Submitted:

31 December 2024

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patient Selection

2.2. Conventional Echocardiographic Examination

2.3. Measurement of Epicardial Adipose Tissue Thickness

2.4. Hemodynamic Indices

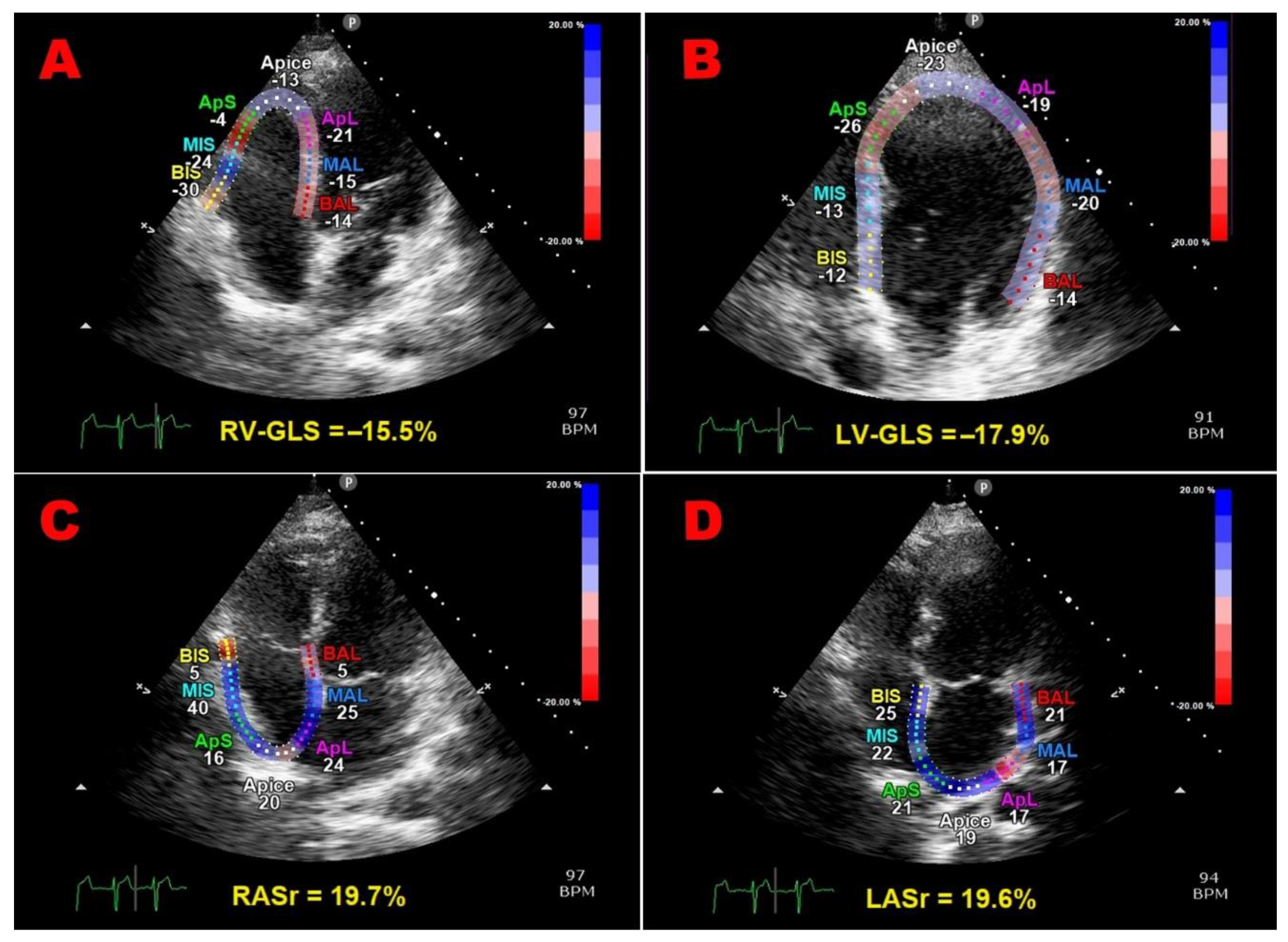

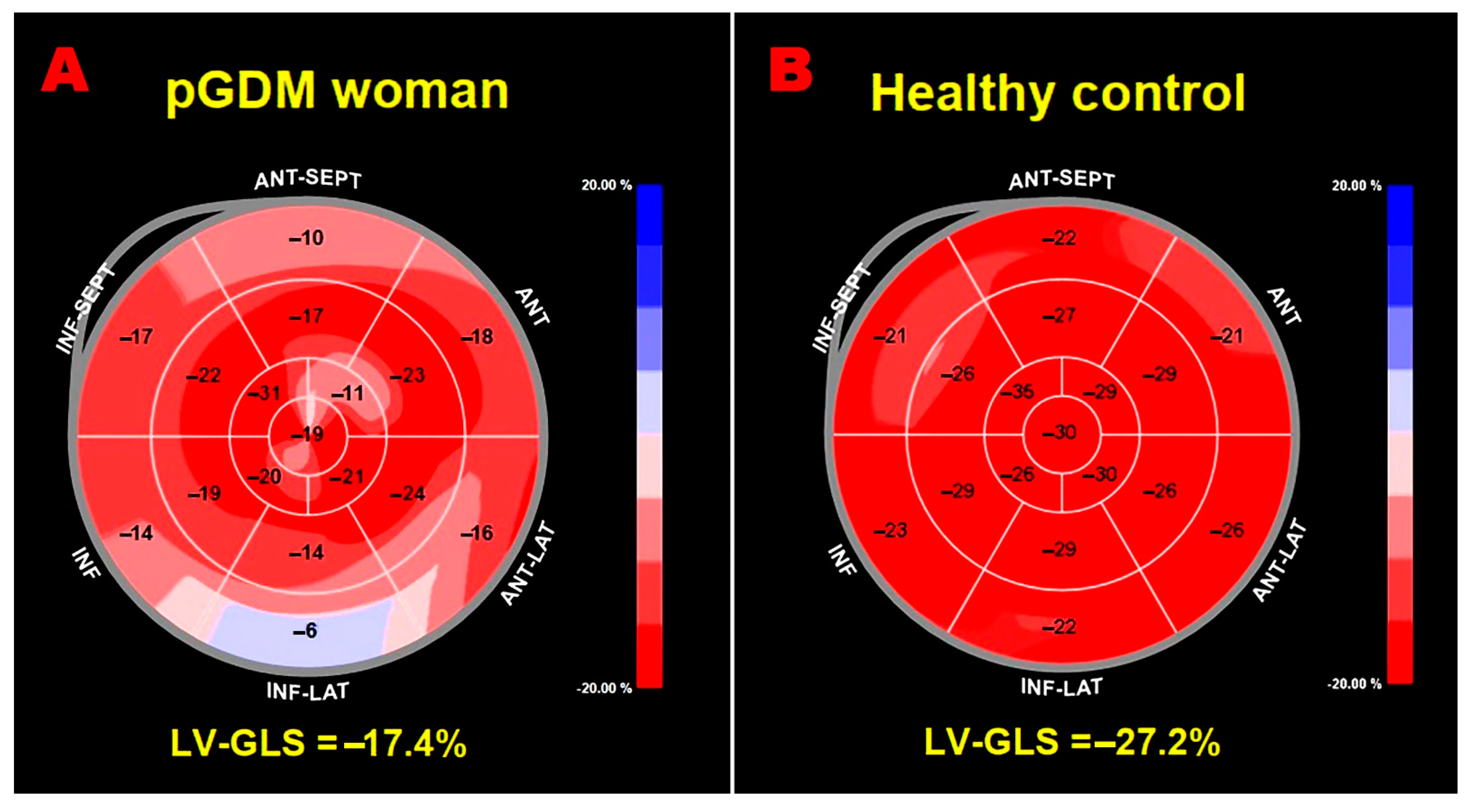

2.5. Speckle-Tracking Echocardiography

2.6. Carotid Ultrasonography

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Clinical Findings

3.2. Instrumental Findings

3.3. Follow-Up Data

3.4. Measurement Variability

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings of the Present Study

4.2. Comparison with Previous Studies and Interpretation of Results

4.3. Implications for Clinical Practice

4.4. Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, H.; Li, N.; Chivese, T.; Werfalli, M.; Sun, H.; Yuen, L.; Hoegfeldt, C.A.; Elise Powe, C.; Immanuel, J.; Karuranga, S.; et al. IDF Diabetes Atlas: Estimation of Global and Regional Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Prevalence for 2021 by International Association of Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group's Criteria. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2022, 183, 109050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, W.; Luo, C.; Huang, J.; Li, C.; Liu, Z.; Liu, F. Gestational diabetes mellitus and adverse pregnancy outcomes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2022, 377, e067946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, B.; Cai, J.; Xu, Y.; Long, Y.; Deng, L.; Lin, S.; Zhang, J.; Yang, J.; Zhong, L.; Luo, Y.; et al. Early Diagnosed Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Is Associated With Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 105, dgaa633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, W.L. Jr; Scholtens, D.M.; Kuang, A.; Linder, B.; Lawrence, J.M.; Lebenthal, Y.; McCance, D.; Hamilton, J.; Nodzenski, M.; Talbot, O.; et al. Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome Follow-up Study (HAPO FUS): Maternal Gestational Diabetes Mellitus and Childhood Glucose Metabolism. Diabetes Care. 2019, 42, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vounzoulaki, E.; Khunti, K.; Abner, S.C.; Tan, B.K.; Davies, M.J.; Gillies, C.L. Progression to type 2 diabetes in women with a known history of gestational diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020, 369, 1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Retnakaran, R.; Shah, B.R. Role of Type 2 Diabetes in Determining Retinal, Renal, and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Women With Previous Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2017, 40, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bomback, A.S.; Rekhtman, Y.; Whaley-Connell, A.T.; Kshirsagar, A.V.; Sowers, J.R.; Chen, S.C.; Li, S.; Chinnaiyan, K.M.; Bakris, G.L.; McCullough, P.A. Gestational diabetes mellitus alone in the absence of subsequent diabetes is associated with microalbuminuria: results from the Kidney Early Evaluation Program (KEEP). Diabetes Care. 2010, 33, 2586–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, K.; Nielsen, M.F.; Kallfa, E.; Dubietyte, G.; Lauszus, F.F. Metabolic syndrome in women with previous gestational diabetes. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 11558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, C.K.; Campbell, S.; Retnakaran, R. Gestational diabetes and the risk of cardiovascular disease in women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetologia. 2019, 62, 905–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, W.; Wang, Y.; Xiao, S.; Qiu, L.; Yu, Y.; Zhang, Z. Association of gestational diabetes mellitus with overall and type specific cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2022, 378, e070244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galderisi, M.; Cosyns, B.; Edvardsen, T.; Cardim, N.; Delgado, V.; Di Salvo, G.; Donal, E.; Sade, L.E.; Ernande, L.; Garbi, M.; et al. Standardization of adult transthoracic echocardiography reporting in agreement with recent chamber quantification, diastolic function, and heart valve disease recommendations: an expert consensus document of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2017, 18, 1301–1310. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Potter, E.; Marwick, T.H. Assessment of Left Ventricular Function by Echocardiography: The Case for Routinely Adding Global Longitudinal Strain to Ejection Fraction. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2018, 11, 260–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otterstad, J.E.; Froeland, G.; St John Sutton, M.; Holme, I. Accuracy and reproducibility of biplane two-dimensional echocardiographic measurements of left ventricular dimensions and function. Eur. Heart J. 1997, 18, 507–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marwick, T.H. Ejection Fraction Pros and Cons: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 72, 2360–2379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoit, B.D. Strain and strain rate echocardiography and coronary artery disease. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2011, 4, 179–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luis, S.A.; Chan, J.; Pellikka, P.A. Echocardiographic Assessment of Left Ventricular Systolic Function: An Overview of Contemporary Techniques, Including Speckle-Tracking Echocardiography. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2019, 94, 125–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voigt, J.U.; Cvijic, M. 2- and 3-Dimensional Myocardial Strain in Cardiac Health and Disease. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2019, 12, 1849–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meera, S.J.; Ando, T.; Pu, D.; Manjappa, S.; Taub, C.C. Dynamic left ventricular changes in patients with gestational diabetes: A speckle tracking echocardiography study. J. Clin. Ultrasound. 2017, 45, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buddeberg, B.S.; Sharma, R.; O'Driscoll, J.M.; Kaelin Agten, A.; Khalil, A.; Thilaganathan, B. Impact of gestational diabetes mellitus on maternal cardiac adaptation to pregnancy. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 56, 240–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Li, Z.; Li, Y.; Cai, Q.; Sun, L.; Zhu, W.; Ding, X.; Guo, D.; Qin, Y.; Lu, X. Reduced mechanical function of the left atrial predicts adverse outcome in pregnant women with clustering of metabolic risk factors. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2021, 21, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Company Calabuig, A.M.; Nunez, E.; Sánchez, A.; Nicolaides, K.H.; Charakida, M.; De Paco Matallana, C. Three-dimensional echocardiography and cardiac strain imaging in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 58, 278–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbone, E.; Wright, A.; Campos, R.V.; Anzoategui, S.; Nicolaides, K.H.; Charakida, M. Maternal cardiac function at 19-23 weeks' gestation in prediction of gestational diabetes mellitus. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 58, 77–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, W.; Li, Z.; Liu, W.; Zhao, P.; Che, G.; Wang, X.; Di, Z.; Tian, J.; Sun, L.; Wang, Z. Two-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography in assessing the subclinical myocardial dysfunction in patients with gestational diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc. Ultrasound. 2022, 20, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Peng, Y.; Liu, L.; Jiao, R.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, W.; Liu, Y.; Sun, C. Early Assessment of Cardiac Function by Echocardiography in Patients with Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Comput. Math. Methods Med. 2022, 2022, 6565109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anzoategui, S.; Gibbone, E.; Wright, A.; Nicolaides, K.H.; Charakida, M. Midgestation cardiovascular phenotype in women who develop gestational diabetes and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: comparative study. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 60, 207–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonaglioni, A.; Barlocci, E.; Adda, G.; Esposito, V.; Ferrulli, A.; Nicolosi, G.L.; Bianchi, S.; Lombardo, M.; Luzi, L. The impact of short-term hyperglycemia and obesity on biventricular and biatrial myocardial function assessed by speckle tracking echocardiography in a population of women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2022, 32, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appiah, D.; Schreiner, P.J.; Gunderson, E.P.; Konety, S.H.; Jacobs, D.R. Jr; Nwabuo, C.C.; Ebong, I.A.; Whitham, H.K.; Goff, D.C. Jr; Lima, J.A.; et al. Association of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus With Left Ventricular Structure and Function: The CARDIA Study. Diabetes Care. 2016, 39, 400–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, J.; Sanchez Sierra, A.; Abdel Azim, S.; Georgiopoulos, G.; Nicolaides, K.H.; Charakida, M. Maternal cardiac function in gestational diabetes mellitus at 35-36 weeks' gestation and 6 months postpartum. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 56, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benhalima, K.; Lens, K.; Bosteels, J.; Chantal, M. The Risk for Glucose Intolerance after Gestational Diabetes Mellitus since the Introduction of the IADPSG Criteria: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levey, A.S.; Bosch, J.P.; Lewis, J.B.; Greene, T.; Rogers, N.; Roth, D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Ann. Intern. Med. 1999, 130, 461–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, R.M.; Badano, L.P.; Mor-Avi, V.; Afilalo, J.; Armstrong, A.; Ernande, L.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Foster, E.; Goldstein, S.A.; Kuznetsova, T.; et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2015, 28, 1–39.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagueh, S.F.; Smiseth, O.A.; Appleton, C.P.; Byrd, B.F. 3rd; Dokainish, H.; Edvardsen, T.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Gillebert, T.C.; Klein, A.L.; Lancellotti, P.; et al. Recommendations for the Evaluation of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function by Echocardiography: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2016, 29, 277–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humbert, M.; Kovacs, G.; Hoeper, M.M.; Badagliacca, R.; Berger, R.M.F.; Brida, M.; Carlsen, J.; Coats, A.J.S.; Escribano-Subias, P.; Ferrari, P.; et al. 2022 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension. Eur. Respir. J. 2023, 61, 2200879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tello, K.; Wan, J.; Dalmer, A.; Vanderpool, R.; Ghofrani, H.A.; Naeije, R.; Roller, F.; Mohajerani, E.; Seeger, W.; Herberg, U.; et al. Validation of the Tricuspid Annular Plane Systolic Excursion/Systolic Pulmonary Artery Pressure Ratio for the Assessment of Right Ventricular-Arterial Coupling in Severe Pulmonary Hypertension. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2019, 12, e009047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, R.A.; Otto, C.M.; Bonow, R.O.; Carabello, B.A.; Erwin, J.P. 3rd; Fleisher, L.A.; Jneid, H.; Mack, M.J.; McLeod, C.J.; O'Gara, P.T.; et al. 2017 AHA/ACC Focused Update of the 2014 AHA/ACC Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2017, 135, e1159–e1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iacobellis, G.; Willens, H.J.; Barbaro, G.; Sharma, A.M. Threshold values of high-risk echocardiographic epicardial fat thickness. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008, 16, 887–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Sun, Z.; Li, J.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, X.; Liu, S.; Li, J.; Xu, C.; Hu, D.; Sun, Y. Pulse pressure and mean arterial pressure in relation to ischemic stroke among patients with uncontrolled hypertension in rural areas of China. Stroke. 2008, 39, 1932–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sattin, M.; Burhani, Z.; Jaidka, A.; Millington, S.J.; Arntfield, R.T. Stroke Volume Determination by Echocardiography. Chest. 2022, 161, 1598–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, L.K.; Sollers Iii, J.J.; Thayer, J.F. Resistance reconstructed estimation of total peripheral resistance from computationally derived cardiac output - biomed 2013. Biomed. Sci. Instrum. 2013, 49, 216–23. [Google Scholar]

- Redfield, M.M.; Jacobsen, S.J.; Borlaug, B.A.; Rodeheffer, R.J.; Kass, D.A. Age- and gender-related ventricular-vascular stiffening: a community-based study. Circulation. 2005, 112, 2254–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chantler, P.D.; Lakatta, E.G.; Najjar, S.S. Arterial-ventricular coupling: mechanistic insights into cardiovascular performance at rest and during exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985). 2008, 105, 1342–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, J.U.; Pedrizzetti, G.; Lysyansky, P.; Marwick, T.H.; Houle, H.; Baumann, R.; Pedri, S.; Ito, Y.; Abe, Y.; Metz, S.; et al. Definitions for a common standard for 2D speckle tracking echocardiography: consensus document of the EACVI/ASE/Industry Task Force to standardize deformation imaging. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2015, 16, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badano, L.P. , Muraru, D., Parati, G., Haugaa, K., Voigt, J.U. How to do right ventricular strain. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2020, 21, 825–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voigt, J.U.; Mălăescu, G.G.; Haugaa, K.; Badano, L. How to do LA strain. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2020, 21, 715–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonaglioni, A.; Vincenti, A.; Baravelli, M.; Rigamonti, E.; Tagliabue, E.; Bassi, P.; Nicolosi, G.L.; Anzà, C.; Lombardo, M. Prognostic value of global left atrial peak strain in patients with acute ischemic stroke and no evidence of atrial fibrillation. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2019, 35, 603–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yingchoncharoen, T.; Agarwal, S.; Popović, Z.B.; Marwick, T.H. Normal ranges of left ventricular strain: a meta-analysis. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2013, 26, 185–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraru, D.; Onciul, S.; Peluso, D.; Soriani, N.; Cucchini, U.; Aruta, P.; Romeo, G.; Cavalli, G.; Iliceto, S.; Badano, L.P. Sex- and Method-Specific Reference Values for Right Ventricular Strain by 2-Dimensional Speckle-Tracking Echocardiography. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2016, 9, e003866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathan, F.; D'Elia, N.; Nolan, M.T.; Marwick, T.H.; Negishi, K. Normal Ranges of Left Atrial Strain by Speckle-Tracking Echocardiography: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2017, 30, 59–70.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krittanawong, C.; Maitra, N.S.; Hassan Virk, H.U.; Farrell, A.; Hamzeh, I.; Arya, B.; Pressman, G.S.; Wang, Z.; Marwick, T.H. Normal Ranges of Right Atrial Strain: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2023, 16, 282–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, J.H.; Korcarz, C.E.; Hurst, R.T.; Lonn, E.; Kendall, C.B.; Mohler, E.R.; Najjar, S.S.; Rembold, C.M.; Post, W.S.; American Society of Echocardiography Carotid Intima-Media Thickness Task Force. Use of carotid ultrasound to identify subclinical vascular disease and evaluate cardiovascular disease risk: a consensus statement from the American Society of Echocardiography Carotid Intima-Media Thickness Task Force. Endorsed by the Society for Vascular Medicine. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2008, 21, 93–111, quiz 189-90. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz, M.W.; von Kegler, S.; Steinmetz, H.; Markus, H.S.; Sitzer, M. Carotid intima-media thickening indicates a higher vascular risk across a wide age range: prospective data from the Carotid Atherosclerosis Progression Study (CAPS). Stroke. 2006, 37, 87–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Randrianarisoa, E.; Rietig, R.; Jacob, S.; Blumenstock, G.; Haering, H.U.; Rittig, K.; Balletshofer, B. Normal values for intima-media thickness of the common carotid artery--an update following a novel risk factor profiling. Vasa. 2015, 44, 444–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, S.D.; Umans, J.G.; Ratner, R. Gestational diabetes: implications for cardiovascular health. Curr. Diab. Rep. 2012, 12, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunderson, E.P.; Chiang, V.; Pletcher, M.J.; Jacobs, D.R.; Quesenberry, C.P.; Sidney, S.; Lewis, C.E. History of gestational diabetes mellitus and future risk of atherosclerosis in mid-life: the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2014, 3, e000490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKenzie-Sampson, S.; Paradis, G.; Healy-Profitós, J.; St-Pierre, F.; Auger, N. Gestational diabetes and risk of cardiovascular disease up to 25 years after pregnancy: a retrospective cohort study. Acta Diabetol. 2018, 55, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.J.; Kim, H.L.; Lim, W.H.; Seo, J.B.; Kim, S.H.; Zo, J.H.; Kim, M.A. Subclinical alterations in left ventricular structure and function according to obesity and metabolic health status. PLoS One. 2019, 14, e0222118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Liang, J.; Zheng, S.; He, A.; Chen, C.; Zhao, X.; Hua, M.; Xu, J.; Zheng, Z.; Liu, M. Combined associations of obesity and metabolic health with subclinical left ventricular dysfunctions: Danyang study. ESC Heart Fail. 2021, 8, 3058–3069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitarelli, A.; Martino, F.; Capotosto, L.; Martino, E.; Colantoni, C.; Ashurov, R.; Ricci, S.; Conde, Y.; Maramao, F.; Vitarelli, M.; et al. Early myocardial deformation changes in hypercholesterolemic and obese children and adolescents: a 2D and 3D speckle tracking echocardiography study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014, 93, e71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.A.; Park, S.M.; Kim, M.N.; Shim, W.J. Assessment of Left Ventricular Function by Layer-Specific Strain and Its Relationship to Structural Remodelling in Patients With Hypertension. Can. J. Cardiol. 2016, 32, 211–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmala, W.; Sanders, P.; Marwick, T.H. Subclinical Myocardial Impairment in Metabolic Diseases. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2017, 10, 692–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.; Patel, K.V.; Vaduganathan, M.; Sarma, S.; Haykowsky, M.J.; Berry, J.D.; Lavie, C.J. Physical Activity, Fitness, and Obesity in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. JACC Heart Fail. 2018, 6, 975–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazio, S.; Mercurio, V.; Fazio, V.; Ruvolo, A.; Affuso, F. Insulin Resistance/Hyperinsulinemia, Neglected Risk Factor for the Development and Worsening of Heart Failure with Preserved Ejection Fraction. Biomedicines. 2024, 12, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpe, L.; Cuccuru, I.; Lencioni, C.; Napoli, V.; Ghio, A.; Fotino, C.; Bertolotto, A.; Penno, G.; Benzi, L.; Del Prato, S.; et al. Early subclinical atherosclerosis in women with previous gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2008, 31, e32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freire, C.M.; Barbosa, F.B.; de Almeida, M.C.; Miranda, P.A.; Barbosa, M.M.; Nogueira, A.I.; Guimarães, M.M.; Nunes Mdo, C.; Ribeiro-Oliveira, A. Jr. Previous gestational diabetes is independently associated with increased carotid intima-media thickness, similarly to metabolic syndrome - a case control study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2012, 11, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fakhrzadeh, H.; Alatab, S.; Sharifi, F.; Mirarefein, M.; Badamchizadeh, Z.; Ghaderpanahi, M.; Hashemi Taheri, A.P.; Larijani, B. Carotid intima media thickness, brachial flow mediated dilation and previous history of gestational diabetes mellitus. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2012, 38, 1057–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karoli, R.; Siddiqi, Z.; Fatima, J.; Shukla, V.; Mishra, P.P.; Khan, F.A. Assessment of noninvasive risk markers of subclinical atherosclerosis in premenopausal women with previous history of gestational diabetes mellitus. Heart Views. 2015, 16, 13–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frigerio, B.; Werba, J.P.; Amato, M.; Ravani, A.; Sansaro, D.; Coggi, D.; Vigo, L.; Tremoli, E.; Baldassarre, D. Traditional Risk Factors are Causally Related to Carotid Intima-Media Thickness Progression: Inferences from Observational Cohort Studies and Interventional Trials. Curr. Pharm Des. 2020, 26, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornev, M.; Caglayan, H.A.; Kudryavtsev, A.V.; Malyutina, S.; Ryabikov, A.; Schirmer, H.; Rösner, A. Influence of hypertension on systolic and diastolic left ventricular function including segmental strain and strain rate. Echocardiography. 2023, 40, 623–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonaglioni, A.; Esposito, V.; Caruso, C.; Nicolosi, G.L.; Bianchi, S.; Lombardo, M.; Gensini, G.F.; Ambrosio, G. Chest conformation spuriously influences strain parameters of myocardial contractile function in healthy pregnant women. J. Cardiovasc. Med. (Hagerstown). 2021, 22, 767–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonaglioni, A.; Ferrulli, A.; Nicolosi, G.L.; Lombardo, M.; Luzi, L. The Influence of Anthropometrics on Cardiac Mechanics in Healthy Women With Opposite Obesity Phenotypes (Android vs Gynoid). Cureus. 2024, 16, e51698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ACOG Practice Bulletin, No. 190: Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Obstet. Gynecol. 2018, 131, e49–e64. [Google Scholar]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. 15. Management of Diabetes in Pregnancy: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2022. Diabetes Care. 2022, 45, S232–S243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sitzberger, C.; Oberhoffer-Fritz, R.; Meyle, K.; Wagner, M.; Lienert, N.; Graupner, O.; Ensenauer, R.; Lobmaier, S.M.; Wacker-Gußmann, A. Gestational Diabetes: Physical Activity Before Pregnancy and Its Influence on the Cardiovascular System. Front. Pediatr. 2020, 8, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Ascenzo, F.; Agostoni, P.; Abbate, A.; Castagno, D.; Lipinski, M.J.; Vetrovec, G.W.; Frati, G.; Presutti, D.G.; Quadri, G.; Moretti, C.; et al. Atherosclerotic coronary plaque regression and the risk of adverse cardiovascular events: a meta-regression of randomized clinical trials. Atherosclerosis. 2013, 226, 178–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negishi, T.; Negishi, K.; Thavendiranathan, P.; Cho, G.Y.; Popescu, B.A.; Vinereanu, D.; Kurosawa, K.; Penicka, M.; Marwick, T.H.; SUCCOUR Investigators. Effect of Experience and Training on the Concordance and Precision of Strain Measurements. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2017, 5, 518–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rösner, A.; Barbosa, D.; Aarsæther, E.; Kjønås, D.; Schirmer, H.; D'hooge, J. The influence of frame rate on two-dimensional speckle-tracking strain measurements: a study on silico-simulated models and images recorded in patients. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2015, 16, 1137–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mirea, O.; Pagourelias, E.D.; Duchenne, J.; Bogaert, J.; Thomas, J.D.; Badano, L.P.; Voigt, J.U.; EACVI-ASE-Industry Standardization Task Force. Intervendor Differences in the Accuracy of Detecting Regional Functional Abnormalities: A Report From the EACVI-ASE Strain Standardization Task Force. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2018, 11, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonaglioni, A.; Nicolosi, G.L.; Granato, A.; Bonanomi, A.; Rigamonti, E.; Lombardo, M. Influence of chest wall conformation on reproducibility of main echocardiographic indices of left ventricular systolic function. Minerva Cardiol. Angiol. 2024, 72, 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| GDM women (n = 32) | Controls (n = 30) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics, anthropometrics and obstetrics | |||

| Age (yrs) | 34.1 ± 6.5 | 35.8 ± 5.0 | 0.26 |

| Caucasian ethnicity (%) | 16 (50.0) | 19 (63.3) | 0.29 |

| Third trimester BSA (m2) | 1.86 ± 0.19 | 1.77 ± 0.15 | 0.04 |

| Third trimester BMI (Kg/m2) | 29.5 ± 6.0 | 26.6 ± 3.8 | 0.03 |

| Obesity (BMI ≥30 Kg/m2) (%) | 14 (43.7) | 5 (16.7) | 0.02 |

| Pluriparous (%) | 16 (50.0) | 13 (43.3) | 0.59 |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 36.2 ± 1.8 | 36.6 ± 1.5 | 0.35 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |||

| Smoking (%) | 5 (15.6) | 6 (20.0) | 0.65 |

| Dyslipidemia (%) | 16 (50.0) | 5 (16.7) | 0.005 |

| Family history of diabetes (%) | 16 (50.0) | 3 (10.0) | <0.001 |

| Hemodynamics | |||

| HR (bpm) | 86.8 ± 14.9 | 88.3 ± 8.8 | 0.63 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 108.8 ± 11.3 | 92.5 ± 8.6 | <0.001 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 68.0 ± 7.0 | 59.3 ± 4.5 | <0.001 |

| MAP (mmHg) | 81.6 ± 7.1 | 70.4 ± 5.5 | <0.001 |

| Third trimester blood tests and glycometabolic parameters | |||

| Serum hemoglobin (g/dl) | 11.7 ± 1.1 | 11.3 ± 1.5 | 0.23 |

| RDW (%) | 15.3 ± 2.4 | 13.8 ± 2.1 | 0.01 |

| NLR | 4.4 ± 1.7 | 2.1 ± 0.5 | <0.001 |

| eGFR (ml/min/m2) | 128.3 ± 12.6 | 133.6 ± 28.9 | 0.35 |

| Serum total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 253.75 ± 36.6 | 171.0 ± 11.2 | <0.001 |

| Serum uric acid (mg/dl) | 4.9 ± 1.1 | 4.2 ± 0.6 | 0.003 |

| Gestational age at diagnosis of GDM (weeks) | 24.0 ± 5.8 | / | / |

| Glycosylated hemoglobin (mmol/mol) | 34.7 ± 4.1 | / | / |

| Antidiabetic treatment | |||

| Diet (%) | 18 (56.2) | / | / |

| Insulin (%) | 14 (43.8) | / | / |

| Delivery parameters | |||

| Gestational week at delivery (weeks) | 38.4 ± 0.9 | 39.1 ± 1.4 | 0.02 |

| PROM (%) | 3 (9.4) | 1 (3.3) | 0.33 |

| Cesarean delivery (%) | 8 (25.0) | 10 (33.3) | 0.47 |

| PPH (%) | 2 (6.2) | 3 (10.0) | 0.59 |

| Neonatal birth weight (g) | 3361.2 ± 292.6 | 3381.2 ± 480.5 | 0.84 |

| pGDM women (n = 32) | Controls (n = 30) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics and anthropometrics | |||

| Age (yrs) | 39.1 ± 6.5 | 40.8 ± 5.0 | 0.26 |

| Caucasian ethnicity (%) | 16 (50.0) | 19 (63.3) | 0.29 |

| BSA (m2) | 1.76 ± 0.17 | 1.66 ± 0.14 | 0.01 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 27.9 ± 4.5 | 22.2 ± 2.8 | <0.001 |

| Obesity (BMI ≥30 Kg/m2) (%) | 11 (34.4) | 3 (10.0) | 0.02 |

| WHR | 0.90 ± 0.16 | 0.78 ± 0.15 | 0.003 |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |||

| Smoking (%) | 5 (15.6) | 6 (20.0) | 0.65 |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus (%) | 10 (31.2) | 1 (3.3) | 0.004 |

| Dyslipidemia (%) | 10 (31.2) | 2 (6.7) | 0.01 |

| Blood pressure parameters | |||

| SBP (mmHg) | 122.4 ± 13.2 | 113.2 ± 11.1 | 0.004 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 76.2 ± 9.1 | 70.4 ± 9.4 | 0.02 |

| MBP (mmHg) | 91.6 ± 9.6 | 84.6 ± 8.9 | 0.04 |

| BP ≥140/90 mmHg at clinical visit (%) | 10 (31.2) | 2 (6.7) | 0.01 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypothyroidism (%) | 3 (9.4) | 8 (26.7) | 0.07 |

| Current medical treatment | |||

| Oral hypoglycemic agents (%) | 4 (12.5) | 1 (3.3) | 0.18 |

| Antihypertensive drugs (%) | 4 (12.5) | 1 (3.3) | 0.18 |

| Statins (%) | 2 (6.2) | 1 (3.3) | 0.59 |

| pGDM women (n = 32) | Controls (n = 30) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yrs postpartum | 4.0 ± 1.9 | 4.1 ± 2.1 | 0.84 |

| Conventional echoDoppler parameters | |||

| IVS (mm) | 9.3 ± 1.8 | 7.6 ± 1.2 | <0.001 |

| LV-PW (mm) | 7.6 ± 0.9 | 6.6 ± 1.0 | <0.001 |

| LV-EDD (mm) | 44.0 ± 3.4 | 44.4 ± 2.7 | 0.61 |

| RWT | 0.34 ± 0.05 | 0.30 ± 0.05 | 0.003 |

| LVMi (g/m2) | 66.7 ± 10.9 | 57.7 ± 9.7 | 0.001 |

| Normal LV geometric pattern (%) | 29 (90.6) | 29 (96.7) | 0.33 |

| LV concentric remodeling (%) | 3 (9.4) | 1 (3.3) | 0.33 |

| LVEDVi (ml/m2) | 34.9 ± 6.15 | 35.3 ± 5.6 | 0.79 |

| LVESVi (ml/m2) | 11.8 ± 2.6 | 11.9 ± 2.5 | 0.88 |

| LVEF (%) | 65.8 ± 3.7 | 65.9 ± 4.8 | 0.93 |

| E/A ratio | 1.24 ± 0.31 | 1.34 ± 0.31 | 0.21 |

| E/average e’ ratio | 9.25 ± 3.01 | 5.14 ± 1.34 | <0.001 |

| LA A-P diameter (mm) | 36.2 ± 3.3 | 33.6 ± 4.1 | 0.008 |

| LAVi (ml/m2) | 29.0 ± 7.3 | 27.4 ± 7.3 | 0.39 |

| Mild MR (n, %) | 7 (21.9) | 9 (30.0) | 0.46 |

| Mild TR (n, %) | 8 (25) | 10 (33.3) | 0.47 |

| RVIT (mm) | 29.7 ± 2.6 | 29.5 ± 3.0 | 0.78 |

| TAPSE (mm) | 23.9 ± 3.7 | 26.4 ± 3.6 | 0.009 |

| IVC (mm) | 16.6 ± 3.6 | 17.0 ± 3.9 | 0.68 |

| sPAP (mmHg) | 25.0 ± 4.9 | 22.8 ± 2.2 | 0.03 |

| TAPSE/sPAP ratio | 0.97 ± 0.19 | 1.17 ± 0.18 | <0.001 |

| Aortic root (mm) | 29.0 ± 3.4 | 29.1 ± 2.6 | 0.89 |

| Ascending aorta (mm) | 28.9 ± 3.4 | 28.8 ± 3.1 | 0.90 |

| End-systolic EAT (mm) | 6.7 ± 1.3 | 4.1 ± 1.4 | <0.001 |

| Hemodynamic indices | |||

| HR (bpm) | 77.6 ± 11.1 | 75.5 ± 11.9 | 0.46 |

| ESP (mmHg) | 110.2 ± 11.9 | 101.9 ± 10.0 | 0.004 |

| SVi (ml/m2) | 32.2 ± 6.1 | 39.4 ± 9.1 | <0.001 |

| COi (l/min/m2) | 2.5 ± 0.4 | 2.9 ± 0.7 | 0.007 |

| TPRi (dyne.sec/cm5)/m2 | 3060.7 ± 669.6 | 2427.5 ± 620.6 | <0.001 |

| EaI (mmHg/ml/m2) | 1.24 ± 0.48 | 1.00 ± 0.26 | 0.02 |

| EesI (mmHg/ml/m2) | 3.25 ± 1.07 | 3.28 ± 0.89 | 0.91 |

| EaI/EesI ratio | 0.39 ± 0.10 | 0.31 ± 0.09 | 0.001 |

| Carotid parameters | |||

| Av. CCA-EDD (mm) | 6.76 ± 0.46 | 6.64 ± 0.44 | 0.29 |

| Av. CCA-IMT (mm) | 0.91 ± 0.26 | 0.62 ± 0.19 | <0.001 |

| Av. CCA-IMT ≥0.7 mm (%) | 25 (78.1) | 7 (23.3) | <0.001 |

| Av. CCA-RWT | 0.27 ± 0.08 | 0.19 ± 0.06 | <0.001 |

| Av. CCA-CSA (mm2) | 22.0 ± 7.4 | 14.2 ± 4.9 | <0.001 |

| STE VARIABLES | pGDM women (n = 32) | Controls (n = 30) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| LV-GLS (%) | 19.5 ± 2.6 | 22.3 ± 2.3 | <0.001 |

| LV-GLSR (s-1) | 1.1 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | <0.001 |

| LV-GCS (%) | 22.8 ± 4.48 | 26.7 ± 4.4 | 0.001 |

| LV-GCSR (s-1) | 1.6 ± 0.3 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 0.13 |

| LAScd (%) | 29.8 ± 8.9 | 36.3 ± 7.7 | 0.003 |

| LASct (%) | 7.3 ± 4.2 | 9.5 ± 4.1 | 0.04 |

| LASr (%) | 37.1 ± 9.2 | 45.7 ± 8,0 | <0.001 |

| LASr/E/e’ | 4.4 ± 1.8 | 9.5 ± 3.2 | <0.001 |

| LA-GSR (s-1) | 1.9 ± 0.5 | 2.3 ± 0.5 | 0.002 |

| LA-GSRE (s-1) | 2.4 ± 0.7 | 3.1 ± 0.8 | <0.001 |

| LA-GSRL (s-1) | 2.5 ± 0.6 | 2.8 ± 0.5 | 0.04 |

| RV-FWLS (%) | 19.9 ± 3.8 | 22.0 ± 3.5 | 0.03 |

| RV-GLS (%) | 18.8 ± 3.9 | 20.9 ± 3.4 | 0.03 |

| RV-GLSR (s-1) | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | <0.001 |

| RAScd (%) | 26.3 ± 11.7 | 34.6 ± 10.1 | 0.004 |

| RASct (%) | 6.1 ± 4.46 | 7.5 ± 5.4 | 0.27 |

| RASr (%) | 32.4 ± 11.0 | 42.1 ± 9.9 | <0.001 |

| RA-GSR (s-1) | 2.0 ± 0.9 | 2.5 ± 0.6 | 0.01 |

| RA-GSRE (s-1) | 1.9 ± 0.6 | 2.3 ± 0.7 | 0.02 |

| RA-GSRL (s-1) | 2.0 ± 0.6 | 2.5 ± 0.8 | 0.007 |

| PERCENTAGE OF WOMEN WITH IMPAIRED STE PARAMETERS IN COMPARISON TO THE ACCEPTED NORMAL VALUES | |||

| LV-GLS <20% (%) | 20 (62.5) | 4 (13.3) | <0.001 |

| LV-GCS <23.3% (%) | 16 (50.0) | 7 (23.3) | 0.03 |

| LASr <39% (%) | 18 (56.3) | 5 (16.7) | 0.001 |

| RV-GLS <20% (%) | 19 (59.4) | 7 (23.3) | 0.004 |

| RASr <35% (%) | 20 (62.5) | 8 (26.7) | 0.005 |

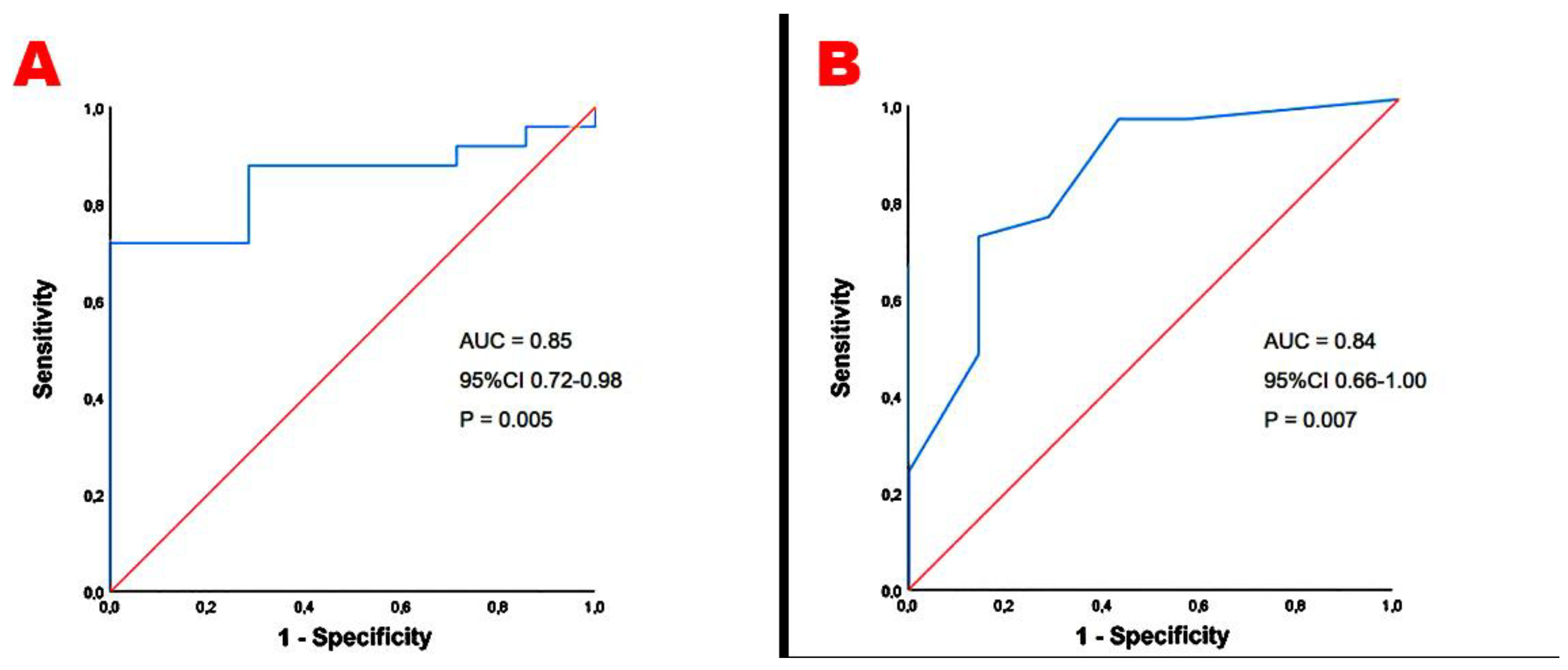

| UNIVARIATE LOGISTIC REGRESSION ANALYSIS |

MULTIVARIATE LOGISTIC REGRESSION ANALYSIS |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | OR | 95% CI | p-Value | OR | 95% CI | p-Value |

| Third trimester age (yrs) | 1.08 | 0.96-1.21 | 0.21 | |||

| Third trimester BMI (Kg/m2) | 1.87 | 1.24-2.83 | 0.003 | 1.88 | 1.19.2.98 | 0.03 |

| Third trimester glycosylated hemoglobin (mmol/mol) | 2.30 | 1.35-3.94 | 0.002 | 2.34 | 1.08-5.04 | 0.02 |

| Third trimester NLR | 1.89 | 1.08-3.33 | 0.03 | 1.69 | 0.64-4.45 | 0.28 |

| Third trimester MAP | 1.01 | 0.94-1.09 | 0.77 | |||

| UNIVARIATE LOGISTIC REGRESSION ANALYSIS |

MULTIVARIATE LOGISTIC REGRESSION ANALYSIS |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VARIABLES | OR | 95% CI | p-Value | OR | 95% CI | p-Value |

| Third trimester age (yrs) | 1.37 | 1.09-1.70 | 0.005 | 1.06 | 0.94-1.19 | 0.32 |

| Third trimester BMI (Kg/m2) | 1.40 | 1.09-1.82 | 0.01 | 1.35 | 1.02-1.79 | 0.03 |

| Third trimester glycosylated hemoglobin (mmol/mol) | 1.37 | 1.08-1.74 | 0.009 | 1.37 | 1.00-1.88 | 0.02 |

| Third trimester NLR | 1.34 | 0.81-2.22 | 0.25 | |||

| Third trimester MAP | 1.06 | 0.95-1.17 | 0.29 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).