1. Introduction

In Japan, 13,388 women were diagnosed with ovarian cancer in 2019, and 4,876 women died from the disease in 2020 [

1]. The Ovarian Cancer Treatment Guidelines [

2] recommend combination therapy with platinum and paclitaxel as the primary treatment for advanced and recurrent ovarian cancer. Approximately 70% of ovarian cancers are serous ovarian cancer [

3]. Further, 51% of serous ovarian cancers are diagnosed as clinically advanced stage III, the 5-year survival rate is 42%, and the histological type has a poor prognosis [

4]. The CA125 positivity rate is higher in serous ovarian cancer than in other histological types, making CA125 useful for diagnosis and treatment monitoring [

5].

Surgery plus postoperative chemotherapy (platinum) is the standard treatment for serous ovarian cancer [

2]. Recurrences within 6 months of platinum therapy completion are frequently platinum-resistant, whereas recurrences >6 months later are often platinum-sensitive [

2].

Therefore, platinum-based chemotherapy is indicated for patients with recurrent disease after ≥6 months or more [

2]. Olaparib is indicated after platinum therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer (PSR) in recurrent treatment [

2]. A meta-analysis of seven randomized controlled trials in PSR has revealed that olaparib extends patients’ overall survival [

6].

Platinum resistance tends to be acquired and recurrence occurs more quickly in PSR after platinum treatment completion [

7]. Olaparib has provided long-term disease control in some cases, even after platinum therapy [

8]. To date, a few reports from overseas focused on the characteristics of cases in which olaparib has achieved long-term disease control [

8,

9]. However, few reports presented Japanese patients. Moreover, only a few reports described the association between CA125 and the efficacy of olaparib treatment.

Therefore, this study aimed to determine clinical characteristics, including CA125, in PSR cases treated with olaparib.

2. Materials and Methods

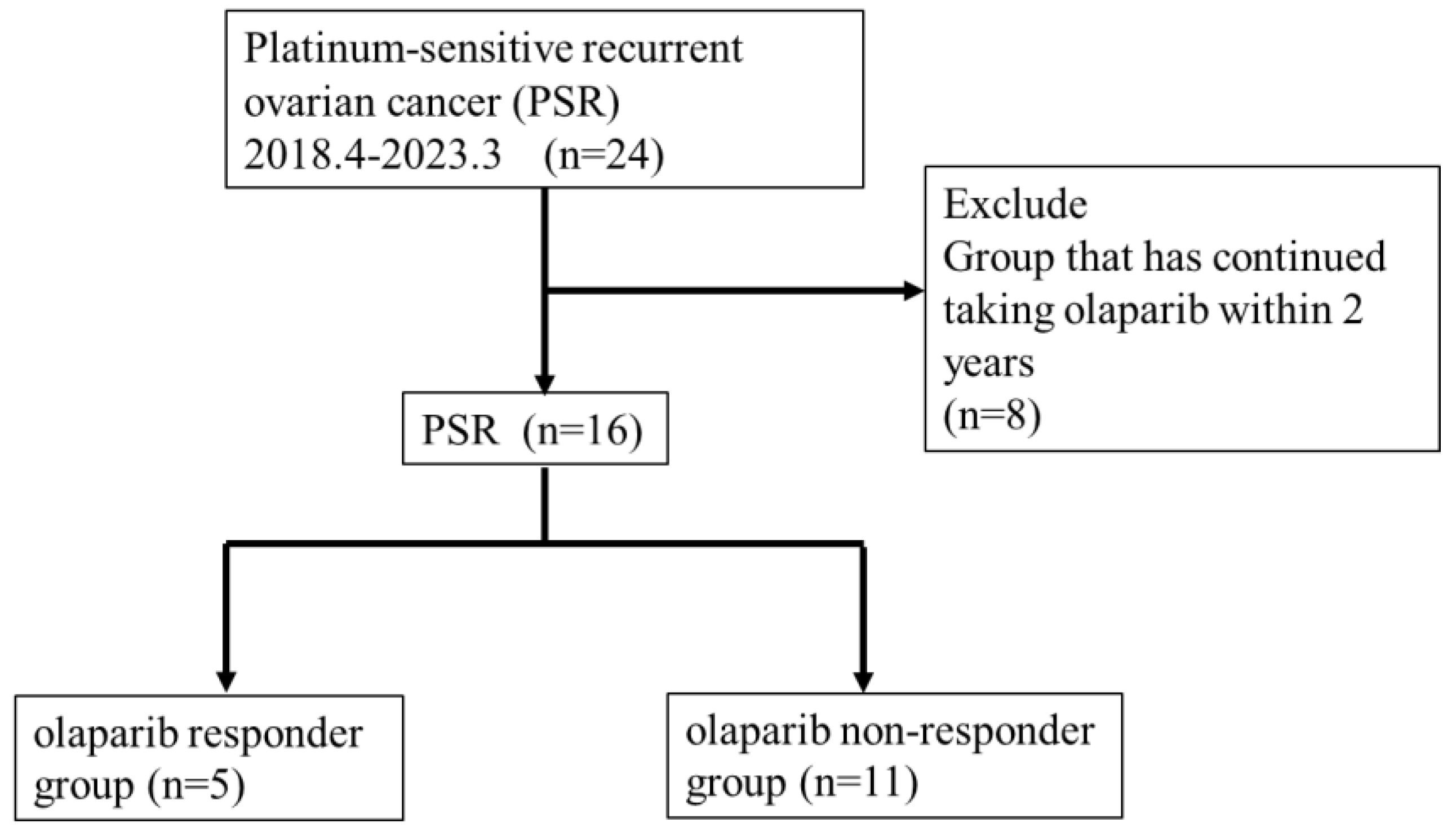

This study included 24 patients with recurrent ovarian cancer treated with olaparib for PSR at Toho University Sakura Medical Center from April 2018 to December 2023 (

Figure 1). We retrospectively reviewed medical records and analyzed the effect of clinicopathological factors to predict the treatment efficacy of olaparib.

We investigated the duration of olaparib treatment and the incidence of related adverse events in all 24 PSR cases. Prognosis analysis excluded 8 of the 24 cases because they had been treated for <2 years, and thus this study included 16 cases (

Figure 1). We categorized the 16 cases into 5 cases who continued taking medication for >2 years (responder group) and 11 cases who relapsed within 2 years (non-responder group) (

Figure 1). A

t-test was conducted to compare the following data between the responder and non-responder groups: 1) age, 2) number of platinum drug regimens, 3) platinum-free interval, 4) CA125 value during recurrence, 5) CA125 value before starting olaparib, 6) rate of decline in CA125, and 7) blood biochemistry test (C-reactive protein, neutrophil count, lymphocyte count, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) value, albumin, and calcium value).

Differences between groups were analyzed with t-tests for the categorical variables. A p-value of <0.05 indicated a significant difference. Overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) curves were generated using the Kaplan–Meier method and assessed using univariate analyses, with differences evaluated using the log-rank test. P-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. These statistical analyses were conducted using JMP pro17. The Ethics Committee of Toho University Sakura Hospital Medical Center approved this study (approval number S23060).

3. Results

3.1. Background of 24 Patients Who Were Treated with Olaparib

Table 1 shows patients’ backgrounds. Median age was 67 years (range: 46–84 years). Of the 24 cases, 21 had high-grade serous carcinoma, 2 had unclassified adenocarcinoma, and 1 had clear cell carcinoma. BRCA testing was conducted in 5 cases, with 2 positives (BRCA1: 1 case and BRCA2: 1 case) and 3 negatives. However, 19 cases were not tested. The clinical stage was ⅠC (1 case), ⅢA (5 cases), ⅢB (2 cases), ⅢC (13 cases), ⅣA (2 cases), and ⅣB (1 case). Median platinum-free interval was 9 months (range: 6–47 months). The median number of chemotherapy regimens before starting olaparib was 2 (range: 2–6). The median duration of olaparib treatment was 7 months (range: 1–55 months).

3.2. Adverse Events During Olaparib Treatment in 24 Cases—Observation Period 1–55 Months

Table 2 presents adverse events in 24 cases treated with olaparib. Adverse events of grade ≥3 were observed in 10 (41.7%) patients. The main side effects were nausea and fatigue in 10 (41.7%) patients and anemia in 15 (62.5%) patients, of which 8 (33.3%) were grade ≥3. No patients discontinued olaparib due to adverse events.

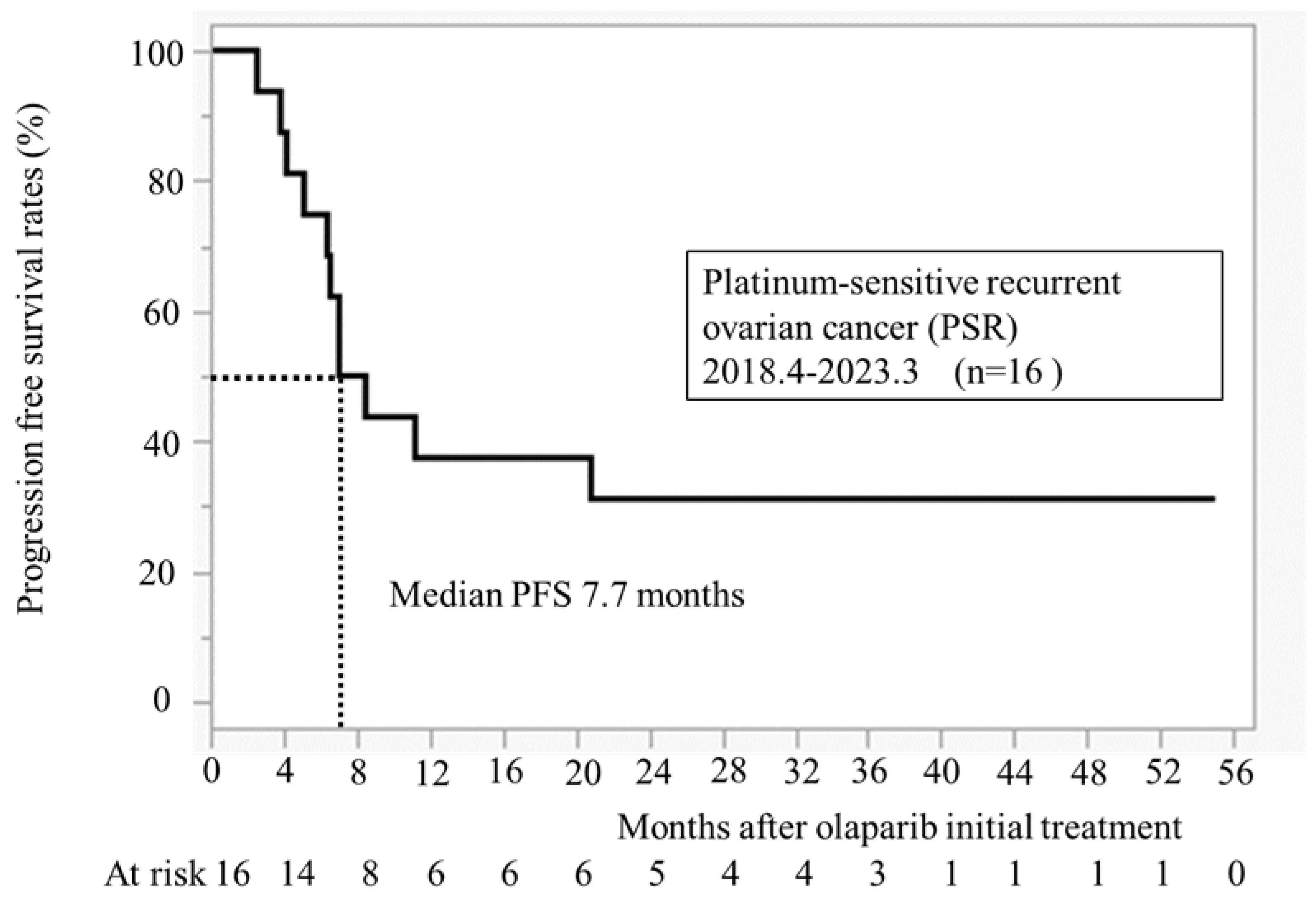

3.3. Progression Free Survival After Initiation of Olaparib Treatment (n = 16)

Figure 2 illustrates PFS for 16 cases at our hospital. The median PFS was 7.7 months. All recurrence cases occurred within 24 months, and no recurrence was observed in patients taking olaparib for >24 months.

3.4. Comparison of the Background Between Responder Group (n=5) and Non-Responder Group (n=11)

Clinicopathological characteristics are compared between the responder and non-responder groups (

Table 3). No statistically significant differences were found in the number of chemotherapy regimens, platinum-free interval, CA125 values during recurrence before chemotherapy, or the rate of decline in CA125 related to chemotherapy. The median age was significantly younger in the responder group than in the non-responder group (52 years old versus 69 years old,

P = 0.02). The median CA125 value was significantly lower in the responder group than in the non-responder group (14.2 U/ml versus 82.7 U/ml,

P = 0.02). Blood test values were compared between the responder and non-responder groups (

Table 4). C-reactive protein, neutrophils, lymphocytes, LDH, albumin, and calcium immediately before taking olaparib exhibited no differences between the two groups.

3.5. Outcome

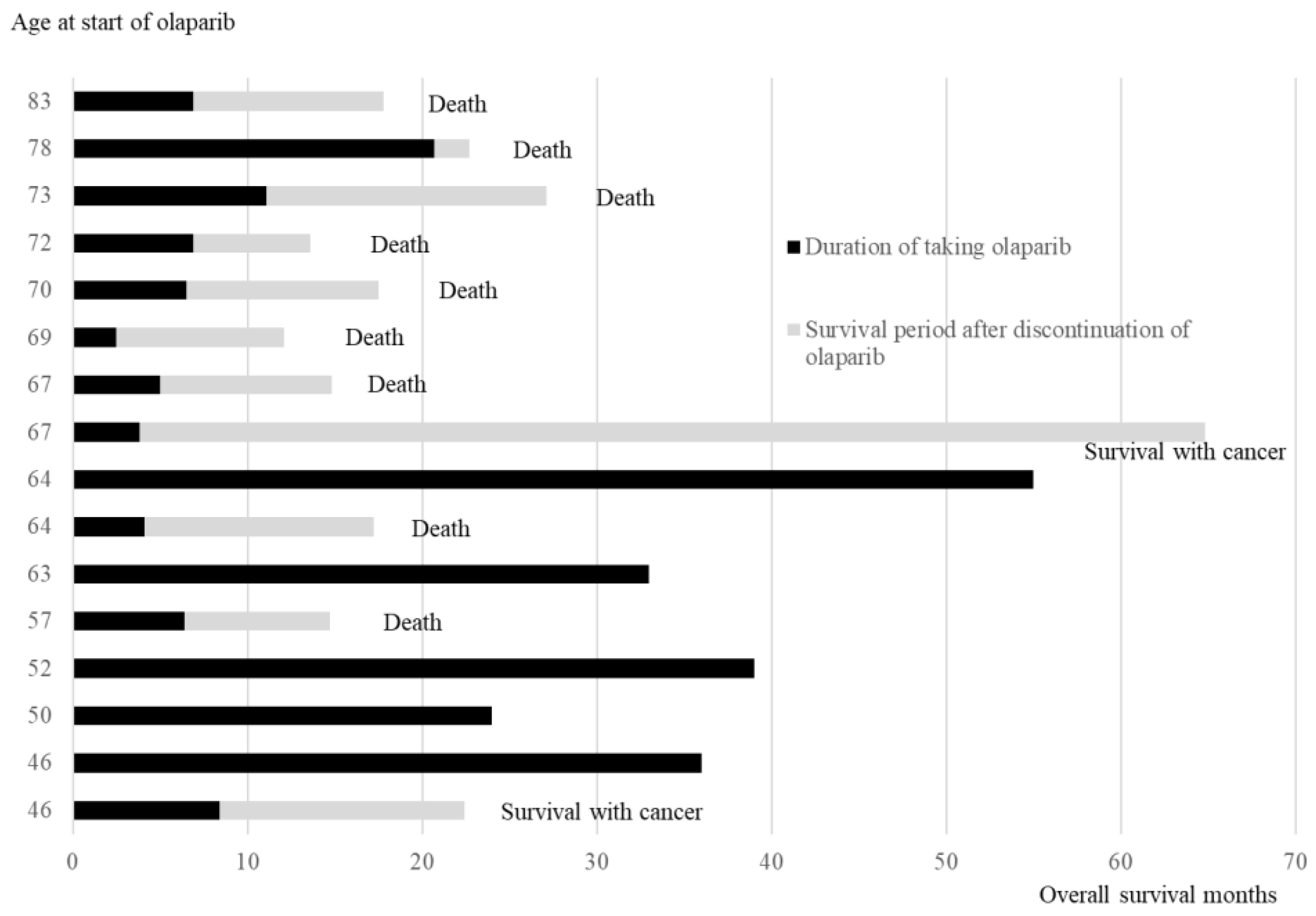

3.5.1. Age at the Time of Starting Olaparib, Duration of Olaparib Treatment, and Survival Time After Relapse and Discontinuation of Olaparib

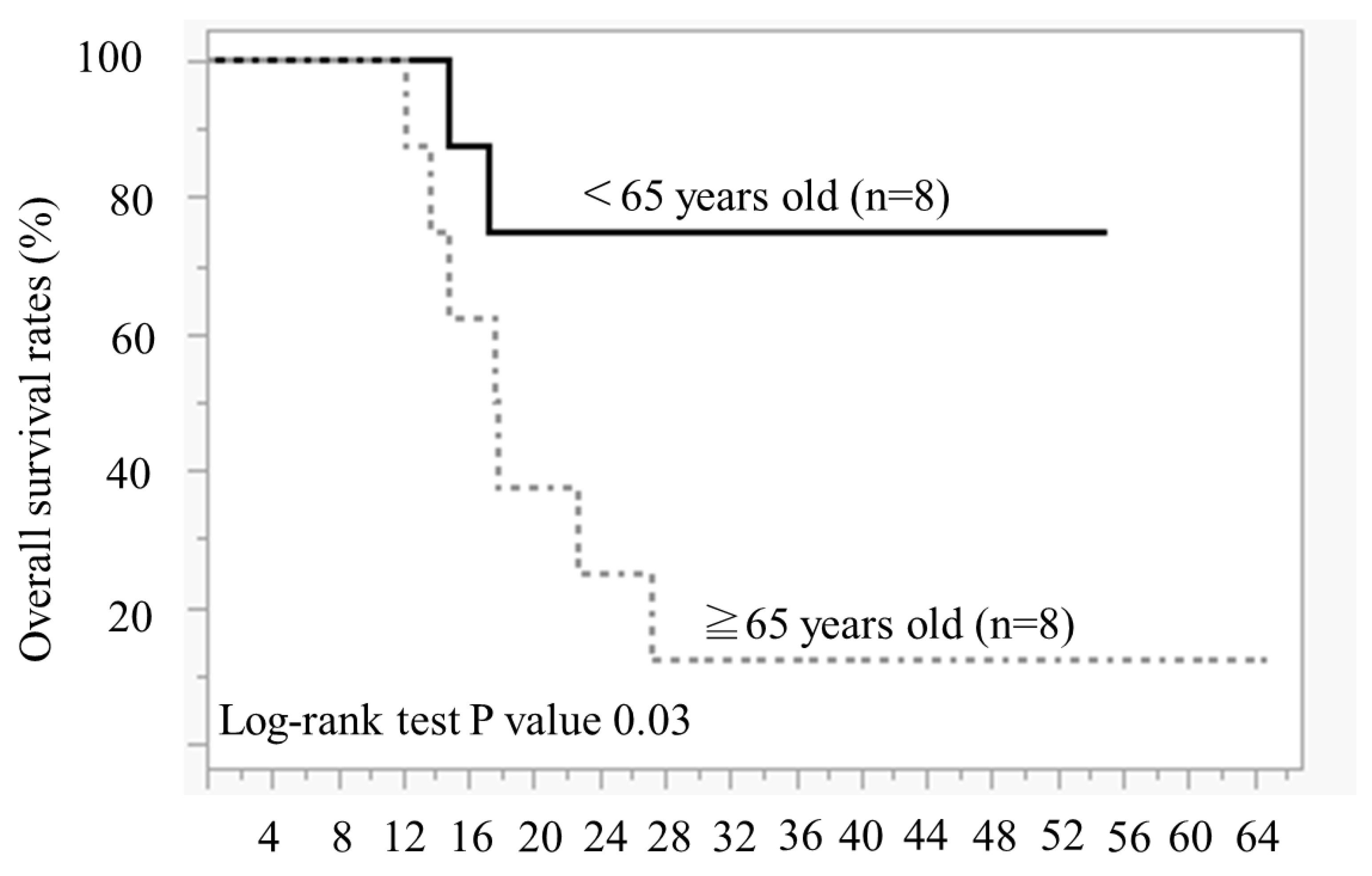

Figure 3 illustrates the duration of olaparib treatment and survival time after relapse and olaparib discontinuation, in order of age during olaparib initiation. In patients aged ≥65 years, 7 of 8 patients died of recurrence, and 1 patient survived with cancer. Conversely, in cases aged <65 years, 5 out of 8 cases have not experienced a recurrence and continued receiving olaparib, 1 case is alive and well with cancer, and 2 cases have died. The comparison of the OS between the two groups aged <65 years and ≥65 years revealed significantly better OS in those aged <65 years than in those aged ≥65 years (Log-rank test,

P = 0.02) (

Figure 4).

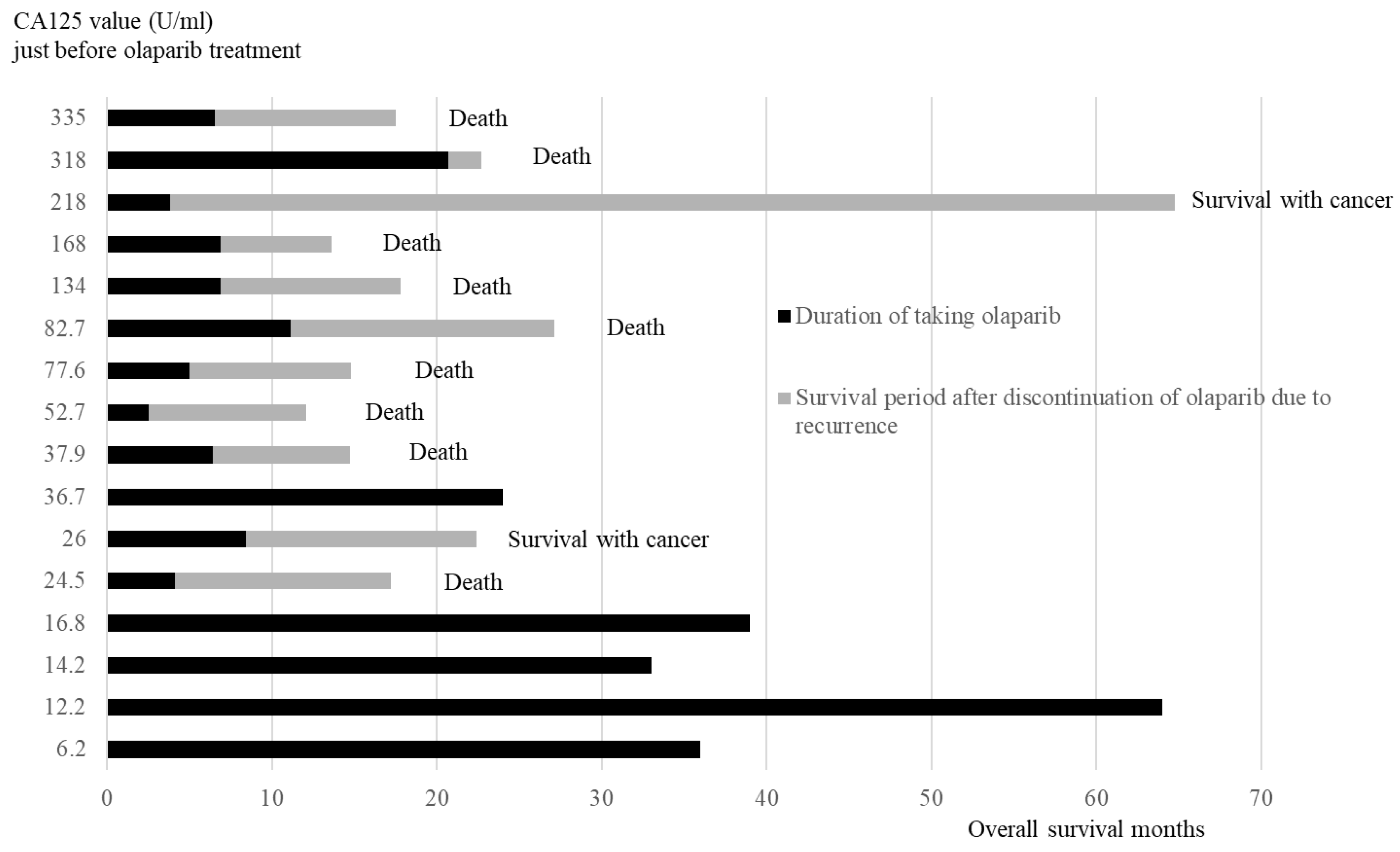

3.5.2. Duration of Olaparib Treatment and Overall Survival Months After Recurrence in Order of CA125 Values Just Before Olaparib Initial Treatment

The duration of taking olaparib and the survival period after discontinuing olaparib are presented in the order of CA125 value (

Figure 5). All four patients in the low CA125 value group (<20 U/ml) did not relapse and were continuing with olaparib. Of the 12 cases in the high CA125 value group (≥20 U/ml), 11 relapsed and discontinued olaparib, whereas 1 case continued olaparib.

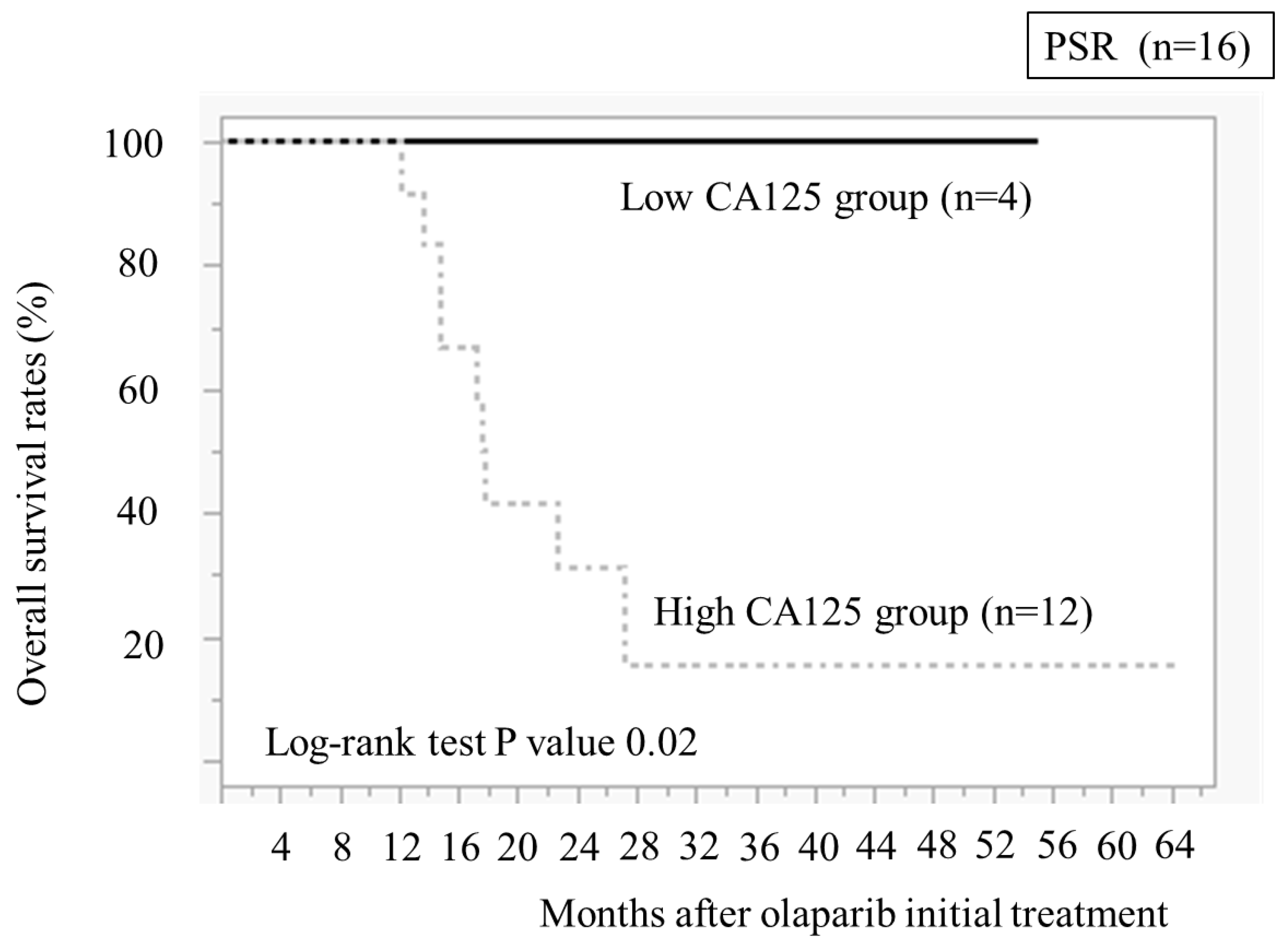

We compared the OS between the low and high CA125 value groups (

Figure 6). The low CA125 group demonstrated significantly better OS than the high CA125 group (

P = 0.02)

4. Discussion

This study analyzed 24 PSR cases treated with olaparib and confirmed the clinical characteristics of effective cases. The younger (<65 years old) and low CA125 groups demonstrated significantly better OS than the other groups.

The median age of participants in Study 19 vs. L-MOCA trial was 58 years (range: 21–89 years) vs. 54 years (range 50–61.5 years). All L-MOCA trial cases were aged <65 years, and the participants were younger than in Study 19. Regarding the age, the median PFS of maintenance therapy with olaparib in Study 19 vs L-MOCA trial was 8.4 vs. 16.1 months. L-MOCA trial revealed a longer PFS than Study 19 [

10]. Additionally, a retrospective study at our hospital revealed that the median ages of the non-responder and responder groups were 69 years (46–83) and 52 years (46–64), respectively, with a

p-value of 0.02, indicating a statistically significant difference. This study indicated that PFS with olaparib maintenance therapy for PSR is extended in younger patients. The PFS was significantly longer in the group aged <65 years than in those aged ≥65 years at our hospital, so we considered that patients aged <65 years could be treated with olaparib for a long period.

Regarding the cut-off value for CA125 in ovarian cancer, a study indicated that it should be set at 15–20 U/ml, the same as for postmenopausal women, since treatment is bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy [

11]. Our study revealed the CA125 value of 20 U/ml in four PSR cases immediately before taking olaparib, and all four cases had been recurrence-free for >2 years and continued taking olaparib. Additionally, OS was longer than in 11 cases with CA125 levels of ≥20 U/ml. These results indicate that CA125 of <20 U/ml in PSR immediately before taking olaparib after chemotherapy could be a guideline for patients who can take olaparib for >2 years.

Nausea occurred in 54% of patients and anemia in 76.4% of patients in the L-MOCA trial that targets Asians [

10]. All 24 cases at our hospital were Asian, with nausea occurring in 41.7% of cases and anemia in 62.5% of cases, and the frequency of adverse events was closer to that of the L-MOCA trial than Study 19. Therefore, as an adverse event of olaparib, nausea may more likely occur in Caucasians, and anemia is more likely to occur in Asians. The frequency of adverse events in this study was comparable to known adverse events in Asian patients.

5. Conclusions

The number of patients in the present study is too small to conclude. The younger group (<65 years old) and the low CA125 value group (<20 U/ml) in PSR may be treated with olaparib for a long period and suppress disease progression. Providing this information to patients with PSR may help in decision-making regarding performing maintenance therapy with olaparib.

6. Patents

This section is not mandatory but may be added if there are patents resulting from the work reported in this manuscript.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation: H.I., H.S.; methodology: H.I.,M.M., M.N., and H.S., validation: H.I., A.T.; and H.S., formal analysis: H.I.; investigation: H.I., M.M., and H.E. ; resources: H.I., M.M. ;data curation: H.I, M.M, H.E. and M.N.; writing—original draft preparation: H.I.;writing—review and editing: H.I.; H.S., visualisation: H.I., M.N.; supervision: A.T.;H.S., project administration: H,I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Toho University Sakura Medical Center (protocol code S23060 and 21st February 2024 of approval).

Informed Consent Statement

Research information was disclosed and the opportunity to opt out was guaranteed.

Data Availability Statement

Datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

Maruzen-Yushodo has provided English proofreading.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of this study; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of the data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- National Cancer Center Japan, Cancer Statistics, Ovary 2024.

- Tokunaga H, Mikami M, Nagase S, Kobayashi Y, Tabata T, Kaneuchi M, Satoh T, Hirashima Y, Matsumura N, Yokoyama Y, Kawana K, Kyo S, Aoki D, Katabuchi H. The 2020 Japan Society of Gynecologic Oncology guidelines for the treatment of ovarian cancer, fallopian tube cancer, and primary peritoneal cancer. J Gynecol Oncol. 2021 Mar;32(2):e49. [CrossRef]

- Momenimovahed Z, Tiznobaik A, Taheri S, Salehiniya H. Ovarian cancer in the world: epidemiology and risk factors. Int J Womens Health. 2019 Apr 30;11:287-299. [CrossRef]

- Torre LA, Trabert B, DeSantis CE, Miller KD, Samimi G, Runowicz CD, Gaudet MM, Jemal A, Siegel RL. Ovarian cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018 Jul;68(4):284-296. [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi Y, Shimada H, Yamasaki F, Yamashita T, Araki K, Horimoto K, Yajima S, Yashiro M, Yokoi K, Cho H, Ehira T, Nakahara K, Yasuda H, Isobe K, Hayashida T, Hatakeyama S, Akakura K, Aoki D, Nomura H, Tada Y, Yoshimatsu Y, Miyachi H, Takebayashi C, Hanamura I, Takahashi H. Clinical practice guidelines for molecular tumor marker, 2nd edition review part 2. Int J Clin Oncol. 2024 ;29(5):512-534. [CrossRef]

- Chen Q, Li X, Zhang Z, Wu T. Systematic Review of Olaparib in the Treatment of Recurrent Platinum Sensitive Ovarian Cancer. Front Oncol. 2022 Mar 1;12:858826. [CrossRef]

- Yang L, Xie HJ, Li YY, Wang X, Liu XX, Mai J. Molecular mechanisms of platinum-based chemotherapy resistance in ovarian cancer (Review). Oncol Rep. 2022 Apr;47(4):82. [CrossRef]

- Ledermann J, Harter P, Gourley C, Friedlander M, Vergote I, Rustin G, Scott C, Meier W, Shapira-Frommer R, Safra T, Matei D, Macpherson E, Watkins C, Carmichael J, Matulonis U. Olaparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012 Apr 12;366(15):1382-92. [CrossRef]

- Pujade-Lauraine E, Ledermann JA, Selle F, Gebski V, Penson RT, Oza AM, Korach J, Huzarski T, Poveda A, Pignata S, Friedlander M, Colombo N, Harter P, Fujiwara K, Ray-Coquard I, Banerjee S, Liu J, Lowe ES, Bloomfield R, Pautier P; SOLO2/ENGOT-Ov21 investigators. Olaparib tablets as maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive, relapsed ovarian cancer and a BRCA1/2 mutation (SOLO2/ENGOT-Ov21): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017 Sep;18(9):1274-1284.

- Gao Q, Zhu J, Zhao W, Huang Y, An R, Zheng H, Qu P, Wang L, Zhou Q, Wang D, Lou G, Wang J, Wang K, Low J, Kong B, Rozita AM, Sen LC, Yin R, Xie X, Liu J, Sun W, Su J, Zhang C, Zang R, Ma D. Olaparib Maintenance Monotherapy in Asian Patients with Platinum-Sensitive Relapsed Ovarian Cancer: Phase III Trial (L-MOCA). Clin Cancer Res. 2022 Jun 1;28(11):2278-2285. [CrossRef]

- Rustin GJ. What surveillance plan should be advised for patients in remission after completion of first-line therapy for advanced ovarian cancer? Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010 Oct;20(11 Suppl 2):S27-8.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).