Submitted:

02 January 2025

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

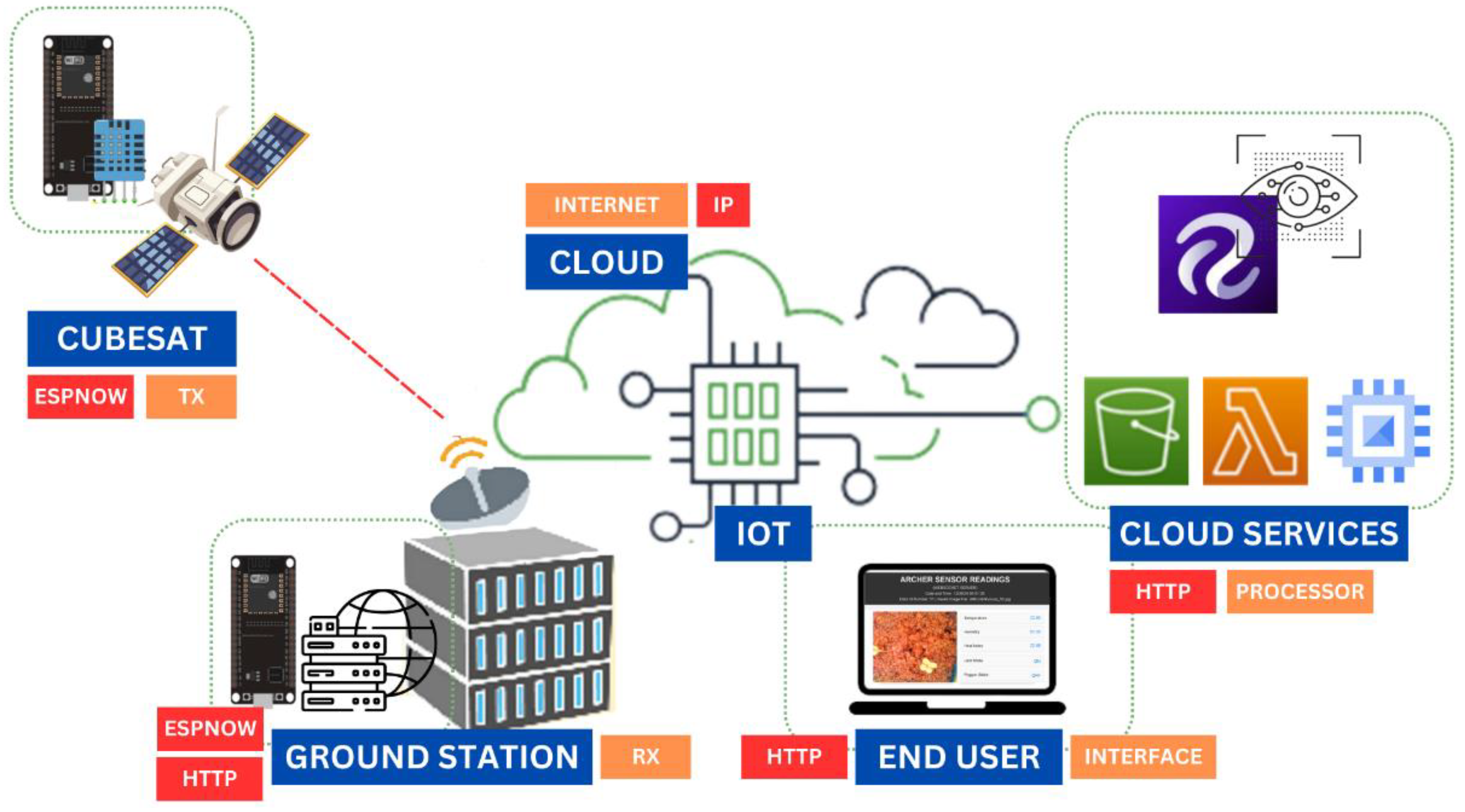

- Development of a webserver as a monitoring hub

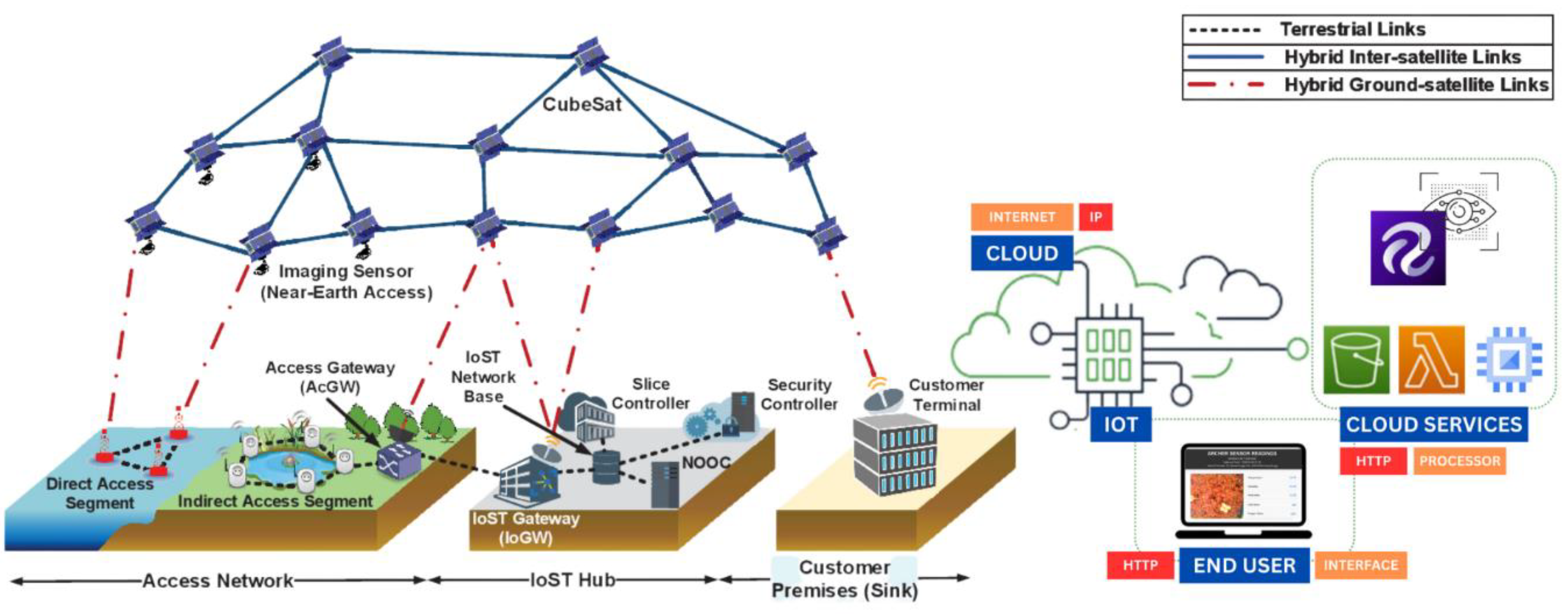

- Establishment of edge-to-cloud communications using AWS IoT Core

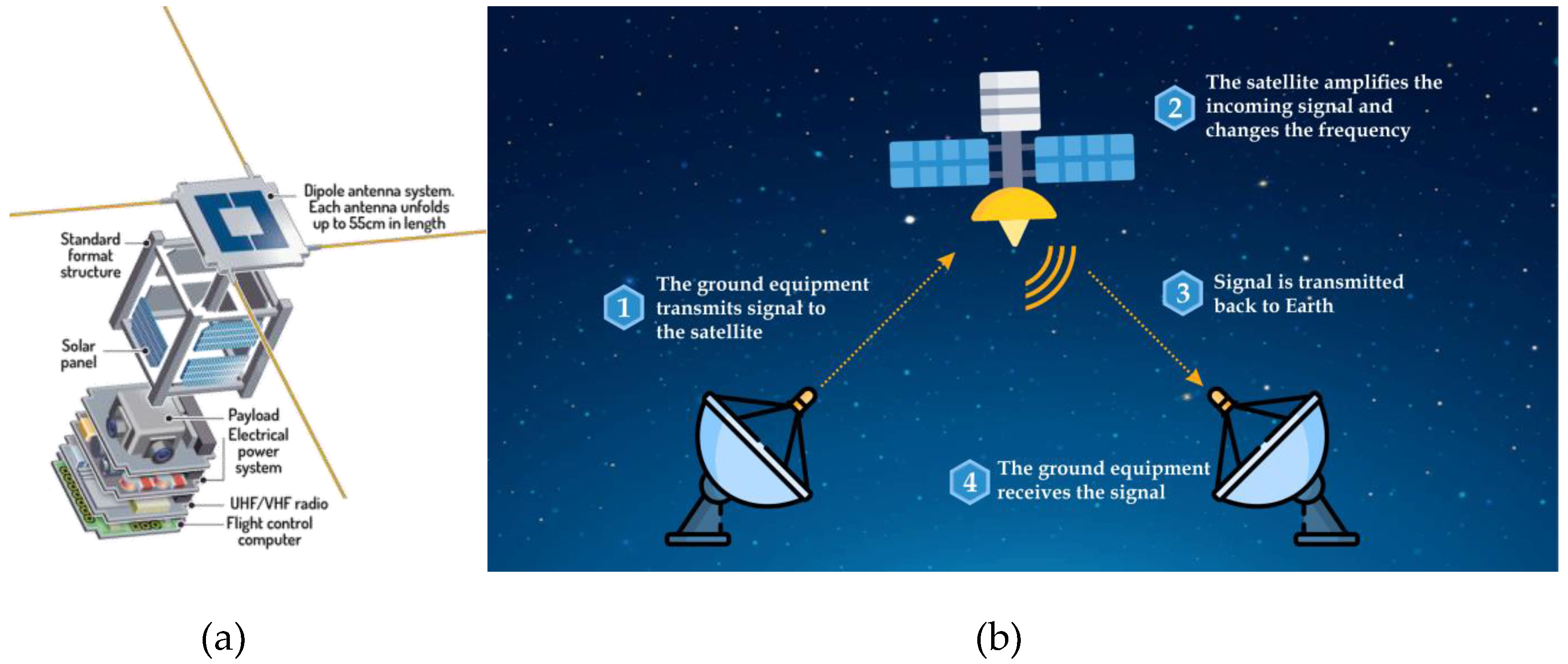

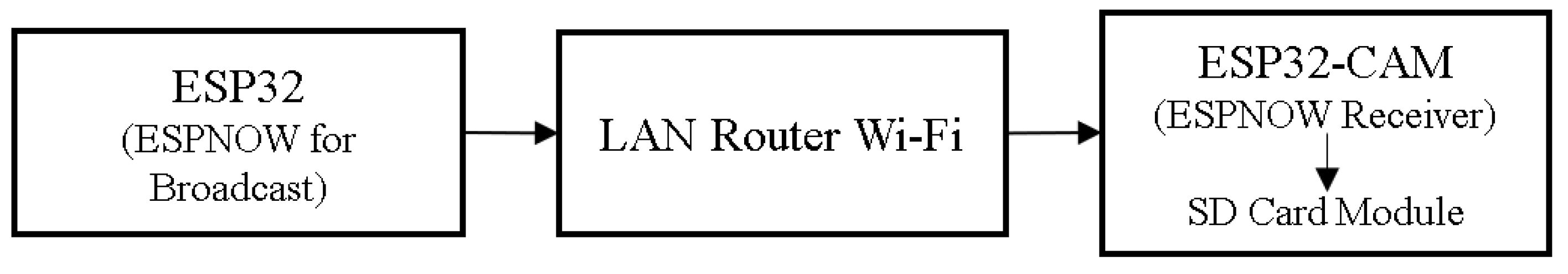

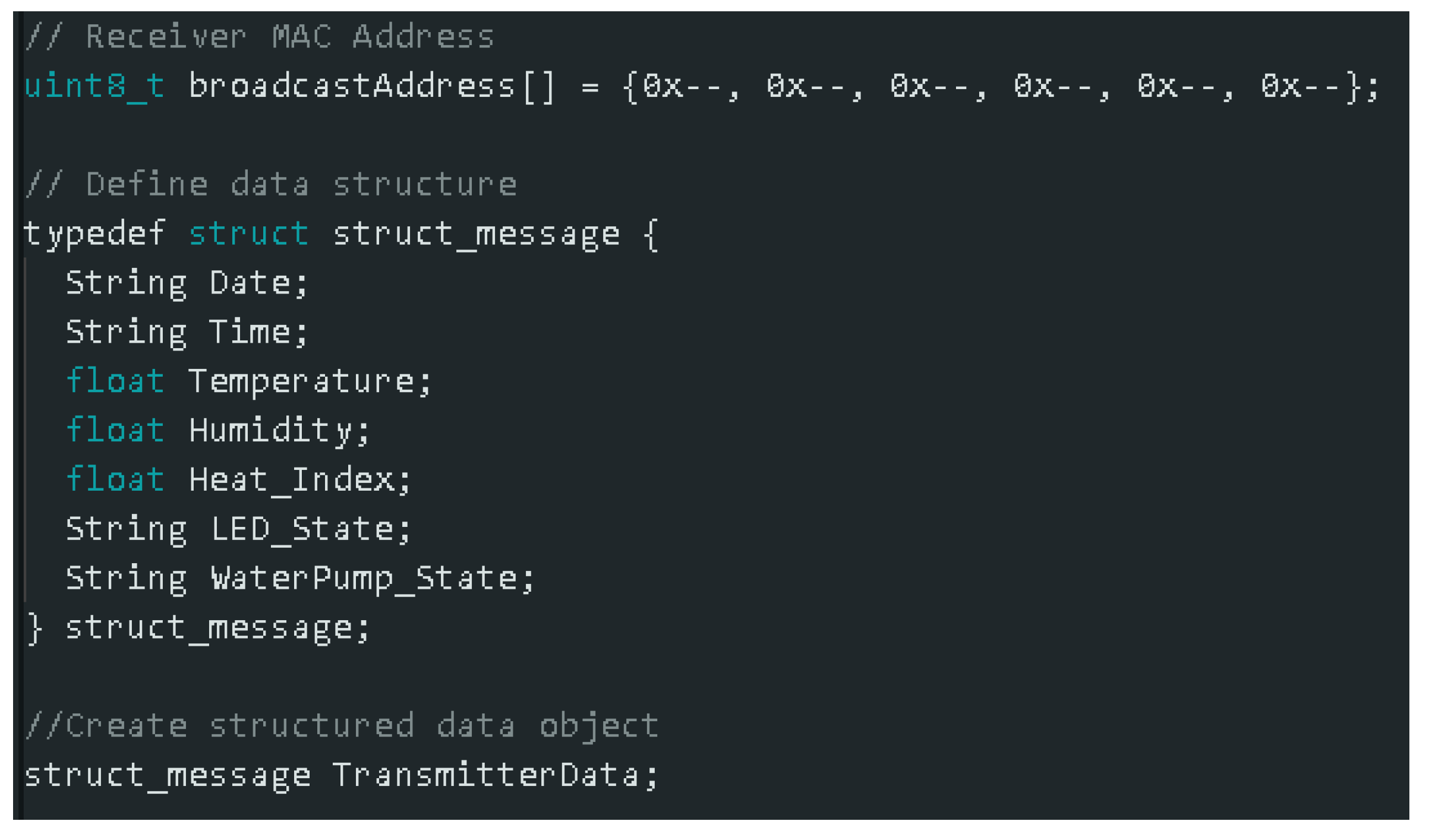

- Data collection and transmission from 2U CubeSat using the ESP-NOW technology

- Development and deployment of a machine vision model for germination detection using Roboflow

1.1. Review of Related Studies

1.2. Proposed Framework for Space Farming Data Analysis

2. Materials and Methods

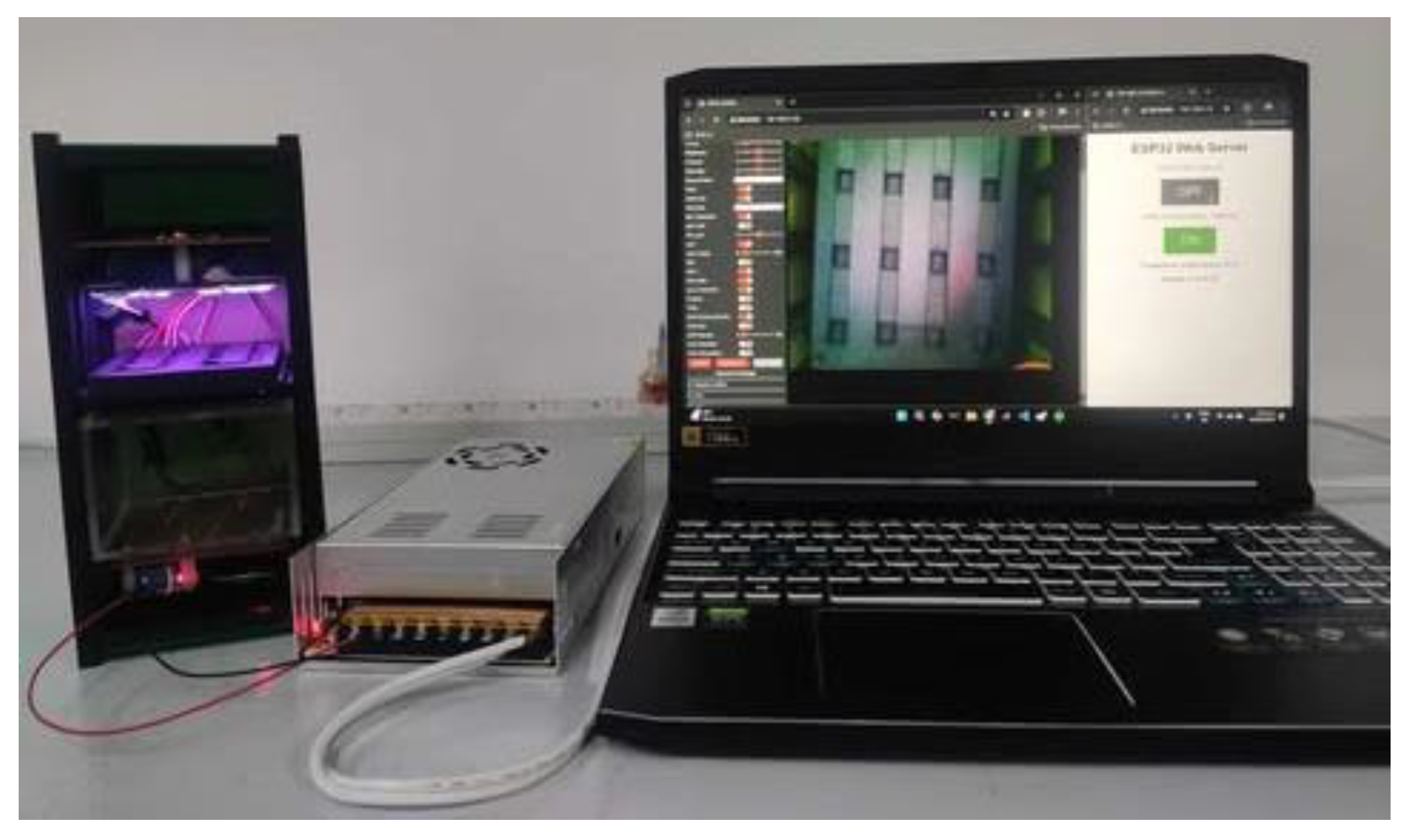

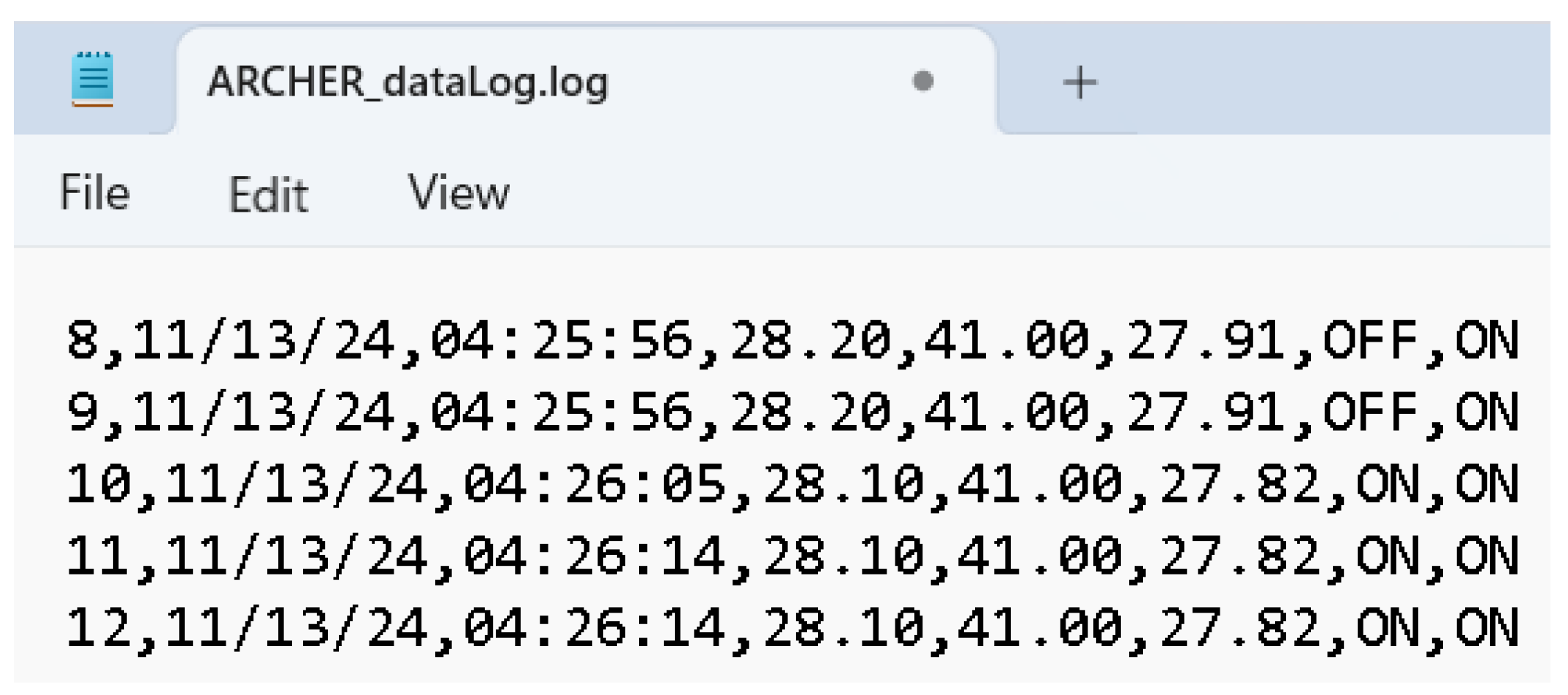

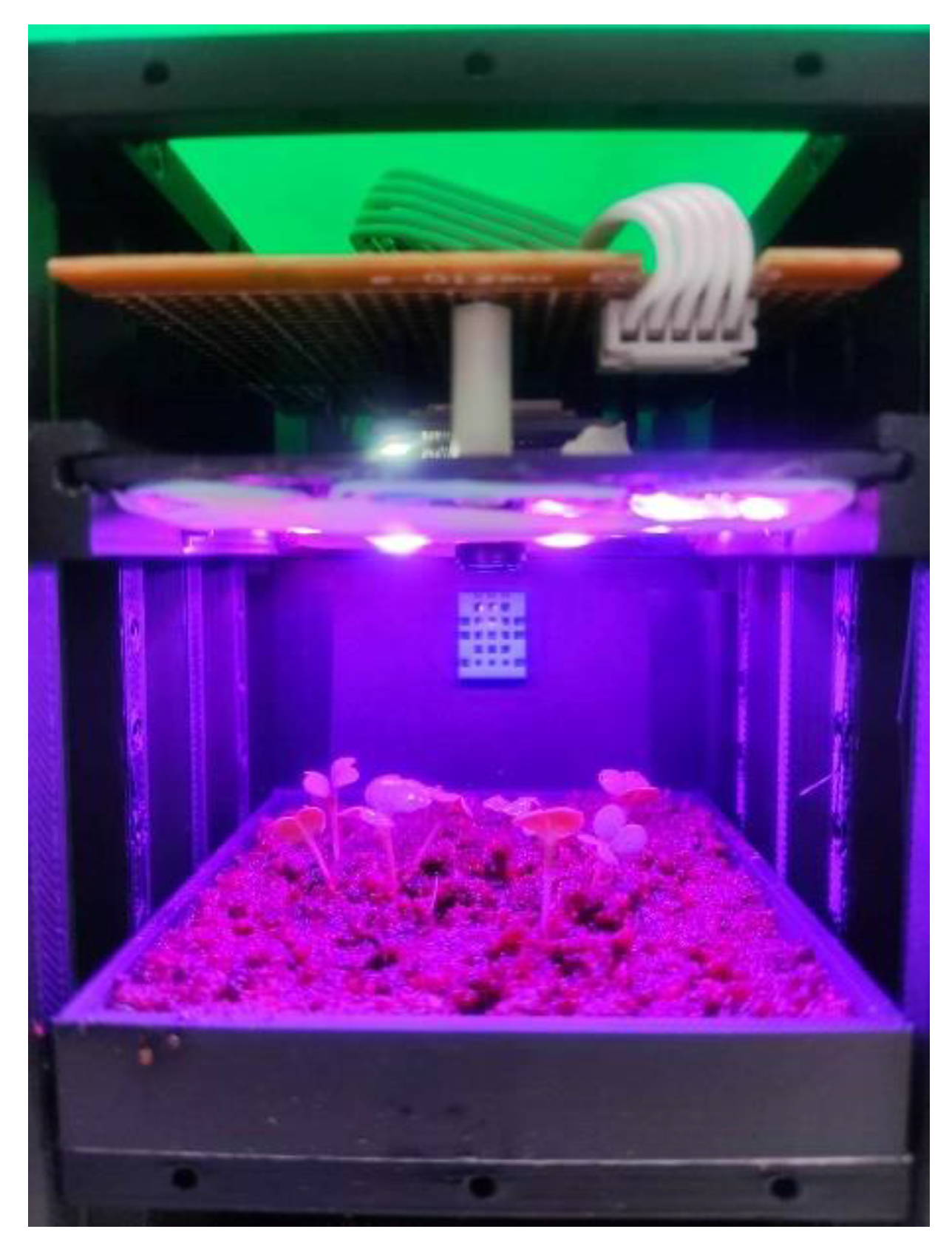

2.1. Data Collection Using the ESP32-Based System Simulation

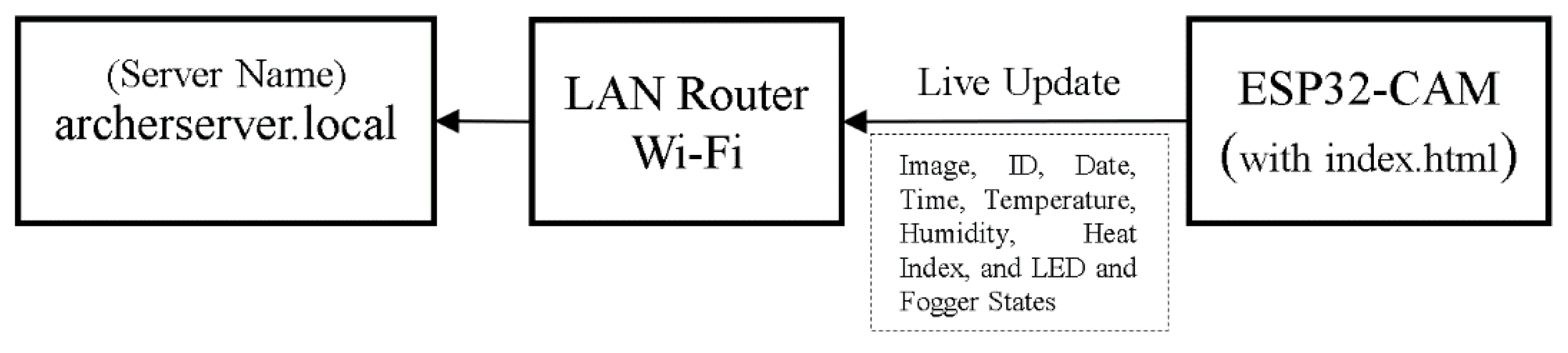

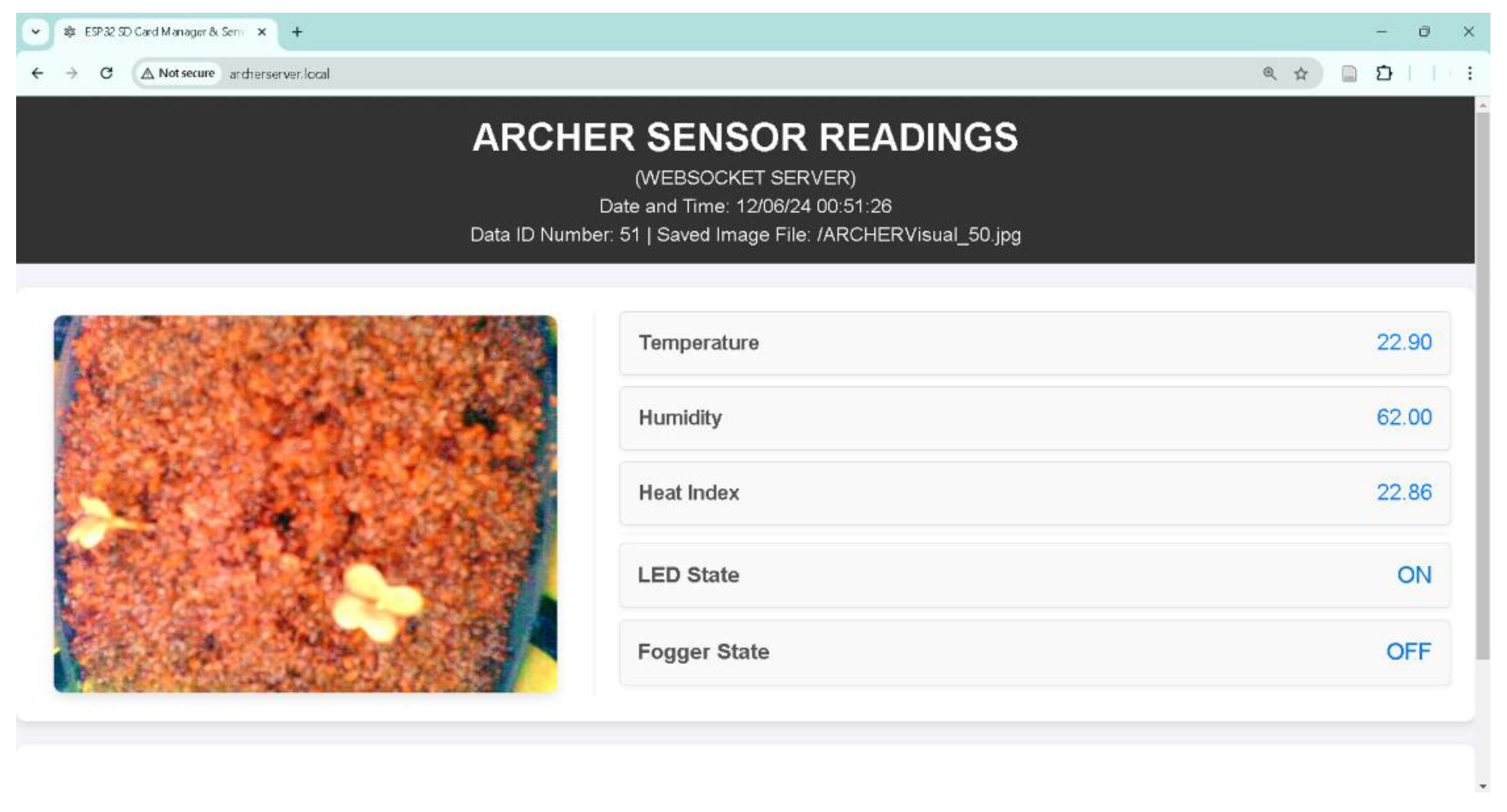

2.2. Development of the Asynchronous Local Webserver on ESP32

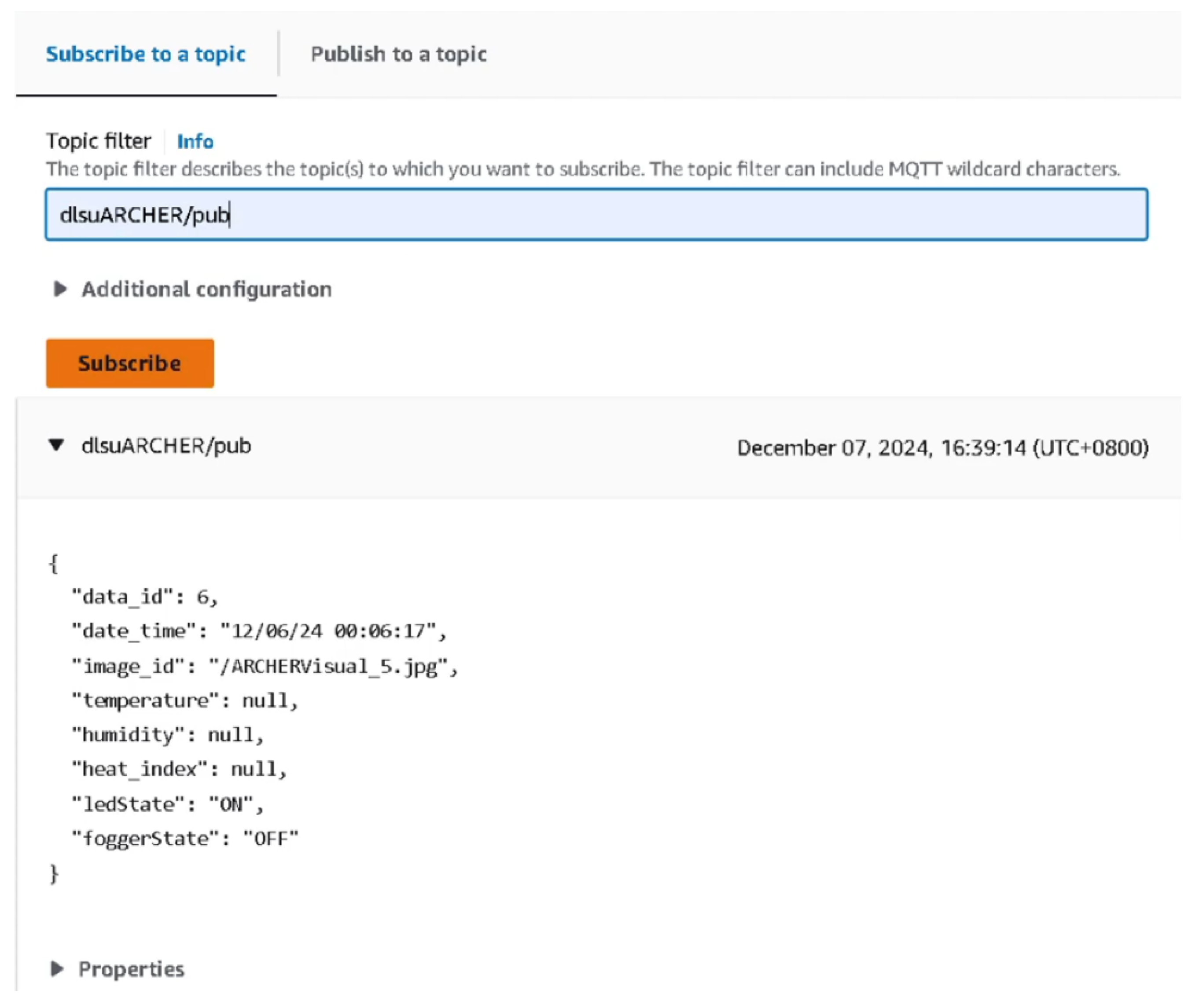

2.3. Establishment of Data Monitoring and Saving using AWS IoT

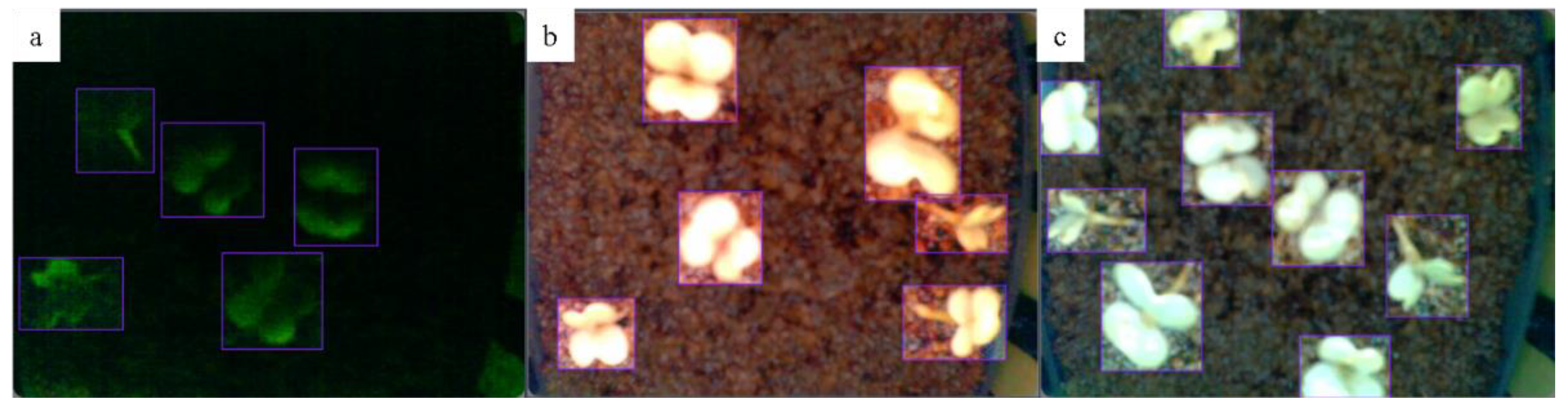

2.4. Development of Roboflow Model for Germination Detection

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Local Webserver Based on ESP32

3.2. Secure Remote Monitoring Using AWS IoT

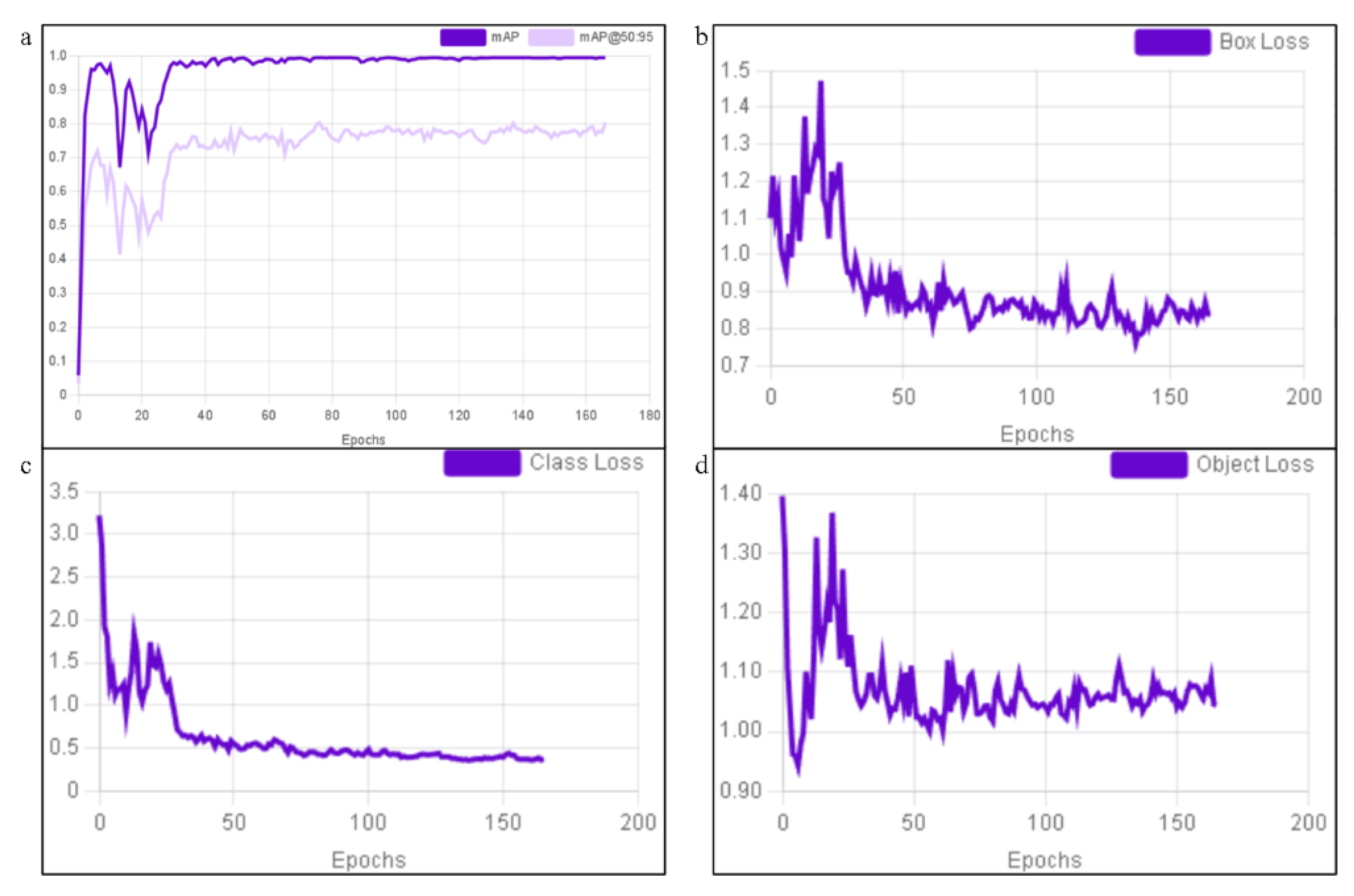

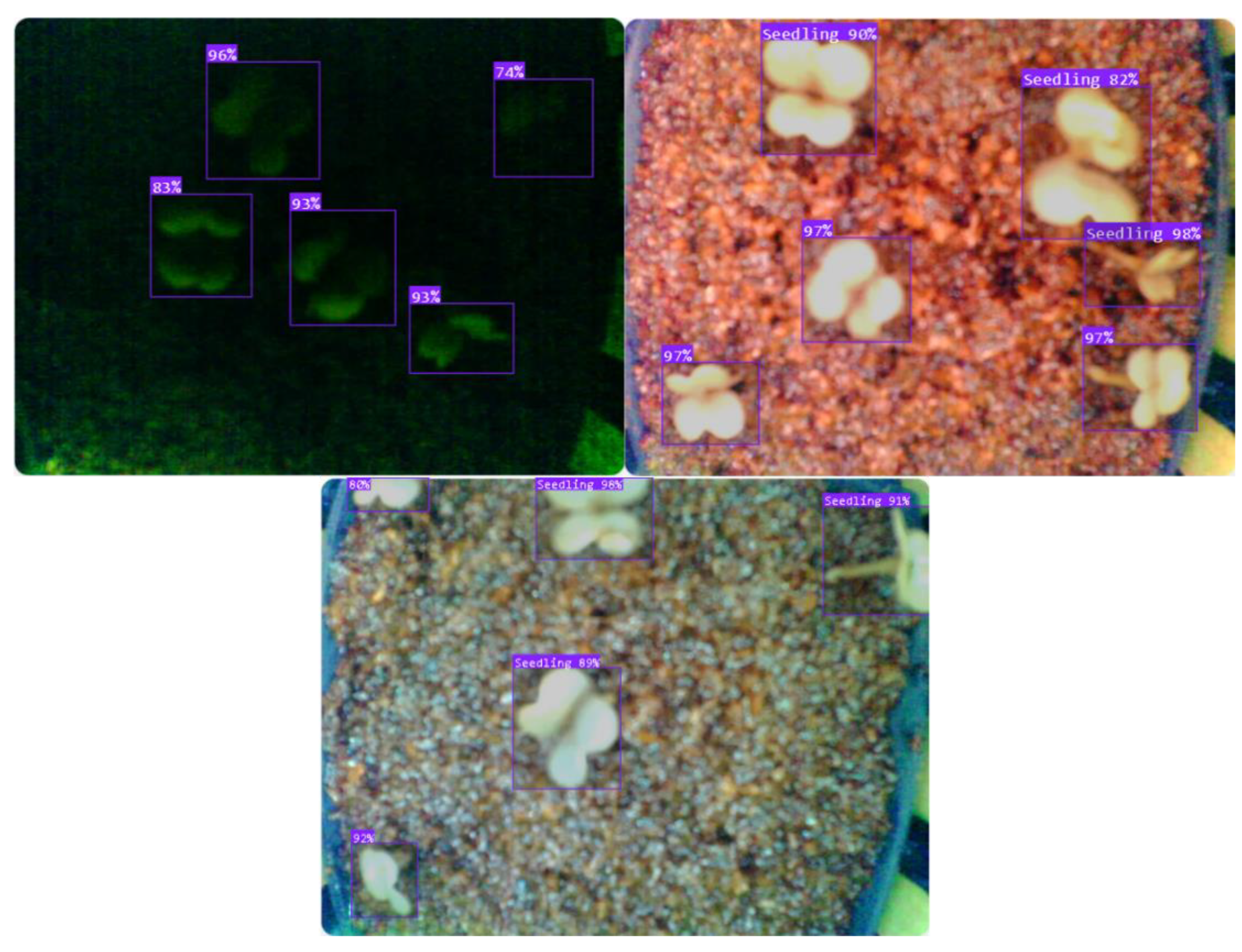

3.3. Performance and Evaluation of the Roboflow 3.0 Model for Germination Detection

4. Conclusion and Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- M. Swartwout, “The first one hundred cubesats: A statistical look,” Journal of small Satellites, vol. 2, no. 2, pp. 213–233, 2013.

- P. Zabel, M. Bamsey, D. Schubert, and M. Tajmar, “Review and analysis of over 40 years of space plant growth systems,” Life sciences in space research, vol. 10, pp. 1–16, 2016. [CrossRef]

- A.-L. Paul, C. E. Amalfitano, and R. J. Ferl, “Plant growth strategies are remodeled by spaceflight,” BMC Plant Biol, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 232, Dec. 2012, doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-12-232. [CrossRef]

- J. Puig-Suari, C. Turner, and W. Ahlgren, “Development of the standard CubeSat deployer and a CubeSat class PicoSatellite,” in 2001 IEEE aerospace conference proceedings (Cat. No. 01TH8542), IEEE, 2001, pp. 1–347. Accessed: Dec. 02, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/931726/.

- D. J. Barnhart, T. Vladimirova, and M. N. Sweeting, “Very-Small-Satellite Design for Distributed Space Missions,” Journal of Spacecraft and Rockets, vol. 44, no. 6, pp. 1294–1306, Nov. 2007, doi: 10.2514/1.28678. [CrossRef]

- Jiaolong Zhang, Jingao Su, Chao Wang, Yiqian Sun, Modular design and structural optimization of CubeSat separation mechanism, Acta Astronautica, Volume 225, 2024, Pages 758-767, ISSN 0094-5765, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actaastro.2024.09.067. [CrossRef]

- Sarat Chandra Nagavarapu, Laveneishyan B. Mogan, Amal Chandran, Daniel E. Hastings, CubeSats for space debris removal from LEO: Prototype design of a robotic arm-based deorbiter CubeSat, Advances in Space Research, 2024,ISSN 0273-1177, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asr.2024.08.009. [CrossRef]

- A. Z. Babar and O. B. Akan, “Sustainable and Precision Agriculture with the Internet of Everything (IoE),” Apr. 13, 2024, arXiv: arXiv:2404.06341. doi: 10.48550/arXiv.2404.06341. [CrossRef]

- V. Bhanumathi and K. Kalaivanan, “The Role of Geospatial Technology with IoT for Precision Agriculture,” in Cloud Computing for Geospatial Big Data Analytics, vol. 49, H. Das, R. K. Barik, H. Dubey, and D. S. Roy, Eds., in Studies in Big Data, vol. 49. , Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2019, pp. 225–250. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-03359-0_11. [CrossRef]

- L. Capogrosso, F. Cunico, D. S. Cheng, F. Fummi, and M. Cristani, “A machine learning-oriented survey on tiny machine learning,” IEEE Access, 2024, Accessed: Dec. 07, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/10433185/.

- J. Kua, S. W. Loke, C. Arora, N. Fernando, and C. Ranaweera, “Internet of things in space: a review of opportunities and challenges from satellite-aided computing to digitally-enhanced space living,” Sensors, vol. 21, no. 23, p. 8117, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. T. Arzo et al., “Essential technologies and concepts for massive space exploration: Challenges and opportunities,” IEEE Transactions on Aerospace and Electronic Systems, vol. 59, no. 1, pp. 3–29, 2022. [CrossRef]

- D. Witczak and S. Szymoniak, “Review of Monitoring and Control Systems Based on Internet of Things,” Applied Sciences, vol. 14, no. 19, p. 8943, 2024. [CrossRef]

- P. Singh and R. Krishnamurthi, “IoT-based real-time object detection system for crop protection and agriculture field security,” J Real-Time Image Proc, vol. 21, no. 4, p. 106, Aug. 2024, doi: 10.1007/s11554-024-01488-8. [CrossRef]

- J. Miao, “A Fog-Enabled Microservice-Based Multi-Sensor IoT System for Smart Agriculture,” PhD Thesis, University of Colorado at Boulder, 2024. Accessed: Dec. 07, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://search.proquest.com/openview/de1fb724683f0eafe46c21b732eca54d/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y.

- B. R. Babu, P. M. A. Khan, S. Vishnu, and K. L. Raju, “Design and Implementation of an IoT-Enabled Remote Surveillance Rover for Versatile Applications,” in 2022 IEEE Conference on Interdisciplinary Approaches in Technology and Management for Social Innovation (IATMSI), IEEE, 2022, pp. 1–6. Accessed: Dec. 07, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/abstract/document/10119249/.

- J. Kua, S. W. Loke, C. Arora, N. Fernando, and C. Ranaweera, “Internet of things in space: a review of opportunities and challenges from satellite-aided computing to digitally-enhanced space living,” Sensors, vol. 21, no. 23, p. 8117, 2021. [CrossRef]

- K.-K. Phan, “Development of a Plant Growth and Health Monitoring System Using Imaging and Sensor Array Information for CubeSat Applications,” Master’s Thesis, University of South Florida, 2024. Accessed: Dec. 07, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://search.proquest.com/openview/5551d8f931b1b3a264cf9e3462547b6d/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y.

- G. Fortino, A. Guerrieri, P. Pace, C. Savaglio, and G. Spezzano, “Iot platforms and security: An analysis of the leading industrial/commercial solutions,” Sensors, vol. 22, no. 6, p. 2196, 2022. [CrossRef]

- O. Debauche, S. Mahmoudi, P. Manneback, and F. Lebeau, “Cloud and distributed architectures for data management in agriculture 4.0: Review and future trends,” Journal of King Saud University-Computer and Information Sciences, vol. 34, no. 9, pp. 7494–7514, 2022.

- W. Liu, M. Wu, G. Wan, and M. Xu, “Digital Twin of Space Environment: Development, Challenges, Applications, and Future Outlook,” Remote Sensing, vol. 16, no. 16, p. 3023, 2024.

- T. Shymanovich and J. Z. Kiss, “Conducting Plant Experiments in Space and on the Moon,” in Plant Gravitropism, vol. 2368, E. B. Blancaflor, Ed., in Methods in Molecular Biology, vol. 2368. , New York, NY: Springer US, 2022, pp. 165–198. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-1677-2_12. [CrossRef]

- N. J. Bonafede Jr, “Low-Cost Reaction Wheel Design for CubeSat Applications,” Master’s Thesis, California Polytechnic State University, 2020. Accessed: Dec. 07, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://search.proquest.com/openview/2432317f023a1312d5582f7cd6365c0b/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y.

- M. Sathasivam, R. Hosamani, and B. K. Swamy, “Plant responses to real and simulated microgravity,” Life Sciences in Space Research, vol. 28, pp. 74–86, 2021. [CrossRef]

- A. Poghosyan and A. Golkar, “CubeSat evolution: Analyzing CubeSat capabilities for conducting science missions,” Progress in Aerospace Sciences, vol. 88, pp. 59–83, 2017. [CrossRef]

- A. Poghosyan and A. Golkar, “CubeSat evolution: Analyzing CubeSat capabilities for conducting science missions,” Progress in Aerospace Sciences, vol. 88, pp. 59–83, 2017. [CrossRef]

- F. Arneodo, A. Di Giovanni, and P. Marpu, “A review of requirements for gamma radiation detection in space using cubesats,” Applied Sciences, vol. 11, no. 6, p. 2659, 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Marzioli et al., “CultCube: Experiments in autonomous in-orbit cultivation on-board a 12-Units CubeSat platform,” Life Sciences in Space Research, vol. 25, pp. 42–52, 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. Carillo, B. Morrone, G. M. Fusco, S. De Pascale, and Y. Rouphael, “Challenges for a sustainable food production system on board of the international space station: A technical review,” Agronomy, vol. 10, no. 5, p. 687, 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. Johansen, M. G. Ziliani, R. Houborg, T. E. Franz, and M. F. McCabe, “CubeSat constellations provide enhanced crop phenology and digital agricultural insights using daily leaf area index retrievals,” Scientific reports, vol. 12, no. 1, p. 5244, 2022. [CrossRef]

- K. G. Falk et al., “Computer vision and machine learning enabled soybean root phenotyping pipeline,” Plant Methods, vol. 16, no. 1, p. 5, Dec. 2020, doi: 10.1186/s13007-019-0550-5. [CrossRef]

- V. G. Dhanya et al., “Deep learning based computer vision approaches for smart agricultural applications,” Artificial Intelligence in Agriculture, vol. 6, pp. 211–229, 2022. [CrossRef]

- F. Fuentes-Peñailillo, G. Carrasco Silva, R. Pérez Guzmán, I. Burgos, and F. Ewertz, “Automating seedling counts in horticulture using computer vision and AI,” Horticulturae, vol. 9, no. 10, p. 1134, 2023. [CrossRef]

- T. Mahendrakar, R. T. White, M. Tiwari, and M. Wilde, “Unknown Non-Cooperative Spacecraft Characterization with Lightweight Convolutional Neural Networks,” Journal of Aerospace Information Systems, vol. 21, no. 5, pp. 455–460, May 2024, doi: 10.2514/1.I011343. [CrossRef]

- S. Lange, “UTILIZING MACHINE LEARNING ENSEMBLES FOR PHENOTYPIC TRAIT ANALYSIS IN PLANT MONITORING.” 2024. Accessed: Dec. 07, 2024. [Online]. Available: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2:1867296.

- N. N. Thilakarathne, M. S. A. Bakar, P. E. Abas, and H. Yassin, “Towards making the fields talks: A real-time cloud enabled iot crop management platform for smart agriculture,” Frontiers in Plant Science, vol. 13, p. 1030168, 2023. [CrossRef]

- A. Paul, R. Machavaram, D. Kumar, and H. Nagar, “Smart solutions for capsicum Harvesting: Unleashing the power of YOLO for Detection, Segmentation, growth stage Classification, Counting, and real-time mobile identification,” Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, vol. 219, p. 108832, 2024.

- I. F. Akyildiz and A. Kak, “The Internet of Space Things/CubeSats,” in IEEE Network, vol. 33, no. 5, pp. 212-218, Sept.-Oct. 2019, doi: 10.1109/MNET.2019.1800445. [CrossRef]

- A. Fernando, L. Lim, A. Bandala, R. Vicerra, E. Dadios, M. Guillermo, and R. Naguib, “Simulated vs Actual Application of Symbiotic Model on Six Wheel Modular Multi-Agent System for Linear Traversal Mission,” J. Adv. Comput. Intell. Intell. Inform., Vol.28 No.1, pp. 12-20, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Fernando, Arvin H., et al. “Load Pushing Capacity Analysis of Individual and Multi-Cooperative Mobile Robot through Symbiotic Application.” International Journal of Mechanical Engineering and Robotics Research 13.2 (2024). [CrossRef]

- R. A. R. Bedruz, J. Martin Z. Maningo, A. H. Fernando, A. A. Bandala, R. R. P. Vicerra and E. P. Dadios, “Dynamic Peloton Formation Configuration Algorithm of Swarm Robots for Aerodynamic Effects Optimization,” 2019 7th International Conference on Robot Intelligence Technology and Applications (RiTA), Daejeon, Korea (South), 2019, pp.264-267, doi: 10.1109/RITAPP.2019.8932871. [CrossRef]

- J. M. Paule, J. R. Roca, K. M. Subia, T. J. T. Tiong, M. Guillermo and D. de Veas-Abuan, “Integration of AWS and Roboflow Mask R-CNN Model for a Fully Cloud-Based Image Segmentation Platform,” 2023 IEEE 15th International Conference on Humanoid, Nanotechnology, Information Technology, Communication and Control, Environment, and Management (HNICEM), Coron, Palawan, Philippines, 2023, pp. 1-6, doi: 10.1109/HNICEM60674.2023.10589105. [CrossRef]

- A. R. A. Pascua, M. Rivera, M. Guillermo, A. Bandala and E. Sybingco, “Face Recognition and Identification Using Successive Subspace Learning for Human Resource Utilization Assessment,” 2022 13th International Conference on Information and Communication Technology Convergence (ICTC), Jeju Island, Korea, Republic of, 2022, pp. 1375-1380, doi: 10.1109/ICTC55196.2022.9952691. [CrossRef]

- A. H. Fernando, A. B. Maglaya and A. T. Ubando, “Optimization of an algae ball mill grinder using artificial neural network,” 2016 IEEE Region 10 Conference (TENCON), Singapore, 2016, pp. 3752-3756, doi:10.1109/TENCON.2016.7848762. [CrossRef]

- Agoo, J.; Lanuza, R.J.; Lee, J.; Rivera, P.A.; Velasco, N.O.; Guillermo, M.; Fernando, A. Geographic Information System-Based Framework for Sustainable Small and Medium-Sized Enterprise Logistics Operations. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14010001. [CrossRef]

- Amante, K., Ho, L., Lay, A., Tungol, J., Maglaya, A., & Fernando, A. (2021, March). Design, fabrication, and testing of an automated machine for the processing of dried water hyacinth stalks for handicrafts. In IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering (Vol. 1109, No. 1, p. 012008). IOP Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Fernando, A., and L. GanLim. “Velocity analysis of a six wheel modular mobile robot using MATLAB-Simulink.” IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering. Vol. 1109. No. 1. IOP Publishing, 2021.

| Library Header | Function |

|---|---|

| WiFi.h | Provides functions to connect the ESP32 to a Wi-Fi network, enabling network communication. |

| WebServer.h | Allows the ESP32 to act as a web server, handling HTTP requests and serving web pages and files. |

| WebSocketsServer.h | Enables real-time, bidirectional communication between the ESP32 and the client via WebSockets. |

| FS.h | Provides file system functionality for managing files on the ESP32’s internal flash memory. |

| LittleFS.h | A lightweight file system is used for storing files (e.g., images) on the ESP32’s internal storage. |

| ArduinoJson.h | Used to format and parse JSON data for easy transmission between the ESP32 and the client. |

| Category | Parameter | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Preprocessing | Auto-Orient | Applied |

| Resize | Stretch to 640x640 | |

| Augmentations | Outputs per Training Example | 2 |

| Grayscale | Apply to 100% of images | |

| Saturation | Between -72% and +72% | |

| Brightness | Between -38% and +38% | |

| Blur | Up to 2.1px | |

| Noise | Up to 1.6% of pixels |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).