1. Introduction

In various domains, such as artificial intelligence, self-driving vehicles, and virtual reality, the significance of 3D point cloud technology cannot be overstated. Current research focuses on the development of accurate 3D point cloud maps due to the rapid progress in intelligent technology. This technology enables robots and autonomous vehicles to acquire precise and detailed environmental perception data, which is invaluable for tasks such as navigation, obstacle avoidance, path planning, and object recognition. However, specific challenges are currently associated with the construction of 3D point clouds. Currently, the most effective approach to tackle these challenges involves utilizing multiple sensors for observation and leveraging various data modalities to address issues such as sparsity and non-uniform distribution in point-cloud data. For instance, lidar sensors often generate point cloud data that are sparse and incomplete at the edges, leading to a loss of detailed scene information. To mitigate this problem, multimodal fusion can enhance perception integrity. However, this method does increase the computational burden and generates redundant data, thereby significantly increasing resource consumption. Moreover, dealing with redundant data imposes higher requirements on subsequent tasks, such as registering and segmenting point clouds, making them more complex. On the other hand, generative techniques offer a novel solution for 3D point-cloud reconstruction by using random noise or Gaussian processes based on existing features. These methods have demonstrated promising performance, specifically for generating point clouds with regular shapes. However, existing generative approaches are limited to fixed shapes or simple scenes. They cannot meet the demands of complex real-world scenarios that often exhibit alternating sparse and dense areas with uneven distribution patterns. Traditional methods struggle to handle these challenges effectively.

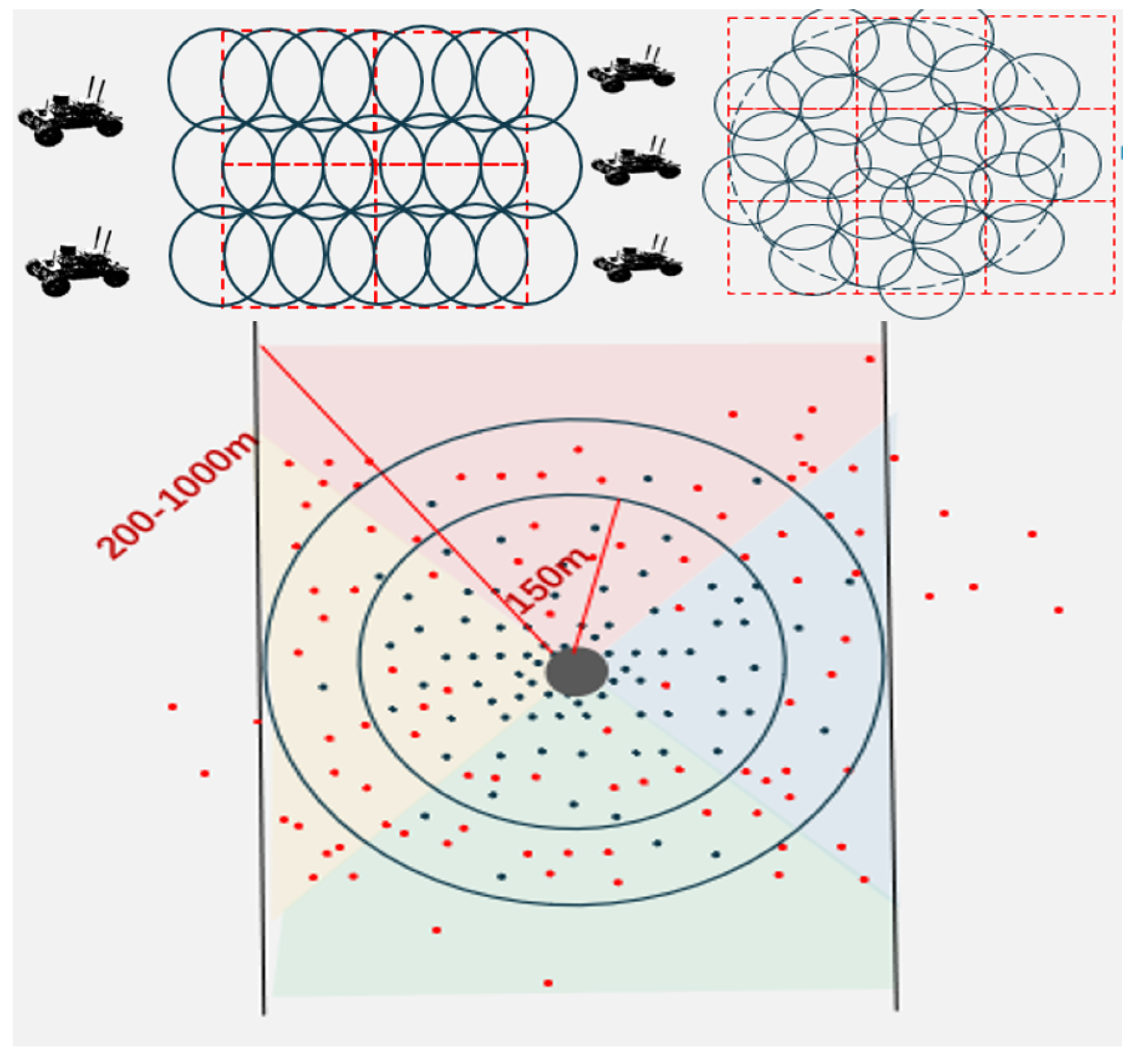

Figure 1.

Problem modeling, when multiple unmanned vehicles are engaged in ground data perception, information is lost due to sparse edges in the dense point-cloud data. To address this problem, ground equipment must be used to perform multiple perceptions of the lost areas. During the perception process in specific regions, the number of perceptions by unmanned vehicles has increased from 4 times to 21 times and 9 times to 26 times.

Figure 1.

Problem modeling, when multiple unmanned vehicles are engaged in ground data perception, information is lost due to sparse edges in the dense point-cloud data. To address this problem, ground equipment must be used to perform multiple perceptions of the lost areas. During the perception process in specific regions, the number of perceptions by unmanned vehicles has increased from 4 times to 21 times and 9 times to 26 times.

In addition to direct methods for generating point clouds, multimodal data-assisted approaches leverage image data to facilitate the conversion from 2D to 3D. These techniques establish prior conditions for point-cloud generation and enhance the quality of the resulting data. However, in resource-limited scenarios, repetitive generation of high-resolution and feature-dense regions may lead to resource wastage and pose challenges to other stages of constructing a 3D map. We propose an attention mechanism based on point cloud data density, which significantly improves the performance of the generative model. By integrating the attention mechanism with the normalization flow model, this model focuses only on generating point clouds in sparse regions, resulting in a more precise representation of shape features in 3D point-cloud map construction tasks and laying a foundation for subsequent tasks.

By prioritizing sparsely populated regions, the model enhances the precision of point cloud synthesis, guaranteeing improved alignment with real data while minimizing duplication in densely populated areas. This strategy effectively elevates the quality of generation and mitigates superfluous data.

By utilizing the combined advantages of image and point cloud data, the model enhances the overall precision of point clouds, enhancing both texture and geometry. Consequently, it elevates the overall representative capacity of the point cloud data.

Moreover, the model utilizes an attention mechanism based on the density of point clouds to generate specific regions that are sparsely distributed, guided by image information. This approach effectively addresses the issue of uneven and sparse characteristics commonly found at the periphery of point clouds while maintaining a balanced overall resolution.

We have successfully validated the effectiveness of this technique on a synthetic dataset called Shapenet and a real-world dataset called nuScience. Our experimental results demonstrate that our method is highly suitable for constructing 3D point cloud maps in real-world scenarios. The remaining structure of this paper is as follows:

Section 2 provides an overview of related literature;

Section 3 explains in detail our proposed methodology;

Section 4 presents the results obtained from experiments conducted on the Shapenet and nuScience datasets; finally, in

Section 5, we summarize and discuss possible future directions.

2. Related Work

2.1. Point Cloud Generation

Early point cloud generation methods [

1,

2,

3] typically involve converting point clouds into N×3 matrices for processing and using specific encoders to manipulate the matrices for shape understanding and generation tasks. For example, Panos Achlioptas et al. [

1] used a deep autoencoder (AE) network [

4] with algebraic operations to achieve shape editing such as semantic part editing, shape analogy, and shape interpolation. Matheus Gadelha et al. [

2], on the other hand, represented 3D shape features as ordered lists using one-dimensional convolutions. However, these methods suffer from low resolution, fixed shapes, and a lack of imagination in capturing point cloud features. AtlasNet [

5,

6] reconstructs specific parts of 3D shapes by establishing multiple neural network branches within an encoder-decoder architecture. At the same time, Groueix et al. [

7] represent 3D shapes as parameterized surface element sets that can generate arbitrary forms of point cloud data even under resource scarcity conditions. However, these methods require significant computational resources during inference and are not applicable in real-world scenarios, thus limiting their practical applications. Recently, there have been some works [

8,

9,

10,

11] based on Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), which mainly set specific 3D point cloud encoders-decoders as GAN generators and use discriminators with specialized properties to identify features of 3D point cloud data as the discriminator, improving the convergence speed of the model under the GAN training framework. Some works [

12,

13] also utilize flow models to obtain complete 3D point cloud data from arbitrary resolutions and combine variational encoders [

14] to achieve generation of 3D objects. In addition, Luo et al. [

3] introduced diffusion models into 3D scene generation, realizing the generation of three-dimensional coordinate data from scratch through forward and backward processes trained between random noise and real data, further promoting the development of three-dimensional coordinate generation technology. Although these works can generate models in real scenes, they only focus on overall generative capabilities without considering targeted point cloud generation based on sparse edge and dense core attributes. While this approach is not wrong, when facing unknown areas using multi-agent construction for 3D scenes, a large amount of redundant information will consume significant computational resources, making this method unsuitable for restrictive environments with scarce computing resources.

2.2. Point Cloud Completion

The point-cloud completion task is to generate complete 3D point cloud data using algorithms or multimodal information given partial point cloud [

15,

16]. Point cloud completion methods can be divided into traditional and deep learning-based methods [

17]. Traditional point cloud completion methods mainly rely on the standard geometric shape [

18], symmetry, and geometric properties of the point cloud to guide the completion process. However, due to the inability to accurately calculate geometric properties, traditional methods are not ideal for effectiveness. Deep learning-based point cloud completion methods have gradually replaced traditional methods in recent years. In the early stages, the focus was mainly on converting point cloud data into voxel format and predicting large-scale features based on local features [

19]. However, these methods often generate low-resolution completion results and are greatly influenced by the original point cloud resolution. Since PointNet [

20] and PointNet++ [

21] changed the way of processing, many works have started to utilize point cloud features for data completion [

22]. They [

22]represent point clouds as a set of unordered nodes with positional features and use Transformer transformers [

23]to generate complete 3D point cloud data. Additionally, they [

24] employ multi-layer perceptrons [

25]combined with residual networks to extract and preserve contextual information. They [

26] also propose differentiable trilinear feature sampling layers to obtain relevant features between neighboring nodes. Furthermore, by hierarchically extracting and fusing multiscale node features, they avoid information loss caused by a single global feature representation. By ensuring that each incomplete point moves along the shortest path in the Partially Movable Path (PMP) [

27] while strictly following the correspondence rules learned at the node level, they improve the quality of predicted 3D shapes. These novel techniques enable adaptive adjustment of matching relationships between input and output to better complete missing areas in real-world scenes.

3. Materials and Methods

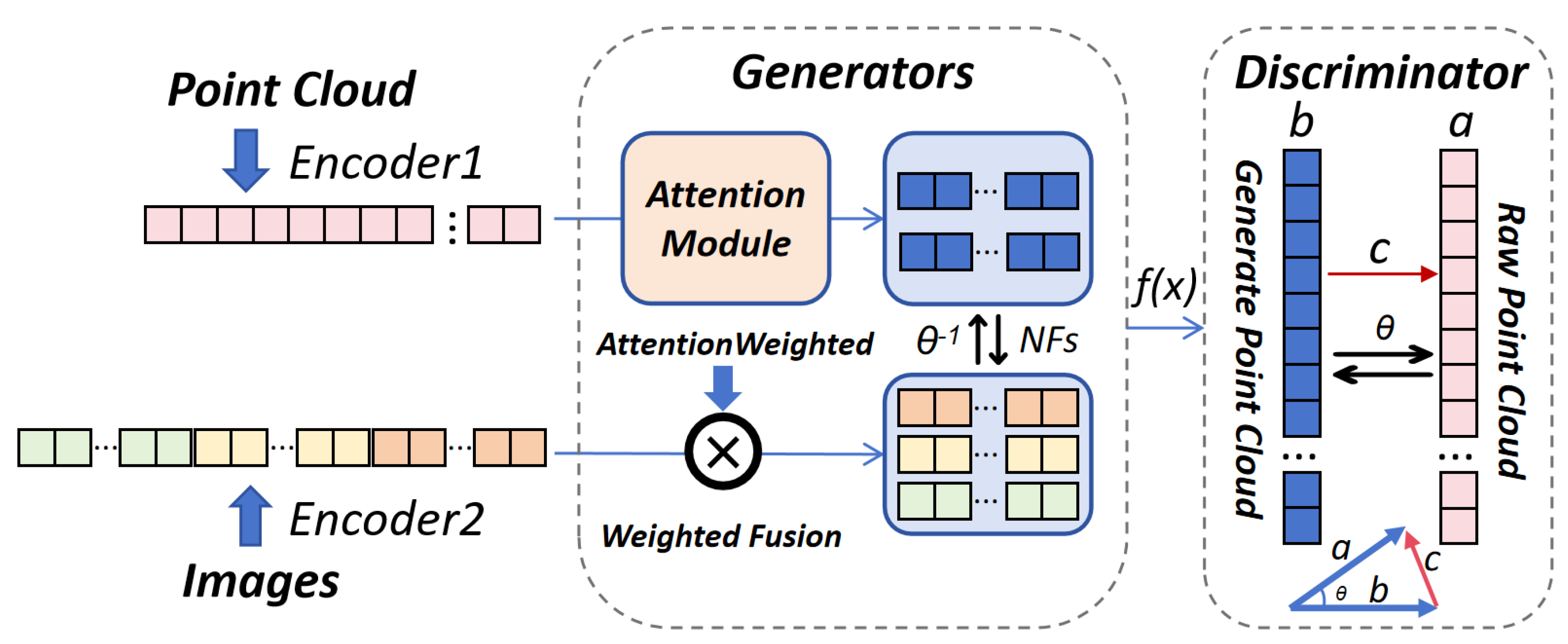

In this research, we focus on point cloud completion in constructing 3D point cloud maps while also considering the potential loss of semantic information for distant objects. To address this issue, a hybrid model combining attention mechanisms with explicit and implicit generation techniques is proposed to enhance the accurate description of distant scenes using point cloud data. Specifically, we utilize image features to recover missing semantic information and design a comprehensive solution consisting of a generator and discriminator.

3.1. Main Idea

The proposed model is founded on adversarial training within the framework of a Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) and exploits a decoder-variational autoencoder (VAE) architecture incorporating an integrated attention mechanism. This methodology explicitly integrates the attention mechanism during the fusion process, guaranteeing that the model focuses on the denser and more informative regions of the point cloud during generation. This helps alleviate the challenges arising from the sparsity and unevenness of point cloud data, where certain areas may contain more structural information while others may seem sparse. By enhancing the generator’s ability to perceive both image and point cloud features, the model generates more accurate and significant 3D point clouds.

The attention mechanism facilitates the weighted fusion of image and point cloud features, enabling critical regions in the image (e.g., object edges, surfaces) to be emphasized through higher attention weights. In contrast, essential areas in the point cloud (such as object contours and fine details) receive greater focus during the fusion process. This promotes more precise point cloud generation. The attention weights, based on point cloud density, effectively capture the distribution of fused points and image features. During training, maximum likelihood estimation is utilized to sample data that conforms to the point cloud feature distribution by estimating the fused image feature distribution.

After training, the generator can produce point cloud samples, while the discriminator distinguishes between real and fake point cloud data [

28]. In contrast to the majority of point cloud generation methods that focus solely on global representation, our approach caters to the requirements for both long-range object representation and local point cloud details, which are pivotal in tasks such as 3D map construction [

8,

9,

10,

11,

22,

24]. Finally, by marking the inference results as fake data and comparing them with the original point clouds, adversarial training is implemented to ensure the quality of the generated samples. By combining flow and attention mechanisms, our model adapts to handle sparse 3D information and overcomes the challenges of tasks such as 3D map construction, ultimately generating novel outcomes that meet the requirements.

3.2. Points Cloud Generator

The generator part of the model is responsible for integrating the density weighting information of the extracted point cloud data with the input image features while learning a linear reversible transformation between the fused image features and the extracted point cloud features. Here, PointNet++ [

21] version is used as an encoder to extract point cloud features. It achieves the functionality of PointNet [

20], enhances fine-grained perception capability, and focuses more on local feature extraction.

Then, the reversible transformation process between image data features and point cloud data features is achieved by calculating the fusion attention weight function, using normalized flows to implement this process. The specific implementation is as follows: firstly, latent representation vectors

z for image

I and point cloud

P are computed using domain-specific encoders

and

, where

z represents high-dimensional feature vectors. During training, the attention module calculates point cloud features based on density and obtains point cloud attention weights

. In the attention module, formula (1) is used to compare each point cloud feature representation

with other representations, and its weight in the attention mechanism is determined through exponential processing as

. The parameter

controls the shape of attention distribution; a larger value makes the weights more concentrated, while a smaller value makes them more evenly distributed. Then, all targets or elements are summed up, and the function outputs

represent the attention mechanism’s weight on target or element i. Finally, a weighted fusion of obtained point-based attention weights and image data results in fused characteristics according to formula (2).

Calculate the mean

and variance

of point cloud feature

P, estimate the probability distribution that conforms to specific domain features based on the mean and variance and use this distribution as an approximate posterior distribution instead of the particular domain posterior distribution. Utilize variational inference to replace the original posterior distribution

with an approximate posterior distribution

, where P represents point cloud features. Through a normalized flow model, learn a reversible transformation from a simple Gaussian prior distribution N(0,1) to a complex point cloud distribution. This normalized flow model consists of F affine coupling layers. This transformation has two directions: forward transformation (denoted as

) from simple prior distribution to point cloud distribution, and inverse transformation (denoted as

) from point cloud distribution back to simple prior distribution. These affine coupling layers aim to transform the latent variable’sdistribution into one that aligns with the point cloud feature’sdistribution while ensuring reversibility. In addition, under the condition of given fused point cloud attention weight image features, a flow model is used to fit the reversible transformation process between simple and complex distributions

fused with attention weight image features. Then, by minimizing the evidence lower bound (

), the lower bound of fused point cloud attention graph features is optimized to indirectly achieve distance between approximate image features and point cloud feature distributions. The calculation of

ELBO is shown in formula (3).

The

is a lower bound on the marginal log-likelihood of observed data, considering the differences between the model distribution and the variational approximation. By maximizing the

, we can make the variational approximation closer to the true posterior distribution, thereby approximating the distance between these two distributions.

In this formula,

represents the expected marginal log-likelihood of the observed data,

.

is the variational approximation to the posterior distribution, and

represents the prior distribution provided by point cloud data. The KL divergence term

is used to measure the difference between the variational approximation distribution and the true posterior distribution, which can be calculated using equation 4. To enable the model generator to perform inference reconstruction on 3D point cloud data given image data, we complete missing 3D information from 2D data and focus on sparse and uneven regions based on prior knowledge provided by 3D point cloud data for completion tasks. We draw inspiration from previous work [

13,

29] that introduced an attention mechanism to improve the model generator component and pay more attention to completion tasks in sparse and uneven regions compared to overall point cloud generation to reduce computational costs for overall tasks.

3.3. Points Cloud Discriminator

After completing the generator inference, we successfully simulated the distribution of point clouds in the real world and obtained highly realistic sample data. We adopted a method based on an adversarial training framework to improve the quality of generated samples and train the generator more effectively. We introduced a generative adversarial network (GAN) structure consisting of two components: a generator and a discriminator. In the discriminator, we aim to distinguish between fake point clouds generated by the generator and real point clouds. We chose Chamfer distance as an advanced similarity measurement method specifically designed for 3D point cloud data to compare differences between generated point clouds and real ones to achieve this goal. Unlike traditional pixel or voxel-based metrics, Chamfer distance can accurately measure whether these two sets of points are similar or different. By calculating the Chamfer distance, we can precisely evaluate their degree of difference. The Chamfer Distance (CD) is defined as:

Where:

P and Q are two point clouds (one generated and one real),

is the Euclidean distance between points and ,

and represent the number of points in each point cloud.

This distance measurement technology is designed to penalize the generator, guiding it to gradually produce more realistic point clouds when the generated points significantly differ from real-world data. To evaluate the effectiveness of the discriminator, we employ a loss function to promote adversarial behavior. In the Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) framework, similar to a game, the generator strives to deceive the discriminator while the discriminator endeavors to distinguish between real and fabricated data. The generator aims to minimize Chamfer distance and reduce differences, whereas the discriminator seeks to maximize these differences. This adversarial process ensures progressive improvement in generator performance. The optimization procedure used for training the discriminator can be expressed as follows:

Where:

D is the discriminator network,

represents real point clouds,

represents generated point clouds,

is the output of the generator when fed with noise input .

The generator is then trained to minimize the opposite objective, i.e., to make the discriminator unable to distinguish between real and fake point clouds. The generator’s loss function is given by:

In practical implementation, we incorporate feature extractors for each domain (including real and generated point clouds) to extract advanced 3D characteristics from the point clouds and input them into the discriminator. This ensures that the discriminator considers the original point coordinates and higher-level semantic features of the point cloud, thereby enhancing its ability to assess the quality of generated data. As depicted in

Figure 2, we utilize Chamfer distance as a metric to quantify the similarity between extracted features of real and generated point clouds. The feature extraction process involves methodologies such as PointNet or other techniques based on 3D convolution, which capture the point cloud’s geometric and semantic attributes. These characteristics are then compared using Chamfer distance, and generator and discriminator parameters are updated through network backpropagation. Through this iterative adversarial training framework, we progressively optimize the generator’s output towards generating more realistic and high-quality point clouds, ultimately improving our pipeline for generating 3D models.

4. Results

This section introduces relevant information, including the datasets used, evaluation metrics, and experimental settings. Then, based on both quantitative and qualitative evaluations, we present the performance of our model across multiple datasets and demonstrate its capabilities in tasks such as generation, completion, and unsupervised learning. Finally, the limitations of the method are discussed.

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.1.1. Dataset

We comprehensively evaluated the synthetic dataset ShapeNetCore.v1 and the real dataset nuScenes to assess our experiments. We chose the ShapeNet dataset because it includes complete object models not found in other datasets, such as ScanNet and S3DIS. The reason for selecting the nuScenes real dataset is that our application primarily focuses on 3D scene completion tasks, and this dataset contains autonomous driving scenes from multiple cities worldwide, which closely resemble real-world scenarios. ShapeNetCore.v1 is a subset of the ShapeNet dataset, an extensive database containing 55 categories and providing complete objects in 3D shapes and 2D images. This dataset meets our requirement for corresponding relationships between model image data and point cloud data samples and has been widely used for experimental validation in most point cloud completion tasks, providing convenience for our upcoming model comparison experiments. The nuScience dataset is a large-scale public dataset for autonomous driving, consisting of 1000 scenes. It is one of the largest and most complete real-world datasets after the KITTI dataset. In our research task, we aim to enhance the edge representation capability of outdoor point cloud data, and in this regard, the nuScience dataset perfectly meets our needs. Therefore, we conducted feasibility verification experiments on scene completion based on the nuScience dataset.

4.1.2. Evaluation Metrics

To validate the model’s feasibility, we conducted comparative experiments using evaluation metrics such as Chamfer Distance (CD), Earth Mover’s Distance (EMD), and F1 score to assess the similarity between generated point clouds and real ones, aiming to determine their effectiveness.

where

f is a point alignment function that maps each point in

P to a corresponding point in

Q, and

denotes the Euclidean distance."

" represents true positives, which are instances accurately identified as positive.

Precision and recall are defined as follows:,,stands for false positives, which are instances mistakenly identified as positive. "" represents false negatives, which are instances mistakenly identified as negative. The F1 score is advantageous due to its ability to balance precision and recall effectively. It is highly suitable for evaluating object recognition and segmentation tasks in sparse and complex point cloud data scenarios.

By comprehensively utilizing the CD and EMD metrics, we can evaluate the similarity of point clouds from both geometric and spatial distribution perspectives. The F1 score, on the other hand, assesses their accuracy in object recognition and segmentation. By integrating these three metrics, we can more comprehensively validate the performance of models in complex environments and ensure that the generated point clouds not only closely resemble real data spatially but also effectively reflect the model’s performance in point cloud generation and reconstruction tasks.

4.1.3. Training Details

The experiment was conducted on a GPU with a single Nvidia 3090 graphics card driver, cuda12.1 version, and PyTorch deep learning environment. This GPU has 24GB of memory. To validate the feasibility of our model, we first evaluated its performance on the ShapeNet dataset for point cloud completion. Our model showed better learning results on this dataset compared to other models. During training, the model takes a single image and point cloud as input samples and randomly selects a pair of image and point cloud samples from the same category dataset as input. In addition, we also verified the feasibility of our model’s point cloud completion performance in real-world scenarios using the nuScience real dataset. Compared to baseline models, our model demonstrated excellent performance when processing point cloud data in real-world scenes, and ablation experiments also proved that attention modules have superior performance in our model. During the training phase, each input consists of eight image samples and one point cloud sample, respectively; image feature vectors are extracted using ResNet50 [

30] while PointNet++ [

21] is used for extracting point cloud features; these features are then concatenated to generate overall training samples containing global feature information which are passed into the model as inputs. A direct visualization display is performed to intuitively evaluate the effects of completed point cloud data. When using real point cloud data as input, only 2500 sampled points are selected for training purposes, while the Adam optimizer adjusts parameter learning rates to minimize loss functions.

4.2. Point Cloud Generation

Our model was trained using samples from the Airplane and Car categories in the ShapeNet dataset and validated against advanced works such as PointFlow [

29] and AtlasNet [

5]. Firstly, comparative experiments were conducted on the ShapeNet dataset to validate the feasibility of generating point cloud models. Our model generated 2048 points each, which were then normalized and mapped to a [-1,1] bounding box while maintaining total control over quantity. This allowed for a fair comparison of different methods regarding point cloud quality at the same scale. The Chamfer Distance (CD), Earth Mover’s Distance (EMD), and F1 score were used to measure the similarity between generated and original point clouds. As shown in

Table 1, our model outperformed both benchmark models regarding CD and F1 scores. These experiments significantly improved our proposed method on the synthetic dataset ShapeNet. Additionally, we utilized PointNet++ to classify the results obtained by this method on the ShapeNet dataset, showing that our generated point cloud data achieved higher classification accuracy, surpassing methods like PointFlow and AtlasNet. The experimental results are presented in

Table 2.

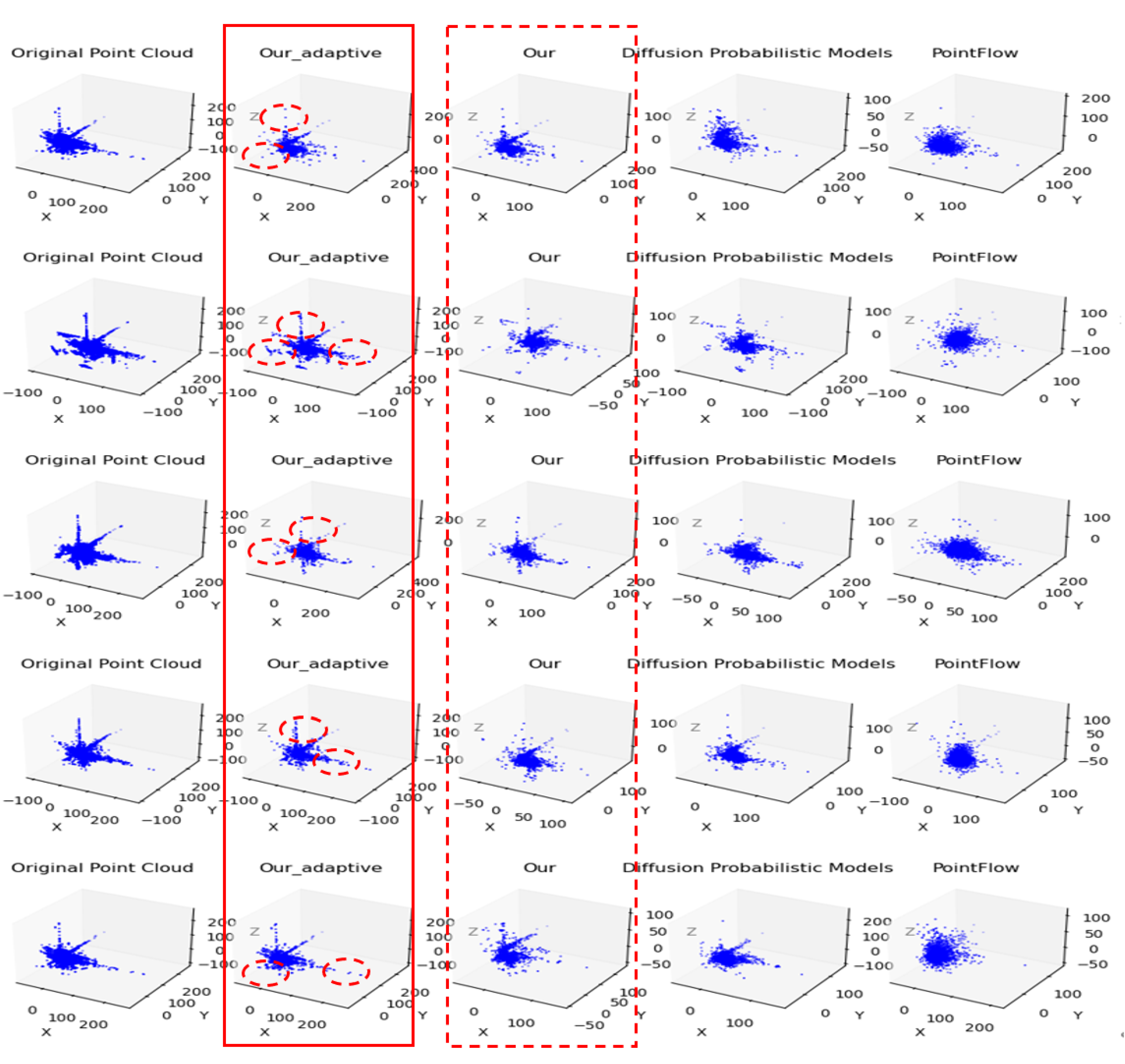

4.3. Comparison on 3D Generation Results

Our model is trained on the real dataset nuScience and generates point cloud data of real 3D scenes. In the evaluation, we use a subset of the scene as an evaluation dataset, which is not included in the training set. We compare our model with advanced point cloud generation models (Point Flow [

29], AtlasNet [

5], DPM [

3]) in experiments. After generating point cloud data using our model, we also normalize the generated samples for a more intuitive comparison of differences between results. Additionally, following previous settings, we control the number of points generated by the model to a fixed quantity (2048), which facilitates evaluating the sample generation capability of the model. To visually observe differences between generated samples, we visualize each model’s generated sample data and present them as shown in

Figure 3. The experimental results demonstrate that our model outperforms baseline methods in overall shape features and sparse point cloud completion on real datasets.

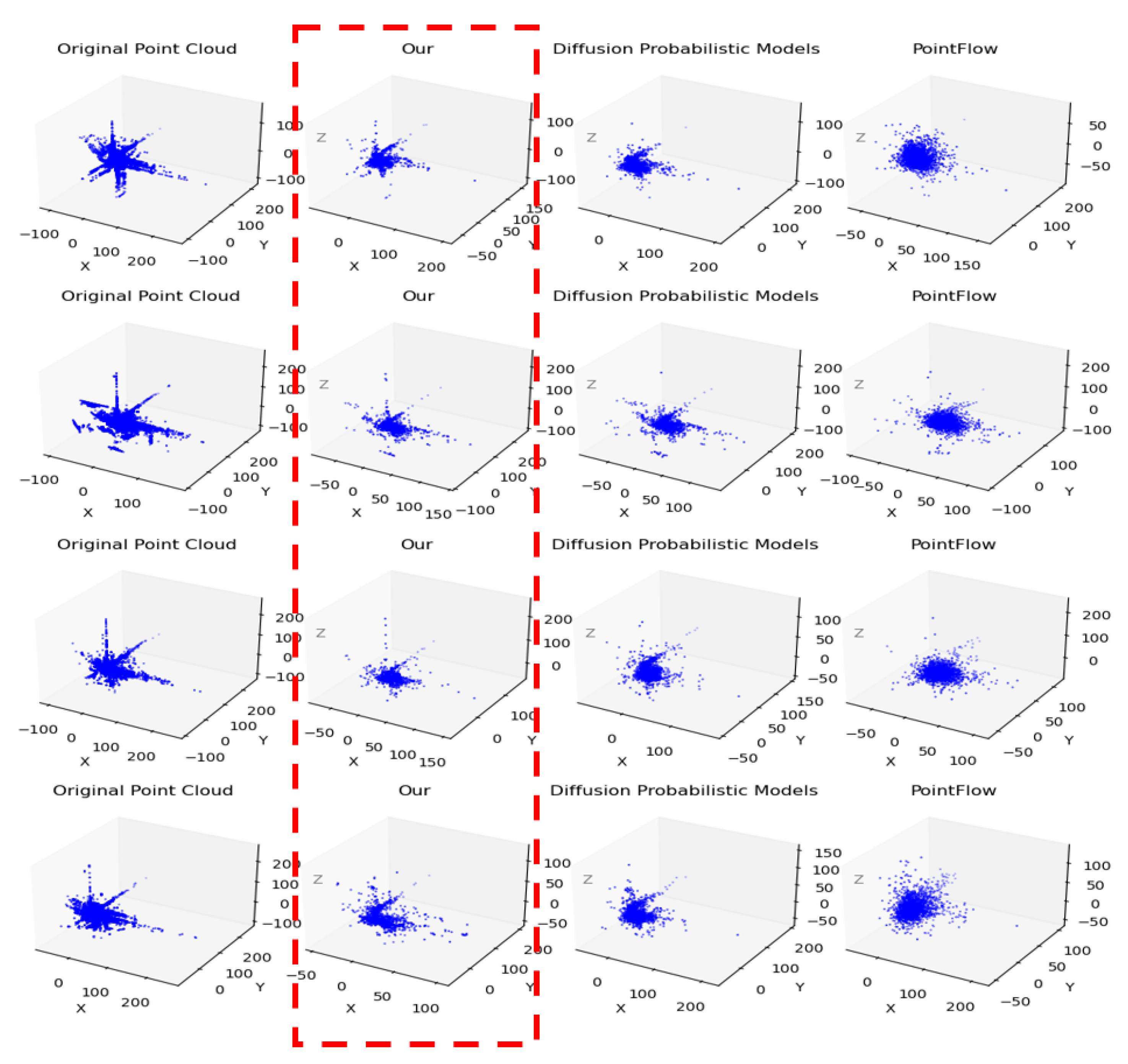

4.4. Ablation Study

We conducted ablation experiments to verify the overall enhancement effect of the attention module in our model. In this experiment, we directly used the trained point cloud data and image data as inputs to the generator. Using normalized flow learning, we established a reversible transformation function between the distribution of image data and point cloud data. We still generated point cloud samples with 2048 points consistent with previous settings. At the same time, comparative experiments were conducted with benchmark models mentioned earlier [

3,

5,

16,

29]. The results showed that the attention module significantly enhanced edge point cloud data and shape features.

Figure 4.

Ablation experiments were conducted on the nuScience dataset, and their results were presented through visualization. To better showcase how attention modules contribute to generating shape features during point cloud completion, we visualized the inference results from these ablation experiments and compared them with baseline models. Our method is more capable of completing sparse regions at the edges of point clouds while generating more precise shape features.

Figure 4.

Ablation experiments were conducted on the nuScience dataset, and their results were presented through visualization. To better showcase how attention modules contribute to generating shape features during point cloud completion, we visualized the inference results from these ablation experiments and compared them with baseline models. Our method is more capable of completing sparse regions at the edges of point clouds while generating more precise shape features.

5. Discussion

I-PAttnGAN exhibits excellent performance in point cloud completion, especially in sparse regions, and is capable of generating highly accurate and complete 3D point clouds in practical scenarios. The integration of image-assisted input and the attention mechanism significantly enhances the model’s generative capabilities, leading to superior performance in reconstructing missing regions. Notably, in the case of edge-sparse point clouds, the model excels in preserving the shape features, resulting in more consistent and uniformly distributed point cloud resolutions. The combined use of image data and attention mechanisms allows the model to focus intelligently on key regions during sparse data processing, thereby improving the overall quality of the generated point clouds.

When compared to existing point cloud completion methods—such as flow-based and grid-based generation approaches—I-PAttnGAN demonstrates marked advantages in terms of both generation quality and training efficiency. Its ability to leverage attention mechanisms, which prioritize important regions of the point cloud, allows for a more precise and efficient reconstruction process.

However, the approach employed by I-PAttnGAN, which involves utilizing point cloud attention modules based on image-derived key regions, is heavily reliant on the quality of the input images. The performance of the model can be significantly degraded when the input images are of poor quality, obstructed, or contain occlusions. In such cases, the generated point clouds may exhibit incomplete or inaccurate structures, which could adversely impact downstream tasks, such as map construction. This issue becomes particularly problematic in real-world applications, where point cloud data often comes from diverse sources, and the associated images may not always meet the quality standards required for optimal performance.

Moreover, the model’s adaptability diminishes when confronted with noisy data in complex, unknown outdoor scenes. The presence of substantial noise in point cloud data further exacerbates the challenge, particularly in scenarios where the environmental context and scene characteristics vary widely. Consequently, the model’s performance may degrade when applied to diverse, real-world datasets, limiting its ability to handle the variability inherent in different scene types.

To address these challenges, future work could focus on improving the model’s robustness to low-quality or noisy input data, possibly through the incorporation of multi-view data, depth maps, or advanced denoising techniques. Additionally, exploring methods for enhancing the model’s adaptability to diverse scenes, such as through domain adaptation strategies or the use of more generalized training data, may help to extend the applicability of I-PAttnGAN to a broader range of real-world applications.

6. Conclusions

In this study, we have put forward I-PAttnGAN, an image-assisted point cloud completion network that effectively handles the challenge of generating high-quality point clouds, especially in sparse regions. The model combines image data with a sturdy attention mechanism, facilitating the intelligent reconstruction of missing or inadequately represented areas, especially in edge-sparse regions. By enhancing the local structure and uniformity of the generated point clouds, I-PAttnGAN outperforms existing point cloud completion techniques in both quality and training efficiency.

Despite its encouraging performance, this method is susceptible to the quality of input images, which can constrain the model’s robustness in real-world applications where image quality is variable or data is noisy. Additionally, difficulties remain when applying the model to complex, unknown outdoor scenes, where the model’s adaptability might decrease. These limitations illuminate critical areas for future research, particularly in enhancing the model’s resistance to low-quality and noisy input data.

Looking ahead, our next steps will be focused on making use of the generated point clouds, especially in the sparse regions, for efficient low-overlap point cloud registration. By relying on the accuracy and completeness of I-PAttnGAN’s output, we aim to improve the registration process, particularly in situations where traditional methods have trouble with low overlap between point clouds. This work will contribute to more efficient 3D reconstruction and map building in dynamic and challenging environments, opening new paths for applications in autonomous navigation, robotics, and beyond.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Wenwen Li and Yaxing Chen; methodology, Wenwen Li, Yaxing Chen and Qianyue Fan; software, Wenwen Li and Qianyue Fan; validation, Yaxing Chen; formal analysis, Yaxing Chen; investigation, Wenwen Li and Yaxing Chen; resources, Yaxing Chen, Bin Guo and Zhiwen Yu; data curation, Wenwen Li and Yaxing Chen; writing—original draft preparation, Wenwen Li, Yaxing Chen and Qianyue Fan; writing—review and editing, Yaxing Chen, Meng Yang, Bin Guo and Zhiwen Yu; visualization, Wenwen Li; supervision, Yaxing Chen, Bin Guo and Zhiwen Yu; project administration, Yaxing Chen; funding acquisition, Yaxing Chen, Bing Guo and Zhiwen Yu. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant No. 62202379, The Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities under Grant No. G2022KY05102.

References

- Achlioptas, P.; Diamanti, O.; Mitliagkas, I.; Guibas, L. Learning Representations and Generative Models for 3D Point Clouds. 2018; arXiv:1707.02392. [Google Scholar]

- Gadelha, M.; Wang, R.; Maji, S. Multiresolution Tree Networks for 3D Point Cloud Processing. Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), 2018.

- Luo, S.; Hu, W. Diffusion Probabilistic Models for 3D Point Cloud Generation. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2021, pp. 2837–2845.

- Baldi, P. Autoencoders, Unsupervised Learning, and Deep Architectures. Proceedings of ICML Workshop on Unsupervised and Transfer Learning; Guyon, I., Dror, G., Lemaire, V., Taylor, G., Silver, D., Eds.; PMLR: Bellevue, Washington, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vakalopoulou, M.; Chassagnon, G.; Bus, N.; Marini, R.; Zacharaki, E.I.; Revel, M.P.; Paragios, N. AtlasNet: Multi-atlas Non-linear Deep Networks for Medical Image Segmentation. Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2018; Frangi, A.F., Schnabel, J.A., Davatzikos, C., Alberola-López, C., Fichtinger, G., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; pp. 658–666. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Q.; Yang, C.; Wei, H. Part-Wise AtlasNet for 3D point cloud reconstruction from a single image. Knowledge-Based Systems 2022, 242, 108395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groueix, T.; Fisher, M.; Kim, V.G.; Russell, B.C.; Aubry, M. A Papier-Mâché Approach to Learning 3D Surface Generation. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2018.

- Li, C.L.; Zaheer, M.; Zhang, Y.; Poczos, B.; Salakhutdinov, R. Point Cloud GAN. 2018; arXiv:1810.05795. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Li, X.; Fu, C.W.; Cohen-Or, D.; Heng, P.A. PU-GAN: A Point Cloud Upsampling Adversarial Network. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2019.

- Sarmad, M.; Lee, H.J.; Kim, Y.M. RL-GAN-Net: A Reinforcement Learning Agent Controlled GAN Network for Real-Time Point Cloud Shape Completion. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2019.

- Shu, D.W.; Park, S.W.; Kwon, J. 3D Point Cloud Generative Adversarial Network Based on Tree Structured Graph Convolutions. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2019.

- Li, X.; He, H.; Li, X.; Li, D.; Cheng, G.; Shi, J.; Weng, L.; Tong, Y.; Lin, Z. PointFlow: Flowing Semantics Through Points for Aerial Image Segmentation. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2021, pp. 4217–4226.

- Wei, Y.; Vosselman, G.; Yang, M.Y. Flow-based GAN for 3D Point Cloud Generation from a Single Image. 2022; arXiv:2210.04072. [Google Scholar]

- Tomczak, J.; Welling, M. VAE with a VampPrior. Proceedings of the Twenty-First International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics; Storkey, A.; Perez-Cruz, F., Eds. PMLR, 2018, Vol. 84, Proceedings of Machine Learning Research, pp. 1214–1223.

- Tesema, K.W.; Hill, L.; Jones, M.W.; Ahmad, M.I.; Tam, G.K. Point Cloud Completion: A Survey. IEEE Transactions on Visualization and Computer Graphics 2023, pp. 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yang, M.; Zheng, N. G2-MonoDepth: A General Framework of Generalized Depth Inference From Monocular RGB+X Data. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2024, 46, 3753–3771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, Z.; Zhi, Z.; Han, T.; Chen, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, C.; Cheng, M.; Zhang, X.; Qin, N.; Ma, L. A Survey of Point Cloud Completion. IEEE Journal of Selected Topics in Applied Earth Observations and Remote Sensing 2024, 17, 5691–5711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.M.; Ilieş, H.T. Practical shape analysis and segmentation methods for point cloud models. Computer Aided Geometric Design 2018, 67, 97–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.; Yumer, E.; Yang, J.; Ceylan, D.; Hoiem, D. 3D-PRNN: Generating Shape Primitives With Recurrent Neural Networks. Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2017.

- Qi, C.R.; Su, H.; Mo, K.; Guibas, L.J. PointNet: Deep Learning on Point Sets for 3D Classification and Segmentation. Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), 2017.

- Qi, C.R.; Yi, L.; Su, H.; Guibas, L.J. PointNet++: Deep Hierarchical Feature Learning on Point Sets in a Metric Space. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; Guyon, I.; Luxburg, U.V.; Bengio, S.; Wallach, H.; Fergus, R.; Vishwanathan, S.; Garnett, R., Eds. Curran Associates, Inc., 2017, Vol. 30.

- Yu, X.; Rao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Lu, J.; Zhou, J. PoinTr: Diverse Point Cloud Completion With Geometry-Aware Transformers. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2021, pp. 12498–12507.

- Zhao, H.; Jiang, L.; Jia, J.; Torr, P.H.; Koltun, V. Point Transformer. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2021, pp. 16259–16268.

- Xie, H.; Yao, H.; Zhou, S.; Mao, J.; Zhang, S.; Sun, W. GRNet: Gridding Residual Network for Dense Point Cloud Completion. Computer Vision – ECCV 2020; Vedaldi, A., Bischof, H., Brox, T., Frahm, J.M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2020; pp. 365–381. [Google Scholar]

- Zagoruyko, S.; Komodakis, N. Wide Residual Networks. 2017; arXiv:1605.07146. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Xu, J.; Zou, Y.; Liu, P.X.; Liu, J. PS-Net: Point Shift Network for 3-D Point Cloud Completion. IEEE Transactions on Geoscience and Remote Sensing 2022, 60, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Xiang, P.; Han, Z.; Cao, Y.P.; Wan, P.; Zheng, W.; Liu, Y.S. PMP-Net++: Point Cloud Completion by Transformer-Enhanced Multi-Step Point Moving Paths. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence 2023, 45, 852–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G.; Huang, X.; Hao, Z.; Liu, M.; Belongie, S.J.; Hariharan, B. PointFlow: 3D Point Cloud Generation with Continuous Normalizing Flows. CoRR. 2019; arXiv:1906.12320. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G.; Huang, X.; Hao, Z.; Liu, M.Y.; Belongie, S.; Hariharan, B. PointFlow: 3D Point Cloud Generation With Continuous Normalizing Flows. Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), 2019.

- Targ, S.; Almeida, D.; Lyman, K. Resnet in Resnet: Generalizing Residual Architectures. 2016; arXiv:1603.08029. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).