1. Introduction

Polyethylene terephthalate (PET) is a polymer of great importance among the world's plastics. Thermoplastic recyclability makes it the first choice for various applications [

1]. PET, a polyester plastic, is one of the most used packaging materials in beverages. Due to its excellent transparency, light weight, gas and water barrier properties, impact resistance, UV resistance and unbreakability, the production and use of PET bottles for beverage packaging has continuously increased worldwide [

2]. With this increase in production and use, recycling solutions for PET began to be produced. PET is seen as one of the plastic types with the highest recycling rate today [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7].

PET can be recycled in the construction industry as well as in the plastics industry. Reusing plastics such as PET instead of aggregates in concrete is seen as an event that can contribute to environmental protection and sustainable development [

8]. It is thought that the use of PET in concrete as a partial or complete replacement for natural aggregates can protect natural aggregate resources [

9]. For this purpose, there are many studies examining various properties of concrete by using PET as a fine aggregate replacement in concrete [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34]. When the study results were examined, it was seen that the use of PET generally caused a decrease in the mechanical properties of concrete. It is thought that strengthening methods can be used to compensate for the possible decrease in mechanical properties due to the use of PET. In a study [

35], it was stated that wrapping PET substituted concrete with carbon fiber reinforced polymer (CFRP) could be one of these methods.

A frequently used technique to strengthen existing reinforced concrete structures is the use of fiber reinforced polymer (FRP) systems. It is clearly understood that lateral confinement of concrete can significantly increase its strength and ductility. With the introduction of FRP composites into the construction industry, the use of FRP as a wrapping material has attracted great attention [

36]. The main advantage of FRP systems is that FRP materials have low mass and high tensile capacity and can provide greater durability when installed properly [

37]. FRP is widely used in the construction of new structures and rehabilitation of old structures due to its non-corrosive properties and high strength/weight ratios [

38]. The majority of concrete wrapping studies with FRP to date have been done on CFRP and GFRP [

39].

In this study, sand in concrete was partially replaced with PET in order to protect natural resources and recycle PET. The results and models of similar studies in literature were brought together and the connections between the experimental results were interpreted. The mechanical properties of concrete have been tried to be increased by using CFRP and GFRP. Similarly, an evaluation was made with studies in literature.

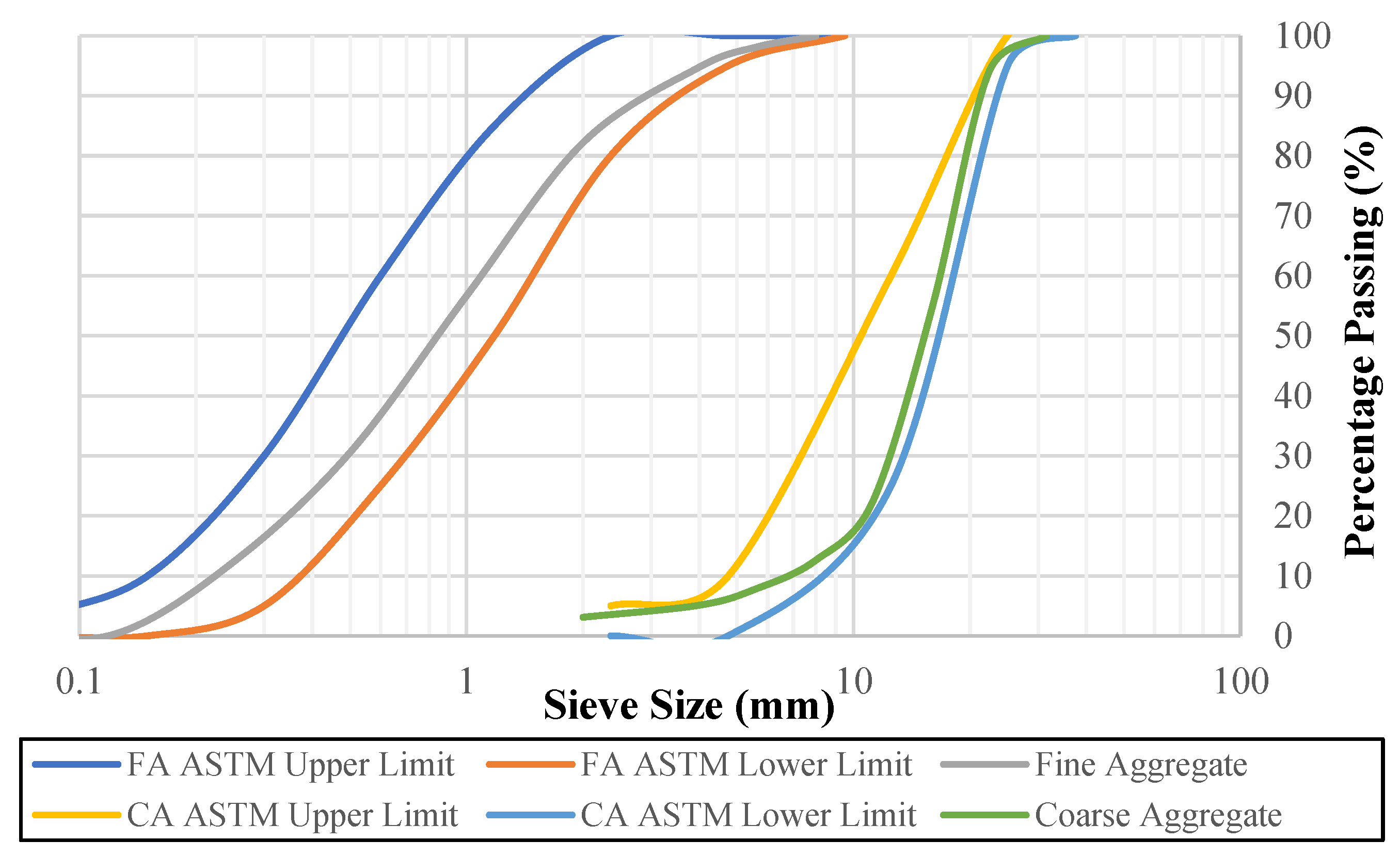

Figure 1.

Grading curves of aggregates.

Figure 1.

Grading curves of aggregates.

Figure 3.

FRP types: (a) CFRP, (b) GFRP.

Figure 3.

FRP types: (a) CFRP, (b) GFRP.

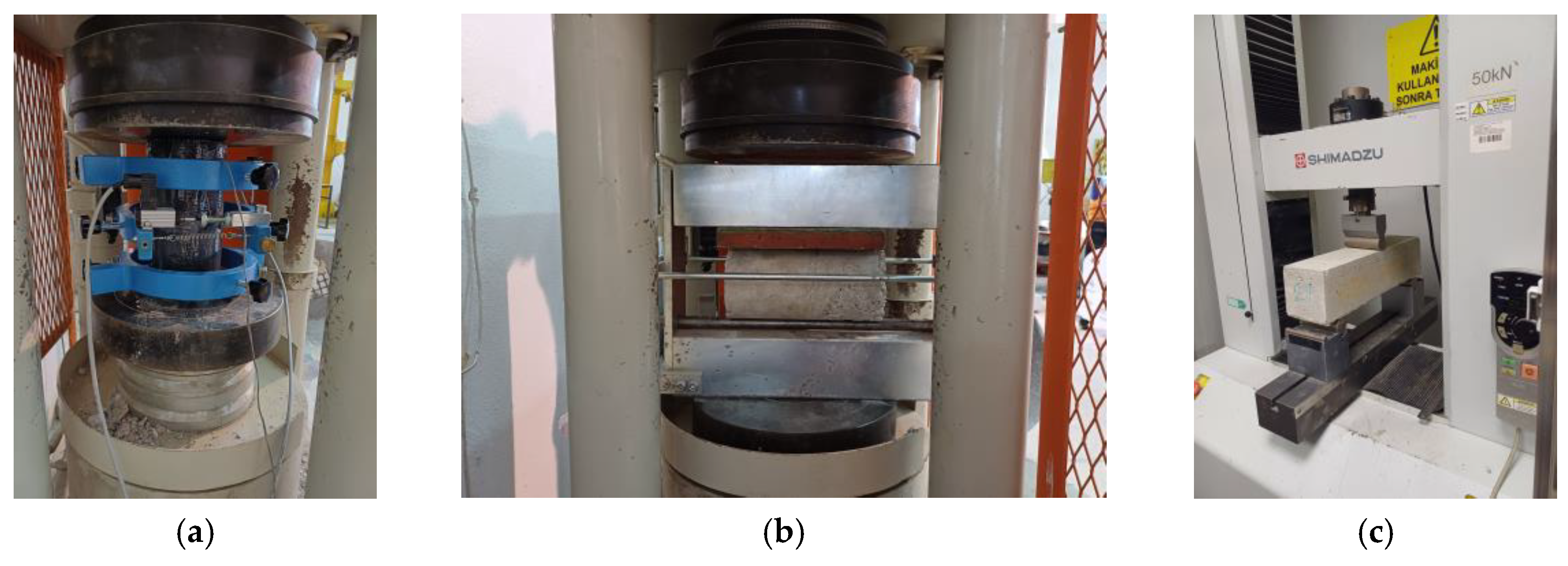

Figure 4.

Experimental setups: (a) Compressive, (b) Splitting tensile, (c) Flexural.

Figure 4.

Experimental setups: (a) Compressive, (b) Splitting tensile, (c) Flexural.

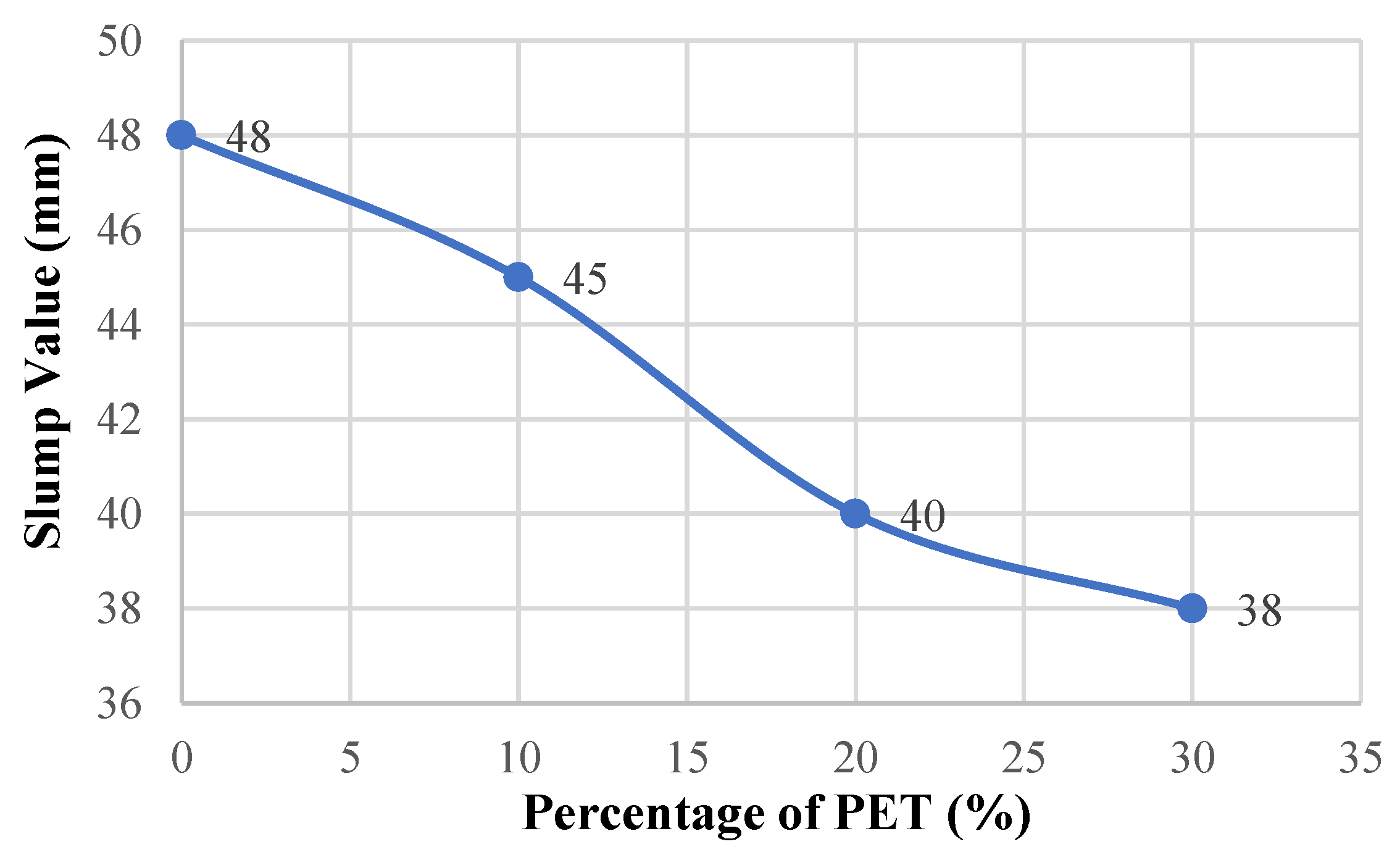

Figure 5.

Slump–percentage of PET graph.

Figure 5.

Slump–percentage of PET graph.

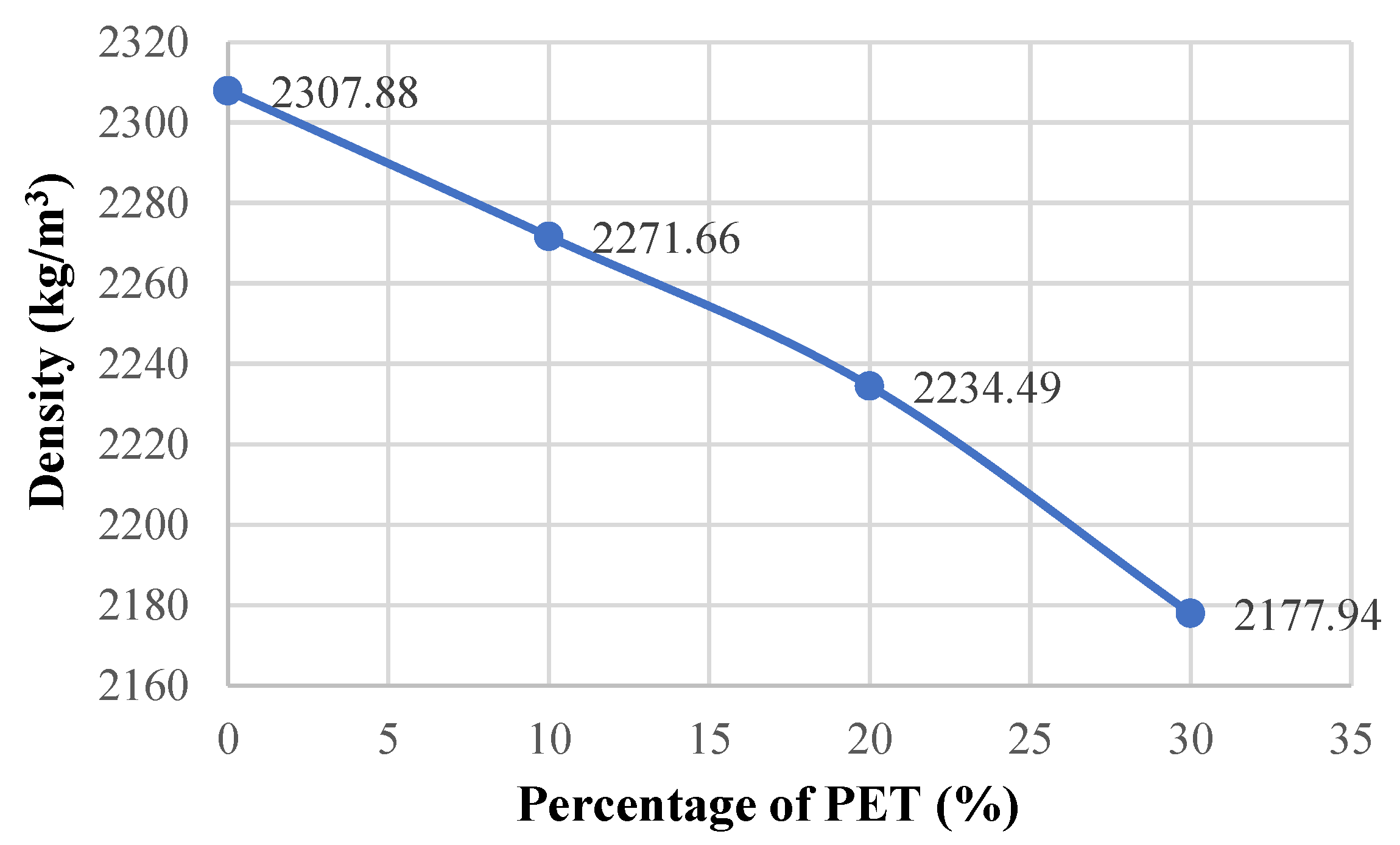

Figure 6.

Density–percentage of PET graph.

Figure 6.

Density–percentage of PET graph.

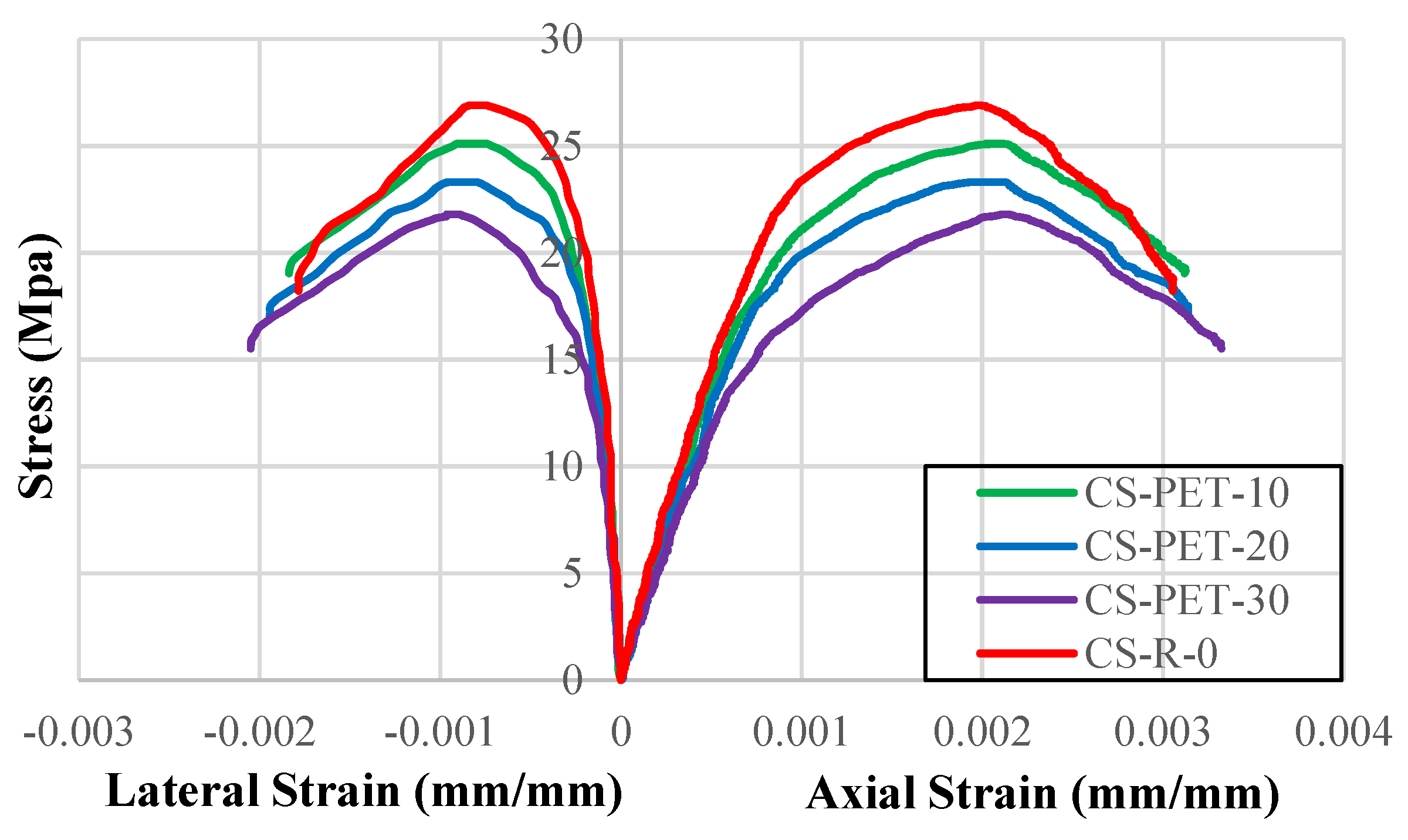

Figure 7.

Stress-strain graphs of samples without FRP.

Figure 7.

Stress-strain graphs of samples without FRP.

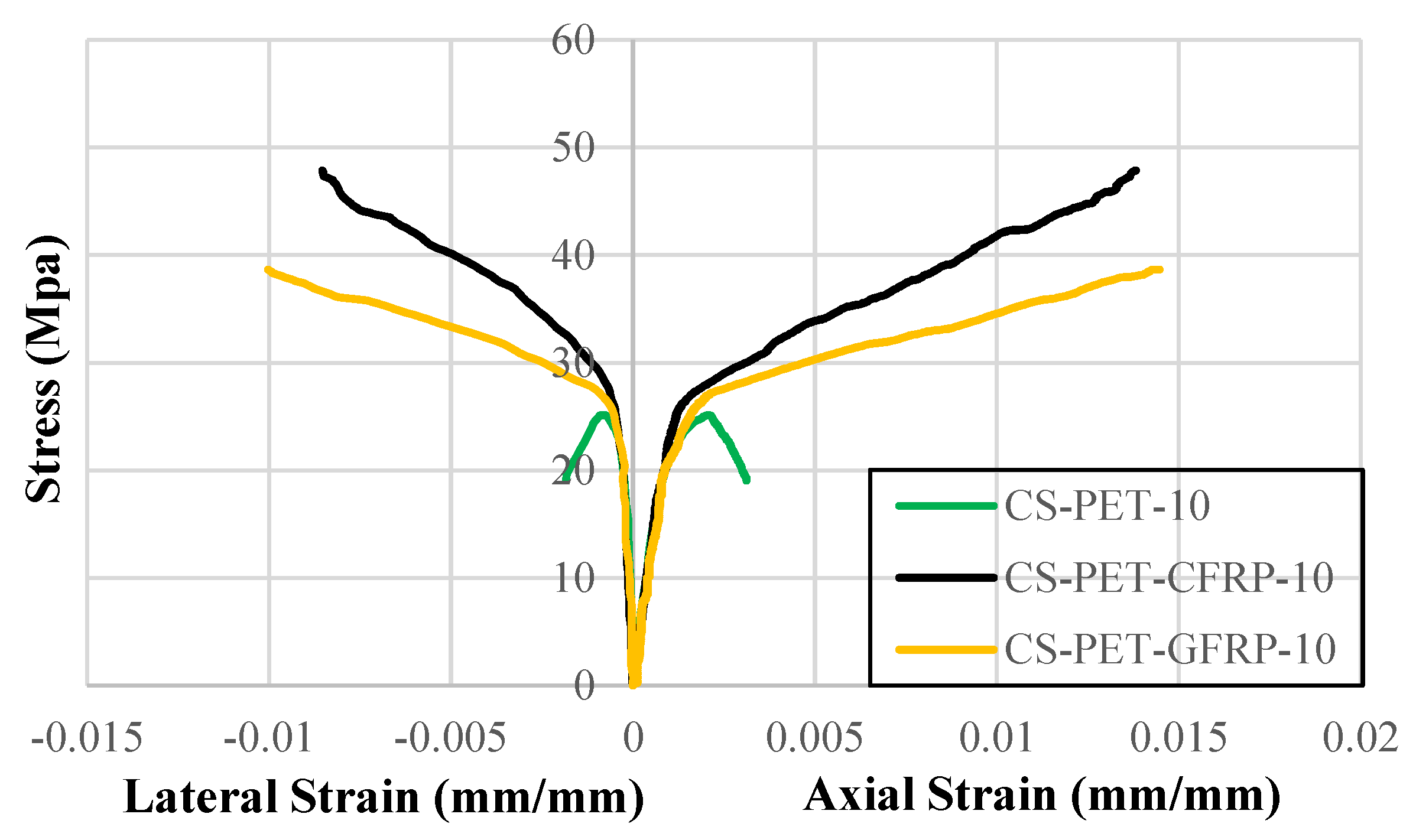

Figure 8.

Stress-strain graphs of samples with FRP.

Figure 8.

Stress-strain graphs of samples with FRP.

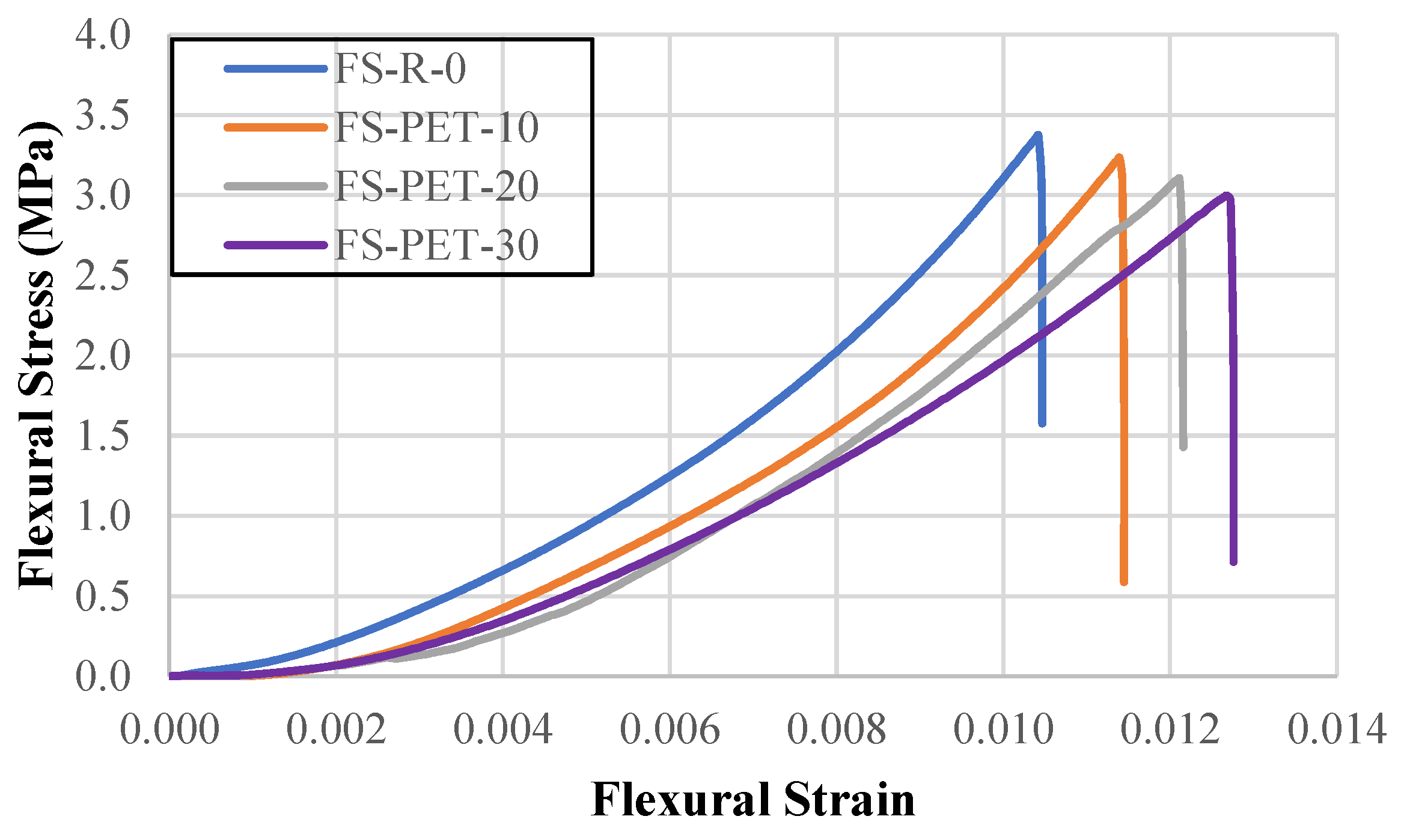

Figure 9.

Flexural stress-flexural strain graphs of samples without FRP.

Figure 9.

Flexural stress-flexural strain graphs of samples without FRP.

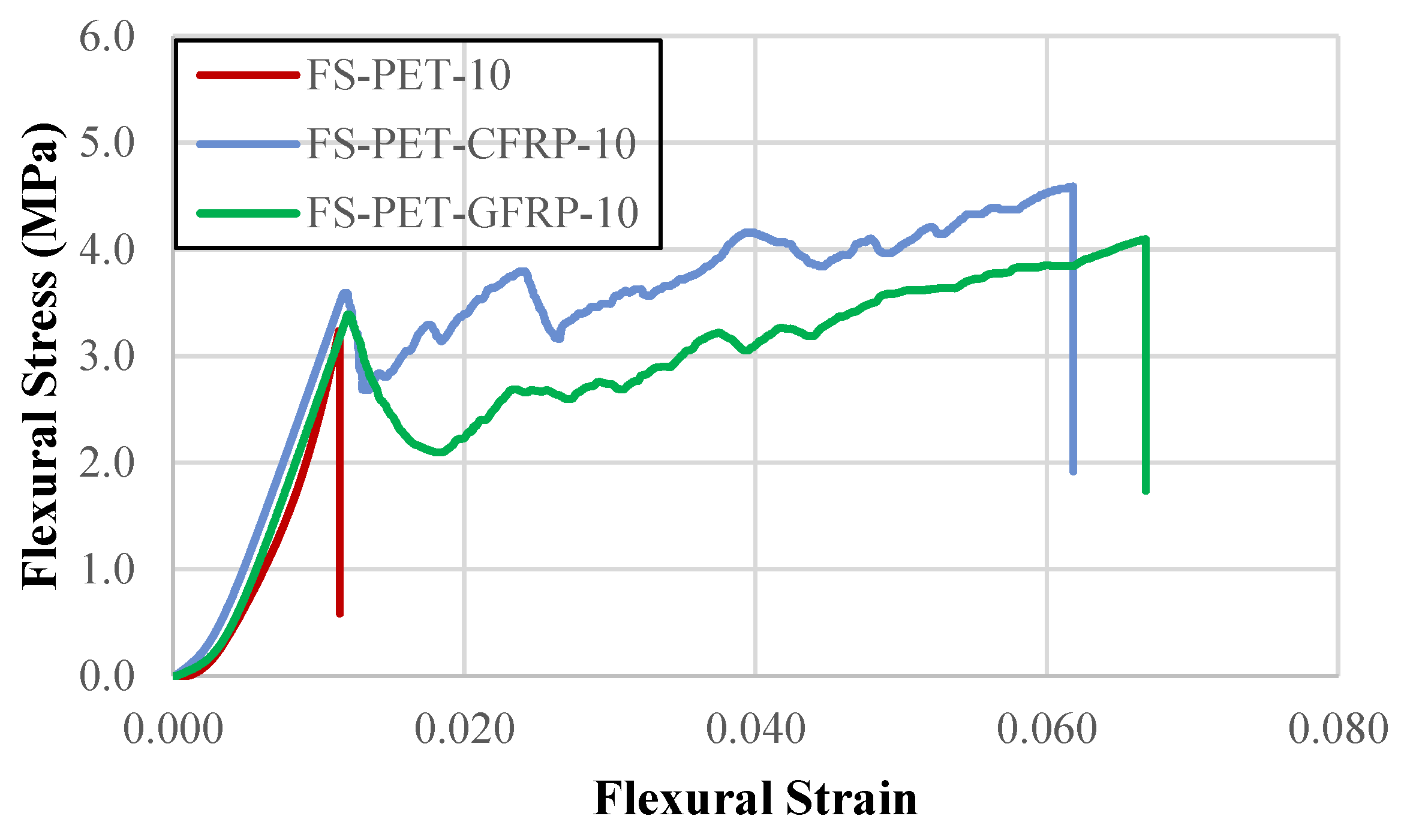

Figure 10.

Flexural stress-flexural strain graphs of samples with FRP.

Figure 10.

Flexural stress-flexural strain graphs of samples with FRP.

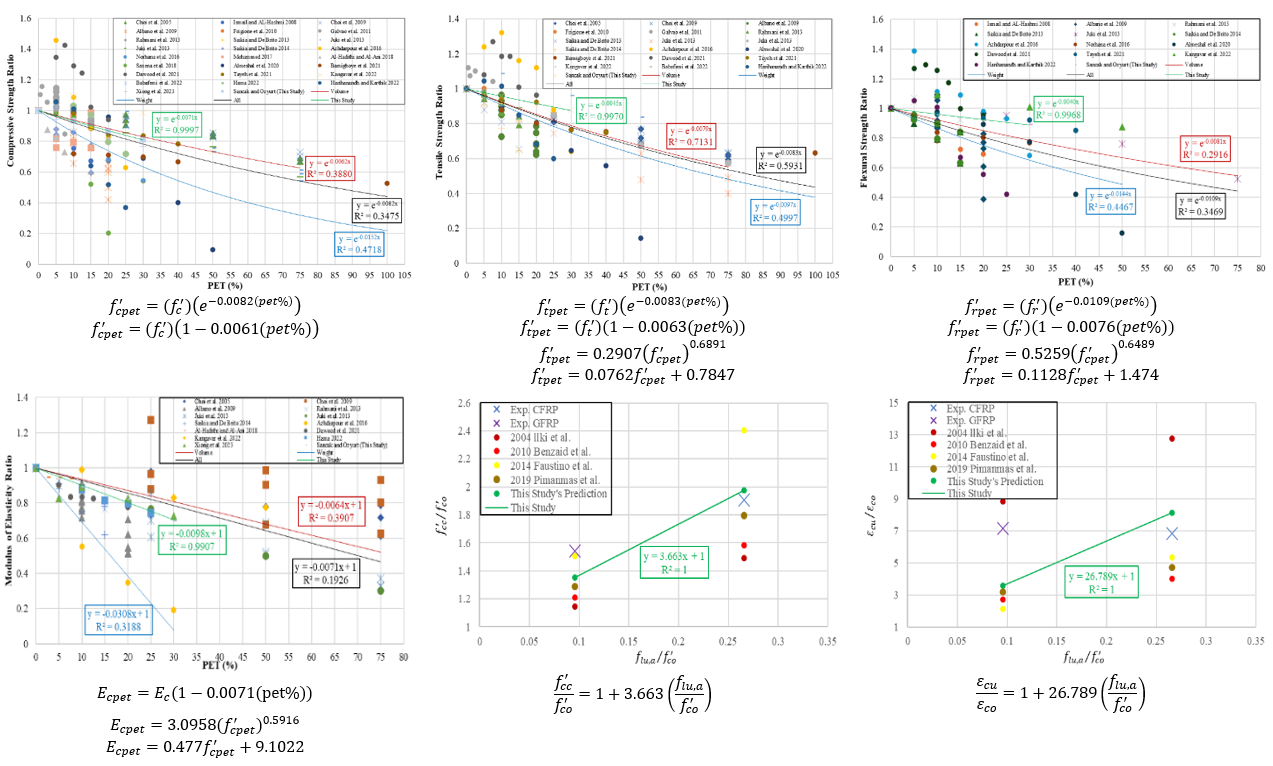

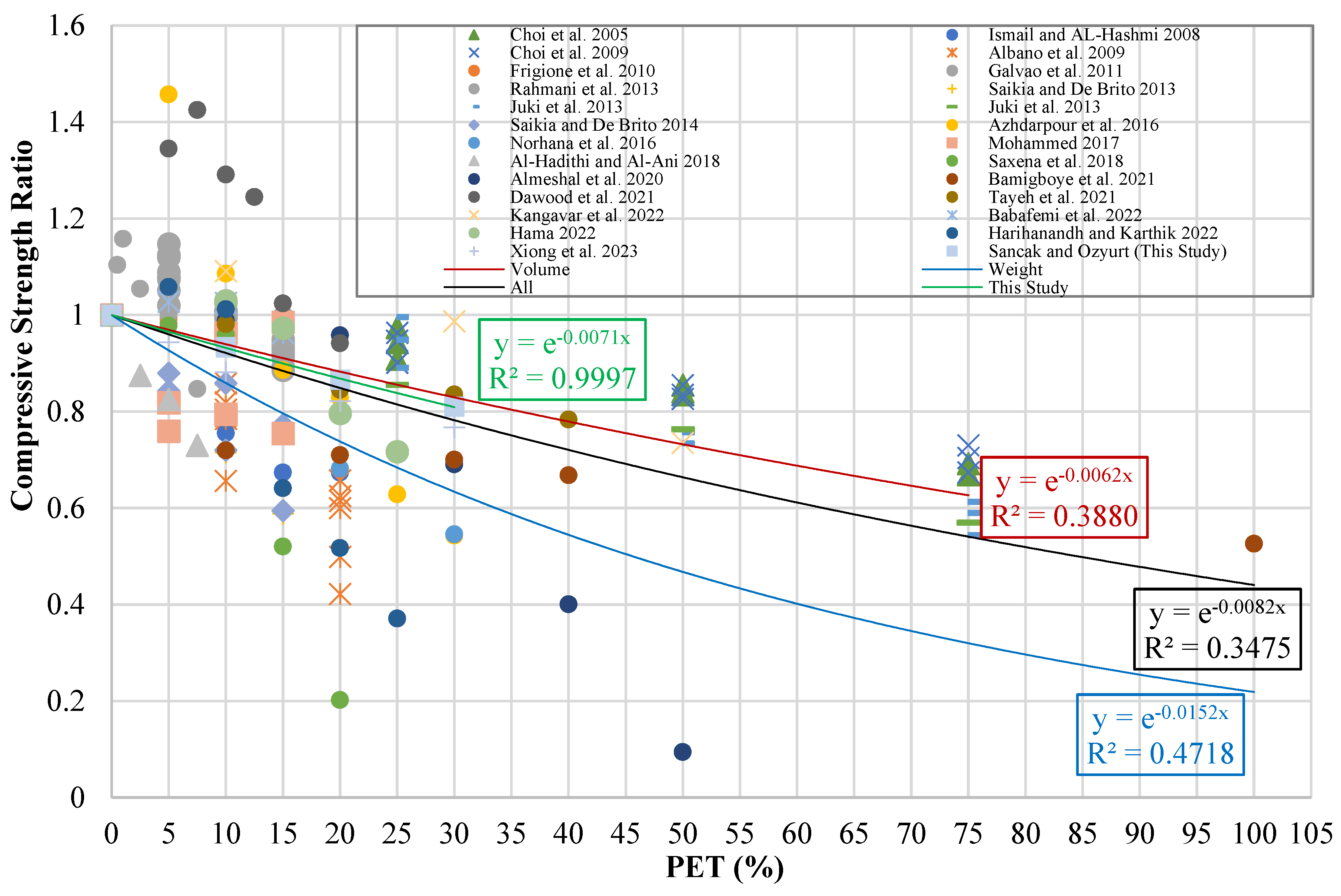

Figure 11.

Compressive strength ratio-PET (%) graph.

Figure 11.

Compressive strength ratio-PET (%) graph.

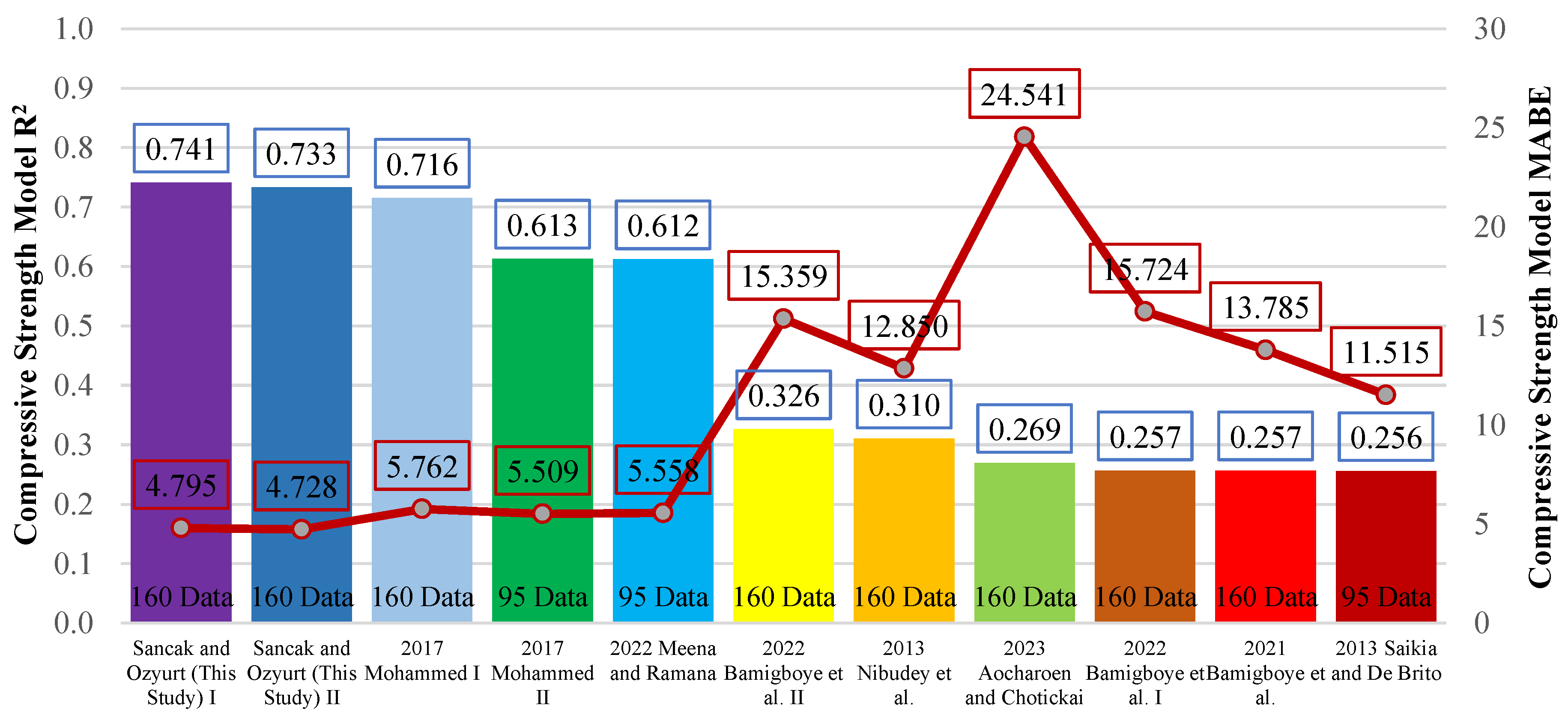

Figure 12.

Comparison of R2 and MABE for compressive strength models.

Figure 12.

Comparison of R2 and MABE for compressive strength models.

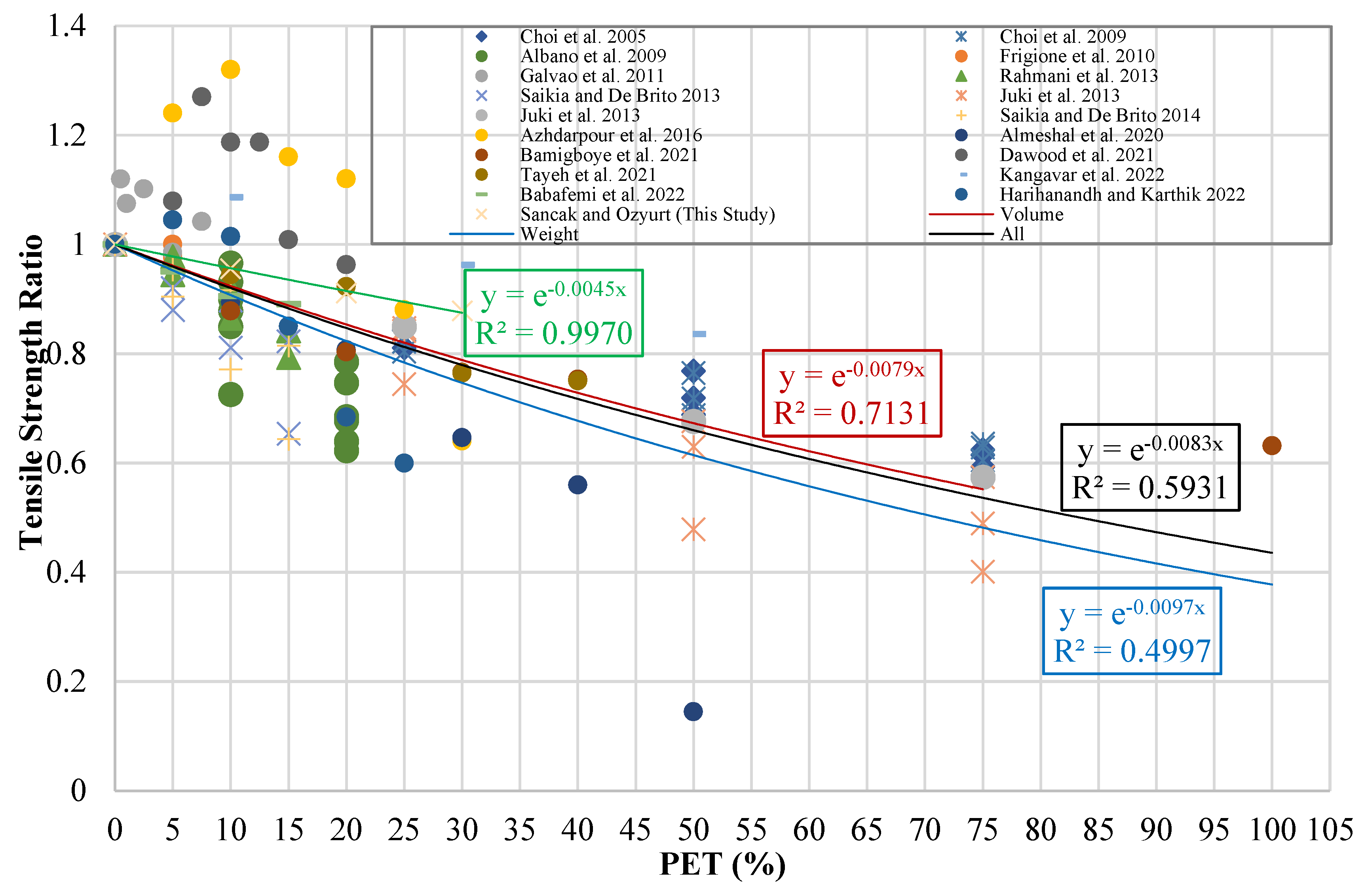

Figure 13.

Tensile strength ratio-PET (%) graph.

Figure 13.

Tensile strength ratio-PET (%) graph.

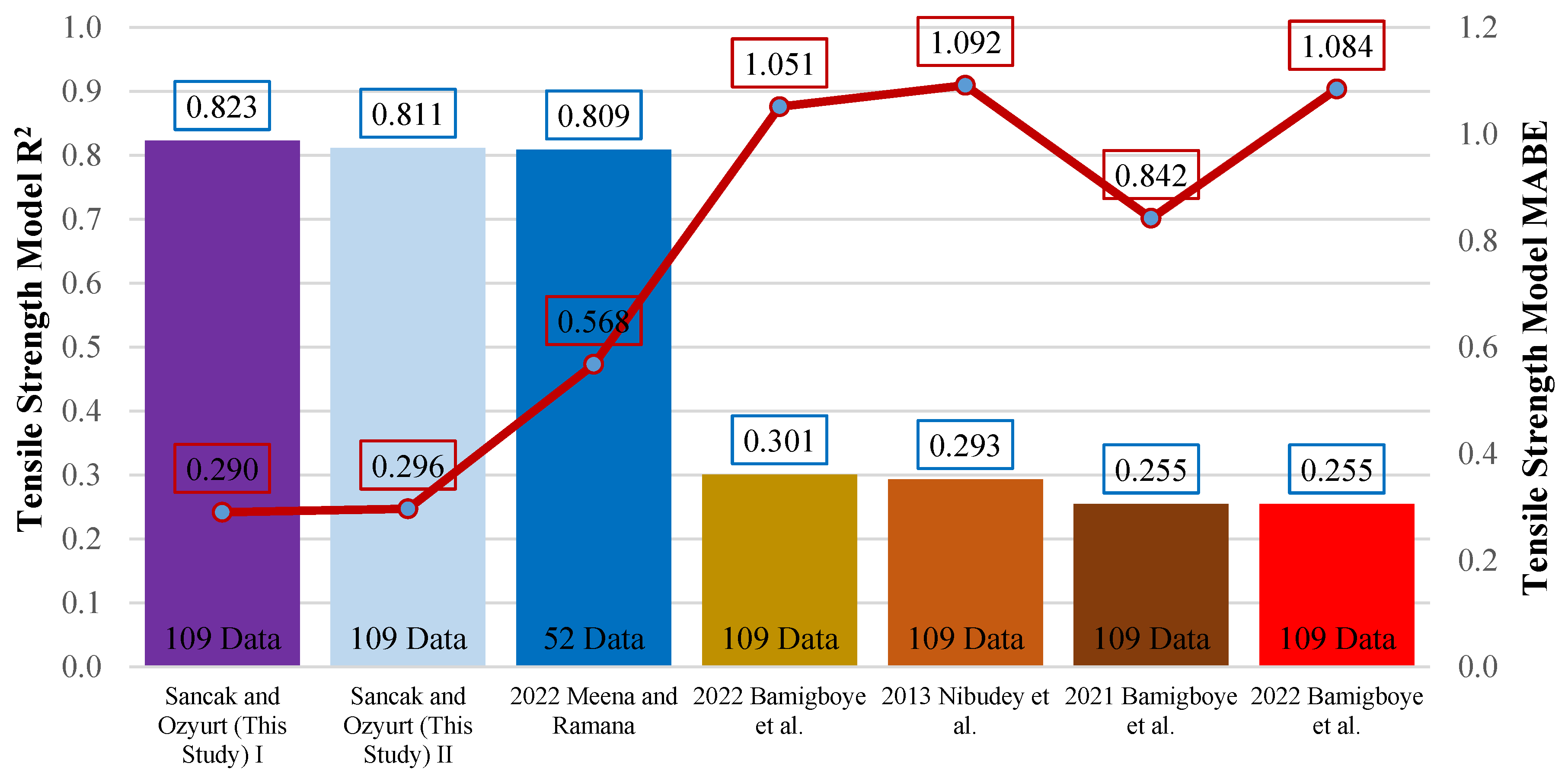

Figure 14.

Comparison of R2 and MABE for models of the connection between tensile strength and PET (%).

Figure 14.

Comparison of R2 and MABE for models of the connection between tensile strength and PET (%).

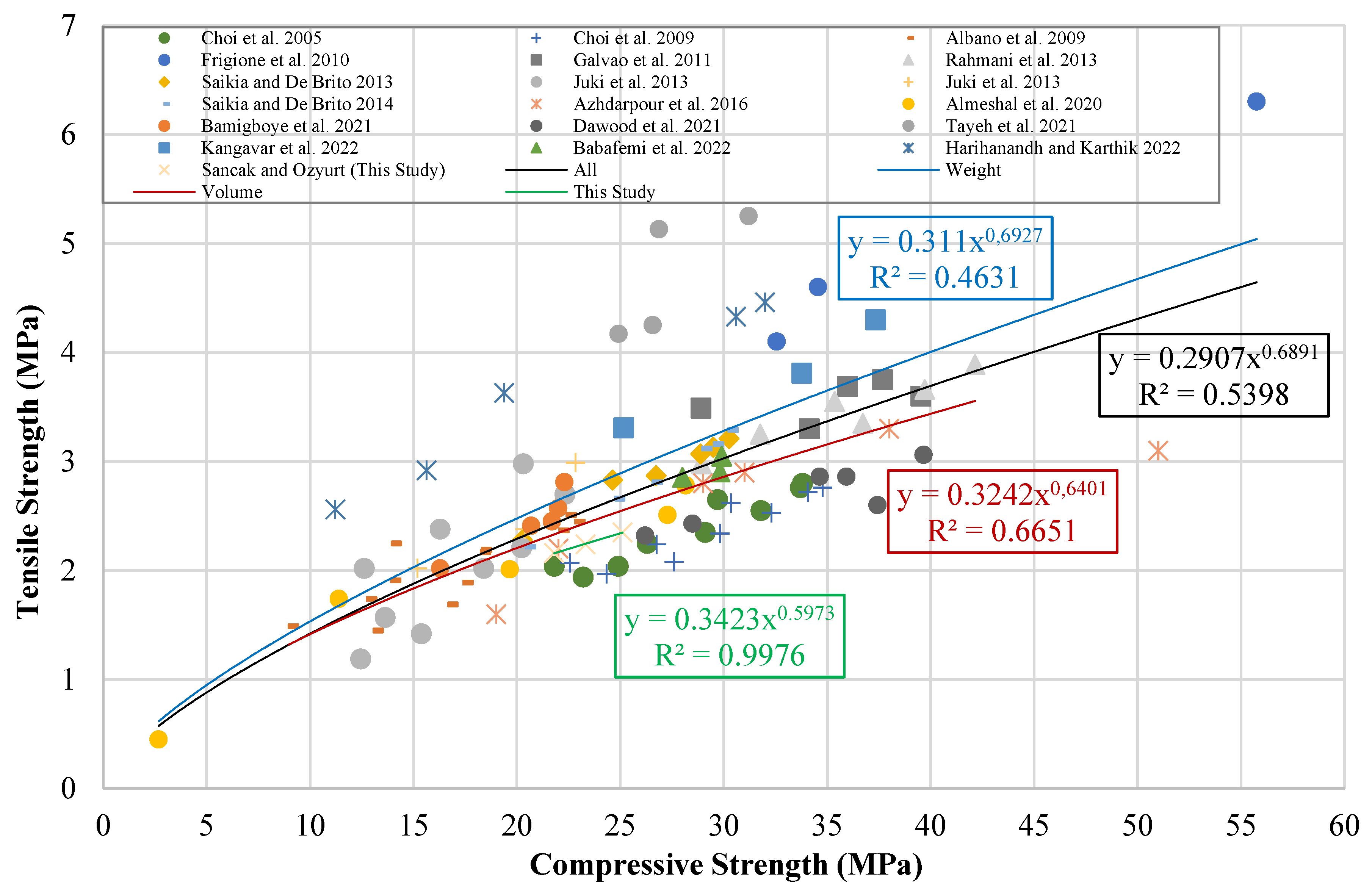

Figure 15.

Tensile strength-compressive strength graph.

Figure 15.

Tensile strength-compressive strength graph.

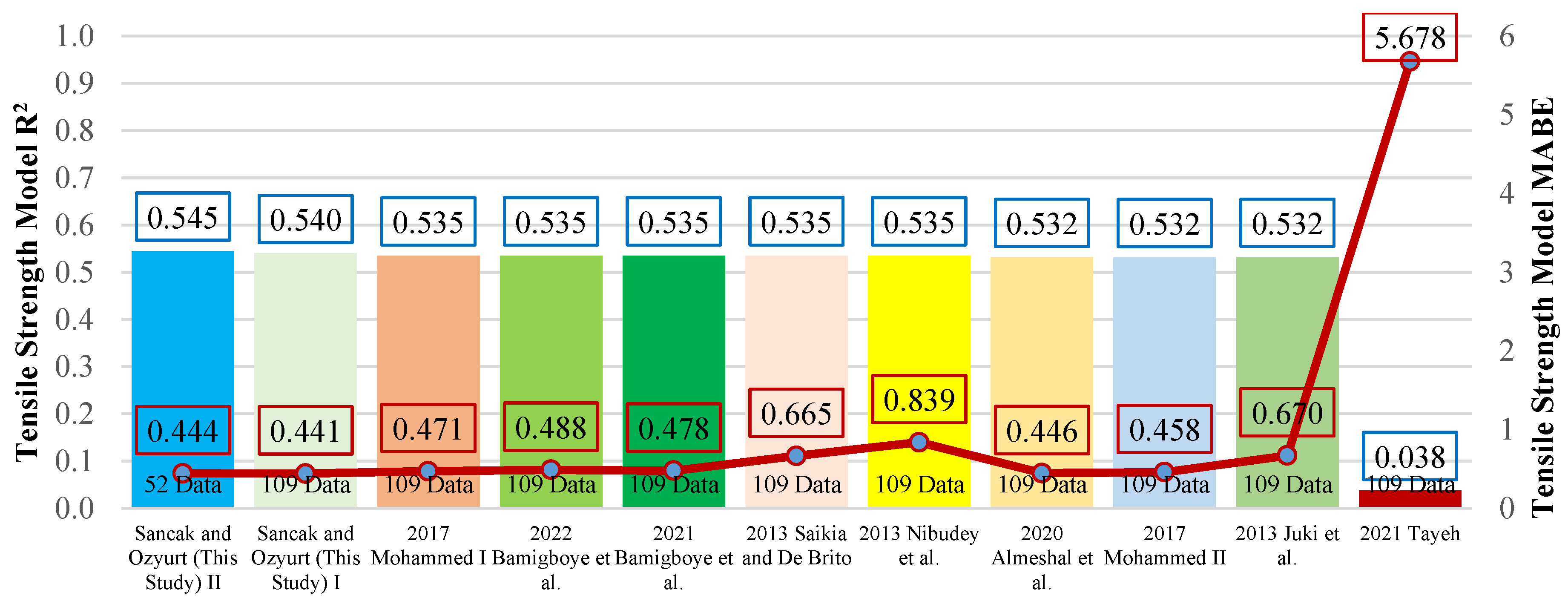

Figure 16.

Comparison of R2 and MABE for models of the connection between tensile strength and compressive strength.

Figure 16.

Comparison of R2 and MABE for models of the connection between tensile strength and compressive strength.

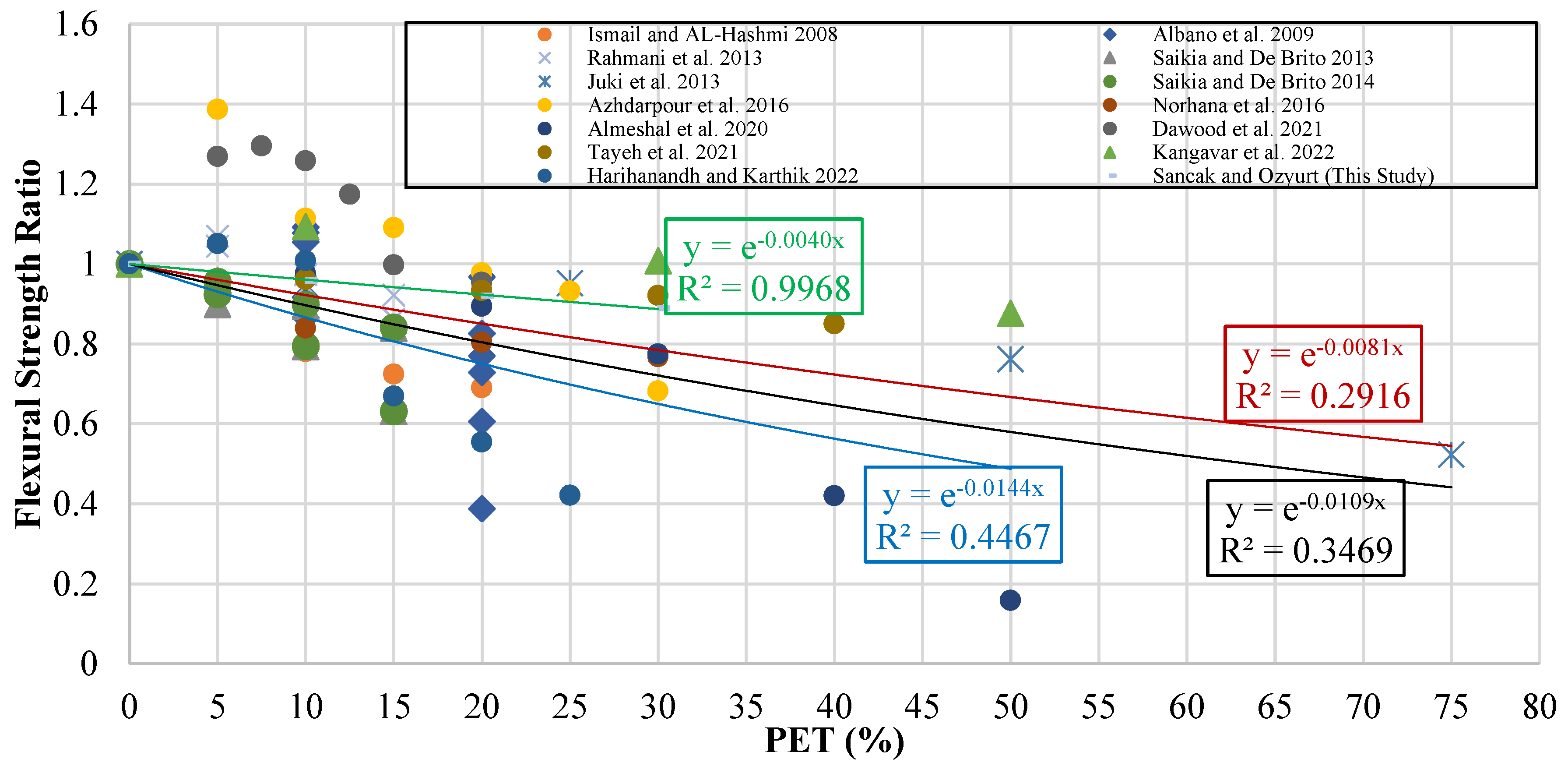

Figure 17.

Flexural strength ratio-PET (%) graph.

Figure 17.

Flexural strength ratio-PET (%) graph.

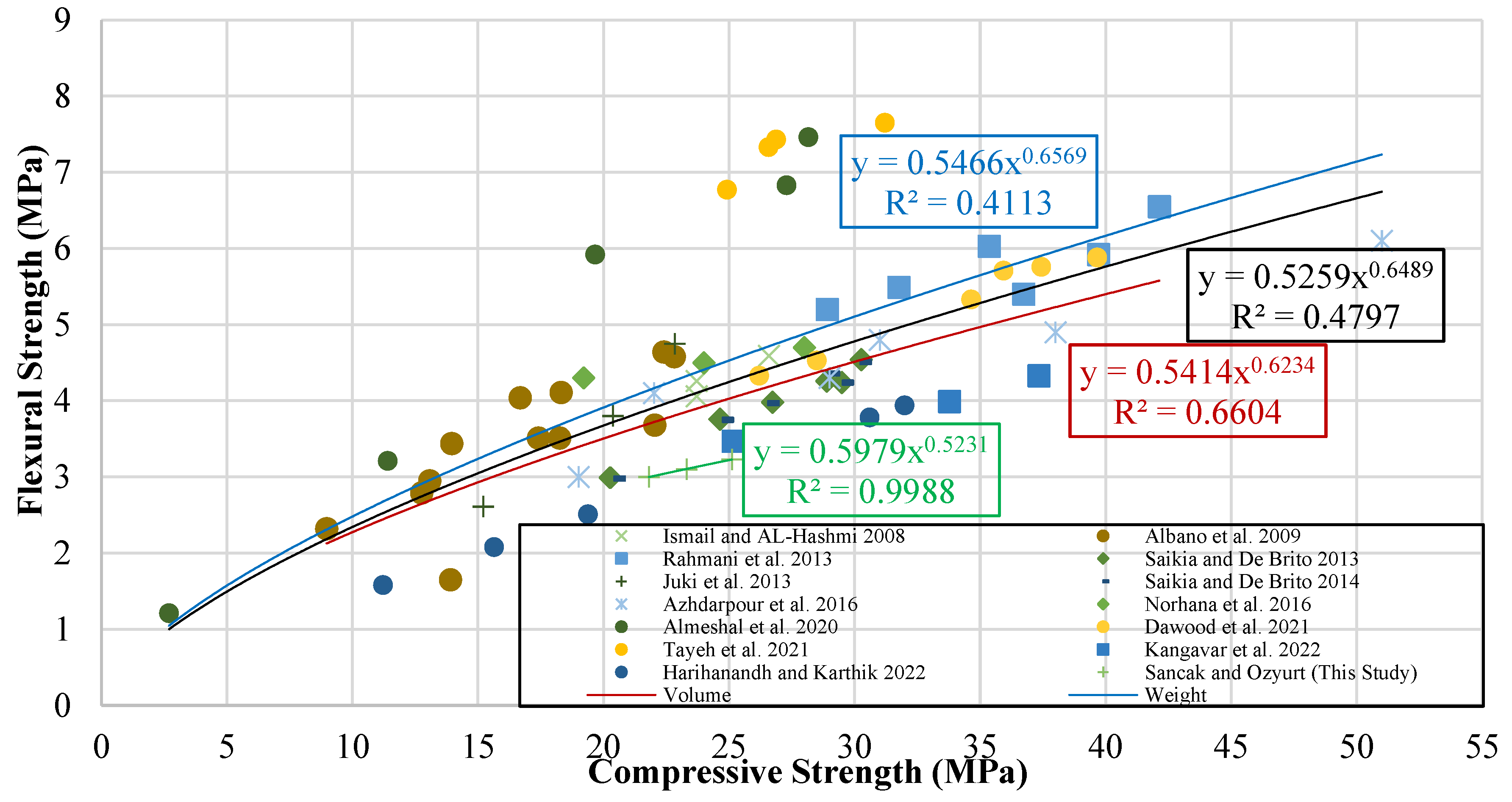

Figure 18.

Flexural strength-compressive strength graph.

Figure 18.

Flexural strength-compressive strength graph.

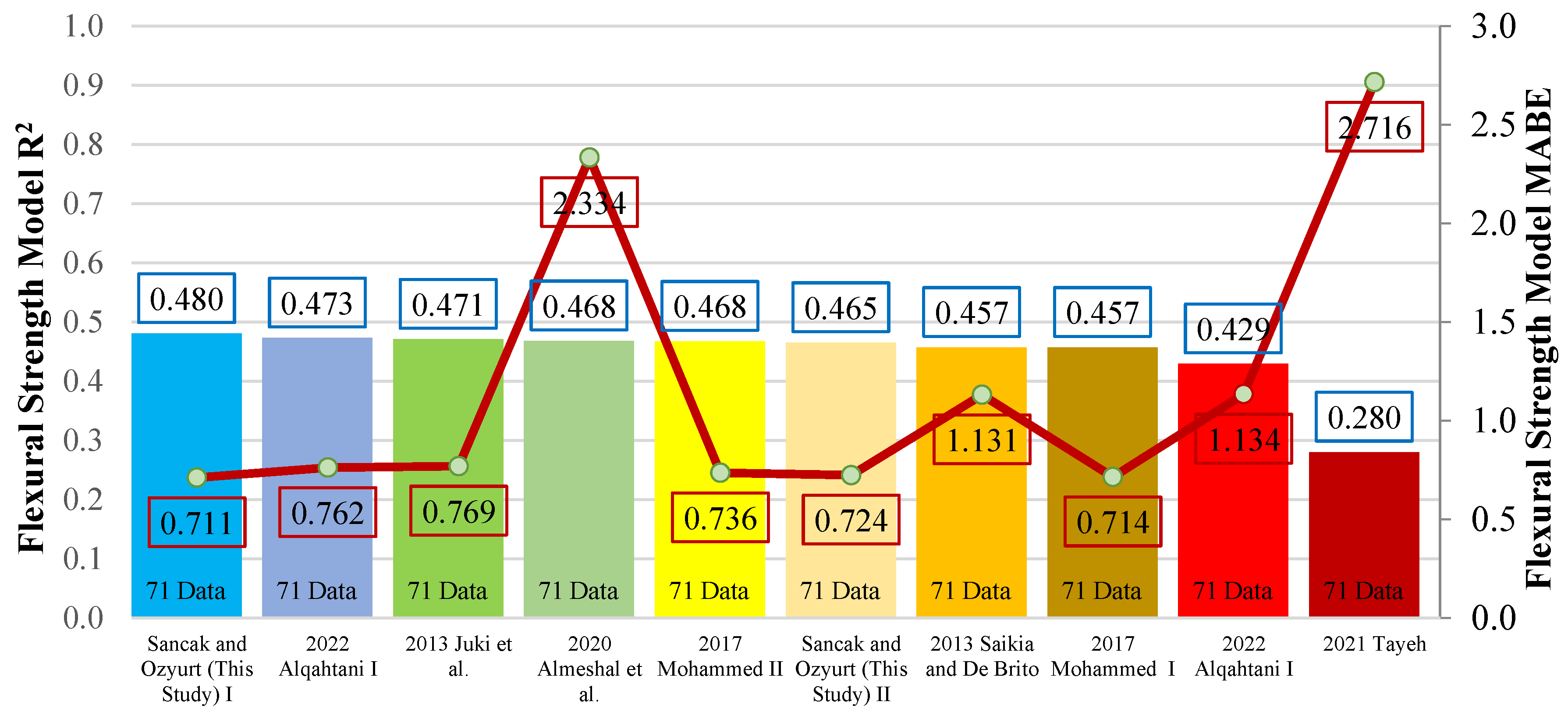

Figure 19.

Comparison of R2 and MABE for models of the connection between flexural strength and compressive strength.

Figure 19.

Comparison of R2 and MABE for models of the connection between flexural strength and compressive strength.

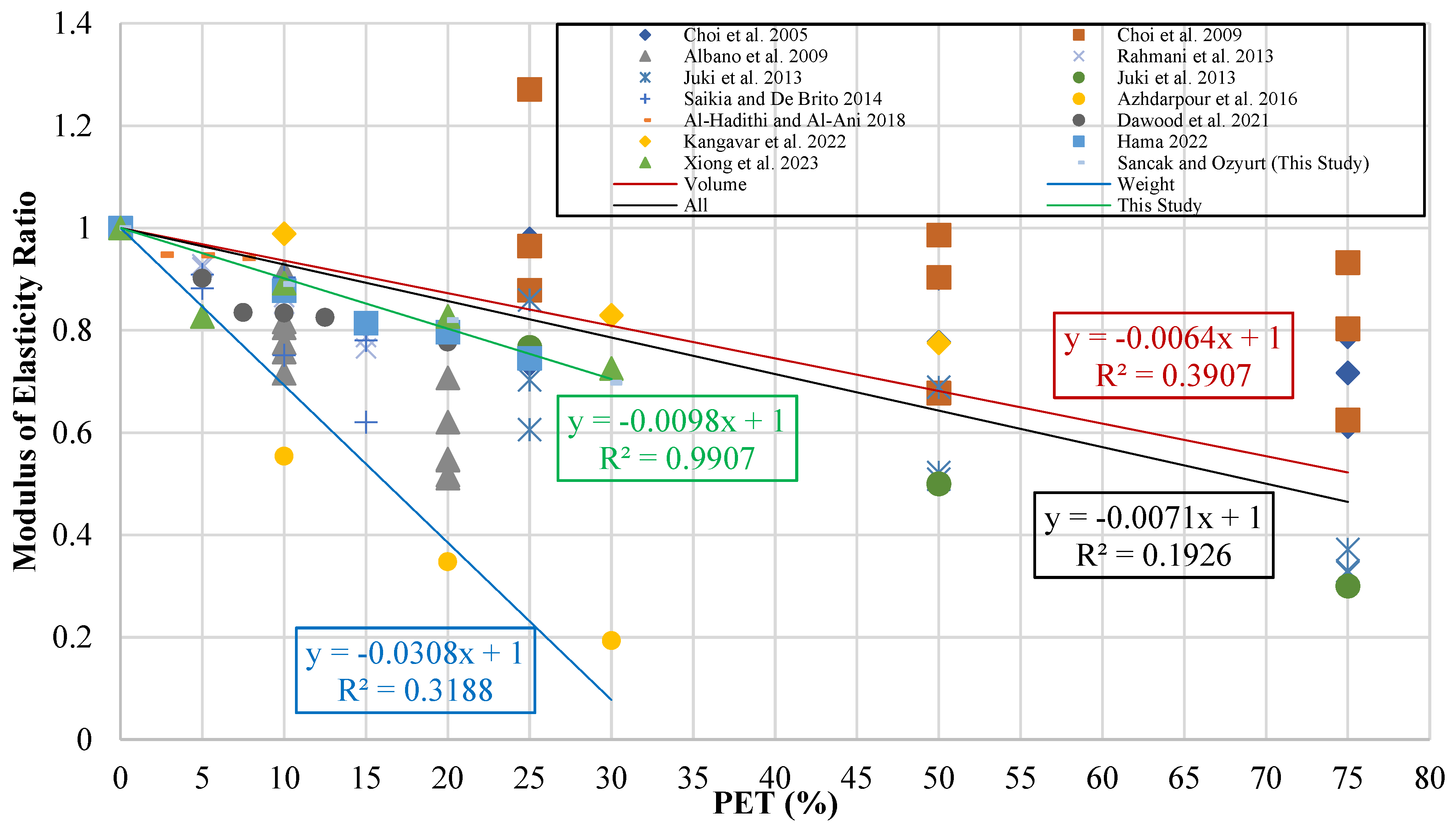

Figure 20.

Modulus of elasticity ratio-PET (%) graph.

Figure 20.

Modulus of elasticity ratio-PET (%) graph.

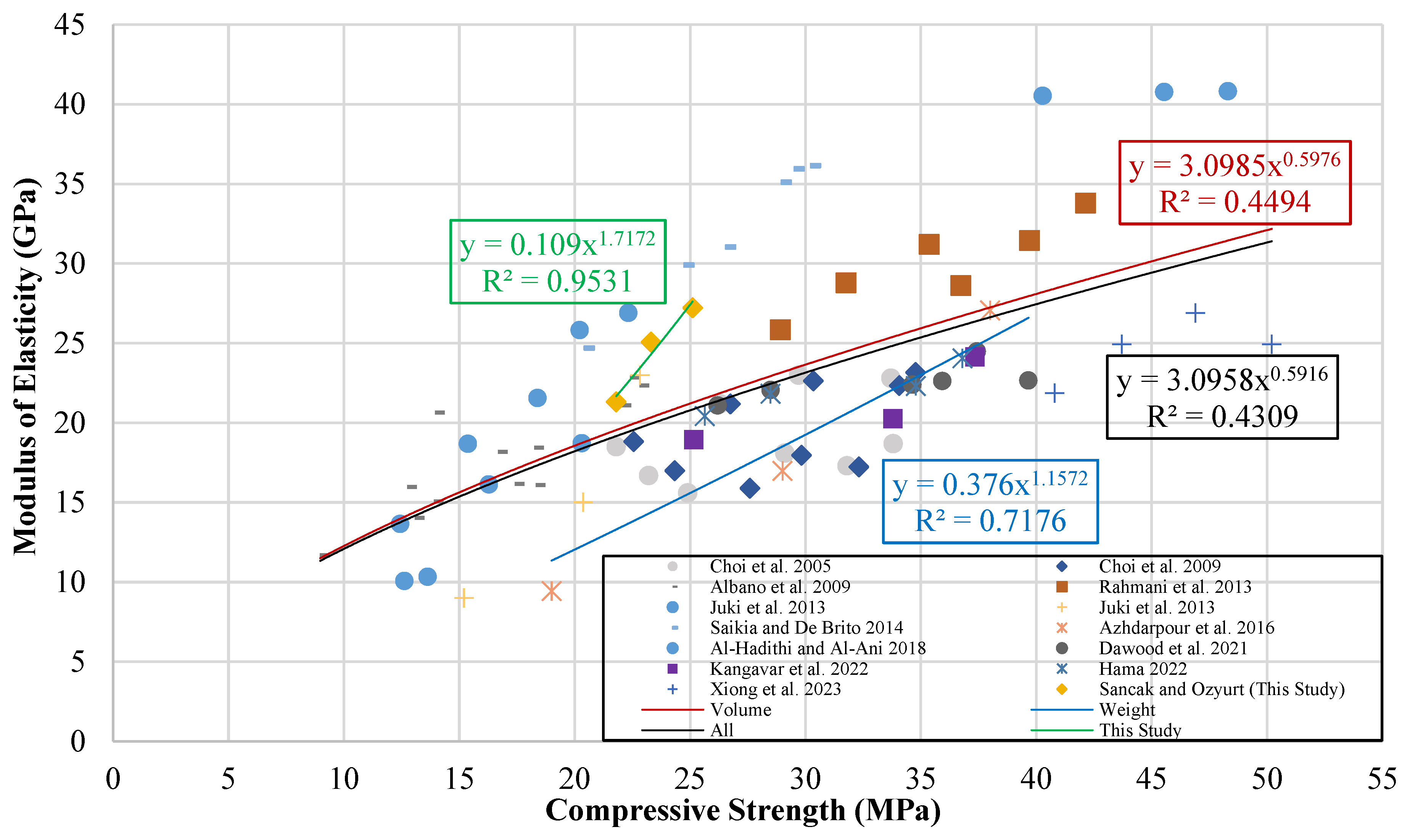

Figure 21.

Modulus of elasticity-compressive strength graph.

Figure 21.

Modulus of elasticity-compressive strength graph.

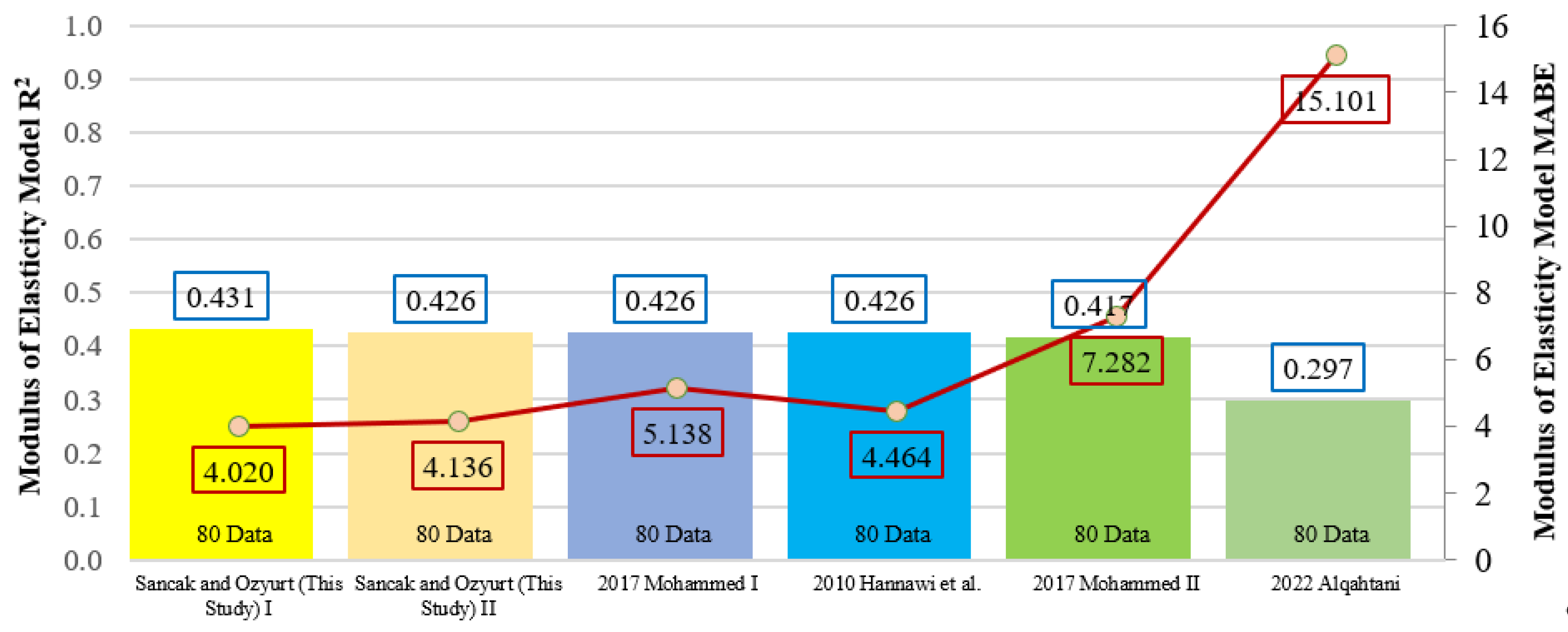

Figure 22.

Comparison of R2 and MABE for models of the connection between modules of elasticity and compressive strength.

Figure 22.

Comparison of R2 and MABE for models of the connection between modules of elasticity and compressive strength.

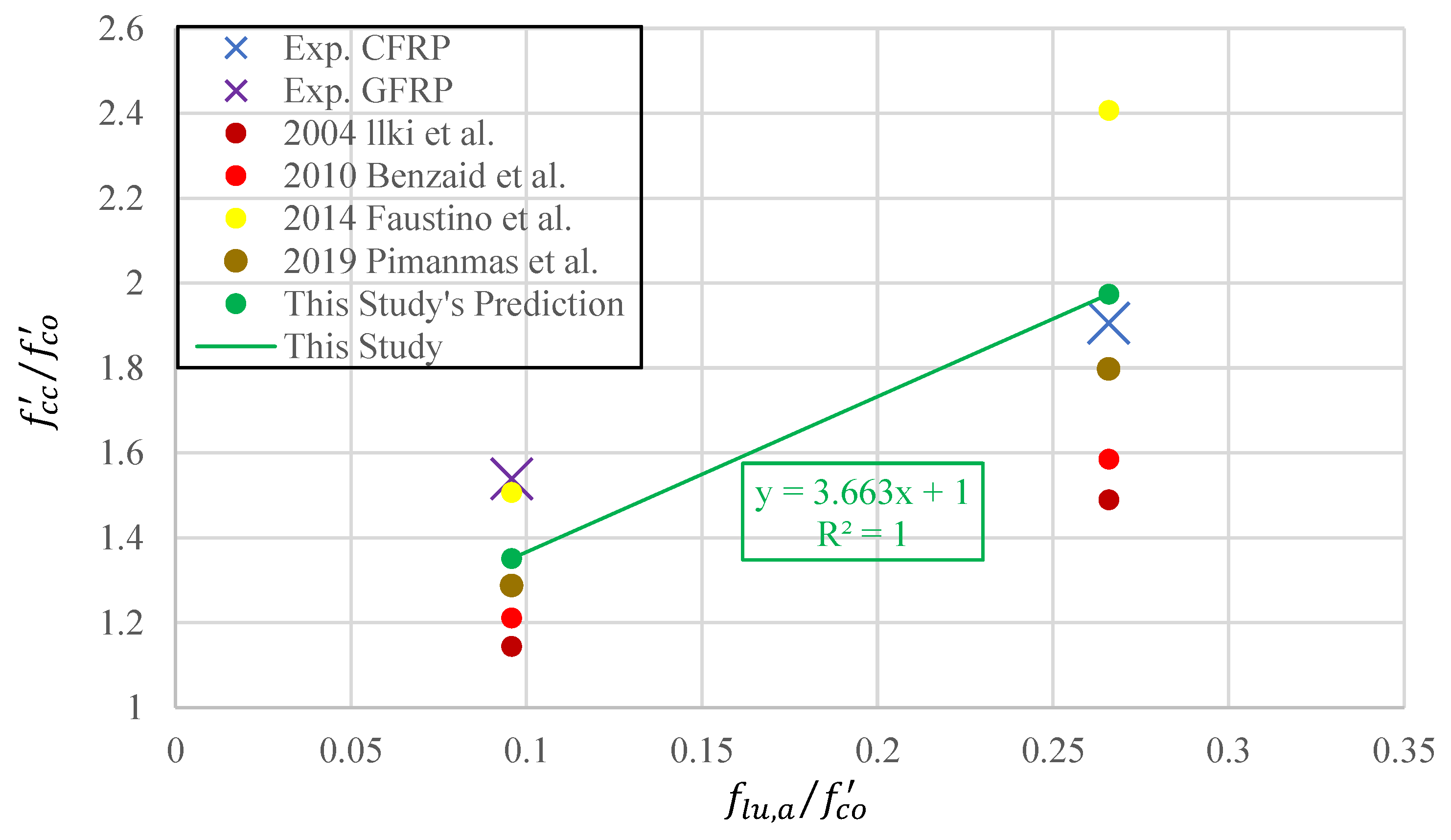

Figure 23.

Experimental data and model predictions for compressive strength under FRP wrapping effect.

Figure 23.

Experimental data and model predictions for compressive strength under FRP wrapping effect.

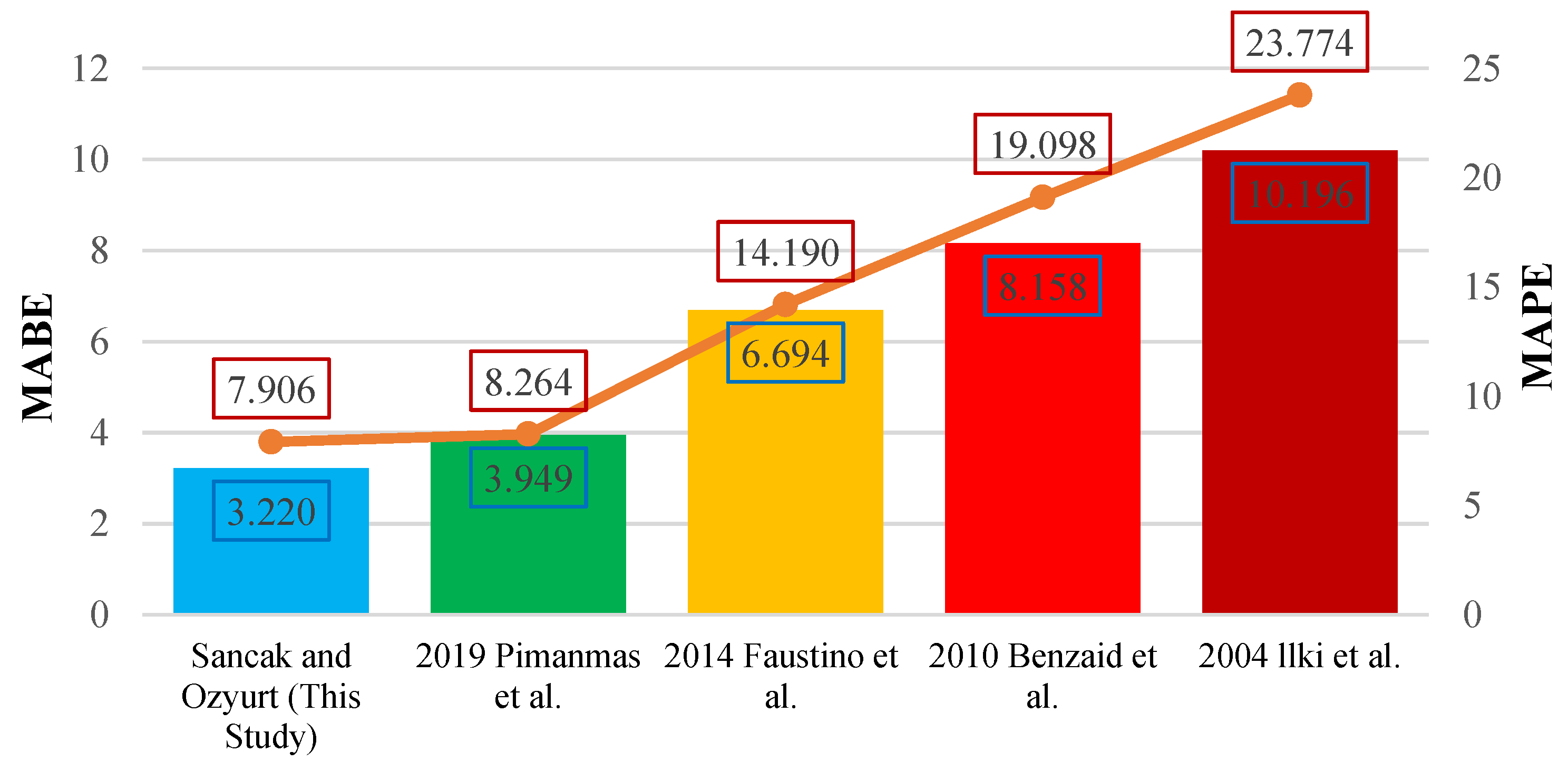

Figure 24.

Comparison of MABE and MAPE for compressive strength models under FRP wrapping effect.

Figure 24.

Comparison of MABE and MAPE for compressive strength models under FRP wrapping effect.

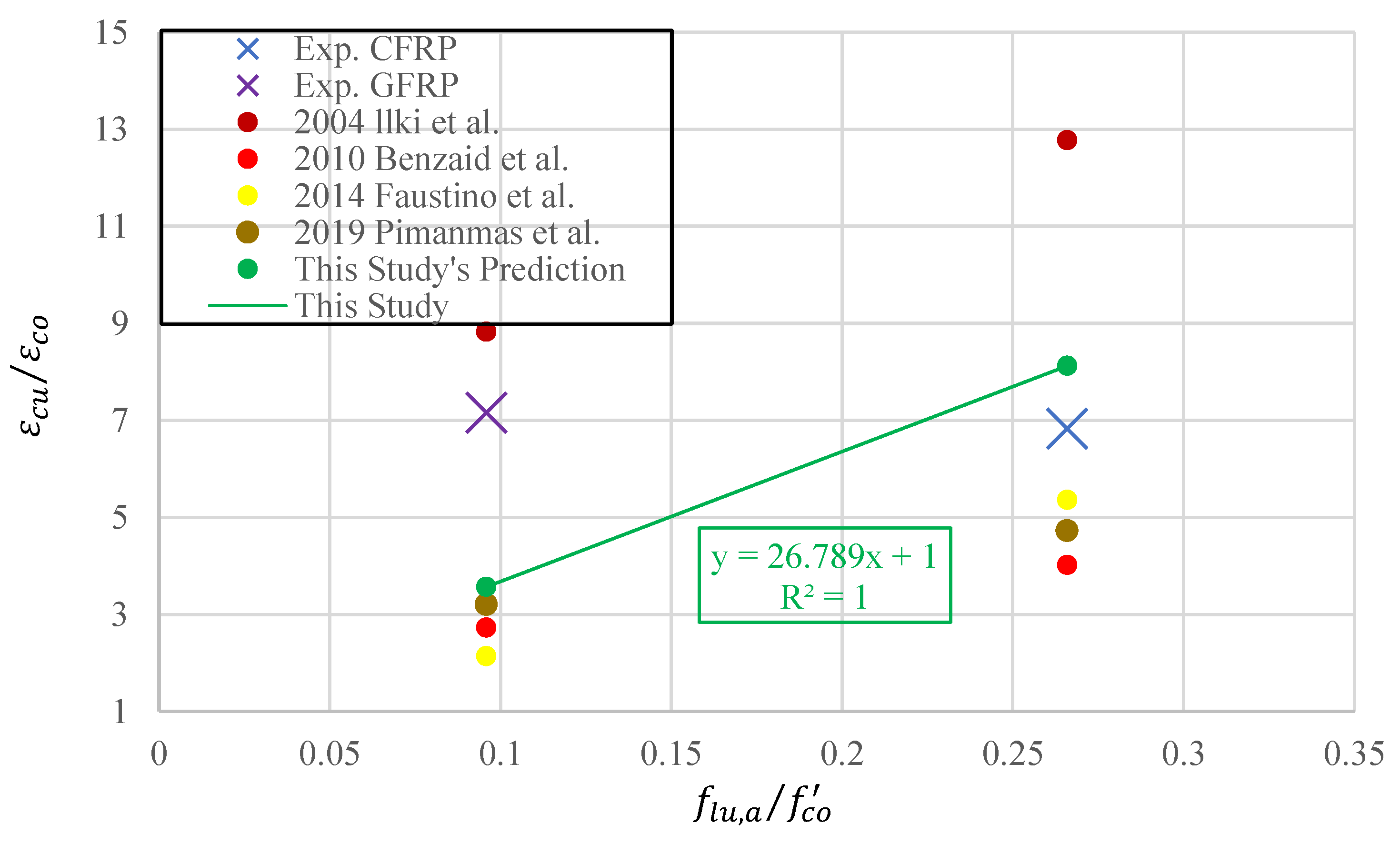

Figure 25.

Experimental data and model predictions for ultimate axial strain under FRP wrapping effect.

Figure 25.

Experimental data and model predictions for ultimate axial strain under FRP wrapping effect.

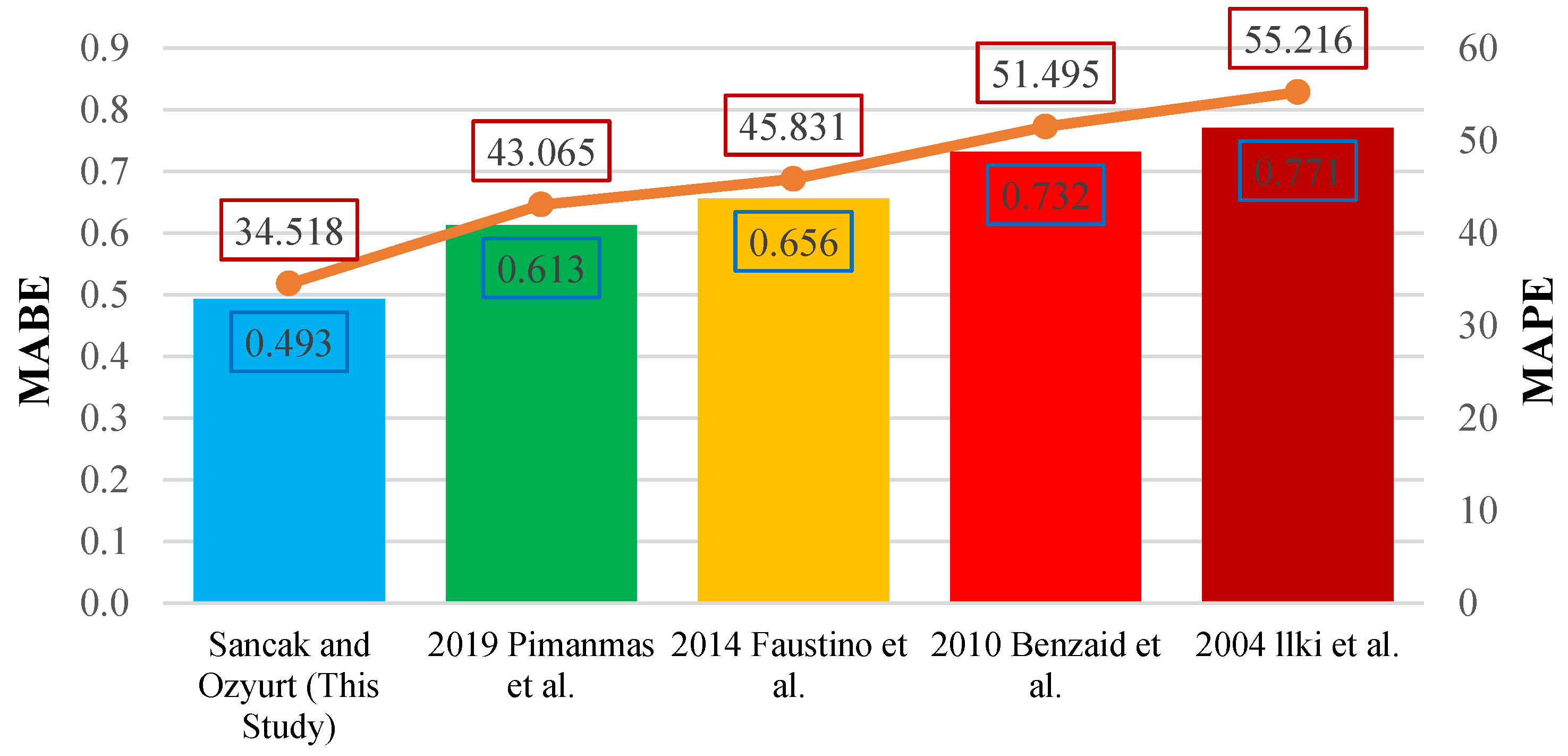

Figure 26.

Comparison of MABE and MAPE for ultimate axial strain models under FRP wrapping effect.

Figure 26.

Comparison of MABE and MAPE for ultimate axial strain models under FRP wrapping effect.

Table 1.

Cement Properties.

Table 1.

Cement Properties.

| Chemical Properties |

Analysis Result |

EN 197-1 Standard Limit Values |

| Lower Limit |

Upper Limit |

| SO3 (%) |

2.97 |

- |

4.0 |

| Cl (%) |

0.0081 |

- |

0.1000 |

| Na2O (%) |

0.67 |

- |

- |

| K2O (%) |

0.28 |

- |

- |

| Loss on Ignition (Fire Loss) (%) |

3.48 |

- |

5.0 |

| Insoluble Residue (%) |

0.77 |

- |

5.0 |

| Physical Properties |

Analysis Result |

EN 197-1 Standard Limit Values |

| Lower Limit |

Upper Limit |

| Specific Gravity |

3.13 |

- |

- |

| Specific Surface (Blaine) (cm2/g) |

3600 |

- |

- |

| Soundness (Le Chatelier) (mm) |

2.0 |

- |

10 |

| Initial Setting Time (min) |

160 |

60 |

- |

| 2 Days Compressive Strength (MPa) |

31.0 |

20 |

- |

| 7 Days Compressive Strength (MPa) |

44.5 |

- |

- |

| 28 Days Compressive Strength (MPa) |

55.6 |

42.5 |

62.5 |

Table 2.

Aggregates and PET granules properties.

Table 2.

Aggregates and PET granules properties.

| |

Coarse |

Fine |

PET |

| Specific Gravity |

2.7 |

2.6 |

1.38 |

| Unit Weight (kg/m3) |

1950 |

1800 |

1280 |

| Size (mm) |

2-22.4 |

0-8 |

2 |

Table 3.

CFRP and GFRP properties.

Table 3.

CFRP and GFRP properties.

| |

CFRP |

GFRP |

| Weaving Type |

Unidirectional |

Plain |

| Weight |

300 g/m2

|

200 g/m2

|

| Tensile strength (MPa) |

3000 |

1500 |

| Modulus of Elasticity (GPa) |

230 |

80 |

| Ultimate strain (%) |

1.3 |

1.9 |

| Thickness (mm) |

0.17 |

0.15 |

Table 4.

Epoxy properties.

Table 4.

Epoxy properties.

| |

Concrete

Adhesion |

Compressive Strength |

Tensile Strength |

Flexural Strength |

Time to Reach Full Strength |

| Teknobond 300 Tix |

(Rupture from Concrete) |

|

|

|

7 days |

Table 5.

Concrete samples.

Table 5.

Concrete samples.

| Sample Name |

Water (kg/m3) |

Cement (kg/m3) |

Gravel (kg/m3) |

Sand (kg/m3) |

PET (kg/m3) |

PET content vol (%) |

Strength Test |

FRP type |

| CS-R-0 |

195 |

390 |

1060 |

730 |

- |

- |

Compressive |

- |

| CS-PET-10 |

195 |

390 |

1060 |

657 |

51.91 |

10 |

Compressive |

- |

| CS-PET-20 |

195 |

390 |

1060 |

584 |

103.82 |

20 |

Compressive |

- |

| CS-PET-30 |

195 |

390 |

1060 |

511 |

155.73 |

30 |

Compressive |

- |

| STS-R-0 |

195 |

390 |

1060 |

730 |

- |

- |

Splitting tensile |

- |

| STS-PET-10 |

195 |

390 |

1060 |

657 |

51.91 |

10 |

Splitting tensile |

- |

| STS-PET-20 |

195 |

390 |

1060 |

584 |

103.82 |

20 |

Splitting tensile |

- |

| STS-PET-30 |

195 |

390 |

1060 |

511 |

155.73 |

30 |

Splitting tensile |

- |

| FS-R-0 |

195 |

390 |

1060 |

730 |

- |

- |

Flexural |

- |

| FS-PET-10 |

195 |

390 |

1060 |

657 |

51.91 |

10 |

Flexural |

- |

| FS-PET-20 |

195 |

390 |

1060 |

584 |

103.82 |

20 |

Flexural |

- |

| FS-PET-30 |

195 |

390 |

1060 |

511 |

155.73 |

30 |

Flexural |

- |

| CS-PET-CFRP-10 |

195 |

390 |

1060 |

657 |

51.91 |

10 |

Compressive |

Carbon |

| CS-PET-GFRP-10 |

195 |

390 |

1060 |

657 |

51.91 |

10 |

Compressive |

Glass |

| STS-PET-CFRP-10 |

195 |

390 |

1060 |

657 |

51.91 |

10 |

Splitting tensile |

Carbon |

| STS-PET-GFRP-10 |

195 |

390 |

1060 |

657 |

51.91 |

10 |

Splitting tensile |

Glass |

| FS-PET-CFRP-10 |

195 |

390 |

1060 |

657 |

51.91 |

10 |

Flexural |

Carbon |

| FS-PET-GFRP-10 |

195 |

390 |

1060 |

657 |

51.91 |

10 |

Flexural |

Glass |

Table 6.

Compressive strength test results of samples without FRP.

Table 6.

Compressive strength test results of samples without FRP.

| Sample Name |

) |

) at Maximum Stress |

) at Maximum Stress |

| CS-R-0 |

26.91 |

0.001967 |

0.000747 |

| CS-PET-10 |

25.11 |

0.002023 |

0.000769 |

| CS-PET-20 |

23.31 |

0.002116 |

0.000857 |

| CS-PET-30 |

21.80 |

0.002123 |

0.000908 |

Table 7.

Compressive strength test results of samples with FRP.

Table 7.

Compressive strength test results of samples with FRP.

| Sample Name |

(MPa) |

(MPa) |

|

|

|

|

| CS-PET-CFRP-10 |

25.11 |

47.86 |

0.002023 |

0.013819 |

0.000769 |

0.008538 |

| CS-PET-GFRP-10 |

25.11 |

38.66 |

0.002023 |

0.014469 |

0.000769 |

0.010028 |

Table 8.

Splitting tensile strength test results.

Table 8.

Splitting tensile strength test results.

| Sample Name |

Split Tensile Strength (MPa) |

| CS-R-0 |

2.46 |

| CS-PET-10 |

2.35 |

| CS-PET-20 |

2.24 |

| CS-PET-30 |

2.16 |

| CS-PET-CFRP-10 |

3.45 |

| CS-PET-GFRP-10 |

3.04 |

Table 9.

Flexural strength test results of samples without FRP.

Table 9.

Flexural strength test results of samples without FRP.

| Sample Name |

Maximum Flexural Stress (MPa) |

Maximum Flexural Strain |

| CS-R-0 |

3.37 |

0.010467 |

| CS-PET-10 |

3.23 |

0.011447 |

| CS-PET-20 |

3.10 |

0.012158 |

| CS-PET-30 |

3.00 |

0.012759 |

Table 10.

Flexural strength test results of samples with FRP.

Table 10.

Flexural strength test results of samples with FRP.

| Sample Name |

Maximum Flexural Stress (MPa) |

Maximum Flexural Strain |

| CS-PET-CFRP-10 |

4.59 |

0.061819 |

| CS-PET-GFRP-10 |

4.09 |

0.066795 |

Table 11.

Elasticity modules of the samples.

Table 11.

Elasticity modules of the samples.

| Sample Name |

) |

) |

| CS-R-0 |

30574.17 |

- |

| CS-PET-10 |

27221.85 |

- |

| CS-PET-20 |

25061.49 |

- |

| CS-PET-30 |

21320.87 |

- |

| CS-PET-CFRP-10 |

27512.26 |

1704.56 |

| CS-PET-GFRP-10 |

27465.83 |

988.90 |

Table 12.

Statistical metrics.

Table 12.

Statistical metrics.

| Metrics |

Equation |

Information |

| R2

|

|

This method shows how well a model predicts measured data, with an R² value between 0 and 1. A value closer to 1 indicates better performance [40,41]. |

| MABE |

|

MABE represents the absolute bias error and reflects the quality of the correlation. A value close to zero is preferred. It gives insight into the long-term performance of the prediction models [40]. |

| MAPE |

|

MAPE measures the average percentage of absolute prediction errors relative to the actual data values. A lower MAPE indicates better model performance [40,41]. |

Table 13.

PET substituted concrete experimental database.

Table 13.

PET substituted concrete experimental database.

| Type of substitution |

Year |

Reference |

28 day CS Test (mm) |

28 day TS Test (mm) |

28 day FS Test (mm) |

PET Specific Gravity |

PET Bulk Density (kg/m3) |

PET Size (mm) |

PET (%) |

Concrete Density (kg/m3) |

W/C Ratio |

28 day CS (MPa) |

28 day Cylindrical CS (MPa) |

28 day TS (MPa) |

28 day Cylindrical TS (MPa) |

28 day FS (MPa) |

MoE (GPa) |

Slump (mm) |

| Vol |

2005 |

Choi et al. [10] |

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

|

|

|

|

0 |

2300 |

0.53 |

31.5 |

|

3.27 |

|

|

23.5 |

100 |

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

|

1.39 |

844 |

5-15 |

25 |

2220 |

0.53 |

29.7 |

|

2.65 |

|

|

23 |

153 |

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

|

1.39 |

844 |

5-15 |

50 |

2130 |

0.53 |

26.3 |

|

2.25 |

|

|

21.2 |

199 |

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

|

1.39 |

844 |

5-15 |

75 |

2010 |

0.53 |

21.8 |

|

2.04 |

|

|

18.5 |

223 |

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

|

|

|

|

0 |

2300 |

0.49 |

34.6 |

|

3.27 |

|

|

23.3 |

105 |

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

|

1.39 |

844 |

5-15 |

25 |

2230 |

0.49 |

33.7 |

|

2.76 |

|

|

22.8 |

154 |

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

|

1.39 |

844 |

5-15 |

50 |

2120 |

0.49 |

29.1 |

|

2.35 |

|

|

18.1 |

180 |

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

|

1.39 |

844 |

5-15 |

75 |

2000 |

0.49 |

23.2 |

|

1.94 |

|

|

16.7 |

214 |

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

|

|

|

|

0 |

2300 |

0.45 |

37.2 |

|

3.32 |

|

|

25.5 |

135 |

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

|

1.39 |

844 |

5-15 |

25 |

2260 |

0.45 |

33.8 |

|

2.8 |

|

|

18.7 |

169 |

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

|

1.39 |

844 |

5-15 |

50 |

2160 |

0.45 |

31.8 |

|

2.55 |

|

|

17.3 |

184 |

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

|

1.39 |

844 |

5-15 |

75 |

1940 |

0.45 |

24.9 |

|

2.04 |

|

|

15.6 |

205 |

| Vol |

2009 |

Choi et al. [11] |

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

|

|

|

|

0 |

2300 |

0.53 |

32.05 |

|

3.26 |

|

|

23.45 |

100 |

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

|

1.39 |

844 |

5-15 |

25 |

2218.29 |

0.53 |

30.34 |

|

2.62 |

|

|

22.63 |

153 |

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

|

1.39 |

844 |

5-15 |

50 |

2130.59 |

0.53 |

26.75 |

|

2.24 |

|

|

21.19 |

199 |

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

|

1.39 |

844 |

5-15 |

75 |

2011.55 |

0.53 |

22.56 |

|

2.07 |

|

|

18.83 |

223 |

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

|

|

|

|

0 |

2300 |

0.49 |

36.1 |

|

3.26 |

|

|

18.22 |

105 |

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

|

1.39 |

844 |

5-15 |

25 |

2228.19 |

0.49 |

34.77 |

|

2.76 |

|

|

23.16 |

154 |

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

|

1.39 |

844 |

5-15 |

50 |

2117.39 |

0.49 |

29.82 |

|

2.34 |

|

|

17.97 |

180 |

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

|

1.39 |

844 |

5-15 |

75 |

1997.53 |

0.49 |

24.33 |

|

1.97 |

|

|

16.99 |

214 |

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

|

|

|

|

0 |

2300 |

0.45 |

37.81 |

|

3.31 |

|

|

25.43 |

135 |

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

|

1.39 |

844 |

5-15 |

25 |

2260.35 |

0.45 |

34.06 |

|

2.72 |

|

|

22.34 |

169 |

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

|

1.39 |

844 |

5-15 |

50 |

2160.28 |

0.45 |

32.31 |

|

2.53 |

|

|

17.23 |

184 |

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

|

1.39 |

844 |

5-15 |

75 |

1941.45 |

0.45 |

27.59 |

|

2.08 |

|

|

15.89 |

205 |

| Vol |

2009 |

Albano et al. [12] |

150x300 cylinders |

150x300 cylinders |

ASTM C 78 |

|

|

|

0 |

|

0.5 |

27.86 |

|

2.79 |

|

4.25 |

29.48 |

86.9 |

| |

|

|

150x300 cylinders |

150x300 cylinders |

ASTM C 78 |

|

|

2.6 |

10 |

|

0.5 |

22.81 |

|

2.45 |

|

4.58 |

22.33 |

64.7 |

| |

|

|

150x300 cylinders |

150x300 cylinders |

ASTM C 78 |

|

|

2.6-11.4 |

10 |

|

0.5 |

22.4 |

|

2.51 |

|

4.64 |

22.85 |

74.5 |

| |

|

|

150x300 cylinders |

150x300 cylinders |

ASTM C 78 |

|

|

11.4 |

10 |

|

0.5 |

22.04 |

|

2.37 |

|

3.68 |

21.1 |

69.4 |

| |

|

|

150x300 cylinders |

150x300 cylinders |

ASTM C 78 |

|

|

2.6 |

20 |

|

0.5 |

17.4 |

|

1.89 |

|

3.51 |

16.16 |

42.1 |

| |

|

|

150x300 cylinders |

150x300 cylinders |

ASTM C 78 |

|

|

2.6-11.4 |

20 |

|

0.5 |

18.31 |

|

2.19 |

|

4.11 |

16.1 |

49.5 |

| |

|

|

150x300 cylinders |

150x300 cylinders |

ASTM C 78 |

|

|

11.4 |

20 |

|

0.5 |

13.9 |

|

1.91 |

|

1.65 |

15.06 |

0.01 |

| |

|

|

150x300 cylinders |

150x300 cylinders |

ASTM C 78 |

|

|

|

0 |

|

0.6 |

21.26 |

|

2.33 |

|

3.83 |

22.59 |

79.3 |

| |

|

|

150x300 cylinders |

150x300 cylinders |

ASTM C 78 |

|

|

2.6 |

10 |

|

0.6 |

16.68 |

|

1.69 |

|

4.04 |

18.18 |

40 |

| |

|

|

150x300 cylinders |

150x300 cylinders |

ASTM C 78 |

|

|

2.6-11.4 |

10 |

|

0.6 |

18.25 |

|

2.17 |

|

3.51 |

18.44 |

52.6 |

| |

|

|

150x300 cylinders |

150x300 cylinders |

ASTM C 78 |

|

|

11.4 |

10 |

|

0.6 |

13.95 |

|

2.25 |

|

3.44 |

20.64 |

30.3 |

| |

|

|

150x300 cylinders |

150x300 cylinders |

ASTM C 78 |

|

|

2.6 |

20 |

|

0.6 |

13.07 |

|

1.45 |

|

2.95 |

14.02 |

23 |

| |

|

|

150x300 cylinders |

150x300 cylinders |

ASTM C 78 |

|

|

2.6-11.4 |

20 |

|

0.6 |

12.75 |

|

1.74 |

|

2.79 |

15.97 |

20 |

| |

|

|

150x300 cylinders |

150x300 cylinders |

ASTM C 78 |

|

|

11.4 |

20 |

|

0.6 |

8.97 |

|

1.49 |

|

2.32 |

11.68 |

0.01 |

| Vol |

2013 |

Rahmani et al. [13] |

100x200 cylinders |

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

0.42 |

42.12 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

|

|

1.11 |

464 |

<7 |

5 |

|

0.42 |

44.27 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

|

|

1.11 |

464 |

<7 |

10 |

|

0.42 |

41.94 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

|

|

1.11 |

464 |

<7 |

15 |

|

0.42 |

38.75 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

0.54 |

33.39 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

|

|

1.11 |

464 |

<7 |

5 |

|

0.54 |

37.55 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

|

|

1.11 |

464 |

<7 |

10 |

|

0.54 |

33.68 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

|

|

1.11 |

464 |

<7 |

15 |

|

0.54 |

29.57 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

150x300 cylinders |

150x300 cylinders |

100x100x500 |

|

|

|

0 |

2281.58 |

0.42 |

38.71 |

|

3.98 |

|

6.27 |

36.38 |

70 |

| |

|

|

150x300 cylinders |

150x300 cylinders |

100x100x500 |

1.11 |

464 |

<7 |

5 |

2258.6 |

0.42 |

42.14 |

|

3.89 |

|

6.55 |

33.8 |

60 |

| |

|

|

150x300 cylinders |

150x300 cylinders |

100x100x500 |

1.11 |

464 |

<7 |

10 |

2238.85 |

0.42 |

39.71 |

|

3.66 |

|

5.92 |

31.45 |

50 |

| |

|

|

150x300 cylinders |

150x300 cylinders |

100x100x500 |

1.11 |

464 |

<7 |

15 |

2209.43 |

0.42 |

36.73 |

|

3.35 |

|

5.4 |

28.61 |

40 |

| |

|

|

150x300 cylinders |

150x300 cylinders |

100x100x500 |

|

|

|

0 |

2221.83 |

0.54 |

31.58 |

|

3.76 |

|

5.64 |

33.81 |

80 |

| |

|

|

150x300 cylinders |

150x300 cylinders |

100x100x500 |

1.11 |

464 |

<7 |

5 |

2207.28 |

0.54 |

35.36 |

|

3.55 |

|

6.03 |

31.2 |

65 |

| |

|

|

150x300 cylinders |

150x300 cylinders |

100x100x500 |

1.11 |

464 |

<7 |

10 |

2175.87 |

0.54 |

31.76 |

|

3.25 |

|

5.49 |

28.79 |

50 |

| |

|

|

150x300 cylinders |

150x300 cylinders |

100x100x500 |

1.11 |

464 |

<7 |

15 |

2147.68 |

0.54 |

28.91 |

|

2.98 |

|

5.2 |

25.85 |

35 |

| |

|

|

50 cubes |

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

0.42 |

55.4 |

44.32 |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

50 cubes |

|

|

1.11 |

464 |

<7 |

5 |

|

0.42 |

59.51 |

47.61 |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

50 cubes |

|

|

1.11 |

464 |

<7 |

10 |

|

0.42 |

55.5 |

44.40 |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

50 cubes |

|

|

1.11 |

464 |

<7 |

15 |

|

0.42 |

52.07 |

41.66 |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

50 cubes |

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

0.54 |

46.17 |

36.94 |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

50 cubes |

|

|

1.11 |

464 |

<7 |

5 |

|

0.54 |

49.8 |

39.84 |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

50 cubes |

|

|

1.11 |

464 |

<7 |

10 |

|

0.54 |

45.88 |

36.70 |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

50 cubes |

|

|

1.11 |

464 |

<7 |

15 |

|

0.54 |

42.09 |

33.67 |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

100 cubes |

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

0.42 |

54.49 |

43.59 |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

100 cubes |

|

|

1.11 |

464 |

<7 |

5 |

|

0.42 |

55.56 |

44.45 |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

100 cubes |

|

|

1.11 |

464 |

<7 |

10 |

|

0.42 |

52.55 |

42.04 |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

100 cubes |

|

|

1.11 |

464 |

<7 |

15 |

|

0.42 |

50.46 |

40.37 |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

100 cubes |

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

0.54 |

41.85 |

33.48 |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

100 cubes |

|

|

1.11 |

464 |

<7 |

5 |

|

0.54 |

48.01 |

38.41 |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

100 cubes |

|

|

1.11 |

464 |

<7 |

10 |

|

0.54 |

43.09 |

34.47 |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

100 cubes |

|

|

1.11 |

464 |

<7 |

15 |

|

0.54 |

41.57 |

33.26 |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

150 cubes |

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

0.42 |

52.2 |

41.76 |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

150 cubes |

|

|

1.11 |

464 |

<7 |

5 |

|

0.42 |

53.24 |

42.59 |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

150 cubes |

|

|

1.11 |

464 |

<7 |

10 |

|

0.42 |

50.52 |

40.42 |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

150 cubes |

|

|

1.11 |

464 |

<7 |

15 |

|

0.42 |

46.59 |

37.27 |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

150 cubes |

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

0.54 |

41.1 |

32.88 |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

150 cubes |

|

|

1.11 |

464 |

<7 |

5 |

|

0.54 |

44.76 |

35.81 |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

150 cubes |

|

|

1.11 |

464 |

<7 |

10 |

|

0.54 |

39.94 |

31.95 |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

150 cubes |

|

|

1.11 |

464 |

<7 |

15 |

|

0.54 |

38.52 |

30.82 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Vol |

2013 |

Saikia and De Brito [14] |

NP EN 12390-3 |

NP EN 12390-6 |

NP EN 12390-5 |

|

|

|

0 |

2409.41 |

0.53 |

43.07 |

34.46 |

3.49 |

|

4.74 |

|

|

| |

|

|

NP EN 12390-3 |

NP EN 12390-6 |

NP EN 12390-5 |

1.34 |

555 |

0.5-4 |

5 |

2347.61 |

0.57 |

36.11 |

28.89 |

3.07 |

|

4.26 |

|

|

| |

|

|

NP EN 12390-3 |

NP EN 12390-6 |

NP EN 12390-5 |

1.34 |

555 |

0.5-4 |

10 |

2304.07 |

0.6 |

30.79 |

24.63 |

2.83 |

|

3.76 |

|

|

| |

|

|

NP EN 12390-3 |

NP EN 12390-6 |

NP EN 12390-5 |

1.34 |

555 |

0.5-4 |

15 |

2231.04 |

0.64 |

25.33 |

20.26 |

2.28 |

|

2.99 |

|

|

| |

|

|

NP EN 12390-3 |

NP EN 12390-6 |

NP EN 12390-5 |

1.34 |

827 |

0.5-4 |

5 |

2364.47 |

0.53 |

37.82 |

30.26 |

3.21 |

|

4.54 |

|

|

| |

|

|

NP EN 12390-3 |

NP EN 12390-6 |

NP EN 12390-5 |

1.34 |

827 |

0.5-4 |

10 |

2339.89 |

0.52 |

36.86 |

29.49 |

3.13 |

|

4.24 |

|

|

| |

|

|

NP EN 12390-3 |

NP EN 12390-6 |

NP EN 12390-5 |

1.34 |

827 |

0.5-4 |

15 |

2304.07 |

0.52 |

33.41 |

26.73 |

2.87 |

|

3.98 |

|

|

| Vol |

2013 |

Juki et al. [15] |

BS 1881-Part 116-83 |

BS 1881: Part 117 |

|

|

|

|

0 |

2386.18 |

0.45 |

31.34 |

25.07 |

3.21 |

|

|

31.29 |

|

| |

|

|

BS 1881-Part 116-83 |

BS 1881: Part 117 |

|

|

|

<5 |

25 |

2290.85 |

0.45 |

27.91 |

22.33 |

2.7 |

|

|

26.89 |

|

| |

|

|

BS 1881-Part 116-83 |

BS 1881: Part 117 |

|

|

|

<5 |

50 |

2209.76 |

0.45 |

22.99 |

18.39 |

2.02 |

|

|

21.55 |

|

| |

|

|

BS 1881-Part 116-83 |

BS 1881: Part 117 |

|

|

|

<5 |

75 |

2041.87 |

0.45 |

17.04 |

13.63 |

1.57 |

|

|

10.33 |

|

| |

|

|

BS 1881-Part 116-83 |

BS 1881: Part 117 |

|

|

|

|

0 |

2371.95 |

0.55 |

26.76 |

21.41 |

3.52 |

|

|

30.87 |

|

| |

|

|

BS 1881-Part 116-83 |

BS 1881: Part 117 |

|

|

|

<5 |

25 |

2315.04 |

0.55 |

25.39 |

20.31 |

2.98 |

|

|

18.71 |

|

| |

|

|

BS 1881-Part 116-83 |

BS 1881: Part 117 |

|

|

|

<5 |

50 |

2249.59 |

0.55 |

20.36 |

16.29 |

2.38 |

|

|

16.12 |

|

| |

|

|

BS 1881-Part 116-83 |

BS 1881: Part 117 |

|

|

|

<5 |

75 |

2232.52 |

0.55 |

15.78 |

12.62 |

2.02 |

|

|

10.07 |

|

| |

|

|

BS 1881-Part 116-83 |

BS 1881: Part 117 |

|

|

|

|

0 |

2380.49 |

0.65 |

25.39 |

20.31 |

2.97 |

|

|

36.73 |

|

| |

|

|

BS 1881-Part 116-83 |

BS 1881: Part 117 |

|

|

|

<5 |

25 |

2286.59 |

0.65 |

25.28 |

20.22 |

2.21 |

|

|

25.82 |

|

| |

|

|

BS 1881-Part 116-83 |

BS 1881: Part 117 |

|

|

|

<5 |

50 |

2262.4 |

0.65 |

19.22 |

15.38 |

1.42 |

|

|

18.68 |

|

| |

|

|

BS 1881-Part 116-83 |

BS 1881: Part 117 |

|

|

|

<5 |

75 |

2185.57 |

0.65 |

15.56 |

12.45 |

1.19 |

|

|

13.65 |

|

| Vol |

2013 |

Juki et al. [16] |

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

100x100x500 |

|

|

|

0 |

2372.59 |

0.55 |

26.69 |

|

3.52 |

|

4.99 |

30 |

|

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

100x100x500 |

|

|

<5 |

25 |

2343.22 |

0.55 |

22.83 |

|

2.99 |

|

4.75 |

23 |

|

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

100x100x500 |

|

|

<5 |

50 |

2322.79 |

0.55 |

20.37 |

|

2.38 |

|

3.8 |

15 |

|

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

100x100x500 |

|

|

<5 |

75 |

2231.94 |

0.55 |

15.2 |

|

2.02 |

|

2.61 |

9 |

|

| Vol |

2014 |

Saikia and De Brito [17] |

150 cubes |

100x150 cylinders |

150x150x600 |

|

|

|

0 |

2387 |

0.53 |

42.96 |

34.37 |

3.45 |

|

4.72 |

39.79 |

127 |

| |

|

|

150 cubes |

100x150 cylinders |

150x150x600 |

1.32 |

555 |

0.5-4 |

5 |

2336 |

0.57 |

36.2 |

28.96 |

3.12 |

|

4.36 |

35.1 |

122 |

| |

|

|

150 cubes |

100x150 cylinders |

150x150x600 |

1.32 |

555 |

0.5-4 |

10 |

2290 |

0.6 |

30.92 |

24.74 |

2.66 |

|

3.75 |

29.9 |

122 |

| |

|

|

150 cubes |

100x150 cylinders |

150x150x600 |

1.32 |

555 |

0.5-4 |

15 |

2243 |

0.64 |

25.53 |

20.42 |

2.22 |

|

2.98 |

24.69 |

120 |

| |

|

|

150 cubes |

100x150 cylinders |

150x150x600 |

1.36 |

827 |

0.5-4 |

5 |

2347 |

0.53 |

37.78 |

30.22 |

3.29 |

|

4.51 |

36.15 |

122 |

| |

|

|

150 cubes |

100x150 cylinders |

150x150x600 |

1.36 |

827 |

0.5-4 |

10 |

2297 |

0.52 |

36.9 |

29.52 |

3.16 |

|

4.24 |

35.94 |

122 |

| |

|

|

150 cubes |

100x150 cylinders |

150x150x600 |

1.36 |

827 |

0.5-4 |

15 |

2254 |

0.52 |

33.19 |

26.55 |

2.81 |

|

3.97 |

31.04 |

132 |

| Vol |

2017 |

Mohammed [18] |

100x200 cylinders |

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

2375 |

0.5 |

33.07 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

|

|

|

353 |

3-12 |

5 |

2362 |

0.5 |

27.05 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

|

|

|

353 |

3-12 |

10 |

2407 |

0.5 |

31.82 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

|

|

|

353 |

3-12 |

15 |

2348 |

0.5 |

32.57 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

2350 |

0.5 |

31.36 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

|

|

|

353 |

3-12 |

5 |

2303 |

0.5 |

23.81 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

|

|

|

353 |

3-12 |

10 |

2317 |

0.5 |

24.92 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

|

|

|

353 |

3-12 |

15 |

2314 |

0.5 |

23.66 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Vol |

2018 |

Al-Hadithi and Al-Ani [19] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

2350.51 |

0.29 |

69 |

55.20 |

|

|

|

43.06 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

1.29 |

447 |

<4.75 |

2.5 |

2339.36 |

0.29 |

60.38 |

48.30 |

|

|

|

40.81 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

1.29 |

447 |

<4.75 |

5 |

2331.92 |

0.29 |

56.93 |

45.54 |

|

|

|

40.76 |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

1.29 |

447 |

<4.75 |

7.5 |

2313.35 |

0.29 |

50.35 |

40.28 |

|

|

|

40.52 |

|

| Vol |

2022 |

Kangavar et al. [20] |

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

150x150x700 |

|

|

|

0 |

2417 |

0.45 |

34.23 |

|

3.96 |

|

3.96 |

24.41 |

98 |

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

150x150x700 |

1.34 |

1380 |

<4.75 |

10 |

2340 |

0.45 |

37.34 |

|

4.3 |

|

4.33 |

24.13 |

98 |

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

150x150x700 |

1.34 |

1380 |

<4.75 |

30 |

2125 |

0.45 |

33.78 |

|

3.81 |

|

3.99 |

20.25 |

94 |

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

150x150x700 |

1.34 |

1380 |

<4.75 |

50 |

1845 |

0.45 |

25.16 |

|

3.31 |

|

3.47 |

18.93 |

90 |

| Vol |

2022 |

Babafemi et al. [21] |

100 cubes |

100 cubes |

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

0.5 |

36.37 |

29.10 |

4.01 |

3.21 |

|

|

100 |

| |

|

|

100 cubes |

100 cubes |

|

1.47 |

|

<3 |

5 |

|

0.5 |

37.37 |

29.90 |

3.81 |

3.05 |

|

|

100 |

| |

|

|

100 cubes |

100 cubes |

|

1.47 |

|

<3 |

10 |

|

0.5 |

37.27 |

29.82 |

3.63 |

2.90 |

|

|

124 |

| |

|

|

100 cubes |

100 cubes |

|

1.47 |

|

<3 |

15 |

|

0.5 |

35 |

28.00 |

3.57 |

2.86 |

|

|

135 |

| Vol |

2022 |

Hama [22] |

150x300 cylinders |

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

2428 |

0.42 |

35.76 |

|

|

|

|

27.4 |

96 |

| |

|

|

150x300 cylinders |

|

|

1.36 |

|

<4.75 |

10 |

2392 |

0.42 |

36.8 |

|

|

|

|

24.05 |

94 |

| |

|

|

150x300 cylinders |

|

|

1.36 |

|

<4.75 |

15 |

2374 |

0.42 |

34.78 |

|

|

|

|

22.31 |

92 |

| |

|

|

150x300 cylinders |

|

|

1.36 |

|

<4.75 |

20 |

2358 |

0.42 |

28.48 |

|

|

|

|

21.82 |

86 |

| |

|

|

150x300 cylinders |

|

|

1.36 |

|

<4.75 |

25 |

2340 |

0.42 |

25.63 |

|

|

|

|

20.42 |

80 |

| Vol |

2023 |

Xiong et al. [23] |

150x300 cylinders |

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

2454 |

0.44 |

53.2 |

|

|

|

|

30.15 |

235 |

| |

|

|

150x300 cylinders |

|

|

|

|

≤1.6 |

5 |

2424 |

0.44 |

50.2 |

|

|

|

|

24.93 |

215 |

| |

|

|

150x300 cylinders |

|

|

|

|

≤1.6 |

10 |

2420 |

0.44 |

46.9 |

|

|

|

|

26.9 |

200 |

| |

|

|

150x300 cylinders |

|

|

|

|

≤1.6 |

20 |

2412 |

0.44 |

43.7 |

|

|

|

|

24.94 |

205 |

| |

|

|

150x300 cylinders |

|

|

|

|

≤1.6 |

30 |

2389 |

0.44 |

40.8 |

|

|

|

|

21.87 |

180 |

| Vol |

This Year |

Sancak and Ozyurt |

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

100x100x400 |

|

|

|

0 |

2307.88 |

0.5 |

26.91 |

|

2.46 |

|

3.37 |

30.57 |

48 |

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

100x100x400 |

1.39 |

1280 |

2 |

10 |

2271.66 |

0.5 |

25.11 |

|

2.35 |

|

3.23 |

27.22 |

45 |

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

100x100x400 |

1.39 |

1280 |

2 |

20 |

2234.49 |

0.5 |

23.31 |

|

2.24 |

|

3.1 |

25.06 |

40 |

| |

|

|

100x200 cylinders |

100x200 cylinders |

100x100x400 |

1.39 |

1280 |

2 |

30 |

2177.94 |

0.5 |

21.8 |

|

2.16 |

|

2.3 |

21.32 |

38 |

| Wei |

2008 |

Ismail and AL-Hashmi [24] |

150 cubes |

|

ASTM C293 |

|

|

|

0 |

2399.02 |

0.53 |

44 |

35.20 |

|

|

5.88 |

|

75 |

| |

|

|

150 cubes |

|

ASTM C293 |

|

368.7 |

0.5-12 |

10 |

2307.11 |

0.53 |

33.23 |

26.58 |

|

|

4.59 |

|

24 |

| |

|

|

150 cubes |

|

ASTM C293 |

|

368.7 |

0.5-12 |

15 |

2244.68 |

0.53 |

29.64 |

23.71 |

|

|

4.26 |

|

9 |

| |

|

|

150 cubes |

|

ASTM C293 |

|

368.7 |

0.5-12 |

20 |

2223.87 |

0.53 |

29.63 |

23.70 |

|

|

4.06 |

|

3 |

| Wei |

2010 |

Frigione et al. [25] |

150 cubes |

150x300 cylinders |

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

0.45 |

68 |

54.40 |

6.1 |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

150 cubes |

150x300 cylinders |

|

1.32 |

660 |

<2.36 |

5 |

|

0.45 |

67.5 |

54.00 |

6 |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

150 cubes |

150x300 cylinders |

|

1.32 |

660 |

<2.36 |

0 |

|

0.55 |

41.5 |

33.20 |

4.2 |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

150 cubes |

150x300 cylinders |

|

1.32 |

660 |

<2.36 |

5 |

|

0.55 |

40.7 |

32.56 |

4.1 |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

150 cubes |

150x300 cylinders |

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

0.45 |

70 |

56.00 |

6.3 |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

150 cubes |

150x300 cylinders |

|

1.32 |

660 |

<2.36 |

5 |

|

0.45 |

69.7 |

55.76 |

6.3 |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

150 cubes |

150x300 cylinders |

|

1.32 |

660 |

<2.36 |

0 |

|

0.55 |

44 |

35.20 |

4.7 |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

150 cubes |

150x300 cylinders |

|

1.32 |

660 |

<2.36 |

5 |

|

0.55 |

43.2 |

34.56 |

4.6 |

|

|

|

|

| Wei |

2011 |

Galvao et al. [26] |

NBR 5739/07 |

NBR 7222/94 |

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

0.45 |

34.13 |

|

3.35 |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

NBR 5739/07 |

NBR 7222/94 |

|

1.32 |

|

1.2-12.5 |

0.5 |

|

0.45 |

37.67 |

|

3.75 |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

NBR 5739/07 |

NBR 7222/94 |

|

1.32 |

|

1.2-12.5 |

1 |

|

0.45 |

39.52 |

|

3.6 |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

NBR 5739/07 |

NBR 7222/94 |

|

1.32 |

|

1.2-12.5 |

2.5 |

|

0.45 |

35.98 |

|

3.69 |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

NBR 5739/07 |

NBR 7222/94 |

|

1.32 |

|

1.2-12.5 |

5 |

|

0.45 |

34.13 |

|

3.3 |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

NBR 5739/07 |

NBR 7222/94 |

|

1.32 |

|

1.2-12.5 |

7.5 |

|

0.45 |

28.9 |

|

3.49 |

|

|

|

|

| Wei |

2016 |

Azhdarpour et al. [27] |

150x300 cylinders |

150x300 cylinders |

130x150x450 |

|

|

|

0 |

2158.05 |

0.5 |

35 |

|

2.5 |

|

4.4 |

48.87 |

|

| |

|

|

150x300 cylinders |

150x300 cylinders |

130x150x450 |

1.38 |

|

0.05-4.9 |

5 |

2119.02 |

0.5 |

51 |

|

3.1 |

|

6.1 |

|

|

| |

|

|

150x300 cylinders |

150x300 cylinders |

130x150x450 |

1.38 |

|

0.05-4.9 |

10 |

2087.93 |

0.5 |

38 |

|

3.3 |

|

4.9 |

27.06 |

|

| |

|

|

150x300 cylinders |

150x300 cylinders |

130x150x450 |

1.38 |

|

0.05-4.9 |

15 |

2050.12 |

0.5 |

31 |

|

2.9 |

|

4.8 |

|

|

| |

|

|

150x300 cylinders |

150x300 cylinders |

130x150x450 |

1.38 |

|

0.05-4.9 |

20 |

2014.15 |

0.5 |

29 |

|

2.8 |

|

4.3 |

16.98 |

|

| |

|

|

150x300 cylinders |

150x300 cylinders |

130x150x450 |

1.38 |

|

0.05-4.9 |

25 |

1979.39 |

0.5 |

22 |

|

2.2 |

|

4.1 |

|

|

| |

|

|

150x300 cylinders |

150x300 cylinders |

130x150x450 |

1.38 |

|

0.05-4.9 |

30 |

1935.49 |

0.5 |

19 |

|

1.6 |

|

3 |

9.44 |

|

| Wei |

2016 |

Norhana et al. [28] |

100 cubes |

|

100x100x500 |

|

|

|

0 |

|

0.5 |

44 |

35.20 |

|

|

5.6 |

|

|

| |

|

|

100 cubes |

|

100x100x500 |

|

|

<5 |

10 |

|

0.5 |

35 |

28.00 |

|

|

4.7 |

|

|

| |

|

|

100 cubes |

|

100x100x500 |

|

|

<5 |

20 |

|

0.5 |

30 |

24.00 |

|

|

4.5 |

|

|

| |

|

|

100 cubes |

|

100x100x500 |

|

|

<5 |

30 |

|

0.5 |

24 |

19.20 |

|

|

4.3 |

|

|

| Wei |

2018 |

Saxena et al. [29] |

100 cubes |

|

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

0.45 |

26.7 |

21.36 |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

100 cubes |

|

|

|

|

<4.75 |

5 |

|

0.45 |

26.11 |

20.89 |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

100 cubes |

|

|

|

|

<4.75 |

10 |

|

0.45 |

25.61 |

20.49 |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

100 cubes |

|

|

|

|

<4.75 |

15 |

|

0.45 |

13.89 |

11.11 |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

100 cubes |

|

|

|

|

<4.75 |

20 |

|

0.45 |

5.4 |

4.32 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Wei |

2020 |

Almeshal et al. [30] |

BS 1881 |

ASTM C 496 |

ASTM C 293 |

|

|

|

0 |

2394.91 |

0.54 |

35.6 |

28.48 |

3.11 |

|

7.64 |

|

89 |

| |

|

|

BS 1881 |

ASTM C 496 |

ASTM C 293 |

|

1410 |

0.075-4 |

10 |

2369.21 |

0.54 |

35.2 |

28.16 |

2.78 |

|

7.46 |

|

78 |

| |

|

|

BS 1881 |

ASTM C 496 |

ASTM C 293 |

|

1410 |

0.075-4 |

20 |

2297.42 |

0.54 |

34.11 |

27.29 |

2.51 |

|

6.83 |

|

62 |

| |

|

|

BS 1881 |

ASTM C 496 |

ASTM C 293 |

|

1410 |

0.075-4 |

30 |

2211.46 |

0.54 |

24.58 |

19.66 |

2.01 |

|

5.92 |

|

44 |

| |

|

|

BS 1881 |

ASTM C 496 |

ASTM C 293 |

|

1410 |

0.075-4 |

40 |

1992.73 |

0.54 |

14.25 |

11.40 |

1.74 |

|

3.21 |

|

23 |

| |

|

|

BS 1881 |

ASTM C 496 |

ASTM C 293 |

|

1410 |

0.075-4 |

50 |

1806.12 |

0.54 |

3.36 |

2.69 |

0.45 |

|

1.21 |

|

10 |

| Wei |

2021 |

Bamigboye et al. [31] |

ASTM. C39/C39M-20 |

100x200 cylinders |

|

|

|

|

0 |

|

0.55 |

31 |

|

3.2 |

|

|

|

30 |

| |

|

|

ASTM. C39/C39M-20 |

100x200 cylinders |

|

|

|

0.075-5 |

10 |

|

0.55 |

22.3 |

|

2.81 |

|

|

|

45 |

| |

|

|

ASTM. C39/C39M-20 |

100x200 cylinders |

|

|

|

0.075-5 |

20 |

|

0.55 |

22 |

|

2.57 |

|

|

|

60 |

| |

|

|

ASTM. C39/C39M-20 |

100x200 cylinders |

|

|

|

0.075-5 |

30 |

|

0.55 |

21.7 |

|

2.45 |

|

|

|

100 |

| |

|

|

ASTM. C39/C39M-20 |

100x200 cylinders |

|

|

|

0.075-5 |

40 |

|

0.55 |

20.7 |

|

2.41 |

|

|

|

105 |

| |

|

|

ASTM. C39/C39M-20 |

100x200 cylinders |

|

|

|

0.075-5 |

100 |

|

0.55 |

16.3 |

|

2.02 |

|

|

|

40 |

| Wei |

2021 |

Dawood et al. [32] |

150 cubes |

100x200 cylinders |

100x100x500 |

1.38 |

|

0.6-3 |

0 |

2361.39 |

0.41 |

34.79 |

27.83 |

2.41 |

|

4.54 |

27.14 |

160 |

| |

|

|

150 cubes |

100x200 cylinders |

100x100x500 |

1.38 |

|

0.6-3 |

5 |

2355.57 |

0.41 |

46.79 |

37.43 |

2.6 |

|

5.76 |

24.47 |

140 |

| |

|

|

150 cubes |

100x200 cylinders |

100x100x500 |

1.38 |

|

0.6-3 |

7.5 |

2303.61 |

0.41 |

49.58 |

39.66 |

3.06 |

|

5.88 |

22.65 |

130 |

| |

|

|

150 cubes |

100x200 cylinders |

100x100x500 |

1.38 |

|

0.6-3 |

10 |

2296.58 |

0.41 |

44.92 |

35.94 |

2.86 |

|

5.71 |

22.62 |

120 |

| |

|

|

150 cubes |

100x200 cylinders |

100x100x500 |

1.38 |

|

0.6-3 |

12.5 |

2278.16 |

0.41 |

43.3 |

34.64 |

2.86 |

|

5.33 |

22.39 |

100 |

| |

|

|

150 cubes |

100x200 cylinders |

100x100x500 |

1.38 |

|

0.6-3 |

15 |

2223.04 |

0.41 |

35.62 |

28.50 |

2.43 |

|

4.53 |

22.06 |

80 |

| |

|

|

150 cubes |

100x200 cylinders |

100x100x500 |

1.38 |

|

0.6-3 |

20 |

2193.79 |

0.41 |

32.75 |

26.20 |

2.32 |

|

4.33 |

21.08 |

60 |

| Wei |

2021 |

Tayeh et al. [33] |

100 cubes |

150x300 cylinders |

100x100x500 |

0.9-0.96 |

|

0.075-2 |

0 |

2448.34 |

0.51 |

39.76 |

31.81 |

5.56 |

|

7.96 |

|

103 |

| |

|

|

100 cubes |

150x300 cylinders |

100x100x500 |

0.9-0.96 |

|

0.075-2 |

10 |

2442.22 |

0.51 |

39.01 |

31.21 |

5.25 |

|

7.65 |

|

138 |

| |

|

|

100 cubes |

150x300 cylinders |

100x100x500 |

0.9-0.96 |

|

0.075-2 |

20 |

2400.41 |

0.51 |

33.59 |

26.87 |

5.13 |

|

7.43 |

|

175 |

| |

|

|

100 cubes |

150x300 cylinders |

100x100x500 |

0.9-0.96 |

|

0.075-2 |

30 |

2396.33 |

0.51 |

33.21 |

26.57 |

4.25 |

|

7.33 |

|

233 |

| |

|

|

100 cubes |

150x300 cylinders |

100x100x500 |

0.9-0.96 |

|

0.075-2 |

40 |

2343.31 |

0.51 |

31.15 |

24.92 |

4.17 |

|

6.77 |

|

299 |

| Wei |

2022 |

Harihanandh and Karthik [34] |

150 cubes |

|

100x100x500 |

|

|

|

0 |

|

0.45 |

37.8 |

30.24 |

4.27 |

|

3.75 |

|

120 |

| |

|

|

150 cubes |

|

100x100x500 |

|

|

1-2 |

5 |

|

0.45 |

39.99 |

31.99 |

4.46 |

|

3.94 |

|

110 |

| |

|

|

150 cubes |

|

100x100x500 |

|

|

1-2 |

10 |

|

0.45 |

38.25 |

30.60 |

4.33 |

|

3.78 |

|

70 |

| |

|

|

150 cubes |

|

100x100x500 |

|

|

1-2 |

15 |

|

0.45 |

24.225 |

19.38 |

3.63 |

|

2.51 |

|

20 |

| |

|

|

150 cubes |

|

100x100x500 |

|

|

1-2 |

20 |

|

0.45 |

19.55 |

15.64 |

2.92 |

|

2.08 |

|

0 |

| |

|

|

150 cubes |

|

100x100x500 |

|

|

1-2 |

25 |

|

0.45 |

14.02 |

11.22 |

2.56 |

|

1.58 |

|

0 |

Table 14.

Derived equations for compressive strength and proposed developed models.

Table 14.

Derived equations for compressive strength and proposed developed models.

| Type of Data |

Type of Curve |

Proposed Model |

Data Point |

R2

|

MABE |

MAPE |

| Experimental Data of This Study |

Exponential |

|

3 |

0.999 |

0.045 |

0.194 |

| Linear |

|

3 |

0.997 |

0.097 |

0.423 |

| Volume Substitution Data |

Exponential |

|

110 |

0.805 |

3.314 |

13.396 |

| Linear |

|

110 |

0.802 |

3.318 |

13.519 |

| Weight Substitution Data |

Exponential |

|

50 |

0.682 |

5.277 |

32.116 |

| Linear |

|

50 |

0.619 |

5.274 |

35.261 |

| All Data |

Exponential |

|

160 |

0.741 |

4.795 |

22.352 |

| Linear |

|

160 |

0.733 |

4.728 |

22.814 |

Table 15.

Suggested models and performances for compressive strength.

Table 15.

Suggested models and performances for compressive strength.

| Year |

Reference |

Data Point |

R2

|

MABE |

MAPE |

| 2013 |

Nibudey et al. [42]* |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

160 |

0.310 |

12.850 |

64.509 |

| 2013 |

Saikia and De Brito [14] |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

95 |

0.256 |

11.515 |

47.258 |

| 2017 |

Mohammed [18] |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

160 |

0.716 |

5.762 |

24.549 |

| |

|

95 |

0.613 |

5.509 |

24.018 |

| 2021 |

Bamigboye et al. [31] |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

160 |

0.257 |

13.785 |

41.693 |

| 2022 |

Bamigboye et al. [43]** |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

160 |

0.257 |

15.724 |

46.976 |

| |

|

160 |

0.326 |

15.359 |

46.312 |

| 2022 |

Meena and Ramana [44] |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

95 |

0.612 |

5.558 |

16.651 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| 2023 |

Aocharoen and Chotickai [45]** |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

160 |

0.269 |

24.541 |

108.874 |

| This Year |

Sancak and Ozyurt (This Study) |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

160 |

0.741 |

4.795 |

22.352 |

| |

|

160 |

0.733 |

4.728 |

22.814 |

Table 16.

Derived equations and proposed developed models for the connection between tensile strength and PET substitution percentage.

Table 16.

Derived equations and proposed developed models for the connection between tensile strength and PET substitution percentage.

| Type of Data |

Type of Curve |

Proposed Model |

Data Point |

R2

|

MABE |

MAPE |

| Experimental Data of This Study |

Exponential |

|

3 |

0.994 |

0.007 |

0.312 |

| Linear |

|

3 |

0.992 |

0.010 |

0.447 |

| Volume Substitution Data |

Exponential |

|

69 |

0.776 |

0.222 |

9.968 |

| Linear |

|

69 |

0.765 |

0.239 |

10.771 |

| Weight Substitution Data |

Exponential |

|

40 |

0.840 |

0.407 |

20.755 |

| Linear |

|

40 |

0.812 |

0.396 |

21.893 |

| All Data |

Exponential |

|

109 |

0.823 |

0.290 |

14.275 |

| Linear |

|

109 |

0.811 |

0.296 |

14.901 |

Table 17.

Suggested models and their performances for the connection between tensile strength and PET substitution percentage.

Table 17.

Suggested models and their performances for the connection between tensile strength and PET substitution percentage.

| Year |

Reference |

Data Point |

R2

|

MABE |

MAPE |

| 2013 |

Nibudey et al. [42]* |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

109 |

0.293 |

1.092 |

52.831 |

| 2021 |

Bamigboye et al. [31] |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

109 |

0.255 |

0.842 |

28.760 |

| 2022 |

Bamigboye et al. [43]** |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

109 |

0.255 |

1.084 |

36.799 |

| |

|

109 |

0.301 |

1.051 |

35.657 |

| 2022 |

Meena and Ramana [44] |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

52 |

0.809 |

0.568 |

17.698 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| This Year |

Sancak and Ozyurt (This Study) |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

109 |

0.823 |

0.290 |

14.275 |

| |

|

109 |

0.811 |

0.296 |

14.901 |

Table 18.

Derived equations and proposed developed models for the connection between tensile strength and compressive strength.

Table 18.

Derived equations and proposed developed models for the connection between tensile strength and compressive strength.

| Type of Data |

Type of Curve |

Proposed Model |

Data Point |

R2

|

MABE |

MAPE |

| Experimental Data of This Study |

Power |

|

3 |

0.998 |

0.004 |

0.162 |

| Linear |

|

3 |

0.998 |

0.003 |

0.138 |

| Volume Substitution Data |

Power |

|

69 |

0.665 |

0.303 |

12.327 |

| Linear |

|

69 |

0.672 |

0.295 |

12.120 |

| Weight Substitution Data |

Power |

|

40 |

0.463 |

0.704 |

21.796 |

| Linear |

|

40 |

0.317 |

1.559 |

60.953 |

| All Data |

Power |

|

109 |

0.540 |

0.441 |

15.297 |

| Linear |

|

109 |

0.545 |

0.444 |

16.333 |

Table 19.

Suggested models and their performances for the connection between tensile strength and compressive strength.

Table 19.

Suggested models and their performances for the connection between tensile strength and compressive strength.

| Year |

Reference |

Data Point |

R2

|

MABE |

MAPE |

| 2013 |

Nibudey et al. [42]* |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

109 |

0.535 |

0.839 |

32.306 |

| 2013 |

Juki et al. [16] |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

109 |

0.522 |

0.670 |

27.486 |

| 2013 |

Saikia and De Brito [14] |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

109 |

0.535 |

0.665 |

23.161 |

| 2017 |

Mohammed [46] |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

109 |

0.535 |

0.471 |

17.639 |

| |

|

109 |

0.532 |

0.458 |

16.554 |

| 2020 |

Almeshal et al. [30] |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

109 |

0.532 |

0.446 |

16.472 |

| 2021 |

Tayeh [33] |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

109 |

0.038 |

5.678 |

326.375 |

| 2021 |

Bamigboye et al. [31] |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

109 |

0.535 |

0.478 |

16.737 |

| 2022 |

Bamigboye et al. [43]** |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

109 |

0.535 |

0.488 |

16.892 |

| This Year |

Sancak and Ozyurt (This Study) |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

109 |

0.540 |

0.441 |

15.297 |

| |

|

109 |

0.545 |

0.444 |

16.333 |

Table 20.

Derived equations and proposed developed models for the connection between flexural strength and PET substitution percentage.

Table 20.

Derived equations and proposed developed models for the connection between flexural strength and PET substitution percentage.

| Type of Data |

Type of Curve |

Proposed Model |

Data Point |

R2

|

MABE |

MAPE |

| Experimental Data of This Study |

Exponential |

|

3 |

0.996 |

0.010 |

0.321 |

| Linear |

|

3 |

0.994 |

0.013 |

0.430 |

| Volume Substitution Data |

Exponential |

|

39 |

0.656 |

0.451 |

13.933 |

| Linear |

|

39 |

0.650 |

0.457 |

14.289 |

| Weight Substitution Data |

Exponential |

|

32 |

0.607 |

1.058 |

27.280 |

| Linear |

|

32 |

0.578 |

0.936 |

27.362 |

| All Data |

Exponential |

|

71 |

0.607 |

0.700 |

20.542 |

| Linear |

|

71 |

0.593 |

0.670 |

20.980 |

Table 21.

Derived equations and proposed developed models for the connection between flexural strength and compressive strength.

Table 21.

Derived equations and proposed developed models for the connection between flexural strength and compressive strength.

| Type of Data |

Type of Curve |

Proposed Model |

Data Point |

R2

|

MABE |

MAPE |

| Experimental Data of This Study |

Power |

|

3 |

0.999 |

0.003 |

0.099 |

| Linear |

|

3 |

0.999 |

0.002 |

0.064 |

| Volume Substitution Data |

Power |

|

39 |

0.660 |

0.500 |

13.507 |

| Linear |

|

39 |

0.671 |

0.484 |

13.195 |

| Weight Substitution Data |

Power |

|

32 |

0.411 |

0.958 |

20.972 |

| Linear |

|

32 |

0.376 |

1.025 |

24.735 |

| All Data |

Power |

|

71 |

0.480 |

0.711 |

16.913 |

| Linear |

|

71 |

0.465 |

0.724 |

17.889 |

Table 22.

Suggested models and their performances for the connection between flexural strength and compressive strength.

Table 22.

Suggested models and their performances for the connection between flexural strength and compressive strength.

| Year |

Reference |

Data Point |

R2

|

MABE |

MAPE |

| 2013 |

Juki et al. [16] |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

71 |

0.471 |

0.769 |

18.906 |

| 2013 |

Saikia and De Brito [14] |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

71 |

0.457 |

1.131 |

23.352 |

| 2017 |

Mohammed [46] |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

71 |

0.457 |

0.714 |

16.832 |

| |

|

71 |

0.468 |

0.736 |

17.165 |

| 2020 |

Almeshal et al. [30] |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

71 |

0.468 |

2.334 |

59.287 |

| 2021 |

Tayeh [33] |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

71 |

0.280 |

2.716 |

89.538 |

| 2022 |

Alqahtani [47]* |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

71 |

0.473 |

0.762 |

16.857 |

| |

|

71 |

0.429 |

1.134 |

26.352 |

| This Year |

Sancak and Ozyurt (This Study) |

|

|

|

|

| |

|

71 |

0.480 |

0.711 |

16.913 |

| |

|

71 |

0.465 |

0.724 |

17.889 |

Table 23.

Derived equations and proposed developed models for the connection between modulus of elasticity and PET substitution percentage.

Table 23.