Submitted:

31 December 2024

Posted:

03 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area and Data Collection

B*0.111+EC*0.059+As*0.048+Cu*0.039

2.2. Machine Learning-Based Model

2.3. Methodology

- Data preparation. The physicochemical data corresponding to the monitoring station described in Table 1 were accessed from the official DGA website. Data corresponding to variables indicated in Table 2 were prepared and standardized using spline as explained before in order to use on the training, and testing the models.

- Model generation. This step consists of training for each sampling site using SVM algorithm. For each dataset, part of the data is used for training, while the rest is used for validation at a 70-30 ratio.

- Model visualization and quality analysis. In this stage, models’ results were visualized and analyzed in order to determine their validity. Evaluation consisted of check the performance of each model generated with SVM for each dataset. To do this and in a similar way to [35], values of certainty such as accuracy (Acc), recall (r), precision (p) and F1 Score were used. The way these values of certainty were calculated and their importance for model quality are described below. This state also includes a result analysis, this analysis aimed at establishing if the results obtained are useful for the WQ classification for each sample site.

3. Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nayak, B.; Panda, P. K. A Comprehensive Review of Water Quality Analysis. International Journal of Image and Graphics 2024, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adangampurath, S.; Pulikkal, A. Effects of seasonal variation on the water quality of the Kadalundi river, India: evaluation of water quality indices, physicochemical and biological parameters. International Journal of River Basin Management 2024, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang Z.; Wei J.; Peng W.; Zhang R. and H. Zhang. Contents and spatial distribution patterns of heavy metals in the hinterland of the Tengger Desert. China. J. Arid. Land 2022, 14, 1086–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Berenguer G.; Pérez-García J; García-Fernández A.; Martínez-López E. High levels of heavy metals detected in feathers of an avian scavenger warn of a high pollution risk in the Atacama Desert (Chile). Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol 2021, 81, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kereszturi, A. Unique and potentially Mars-relevant flow regime and water sources at a high Andes-Atacama site. Astrobiology 2020, 20, 723–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino-Vargas, E.; Chavarri-Velarde, E. Evidence of climate change in the hyper-arid region of the southern coast of Peru, head of the Atacama Desert. Tecnol. Cienc. del Agua 2022, 13, 333–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen M.; Tan Y.; Xu X,; Lin Y. Identifying ecological degradation and restoration zone based on ecosystem quality: A case study of Yangtze River Delta. Applied Geography 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Lu, J. Identification of river water pollution characteristics based on projection pursuit and factor analysis. Environ. Earth Sci 2014, 72, 3409–3417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, V.; Bravo, I.; Saavedra, M. Water Quality Classification and Machine Learning Model for Predicting Water Quality Status—A Study on Loa River Located in an Extremely Arid Environment: Atacama Desert. Water 2023, 15, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidiac S.; El Najjar P.; Ouaini O; El Rayess Y.; El Azzi D. A comprehensive review of water quality indices (WQIs): history, models, attempts and perspectives. Reviews in Environmental Science and Bio/Technology 2023, 22, 349–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Sun, R.; Wang, H.; Wu, X. Trends and Innovations in Surface Water Monitoring via Satellite Altimetry: A 34-Year Bibliometric Review. Remote Sensing 2024, 16, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, F.; Cai, Z.; Shoaib, M.; Iqbal, J.; Ismail, M.; Alrefaei A., F.; Albeshr M., F. Machine learning models for water quality prediction: a comprehensive analysis and uncertainty assessment in Mirpurkhas, Sindh, Pakistan. Water 2024, 16, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frincu R., M. Artificial intelligence in water quality monitoring: a review of water quality assessment applications. Water Quality Research Journal 2024, 59, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, L.; Huang, X.; Huang, D.; Dai, W.; Wang, D. Water quality status response to multiple anthropogenic activities in urban river. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2023, 30, 3440–3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui M., T.; Yáñez-Godoy, H.; Elachachi S., M. Assessment of the Implications and Challenges of Using Artificial Intelligence for Urban Water Networks in the Context of Climate Change When Building Future Resilient and Smart Infrastructures. Journal of Pipeline Systems Engineering and Practice 2024, 16, 03124004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhipi-Shrestha, G.; Mian H., R.; Mohammadiun, S.; Rodriguez, M.; Hewage, K.; Sadiq, R. Digital water: artificial intelligence and soft computing applications for drinking water quality assessment. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy 2023, 25, 1409–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. Méndez, M. Prieto and M. Godoy. Production of subterranean resources in the Atacama Desert: 19th and early 20th-century mining/water extraction in The Taltal district, northern Chile. Political Geogr. 2020, 81, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K. Lizama-Allende C.; Rómila E.; Leiva P.; Guerra; J. Ayala. Evaluation of surface water quality in basins of the Chilean Altiplano-Puna and implications for water treatment and monitoring. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment 2022, 194, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Seong, B.; Park, Y.; Lee W., H.; Heo, T. Y. Explainable artificial intelligence for the interpretation of ensemble learning performance in algal bloom estimation. Water Environment Research 2024, 96, e11140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, P.; Xu, Z.; Fan, W.; Lai, H.; Liu, Y.; Yang, P.; Yang, Z. Exploring the effects of climate change and urban policies on lake water quality using remote sensing and explainable artificial intelligence. Journal of Cleaner Production 2024, 475, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinar, H.; Al-Qaisi A., Z.; Jasim H., K. Optimization Model for Climatic Change Impact on the Water Quality of Al-Hilla River, Iraq. Applied Chemical Engineering 2024, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Chowdhury A., R. Empowering sustainable water management: the confluence of artificial intelligence and Internet of Things. In Current Directions in Water Scarcity Research 2024, 8, 275–291. [Google Scholar]

- Masud M., M.; Shamem A. S., M.; Saif A. N., M.; Bari M., F.; Mostafa, R. The role of artificial intelligence in sustainable water management in Asia: a systematic literature review with bibliographic network visualization. International Journal of Energy and Water Resources 2024, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INN-NCh1333. Official Chilean Standard NCh1333 Water Quality Requirements for Different Uses. INN, National Institute for Standardization 1987, Santiago, Chile.

- INN-NCh409. Official Chilean Drinking Water Standard. INN, National Institute of Standardization 2005, Santiago, Chile.

- Narvaez-Montoya, C.; Mahlknecht, J.; Torres-Martínez J., A.; Mora, A.; Pino-Vargas, E. FlowSOM clustering–A novel pattern recognition approach for water research: Application to a hyper-arid coastal aquifer system. Science of The Total Environment 2024, 915, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayakumar, D.; Bouhoula, A.; Al-Zubari W., K. Unlocking the Potential of Artificial Intelligence for Sustainable Water Management Focusing Operational Applications. Water 2024, 16, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino-Vargas, E.; Espinoza-Molina, J.; Chávarri-Velarde, E.; Quille-Mamani, J.; Ingol-Blanco, E. Impacts of Groundwater Management Policies in the Caplina Aquifer, Atacama Desert. Water 2023, 15, 2610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz F., P.; Latorre, C.; Carrasco-Puga, G.; Wood J., R.; Wilmshurst J., M.; Soto D., C.; Gutiérrez, R. A. Multiscale climate change impacts on plant diversity in the Atacama Desert. Global Change Biology 2019, ƒ25, 1733–1745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnail, E.; Cruces, E.; Rothäusler, E.; Oses, R.; García, A.; Ulloa, C.; Abad, M. An Integrated Approach for the Environmental Characterization of a Coastal Area in the Southern Atacama Desert. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 6360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Zhang, B.; Zhu, Z.; Gao, X.; Hu, Y. Water Quality Prediction of Small-Micro Water Body Based on the Intelligent-Algorithm-Optimized Support Vector Machine Regression Method and Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Multispectral Data. Sustainability 2024, 16, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- V. Flores. Determination of Trees Predictive Models for Surface Roughness in High-Speed Machining (HSP): A Study in Steel and Aluminum Metalworking Industry, in: M. Ferreira (Ed), Research Highlights in Mathematics and Computer Science, volume 4, BP International, India 2023, 42-66. [CrossRef]

- Dritsas, E.; Trigka, M. Efficient Data-Driven Machine Learning Models for Water Quality Prediction. Computation 2023, 11, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haghiabi, A.; Nasrolahi, A.; Parsaie, A. Water quality prediction using machine learning methods. Water Quality Research Journal 2018, 53, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores, V.; Henriquez, N.; Ortiz, E.; Martinez, R.; Leiva, C. Random Forest for generating recommendations for predicting copper recovery by flotation. IEEE Latin America Transactions 2024, 22, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du S., X.; Wu X., L.; Wu T., J. Support vector machine for ultraviolet spectroscopic water quality analyzers. Chinese Journal of Analytical Chemistry 2004, 32, 1227–1230. [Google Scholar]

- Masood, A.; Niazkar, M.; Zakwan, M.; Piraei, R. A machine learning-based framework for water quality index estimation in the Southern Bug River. Water 2023, 15, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, S.; Manikandan, R. Water quality prediction: a data-driven approach exploiting advanced machine learning algorithms with data augmentation. Journal of Water and Climate Change 2024, 15, 431–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gai, R.; Guo, Z. A water quality assessment method based on an improved grey relational analysis and particle swarm optimization multi-classification support vector machine. Frontiers in Plant Science 2023, 14, 1099668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

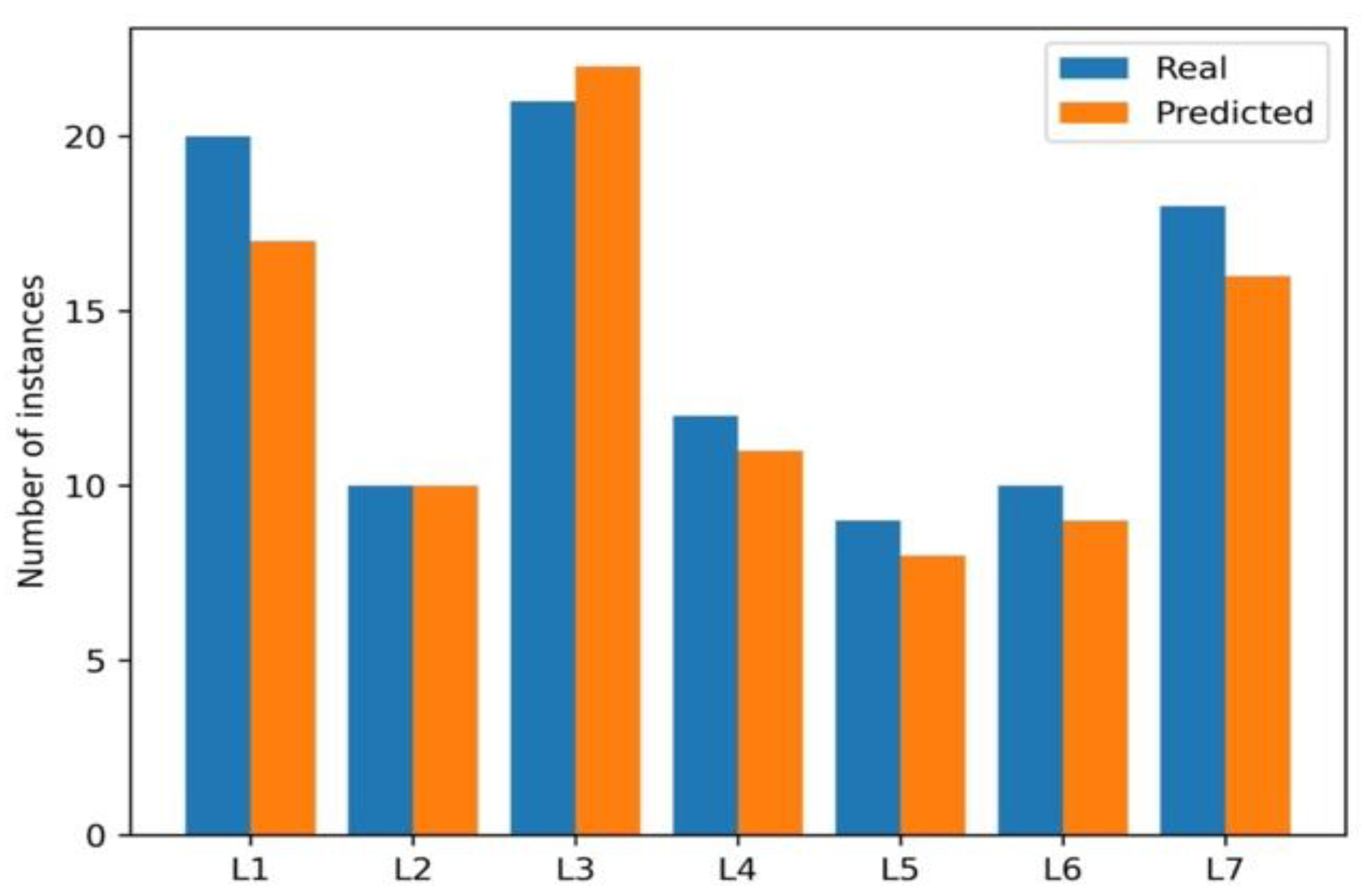

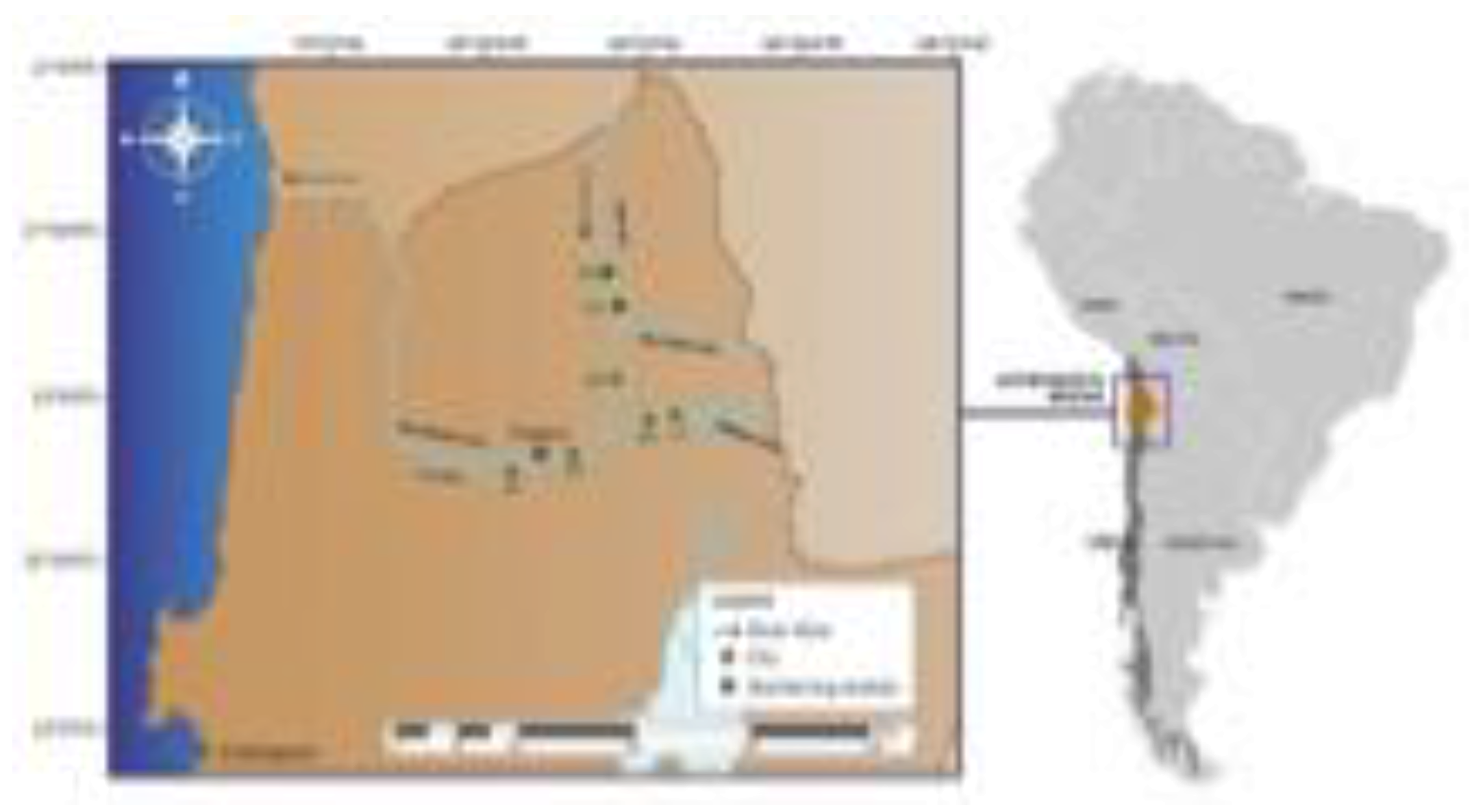

| Sampling site | Location name | S latitude | W longitude |

|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | Salado River at Sifón Ayquina | 22°17′21″ | 68°20′41″ |

| L2 | Chiu Chiu Well | 22°20′22″ | 68°35′56″ |

| L3 | Loa River before Salado River Intersection | 22°21′51″ | 68°39′06″ |

| L4 | Loa River at Escorial | 22°26′43″ | 68°53′25″ |

| L5 | Loa River at Yalquincha | 22°27′02″ | 68°52′45″ |

| L6 | Loa River at Angostura | 22°27′00″ | 68°43′00″ |

| L7 | Loa River at Finca | 22°30′34″ | 68°59′27″ |

| Physicochemical parameter | Maximum value [24] |

Maximum value [25] |

Relative weight [9] |

|---|---|---|---|

| pH | (6.5, 9.5) | (6.5, 8.5) | 0,219 |

| Magnesium (Mg) | ≤135 mg/L | ≤125 mg/L | 0,203 |

| Dissolved Oxygen (O2) | ≤20 mgO2/L | ≤20 mgO2/L | 0,183 |

| Lead (Pb) | ≤0.5 mg/L | ≤0.05 mg/L | 0,140 |

| Boron (B) | ≤0.05 mg/L | ≤0.05 mg/L | 0,111 |

| Electric Conductivity (EC) | ≤3000µ mhos/cm | ≤3000µ mhos/cm | 0,059 |

| Arsenic (As) | ≤0.3 mg/L | ≤0.3 mg/L | 0,048 |

| Copper (Cu) | ≤3.0 mg/L | ≤2.0 mg/L | 0,039 |

| AWQI ranges | WQ value |

|---|---|

| AWQI <25 | high |

| 25 ≤ AWQI < 60 | medium |

| AWQI ≥ 60 | low |

| True low | True medium | true high | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) | Pred. low | 17 | 0 | 0 |

| Pred medium | 0 | 3 | 0 | |

| Pred high | 0 | 2 | 0 | |

| (b) | Pred. low | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Pred medium | 0 | 10 | 2 | |

| Pred high | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| (c) | Pred. low | 21 | 0 | 0 |

| Pred medium | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| Pred high | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| (d) | Pred. low | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Pred medium | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Pred high | 0 | 3 | 0 | |

| (e) | Pred. low | 7 | 2 | 0 |

| Pred medium | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Pred high | 0 | 3 | 0 | |

| (f) | Pred. low | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| Pred medium | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Pred high | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| (g) | Pred. low | 2 | 3 | 0 |

| Pred medium | 0 | 11 | 2 | |

| Pred high | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Sampling site | Acc | r | p | F1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | 0.850 | 0.850 | 0.722 | 0,781 |

| L2 | 0.923 | 0.923 | 1.000 | 0.953 |

| L3 | 0.954 | 0.954 | 0.911 | 0.932 |

| L4 | 0.909 | 0.909 | 0.826 | 0.865 |

| L5 | 0.700 | 0.700 | 0.787 | 0.741 |

| L6 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| L7 | 0.722 | 0.721 | 0.697 | 0.656 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).