3.3. Amount of carbon materials

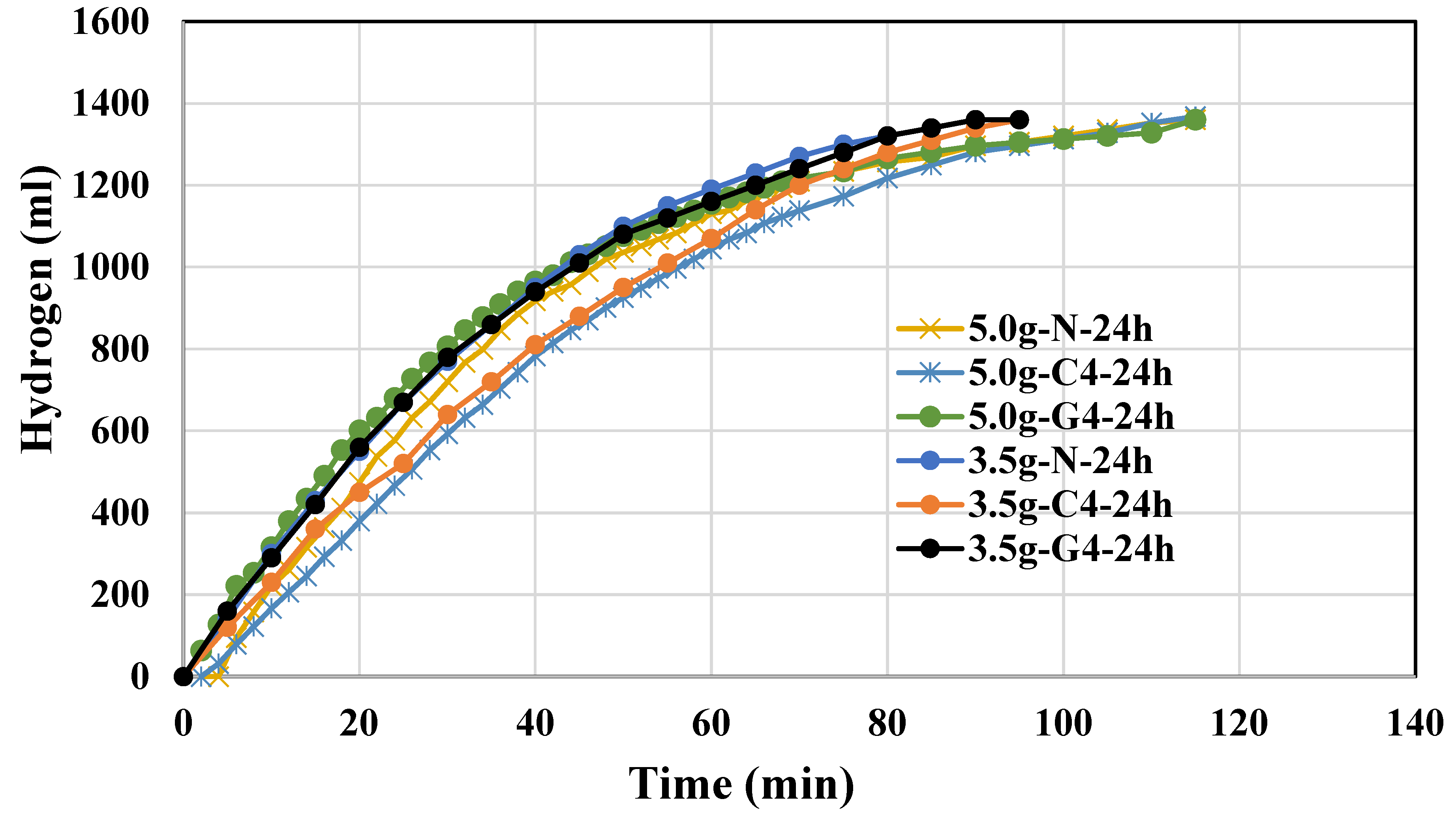

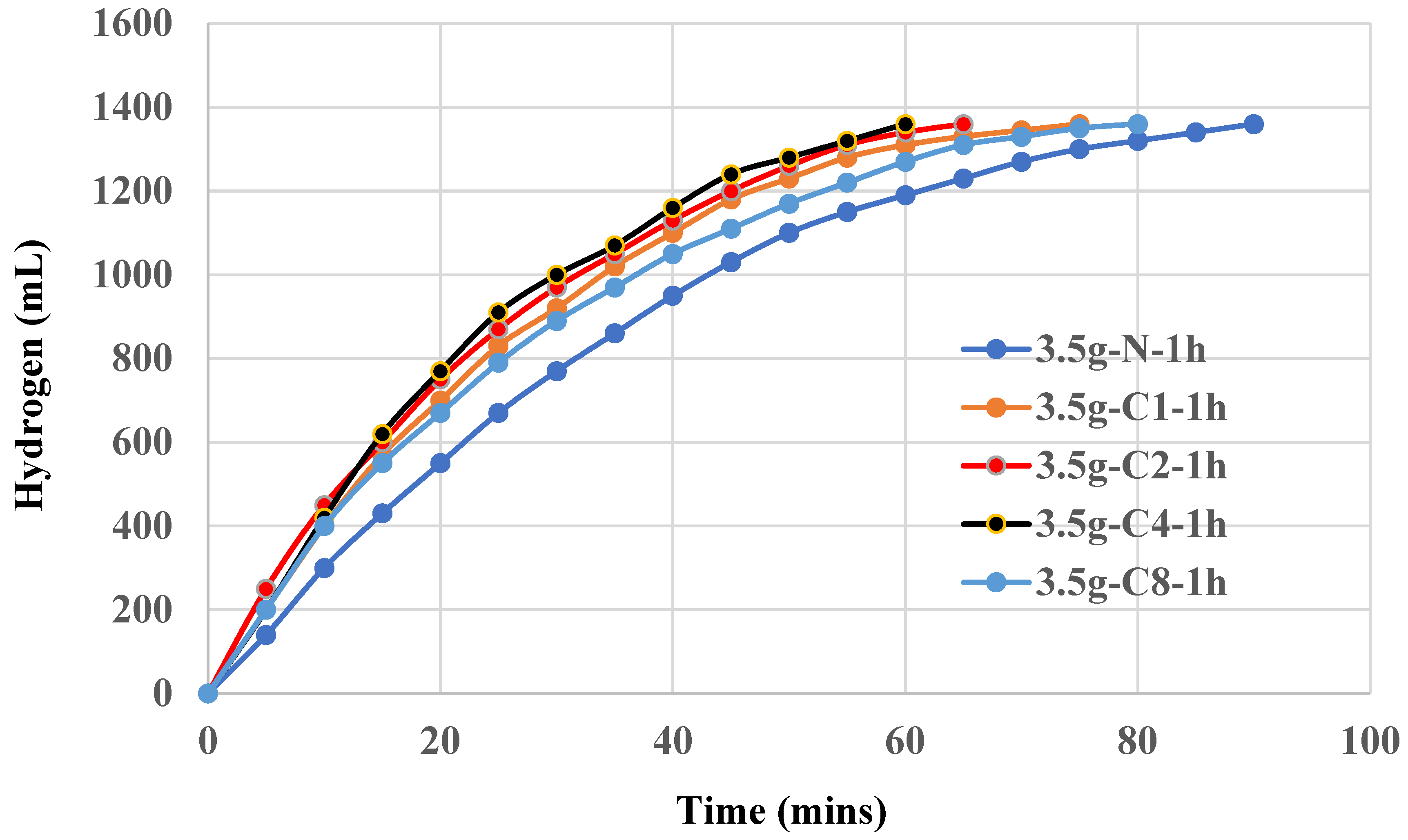

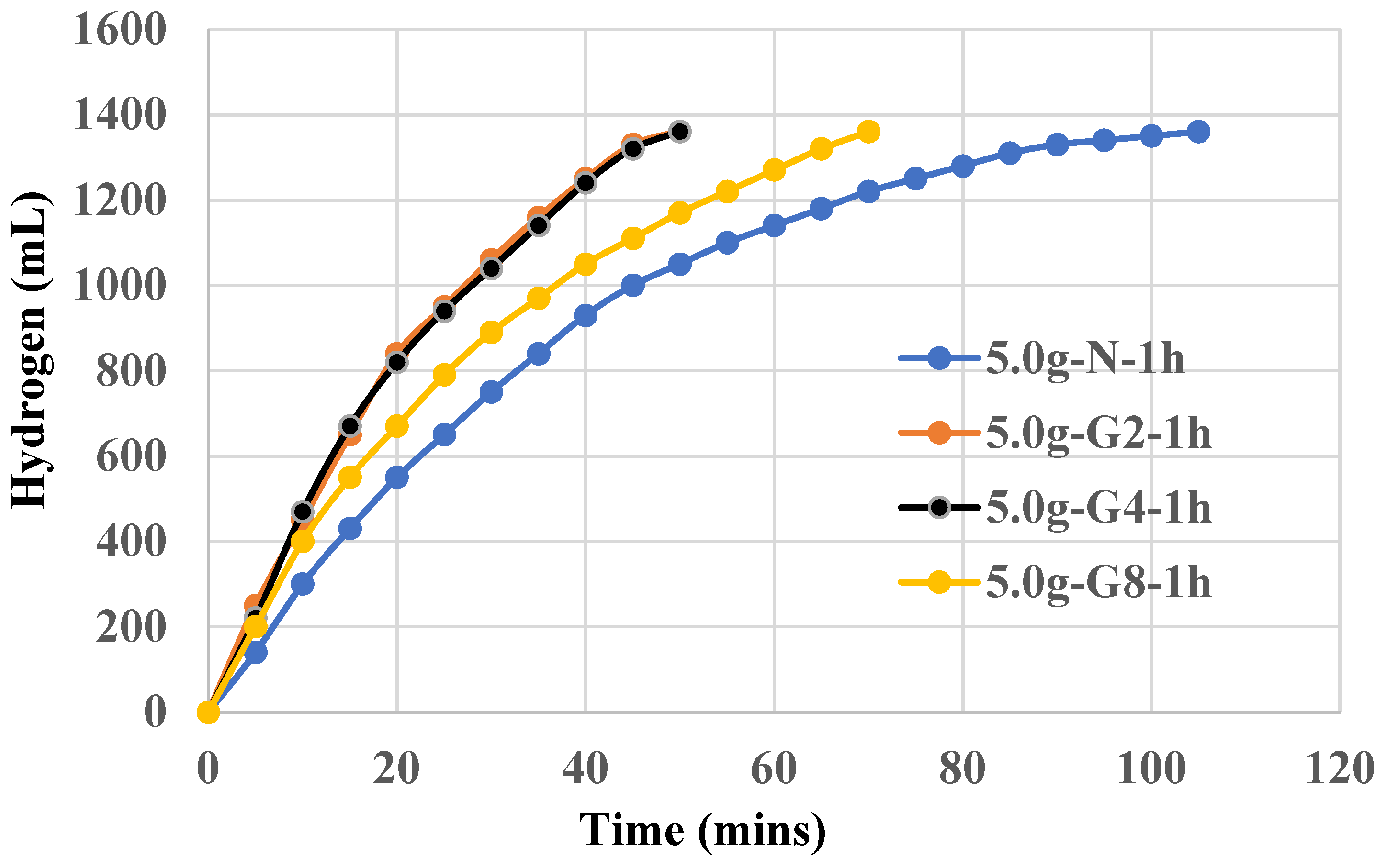

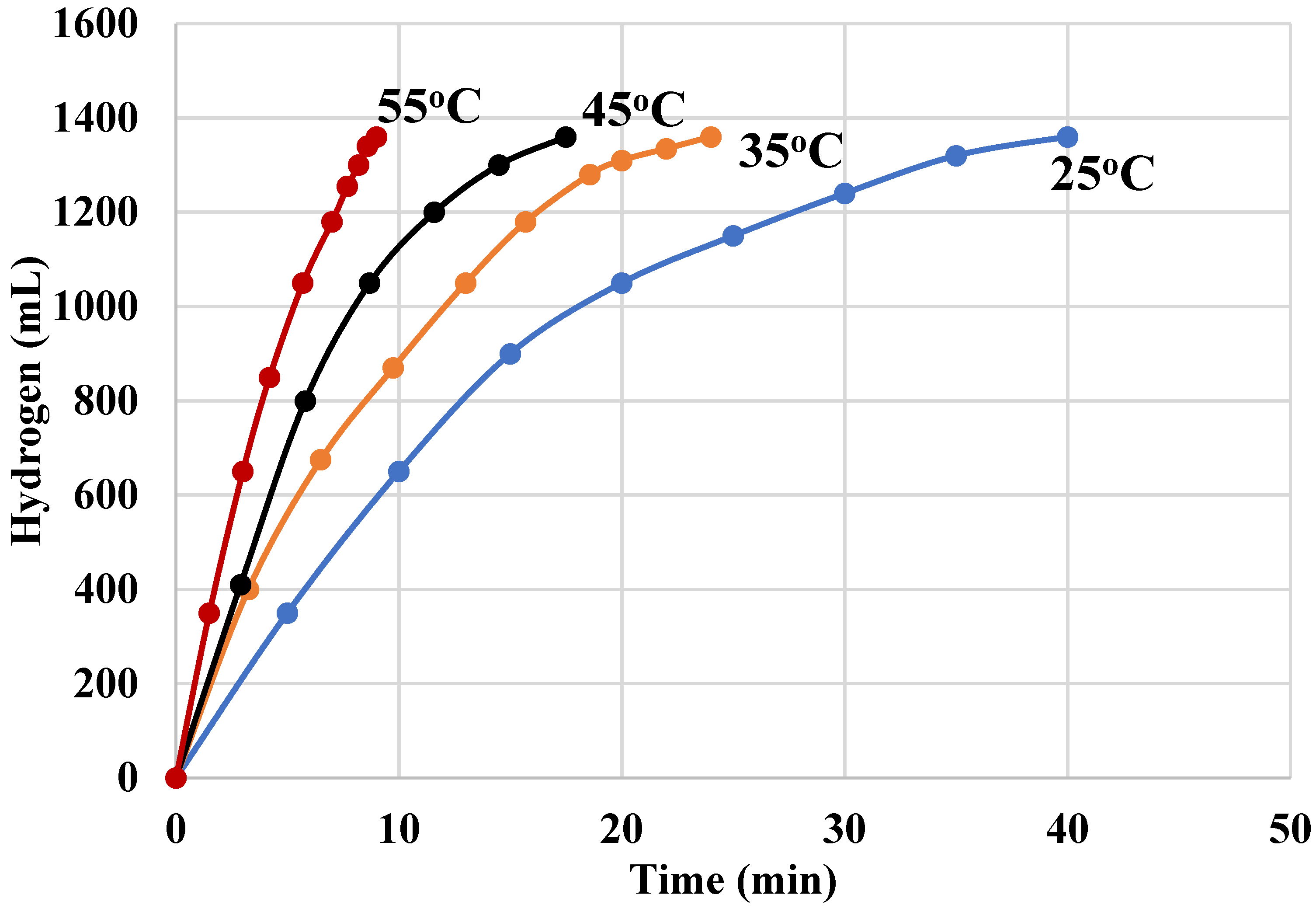

As shown in

Figure 3, addition of 0.1g to 0.8g carbon black during the synthesis of aluminum hydroxide seem slightly enhance the catalytic effect. 0.2~0.4g carbon black shows an optimum effect in this case. At lower concentrations, 0.1g, there may not be enough carbon black to significantly enhance the dispersion of aluminum hydroxide particles. The surface area provided by the carbon black might be insufficient to create a noticeable improvement in catalytic activity. In the range of 0.2~0.4g, carbon black provides an optimal balance between dispersion and overcrowding. The amount of carbon black is enough to enhance the dispersion of aluminum hydroxide particles effectively, increasing the number of active sites available for the aluminum-water reaction. This leads to a noticeable enhancement in catalytic activity, reducing the duration of 100% yield of hydrogen from 90 mins to 60 mins. At higher concentrations, 0.8g, the carbon black could cause agglomeration or overcrowding of aluminum hydroxide particles. This reduces the overall effective surface area and hinders the accessibility of active sites. Additionally, excessive carbon black might block some of the active sites on aluminum hydroxide, counteracting the benefits and leading to only a slight enhancement in catalytic activity.

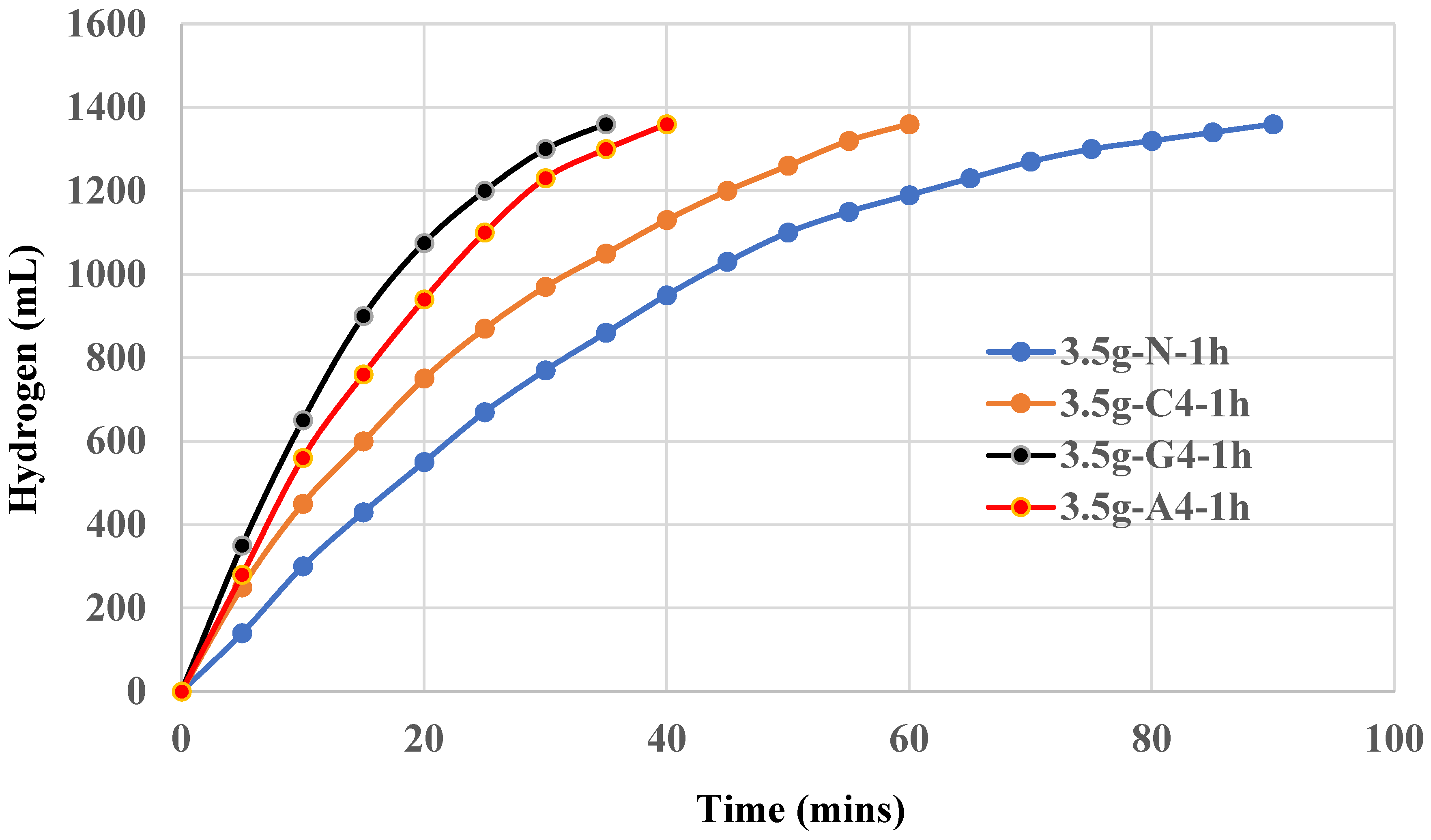

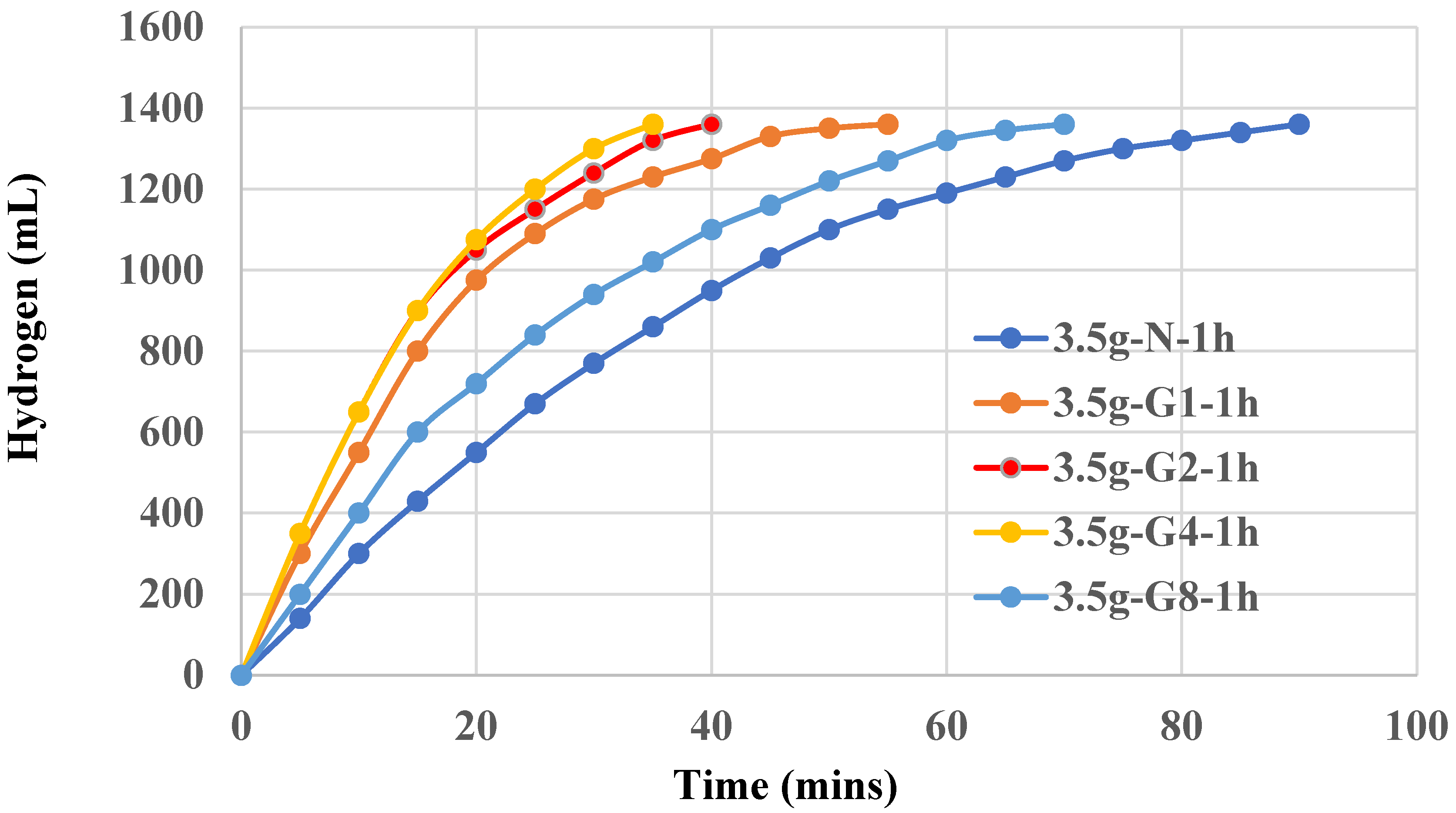

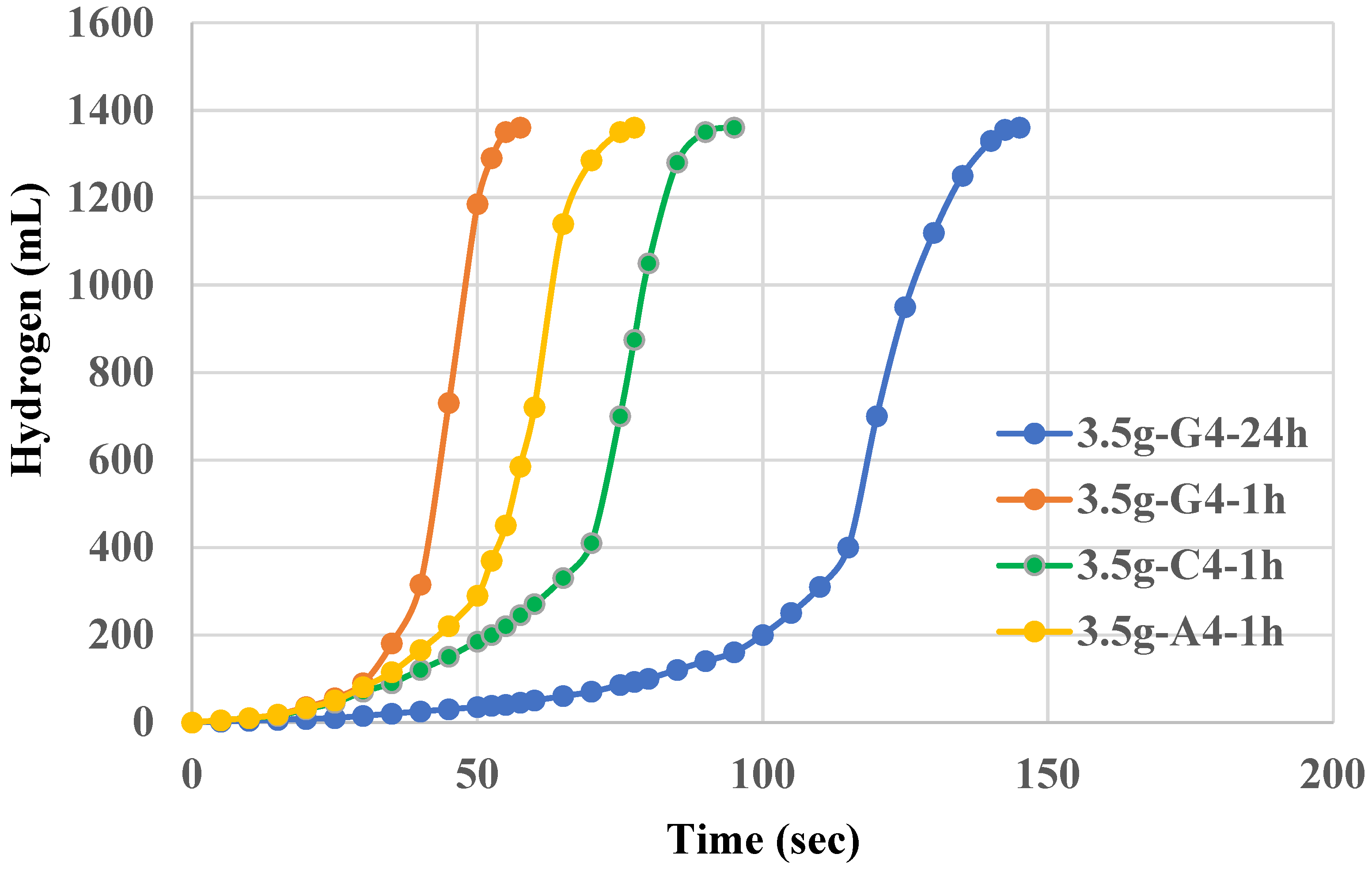

Graphite shows a clearly synergistic effect on aluminum hydroxide and is demonstrated in

Figure 4. Again, 0.2~0.4 g addition exhibits an optimal effect. Lower or higher amount of graphite did not show better results. It is observed that graphite is a better supporting material for Al(OH)

3 catalyst and 0.4g graphite results in an optimal effect which in turn helps the completion of 100% yield of hydrogen in 35 mins using Setup A method.

The use of 5.0g NaAlO2 did not show improvement on the catalytic power of Al(OH)3 but inferior to those of 3.5g. Higher amount of sodium aluminate such as 7.5g also results in an inferior Al(OH)3 catalyst. For 5.0g-N-1h, it takes more than 100 mins to complete 100% yield of hydrogen. The use of 7.5g or 5g NaAlO2 instead of 3.5g to form Al(OH)3 precipitates likely results in larger particle sizes, reduced surface area, and possible changes in crystallinity and purity, all of which contribute to the observed decrease in catalytic power. The optimal catalytic activity is achieved when the conditions for precipitation are carefully controlled to produce small, uniform, and highly active Al(OH)3 particles, which is more likely with the lower concentration of NaAlO2. Indeed, we have synthesized Al(OH)3 powders using 3.5g, 5.0g, 7.5g NaAlO2 precursor and those morphologies will be shown in FESEM later.

3.5. The Morphology

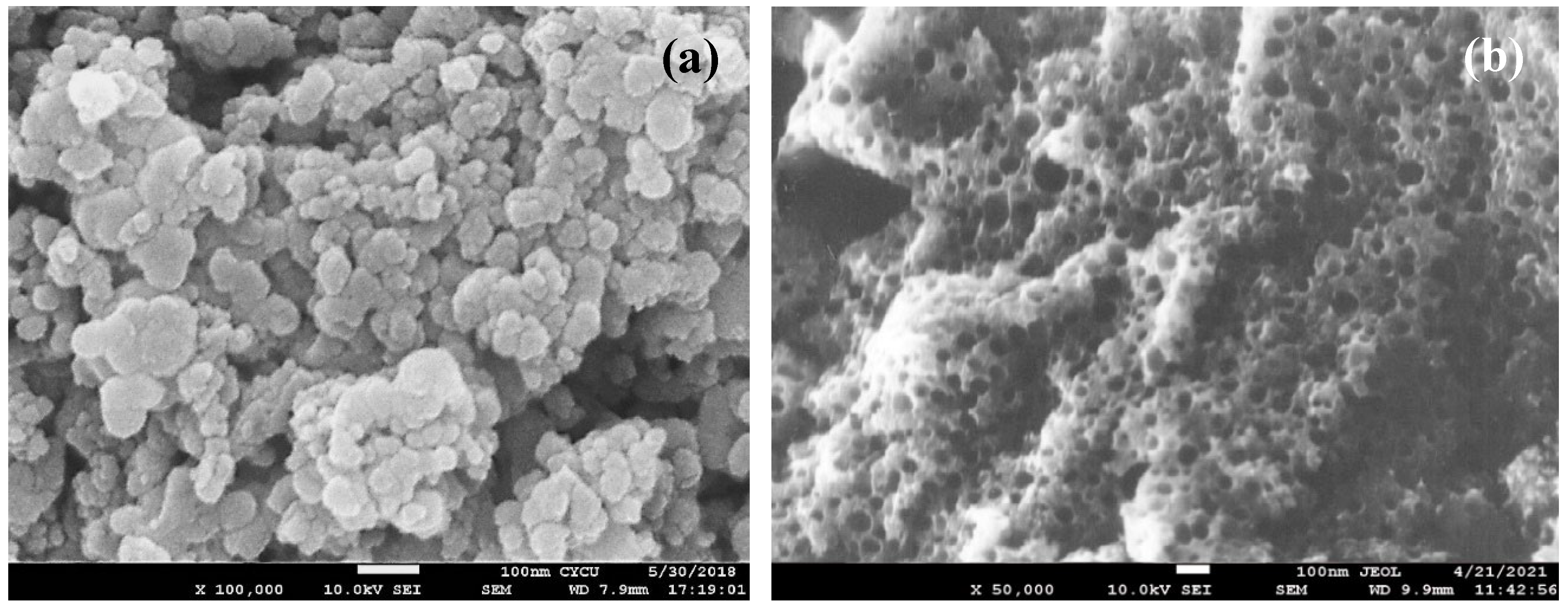

As shown in

Figure 7, carbon black before and after the activation treatment. It shows that the carbon black with numerous pores ~100 nm in their bulk structure, while before the activation, their did not have these pores. These differences may result in a better distribution of Al(OH)

3 catalyst, and contacts with the reactant Al powders.

The bulk electrical conductivity of graphite, carbon black, and activated carbon black has been measured and were obtained as 2.02 Ω/cm, 199.81 Ω/cm, and 197.32 Ω/cm, respectively. The graphite has good conductivity and the activated carbon black has slightly better conductivity than that of carbon black. As shown in the results of previous paragraphs, graphite has the best synergistic effect with Al(OH)3, while activated carbon black ranks the second. The reasons that activated carbon black may exhibit a better effect than those of plain carbon black may come from following causes. 1. Activated carbon black has a porous structure where would provide more active sites for the reaction to occur. This facilitates better dispersion of aluminum hydroxide, enhancing its catalytic efficiency. 2. The structure of activated carbon black helps in dispersing the aluminum hydroxide particles more uniformly. This uniform dispersion improves the contact between aluminum and water, leading to more efficient hydrogen production. 3. Activated carbon black possesses unique chemical and physical properties such as higher electrical conductivity and surface area. These properties contribute to the enhanced catalytic performance by facilitating electron transfer processes and maintaining structural integrity during the reaction. 4. The surface of activated carbon black can contain various functional groups that interact with aluminum hydroxide. These interactions can modify the surface properties of aluminum hydroxide, making it more reactive towards water.

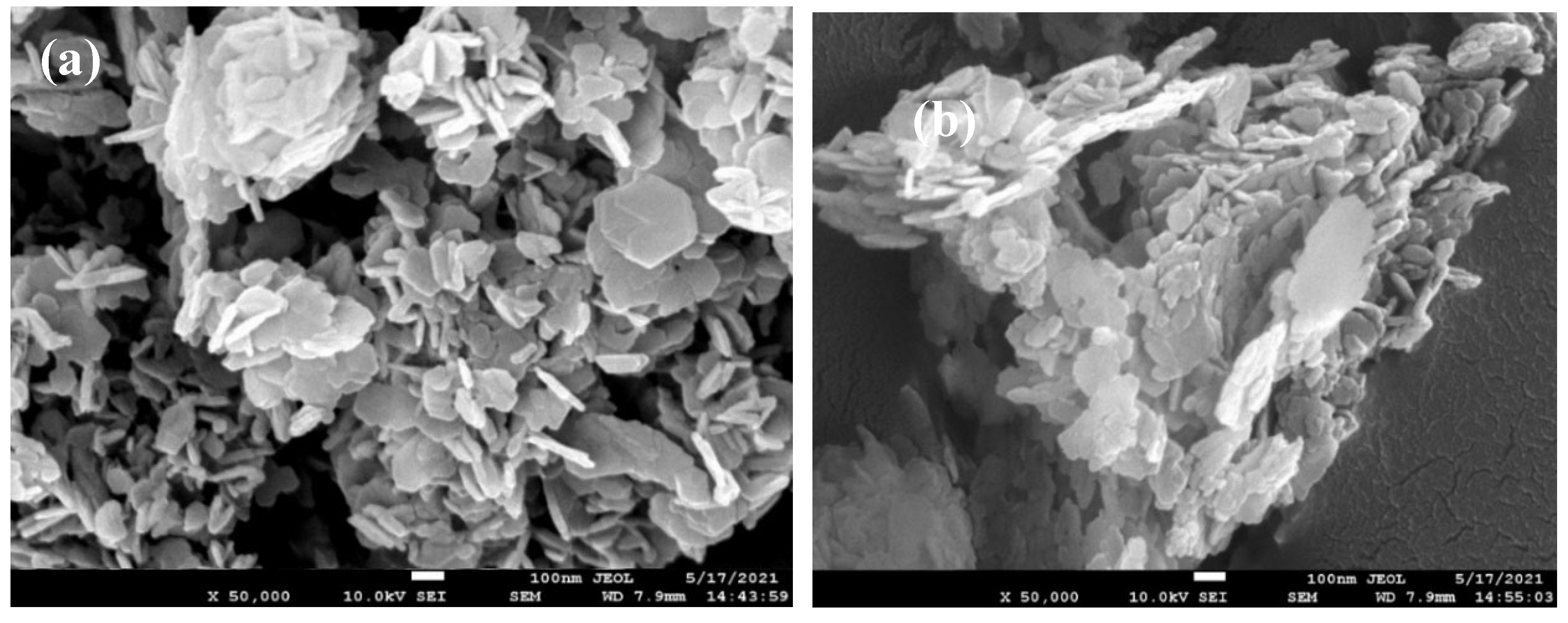

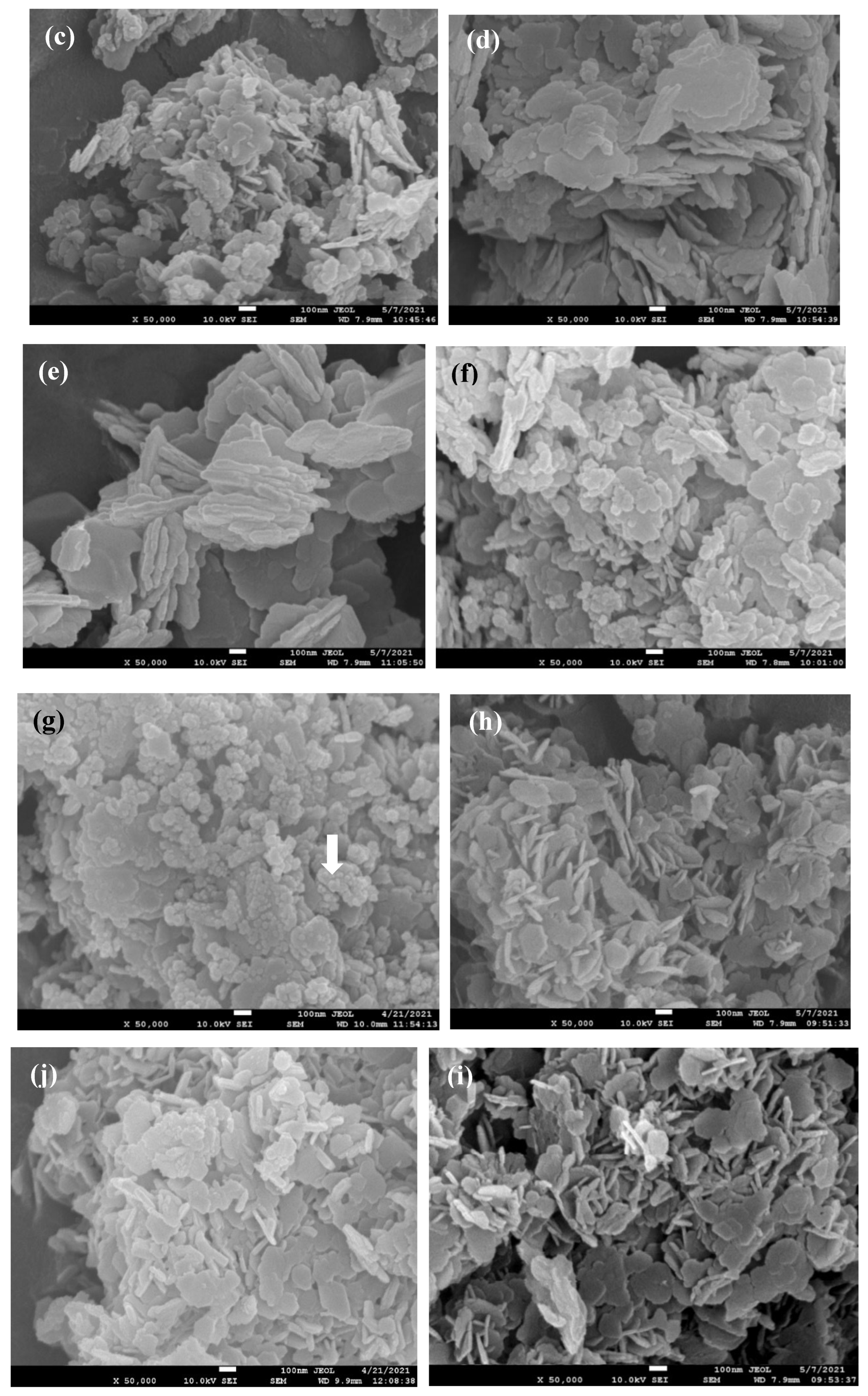

Figure 8 (a) to (j) present a detailed comparison of the morphological features of aluminum hydroxide catalysts, both with and without the addition of various carbon materials (G for graphite, C for carbon black, and A for activated carbon black). Across all images, a commonality is the presence of aluminum hydroxide plate-like structures, but significant differences emerge in terms of particle size, dispersion, and surface texture.

Figure 8 (a) and (b) display aluminum hydroxide powders synthesized without any carbon additives; however, the aging time is different. We noticed that the plate-like structure of Al(OH)

3 in both images are similar in size but long aging time (24h,

Figure 8 (b)) resulted in an agglomerated block. This clearly be the reason why this aluminum hydroxide big block did not show good catalytic power. Since large aggregates would have lower surface area and fewer active sites for the aluminum-water reaction.

Figure 8 (c) to (e) show aluminum hydroxide synthesized using 0.4 g carbon black and increasing concentrations of sodium aluminate precursor and aging for 24 h. The plate-like structure of Al(OH)

3 increased in size with increasing amounts of sodium aluminate, as compared from (c) to (e). It is understood that using a higher concentration of NaAlO

2 (0.5~0.75 g compared to 0.3g) can result in the formation of larger Al(OH)

3 plates due to increased supersaturation during the precipitation process. Larger particles have a smaller specific surface area and fewer active sites per unit weight for the catalytic reaction.

Figure 8 (c) to (e) demonstrate these understanding. However, by the presence of support materials such as carbon black, small plates of Al(OH)

3 seem not easily agglomerate into a big block even the aging time is 24 h, as compare the image of

Figure 8(b) and (c).

Figure 8 (f)(g) are for Al(OH)

3 with carbon black, and

Figure 8 (h)(i) with graphite and aging 1 h. We noticed that (f)(g) images exhibit obvious carbon black particles, while (h)(i) have distinct plate-like structures. As shown by the white arrow in

Figure 8 (g), the small spherical particles are confirmed to be carbon black, where 61% of carbon is detected by EDS (not shown). The graphite seems an excellent supporting material for the precipitation of small plates of Al(OH)

3, where very thin plates are distributed uniformly. And these small plate-like structure of Al(OH)

3 again was observed in the case of activated carbon black, as shown in

Figure 8(j), though not as distinct as those of graphite.

It is considered that graphite is composed of layers of carbon atoms arranged in a hexagonal lattice. This layered structure provides a template that can influence the growth of aluminum hydroxide crystals. When aluminum hydroxide forms in the presence of graphite, the layered nature of graphite can guide the crystallization process, promoting the formation of plate-like structures of Al(OH)₃. The smooth, flat surfaces of graphite layers provide an ideal substrate for the two-dimensional growth of aluminum hydroxide crystals. This can lead to the anisotropic (directionally dependent) growth of Al(OH)₃, resulting in plate-like morphologies. In contrast, carbon black consists of fine, spherical particles that aggregate into a fluffy, three-dimensional network. This structure lacks the directional guidance for the growth of the Al(OH)3 plates. The spherical, aggregated nature of carbon black particles leads to a more isotropic distribution of Al(OH)3. This distinction highlights how the choice of carbon material can significantly influence the morphology and, consequently, the catalytic performance of aluminum hydroxide in hydrogen production reactions.

Activated carbon black, despite being a porous structure, seems also result in a plate-like structure of Al(OH)₃ due to several reasons. The activation treatment on carbon black results in a very porous structure, as shown in

Figure 7(b). With these porous structures, it can be location for numerous nucleation sites for the formation of aluminum hydroxide crystals. These numerous nucleation sites can promote the growth of Al(OH)₃ in various orientations, including plate-like structures.

The porous nature of activated carbon black allows for enhanced diffusion of reactants and products throughout the material. This facilitates a more uniform and controlled growth environment, which can lead to the formation of well-defined crystal structures, such as plates. In addition, functional groups such as carboxyl and hydroxyl on its surface due to the activation process can interact with aluminum hydroxide precursors, influencing the nucleation and growth process in a manner that promotes the formation of plate-like structures. The presence of functional groups can also act as a template, guiding the crystallization of Al(OH)₃ into specific morphologies, including plate-like forms. This templating effect influences Al(OH)₃ morphology but occurs through chemical interactions rather than physical layering.

The porous structure of activated carbon black ensures a better dispersion of aluminum hydroxide throughout the material. This dispersion can prevent aggregation and allow individual Al(OH)₃ crystals to grow freely into plate-like structures. The pores provide a microenvironment that can control the growth kinetics of Al(OH)₃ crystals. This controlled environment can lead to anisotropic (directionally dependent) growth, favoring the formation of plate-like structures.

While graphite’s layered structure directly influences the planar growth of Al(OH)₃, activated carbon black achieves similar results through its high surface area, functional groups, and controlled dispersion within its porous network. Both materials enhance the catalytic activity of aluminum hydroxide but through different mechanisms: graphite by providing a physical template and activated carbon black by offering a chemically interactive and highly dispersed growth medium.

Figure 8.

FESEM of specimen, (a) 3.5g-N-1h, (b) 3.5g-N-24h, (c) 3.5g-C4-24h, (d) 5.0g-C4-24h, (e) 7.5g-C4-24h, (f) 3.5g-C2-1h, (g) 3.5g-C4-1h, (h) 3.5g-G2-1h, (i) 3.5g-G4-1h, (j) 3.5g-A2-1h. The white arrow in (g) is actually carbon black, confirmed by EDS, Al(OH)3 is usually plate-like structure.

Figure 8.

FESEM of specimen, (a) 3.5g-N-1h, (b) 3.5g-N-24h, (c) 3.5g-C4-24h, (d) 5.0g-C4-24h, (e) 7.5g-C4-24h, (f) 3.5g-C2-1h, (g) 3.5g-C4-1h, (h) 3.5g-G2-1h, (i) 3.5g-G4-1h, (j) 3.5g-A2-1h. The white arrow in (g) is actually carbon black, confirmed by EDS, Al(OH)3 is usually plate-like structure.

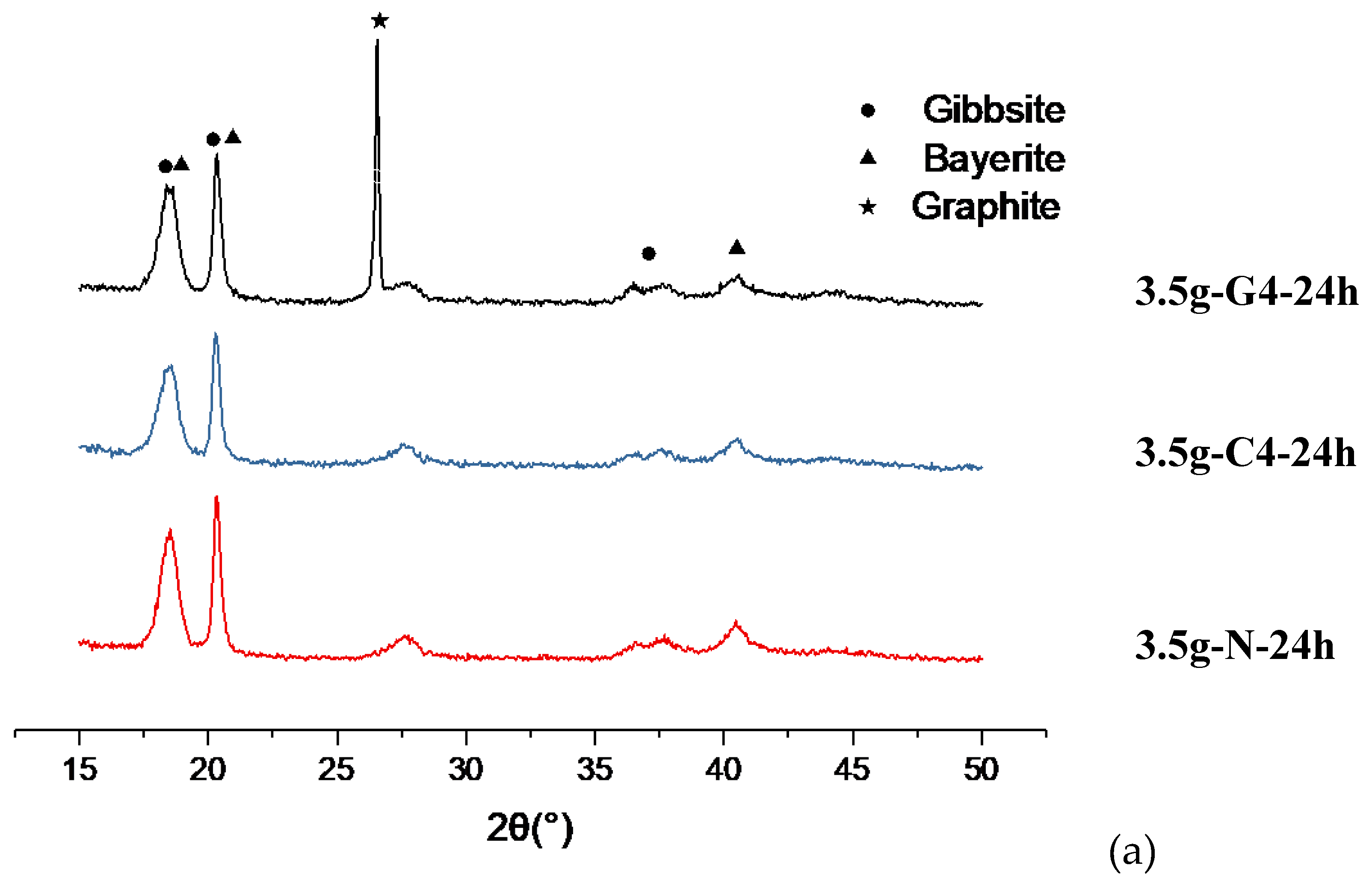

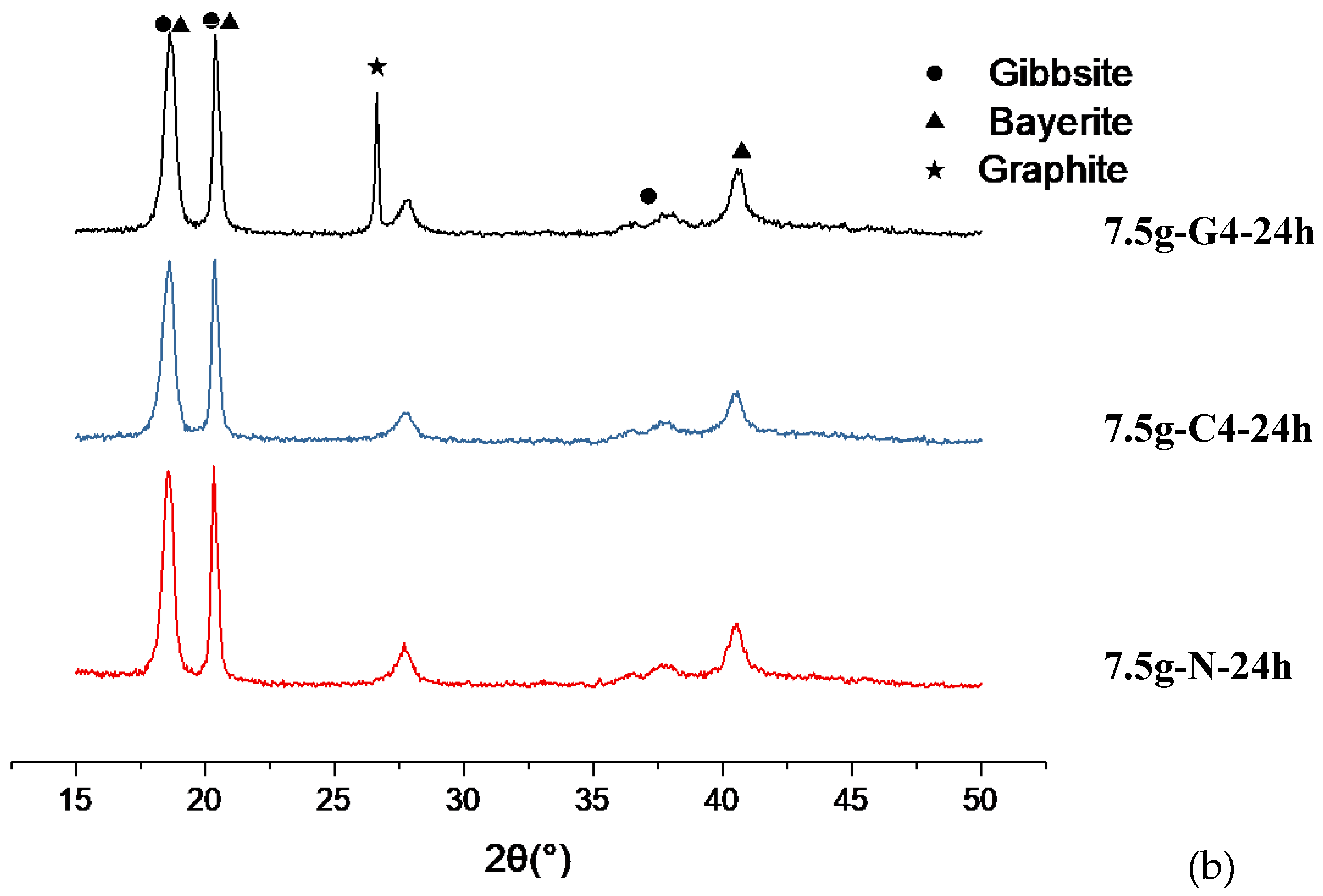

3.6. The Crystalline Structure

The crystalline phase of aluminum hydroxide has two major polymorphs, gibbsite and bayerite. Bayerite is less stable than gibbsite and can transform to the more stable gibbsite structure over time, especially in acidic environments [

18]. We can distinguish them from the XRD characteristic peaks’ heigh and position, listed in

Table 2, however, very tricky.

Gibbsite has first strong peak at 2θ = 18.29

o, and five other smaller peaks at 2θ = 20.32

o to 36.68

o, while bayerite has first two strong peaks at 2θ = 18.84

o and 20.42

o, and another strong peak at 2θ =40.64

o. Based on these distinct differences, we determined the crystal structure of 24 h series to be more bayerite phase-oriented mixed phases, as shown in

Figure 9(a)(b), regardless of the carbon materials. Since in this 24 h series, the intensity of the second peak counted from left to right are stronger than that of the first one, and the peak at 2θ=40.64

o is clear.

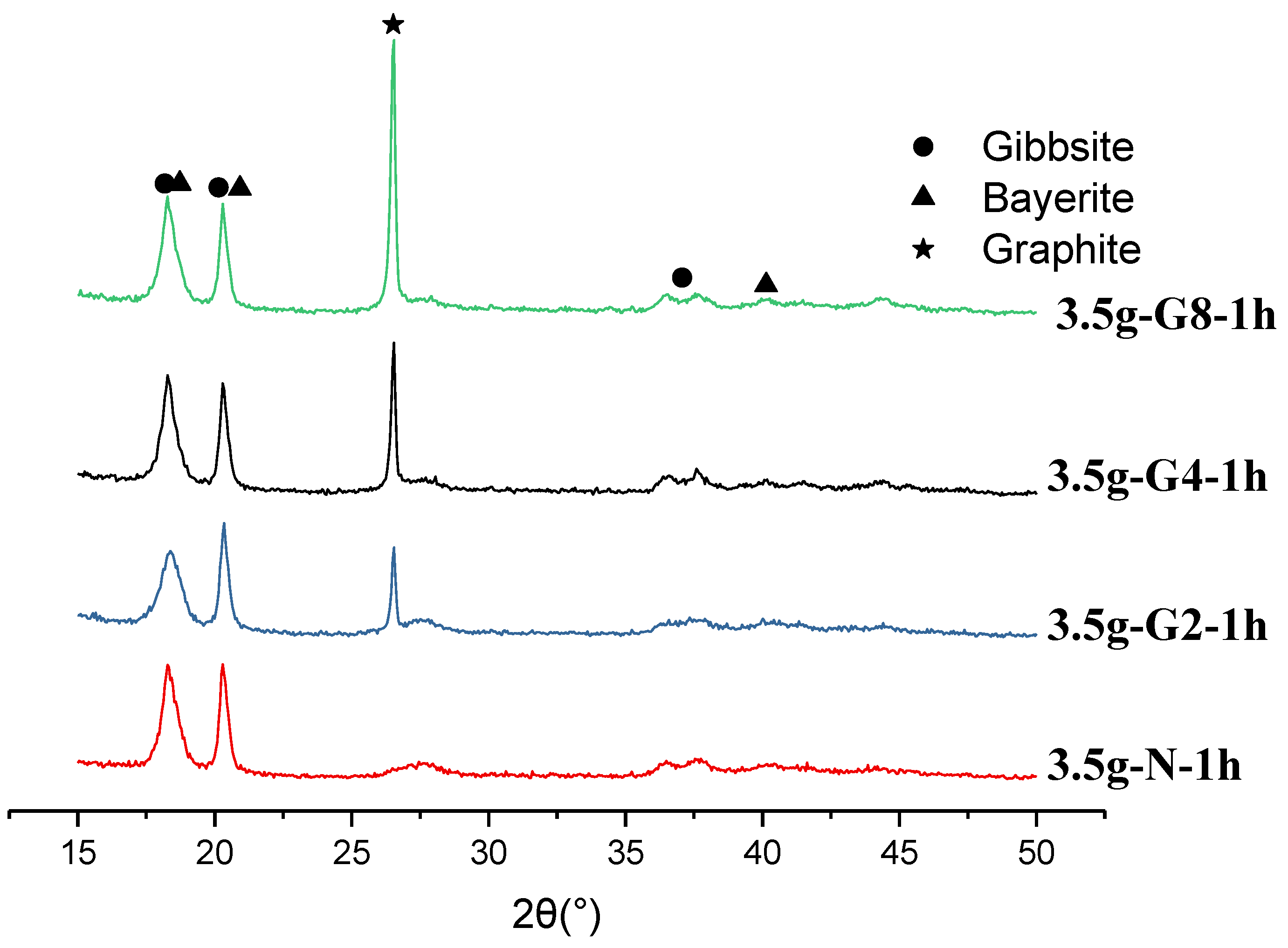

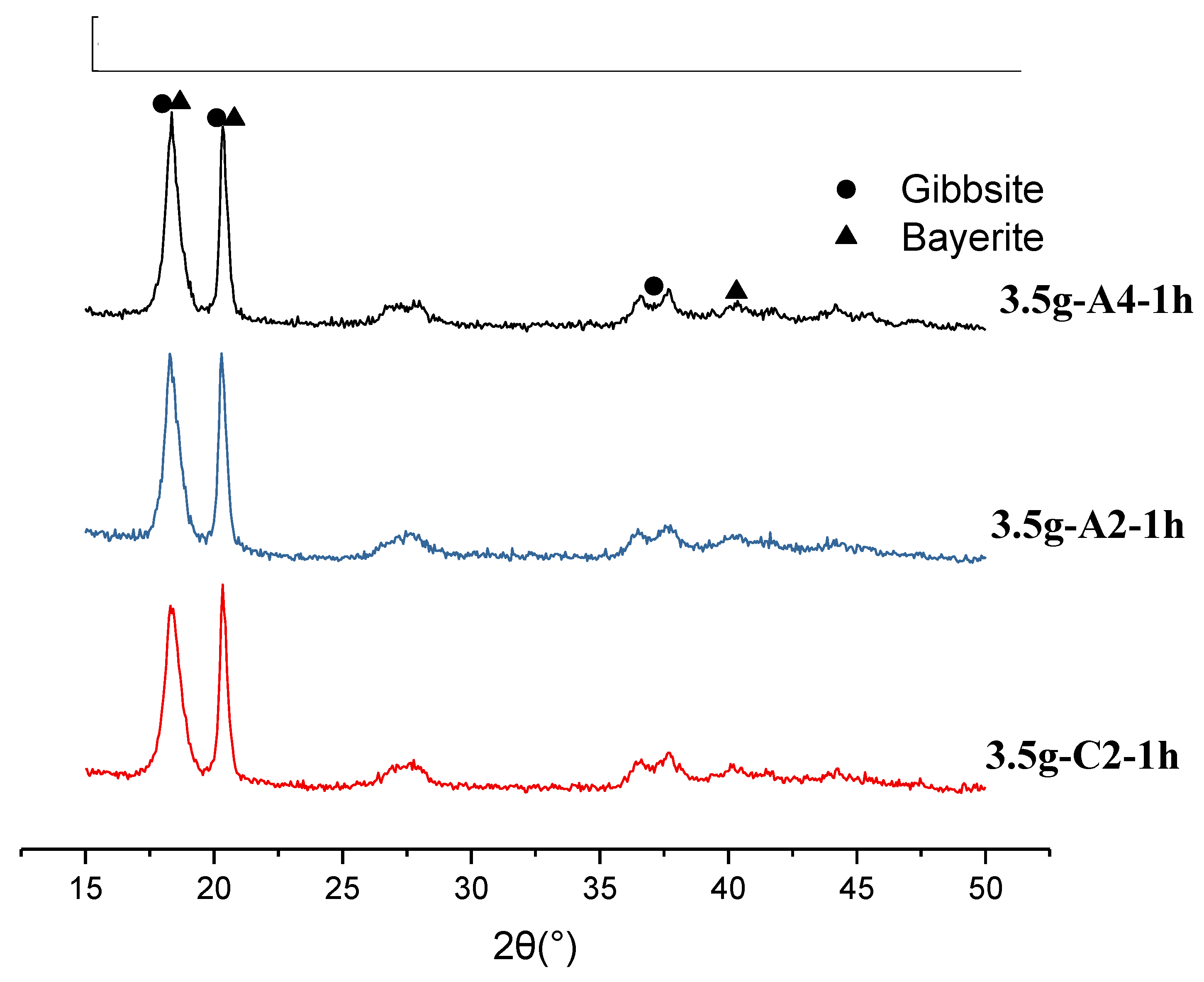

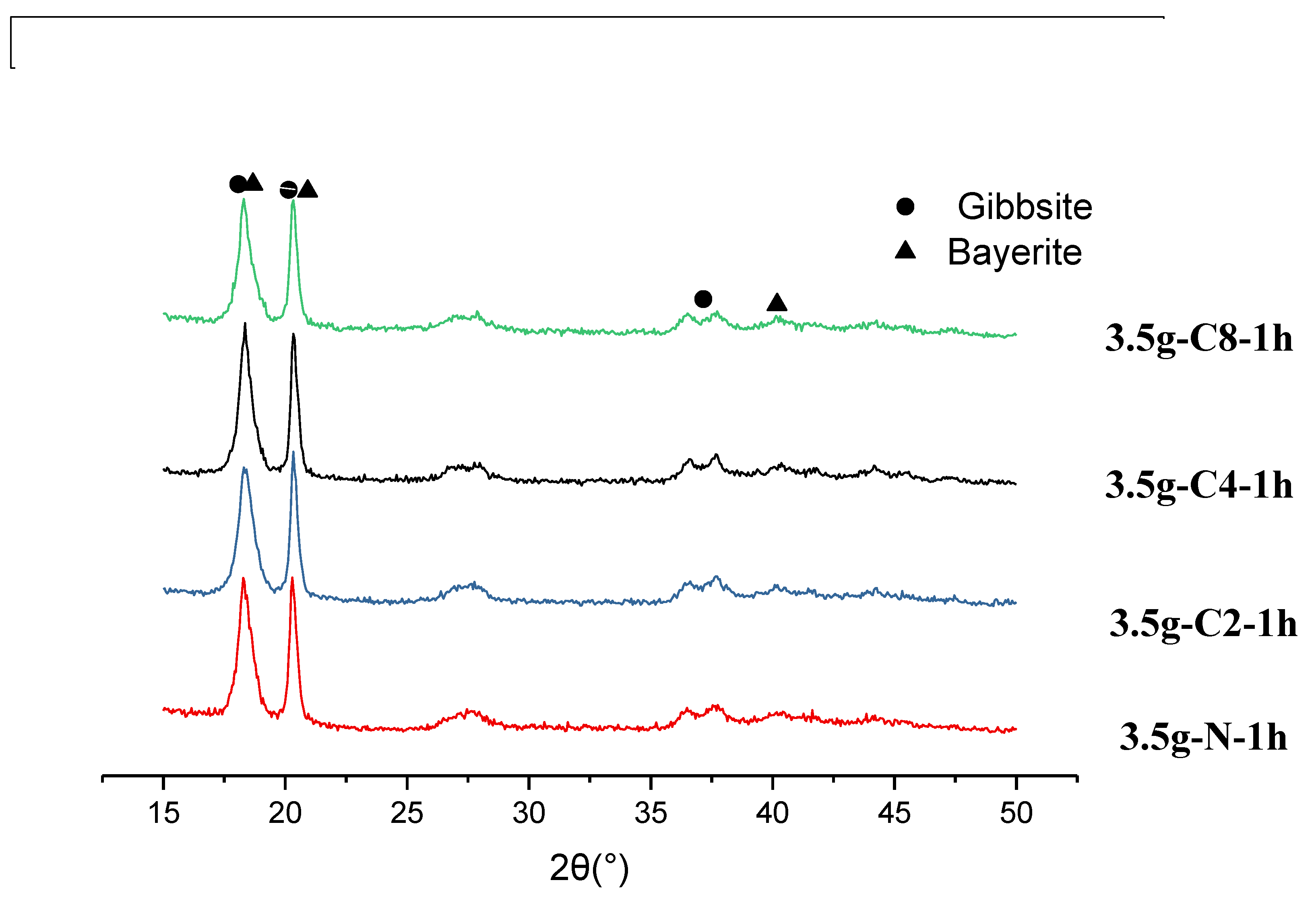

For the series of 1h, Figures 10~12 show the XRD results for 3.5g series aged in 1h with graphite, carbon black, and activated carbon black. All data show a mixed-phases of gibbsite and bayerite. However, the bayerite phase now is much less and it is more gibbsite-oriented phases. At the conditions of 0.4 g graphite, carbon black, and activated carbon black, the first peak of XRD is higher than the second one and the peak at 40.64o is weak, lower than those of 26.94~36.68o.

Figure 11.

XRD result for 3.5g-G-1h series, where graphite was 0.2g~0.8g. Mixed gibbsite and bayerite phases were observed.

Figure 11.

XRD result for 3.5g-G-1h series, where graphite was 0.2g~0.8g. Mixed gibbsite and bayerite phases were observed.

Figure 12.

XRD result for 3.5g-A-1h series, compared with 3.5g-C2-1h, where the activated carbon black was 0.2g and 0.4g. Mixed gibbsite and bayerite phases were observed.

Figure 12.

XRD result for 3.5g-A-1h series, compared with 3.5g-C2-1h, where the activated carbon black was 0.2g and 0.4g. Mixed gibbsite and bayerite phases were observed.

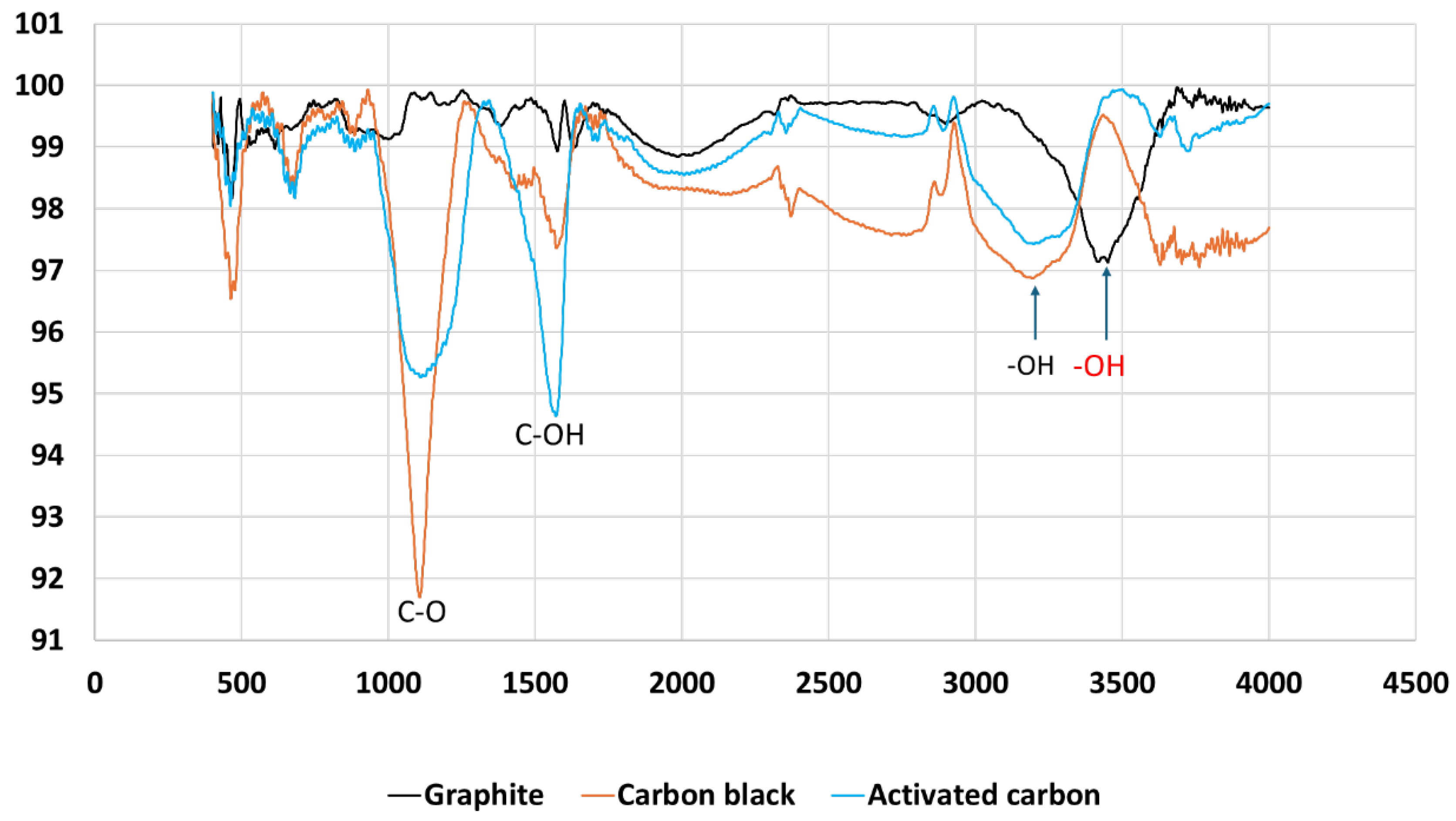

3.7. IR Spectroscopy Analysis

The catalytic performance of carbon-supported aluminum hydroxides can be correlated with their IR analysis. As shown in

Figure 13, The x-axis represents the wavenumber (cm⁻¹), which is inversely proportional to the wavelength. It ranges from 0 to 4500 cm⁻¹. The y-axis represents the transmittance percentage, ranging from 91% to 101%. Graphite (black line) shows relatively stable transmittance across the spectrum with minor fluctuations except a shifting to higher wavenumber OH functional group. Activated Carbon (blue line) displays pronounced dips, especially the C-O bond around 1000 cm⁻¹, and C-OH bond near 1500 cm⁻¹. Carbon Black (orange line) exhibits more significant dips, particularly the C-O bond around 1000 cm⁻¹.

Activated carbon shows a higher reactivity than carbon black due to the presence of hydroxyl groups and C-OH functionalities. These functional groups can interact with the aluminum hydroxide and the reaction intermediates, potentially altering the catalytic activity. The shift of the OH functional group to a higher wavenumber of graphite materials can provide valuable insights into the chemical environment and interactions within the material. The OH groups might be less involved in hydrogen bonding compared to other materials like Activated Carbon or Carbon Black. This can suggest that the OH groups in graphite are more isolated or less interacting with neighboring groups, which can affect the material’s reactivity and catalytic properties.

In a view of conducitivity and structure integrity, Graphite has excellent electrical conductivity, which can enhance electron transfer during the catalytic reaction. This property can facilitate the reduction of water and the oxidation of aluminum, leading to better hydrogen gas release. Activated Carbon and Carbon Black have lower electrical conductivity compared to Graphite, which can limit their catalytic effectiveness. Graphit has a layered structure that is more resistant to degradation under reaction conditions. This structural integrity can maintain the catalytic activity over time. Activated Carbon and Carbon Black may undergo structural changes or degradation during the reaction, which can reduce their catalytic effectivenes

In summary, the better catalytic effect of Graphite compared to Activated Carbon and Carbon Black can be attributed to its ordered structure, excellent electrical conductivity, and the shifted reactive functional groups. These properties facilitate a better electron transfer and interaction with the aluminum hydroxide, leading to more efficient hydrogen gas release. Activated Carbon has its catalytic activity improved by the adsorption of reaction intermediates and the presence of reactive functional groups, C-OH, compared to those of Carbon Black.