1. Introduction

Charcot neuroarthropathy (CN) or osteo-neuroarthropathy has been well described. This condition is known to be a sequela of poor diabetic control. The incidence rates are estimated to be 3-8 per 1000 diabetic population per year. The treatment options may include conservative measures, surgical interventions, and even amputation, if necessary. The complexity of this condition and the known fact of a high risk of infection and treatment failure have placed a financial burden on the healthcare system worldwide.

The pathology that causes CN has been based upon “neuro-traumatic theory” and “neuro-inflammatory theory” [

1]. Despite these theories, the true incidence and prevalence of CN remain unclear. In Denmark, based on the Danish National Patient Registry, the prevalence was reported as 0.56% among diabetic patients, with an incidence rate of 7.4 per 10,000 [

2]. Several other studies have reported varying prevalence rates. For instance, a study from Southeast Ireland found a prevalence of 0.26% among individuals with diabetes, while a study in the East Midlands of England reported a lower prevalence of 0.04% [

3]. There are many more cases that remain undiagnosed or unreported.

Various classifications or description of stages have been previously established to identify and group the condition. Eichenholtz orchestrated a temporal-based approach with X-rays and clinical appearance to divide Charcot into different neuropathic stages. Stage 1 or the fragmentation stage is evidenced by disorganized joints with bony debris, fragmentation, and periarticular fractures in the foot or ankle that may result in laxity or joint subluxation. In Stage 2, also described as the coalescence phase, the periarticular fracture fragments are being resorbed, and new bone formation can be seen in radiographs. Stage 3 is described as a stage of reconstruction or resolution, in which the bone becomes more evident and stable with or without unresolved deformity. In 1990, Shibata modified the Eichenholtz classification, with the addition of prodromal or Stage 0, where the clinical features are warmth, swelling, and redness, with subtle radiographic changes which may only be seen via MRI.

Several other classifications on CN, as described by Brodsky [

4], Sanders and Frykberg [

5,

6] and Schon [

6,

7], were all general classification involving the ankle and foot. There is no current classification dedicated to elaborating the possible deformity patterns or the description of bone loss involving the ankle CN. This is probably due to the fact that the condition has a low incidence of only 3-8 per 1000 diabetic population per year [

8,

9]. Furthermore, there may be a lack of knowledge in identifying these conditions early, as many may have not encountered it or have little experience diagnosing ankle Charcot.

We believe it is useful to have a standardized framework or classification, as it facilitates the effective communication of relevant information between medical professionals. This would simplify the understanding of a patient’s stage, enabling proactive documentation and a strategic plan of care for patients. The purpose of this new classification is to enhance the categorization of ankle CN that could contribute to a better understanding and management of the condition as a whole, operatively or non-operatively.

2. Materials and Methods

A retrospective review of patients who had been diagnosed with CN was performed. This was a collective pool of patients under the care of the Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust (MFT) over a period of 10 years. Most patients had a deformity, which was apparent clinically, that altered the hindfoot alignment, resulting in gait abnormalities. The clinical findings during follow-ups, serial radiographs, weight-bearing ankle X-rays of the involved ankle, and condition-related outcomes of these patients were extracted from the clinical case records and our foot and ankle Charcot database.

The patients with only a complete ankle weight-bearing X-ray and clinical details were included. The follow-up time frame was not a factor considered in this study; thus, no minimum or maximum follow-up timeline was required.

Seventy-five ankles were identified; there were 71 patients, of whom 4 had bilateral ankle deformity. In this cohort, there were 48 male and 23 female patients. All of the identified patients had followed-up with a senior foot and ankle surgeon at the MFT.

The parameters were reviewed using weight-bearing anteroposterior (AP) and lateral X-rays, assessing the coronal and sagittal plane deformity of the ankle. The evident bone loss involving the tibia, talus and calcaneum resulting from the longstanding or present deformity was assessed as part of the newly proposed classification system. Along with this, the Charcot stages of each ankle were evaluated by a senior foot and ankle surgeon based at our center. The stages of Charcot were documented based on the modified Eichenholtz system; presence of acute bony fragmentation or destruction (Stage 1), bony resorption or new bone formation (Stage 2), and remodeled bone with potential deformities (Stage 3).

We name this classification as, M-CAN; Manchester Charcot Ankle Neuroarthropathy. This proposed new classification demonstrates the ability to classify the ankle Charcot based on X-rays. Based on the classification, “A”, “B”, and “E” were the three main criteria reviewed, which enabled us to classify all the involved ankles, without any form of specialized imaging involving CT or MRI. Although it is possible to additionally sub-classify the degree of bone loss, at the point of classifying the deformity, there is no need to quantify this, as it would not offer any additional diagnostic information. However, this can be conducted as a preoperative evaluation for surgical planning.

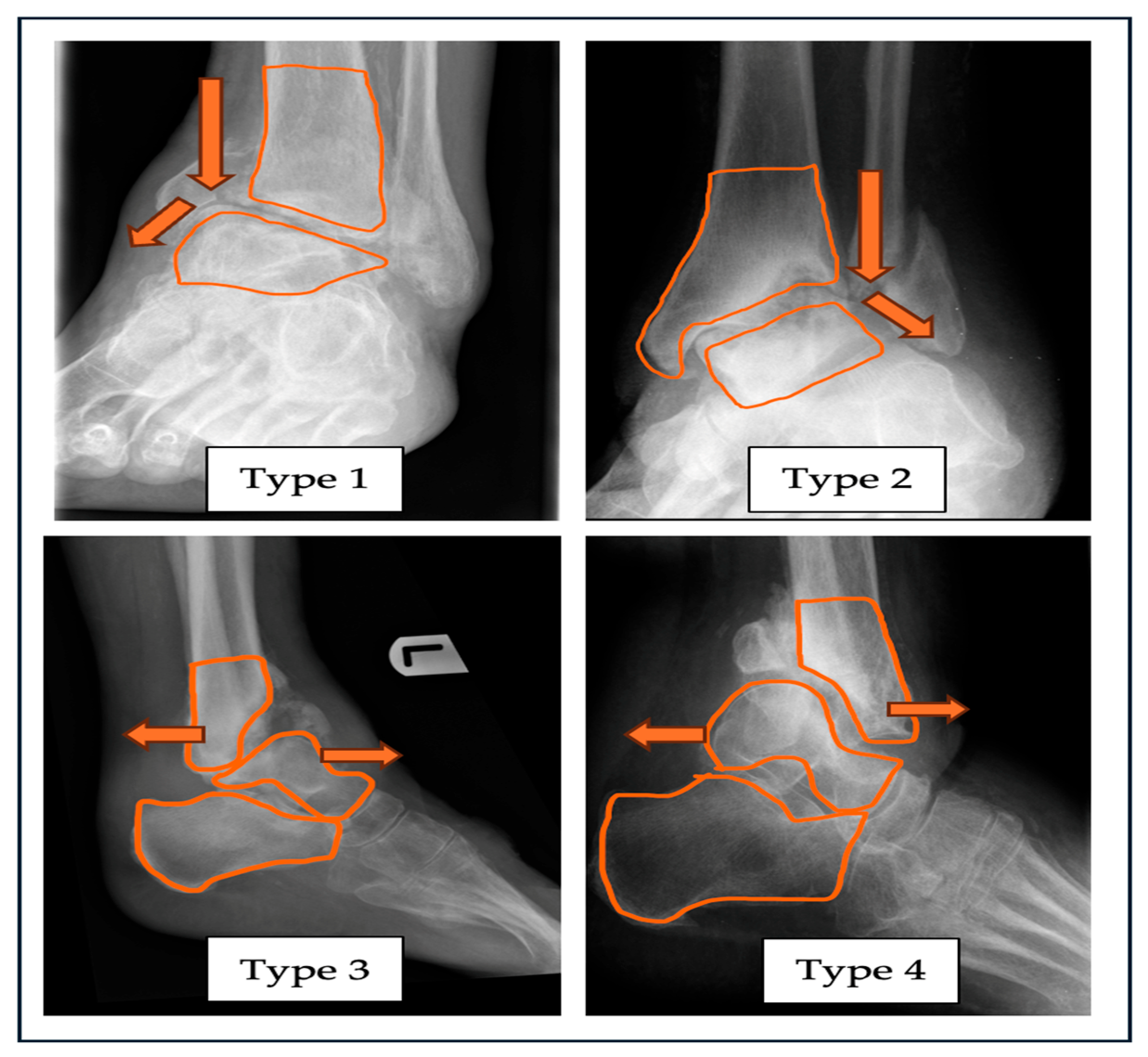

In the abbreviation, “A” stands for alignment of the ankle joint in the coronal varus (Type 1) or valgus (Type 2) deformity. Sagittal plane deformity can be classified with the plane of either anterior (Type 3) or posterior (Type 4) angulation of the involved joint. If the diagnosis of ankle Charcot is confirmed, in the absence of any alignment deformity, it can be classified as Type N (neutral). A combined deformity with subluxation and/or dislocation, which refers to a multiplanar deformity, can be classified as Type 5.

Figure 1.

Radiograph with superimposed illustrations of four different types of alignment deformities related to ankle CN: Type 1—varus, Type 2—valgus, Type 3—anterior angulation, Type 4—posterior angulation of the ankle joint. .

Figure 1.

Radiograph with superimposed illustrations of four different types of alignment deformities related to ankle CN: Type 1—varus, Type 2—valgus, Type 3—anterior angulation, Type 4—posterior angulation of the ankle joint. .

The coronal plane deformity was measured based on the midline tibiotalar angle (MTTA), the anatomical axis of the tibia, and the superior articular surface of the talus. Angles more than 90 degrees are defined as valgus, and those less than 90 degrees are defined as varus [

10]. The sagittal planes’ measurement was based on the Lateral Talar Station (LTS), which defines the sagittal position of the talus in relation to the anatomical tibial axis [

11]. In a neutral position, the center of the talus lies within -0.81mm to +3.15mm of the axis of the tibia.

Table 1.

M-CAN: Manchester Charcot Ankle Neuroarthropathy Classification System; main 3 components “A”,”B” and “E” which describes each of its variation.

Table 1.

M-CAN: Manchester Charcot Ankle Neuroarthropathy Classification System; main 3 components “A”,”B” and “E” which describes each of its variation.

| “A”Alignment |

Varus

Type 1

|

Valgus

Type 2

|

Anterior

Type 3

|

Posterior

Type 4

|

Combined

Type 5

|

Neutral

Type N

|

| |

| “B”Bone loss |

Tibia

Subtype a

|

Talus

Subtype b

|

Calcaneum

Subtype c

|

Combined

Subtype d

|

Can further quantify the bone loss based on CT scan for preoperative planning by the treating surgeon.

*Leave it unlabeled if there is no bone loss present.

|

| |

“E”Eichenholtz stage with

Shibata modification |

Stage 0 Stage 1 Stage 2 Stage 3

Prodromal Destruction Coalescence Consolidation

|

Next, from the proposed classification,

“B” represents bone stock, which denotes the presence of bone loss, with subtypes

a, b, c and

d. These subtypes refer to the tibia, talus, calcaneum, and combined form of bone loss, respectively. All patients in this review were classified based on plain weight-bearing ankle X-rays.

Figure 2 shows the sagittal view of an ankle, with osteodestruction involving the distal tibia and calcaneum, with a severely fragmented talus.

We have incorporated the modified Eichenholtz classification, “E”, for Eichenholtz, in our classification system as well. The ankle Charcot can be Stage 0-3, at the point of examination of the involved ankle. This can be a guide to the timing and choice of treatment. Stages 1-3 can be observed with plain X-rays, and additional MRI imaging may be required for Stage 0, if necessary.

The remaining components of the classification, “C”, “D”, and “F”, are included as supplementary elements in this system, which may provide a more comprehensive information. This additional parameters which evaluates the presence of an ulcer or an infection, glycated hemoglobin levels and pedal perfusion status would help determine the modality of treatment best suited for the patient. Furthermore, this would be an aid to predict the outcomes following the choice of either conservative or operative form of intervention.

The next component, “C”, for cutaneous, refers to the cutaneous or skin condition at the time the patient is seen. The simplest way of describing this is as ulcerated or non-ulcerated skin of the involved ankle. Further details, which can be included in this category, would be the presence or not of infection, established with microbiological studies.

Table 2.

M-CAN: Manchester Charcot Ankle Neuroarthropathy Classification System; supplementary 3 additional components “C”, “D” and “F” which can complete this classification more comprehensively.

Table 2.

M-CAN: Manchester Charcot Ankle Neuroarthropathy Classification System; supplementary 3 additional components “C”, “D” and “F” which can complete this classification more comprehensively.

| |

“C” Cutanous

condition |

|

Ulcerated |

Non-ulcerated |

|

| |

Infected |

|

|

|

| |

Non-Infected |

|

|

|

| * mark (/) on the relevant findings |

“D” Diabetic

control |

HbA1c < 53 mmmol/L (<7.0%) |

HbA1c > 53mmmol/L (>7.0%) |

| NICE guidelines UK 2015 |

| “F” Foot perfusion (Pulse/Doppler) |

Monophasic Diaphasic Triphasic

(PM) (PD) (PT)

|

| *Toe pressure can be used alternatively. |

The next level is labelled as “D”, for diabetic control. Often, when a diabetic patient is treated for Charcot, the underlying disease control is not addressed. However, the success of a treatment depends on the disease control itself. The easiest monitoring tool is that of the levels of glycated hemoglobin: hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c). This categorization would be based on the HbA1c level being either less or greater than 53mmmol/L (7.0%). If the patient falls under the accepted value, it is classified as green, and more than the accepted value is labelled as red. This is an important parameter, which needs to be optimized if a patient will have surgery. This may require multidisciplinary team involvement to help address and achieve the acceptable value.

The component “F”, for foot perfusion, refers to perfusion of the foot at the point of the examination of the foot. This can be performed at an outpatient set-up, with hand-held Doppler scans. In this classification system, PM refers to pulse-monophasic, PD refers to pulse-diphasic, and PT refers to pulse-triphasic.

Collectively, the proposed new classification system for ankle CN can be easily remembered as simple pneumonic, ABCDEF. The first three elements “A”, “B” and “E” are the key parameters to be evaluated on plain X-rays, by identifying the ankle alignment deformity along with associated bone loss and the Charcot stage based on modified Eichenholtz classification. The way to describe this classsifcation with the main three components would be “A” + “B” + “E”= “ABE”. This is one way to describe the classification solely based on the available information on “A”, “B” and “E”.

The remaining supplemental elements “C”, “D” and “F” could be an aiding instrument in treatment related outcomes. With the additional available information on “C”, “D” and “F”, we can incorporate it with the preexisting elements and describe it as “ABE” + “C-D-F” collectively.

For an example; Type 1-d Stage 3, Ulcerated/Infected-Green-PM, which relates to a finding of a varus ankle with combined bone loss, presence of an ulcer, having a good glycated hemoglobin levels which is less then 53 mmol/L and pedal pulses were monophasic on doppler studies.

We also conducted an intra-observer reliability amongst five independent raters; three foot and ankle surgeons and two fellow trainees in foot and ankle surgery. This was done over a period of three months at two weekly interval, therefore a total of six time- point of X-ray review. Inter-observer reliability was evaluated amongst 20 independent raters; three foot and ankle surgeons and 17 general orthopedic and trauma surgeons. This was done in a single setting during a regular monthly journal review meet. This reliability was to evaluate the ability of the raters to identify the plane of the ankle deformity along with any possible bone loss, based on plain weight-bearing X-rays. The raters were briefed in detailed on the newly proposed classification system along with X-ray examples to describe each type of ankle alignment deformities “A” and each subtypes of associated bone loss “B”. The raters were then subjected to different sets of X-rays to identify the alignment deformities and the associated bone loss only, not the Eichenholtz stages of CN.

3. Results

Following a detailed review of the ankle X-rays in the anteroposterior (AP), lateral, and oblique views, we classified all 71 patients, with 75 feet in total. There were 44 left-sided ankle deformities and 31 right-sided deformities.

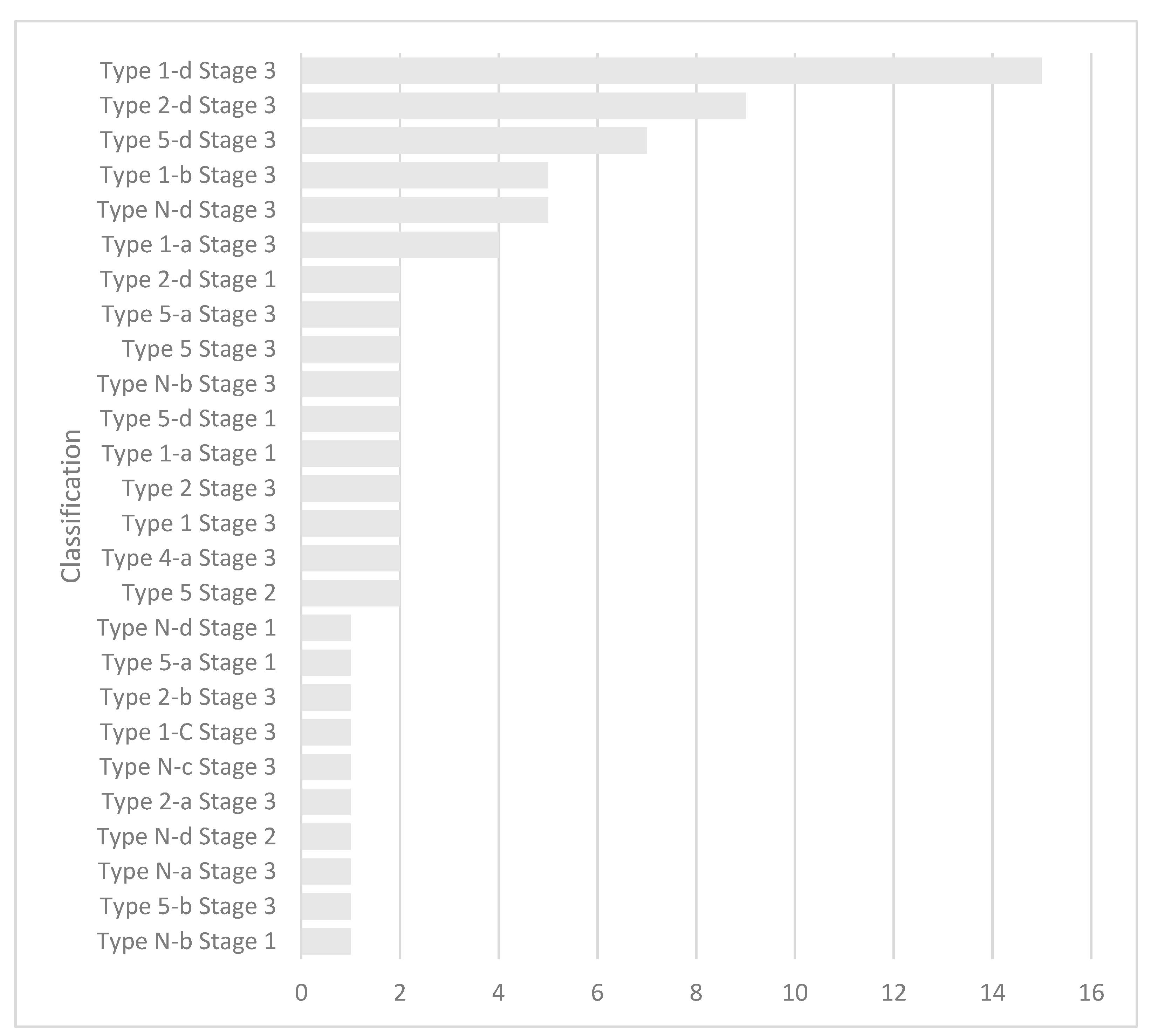

A total of 15 patients from the entire cohort were classified under Type 1-d Stage 3. This included ankle varus deformity, with a combined form of bone loss, which may be distal tibia–talus or talus–calcaneum. Stage 3, as mentioned earlier refers, to the consolidation stage of the Charcot based upon the modified Eichenholtz classification.

Upon further analysis, Type 2-d, Stage 3 represented the second largest group in the distribution, comprising nine ankles. This is valgus ankle deformity, with a combined form of bone loss, in the consolidative phase of Charcot. The remaining patients were distributed across several other groups, as shown in

Chart 1.

In this review, we were able to identify the portions of bone loss involving the ankle and its adjacent joint. Both the distal tibia and talus had almost similar numbers in terms of the identified osteodestruction. The osteodestruction may be isolated to the distal tibia or talus or may involve the calcaneus. The are also combined forms of osteodestruction, which involve distal tibia–talus articulation, talo-calcaneal articulation, and the entire hindfoot. The aforementioned were the most obvious forms observed. Other forms included the talo-navicular, anterior calcaneal process, posterior calcaneal tuberosity, and midfoot osteodestruction.

In our pool of patients, all of those who had presented to or were referred to our center were in Stages 1 to 3 of Eichenholtz. The majority were in Stage 3, followed by Stage 1 and Stage 2 accordingly. This allowed us to stratify and classify them based on the weight-bearing ankle X-rays. There was no need for MRI, as it is mostly used to identify Stage 0 of Eichenholtz.

The main defining parameters,

“A” and

“B” was subsequently evaluated with 20 independent raters for inter-observer reliability: three foot and ankle surgeons and 17 general orthopedic and trauma surgeons. Intra-observer reliability was conducted amongst five independent raters: three foot and ankle surgeons and two fellow trainees in foot and ankle surgery. The Fleiss Kappa (κ) test was performed to analyze the reliability for both groups using IBM SPSS Version 39. The inter-observer reliability yielded a Kappa value of 0.948, indicating almost perfect agreement among observers. Similarly, the Kappa value for intra-observer agreement was 0.947. The agreement levels remained consistent across all the evaluated X-rays, evaluating the ankle alignment deformity and associated bone loss. The modified Eichenholtz staging was not tested as it has some inconsistency on how different observers may apply the classification which results with a significant variability [

12].

4. Discussion

Chronic diabetic patients are vulnerable to progress and develop CN in their fifth or sixth decade of life. Most are diabetic for at least 10 years before the onset of CN [

13]. Both the T1DM and T2DM groups of patients are at risk of fractures. The bending resistance and trabecular stability and stiffness are significantly reduced. Microarchitectural analysis reveals increased cortical porosity with reduced cross-sectional bone area and a low trabecular bone score (TBS) [

14]. The reduced bone density in diabetic patients with CN increases their susceptibility to developing the described deformities, depending on the nature of the force or trauma affecting the involved ankle.

The review of

“A”, alignment, was performed to provide a better understanding of how and why the described deformities had occurred. The lateral ankle ligament complex is known to be the weakest link in terms of providing stability. In the most trivial injuries, the anterior talo-fibular ligament (ATFL) fails, which eventually leads to ankle instability [

15]. In the case of CN, due to the ongoing pathology of repeated inflammation surrounding the ankle, the integrity of the lateral ligament complex is often questionable. This can eventually fail to be stable and lead to varus angulation and further associated osteodestruction. This fact supports our findings, which revealed varus ankle angular deformity as the most common in ankle CN. It is an advantage to understand the plane of deformity, as this helps to decide on the best surgical plane of approach in the presence of a rigid form of deformity with contracted soft tissues.

Bone loss

“B” or osteodestruction involving the Charcot ankle, can be best explained via a 3D-CT bone morphometrical analysis, where the medial distal tibia has a more porous nature than the lateral distal tibia [

16]. The reduced density in the medial distal tibia increases the likelihood of a break in the medial wall of the ankle fork, which progresses to ankle varus deformity. This varus deformity may develop as a result of significant bone loss or resorption of the talus due to prolonged unprotected axial loading.

Physiological hindfoot alignment is a known parameter of 0 to 5 degrees valgus [

17]. This is in the normal anatomy, where the ankle works with axial loading. In the case of a CN, this normal hindfoot valgus could be detrimental in the long term. With the reduced bone mineral density in diabetic patients with CN, they are predisposed to fragility fractures [

14,

18]. Assuming the lateral ankle ligaments are intact, the weakened bone over the medial ankle with the constant normal valgus loading of the hindfoot would eventually lead to insufficiency or a fragility fracture of the medial distal tibia or the medial malleolus. With the fracture and continual axial loading, the ankle would follow the anatomical hindfoot valgus alignment, which would progress into a valgus deformation of the joint. This would possibly explain our observation of the valgus ankle deformity in CN, as the second most common pattern.

Variable investigative methods have been described to diagnose CN. Plain X-rays are appropriately adequate to visualize the plane of deformity and describe bone loss. The readily available access to X-rays allows for early identification of the described deformities and bone loss by general healthcare practitioners. MRI scans are pivotal in differentiating acute CN from osteomyelitis, which may dictate the choice of temporary or definitive stabilization [

13,

19]. CT scans can be helpful in the later consolidated stages of the disease and even to quantify the extent of bone loss for pre-operative planning and treatment staging [

19]. We propose the primary treating surgeon to utilize the modalities of CT or MRI as per necessasity.

The cutaneous condition

“C” is the clinical appearance that may be present in the form of an ulceration, which may or may not be infected. Understanding the cutaneous status is advantageous, as it helps in the decision making for the best modality of treatment for a patient. If it is ulcerated but uninfected, the patient may be treated with an offloading cast, which would allow the ulcer to heal, where subsequent bony corrections can be offered. In a case of infected Charcot, the treatment options may vary from intravenous antibiotics, possible serial debridement, and staged reconstruction or even amputation. Nilsen et al. reported an incidence of 64.9% of diabetic foot ulcerations in his study involving Charcot patients. In his study, a large number of Charcot patients with infected ulcers underwent lower extremity amputations, at 16.9% [

20].

Incorporating

“D”, diabetic control, via the glycated hemoglobin levels (HbA1c) in our classification serves as a reminder to assess the current diabetic control in the patient and to reevaluate it after implementing appropriate measures to improve it. Achieving good glycemic control is critically important to prevent the progression of diabetic neuropathy and, consequently, CN. The NICE guideline recommends an HbA1c target of 48 mmol/mol (6.5%) [

21]. Those patients with poorer control are predisposed for ulcerations with or without infection. Furthermore, poor glycemic control may hinder or worsen a surgical wound, if a surgical method of stabilization was the choice. A study on wound-healing potential in relation to HbA1c control suggested that a range between 7.0% and 8.0% would potentiate good wound healing with reduced risks of mortality in diabetic foot ulcers [

22].

In our review, we included the modified Eichenholtz

“E” stages to aid in decision making for the best treatment modality. Patients in stage 0 of Eichenholtz would rarely have any form of deformity at initial presentation. This group of patients would benefit from total contact casting until remission is achieved. Stage 1 patients would have a much longer period of remission and would be exposed to a higher chance of developing new deformities that require surgery [

23]. When they are further delayed in diagnosing the condition, or they present in the later stages of Charcot, the treatment modalities would differ and may be more costly and time consuming.

The circulatory status of a foot,

“F”, or foot perfusion, is an important factor that should be examined. Muller et al. elaborated that the existence of peripheral arterial disease is a direct contributor to delayed or disturbed wound healing in foot and ankle surgery. Their study recommends that patients undergoing any form of foot and ankle surgery should be evaluated thoroughly pre-operatively, including obtaining the ankle–brachial pressure index beforehand [

24]. About 40% of patients with CN are likely to have peripheral arterial disease; however, the rate was significantly lower in patients with diabetic foot ulcers. The chance of developing ischemia in patients with CN is lower than that in patients with diabetic foot problems or ulcers [

25]. However, it is beneficial to know the arterial status of these patients, as most severe deformities require surgical stabilization; thus, the risks of wound complications can be well explained and anticipated.

One of the main advantages of this classification is to enable an ankle Charcot to be classified in various presenting forms by means of plain weight-bearing X-rays. The X-ray modality is readily available for most healthcare practitioners, and it is the most widely used imaging in the diagnosis and further follow-up of such cases. This would be helpful for the early recognition of the condition, and the patient can be referred to a foot and ankle surgeon or trained personnel to provide the appropriate care. Furthermore, the receiving surgeon or trained personnel can perceive the pattern of deformity based on the described classification. This provides insight into the mechanics of the presenting deformity. Additionally, parameters such as the cutaneous condition, glycated hemoglobin levels, and foot perfusion status offer a comprehensive overview that can aid in determining the appropriate treatment modality.

Recent studies reveal that the lifetime prevalence of CN is increasing, from 0.1%-10% to a staggering 29% to 35% [

26]. The rate of misdiagnosing CN can be as high as 79% to 95%, with delays in treatment averaging about 29 weeks [

27,

28]. We hope that this classification system can be utilized as an aid when a practitioner observes a pattern of deformity based on our classification; it provides them with an indication to consider or diagnose it as ankle CN. This would improve the early detection rates that would be helpful in the prevention and management of the deformity’s progression.

We accept that there are some limitations in our review. We have not discussed in detail the methods of management for each type of deformity described. There is a need for a more detailed elaboration pertaining to the management of each type of deformity, which we plan to address in our next study or review. We describe a classification that could help in communicating the extent of the disease. This could help the receiving or treating surgeon to understand the pattern of deformity.

In conclusion, developing a new ankle CN classification would provide a guide in managing ankle CN. Understanding the patterns of deformity would be helpful to draft a treatment plan, whether conservatively or surgically. Such patterns highlight the deforming forces that need to be addressed, which could help prevent further worsening of the deformity and skin breakdown. Identifying the osseous loss would help plan the approach to surgery and the type of fixation required to provide a stable construct.