Submitted:

02 January 2025

Posted:

07 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participant Selection

2.2. Assessment of Cadmium Exposure Levels and Its Effects

2.3. Normalization of Cadmium, β2M and Albumin Excretion Rates

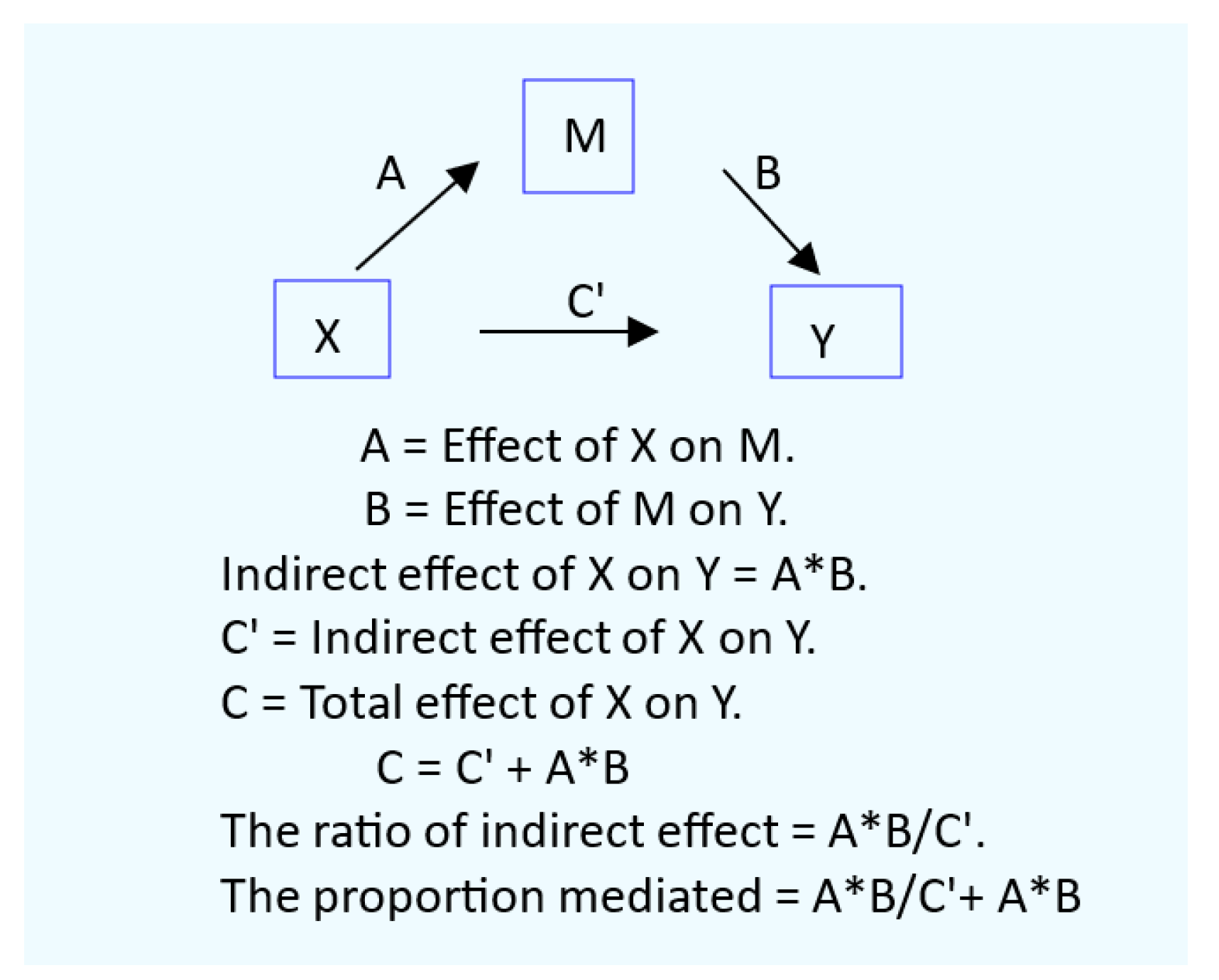

2.4. Mediation Analysis for Cause-Effect Inference

2.5. Statistical Analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Cohort Participants

3.2. Effects of Cadmium on the Risks of Having CKD, Hypertension and Tubular Defect

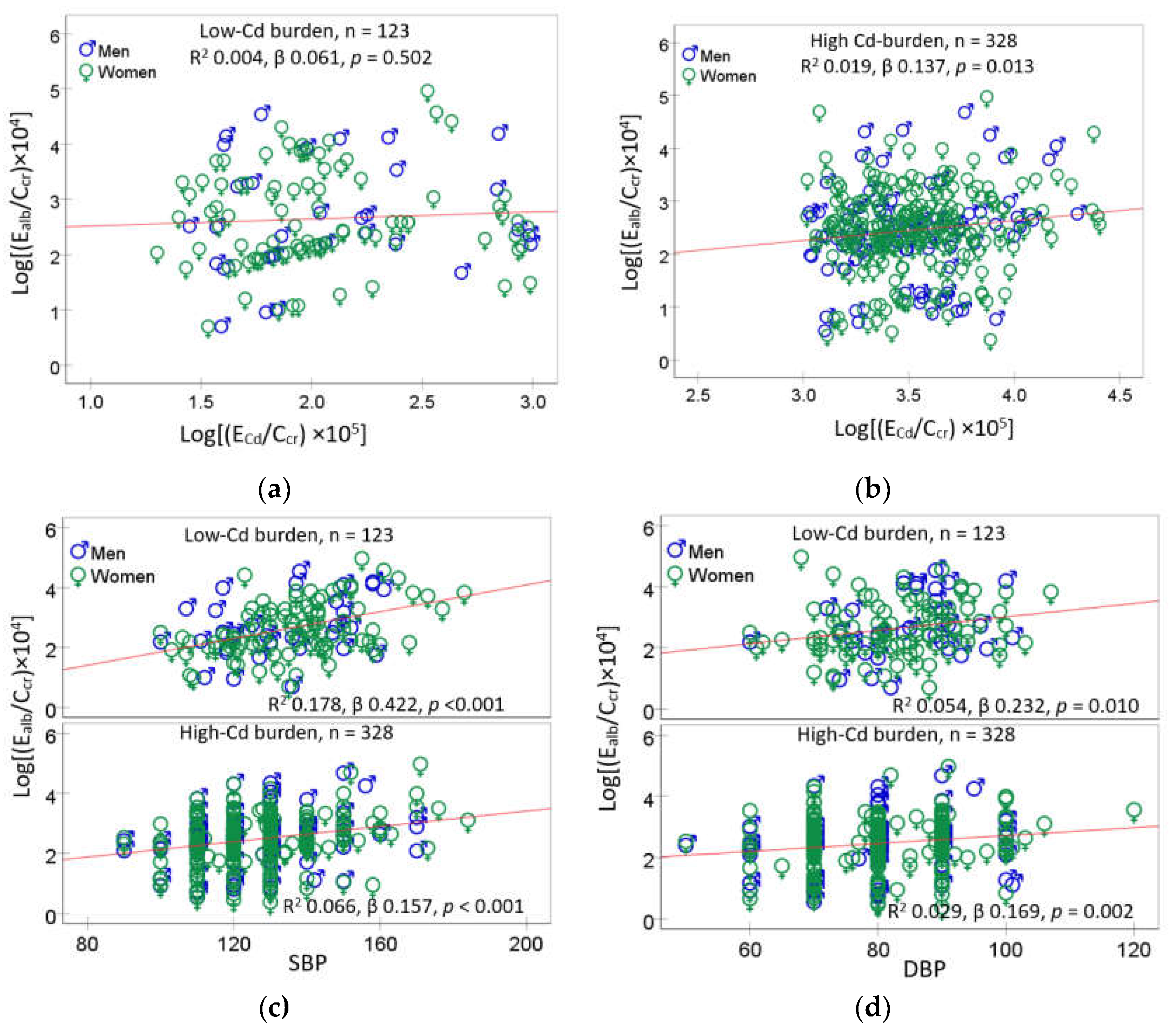

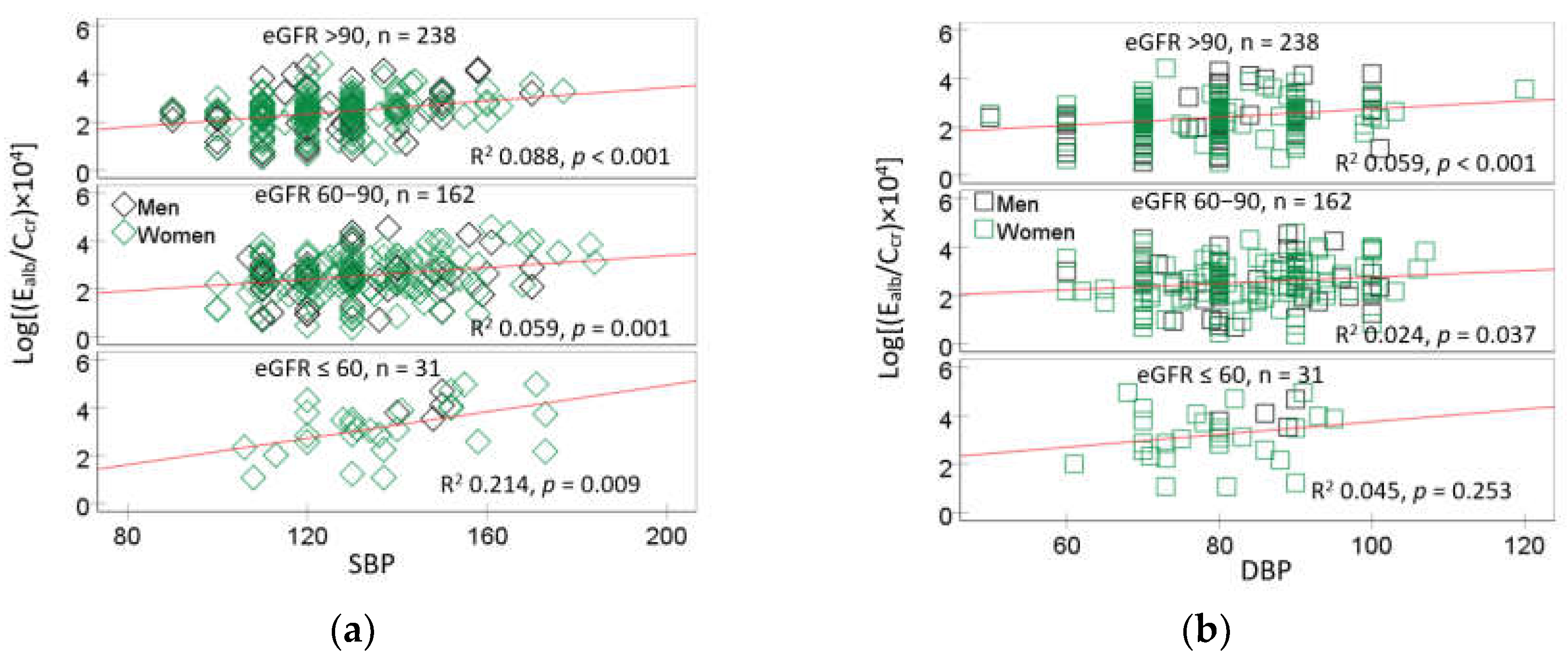

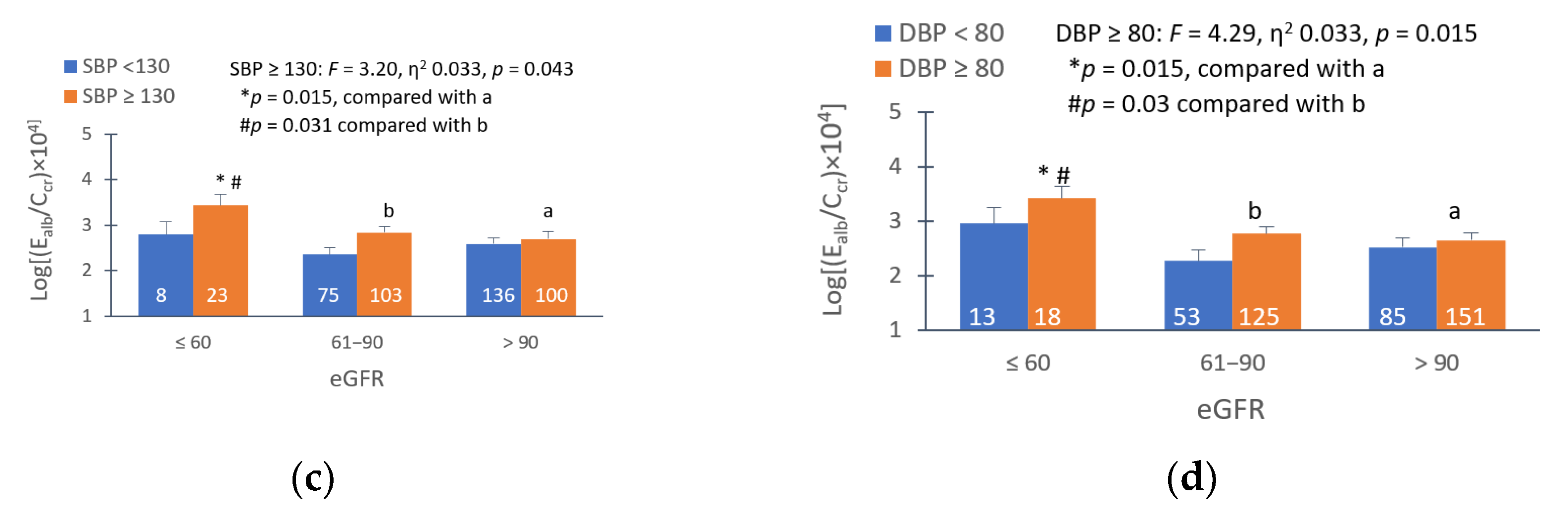

3.3. Effects of Hypertension on the Prevalence of Albuminuria

3.4. Dose-Response Relationship and Quantitative Effect Size

4. Discussion

4.1. Low eGFR, Hypertension and Albuminuria: Are They Causally Connected?

4.2. Effects of Cadmium in Women and Men

4.3. Implications for Toxicological Risk Assessment of Dietry Cadmium Exposure

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Murton, M.; Goff-Leggett, D.; Bobrowska, A.; Garcia Sanchez, J.J.; James, G.; Wittbrodt, E.; Nolan, S.; Sörstadius, E.; Pecoits-Filho, R.; Tuttle, K. Burden of Chronic Kidney Disease by KDIGO Categories of Glomerular Filtration Rate and Albuminuria: A Systematic Review. Adv. Ther. 2021, 38, 180–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, M.; Lewis, R.D.; Morgan, A.R.; Whyte, M.B.; Hanif, W.; Bain, S.C.; Davies, S.; Dashora, U.; Yousef, Z.; Patel, D.C.; et al. A Narrative Review of Chronic Kidney Disease in Clinical Practice: Current Challenges and Future Perspectives. Adv. Ther. 2022, 39, 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farrell, D.R.; Vassalotti, J.A. Screening, identifying, and treating chronic kidney disease: Why, who, when, how, and what? BMC Nephrol. 2024, 25, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foreman, K.J.; Marquez, N.; Dolgert, A.; Fukutaki, K.; Fullman, N.; McGaughey, M.; Pletcher, M.A.; Smith, A.E.; Tang, K.; Yuan, C.W.; et al. Forecasting life expectancy, years of life lost, and all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 250 causes of death: Reference and alternative scenarios for 2016-40 for 195 countries and territories. Lancet 2018, 392, 2052–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GBD 2021 Forecasting Collaborators. Burden of disease scenarios for 204 countries and territories, 2022–2050: A forecasting analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 2024, 403, 2204–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Wang, X.; Sun, Q.; Shi, W.; Zhang, W.; Gao, X.; Li, Y.; Hao, R.; Dong, X.; Chen, C.; et al. Associations of environmental cadmium exposure with kidney damage: Exploring mediating DNA methylation sites in Chinese adults. Environ. Res. 2024, 251(Pt 1) Pt 1, 118667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuma, S.; Nogawa, K.; Watanabe, Y.; Sakurai, M.; Nishijo, M.; Ishizaki, M.; Morikawa, Y.; Kido, T.; Nakagawa, H.; Suwazono, Y. Effect of renal tubular damage on non-cancer mortality in the general Japanese population living in cadmium non-polluted areas. J. Appl. Toxicol. 2023, 43, 1849–1858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smereczański, N.M.; Brzóska, M.M. Current levels of environmental exposure to cadmium in industrialized countries as a risk factor for kidney damage in the general population: A comprehensive review of available data. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satarug, S.; Vesey, D.A.; Gobe, G.C.; Phelps, K.R. The pathogenesis of albuminuria in cadmium nephropathy. Curr. Res. Toxicol. 2023, 6, 100140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satarug, S.; Vesey, D.A.; Gobe, G.C.; Yimthiang, S.; Buha Đorđević, A. Health Risk in a Geographic Area of Thailand with Endemic Cadmium Contamination: Focus on Albuminuria. Toxics 2023, 11, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grau-Perez, M.; Pichler, G.; Galan-Chilet, I.; Briongos-Figuero, L.S.; Rentero-Garrido, P.; Lopez-Izquierdo, R.; Navas-Acien, A.; Weaver, V.; García-Barrera, T.; Gomez-Ariza, J.L.; et al. Urine cadmium levels and albuminuria in a general population from Spain: A gene-environment interaction analysis. Environ. Int. 2017, 106, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, H.J.; Hung, C.H.; Wang, C.W.; Tu, H.P.; Li, C.H.; Tsai, C.C.; Lin, W.Y.; Chen, S.C.; Kuo, C.H. Associations among Heavy Metals and Proteinuria and Chronic Kidney Disease. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021, 11, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jalili, C.; Kazemi, M.; Cheng, H.; Mohammadi, H.; Babaei, A.; Taheri, E.; Moradi, S. Associations between exposure to heavy metals and the risk of chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Toxicol. 2021, 51, 165–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doccioli, C.; Sera, F.; Francavilla, A.; Cupisti, A.; Biggeri, A. Association of cadmium environmental exposure with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 906, 167165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinleye, A.; Oremade, O.; Xu, X. Exposure to low levels of heavy metals and chronic kidney disease in the US population: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0288190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satarug, S.; Vesey, D.A.; Nishijo, M.; Ruangyuttikarn, W.; Gobe, G.C.; Phelps, K.R. The Effect of Cadmium on GFR Is Clarified by Normalization of Excretion Rates to Creatinine Clearance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satarug, S.; Đorđević, A.B.; Yimthiang, S.; Vesey, D.A.; Gobe, G.C. The NOAEL Equivalent of Environmental Cadmium Exposure Associated with GFR Reduction and Chronic Kidney Disease. Toxics 2022, 10, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Ma, Z.; Dang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Cao, S.; Ouyang, C.; Shi, X.; Pan, J.; Hu, X. Associations of urinary and blood cadmium concentrations with all-cause mortality in US adults with chronic kidney disease: A prospective cohort study. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2023, 30, 61659–61671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satarug, S.; Vesey, D.A.; Gobe, G.C.; Phelps, K.R. Estimation of health risks associated with dietary cadmium exposure. Arch. Toxicol. 2023, 97, 329–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fechner, C.; Hackethal, C.; Höpfner, T.; Dietrich, J.; Bloch, D.; Lindtner, O.; Sarvan, I. Results of the BfR MEAL Study: In Germany, mercury is mostly contained in fish and seafood while cadmium, lead, and nickel are present in a broad spectrum of foods. Food Chem. X 2022, 14, 100326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, T.; Kataoka, Y.; Hayashi, K.; Matsuda, R.; Uneyama, C. Dietary exposure of the Japanese general population to elements: Total diet study 2013–2018. Food Saf. 2022, 10, 83–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pokharel, A.; Wu, F. Dietary exposure to cadmium from six common foods in the United States. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2023, 178, 113873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almerud, P.; Zamaratskaia, G.; Lindroos, A.K.; Bjermo, H.; Andersson, E.M.; Lundh, T.; Ankarberg, E.H.; Lignell, S. Cadmium, total mercury, and lead in blood and associations with diet, sociodemographic factors, and smoking in Swedish adolescents. Environ. Res. 2021, 197, 110991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappas, R.S.; Fresquez, M.R.; Watson, C.H. Cigarette smoke cadmium breakthrough from traditional filters: Implications for exposure. J. Anal. Toxicol. 2015, 39, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D.T.; Jandev, V.; Petroni, M.; Atallah-Yunes, N.; Bendinskas, K.; Brann, L.S.; Heffernan, K.; Larsen, D.A.; MacKenzie, J.A.; Palmer, C.D.; et al. Airborne levels of cadmium are correlated with urinary cadmium concentrations among young children living in the New York state city of Syracuse, USA. Environ. Res. 2023, 223, 115450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satarug, S.; Vesey, D.A.; Ruangyuttikarn, W.; Nishijo, M.; Gobe, G.C.; Phelps, K.R. The Source and Pathophysiologic Significance of Excreted Cadmium. Toxics 2019, 7, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashi, T.; Nogawa, K.; Watanabe, Y.; Kido, T.; Sakurai, M.; Nakagawa, H.; Suwazono, Y. Benchmark Dose of Urinary Cadmium for Assessing Renal Tubular and Glomerular Function in a Cadmium-Polluted Area of Japan. Toxics 2024, 12, 836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satarug, S. : Vesey, D.A.; Đorđević, A.B. The NOAEL equivalent for the cumulative body burden of cadmium: focus on proteinuria as an endpoint. J. Environ. Expo. Assess. 2024, 3, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keefe, J.A.; Hwang, S.J.; Huan, T.; Mendelson, M.; Yao, C.; Courchesne, P.; Saleh, M.A.; Madhur, M.S.; Levy, D. Evidence for a causal role of the SH2B3-β2M axis in blood pressure regulation. Hypertension 2019, 73, 497–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashima, Y.; Konta, T.; Kudo, K.; Takasaki, S.; Ichikawa, K.; Suzuki, K.; Shibata, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Kato, T.; Kawata, S.; et al. Increases in urinary albumin and beta2-microglobulin are independently associated with blood pressure in the Japanese general population: The Takahata Study. Hypertens. Res. 2011, 34, 831–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, K.; Konta, T.; Mashima, Y.; Ichikawa, K.; Takasaki, S.; Ikeda, A.; Hoshikawa, M.; Suzuki, K.; Shibata, Y.; Watanabe, T.; et al. The association between renal tubular damage and rapid renal deterioration in the Japanese population: The Takahata study. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2011, 15, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satarug, S.; Vesey, D.A.; Nishijo, M.; Ruangyuttikarn, W.; Gobe, G.C. The inverse association of glomerular function and urinary β2-MG excretion and its implications for cadmium health risk assessment. Environ. Res. 2019, 173, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, F.; Li, M.; Xu, H.; Qin, X.; Teng, Y. Urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio within the normal range and risk of hypertension in the general population: A meta-analysis. J. Clin. Hypertens. (Greenwich) 2021, 23, 1284–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romero-González, G.; Rodríguez-Chitiva, N.; Cañameras, C.; Paúl-Martínez, J.; Urrutia-Jou, M.; Troya, M.; Soler-Majoral, J.; Graterol Torres, F.; Sánchez-Bayá, M.; Calabia, J.; et al. Albuminuria, Forgotten No More: Underlining the Emerging Role in CardioRenal Crosstalk. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGill, J.B.; Haller, H.; Roy-Chaudhury, P.; Cherrington, A.; Wada, T.; Wanner, C.; Ji, L.; Rossing, P. Making an impact on kidney disease in people with type 2 diabetes: the importance of screening for albuminuria. BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2022, 10, e002806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okubo, A.; Nakashima, A.; Doi, S.; Doi, T.; Ueno, T.; Maeda, K.; Tamura, R.; Yamane, K.; Masaki, T. High-normal albuminuria is strongly associated with incident chronic kidney disease in a nondiabetic population with normal range of albuminuria and normal kidney function. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2020, 24, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Song, W.; Zhou, Y.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Deng, L.; Liao, Y.; Wu, B.; et al. Elevated urine albumin creatinine ratio increases cardiovascular mortality in coronary artery disease patients with or without type 2 diabetes mellitus: a multicenter retrospective study. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2023, 22, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satarug, S.; Swaddiwudhipong, W.; Ruangyuttikarn, W.; Nishijo, M.; Ruiz, P. Modeling cadmium exposures in low- and high-exposure areas in Thailand. Environ. Health Perspect. 2013, 121, 531–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yimthiang, S.; Pouyfung, P.; Khamphaya, T.; Kuraeiad, S.; Wongrith, P.; Vesey, D.A.; Gobe, G.C.; Satarug, S. Effects of Environmental Exposure to Cadmium and Lead on the Risks of Diabetes and Kidney Dysfunction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2022, 19, 2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levey, A.S.; Stevens, L.A.; Scmid, C.H.; Zhang, Y.; Castro, A.F., III; Feldman, H.I.; Kusek, J.W.; Eggers, P.; Van Lente, F.; Greene, T.; et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 150, 604–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levey, A.S.; Becker, C.; Inker, L.A. Glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria for detection and staging of acute and chronic kidney disease in adults: a systematic review. JAMA 2015, 313, 837–846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, C.A.; Allen, C.M.; Akbari, A.; Collier, C.P.; Holland, D.C.; Day, A.G.; Knoll, G.A. Comparison of the new and traditional CKD-EPI GFR estimation equations with urinary inulin clearance: A study of equation performance. Clin. Chim. Acta 2019, 488, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phelps, K.R.; Gosmanova, E.O. A generic method for analysis of plasma concentrations. Clin. Nephrol. 2020, 94, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandjean, P.; Budtz-Jørgensen, E. Total imprecision of exposure biomarkers: implications for calculating exposure limits. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2007, 50, 712–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satarug, S. Is Chronic Kidney Disease Due to Cadmium Exposure Inevitable and Can It Be Reversed? Biomedicines 2024, 12, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKinnon, D.P.; Warsi, G.; Dwyer, J.H. A simulation study of mediated effect measures. Multiv. Behav. Res. 1995, 30, 41–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Meth. Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J. Advances in mediation analysis: A survey and synthesis of new developments. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2015, 66, 825–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.; Yan, H.; Fan, X.; Xi, S. A benchmark dose analysis for urinary cadmium and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 273, 116519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Oh, S.; Kang, H.; Kim, S.; Lee, G.; Li, L.; Kim, C.T.; An, J.N.; Oh, Y.K.; Lim, C.S.; et al. Environment-wide association study of CKD. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2020, 15, 766–775. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, H.J.; Hung, C.H.; Wang, C.W.; Tu, H.P.; Li, C.H.; Tsai, C.C.; Lin, W.Y.; Chen, S.C.; Kuo, C.H. Associations among heavy metals and proteinuria and chronic kidney disease. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reckelhoff, J.F. Gender differences in the regulation of blood pressure. Hypertension 2001, 37, 1199–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reckelhoff, J.F. Mechanisms of sex and gender differences in hypertension. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2023, 37, 596–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Connelly, P.J.; Currie, G.; Delles, C. Sex differences in the prevalence, outcomes and management of hypertension. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2022, 24, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, C.; Nagao, Y.; Shibuya, C.; Kashiki, Y.; Shimizu, H. Urinary cadmium and serum levels of estrogens and androgens in postmenopausal Japanese women. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomarkers Prev. 2005, 14, 705–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagata, C.; Konishi, K.; Goto, Y.; Tamura, T.; Wada, K.; Hayashi, M.; Takeda, N.; Yasuda, K. Associations of urinary cadmium with circulating sex hormone levels in pre- and postmenopausal Japanese women. Environ. Res. 2016, 150, 82–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali. I.; Engström, A.; Vahter, M.; Skerfving, S.; Lundh, T.; Lidfeldt, J.; Samsioe, G.; Halldin, K.; Åkesson, A. Associations between cadmium exposure and circulating levels of sex hormones in postmenopausal women. Environ. Res. 2014, 134, 265–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bochud, M.; Jenny-Burri, J.; Pruijm, M.; Ponte, B.; Guessous, I.; Ehret, G.; Petrovic, D.; Dudler, V.; Haldimann, M.; Escher, G.; et al. Urinary Cadmium Excretion Is Associated with Increased Synthesis of Cortico- and Sex Steroids in a Population Study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 103, 748–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

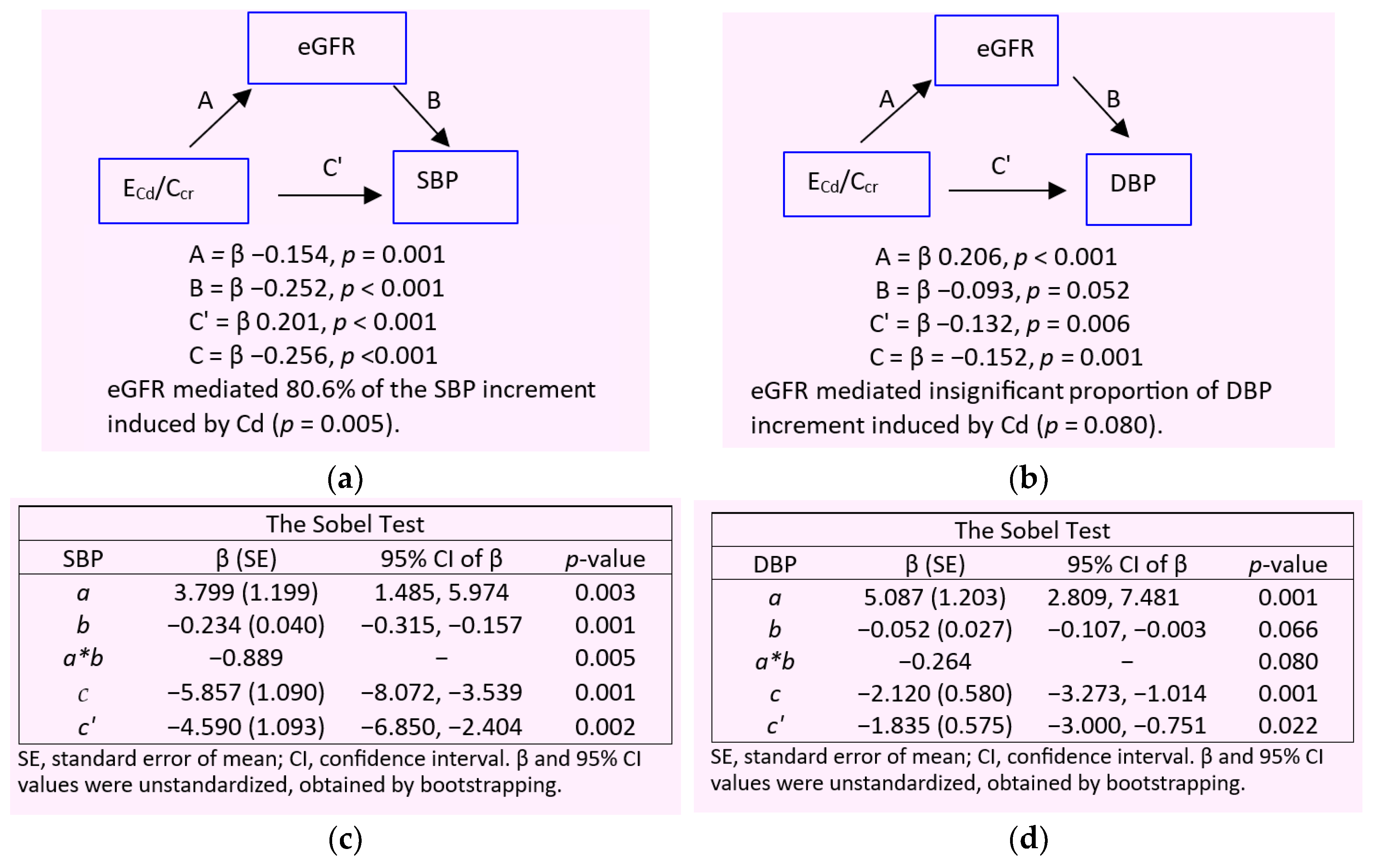

- Satarug, S.; Vesey, D.A.; Yimthiang, S.; Khamphaya, T.; Pouyfung, P.; Đorđević, A.B. Environmental Cadmium Exposure Induces an Increase in Systolic Blood Pressure by Its Effect on GFR. Stresses 2024, 4, 436–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagedoorn, I.J.M.; Gant, C.M.; Huizen, S.V.; Maatman, R.G.H.J.; Navis, G.; Bakker, S.J.L.; Laverman, G.D. Lifestyle-related exposure to cadmium and lead is associated with diabetic kidney disease. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oosterwijk, M.M.; Hagedoorn, I.J.M.; Maatman, R.G.H.J.; Bakker, S.J.L.; Navis, G.; Laverman, G.D. Cadmium, active smoking and renal function deterioration in patients with type 2 diabetes. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2023, 38, 876–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | All n = 641 |

Eβ2M/Ccr, µg/L filtrate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 1.0, n = 442 | 1.0 − 2.9, n = 69 | 3.0 − 9.9, n = 61 | ≥ 10, n = 61 | ||

| Age, years | 47.5 (10.6) | 44.2 (8.9) | 51.1 (9.1) | 55.5 (10.9) | 58.4 (9.8) *** |

| Age range, years | 16 − 80 | 16 − 69 | 21 − 75 | 31 − 80 | 42 − 79 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.4 (4.0) | 24.2 (3.7) | 24.7 (5.2) | 24.8 (4.1) | 24.8 (4.2) |

| % BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 (obese) | 6.3 | 5.0 | 10.4 | 7.2 | 10.0 |

| eGFR a, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 95 (19) | 101 (15) | 93 (14) | 83 (16) | 67 (18) *** |

| % Low eGFR (CKD) | 4.8 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 5.8 | 37.7 *** |

| % Women | 66.9 | 63.8 | 71.1 | 72.5 | 78.7 |

| % Hypertension | 39.8 | 34.4 | 42.2 | 52.2 | 62.3 *** |

| % Smoking | 29.0 | 31.0 | 30.4 | 15.9 | 27.9 |

| % Diabetes | 10.8 | 0.9 | 14.7 | 29.0 | 54.7 *** |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 126 (16) | 122 (13) | 129 (16) | 135 (18) | 140 (18) *** |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 80 (10) | 78.4 (9.2) | 82.8 (10.6) | 84 (10) | 84 (9) *** |

| Normalized to Ecr (Ex/Ecr) | |||||

| ECd/Ecr, µg/g creatinine | 2.98 (4.01) | 3.00 (3.73) | 3.43 (4.35) | 2.35 (4.24) | 3.06 (5.17) *** |

| Eβ2M/Ecr, µg/g creatinine | 516 (2153) | 37 (36) | 221 (74) | 697 (274) | 4124 (5854) *** |

| Ealb/Ecr, mg/g creatinine (ACR) | 22 (65) | 12 (31) | 14 (25) | 22 (51) | 74 (147) *** |

| % Albuminuria b | 14.9 | 9.4 | 13.3 | 17,2 | 38.3 *** |

| Normalized to Ccr, (Ex/Ccr) c | |||||

| (ECd/Ccr) ×100, µg/L filtrate | 2.37 (3.35) | 2.27 (2.84) | 2.67 (3.84) | 2.01 (3.52) | 3.17 (5.34) ** |

| (Eβ2M/Ccr) ×100, µg/L filtrate | 556 (2857) | 27 (26) | 170 (52) | 587 (204) | 4789 (8159) *** |

| (Ealb/Ccr) ×100, µg/L filtrate | 22 (79) | 9 (25) | 11 (22) | 20 (50) | 88 (191) *** |

| % (Ealb/Ccr) ×100 ≥ 20 µg/L filtrate | 16.5 | 9.8 | 11.7 | 21.9 | 45.0 *** |

| Independent Variables/Factors | CKD a | Hypertension | Tubular dysfunction c | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POR (95% CI) | p | POR (95% CI) | p | POR (95% CI) | p | |

| Age, years | 1.156 (1.096, 1.218) | <0.001 | 1.059 (1.041, 1.078) | <0.001 | 1.112 (1.075, 1.149) | <0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 1.027 (0.930, 1.135) | 0.599 | 1.120 (1.071, 1.171) | <0.001 | 0.962 (0.898, 1.031) | 0.273 |

| Log2[(ECd/Ccr) ×105], µg/L filrate | 3.517 (1.754, 7.051) | <0.001 | 1.218 (1.124, 1.319) | <0.001 | 1.037 (0.917, 1.173) | 0.567 |

| Gender | 0.532 (0.150, 1.887) | 0.329 | 1.462 (0.964, 2.215) | 0.074 | 1.321 (0.617, 2.571) | 0.413 |

| Smoking | 0.708 (0.226, 2.215) | 0.553 | 1.477 (0.959, 2.274) | 0.077 | 1.163 (0.585, 2.315) | 0.667 |

| Diabetes | 4.839 (1.725, 13.58) | 0.003 | 2.008 (1.072, 3.726) | 0.030 | 16.12 (7.219, 36.02) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 1.152 (0.497, 2.669) | 0.742 | − | − | 1.556 (0.924, 2.622) | 0.097 |

| CKD b | − | − | 0.877 (0.393, 1.958) | 0.750 | 17.67 (5.155, 60.56) | <0.001 |

| Independent Variables/Factors | Albuminuria a | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All, n = 445 | Normotension, n = 229 | Hypertension, n = 216 | ||||

| POR (95% CI) | p | POR (95% CI) | p | POR (95% CI) | p | |

| Age, years | 1.000 (0.962, 1.039) | 0.988 | 1.004 (0.942, 1.069) | 0.913 | 0.991 (0.940, 1.045) | 0.739 |

| Log2[(ECdCcr)×105], µg/L filtrate | 1.042 (0.905, 1.199) | 0.571 | 0.940 (0.750, 1.179) | 0.593 | 1.088 (0.894, 1.325) | 0.401 |

| Obese | 1.346 (0.525, 3.453) | 0.536 | 1.545 (0.277, 8.626) | 0.620 | 0.930 (0.269, 3.215) | 0.909 |

| CKD | 3.312 (1.272, 8.623) | 0.014 | 3.766 (0.626, 22.65) | 0.147 | 4.293 (1.072, 17.19) | 0.040 |

| Diabetes | 3.603 (1.559, 8.326) | 0.003 | 1.913 (0.397, 9.216) | 0.419 | 5.376 (1.795, 16.10) | 0.003 |

| Gender | 1.458 (0.715, 2.972) | 0.299 | 1.944 (0.690, 5.475) | 0.208 | 0.869 (0.304, 2.483) | 0.793 |

| Smoking | 0.835 (0.400, 1.743) | 0.630 | 0.812 (0.274, 2.409) | 0.708 | 0.776 (0.259, 2.328) | 0.651 |

| Tubular dysfunction b | ||||||

| Moderate | Referent | |||||

| Severe | 1.827 (0.822, 4.062) | 0.139 | 0.866 (0.213, 3.517) | 0.840 | 2.946 (1.038, 8.358) | 0.042 |

| Extremely severe | 2.428 (0.983, 5.997) | 0.054 | 0.655 (0.092, 4.671) | 0.673 | 4.167 (1.250, 13.90) | 0.020 |

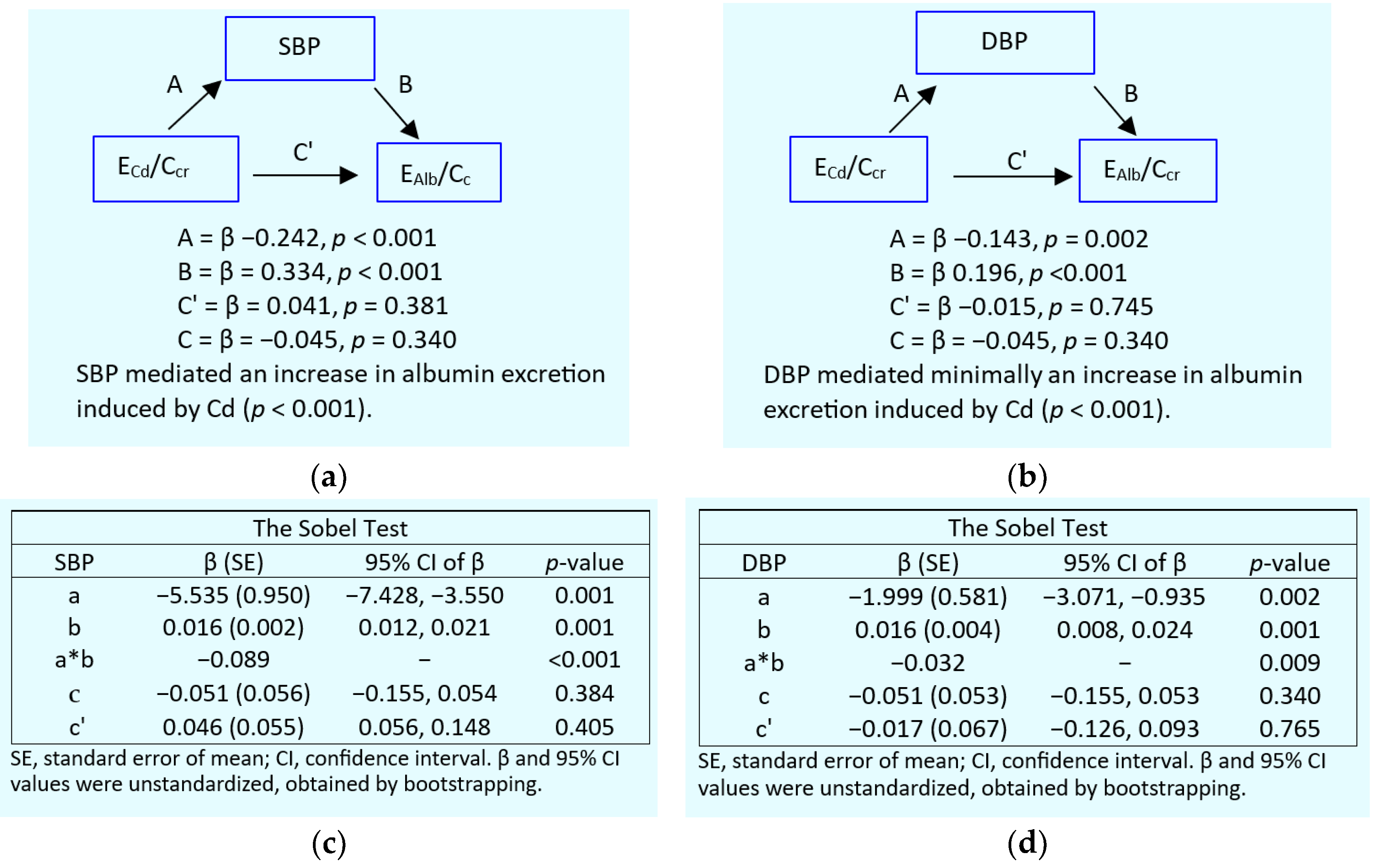

| Independent Variables/Factors |

Log[(Ealb/Ccr)×104], µg/L filtrate | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All, n = 451 | Women, n = 336 | Men, n = 115 | ||||

| β | p | β | p | β | p | |

| Model 1: SBP | ||||||

| Age, years | −0.075 | 0.217 | −0.047 | 0.502 | −0.135 | 0.248 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 0.039 | 0.408 | 0.062 | 0.248 | −0.042 | 0.664 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | −0.180 | 0.001 | −0.188 | 0.002 | −0.174 | 0.090 |

| Log[(ECd/Ccr)×105 ], µg/L filtrate | 0.103 | 0.073 | 0.102 | 0.132 | 0.109 | 0.332 |

| Diabetes | 0.179 | 0.001 | 0.141 | 0.023 | 0.285 | 0.007 |

| Systolic pressure, mmHg | 0.263 | <0.001 | 0.272 | <0.001 | 0.252 | 0.013 |

| Gender | 0.015 | 0.769 | − | − | − | − |

| Smoking | 0.046 | 0.379 | 0.085 | 0.115 | −0.035 | 0.710 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.147 | <0.001 | 0.143 | <0.001 | 0.146 | 0.001 |

| Model 2: DBP | ||||||

| Age, years | −0.006 | 0.921 | 0.028 | 0.695 | −0.086 | 0.465 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 0.051 | 0.289 | 0.072 | 0.191 | −0.026 | 0.797 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | −0.195 | <0.001 | −0.201 | 0.001 | −0.198 | 0.057 |

| Log[(ECd/Ccr)×105 ], µg/L filtrate | 0.122 | 0.039 | 0.119 | 0.085 | 0.128 | 0.265 |

| Diabetes | 0.220 | <0.001 | 0.189 | 0.002 | 0.306 | 0.005 |

| Diastolic pressure, mmHg | 0.150 | 0.001 | 0.149 | 0.005 | 0.152 | 0.125 |

| Gender | 0.011 | 0.839 | − | − | − | − |

| Smoking | 0.032 | 0.547 | 0.068 | 0.214 | −0.040 | 0.680 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.113 | <0.001 | 0.105 | <0.001 | 0.113 | 0.006 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).