.3. Loading and Boundary Conditions

2.3.4. Static Structural Analysis

2.4. Data Collection and Candidate Predictors

2.5. Outcomes

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

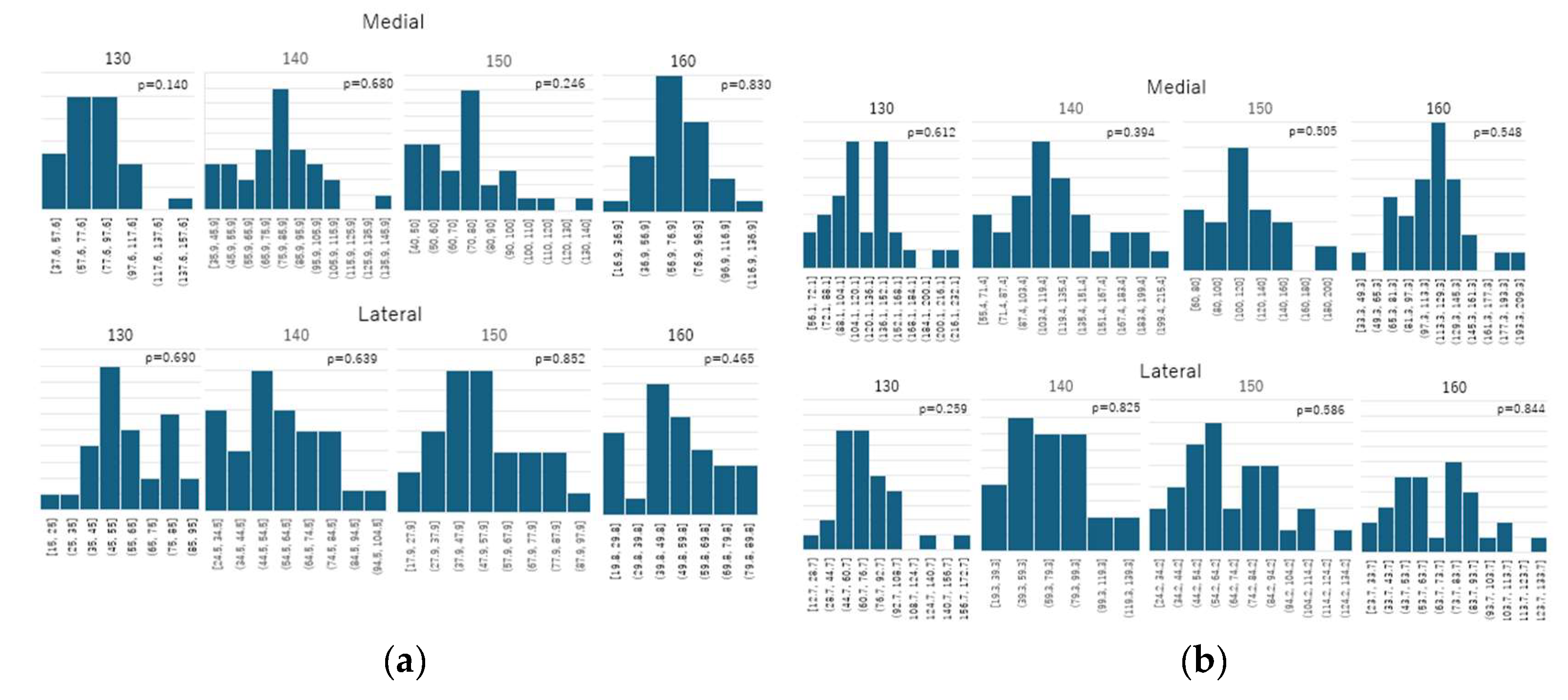

- Normal walking - medial: 130 mm: W = 0.947, p = 0.140; 140 mm: W = 0.975, p = 0.680; 150 mm: W = 0.956, p = 0.246; 160 mm: W = 0.980, p = 0.830

- Normal walking - lateral: 130 mm: W = 0.975, p = 0.690; 140 mm: W = 0.974, p = 0.639; 150 mm: W = 0.981, p = 0.852; 160 mm: W = 0.967, p = 0.465

- Stair climbing - medial: 130 mm: W = 0.973, p = 0.612; 140 mm: W = 0.964, p = 0.394; 150 mm: W = 0.969, p = 0.505; 160 mm: W = 0.970, p = 0.548

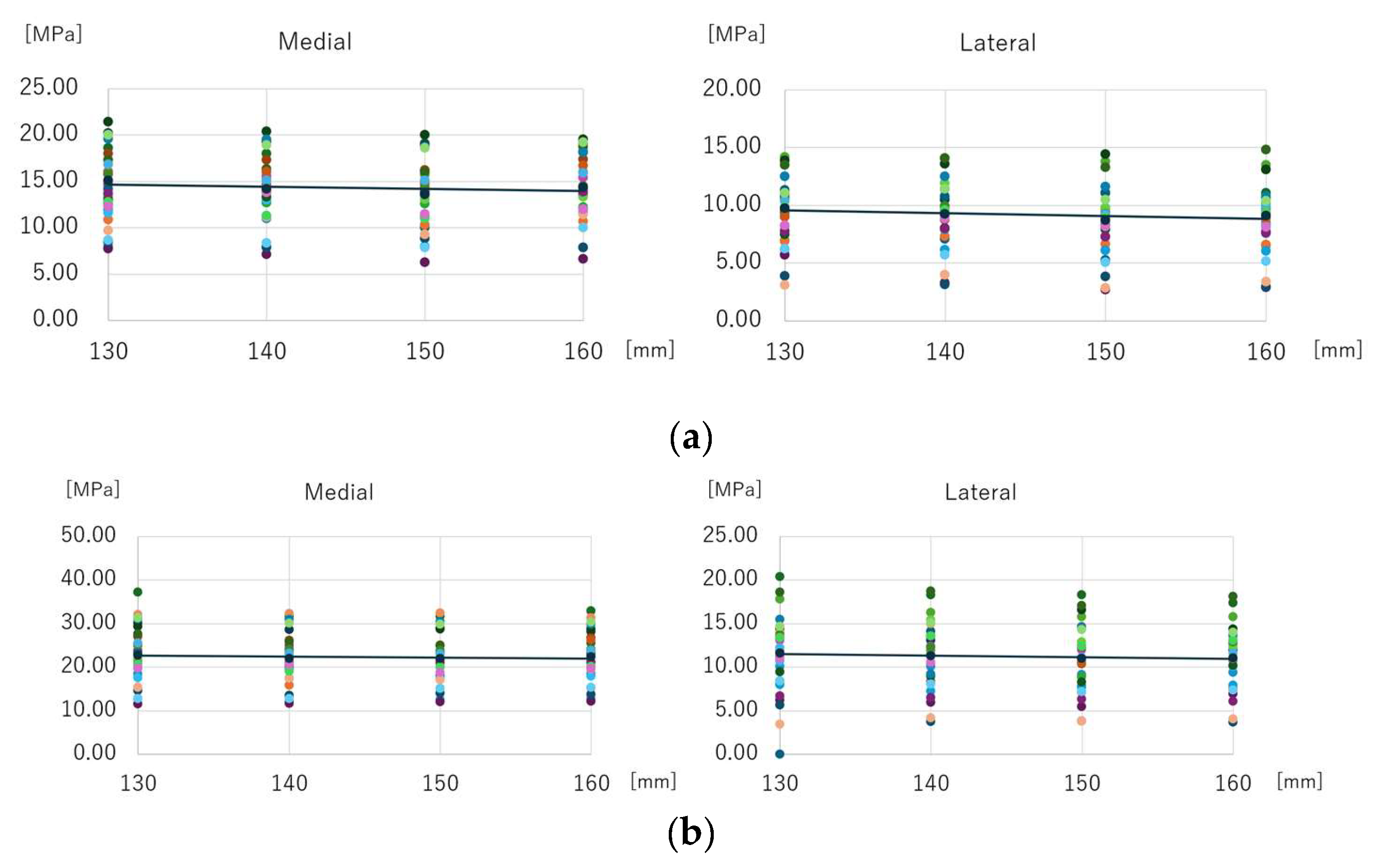

3.1. Mean Equivalent Stress Around Distal Screw-removal Holes

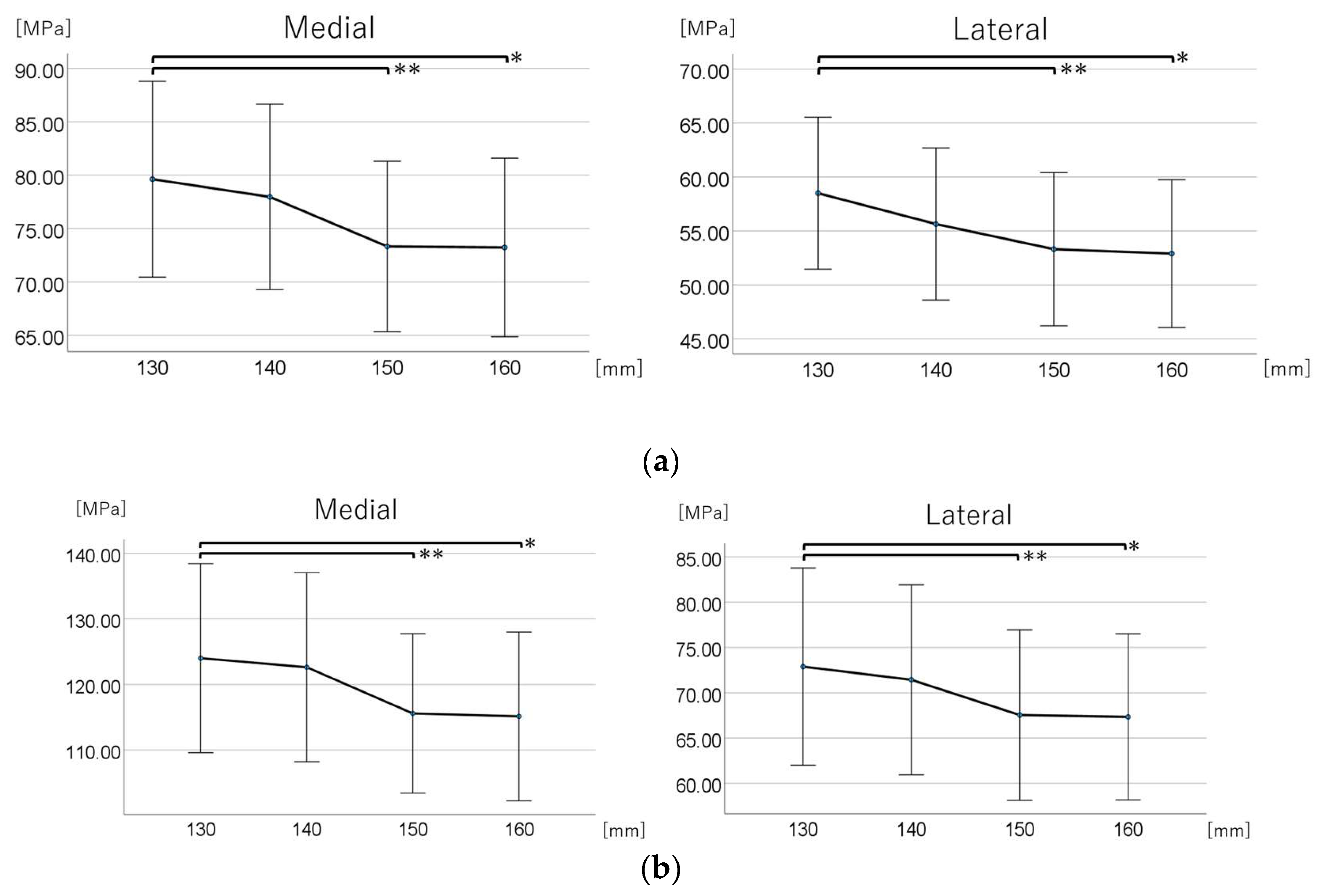

3.2. Maximum Equivalent Stress Around Distal Screw-Removal Holes

3.2.1. Normal Walking Condition

3.2.1.1. Comparison Across the Four Groups

3.2.1.2. Post Hoc Multiple Comparisons

3.2.2. Stair Climbing Condition

3.2.2.1. Comparison Across the Four Groups

3.2.2.2. Post Hoc Multiple Comparisons

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BMD | Bone mineral density |

| CFI | Canal Flare Index |

| cTHA | Conversion total hip arthroplasty |

| FEA | Finite element analysis |

| pTHA | Primary total hip arthroplasty |

References

- Hip fracture: Management. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553768/ (accessed on Jan.15 2025).

- O’Connor, M.I.; Switzer, J.A. AAOS clinical practice guideline summary: Management of hip fractures in older adults. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2022, 30, e1291–e1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geller, J.A.; Saifi, C.; Morrison, T.A.; Macaulay, W. Tip-apex distance of intramedullary devices as a predictor of cut-out failure in the treatment of peritrochanteric elderly hip fractures. Int Orthop 2010, 34, 719–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavrogenis, A.F.; Panagopoulos, G.N.; Megaloikonomos, P.D.; Igoumenou, V.G.; Galanopoulos, I.; Vottis, C.T.; Karabinas, P.; Koulouvaris, P.; Kontogeorgakos, V.A.; Vlamis, J.; et al. Complications after hip nailing for fractures. Orthopedics 2016, 39, e108–e116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokka, J.; Kirjasuo, K.; Koivisto, M.; Virolainen, P.; Junnila, M.; Seppänen, M.; Äärimaa, V.; Isotalo, K.; Mäkelä, K.T. Hip arthroplasty after failed nailing of proximal femoral fractures. Eur Orthop Traumatol 2012, 3, 231–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murena, L.; Moretti, A.; Meo, F.; Saggioro, E.; Barbati, G.; Ratti, C.; Canton, G. Predictors of cut-out after cephalomedullary nail fixation of pertrochanteric fractures: A retrospective study of 813 patients. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2018, 138, 351–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corró, S.; Óleo-Taltavull, R.; Teixidor-Serra, J.; Tomàs-Hernández, J.; Selga-Marsà, J.; García-Sánchez, Y.; Guerra-Farfán, E.; Andrés-Peiró, J.-V. Salvage hip replacement after cut-out failure of cephalomedullary nail fixation for proximal femur fractures: A case series describing the technique and results. Int Orthop 2022, 46, 2775–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archibeck, M.J.; Carothers, J.T.; Tripuraneni, K.R.; White, R.E., Jr. Total hip arthroplasty after failed internal fixation of proximal femoral fractures. J Arthroplasty 2013, 28, 168–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, S.J.; Remily, E.A.; Sax, O.C.; Pervaiz, S.S.; Delanois, R.E.; Johnson, A.J. How does conversion total hip arthroplasty compare to primary? J Arthroplasty 2021, 36, S155–S159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solarino, G.; Bizzoca, D.; Dramisino, P.; Vicenti, G.; Moretti, L.; Moretti, B.; Piazzolla, A. Total hip arthroplasty following the failure of intertrochanteric nailing: First implant or salvage surgery? World J Orthop 2023, 14, 763–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gjertsen, J.E.; Lie, S.A.; Fevang, J.M.; Havelin, L.I.; Engesaeter, L.B.; Vinje, T.; Furnes, O. Total hip replacement after femoral neck fractures in elderly patients: Results of 8,577 fractures reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop 2007, 78, 491–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tetsunaga, T.; Fujiwara, K.; Endo, H.; Noda, T.; Tetsunaga, T.; Sato, T.; Shiota, N.; Ozaki, T. Total hip arthroplasty after failed treatment of proximal femur fracture. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2017, 137, 417–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haentjens, P.; Casteleyn, P.P.; Opdecam, P. Hip arthroplasty for failed internal fixation of intertrochanteric and subtrochanteric fractures in the elderly patient. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 1994, 113, 222–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haidukewych, G.J.; Berry, D.J. Hip arthroplasty for salvage of failed treatment of intertrochanteric hip fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003, 85, 899–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winemaker, M.; Gamble, P.; Petruccelli, D.; Kaspar, S.; de Beer, J. Short-term outcomes of total hip arthroplasty after complications of open reduction internal fixation for hip fracture. J Arthroplasty 2006, 21, 682–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoffelen, D.; Haentjens, P.; Reynders, P.; Casteleyn, P.P.; Broos, P.; Opdecam, P. Hip arthroplasty for failed internal fixation of intertrochanteric and subtrochanteric fractures in the elderly patient. Acta Orthop Belg 1994, 60 Suppl 1, 135–139. [Google Scholar]

- Binkley, N.; Nickel, B.; Anderson, P.A. Periprosthetic fractures: An unrecognized osteoporosis crisis. Osteoporos Int 2023, 34, 1055–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel, M.P.; Watts, C.D.; Houdek, M.T.; Lewallen, D.G.; Berry, D.J. Epidemiology of periprosthetic fracture of the femur in 32 644 primary total hip arthroplasties: A 40-year experience. Bone Joint J 2016, 98–B, 461–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkenazi, I.; Amzallag, N.; Factor, S.; Abadi, M.; Morgan, S.; Gold, A.; Snir, N.; Warschawski, Y. Age as a risk factor for intraoperative periprosthetic femoral fractures in cementless hip hemiarthroplasty for femoral neck fractures: A retrospective analysis. Clin Orthop Surg 2024, 16, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morice, A.; Ducellier, F.; Bizot, P.; Orthopaedics and Traumatology Society of Western France (SOO). Total hip arthroplasty after failed fixation of a proximal femur fracture: Analysis of 59 cases of intra- and extra-capsular fractures. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2018, 104, 681–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, S.; Sculco, P.K.; Abdel, M.P.; Wellman, D.S.; Gausden, E.B. Total hip arthroplasty after proximal femoral nailing: Preoperative preparation and intraoperative surgical techniques. Arthroplast Today 2023, 24, 101243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.W.; Lin, C.L.; Hu, C.C.; Tsai, M.F.; Lee, M.S. Biomechanical consideration of total hip arthroplasty following failed fixation of femoral intertrochanteric fractures – A finite element analysis. Med Eng Phys 2013, 35, 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beals, R.K.; Tower, S.S. Periprosthetic fractures of the femur. An analysis of 93 fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1996, (327), 238–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeHaan, A.M.; Groat, T.; Priddy, M.; Ellis, T.J.; Duwelius, P.J.; Friess, D.M.; Mirza, A.J. Salvage hip arthroplasty after failed fixation of proximal femur fractures. J Arthroplasty 2013, 28, 855–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, X.; Zhou, Z.; Yang, J.; Shen, B.; Kang, P.; Pei, F. Total hip arthroplasty using non-modular cementless long-stem distal fixation for salvage of failed internal fixation of intertrochanteric fracture. J Arthroplasty 2015, 30, 1999–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thakur, R.R.; Deshmukh, A.J.; Goyal, A.; Ranawat, A.S.; Rasquinha, V.J.; Rodriguez, J.A. Management of failed trochanteric fracture fixation with cementless modular hip arthroplasty using a distally fixing stem. J Arthroplasty 2011, 26, 398–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moon, N.H.; Shin, W.C.; Kim, J.S.; Woo, S.H.; Son, S.M.; Suh, K.T. Cementless total hip arthroplasty following failed internal fixation for femoral neck and intertrochanteric fractures: A comparative study with 3-13 years’ follow-up of 96 consecutive patients’. Injury 2019, 50, 713–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, B.J.; Abdel, M.P.; Cross, W.W.; Berry, D.J. Hip arthroplasty after surgical treatment of intertrochanteric hip fractures. J Arthroplasty 2017, 32, 3438–3444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D’Arrigo, C.; Perugia, D.; Carcangiu, A.; Monaco, E.; Speranza, A.; Ferretti, A. Hip arthroplasty for failed treatment of proximal femoral fractures. Int Orthop 2010, 34, 939–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelini, M.; McKee, M.D.; Waddell, J.P.; Haidukewych, G.; Schemitsch, E.H. Salvage of failed hip fracture fixation. J Orthop Trauma 2009, 23, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, S.S.; Pearse, E.O.; Smith, T.O.; Hing, C.B. Outcomes of total hip arthroplasty, as a salvage procedure, following failed internal fixation of intracapsular fractures of the femoral neck: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Bone Joint J 2016, 98–B, 452–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-K.; Kim, J.T.; Alkitaini, A.A.; Kim, K.-C.; Ha, Y.-C.; Koo, K.-H. Conversion hip arthroplasty in failed fixation of intertrochanteric fracture: A propensity score matching study. J Arthroplasty 2017, 32, 1593–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Zhan, K.; Zhang, L.; Zeng, D.; Yu, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, M. Conversion to total hip arthroplasty after failed proximal femoral nail antirotations or dynamic hip screw fixations for stable intertrochanteric femur fractures: A retrospective study with a minimum follow-up of 3 years. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2017, 18, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patterson, B.M.; Salvati, E.A.; Huo, M.H. Total hip arthroplasty for complications of intertrochanteric fracture. A technical note. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1990, 72, 776–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haidukewych, G.J.; Berry, D.J. Hip Arthroplasty for Salvage of Failed Treatment of Intertrochanteric Hip Fractures. JBJS. 2003, 85, 899–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dennis, D.A.; Dingman, C.A.; Meglan, D.A.; O’Leary, J.F.; Mallory, T.H.; Berme, N. Femoral cement removal in revision total hip arthroplasty. A biomechanical analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1987, (220), 142–147. [Google Scholar]

- Larson, J.E.; Chao, E.Y.; Fitzgerald, R.H. Bypassing femoral cortical defects with cemented intramedullary stems. J Orthop Res 1991, 9, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, A.H.; Rubash, H.E. Femoral windows in revision total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1993, (291), 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimasaki, K.; Nishino, T.; Yoshizawa, T.; Watanabe, R.; Hirose, F.; Yasunaga, S.; Mishima, H. Stress Analysis in Conversion Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Finite Element Analysis on Stem Length and Distal Screw Hole. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, T.; Fang, X.; Huang, C.; Li, W.; You, R.; Wang, X.; Xia, C.; Zhang, W. Conversion hip arthroplasty using standard and long stems after failed internal fixation of intertrochanteric fractures. Orthop Surg 2023, 15, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorr, L.D.; Faugere, M.C.; Mackel, A.M.; Gruen, T.A.; Bognar, B.; Malluche, H.H. Structural and cellular assessment of bone quality of proximal femur. Bone 1993, 14, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Universia stem. Available online: https://formedic.teijin-nakashima.co.jp/products/detail/?id=524 (accessed on 20 November 2024).

- Hirata, Y.; Inaba, Y.; Kobayashi, N.; Ike, H.; Fujimaki, H.; Saito, T. Comparison of mechanical stress and change in bone mineral density between two types of femoral implant using finite element analysis. J Arthroplasty 2013, 28, 1731–1735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tano, A.; Oh, Y.; Fukushima, K.; Kurosa, Y.; Wakabayashi, Y.; Fujita, K.; Yoshii, T.; Okawa, A. Potential bone fragility of mid-shaft atypical femoral fracture: Biomechanical analysis by a CT-based nonlinear finite element method. Injury 2019, 50, 1876–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keyak, J.H.; Rossi, S.A.; Jones, K.A.; Skinner, H.B. Prediction of femoral fracture load using automated finite element modeling. J Biomech 1998, 31, 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergmann, G.; Bender, A.; Dymke, J.; Duda, G.; Damm, P. Standardized loads acting in hip implants. PLOS One 2016, 11, e0155612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heller, M.O.; Bergmann, G.; Kassi, J.P.; Claes, L.; Haas, N.P.; Duda, G.N. Determination of muscle loading at the hip joint for use in pre-clinical testing. J Biomech 2005, 38, 1155–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biemond, J.E.; Aquarius, R.; Verdonschot, N.; Buma, P. Frictional and bone ingrowth properties of engineered surface topographies produced by electron beam technology. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2011, 131, 711–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noble, P.C.; Alexander, J.W.; Lindahl, L.J.; Yew, D.T.; Granberry, W.M.; Tullos, H.S. The anatomic basis of femoral component design. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1988, (235), 148–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Chiu, K.Y.; Wang, M. Hip arthroplasty for failed internal fixation of intertrochanteric fractures. J Arthroplasty 2004, 19, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panjabi, M.M.; Trumble, T.; Hult, J.E.; Southwick, W.O. Effect of femoral stem length on stress raisers associated with revision hip arthroplasty. J Orthop Res 1985, 3, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edgerton, B.C.; An, K.N.; Morrey, B.F. Torsional strength reduction due to cortical defects in bone. J Orthop Res 1990, 8, 851–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, K.W.K.; Gilbody, J.; Jameson, T.; Miles, A.W. The effect of 4 mm bicortical drill hole defect on bone strength in a pig femur model. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2010, 130, 797–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howieson, A.J.; Jones, M.D.; Theobald, P.S. The change in energy absorbed post removal of metalwork in a simulated paediatric long bone fracture. J Child Orthop 2014, 8, 443–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brooks, D.B.; Burstein, A.H.; Frankel, V.H. The biomechanics of torsional fractures. The stress concentration effect of a drill hole. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1970, 52, 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morishima, T.; Ginsel, B.L.; Choy, G.G.H.; Wilson, L.J.; Whitehouse, S.L.; Crawford, R.W. Periprosthetic fracture torque for Short versus Standard cemented hip stems: An experimental in vitro study. J Arthroplasty 2014, 29, 1067–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakubowitz, E.; Seeger, J.B.; Lee, C.; Heisel, C.; Kretzer, J.P.; Thomsen, M.N. Do short-stemmed-prostheses induce periprosthetic fractures earlier than standard hip stems? A biomechanical ex-vivo study of two different stem designs. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2009, 129, 849–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, N.E.; Burton, A.; Maheson, M.; Morlock, M.M. Biomechanics of short hip endoprostheses — The risk of bone failure increases with decreasing implant size. Clin Biomech (Bristol) 2010, 25, 666–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Materials | Young’s modulus [GPa] | Poisson’s ratio | |

| Femoral bone | Heterogeneous model | Keyak et al. [45] | 0.40 |

| Stem | Titanium alloy (Ti-6Al-4V) | 109 | 0.28 |

| Normal walking | |||||

| Force | X (N) | Y (N) | Z (N) | Acting point | % |

| Hip contact | Lt. 54.0 / Rt. −54.0 | 32.8 | −229.2 | P0 | 238 |

| ABD | Lt. 58.0 / Rt. −58.0 | 4.3 | 86.5 | P1 | 104 |

| TFL-P | Lt. 7.2 / Rt. −7.2 | 11.6 | 13.2 | P1 | 19 |

| TFL-D | Lt. −0.5 / Rt. 0.5 | −0.7 | −19.0 | P1 | 19 |

| P1 total force | Lt. −64.7 / Rt. 64.7 | −15.2 | 80.7 | P1 | 105 |

| VL | Lt. −0.9 / Rt. 0.9 | −18.5 | −92.9 | P2 | 95 |

| Stair climbing | |||||

| Force | X (N) | Y (N) | Z (N) | Acting point | % |

| Hip contact | Lt. 59.3 / Rt. −59.3 | 60.6 | −236.3 | P0 | 251 |

| ABD | Lt. 70.1 / Rt. −70.1 | 28.8 | 84.9 | P1 | |

| ITT-P | Lt. 10.5 / Rt. −10.5 | 3.0 | 12.8 | P1 | |

| ITT-D | Lt. −0.5 / Rt. 0.5 | −0.8 | −16.8 | P1 | |

| TFL-P | Lt. 3.1 / Rt. −3.1 | 4.9 | 2.9 | P1 | |

| TFL-D | Lt. −0.2 / Rt. 0.2 | −0.3 | −6.5 | P1 | |

| P1 total force | Lt. −83.0 / Rt. 83.0 | −35.6 | 77.3 | P1 | 119 |

| VL | Lt. −2.2 / Rt. 2.2 | −22.4 | −135.1 | P2 | 137 |

| VM | Lt. −8.8 / Rt. 8.8 | −39.6 | −267.1 | P3 | 270 |

| Age [years] | 66.5±8.7 |

| Height [m] | 1.53±0.06 |

| Body weight [kg] | 53.5±9.0 |

| Body mass index [kg/m2] | 22.7±3.2 |

| Side [limb] | Left 16 Right 14 |

| Bone mineral density of the femoral neck [g/cm2] | 0.61±0.13 |

| Canal flare index | 4.17±0.42 |

| Length of distal screw [mm] | 25.7±1.7 |

| Femoral anteversion [degree] | 21.69±10.69 |

| Medial | Lateral | |||

| Stem Length, mm | Maximum Equivalent Stress (MPa) | 95% CI (MPa) | Maximum Equivalent Stress (MPa) | 95% CI (MPa) |

| Normal walking | ||||

| 130 | 79.630 | (70.461–88.799) | 58.500 | (51.457–65.543) |

| 140 | 77.970 | (69.284–86.656) | 55.640 | (48.591–62.689) |

| 150 | 73.330 | (65.342–81.318) | 53.310 | (46.203–60.417) |

| 160 | 73.235 | (64.877–81.593) | 52.900 | (46.046–59.754) |

| Stair climbing | ||||

| 130 | 124.017 | (109.607–138.426) | 72.887 | (62.000–83.773) |

| 140 | 122.635 | (108.221–137.050) | 71.427 | (60.941–81.914) |

| 150 | 115.587 | (103.449–127.724) | 67.537 | (58.137–76.937) |

| 160 | 115.147 | (102.283–128.010) | 67.330 | (58.170–76.490) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).