Submitted:

24 December 2024

Posted:

24 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

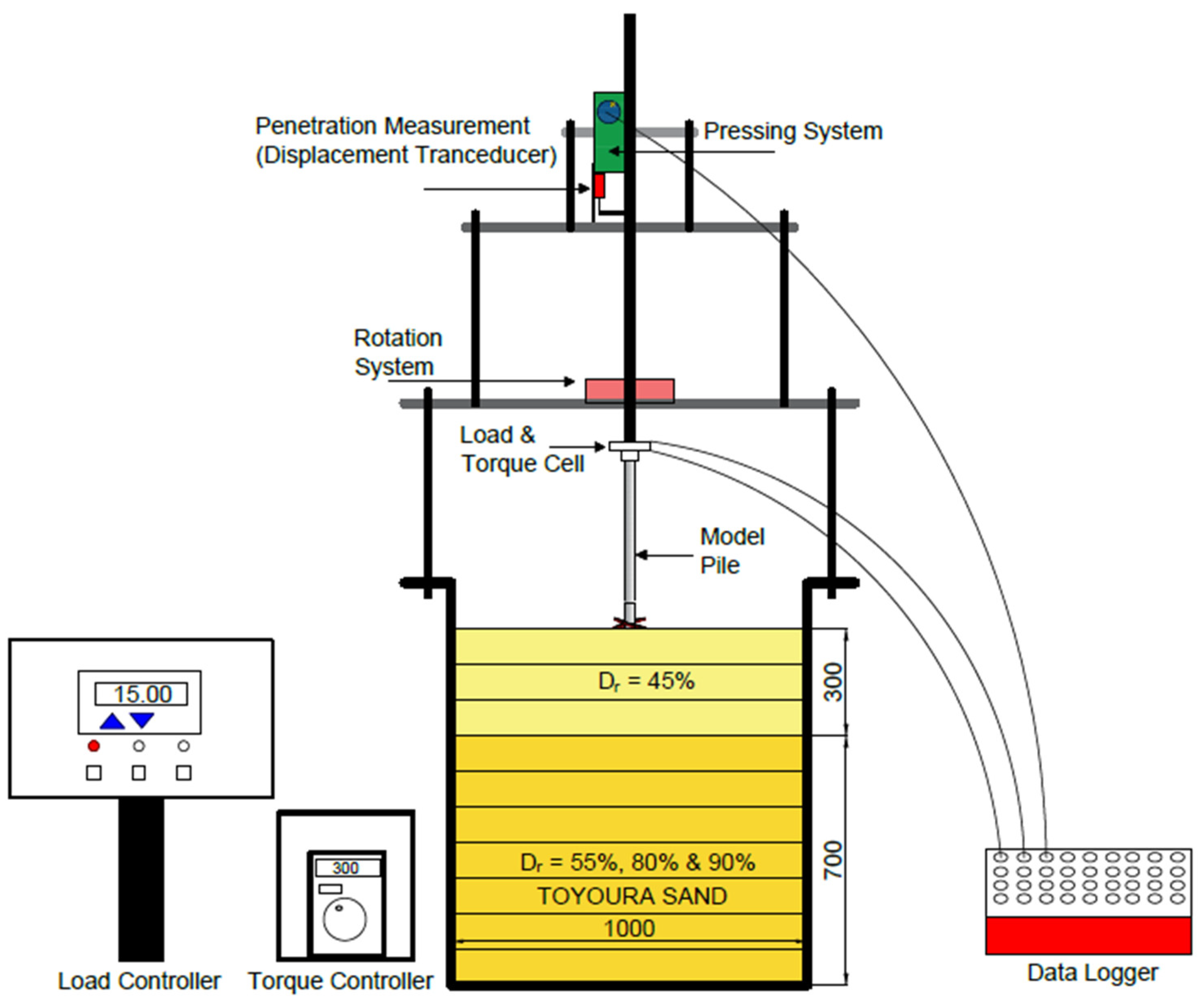

2.1. Testing Procedure

| Test Materials | Specific Gravity | D50 | Emax | Emin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dry Toyoura Sand | 2.645 | 0.19 | 0.973 | 0.609 |

2.2. Model Container

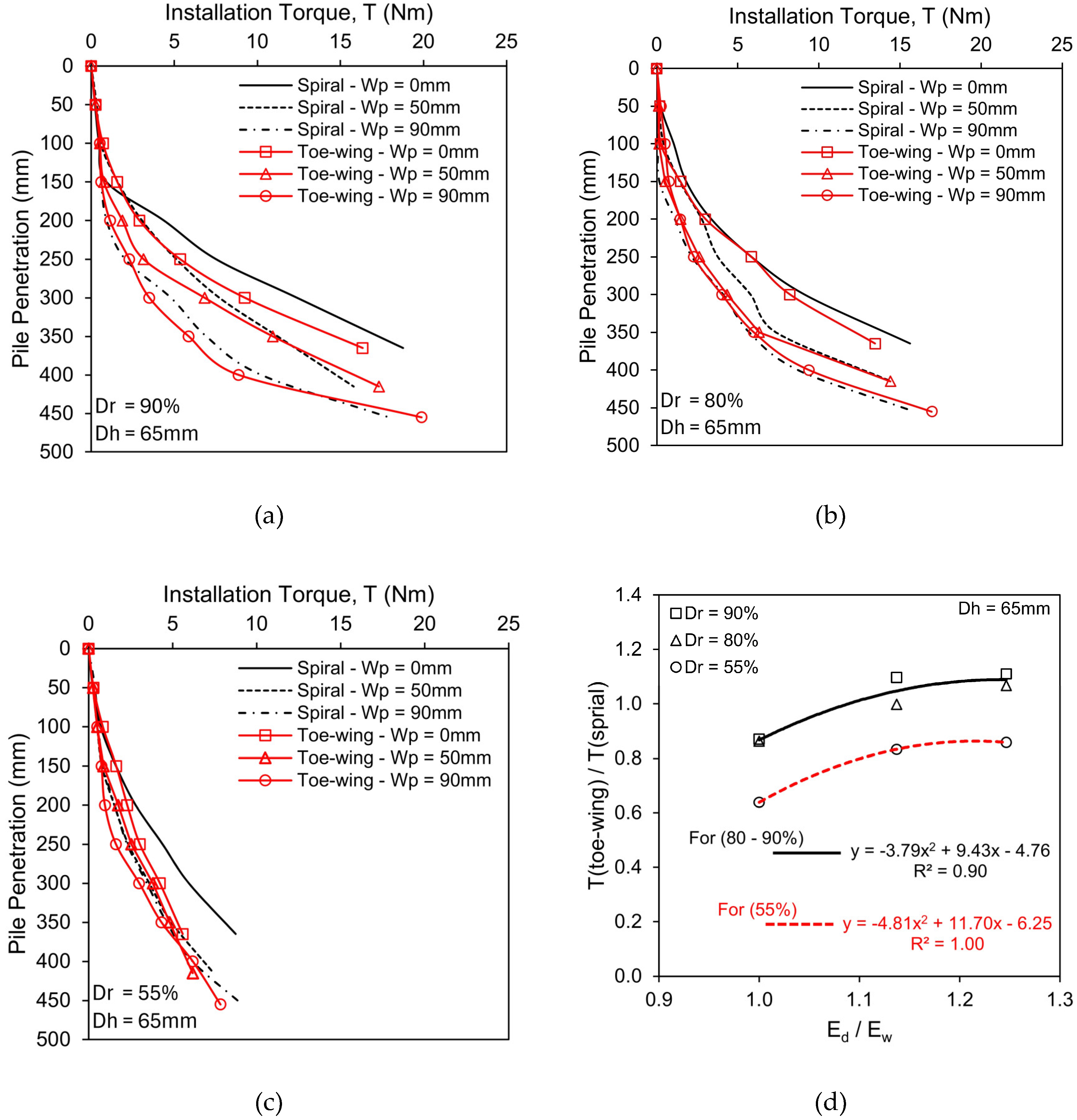

2.3. Model Screw Piles with Toe-Wing (Tsubasa Pile) & Spiral Screw Piles

3. Results And Discussions

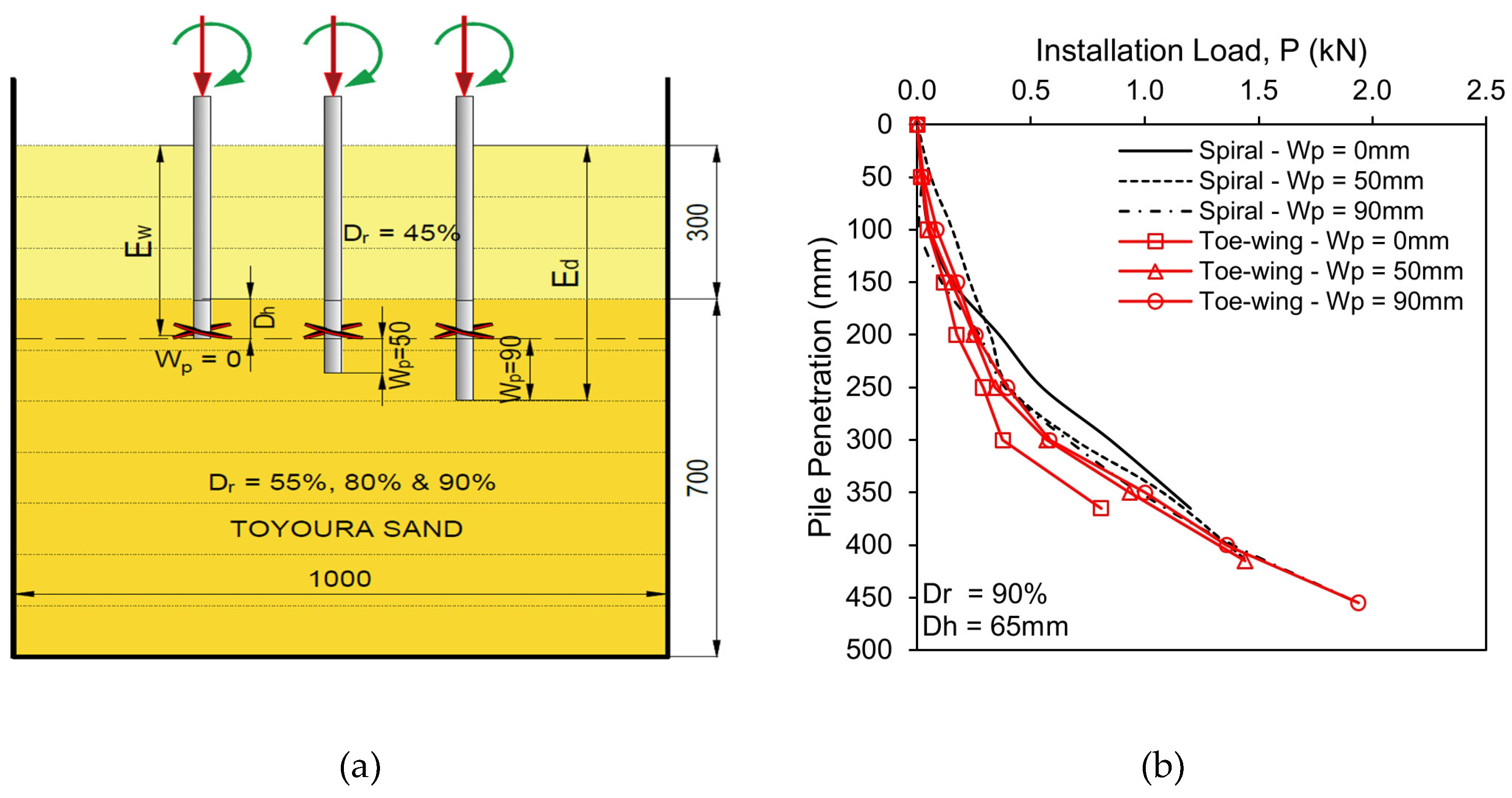

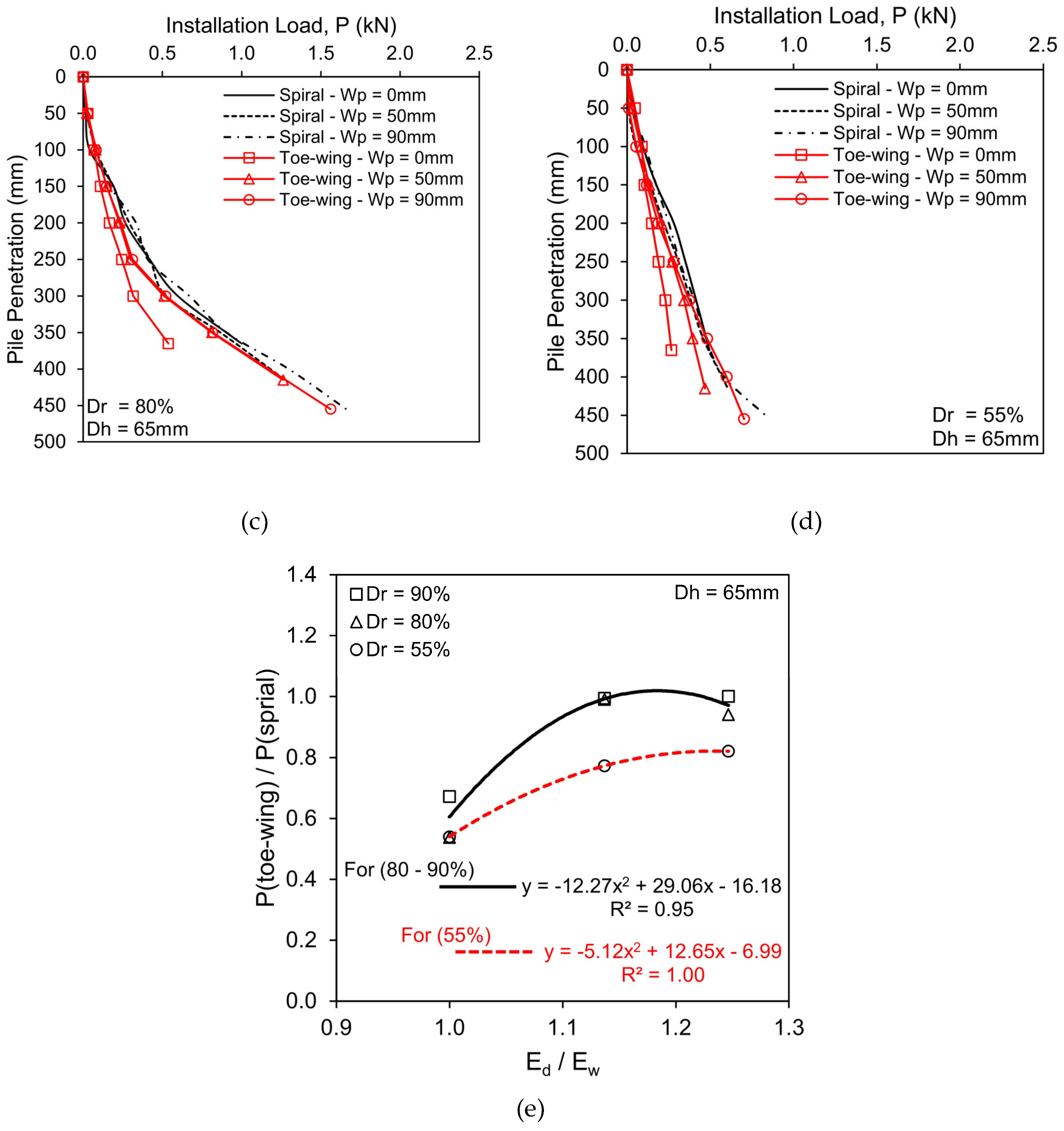

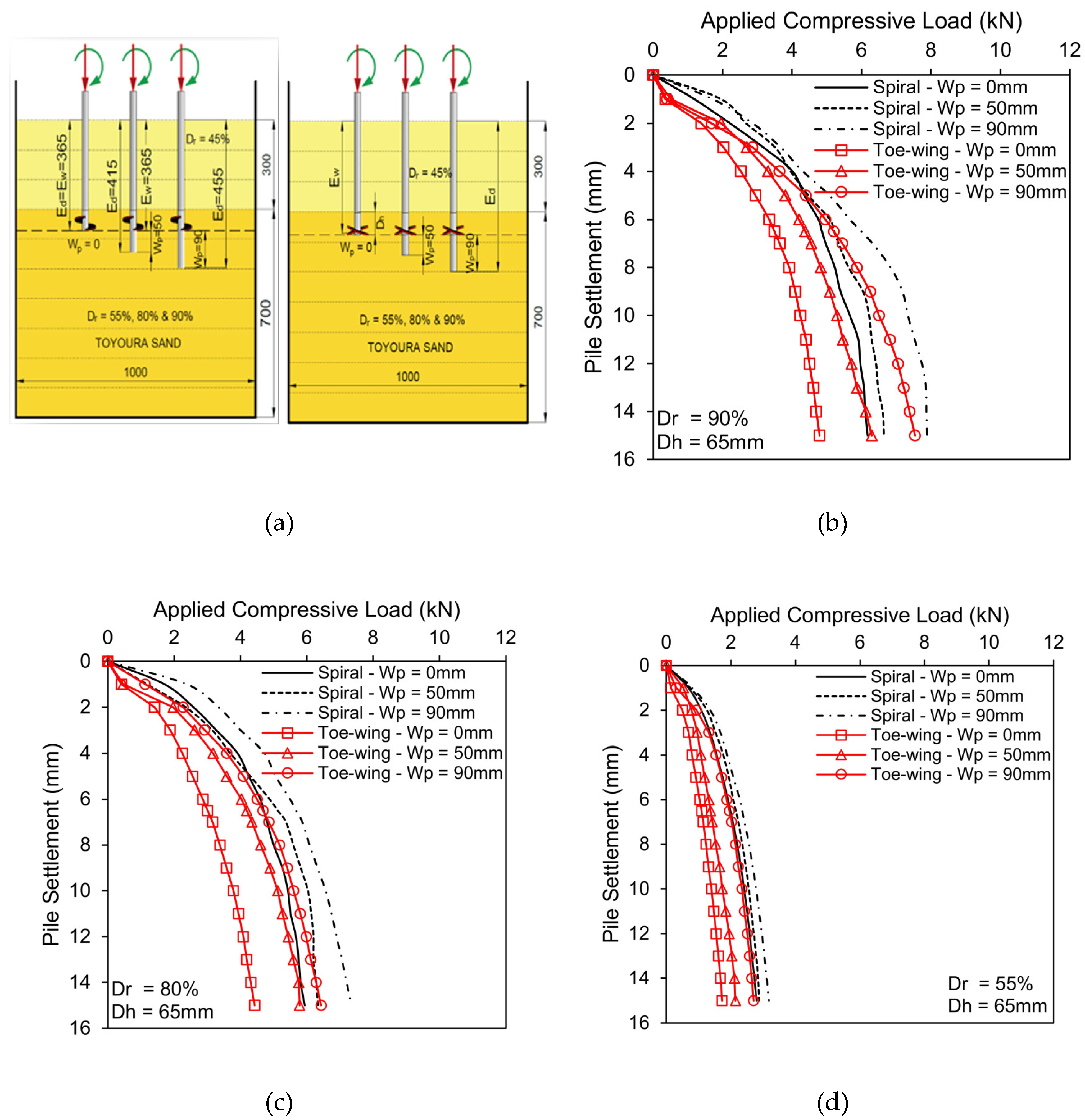

3.1. Scenario 1 - Fixed Helix/Toe-Wing Position with Increasing Pile Tip Depth From 0 to 90 mm

3.2. Scenario 2 - Varying Helix/Toe-Wing Position with Constant Pile Tip Depth

4. Conclusions

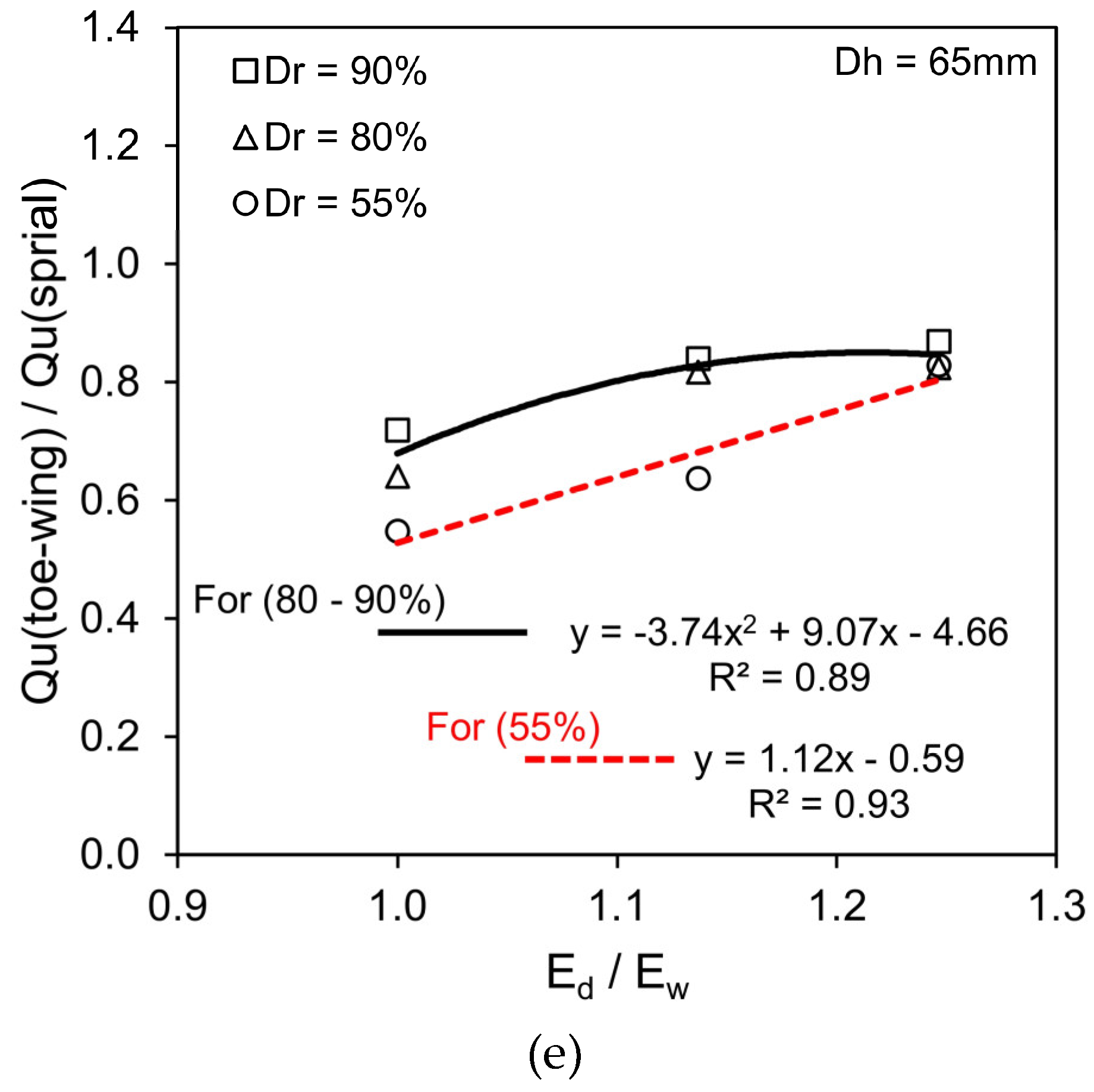

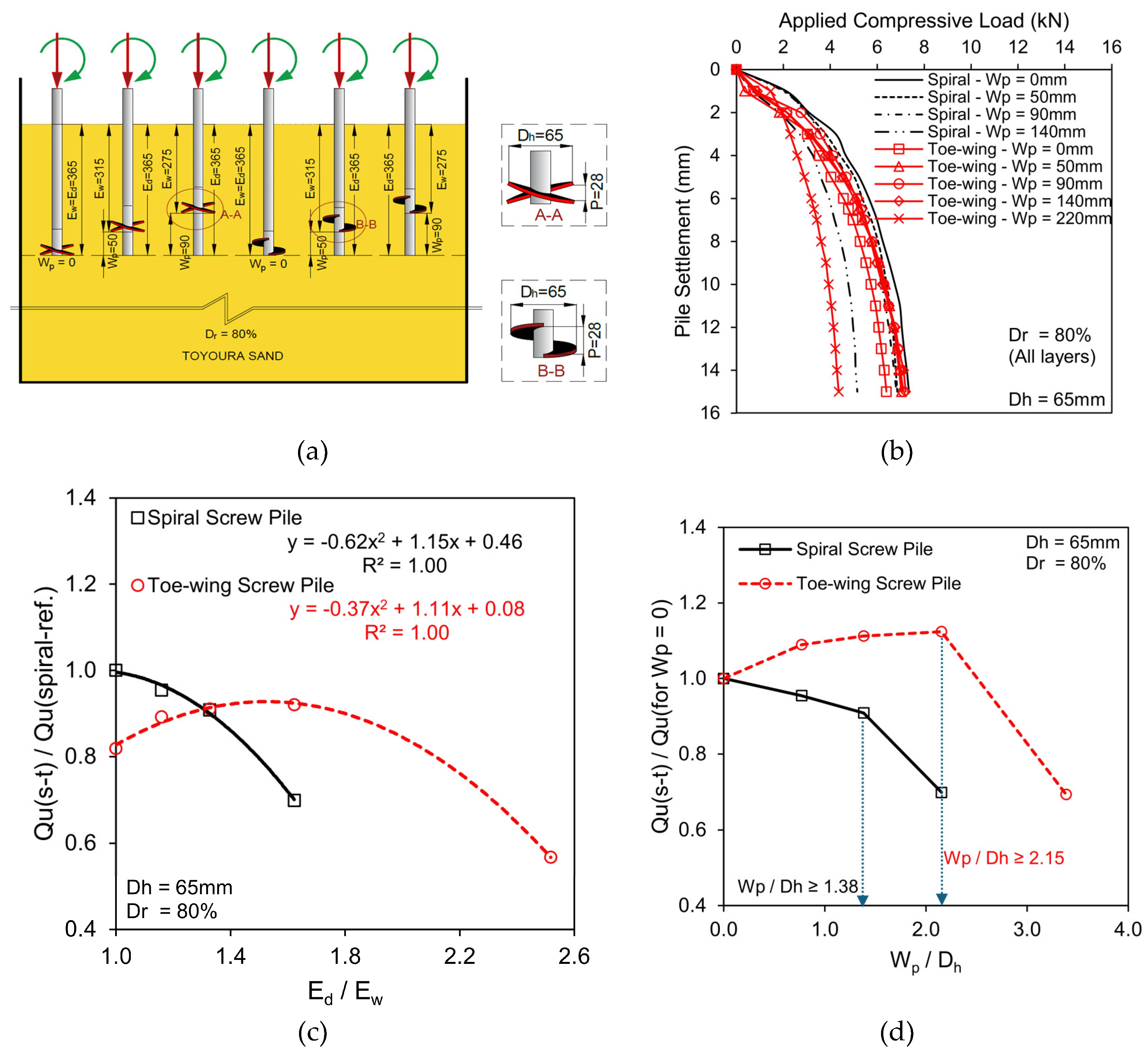

- In the case of fixed helix/toe-wing position with increasing pile tip embedment (Scenario 1), the toe-wing screw pile showed lesser installation load requirements than the spiral screw pile. As the helix distance from the pile tip increased (Wp, 0 to 90mm), the spiral screw pile installation requirements decreased, whereas, for the toe-wing screw pile, the behavior was reversed, i.e., increased. The installation torque decreased as the helix/toe-wing moved away from the pile tip (Wp > 0) for both types of piles. However, at Wp = 0 (helix/toe-wing at pile tip), less installation torque is needed for the toe-wing screw pile than for the spiral screw pile. Moreover, when the helix/toe-wing position is greater than zero (Wp > 0), the installation torque requirement for the toe-wing screw pile in dense to very dense sand (Dr = 80-90%) is higher than the spiral screw pile. Whereas in loose sand conditions (Dr =55%), the toe-wing screw pile shows lesser torque requirements. Empirical equations presented in Figure 3(e) for installation load requirements and Figure 4(d) for installation torque requirements can be used to convert the installation load and torque from one type of pile to another within the considered range of the Ed/Ew ratio (1.0 to 1.25).

- In Scenario 1, the spiral screw piles showed higher load-carrying resistance than the toe-wing screw piles at relative densities of 55%, 80%, and 90%. Moreover, load-carrying resistance increased as the position of the helix/toe-wing increased (Wp > 0), which is due to the increase in pile tip embedment depth (Ed). At the initial stage of the load-settlement curve, the spiral screw pile showed a stiffer response than the toe-wing screw pile, and this indicates that the soil-helix contact is better than the soil-toe-wing contact at all considered bearing layer relative densities (Dr). Empirical equations shown in Figure 5(e) can convert the ultimate pile capacity of one type of pile to another within the provided range of Ed/Ew, i.e., 1.0 to 1.25.

- In the case of fixed pile tip depth (Ed) with varying helix/toe-wing position (Scenario 2), spiral screw piles have higher load-carrying resistance than toe-wing screw piles when the helix/toe-wing position is less than 90mm (Wp < 90mm). Both piles showed a similar ultimate pile capacity at Ed/Ew = 1.33. Moreover, the ultimate pile capacity of the spiral screw pile decreased as the helix moved away from the pile tip due to the decrease in helix contribution towards bearing response. This contribution drastically reduced when the Wp/Dh ratio was greater than 1.38, indicating that the helix and central shaft pile tip act independently. Whereas, for the toe-wing screw pile, the ultimate pile capacity increased when the toe-wing moved away from the pile tip up to Wp/Dh = 2.15. This increase is due to less contribution of the toe-wing as it moves away from the pile tip towards the bearing response, which is because the toe-wing loosens the ground more when it is close to the tip. As it moves away, it causes less ground loosening, increasing pile capacity. However, when Wp/Dh > 2.15, the pile capacity drastically decreased because the toe-wing and pile tip act independently rather than as a group. Empirical equations presented in Figure 6(c) can convert ultimate pile capacity from one pile type to another with varying Ed/Ew ratio (considered in this study) at a relative density of 80%.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saleem, M.A.; Malik, A.A.; Kuwano, J. End Shape and Rotation Effect on Steel Pipe Pile Installation effort and Bearing Resistance. Geomechanics and Engineering, 2020, 23(6), 523-533. [CrossRef]

- Wada, M.; K, Tokimatsu.; S, Maruyama.; and M, Sawaishi. Effects of cyclic vertical loading on bearing and pullout capacities of piles with continuous helix wings. Soils Found, 2017, 57 (1), 141–153. [CrossRef]

- Nagata, M.; and H. Hirata. Study on the uplift resistance of screwed steel pile. Nippon Steel Technical Rep. No. 92, Tokyo, Nippon Steel and Sumimoto Metal, 2005, 73–78.

- Tsuchiya, T.; Kohsaka, M. Statistical study on the vertical bearing capacity of screw piles. AIJ J. Technol. Design 21 (49), 2015,991–994 (in Japanese). [CrossRef]

- Tsuchiya, T.; Nagai, H.; Shimo, N. Statistical study on settlement characteristics at the toe of screw piles. AIJ J. Technol. Design 22 (52), 2016, 915–918 (in Japanese). [CrossRef]

- Ho, H.M.; Malik, A.A.; Kuwano, J.; Brasile, S.; Tran, T.V.; Mazhar, M.A. Experimental and Numerical Study on Pressure Distribution under Screw and Strainght Pile in Dense Sand. International Journal of Geomechanics, 2022, 22(9), 04022139. [CrossRef]

- Zuo, H.; Jin, N.; Xu CY. Experiment on the vertical bearing capacity of screw grout pile in a cohesive area. J Shenyang Jianzhu Uni (Nat Sci),32(2):2016, 225–31.

- Peng, Ding.; Yang,Liu.; Cheng,Shi.; Fanguang,Meng.; Wei, Li.; Zhiyun, Deng.; and Xu, Chang.Study on Bearing Mecha-nism of Steel Screw Pile. Buildings 2024, 14, 3376. [CrossRef]

- Yifeng, Lin.; Jiandong, Xiao.; Conghuan, Le.; Puyang, Zhang.; Qingshan, Chen.; and Hongyan, Ding. Bearing Characteristics of Helical Pile Foundations for Offshore Wind Turbines in Sandy Soil. J. Mar. Sci. Eng.mdpi. 2022, 10, 889. [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.A.; Jiro, Kuwano. Single Helix Screw Pile Behavior Under Compressive Loading/Unloading Cycles in Dense Sand. Geotech Geol Eng, (2020), 38:5565–5575. Volume 38, pages 5565-5575. [CrossRef]

- Yang,Z.X.; Jardine,R.J,.; B,T, Zhu.; and S, Rimoy. Stresses Developed around Displacement Piles Penetration in Sand, Journal of Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering, 2014, no. 3, art, 140.

- Ghaly, A.; and A, Hanna. Experimental and Theoretical Studies on Installation Torque of Screw Anchors. Canadian Geotechnical Journal, 1991, Vol. 28, Issue 3, 353–364. [CrossRef]

- Spagnoli, G.; C M, Mendez Solarte.; Cde, Hollanda Cavalcanti Tsuha.; and P, Oreste. Parametric Analysis for the Estimation of the Installation Power for Large Helical Piles in Dry Cohesionless Soils. International Journal of Geotechnical Engineering, 2018, Vol.144, Issue 6, 1–11. (in press).

- R,J, Jardine.; B,T, Zhu.; P, Foray, Z,X, Yang.Measurement of stresses around closed-ended displacement piles in sand, Géotechnique, 2013, vol. 63, Issue 1, 1–17.

- J, Dijkstra.; W, Broere.; O, M, Heeres. Numerical simulation of pile installation, Computers and Geotechnics, 2011, vol. 38, Issue 5, 612–622. [CrossRef]

- T,C, Siegel.; W,M, NeSmith.; W,M, NeSmith.; P,E, Cargill.Ground improvement resulting from the installation of drilled displacement piles, in Proceedings of the DFI’s 32nd Annual Conference Deep Foundations. Colorado Springs, USA, 2007, 129–138.

- Malik, A.A.; Ahmed, S.I.; Ali, U.; Shah, S.K.H.; Kuwano, J. Advancement Ratio Effect on Screw Pile Performance in the Bearing Layer. Soil and Foundations, 2024, 64(6), 101537. [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.A.; Ahmed, S.I.; Kuwano, J.; Maejima, T. Effect of Change in Penetration to Rotation Rate on Screw Pile Performance in Loose Sand. In: Hazarika, H., Haigh, S.K., Chaudhary, B., Murai, M., Manandhar, S. (eds) Climate Change Adaptation from Geotechnical Perspectives. CREST 2023, 2023. Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering, 447, Springer, Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Qingxu,Zhao.; Yuxing,Wang.; Yanqin, Tang.; Guofeng, Ren.; Zhiguo, Qiu.; Wenhui,Luo.; and Zilong, Y. Numerical Analysis of the Installation Process of Screw Piles Based on the FEM-SPH Coupling Method.College of Engineering, South China Agricultural University, Guangzhou 510642, China. Applied Sciences MDPI, Volume 12, Issue 17, Appl. Sci. 2022, 12(17), 8508. [CrossRef]

- E.I. Robinsky.; C.F. Morrison. Sand Displacement and Compaction around Model Friction Piles, Canadian Geotechnical Journal, vol. 1, Issue 2, 1964, 81–93. [CrossRef]

- G.G. Meyerhof. Compaction of Sands and Bearing Capacity of Piles, Journal of the Soil Mechanics and Foundations Division, 1959, vol. 85, Issue 6, 29-9.

- C. Szechy. The Effects of Vibration and Driving Upon the Voids in Granular Soil Surrounding a Pile, in Soil Mechanics and Foundation Engineering, vol. 2. 1961, 61–164.

- Tsutomu, TSUCHIYA.; Mai, KOHSAKA. Statistical Study on Vertical Bearing Capacity of Screw Piles. AIJ J. Technol. Des., Vol. 21, Issue 49, Oct, 2015, 991-994.

- Kawai, M.; Ichikawa, K..; and Kono, K. Development of New Type of Screwed Pile with Large Bearing Capacity and Ecological Driving Method Tusbas PileTM, In: Tran-Nguyen H.H., Wong H, Ragueneau F., Ha-Minh C. (eds), Proceedings of the 4th Congres International de Geotechnique – Ouvrages – Structures, CIGOS217, Lecture Notes in Civil Engineering, Vol. 8, Springer, 2018,411-425.

- Garnier, J.; Gaudin, C.; Springman, S, Cullingan,; SM., Goodings, D..; Konig, D.; Kutter, B.; Phillips, R.; Randolph, MF.; and Thorel,L. Catalogue scaling laws and similitude questions in geotechnical centrifuge modeling, Int J Phys Model Geotech, Vol. 3,2007, 1–24.

- Rakotonindriana, MHJ.; Kouby, AL.; Buttigieg, S.; Derkx, F.; Thorel, L.; and Garnier, J. Design of an instrumented model pile for axial cyclic loading. In: Laue J, Seward L (eds) Physical modeling in Geotechnics Springman. Taylor & Francis Group, London, 2010, 991–996.

- Kishida, H. Stress Distribution of Model Piles in Sand. Soils and Foundations, Vol. 4, Issue 1, 1963, 1-23. [CrossRef]

- Robinsky, EI.; Morrison, CF. Sand displacement and compaction around model friction piles. Can Geotech J, (1964),1(2):81–93. [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Yang, J. Bearing capacity of open-ended steel pipe piles in sand. J Geotech Geoenviron Eng, (2012), 138(9):1116–1128.

- Randloph, MF.; Worth. CF Analysis of deformation of vertically loaded piles. J Geotech Eng Div,(1978), 104(12):1465–1488.

- Zhang, D.J.Y.; Chalaturnyk, R.; Robertson, P.K.; Sego, D.C.; Cyre, G. Screw anchor test program (Part I & II): instrumentation, site characterization and installation. In: 1998, Proceedings of the 51st Canadian Geotechnical Conference. Edmonton.

- Nasr, M.H. Performance-based design for helical piles. In: Contemporary Topics in Deep Foundations. American Society of Civil Engineers,2009, USA, 496–503.

- Qingxu, Zhao.; Kun, Hu.; Yuxing, Wang.; Yanqin, Tang.; Guofeng, Ren.Analysis on torque and pile--soil interaction of anti--flood screw pile during the installation process.Arabian Journal of Geosciences, Springer,2022, Volume 15, article number 1018.

- Venkatesan, Vignesh.; and Muthukumar, Mayakrishnan.Design parameters and behavior of helical piles in cohesive soils—A review,Arabian Journal of Geosciences,Springer, 2020,Volume 13, article number 1194.

|

[mm] |

[mm] |

[mm] |

[mm] |

[degree] |

[mm] |

[mm] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 500 (Toe-wing) | 21.7 | 65 | 3.6 | 25 | 0, 50, 90 | 365, 415, 455 |

| 500 (Spiral) | 21.7 | 65 | 3.6 | 0, 50, 90 | 365, 415, 455 |

| Screw Pile Type | Dh (mm) | Wp (mm) | Pitch (mm) | Ew (mm) | Wp/Dh |

| Toe-wing Screw Pile | 65 | 0, 50, 90, 140, 220 | 28 | 365 | 0, 0.77, 1.38, 2.15, 3.38 |

| Spiral Screw Pile | 65 | 0, 50, 90, 140 | 28 | 365 | 0, 0.77, 1.38, 2.15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).