1. Introduction

Polyamide-based glass fiber reinforced (PA-GF) composites are widely utilized in both electrical and automotive applications thanks to their exceptional mechanical, thermal, and electrical properties. In the electrical sector, these materials are ideal for components like accessory boxes, levers, and terminal covers in low-voltage circuit breakers, where they are exploited for their stiffness, impact resistance, and thermal stability [

1]. In the automotive sector, PA66 and PA6 composites are commonly employed in interior components, engine parts, and bodywork due to their high stiffness, excellent impact and wear resistance, and strong chemical resilience [

2,

3]. However, the prolonged exposure to high temperatures typical of these applications inevitably leads to degradation, which can significantly affect the long-term performance and reliability of these materials.

In fact, polymeric materials commonly undergo changes over time, a process often referred to as ageing. The degradation of polymers typically involves a partial breakdown of the material into fragments that remain relatively large but are smaller than the initial polymer chains. [

4,

5,

6]. This fragmentation is a key aspect of the ageing process, which can be triggered by prolonged exposure to various environmental factors such as heat, light, moisture, oxygen, and chemicals [

7,

8].

The primary degradation mechanisms in PA66 composites during thermal ageing include:

▪ Hydrolysis: a chemical degradation mechanism favored by high temperatures, that occurs when water molecules penetrate the polyamide matrix and break the polymer chains. This can lead to a decrease in molecular weight, plasticization of the matrix, and a reduction in mechanical properties, such as stiffness and strength [

9,

10,

11]. The fiber/matrix interface is particularly susceptible to hydrolysis, as water molecules tend to accumulate in this region [

12,

13,

14].

▪ Thermo-oxidation: another chemical degradation mechanism that involves the reaction of oxygen with the polyamide matrix at elevated temperatures [

15,

16,

17,

18]. This process can lead to chain scission, the formation of free radicals, and the creation of various degradation products, such as carbonyl, chromophoric groups, or peroxides [

19,

20].

▪ Fiber/Matrix Debonding: Ageing can lead to interfacial debonding (or mismatch), which weakens the stress transfer between the matrix and the fibers, resulting in a decline in mechanical properties [

21]. Factors like poor interfacial adhesion [

22], the presence of water [

23,

24], the presence of voids [

25], and the differing coefficients of thermal expansion between the fibers and the matrix [

26] can contribute to debonding.

▪ Physical Ageing/Plasticization: Water absorption can cause plasticization of the polyamide matrix, leading to a decrease in stiffness and an increase in ductility [

27,

28]. This occurs because the water molecules disrupt the hydrogen bonding between the polymer chains, increasing their mobility [

29,

30,

31]. While plasticization can improve toughness in the short term [

32], prolonged exposure to moisture can lead to more severe degradation, like hydrolysis [

33].

Accelerated ageing tests are valuable tools for investigating the long-term effects of thermal ageing on GFRP (Glass Fiber Reinforced Plastics), such as PA66 composites. These tests simulate real-world operating conditions in a shorter timeframe, enabling the assessment of material degradation and the development of lifetime prediction models.

Research has primarily focused on thermal-oxidative ageing, hygrothermal ageing, and the influence of other ageing-related factors, such as manufacturing processes and interfacial engineering.

Shu et al. [

34] studied the thermal-oxidative degradation mechanism demonstrating that early-stage thermal-oxidative ageing in PA6 involves molecular crosslinking, temporarily enhancing mechanical strength and viscosity. However, prolonged exposure leads to chain scission and oxidative byproduct formation, reducing mechanical performance and melting temperature, while increasing crystallinity.

Alexis et al. [

35] extended their investigation to fatigue durability, demonstrating that thermal ageing at 200°C for 500 hours had a significant impact on fatigue life and cyclic indicators such as hysteresis energy density and cyclic mean strain rate. Moreover, ageing led to stiffening and embrittlement in short glass fiber-reinforced PA6/PA66 composites, with lower fiber content exacerbating the degradation.

Similarly, Yarar et al. and Sahin et al. [

36,

37] studied the effects of short-term thermal ageing on PA6 composites. Ageing decreased tensile and flexural strength by up to 10%, while flexural modulus was improved. Moreover, they studied the tribological properties of the material, showing the detrimental effect of ageing that significantly increased wear volume and wear rate.

The role of interfacial engineering in mitigating such degradation was also highlighted by Rudzinski et al. [

38], who were able to improve the thermal-oxidative stability of PA66 composites through advanced fiber sizing. Their work showed that the inclusion of silane, polyurethane, and epoxy/acrylate film formers enhanced interfacial adhesion, mitigating yellowing and preventing fiber separation during ageing.

In a circular economy perspective, Eriksson et al. [

33,

39] considered the reprocessing of aged materials by studying the mechanical properties of recycled glass-fiber-reinforced PA66 under thermal ageing conditions. The research showed that thermal ageing did not considerably change the tensile strength and modulus, while the elongation at break decreased significantly, particularly with increased recycling of the material.

Hygrothermal ageing, which combines the effects of heat and moisture, has also been a focal point of research. Ksouri et al. [

40] investigated PA6 and GF-reinforced PA6 exposed to immersion at 90°C, observing significant reductions in tensile properties and glass transition temperature. The damage, caused by water sorption and plasticization, escalated with prolonged exposure, leading to phenomena like crazing and yellowing.

Bergeret et al. [

41] similarly reported drastic declines in mechanical performance during hygrothermal ageing, attributed to chain scission and water penetration at the fiber/matrix interface.

Li et al. [

42] explored the long-term effects of hydrothermal ageing on GF-reinforced PA6 composites, identifying chain scission and post-crystallization as primary degradation mechanisms that weakened the fiber-matrix interface and reduced tensile strength.

The influence of hydrothermal ageing on wear and tribological behavior of GF-PA6 composites was also investigated by Khakbaz et al. [

43], whose findings revealed that while glass fibers improved wear resistance, ageing weakened tensile strength and increased strain at break due to water absorption.

Further, Wang et al. [

44] compared the long-term hygrothermal ageing resistance of glass fiber reinforced PA and PET composites. They found that GF/PA composites absorbed water at a faster rate and reached higher saturation moisture content compared to GF/PET composites. The ageing also led to a decrease in the tensile strength and heat distortion temperature of both types of composites, but the effect was more pronounced in GF/PA composites, emphasizing the material-specific vulnerabilities of polyamides.

Despite the extensive literature on thermo-oxidative aging of PA-GF composites, to the best of our knowledge, there is a lack of studies focusing on materials engineered for high-temperature applications, such as those incorporating flame retardants, which are critical for ensuring thermal stability and fire resistance in demanding environments.

Therefore, this study focuses on a specific type of glass fiber-reinforced polyamide 6,6 composite containing halogenated flame retardants, which is commonly used for electrical components working at moderately high temperatures.

The research investigates the thermal ageing behavior of this materials performed accelerated ageing tests at temperatures between 160 and 210°C, with detailed characterization of its mechanical, thermal, and chemical properties to evaluate the extent of degradation. An Arrhenius-type ageing model is developed to determine the activation energy of the degradation process and establish a temperature-time relationship, offering a predictive framework for assessing the long-term performance and reliability of the composite in high-temperature applications. Activation energy estimations are ultimately compared with results obtained from modulated thermogravimetry and correlated to the hypothesized degradation mechanism.

2. Materials and Methods

This study focused on a glass fiber-reinforced polyamide composite commonly used for low voltage circuit breakers components working at moderate to high temperatures. The composite, from now on referred to as “PA-GF”, is based on a polyamide 6,6 matrix, containing 25 wt% short glass fiber reinforcement, and utilizing a brominated flame retardant. The material was supplied as both granules and injection molded specimens produced in accordance with ISO 178:2019, measuring 80x10x4 millimeters. After molding, samples were conditioned under controlled humidity and temperature to ensure uniform moisture absorption. For specific tests, samples were dried at 90°C for 3 hours and then stored in a desiccator for 24 hours to evaluate the impact of moisture on their mechanical properties.

Thermal ageing was conducted in an air oven to simulate long-term exposure to elevated temperatures. Four different temperatures were selected: 160, 180, 200, and 210 °C. Specimens were aged for periods up to 1080 hours, with exposure times at each temperature determined based on an assumed Q

10 factor of 2, implying that the degradation rate doubles for every 10°C. The specific ageing times for each temperature are reported in

Table 1.

Flexural properties were measured using a three-point bending test setup as specified in ISO 178. Testing was performed on an Instron universal testing machine equipped with a three-point flexural apparatus and a span length of 64 mm. A loading speed of 5 mm/min was applied after an initial preload of 2 N was reached. Flexural strength, modulus, and strain at break were calculated as an average from stress-strain curves obtained after testing at least five specimens per sample. Baseline tests were conducted on unaged and moisture-conditioned samples to establish reference values for comparison.

To model the effects of thermal ageing, an Arrhenius-based approach was used to describe the relationship between ageing time, temperature, and degradation of flexural properties. The model is governed by equation (1):

where:

▪ k represents the rate of reaction (or property degradation)

▪ A is the pre-exponential factor

▪ Ea is the activation energy

▪ R is the universal gas constant

▪ T is the absolute temperature.

The activation energy for degradation was calculated by plotting the natural logarithm of the degradation time required to reach a specific property threshold against the inverse of the absolute temperature. A threshold corresponding to the 80% of the initial flexural strength has been taken as endpoint, in agreement with the requirements set by ABB for the specific application of the composite in low-voltage circuit breakers.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed using a Waters - TA Instruments TGA 550 to investigate the thermal degradation behavior of the samples and to determine the activation energy through Modulated Thermogravimetry (MTG). The experiments were conducted between 30 and 600°C, with a modulated heating rate of 5°C/min, under air atmosphere.

Thermal properties were analyzed by Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) using a Mettler Toledo DSC821e device. Heating tests were conducted under air with a ramp rate of 20 °C/min. The degree of crystallinity was calculated from the measured melting enthalpy values taking the inorganic content into account.

Molecular changes were monitored by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR) with a Perkin-Elmer Frontier spectrometer in the range of 4000 to 380 cm-1. Characteristic absorption peak, were examined to identify chemical changes caused by thermal ageing.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Preliminary Tests: Water Absorption

Preliminary tests were conducted to evaluate the sensitivity of the composite to water absorption and its impact on mechanical properties. Specimens of PA-GF were exposed to a controlled environment at 25°C and 60% relative humidity (RH) for periods of 0, 8, and 24 days. Flexural tests were performed after each exposure period to assess changes in mechanical behavior.

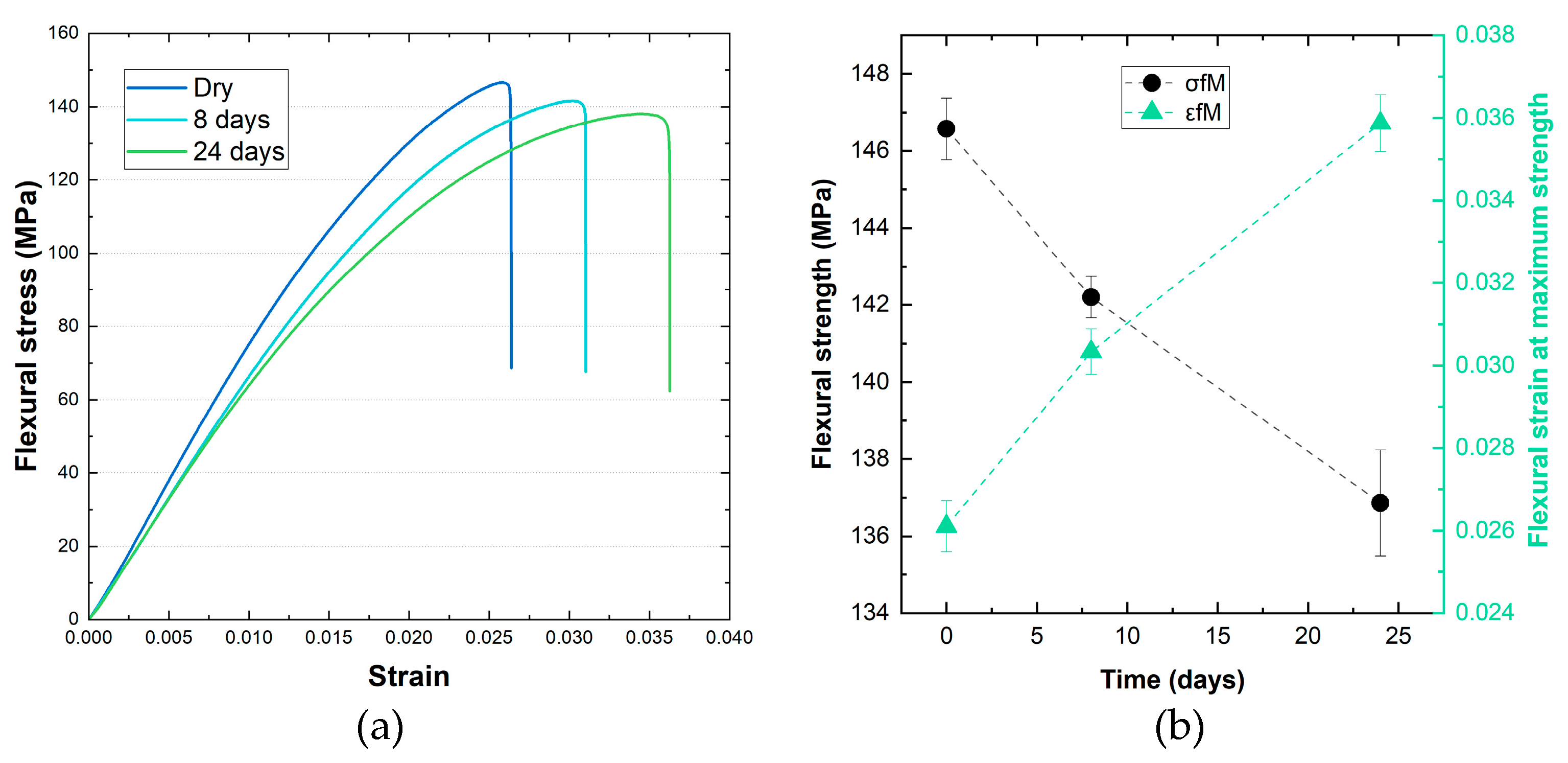

The results reported in

Figure 1 show that water absorption led to a decrease in flexural modulus and strength for both materials. After 8 days of exposure, PA-GF exhibited a reduction in flexural modulus of approximately 8%, which increased to 12% after 24 days. Despite these declines in stiffness, the material displayed an increase in strain at maximum flexural strength, indicating a plasticizing effect caused by moisture uptake.

This enhancement is attributed to the inherent water sensitivity of the polyamide 6,6 matrix, where polar amide groups can coordinate with water molecules, particularly in the amorphous regions, characterized by a higher diffusivity [

45,

46,

47]. This interaction plasticizes the polyamide 6,6 by disrupting hydrogen bonding, increasing flexibility but decreasing strength and stiffness, as highlighted by the 7% decline in flexural strength after 24 days of exposure to moisture.

3.2. Flexural Tests

Given the significant moisture sensitivity of the composites, as evidenced by preliminary testing, all mechanical tests on aged samples were conducted on specimens that had been previously conditioned in a desiccator for 24 hours. This step guaranteed that the observed effects of thermal ageing were not affected by any residual moisture in the samples.

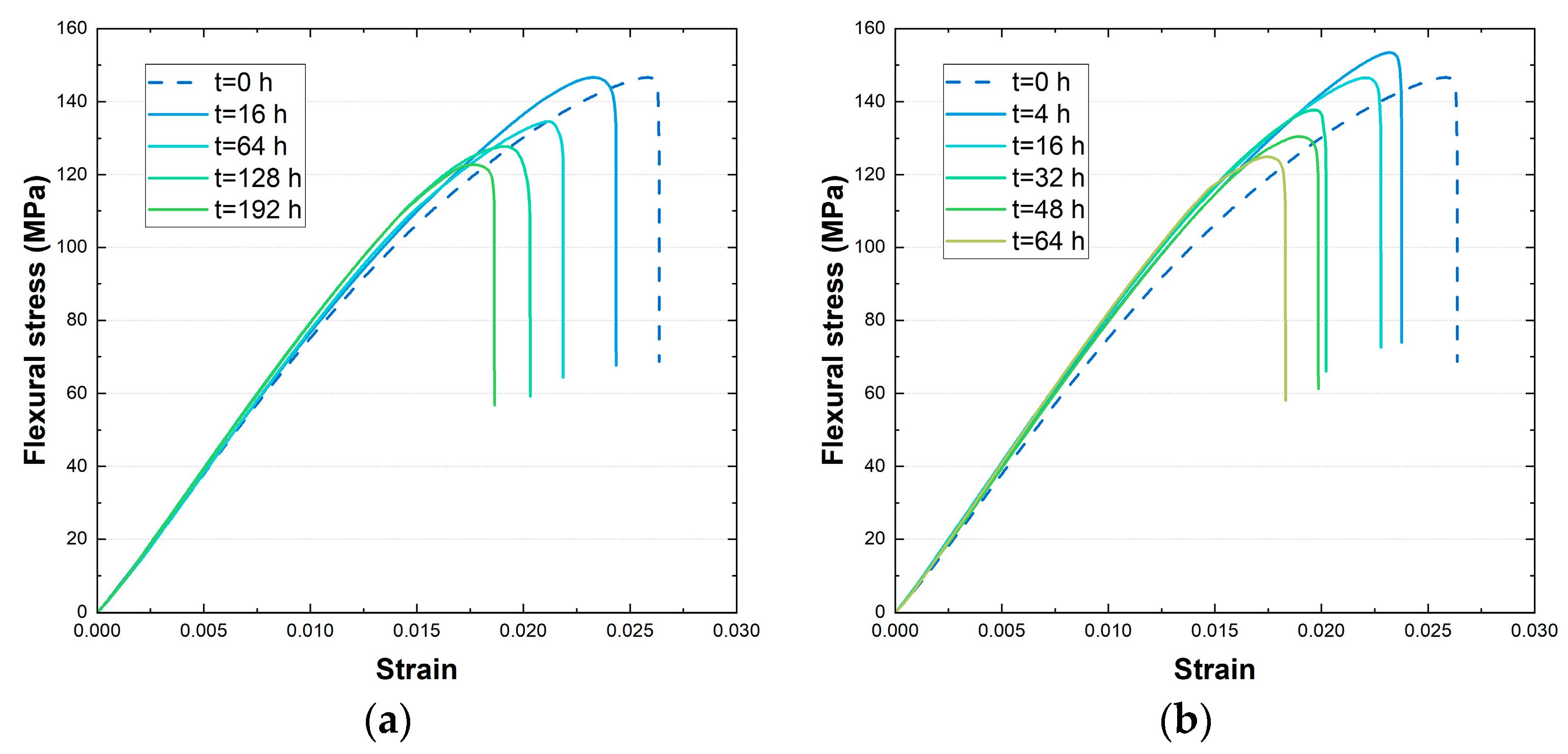

Flexural stress-strain curves obtained for the samples aged at 180°C and 200°C are reported in in

Figure 2. Similar trends are obtained for the other samples, which are reported in the

Supplementary Materials. From the summary of the main flexural properties reported in

Table 2, it is evident that ageing significantly impacts the flexural strength (σ

fM) and flexural strain at maximum strength (ε

fM) of the material, albeit with distinct kinetic patterns for each property.

Specifically, specimens consistently exhibit a decrease in εfM and σfM across all ageing temperatures compared to dry, unaged specimens.

An exception to this trend, is the initial increase of flexural strength for short ageing times at higher temperatures (e.g., 4 hours at 200 °C, in

Figure 2b). This positive effect suggests annealing of the polyamide 6,6 matrix, likely due to residual stress relaxation and potential changes in the crystalline structure [

45,

48,

49]. Stress annealing can be attributed to thermal stresses induced during injection molding, where the material’s skin solidifies faster than the core, inducing tensile stresses. High-temperature ageing can relax these stresses, increasing σ

fM. The change in crystalline structure is further explored in differential scanning calorimetry analysis presented in section 3.5.

On the other hand, both ageing duration and temperature appear to have little influence the slope of the curves, leading only to a slight increase in the flexural elastic modulus Ef from approximately 7200 MPa (unaged samples) to a maximum of 8000 MPa for samples aged for longer times at higher temperatures.

The deterioration in mechanical properties can be ascribed to a combination of factors within the polyamide 6,6 matrix and at the fiber-matrix interface.

Firstly, the dehydration of water molecules coordinated with polar amide groups in both crystalline and amorphous phases, particularly relevant in the early stages of ageing [

46,

47,

49]. Secondly, the progressive degradation of polyamide 6,6 macromolecules due to thermal ageing, especially at higher temperatures and durations, weakens the entanglement of polymer chains and reduces mechanical properties. Additionally, interfacial phenomena, such as thermal expansion mismatch, can contribute to the loss of flexural properties, particularly at high temperatures. This mismatch, coupled with polymer degradation, weakens the load transfer between fibers and the matrix, leading to the formation of micro-voids and cracks at the interface [

40,

48,

50].

Moreover, it is worth observing that the empirical Q10=2 kinetic factor previously considered for the thermal ageing duration, appears to be valid only for shorter durations at higher temperatures.

3.3. Arrhenius Model

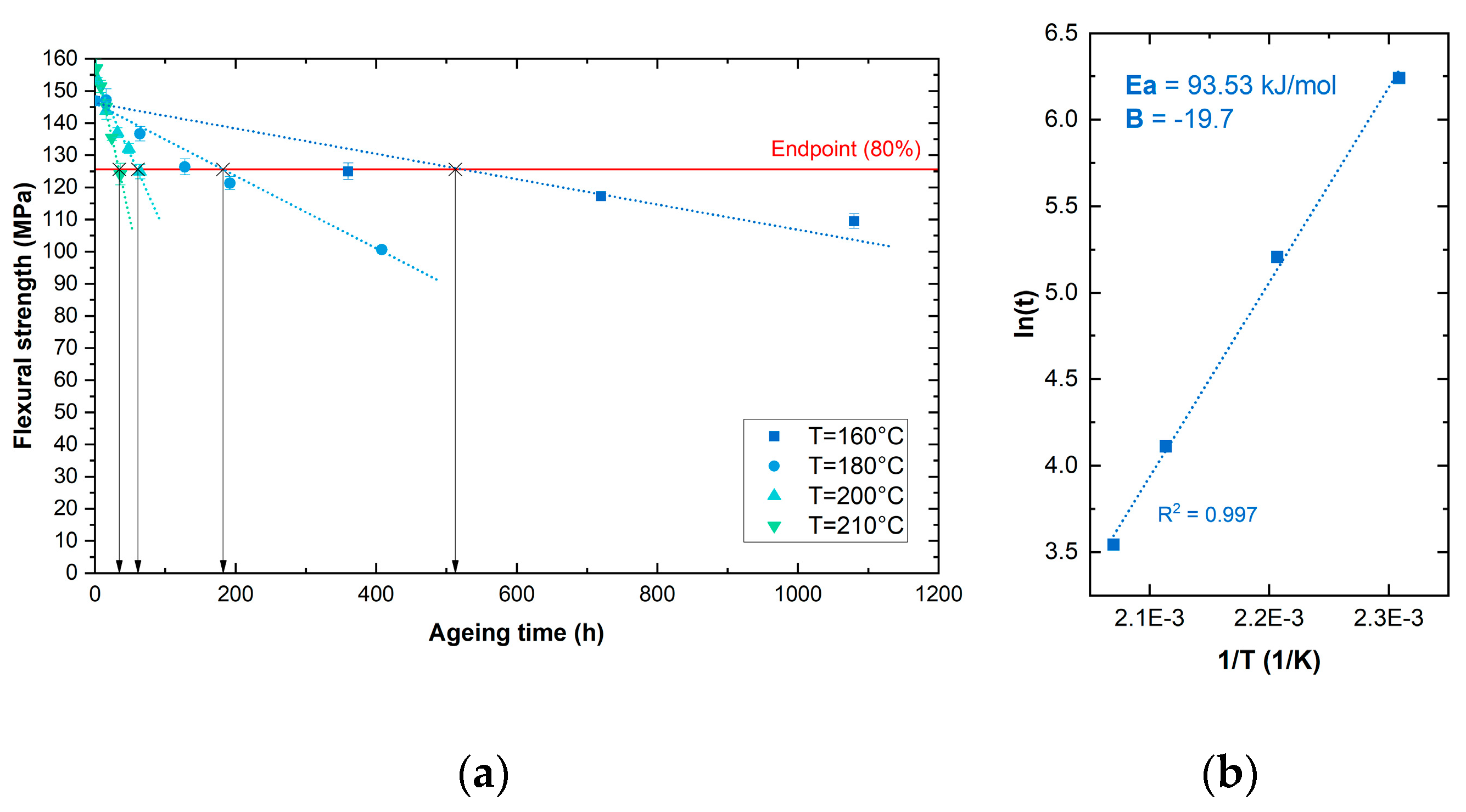

Flexural strength data gathered from mechanical testing at different ageing time and temperatures (

Table 2) has been used to model a lifetime prediction method through the Arrhenius equation (1), which can be linearized into equation (2):

The threshold endpoint selected for the determination of the Arrhenius plot has been set at 80% of flexural strength retained from the material with respect to the initial condition (unaged samples). This value has been chosen considering the acceptability range of mechanical properties indicated by ABB for the use of these materials in low-voltage circuit breakers.

Using the following state function:

where

kᵢ represents the rate of property loss at each ageing condition

i, and

tᵢ and

Tᵢ denote the ageing time and temperature at which a 20% reduction in flexural strength occurs, the Arrhenius equation and the state function are combined to derive the equation (4):

Which can be plotted extrapolating the four values of

tᵢ and

Tᵢ obtained from the mechanical tests. Specifically, the value of tᵢ has been determined by linear interpolation of the experimental points,

as reported in Figure 3a. The obtained Arrhenius plot is depicted in Figure 3b.

From the Arrhenius law, an activation energy of 93.5 kJ/mol was determined, which is consistent, albeit slightly higher, with values reported in the literature. For instance, research by Jung et al. [

51] identified activation energy values in the range of 80-90 kJ/mol by applying an Arrhenius model to the tensile strength retention of aged PA66 composites.

Considering that the material under analysis is currently being used in circuit breakers where it can be exposed to temperature peaks of up to 130°C, an approximated, conservative estimation of its failure time (i.e., time necessary to reach a 20% decline in flexural strength) can be calculated from equation 4. The results are summarized in

Table 3.

The results highlight how PA-GF is a suitable material for components exposed to a maximum continuous temperature of 80°C, which can guarantee its performance for up to 22 years. However, prolonged exposure to higher temperatures, can significantly affect the service life of the components.

Moreover, it is worth noticing, that the activation energy determined by isoconversional methods (such as Ozawa-Flynn-Wall or Kissinger-Akahira-Sunose), ranging from 150 to 190 kJ/mol depending on the specific composite [

52,

53], is reportedly higher than that obtained from the Arrhenius-based methods. To further verify this trend, the modulated thermogravimetric method has been applied to both materials and reported in the next section.

3.4. Modulated Thermogravimetry

In this section, we present the extrapolation of kinetic parameters obtained through Modulated Thermogravimetry (MTG) for the material under analysis. MTG is a technique that applies an oscillatory temperature program to obtain continuous kinetic information during decomposition and volatilization reactions [

54]. By using a sinusoidal temperature modulation, MTG allows for the determination of activation energy and other kinetic parameters throughout the entire decomposition process.

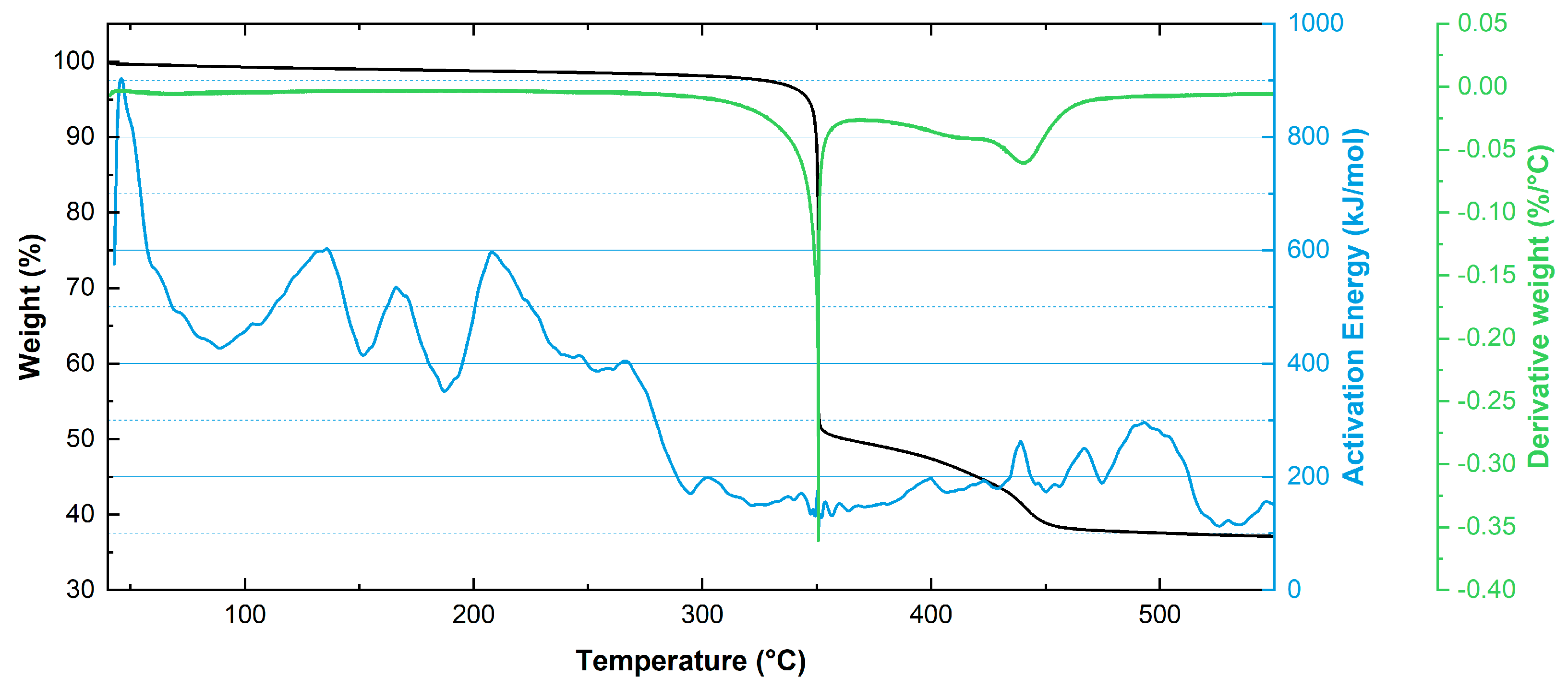

The MTG results are depicted in

Figure 4. The activation energy (Ea) at low weight loss (5–10%) highlights the initial breakdown of the polymer network. In this phase, the activation energy ranges from 90 to 175 kJ/mol, with an average value of approximately 151 kJ/mol. At these early stages, the thermal degradation of polyamides is supposedly driven by the scission of weaker bonds within the polymer structure, such as the the N-alkylamide bond (CH2-NHCO) and the following decomposition of the formed amide group into NH

3 and CO

2 [

55,

56,

57,

58]. As the temperature increases and the degradation progresses, a gradual rise in Ea is observed, reaching its maximum around 300 kJ/mol, likely due to the further scission of the polyamide backbone and the presence of the flame retardant [

59].

The activation energy values obtained with MTG are in good agreement with those reported in the literature using isoconversional methods [

51,

52,

59,

60,

61], however, there is a substantial difference with the Ea values obtained from the Arrhenius model. This difference, already highlighted by previous literature [

52], could be attributed to the different degradation mechanisms involved at the lower temperatures of accelerated ageing tests, and could lead to an overestimation of service life by TGA-based methods.

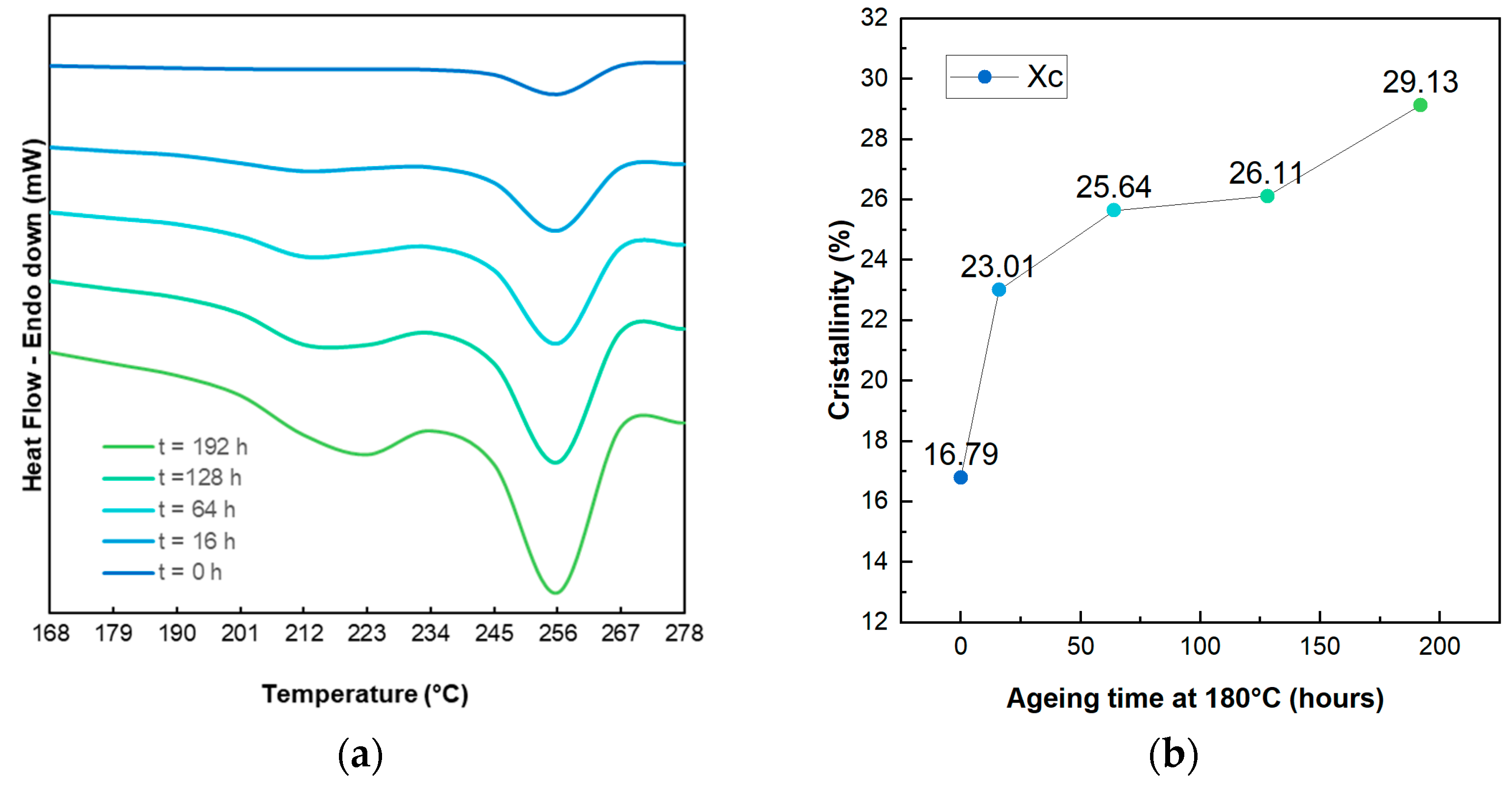

3.5. Differential Scanning Calorimetry

DSC analysis of dried PA-HF samples revealed a primary melting peak starting at approximately 246 °C and peaking at 258 °C, consistent with the material’s processing temperature of 275°C reported in the technical sheet. The enthalpy of fusion (ΔH

m) was calculated as 22.06 J/g. Using Equation 5, that accounts for the standard crystalline enthalpy for PA66 (ΔH

0m = 196 J/g) and for the solid residue fraction (f =32.96% from TGA), the crystallinity (

) of the unaged material was determined to be 16.79%.

For aged specimens reported in

Figure 5, a secondary melting peak emerged, increasing in intensity and shifting with ageing time and temperature. For example, the secondary peak temperature increased from 208 °C to 221 °C for samples aged at 180 °C for 16 to 192 hours, respectively. Similar trends were observed at other ageing temperatures when the ageing time increased, as shown in the DSC plots reported in SM. The primary melting peak, however, remained stable, ranging between 256 °C and 259 °C.

This behavior aligns with literature findings on polyamide 6,6 [

62,

63,

64] and polyamide 6,6 composites [

65,

66,

67], where thermal ageing induces microstructural changes. Oxidation and thermal exposure cause chain scission in the amorphous phase, allowing shorter chains to recrystallize into new lamellae. Initially, these newly formed lamellae have lower melting points, but prolonged ageing promotes lamellar growth, raising their melting temperature and enthalpy. Crystallinity calculations confirmed this trend, increasing from 16.79% (unaged) to 23.01% after 16 hours at 180 °C and stabilizing around 25.88% for intermediate ageing times. At 192 hours, crystallinity reached 29.13%, indicating higher chain mobility and lamellar growth during prolonged exposure.

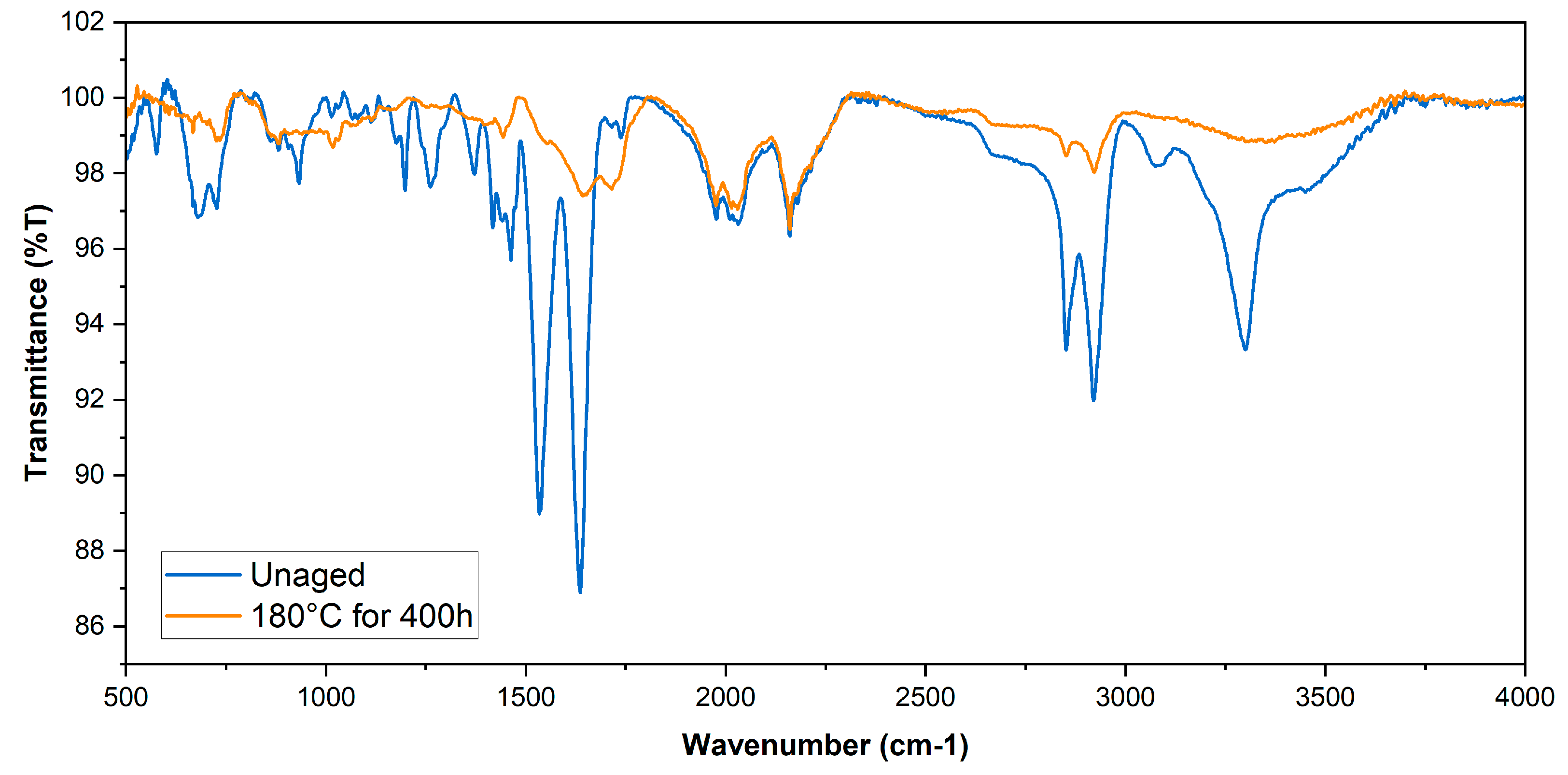

3.6. Fourier-Transform Infrared Spectroscopy

The FTIR analysis (

Figure 6) provides insight into the thermal degradation behavior of the material by comparing the spectra of aged and unaged sample. A clear reduction and broadening of the Amide I (C=O stretching ~1650 cm⁻¹) and Amide II (N-H bending ~1550 cm⁻¹) peaks in the aged spectrum suggest the breakdown of amide bonds, supporting the proposed scission of the N-alkylamide bond (CH₂-NHCO). Additionally, the slight increase in absorption around 1700–1740 cm⁻¹ indicates the formation of carbonyl-containing species, such as ketones or carboxylic acids, as a result of oxidative degradation. Further evidence lies in the broadening and reduced intensity in the 3000–3500 cm⁻¹ region.

In the unaged sample, such region exhibits two distinct peaks: the sharp band around 3300 cm⁻¹, attributed to the free N-H stretching vibrations of the amide groups, and a second band near 3080–3200 cm⁻¹, corresponding to hydrogen-bonded N-H stretching within the polyamide structure. These peaks are characteristic of the polyamide backbone, reflecting the strong hydrogen-bonding network.

Upon ageing, significant changes occur in this spectral region, including the disappearance of the two distinct peaks and the broadening of the entire band. This behavior suggests the disruption of hydrogen bonds within the polymer structure, consistent with the early stages of thermal degradation, where weaker bonds, such as the N-alkylamide bonds (CH₂-NHCO), undergo scission.

Finally, changes observed in the fingerprint region (particularly between 1200–1400 cm⁻¹) suggest modifications in C-N and C-O bonds, consistent with the fragmentation and rearrangement of the amide structure. These observations confirm that the thermal degradation at this stage involves the cleavage of weaker bonds within the polymer and the subsequent formation of secondary degradation products.

4. Conclusions

The results of this study demonstrate how the ageing process affects the structural and mechanical properties of glass fiber reinforced polyamide 6,6 with brominated flame retardants.

Ageing significantly reduces the flexural strength and strain at maximum flexural strength of the material, with longer durations and higher temperatures exacerbating this decline. Initial improvements in flexural strength at short ageing times, attributed to stress relaxation and annealing, are eventually outweighed by the effects of thermal oxidation, chain scission, and increased crystallinity.

DSC analysis revealed an increase in crystallinity with ageing, driven by chain scission in the amorphous phase and the formation of new crystalline phases. This growth in crystalline regions contributes to the observed brittleness and reduced ductility in the aged material, directly impacting its flexural properties.

FTIR analysis confirmed chemical degradation during ageing, with the appearance of carbonyl peaks indicating oxidative processes and chain scission further contributing to the embrittlement and decline in mechanical performance observed in aged specimens.

The Arrhenius-based lifetime prediction model determined an activation energy of 104.2 kJ/mol, estimating service lifetimes of approximately 25 years at 90°C but significantly shorter at 130°C. Modulated thermogravimetry revealed higher activation energy values (151 kJ/mol), reflecting differences in degradation mechanisms during accelerated ageing and thermal decomposition.

Overall, while the composite exhibits favorable long-term stability under moderate temperatures, its use high-temperature applications must be carefully evaluated, as the frequent exposure to heat spikes may severely reduce its durability.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Figure S1: TGA plot of the unaged material; Figure S2: XRF of unaged material; Figure S3: Flexural stress-strain plots at different ageing conditions; Figure S4: Optical microscope images of aged and unaged materials; Table S1: ICP analysis of PA-GF

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S. and F.M.; methodology, A.S.; validation, A.S. and M.O.; formal analysis, A.S. and F.M.; investigation, M.O. and F.M.; data curation, A.S.; writing—original draft preparation, A.S.; writing—review and editing, A.S. and G.D.; visualization, A.S.; supervision, G.D.; project administration, A.S. and M.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the members of the Materials Testing Laboratory at ABB (Bergamo), in particular Eng. Enrico Dell’Oro for providing the testing equipment and technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hriberšek, M.; Kulovec, S. Experimental Analysis of Failure Modes Depending on Different Loading Conditions Applied on Cylindrical Polyamide 66 Gears. Journal of Polymer Engineering 2024, 44, 528–541. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, D.; Park, S.K.; Yoo, Y. Flow Enhanced High-Filled Polyamide Composites without the Strength-Flowability Trade-Off. Polymer Bulletin 2024, 81, 14823–14836. [CrossRef]

- Launay, A.; Marco, Y.; Maitournam, M.H.; Raoult, I. Modelling the Influence of Temperature and Relative Humidity on the Time-Dependent Mechanical Behaviour of a Short Glass Fibre Reinforced Polyamide. Mechanics of Materials 2013, 56, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Mel’nikov, M.Y.; Seropegina, E.N. Photoradical Ageing of Polymers. Int J Polym Mater 1996, 31, 41–93. [CrossRef]

- La Mantia, F.P.; Morreale, M.; Botta, L.; Mistretta, M.C.; Ceraulo, M.; Scaffaro, R. Degradation of Polymer Blends: A Brief Review. Polym Degrad Stab 2017, 145, 79–92. [CrossRef]

- Plota, A.; Masek, A. Lifetime Prediction Methods for Degradable Polymeric Materials—A Short Review. Materials 2020, Vol. 13, Page 4507 2020, 13, 4507. [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, A.; Broughton, W.; Dean, G.; Sims, G. Review of Accelerated Ageing Methods and Lifetime Prediction Techniques for Polymeric Materials. 2005.

- White, J.R. Polymer Ageing: Physics, Chemistry or Engineering? Time to Reflect. Comptes Rendus Chimie 2006, 9, 1396–1408. [CrossRef]

- Haddar, N.; Ksouri, I.; Kallel, T.; Mnif, N. Effect of Hygrothermal Ageing on the Monotonic and Cyclic Loading of Glass Fiber Reinforced Polyamide. Polym Compos 2014, 35, 501–508. [CrossRef]

- Rajeesh, K.R.; Gnanamoorthy, R.; Velmurugan, R. Effect of Humidity on the Indentation Hardness and Flexural Fatigue Behavior of Polyamide 6 Nanocomposite. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2010, 527, 2826–2830. [CrossRef]

- Vlasveld, D.P.N.; Groenewold, J.; Bersee, H.E.N.; Picken, S.J. Moisture Absorption in Polyamide-6 Silicate Nanocomposites and Its Influence on the Mechanical Properties. Polymer (Guildf) 2005, 46, 12567–12576. [CrossRef]

- Mercier, J.; Bunsell, A.; Castaing, P.; Renard, J. Characterisation and Modelling of Ageing of Composites. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 2008, 39, 428–438. [CrossRef]

- Foulc, M.P.; Bergeret, A.; Ferry, L.; Ienny, P.; Crespy, A. Study of Hygrothermal Ageing of Glass Fibre Reinforced PET Composites. Polym Degrad Stab 2005, 89, 461–470. [CrossRef]

- Bernasconi, A.; Davoli, P.; Rossin, D.; Armanni, C. Effect of Reprocessing on the Fatigue Strength of a Fibreglass Reinforced Polyamide. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 2007, 38, 710–718. [CrossRef]

- Hagler, A.T.; Lapiccirella, A. Spatial Electron Distribution and Population Analysis of Amides, Carboxylic Acid, and Peptides, and Their Relation to Empirical Potential Functions. Biopolymers 1976, 15, 1167–1200. [CrossRef]

- Do, C.H.; Pearce, E.M.; Bulkin, B.J.; Reimschuessel, H.K. FT–IR Spectroscopic Study on the Thermal and Thermal Oxidative Degradation of Nylons. J Polym Sci A Polym Chem 1987, 25, 2409–2424. [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; Ye, L.; Yang, T. Study on the Long-term Thermal-oxidative Ageing Behavior of Polyamide 6. J Appl Polym Sci 2008, 110, 945–957. [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Gijsman, P. Influence of Temperature on the Thermo-Oxidative Degradation of Polyamide 6 Films. Polym Degrad Stab 2010, 95, 1054–1062. [CrossRef]

- Gijsman, P.; Tummers, D.; Janssen, K. Differences and Similarities in the Thermooxidative Degradation of Polyamide 46 and 66. Polym Degrad Stab 1995, 49, 121–125. [CrossRef]

- Janssen, K.; Gijsman, P.; Tummers, D. Mechanistic Aspects of the Stabilization of Polyamides by Combinations of Metal and Halogen Salts. Polym Degrad Stab 1995, 49, 127–133. [CrossRef]

- Bergeret, A.; Ferry, L.; Ienny, P. Influence of the Fibre/Matrix Interface on Ageing Mechanisms of Glass Fibre Reinforced Thermoplastic Composites (PA-6,6, PET, PBT) in a Hygrothermal Environment. Polym Degrad Stab 2009, 94, 1315–1324. [CrossRef]

- Mohd Ishak, Z.A.; Ishiaku, U.S.; Karger-Kocsis, J. Hygrothermal Ageing and Fracture Behavior of Short-Glass-Fiber-Reinforced Rubber-Toughened Poly(Butylene Terephthalate) Composites. Compos Sci Technol 2000, 60, 803–815. [CrossRef]

- Ray, B.C. Temperature Effect during Humid Ageing on Interfaces of Glass and Carbon Fibers Reinforced Epoxy Composites. J Colloid Interface Sci 2006, 298, 111–117. [CrossRef]

- Athijayamani, A.; Thiruchitrambalam, M.; Natarajan, U.; Pazhanivel, B. Effect of Moisture Absorption on the Mechanical Properties of Randomly Oriented Natural Fibers/Polyester Hybrid Composite. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2009, 517, 344–353. [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Wang, H.; Fu, K.; Ye, L. 3D Printed Continuous CF/PA6 Composites: Effect of Microscopic Voids on Mechanical Performance. Compos Sci Technol 2020, 191, 108077. [CrossRef]

- Wolfrum, J.; Eibl, S.; Lietch, L. Rapid Evaluation of Long-Term Thermal Degradation of Carbon Fibre Epoxy Composites. Compos Sci Technol 2009, 69, 523–530. [CrossRef]

- Akay, M. Moisture Absorption and Its Influence on the Tensile Properties of Glass-Fibre Reinforced Polyamide 6,6. Polymers and Polymer Composites 1994, 2, 349–354. [CrossRef]

- Valentin, D.; Paray, F.; Guetta, B. The Hygrothermal Behaviour of Glass Fibre Reinforced Pa66 Composites: A Study of the Effect of Water Absorption on Their Mechanical Properties. J Mater Sci 1987, 22, 46–56. [CrossRef]

- Ishak, Z.A.M.; Berry, J.P. Hygrothermal Ageing Studies of Short Carbon Fiber Reinforced Nylon 6.6. J Appl Polym Sci 1994, 51, 2145–2155. [CrossRef]

- Vlasveld, D.P.N.; Groenewold, J.; Bersee, H.E.N.; Picken, S.J. Moisture Absorption in Polyamide-6 Silicate Nanocomposites and Its Influence on the Mechanical Properties. Polymer (Guildf) 2005, 46, 12567–12576. [CrossRef]

- Rajeesh, K.R.; Gnanamoorthy, R.; Velmurugan, R. Effect of Humidity on the Indentation Hardness and Flexural Fatigue Behavior of Polyamide 6 Nanocomposite. Materials Science and Engineering: A 2010, 527, 2826–2830. [CrossRef]

- Ferreño, D.; Carrascal, I.; Ruiz, E.; Casado, J.A. Characterisation by Means of a Finite Element Model of the Influence of Moisture Content on the Mechanical and Fracture Properties of the Polyamide 6 Reinforced with Short Glass Fibre. Polym Test 2011, 30, 420–428. [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, P.A.; Boydell, P.; Månson, J.A.E.; Albertsson, A.C. Durability Study of Recycled Glass-Fiber-Reinforced Polyamide 66 in a Service-Related Environment. J Appl Polym Sci 1997, 65, 1631–1641. [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; Ye, L.; Yang, T. Study on the Long-Term Thermal-Oxidative Ageing Behavior of Polyamide 6. J Appl Polym Sci 2008, 110, 945–957. [CrossRef]

- Alexis, F.; Castagnet, S.; Nadot-Martin, C.; Robert, G.; Havet, P. Effect of Severe Thermo-Oxidative Ageing on the Mechanical Behavior and Fatigue Durability of Short Glass Fiber Reinforced PA6/6.6. Int J Fatigue 2023, 166, 107280. [CrossRef]

- Yarar, E.; Şahin, A.E.; Kara, H.; Çep, E.B.; Bora, M.Ö. Thermal Ageing Effect on Mechanical Properties of Polyamide 6 Matrix Composites Produced by TFP and Compression Molding. Polym Compos 2024, 45. [CrossRef]

- Sahin, A.E.; Yarar, E.; Kara, H.; Cep, E.B.; Bora, M.O.; Yilmaz, T. Thermal Ageing Effect of Polyamide 6 Matrix Composites Produced by Tailor Fiber Placement (TFP) under Compression Molding on Sliding Wear Properties. Polym Compos 2024, 45, 98–110. [CrossRef]

- Rudzinski, S.; Häussler, L.; Harnisch, C.H.; Mäder, E.; Heinrich, G. Glass Fibre Reinforced Polyamide Composites: Thermal Behaviour of Sizings. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 2011, 42, 157–164. [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, P.A.; Albertsson, A.C.; Boydell, P.; Månson, J.A.E. Durability of In-Plant Recycled Glass Fiber Reinforced Polyamide 66. Polym Eng Sci 1998, 38, 348–356. [CrossRef]

- Ksouri, I.; De Almeida, O.; Haddar, N. Long Term Ageing of Polyamide 6 and Polyamide 6 Reinforced with 30% of Glass Fibers: Physicochemical, Mechanical and Morphological Characterization. Journal of Polymer Research 2017, 24, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Bergeret, A.; Pires, I.; Foulc, M.P.; Abadie, B.; Ferry, L.; Crespy, A. The Hygrothermal Behaviour of Glass-Fibre-Reinforced Thermoplastic Composites: A Prediction of the Composite Lifetime. Polym Test 2001, 20, 753–763. [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Ye, L.; Li, G. Long-Term Hydrothermal Ageing Behavior and Ageing Mechanism of Glass Fibre Reinforced Polyamide 6 Composites. Journal of Macromolecular Science, Part B 2018, 57, 67–82. [CrossRef]

- Khakbaz, H.; Basnayake, A.P.; Harikumar, A.K.A.; Firouzi, M.; Martin, D.; Heitzmann, M. Tribological and Mechanical Characterization of Glass Fiber Polyamide Composites under Hydrothermal Ageing. Polym Degrad Stab 2024, 227, 110870. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Hou, Z.; Yang, Y. A Study on the Ageing Resistance of Injection-Molded Glass Fiber Thermoplastic Composites. Fibers and Polymers 2022, 23, 502–514. [CrossRef]

- Arif, M.F.; Meraghni, F.; Chemisky, Y.; Despringre, N.; Robert, G. In Situ Damage Mechanisms Investigation of PA66/GF30 Composite: Effect of Relative Humidity. Compos B Eng 2014, 58, 487–495. [CrossRef]

- Autay, R.; Njeh, A.; Dammak, F. Effect of Thermal Ageing on Mechanical and Tribological Behaviors of Short Glass Fiber–Reinforced PA66. Journal of Thermoplastic Composite Materials 2020, 33, 501–515. [CrossRef]

- Chaichanawong, J.; Thongchuea, C.; Areerat, S. Effect of Moisture on the Mechanical Properties of Glass Fiber Reinforced Polyamide Composites. Advanced Powder Technology 2016, 27, 898–902. [CrossRef]

- El-Mazry, C.; Correc, O.; Colin, X. A New Kinetic Model for Predicting Polyamide 6-6 Hydrolysis and Its Mechanical Embrittlement. Polym Degrad Stab 2012, 97, 1049–1059. [CrossRef]

- Eftekhari, M.; Fatemi, A. Tensile Behavior of Thermoplastic Composites Including Temperature, Moisture, and Hygrothermal Effects. Polym Test 2016, 51, 151–164. [CrossRef]

- Sang, L.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Wei, Z. Thermo-Oxidative Ageing Effect on Mechanical Properties and Morphology of Short Fibre Reinforced Polyamide Composites – Comparison of Carbon and Glass Fibres. RSC Adv 2017, 7, 43334–43344. [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Gijsman, P. Influence of Temperature on the Thermo-Oxidative Degradation of Polyamide 6 Films. Polym Degrad Stab 2010, 95, 1054–1062. [CrossRef]

- Jung, W.Y.; Weon, J. Il Characterization of Thermal Degradation of Polyamide 66 Composite: Relationship between Lifetime Prediction and Activation Energy. Polymer (Korea) 2012, 36, 712–720. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Tong, L.; Fang, Z.; Gu, A.; Xu, Z. Thermal Degradation Behavior of Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes/Polyamide 6 Composites. Polym Degrad Stab 2006, 91, 2046–2052. [CrossRef]

- Blaine, R.L.; Hahn, B.K. Obtaining Kinetic Parameters by Modulated Thermogravimetry. J Therm Anal Calorim 1998, 54, 695–704. [CrossRef]

- Bhuiyan, A.L. Some Thermodynamic Aspects of the Thermal Degradation of Wholly Aromatic Polyamides. Eur Polym J 1983, 19, 195–198. [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, M.; Jurasek, P.; Hayashi, J.; Furimsky, E. Formation of Toxic Gases during Pyrolysis of Polyacrylonitrile and Nylons. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis 1995, 35, 43–51. [CrossRef]

- Levchik, S. V.; Costa, L.; Camino, G. Effect of the Fire-Retardant Ammonium Polyphosphate on the Thermal Decomposition of Aliphatic Polyamides. Part III—Polyamides 6.6 and 6.10. Polym Degrad Stab 1994, 43, 43–54. [CrossRef]

- Ballistreri, A.; Garozzo, D.; Giuffrida, M.; Montaudo, G. Mechanism of Thermal Decomposition of Nylon 66. Macromolecules 1987, 20, 2991–2997. [CrossRef]

- Sheng-Long, T.; Lian-Xin, M.; Xiao-Guang, S.; Xu-Dong, T. Thermolysis Parameter and Kinetic Research in Copolyamide 66 Containing 2-Carboxyethyl Phenyl Phosphinic Acid. High Perform Polym 2015, 27, 65–73. [CrossRef]

- Herrera, M.; Matuschek, G.; Kettrup, A. Main Products and Kinetics of the Thermal Degradation of Polyamides. Chemosphere 2001, 42, 601–607. [CrossRef]

- Azimi, H.; Abedifard, P. Determination of Activation Energy during the Thermal Degradation of Polyamide 66/Glass Fiber Composites. Journal of Thermoplastic Composite Materials 2020, 33, 956–966. [CrossRef]

- Pliquet, M.; Rapeaux, M.; Delange, F.; Bussiere, P.O.; Therias, S.; Gardette, J.L. Multiscale Analysis of the Thermal Degradation of Polyamide 6,6: Correlating Chemical Structure to Mechanical Properties. Polym Degrad Stab 2021, 185, 109496. [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, P.-A.; Boydell, P.; Eriksson, K.; Må Nson, J.-A.E.; Albertsson, A.-C. Effect of Thermal-Oxidative Ageing on Mechanical, Chemical, and Thermal Properties of Recycled Polyamide 66. J Appl Polym Sci 1997, 65, 1619–1630. [CrossRef]

- Bell, J.P.; Slade, P.E.; Dumbleton, J.H. Multiple Melting in Nylon 66. Journal of Polymer Science Part A-2: Polymer Physics 1968, 6, 1773–1781. [CrossRef]

- Rudzinski, S.; Häussler, L.; Harnisch, Ch.; Mäder, E.; Heinrich, G. Glass Fibre Reinforced Polyamide Composites: Thermal Behaviour of Sizings. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf 2011, 42, 157–164. [CrossRef]

- Beyer, F.L.; Napadensky, E.; Ziegler, C.R. Characterization of Polyamide 66 Obturator Materials by Differential Scanning Calorimetry and Size-Exclusion Chromatography; 2005;

- Thanki, P.N.; Ramesh, C.; Singh, R.P. Photo-Irradiation Induced Morphological Changes in Nylon 66. Polymer (Guildf) 2001, 42, 535–538. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).