1. Introduction

As global climate change intensifies, the environmental responsibility of the construction industry is becoming increasingly evident, given its substantial contribution to global carbon emissions and resource consumption. Statistical data indicates that the building and construction industry is responsible for approximately 40% of global energy consumption, while contributing approximately 30% of CO2 emissions. The operational phases of buildings, such as heating, cooling, ventilation, and lighting, represent the primary source of energy consumption. This elevated consumption and emission rate not only has a direct impact on climate change but also exerts considerable pressure on global issues such as resource depletion and ecological imbalance [

1]. Furthermore, the rapid urbanisation and global population growth that have occurred in recent decades have resulted in a corresponding increase in demand for resources. This has led to a significant rise in the consumption of energy, materials and land, which in turn is causing long-term damage to the natural environment. In light of these challenges, it is imperative that sustainability goals in the construction industry adopt a holistic approach to optimisation, encompassing the entire design and management process, rather than focusing on isolated improvements [

2].

The conventional models of building design and management are constrained in their ability to effectively address the intricate challenges that arise in this field. Firstly, the traditional model is reliant on pre-set fixed parameters or manual monitoring, which is challenging to align with the dynamic energy demand. Given the frequent changes in climate, seasons, building usage, and human activities, there is a considerable degree of uncertainty in energy demand. Traditional management methods are unable to adjust the system in real time to adapt to the rapidly changing environment, resulting in the inefficient use of resources [

3]. Secondly, traditional building design tends to prioritise short-term costs and functionality, with a consequent disregard for energy efficiency and environmental impact over the life cycle of the building. In the context of the growing scarcity of resources, the improvement of resource efficiency in buildings and the reduction of energy consumption have become the central objectives of the global construction industry [

4]. It is therefore imperative that an efficient, intelligent and flexible sustainable building system is constructed which can be dynamically regulated according to real-time data and which balances the use of resources and user comfort.

Recent advancements in sustainable building research have focused on areas such as green materials, energy-saving technologies, and intelligent energy management systems. For example, low-carbon cement, recycled wood, and energy-efficient glass are increasingly used to reduce the carbon footprint of buildings [

5]. Energy-saving technologies, like solar panels, wind energy systems, and LED lighting, have also helped decrease direct energy consumption. However, these solutions often target individual aspects of buildings and lack coordination across systems. True building sustainability requires a holistic approach, integrating energy management, data monitoring, equipment control, and user behavior to create a fully optimized building ecosystem.

2. Related Work

Ben-Nakhi and Mahmoud employed a General Regression Neural Network (GRNN) to predict cooling loads for commercial buildings [

6]. Their findings demonstrated that a well-designed GRNN could accurately predict a building’s cooling load based solely on external temperature. Similarly, Ekici and Aksoy utilized a Back Propagation Neural Network (BPNN) to estimate the heating energy requirements of three distinct buildings [

7]. Their research validated the reliability and accuracy of BPNN in predicting building heating loads. Yokoyama et al. also applied BPNN for cooling demand prediction in buildings, incorporating a global optimization technique called "Modal Trimming Method" to optimize model parameters and enhance predictive performance [

8]. The SVM method is appropriate for small-scale data sets; however, there are limitations in large-scale environments. The random forest (RF) method has been demonstrated to be effective in the context of high-dimensional data; however, it has been observed to exhibit accuracy issues in scenarios characterised by extreme climatic conditions.

Li and colleagues utilized Support Vector Regression (SVR) to predict the hourly cooling load of an office building [

9]. Input parameters such as outdoor dry bulb temperature, relative humidity, and solar radiation intensity were incorporated to improve prediction accuracy. Similarly, Massana et al. [

10] applied SVR, along with multiple linear regression and artificial neural networks, to forecast short-term loads for non-residential buildings. Deep neural networks (DNNs) demonstrate efficacy in processing complex data, however, they are characterised by high computational costs.

3. Methodologies

3.1. Multi-Source Feature Extraction and Fusion

The intelligent prediction module employs long short-term memory neural networks to forecast the energy consumption of buildings and make adjustments in real-time based on environmental and historical data. The module initially collates a series of real-time data points, including temperature, humidity, air quality, human activity, and so forth, in order to construct a characteristic sequence of energy demand. The input data set, designated

, comprises all environmental and operational data at a given time point

. Each data point within this set includes a range of variables, including temperature

, humidity

, air quality index

, and human activity level

. The latter is expressed as Equation (1).

Subsequently, the data sequence is fed into the LSTM network. The LSTM network employs a three-layer gating structure comprising a forgetting gate, an input gate, and an output gate, represented as

,

, and

, respectively. These gates are utilized to process historical information and current inputs, as illustrated in Equation 2,3,4:

where

and

represent the weight and bias parameters, respectively. The term

denotes the previous hidden state, while the term

signifies the current input. Finally, the term

denotes the activation function. The state update formula of the LSTM network is responsible for transforming data series into predicted outputs. Predicted energy demand value for each step is expressed as

, as illustrated in Equation 5.

The objective of the prediction process is to minimise the prediction error. Therefore, the loss function is set to mean square error (

), which is given by Equation 6.

The objective of this loss function is to optimise the model parameters in order to enhance the accuracy of the prediction and guarantee that the model is capable of precise dynamic adjustment when there is a significant fluctuation in energy demand.

3.2. Deep Learning Diagnostics

The dynamic control module employs a reinforcement learning (

) strategy to enable real-time adjustment of the building energy system and environmental control system, thereby reducing energy consumption and maintaining user comfort. The state of reinforcement learning is represented by

, and the action is represented by

. Adjustments to the built environment are made at time

, which may include modifications to the

system design or adjustments to the lighting. The objective of the model is to optimise the cumulative reward,

, as defined by Equation 7.

where the weighted parameters,

,

and

, serve to balance the conflicting objectives of energy efficiency, user comfort and environmental benefits.

The control strategy is updated by the strategy gradient method of reinforcement learning, with the objective of optimising the expected cumulative reward,

, where

represents the strategy parameter. The formula for strategy gradient is as Equation 8.

The dynamic control module is not only dependent on real-time data; it also incorporates climate prediction data

and energy price data

in order to optimise the selection of actions at a given time point

, as illustrated by Equation 9.

The -learning variant algorithm is employed to identify the optimal action in the continually updated state-action value table, thereby enabling the control system to demonstrate high adaptability in the context of a complex building environment.

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setups

The dataset employed in the experiment was derived from the ASHRAE Great Energy Predictor III dataset, published by the ASHRAE Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers. The dataset comprises comprehensive energy consumption and environmental data from a range of commercial buildings, encompassing external meteorological conditions and internal building parameters. A three-layer fully connected neural network was employed, with each layer comprising 128 neurons. The rationale behind the selection of a three-layer structure is based on the following considerations: an analysis of existing literature indicates that a three-layer neural network architecture can provide an optimal balance in the task of predicting the energy efficiency of buildings. This approach can not only capture sufficient nonlinear features, but also avoid the problem of overfitting. In order to prevent overfitting, a dropout layer with a 0.2 dropout rate is added after each layer of the model. The loss function employs the mean square error as the loss function, the optimiser is set to Adam, and the learning rate is set to 0.001.

4.2. Experimental Analysis

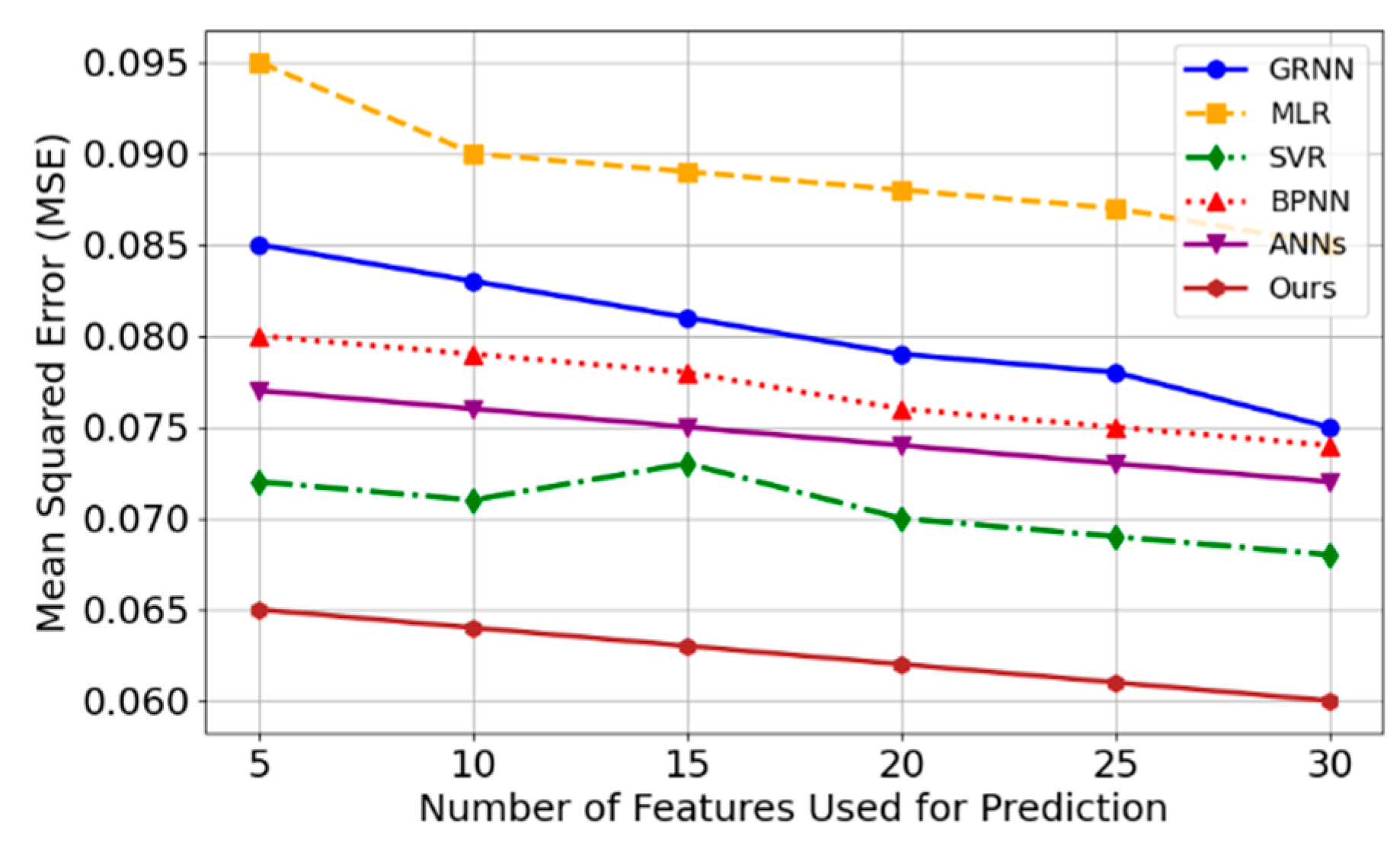

The graph illustrates a comparison of the mean square error (MSE) of disparate prediction methodologies when utilising varying numbers of features. The mean square error (MSE) is employed as an evaluation index to quantify the average discrepancy between the predicted and actual values. A lower MSE value indicates a higher level of prediction accuracy for the model. As illustrated in the figure, the MSE of each method declines progressively with the augmentation of the number of features, thereby substantiating the assertion that an increased number of features is conducive to enhancing the prediction accuracy. The "Ours" method demonstrates the lowest MSE across all feature sets, thereby substantiating its efficacy in energy consumption prediction.

Figure 1.

MSE Comparison for Different Methods.

Figure 1.

MSE Comparison for Different Methods.

The reduction in MSE is a direct reflection of the enhanced precision of building energy efficiency forecasting, which signifies that buildings are capable of more accurately anticipating energy demand and making corresponding adjustments. In practice, this increase in accuracy can result in notable improvements in energy efficiency and cost savings. To illustrate, in a commercial office building, the air conditioning system can be made to adapt in real time to the energy demand by utilising an enhanced energy efficiency prediction model.

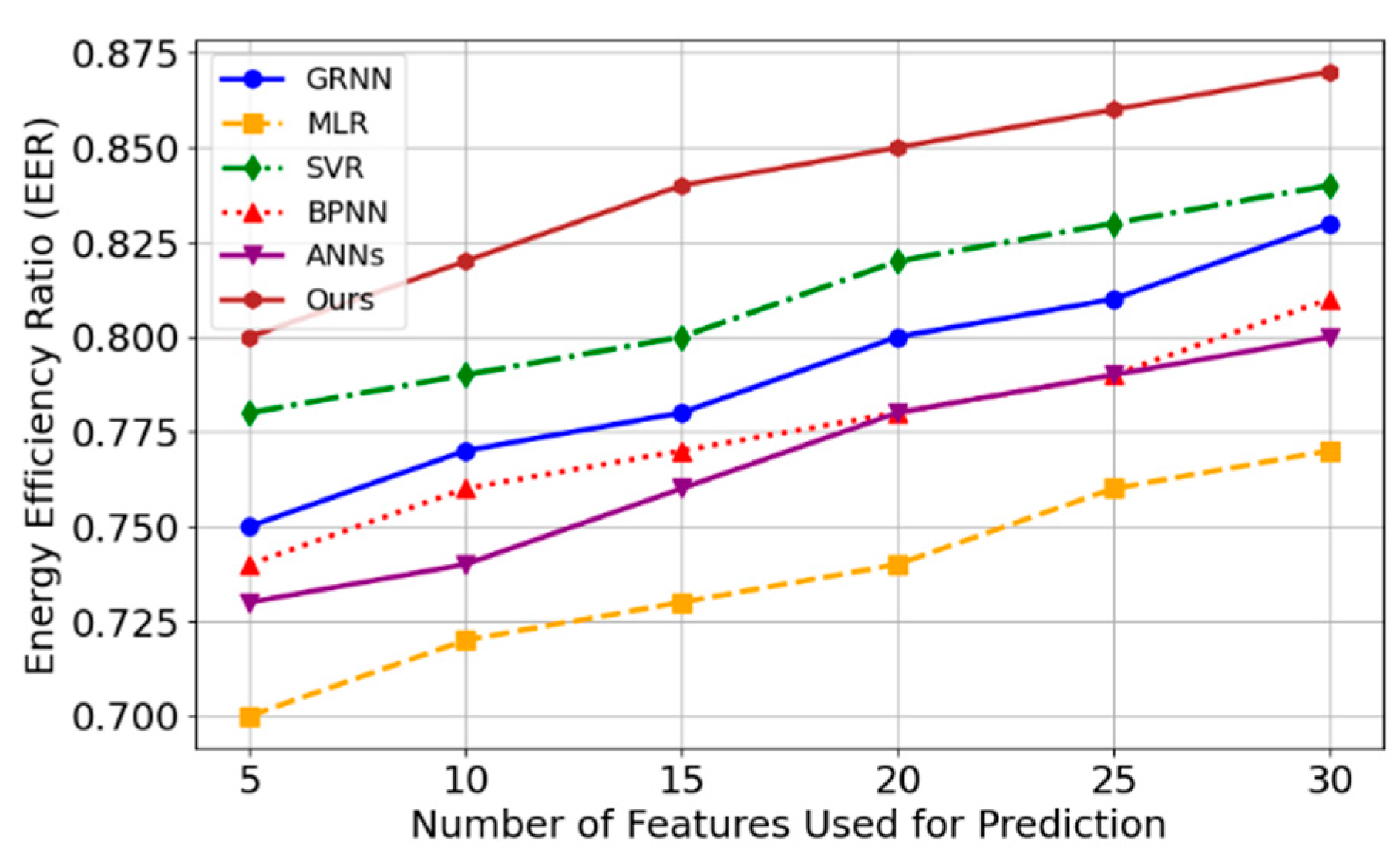

Figure 2 depicts a comparison of energy efficiency ratios (EER) between disparate methodologies when utilising varying numbers of features. The number of features with disparate predictive outcomes is fixed, and the evaluation metric is the EER value, which reflects the efficacy of each method in terms of energy efficiency. The "Ours" method exhibits the highest EER value for all features, thereby demonstrating its notable efficacy in enhancing energy efficiency.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, this study demonstrates the considerable benefits of energy management and environmental regulation in sustainable buildings through the construction of a multi-level AI model. The experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method exhibits superior performance in terms of mean square error and energy efficiency ratio evaluation index when compared to the traditional method. This evidence substantiates the assertion that the proposed method is more accurate in predicting energy consumption and is more effective in reducing energy expenditure. The model employs a long short-term memory network to forecast energy demand and integrates reinforcement learning algorithms to enable real-time and intelligent dynamic control. Further research could investigate the potential for integrating the AI technology employed in this study into existing building management systems (BMS). This necessitates not only the optimisation of algorithms but also a consideration of the compatibility and integration difficulty of existing systems.

References

- Waqar, A.; et al. Applications of AI in oil and gas projects towards sustainable development: a systematic literature review. Artificial Intelligence Review 2023, 56, 12771–12798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, A.K.; Choudhary, S.K.; Singh, V.K. How can artificial intelligence impact sustainability: A systematic literature review. Journal of Cleaner Production 2022, 376, 134120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalov, F.; Calonge, D.S.; Gurrib, I. New era of artificial intelligence in education: Towards a sustainable multifaceted revolution. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bokhari, S.A.A.; Myeong, S. Use of artificial intelligence in smart cities for smart decision-making: A social innovation perspective. Sustainability 2022, 14, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, T.; Yin, S.; Zhang, N. The interaction mechanism and dynamic evolution of digital green innovation in the integrated green building supply chain. Systems 2023, 11, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Nakhi, A.E.; Mahmoud, M.A. Cooling load prediction for buildings using general regression neural networks. Energy Conversion and Management 2004, 45, 2127–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekici, B.B.; Aksoy, U.T. Prediction of building energy consumption by using artificial neural networks. Advances in Engineering Software 2009, 40, 356–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokoyama, R.; Wakui, T.; Satake, R. Prediction of energy demands using neural network with model identification by global optimization. Energy Conversion and Management 2009, 50, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; et al. Applying support vector machine to predict hourly cooling load in the building. Applied Energy 2009, 86, 2249–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massana, J.; et al. Short-term load forecasting in a non-residential building contrasting models and attributes. Energy and Buildings 2015, 92, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).