Submitted:

11 December 2024

Posted:

12 December 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

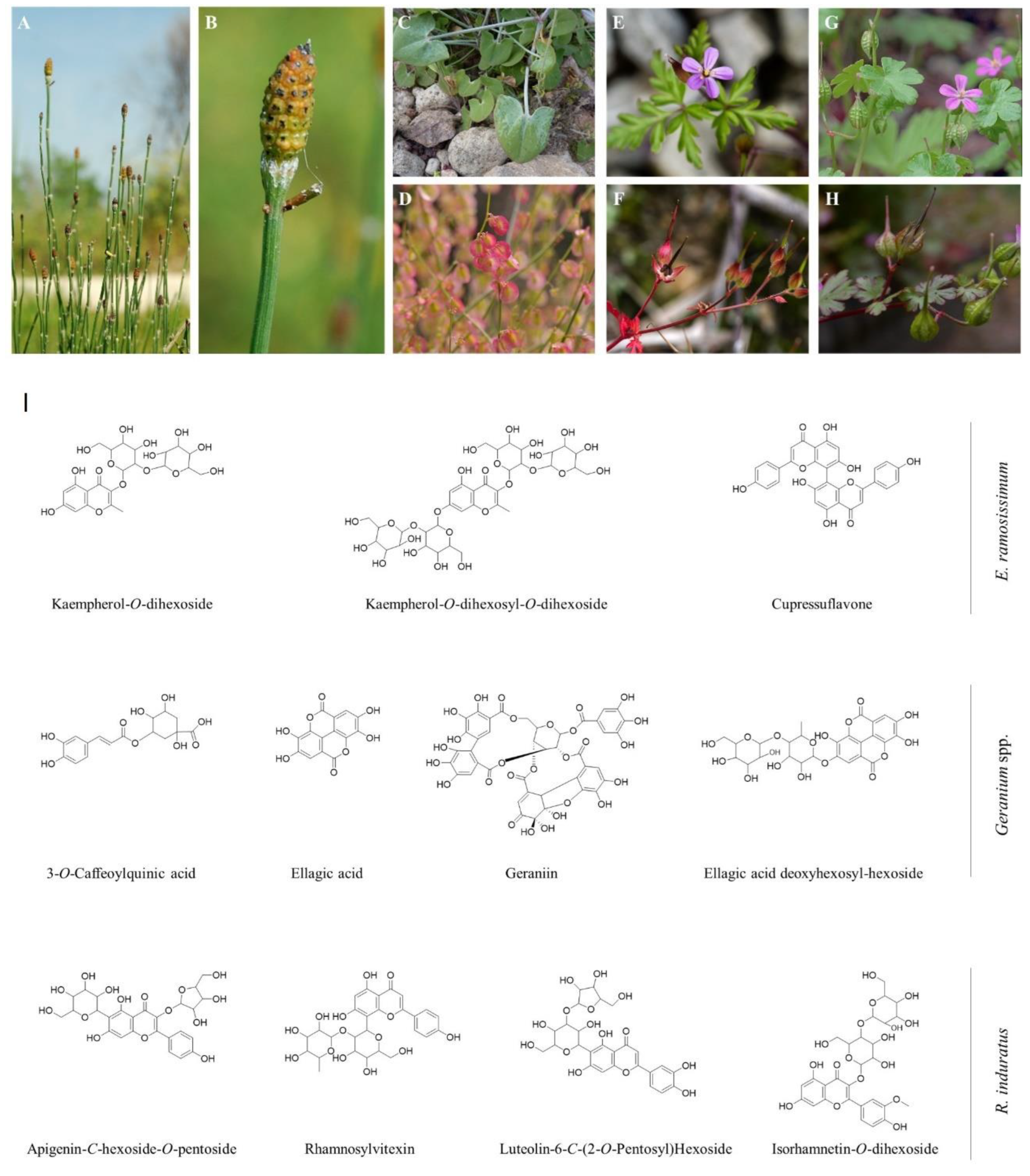

2.1. Extract Composition

2.1.1. Phenolic Acids

2.1.2. Ellagic acid derivatives

2.1.3. Flavonoids

- one O-glycosylation: luteolin-O-hexoside (peaks 18g/20g);

- two O-glycosylation: kaempferol-O-dihexoside (9e), isorhamnetin-O-dihexoside (16r/17r), isorhamnetin O-deoxyhexosyl-hexoside (peak 19g), and luteolin-O-deoxyhexosyl-hexoside (peaks 13g/17g);

- - three O-glycosylation: quercetin-O-dihexosyl-O-dihexoside (peak 3e) and kaempferol-O-dihexosyl-O-dihexoside (peaks 1e/2e/8e) [43];

- - an acetyl linkage with O-glycosylation: kaempherol-O-acetyl-dihexoside (peak 11e) and kaempherol-O-hexosyl-O-acetyl-dihexoside (peak 5e);

- - phenolic acids linkage with O-glycosylation: isorhamnetin-O-caffeoyl-O-deoxyhexosyl-dihexoside (peaks 3r/4r), luteolin galloyl O-deoxyhexosyl-hexoside (peak 21g), luteolin galloyl O-hexoside (peak 23g), quercetin galloyl O-deoxyhexosyl-hexoside (peak 15g), and quercetin galloyl O-hexoside (peak 16g) [44];

- - and C-glycosylation combined or not with O-glycosylation: apigenin 6-C-hexosyl-8-C-pentoside [peak 9r, [45]], apigenin-C-hexoside [peak 15r, [46]], apigenin-C-hexoside-O-pentoside [peaks 12r/13r, [46]], luteolin-6-C-(2-O-pentosyl)hexoside [peaks 10r/11r, [47]], rhamnosylvitexin [peak 2r, [48]] and cupressuflavone [peak 7e, [49]].

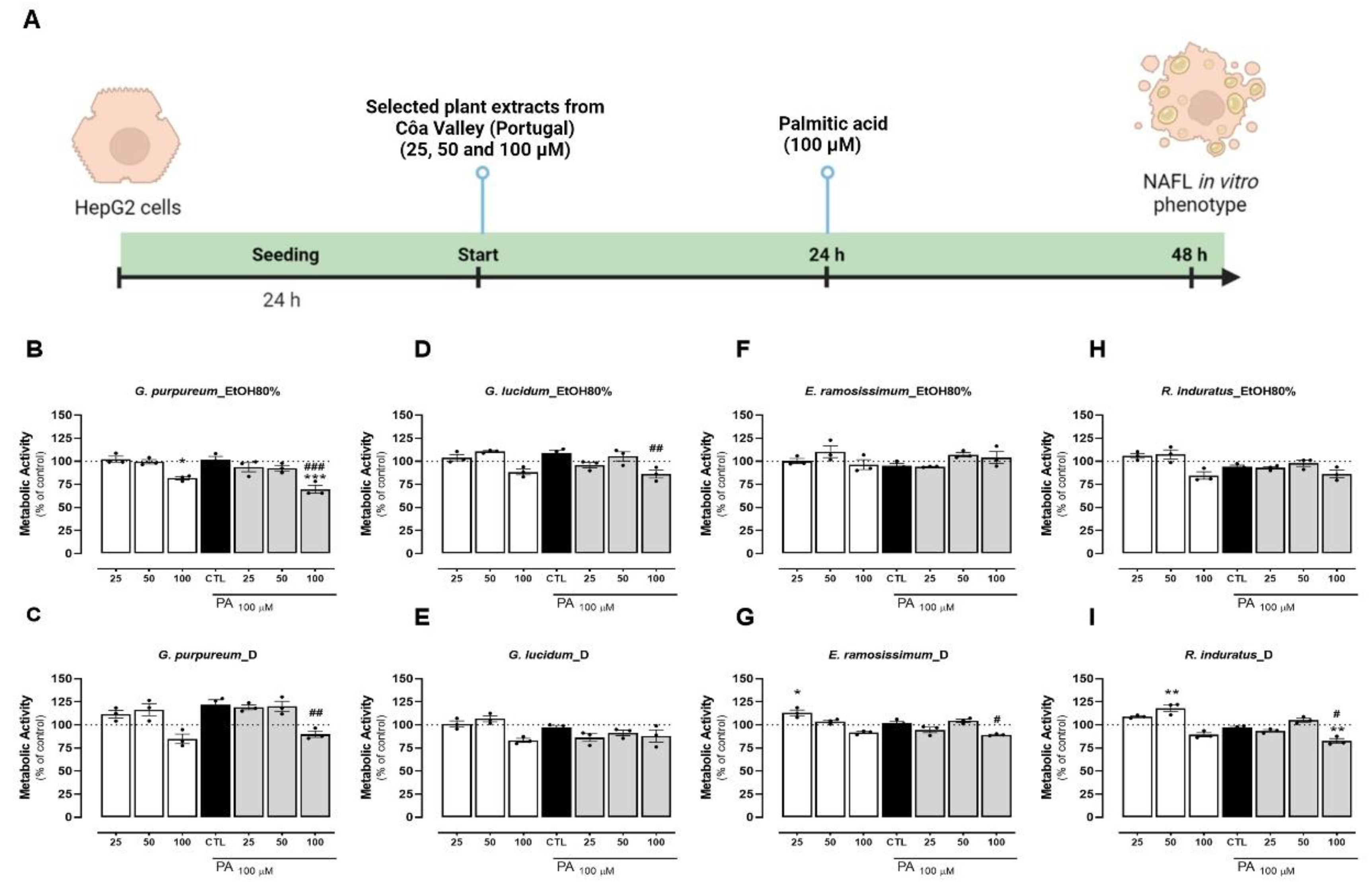

2.2. Effects of the different extracts on metabolic activity

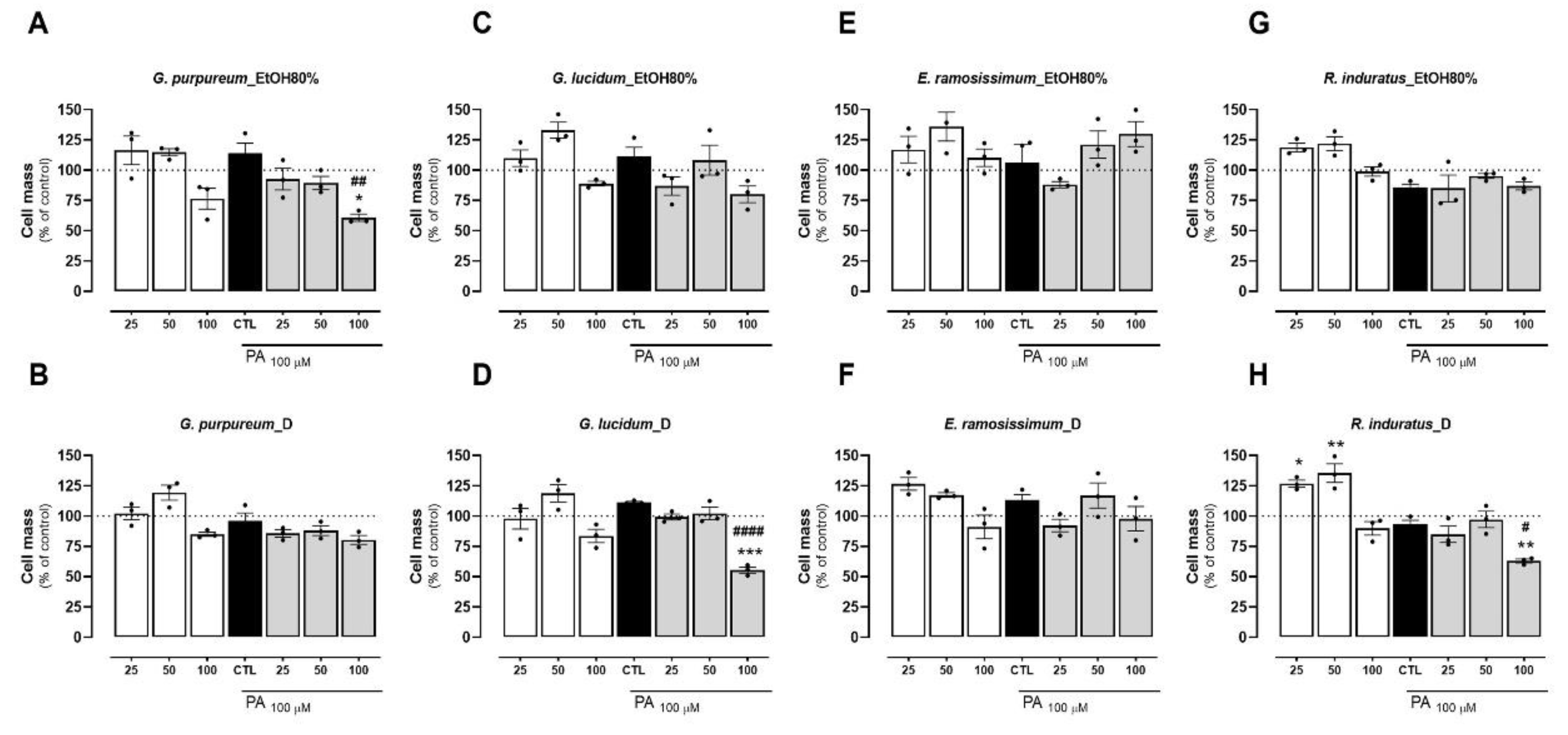

2.3. Effects of tested extracts on cell mass

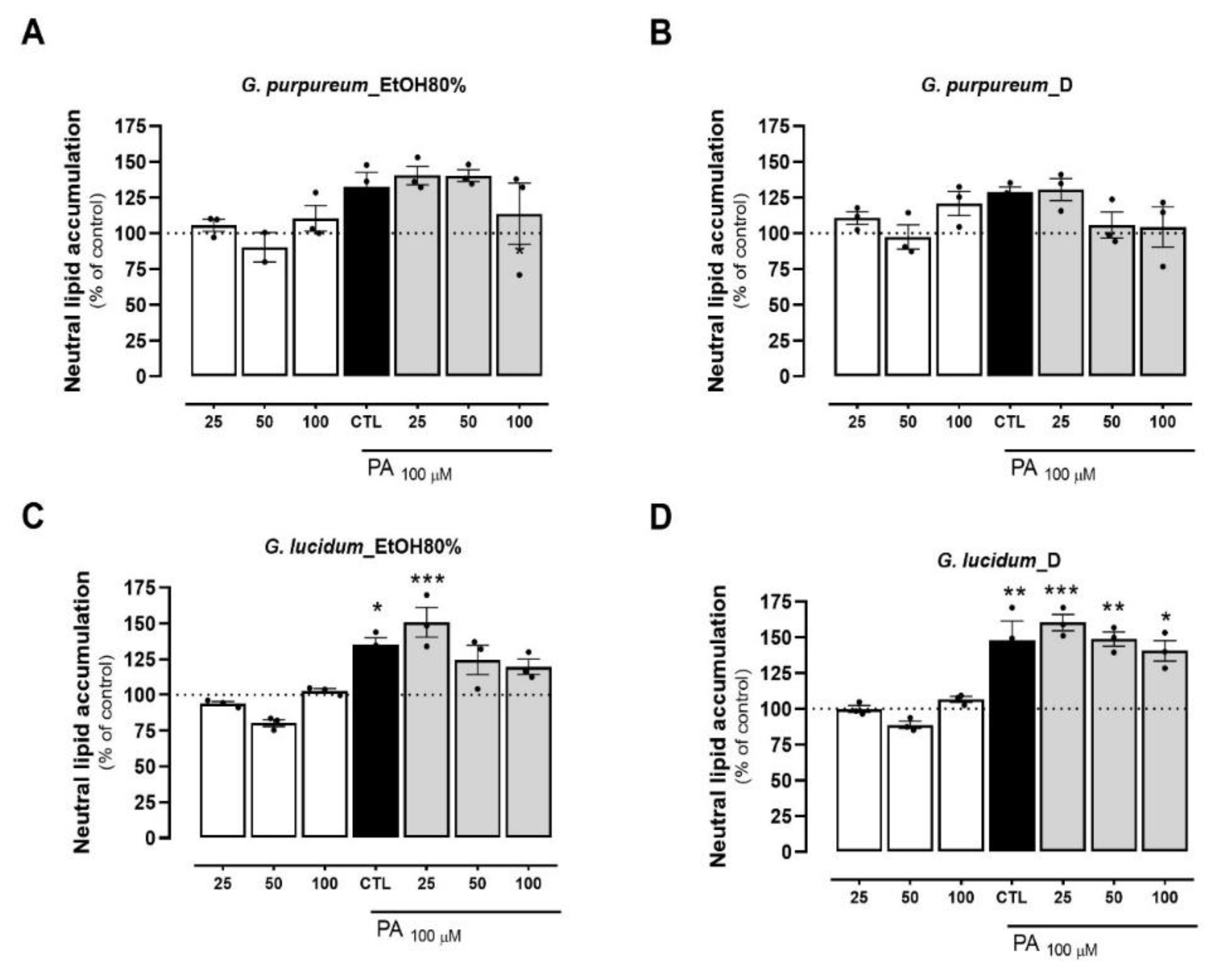

2.4. Effects of tested extracts on preventing PA-induced lipid accumulation in HepG2 cells

3. Materials and Methods.

3.1. Materials

3.2. Plant Material

3.3. Extraction procedures

3.3.1. Decoction extraction

3.3.2. Hydroalcoholic extraction

3.4. HPLC–DAD–ESI/MS analysis of hydroalcoholic and decoction extracts

3.5. Cell culture and extract treatment

3.6. Palmitic Acid/BSA Conjugation

3.7. Cell Metabolic Activity

3.8. Cell Mass

3.9. Nile Red Staining

3.10. Statistic Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- CoaParque webpage, 2023. https://arte-coa.pt/a-regiao-2/ (accessed 15th May 2024).

- Di Ferdinando, M., Brunetti, C., Agati, G., Tattini, M. Multiple functions of polyphenols in plants inhabiting unfavorable Mediterranean areas. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Yang, K., Chen, J., Zhang, T., Yuan, X., Ge, A., Wang, S., Xu, H., Zeng, L., Ge, J. Efficacy and safety of dietary polyphenol supplementation in the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. immunol. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C., Wang, X., Jiang, S., Zhou, M., Li, F., Bi, X., Xie, S., Liu, J. Heavy metal pollution caused by cyanide gold leaching: a case study of gold tailings in central China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ranđelović, D., Mihailović, N., Jovanović, S. Potential of Equisetum ramosissimum Desf. for remediation of antimony flotation tailings: a case study. Int. J. Phytoremediation. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Li, P.H., Chiu, Y.P., Shih, C.C., Wen, Z.H., Ibeto, L.K., Huang, S.H., Chiu, C. C., Ma, D. L., Leung, C. H., Chang, Y. N., Wang, H. M. D. Biofunctional Activities of Equisetum ramosissimum Extract: Protective Effects against Oxidation, Melanoma, and Melanogenesis. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Radulović, N.S., Stojković, M.B., Mitić, S.S., Randjelović, P.J., Ilić, I.R., Stojanović, N.M., Stojanović-Radić, Z.Z. Exploitation of the antioxidant potential of Geranium macrorrhizum (Geraniaceae): Hepatoprotective and antimicrobial activities. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Esfandani-Bozchaloyi, S., Zaman, W. Taxonomic significance of macro and micro-morphology of Geranium L. species Using Scanning Electron Microscopy. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Radulovic̈, N.S., Dekic̈, M.S. Volatiles of Geranium purpureum Vill. and Geranium phaeum L.: Chemotaxonomy of Balkan Geranium and Erodium species (Geraniaceae). Chem. Biodivers. 2013. [CrossRef]

- Nunes, R., Pasko, P., Tyszka-Czochara, M., Szewczyk, A., Szlosarczyk, M., Carvalho, I.S. Antibacterial, antioxidant and anti-proliferative properties and zinc content of five south Portugal herbs. Pharm. Biol. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Pinela, J., Morales, P., Cabo Verde, S., Antonio, A.L., Carvalho, A.M., Oliveira, M.B.P.P., Cámara, M., Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Stability of total folates/vitamin B9 in irradiated watercress and buckler sorrel during refrigerated storage. Food Chem. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Pinela, J., Barreira, J.C.M., Barros, L. Verde, S.C., Antonio A.L., Oliveira, M.B.P.P., Carvalho, A.M., Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Modified atmosphere packaging and post-packaging irradiation of Rumex induratus leaves: a comparative study of postharvest quality changes. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Ferreres, F., Ribeiro, V., Izquierdo, A.G., Rodrigues, M.Â., Seabra, R.M., Andrade, P.B., Valentão, P. Rumex induratus leaves: Interesting dietary source of potential bioactive compounds. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006. [CrossRef]

- Vasas, A., Orbán-Gyapai, O., Hohmann, J. The Genus Rumex: Review of traditional uses, phytochemistry and pharmacology. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Taveira, M., Guedes de Pinho, P., Gonçalves, R. F., Andrade, P. B., Valentão, P. Determination of eighty-one volatile organic compounds in dietary Rumex induratus leaves by GC/IT-MS, using different extractive techniques. Microchem. J. 2009. [CrossRef]

- Younossi, Z.M., Marchesini, G., Pinto-Cortez, H., Petta, S. Epidemiology of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease and Nonalcoholic Steatohepatitis: Implications for Liver Transplantation. Transplantation. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Amorim, R., Simões, I.C.M., Veloso, C., Carvalho, A., Simões, R.F., Pereira, F.B., Thiel, T., Normann, A., Morais, C., Jurado, A.S., Wieckowski, M.R., Teixeira, J., Oliveira, P.J. Exploratory data analysis of cell and mitochondrial high-fat, high-sugar toxicity on human HepG2 cells. Nutrients. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z., Tian, R., She, Z., Cai, J., Li, H. Role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Smirne, C., Croce, E., Benedetto, D. Di, Cantaluppi, V., Sainaghi, P.P., Minisini, R., Grossini, E., Pirisi, M., Comi, C. Oxidative Stress in Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Livers. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Hong, T., Chen, Y., Li, X., Lu, Y. The Role and Mechanism of Oxidative Stress and Nuclear Receptors in the Development of MASLD. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Amorim, R., Magalhães, C.C., Borges, F., Oliveira, P.J., Teixeira, J. From Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver to Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Story of (Mal)Adapted Mitochondria. Biology. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y., Lee, G., Heo, S.Y., Roh, Y.S. Oxidative stress is a key modulator in the development of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Antioxidants. 2022. [CrossRef]

- García-Ruiz, I., Solís-Muñoz, P., Fernández-Moreira, D., Muñoz-Yagüe, T., Solís-Herruzo, J.A. In vitro treatment of HepG2 cells with saturated fatty acids reproduces mitochondrial dysfunction found in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Dis. Model Mech. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Gabbia, D., Cannella, L., De Martin, S., Shiri-Sverdlov, R., Squadrito, G. The Role of Oxidative Stress in MASLD-NASH-HCC Transition-Focus on NADPH Oxidases. Biomedicines. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Abenavoli, L., Larussa, T., Corea, A., Procopio, A.C., Boccuto, L., Dallio, M., Federico, A., Luzza, F. Dietary Polyphenols and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Nutrients. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Li, S., Tan, H.Y., Wang, N., Cheung, F., Hong, M., Feng, Y. The Potential and Action Mechanism of Polyphenols in the Treatment of Liver Diseases. Oxid. Med.Cell. Longev. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Bayram, H.M., Majoo, F.M., Ozturkcan, A. Polyphenols in the prevention and treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: An update of preclinical and clinical studies. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Bessada, S. M. F., Barreira, J. C. M., Barros, L., Ferreira, I. C. F. R., Oliveira, M. B. P. P. Phenolic profile and antioxidant activity of Coleostephus myconis (L.) Rchb.f.: An underexploited and highly disseminated species. Industrial Crops and Products. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Amorim, R., Simões, I.C.M., Teixeira, J., Cagide, F., Potes, Y., Soares, P., Carvalho, A., Tavares, L.C., Benfeito, S., Pereira, S.P., Simões, R.F., Karkucinska-Wieckowska, A., Viegas, I., Szymanska, S., Dąbrowski, M., Janikiewicz, J., Cunha-Oliveira, T., Dobrzyń, A., Jones, J.G., Borges, F., Wieckowski, M.R., Oliveira, P. J. Mitochondria-targeted anti-oxidant AntiOxCIN4 improved liver steatosis in Western diet-fed mice by preventing lipid accumulation due to upregulation of fatty acid oxidation, quality control mechanism and antioxidant defense systems. Redox Biol. 2022a. [CrossRef]

- Amorim, R., Cagide, F., Tavares, L.C., Simões, R.F., Soares, P., Benfeito, S., Baldeiras, I., Jones, J.G., Borges, F., Oliveira, P.J., Teixeira, J. Mitochondriotropic antioxidant based on caffeic acid AntiOxCIN4 activates Nrf2-dependent antioxidant defenses and quality control mechanisms to antagonize oxidative stress-induced cell damage. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2022b. [CrossRef]

- Silva, F.S.G., Starostina, I.G., Ivanova, V.V., Rizvanov, A.A., Oliveira, P.J., Pereira, S.P. Determination of metabolic viability and cell mass using a tandem resazurin/sulforhodamine B assay. Curr. Protoc. Toxicol. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Vichai, V., Kirtikara, K. Sulforhodamine B colorimetric assay for cytotoxicity screening. Nat. Protoc. 2006. [CrossRef]

- McMillian, M.K., Grant, E.R., Zhong, Z., Parker, J.B., Li, L., Zivin, R.A., Burczynski, M.E., Johnson, M.D. Nile red binding to HepG2 cells: An improved assay for in vitro studies of hepatosteatosis. In Vitro and Molecular Toxicology: J. Basic Appl. Res. 2001. [CrossRef]

- Salomone, F., Ivancovsky-Wajcman, D., Fliss-Isakov, N., Webb, M., Grosso, G., Godos, J., Galvano, F., Shibolet, O., Kariv, R., & Zelber-Sagi, S. Higher phenolic acid intake independently associates with lower prevalence of insulin resistance and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. JHEP Rep. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Rashmi, H.B., Negi, P.S. Phenolic acids from vegetables: A review on processing stability and health benefits. Food Res. Int. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Graça, V.C., Barros, L., Calhelha, R.C., Dias, M.I., Ferreira, I.C.F.R., Santos, P.F. Bio-guided fractionation of extracts of Geranium robertianum L.: Relationship between phenolic profile and biological activity. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Graça, V.C., Dias, M.I., Barros, L., Calhelha, R.C., Santos, P.F., Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Fractionation of the more active extracts of: Geranium molle L.: A relationship between their phenolic profile and biological activity. Food Funct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- de Queiroz, L.N., Da Fonseca, A.C.C., Wermelinger, G.F., da Silva, D.P.D., Pascoal, A.C.R.F., Sawaya, A.C.H.F., de Almeida, E.C.P., do Amaral, B.S., de Lima Moreira, D., Robbs, B.K. New substances of Equisetum hyemale L. extracts and their in vivo antitumoral effect against oral squamous cell carcinoma. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, R., Sovdat, T., Vivan, F., Kuhnert, N. Profiling and characterization by LC-MSn of the chlorogenic acids and hydroxycinnamoylshikimate esters in maté (Ilex paraguariensis). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2010. [CrossRef]

- Graça, V.C., Barros, L., Calhelha, R.C., Dias, M.I., Carvalho, A.M., Santos-Buelga, C., Santos, P.F., Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Chemical characterization and bioactive properties of aqueous and organic extracts of Geranium robertianum L. Food Funct. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.S., Ton, S.H., Abdul Kadir, K. Ellagitannin geraniin: a review of the natural sources, biosynthesis, pharmacokinetics and biological effects. Phytochem. Rev. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Elendran, S., Muniyandy, S., Lee, W.W., Palanisamy, U.D. Permeability of the ellagitannin geraniin and its metabolites in a human colon adenocarcinoma Caco-2 cell culture model. Food Funct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Llorach, R., Gil-Izquierdo, A., Ferreres, F., Tomás-Barberán, F.A. HPLC-DAD-MS/MS ESI characterization of unusual highly glycosylated acylated flavonoids from cauliflower (Brassica oleracea L. var. botrytis) agroindustrial byproducts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003. [CrossRef]

- Mattera, M.G., Langenheim, M.E., Reiner, G., Peri, P.L., Moreno, D.A. Patagonian ñire (Nothofagus antarctica) combined with green tea - Novel beverage enriched in bioactive phytochemicals as health promoters. JSFA Rep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Truchado, P., Vit, P., Ferreres, F., Tomas-Barberan, F. Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis allows the simultaneous characterization of C-glycosyl and O-glycosyl flavonoids in stingless bee honeys. J. Chromatogr. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Llorent-Martinez, E.J., Spinola, V., Gouveia, S., Castilho, P.C. HPLC-ESI-MSn characterization of phenolic compounds, terpenoid saponins, and other minor compounds in Bituminaria bituminosa. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Ferreres, F., Gonçalves, R.F., Gil-Izquierdo, A., Valentão, P., Silva, A.M.S., Silva, J.B., Santos, D., Andrade, P.B. Further Knowledge on the Phenolic Profile of Colocasia esculenta (L.) Shott. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Dou, J., Lee, V.S.Y., Tzen, J.T.C., Lee, M.R. Identification and comparison of phenolic compounds in the preparation of oolong tea manufactured by semifermentation and drying processes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007. [CrossRef]

- Romani, A., Galardi, C., Pinelli, P., Mulinacci, N., Heimler, D. HPLC quantification of flavonoids and biflavonoids in Cupressaceae leaves. Chromatographia. 2002. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J., Muzashvili, T.S., Georgiev, M.I. Advances in the biotechnological glycosylation of valuable flavonoids. Biotechnol. Adv. 2014. [CrossRef]

- Hofer, B. Recent developments in the enzymatic O-glycosylation of flavonoids. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Vasudevan, U.M., Lee, E.Y. Flavonoids, terpenoids, and polyketide antibiotics: Role of glycosylation and biocatalytic tactics in engineering glycosylation. Biotechnol. Adv. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Sordon, S., Popłoński, J., Huszcza, E. Microbial glycosylation of flavonoids. Pol. J. Microbiol. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Busch, S.J., Barnhart, R.L., Martin, G.A., Flanagan, M.A., Jackson, R.L. Differential regulation of hepatic triglyceride lipase and 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA reductase gene expression in a human hepatoma cell line, HepG2. J. Biol. Chem. 1990. [CrossRef]

- Ramos, M.J., Bandiera, L., Menolascina, F., Fallowfield, J.A. In vitro models for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: Emerging platforms and their applications. IScience. 2022. [CrossRef]

- de Sousa, I.F., Migliaccio, V., Lepretti, M., Paolella, G., Di Gregorio, I., Caputo, I., Ribeiro, E.B., Lionetti, L. Dose-and time-dependent effects of oleate on mitochondrial fusion/fission proteins and cell viability in HepG2 cells: Comparison with palmitate effects. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Nissar, A.U., Sharma, L., Tasduq, S.A. Palmitic acid induced lipotoxicity is associated with altered lipid metabolism, enhanced CYP450 2E1 and intracellular calcium mediated ER stress in human hepatoma cells. Toxicol. Res. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Zang, Y., Fan, L., Chen, J., Huang, R., Qin, H. Improvement of Lipid and Glucose Metabolism by Capsiate in Palmitic Acid-Treated HepG2 Cells via Activation of the AMPK/SIRT1 Signaling Pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Sergazy, S., Vetrova, A., Orhan, I.E., Senol Deniz, F.S., Kahraman, A., Zhang, J.Y., Aljofan, M. Antiproliferative and cytotoxic activity of Geraniaceae plant extracts against five tumor cell lines. Future Sci. AO. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, H., Shao, M., Lu, Y., Wang, J., Wu, T., Ji, G. Kaempferol Alleviates Steatosis and Inflammation During Early Non-Alcoholic Steatohepatitis Associated With Liver X Receptor α-Lysophosphatidylcholine Acyltransferase 3 Signaling Pathway. Front. Pharmacol. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Alnahdi, A., John, A., Raza, H. Augmentation of Glucotoxicity, Oxidative Stress, Apoptosis and Mitochondrial Dysfunction in HepG2 Cells by Palmitic Acid. Nutrients. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Eynaudi, A., Díaz-Castro, F., Bórquez, J.C., Bravo-Sagua, R., Parra, V., Troncoso, R. Differential Effects of Oleic and Palmitic Acids on Lipid Droplet-Mitochondria Interaction in the Hepatic Cell Line HepG2. Front. Nutr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Milovanović, V., Radulović, N., Todorović, Z., Stanković, M., Stojanović, G. Antioxidant, antimicrobial and genotoxicity screening of hydro-alcoholic extracts of five Serbian Equisetum species. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2007. [CrossRef]

- Hoang, M.H., Jia, Y., Lee, J.H., Kim, Y., Lee, S.J. Kaempferol reduces hepatic triglyceride accumulation by inhibiting Akt. J. Food Biochem. 2019. [CrossRef]

- Tie, F., Ding, J., Hu, N., Dong, Q., Chen, Z., Wang, H. Kaempferol and kaempferide attenuate oleic acid-induced lipid accumulation and oxidative stress in HepG2 cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L., Yang, L., Ahmad, K. Kaempferol ameliorates palmitate-induced lipid accumulation in HepG2 cells through activation of the Nrf2 signaling pathway. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Liu, P., Wu, P., Yang, B., Wang, T., Li, J., Song, X., Sun, W. Kaempferol prevents the progression from simple steatosis to non-alcoholic steatohepatitis by inhibiting the NF-κB pathway in oleic acid-induced HepG2 cells and high-fat diet-induced rats. J. Funct. Foods. 2021. [CrossRef]

| Peak | RT (min) | λmax (nm) | [M-H]- (m/z) | MSn (m/z) | Tentative identification | Quantification (mg/g) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G. lucidum | G. purpureum | ||||||||

| EtOH 80% | Decoction | EtOH 80% | Decoction | ||||||

| 1g | 4.94 | 321.00 | 353 | MS2:191(100),179(82),135(12) | 3-O-Caffeoylquinic acid | 10.14±0.04a | 9.66±0.01c | 2.33±0.03d | 9.97±0.02b |

| 2g | 5.75 | 270 | 799 | MS2:301(100) | Ellagitannin | 2.21±0.02d | 3.09±0.03a | 1.933±0.004b | 2.87±0.01c |

| 3g | 6.59 | 324 | 337 | MS2:191(12),163(100),119(23) | 3-O-p-Coumaroylquinic acid | 0.703±0.002d | 0.84±0.02c | 1.45±0.03a | 1.29±0.02b |

| 4g | 7.63 | 326 | 367 | MS2:193(100),191(16),173(14),149(25) | 3-O-Feruloylquinic acid | 0.52±0.01c | 0.646±0.003b | 0.205±0.001d | 0.73±0,01a |

| 5g | 11.06 | 277 | 951 | MS2:933(100),613(4),462(6),301(8) | Geraniin isomer I | 14.32±0.01b | 4.2±0.07d | 7.47±0.04c | 39.89±0.04a |

| 6g | 12.15 | 277 | 951 | MS2:933(100),613(4),462(6),301(8) | Geraniin isomer II | n.d. | n.d. | n.d. | 4.22±0.01 |

| 7g | 14.55 | 281 | 755 | MS2:301(100) | Ellagic acid dideoxyhexosyl-hexoside | 1.48±0.01* | 1.504±0.003* | n.d. | n.d. |

| 8g | 15.84 | 280 | 609 | MS2:301(100) | Ellagic acid deoxyhexosyl-hexoside isomer I | 1.75±0.005b | 1.358±0.001c | 1.291±0.001d | 1.94±0.01b |

| 9g | 16.17 | 280 | 609 | MS2:301(100) | Ellagic acid deoxyhexosyl-hexoside isomer II | 2.33±0.05a | 1.646±0.002c | 1.285±0.001d | 1.9004±0.0002b |

| 10g | 16.54 | 280 | 609 | MS2:301(100) | Ellagic acid deoxyhexosyl-hexoside isomer III | 2.23±0.02b | 1.68±0.01c | 1.337±0.002d | 3.091±0.002a |

| 11g | 17.06 | 281 | 433 | MS2:301(100) | Ellagic acid pentoside | 2.12±0.004b | 1.79±0.01c | 1.66±0.01d | 4.02±0.09a |

| 12g | 17.76 | 279 | 609 | MS2:301(100) | Ellagic acid deoxyhexosyl-hexoside isomer IV | 1.81±0.02a | 1.59±0.01b | 0.537±0.004d | 0.79±0.01c |

| 13g | 18.56 | 348 | 593 | MS2:285(100) | Luteolin-O-deoxyhexosyl-hexoside isomer I | 1.63±0.02b | 0.95±0.01c | n.d. | 2.399±0.004a |

| 14g | 19.04 | 280 | 301 | - | Ellagic acid | 3.4196±0.0003b | 7.987±0.004a | 1.337±0.002d | 3.091±0.002c |

| 15g | 19.83 | 361 | 761 | MS2:609(12),301(100),151(12) | Quercetin galloyl O-deoxyhexosyl-hexoside | 0.84±0.01** | 1.115±0.001** | n.d. | n.d. |

| 16g | 20.33 | 357 | 615 | MS2:463(12),301(100) | Quercetin galloyl O-hexoside | 0.74±0.01* | 0.74±0.01* | n.d. | n.d. |

| 17g | 21.08 | 349 | 593 | MS2:285(100) | Luteolin-O-deoxyhexosyl-hexoside isomer II | 0.81±0.01a | 0.732±0.004c | 0.52±0.001d | 0.76±0.01a |

| 18g | 21.38 | 348 | 447 | MS2:285(100) | Luteolin-O-hexoside isomer I | 0.96±0.01b | 0.71±0.01c | 1.01±0.01a | n.d. |

| 19g | 22.03 | 353 | 623 | MS2:315(100) | Isorhamnetin O-deoxyhexosyl-hexoside | 0.63±0.01** | 0.59±0.01** | n.d. | n.d. |

| 20g | 22.59 | 348 | 447 | MS2:285(100) | Luteolin-O-hexoside isomer II | 1.23±0.01** | 0.697±0.004** | n.d. | n.d. |

| 21g | 23.11 | 353 | 745 | MS2:593(12),459(89),285(100) | Luteolin galloyl O-deoxyhexosyl-hexoside | 0.9±0.01a | 0.61±0.01b | 0.91±0.01a | n.d. |

| 22g | 23.5 | 353 | 591 | MS2:301(100) | Quercetin derivative | 0.83±0.01a | 0.539±0.002b | 0.83±0,01a | n.d. |

| 23g | 24.27 | 351 | 599 | MS2:285(100) | Luteolin galloyl O-hexoside | 0.97±0.01a | 0.583±0.003b | 0.97±0.01a | n.d. |

| 24g | 26.79 | 349 | 575 | MS2:285(100) | Luteolin derivative | 1.04±0.01a | 0.589±0.003b | 1.04±0.01a | n.d. |

| Total phenolic acids | 11.36±0.04b | 11.144±0.004c | 3.99±0.06d | 11.99±0.01a | |||||

| Total ellagic derivatives | 31.67±0.09b | 24.86±0.09c | 18.44±0.03d | 65.13±0.13a | |||||

| Total flavonoids | 10.35±0.01a | 7.85±0.01b | 5.8±0.01c | 1.558±0.002d | |||||

| Total phenolic compounds | 53.38±0.12b | 43.85±0.08c | 28.22±0.02d | 78.69±0.14a | |||||

| Peak | RT (min) | λmax (nm) | [M-H]- (m/z) | MSn (m/z) | Tentative identification | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantification (mg/g extract) | |||||||

| EtOH 80% | Decoction | ||||||

| 1e | 5.08 | 246,271sh,352 | 771 |

MS2:609(100). MS3:429(100),285(53) |

Kaempherol-O-dihexosyl-O-dihexoside isomer I | 5.6355±0.0049* | 4.08±0.01* |

| 2e | 5.93 | 246,271sh,352 | 771 | MS2:609(100). MS3:429(100),285(35) |

Kaempherol-O-dihexosyl-O-dihexoside isomer II | 1.245±0.01* | 0.934±0.001* |

| 3e | 6.36 | 264,301,328 | 787 | MS2:625(100). MS3:463(100),301(79) |

Quercetin-O-dihexosyl-O-dihexoside | 0.756±0.01* | 0.762±0.001* |

| 4e | 6.70 | 284.00 | 355 | MS2:193(100),178(18) | Ferulic acid hexoside isomer I | 0.313±0.005* | 0.221±0.004* |

| 5e | 7.83 | 266,248 | 813 | MS2:651(100),285(34) | Kaempherol-O-hexosyl-O-acetyl-dihexoside | 0.659±0.0037* | 0.595±0.001* |

| 6e | 8.25 | 284.00 | 355 | MS2:193(100),178(23) | Ferulic acid hexoside isomer II | 0.59±0.01* | 0.41±0.01* |

| 7e | 10.68 | 266,307,327 | 537 | MS2:375(100),195(34) | Cupressuflavone | 2.205±0.01* | 2.003±0.004* |

| 8e | 15.11 | 246,271sh,352 | 771 | MS2:609(100). MS3:429(100),285(98) |

Kaempherol-O-dihexosyl-O-dihexoside isomer III | 0.973±0.01* | 0.75±0.01* |

| 9e | 16.57 | 347.00 | 609 | MS2:285(100) | Kaempherol-O-dihexoside | 1.718±0.003** | 1.718±0.003** |

| 10e | 17.29 | 324.00 | 193 | MS2:178(34),134(100) | Ferulic acid | 0.142±0.001* | 0.164±0.003* |

| 11e | 20.99 | 345.00 | 651 | MS2:609(65),285(100) | Kaempherol-O-acetyl-dihexoside | 0.5291±0.0004 | n.d. |

| Total phenolic acids | 1.044±0.01* | 0.793±0.005* | |||||

| Total flavonoids | 13.721±0.02* | 10.848±0.004* | |||||

| Total phenolic compounds | 14.765±0.01* | 11.64±0.01* | |||||

| Peak | RT (min) | λmax (nm) | [M-H]- (m/z) | MSn (m/z) | Tentative identification | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantification (mg/g extract)* | |||||||

| EtOH 80% | Decoction | ||||||

| 1r | 5.51 | 324.00 | 341 | MS2:179(100),135(18) | Caffeic acid hexoside | 0.33±0.007 | 0.175±0.006 |

| 2r | 5.73 | 345 | 577 | MS2:413(100),293(32) | Rhamnosylvitexin | 1.221±0.019 | 0.833±0.017 |

| 3r | 6.49 | 264,329 | 947 | MS2:785(100). MS3:639(100),315(78) |

Isorhamnetin-O-caffeoyl-O-deoxyhexosyl-dihexoside isomer I | 0.6233±0.0002 | 0.5534±0.0005 |

| 4r | 6.72 | 264,311 | 947 | MS2:785(100). MS3:639(100),315(78) |

Isorhamnetin-O-caffeoyl-O-deoxyhexosyl-dihexoside isomer II | 0.626±0.006 | 0.587±0.001 |

| 5r | 7.87 | 311 | 325 | MS2: 163(29),145(100),119(17) | cis p-Coumaric acid hexoside | 0.164±0.004 | 0.11±0.002 |

| 6r | 8.32 | 311 | 325 | MS2: 163(29),145(100),119(17) | trans p-Coumaric acid hexoside | 0.162±0.003 | 0.092±0.001 |

| 7r | 9.37 | 312 | 355 | MS2: 193(100),179(11),149(78) | Ferulic acid hexoside isomer I | 0.7115±0.0004 | 0.464±0.001 |

| 8r | 9.88 | 312 | 355 | MS2: 193(100),179(16),149(61) | Ferulic acid hexoside isomer II | 0.225±0.008 | 0.147±0.004 |

| 9r | 14 | 340 | 563 | MS2: 545(5),503(6),473(78),443(100) | Apigenin 6-C-hexosyl-8-C-pentoside | 0.201±0.008 | 0.087±0.017 |

| 10r | 14.71 | 348 | 579 | MS2: 459(5),429(71),357(54),327(100),285(5) | Luteolin-6-C-(2-O-Pentosyl)Hexoside isomer I | 4.147±0.053 | 2.645±0.029 |

| 11r | 15 | 345 | 579 | MS2: 459(5),429(65),357(56),327(100),285(5) | Luteolin-6-C-(2-O-Pentosyl)Hexoside isomer II | 1.685±0.04 | 0.958±0.047 |

| 12r | 16.55 | 336 | 563 | MS2: 443(5),413(100),293(13) | Apigenin-C-hexoside-O-pentoside isomer I | 1.209±0.002 | 0.718±0.007 |

| 13r | 17.33 | 336 | 563 | MS2: 443(5),413(100),293(13) | Apigenin-C-hexoside-O-pentoside isomer II | 0.184±0.005 | 0.103±0.007 |

| 14r | 17.95 | 351 | 609 | MS2:301(100) | Quercetin-3-O-rutinoside | 0.529±0.002 | 0.499±0.001 |

| 15r | 18.56 | 335 | 431 | MS2:341(22),311(100). MS3:283(100) |

Apigenin-C-hexoside | 0.144±0.009 | 0.071±0.004 |

| 16r | 18.87 | 355 | 639 | MS2:315(100) | Isorhamnetin-O-dihexoside isomer I | 0.499±0.001 | 0.4826±0.0005 |

| 17r | 22.21 | 354 | 623 | MS2:315(100) | Isorhamnetin-O-dihexoside isomer II | 0.5159±0.0002 | 0.496±0.001 |

| Total phenolic acids | 1.593±0.007 | 0.989±0.005 | |||||

| Total flavonoids | 11.584±0.123 | 8.033±0.107 | |||||

| Total phenolic compounds | 13.177±0.116 | 9.023±0.112 | |||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).