1. Introduction

The problem of stabilization for the mathematical model of the controlled inverted pendulum is very popular among the researchers during many years (see, for instance, [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]). The nonlinear model of the controlled inverted pendulum has the form of nonlinear differential equation of the second order

where

measures the angle between the rod and the upward vertical (

Figure 1). The linearized mathematical model of the controlled inverted pendulum can be described by the linear differential equation of the second order

The classical way of stabilization [

7] for the equation (

1) or (

2) uses the control

, which is a linear combination of the state and velocity of the pendulum, i.e.,

But this type of control, which represents instantaneous feedback, is quite difficult to realize because usually it is necessary to have some finite time to make measurements of the coordinates and velocities, to treat the results of the measurements and to implement them in the control action.

Unlike of the classical way of stabilization another way of stabilization is proposed in [

4,

5,

19]. It is supposed that only the trajectory of the pendulum is observed and the control

does not depend on the velocity, but depends on the previous values of the trajectory

,

, and is given in the form

where the kernel

is a continuous from the right function of bounded variation on

and the integral is understood in the Stieltjes sense. It means, in particular, that both distributed and discrete delays can be used depending on the concrete choice of the kernel

.

In addition, it is supposed that the pendulum is under influence of stochastic perturbations, so, the considered stabilization problem is a problem of the theory of stochastic functional differential equations [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25].

The initial conditions for the system (

1), (

3) or (

2), (

3) are

where

is a given continuously differentiable function.

1.1. Stability Conditions in the Deterministic Case

Substituting (

3) into (

2), putting

,

and using (

4), we obtain the system of linear differential equations with delay

Put

By virtue of the general method of Lyapunov functionals construction in [

19] the following statements have been proven.

Theorem 1.

Let be

Then the zero solution of the system (5) is asymptotically stable.

Remark 1. Note that two first inequalities (7) are necessary conditions for asymptotic stability of the zero solution of the system (5), the third inequality (7) is a sufficient condition only.

Remark 2.

Note that the third inequality (7) can be represented in the form

Remark 3. Note that the inverted pendulum cannot be stabilized by a control that depends on the velocity only, i.e., or on the acceleration only, i.e., .

1.2. Transformation to a System of Differential Equations of Neutral Type

From the first equation of (

5) we have

Putting

from (

10), (

6) and (

9) we obtain

and

Substituting (

11) into the second equation of (

5) and using (

10), let us transform the system (

5) to the form of the system of differential equations of neutral type [

19,

23,

24]

2. Stabilization of the Zero Solution Under Stochastic Perturbations

Linear and nonlinear models of the controlled inverted pendulum under stochastic perturbations of the type of white noise are studied in [

19], where the zero and a stationary nonzero solutions are investigated analytically and via numerical simulations. Here both these mathematical models of the controlled inverted pendulum are considered under a combination of both types of stochastic perturbations: the white noise and Poisson’s jumps.

Let be a complete probability space, be a nondecreasing family of sub--algebras of , i.e., for , be the mathematical expectation with respect to the probability .

Let

and

be respectively

-measurable the Wiener and the Poisson processes,

,

,

[

20,

21,

26,

27],

2.1. Linear Model

Supposing that the parameter

a in the second equation of the system (

5) is under the influence of stochastic perturbations

, we obtain

In this case instead of the system (

12) we obtain the system of stochastic differential equations of the neutral type [

19,

20,

21]

where

is defined in (

10).

Putting

let us represent the system (

14) in the matrix form

Definition 1. The zero solution of the equation (16) is called:

- -

stable in probability if for any and there exists such that the solution of Eq. (16) satisfies the condition for any initial condition ; - -

mean square stable if for each there exists a such that , , provided that ;

- -

asymptotically mean square stable if it is mean square stable and for each initial function .

Lemma 1.

[19] Let the matrix A is defined in (15). The matrix equation

has the positive definite solution with the elements

Theorem 2.

Let be

where , , are defined in (6). Then the zero solution of the equation (16) (and the system (14)) is asymptotically mean square stable.

Proof. Following the general method of Lyapunov functionals construction [

19], consider the functional

, where

,

is defined in (

15), elements of the matrix

P are defined in (

17), the additional functional

will be chosen below.

Let

L be the generator of the equation (

16) [

19,

20,

21,

26,

27]. Then

Note that via (

15) and (

10) we have

From (

17) it follows that

,

,

,

. So,

Note also that via (

15)

and similarly

Using (

6), for arbitrary

we have

and similarly

From (

23), (

24) we obtain

where

As a result from (

19), (

20), (

21), (

22), (

18), (

25) it follows that

Put now

Then via (

6)

From (

27), (

28) and (

26) for the functional

we obtain

From the condition of positivity of the expressions in the brackets before

and

we have

So, if

then there exists

such that the Lyapunov functional

satisfies the condition

It is well known (see [

19,

22,

23,

24,

25,

29]) that the existence of a Lyapunov functional

satisfying the condition (

31) ensures the asymptotic mean square stability of the zero solution of the considered equation.

It remains to show that the inequality (

30) for some

coincides with the inequality (

18) for

. Really, from (

30) it follows that

or via

Note that the function

has a minimum for

and

From this and (

32) the inequality (

18) for

follows. The proof is completed. □

Remark 4. Note that by the last condition (18) coincides with (8).

2.2. Nonlinear Model

Consider now the nonlinear equation (

1) with the control (

3) and similarly to (

5) represent it in the form of the system of nonlinear differential equations

Supposing that the parameter

a in (

33) is influenced by stochastic perturbations

(

13), i.e.,

, we obtain

or

From here and (

11) it follows

where

,

,

and

are defined in (

6), (

10).

Note that the system (

14) is the linear part of the system (

35) and

, i.e., the order of nonlinearity of the system (

35) is higher than one. It is known [

19] that if the order of nonlinearity of the nonlinear system under consideration is higher than one then the sufficient condition for asymptotic mean square stability of the zero solution of the linear part of this system is at the same time the sufficient condition for stability in probability of the zero solution of the initial nonlinear system. Thus, we obtain the following

Theorem 3. If the conditions (18) hold then the zero solution of the system (35) is stable in probability.

3. Nonzero Equilibrium

To get the nonzero equilibrium of the nonlinear system (

33) let us suppose that

,

. Then

and

. From (

33) and (

6) it follows that

is a root of the equation

or

where

The function

we will call "the characteristic function of the system (

33)".

Let us note the following statements [

19].

Remark 5. The statements " is an equilibrium of the system (33)" and " is a root of the equation (37)" are equivalent.

Remark 6.

For all

where . Therefore, if

or

then there exists at least one nonzero root of the equation (37).

Remark 7. The condition (38) contradicts to the necessary condition (7) for asymptotic stability of the zero solution of the linear system (5). Thus, by the condition (38) the zero solution of the linear system (5) is unstable.

Theorem 4. Let be a positive root of the equation (37).

- -

If is a point of stable equilibrium of the system (33) then , i.e., is a point of the decreasing of the characteristic function . - -

If is a point of the increasing of the characteristic function , i.e., , then is a point of unstable equilibrium of the system (33).

Remark 8. Let be a point of an extremum of the characteristic function . In this case and is a point of one-sided stable of equilibrium of the system (33). It means that if the system stays in a point x from small enough neighborhood of and then the solution converges to . But if the system stays in a point x from small enough neighborhood of and then the solution goes away from .

Remark 9. Since the function is an even function then for negative roots of the equation (37) the pictures are symmetrical.

3.1. Stochastic Perturbations and Linearization

Let us suppose that the second equation of the system (

33) is influenced by additive stochastic perturbations of the form

, where

is a nonzero root of the equation (

37) and

is defined in (

13). Then similarly to (

34) we obtain:

Putting

,

and using (

6), (

36), let us transform the second equation of the system (

39) by the following way

Using elementary trigonometric transformations and linearization

we obtain

or similarly to (

11), (

14) in the form of the system of neutral type differential equations

where

Note that the system (

41), (

42) has the form of the system (

14). So, using Theorems 2 and 3 we obtain the following

Theorem 5.

Let be

where , , are defined in (6). Then the nonzero equilibrium of the system (39) is stable in probability.

4. Numerical Simulation

4.1. Difference Analogue of the System (34)

Put in (

34)

where

,

, and

is the Dirac delta-function. Then

and the system (

34) takes the form

Similarly to [

16,

18,

28], consider the difference analogue of the system (

46) in the form

where

Remark 10.

In the case (44) the conditions (6) and (7) are respectively

and

Note that if, for instance, then from the first inequality (49) it follows that , but from the second one it follows that . This means that stabilization by control of the form is impossible.

4.2. Difference Analogue of the System (39)

Using (

45) for the system (

39), we obtain

Similarly to (

47), (

48), the difference analogue of the system (

50) has the form

4.3. Examples

Below two examples are considered, where the difference analogues (

47) and (

51) are used for numerical simulation of solutions of the systems (

46) and (

50). Similarly to [

26,

27], for numerical simulation of the Poisson process

the continuous random variable

is used, uniformly distributed on the interval

:

if

and

in the contrary case. A special algorithm for numerical simulation of the standard Wiener process and examples with stochastic perturbations of the white noise type are described in detail in [

19], so, below it is supposed that

. In both examples one can see that some trajectories have discontinuities, that is a consequence of the Poisson process jumps.

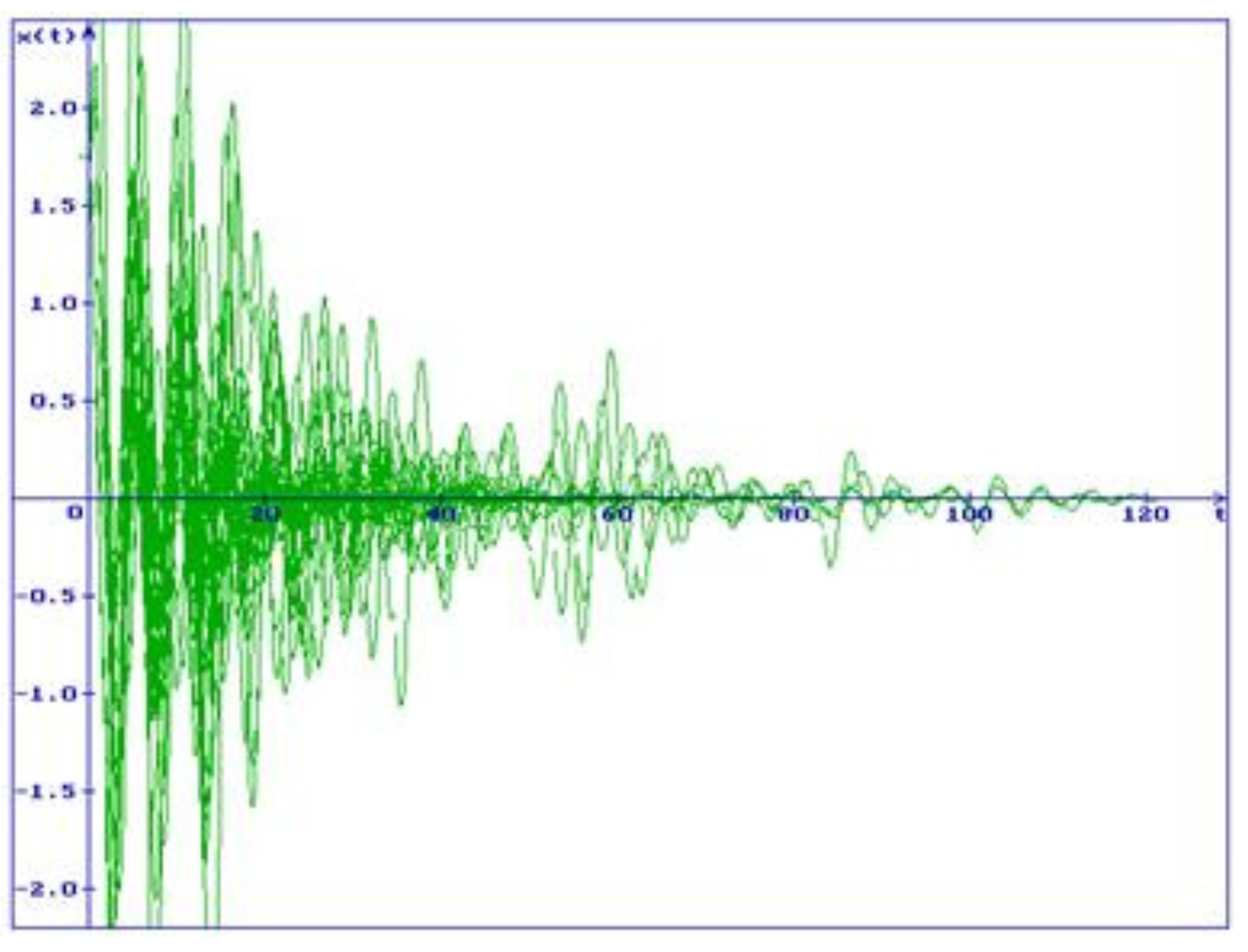

Example 1. Consider the system (46) with , , , , , , , and the initial conditions , . By this , , , , the conditions (18) hold, the zero solution of the system (46) is stable in probability (Theorem 3), all trajectories converge to the zero (Figure 2).

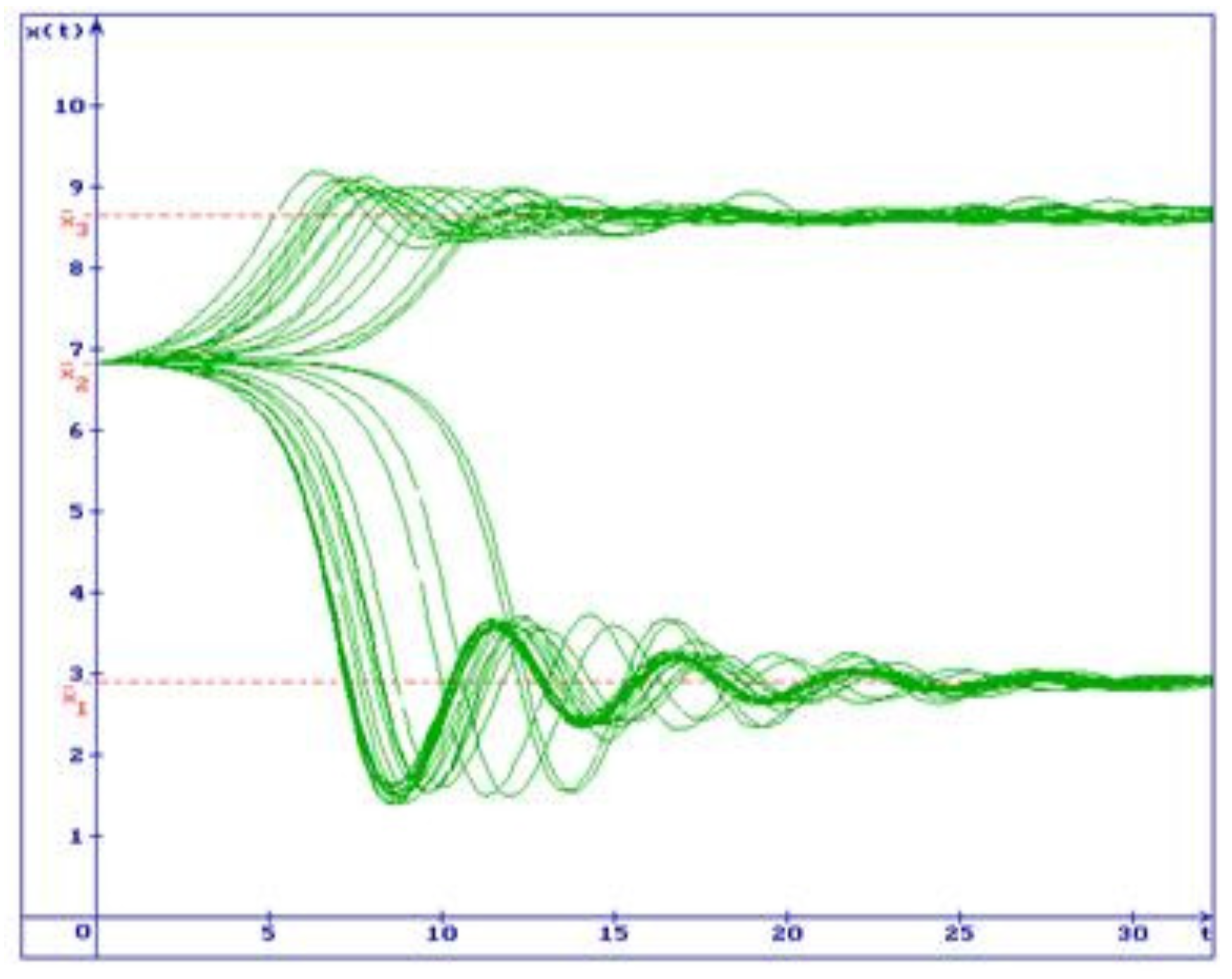

Example 2. Consider the system (50) with , , , , , , , . In this case , , and . Thus, the first condition (7) does not hold and, consequently, the zero solution of the system (35) is unstable. By that, the equation (37) has three positive roots: , , , which are equilibria of the system (33) (Remark 5). For these equilibria we have respectively: , ; , ; , . Besides, , , . From Theorems 4 and 5 it follows that the equilibria and are stable in probability, the equilibrium is unstable. In Fig.3 50 trajectories of the system (50) solution are shown with the initial condition , , . One can see that all trajectories go out from the unstable equilibrium . By that, a part of the trajectories converges to the stable equilibrium , while another one converges to the stable equilibrium .

5. Conclusions

In this paper the classical problem of stabilization for the inverted pendulum is considered under stochastic perturbations of the type of Poisson’s jumps. The linear and nonlinear models are studied, stability conditions for the zero and nonzero equilibria are investigated. The obtained results are illustrated by numerical simulation of solutions of the equations under consideration. The proposed here research method can be used for detail investigation of many other nonlinear mathematical models in different applications.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Acheson D.J. A pendulum theorem. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Seria A. Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 1993, 443, 239-245. [CrossRef]

- Acheson D.J., Mullin T. Upside-down pendulums. Nature, 1993, 366(6452), 215-216. [CrossRef]

- Blackburn J.A., Smith H.J.T, Gronbech-Jensen N. Stability and Hopf bifurcations in an inverted pendulum. American Journal of Physics, 1992, 60(10), 903-908. [CrossRef]

- Borne P., Kolmanovskii V., Shaikhet L. Steady-state solutions of nonlinear model of inverted pendulum. Theory of Stochastic Processes, 1999, 5(21)(3-4), 203-209. Proceedings of the third Ukrainian-Scandinavian conference in probability theory and mathematical statistics, 8–12 June 1999, Kyiv, Ukraine.

- Borne P., Kolmanovskii V., Shaikhet L. Stabilization of inverted pendulum by control with delay. Dynamic Systems and Applications, 2000, 9(4), 501-514.

- Imkeller P, Lederer Ch. Some formulas for Lyapunov exponents and rotation numbers in two dimensions and the stability of the harmonic oscillator and the inverted pendulum. Dynamical Systems, 2001, 16(1), 29-61. [CrossRef]

- Kapitza P.L. Dynamical stability of a pendulum when its point of suspension vibrates, and pendulum with a vibrating suspension. In: ter Haar D (ed) Collected papers of P.L. Kapitza, vol 2. Pergamon Press, London, 714-737.

- Levi M. Stability of the inverted pendulum — a topological explanation. SIAM Review, 1988, 30(4), 639-644. [CrossRef]

- Levi M, Weckesser W. Stabilization of the inverted linearized pendulum by high frequency vibrations. SIAM Review, 1995, 37(2), 219-223. [CrossRef]

- Mata G.J., Pestana E. Effective Hamiltonian and dynamic stability of the inverted pendulum. European Journal of Physics, 2004, 25(6), 717-721.

- Mitchell R. Stability of the inverted pendulum subjected to almost periodic and stochastic base motion — an application of the method of averaging. International Journal of Nonlinear Mechanics, 1972, 7(1), 101-123. [CrossRef]

- Ovseyevich A.I. The stability of an inverted pendulum when there are rapid random oscillations of the suspension point. International Journal of Applied Mathematics and Mechanics, 2006, 70(5), 762-768. [CrossRef]

- Saleem O., Mahmood-ul-Hasan K. Robust stabilisation of rotary inverted pendulum using intelligently optimised nonlinear self-adaptive dual fractional-order PD controllers. International Journal of Systems Science, 2019, 50(7), 1399-1414. [CrossRef]

- Sanz-Serna J.M. Stabilizing with a hammer. Stochastics and Dynamics, 2008, 8(1), 47-57.

- Sharp R., Tsai Y-H., Engquist B. Multiple time scale numerical methods for the inverted pendulum problem. In: Multiscale methods in science and engineering. Lecture notes computing science and engineering, Springer, Berlin, 2005, 44, 241-261.

- Shaikhet L. Stability of difference analogue of linear mathematical inverted pendulum. Discrete Dynamics in Nature and Society, 2005, 2005(3), 215-226. Article ID 149487. [CrossRef]

- Shaikhet L. Improved condition for stabilization of controlled inverted pendulum under stochastic perturbations. Discrete and Continuous Dynamical Systems - A, 2009, 24(4), 1335-1343. [CrossRef]

- Shaikhet L. Lyapunov functionals and stability of stochastic difference equations. Springer Science & Business Media, 2011. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-0-85729-685-6.

- Shaikhet L. Lyapunov functionals and stability of stochastic functional differential equations, Springer Science & Business Media, 2013. https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-319-00101-2.

- Gikhman I.I., Skorokhod A.V. Stochastic Differential Equations, Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1972.

- Gikhman I.I., Skorokhod A.V. The theory of stochastic processes, v.III, Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1979.

- Kolmanovskii V.B., Nosov V.R. Stability of Functional Differential Equations, Academic press, London, 1986.

- Kolmanovskii V.B., Myshkis A.D. Applied theory of functional differential equations, Kluwer Academic, Dordrecht, 1992.

- Kolmanovskii V.B., Myshkis A.D. Introduction to the theory and applications of functional differential equations. Kluwer Academic, Dordrecht, 1999.

- Mao X. Exponential stability of stochastic differential equations, Marcel Dekker, New York, 1994.

- Shaikhet L. Stability of the neoclassical growth model under perturbations of the type of Poisson’s jumps: analytical and numerical analysis. Communications in Nonlinear Science and Numerical Simulation, 2019, 72, 78-87. [CrossRef]

- Shaikhet L. About stabilization by Poisson’s jumps for stochastic differential equations. Applied Mathematics Letters, 2024, 153, 109068, 6 p. https://authors.elsevier.com/sd/article/S0893-9659(24)00088-0.

- Shaikhet L. Stability of difference analogues of nonlinear integro-differential equations: a survey of some known results. Research and Communications in Mathematics and Mathematical Sciences, Jyoti Academic Press, 2024, 16(1), 21-84.https://jyotiacademicpress.org/jyotic/journalview/16/article/66/112.

- Khasminskii R.Z. Stochastic stability of differential equations. Springer, 2012.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).