1. Introduction

Modern aero-engine is a complex aero-dynamic, thermal and mechanical equipment with harsh working environment and strong nonlinear characteristics. In order to ensure the safe and reliable operation of the engine under all operating conditions, while realizing its full performance potential, engine control systems have evolved over the past few decades and have been able to diagnose faults and determine the health state of the engine online [

1,

2]. Advanced control and fault diagnosis systems need to obtain all kinds of state information of engine accurately in real time. However, due to many reasons such as space, structure and material, the parameters that can be measured directly by sensors are very limited. In order to solve this contradiction, on-board engine model technology has been put forward, and has been paid attention to by many scholars and engineers in the past decades.

There are many challenges to be overcome in order to track the engine state accurately in real time. Aero-engine is a strong nonlinear aero-dynamic, thermal and mechanical equipment with wide operating envelope. Across the whole operating envelope, the engine characteristics will change significantly. Throughout the life of the engine, due to blade corrosion, erosion, wear, combustion characteristics change and other reasons, engine components will slowly decline, and the overall characteristics of the engine gradually deviate from its initial state. The change of the power and air flow extracted from the engine will cause the engine behavior to deviate from the preset state. Meanwhile, engine characteristics can be suddenly changed due to faults, FOD (Foreign Object Damage) and other unexpected events. Finally, the cleaning of engine components during service, planned maintenance, and component replacement can partially restore engine performance [

3]. Aero-engine on-board model usually can only represent a nominal state of a certain type of engine, it’s difficult for the model to accurately reflect all changes caused by factors mentioned above.

In order to improve the tracking accuracy of aero-engine on-board model, a lot of research work have been done. In 1989, R. H. Luppold [

4] proposed STORM (Self Tuning On-board Real-time Model), which used linear model and Kalman filter to estimate the performance parameters of engine components, so that the on-board model could track the performance changes of engine components and improve the model accuracy. From 2003 to 2008, Volponi et al. [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9] proposed that based on the self tunning on-board model, the output parameters of the piecewise linear model were modified by neural networks, that’s eSTORM (enhanced Self Tuning On-board Real-time Model). The training set of the neural networks was generated by real-time Gaussian clustering algorithm. Finally, eSTORM was verified on the PW6000 commercial engine. eSTORM introduces the data-based modeling method on the basis of the model which based on physical mechanism. Many scholars continue to improve the on-board model along this technical route. Lu et al. [

10] from Nanjing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics adopted LPV (Linear Parameter Varying) model instead of PL (Piecewise Linear) model, at the same time, Lu replaced Neural Network with IR-KELM (Independent Reduction Kernel Extreme Learning Machine). IR-KELM divides the engine real-time data samples into training set B and constraint set P. The training set is used to train the neural network directly, and the constraint set is used to modify the network. Li et al. [

11] adopted a neural network to predict the steady state part of the on-board engine model. The training data of the neural network comes from the component-level nonlinear engine model simulation. Meanwhile, the similarity criterion is used to compress the training set, which improves the training speed. Zheng Qiangang [

12] used the MGD (Mini-batch Gradient Descent) method to train neural networks, which improves the training efficiency, meanwhile added a penalty item, which is the sum of weights in each layer, to the objective function to prevent overfitting in training. Zheng [

13,

14] also used deep neural networks to fit the nonlinear characteristics of aero-engine for improving the model tracking accuracy. Zhao et al. [

15] designed the thrust estimator with particle swarm core extreme learning machine, which improved the accuracy and speed of thrust estimation. Xiang et al. [

16] adopted the fusion method of neural network and propulsion system matrix to build a self tunning on-board model, which improves the average accuracy of the model under large operating envelope and multiple states.

In the above research work, the differences between the data samples produced by aero-engine in different health states were not discussed. In fact, an engine that has experienced component performance degradation will consume more fuel, produce higher turbine exhaust temperature, and exhibit higher unit fuel consumption than a brand new engine to achieve the same control objectives (such as low pressure rotor speed) under the same engine control system. These characteristic differences, through real-time sampling, will produce different data sets. If these data sets are used indiscriminately to train the on-board neural networks, no matter whether these neural networks are used for output compensation or for representing component characteristics, "confusion" will be introduced, resulting in accuracy reduction and even non-convergence of the training process.

This paper presents an algorithm for generating a qualified training set for neural networks based on separability index and reverse searching of database elements. The algorithm searches and adds the database elements to a subset in reverse order of GMM (Gaussian Mixture Model) database, and calculates the separability index of the data subset. When the separability index exceeds the preset threshold value, the search stops, and the final data subset is used as the training set of the neural networks. This algorithm eliminates the elements in the database that no longer represent the current health state of the engine, improves the training accuracy of the neural networks, and also increases the training speed by reducing the training samples.

The major structure of this paper is as follows. The section 1 is introduction.

Section 2 introduces the eSTORM model architecture and the algorithms of each sub-module.

Section 3 simulates the engine component degradation process and analyzes the reasons for the accuracy reduction of neural network compensation. In section 4, the separability index and reverse searching algorithm are introduced.

Section 5 represents the effect of the proposed method through simulation.

Section 6 discusses the possible application of separability index and reverse searching algorithm in engine gas path monitoring, and

Section 7 is the conclusion.

2. eSTORM and GMM

2.1. eSTORM Structure

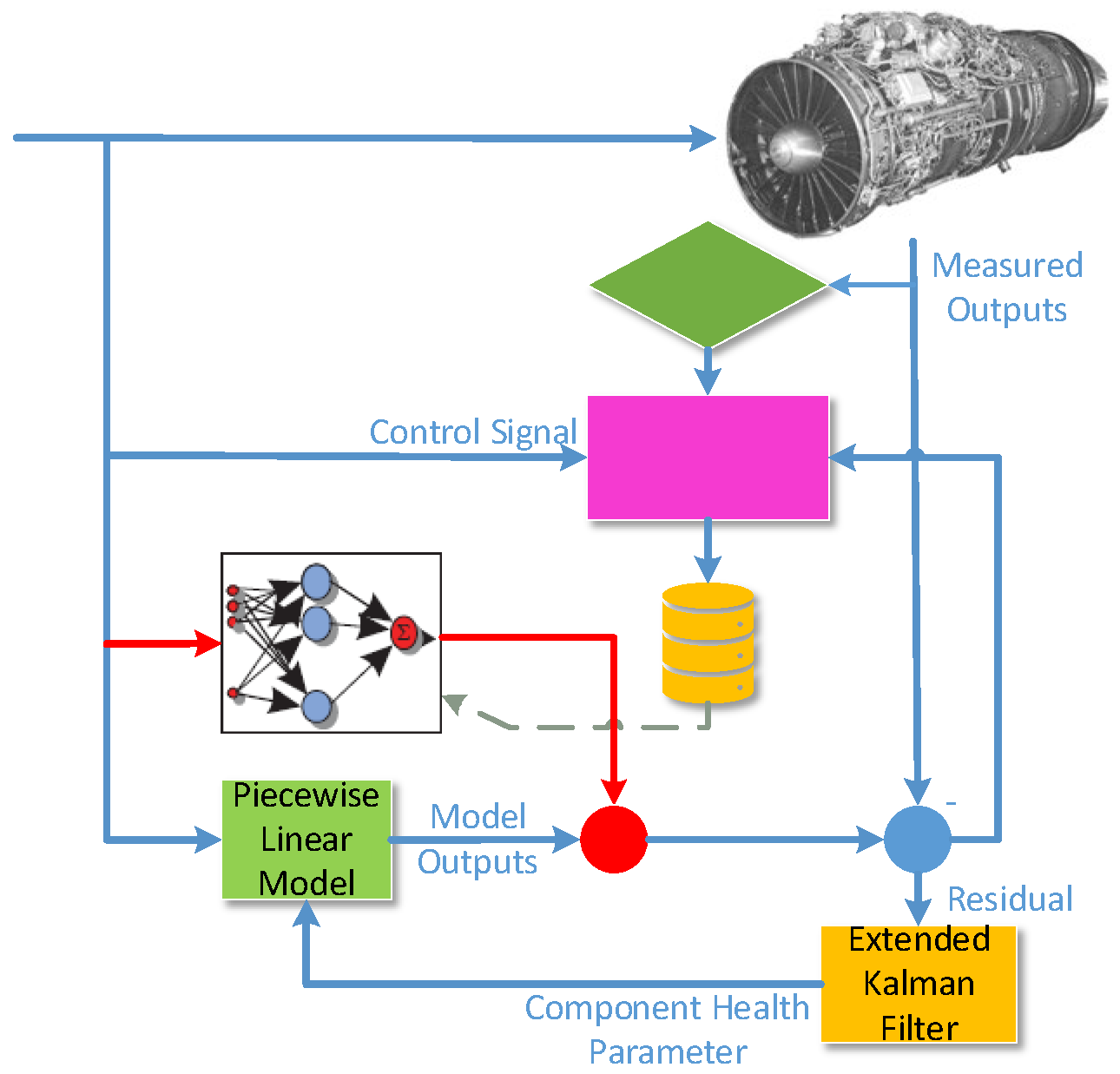

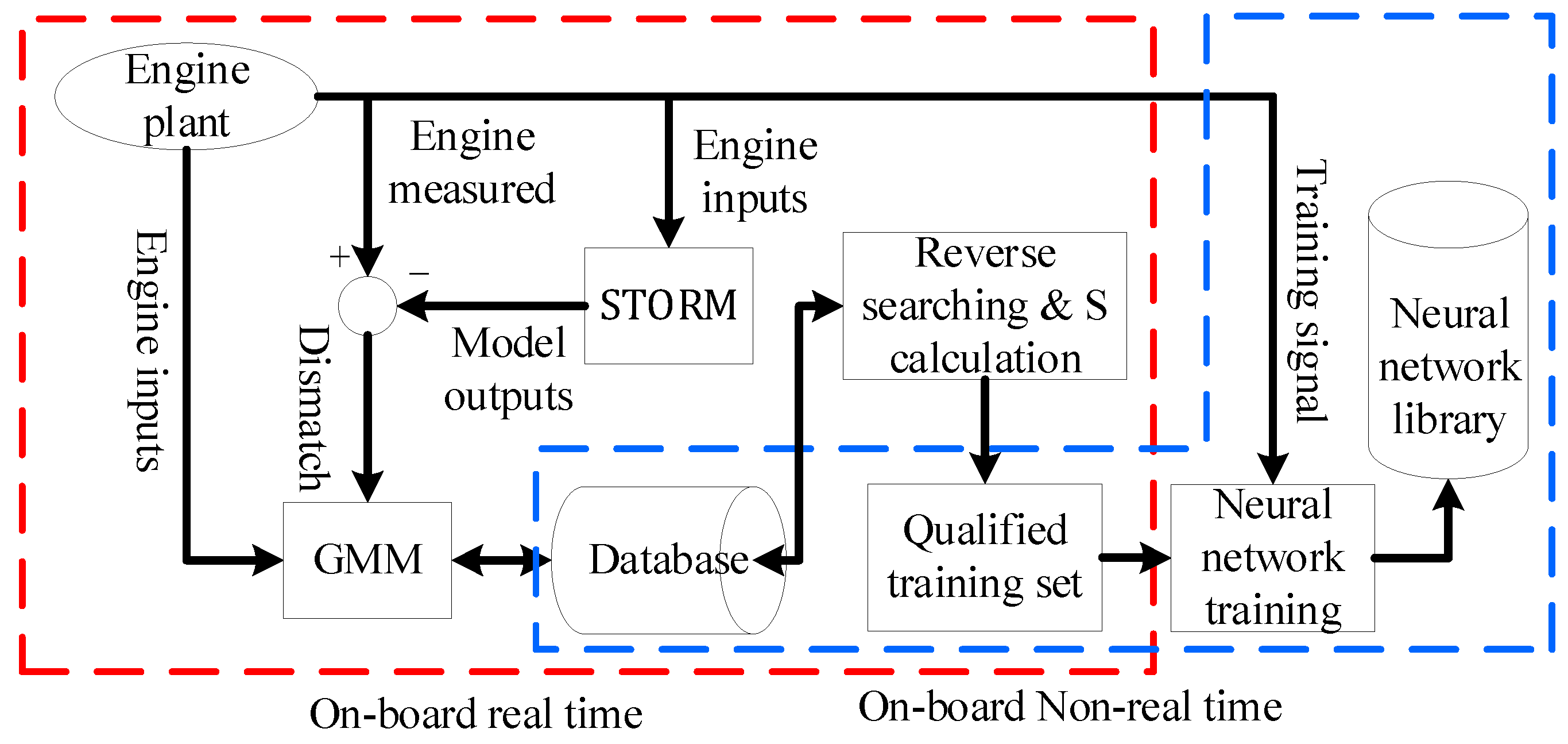

The eSTORM architecture, proposed by Volponi et al on the basis of STORM architecture, includes piecewise linear model, extended Kalman filter, GMM module which includes real-time clustering algorithm and database, and neural network units. The eSTORM architecture is represented in

Figure 1.

In

Figure 1, the piecewise linear model represents the behavior of the engine near the steady-state operating point. The piecewise linear model is scheduled in entire engine operating envelope, and the scheduling parameters usually include environmental parameters (altitude, Mach number) and engine state parameters (low pressure rotor speed, nozzle throat area, etc.). The residuals between the piecewise linear model outputs and the engine measurable outputs are sent to the Kalman filter, which estimates the engine state parameters, including component health parameters. The component health parameters are fed back to the piecewise linear model, and the model outputs are modified to approximate the real engine output values.

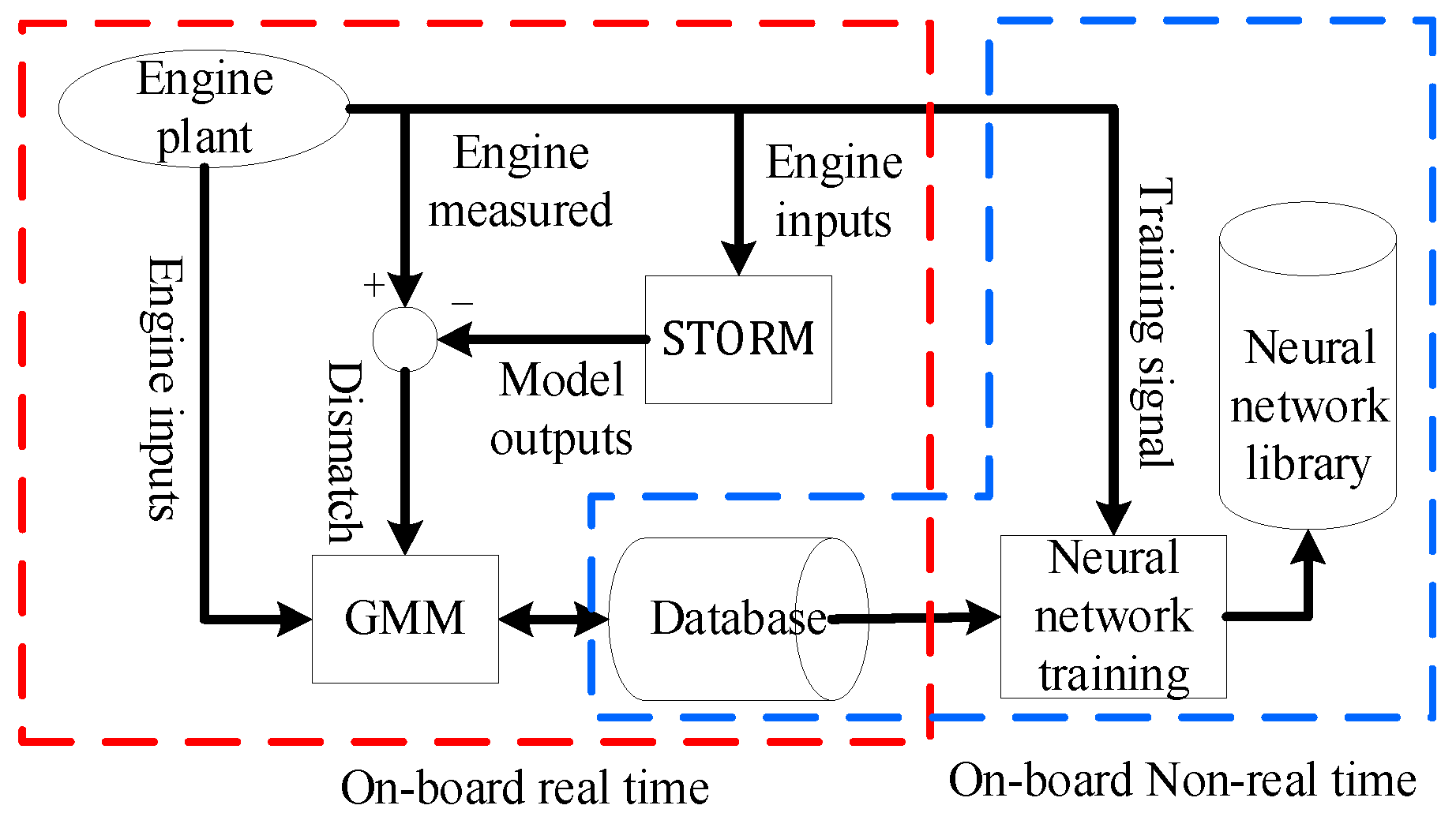

Due to underdetermined estimation, unmodeled dynamics, different engine operating conditions and other reasons, there are still inevitable output residuals between the modified piecewise linear model and the real engine. These residuals and engine control inputs are sent to the GMM module to form a database through Gaussian clustering process. The elements in this database represent the degree of mismatch between the on-board model and the real engine under different environmental and operating conditions. At the end of each flight cycle, the neural networks are trained using the newly formed database as training set. The trained neural networks can compensate the outputs of the on-board model according to the current engine environmental and operating conditions, further improve the tracking accuracy and the individual adaptability of the model. The working process of eSTORM is represented in

Figure 2.

2.2. GMM Module and Algorithm

The GMM module collects the control inputs and output differences between the on-board model and the real engine in real time, and determines whether there are elements with similar characteristics in the database. If there are no data elements that represent the current engine characteristics, the GMM module starts a new clustering process and adds a new data element to the database.

The GMM module uses the Mahalanobis distance to compare the "similarity" between the sampled data at the current time and the database elements. The definition of Mahalanobis distance is shown in Equation (1).

where

indicates Mahalanobis distance;

denotes the sample data at the current time, including control inputs and discrepancy between model and engine outputs;

denotes the elements that have already been in the database;

indicates the length of data vector;

denotes the mean value of

while

standard deviation;

refers to the noise sensitive factor of the

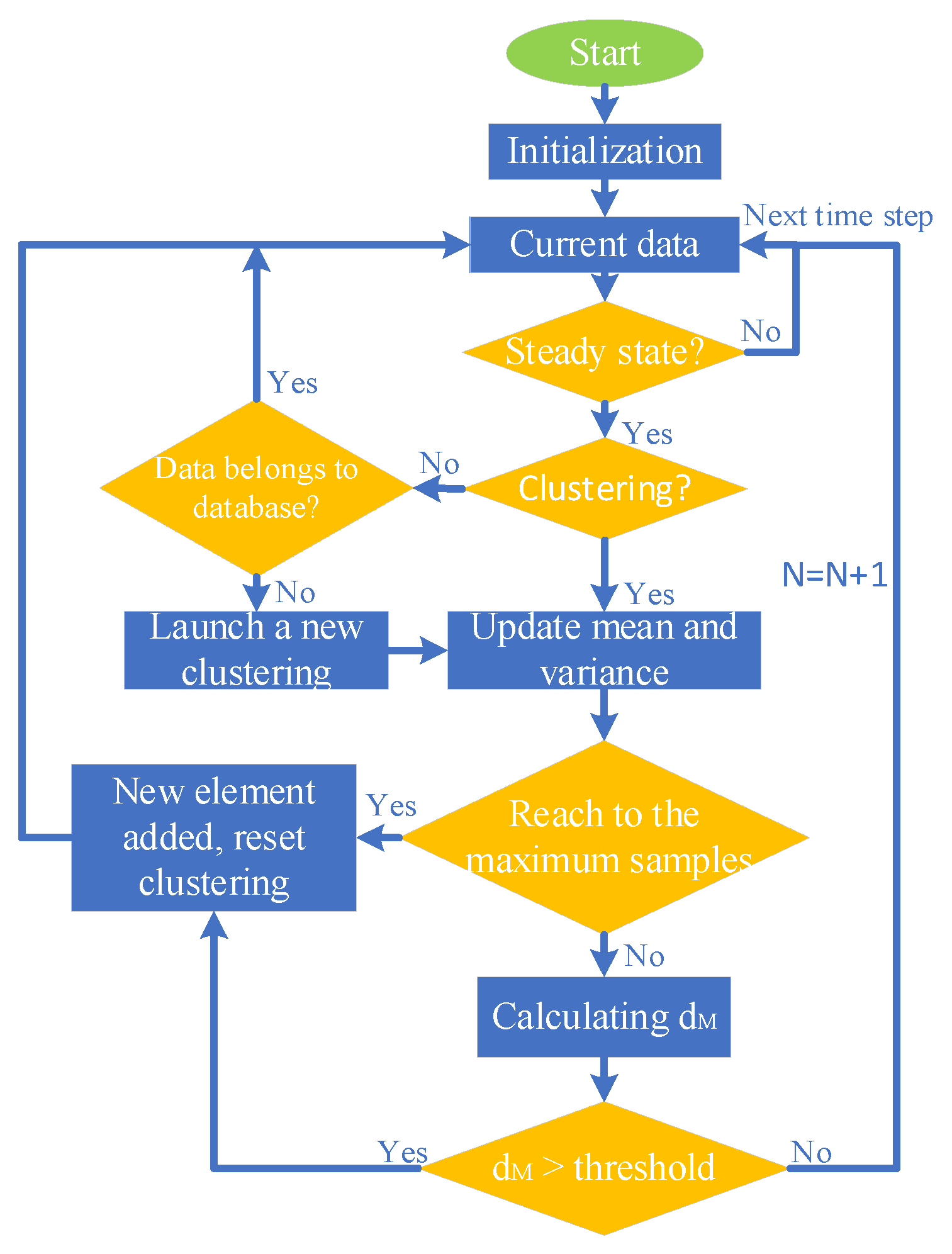

th data element. The GMM calculates the Mahalanobis distance between the sampled data at the current time and all database elements, and if the smallest distance is still greater than the preset threshold, a new clustering process is launched. The clustering program calculates the mean and standard deviation of the control inputs and output residuals in a certain operating period to construct a new element. In this paper, the GMM module only processes the data of steady-state, so before calculating the Mahalanobis distance, it is necessary to determine whether the engine is in steady-state condition. The flow chart of Gaussian clustering algorithm is shown in

Figure 3.

In

Figure 3, the GMM module uses a real-time algorithm to update the mean and standard deviation of the sampled data. The calculation formula of mean and standard deviation are shown in Equation (2).

where

denotes the mean value of clustering process at the current time step, and

denotes the value at previous time step;

denotes the standard deviation at the current time step, and

denotes the value at previous time step;

denotes the number of samples;

indicates the index of element in data vector;

indicates the number of vector elements.

More detailed descriptions of Gaussian clustering algorithm can be found in literature of Volponi [

8] and Sun [

17].

2.3. Neural Networks and Training Algorithm

The neural networks in eSTORM are used to compensate the discrepancies between outputs of the model and the real engine under different engine operating conditions. The neural networks adopt a multi-layer perceptron structure, involving 1 hidden layer. The number of hidden layer nodes is 9 in this paper and can be adjusted according to application situation. For avoiding coupling effect between parameters, every neural network has just one single output node, and each network only compensates one output parameter. The activation function is symmetric Sigmoid function, and is shown in Equation (3).

The cost function of neural network training is Mean Squared Error function:

where

refers to cost function;

indicates the output value of samples;

indicates the actual output value in forward calculation;

denotes number of samples;

denotes sample index. In this paper, Back Propagation training algorithm with momentum item is adopted, as shown in Equation (5).

where

denotes the weight to be corrected,

denotes iteration number,

denotes weight correction item;

denotes learning rate;

indicates momentum item; and

indicates coefficient of the momentum item.

.

3. Problem

The total life of aero-engine can usually reach thousands of hours, and civil engines can reach up to 20,000 to 30,000 hours. In the long service life of the engine, with the increase of service time and number of flight cycles, the overall performance of the engine will degrade due to corrosion and erosion of the rotor blades, changes in the working efficiency of the combustion chamber, wear of the bearing components, and the decline in the efficiency of the heat exchange components.

It can be seen that the database generated by Gaussian clustering algorithm will store all data samples of the engine from the initial service state to the current state, and these data represent the characteristics of the engine in different health states. As engine service time increases, the components continue to degrade, and the number of elements in database grow gradually. For example, with the degradation of the high-pressure rotor, the engine can still reach the preset rotor speed under the regulation of the control system, but it will produce lower Pt3, higher Tt6 and SFC, and smaller thrust. As the pressure/temperature signal at each engine cross-section changes, the Mahalanobis distance between the sampled data and the existing elements in database increases gradually. When this distance exceeds the preset threshold, a new clustering process is launched and new element generated.

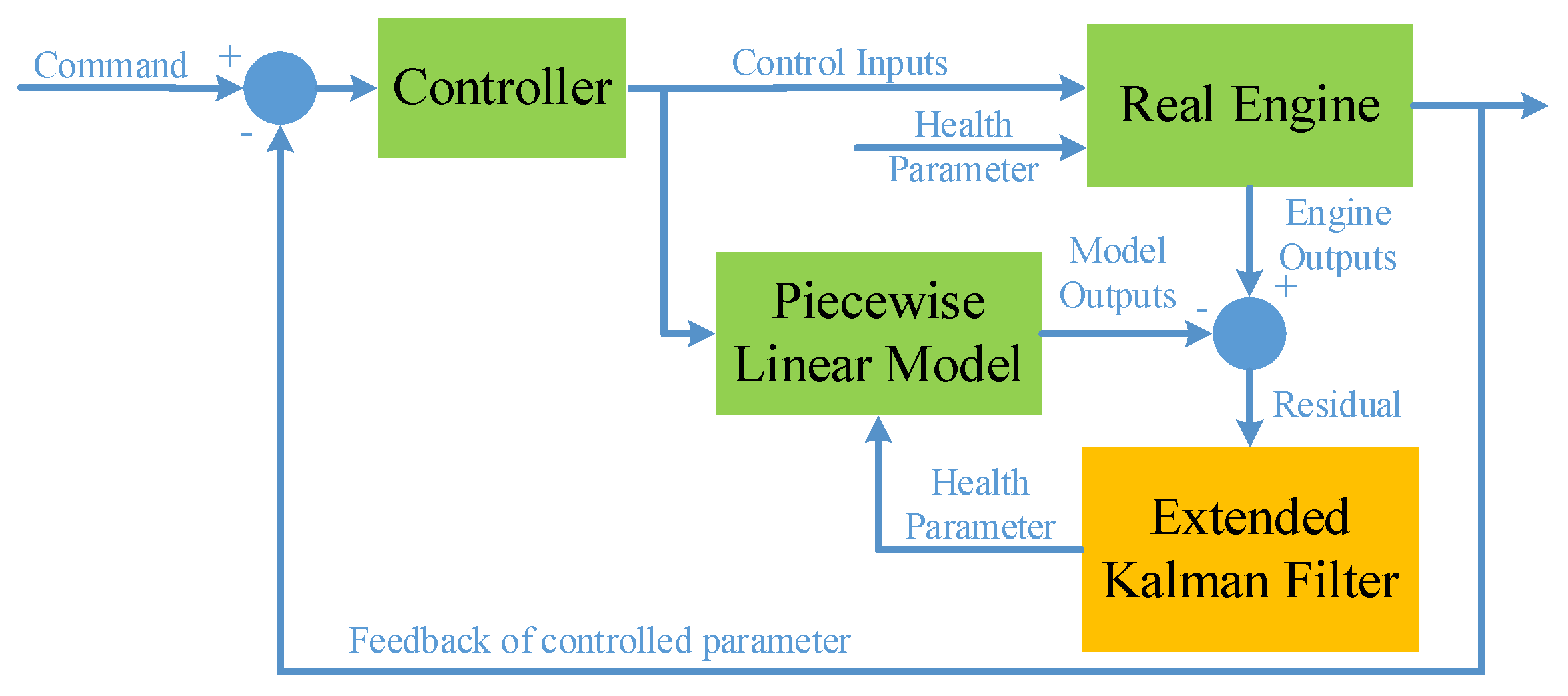

3.1. Illustration of Simulation Model

For illustration, the engine control system and self-tunning on-board model are designed in Simulink environment, and the performance degradation process of fan, compressor, high pressure turbine and low pressure turbine is simulated. The diagram of engine and control system is shown in

Figure 4.

In

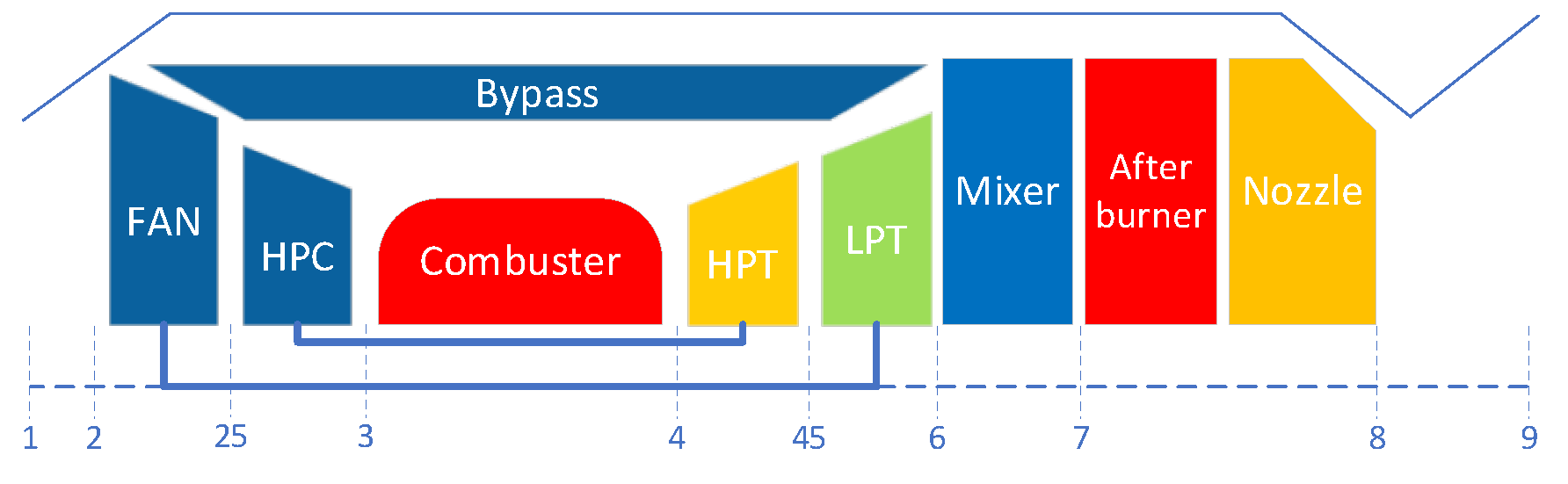

Figure 4, the real engine is a component level nonlinear model of a low bypass ratio two-rotor turbofan engine, which can accurately reflect the operation of the real engine in full operating envelope. The diagram of engine structure and cross-section definition is shown in

Figure 5.

In

Figure 5, the engine control variable is wfm, environmental parameters are Alt and Ma, the measurable output variables are N1, N2, Tt25, Tt3, Tt6, Pt25, Pt3 and Pt6. In addition, the component level model has the inputs of component health parameters, which can adjust the level of component degradation. The model contains 8 component health parameters, which are FanEffDe, FanWaDe, ComEffDe, ComWaDe, HPTEffDe, HPTWaDe, LPTEffDe and LPTWaDe respectively. All the health parameters range from 0 to 3%, while 0 indicates that the component is not degraded at all, and a larger value indicates that the engine component is degraded more seriously. The value of more than 3% is not practical, because the remaining useful life of the components in this state have been almost exhausted [

18].

The piecewise linear model in

Figure 4 is obtained by linearizing the component-level nonlinear model near its steady-state operating point. When the engine is transitioning from one operating point to another, the linear model will schedule within the operating envelope according to the environmental conditions and operating states. The extended Kalman filter is obtained from the linear model parameters. It should be noted that due to the limitations of engine structure and space, the number of sensors installed on the engine is usually less than the health parameters that need to be estimated, which will introduce the problem of underdetermined estimation. In the model presented in this paper, the temperature and pressure sensors are set at the 25, 3 and 6 sections of the engine, and there are a total of 6 measurable parameters, so for the 8 component health parameters, the Kalman filter only estimates 6 of them, which are efficiency and mass flow decay factor of fan, compressor and low pressure turbine. Detailed illustrations for generating engine linear model and solving Kalman filters can be found in literature of Lu [

19,

20]. The controller in

Figure 4 is a classic PID controller, the controlled variable is the engine low-pressure rotor speed, and the control output is the main fuel mass flow.

3.2. Simulation Settings and Results

Simulation settings are as follows, altitude is 4km, Mach number is 0.8, and engine accelerates from 70% to 100% of N1 under the control system. The simulation is carried out repeatedly under the above conditions, and in the process, the degradation level of each engine component is gradually increased, and the change of engine output variables are observed. However, the performance degradation of aero-engine components in long-period is affected by many factors, such as manufacturing technology of components, fabrication of the engine, operating environment, and level of maintenance. It is very difficult to accurately reconstruct the performance degradation trend of the main components of engine in the simulation environment. According to G. P. Sallee [

21], the performance degradation process of engine components is generally linear with the number of engine working cycles. In this paper, the health parameters of each component are set to increase linearly with the simulation cycles, increasing by 0.1% for each cycle until the health parameters degrade by 3%.

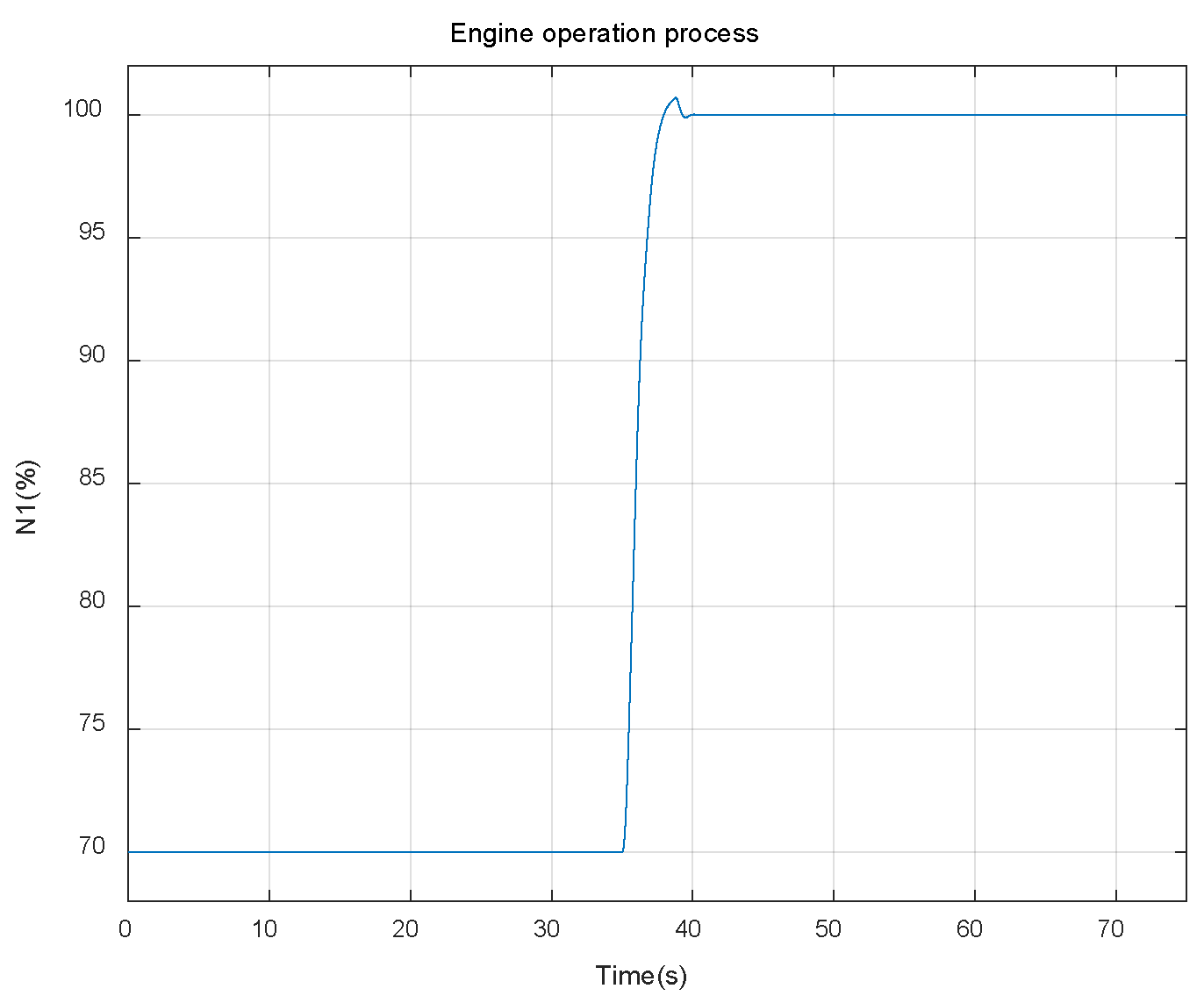

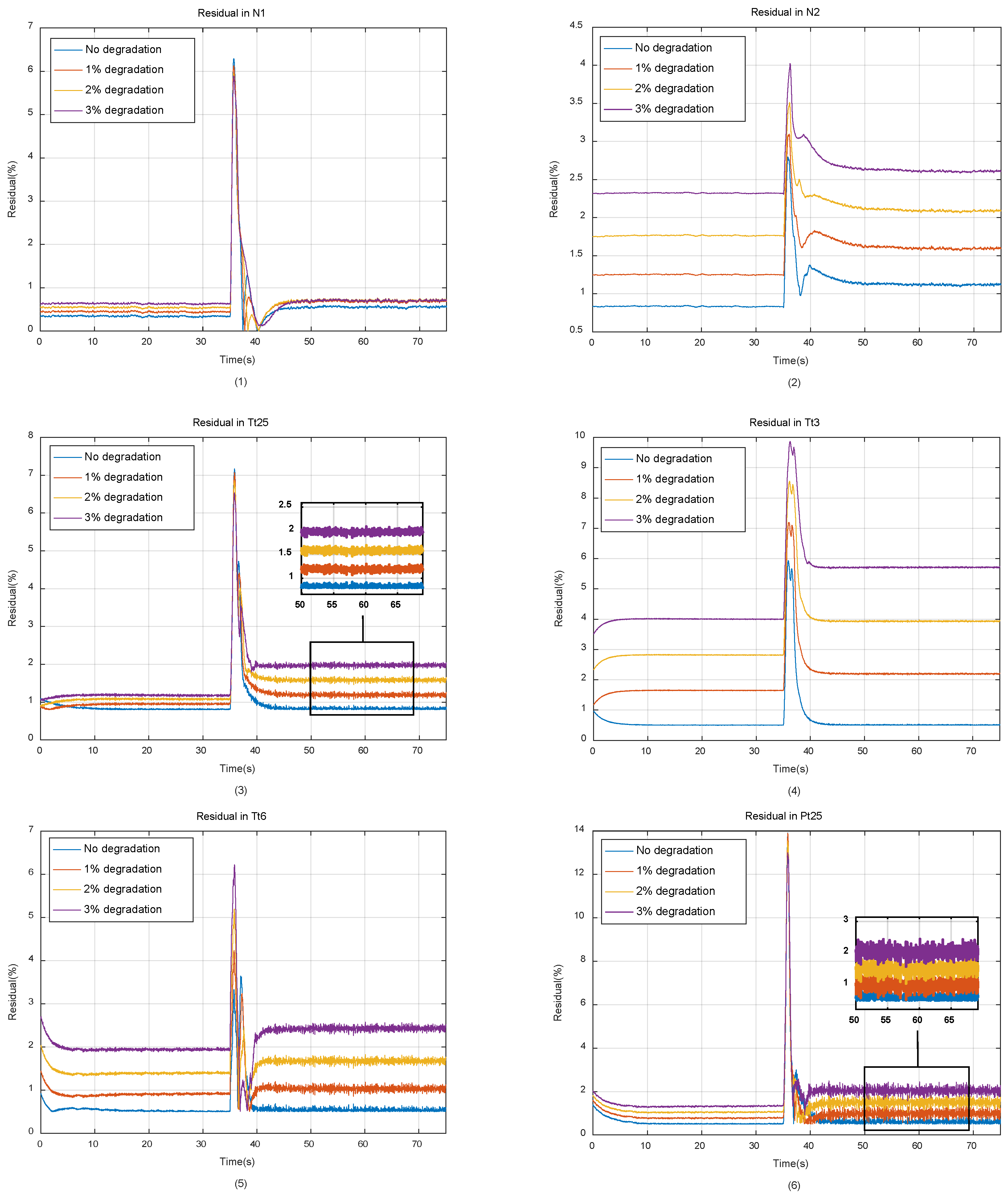

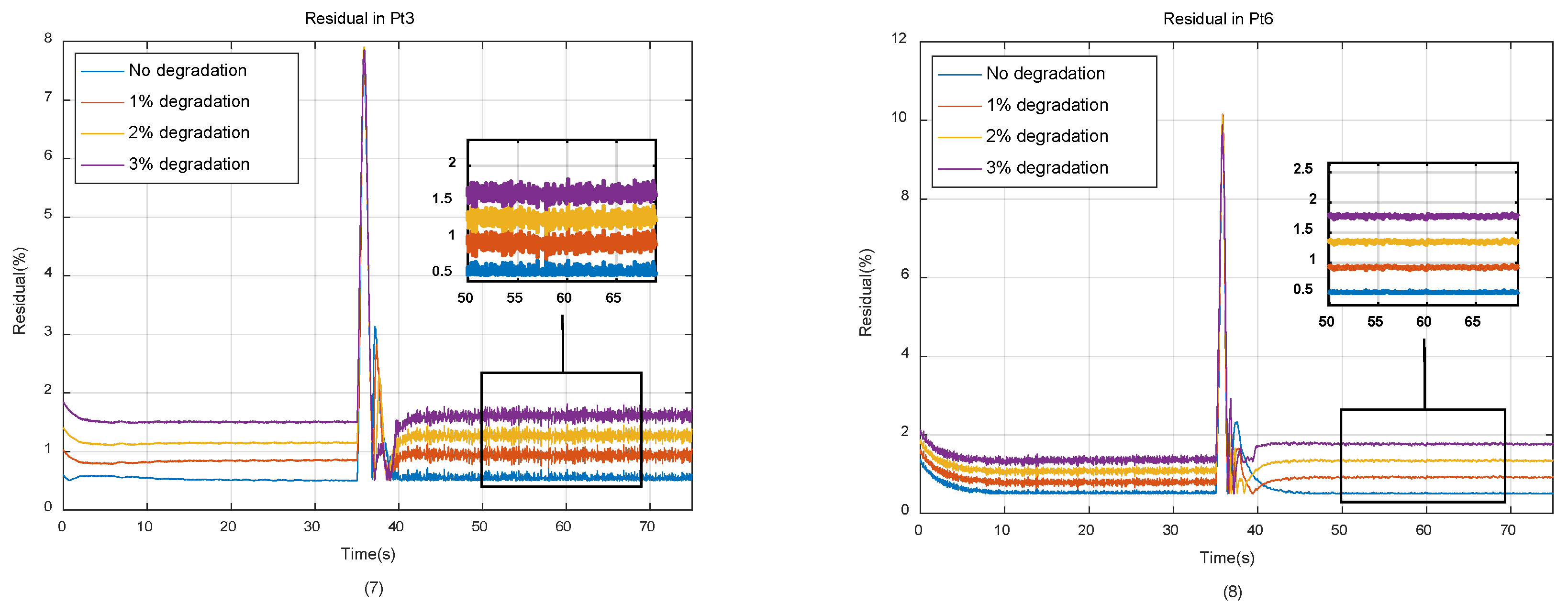

The operation process of engine during one simulation cycle is shown in

Figure 6. The residuals between the outputs of self-tunning on-board model and the real engine under different degradation conditions are shown in

Figure 7.

As can be seen from

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, with the degradation of engine component performance, the output residuals between the model and the real engine will gradually increase, which caused by underdetermined estimation, reducing the tracking accuracy of the model. It should also be noted that since the simulation is carried out under closed-loop conditions, the accuracy of the controlled variable N1 is guaranteed by the PID controller, so it’s less affected by the performance degradation of the engine components.

According to the on-board real-time clustering algorithm described in

Section 2.2, all of the historical data will become element of GMM database if their Mahalanobis distance from each other exceeds the preset threshold. On an engine that has been in service for a long time, when all the elements of the database are used to train the neural networks, those elements generated earlier, which can no longer represent the current characteristics of the engine, will interfere with the training process, reduce the compensation accuracy of the neural networks, and make the training process nonconvergent in severe case.

3.3. Influence of Historical Data on Neural Network Training

Let

be the neural network to be trained, and

be the training set. Let

denote the number of samples,

denote the sample input, and

indicates the sample output. Then according to the neural network cost function shown in Equation (4), the mathematical expression for training the neural network is as follows:

Let also , that is, there are only 2 training samples, , and . Then after simple calculation, we can find that in order to minimize E, will be the solution, and the minimum value of is . That is, if there are two training samples with the same input value, but the discrepancy of the output value is , is the highest training accuracy that the cost function can achieve. If increases, the training accuracy decreases. If increases so that exceeds the preset threshold, the training process cannot converge. The situation is similar for more training samples.

As can be seen from the simulation results in

Section 3.2, due to the degradation of engine components, a series of samples with similar input values (control variables) but discrepant output values will be added to GMM database under the same steady-state operating condition. According to the above analysis, it can be seen that this will affect the tracking accuracy of neural networks, and even make the training process nonconvergent in serious cases.

4. Separability Index and Algorithm

In order to mitigate the influence of historical data on the training process and improve tracking accuracy of neural networks, Xu proposed a method to introduce memory factors into training samples. Letting

be the memory factor,

, then the samples are formulated as:

where

denotes the samples of a certain time batch,

denotes the batch index. As can be seen from Equation (7), the earlier the sample is formed in the database, the larger

is, so the smaller its memory factor is [

22]. This method reduces the influence of historical data on the training process of neural networks, but does not clearly define the batch of samples. If the gradually degradation and sudden changes due to faults are both taken into account,

needs to be optimized.

In this paper, referring to the literature of David L. Davies [

23] and James C. Bezdek [

24], a method is proposed to improve the quality of training sets of neural networks based on separability index and reverse search algorithm. The mathematical definition of separability index is as follows.

Let

be a set of n feature vectors in p-space, then the separability index of

is defined as:

where

denotes separability index,

denotes number of elements in the data set,

denotes element of the data set. The subscript

indicates index of element in the data set, while

indicates index of component in the element.

can be selected according to the situation. If

, then

represents the average Euclidean distance; if

, then

represents the mean square error. In this paper,

is adopted.

in Equation (8) denotes the center of the data set

, and its definition is as follows:

The separability index is the mean square error between all elements in a data set and its center, and can be used to represent how dispersed the elements of a data set are. The more dispersed the data set elements are, the larger the is.

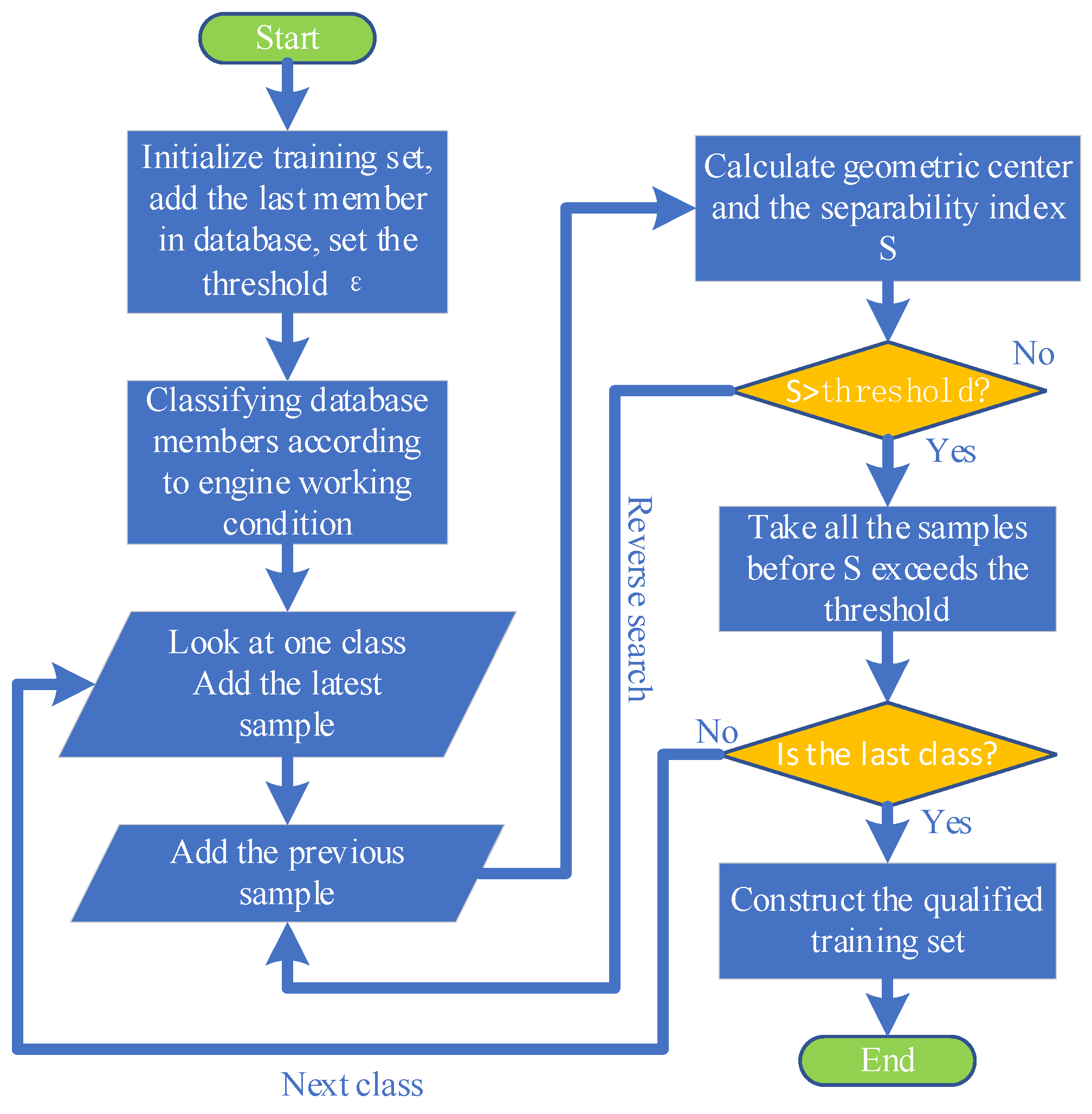

The GMM module determines whether new data elements need to be generated in each flight cycle of the engine, and all database elements are arranged in the order of generation. Since the data elements are obtained under multiple steady-state conditions, it is necessary to classify the data according to engine operating conditions first, and then the algorithm searches in reverse order in each class to ensure that newer elements can be added to the training set. Finally, the separability index of each class of data is calculated respectively, and the qualified data in all classes are added to the training set. The algorithm flow chart for generating qualified training set of neural networks is shown in

Figure 8.

By introducing the separability index

and reverse searching, the original workflow of eSTORM model is changed, and the new workflow of eSTORM is shown in

Figure 9.

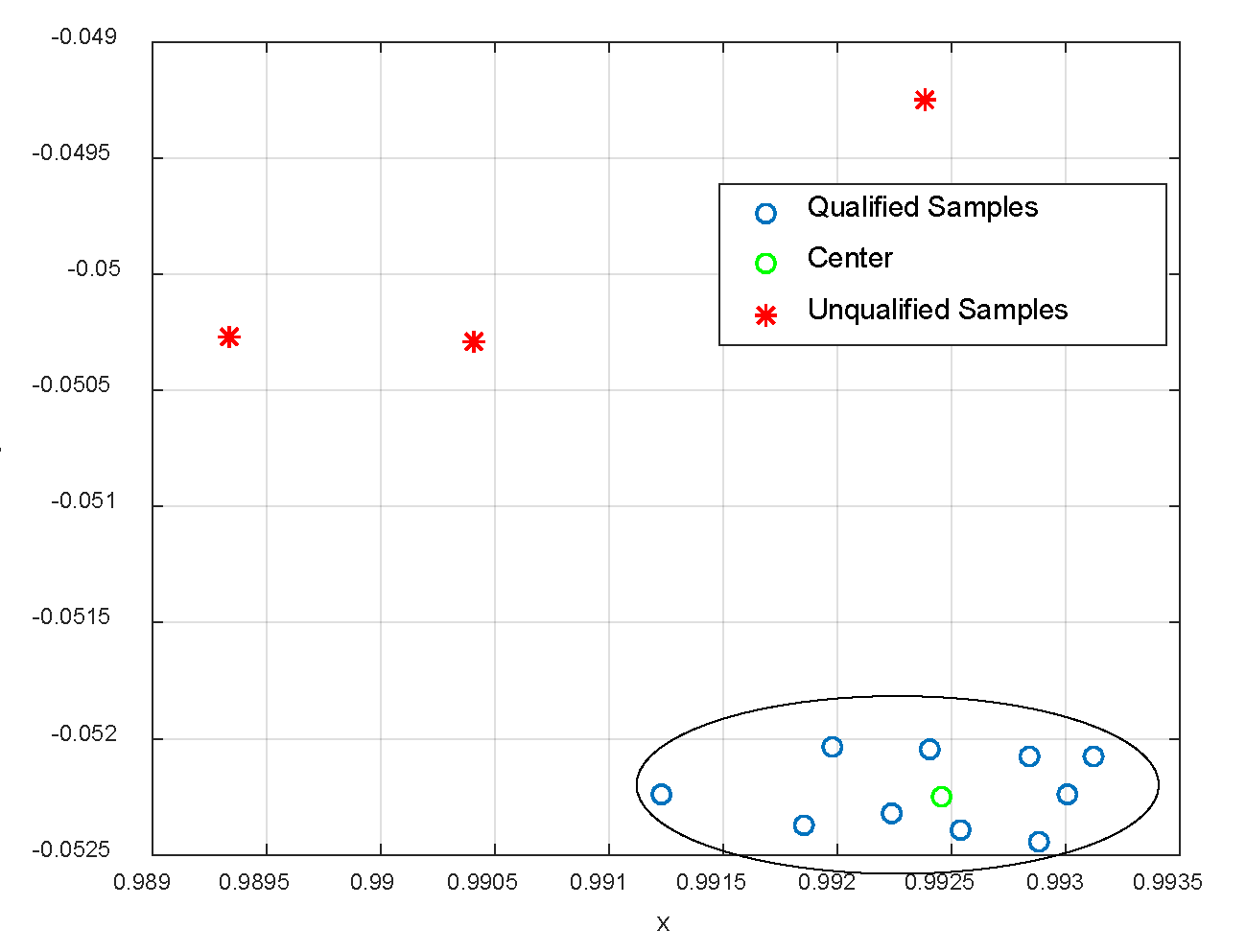

A qualified training set generated under 100% engine operating conditions is shown in

Figure 10. In the figure, the X-axis is the normalized main fuel flow, and the Y-axis is the Tt3 output residual.

The method of using separability index and reverse search algorithm to generate qualified training set of neural networks has the following advantages:

- 1)

This method can completely eliminate those samples formed earlier in the database that can no longer represent the current state of the engine, and only retain the newer samples, improve the tracking accuracy of the neural network, and make the training process always converge.

- 2)

By comparing the definition of the separability index in Equation (8) with the cost function of the neural network in Equation (4), it can be found that they are very similar in mathematical form, so the threshold of the separability index can be set according to the cost function of the neural network.

- 3)

The algorithm is relatively simple for implementation. As shown in

Figure 9, the algorithm can run in the on-board environment in real time.

- 4)

Finally, because the qualified training set is a subset of the database which generated by GMM module, the number of training samples is reduced, and the training speed of the neural network is improved.

5. Simulation and Comparison

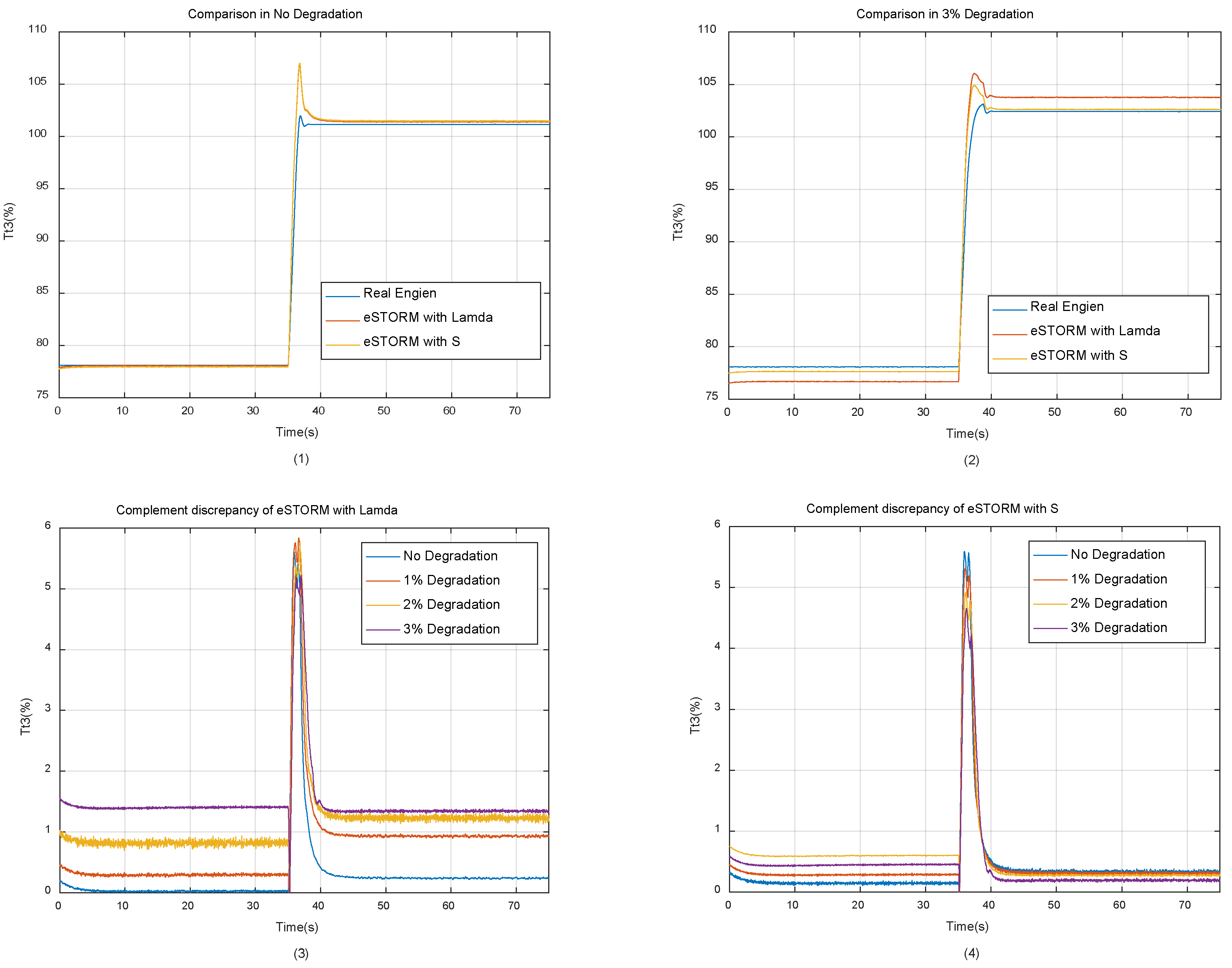

In this section, under the same simulation settings as in

Section 3.2, eSTORM using memory factor

and separability index

is simulated respectively, and the tracking accuracy of both is compared in the end. In order to ensure that the neural networks trained by the two methods has a good compensation accuracy, the memory factor is set to 0.6(training non-convergence may occur above 0.6), and the threshold value of separability index is set to 10

-6 order of magnitude, higher than the accuracy of the cost function of the neural network. The comparison of Tt3 variable obtained by simulation is shown in

Figure 11.

In

Figure 11, (1) is the working process of engine without degradation. As can be seen from the figure, at this time, since there are only data elements represent a brand new engine in the database, the eSTORM model using memory factor

and separability index

can both track the engine output variables accurately. (2) refers to the working process of the engine under 3% degradation condition. (3) and (4) show the tracking errors of eSTORM using the two methods under different degradation conditions respectively. As can be seen from the figure, as the engine degradation evolves, the tracking accuracy of eSTORM using memory factor

decreases, while that using separability index

remains high under different health conditions. The comparison of tracking errors of all output variables under 100% operation condition is listed in

Table 1.

As can be seen from

Table 1, in general, the eSTORM with memory factors

can ensure the convergence of training process of neural networks, thus improving the tracking accuracy of the model, but it is still affected by the early database elements. It can also be seen that the model with separability index

not only guarantees the training convergence of neural networks, but also has high tracking accuracy because it is not affected by early elements. Finally, it should be noted that since the self-tunning on-board model works under control in a closed-loop system, the accuracy of controlled variable N1 is guaranteed by the PID controller, so it is not listed in

Table 1.

6. Discussion of Separability Index in Engine Gas Path Monitoring

The separability index can be used not only to generate qualified training set, but also to monitor engine gas path parameters.

Each component of the center

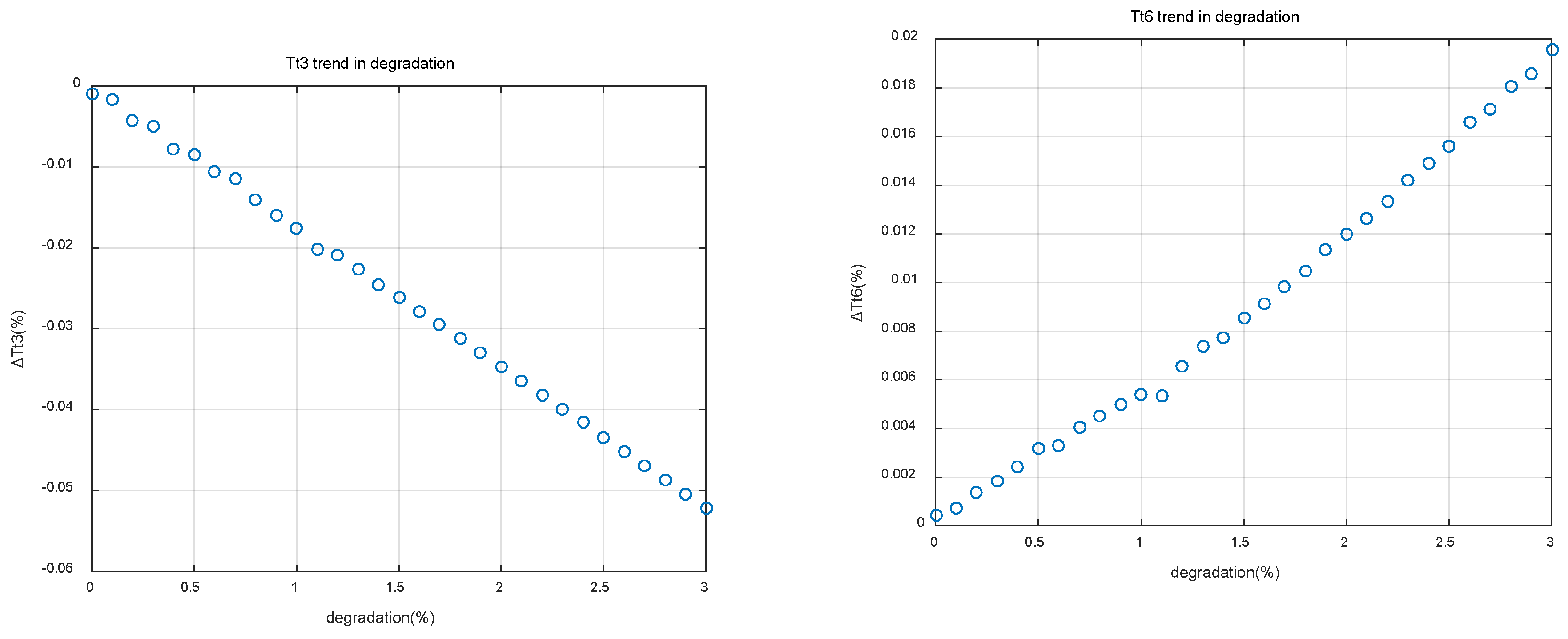

, which calculated from Equation (9), represents the short-term average of residual of a temperature or pressure variable over a period of time. By looking at all of this series of short-term averages, it is possible to obtain the tendency of engine output variables to deviate from their nominal state. The data center evolution trends of Tt3 and Tt6 residual are shown in

Figure 12.

In

Figure 12, the amplitude and trend of an output variable deviating from its nominal value can be observed directly, and then the decision can be made whether there is an anomaly or fault. If a sensor drift fault occurs, a sudden change point will be produced in the corresponding tendency chart.

Compared with the traditional sliding window method for gas path monitoring [

25,

26], the method of using separability index and reverse searching in database has the following advantages:

- 1)

After the Gaussian clustering process of eSTORM, the original gas path parameters of engine have formed a database containing all steady-state operating points, and the influence of noise in system and measurement are mitigated. The data set constructed by using separability index and reverse searching represents the current state of the engine. Therefore, the monitoring of parameter trends does not require additional calculations.

- 2)

Because the data samples are compressed in time dimension, there is no problem of low algorithm efficiency caused by too few abnormal samples in sliding window method.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, aiming at the influence of early data in the GMM database on the training process and tracking accuracy of neural networks, a method based on separability index and reverse search algorithm is proposed to construct a qualified training set, and its feasibility is verified by simulation. Some conclusions are as follows:

- 1)

This method eliminates the influence of those early data elements in the database, which can no longer represent the current health state of the engine, and ensures the convergence of the training process of the neural networks.

- 2)

Compared with the method of introducing sample memory factors, this method makes the on-board model maintain higher tracking accuracy during the whole service life of the engine.

- 3)

The algorithm of reverse search and construction of qualified training set can run in real time, and the algorithm is simple for implementation. In addition, the training speed of neural network is also improved due to fewer training samples.

- 4)

Finally, the intermediate result obtained when calculating the data set separability index, namely the data set center, can be used for engine gas path monitoring. Compared with the traditional sliding window method, this method avoids the problem of low algorithm efficiency caused by fewer abnormal samples.

Nomenclature

Alt Altitude

ComEffDe High pressure compressor efficiency degradation factor

ComWaDe High pressure compressor mass flow degradation factor

dM Mahalanobis distance

FanEffDe Fan efficiency degradation factor

FanWaDe Fan mass flow degradation factor

Ma Mach number

HPC High pressure compressor

HPT High pressure turbine

HPTEffDe High pressure turbine efficiency degradation factor

HPTWaDe High pressure turbine mass flow degradation factor

LPT Low pressure turbine

LPTEffDe Low pressure turbine efficiency degradation factor

LPTWaDe Low pressure turbine mass flow degradation factor

N1 Low pressure rotor speed

N2 High pressure rotor speed

Pt25 Total pressure at the inlet of high pressure compressor

Pt3 Total pressure at the inlet of combuster

Pt6 Total pressure at the outlet of low pressure turbine

SFC Specific Fuel Consumption

S Separability index

Tt25 Total temperature at the inlet of high pressure compressor

Tt3 Total temperature at the inlet of combuster

Tt6 Total temperature at the outlet of low pressure turbine

Center of dataset

wfm Main fuel flow

λ Sample memory factor

References

- Mattingly, J.D.; Jaw, L.C. , Aircraft engine controls: design, system analysis, and health monitoring. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics: Reston, VA, 2009; p 361.

- Richter, H. , Advanced control of turbofan engines. Springer: New York, NY, 2012; p 266.

- Wei, Z.; Zhang, S.; Jafari, S.; Nikolaidis, T. , Gas turbine aero-engines real time on-board modelling: A review, research challenges, and exploring the future. Prog Aerosp Sci 2020, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luppold, R.H.; Roman, J.R.; Gallops, G.W.; Kerr, L.J. , In Estimating in-flight engine performance variations using Kalman filter concepts, Joint Propulsion Conference, 1989.

- Brotherton, T.; Volponi, A.; Luppold, R.; Simon, D.L. , In eSTORM: Enhanced self tuning on-board real-time engine model, Aerospace Conference, Montana, 2003; Montana, 2003.

- Volponi, A.; Brotherton, T. , A bootstrap data methodology for sequential hybrid engine model building. In 345 E 47TH ST, NEW YORK, NY 10017 USA, 2005; p 9.

- Volponi, A.J. , USE OF HYBRID ENGINE MODELING FOR ON-BOARD MODULE PERFORMANCE TRACKING. In Reno, Nevada USA, 2005; pp 992-1000.

- Volponi, A. , Enhanced Self Tuning On-Board Real-Time Model (eSTORM) for Aircraft Engine Performance Health Tracking. 2008.

- Volponi, A.; Brotherton, T.; Luppold, R. , Empirical Tuning of an On-Board Gas Turbine Engine Model for Real-Time Module Performance Estimation. Journal of Engineering for Gas Turbines and Power: Transactions of the Asme, 2008; 130, 96–105. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, L.; Junning, Q.; Jinquan, H.; Xiaojie, Q. , In-flight adaptive modeling using polynomial LPV approach for turbofan engine dynamic behavior. Aerosp Sci Technol 2017, 64. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.J.; Jia, S.L.; Zhang, H.B.; Zhang, T.H. , Research on Modeling Method of On-Board Engine Model Based on Sparse Auto-Encoder. Tuijin Jishu/Journal of Propulsion Technology 2017, 38, (6), 1209-1217.

- Zheng, Q.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Hu, Z. , Aero-engine On-board Dynamic Adaptive MGD Neural Network Model within a Large Flight Envelope. Ieee Access 2018, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Pang, S.; Zhang, H.; Hu, Z. , A Study on Aero-Engine Direct Thrust Control with Nonlinear Model Predictive Control Based on Deep Neural Network. Int J Aeronaut Space 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Fu, D.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhang, H. , A study on global optimization and deep neural network modeling method in performance-seeking control. Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers 2020, (1), 46–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.F.; Li, B.W.; Song, H.Q.; Pang, S.; Zhu, F.X. , Thrust Estimator Design Based on K-Means Clustering and Particle Swarm Optimization Kernel Extreme Learning Machine. Journal of Propulsion Technology 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, D.; Zheng, Q.; Zhang, H.; Chen, C.; Fang, J. , Aero-engine on-board adaptive steady-state model base on NN-PSM. Journal of Aerospace Power 2022, (2), 409–423. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, S.; Yingqing, G.; Wanli, Z. , Improved model for on-board real-time by constructing empirical model via GMM clustering method. Journal of Northwestern Polytechnical University 2020, (03), 507–514. [Google Scholar]

- Gilyard, G.B.; Orme, J.S. , Subsonic flight test evaluation of a performance seeking control algorithm on an F-15 airplane. American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Guo, Y.Q.; Zhang, S.G. , Aeroengine on-board adaptive model based on improved hybrid Kalman filter. Journal of Aerospace Power 2011, (11), 2593–2600. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Guo, Y.Q.; Chen, X.L. , Establishment of aero-engine state variable model based on linear fitting method. Journal of Aerospace Power 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sallee, G.P. Performance deterioration based on existing (historical) data; JT9D jet engine diagnostics program, 1978.

- Xu, M.; Wang, K.; Li, M.; Geng, J.; Wu, Y.; Liu, J.; Song, Z. , An adaptive on-board real-time model with residual online learning for gas turbine engines using adaptive memory online sequential extreme learning machine. Aerosp Sci Technol 2023, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, D.L.; Bouldin, D.W. , A Cluster Separation Measure. Ieee T Pattern Anal 1979, PAMI-1, (2), 224-227, -1.

- Bezdek, J.C.; Pal, N.R. , Some New Indexes of Cluster Validity. Ieee Transactions On Systems, Man, and Cybernetics, Part B. Cybernetics: A Publication of the Ieee Systems, Man, and Cybernetics Society 1998, (3), 28.

- Angiulli, F.; Fassetti, F. , Detecting distance-based outliers in streams of data. Acm 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Cui, L.; Shi, H.Y. , Online Anomaly Detection for Aeroengine Gas Path Based on Piecewise Linear Representation and Support Vector Data Description. Ieee Sens J 2022, (23), 22808–22816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).