1. Introduction

Population aging is a fact that is systematically increasing worldwide, which has motivated the World Health Organization (WHO) to promote policies that increase the quality of life of the elderly, [

1,

2] which is valid in the field of Primary Health Care (PHC) and the first level of care.

In this context, Chile projects a negative vegetative growth in the groups under 15 and 15 to 60 years of age by the end of the 21st century; by 2050, it is expected that those over 60 will exceed those under 15 years of age in the country for the first time. [

3,

4]

It is known that aging is part of the life course and sexuality of people. According to the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), sexual health is understood as a state of physical, mental and social well-being in relation to sexuality; and it is not the absence of disease, dysfunction or disability, since it incorporates a rights and gender approach in order to have pleasant and safe sexual experiences throughout life, free of coercion, discrimination and violence, which are respected, protected and exercised to the fullest. [

5]

For the American Sexual Health Association, [

6] sexual health is the ability to embrace and enjoy sexuality throughout life; it is part of physical, emotional and sexual health. The latter involves understanding that sexuality is connatural to life and is more than sexual behavior; it is recognizing and respecting sexual rights; having access to health information, education and sexual care; making an effort to prevent unwanted Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs), with care and treatment when necessary; being able to experience sexual pleasure, satisfaction and intimacy when desired; and being able to communicate about sexual health with others, including sexual partners and health care providers.

In older people, in addition to coital activity, kissing, cuddling, flirting, caressing, masturbation and bodily or emotional acts of intimacy are added to sexual activity. [

7]

In Chile, 60% of older people aged 60 and over consider sex life to be important; 50.1% of men and 22.5% of women reported having an active sex life. [

8] However, studies and explorations on sexuality among older people are scarce in the country. This, added to the previous justification, are strong reasons to have the purpose of investigating the topic in the Chilean population in the territorial context related to PHC.

In this regard, sexuality is an intrinsic quality of human beings and an essential part of people's identity, since it is a source of well-being and pleasure, capable of enriching their lives. [

9] Furthermore, different authors have shown that there is an association between an active sexual life and a better quality of personal life and satisfaction with one's partner. [

10,

11]

In addition to the above, the evidence indicates that the sexual area in general, and in older people in particular, is not part of the planned actions in health care at the first level of care or PHC, due to training deficits of health professionals in this area and, in part, affects the quality of sexual life of older people, [

12,

13,

14] which increases with the research gap in the field regarding what are the dimensions that exist in thinking about sexuality in older people in Chile.

In accordance with all the above, the research question is: what are the dimensions of sexuality that underlie in the elderly and what are the contents in the daily experience of sexuality? In order to answer this research question, the objective is to explore the relevant dimensions of sexuality in older people who participate in territorial organizations related to Primary Health Care in Chile, which will allow finding content and deep representations associated with sexual experiences.

2. Materials and Methods

The research is a mixed exploratory study (qualitative-quantitative), which used the technique of focus groups at the community level with elderly people, based on a semi-structured guideline of questions of approximately 45 minutes' duration. The groups were of three types: women, men and mixed, of which one was carried out in the northern zone (commune of Vallenar, III region), eight in the central zone, Metropolitan Region of Santiago (3 in the commune of Maipú, 3 in the commune of Ñuñoa, 2 in the commune of Pedro Aguirre Cerda) and one in the central southern zone of the country (commune of Talca). The participants did not receive economic compensation for their participation.

In order to unveil the latent and underlying meanings in the stories of the elderly, the Grounded Theory methodology was applied, which allowed the development of the theory that is rooted (“grounded”) in the information collected and systematically analyzed. [

15]

The sample of elderly people was determined from the deep understanding of the phenomenon rather than by the extension of the number of participants. The analysis of the information made it possible to structure a series of dimensions with their sub-dimensions, which were organized quantitatively according to their relative level of importance (

Table 1).

A non-probabilistic theoretical sampling by convenience was used, which is more in accordance with the grounded theory and the objective of the study.

The inclusion criteria of the study were to be 60 years of age or older, to participate in community groups, people residing in the selected areas, in good physical and psychological health, of any socioeconomic level, marital status and sexual orientation. The exclusion criteria were: being an elderly person with severe or total dependence, elderly people residing in long-stay facilities, elderly people with severe cognitive impairment and/or Alzheimer's disease.

The interviews were recorded after the participants signed an informed consent form. The accounts were transcribed by an external person not involved in the research. The texts were incorporated and analyzed in the computer system for analysis of mixed studies MAXQDA 2023, from which an inductive and deductive work was carried out that allowed the axial coding of the contents and the generation of the emerging dimensions and subdimensions rooted in the sexuality of the participants.

The research was approved by the ethics committee of the Faculty of Medicine of the University of Chile.

3. Results

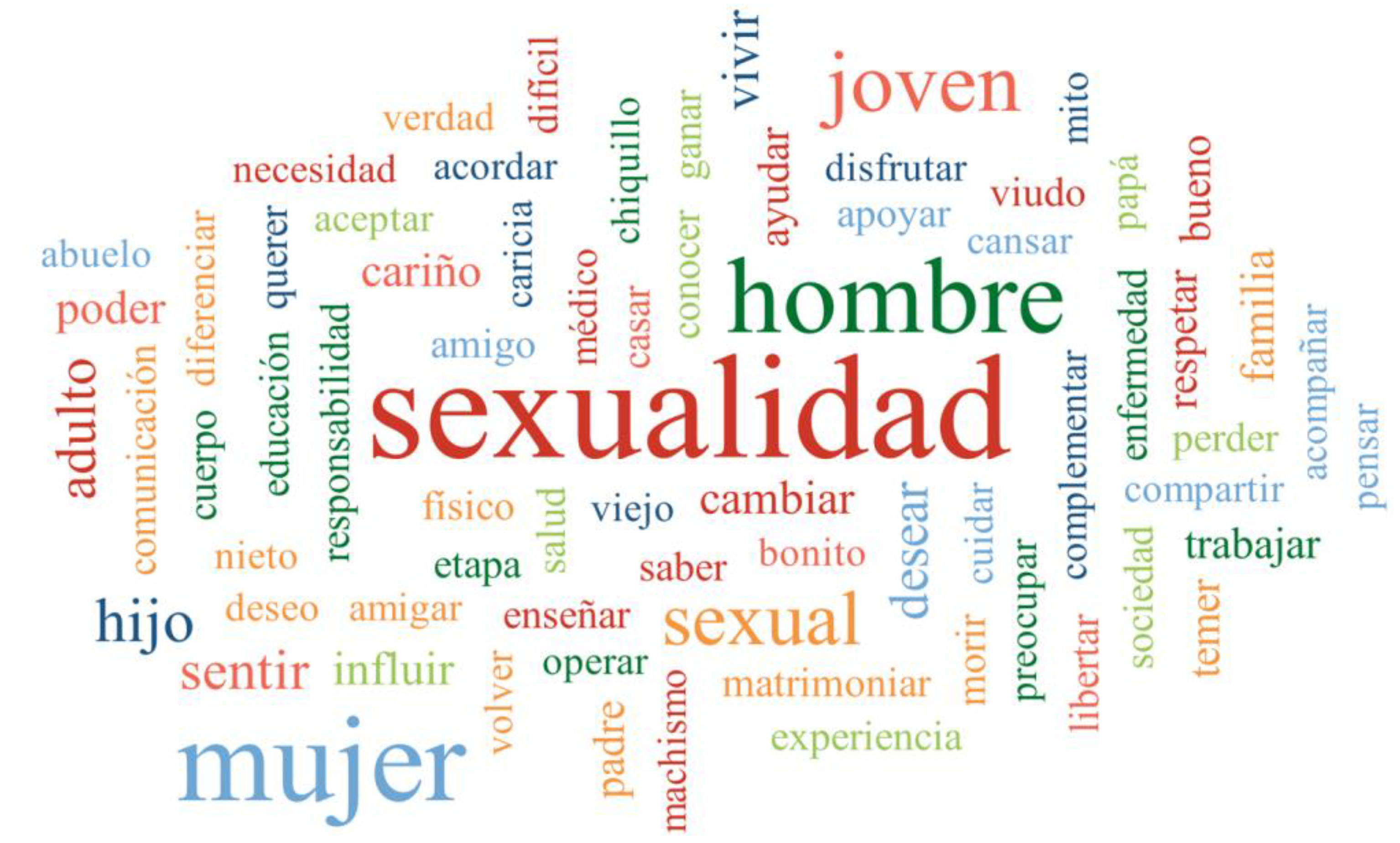

In the 10 focus groups conducted with older people, 52 women (62%) and 33 men (38%) participated. With the opinions and stories given, a word cloud was formed that shows the importance that sexuality and sex have for the interviewees, as well as the relationship that this has in gender relations within the family, where there is a diversity of important biopsychosocial, communicational, value and spiritual aspects (

Figure 1).

3.1. Dimensions and sub-dimensions

The research found 10 emerging dimensions and 42 sub-dimensions from the participants' accounts, which are shown in

Table 1 according to their relative importance.

3.1.1. Dimension 1: sexuality and older persons

The dimension “sexuality” emerged as the most talked about and the result is consistent with the word cloud found, and that published by other research [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14], which demonstrates the depth, extent and breadth that the topic has in older people.

Subdimensions

Gender identity: this is understood by the interviewees as diverse experiences, thoughts and feelings of participation in the development of sexuality and sexual health: “as a woman I also go to bed tired, sometimes one prepares oneself mentally to be able to say today I want to be with my partner, with my husband and make love” (Mixed Group Maipú: 131).

Love relationships: older people understand sexuality as more than a mere sexual act, but as integral acts that involve values and love with the partner: “at least I am enjoying my sexuality, my husband is very affectionate, he is 60 years old, he is attentive, concerned about me and the daughters... he is sexually active, the normal thing I think, even if I tell him no, he accepts it. There is respect between us. I would like it to stay that way forever” (Talca Women's Group: 82). “I can say that my husband is very attentive, he takes care of me, he treats me well, he does things for me, that keeps me alive for him” (Mixed Group Vallenar: 23).

Satisfaction and fulfillment: it is the expression of being fulfilled with the partner with acts that go beyond the sexual sphere, and includes the psychoemotional and spiritual: “to satisfy is not the same as making love, in other words, to have sex is not necessarily to satisfy the other. Sometimes you have to have sex so that the man does not get angry, sometimes it is just satisfaction for him” (Maipú Women's Group: 16).

Caresses: these are acts to which older people attribute a high value, with or without coital activity: “it is having sex in a different way than when you are young, it is a relationship that feels more affectionate, it is caressing each other, it is being together for life” (Mixed Group Vallenar: 3).

3.1.2. Dimension 2: problems and sexuality in PM

This dimension emerged from the relationship that older persons make between different problems and sexuality based on age, health problems, physical exhaustion, loss of desire, among others.

Subdimensions

Transformations and changes: it emerges as the explanation of some interviewees about social changes that affect the elderly: “Today it affects that grandmothers are in charge of raising the grandchildren, there is no time or there is less time and one is tired” (Mixed Group Vallenar: 46).

Decrease in sexual capacity and power: interviewees understand it as the loss of sexual capacity and power that occurs with age, which is based on serious illnesses, the use of medications, trauma, parenting problems, abuse and rape, among others: “I do not know if it is so, that diabetics and hypertensives are lowering their level of sexuality, and I am in the diabetic and hypertensive plan, and I do not feel every day like being with my husband, nothing happens, because he comes to purely sleep, it is a boring life” (Mixed Group Ñuñoa: 97).

3.1.3. Dimension 3: sex and orgasm according to Older People

This is a relevant dimension that is still alive in older people, who relate how it is necessary for mental and sexual health and quality of life, which is affected by deteriorating health, social stigmas, widowhood, myths and beliefs, and changes inherent to this life cycle, such as a decrease in intensity and frequency, among others.

Subdimensions

Sexual relations: in general, older people understand it as the ability to have coital activity to satisfy the biological need for sexual desire associated with expressions of love: “I have no problem reaching orgasm. We do a little bit of everything, masturbation, penetration, at this age when one does not have problems with children, one is more relaxed” (Grupo Mujeres Pedro Aguirre Cerda: 8). “Yes, we have sex. Once a week, sometimes every two weeks, it depends on the mood. We have sex, we get along well” (Grupo Mujeres Pedro Aguirre Cerda: 3).

Affective relationships: this is a concept valued by older people, which explains affective sexual behaviors with the partner, which is sometimes more important than coital activity: “showing affection is part of sexuality, it is a complement in coexistence” (Men's Group Pedro Aguirre Cerda: 8). “But the other part is needed, affection and affection. Someone who cares about you, who embraces you when you are alone” (Grupo Mujeres Talca: 22).

Forced coital loss: this occurs when one of the partners decides to stop having coital relations: “I will say that it has been 20 years since my affair died, I separated from my husband and that's it, I have other things to do, so I put it on the back burner” (Grupo Mujeres Pedro Aguirre Cerda: 77). “In my case, my husband is 71 years old and overnight he stopped having sex, he left me ... I am 63 years old and I miss sex, because I like sex” (Grupo Mujeres Talca: 16).

Non-coital relations: this is a concept that explains coital inactivity, remaining in a sexuality of sharing, coexistence, caresses and corporal love without coital relations: “I have been married for 41 years ... since I got sick with my kidneys, because of a care issue, we do not have sex or anything, my husband takes care that something does not happen to me, and I do not feel what I felt before” (Women's Group Pedro Aguirre Cerda: 13). “He could not and I insisted that he go to the doctor; in the end, it is not so much the penetration, but the affection you feel when he is next to you, hugs you and gives you a kiss”. (Talca Women's Group: 18).

3.1.4. Dimension 4: values, sexuality and Older Persons

It refers to those values that society accepts from the moral point of view related to the sexuality of the elderly.

Subdimensions

Communication: appears as a concept that permeates people's sexuality through the formation of children, social relations, intrafamily or school education. The interviewees emphasize the importance of communication in sexual activity, as expressions of affection, affection and love in the couple: “we have sex because we both want to, it's as simple as that. We both start to conquer each other, no difficulty in reaching orgasm. I feel that I am alive. He has no problems reaching erection, I believe that communication is from both of us, and from my part to conquer him” (Grupo Mujeres Pedro Aguirre Cerda: 5). “Sexuality is communication, it is feeling like a queen when one is told that I am his love, I want him to touch me”. (Maipú Women's Group: 9).

Feelings: this is the affective and emotional part involved in the couple's relationship, where affection and good treatment are necessary for the expression of sexuality. Feelings generate positions of comfort and discomfort depending on the context: “sexuality is a path of many suns, sexuality is feelings and attraction for the purpose of looking for a partner” (Ñuñoa Men's Group: 7).

Satisfaction and happiness: the interviewees understand it as joint sexual development, sexual enjoyment, harmony and fulfillment, which is reinforced by the psychoemotional and spiritual stability of the couple: “for me sexuality is the satisfaction of a person's need; my opinion of man is the desire to love, to show affection, which is necessary and healthy” (Mixed Group Vallenar: 22).

Respect: the older persons mention it as a value that is exercised in terms of the couple's way of being, thinking, values, feelings and emotions, or in wanting or not wanting to have sexual relations: “sexuality in a couple is basically love, trust, respect, responsibility, loyalty and honesty” (Ñuñoa Women's Group: 50).

3.1.5. Dimension 5: desire(s), attraction in Older People

Desire appears in the interviewees as something important, linked to beliefs, myths or sexual discrimination. There is consensus that it should be kept alive, with a different intensity than when one was young. It is an angular concept of femininity, masculinity and coquetry.

Subdimensions

Sexual desire: is what accompanies sexual activity. It is inherent to people and should be kept alive, with nuances specific to this life cycle: “I have desire, we connect and he takes the initiative, we are mentally connected” (Grupo Mujeres Pedro Aguirre Cerda: 8). “One thinks of a new opportunity, with a woman with certain similarities, and feeling sexual desire with a partner similar to oneself, who gets along with one, I think of a second chance” (Men's Group Ñuñoa: 5).

Intensity of desire: the interviewees see it as something key for the good development of sexual or coital activity, which varies with advancing age: “the intensity changes with maturity and the passing of the years. The intensity is not the same at 20 than at 70, but the affection is still the same. Sexual relations exist, but from time to time, because now the intensity and frequency has decreased” (Ñuñoa Men's Group: 17).

Eroticization: it is described as important and necessary, both individually and as a couple: “Yes, because massaging, affection, masturbation, is eroticization. I think that older people do it” (Maipú Women's Group: 21). “I say that the sensation and eroticization exists, I feel it” (Ñuñoa Men's Group: 36).

3.1.6. Dimension 6: Health care CESFAM or others and PM

This dimension reflects experiences lived in health care related to sexual health, with discrimination or rejection of the topic sexuality by doctors and other health professionals, who in the opinion of the interviewees are not prepared in this topic (diagnosis, treatment, use of drugs), which negatively affects the sexual and mental health of the elderly.

Subdimensions

Diseases: these are mentioned because they affect the sexual performance of older couples: “diseases affect a lot, you cannot have sex when you are sick, the ailments of diabetes and high blood pressure affect” (Maipú Women's Group: 29). “With the years, the different diseases also have an influence, the older you get, the less sexual appetite and all that” (Grupo Mujeres Pedro Aguirre Cerda: 15).

Sexual health: is mentioned by some older people as a state of sexual well-being in the couple, feeling harmony, respect, affection and active coital activity. Frequency is not relevant in the sexual health of men, but it is in women, ideally weekly or no more than two weeks: “we have been a couple for 42 years, we have sexual relations once or twice a week” (Grupo Mujeres Pedro Aguirre Cerda: 5).

Mental health: it is clear from the interviews that mental health is directly related to sexual health, for example, the importance of staying active in sex for mental health and how this is affected by the loss of sexual activity. It is also affected by macho behavior, work, economic causes, stress, fatigue, illness, etc., which distances the couple's relationship: “the CESFAM has hurt me a lot, I started as a pre-diabetic, pre-hypertensive, pre-anticoagulant disease, and I got sick just the same. The same thing happens with sexuality, nobody helps you” (Ñuñoa Mixed Group: 21). “The importance of the socioeconomic variable is vital for better living conditions, better housing, better education and how this has a favorable influence on good mental health and sexual health” (Ñuñoa Men's Group: 19).

Medical abandonment and health professionals: the interviewees, in general, make a deep criticism of the health system and health professionals, there is a feeling of abandonment in the area of sexuality and sexual problems. The stories show that professionals are not in charge of this area and state that they are not prepared in this matter: “they never ask us anything, it is very necessary to address sexuality issues, one does not have anyone to ask questions to, nor anyone to ask” (Maipú Women's Group: 38). “I would like doctors to ask if we have any sexuality problems, or that we can ask them too. They don't give themselves the time for these things” (Maipú Women's Group: 39). “In my experience, these sexuality issues are not touched in the CESFAMs, we have never seen it and they are of the utmost importance” (Men's Group Ñuñoa: 46). “Professionals are not prepared, and older people do not want to ask either because they do not have time” (Women's Group Ñuñoa: 44).

3.1.7. Dimension 7: education, training in sexuality in PC

This dimension refers to key concepts of sexuality that should be learned, in general, associated with the importance given to it by the family, parents, schools and society; and that influence sexuality training in children and young people.

Subdimensions

Family and sexuality: the interviewees mention it as something that parents and grandparents cannot avoid or delegate, it is a responsibility that they must assume, but in an updated way, without myths or taboos, without religious influences and dogmas, which is fundamental for a healthy sexuality and sexual health in the future of the person: “education should be given in schools, but each family has its own ethical and moral structure, this education should be in the family” (Ñuñoa Men's Group: 27). “I grew up with my grandmother and she was not in charge of my sexual education, they were topics that were forbidden” (Mixed Group Vallenar: 50).

Upbringing: refers to past upbringing models and how these influenced in a negative way the sexuality of older people: “perhaps there are many concerns and because of upbringing people do not dare to consult other people, they do not even dare to ask a doctor” (Ñuñoa Women's Group: 19). “It depends on both parents, it depends a lot on the upbringing that one has had since childhood from her parents” (Maipú Women's Group: 25).

Sex education in schools: this is something that the interviewees see as mandatory in the country's schools: “there is a lack of sexuality education for older people because the better the sex education, the better the stimuli and the better the way of dealing with it” (Ñuñoa Mixed Group: 42). “They made you see sex as very morbid, in our generation sex was a sin, sex was dirty, they instilled in me that sex was bad because men wanted you to have sex” (Mixed Group Pedro Aguirre Cerda: 70).

Lack of information: here the interviewees refer to the lack of information from parents and children of previous generations (now older people): “we men had to look for information from our partners, in women's magazines, because in my house they did not talk about sex, it was taboo, it was morbid and dirty” (Mixed Group Pedro Aguirre Cerda: 154).

Social networks: it is mentioned in the context of meeting partners through social networks such as Facebook, Tinder to have sex or start relationships: “there are people who meet through Facebook, they gradually get to know each other and get married. I do not like social networks for this” (Maipú Women's Group: 40).

3.1.8. Dimension 8: difference(s), sexuality and FP

This refers to the differences that exist between older and younger people, between older men and women, in the way of accepting sexuality, in sexual experiences, in the different diseases they face, in sexual capacity, among others.

Subdimensions

Generation gap: some interviewees refer to the differences (training, freedoms, values, care, etc.) that exist in how older people see and deal with sexuality compared to young people today: “in my time ... dating was long, your parents had to know, you could not go out because they did not let you go out anywhere without company” (Mixed Group Pedro Aguirre Cerda: 70). “Today they are freer, we see debauchery, today they talk and do things in sexuality that they could not do before” (Ñuñoa Men's Group: 21).

Acceptance of differences: the differences are mentioned in terms of the couple, with respect to life cycles, different physical and psychological capacities, aging with different diseases; all of which affect sexuality: “there must be patience for each other, not to be stubborn with the couple, even if there are differences, we must try not to go against and we must give in to the couple” (Mixed Group Vallenar: 25). “One looks like a disgusting person, after 60 years together, it is no longer the same” (Mixed Group Vallenar: 12).

Young people and easy sex: seen as a criticism of young people for the lightness and freedom of how they live sexuality: “Now everything is easy, I don't criticize it either, but sex is very fast, they don't value intimacy. There is nothing more intimate than giving one's body to another, so they do not respect it, it is like a game” (Mixed Group Pedro Aguirre Cerda: 72).

Dimension 9: sexuality and rights of the elderly

This dimension is seen as a series of values and rights that occur at the social level and that relate to or affect the sexuality of the elderly.

Subdimensions

Freedom: in general, there is consensus among those interviewed that young people are freer in sexuality, that they do not question themselves, that they have sex without prejudice, sometimes with debauchery. It is also seen as the freedom of women oppressed by machismo or religious prejudices that mark sexual development with prohibitions; or the freedom of oppressed women who separate; or that driven by feminism: “perhaps the greater information that young people have associated with more freedom makes them be very free in their sexuality, to identify with different sexual forms” (Ñuñoa Women's Group: 21).

Mistreatment/sexual abuse: some older people relate this from experiences of sexuality, social discrimination, mistreatment due to machismo or religious expressions: “I have never said this, at the age of 5 I was raped by a man, there was no penetration, but he abused me a lot. Although I got married, I suffered a lot ... it was tremendous, having sex was tremendous, fortunately my husband had prostate cancer and sexual activity ceased” (Ñuñoa Mixed Group: 28).

Machismo: mentioned as a form of upbringing, as a stereotype learned in the family, with different roles for life, mixed with myths and beliefs, which marked the development of sexuality: “machismo marks one, it hurts deeply when you are treated badly, when you are treated as an employee ... it makes you disappointed, and you lose your desire” (Mixed Group Vallenar: 21). “I regret not having helped my wife more, with time I realized my machismo and not having cooperated more” (Men's Group Ñuñoa: 10).

Feminism: the interviewees understand it as an expression of right that they recognize is part of a current feminist movement, which, although they share, they also show the differences regarding the ways or forms of exercising it: “now women do that, because they are more vivacious or accelerated, and if there is no sex here in the house, they look outside” (Women's Group Talca: 26). “In the case of women, I also think that they should enjoy sex, with care, well informed and with responsibility. It is good to empower women in this sense” (Maipú Women's Group: 29).

Dimension 10: society, PM and sexuality

This dimension highlights the importance of social and cultural phenomena in the sexuality of the elderly, with different variables that have a positive or negative influence on the sexual sphere.

Subdimensions

Biopsychosocial approach: the interviewees highlight from this perspective the economic problems they face; they mention in general the non-acceptance of sexual diversity, the lack of sexual training in the family, the discrimination they experience, the lack of understanding of partners. They also question the lack of biopsychosocial training of doctors today: “that doctors have a more biopsychosocial, more holistic look” (Maipú Women's Group: 50). “Social pressure affects the psyche a lot, living and working in neighborhoods with delinquents stresses and affects our family sexuality ...” (Ñuñoa Men Group: 43). “With age comes the idea that old people are useless, that they do not respond, that they are no longer capable and that society looks down on them in relation to sexuality. It is frowned upon for older adults to have sex” (Vallenar Mixed Group: 5).

Culture: is understood by the interviewees as a concept that has an impact on sexuality, as it is influenced by myths, beliefs, experiences, treatment or family mistreatment, with positive or negative family experiences that influence the future expression of sexuality: “it is very difficult for me to accept that same-sex relationships ‘are normal’, it is difficult for me to accept it culturally” (Ñuñoa Mixed Group: 16). “Culture also influences ageism, as sexuality is still a taboo in Chile, it is not talked about in childhood, adolescence and youth” (Maipú Women's Group: 17).

The future and sexuality: the interviewees look positively at sexuality in the future, with positive growth experiences, with technological and scientific development that they believe will positively affect sexuality, health and sexual capacity: “sexuality with science will be better in the future, and not only sexuality but many other things that will make life easier” (Ñuñoa Men's Group: 25). “Young people have fewer barriers, they are more natural, they will also face their sexuality better in the future” (Mixed Group Ñuñoa: 49). “I believe that sexuality will be better in the future, with more education and culture, everything is discussed, it is more open” (Maipú Women's Group: 48).

4. Discussion

The main limitation of the study was not having taken groups from the most extreme areas of the country (extreme north and south) in order to add experiences and stories from all over the country to the groups studied. In spite of this limitation, the results found show an updated reality of the sexuality of older persons residing in the selected geographical regions, which allow configuring diverse experiential and theoretical representations related to behaviors, behaviors and attitudes associated with sexuality and sexual quality of life of the interviewees.

The research corroborates the importance that older people give to sexuality, as has been shown in other research, [

10,

16,

17,

18,

19] and in this case, with 10 dimensions and 42 sub-dimensions emerging in the interviewed older people residing in the three geographical areas of the country.

In the research, both older men and women were willing and open to talk about sexuality, which differs from the findings of Soares and Meneghel, where one of the dimensions found was “difficulty in talking about sexuality/sex”, however, as in this research, differences were found by gender in the subject matter. [

20]

That the sexuality dimension is the main category is not an isolated phenomenon, since other authors have also commented on the importance that older people give to sexuality in old age, according to gender identities, experiences and feelings of a unique and particular sexual activity. [

19,

21,

22,

23]

Although the accounts of sexuality in the research show older people with traditional gender roles according to the broad and hierarchical approach to the conception of sex, [

21] and socially and culturally marked by the gold standard of vaginal penetration and intercourse, [

10,

24] in this research some complementary dimensions appear such as affective sexual relationships, love relationships, non-coital relationships, the importance of caresses, among others, which is also consistent with other research. [

18,

21,

22,

25]

However, the importance of vaginal and penetrative sexual activity has also been demonstrated, which is greater in men than in women, and where individual masturbation is also important in the elderly. [

26]

As in the research of Gore-Gorszewska G., [

27] dimensions 2, 3 and 5 of the research represent a sexuality focused on the activity that transits through the different life cycles, by showing a natural decrease of sex as coitus in older people, [

28] even more so if there is no partner; which is consistent with studies that show that sexual activity is greater when being in a couple. [

29,

30]

In dimensions 3, 6 and 8, sexuality is part of intimate relationships of desire and physical pleasure (sex as experiences and intimacy); unlike the findings of Vieira K, [

31] where due to lack of knowledge, taboo and cultural pressure, the older persons studied experienced guilt and shame for feeling sexual desire. Although sexuality and the sexual act are a space of emotional intimacy, they do not reach more symbolic and deep representations that make them see sex as the art of feeling a mental enjoyment for the enjoyment of the partner.

However, the research found conservative sociocultural ideas associated with gender and masculinity, which are in line with other research that shows how older men live with physical or biological problems of erection, absence of a partner or others, which deteriorate the image of masculinity and generate negative emotions. [

32,

33]

In the same sense, there are other researchers who suggest that diseases such as prostate cancer have a negative influence on the physical, psychosocial and emotional capacity of men, so biopsychosocial programs should be managed to support older men living with this condition. [

34]

Although there is a macho representation in women of living sexuality and the sexual act to satisfy men, [

21,

35] in this study there was also a more updated experience that privileges the sexual satisfaction of women, unmarked from a conservative orientation and rather focused on sexual satisfaction, in some cases, with feelings of deep love towards their partners, which is above sociocultural differences. [

23,

36]

Like other researches, [

21,

24,

37] there appear scripts that represent an evolution of sexuality from mutual experiences, of equality and honesty, which allows the development of deep and rich feelings in couple, which increases sexual satisfaction, which agrees with researches where sexual activity and satisfaction is associated to life in couple. [

30]

In the same idea, dimensions 1 and 4 of the research show the relationship between sexual activity and value, emotional and communicational aspects (sex as emotional intimacy), which is consistent with the findings of Arias-Castillo L et al. [

19]

The research found a negative impact on sexuality due to the lack of sexual education of the interviewees, which has also been demonstrated by other studies, [

12,

23] in addition to a conservative education linked to the dogmas of the Catholic religion that hinder the idea of living sexuality freely at this age, especially if it is lived in long-term relationships.

In spite of the above, there are studies that demonstrate the relationship between a higher educational level and a greater satisfaction with the quality of the relationship, a more active sexual life, with a greater frequency of the relationship and a better social interaction. [

38,

39]

In addition, the research also found deep traces in some respondents from a deceased partner who marked their lives, with an indelible memory that leads them to the extreme of not wanting to face a new partner for life and, therefore, depriving themselves of new experiences in sexuality.

As in other studies, [

21,

33] most of the stories are based on the heteronormative condition of the interviewees and, in this case, there is a homophobic approach that is anchored to formal education, the conservative formation of the families of origin and associated religious dogmas.

The research highlights the relationship between biopsychosocial, cultural and emotional aspects with changes in sexuality and quality of sexual life, which configure integral, loving and fulfilling relationships, which is consistent with the findings of Domínguez and Barbagallo, [

40] in which older people continued to value sexuality, the expression of desire and identity, with new meanings based on openness, exploration, curiosity, valued relationships and adaptations to this life cycle.

Alterations in identity or inappropriate sexual behaviors represented in other research, [

37] did not appear in this research, but rather are in line with studies that both the quality of life and sexual well-being are experienced differently according to sociodemographic, health and lifestyle conditions. [

41]

This study, like others, [

20,

42,

43,

44,

45,

46,

47] showed that older people are sexual beings who value the exercise of sexuality as something necessary and important at this stage of life; however, there is a society that views them as asexual beings and discriminates against them as a result of socio-normative standards, the existence of myths or beliefs, and the existence of stereotypes that make sexuality invisible in this life cycle.

Although the reasons for coital activity are the same in different age and gender groups, men in general have physical reasons and young adult women have emotional reasons. In older women, physical capacity and sexual satisfaction tends to decrease, which corroborates that sexuality is experienced differently in each life cycle and that there are biopsychosocial aspects that are at the basis of these differences. [

48]

Unlike other research, [

49,

50] there are persistent narratives that do not show a successful aging rooted in the retention of youth, added to a redefinition of self-image away from aesthetics and rooted in an “affirmative aging”, but there are feelings of loss in some cases, or of sexuality decadence in others, for reasons of abuse in childhood or adolescence, or abandonment of partners in the case of some women.

The research corroborates what other authors report on the dissatisfaction produced by various diseases in the quality of sexual life, [

11,

12,

13] where although the causes are diverse, in this study prevailed arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus type 2, prostate cancer and erectile dysfunction in men or breast dysfunction in women. There is also concordance with the evidence in older European men who present a higher prevalence of premature ejaculation associated with prostate problems, worse sexual function, deterioration of partner relationships and loss of quality of life. [

51]

As in other studies, a relationship was found between better sexuality and having a partner, physical capacity, healthy diet and good mental health (cognitive, memory and intelligence). [

11,

29]

The account of the interviewees corroborates the lack of attention to the sexuality needs of the elderly by the health professionals of the CESFAMs. This is in agreement with that demonstrated by Acevedo et al, [

52] who base the evasion of sexual health by physicians or health personnel in PHC; as well as the lack of preparation or training of these, [

20,

53,

54] to which are added negative attitudes to this type of attention that produce barriers to access to this type of interventions. [

11,

23,

55] deficit in the delivery of educational contents on the subject, [

11,

12,

13,

14,

23,

45] despite the effectiveness of some similar educational programs. [

56]

In accordance with the above, it is essential to redefine the sexual rights of the elderly in line with several authors, [

26,

52,

57,

58] who, among other things, prepare from public and assistance policies the elimination of sexual abuse in the elderly, since in the research some interviewees expressed stories of damage in the quality of sexual life throughout their lives, including in older adulthood.

Evidence shows that sexuality and sexual health in the elderly can be improved by fostering resilience, promoting good physical and mental health, and minimizing the ageism that is often self-inflicted by the elderly themselves, [

59] associated with smart cities that improve the quality of life, mobility and connectivity at the country level of this interest group, in tune with public policies of active and healthy aging. [

60]

5. Conclusions

Sexuality in the elderly is an emerging issue worldwide, which goes hand in hand with the population aging that many countries are currently experiencing, which is why it should be advocated to be considered as an essential human right based on biopsychosocial, cultural and emotional aspects of the elderly.

Countries should advance in technological innovations and in the training of health personnel to address the sexual health needs of this group of interest, which demands optimal care from a biopsychosocial and comprehensive perspective.

National and international evidence shows the growing and felt need to improve access and opportunity of sexuality care for the elderly at PHC and first level of care, which makes it pertinent to improve the implementation of public health policies oriented to it, as well as the preparation of health personnel at this level, with permanent and continuous undergraduate and postgraduate training.

The 10 dimensions found in the research show the importance of the contents that emerge when the subject is investigated, as ideas, experiences, feelings and deep emotions represented in the subdimensions emerge, which opens to the scientific community a wide range of possible future explorations related to sexuality in old age.

To conclude, postmodernity is a mirror that reflects dimensions and characteristics of a sexuality in process of change in the elderly in the social and community territory, which requires the management of strategies from a sociocultural, educational and health care perspective, necessary to improve the quality of sexual life in old age, in line with national and international recommendations.