Submitted:

25 November 2024

Posted:

27 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

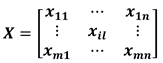

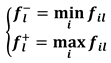

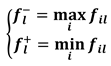

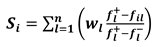

2. Materials and Methods

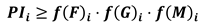

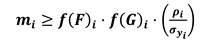

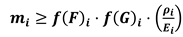

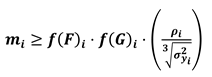

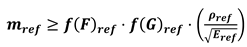

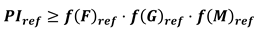

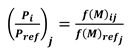

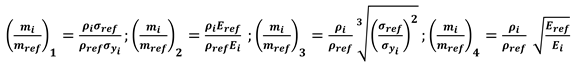

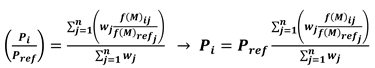

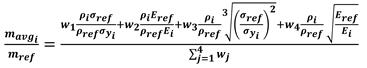

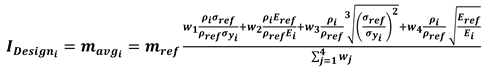

2.1. Method for materials selection

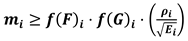

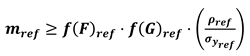

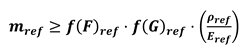

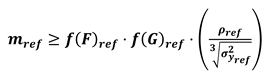

- without the need of considering the assumptions f(F)i = f(F)ref and f(G)i = f(G)ref

- setting parameters (PIi/PIref)j according to the needs of the specific case study.

2.2. Case Study

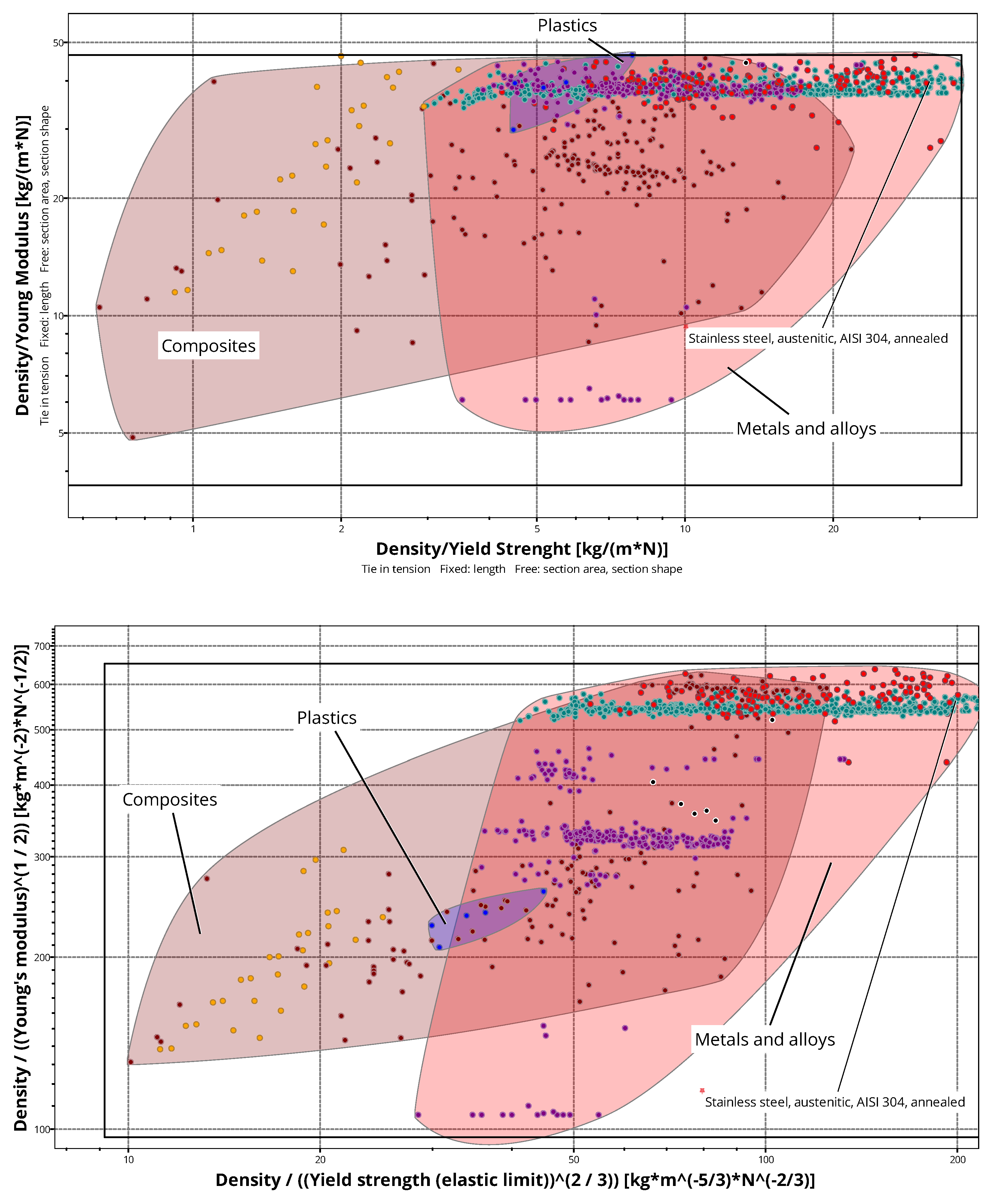

- the first one provides the ratio on the x-axis and the ratio on the y-axis, thus highlighting the ability of the material under tensile/compression loads to be light but at the same time rigid and strong (the lower the values, the better the material);

- the second one provides the ratio on the x-axis and the ratio on the y-axis, thus highlighting the ability of the material under torque bending loads to be light, but at the same time rigid and strong (the lower the values, the better the material).

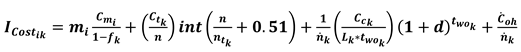

- parameters , , d, are those predefined by the Granta Selector software and they are assumed constant for each industrial process: , , d = 0.05, ;

- as the case study deals with a large-scale production electric vehicle, parameter n is set to 100000 units;

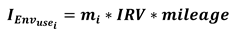

- it is assumed that the bracket component is manually disassembled, so the specific environmental impact of disassembly step (ccDis) is set to 0 [kgCO2_eq/kg];

- the specific impact of the shredding phase () is assumed constant for all materials selected, and it is considered an average value taking into account the shredding of the entire vehicle (0.0175 [kgCO2_eq/kg]), as provided by [65]. The same assumption is made for the disposal phase, for which is assumed 0.03 [kgCO2_eq/kg] (data from [69]);

- recycling is provided only for metals and metallic fibers. SF is considered constant for the same material, and it is assumed -0.25 for ferrous alloys and -0.15 for non-ferrous alloys. For other materials SF is assumed 0;

- is set to 0.98 for metal alloys, while for metallic fibers it is calculated as ;

- is provided by Granta Selector Database [64] for each material option explored;

- is set to 0.3;

- is derived from EcoInvent-APOS391 database considering the specific energy generation process “heat, district or industrial, natural gas | market for heat, district or industrial, natural gas/ heat and power co-generation, natural gas, conventional power plant” [70];

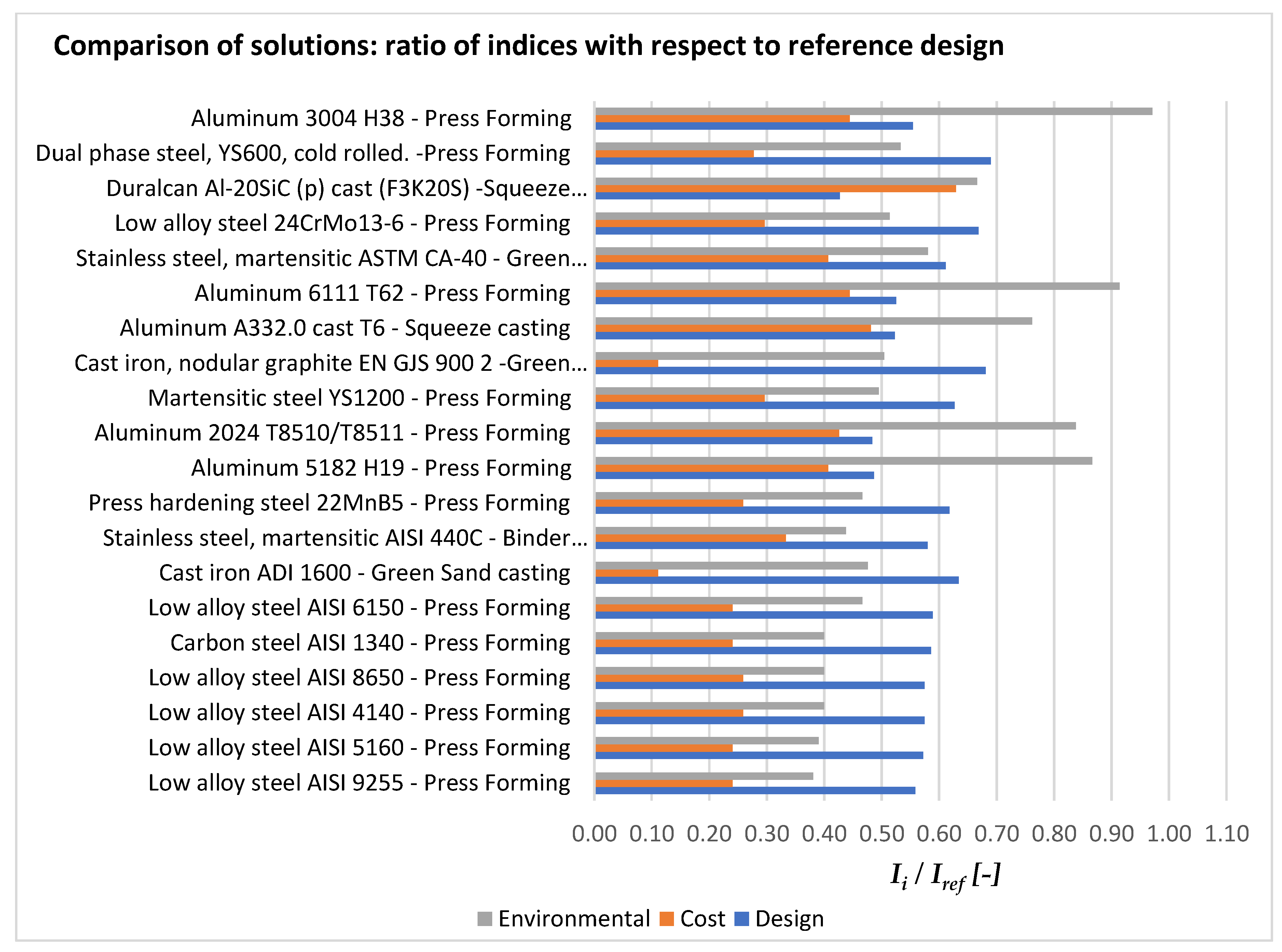

- since the case study deals with a large volume production component, it is chosen to give priority to the cost aspect, for which the corresponding index (ICost) is assumed to be four times more relevant than the other two indices (IDesign and IEnv). Consequently, the resulting weights for design, cost and sustainability aspects are respectively , , ;

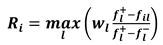

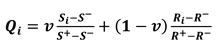

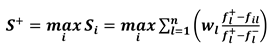

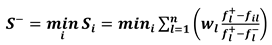

- all three indices are considered “cost attributes”, so in the ranking performed through the VIKOR the lower the index value, the better the solution.

3. Results and discussion

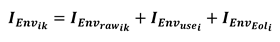

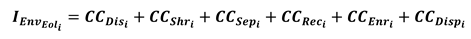

- -

- component mass (corresponding to , as provided by Equation 15);

- -

- cost of raw materials (corresponding to *, as provided by Equation 16);

- -

- total component cost (, as provided by Equation 16);

- -

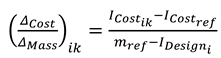

- cost variation in relation to weight reduction (corresponding to coefficient , as provided by Equation 33);

- -

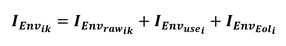

- environmental impact of component use stage (, as provided by Equation 19);

- -

- environmental impact of entire component LC (, as provided by Equation 17);

- -

- single score , based on which the VIKOR provides the ranking.

| Ranking | Design solution | Mass [kg] | Cost | CC [kgCO2_eq] | Qi | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw Material [Eur] |

Total [Eur] |

[Eur/kg] | Use | Total LC | ||||

| Ref: Stainless steel austenitic AISI 304 annealed–Press Forming | REF: 8.91 | REF: 50 | REF: 54 | REF: 49 | REF: 105 | |||

| 1 | Low alloy steel, AISI 9255, oil quenched & tempered at 205°C - Press Forming | 4.98 | 9 | 13 | -14 | 27.6 | 40 | 0.0149 |

| 2 | Low alloy steel, AISI 5160, oil quenched & tempered at 205°C - Press Forming | 5.10 | 9 | 13 | -14 | 28.3 | 41 | 0.0195 |

| 3 | Low alloy steel, AISI 4140, oil quenched & tempered at 205°C - Press Forming | 5.12 | 10 | 14 | -14 | 28.4 | 42 | 0.0211 |

| 4 | Low alloy steel, AISI 8650, oil quenched & tempered at 205°C - Press Forming | 5.12 | 11 | 14 | -14 | 28.4 | 42 | 0.0225 |

| 5 | Carbon steel, AISI 1340, oil quenched & tempered at 205°C - Press Forming | 5.22 | 9 | 13 | -15 | 29 | 42 | 0.0242 |

| 6 | Low alloy steel, AISI 6150, oil quenched & tempered at 205°C - Press Forming | 5.25 | 10 | 13 | -11 | 28.8 | 49 | 0.0268 |

| 7 | Cast-iron, austempered ductile, ADI 1600 - Green Sand casting, automated | 5.65 | 4 | 6 | -15 | 31.3 | 50 | 0.0340 |

| 8 | Stainless steel, martensitic, AISI 440C, tempered at 316°C - Binder Jetting | 5.17 | 10 | 18 | -10 | 28.7 | 46 | 0.0352 |

| 9 | Press hardening steel, 22MnB5, austenized & H20 quenched, coated - Press Forming | 5.51 | 10 | 14 | -12 | 30.6 | 49 | 0.0396 |

| 10 | Aluminum, 5182, H19 - Press Forming | 4.34 | 19 | 22 | -7 | 24.1 | 91 | 0.0436 |

| 11 | Aluminum, 2024, T8510/T8511 - Press Forming | 4.31 | 20 | 23 | -7 | 23.3 | 88 | 0.0436 |

| 12 | Martensitic steel, YS1200, hot rolled - Press Forming | 5.59 | 12 | 16 | -11 | 31 | 52 | 0.0483 |

| 13 | Cast-iron, nodular graphite, EN GJS 900 2, hardened & tempered - Green Sand casting, automated | 6.07 | 4 | 6 | -17 | 33.7 | 53 | 0.0592 |

| 14 | Aluminum, A332.0, cast, T6 - Squeeze casting | 4.66 | 19 | 26 | -7 | 25.8 | 80 | 0.0592 |

| 15 | Aluminum, 6111, T62 - Press Forming | 4.68 | 20 | 24 | -7 | 26 | 96 | 0.0615 |

| 16 | Stainless steel, martensitic, ASTM CA-40, cast, tempered at 315°C - Green Sand casting, automated | 5.45 | 20 | 22 | -9 | 30.3 | 61 | 0.0633 |

| 17 | Low alloy steel, 24CrMo13-6, quenched & tempered - Press Forming | 5.96 | 13 | 16 | -13 | 33 | 54 | 0.0650 |

| 18 | Duralcan Al-20SiC (p) cast (F3K20S) - Squeeze casting | 3.81 | 28 | 34 | -4 | 21.1 | 70 | 0.0691 |

| 19 | Dual phase steel, YS600, cold rolled - Press Forming | 6.15 | 12 | 15 | -14 | 34.1 | 56 | 0.0716 |

| 20 | Aluminum, 3004, H38 - Press Forming | 4.94 | 21 | 24 | -7 | 27.4 | 102 | 0.0771 |

5. Conclusions

References

- IEA. CO2 Emissions in 2022. IEA 2023, Paris.

- Ferreira, V.; et al. Technical and environmental evaluation of a new high performance material based on magnesium alloy reinforced with submicrometre-sized TiC particles to develop automotive lightweight components and make transport sector more sustainabl. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2019, 8, 2549–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Commission European. White Paper: Roadmap to a Single European Transport Area—Towards a Competitive and Resource Efficient Transport System. European Commission: Brussels, Belgium. 2011, /* COM/2011/0144 final */.

- Brooke, L.; Evans, H. Lighten up! Automot. Eng. 2009, 117, 16–22. [Google Scholar]

- Goede, M. Super Light Car—Lightweight construction thanks to a multi-material design and function integration. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2009, 1, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, V.; et al. Lightweight automotive components based on nano-diamond-reinforced aluminium alloy: A technical and environmental evaluation. Diam. Relat. Mater 2019, 92, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, J.C.; Sullivan, J.L.; Burnham, A.; Elgowainy, A. Impacts of vehicle weight reduction via material substitution on life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions. Environ. Sci. Technol 2015, 49, 12535–12542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaguar Land Rover Using Aerospace Technology to Develop Future Lightweight Vehicles. https://media.jaguarlandrover.com/news/2020/10/jaguar-land-rover-using-aerospace-technology-develop-future-lightweight-vehicles. 22 October 2020.

- The lightweight New A8 - Unique mix of materials used in the next Audi milestone. https://press.audi.co.uk/en-gb/releases/52#:~:text=Picture%20caption,A8%20for%20the%20first%20time. 5 April 2017.

- Stellantis Fosters Circular Economy Ambitions with Dedicated Business Unit to Power New Era of Sustainable Manufacturing and Consumption. https://www.stellantis.com/en/news/press-releases/2022/october/stellantis-fosters-circular-economy-ambitions-with-dedicated-business-unit-to-power-new-era-of-sustainable-manufacturing-and-consumption. 11 October 2022.

- Koffler, C.; Rohde-Brandenburger, K. On the Calculation of Fuel Savings Through Lightweight Design in Automotive Life Cycle Assessments. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2010, 15, 128–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.C.; Wallington, T.J. Life Cycle Assessment of Vehicle Lightweight-ing: A Physics-Based Model to Estimate Use-Phase Fuel Consumption of Electrified Vehicles. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 11226–11233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroll, L.; et al. Lightweight Components for Energy-Efficient Machine Tools. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2011, 4, 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neugebauer, R.; et al. Structure Principles of Energy Efficient Machine Tools. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2011, 4, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Xu, J. Advanced lightweight materials for Automobiles: A review. Materials & Design 2022, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mascarin, A.; Hannibal, T.; Raghunathan, A.; Ivanic, Z.; Francfort, J. Vehicle Lightweighting: 40% and 45% Weight Savings Analysis: Technical Cost Modeling for Vehicle Lightweighting. United States: N. p.: S.n., 2015.

- Tisza, M.; Czinege, I. Comparative study of the application of steels and aluminium in lightweight production of automotive parts. Int. J. Lightweight Mater. Manuf. 2018, 1, 229–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, P.K. Materials, Design and Manufacturing for Lightweight Vehicles, 2nd edition, 2020.

- Kumar, D.; Kumar, R.P.; Thakur, L. A review on environment friendly and lightweight Magnesium-Based metal matrix composites and alloys. Materials Today Proceedings 2021, 38, 359–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galán, J.; et al. Advanced high strength steels for automotive industry. Revista de metalurgia 2012, 48, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wazeer, A.; Das, A.; Abeykoon, C.; Sinha, A.; Karmakar, A. Composites for electric vehicles and automotive sector: A review. Green Energy and Intelligent Transportation 2023, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourmaud, A.; Fazzini, M.; Renouard, N.; Behlouli, K.; Ouagne, P. Innovating routes for the reused of PP-flax and PP-glass non woven composites: A comparative study. Polymer Degradation and Stability 2018, 152, 259–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmarakbi, A.; Azoti, W. State of the Art on Graphene Lightweighting Nanocomposites for Automotive Applications. Experimental Characterization, Predictive Mechanical and Thermal Modeling of Nanostructures and their Polymer Composite; Marotti de Sciarra, F., Russo, P., 2018, 1-23.

- La Rosa, A.D.; et al. ; Biobased versus traditional polymer composites. A life cycle assessment perspective. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 74, 135–144. [Google Scholar]

- Schönemann, M.; Schmidt, C.; Herrmann, C.; Thiede, S. Multi-level modeling and simulation of manufacturing systems for lightweight automotive components. Procedia CIRP 2016, 41, 1049–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iadicola, M.A.; Creuziger, A.A.; Luecke, W.E.; Banerjee, D.K.; Gnaupel-Herold, T.H. Automotive Lightweighting. NIST, 2008. Available online: https://www.nist.gov/programs-projects/automotive-lightweighting (accessed on 22 October 2020).

- Priarone, P.C.; Catalano, A.R.; Settineri, L. Additive manufacturing for the automotive industry: On the life-cycle environmental implications of material substitution and lightweighting through re-design. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 8, 1229–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dattilo, C.A.; Zanchi, L.; Del Pero, F.; Delogu, M. Sustainable design: An integrated approach for lightweighting components in the automotive sector. SDM-2017: 4th International Conference on Sustainable Design and Manufacturing, 2017.

- Simoes, C.L.; Figueiredo de Sà, R.; Ribeiro, C.J.; Bernardo, P.; Pontes, A.J.; Bernardo, C.A. Environmental and economic performance of a car component: Assessing new materials, processes and designs. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 118, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delogu, M.; Zanchi, L.; Maltese, S.; Bonoli, A.; Pierini, M. Environmental and economic life cycle assessment of a lightweight solution for an automotive component: A comparison between talc-filled and hollow glass microspheres-reinforced polymer composites. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 139, 548–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vita, A.; Castorani, V.; Germani, M.; Marconi, M. Comparative life cycle assessment of low-pressure RTM, compression RTM and high-pressure RTM manufacturing processes to produce CFRP car hoods. Procedia CIRP 2019, 80, 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanchi, L.; Delogu, M.; Ierides, M.; Vasiliadis, H. Life cycle assessment and life cycle costing as supporting tools for EVs lightweight design. Sustain. Des. Manuf. 2016, 52, 335–348. [Google Scholar]

- Fiebig, S.; Sellschopp, J.; Manz, H.; Vietor, T.; Axmann, J.K.; Schumacher, A. Future challenges for topology optimization for the usage in automotive lightweight design technologies. 11th World Congress on Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimisation, Sydney, Australia, June 2015.

- Işık, M.; et al. Topology optimization and manufacturing of engine bracket using electron beam melting. J. Addit. Manuf. Technol. 2021, 1, 583. [Google Scholar]

- Puri, P.; Compston, P.; Pantano, V. Life Cycle assessment of Australian automotive door skins. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2009, 14, 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delogu, M.; Del Pero, F.; Romoli, F.; Pierini, M. Life cycle assessment of a plastic air intake manifold. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2015, 20, 1429–1443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulikidou, S.; Jerpdal, L.; Björklund, A.; Åkermo, M. Environmental performance of self-reinforced composites in automotive applications. Case study on a heavy truck component. Mater. Des. 2016, 103, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inti, S.; Sharma, M.; Tandon, V. An approach for performing life cycle impact assessment of pavements for evaluating alternative pavement designs. Int. Conf. on Sust. Des. Eng. and Const 2016, 145, 964–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayyas, A.T.; Qattawi, A.; Mayyas, A.R.; Omar, M.A. Life cycle assessment-based selection for a sustainable lightweight body-in-white design. Energy 2012, 39, 412–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, M.F.; Johnson, K. Materials and Design: The Art and Science of Material Selection in Product Design, 2nd ed.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2013.

- Camargo, D.Z.; et al. Selection of Materials for Weight Reduction in Sports Cars. Adv. Mater. Res. 2019, 1152, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashby, F. Multi-Objective Optimization in Material Design and Selection. Acta Mater. 2000, 48, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, G.M.; et al. Green Principles for Vehicle Lightweighting. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 4063–4077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, R.V.; Patel, B.K. A subjective and objective integrated multiple attribute decision making method. Mater. Des. 2010, 37, 4738–4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojčić, M.; et al. Application of MCDM Methods in Sustainability Engineering: A Literature Review 2008–2018. Symmetry 2019, 11, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, C.L.; Yoon, K. Methods for Multiple Attribute Decision Making. In: Multiple Attribute Decision Making. Lecture Notes in Economics and Mathematical Systems, vol. 186. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 1981.

- Opricovic, S. Multicriteria optimization of civil engineering systems. Faculty of Civil Engineering: Belgrade, Serbia, 1998; pp. 5–21.

- Chatterjee, P.; Chakraborty, S. A comparative analysis of VIKOR method and its variants. Decis. Sci. Lett. 2016, 5, 469–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavadskas, E.K.; Kaklauskas, A.; Šarka, S. The new method of multicriteria evaluation of projects. Tech. and Economic Dev. of Ec. 1996, 1, 131–139. [Google Scholar]

- Mousavi-Nasab, S.H.; Sotoudeh-Anvari, A. A comprehensive MCDM-based approach using TOPSIS, COPRAS, and DEA as an auxiliary tool for material selection problems. Mater. Des. 2017, 121, 237–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brans, J.P.; Nadeau, R.; Landry, M. L’ingénierie de la décision. Elaboration d’instruments d’aide à la décision. La méthode PROMETHEE. In: L’Aide à la Décision: Nature, Instruments et Perspectives d’Avenir, 1982, pp.183-213.

- Brans, J.P.; De Smet, Y. PROMETHEE Methods. In: Greco, S.; Ehrgott, M.; Figueira, J. (eds) Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis. International Series in Operations Research & Management Science, vol. 233. Springer, New York, NY, 2016.

- Roy, B. Classement et choix en présence de points de vue multiples. Rev. Fr. Inf. Rech. Opér. 1968, 2, 57–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueira, J.R.; Mousseau, V.; Roy, B. ELECTRE Methods. In: Greco, S.; Ehrgott, M.; Figueira, J. (eds) Multiple Criteria Decision Analysis. International Series in Operations Research & Management Science, vol. 233. Springer, New York, NY, 2016.

- Brauers, W.K.M. Optimization Methods for a Stakeholder Society. A Revolution in Economic Thinking by Multiobjective Optimization. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Boston, 2004.

- Chakraborty, S. Applications of the MOORA method for decision making in manufacturing environment. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2011, 54, 1155–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Ray, A. Selection of material for optimal design using multi-criteria decision making. Procedia Mater. Sci. 2014, 6, 590–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgetti, A.; Cavallini, C.; Arcidiacono, G.; Citti, P. A mixed C-VIKOR fuzzy approach for material selection during design phase: A case study in valve seats for high performance engine. Int. J. Appl. Eng. Res. 2017, 12, 3117–3129. [Google Scholar]

- Jahan, A.; Mustapha, F.; Ismail, M.; Sapuan, S.; Bahraminasab, M. A comprehensive VIKOR method for material selection. Mater. Des. 2011, 32, 1215–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manalo, M.V.; Magdaluyo, E.R. Integrated DLM-COPRAS method in material selection of laminated glass interlayer for a fuel-efficient concept vehicle. World Congress on Engineering, London, UK, 2018; Vol. 2.

- Gul, M.; Celik, E.; Gumus, A.; Guneri, A. A fuzzy logic based PROMETHEE method for material selection problems. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2018, 7, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, C.; Taleb, M.; Zakia, R.; Rajaa, B.; El Haji, M. Electre multicriteria analysis for choosing material concerned by the corrosion problem. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Stud. 2020, 3, 132–146. [Google Scholar]

- Sen, B.; Bhattacharjee, P.; Mandal, U. A comparative study of some prominent multi criteria decision making methods for connecting rod material selection. Perspect. Sci. 2016, 8, 547–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ANSYS. Available online: https://www.ansys.com/it-it/products/materials/granta-selector (accessed on 17 July 2024).

- Del Pero, F.; Berzi, L.; Antonacci, A.; Delogu, M. Automotive Lightweight Design: Simulation Modeling of Mass-Related Consumption for Electric Vehicles. Machines 2020, 8, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonacci, A.; Del Pero, F.; Baldanzini, N.; Delogu, M. Holistic eco-design tool within automotive field. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Więckowski, J.; Sałabun, W. How the normalization of the decision matrix influences the results in the VIKOR method? Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 176, 2222–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, H.K.; et al. Strength-Based Design Analysis of a Damaged Engine Mounting Bracket Designed for a Commercial Electric Vehicle. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 2021, 21, 1315–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pero, F.; Berzi, L.; Dattilo, C.A.; Delogu, M. Environmental sustainability analysis of Formula-E electric motor. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 2021, 235, 303–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecoinvent. Available online: https://ecoinvent.org/ (accessed on 17 July 2024).

| IRV (kgCO2_eq/(100km*100kg)) | |||

| NEDC | WLTP | ALDC | |

| NO | IRVNO_NEDC = 3.0*10-6M+0.0116 | IRVNO_WLT P = 4.0*10-6M+0.0121 | IRVNO_WLTP = 4.0*10-6M+0.0121 |

| EU28 | IRVEU28_NEDC = 4.7*10-5 M+0.1591 | IRVEU28_WLTP = 5.6*10-5 M+0.1655 | IRVEU28_ALDC = 1.2*10-4M+0.2231 |

| PL | IRVPL_NEDC = 1.1*10-4 M+0.3798 | IRVPL_WLTP = 1.3*10-4 M+0.3951 | IRVPL_ALDC = 2.8*10-4 M+0.5326 |

| Motor Mounting Bracket component | |

| Material | AISI304 Stainless Steel |

| Mass | 8.913 [kg] |

| Max Torque without yielding | 3x10 ^5 [N/mm] |

| Max Displacement | 0.284 [mm] |

| Max Equivalent Stress | 170 [MPa] |

| Industrial Processes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binder Jetting | 0.98 | 0.05 | 316000 | 22.40 | 361000 |

| Squeeze casting | 0.93 | 22200 | 22400 | 30.00 | 393000 |

| Gravity die casting | 0.69 | 10500 | 31600 | 15.80 | 35200 |

| Investment casting, automated (Lost Wax Process) | 0.82 | 6810 | 1580 | 44.70 | 39300 |

| Evaporative pattern casting, automated | 0.49 | 2980 | 7071 | 31.62 | 23086 |

| Shell Casting | 0.49 | 3930 | 3160 | 15.81 | 5560 |

| Ferro die Casting | 0.80 | 44500 | 7070 | 54.80 | 393000 |

| Green Sand casting, automated | 0.63 | 2150 | 31600 | 77.50 | 39300 |

| Replicast casting | 0.69 | 5560 | 3160 | 22.40 | 21500 |

| Press Forming | 0.75 | 78600 | 100000 | 77.50 | 278000 |

| Cold Isostatic Pressing (CIP) | 0.99 | 1470 | 316 | 31.60 | 141000 |

| Material | Price Raw Material [Eur/kg] | Density [kg/m3] | Young Modulus [GPa] | Yield Strength [MPa] | Primary production CC (virgin grade) [kg/kg] |

| Ref: Stainless steel austenitic AISI 304 annealed | 5.29 | 7850 | 196 | 252 | 5.73 |

| Low alloy steel, AISI 9255, oil quenched & tempered at 205°C | 1.38 | 7850 | 211 | 2040 | 2.33 |

| Low alloy steel, AISI 5160, oil quenched & tempered at 205°C | 1.36 | 7850 | 209 | 1780 | 2.33 |

| Low alloy steel, AISI 4140, oil quenched & tempered at 205°C | 1.44 | 7850 | 212 | 1630 | 2.33 |

| Low alloy steel, AISI 8650, oil quenched & tempered at 205°C | 1.56 | 7850 | 211 | 1660 | 2.33 |

| Carbon steel, AISI 1340, oil quenched & tempered at 205°C | 1.36 | 7850 | 207 | 1580 | 2.33 |

| Low alloy steel, AISI 6150, oil quenched & tempered at 205°C. | 1.40 | 7850 | 206 | 1680 | 3.44 |

| Cast-iron, austempered ductile, ADI 1600 | 0.50 | 7060 | 159 | 1360 | 2.43 |

| Stainless steel, martensitic, AISI 440C, tempered at 316°C | 1.89 | 7800 | 200 | 1890 | 4.31 |

| Press hardening steel, 22MnB5, austenized & H20 quenched, coated | 1.36 | 7850 | 210 | 1090 | 2.96 |

| Aluminum, 5182, H19 | 3.23 | 2650 | 70 | 392 | 13 |

| Aluminum, 2024, T8510/T8511 | 3.41 | 2770 | 76 | 398 | 12 |

| Martensitic steel, YS1200, hot rolled | 1.62 | 7850 | 210 | 1020 | 3.35 |

| Cast-iron, nodular graphite, EN GJS 900 2, hardened & tempered | 0.44 | 7150 | 172 | 749 | 2.33 |

| Aluminum, A332.0, cast, T6 | 3.74 | 2700 | 73 | 280 | 12.5 |

| Aluminum, 6111, T62 | 3.18 | 2710 | 69 | 320 | 12.6 |

| Stainless steel, martensitic, ASTM CA-40, cast, tempered at 315°C | 2.29 | 7610 | 200 | 1140 | 4.15 |

| Low alloy steel, 24CrMo13-6, quenched & tempered | 1.60 | 7800 | 200 | 831 | 3.16 |

| Duralcan Al-20SiC (p) cast (F3K20S) | 6.70 | 2810 | 101 | 355 | 11.9 |

| Dual phase steel, YS600, cold rolled | 1.42 | 7850 | 210 | 671 | 3.28 |

| Aluminum, 3004, H38 | 3.15 | 2720 | 70 | 250 | 12.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).