1. Introduction

The rapid expansion of construction in urban areas has profound implications for the environment, economy, public health, and overall well-being of cities [1]. In the European Union (EU), buildings account for 40% of energy consumption and 36% of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [2]. Alarmingly, approximately 15% of the EU population resides in inadequate housing conditions. Factors such as rising energy prices, low incomes, insufficient insulation, poor air quality, and overcrowded living spaces have contributed to increased rates of energy poverty, adversely affecting the quality of life for many individuals.

Over the past decade, electricity prices in the EU have surged, and this trend, coupled with the recent economic and financial crises and the inadequate energy efficiency of the existing housing stock, has heightened concerns regarding energy poverty, which currently affects around 54 million Europeans [3]. Energy poverty is defined as a condition in which a household cannot afford essential energy services necessary for maintaining a decent standard of living, resulting from a combination of low-income, high-energy costs, and poor energy efficiency in their homes [4]. Furthermore, many dwellings in the EU need to provide adequate thermal comfort due to various issues, including lack of insulation, substandard windows, thermal leaks in building structures, excessive air infiltration, and poorly maintained heating systems.

Conversely, advancements in medicine have led to increased life expectancy globally; between 2020 and 2021, the population of Europeans aged 80 and older nearly doubled [5]. By 2050, 16% of the global population is projected to be over 65 years old. This demographic shift has far-reaching implications for all sectors of society, including architecture, urban planning, and related services. Additionally, it presents challenges in intergenerational relations, where the accumulated experience of older generations can foster positive outcomes and create collaborative environments that minimize impacts on users and public spending [6].

The construction sector presents a unique opportunity to foster a transformative shift in urban culture, emphasizing the regeneration and resilience of the existing housing stock in response to the challenges posed by urban growth and sprawl associated with new developments. By promoting urban interventions that extend the lifespan of buildings and facilitate sustainable rehabilitation [7], it is essential to incorporate considerations of active ageing from the design phase of projects. The anticipated lifespan of a building significantly influences its functional utility, which is directly linked to the initial investment of resources allocated for its construction. Extending the useful life of a building can yield substantial environmental benefits. However, the actual lifespan may conclude earlier than its intended design life, often due to market dynamics contributing to obsolescence, such as evolving user needs and demands [8]. This underscores the necessity of addressing future flexibility and adaptability to changing requirements during the design process.

Adopting this strategic approach will enable the construction sector to align with the commitments outlined in the 2030 Urban Agenda [9], the European Green Deal [2], the European New Bauhaus [10], and the principles of the circular economy, which have emerged as pivotal policies for developing more efficient resource conservation strategies [11]. In response to these challenges, Level(s) has been established as a common EU framework comprising core indicators for assessing the sustainability of residential and office buildings. This framework can be applied from the earliest stages of conceptual design to the planned end-of-life phase of a building. Beyond its primary focus on environmental performance, Level(s) also facilitates the evaluation of other critical performance-related aspects through indicators and tools that address health and well-being, life-cycle costs, and potential future performance risks [7]. Notably, Indicator 2.3, which focuses on design for adaptability and renovation, proposes a process that aids in designing and renovating currently obsolete housing, thereby maximizing resilience to climatic, functional, and socio-economic challenges. Additionally, Indicator 4.2 measures the duration during which building occupants experience thermal comfort and assesses a building's ability to maintain predefined thermal comfort specifications during hot and cold weather [12,13].

Consequently, this research seeks to establish a resilient housing rehabilitation methodology grounded in the Level(s) framework. To achieve the objectives of this study, the following methodology has been outlined (see

Figure 1): (i) assessment of the current resilience of the pilot case using Level(s); (ii) design of innovative, resilient housing configurations, along with an analysis of project opportunities and constraints informed by Level(s); (iii) evaluation of the duration spent outside the thermal comfort range for older adults; and (iv) analysis of cost amortization.

The findings of this research will facilitate the development of a comprehensive, functional, flexible, accessible, resilient, and dynamic refurbishment model. This model, which is the result of a comprehensive and thorough research process, aims to accommodate the maximum number of configurations for a diverse range of tenants over time while considering factors such as thermal comfort, cost efficiency, duration, and return on investment. Furthermore, by analyzing the metabolic energy index in older adults, the research will enable a more tailored adaptation of solutions and a reassessment of comfort standards that consider the specific needs of older or vulnerable populations.

2. Materials and Methods

To achieve the objectives of this research, the following methodology has been established: (i) assessment of the current resilience of the pilot case using Level(s); (ii) design of innovative, resilient housing configurations, along with an analysis of project opportunities and constraints based on Level(s); (iii) evaluation of the time spent outside the thermal comfort range for older adults; and (iv) assessment of cost amortization.

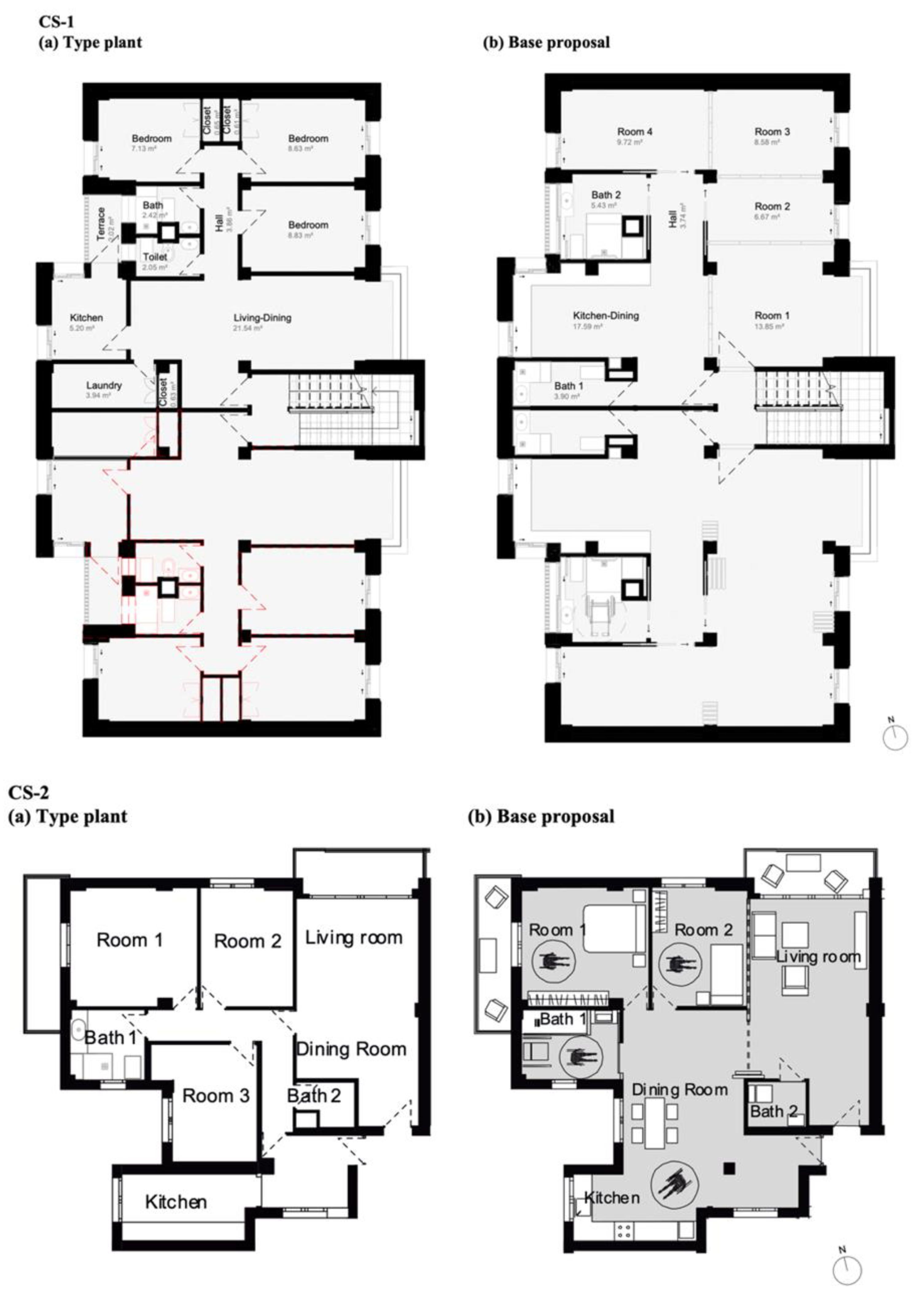

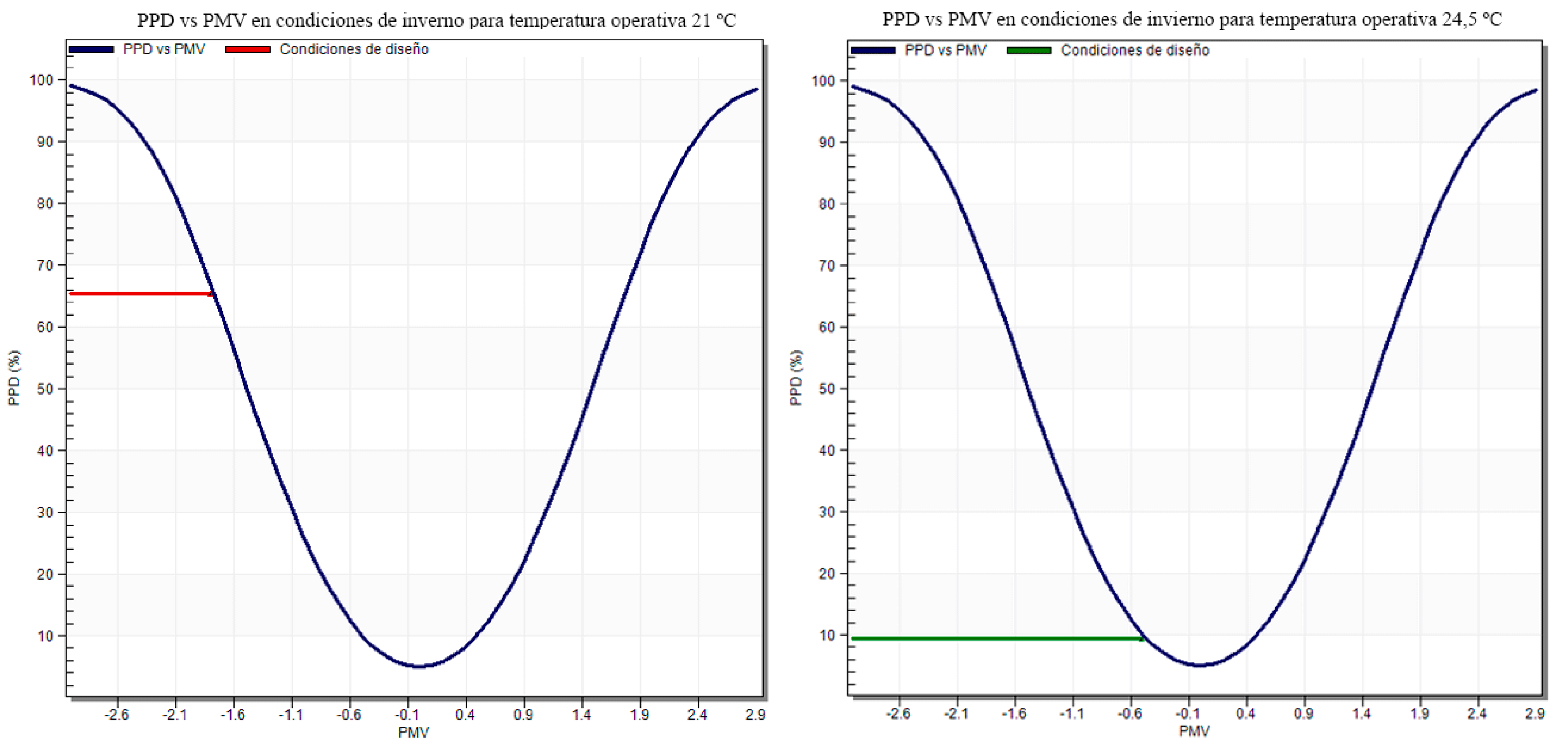

The first case study (CS-1) (see

Figure 1) focuses on a dwelling in a building within the Barriada Juan XXIII in Seville, constructed between the 1950s and 1980s. This area has experienced various socio-urban dynamics and exhibits varying degrees of marginalization from its origins as social housing. The specific dwelling under analysis is in a residential building erected in 1967. This double-aisled structure features two ground-floor flats, a ground floor, and four additional floors. The ground floor includes a communal space with storage rooms, access to various building services, and garden areas maintained by the residents. The dwellings are symmetrically configured around a central communication nucleus and offer a generous living space of 68 m².

The second case study (CS-2) (see

Figure 1) examines a dwelling in a 1970 residential and office building in Malaga's Gamarra neighbourhood. This building boasts 17 floors and encompasses a total area of 97 m², featuring a common area, offices on the first floor, and residential units on the upper levels.

2.1. Assessment of the Current Resilience of the Pilot Case Using Level(s)

The initial phase of the methodology involves a thorough analysis of the current state of the pilot case, utilizing indicator 2.3 from the Level(s) framework (see

Table 1). This indicator provides a structured approach to evaluate the opportunities and constraints associated with the housing refurbishment project. By applying these criteria, we aim to identify a comprehensive refurbishment strategy that maximizes the adaptability of the space, ensuring it can accommodate a diverse range of configurations for the most significant number of tenants over time.

2.2. Design of New Resilient Housing Configurations and Analysis of Project Opportunities and Constraints Based on Level(s)

In the second phase of our methodology, guided by Indicator 2.3, we focus on identifying the most appropriate housing configurations tailored to tenants' diverse needs and living arrangements. We explore various cohabitation models, categorized by the number of residents, their relationships' nature, and the dwelling's intended use.

We propose a Basic Refurbishment Plan for the case study to maximize the building's lifespan and accommodate a wide range of tenant types. This plan is designed to allow for flexible spatial configurations that can adapt over time. The Basic Refurbishment Proposal is grounded in the following principles, aligned with the criteria outlined in Indicator 2.3:

(a) Accessibility: Ensure that access points and internal passages are appropriately sized and adapt the bathroom to accommodate wheelchair users in compliance with European regulations.

(b) Flexibility: Incorporating movable panels that enable tenants to adjust the living space according to their specific needs, whether expanding or reducing the area.

(c) Independence: Adding a second bathroom and an additional entrance to the dwelling, allowing for greater privacy and autonomy for different tenant arrangements.

(d) Economy of Means and Materials: Striking for maximum resilience while minimizing investment ensures that the refurbishment is both cost-effective and sustainable.

This comprehensive approach aims to create resilient housing configurations that can evolve with tenants' changing needs over time.

2.3. Assessment of Time Outside of Thermal Comfort Range for Elderly People

The third phase of our methodology focuses on applying Indicator 4.2, which evaluates the proportion of time throughout the year that occupants experience comfortable indoor thermal conditions. This indicator explicitly measures the percentage of time indoor temperatures fall outside the established comfort range. While the primary emphasis is on ensuring thermal comfort during the summer, assessing how well residents can maintain warmth in their homes during winter is equally important.

When analysing this indicator, we adhere to the Level(s) framework requirements. For buildings equipped with mechanical HVAC systems, it is crucial to evaluate the performance of the building envelope when the HVAC system is not in operation. This assessment aims to determine the inherent thermal resilience of the building envelope. The performance metrics are derived from dynamic energy simulations, following the methodology outlined in Annex A.2 of EN 16798-1.

For our thermal comfort calculations, we utilize DesignBuilder Software, version 5.5.2.007 and the CBE Thermal Comfort Tool (an online resource for thermal comfort calculations and visualizations, SoftwareX 12, version 2.4.7). The thermal comfort criteria are based on the standards outlined in EN 16798, which utilize the PMV (Predicted Mean Vote) and PPD (Predicted Percentage Dissatisfied) calculations developed by Fanger. His research, grounded in empirical studies of skin temperature, provides a framework for defining comfort levels.

PMV (Predicted Mean Vote): This metric assesses hygrothermal comfort by asking participants to rate their thermal sensation on a seven-point scale, ranging from cold (-3) to hot (+3). The Fanger equations are employed to estimate the mean vote of a diverse group of individuals based on various factors, including air temperature, mean radiant temperature, relative humidity, air velocity, metabolic rate, and clothing.

PPD (Predicted Percentage Dissatisfied): This parameter estimates the percentage of individuals likely to experience discomfort based on the comfort conditions defined by the PMV.

By thoroughly assessing these factors, we aim to ensure that elderly residents can enjoy a comfortable living environment year-round and minimize the time spent outside their thermal comfort range.

2.3.1. Determining Thermal Comfort for the Elderly

Research indicates that the thermal comfort zone for seated or quiet adults, typically between 20°C and 24°C, is inadequate for older adults, who generally prefer a higher comfort temperature than the normotype [16]. Several studies [17] have estimated that the optimal thermal comfort range for older individuals lies between 24°C and 32°C [18]. As people age, their metabolism slows down, physical activity becomes more sedentary, and muscle mass decreases, significantly reducing the energy metabolic rate, ranging from 37 W/m² to 40 W/m² [17]. Based on this data, an energy metabolic rate of approximately 0.7 met has been established for older adults (compared to 1.0 met for quiet adult men and 0.85 met for quiet adult women), where 1 met equals 58.2 W/m².

2.3.2. Simulations and Calculation of Time Outside the Thermal Comfort Range for the City of Málaga

Once the metabolic rate parameters for older adults have been established and the climate file (EPW) [19] has been obtained from the EnergyPlus database [20], we can calculate the metabolic rate parameters specific to the elderly population in Málaga. The specified tools are used to simulate and calculate the time spent outside the comfort range.

Thermal comfort is analyzed through simulations using DesignBuilder [21] with the EnergyPlus engine. Several scenarios were simulated (including different types of dwellings, with and without HVAC systems, and various orientations), resulting in operative indoor temperatures for each situation. The CBE Thermal Comfort Tool [22] was also employed to establish appropriate thermal comfort ranges for the target population profile. For this purpose, the metabolic energy index of older adults was input into the tool.

2.4. Assessment of Cost Amortization

Finally, the costs and benefits derived from the Base Proposal are quantified, identifying construction and material costs and rental benefits across different configurations based on Level(s) Indicator 6.1 (

Table 1).

3. Results

The following sections present and discuss the results obtained from applying the methodology.

3.1. Resilience Assessment of the Current State of the Pilot Cases Using Level(s)

This section analyses CS-1 and CS-2 using Level(s) indicator 2.3.

CS-1 (see

Figure 1 and

Table 2) features a layout on the third level with a northeast-southwest orientation, where the south façade remains completely opaque. This compact dwelling comprises a kitchen, dining room, living room, bathroom, toilet, laundry room, and three bedrooms. According to user feedback, it has undergone significant modifications over time. However, there are notable deficiencies in the flexibility of the space due to the building's structural rigidity and accessibility issues within the communication core and the individual units. Additionally, the limited space, shallow ceilings, and minimal usable surface area hinder the possibility of implementing substantial improvements to the building's facilities. Given these constraints, which are influenced by the tenants' lifestyle and needs, a comprehensive refurbishment is proposed to address the residents' current and future demands in this social neighbourhood.

CS-2 (refer to

Figure 1 and

Table 2) is situated on the eighth floor and has a southeast orientation, characterized by a distinct division of its spaces. This more generously sized dwelling features a kitchen-dining room, living room, two bathrooms, a laundry room, and three bedrooms. User data indicates that it has experienced minimal modifications over time. However, the pronounced separation of spaces leads to functional issues; for instance, the dining room is located a considerable distance from the kitchen, often resulting in it being repurposed for other uses. The length of the layout suggests that the space could be utilized more effectively. Nevertheless, the house boasts excellent spatial potential, thanks to its ample dimensions, two independent entrances, and two balconies.

3.2. Design of New Resilient Housing Configurations and Analysis of Project Opportunities and Constraints Based on Level(s)

This section presents the Base Proposal (BP) and possible configurations for each case study (CS). In both CSs, the BP aims to optimize the intervention as much as possible, promoting space flexibility and efficient use. Areas such as the living room, study, and bedrooms are transformed into dynamic spaces that offer a wealth of creative possibilities and greater versatility in their utilization.

Each of the three configurations offers different rental possibilities, adapting to the needs of both the owner and the tenant. What's particularly exciting is that in all configurations, the home can be used solely for residential purposes by a family unit or as a combined living and workspace for the owner or tenant, showcasing the innovative and dual-purpose nature of the design.

3.2.1. Resilient CS-1 Configurations

Regarding CS-1, as illustrated in

Figure 2, the preliminary proposal aims to optimize the intervention to enhance flexibility and maximize the use of space. Areas such as the living room, study, and bedrooms are designed to be adaptable and versatile.

Configuration 1 (Figure 3): This layout features two independent rooms with movable partitions that can serve as a bedroom or a study. It accommodates 3 to 4 users, with easy access to shared areas and the main bedroom. Potential users include:

- Families consisting of 1 to 3 members, where the two independent rooms can function as bedrooms or studios.

- Families caring for a dependent individual, allowing the dependent person and their caregiver to share common spaces while maintaining the privacy of their bedrooms and bathrooms.

Configuration 2 (Figure 3): In this setup, two independent rooms can be utilized as a bedroom, study, or office, featuring movable partitions. This configuration supports 3 to 4 occupants. The common areas of the dwelling are oriented to the northwest, providing flexibility in whether the living room can be privatized. The main bedroom and study are easily accessible, facilitating movement between the kitchen-dining area and the living room. Possible users over time could include:

- A family unit of 1 to 2 members with a studio or office.

- A family unit of 1 to 2 members may choose to rent part of the dwelling, with a 14 m² studio with a separate bathroom.

Configuration 3 (Figure 3): This arrangement also consists of two independent rooms with movable partitions that can be adapted as a bedroom, study, or office. It accommodates 2 to 3 users, maximizing the privacy of each room by eliminating the living room and minimizing shared space to the kitchen-dining area. Potential users might include:

- An individual who conducts their trade within the dwelling.

- An individual who rents out a portion of their home, such as a studio with an independent bathroom.

3.2.2. Resilient Configurations of CS-2

Configuration 1 (Figure 3): This layout features two rooms and a separate living area with movable partition walls, accommodating 3 to 4 users. Potential users may include:

- Families forming a unit of 2 to 4 members.

- Families caring for a dependent individual, where the dependent and caregiver share a close relationship and common spaces.

Configuration 2 (Figure 3): This configuration includes two rooms and a separate office area with movable partitions, allowing for renting one of the spaces. Potential users could be:

- Families forming a unit of 1 to 3 members and an office suitable for one or two workers.

- Families caring for a dependent individual, where the dependent and caregiver maintain a close relationship and share common areas, and having an office for one or two workers.

- Rental of part of the dwelling, measuring 12.80 m².

Configuration 3 (Figure 3): The third proposal offers to rent a studio apartment independent of the main dwelling. Two independent living spaces can be created by closing one section of the panels and opening another. Potential users over time may include:

- Families forming a unit of 1 or 2 members, with an additional studio that can accommodate one or two individuals.

- Families caring for a dependent individual, where the dependent and caregiver share a close relationship, common spaces, and a studio that can accommodate one or two individuals.

- Rental of part of the dwelling, measuring 23.60 m².

3.3. Assessment of Time Outside the Thermal Comfort Range for Elderly Individuals

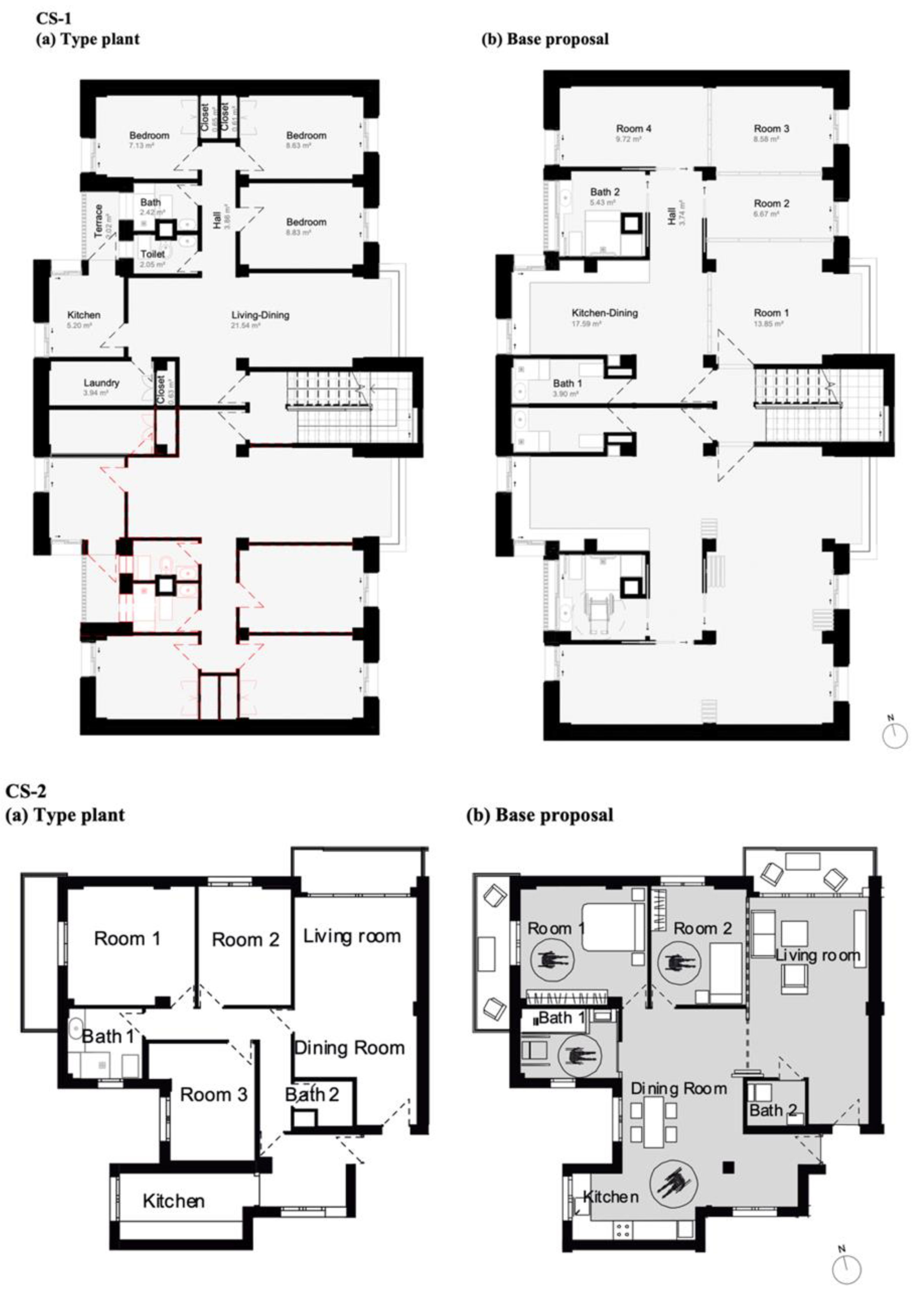

This section provides a comprehensive analysis of the simulation and calculation results aimed at evaluating the thermal comfort zone for elderly individuals and predicting the duration of time spent outside this comfort range in the specific case study.

Figure 4 illustrates the comfort range graph generated by the CBE Thermal Comfort Tool, which is based on a metabolic energy index of 0.7 met. This index is particularly relevant for elderly or vulnerable populations, considering Malaga's specific climatic conditions. The resulting comfort range is identified as being between 24.5ºC and 32ºC.

However, it is important to note that the findings from the simulation indicate that this comfort range does not align with the EN-16798 standard. The EN-16798 standard specifies a minimum metabolic rate of 0.8 met, which needs to be adequately covered by the current comfort range derived from the simulation. This discrepancy highlights a significant concern regarding the thermal comfort of elderly individuals in Malaga, as the established range may not provide sufficient comfort or safety for this demographic.

In conclusion, the assessment underscores the necessity for further investigation and potential adjustments to the thermal comfort parameters to ensure they meet the standards required for the well-being of elderly populations. Addressing these gaps is crucial for enhancing vulnerable groups' living conditions and overall health in varying climatic contexts.

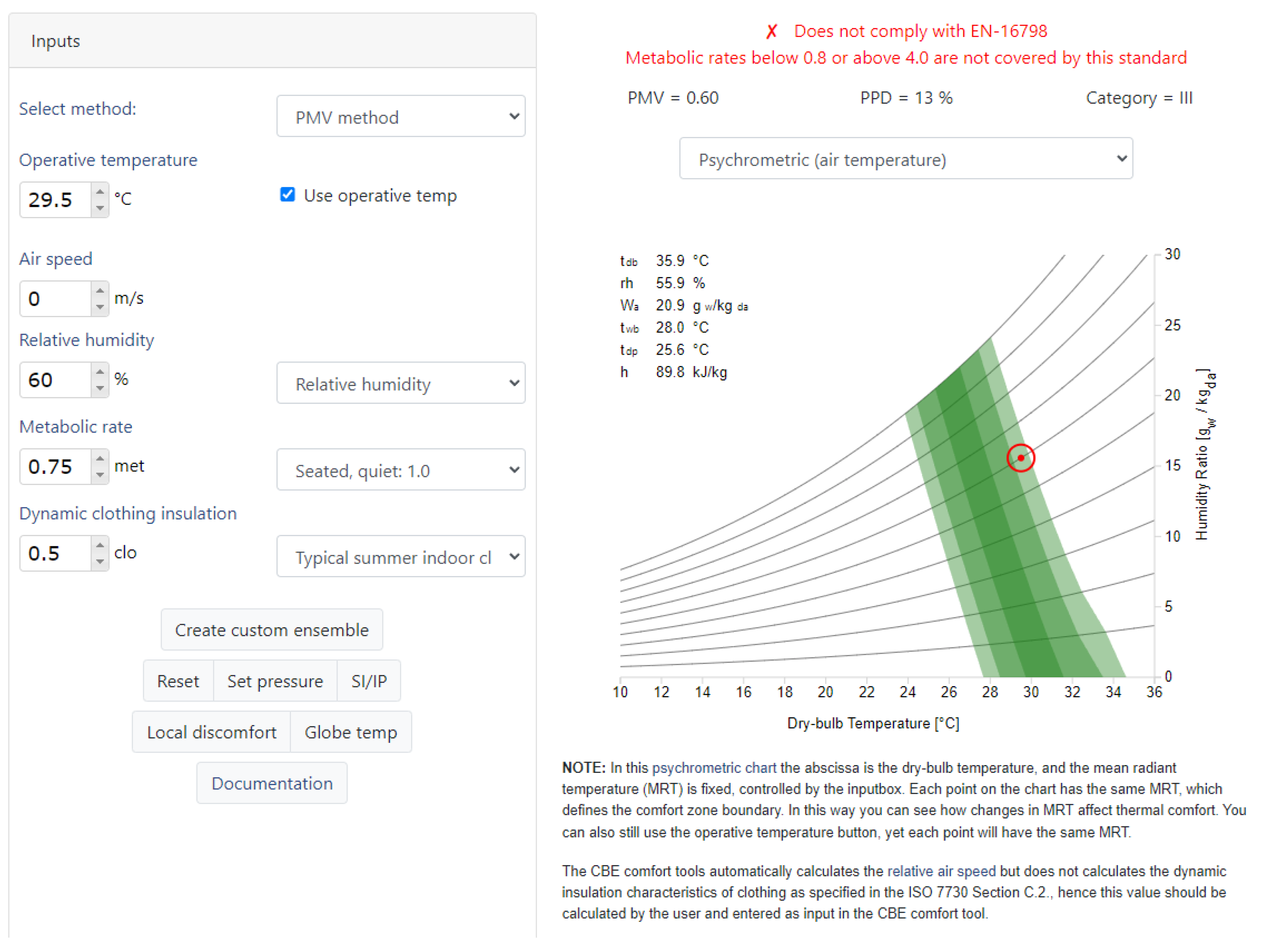

An analysis was conducted to evaluate a winter scenario in which the dwelling was heated according to the heating setpoints outlined in the Spanish Technical Building Code (2019). This analysis was compared to a setpoint temperature derived from the previously established comfort range.

Figure 5 illustrates the predicted percentage of discomfort experienced by occupants at two distinct heating setpoints: 21ºC, the maximum permitted by the Spanish Technical Building Code, and 24.5ºC, the minimum within the identified comfort range.

The findings reveal a significant disparity in occupant comfort levels at these two temperatures. Specifically, 73% of individuals reported experiencing discomfort at the 21ºC setpoint. In contrast, only 9.5% of individuals reported discomfort when the temperature was set to 24.5ºC.

These results underscore the importance of aligning heating practices with comfort standards, particularly for vulnerable populations such as the elderly. The data suggests that adhering to the higher comfort setpoint not only enhances the overall well-being of residents but also significantly reduces the percentage of individuals who experience discomfort during the winter months. This analysis highlights the need to reevaluate current heating regulations to accommodate the thermal comfort requirements of occupants better, ultimately promoting healthier living environments.

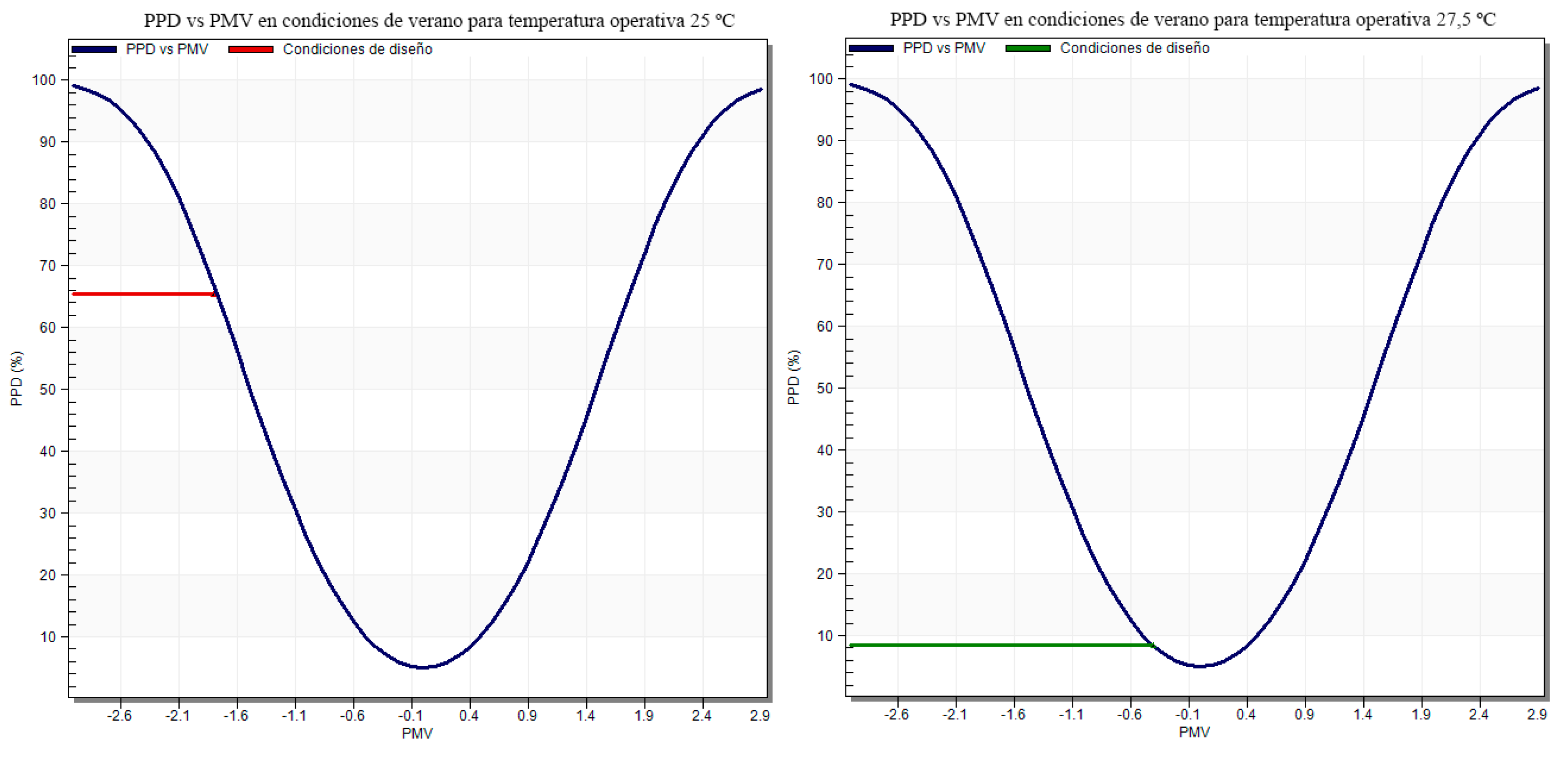

A comparable analysis was conducted for a summer scenario, focusing on the cooling setpoint temperatures as a benchmark for occupant comfort.

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 present the predicted percentage of discomfort experienced by individuals at two specific cooling setpoints: 25ºC, the minimum temperature mandated by the Spanish Technical Building Code, and 27.5ºC, which falls within a more comfortable range.

This analysis reveals a significant difference in discomfort levels between the two temperatures. At the 25ºC setpoint, 65.5% of individuals reported experiencing discomfort. This high percentage indicates that the minimum cooling temperature established by the code may not adequately address the thermal comfort needs of occupants during the hotter months. In contrast, when the cooling setpoint is raised to 27.5ºC, the predicted percentage of discomfort drops dramatically to just 8.5%.

These findings highlight the importance of optimizing cooling strategies to enhance occupant comfort in residential settings. The stark contrast in discomfort levels suggests that a higher cooling setpoint can lead to a more pleasant indoor environment, significantly reducing the number of individuals who feel uncomfortable during the summer heat.

This analysis emphasizes the need to reassess current cooling regulations and advocates for a more nuanced approach to temperature settings that prioritizes occupant well-being. By aligning cooling practices with comfort standards, we can create healthier and more enjoyable living spaces, particularly during the sweltering summer months.

3.4. Assessment of Cost Amortization

In this section, we comprehensively analyse the costs and benefits associated with the three resilient configurations. This analysis includes a detailed breakdown of the construction and material costs for the Base Proposals and the potential rental income generated from each configuration.

We have identified several key improvement measures to calculate the refurbishment costs accurately. These include the insufflation of a 4 cm rock wool air chamber, which enhances insulation, and installing double-glazed windows with specifications of 4-16-6, paired with Class 3 PVC frames. These upgrades are designed to improve significantly in energy efficiency and occupant comfort.

As illustrated in

Table 3, the payback period for Configurations 2 and 3 is estimated to be a maximum of four years. This estimation is based on the average rental price per square meter derived from local real estate databases. Such a relatively short payback period indicates that these configurations not only recoup their initial investment quickly but also offer a sustainable financial model for property owners.

Moreover, a long-term perspective on housing lifespan reveals numerous opportunities for extending the value of these properties. Property owners can expect a higher return on investment over time by investing in resilient configurations. Additionally, these improvements contribute to significant environmental benefits, such as reduced energy consumption and lower carbon emissions, aligning with broader sustainability goals.

In summary, the assessment of cost amortization for these resilient configurations underscores their financial viability and environmental advantages, making them attractive options for current and future housing developments.

4. Discussion

The resilience assessment of the pilot cases CS-1 and CS-2 reveals significant insights into their current conditions and adaptability. CS-1, with its compact layout and opaque south façade, faces challenges related to structural rigidity and limited flexibility. User feedback indicates that while modifications have been made over time, the inherent design constraints hinder the ability to meet evolving tenant needs. The proposal for a comprehensive refurbishment is essential to enhance the living conditions and adaptability of this dwelling, particularly in a social neighbourhood where residents may have diverse requirements.

In contrast, CS-2, located on the eighth floor, offers a more spacious layout but suffers from functional issues due to the separation of spaces. The distance between the kitchen and dining area must often be more utilized in the dining room. Despite these challenges, CS-2's ample dimensions and independent entrances present opportunities for better space utilization. The analysis highlights the importance of addressing structural and functional aspects to improve resilience in housing designs.

The proposed configurations for both case studies aim to optimize space and enhance flexibility. The Base Proposal (BP) emphasizes creating dynamic living areas that can adapt to various uses, catering to the needs of families or individuals who may require home office spaces. Each configuration presents unique rental possibilities, showcasing the innovative dual-purpose nature of the designs.

For CS-1, the configurations allow for independent rooms serving multiple functions, accommodating families of different sizes and needs. This adaptability is crucial in modern housing, where flexibility can significantly enhance the living experience. Similarly, CS-2's configurations offer options for families and individuals, including the potential for rental income, which can be particularly beneficial in urban settings.

The thermal comfort analysis for elderly individuals underscores a critical gap in current housing standards. The findings indicate that the comfort range established for Malaga does not align with the EN-16798 standard, raising concerns about the well-being of vulnerable populations. The significant discomfort reported at lower heating setpoints highlights the need to reevaluate heating practices, particularly for elderly residents who may be more sensitive to temperature fluctuations.

The results from both winter and summer scenarios emphasize the importance of aligning temperature settings with occupant comfort. By adopting higher setpoints

5. Conclusions

This research highlights the urgent need for resilient housing solutions in urban environments, particularly in the European Union, where a significant portion of the population lives in inadequate housing conditions. The findings underline the construction sector's critical role in addressing energy poverty, improving thermal comfort, and promoting sustainable living environments.

Resilience and adaptability: The evaluation of the pilot cases, CS-1 and CS-2, reveals that both homes face unique structural rigidity and spatial configuration challenges. The proposed comprehensive retrofit strategies aim to improve flexibility and adaptability, allowing these homes better to meet the changing needs of diverse tenant populations. By incorporating movable panels and additional facilities, the designs promote a more dynamic use of space, which is essential in modern housing.

Thermal comfort for vulnerable populations: The thermal comfort analysis, particularly for elderly residents, indicates a significant gap between current housing standards and the actual comfort needs of this demographic. The comfort range established for Malaga does not align with the EN-16798 standard, suggesting that many older people may experience discomfort due to inadequate heating and cooling practices. This finding emphasizes the need to re-evaluate thermal comfort parameters to ensure the well-being of vulnerable populations.

Economic feasibility: The cost-recovery assessment demonstrates that the proposed resilient configurations provide substantial environmental benefits and present a financially viable model for property owners. With relatively short payback periods for retrofit investments, these configurations can generate higher returns while contributing to reduced energy consumption and carbon emissions.

Policy alignment: The research aligns with broader EU commitments, including the Urban Agenda 2030 and the European Green Deal, which advocate for sustainable urban development practices. By integrating the Level(s) framework into design and retrofit processes, the construction sector can effectively contribute to achieving these policy goals.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Carmen Díaz-López, Cristina Alba Pérez-Rendon, Antonio Serrano-Jiménez and Ángela Barrios-Padura; Formal analysis, Carmen Díaz-López, Cristina Alba Pérez-Rendon, Antonio Serrano-Jiménez and Ángela Barrios-Padura; Funding acquisition, Carmen Díaz-López and Ángela Barrios-Padura; Investigation, Carmen Díaz-López, Cristina Alba Pérez-Rendon and Antonio Serrano-Jiménez; Methodology, Carmen Díaz-López, Antonio Serrano-Jiménez and Ángela Barrios-Padura; Project administration, Ángela Barrios-Padura; Resources, Antonio Serrano-Jiménez and Ángela Barrios-Padura; Software, Carmen Díaz-López and Cristina Alba Pérez-Rendon; Supervision, Carmen Díaz-López and Ángela Barrios-Padura; Validation, Carmen Díaz-López and Antonio Serrano-Jiménez; Visualization, Cristina Alba Pérez-Rendon; Writing – original draft, Carmen Díaz-López, Cristina Alba Pérez-Rendon, Antonio Serrano-Jiménez and Ángela Barrios-Padura; Writing – review & editing, Ángela Barrios-Padura. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Grant FJC2921-014411-I, funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and the European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR. It was conducted under the Juan de la Cierva postdoctoral contract awarded to Carmen Díaz-López at the University of Seville (contract reference US-23442-M). Additionally, this study is part of the I+D+I Project (PAIDI 2020) titled "Neighbourhood Cooperatives of Older People for Active Ageing in Place: Implications for Reducing Loneliness in Large Cities" (PY20_00411), funded by the Consejería de Transformación Económica, Industria, Conocimiento y Universidades of the Junta de Andalucía.

Institutional Review Board Statement

In this section, you should add the Institutional Review Board Statement and approval number, if relevant to your study. You might choose to exclude this statement if the study did not require ethical approval. Please note that the Editorial Office might ask you for further information. Please add “The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of NAME OF INSTITUTE (protocol code XXX and date of approval).” for studies involving humans. OR “The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of NAME OF INSTITUTE (protocol code XXX and date of approval).” for studies involving animals. OR “Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to REASON (please provide a detailed justification).” OR “Not applicable” for studies not involving humans or animals.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

We encourage all authors of articles published in MDPI journals to share their research data. In this section, please provide details regarding where data supporting reported results can be found, including links to publicly archived datasets analyzed or generated during the study. Where no new data were created, or where data is unavailable due to privacy or ethical restrictions, a statement is still required. Suggested Data Availability Statements are available in section “MDPI Research Data Policies” at

https://www.mdpi.com/ethics.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- A. Darko, A.P.C. Chan, E.E. Ameyaw, B.J. He, A.O. Olanipekun, Examining issues influencing green building technologies adoption: The United States green building experts’ perspectives. Energy Build 2017, 144, 320–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission, The European Green Deal, European Commission 2019, 53, 24. [CrossRef]

- Energy Poverty Advisory Hub (EPAH), A Guide to Energy Poverty Diagnosis, (2023).

- Gobierno de España, Estrategia nacional contra la pobreza energética, (2019).

- Eurostat, Una población envejecida, (2023). https://www.ine.es/prodyser/demografia_UE/bloc-1c.html?lang=es (accessed July 17, 2023).

- United Nations, World Population Prospects 2022 Data Sources, (2022). https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/. (accessed July 17, 2023).

- European Comission, Level(s), A common language for building assessment, Office des publications de l’Union européenne, 2021. [CrossRef]

- N. Dodd, S. Donatello, Indicador 2.3 de Level(s): Diseño con fines de adaptabilidad y reforma Manual del usuario: Información introductoria, instrucciones y orientaciones (versión 1.1), (2021). https://ec.europa.eu/jrc (accessed July 17, 2023).

- UN General Assembly, Transforming our world : the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, 2015. [CrossRef]

- E.C. President, M. E.C. President, M. Gabriel, New European Bauhaus : Commission launches design phase, (2021).

- Díaz-López, M. Carpio, M. Martín-Morales, M. Zamorano, Defining strategies to adopt Level(s) for bringing buildings into the circular economy. A case study of Spain. J Clean Prod 2021, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union, Level(s):Taking action on the total impact of the construction sector. (2019) 16. [CrossRef]

- N. Dodd, M. N. Dodd, M. Cordella, M. Traverso, S. Donatello, Level(s)-A common EU framework of core sustainability indicators for office and residential buildings Part 3: How to make performance assessments using Level(s) (Beta v1.0), in: 2017. [CrossRef]

- P. O. Fanger, Assessment of man’s thermal comfort in practice. Br J Ind Med 1973, 30, 313–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 16798-1:2019 - Energy performance of buildings - Ventilation for buildings - Part 1: Indoor, (n.d.). https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/b4f68755-2204-4796-854a-56643dfcfe89/en-16798-1-2019 (accessed May 14, 2024).

- W. Miller, D. Vine, Z. Amin, Energy efficiency of housing for older citizens: Does it matter? Energy Policy 2017, 101, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AMendes, A.; Bonassi, S.; Aguiar, L.; Pereira, C.; Neves, P.; Silva, S.; Mendes, D.; Guimarães, L.; Moroni, R.; Teixeira, J.P. Teixeira, Indoor air quality and thermal comfort in elderly care centers. Urban Climate 2015, 14, 486–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- J. L. White-Newsome, B.N. Sánchez, E.A. Parker, J.T. Dvonch, Z. Zhang, M.S. O’Neill, Assessing heat-adaptive behaviors among older, urban-dwelling adults. Maturitas 2011, 70, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- INSHT, Nota técnica de prevención - NTP 1011, (2014).

- U.S. Department of Energy’s, EnergyPlus, 2023. https://energyplus.net/ (accessed July 18, 2023).

- DESIGNBUILDER SOFTWARE LIMITED, DesignBuilder, simulaciones avanzadas de edificios, 2020. https://www.designbuilder-lat.com/ (accessed July 18, 2023).

- F. Tartarini, S. Schiavon, T. Cheung, T. Hoyt, CBE Thermal Comfort Tool: Online tool for thermal comfort calculations and visualizations. SoftwareX 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).