1. Introduction

1.1. Characteristics of the Building and Planned Energy Modernization

The Faculty of Building Services Hydro and Environmental Engineering Warsaw University of Technology building (Faculty Building) was erected in the 1970s. It consists of two wings arranged in the shape of the letter L. The more extended wing has 8 above-ground floors. The facades of this part of the Faculty Building are oriented in the northern and southern directions. The shorter wing with Eastern and Western-directed facades has 11 above-ground floors. In both cases, the highest floor serves technical functions. The total area of the building is 19217 m

2. The height of the story in the clear is 3.4 m. The number of users is estimated at over 2,000 people per day. The building has approximately 335 rooms, of which over 160 are used in the teaching process. Only a few renovations were performed during its 45-year existence. The most important include replacing old wooden windows, installing photovoltaic panels (approx. 100 kWp at roof and façade), and thermally insulating only the southern façade with PV panels [

1].

Building users (employees and students) often complain about the quality of the indoor environment. The fundamental problem is related to an ineffective natural ventilation system. Outdoor air enters the rooms through air leakages in the windows and via reverse draft in the gravity ventilation ducts of some rooms in the lower wing of the building. Double walls that divide corridors and rooms form air gaps that serve as collective ventilation ducts. Initially, mechanical supply and exhaust ventilation systems were planned for auditoriums designed for more than 50 students. Most of these systems are no longer used. Laboratory rooms are equipped with various exhaust ventilation systems (fume hoods, hoods, etc.). These installations, although technologically outdated, are efficient. No air vents were installed in the window frames or the walls during the windows‘ replacement. To identify the environmental problems in the building, the measurements were carried out in 32 rooms for various purposes (approx. 20% of the 163 rooms in which the teaching process is carried out) [

2,

3]. The rooms subject to analysis were located on all floors and all facades of the building. The windows (despite the lack of air vents) mostly remained closed throughout the measurements. The study was conducted during the spring semester, with variable weather conditions. The outside air temperature varied between 6.6 and 18.7°C. During the measurement cycle, there were both cloudy days with rain and sunny days. The air temperature in the analyzed rooms varied from 19.5 to 26.1 ° C, while relative humidity ranged from 24.6 to 45.1%. The average air temperature in the rooms facing south and west was statistically higher than those facing north and east. Carbon dioxide concentrations reached 2500 ppm in some rooms (although rooms were occupied only partially). Particle concentration measurements have shown substantial differences between rooms. Generally elevated PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations were observed in rooms with carpet floors and auditoriums where blackboards and chalk were intensively used. Moreover, in some labs and library storage rooms, PM 2.5 and PM10 concentrations exceeded 150 μg/m

3.

Figure 1.

The building of the Faculty of Building Services, Hydro, and Environmental Engineering, Warsaw University of Technology, a) in its existing state, and b) visualized as it would be after the planned modernization.

Figure 1.

The building of the Faculty of Building Services, Hydro, and Environmental Engineering, Warsaw University of Technology, a) in its existing state, and b) visualized as it would be after the planned modernization.

In the integrated design process, among many options considered, modernization variants were selected that significantly reduced energy demand and positively impacted the indoor environment’s quality. The final design concept includes the following modernization actions [

4]:

insulation of external walls with 21 cm of mineral wool with a thermal conductivity coefficient of 0.031 W/(m·K),

insulation of the roof with 23 cm of mineral wool with a thermal conductivity coefficient of 0.035 W/(m·K),

installation of double facades on the south and west sides (improving thermal and acoustic properties and also acting as shading elements),

construction of an atrium on the courtyard side,

replacement of windows with those characterized by a heat transfer coefficient of 0.9 W/(m2·K), a radiation transmittance coefficient of 0.21, and a light transmittance coefficient of 0.55,

equipping the building with mechanical ventilation with heat recovery (the assumed temperature efficiency of heat recovery is 85%),

replacement of the lighting system with LEDs,

increasing the use of renewable energy sources (in the adopted modernization variant, the surface area of photovoltaic cells installed on the facade and roof of the building has been increased to approximately 600 m2, and their rated power is 489 kWp; a ground-source heat pump is also planned).

After modernization, the expected energy performance indicator EP would drop from 150 kWh/m2 to 6.2 kWh/m2. When selecting the modernization variants, the faculty staff was assumed to be able to continue its teaching and research activities uninterrupted during the building’s modernization. Construction work was planned to be carried out in stages, with the most burdensome tasks being carried out during the summer (3 months) and winter (2 weeks) breaks. The selected modernization technologies enabled most of the assembly work to be carried out from outside the building.

Initially, the concept of hybrid work during modernization seemed unrealistic. Some concerns about conducting teaching at a technical university, mainly based on design and laboratory classes, could affect the quality of education. However, national restrictions during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic made it necessary to introduce remote education. The teaching staff was forced to take an interest in new forms of education, conducting most classes from home and, in exceptional cases, from a room at the faculty. Only the lectures that required personal contact with students (e.g., laboratories) were organized later during the summer holidays when restrictions on occupancy density were eased.

After the pandemic, many academics discovered that remote teaching triggered them to revise concepts and the content of lectures. Those who could arrange comfortable places for remote teaching started to stay home for other academic duties requiring high concentration. Interest in hybrid work noticeably increased.

The paper aims to analyze whether introducing hybrid work, with extensive use of WFH, is possible and will not negatively affect productivity, teaching quality, or the understanding and support of employees. In this way, it can help facilitate the energy modernization of the university building without affecting faculty operation. To achieve this, a survey was conducted among the academic staff of one of the departments to evaluate working conditions and subjective productivity assessments. Additionally, microclimate measurements were carried out in the Faculty Building and at a selected home workplace.

1.2. Work from Home at Academic Teaching and Research

The COVID-19 pandemic has drawn global attention to the issue of working from home. However, this type of work, also called teleworking, telecommuting) or remote work has become increasingly popular over the past 20 years. With recent advances in communication technology that enable high-speed data transfer, working away from the office has become attractive to many workers worldwide. Moreover, telecommuting offers work opportunities for those with disabilities and parents of children with special needs [

5]. In 2014, 59% of U.S. employers allowed telecommuting: 54% offered ad hoc telecommuting, 29% part-time, and 20% full-time [

6].

The success of working from home depends on three aspects: personal skills, the character of the job, and the work organization [

5]. Under certain conditions, both an increase and a decrease in productivity can be observed. Jensen [

7] investigated the significance of potential distracters affecting work at home. He concluded that family, domestic responsibilities, audible and visible distractions, and home office size reduce productivity minimally.

It is estimated that in 2019, 5.7% of the US workforce [

8] and 5.4% of the workforce in the European Union were regularly delivered from home [

9]. In those times in the EU, WFH was preferred mainly by high-skilled workers who extensively used computers, had jobs with high degrees of autonomy, and were involved in knowledge-based activities. Teachers preparing for face-to-face classes and coursework were the group with the highest prevalence of WFH (43%) [

9]. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, 14 % of Poles worked from home regularly or at least sometimes. The differences between EU countries were significant, from 4 to 37%, but the mean for EU-27 countries was identical to that of Poland [

9].

The maximal share of WFH in the whole work market can be estimated from the data reported during the height of the pandemic in 2020. At that time, approximately 40% of Americans and members of the European Union were working from home [

9,

10].

However, it should be pointed out that the COVID-19 pandemic changed the character of working from home from volunteer to obligatory. Generally, individuals worldwide had to create improvised work setups in living rooms, kitchens, and bedrooms. Moreover, because of the closure of schools, many working parents attempt productivity while concurrently supervising their children. As a result of these changes, numerous employees have experienced lower work productivity, lessened motivation, increased stress, and poorer mental health [

11]. However, after arranging comfortable workstations at home, many employees have discovered various advantages of working from home and are open to hybrid work.

Working from home is associated with a radical change in the work environment. For years, reports have claimed that thermal comfort and IAQ significantly impact individual productivity [

12,

13]. Therefore, the hypothesis that working from home and in a regular office may result in different productivity levels is justified; however, it needs to be sufficiently investigated [

14].

Most residential houses in Poland use natural ventilation, with little opportunity to regulate indoor air quality and climate. Modern offices often have advanced HVAC systems that maintain desired thermal comfort and provide good indoor air quality. Widespread poor ventilation performance in residential buildings results in generally higher concentrations of dust (PM2.5, PM10), Volatile Organic Compounds, and CO

2 in homes compared to office buildings [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19].

However, the situation may differ somewhat in workplaces such as schools or universities. Educational buildings, which usually belong to various types of public authorities, often leave much to be desired regarding technical equipment and, consequently, the quality of the indoor environment. In the case of higher education institutions, employees usually perform work of a different nature (teaching, research, administrative activities), often changing rooms. Therefore, generalized conclusions regarding working from home must be accurately transferred to this group of employees. Moreover, the literature review suggests that scientific discipline also affects preferences.

Biglan classified different scientific disciplines using three dividing lines: soft/hard, pure/applied, and life/nonlife [

20]. The distinction between “soft” and “hard” disciplines refers to the different levels of acceptance of the set of theories that make up the discipline by the scientists in that field. “Hard” disciplines have a high degree of consensus, whereas “soft” disciplines have many different approaches and interpretations. Delgado [

21] pointed out interesting differences between academics active in “soft” and “hard” disciplines. Academics in soft disciplines consider WFH to have positively affected their research productivity, probably because conditions at home allow higher concentration on tasks. The opinions of scientists from “hard” disciplines about the impact of HFW on productivity are rather diverse and depend primarily on whether the scientific activity requires access to a laboratory. There were no differences between academics from soft and hard disciplines in terms of preferred forms of teaching. Remote teaching is considered a significantly worse experience than direct contact with students.

The most substantial positive aspects related to WFH identified in the study by Aczel et al. [

22] were less commuting, more control over time, more autonomy, fewer office-related distractions, a more comfortable environment, and more flexibility with domestic tasks. Conversely, the most damaging aspects of WFH were isolation from colleagues, less defined work-life boundaries, a higher need for self-discipline, reliance on private infrastructure, and communication difficulties with colleagues. Aspects of academic work preferred by the respondents performed at home were reading the literature, analyzing data, and working on manuscripts. At the university/institute, the investigated researchers preferred to concentrate on aspects related to teamwork (exchanging ideas and building relations) and aspects dependent on access to the infrastructure (IT infrastructure, library, laboratories).

Yet, young children present at home can be a significant distractor during academic work, affecting productivity. A study conducted in Australia [

23] found that a proportion of scientists who have toddlers at home reported more often reduced overall productivity (63% vs. 32%), reduced productivity in writing manuscripts (50% vs. 17%), and reduced productivity in data analysis (63% vs. 23%). The presence of primary school children was slightly less detracting but still affected productivity in writing manuscripts and generating new ideas.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Survey on the Assessment of Working Conditions and Productivity

During the ad hoc organized work from home during the COVID-19 pandemic, academic teachers working at the faculty commonly shared their views on the low effectiveness of the teaching process. They welcomed the return to classic forms of education. However, some students expressed satisfaction with remote learning, at least in some subjects. There was also interest from the educational market in postgraduate studies conducted in a remote or hybrid form. Many academics agreed to conduct lectures in this form because they had already gained experience in such teaching and had organized workplaces in their homes similar in comfort to the rooms at the faculty.

A survey organized within the Air Conditioning and Heating Department aimed to systematize staff opinions on the willingness and possibility of remote work. The survey also served as a pilot for collecting opinions about potential hybrid work during the planned modernization of the building.

The questionnaire contains 23 closed questions in which 43 fields had to be selected and 2 open questions for the free expression of opinion. The estimated time to answer the closed questions is 15-20 minutes. The survey designed in the MS Forms application was not anonymous, of which respondents were informed.

Most of the questions concerned the level of satisfaction or quality assessment. A scale with 5 potential answers was used: very low, low, average, high, or very high. The overall response rate was 83%. More detailed information is presented in

Table 1.

2.2. Division of Working Time for Academic Teachers

An average distribution of duties and working hours was adopted to conduct a preliminary analysis of the potential reduction in working hours for academic staff in the Faculty Building. This distribution reflects the teaching, organizational, and research responsibilities specified in the employment regulations at the Warsaw University of Technology (WUT). A representative group was identified as the staff of one of the seven departments within the faculty. When estimating the possibility of reducing the time students spend in the building, the analysis took into account the new teaching methods and programs currently being implemented at WUT, which include conducting some classes in an asynchronous online format. The assumptions used for the estimation are presented in

Table 2.

New teaching programs and techniques assume that a maximum of 30% of classes in Master’s programs and 7% of courses in Bachelor’s programs will be conducted using e-learning methods, primarily for lectures.

2.3. Measurements of Microclimate Parameters at Workplaces

With a view to later advice on the organization of workspace at home, measurement procedures were also developed to compare the parameters of the environment at the university and home. They are planned to be used at the request of employees who are unsatisfied with the work environment created at home. Different versions of the measurement procedure were tested in the work environments of one of the assistant professors (

Figure 3). The rooms with analyzed workplaces are compared in

Table 3.

When determining the details of the procedure, the available equipment, the interference with work by the measurements conducted, and the informativeness of the results were taken into account. Ultimately, it was decided that the basic microclimatic parameters (temperature and relative humidity) and CO2 concentration are measured simultaneously at both workstations during the working week of hybrid work (measurements lasting 5 days with a time step of 5 min). Parameters like TVOC, daylight, artificial light illuminance, and equivalent sound level LAeq are measured at least three times during one selected day of the analyzed week.

The following measuring equipment was used during the measurements:

Humidity range / accuracy; 0.1~99.9 % / ±2 %(10~95 % @ 25 °C) ±5% (others)

Temperature range / accuracy; -20...60 °C / ±0.3 °C @5~40 °C

CO2 measurement range/; accuracy 0...9999 ppm / (30 ppm +5 % of the measurements) @0~5000 ppm

Particle counter PC220 (Trotec) Mass concentration PM 2.5 and PM10, Measuring range 0-2000 µg/m3, resolution 1 µg/m3, Distribution of particle number channels (0.3; 0.5; 1.0; 2.5; 5.0; 10.0 µm) Counting efficiency 50% at 0.3 µm; 100% for particles > 0.45 µm according to ISO 21501)

TSI Multi-Function Instruments Model Ta465 Series + PID probe (984) 984 Low VOC range 10 to 20,000 ppb, Resolution 10 ppb

Logger HD31 with a radiometer (Delta), Light intensity (natural and artificial), lux (CIE n°69 – UNI 11142 - Class B)

KIMO DB100 sound level meter; Sound-pressure level (IEC 61672-1 - Class 2 /IEC 60651 - Class 2 / IEC 60804 - Class 2).

The analysis of residential indoor air exposures in Europe [

24,

25] indicates that PM2.5 is the primary health risk responsible for approximately 78% of all lost DALY (disability-adjusted life years). In Poland, PM2.5 is associated with 82% of roughly 6250 DALY/million lost yearly because of indoor air exposure. Therefore, it is foreseen that the measurements of PM2.5 will be analyzed especially carefully.

The measurement procedure will be supplemented with a brief description of the room in which the workplace is organized. Special attention will be paid to the performance of the ventilation system. Academics, specialists in ventilation, air-conditioning, and heating, will create a team that serves as a help desk for faculty members who need advice. It is foreseen that many recommendations may address ventilation performance, suggesting converting natural ventilation into hybrid mode [

26] or organizing do-it-yourself personal ventilation at the workplace at home [

27].

4. Results

4.1. Employee Survey Results

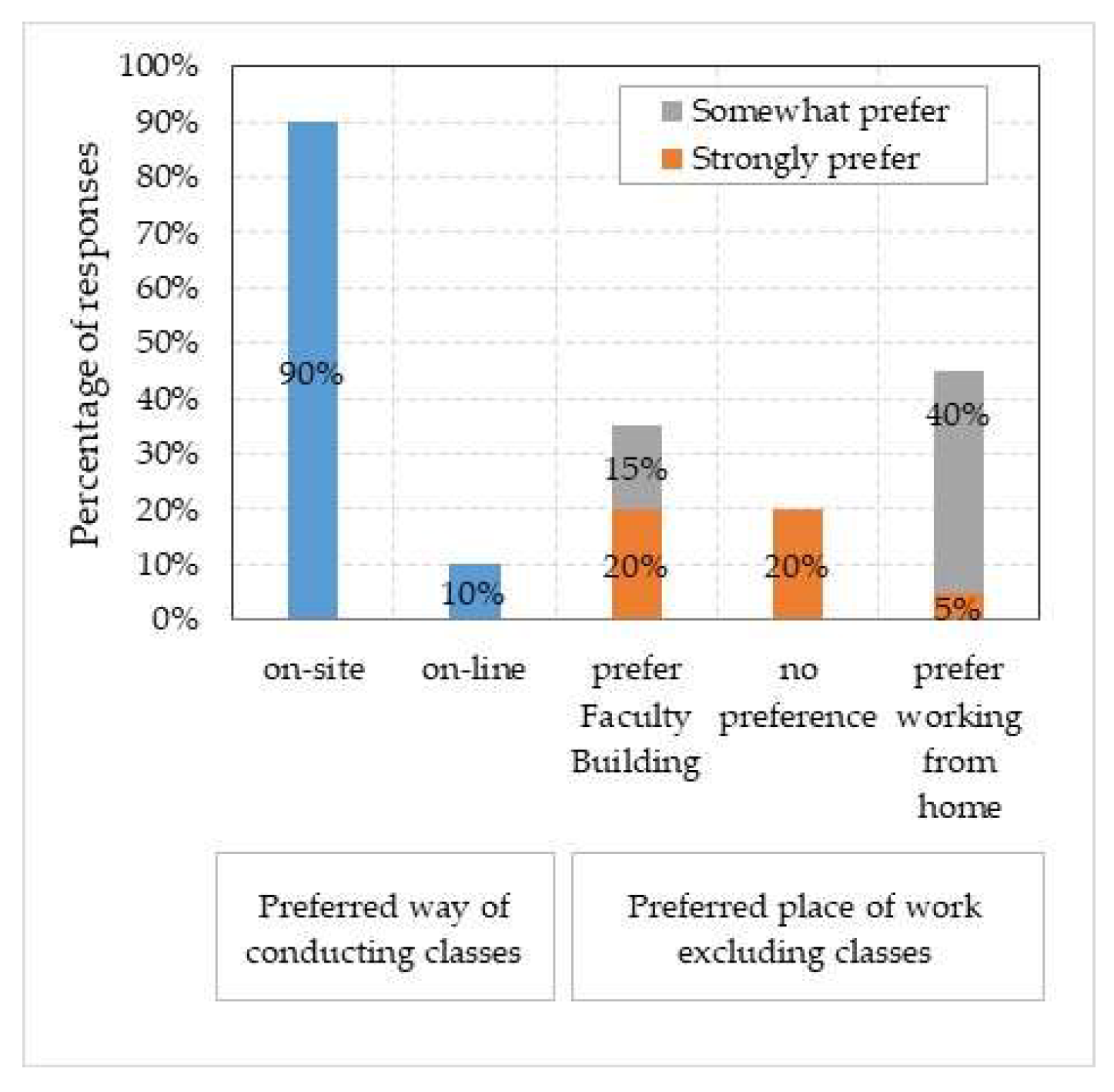

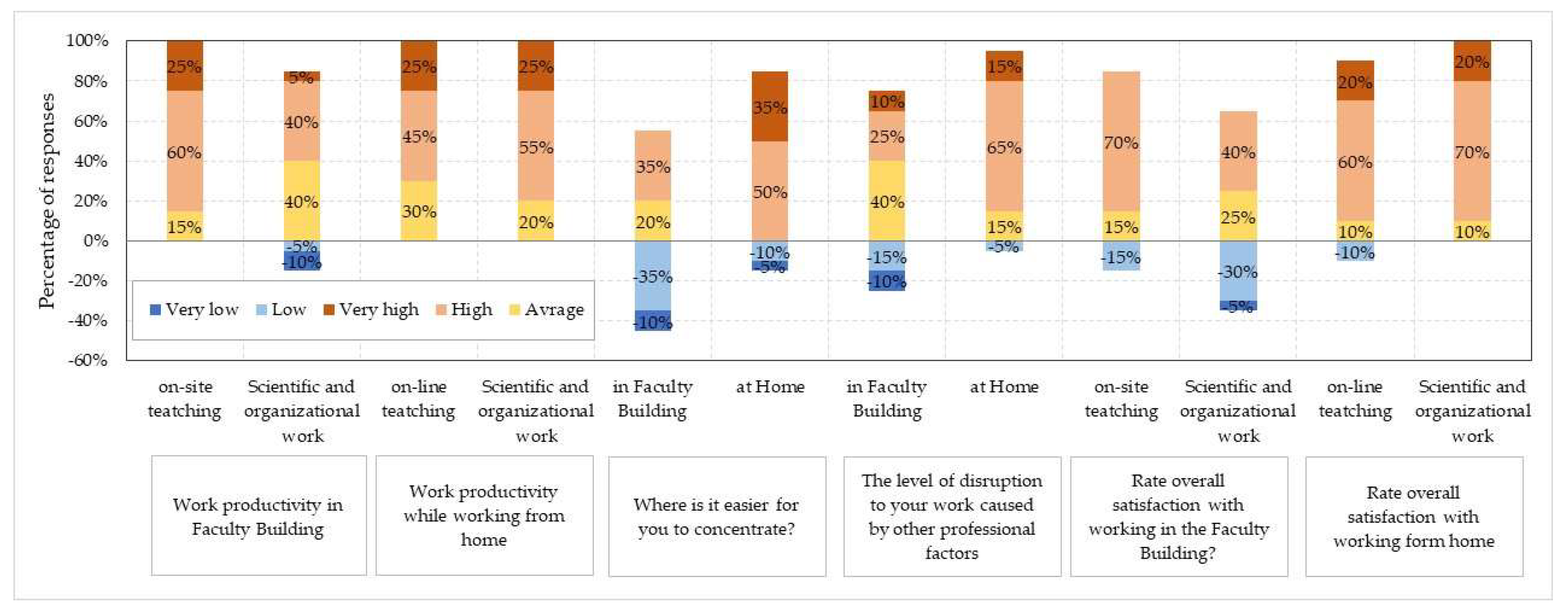

The survey revealed that the preferences for the place of work are strongly divided among the investigated group of academics. 45% of the staff prefer remote work from home, 35% prefer to work at the Faculty building, and 20% have no preferences. Regardless of the place of work, subjective assessment of the work efficiency is quite good – no one chose a low-level answer. However, remote work from home was rated better. Regardless of the tasks, 70-80% of the staff rated it highly. Only 45% rated their online teaching service from the University and administrative work efficiency highly in the faculty building, and 40% on average. On the other hand, the majority highly rated the efficiency of stationary teaching work at 85%. 90% of people also prefer conducting stationary teaching classes.

70% of people are satisfied with stationary teaching work at the faculty. However, only 25% are satisfied with teaching conducted online from the room at the faculty, and 40% have positive opinions about administrative and scientific tasks performed there. Regardless of the type of work, 80-90% are satisfied with working from home. This may be due to the possibility of focusing on tasks. 80-85% of people say it is easier to concentrate at home, and the same percentage say they have very few distractions.

Figure 4 and

Figure 5 present the survey results on workplace and class delivery preferences and subjective perceptions of work productivity.

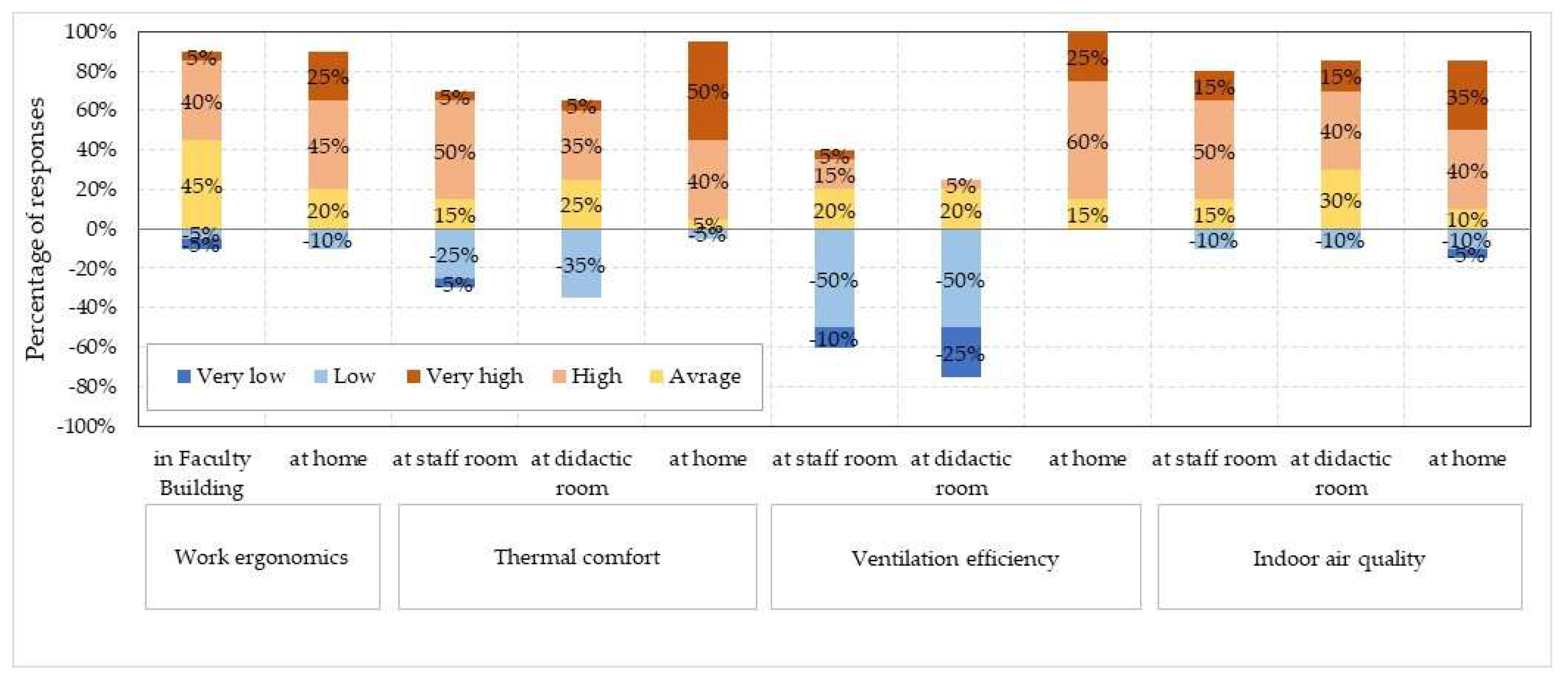

Investigated academics evaluated that home conditions provide high thermal comfort (90%), good ventilation (85%) and no pollution (75%). Contradictory to this, at the Faculty building, only 50% of academic staff perceived thermal comfort (more often in rooms than in auditoria). Approximately 70% of respondents negatively evaluate ventilation performance in auditoriums, while the prevalence of negative opinions about ventilation in staff rooms is slightly lower (60%). Surprisingly, only 15-20% of the staff report problems with air pollution.

Figure 6 presents the survey results on thermal comfort and air quality at workstations in the faculty building and at home.

About 50% of academic teachers working at the Faculty Building rate the availability of equipment for remote teaching from the faculty rooms as low. Respondents better evaluate technical equipment supporting teaching available in the auditoriums (20-30% of low votes). They estimate that the private equipment used at home is better, and only 15-20% consider its quality low. Workspace and ergonomics are rated slightly better at home (65-70% of people are satisfied) than at the Faculty (45-50% satisfied respondents). Auditoria were evaluated at the lowest; only 35% of persons were satisfied.

4.2. Microclimate Measurements at Workstations

The employee who agreed to make his workplace available for testing the measurement procedure prefers conducting teaching stationary. But for scientific and administrative work, he prefers working from home. He is convinced that at home, he’s better focused on the task, and his productivity is higher. He is unsatisfied with the thermal comfort, ventilation performance, and air quality provided by the faculty. Sometimes, he was unsure about his assessments, choosing the answer “hard to say,” but he made comprehensive explanations in open-ended questions.

Testing measurement procedures were conducted in November in the middle of the autumn semester. The final comparison used two sets of devices to measure basic environmental parameters during the working week. The academic irregularly worked in both locations. All teaching was delivered in personal contact with the students at the faculty. At home, he prepared a presentation for the conference and checked students’ projects. During WFH, we sometimes worked till late at night out of the typical working hours. The parameters affecting the comfort of work are resented in

Table 4.

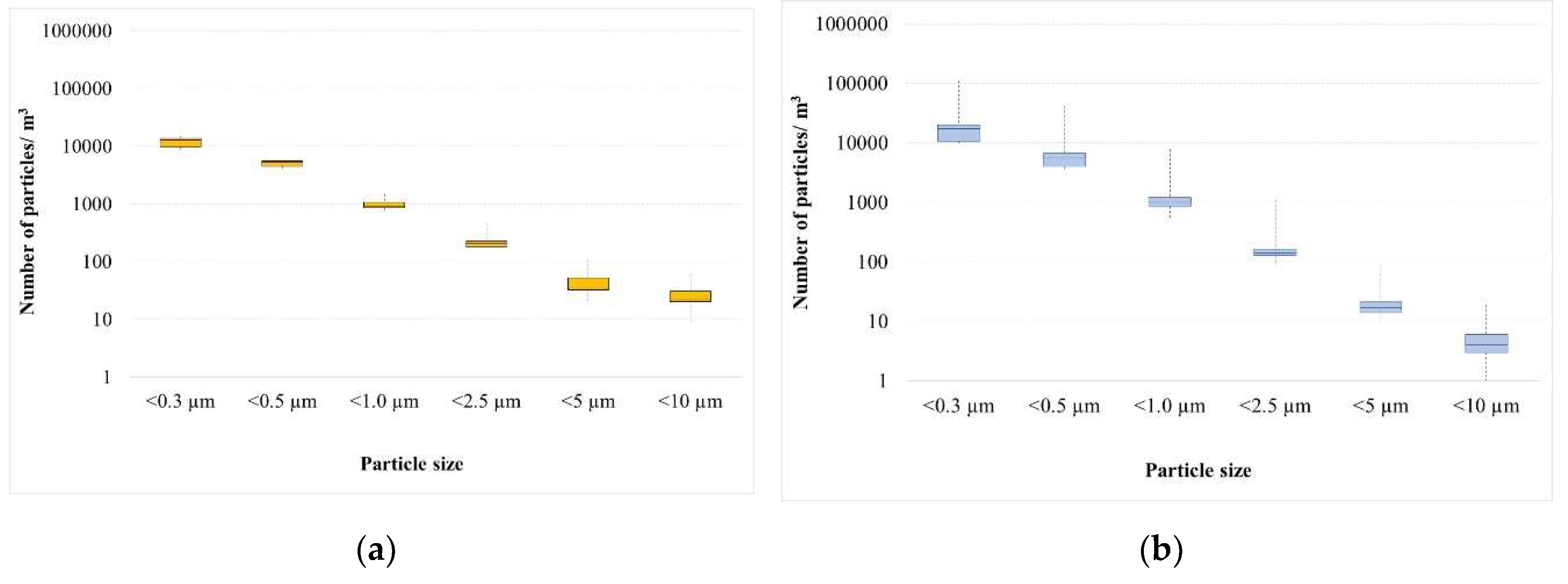

The box-and-whisker plots were used to compare the mass concentration of PM2.5 and PM10 (

Figure 7) and the distributions of particle numbers in six channels (

Figure 8). Observing the variability of data outside the upper and lower quartiles is worthwhile.

4.3. Analysis of Academics Working Time and Students’ Didactic Activities

If consider the academic staff of the Department of Air Conditioning and Heating as a representative sample of all academic teachers within the Faculty, survey results indicate that more than half of the respondents would willingly work remotely from home, excluding classes. The remaining respondents prefer working in the Faculty Building. Furthermore, considering the current transformation in education and the implementation of some lectures in an e-learning format, academic staff who favor remote work could also conduct these lectures from home. Under these assumptions, an average academic teacher spends approximately 15-20% of their annual time teaching students (excluding class preparation). Around 90% of the staff prefer conducting project and laboratory classes on-site while preferring lectures to be online.

Assuming that changes in education continue to promote asynchronous lectures, it can be estimated that about 25% of classes in Master’s programs and 5% in Bachelor’s programs will be conducted in an e-learning format. Further analysis of these assumptions, combined with the necessity for organizational and administrative duties requiring on-site presence (constituting an average of 15% of an academic teacher’s time, as defined by the Work Regulations), indicates that the minimum time spent in the Faculty Building would average around 35% of an academic teacher’s working hours. The remaining 65% could be performed remotely from home.

By implementing new teaching methods and conducting 30% of classes in Master’s programs and 7% in Bachelor’s programs via e-learning, it would be possible to reduce on-site teaching hours annually by approximately 450 hours for Master’s programs and 186 hours for Bachelor’s programs. However, this reduction accounts for merely 4% of the total teaching time for all student groups in a given year. Further analysis is conducted to increase this share.

5. Discussion

Opinions are relatively consistent with literature reports. Waszkiewicz et al. [

28] studied the preferences of different generations of workers, Baby Boomers, X-generation, Y-generation, and Z-generation (BB, X, Y, Z) regarding remote work after the COVID-19 pandemic. The results indicate that the most desired form of work is the hybrid model, preferred by 60% of respondents, while less than 10% expressed a desire to return to full-time on-site work. The results highlight that schedule flexibility and the ability to work from home were the primary advantages of remote academic work. Significant variation in opinions suggests that work from home should be voluntary: advice and support in organizing a work environment at home should be provided. Similar conclusions were found by researchers analyzing European [

29] and Middle East [

30] countries. They highlighted advantages such as greater flexibility and time savings on commuting. The disadvantages included a lack of social interaction, difficulties separating professional and personal life, and technological issues. The findings identified hybrid work as the optimal solution for many employees. The necessity of employer support for hybrid work, evident in survey results, is further confirmed by studies conducted by Babapur Chafi et al. [

31].

No correlation was found between an employee’s age and their preferences for remote work, unlike the findings of Bielińska-Dusza et al. [

32], who analyzed how different generations (BB, X, Y) perceive remote work in the public sector. Their results indicate that younger generations (Y and Z) favor remote work more than older ones (BB and X). However, there was no relationship between age and the assessment of technical issues or the impact of remote work on team relations. Similar results were presented by Muszyńska [

33], whose study also included academic employees.

It seems advisable to provide space for people who do not have the conditions to organize a workplace at home. This is supported by Capone’s research [

34], which examined the impact of remote work on the well-being and efficiency of academic staff in Italy. The results indicate that a high self-assessment of competence in remote work and organizational support positively influenced job satisfaction and psychological well-being. At the same time, the complexity of technology posed a challenge.

Generally, both investigated workplaces can be regarded as quite comfortable. At the regular workplace at the faculty, slightly better results were obtained regarding air temperature (minor fluctuations), carbon dioxide concentration, TVOC concentration, and artificial light intensity. The faculty room is heavily overheated in summer because of a big window facing south. Measurements carried out in November were unable to identify this phenomenon. The workplace at home was characterized by better relative air humidity, better daylight intensity, and lower noise levels.

Considering the health effects, lower concentrations of PM2.5 and PM10 dust fractions were also measured during work at home. The high concentrations of PM2.5 and PM10 dust observed at the faculty are causing concern. The faculty is close to the usually crowded street, approximately 200m from the measurement station PL0140A of the Inspectorate for Environmental Protection. The PM2.5 and PM10 concentrations reported from the station are the highest in the Warsaw region. Moreover, there are many books and paper documents in the analyzed room. High dust concentrations could also result from the resuspension of the settled dust.

During measurements in the house, a review of elements affecting ventilation performance was also carried out. It was recommended that the air vents placed in the window be cleaned more often and an opening below the room door be increased (Polish regulations require a cross-section of 80 cm

2 [

35]). The door threshold installed at the connection of two types of floor panels strongly reduces ventilation performance when the door is closed. It is foreseen that the recommendations for ventilation systems met at the staff homes can be much more serious in terms of number and complexity.

6. Conclusions

A thorough energy modernization of a university building without suspending its didactic and scientific operation is a difficult task in terms of organization. The selection of modernization variants, in which most construction works are performed from the outside, is not a sufficient solution. The concept of introducing temporary remote work and hybrid learning and scientific work is an interesting way to speed up the duration of modernization. This applies primarily to thorough modernizations, an example of which is the concept of modernization of the Faculty building. Analyses show that currently, 65% of employees would willingly or without significant difficulty work remotely, using the Faculty Building only for conducting classes. This would enable a 65% reduction in the time academic staff spend working in the Faculty Building. Based on survey results and microclimate measurements conducted at workplaces in both the Faculty Building and home, it can be concluded that working conditions are comparable in both cases. Most tasks that require only a computer can be effectively performed from home. Introducing a hot-desking model could significantly reduce the number of rooms occupied by academic staff.

However, students present a more significant challenge. The implemented e-learning methods would only allow for a 4% reduction in student groups’ time in the Faculty Building. Additionally, one cannot overlook the role of administrative staff, which further complicates the release of some administrative and teaching rooms.

The research has shown a wide diversity of opinions on working from home, which should be voluntary. In addition, the specificity of research and teaching tasks carried out by faculty employees should be considered when developing detailed plans for modernization works. At this stage of the work, it is recommended;

Identifying lectures that can be conducted remotely,

Introducing changes to teaching methods for subjects taught remotely to minimize the drop in the quality of education

Introducing changes to study plans so that subjects requiring the presence of faculty and students at the university do not overlap with intensive construction work

Identifying people who prefer working from home,

Developing instructions for preparing a productive workplace at home. The subject should include ergonomics, internet connections, appropriate ventilation,

Launching a help desk providing advice on ergonomic workstations, optimal microclimate for mental work, and appropriate configuration of computer equipment and internet connections

In ambiguous cases, at the request of interested employees, carrying out environmental measurements in homes (thermal comfort, air quality, noise).

Organizing temporary workplaces at the university in the part not covered by modernization works for people who are unable to work effectively from home

Developing rules for compensation for employees who decide to work from home (e.g., energy costs)

Verify the use of laboratories for the implementation of research grants.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Jerzy Sowa and Marta Chludzińska; Formal analysis, Marta Chludzińska; Funding acquisition, Jerzy Sowa; Investigation, Jerzy Sowa; Methodology, Jerzy Sowa; Project administration, Jerzy Sowa; Software, Marta Chludzińska; Supervision, Jerzy Sowa; Validation, Jerzy Sowa and Marta Chludzińska; Visualization, Jerzy Sowa and Marta Chludzińska; Writing – original draft, Jerzy Sowa and Marta Chludzińska; Writing – review & editing, Jerzy Sowa and Marta Chludzińska.

Funding

This paper was co-financed under the Warsaw University of Technology research grant, which supports scientific activity in the discipline “Civil Engineering, Geodesy, and Transport.”

Acknowledgments

The authors warmly thank colleagues from the Division of Air-conditioning and Heating at the Faculty of Building Services, Hydro, and Environmental Engineering at Warsaw University of Technology for sharing opinions about different aspects of working from home.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the study’s design, in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Mijakowski, M.; Koźmińska, U.; Kwiatkowski, J.; Rucińska, J.; Sowa, J., Concept of improving of indoor environment in a public building during planned modernization to nZEB, Healthy Buildings 2017 Europe, July 2-5, 2017, Lublin, Poland, Paper ID 0307 ISBN: 978-83-7947-232-1.

- Sowa, J.; Noga-Zygmunt, J.; Ugorowska, J.; Indoor air parameters in higher education building before planned modernization to nZEB standard, Healthy Buildings 2017 Europe, July 2-5, 2017, Lublin, Poland, Paper ID 0305 ISBN: 978-83-7947-232-1.

- Sowa, J.; Noga-Zygmunt, J.; Ugorowska, J.; Ocena parametrów powietrza wewnętrznego w budynku wyższej uczelni przed przewidywaną modernizacją do standardu niemal zero energetycznego, Fizyka Budowli w Teorii i Praktyce, tom IX, Nr 3, Instytut Fizyki Budowli Katarzyna i Piotr Klemm S.C., 2017, ISSN 1734-4891, str. 41-46, (2017).

- Mijakowski, M.; Rucińska, J.; Sowa, J.; Narowski, P.; Koncepcja poprawy środowiska wewnętrznego w przykładowym budynku użyteczności publicznej modernizowanym do standardu NZEB, Fizyka Budowli w Teorii i Praktyce, tom IX, Nr 4, Instytut Fizyki Budowli Katarzyna i Piotr Klemm S.C., 2017, ISSN 1734-4891, str. 15-20, (2017).

- Gajendran, R.S.; Harrison, D.A. The good, the bad, and the unknown about telecommuting: meta-analysis of psychological mediators and individual consequences. J Appl Psychol 2007, 92(6), 1524. [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D.; Golden, T.D.; Shockley, K.M. How effective is telecommuting? Assessing the status of our scientific findings. Psychol Sci Publ Int,2015, 16(2), 40-68. [CrossRef]

- Jensen, G.A. Telecommuting productivity: A case study on home-office distracters (Doctoral dissertation, University of Phoenix). December 2007.

- US Census Bureau. 2021. The Number of People Primarily Working From Home Tripled Between 2019 and 2021. Census.Gov. 2021. https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2022/people-working-from-home.html (Accessed 24.11.2024).

- Milasi, S.; González-Vázquez I.; Fernández-Macías E., Telework before the COVID-19 pandemic: Trends and drivers of differences across the EU, OECD Productivity Working Papers 2021, No. 21, OECD Publishing, Paris, . [CrossRef]

- Barrero, J.M.; Bloom N.; J. Davis, S.J. Why Working from Home Will Stick. Working Paper. Working Paper Series. National Bureau of Economic Research. 2021, . [CrossRef]

- Toniolo-Barrios, M.; Pitt, L., Mindfulness and the challenges of working from home in times of crisis. Bus Horizons, 2021 64(2), 189-197. [CrossRef]

- Wargocki, P.; Seppänen, O.; Anderson, J.; Boerstra, A.; Clements-Croome, D.; Fitzner, K.; Hanssen, S.O. Indoor climate and productivity in offices. REHVA Guidebook no. 6, 2006, ISBN 2-9600468-5-4.

- Sowa, J.; Tanabe, S.I.; Wargocki, P., Economic Consequences. In: Handbook of Indoor Air Quality Zhang, Y.; Hopke, P.K.; Mandin, C. Eds. Springer, Singapore, 2022 . [CrossRef]

- Healy, W.M.; Cetin, K.; Karg, R.; Sekhar, C.; Song, L.; Sowa, J.; Walker I,; Wargocki, P. Working from Home And the Impacts on Residential Buildings. ASHRAE J, 2024 66(3).

- Morawska, L.; Ayoko, G.A.; Bae, G.N.; Buonanno, G.; ... Wierzbicka, A., Airborne particles in the indoor environment of homes, schools, offices and aged care facilities: The main routes of exposure. Environ Int 2017, 108, 75-83. [CrossRef]

- Roh, T.; Moreno-Rangel, A.; Baek, J.; Obeng, A.; Hasan, N.T.; Carrillo, G., Indoor Air Quality and Health Outcomes in Employees Working from Home during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Pilot Study. Atmosphere 2021, 12, 1665. [CrossRef]

- Sarnosky, K.; M. Benden, L.; Cizmas, A.; et al.. Remote work and the environment: exploratory analysis of indoor air quality of commercial offices and the home office. Research Square. February 2021. Preprint, . [CrossRef]

- Pietrogrande, M.; Casari L.; Demaria G.; Russo M.. Indoor air quality in domestic environments during periods close to Italian COVID-19 lockdown. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021 18(8):4060. [CrossRef]

- Justo Alonso, M.; Moazami T.; Liu P.; Jørgensen R.; et al.. Assessing the indoor air quality and their predictor variable in 21 home offices during the COVID-19 pandemic in Norway. Build Environ 2022 225:109580. [CrossRef]

- Biglan, A., The characteristics of subject matter in different academic areas. J Appl Psychol 1973 57(3), 195. [CrossRef]

- Delgado, L., Academics Working from Home-Experiences & Challenges to Academic Work (Master’s thesis, NTNU). June 2020.

- Aczel, B.; Kovacs, M.; Szaszi, B., Researchers working from home: Benefits and challenges. Plos One, 2021 16(3), e0249127. [CrossRef]

- Chapman, D.G. Thamrin, C. Scientists in pyjamas: characterising the working arrangements and productivity of Australian medical researchers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Med J Australia, 2020 213(11), 516-520. [CrossRef]

- Hänninen O, Asikainen A (eds.): Efficient reduction of indoor exposures: Health benefits from optimizing ventilation, filtration and indoor source controls. National Institute for Health and Welfare (THL). Report 2/2013. Helsinki 2013.

- Asikainen, A., Carrer, P., Kephalopoulos, S. et al. Reducing burden of disease from residential indoor air exposures in Europe (HEALTHVENT project). Environ Health 2016, 15 (Suppl 1), S35. [CrossRef]

- Sowa, J.; Mijakowski, M. Humidity-Sensitive, Demand-Controlled Ventilation Applied to Multiunit Residential Building—Performance and Energy Consumption in Dfb Continental Climate. Energies 2020, 13, 6669. [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, A.; Łuczak, A.; Chludzińska, M.; & Zwolińska, M., The effect of personalized ventilation on work productivity. Int J Vent, 2012 11(1), 91-102. [CrossRef]

- Waszkiewicz, A., Praca zdalna po pandemii COVID-19 - preferencje pokoleń BB, X, Y, Z. 2022 e-mentor, 97(5), 36-52.

- Ipsen, C.; van Veldhoven, M.; Kirchner, K.; Hansen, J.P. Six Key Advantages and Disadvantages of Working from Home in Europe during COVID-19. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1826. [CrossRef]

- Alsulami, A.; Mabrouk, F.; Bousrih, J. Flexible Working Arrangements and Social Sustainability: Study on Women Academics Post-COVID-19. Sustainability 2023, 15, 544. [CrossRef]

- Babapour Chafi, M.; Hultberg, A.; Bozic Yams, N. Post-Pandemic Office Work: Perceived Challenges and Opportunities for a Sustainable Work Environment. Sustainability 2022, 14, 294. [CrossRef]

- Bielińska-Dusza, E., Hamerska, M., Praca zdalna na tle różnic międzypokoleniowych. Prace Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu, 2023 67(5), 22-37.

- Muszyńska, W., Stosunek pracowników z pokolenia Y i Z do pracy zdalnej w czasie trwania pandemii COVID-19 - analiza porównawcza, in Zrównoważony rozwój w kontekście współczesnych zmian społeczno-gospodarczych, 2022, 83--95.

- Capone, V., Schettino, G., Marino, L., Camerlingo, C., Smith, A., & Depolo, M. The new normal of remote work: exploring individual and organizational factors affecting work-related outcomes and well-being in academia. Frontiers in Psychology 2024, 15, . [CrossRef]

- PKN. Ventilation in Dwellings and Public Utility Buildings; PN-83/B-03430/Az:3 2000; Specifications Polish Committee for Standardization: Warsaw, Poland, 2000.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).