1. Introduction

Among topography-based technologies, rasterstereography has garnered particular attention from the research community. Although radiation-free systems are unable to directly assess the internal shape of the spine due to their reliance on evaluating the dorsal surface, they are considered a viable alternative to traditional radiographic imaging [

1,

2]. Rasterstereography typically provides an approximate 3D reconstruction of the spine, with its primary advantages being its cost-effectiveness and rapid execution, all without exposing the patient to ionizing radiation. As a result, rasterstereography has been widely adopted as a screening tool for the early detection of spinal deformities, particularly scoliosis [

3,

4]. Over the past decades, various instruments have been developed to apply the principles of rasterstereography, with the first being introduced by Drerup and Hierholzer in the 1980s [

5].

Monaro and colleagues addressed excellent intra-day and inter-day reliability in almost all analyzed parameters by using the Spine3D non-invasive three-dimensional optoelectronic detection system suggesting it as a reliable tool capable of discriminating different positions of the spine. They recommended it as an easy and fast way to analyze the surface shape of the spine for follow-up in clinical settings, also because results in using Spine3D methodology are similar to those found by studies with stereophotogrammetric systems [

6] allowing to consider this methodology able to measure such parameters. In line with these findings, we adopted the Spine3D system to test the postural changes induced by manual therapies, specifically Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment (OMT) and Gentle Touch Intervention (GTI).

Manual therapies, especially those targeting musculoskeletal structures, have been associated with both short-term and long-term modifications in posture and spinal alignment. While OMT is a well-established hands-on technique that aims to diagnose and treat somatic dysfunctions through targeted manipulations [6-9] GTI involves subtle, non-invasive contact designed to enhance proprioception and promote relaxation without applying direct mechanical force. Both interventions are commonly employed in clinical settings to manage musculoskeletal pain, improve mobility, and enhance overall well-being [7-9]. However, their respective impacts on spinal posture, particularly when measured using advanced, non-invasive technologies like Spine3D, are less understood.

The aim of this study was to explore and quantify the effects of posture analysis after manual therapies interventions using rasterstereographic methods. By assessing specific postural parameters (cervical arrow, lumbar arrow, kyphotic angle, and lordotic angle), we aimed to determine how these interventions influence spinal curvature and postural alignment on the sagittal plane over a short-term period. Our findings will contribute to a growing body of research that seeks to validate non-invasive posture analysis technologies and enhance understanding of how manual therapies can modify spinal alignment in both clinical and non-clinical populations.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

This study was conducted as three armed randomized controlled trial (RCT). The protocol was written according to the Helsinki declaration and approved by the Independent FSL Ethics Committee (Prot. Number CE/2023_029 approved on 09-05-23). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants according to the FSL ethical procedures, before participating. The recruitment document explained that participation was voluntary, without incentives for participants, and dependent on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. All interested participants received information about the project by telephone and were briefly interviewed by a clinician not involved in the intervention sessions, to assess eligibility according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria reported below. 165 healthy individuals (median age 28,51 ± 5,77 years, height 173,64 ± 9,45 cm, weight 69,43 ± 13,31 kg, 46 female) were recruited for the experimental protocol. The inclusion criteria were: age between 18 and 45 years. Exclusion criteria included: (i) cognitive impairment, based on Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) [

7] score ≤ 24 according to norms for the Italian population [

8], (ii) medical illnesses, e.g., diabetes (not stabilized), obstructive pulmonary disease, or asthma; hematologic and oncologic disorders; pernicious anemia; clinically significant and unstable active gastrointestinal, renal, hepatic, endocrine, or cardiovascular system diseases; newly treated hypothyroidism; (iii) current or reported orthopaedic or neurological disorders; iv) history of pain in the last 6 months; v) pregnancy.

The total of 165 healthy participants were enrolled and randomized into three groups using SPSS software (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences–Chicago, IL, USA): the control (CTRL) group, the OMT group and the GTI group. Each participant underwent two testing sessions, spaced 48 hours apart (S1: first session; S2: second session). Participants in the CTRL group were evaluated after a two-day interval, without receiving any treatment between S1 and S2. Individuals in the OMT group underwent OMT based on a global approach [

9]. Somatic Dysfunctions (SDs) were identified, balanced, and subsequently treated using a range of available osteopathic techniques. For the participants enrolled in the TOUCH group, the treatment was performed by the same osteopaths and consisted of a passive soft touch of lumbar and dorsal spine, shoulders, hips, neck, sternum and chest without joint mobilization in a protocolled order [

9].

2.2. Experimental Setup

Data were acquired using the Spine3D non-invasive three-dimensional optoelectronic detection system developed by Sensor Medica (Guidonia Montecelio, IT) [

5]. This system is equipped with an infrared (IR) time-of-flight (ToF) 3D RGB camera, which is mounted on a motorized column and controlled via a joystick. The camera has a resolution of 1920x1080 pixels at 30 frames per second (fps) for RGB imaging and 512x424 pixels at 30 fps for depth resolution, with horizontal and vertical fields of view of 70° and 60°, respectively. The operational measurement range spans from 0.5 to 4.5 meters. The ToF camera allows for real-time estimation of the distance between the camera and the participant. The operator adjusted the camera’s position using the joystick to ensure the individual’s body, from the nape to the gluteal region, was properly framed. Each Spine3D acquisition took approximately 7 seconds. During the experimental procedure, for both testing sessions, participants were instructed to maintain a natural and comfortable posture.

2.3. Data Analysis

Upon reconstructing the dorsal surface via time-of-flight (ToF) technology, the software automatically identifies six anatomical landmarks, following the methodology outlined in [

10]. These landmarks include the vertebra prominent (VP), corresponding to the spinous process of C7; the right (SR) and left (SL) acromial apices, located at the midpoint between the superior aspect of the shoulder and the axillary concavity; the right (DR) and left (DL) posterior superior iliac spines (PSIS), with the midpoint between them (DM) also calculated; and the sacral prominence (SP), positioned at the superior aspect of the intergluteal sulcus.

Following landmark identification, several key parameters related to the sagittal profile were computed: i) cervical arrow (CA), ii) lumbar arrow (LA), iii) kyphotic angle (KAn), and iv) lordotic angle (LAn). Specifically CA is defined as the distance between the most anterior point of the cervical spine and a line perpendicular to the ground, tangent to the apex of the kyphotic curve; LA represents the distance between the most anterior point of the lumbar spine and the same perpendicular line tangent to the kyphotic curve; KAn is the angle formed by the intersection of the tangents at the cervicothoracic and thoracolumbar junctions; and LAn is the angle formed at the intersection of tangents at the thoracolumbar and lumbosacral junctions [

5].

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical tests were performed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Software (SPSS), version 12.0 (Chicago, IL) for all the parametric indexes (CA, LA, Kan, Lan). Descriptive statistics were assessed for all variables. Before statistical comparisons were made, a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was performed to evaluate the distribution of the data. For each group (CTRL, OMT and TOUCH), the differences in the indexes or demographic data between the S1 and S2 were assessed with the Paired t-test at S1, as well as at S2, repeated measures ANOVA was adopted to analyze differences among groups (CTRL vs OMT vs TOUCH) with treatment as the main within-group factor, followed by Bonferroni post-hoc test when the ANOVA results reached significance. Statistical significance was considered at p < 0.05 (*p < 0.05, **p < 0.005, ***p < 0.001).

3. Results

No one withdraw from the trial and all indexes were collected for the whole cohort of participants at S1 and S2. No statistical differences in the demographic data or in the assessed indexes (CA, LA, Can and Lan) were reported among CTRL, GT and OMT group at the S1.

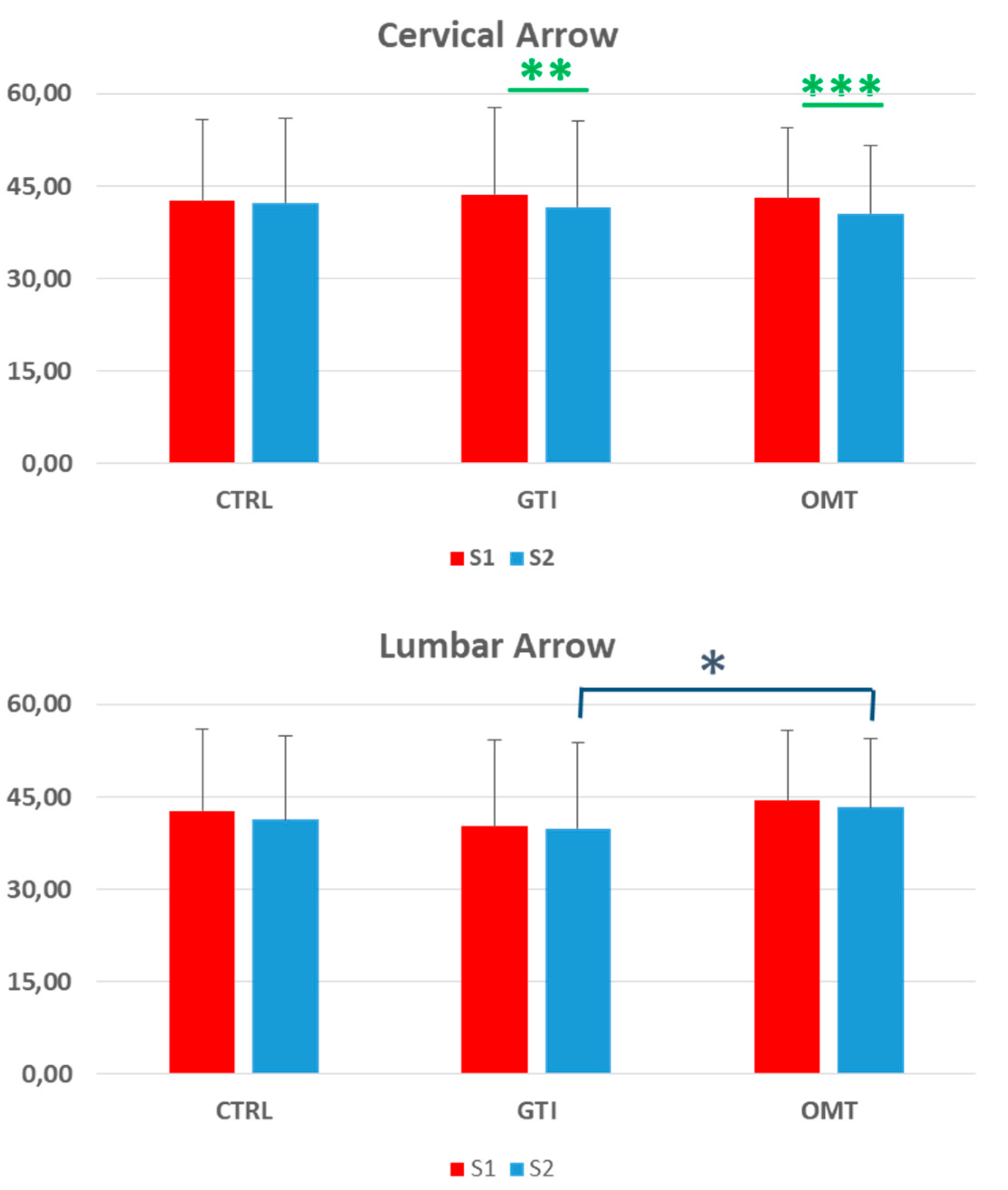

Data related to the CA index showed no significant changes between S1 and S2 in the CTRL group. Conversely, for both the GT group (p<0.05) and the OMT group (p<0.005) a significant CA reduction at S2 compared to S1, was underpin (See

Figure 1).

Results concerning the LA index indicated a general trend of values reduction at S2 compared to S1; however, statistical analysis did not reveal any significance (p > 0.05) (See

Figure 2).

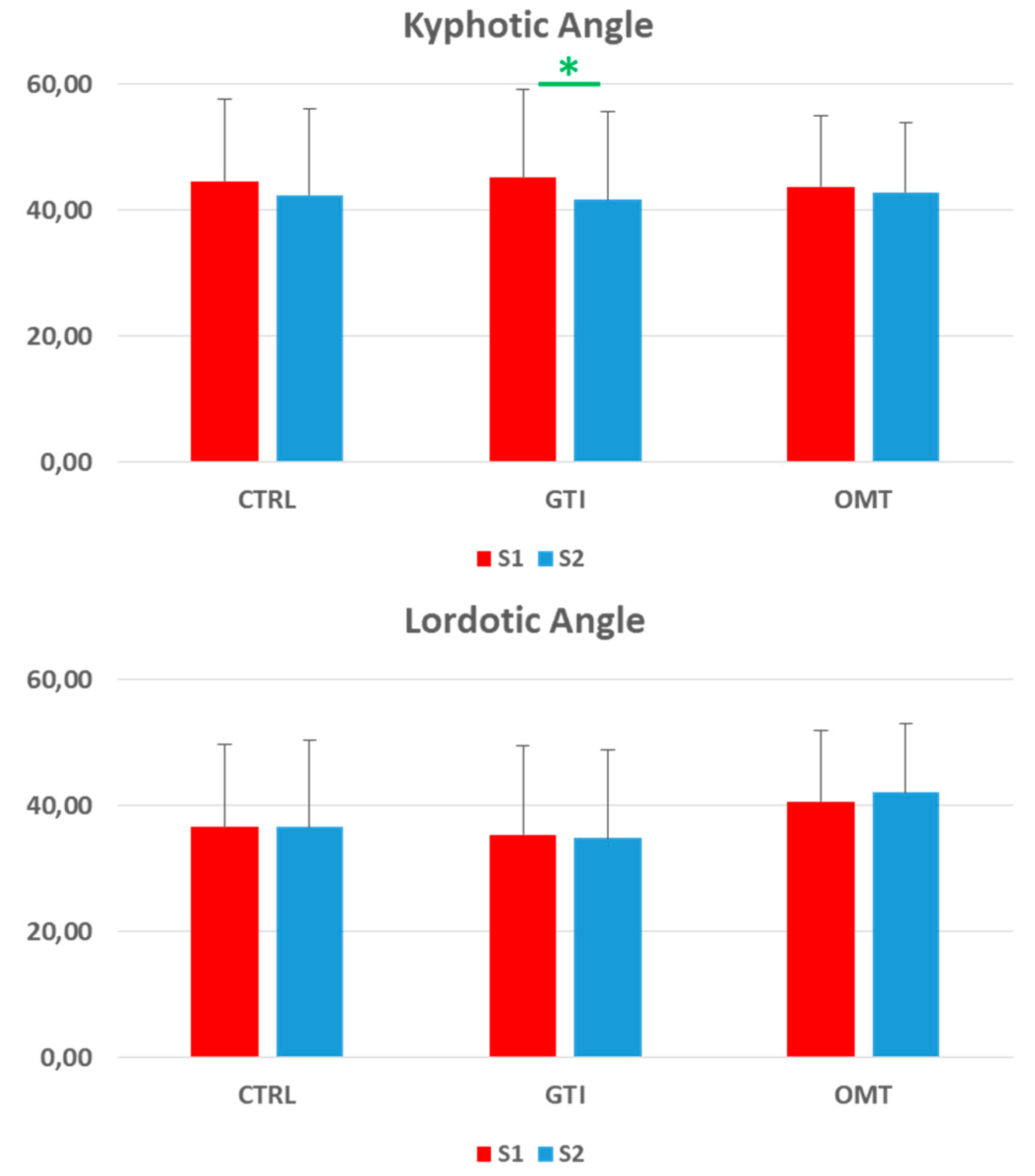

Data related to the Kan index indicate a general trend of reduction in values after 48 hours, which is statistically significant only in the GTI group (p < 0.05). No significant variations were observed in any group (CTRL, GTI or OMT) regarding the Lan index, where values showed no substantial changes between the two evaluation sessions.

4. Discussion

Our study aimed to investigate the effects of manual therapy intervention on spinal posture in the sagittal plane using the Spine3D non-invasive three-dimensional optoelectronic detection system. This system provided a 3D reconstruction of participants’ spinal profiles, allowing for the analysis of key postural indexes. As this was a self-controlled three arms RCT, we ensured that all participants were assessed immediately both before (S1) and after (S2) the intervention, facilitating the observation of potential modifications in their postural indexes. In line with Molinaro et al [

5] suggestion about instrument reliability, we performed for each participant two assessment 48 hours apart.

The results obtained demonstrated significant changes in specific postural parameters after manual therapy, on the contrary no changes in the CTRL were detected. Specifically, the CA index showed a statistically significant reduction in both the GTI and OMT groups, suggesting that this kind of instrumental evaluation is able to objectivate postural changes. Furthermore, both interventions had a measurable effect on cervical posture. These findings are consistent with previous research indicating improvements in postural parameters following manual therapy, particularly in the cervical region [

11]. The mechanism by which these changes occur is still debated and could be due to physical changes in tissue, neural adaptations, or recalibrations in proprioception caused by the interventions.

A key distinction in our study was the comparison between the effects of OMT and GTI. While both interventions produced changes in spinal posture, particularly in the cervical and thoracic regions, the mechanisms and potential clinical implications of these two interventions differ significantly. OMT involves a structured, hands-on approach that targets specific somatic dysfunctions through a range of osteopathic techniques, such as soft tissue manipulation, high-velocity low-amplitude thrusts, and myofascial release [

12]. OMT is designed to directly influence the musculoskeletal, vascular [

9], and neural systems [

13] to promote better alignment and function. In our study, the OMT group demonstrated significant reductions in the CA index, indicating an improvement in cervical alignment, and although the LA index showed a trend of reduction, even it did not reach statistical significance. These results align with the therapeutic goals of OMT, which aims to restore structural balance and optimize body function.

In contrast, GTI involves light, non-invasive contact with the body, with minimal mechanical input [

14,

15,

16]. Despite this, our results show that GTI was able to produce significant reductions in the CA and KAn indexes. The reduction in KAn in the GT group was particularly interesting, as it was statistically significant (p<0.05), while this effect was not observed in the OMT group. This suggests that GTI, despite its more subtle nature, might influence the thoracic curvature by enhancing proprioception or inducing a relaxation response in superficial tissues. GTI has been thought to promote relaxation and sensory awareness, which may lead to postural adjustments through neurophysiological pathways rather than direct mechanical effects [

17]. In newborns, skin-to-skin contact induces important psychoneuroimmunoendocrine changes with the production of oxytocin, reduction of acute pain [

18], reduction of jaundice disease and increase good sleep, increase in resilience and increase in life expectancy [

19,

20].

The differences between these two interventions, GTI and OMT, suggest that both may be working through distinct physiological mechanisms. OMT appears to have a more direct impact on musculoskeletal structures, targeting specific dysfunctions through manual techniques, while GT may influence posture by modulating proprioceptive feedback or promoting relaxation. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that both groups demonstrated improvements in the CA index, yet only the GTI group showed significant changes in the Kan, highlighting a unique response to this intervention.

The lack of significant findings in the LA index across all groups raises questions about the responsiveness of the lumbar region to manual therapies over short-term intervals. While OMT and GTI both influenced cervical and thoracic parameters, the lumbar spine may require longer-term intervention or more focused treatment techniques to exhibit statistical and meaningful changes. This observation is consistent with previous researches, which often reports more subtle changes in lumbar curvature compared to other regions of the spine following manual therapy [

21].

Moreover, our study found no significant changes in the LAn in any of the groups, suggesting that thoracolumbar curvature remains relatively stable in response to short-term interventions. This stability could be due to the biomechanical properties of the lumbar spine, which is generally more resistant to change due to its role in weight-bearing and overall spinal stability. The non-significant findings in the CTRL group for all postural indexes addressed reinforce the notion that the changes observed in the GTI and OMT groups were intervention-specific and not due to natural postural variability. The absence of statistical differences in demographic characteristics or baseline (S1) postural parameters among the three groups supports the robustness of our study design.

Our findings support the utility of both OMT and GTI as viable manual therapies for influencing spinal posture, particularly in the cervical region. For clinicians, this suggests that both therapies can be effective tools for modulating posture, but they may be appropriate for different therapeutic goals. OMT, with its hands-on, targeted approach, may be more suited for patients with specific musculoskeletal dysfunctions requiring correction, while GT might be more appropriate for individuals seeking relaxation or subtle postural adjustments without the need for deeper mechanical intervention.

Given that GTI produced significant changes in the kyphotic angle, it could be considered a valuable therapy for patients who are sensitive to more forceful manipulative techniques or who prefer a less invasive approach. Additionally, Gentle Touch could serve as a complementary therapy to OMT, especially in cases where manual therapy is contraindicated or when a gentler approach is desirable for promoting neurophysiological balance.

Future studies could explore the potential relationship between modifications in spinal posture and the autonomic nervous system (ANS) acitivity. It is well established that OMT affects the ANS. Several studies [

9,

13,

22,

23] have shown that OMT induces a significantly greater parasympathetic response compared to sham or no-touch procedures. Cerritelli et al. [

24] expanded this evidence, demonstrating that OMT influences heart rate variability parameters alongside facial temperature changes. Similarly, Ioannou et al. [

25], using high-resolution thermal infrared imaging, reported significant temperature increases in specific facial regions recognized as proxies for ANS activity following OMT. Considering these findings on OMT’s effects on the ANS, it would be valuable to further investigate with devoted studies the relationship between changes in spinal curves and autonomic reactivity.

Limitations

As with any study, there are limitations that must be acknowledged. Our cohort consisted of healthy participants without spinal deformities or significant musculoskeletal or neurological disorders. Therefore, the results may not be directly generalizable to clinical populations with conditions such as scoliosis, chronic back pain, or other musculoskeletal disorders. Future research should focus on investigating the effects of OMT and GT in clinical populations to better understand their therapeutic potential. Additionally, while the Spine3D system provides an effective means of analyzing external postural changes, it does not offer insights into the internal anatomical structures of the spine. Consequently, we cannot determine whether the observed postural changes were accompanied by alterations in vertebral alignment or deeper tissue structures. Future studies incorporating imaging techniques such as MRI could offer a more comprehensive understanding of the effects of manual therapy on both external and internal anatomy. Lastly, our study assessed only short-term postural changes following manual therapy, with follow-up conducted 48 hours post-intervention. Long-term follow-up is necessary to ascertain whether the postural improvements observed in this study are sustained over time and contribute to functional benefits such as pain relief or improved mobility.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that manual therapy interventions can lead to significant changes in spinal posture on the sagittal plane, particularly in the cervical and thoracic regions. While OMT appears to exert its effects primarily through direct mechanical influences on the musculoskeletal system, GTI may induce changes via neurophysiological mechanisms. Both therapies offer potential benefits for postural modulation, with GTI standing out as a gentle yet effective approach for influencing thoracic posture. Future studies should explore the long-term effects of these interventions and investigate their application in broader clinical populations, including those experiencing pain.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.S. and M.T.; methodology, F.T, J.P.; formal analysis F.T., M.T; investigation, A.G. and A.P.; resources, F.S. and A.P.; data curation, A.G., A.P. and J.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.T., F.T..; writing—review and editing. F.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The protocol was written according to the Helsinki declaration and approved by the Independent FSL Ethics Committee (Prot. Number CE/2023_029 approved on 09-05-23).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants according to the FSL ethical procedures, before participating.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be shared by upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Michalik, R.; Hamm, J.; Quack, V.; Eschweiler, J.; Gatz, M.; Betsch, M. Dynamic spinal posture and pelvic position analysis using a rasterstereographic device. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2020, 15, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roggio, F.; Ravalli, S.; Maugeri, G.; Bianco, A.; Palma, A.; Di Rosa, M.; Musumeci, G. Technological advancements in the analysis of human motion and posture management through digital devices. World J. Orthop. 2021, 12, 467–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drerup, B.; Hierholzer, E. Evaluation of frontal radiographs of scoliotic spines—Part I measurement of position and orientation of vertebrae and assessment of clinical shape parameters. J. Biomech. 1992, 25, 1357–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassani, T.; Stucovitz, E.; Galbusera, F.; Brayda-Bruno, M. Is rasterstereography a valid noninvasive method for the screening of juvenile and adolescent idiopathic scoliosis? Eur. Spine J. 2019, 28, 526–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molinaro, L.; Russo, L.; Cubelli, F.; Taborri, J.; Rossi, S. Reliability analysis of an innovative technology for the assessment of spinal abnormalities. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Symposium on Medical Measurements and Applications (MeMeA), Messina, Italy, 22–24 June 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amico, M.; Kinel, E.; Roncoletta, P. Normative 3D opto-electronic stereo-photogrammetric posture and spine morphology data in young healthy adult population. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folstein, M.F.; Folstein, S.E.; McHugh, P.R. “Mini-Mental State”. A Practical Method for Grading the Cognitive State of Patients for the Clinician. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1975, 12, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazzi, M.C.; Iavarone, A.; Russo, G.; Musella, C.; Milan, G.; D’Anna, F.; Garofalo, E.; Chieffi, S.; Sannino, M.; et al. Mini-Mental State Examination: New normative values on subjects in Southern Italy. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2020, 32, 699–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tamburella, F.; Piras, F.; Piras, F.; Spanò, B.; Tramontano, M.; Gili, T. Cerebral Perfusion Changes After Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment: A Randomized Manual Placebo-Controlled Trial. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledwoń, D.; Danch-Wierzchowska, M.; Bugdol, M.; Bibrowicz, K.; Szurmik, T.; Myśliwiec, A.; Mitas, A.W. Real-Time Back Surface Landmark Determination Using a Time-of-Flight Camera. Sensors 2021, 21, 6425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, S.; Balthillaya, G.; Neelapala, Y.V.R. Immediate effects of cervicothoracic junction mobilization versus thoracic manipulation on the range of motion and pain in mechanical neck pain with cervicothoracic junction dysfunction: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Chiropr. Man. Ther. 2020, 28, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramontano, M.; Tamburella, F.; Farra, F.D.; Bergna, A.; Lunghi, C.; Innocenti, M.; Cavera, F.; Savini, F.; Manzo, V.; D’alessandro, G. International Overview of Somatic Dysfunction Assessment and Treatment in Osteopathic Research: A Scoping Review. Healthcare 2021, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tramontano, M.; Cerritelli, F.; Piras, F.; Spanò, B.; Tamburella, F.; Piras, F.; Caltagirone, C.; Gili, T. Brain Connectivity Changes after Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment: A Randomized Manual Placebo-Controlled Trial. Brain Sci. 2020, 10, 969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croy, I.; Sehlstedt, I.; Wasling, H.B.; Ackerley, R.; Olausson, H. Gentle touch perception: From early childhood to adolescence. Dev. Cogn. Neurosci. 2019, 35, 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gessa, A.; Greaves, I.; Draper-Rodi, J. The role of touch in osteopathic clinical encounters—A scoping review. Int. J. Osteopat. Med. 2023, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGlone, F.; Cerritelli, F.; Walker, S.; Esteves, J. The role of gentle touch in perinatal osteopathic manual therapy. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2017, 72, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckstein, M.; Mamaev, I.; Ditzen, B.; Sailer, U. Calming Effects of Touch in Human, Animal, and Robotic Interaction—Scientific State-of-the-Art and Technical Advances. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castral, T.C.; Warnock, F.; Leite, A.M.; Haas, V.J.; Scochi, C.G. The effects of skin-to-skin contact during acute pain in preterm newborns. Eur. J. Pain 2008, 12, 464–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widström, A.; Brimdyr, K.; Svensson, K.; Cadwell, K.; Nissen, E. Skin-to-skin contact the first hour after birth, underlying implications and clinical practice. Acta Paediatr. 2019, 108, 1192–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergman, N.J. New policies on skin-to-skin contact warrant an oxytocin-based perspective on perinatal health care. Front. Psychol. 2024, 15, 1385320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, J.M.; Haq, I.; Lee, R.Y. The effect of pain relief on dynamic changes in lumbar curvature. Man. Ther. 2013, 18, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruffini, N.; D’Alessandro, G.; Mariani, N.; Pollastrelli, A.; Cardinali, L.; Cerritelli, F. Variations of high frequency parameter of heart rate variability following osteopathic manipulative treatment in healthy subjects compared to control group and sham therapy: randomized controlled trial. Front. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farra, F.D.; Bergna, A.; Lunghi, C.; Bruini, I.; Galli, M.; Vismara, L.; Tramontano, M. Reported biological effects following Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment: A comprehensive mapping review. Complement. Ther. Med. 2024, 82, 103043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerritelli, F.; Cardone, D.; Pirino, A.; Merla, A.; Scoppa, F. Does Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment Induce Autonomic Changes in Healthy Participants? A Thermal Imaging Study. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ioannou, S.; Morris, P.; Mercer, H.; Baker, M.; Gallese, V.; Reddy, V. Proximity and gaze influences facial temperature: a thermal infrared imaging study. Front. Psychol. 2014, 5, 845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).