Submitted:

08 January 2025

Posted:

09 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Data Collection and Survey

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

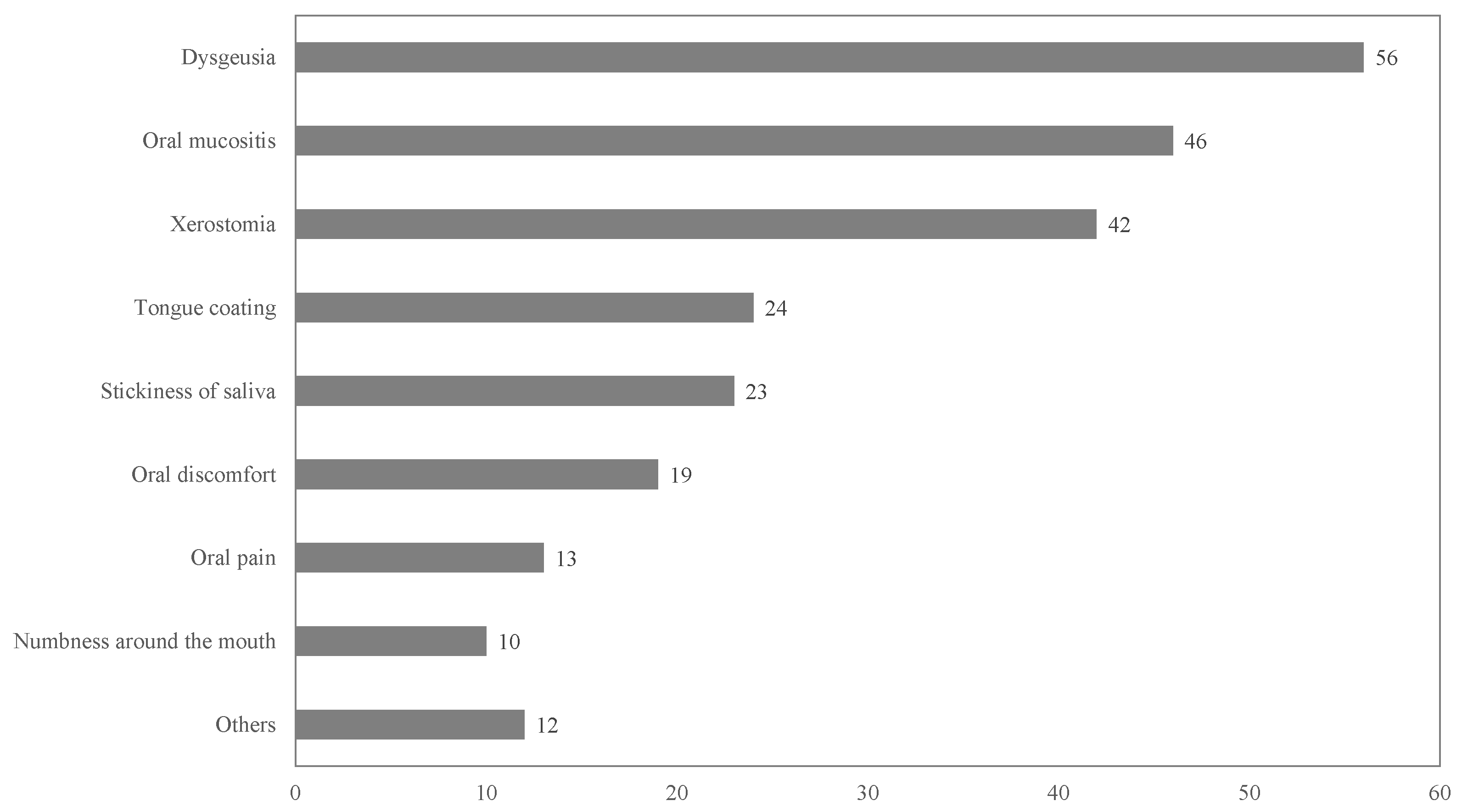

3.1. Incidence of Oral Adverse Events

3.2. Patient Needs for Management of Oral Adverse Events by Medical Professionals

3.3. The Relationship Between Patient Characteristics and Major Oral Adverse Events

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MASCC | Multinational association of supportive care in cancer |

| ISOO | International society of oral oncology |

| PRO-CTCAE | Patient-Reported Outcome Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events |

| 5-FU | 5-fluorouracil |

| ICIs | Immune checkpoint inhibitors |

| CDDP | Cisplatin |

| EGFR | Epidermal growth factor receptor |

References

- Japanese Association of Supportive Care in Cancer, Japanese Association of Oral Supportive Care in Cancer: Clinical Guidance of Management for Mucositis; Kanehara Co., Ltd.: Tokyo, 2020.

- Nagasueshoten, K. Japanese Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy, Japanese Association of Oral Supportive Care in Cancer: Guidelines for the Oral Management of Hematopoietic Cell Transplant Patients. 1st ed, 2022(in Japanese).

- Elad, S.; Cheng, K.K.F.; Lalla, R.V.; Yarom, N.; Hong, C.; Logan, R.M.; Bowen, J.; Gibson, R.; Saunders, D.P.; Zadik, Y.; et al. MASCC/ISOO clinical practice guidelines for the management of mucositis secondary to cancer therapy. Cancer 2020, 126, 4423–4431. [CrossRef]

- Mercadante, V.; Jensen, S.B.; Smith, D.K.; Bohlke, K.; Bauman, J.; Brennan, M.T.; Coppes, R.P.; Jessen, N.; Malhotra, N.K.; Murphy, B.; et al. Salivary Gland Hypofunction and/or xerostomia Induced by Nonsurgical Cancer Therapies: ISOO/MASCC/ASCO Guideline [ISOO/MASCC/ASCO guideline]. J Clin Oncol 2021, 39, 2825–2843. [CrossRef]

- Soga, Y.; Sugiura, Y.; Takahashi, K.; Nishimoto, H.; Maeda, Y.; Tanimoto, M.; Takashiba, S. Progress of oral care and reduction of oral mucositis-a pilot study in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation ward. Support Care Cancer 2011, 19, 303–307. [CrossRef]

- Yamagata, K.; Arai, C.; Sasaki, H.; Takeuchi, Y.; Onizawa, K.; Yanagawa, T.; Ishibashi, N.; Karube, R.; Shinozuka, K.; Hasegawa, Y.; et al. The effect of oral management on the severity of oral mucositis during hematopoietic SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant 2012, 47, 725–730. [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, K.; Kodama, Y.; Tanaka, Y.; Pak, K.; Soga, M.; Toyama, A.; Katsura, K.; Takagi, R. Pharmacist involved education program in a multidisciplinary team for oral mucositis: Its impact in head-and-neck cancer patients. PLOS ONE 2021, 16, e0260026. [CrossRef]

- Çakmak, S.; Nural, N. Incidence of and risk factors for development of oral mucositis in outpatients undergoing cancer chemotherapy. Int J Nurs Pract 2019, 25, e12710. [CrossRef]

- Wilberg, P.; Hjermstad, M.J.; Ottesen, S.; Herlofson, B.B. Chemotherapy-associated oral sequelae in patients with cancers outside the head and neck region. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014, 48, 1060–1069. [CrossRef]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Guidance for industry. Patient-reported outcome measures: Use in medical product development to support labeling claims, 2009. Available online: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM193282.pdf (accessed on 5 Jun 2022).

- Japan Clinical Oncology Group. NCI- PRO-CTCAE® ITEMS-Japanese Item Library. version 1.0. Available online: http://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov/pro-ctcae/instruments/pro-ctcae/pro-ctcaeJapanese.pdf (accessed on 5 Jun 2022).

- Kanda, Y. Investigation of the freely available easy-to-use software ‘EZR’ for medical statistics. Bone Marrow Transplant 2013, 48, 452–458 [Advance online publication 3 Dec 2012]. [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.J.; Gupta, A. Management of cancer therapy–associated oral mucositis: JCO. J Oncol Pract 2020, 16, 103–109.

- Jones, S.E.; Erban, J.; Overmoyer, B.; Budd, G.T.; Hutchins, L.; Lower, E.; Laufman, L.; Sundaram, S.; Urba, W.J.; Pritchard, K.I.; et al. Randomized Phase III Study of Docetaxel Compared With Paclitaxel in Metastatic Breast Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005, 23, 5542–5551. [CrossRef]

- Holmes, S. Food avoidance in patients undergoing cancer chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 1993, 1, 326–330. [CrossRef]

- Amézaga, J.; Alfaro, B.; Ríos, Y.; Larraioz, A.; Ugartemendia, G.; Urruticoechea, A.; Tueros, I. Assessing taste and smell alterations in cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy according to treatment. Support Care Cancer 2018, 26, 4077–4086. [CrossRef]

- Speck, R.M.; DeMichele, A.; Farrar, J.T.; Hennessy, S.; Mao, J.J.; Stineman, M.G.; Barg, F.K. Taste alteration in breast cancer patients treated with taxane chemotherapy: Experience, effect, and coping strategies. Support Care Cancer 2013, 21, 549–555. [CrossRef]

- Steinbach, S.; Hummel, T.; Böhner, C.; Berktold, S.; Hundt, W.; Kriner, M.; Heinrich, P.; Sommer, H.; Hanusch, C.; Prechtl, A.; et al. Qualitative and quantitative assessment of taste and smell changes in patients undergoing chemotherapy for breast cancer or gynecologic malignancies. J Clin Oncol 2009, 27, 1899–1905. [CrossRef]

- Peterson, D.E.; Minah, G.E.; Overholser, C.D.; Suzuki, J.B.; Depaola, L.G.; Stansbury, D.M.; Williams, L.T.; Schimpff, S.C. Microbiology of acute periodontal infection in myelosuppressed cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 1987, 5, 1461–1468. [CrossRef]

- Raber-Durlacher, J.E.; Epstein, J.B.; Raber, J.; van Dissel, J.T.; van Winkelhoff, A.J.; Guiot, H.F.L.; van der Velden, U. Periodontal infection in cancer patients treated with high-dose chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 2002, 10, 466–473. [CrossRef]

- Lalla, R.V.; Sonis, S.T.; Peterson, D.E. Management of oral mucositis in patients who have cancer. Dent Clin North Am 2008, 52, 61–77. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, S.B.; Mouridsen, H.T.; Reibel, J.; Brünner, N.; Nauntofte, B. Adjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer patients induces temporary salivary gland hypofunction. Oral Oncol 2008, 44, 162–173. [CrossRef]

- Katura, K. Manual for Xerostomia Management in Cancer Treatment; Foundation for Promotion of Cancer Research: Tokyo, 2019(in Japanese).

- Vissink, A.; Schaub, R.M.; van Rijn, L.J.; Gravenmade, E.J.; Panders, A.K.; Vermey, A. The efficacy of mucin-containing artificial saliva in alleviating symptoms of xerostomia. Gerodontology 1987, 6, 95–101. [CrossRef]

- Vissink, A.; Jansma, J.; Spijkervet, F.K.; Burlage, F.R.; Coppes, R.P. Oral sequelae of head and neck radiotherapy. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 2003, 14, 199–212. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, S.B.; Pedersen, A.M.L.; Vissink, A.; Andersen, E.; Brown, C.G.; Davies, A.N.; Dutilh, J.; Fulton, J.S.; Jankovic, L.; Lopes, N.N.; et al. A systematic review of salivary gland hypofunction and xerostomia induced by cancer therapies: Prevalence, severity and impact on quality of life. Support Care Cancer 2010, 18, 1039–1060. [CrossRef]

- Honma, T.; Denpoya, A.; Narui, H. Team medical care for cancer outpatients on anticancer medication therapy: Reality and challenges. Aomori J Health Welf 2021, 3, 10–19.

- Filho, O.M.; Giobbie-Hurder, A.; Lin, N.U.; Faggen, M.; Come, S.; Openshaw, T.; Constantine, M.; Walsh, J.; Freedman, R.A.; Schneider, B.; et al. A dynamic portrait of adverse events for breast cancer patients: Results from a phase II clinical trial of eribulin in advanced HER2-negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2021, 185, 135–144. [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, T.M.; Ryan, S.J.; Bennett, A.V.; Stover, A.M.; Saracino, R.M.; Rogak, L.J.; Jewell, S.T.; Matsoukas, K.; Li, Y.; Basch, E. The association between Clinician-Based Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) and Patient-Reported Outcomes (PRO): A Systematic Review. Support Care Cancer 2016, 24, 3669–3676. [CrossRef]

- Falchook, A.D.; Green, R.; Knowles, M.E.; Amdur, R.J.; Mendenhall, W.; Hayes, D.N.; Grilley-Olson, J.E.; Weiss, J.; Reeve, B.B.; Mitchell, S.A.; et al. Comparison of Patient- and Practitioner-Reported Toxic Effects associated with chemoradiotherapy for head and neck cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2016, 142, 517–523. [CrossRef]

| Q 1. | What type of oral adverse events do you have? |

| 1. Mucositis. 2. Tongue coating. 3. Dysgeusia. 4. Xerostomia. 5. Stickiness of saliva. 6. Numbness around the mouth 7. Oral pain 8. Oral discomfort. 8. None. | |

| Q 2. | Do you want to improve the oral adverse events? |

| 1. Yes. 2. No. | |

| Q 3. | Do the oral symptoms cause problems in your daily life? |

| 1. Yes. 2. No. | |

| Q 4. | What issues have become a problem in your daily life? |

| 1. Reduced food intake. 2. Increased food intake. 3. Drinking too much. 4. Drinking not much. 5. Difficulty swallowing. 6. Sleeplessness. 7. Impaired speech. 8. None. | |

| Q 5. | Do you want medication or a treatment method for oral adverse events? |

| 1. Yes. 2. No. | |

| Q 6. | Do you want dentist intervention to improve your oral adverse events? |

| 1. Yes. 2. No | |

| Q 7. | How severe are the oral adverse events compared with non-oral adverse events? |

| 1. More severe. 2. similar. 3. Not as severe. |

| Patient characteristics | n | % | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 108 | 50.0% | |

| Female | 108 | 50.0% | ||

| Age group (years old) | AYA (18–39) | 8 | 3.7% | |

| Middle aged (40–69) | 122 | 56.5% | ||

| Old aged (>70) | 86 | 39.8% | ||

| Cancer type | Breast cancer | 52 | 24.1% | |

| Lung cancer | 45 | 20.8% | ||

| Gastrointestinal cancer | 37 | 17.1% | ||

| Liver, biliary tract, pancreatic cancer | 18 | 8.3% | ||

| Urological cancer | 17 | 7.9% | ||

| Gynecological cancer | 14 | 6.5% | ||

| Hematological cancer | 12 | 5.6% | ||

| Head and neck cancer | 7 | 3.2% | ||

| Soft tissue sarcoma | 3 | 1.4% | ||

| Others | 11 | 5.1% | ||

| Cancer drug therapy | ICIs (Atezolizumab, Durvalumab, Pembrolizumab, Nivolumab, Avelumab) | 67 | 31.0% | |

| Taxane-based (DTX, PTX, nab-PTX, CBZ) | 49 | 22.7% | ||

| 5FU-based (5FU, TS-1, Cape) | 33 | 15.3% | ||

| Anthracycline-based | 8 | 3.7% | ||

| CDDP-based | 4 | 1.9% | ||

| EGFR antibodies (Cet, Pani) | 3 | 1.4% | ||

| Others | 52 | 24.1% | ||

| AYA, Adolescent and young adult; ICIs, Immune checkpoint inhibitors; DTX, Docetaxel; PTX, Paclitaxel; nab-PTX, nab-Paclitaxel; CBZ, Cabazitaxel acetonate; Cape, Capecitabine; CDDP, Cisplatin; EGFR, Epidermal growth factor receptor; Cet, Cetuximab; Pani, Panitumumab | ||||

| With | Without | Multivariate analysis | |||||

| n | n(%) | n(%) | OR | 95%CI | P-value | ||

| 216 | 127(58.8) | 89(41.2) | |||||

| Sex | Male | 109 | 54(49.5) | 55(50.5) | |||

| Female | 107 | 73(68.2) | 34(31.8) | 1.14 | 0.48-2.70 | 0.76 | |

| Age group (years) | AYA (18–39) | 8 | 4(50.0) | 4(50.0) | |||

| Middle-aged (40–69) | 122 | 77(63.1) | 45(36.9) | 3.21 | 0.59-17.70 | 0.18 | |

| Older (> 70) | 86 | 46(53.5) | 40(46.5) | 2.7 | 0.45-16.10 | 0.28 | |

| Cancer type | Others | 11 | 4(36.4) | 7(63.6) | |||

| Breast cancer | 51 | 38(74.5) | 13(25.5) | 6.38 | 1.05-38.90 | 0.04* | |

| Lung cancer | 46 | 18(39.1) | 28(60.9) | 1.45 | 0.31-6.73 | 0.64 | |

| Gastrointestinal cancer | 37 | 27(73.0) | 10(27.0) | 2.79 | 0.42-18.40 | 0.29 | |

| Liver, biliary tract, pancreatic cancer | 18 | 12(66.7) | 6(33.3) | 1.42 | 0.21-9.70 | 0.72 | |

| Urological cancer | 17 | 6(35.3) | 11(64.7) | 1.29 | 0.22-7.62 | 0.78 | |

| Gynecological cancer | 14 | 9(64.3) | 5(35.7) | 6 | 0.82-43.90 | 0.08 | |

| Hematological cancer | 12 | 7(58.3) | 5(41.7) | 5.61 | 0.76-41.70 | 0.09 | |

| Head and neck cancer | 7 | 5(71.4) | 2(28.6) | 5.25 | 0.57-48.10 | 0.14 | |

| Soft tissue sarcoma | 3 | 1(33.3) | 2(66.7) | 0.9 | 0.05-17.30 | 0.95 | |

| Cancer drug therapy | Others | 51 | 26(51.0) | 25(49.0) | |||

| 5FU-based (5FU, S1, Cape) | 33 | 27(81.8) | 6(18.2) | 9.37 | 1.74-50.40 | < 0.01* | |

| Taxanes-based (DTX, PTX, nab-PTX, CBZ) | 49 | 37(75.5) | 12(24.5) | 5.63 | 1.91-16.60 | < 0.01* | |

| Anthracyclines-based | 8 | 6(75.0) | 2(25.0) | 1.95 | 0.35-10.90 | 0.45 | |

| ICIs (Atezolizumab,Durvalumab,Pembrolizumab,Nivolumab,Avelumab) | 68 | 27(39.7) | 41(60.3) | 1.69 | 0.55-5.19 | 0.36 | |

| EGFR antibodies (Cet, Pani) | 3 | 1(33.3) | 2(66.7) | 0.84 | 0.05-14.50 | 0.91 | |

| CDDP | 4 | 3(75.0) | 1(25.0) | 11.1 | 0.80-156.00 | 0.07 | |

| †Significant association (p-value < 0.05 ) | |||||||

| OR:odds ratio | |||||||

| CI:confidence interval | |||||||

| With | Without | Multivariate analysis | |||||

| n | n(%) | n(%) | OR | 95%CI | P-value | ||

| Dysgeusia | 216 | 56(25.9) | 160(74.1) | ||||

| Others | 51 | 9(17.6) | 42(82.4) | ||||

| 5FU-based (5FU, S1, Cape) | 33 | 12(36.4) | 21(63.6) | 1.36 | 0.23-8.19 | 0.74 | |

| Taxanes-based (DTX, PTX, nab-PTX, CBZ) | 49 | 22(44.9) | 27(55.1) | 4.76 | 1.61-14.10 | < 0.01* | |

| Anthracyclines-based | 8 | 4(50.0) | 4(50.0) | 3.50 | 0.71-17.30 | 0.13 | |

| ICIs (Atezolizumab,Durvalumab,Pembrolizumab,Nivolumab,Avelumab) | 68 | 7(10.3) | 61(89.7) | 0.74 | 0.19-2.89 | 0.66 | |

| EGFR antibodies (Cet, Pani) | 3 | 1(33.3) | 2(66.7) | 1.19 | 0.06-24.60 | 0.91 | |

| CDDP | 4 | 1(25.0) | 3(75.0) | 3.15 | 0.21-47.90 | 0.41 | |

| Oral mucositis | 216 | 46(21.3) | 170(78.7) | ||||

| Others | 51 | 13(25.5) | 38(74.5) | ||||

| 5FU-based (5FU, S1, Cape) | 33 | 13(39.4) | 20(60.6) | 2.70E+00 | 0.44-16.50 | 0.28 | |

| Taxanes-based (DTX, PTX, nab-PTX, CBZ) | 49 | 14(28.6) | 35(71.4) | 1.85E+00 | 0.65-5.25 | 0.25 | |

| Anthracyclines-based | 8 | 2(25.0) | 6(75.0) | 7.38E-01 | 0.13-4.21 | 0.73 | |

| ICIs (Atezolizumab,Durvalumab,Pembrolizumab,Nivolumab,Avelumab) | 68 | 4(5.9) | 64(94.1) | 4.48E-01 | 0.10-2.00 | 0.29 | |

| EGFR antibodies (Cet, Pani) | 3 | 0(0.0) | 3(100.0) | 7.68E-08 | 0-Inf | 0.99 | |

| CDDP | 4 | 0(0.0) | 4(100.0) | 1.50E-07 | 0-Inf | 0.99 | |

| Xerostomia | 216 | 42(19.4) | 174(80.6) | ||||

| Others | 51 | 6(11.8) | 45(88.2) | ||||

| 5FU-based (5FU, S1, Cape) | 33 | 11(33.3) | 22(66.7) | 1.65E+01 | 1.74-157.00 | 0.01* | |

| Taxanes-based (DTX, PTX, nab-PTX, CBZ) | 49 | 11(22.4) | 38(77.6) | 2.65E+00 | 0.80-8.79 | 0.11 | |

| Anthracyclines-based | 8 | 2(25.0) | 6(75.0) | 2.05E+00 | 0.32-13.10 | 0.45 | |

| ICIs (Atezolizumab,Durvalumab,Pembrolizumab,Nivolumab,Avelumab) | 68 | 11(16.2) | 57(83.8) | 2.29E+00 | 0.55-9.53 | 0.25 | |

| EGFR antibodies (Cet, Pani) | 3 | 0(0.0) | 3(100.0) | 8.49E-07 | 0-Inf | 1.00 | |

| CDDP | 4 | 1(25.0) | 3(75.0) | 7.63E+00 | 0.39-148.00 | 0.18 | |

| †Significant association (p-value < 0.05) |

|||||||

| OR:odds ratio | |||||||

| CI:confidence interval | |||||||

| Response | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Yes | No | ||

| Item | n(%) | n(%) | n(%) | |

| Hope for improvement of oral adverse events | 115(90.6) | 68(53.5) | 47(37.0) | |

| Impact on their daily lives | 113(89.0) | 44(34.6) | 69(54.3) | |

| Hope for professional oral care (Well-Trained Dentist and Dental Hygienist) | 102(80.3) | 34(26.8) | 68(53.5) | |

| more severe | similar | not as severe | ||

| Comparison of the severity of oral adverse events and other adverse events | 113(89.0) | 5(3.9) | 27(21.3) | 81(63.8) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).