1. Introduction

Ultra low adhesion surfaces have strong hydrophobicity and functions such as self-cleaning, [

1,

2] anti-fouling, [

3,

4] antibacterial, [

5,

6] deicing [

7,

8] and microfluidics [

9,

10,

11], making them of great research interest in recent years [

12]. In pursuit of hydrophobic surfaces, numerous scholars have embarked on extensive research endeavors, [

13] focusing on material composition [

14] and microstructural design [

15]. Drawing inspiration from biomimetics, they have been influenced by biological prototypes such as the lotus leaf [

16] and the water strider [

17]. This has led to a plethora of investigative studies, for instance Li et al. reported a reversible wettability transition between superhydrophilicity and superhydrophobicity through alternate heating-reheating cycle on laser ablated brass surface [

18]. Pan et al. report a bottom-up approach to prepare super-repellent coatings using a mixture of fluorosilanes and cyanoacrylate to achieve ultralow surface tension liquids [

19]. Although these surfaces with ultra-low adhesion can harness liquid manipulation, challenges such as expediently fabricating the desired microstructured surfaces and the precise regulation of surface topography still remain.

The current state of research in laser direct writing technology has witnessed significant advancements, with a particular focus on its application in precision fabrication, [

20] micro-nanostructuring, [

21] and optoelectronic device manufacturing [

22]. This technique has gained considerable traction due to its ability to achieve high-resolution patterning with exceptional spatial control [

23]. Researchers have successfully employed laser direct writing for the creation of complex microfluidic devices, [

24] photonic crystals, [

25] and biosensors, [

26,

27] among other applications [

28]. Moreover, ongoing investigations are aimed at optimizing the process parameters to enhance the writing speed, precision, and functionality of the fabricated structures [

1,

29,

30]. Techniques such as femtosecond laser writing and two-photon polymerization are being explored to further push the boundaries of what is achievable with laser direct writing, thereby broadening its utility in various scientific and industrial domains [

31].

Herein, via laser direct writing process we present an ultra-low adhesion and flexible surface inspired by mushroom where micro/nano conical array located. This novel surface features an array of biomimetic micro-cones, a microstructure that is achieved through a laser direct writing technique, enabling programmable control of the microstructure formation. Subsequent surface fluorination modification has endued the surface with exceptional superhydrophobic properties, facilitating ultra-low adhesion effects for liquids such as milk, coffee, and deionized water. Moreover, this surface demonstrates the phenomenon of ultra-low liquid adhesion flow on curved surfaces. In the event of surface scratches, the ultra-low adhesion property is still maintained, indicative of robust performance. We believe that this surface design methodology presented herein may serve as an inspiration for biomimetic designs in food, medical, and self-cleaning applications.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS, Dow Corning, Midland, MI, USA) was used as received. 1H,1H,2H,2H-perfluorodecyltriethoxysilane (PFDTES) was purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Bio-Chem Technology Co., Ltd, China. CuSO4 (Copper sulphate), H2SO4 (Sulfuric acid) and HCl (Hydrochloric acid) were supplied by Beijing Chemical Works (Beijing, China). The experimental apparatus utilized in this study comprises a nanosecond lasermarking machine (Beijing Leijieming Laser Technology Development Company Limited. (Beijing, China)), a microscope, a Canon 90D camera (Canon Inc., Ota City, Japan), a highspeed camera (Hefei Zhongke Junda Vision Technology Co., Ltd. (Hefei, China)), a Plasma ion cleaner (PlasmaTechnology GmbH, Herrenberg, Germany), a magnetron sputtering apparatus, a precision electronic balance (with a precision of 0.001 g). The experimental materials, including fresh mushrooms, milk, coffee, and ketchup, have been sourced from the Beiguo supermarket (Shijiazhuang, China).

2.2. Morphological Characterization

Based on the study of the wetting principle of objects, this paper proposes the fabrication of biomimetic hydrophobic functional surfaces on PDMS with low surface free energy. PDMS itself is a hydrophobic surface with a contact angle greater than 90 °. According to theoretical analysis, increasing the surface roughness of PDMS can enhance its hydrophobic properties. The method for producing a biomimetic surface of mushroom microstructure introduced in this article is as follows: take 40 mL of PDMS main agent into a beaker, add 4 mL of curing agent (volume ratio of main agent to curing agent is 10:1) dropwise, and stir magnetically for 10 minutes to prepare the PDMS solution ready to use. Cut the surface of the mushroom and place them on a clean glass slide. Slowly pour the PDMS solution onto the surface and place it in a vacuum container to remove bubbles. Then, place it in an oven and cure at 75 ℃ for 40 minutes. Finally, separate the cured PDMS film from the substrate to obtain a PDMS film with a reverse surface structure of mushroom. Using PDMS membrane as a template, perform 2 replicates, and the experimental process is the same as 1. After peeling off the PDMS membrane, a biomimetic surface of mushroom microstructure can be obtained. The microstructure of the mushroom samples and the surface morphology of the prepared samples were studied using high-resolution field emission scanning electron microscopy (SEM: ZEISS Merlin, Carl Zeiss SMT AG, Germany). The 3D morphology of the prepared samples was observed and the contour curves were measured using a super depth-of-field microscope (VH-ZST, Keyence, China). The elements on the surface of the prepared samples were analyzed using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS: Thermo escalab 250XI, USA). The elemental composition of the surface of the prepared samples was qualitatively and quantitatively analyzed using energy dispersive spectroscopy (EDS: SU8020, Hitachi High Technologies, Japan). The contact angle and droplet manipulation were recorded using a high-speed camera (AE120M, HF AGILE DEVICE CO., LTD., China).

2.3. Surface Manufacturing Process of Mushroom Microstructure

Laser direct writing processing uses a laser system with a central wavelength of 1060 nm (RFL-P30Q, provided by Wuxi Ruiyu Fiber Laser Technology Co., Ltd., China). The 100 ns laser was focused onto the electrode surface through a YAG lens (focal length 70 mm, provided by Wavelength Optoelectronics Co., Ltd.). The output power was 50 W and the spot diameter was ≈40 μm. First, the copper plate was ultrasonically cleaned and acid pickling to remove oil and oxides on the surface, and then laser ablation was performed. By adjusting the scanning path spacing of the laser and the spot spacing on the scanning path, the microconical array structure could be quickly prepared (

Figure 1e). The scanning path spacing was set to 40-60 μm, and the spot spacing was the product of the scanning speed and the reciprocal of the scanning frequency. The frequency was set to 50 kHz and the scanning speed was set to 2500 mm/s.

2.4. Wetting Ability

Compare the PDMS template on the microstructure surface of mushroom and four types of droplets (deionized water, milk, coffee, and ketchup) with a volume of 5 μL dropped on the as-prepared surface. Measure the contact angle of different samples using an optical contact angle measuring instrument. 5 μL of deionized water were sequentially dispensed from heights of 3 mm, 5 mm, 7 mm, and 10 mm onto a surface characterized by a slope angle of 15 degrees. The surface exhibited a micro-conical array with an inter-spacing of 40 μm. The impact points, rebound dynamics, and transient morphologies of the droplets upon striking and settling were meticulously recorded.

2.5. Optical Characteristics

Measure the total transmittance of the sample between 400 and 1200nm wavelengths using a spectrophotometer (PerkinElmer, Lambda 1050) equipped with a 150mm integrating sphere. Remove the integrating sphere and measure the direct transmittance of the sample. The scattering angle distribution was measured using a Cary 7000 Universal Measurement Spectrophotometer (UMS). In this instrument, the incident light is directed vertically towards the sample surface as a 5mm × 5mm square beam, and the photodetector scans from 10 to 350 (-10) degrees. The wavelength testing range is 530 to 570 nanometers.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Fabrication of Mushroom-Like Micro/Nano-Structured Surface

3.1.1. Fabrication Process

Mushrooms are a common culinary ingredient, frequently encountered in daily life, and their surfaces often exhibit a contamination-resistant characteristic, as illustrated in

Figure 1a. Upon the application of a fine dust layer to the mushroom’s surface followed by rinsing with deionized water, it was observed that the dust particles were effectively removed by the water flow, as depicted in

Figure 1b. This observation indicates that the mushroom surface possesses self-cleaning and anti-adhesive properties. Then the surface topography of the mushroom was characterized using a white light interferometer (WLI). It was observed that the surface is adorned with micro-protrusions (

Figure 1c). Under environmental scanning microscope and electron scanning microscope, it was found that the protrusions had irregular shapes, but most of them were about 10 μm long, 10 μm wide, and 15 μm high, as shown in

Figure 1d. Hence, based on the hydrophobicity research findings of enoki, [

32] it can be concluded that the self-cleaning properties of mushrooms are attributed to the protrusions array present on their surface.

To replicate this structure, laser direct writing process is used to melt and solidify the material layer by layer using a laser beam, thereby establishing a three-dimensional model. Through the manipulation of laser beam shaping, synchronization of the laser frequency with the scanning velocity can be achieved, thereby enabling programmable control over the parameters of microstructures (

Figure 1e). Laser engraving is performed on copper sheets to create the desired microstructure as shown in

Figure 1f, which is a model of the surface microstructure of mushrooms. Different distances between protruding structures can lead to different adhesion, so three types of copper sheets with different distances were processed to mimic the microstructure of mushrooms, namely 40 μm, 50 μm, and 60 μm (

Figure 1g). The parameters of laser scanning are displayed in

Table 1.

3.1.2. Surface Modification

The biomimetic hydrophobic surface proposed in this article selects polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) as the structural material. Compared with previous rigid materials such as metals, [

33] PDMS has good flexibility and can bend freely [

34]. This feature makes PDMS based biomimetic hydrophobic surfaces applicable to irregularly shaped devices. These characteristics of PDMS expand the application range of biomimetic hydrophobic surfaces [

35]. In addition, PDMS has stable chemical properties and is not easily changed once a hydrophobic surface is formed. It is also inexpensive and easy to obtain. Therefore, using PDMS as a structural material for biomimetic hydrophobic anti-adhesion surfaces has high research value and practical significance. The structure is replicated by casting PDMS onto a copper substrate with microstructure. The negative mold of the desired structure is obtained through a single replication, followed by a second replication to obtain the desired microstructure (

Figure 2).

Afterwards, SEM was used to observe the obtained structure, which met the requirements.

Figure 3 presents scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of biomimetic mushroom-like microstructures fabricated on a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) substrate. Specifically,

Figure 3a depicts a micro-cone array with a spacing of 40 μm,

Figure 3b depicts a micro-cone array with a spacing of 50 μm, and

Figure 3c depicts a micro-cone array with a spacing of 60 μm. The SEM images reveal that the laser direct writing technique yields regularly shaped and intact array surfaces, enabling the controlled preparation of low surface energy materials with biomimetic mushroom-like micro/nanostructures. Subsequently, the fluorination process transforms the microstructures with low surface energy into those with high surface energy. In this process, PFDTES serves as the fluorating agent due to its superior capability in constructing high surface energy structures [

36].

Figure 4 illustrates that the fluorine (F) content in the PDMS substrate of the biomimetic mushroom-like surface increased from 6.83% (

Figure 4a) before the fluorination process to 32% (

Figure 4b) after fluorination. This significant alteration in the elemental composition of the surface indicates a pronounced change in the material properties before and after fluorination, signifying the successful grafting of the fluorination process.

3.2. Self-Cleaning Ability

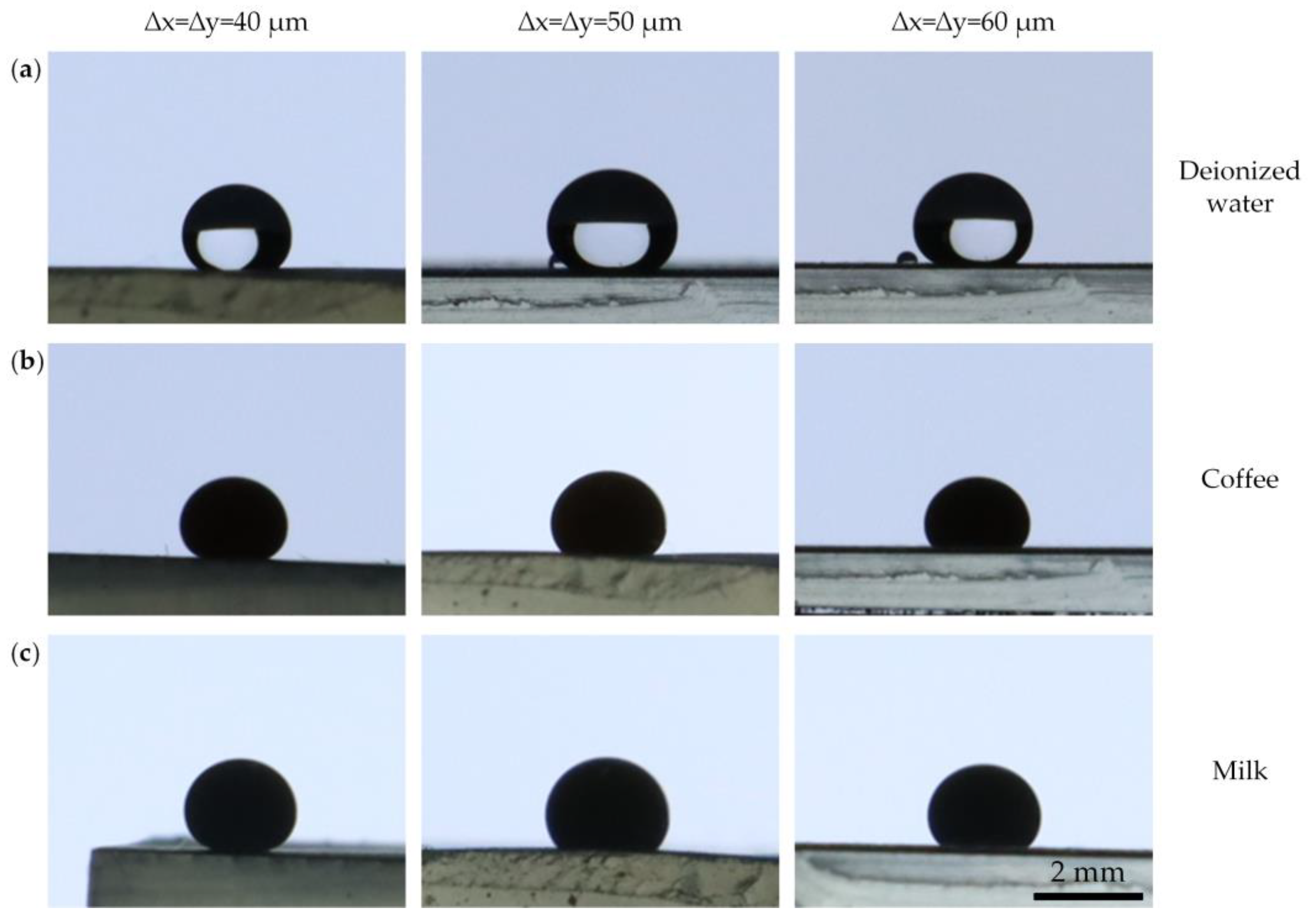

Subsequent to the fabrication of PDMS substrates, surface performance tests were conducted. The adhesion properties were evaluated by depositing droplets of water, coffee, and milk onto the micro-cone arrays with spacing of 40 μm, 50 μm, and 60 μm, respectively. Typically, on common surfaces, liquids such as water, coffee, and milk tend to penetrate and leave marks and stains on ordinary surfaces. However, on the surfaces with superhydrophobic microstructures, these liquids exhibit higher contact angles, indicative of the surfaces’ self-cleaning efficacy akin to a lotus leaf. As the statistical values presented by

Table 2, the biomimetic mushroom-like surface with a micro-cone array spacing of 40 μm demonstrates the relatively highest contact angles which is 132.3° of deionized water, 135.3° of coffee and 144.1° of milk. This indicates that the spacing of the micro-cone arrays influences the ultra-low adhesion properties, with smaller spacings conferring superior hydrophobicity and, consequently, enhanced self-cleaning capabilities.

Water droplets have good rebound properties on PDMS, and this property does not change when falling from different heights, making the material have better self-cleaning effect.

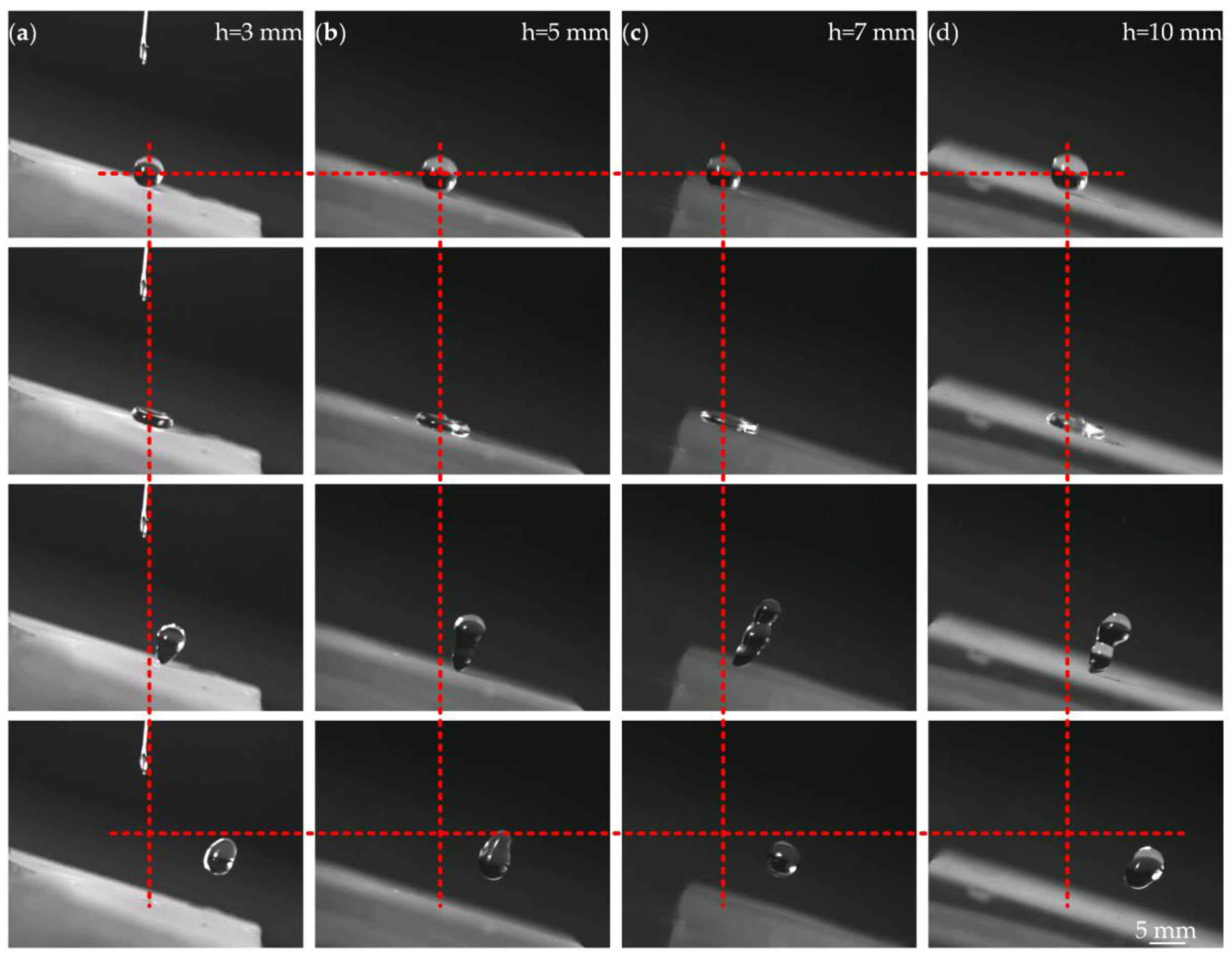

Figure 6 illustrates the impact dynamics of 5 μL deionized water droplets onto a biomimetic surface, which is characterized by a micro-conical array resembling mushroom-shaped structures with a spacing of 40 μm, from varying heights of 3 mm, 5 mm, 7 mm, and 10 mm on a 15° slope. The results demonstrate that upon impact, the droplets consistently exhibit bouncing behavior across all tested heights, signifying the exceptional anti-adhesion properties of the fabricated biomimetic superhydrophobic surface.

The data presented in

Table 3, which details the rebound heights and offset displacement of the droplets, reveals that at a height of 5 mm, the droplets achieve the maximum rebound height coupled with the minimum lateral displacement (

Figure 6b). In contrast, at a height of 10 mm, the droplets exhibit the lowest rebound height and the greatest lateral displacement (

Figure 6d). This phenomenon can be attributed to the increased kinetic energy of the droplets at this height, which enables them to penetrate the microstructured voids, thereby impeding rebound. Additionally, due to the inclined plane, the horizontal component of the impact force becomes predominant, contributing to the increased lateral displacement.

The microstructure surface is not only suitable for self-cleaning of tiny liquid stains, but also for some larger volume of liquid droplets or soft solid stains, such as ketchup. In

Figure 7a, three types of liquid with diameter of about 5 mm can stay stationary on the bionic surface as sphere morphology. Employing a syringe with a 1 mm diameter, a sequence of injections was performed using deionized water, coffee, and milk onto the biomimetic mushroom-like surface to assess its dynamic superhydrophobic attributes. As depicted in

Figure 7b, the biomimetic surface demonstrated consistent and robust dynamic ultra-low adhesion characteristics with all three types of liquids. We placed 5 g of ketchup on two different surfaces and observed and tested their antifouling performance. Ketchup adheres to regular PDMS and is difficult to clean after a period of time. While on PDMS surfaces with mushroom-like microstructures, there will be no adhesion and can be directly cleaned after a period of time (

Figure 7c). Furthermore, when the ultra-low adhesion surface was subjected to repeated contact with 5 g ketchup for five times, the results revealed that the surface exhibited exceptional anti-adhesion properties. In contrast, the conventional PDMS surface displayed an obvious adhesion (

Figure 7d). Therefore, PDMS surfaces with microstructures also have good antifouling properties against soft solid and semi-solid stains.

3.3. Flexible and Robust Performance

Achieving controllable of macroscale liquid dynamics overflow also a significant area for surface design and fabrication [

37]. When the as-prepared surface curved, liquid can overflow in accordance with the solid surface (

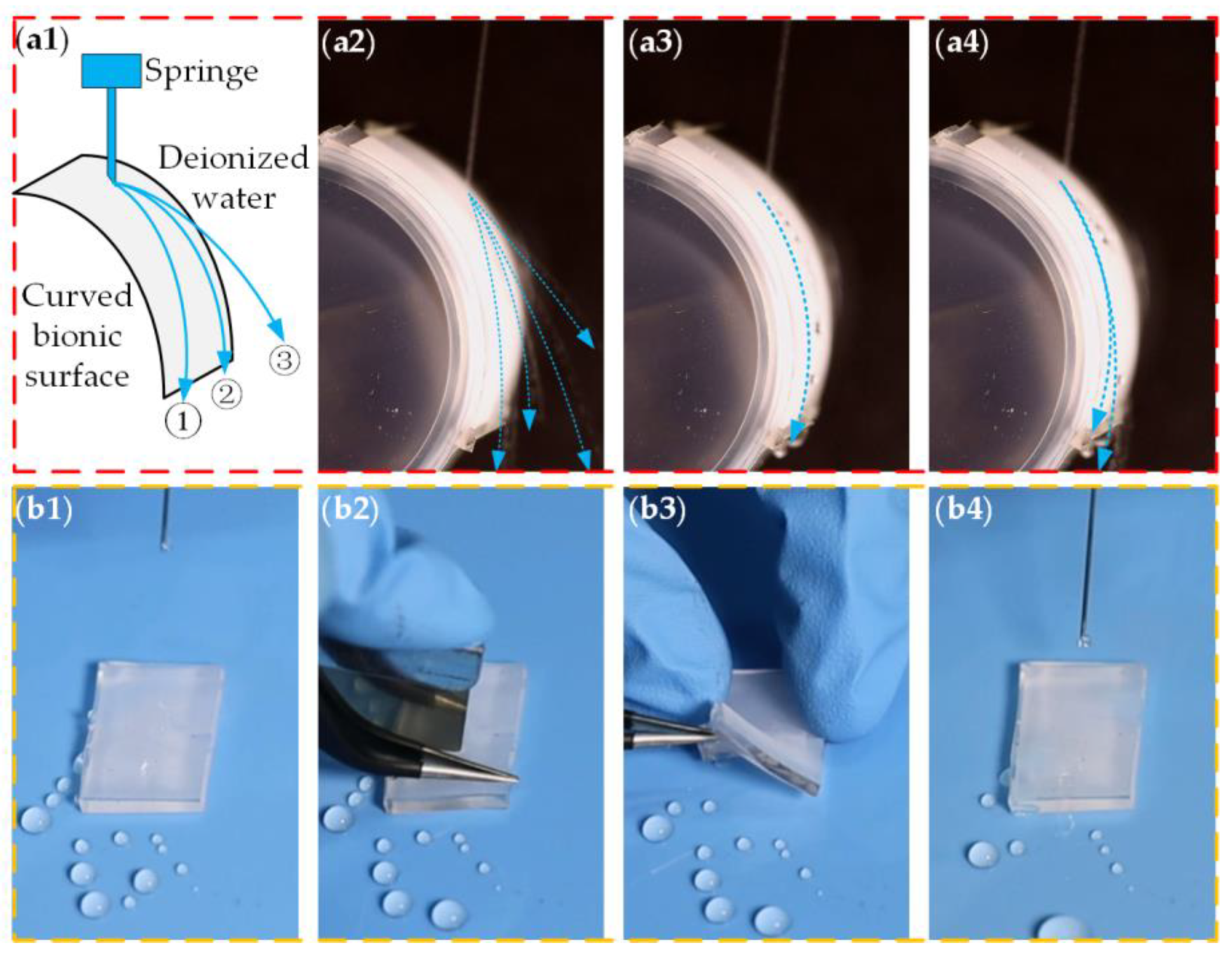

Figure 8a). As illustrated in

Figure 8, deionized water was ejected onto the curved low-adhesion surface using a syringe. At high flow rates (

Figure 8a2), the water stream was observed to split along three distinct paths (labeled as paths ①, ② and ③). Conversely, at lower flow rates, the water flowed along the curved surface (

Figure 8a3). As the flow rate was further reduced, the water transformed into a continuous series of droplets (

Figure 8a4), which also exhibited the ability to slide along the curved surface. This behavior demonstrates that the biomimetic surface is capable of achieving flexible ultra-low adhesion properties.

Moreover, due to the excellent flexibility and self-healing properties of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), the biomimetic ultra-low adhesion surface obtained by flexible template replication technology has good self-healing performance. As depicted in

Figure 8b1, the biomimetic surface exhibits ultra-low adhesion characteristics. Upon incising the surface with a blade and subsequently reinjecting a liquid stream onto it,

Figure 8b4 clearly illustrates that the surface maintains its ultra-low adhesion properties. This demonstrates that the biomimetic ultra-low adhesion surface fabricated by this process possesses exceptional robustness.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, this paper proposed a programmable fabrication of biomimetic mushroom-like surface microstructures on a copper substrate was achieved via ultrafast laser direct writing technology. Subsequent to a biomimetic replication process, a biomimetic flexible surface based on polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) was obtained. Through surface fluorination treatment, a flexible biomimetic surface with ultra-low adhesion properties was developed, capable of long-lasting non-adhesive functionality against a variety of liquids including deionized water, milk, and coffee. Experimental results indicate that the surface also possesses high robustness. We anticipate that this work offers a biomimetic design approach for the construction of ultra-low adhesion surfaces with micro-nano structures.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.L. and L.Z.; methodology, T.H., S.H.; software, S.R.; validation, S.D., Q.Z. and Y.Y.; formal analysis, S.S.; investigation, J.Y.; resources, T.H.; data curation, T.H., J.Y.; writing—original draft preparation, T.H., G.L.; writing—review and editing, G.L., L.Z.; visualization, S.R.; supervision, G.L.; project administration, G.L.; funding acquisition, G.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number 52205306), Hebei Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. E2022208039), Science and Technology Project of Hebei Education Department (Grant No. BJK2023028), Central Guidance on Local Science and Technology Development Fund of Hebei Province (Grant No. 236Z1802G), Postgraduate’s Innovation Fund Project of Hebei Province (Grant No. CXZZSS2024076), Hebei Provincial Additive Manufacturing Industrial Technology Research Institute.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend gratitude to HF AGILE DEVICE CO., LTD. for their assistance in filming the movies.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yang, J.; Liu, G.; Zhang, K.; Li, P.; Yan, H.; Yan, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, L.; Liu, X.; et al. Sunflower-Inspired Superhydrophobic Surface with Composite Structured Microcone Array for Anisotropy Liquid/Ice Manipulation. Small 2024, e2403420. [CrossRef]

- K. S. Liu and L. Jiang. Bio-Inspired Self-Cleaning Surfaces. Annual Review of Materials Research 2012, 42, 231-263. [CrossRef]

- Jokinen, V.; Kankuri, E.; Hoshian, S.; Franssila, S.; Ras, R.H.A. Superhydrophobic Blood-Repellent Surfaces. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, e1705104. [CrossRef]

- Ware, C.S.; Smith-Palmer, T.; Peppou-Chapman, S.; Scarratt, L.R.J.; Humphries, E.M.; Balzer, D.; Neto, C. Marine Antifouling Behavior of Lubricant-Infused Nanowrinkled Polymeric Surfaces. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 4173–4182. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.-J.; Ruan, J.-J.; Zhang, H.-M.; Shi, Y.; Wang, F.; Li, B.-J. Superhydrophobicity induced antibacterial adhesion and durability of laser bidirectionally-textured zirconia surfaces with different inclination angles. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 41. [CrossRef]

- Ieamviteevanich, P.; Onklam, P.; Kampechdee, W.; Churiwan, A.; Vittayakorn, N.; Prachayawarakorn, J.; Seeharaj, P. Asymmetric dot-patterned wettable and antibacterial wound dressings from bacterial cellulose–alginate composites coated with stearic acid-modified ZnO/chitosan/AgNPs. Cellulose 2024, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Chen, H.; Liu, X.; Liu, H.; Zhang, D. Development of high-efficient synthetic electric heating coating for anti-icing/de-icing. Surf. Coatings Technol. 2018, 349, 340–346. [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.; Chen, Z.; Tiwari, M.K. All-organic superhydrophobic coatings with mechanochemical robustness and liquid impalement resistance. Nat. Mater. 2018, 17, 355–360. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, W.; Zhou, Y.; Tang, S.; Wang, S.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, P. Ultrafast bounce of particle-laden droplets. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zheng, H.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, C.; Song, Y.; Deng, X.; Leung, M.; Yang, Z.; Xu, R.X.; et al. A droplet-based electricity generator with high instantaneous power density. Nature 2020, 578, 392–396. [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Sun, Q.; Hokkanen, M.J.; Zhang, C.; Lin, F.-Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhu, S.-P.; Zhou, T.; Chang, Q.; He, B.; et al. Design of robust superhydrophobic surfaces. Nature 2020, 582, 55–59. [CrossRef]

- T. Yongtu, Z. Yang, L. Hongjie, et al. Directional Removal of Water Droplets by Magnetic Responsive Polydimethylsiloxane Arrays. Chem. J. Chinese Universities 2024, 45, 20240220.

- P. G. de Gennes. Wetting: statics and dynamics. Reviews of Modern Physics 1985, 57, 827-863. [CrossRef]

- S. G. Yoon, Y. Yang, H. Jin, et al. A Surface-Functionalized Ionovoltaic Device for Probing Ion-Specific Adsorption at the Solid-Liquid Interface. Advanced Materials 2019, 31, e1806268. [CrossRef]

- Villegas, M.; Zhang, Y.; Abu Jarad, N.; Soleymani, L.; Didar, T.F. Liquid-Infused Surfaces: A Review of Theory, Design, and Applications. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 8517–8536. [CrossRef]

- Barthlott, W.; Neinhuis, C. Purity of the sacred lotus, or escape from contamination in biological surfaces. Planta 1997, 202, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- X. Gao and L. Jiang. Biophysics: water-repellent legs of water striders. Nature 2004, 432, 36. [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jiang, Y.; Jiang, Z.; Li, Y.; Wen, C.; Lian, J. Reversible wettability transition between superhydrophilicity and superhydrophobicity through alternate heating-reheating cycle on laser-ablated brass surface. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 492, 349–361. [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Guo, R.; Björnmalm, M.; Richardson, J.J.; Li, L.; Peng, C.; Bertleff-Zieschang, N.; Xu, W.; Jiang, J.; Caruso, F. Coatings super-repellent to ultralow surface tension liquids. Nat. Mater. 2018, 17, 1040–1047. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Hou, Z.; Lin, L.; Li, Z.; Sun, H. 3D Laser Nanoprinting of Functional Materials. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2023, 33. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Z.; Wu, J.-R.; Wu, Z.-P.; Wu, T.-N.; He, Y.-C.; Yin, K. Femtosecond laser micro/nano fabrication for bioinspired superhydrophobic or underwater superoleophobic surfaces. J. Central South Univ. 2021, 28, 3882–3906. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Sun, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, W.; Chen, X.; Wong, C.-P. Laser Processing of Flexible In-Plane Micro-supercapacitors: Progresses in Advanced Manufacturing of Nanostructured Electrodes. ACS Nano 2022, 16, 10088–10129. [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yang, L.; Ren, X.; Yang, Y.; Cheng, G. Femtosecond laser-induced non-centrosymmetric surface microstructures on bulk metallic glass for unidirectional droplet micro-displacement. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 2019, 53, 105305. [CrossRef]

- K. Yin, L. Wang, Q. Deng, et al. Femtosecond Laser Thermal Accumulation-Triggered Micro-/Nanostructures with Patternable and Controllable Wettability Towards Liquid Manipulating. Nanomicro Lett 2022, 14, 97. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhou, Z.; Li, B.; Wang, C.; Liu, Q. Progresses on new generation laser direct writing technique. Mater. Today Nano 2021, 16. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.; Wooh, S.; Cho, J.; Dickey, M.D.; So, J.-H.; Koo, H.-J. Imbibition-induced selective wetting of liquid metal. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Samanta, A.; Huang, W.; Bell, M.; Shaw, S.K.; Charipar, N.; Ding, H. Large-area surface wettability patterning of metal alloys via a maskless laser-assisted functionalization method. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 568, 150788. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Yin, K.; Xiao, S.; Wu, Z.; Zhu, Z.; Duan, J.; He, J. Laser Fabrication of Bioinspired Gradient Surfaces for Wettability Applications. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 8. [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Yang, J.; Zhang, K.; Yan, H.; Yan, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, L.; Yang, G.; et al. Nepenthes alata inspired anti-sticking surface via nanosecond laser fabrication. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 483. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Huo, S.; Duan, S.; Han, T.; Liu, G.; Zhang, K.; Chen, D.; Yang, G.; Chen, H. Laser Direct Writing of Setaria Virids-Inspired Hierarchical Surface with TiO2 Coating for Anti-Sticking of Soft Tissue. Micromachines 2024, 15, 1155. [CrossRef]

- Yong, J.; Yang, Q.; Hou, X.; Chen, F. Nature-Inspired Superwettability Achieved by Femtosecond Lasers. Ultrafast Sci. 2022, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Haghanifar, S.; Tomasovic, L.M.; Galante, A.J.; Pekker, D.; Leu, P.W. Stain-resistant, superomniphobic flexible optical plastics based on nano-enoki mushroom-like structures. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 15698–15706. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Liu, G.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, S.; Yang, C.; Yang, J.; Zhang, L.; Chen, H. Liquid-Infused bionic microstructures on High-Frequency electrodes for enhanced spark effects and reduced tissue adhesion. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 485. [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Guan, Q.; Li, M.; Saiz, E.; Hou, X. Nature-inspired strategies for the synthesis of hydrogel actuators and their applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2023, 140. [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, L.; Liu, H.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, D.; Han, Z.; Jiang, L. Continuous directional water transport on the peristome surface of Nepenthes alata. Nature 2016, 532, 85–89. [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Zhang, J.; Cao, X.; Huo, J.; Huang, X.; Zhang, J. Durable superhydrophobic coatings for prevention of rain attenuation of 5G/weather radomes. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Jiang, L.; Dong, Z. Overflow Control for Sustainable Development by Superwetting Surface with Biomimetic Structure. Chem. Rev. 2022, 123, 2276–2310. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).