1. Introduction

Nanotwinned metals with twin boundaries (TBs) inside ultrafine grains usually demonstrate an excellent combination of ultrahigh strength and good tensile ductility, compared to their twin-free nanocrystalline counterparts [

1,

2,

3]. These excellent mechanical properties are associated with their unique deformation mechanism [

4]. Thus, the mechanical behavior and deformation mechanism of nanotwinned metals have attracted extensive attentions in recent years.

Many experiments and theoretical studies have demonstrated that the classical Hall-Petch behavior of material strengthening with reduced twin spacing λ is broken below a critical spacing λc, that is the Hall-Petch breakdown or softening [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16]. Lu et al. [

5] synthesized different nanotwinned Cu samples with twin spacing varying from 94 nm down to 4 nm. The observations showed that its strength first increases as the twin spacing decreases, reaching a maximal strength at λ = 15 nm, then decreases as λ is further reduced. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations [

6] and theoretical calculations [

7] showed that the strengthening-softening transition originates from the competition between dislocations inclined to TBs with those parallel to TBs, and the critical twin spacing λc depends on grain size d. Then Wei [

8] further obtained the scaling law

∝ d

1/2 based on the twin spacing-dependent plasticity model. Moreover, this strengthening-softening transition with the reduction of twin spacing has been observed in numerous metals and alloys [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16].

In contrast, the unconventional continuous strengthening has been recently reported in some nanotwinned metals [

17,

18,

19]. The experimental observation in columnar-grained nanotwinned Ni showed that the continuous strengthening can be extended to an extremely fine TB spacing [

17]. The transmission electron microscopy (TEM) revealed that this continuous strengthening arises from the excellent stability of TBs and their strong impedance to dislocation motion. The continuous strengthening was also reported in nanotwinned (CoCrFeMn)

1-xNi

x high-entropy alloys at Ni concentration below 44% [

18], and it arises from the FCC-to-HCP martensite transformation. Furthermore, the MD simulation by Mousavi et al. [

19] has shown that there exists a critical temperature in the nanotwinned Pd and Cu, below which the continuous strengthening occurs, while above which the strengthening-softening transition occurs. This continuous strengthening is driven by the stress concentration at the intersections of TBs and grain boundaries (GBs), which decreases with the reduction of twin spacing.

AgPd alloy is a widely used alloy in industries such as electronic communication, automotive and aviation, as well as new medical fields, with good corrosion resistance, conductivity, and high temperature resistance. The mechanical properties of materials are often closely related to their microstructure, and adding twinning to the material structure has become one of the ways to improve the comprehensive mechanical properties of materials. In this study, we investigate the effect of twin spacing and tenperature on the mechanical behavior and deformation mechanism of nanotwinned AgPd alloy by MD simulation. The paper is structured as follows: The methods of the model establishment and the simulation details are given in

Section 2. The simulation results are discussed in

Section 3 The conclusions are made in

Section 4.

2. Computational Method

In order to systematically study the TB spacing and temperature deformation mechanism of nanotwinned AgPd alloys, equiaxed models with different TB spacing and average grain size were established. This section introduces the construction of the model, simulation details, and methods for analyzing simulation.

The Voronoi tessellation method embedded in Atomsk [

20] was used to generate polycrystalline silver palladium alloy model. The twin-free and twin-containing equiaxed-grained samples with specific atomic ratios were constructed according to the methods of Hua et al. [

21] and Yan et al. [

22]. To obtain the simulation model for the twin-free equiaxed-grained Ag

0.5Pd

0.5 samples, the equiaxed-grained pure Pd models were established at first, then the Pd atoms in the pure Pd models were randomly replaced with Ag to obtain the target composition. For the equiaxed-grain Ag

0.5Pd

0.5 sample with different TB spacings, the nanotwinned Pd models were first established and then the atoms were randomly replaced in a similar way as used for twin-free Ag

0.5Pd

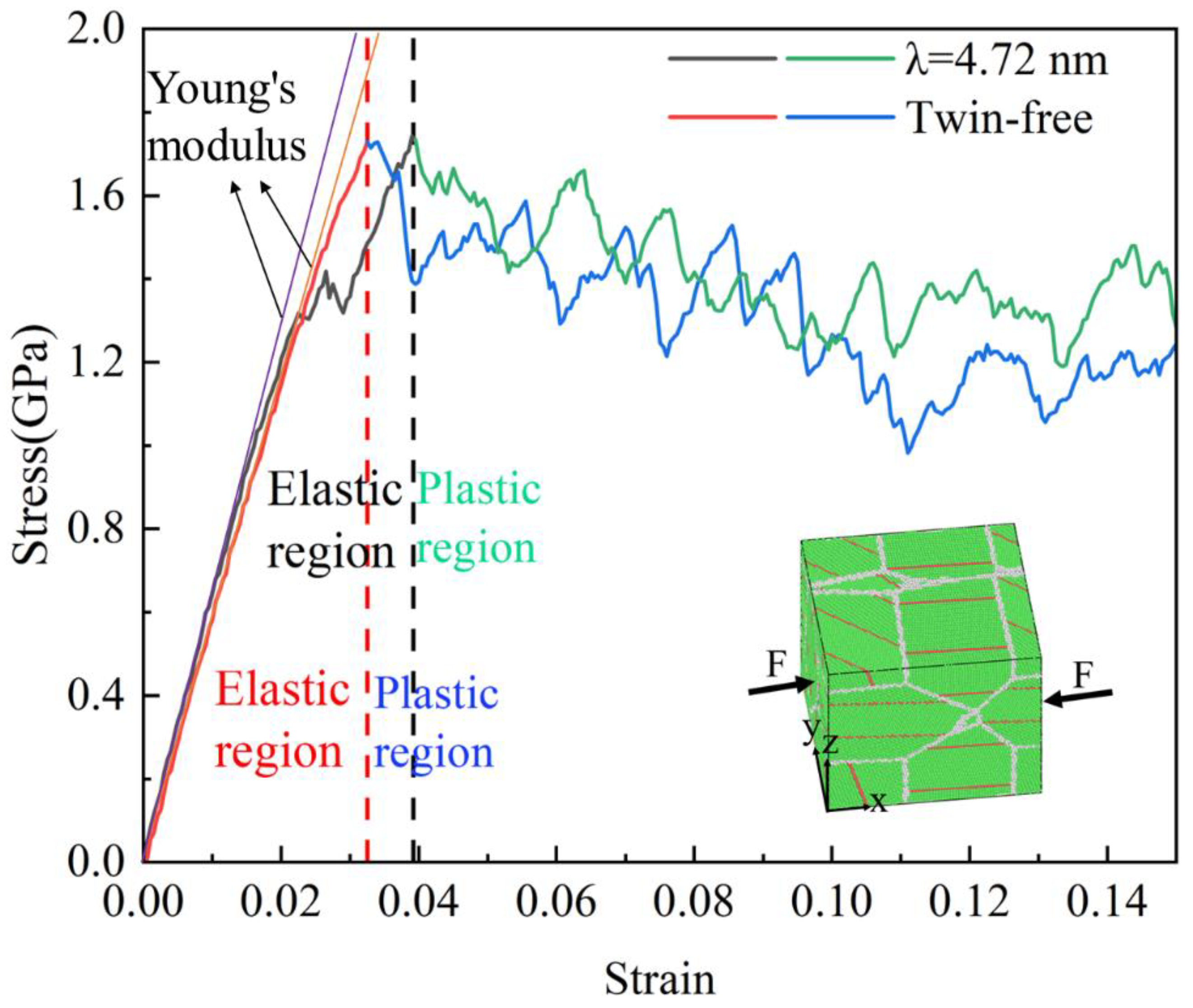

0.5 alloy models to get the target atoms ratio. Fig 1 shows the stress-strain curve of a silver palladium nanoalloy with an average grain size of 11.00 nm. Compared to the nano polycrystalline silver palladium alloy without twinning structure, the alloy with twinning has differences in elastic-plastic transformation and average flow stress, lagging behind the elastic-plastic transformation and increasing the average flow stress.

Table 1 provides the initial configuration related parameters for model sizes of 25 nm × 25 nm × 25 nm, 20 nm × 20 nm × 20 nm, 15 nm × 15 nm × 15 nm, 10 nm × 10 nm × 10 nm, respectively. In the sample with grain size d = 5.50 nm, the largest twin spacing is λ = 4.04 nm due to the small grain size.

The large-scale atomistic/molecular massively parallel simulator (LAMMPS) [

23] is used for conducting MD simulation. The motion equations are solved by velocity-Verlet [

24] algorithm with a time step of 1 fs. The accuracy and reliability of MD simulation results are dependent on the utilized interatomic potential. The embedded atom model (EAM) potential developed by Hale et al. [

25] is used to describe the interaction between atoms in nanotwin AgPd alloy, and the interatomic interaction potential can is given as the following

Here, EC is the cohesive energy, N is the total number of atoms, is the atomic spacing between atoms i and j, is the embedding energy function for atom i, is the electron density function for atom j and is the pair interaction function between atoms i and j. is the total electron density felt by atom i from all other atoms j. EAM places no limitations on the exact mathematical expressions used for the three functions F, ρ and , but practice and theory point to particular characteristic forms for each. It can correctly reflect the thermodynamic, dynamics and microstructural properties of AgPd alloy system.

Figure 1.

Stress-strain curve of silver palladium nanoalloy with an average grain size of 11.00nm.

Figure 1.

Stress-strain curve of silver palladium nanoalloy with an average grain size of 11.00nm.

At the beginning of simulation, each initial configuration is isothermally relaxed for 50 ps at 300 K to obtain equilibrium configurations using Nose–Hoover thermostat [

26,

27]. Subsequently, these nanotwinned samples are axially loaded at a strain rate of 1.0 × 10

8 s

-1 along the x-axis at 300 K. Periodic boundary conditions are imposed along three coordinate axes. In order to study the effect of temperature on the deformation behavior of nanocrystalline polycrystalline AgPd alloys with different twin spacing, a configuration with an average grain size of 11.00 nm was selected, and the selected temperatures were 10 K, 100 K, 300 K, and 500 K. Set the relaxation temperature at 10 K, 100 K, 300 K, and 500 K to relax for 50 ps and load at the corresponding temperature, with a strain rate of 5.0 × 10

8 s

-1.

The free Open Visualization Tool (OVITO) [

28] was used to analyze the simulation results. The CNA module and DXA module in OVITO were employed to visualize the atomic configuration. In this study, atoms were colored based on CNA: green for FCC atoms, red for hexagonal close-packed (HCP) atoms, blue for body-centered cubic (BCC) atoms, and white for unknown atoms. In OVTIO analysis, one layer of HCP structure atomic plane represents twin boundary (TB), two adjacent HCP structure atomic planes represent intrinsic stacking fault (ISF), and there is an FCC structure atomic plane between the two HCP structure atomic planes representing extrinsic stacking fault (ESF), with three or more HCP structure atomic planes representing HCP phase. Blue, green, magenta, yellow, and light blue lines represent all dislocation lines, Shockley, Stair rod, Hirth, and Frank dislocation lines, respectively.

4. Conclusions

This paper simulates the compression deformation process of nanocrystalline polycrystalline AgPd alloys with different twin spacing using molecular dynamics methods, and explores the effects of twin spacing, deformation temperature, and strain rate on the mechanical properties and deformation mechanism of AgPd alloys during deformation. The results show that:

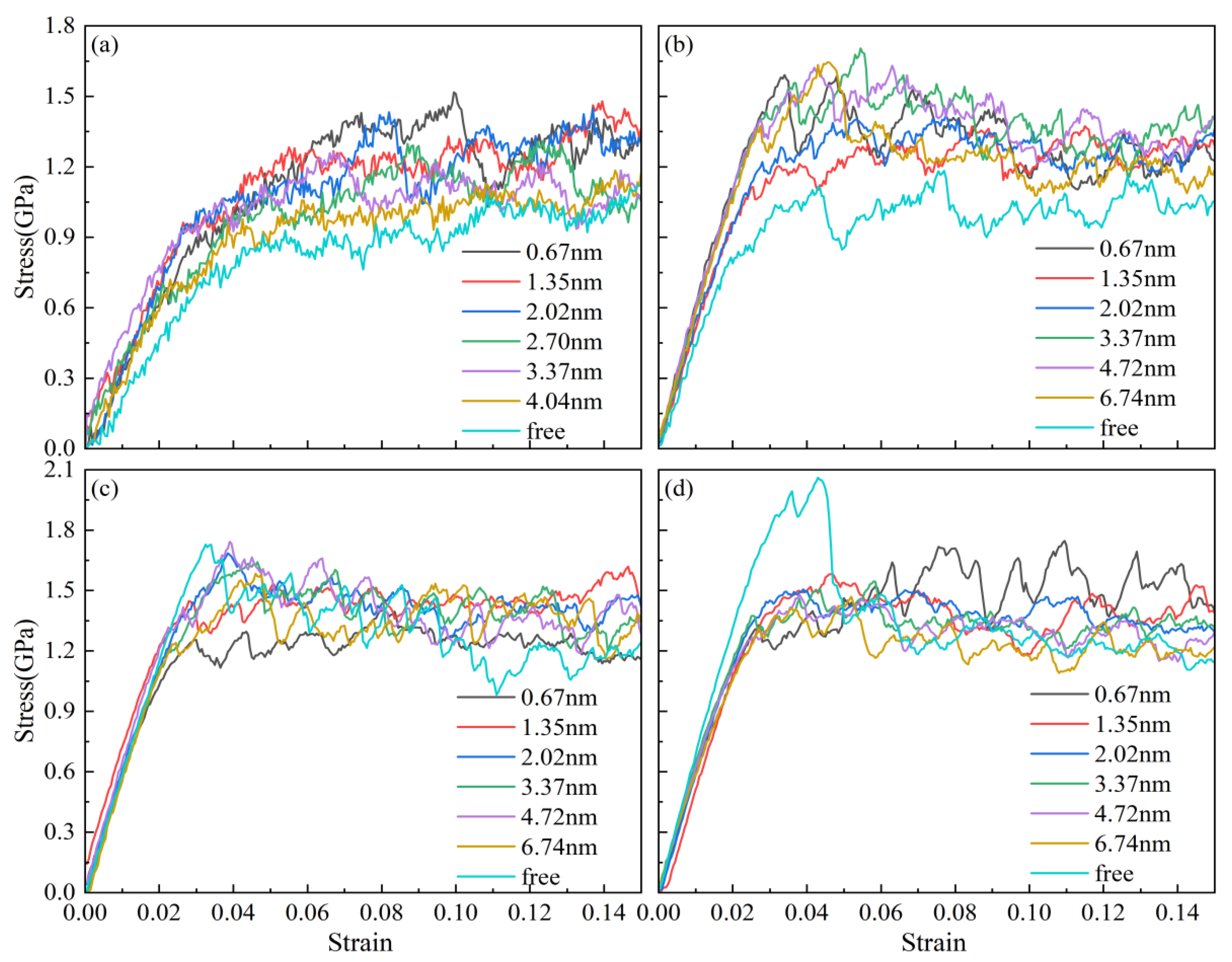

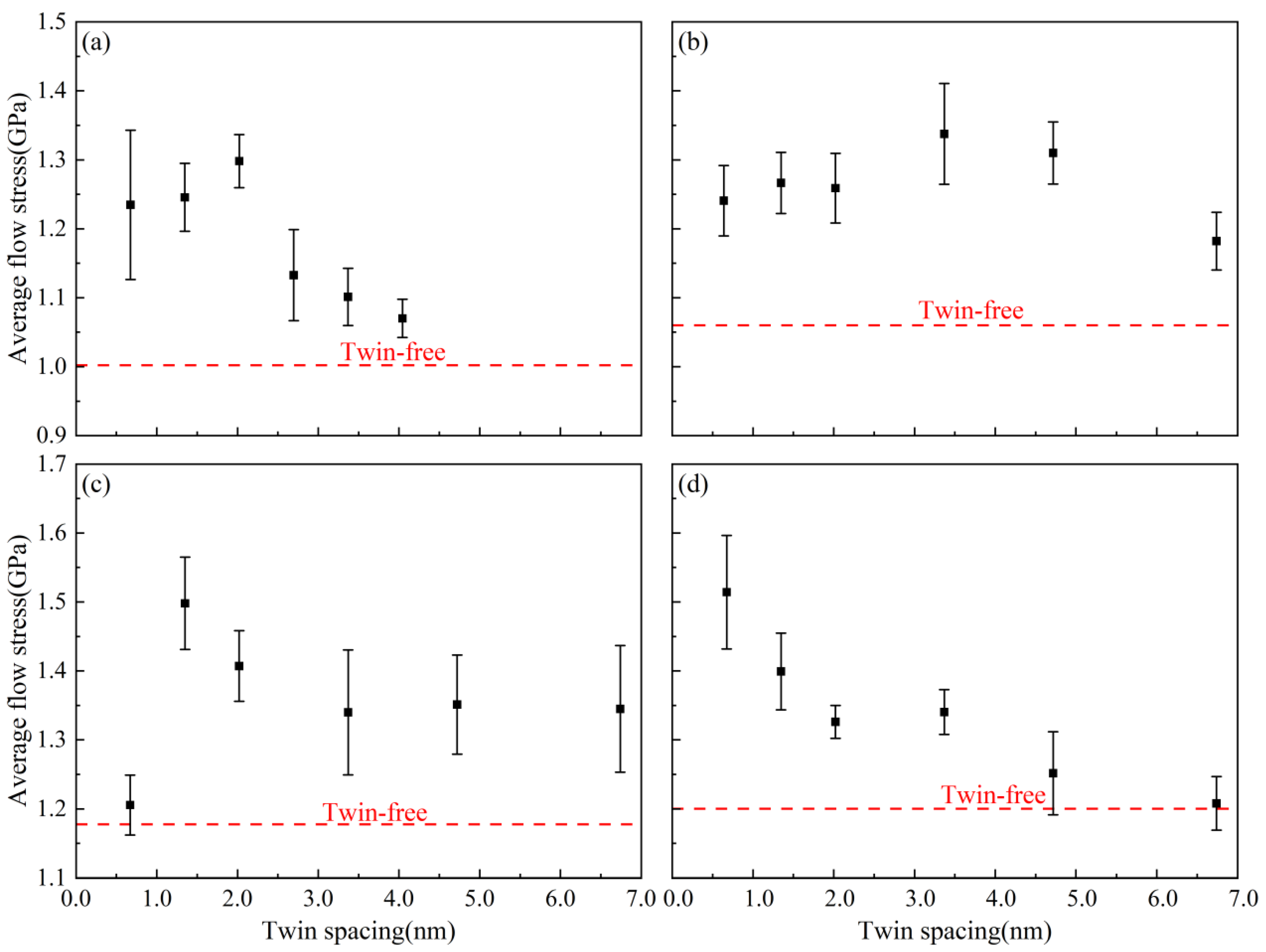

(1) The average flow stress of nanotwin AgPd alloys with average grain sizes of 5.50 nm, 8.24 nm, and 11.00 nm increases first and then decreases with the decrease of twinning spacing. Among them, the alloy with average grain size of 11.00 nm increases and then decreases with the decrease of twinning spacing λ= The average flow stress at 1.35 nm reaches its maximum value; The average flow stress of the nanotwin AgPd alloy with an average grain size of 13.76 nm continued to increase with the decrease of twin spacing, and there was no turning trend. The average flow stress of nanocrystalline polycrystalline AgPd alloy with added twin structure is higher than that without twin structure. During the deformation process of a nanotwin AgPd alloy with an average grain size of 11.00 nm, the alloy with a twin spacing of 0.67 nm experiences a phenomenon of "de twinning"; The alloy with a twin spacing of 6.74 nm exhibits new twin structures and V-shaped secondary twinning.

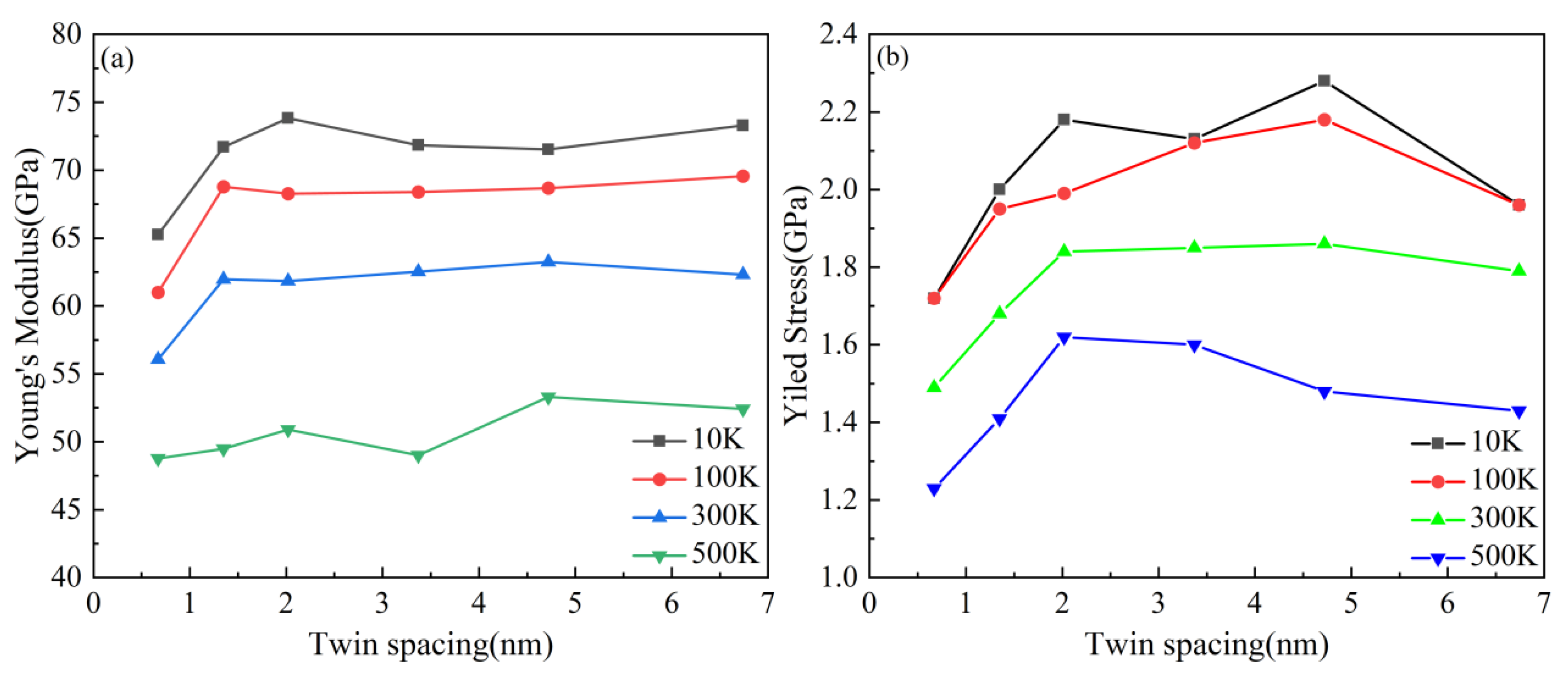

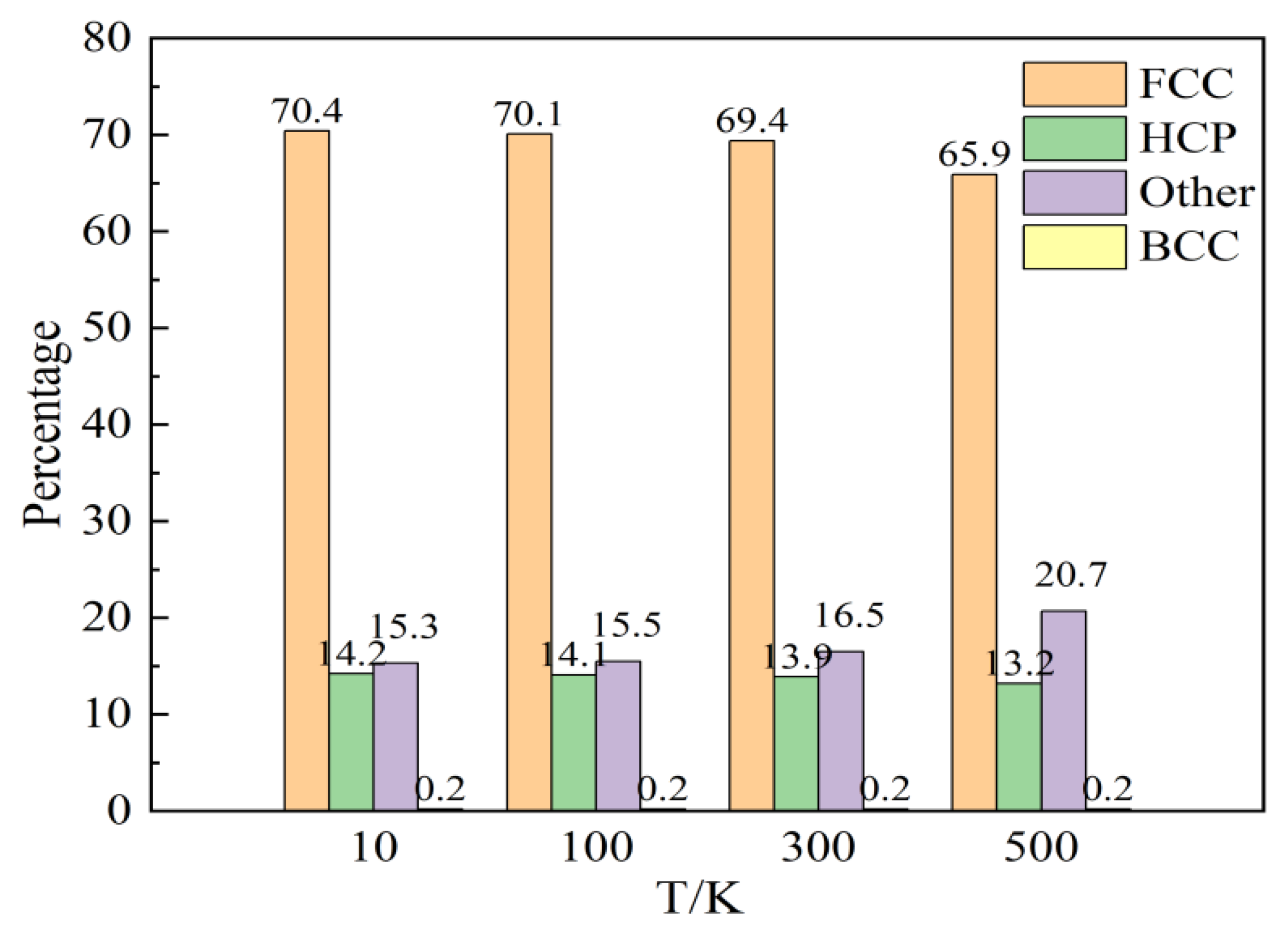

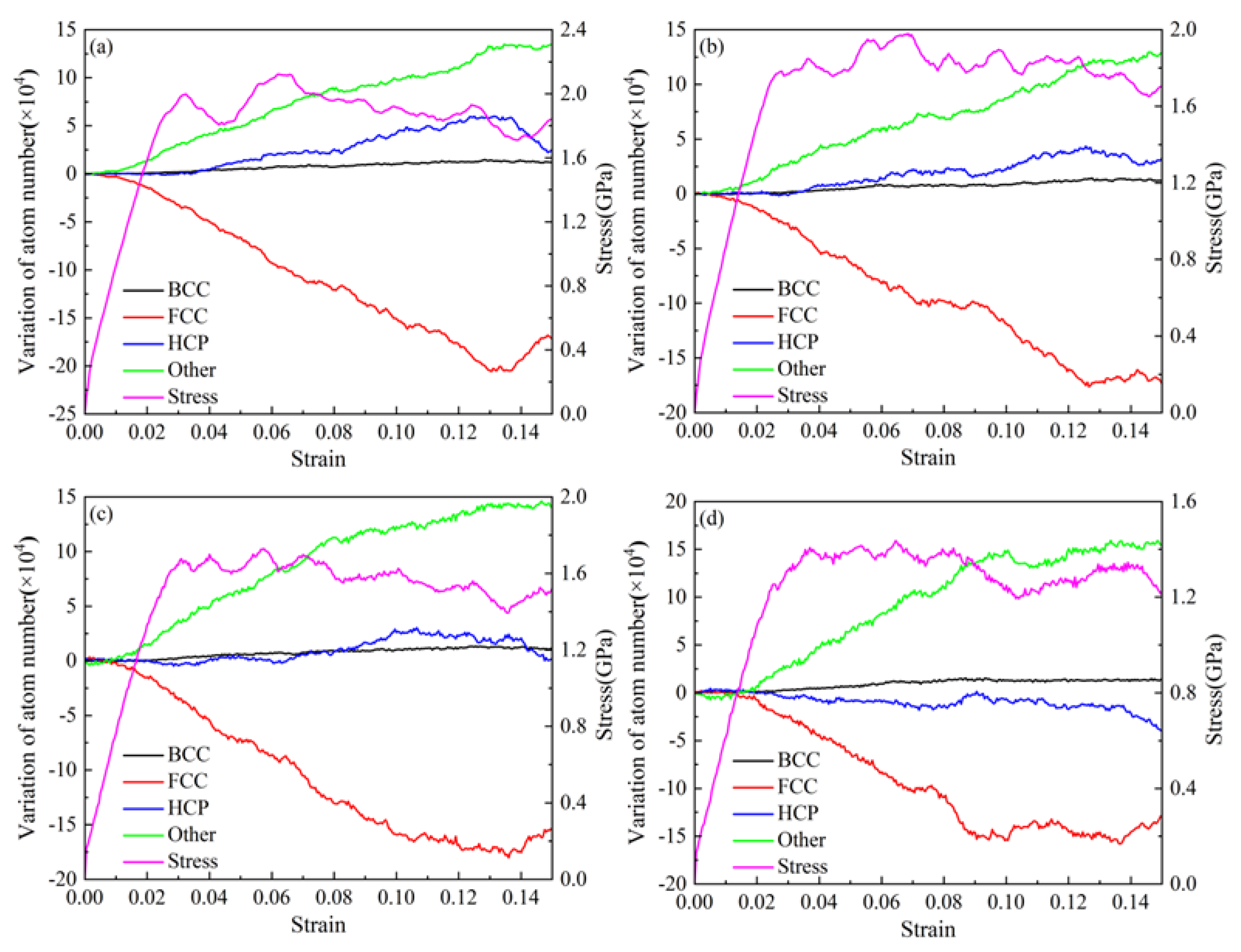

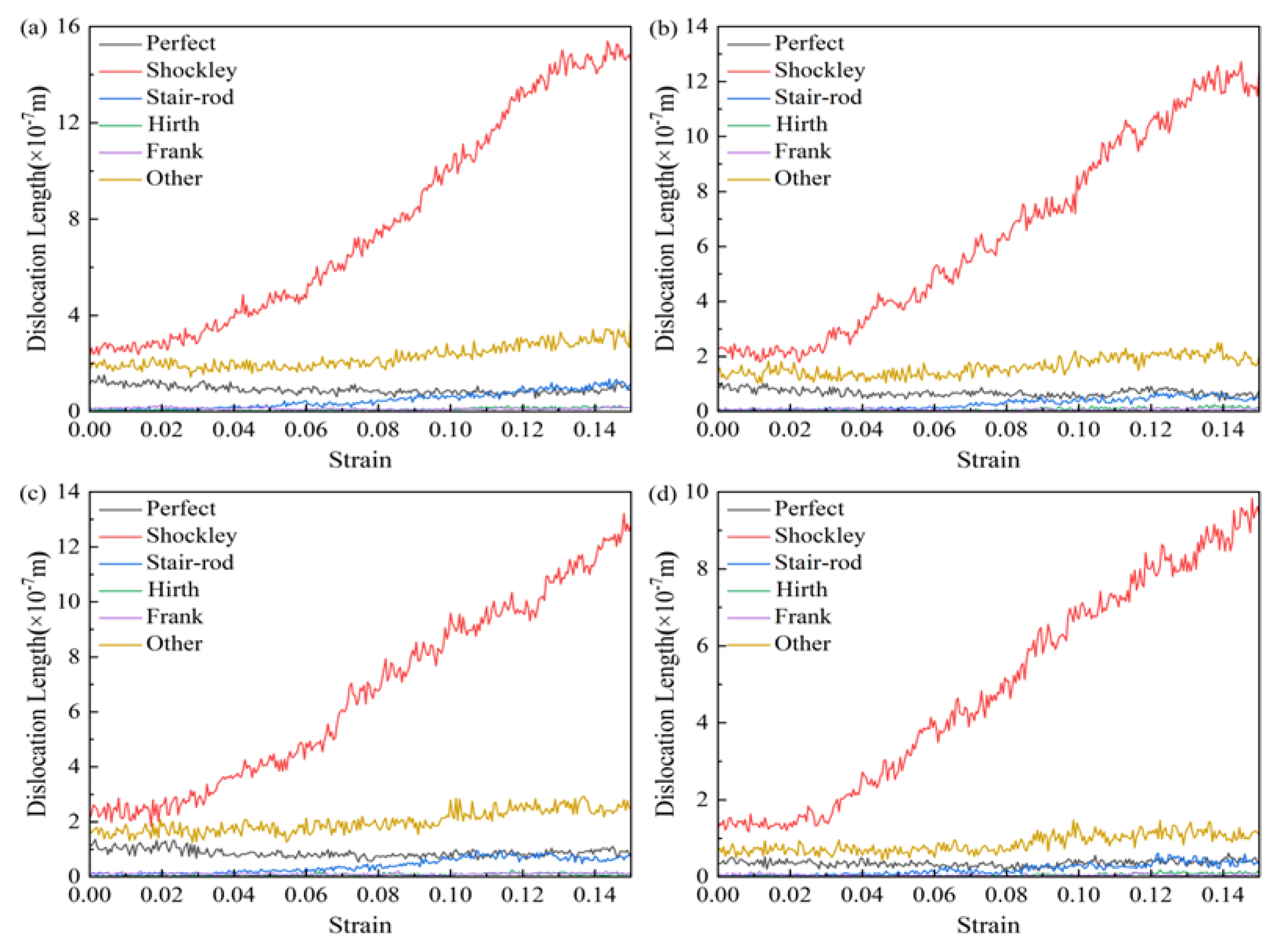

(2) By changing the relaxation temperature and deformation temperature of the nanotwin AgPd alloy with an average grain size of 11.00 nm, it was found that as the temperature increased, the Young's modulus and average flow stress of the nanotwin AgPd alloy gradually decreased; On the microstructure, it was found that the AgPd alloy with a twin spacing of 1.35 nm transformed from HCP and FCC structural atoms to Other structural atoms at higher temperatures (500 K), and from FCC structural atoms to HCP and Other structural atoms at lower temperatures (10K and 100K). The length and total dislocation density of the Shockley dislocation lines, which occupy the main position in the dislocation lines, increased with decreasing temperature. Lower temperatures will increase the stability of preset twins and the generation of new twins, while higher temperatures will promote the movement of atoms and the migration of grain boundaries and twin boundaries, further exacerbating the occurrence of "de twinning".

Figure 2.

The stress-strain curves of nanotwin AgPd alloy with different twin spacing under compression. (a) d=5.50 nm; (b) d=8.24 nm;(c) d=11.00 nm;(d) d=13.76 nm.

Figure 2.

The stress-strain curves of nanotwin AgPd alloy with different twin spacing under compression. (a) d=5.50 nm; (b) d=8.24 nm;(c) d=11.00 nm;(d) d=13.76 nm.

Figure 3.

The average flow stress variation curve of nanotwin AgPd alloy with different twin spacing during compression. (a) d=5.50 nm; (b) d=8.24 nm;(c) d=11.00 nm;(d) d=13.76 nm.

Figure 3.

The average flow stress variation curve of nanotwin AgPd alloy with different twin spacing during compression. (a) d=5.50 nm; (b) d=8.24 nm;(c) d=11.00 nm;(d) d=13.76 nm.

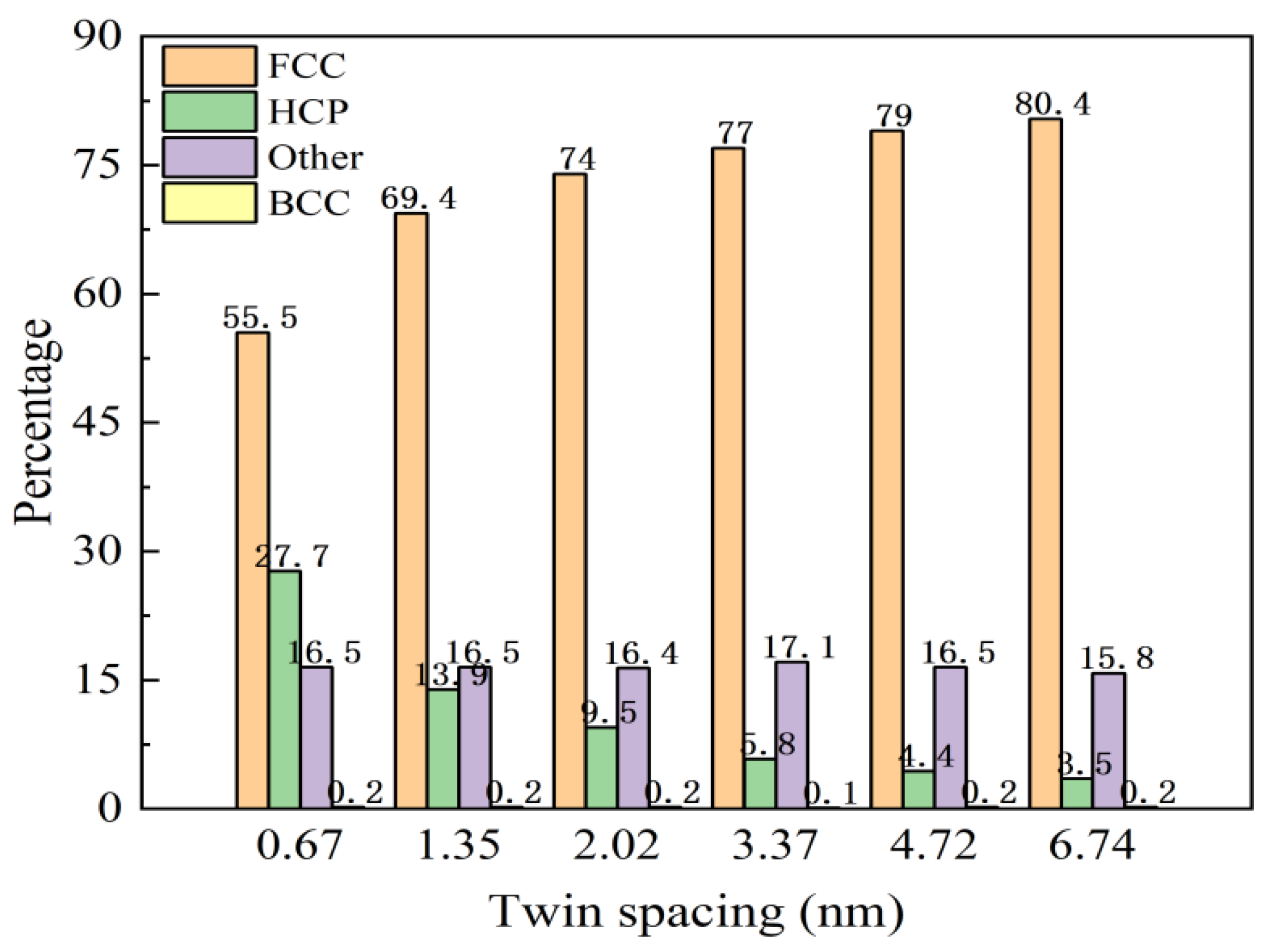

Figure 4.

The statistical chart of atomic proportions in various structures of AgPd alloy with different twin spacing after relaxation.

Figure 4.

The statistical chart of atomic proportions in various structures of AgPd alloy with different twin spacing after relaxation.

Figure 5.

The variation curve of atomic changes and stress with strain in the structure of nanotwin AgPd alloy with different twin spacing. (a) λ=0.67 nm;(b) λ=1.35 nm;(c) λ=2.02 nm;(d) λ=3.37 nm;(e) λ=4.72 nm;(f) λ=6.74 nm.

Figure 5.

The variation curve of atomic changes and stress with strain in the structure of nanotwin AgPd alloy with different twin spacing. (a) λ=0.67 nm;(b) λ=1.35 nm;(c) λ=2.02 nm;(d) λ=3.37 nm;(e) λ=4.72 nm;(f) λ=6.74 nm.

Figure 6.

The variation curve of the length of various types of dislocation lines with strain in nanotwin AgPd alloy. (a) λ=0.67 nm;(b) λ=1.35 nm;(c) λ=2.02 nm;(d) λ=3.37 nm;(e) λ=4.72 nm;(f) λ=6.74 nm.

Figure 6.

The variation curve of the length of various types of dislocation lines with strain in nanotwin AgPd alloy. (a) λ=0.67 nm;(b) λ=1.35 nm;(c) λ=2.02 nm;(d) λ=3.37 nm;(e) λ=4.72 nm;(f) λ=6.74 nm.

Figure 7.

The variation curve of dislocation density with strain in nanotwin AgPd alloys with different twin spacing.

Figure 7.

The variation curve of dislocation density with strain in nanotwin AgPd alloys with different twin spacing.

Figure 8.

The nanocrystalline polycrystalline AgPd alloy with average grain size of 11.00 nm exhibits compressed atomic diagrams at 0% (a), 3.00% (b), 12.00% (c), and 15.00% (d), respectively. a1-d1 and a2-d2 are corresponding shear strain and displacement vector diagrams, respectively.

Figure 8.

The nanocrystalline polycrystalline AgPd alloy with average grain size of 11.00 nm exhibits compressed atomic diagrams at 0% (a), 3.00% (b), 12.00% (c), and 15.00% (d), respectively. a1-d1 and a2-d2 are corresponding shear strain and displacement vector diagrams, respectively.

Figure 9.

The nanocrystalline polycrystalline AgPd alloy with a twin spacing of 0.67 nm and an average grain size of 11.00 nm exhibits compressed atomic diagrams at 0% (a), 3.00% (b), 12.00% (c), and 15.00% (d), respectively. a1-d1 and a2-d2 are corresponding shear strain and displacement vector diagrams, respectively.

Figure 9.

The nanocrystalline polycrystalline AgPd alloy with a twin spacing of 0.67 nm and an average grain size of 11.00 nm exhibits compressed atomic diagrams at 0% (a), 3.00% (b), 12.00% (c), and 15.00% (d), respectively. a1-d1 and a2-d2 are corresponding shear strain and displacement vector diagrams, respectively.

Figure 10.

The nanocrystalline polycrystalline AgPd alloy with a twin spacing of 1.34 nm and an average grain size of 11.00 nm exhibits compressed atomic diagrams at 0% (a), 2.85% (b), 8.30% (c), and 15.00% (d), respectively. a1-d1 and a2-d2 are corresponding shear strain and displacement vector diagrams, respectively.

Figure 10.

The nanocrystalline polycrystalline AgPd alloy with a twin spacing of 1.34 nm and an average grain size of 11.00 nm exhibits compressed atomic diagrams at 0% (a), 2.85% (b), 8.30% (c), and 15.00% (d), respectively. a1-d1 and a2-d2 are corresponding shear strain and displacement vector diagrams, respectively.

Figure 11.

The nanocrystalline polycrystalline AgPd alloy with a twin spacing of 6.74 nm and an average grain size of 11.00 nm exhibits compressed atomic diagrams at 0% (a), 2.45% (b), 8.55% (c), and 15.00% (d), respectively. a1-d1 and a2-d2 are corresponding shear strain and displacement vector diagrams, respectively.

Figure 11.

The nanocrystalline polycrystalline AgPd alloy with a twin spacing of 6.74 nm and an average grain size of 11.00 nm exhibits compressed atomic diagrams at 0% (a), 2.45% (b), 8.55% (c), and 15.00% (d), respectively. a1-d1 and a2-d2 are corresponding shear strain and displacement vector diagrams, respectively.

Figure 12.

The stress-strain curves of nanotwin AgPd alloy under compression at different temperatures, (a)10 K;(b)100 K;(c)300 K;(d)500 K.

Figure 12.

The stress-strain curves of nanotwin AgPd alloy under compression at different temperatures, (a)10 K;(b)100 K;(c)300 K;(d)500 K.

Figure 13.

The curve of the change in Young's modulus (a) and average flow stress (b) of nanotwin AgPd alloy at different temperatures with the variation of nanotwin spacing.

Figure 13.

The curve of the change in Young's modulus (a) and average flow stress (b) of nanotwin AgPd alloy at different temperatures with the variation of nanotwin spacing.

Figure 14.

Statistical charts of the atomic proportions of each structure in nanotwin AgPd alloy after relaxation at different temperatures.

Figure 14.

Statistical charts of the atomic proportions of each structure in nanotwin AgPd alloy after relaxation at different temperatures.

Figure 15.

The variation curves of atomic changes and stress with strain in the structure of nanotwin AgPd alloy at different temperatures. (a)10 K;(b)100 K;(c)300 K;(d)500 K.

Figure 15.

The variation curves of atomic changes and stress with strain in the structure of nanotwin AgPd alloy at different temperatures. (a)10 K;(b)100 K;(c)300 K;(d)500 K.

Figure 16.

The variation curve of the length of various types of dislocation lines with strain in nanotwin AgPd alloy at different temperatures. (a)10 K;(b)100 K;(c)300 K;(d)500 K.

Figure 16.

The variation curve of the length of various types of dislocation lines with strain in nanotwin AgPd alloy at different temperatures. (a)10 K;(b)100 K;(c)300 K;(d)500 K.

Figure 17.

The variation curve of dislocation density with strain in nanotwin AgPd alloy at different temperatures.

Figure 17.

The variation curve of dislocation density with strain in nanotwin AgPd alloy at different temperatures.

Figure 18.

The compressed atomic diagrams of nanotwin AgPd alloy at different temperatures at strains of 0% (a, a1, a2), 2.60% (b, b1, b2), 10.00% (c, c1, c2), and 15.00% (d, d1, d2).

Figure 18.

The compressed atomic diagrams of nanotwin AgPd alloy at different temperatures at strains of 0% (a, a1, a2), 2.60% (b, b1, b2), 10.00% (c, c1, c2), and 15.00% (d, d1, d2).

Figure 19.

The compressed atomic diagrams of a nanocrystalline polycrystalline AgPd alloy with a twin spacing of 0.67 nm and an average grain size of 11.00 nm at 0% (a), 3.15% (b), 13.05% (c), and 15.00% (d) strain are presented. a1-d1 and a2-d2 are the corresponding shear strain diagrams and displacement vector diagrams, respectively.

Figure 19.

The compressed atomic diagrams of a nanocrystalline polycrystalline AgPd alloy with a twin spacing of 0.67 nm and an average grain size of 11.00 nm at 0% (a), 3.15% (b), 13.05% (c), and 15.00% (d) strain are presented. a1-d1 and a2-d2 are the corresponding shear strain diagrams and displacement vector diagrams, respectively.

Figure 20.

The compressed atomic diagrams of a nanocrystalline polycrystalline AgPd alloy with a twin spacing of 0.67 nm and an average grain size of 11.00 nm at 0% (a), 3.15% (b), 13.05% (c), and 15.00% (d) strain are presented. a1-d1 and a2-d2 are the corresponding shear strain diagrams and displacement vector diagrams, respectively.

Figure 20.

The compressed atomic diagrams of a nanocrystalline polycrystalline AgPd alloy with a twin spacing of 0.67 nm and an average grain size of 11.00 nm at 0% (a), 3.15% (b), 13.05% (c), and 15.00% (d) strain are presented. a1-d1 and a2-d2 are the corresponding shear strain diagrams and displacement vector diagrams, respectively.

Table 1.

Initial configuration related parameters of nanotwin AgPd alloy.

Table 1.

Initial configuration related parameters of nanotwin AgPd alloy.

| Alloy |

Average grain size (d/nm) |

Number of atoms |

Twin spacing (λ/nm) |

| AgPd |

5.00 |

67900 |

0.67 |

1.35 |

2.02 |

2.70 |

3.37 |

4.04 |

| 8.24 |

228500 |

0.67 |

1.35 |

2.02 |

3.37 |

4.72 |

6.74 |

| 11.00 |

542500 |

0.67 |

1.35 |

2.02 |

3.37 |

4.72 |

6.74 |

| 13.76 |

1061000 |

0.67 |

1.35 |

2.02 |

3.37 |

4.72 |

6.74 |