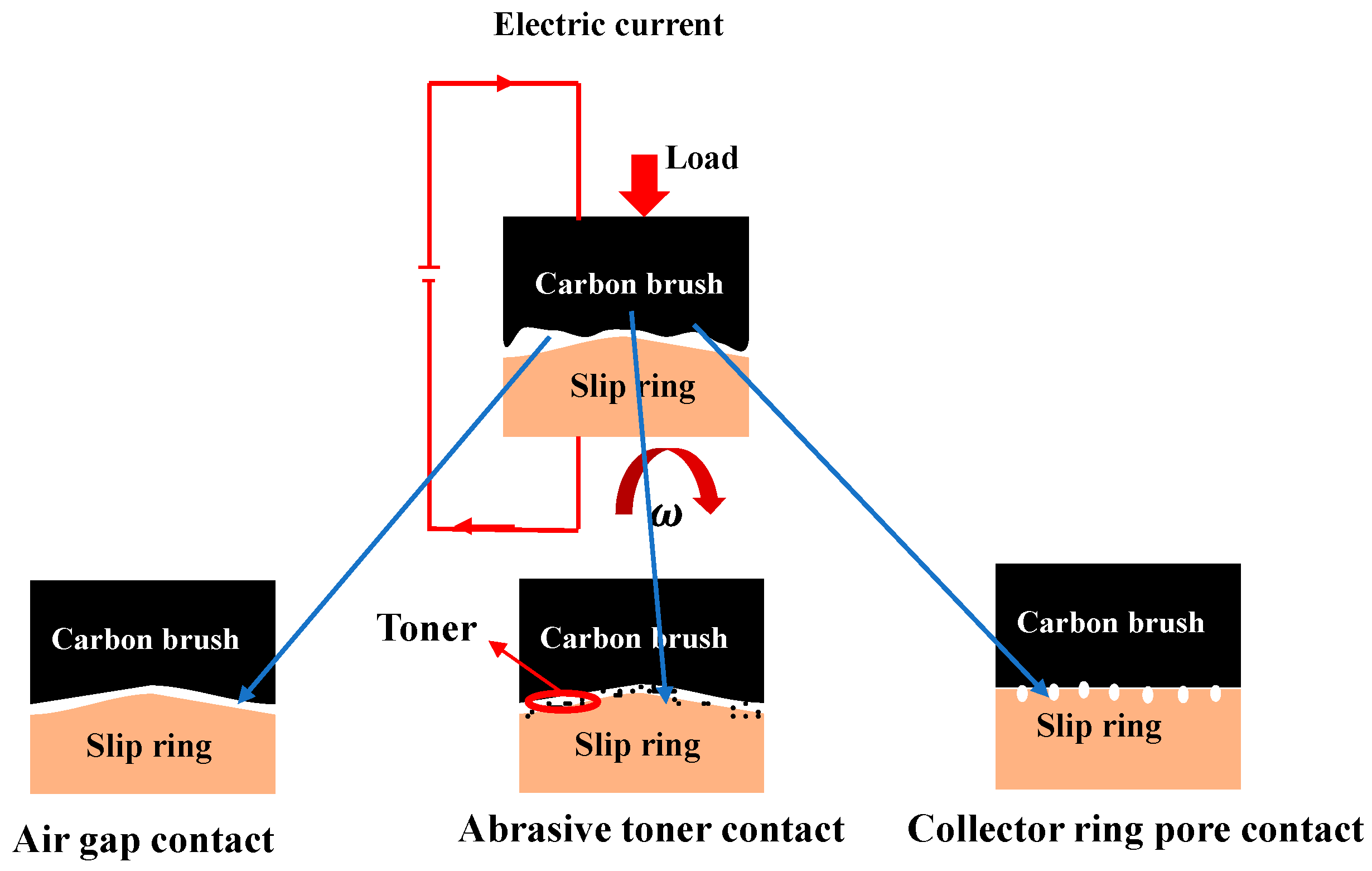

In the actual operation process, due to the vibration of the hydro generator will occur the phenomenon of loss of contact, that is, the air gap contact state described in the article, this state of the current will break through the air and thus the phenomenon of arcing [

21]. in order to explore the effect of arcing on the collector ring, control the brush/ring gap is unchanged, and analysed as shown in

Table 3 for different current-carrying parameters and current-carrying polarity (referring to the carbon brushes connected to the positive and negative poles) under the temperature, arcing power on the surface of the collector ring are specifically investigated.

3.1.1. Change of Positive Electrode Temperature and Arc Power

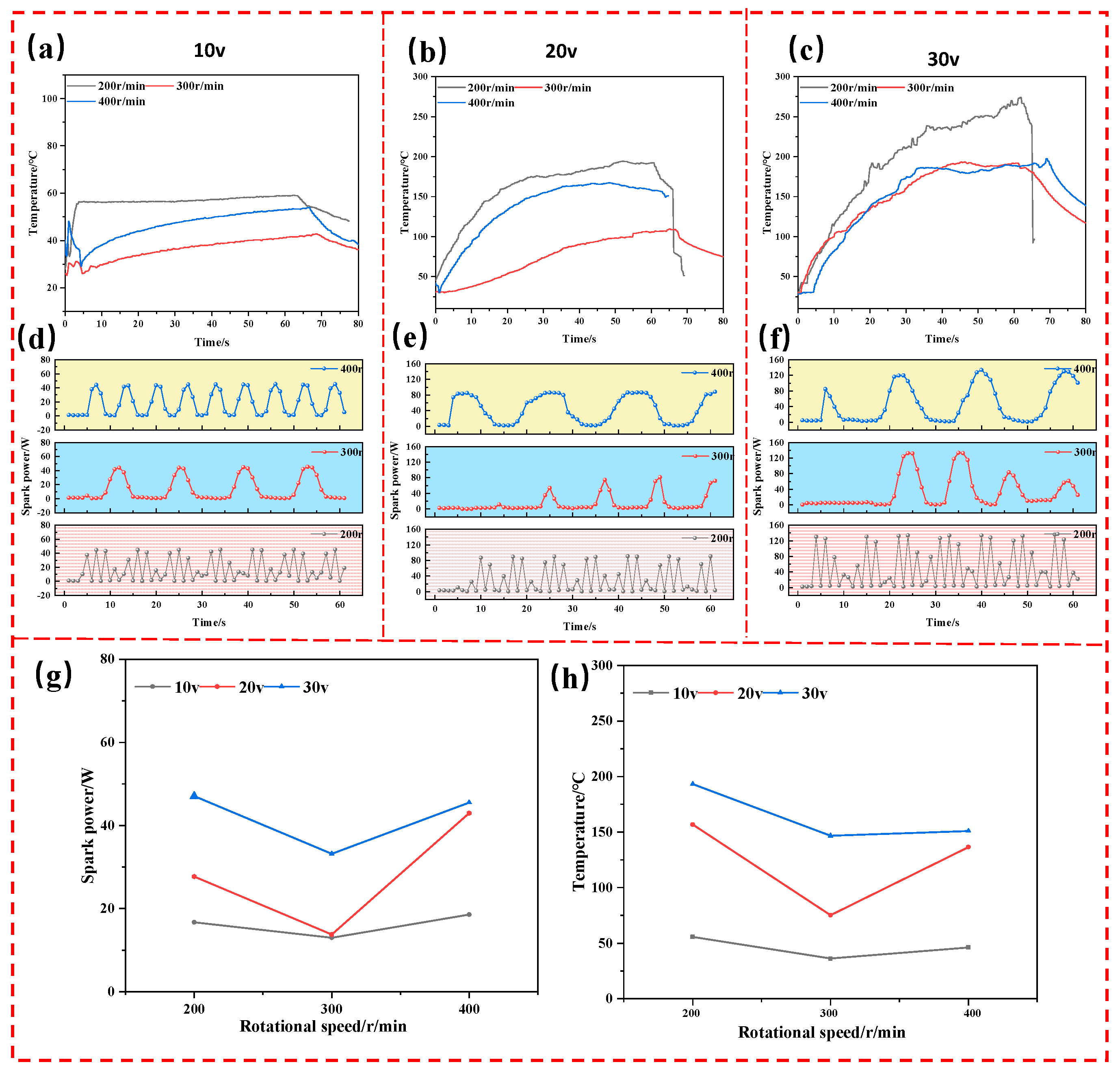

Figure 8 shows the arc power and temperature change curve under different positive voltages and rotational speeds.

Figure 8a shows the temperature change curve of different speeds at 10v, and the temperature is the highest at 200r/min. According to the arc power curve corresponding to 10v in

Figure 8d, it is found that the maximum arc power is the same at different speeds, However, the corresponding discharge frequency is different under different speeds, and the temperature changes accordingly. The discharge frequency is the highest and the temperature is the highest at 200r/min. When the speed reaches 300r/min, the temperature in the air area is the lowest, because the discharge frequency is the least and the corresponding temperature is the lowest, and when the speed rises to 400r/min, the discharge frequency will rise, and the temperature will gradually rise. This means that as the frequency of arcing increases, so does the temperature.

Next, the changes in temperature and arc power under high-voltage conditions are analyzed to determine whether they exhibit patterns similar to those observed at low voltage.

Figure 8b,e depict the temperature variation and arc power curves, respectively, at different rotational speeds under 20 V. The results show that the maximum temperature and arc power values at 20 V are significantly higher than those at low voltage, indicating the amplifying effect of high voltage on the discharge process. While the temperature variation follows a trend similar to that at low voltage, the temperature again reaches its minimum at a rotational speed of 300 r/min. This further highlights the moderating effect of rotational speed on temperature during spark discharge. However, the characteristics of arc generation frequency differ at higher rotational speeds. Specifically, the frequency of arc occurrences decreases significantly under high rotational speed conditions, but the duration of each arc discharge is prolonged. This suggests that at higher rotational speeds, although the arc discharge frequency is reduced, it does not diminish the resulting temperature changes. This phenomenon is likely attributed to the stability of the arc and the heat accumulation effect. The extended intervals between arc discharges at higher speeds may allow for more efficient heat buildup, contributing to the observed temperature rise. In summary, under high-voltage conditions, temperature and arc power not only increase in absolute magnitude but also display both similarities and differences in their dynamic behavior compared to the low-voltage case.

Figure 8c,f see that the maximum values of arc power and temperature increase further when the voltage is increased to 30v, which means that the energy density and temperature of the spark discharge are significantly enhanced at this voltage. When analyzing the temperature variation, the arc occurrence time and frequency will be reduced at high speeds, so the lowest point of temperature will occur at 300 r/min and 400 r/min speeds, but the absolute value will be higher than the case at low voltage and 20V, but due to the increase in energy input, each arc discharge will result in a higher instantaneous temperature.

Based on the above, it was found that the temperature at 300 r/min was the lowest value at 10V and 20V voltage when the carbon brushes were connected to the positive terminal. This phenomenon indicates that at low voltages, the rotational speed has a significant effect on the temperature characteristics of the discharge process. The effect of rotational speed on the frequency of arc discharge is still significant as the voltage increases, and the frequency of arc discharge decreases gradually at high rotational speeds so that the temperatures at 300 r/min and 400 r/min will be close to each other at 30V voltage.

Figure 8g demonstrates the variation curve of the average temperature and

Figure 8h presents the variation curve of the average arc power. From these two figures, it can be seen that the overall trend of arc power and temperature shows a gradual increase as the voltage increases. This indicates that the discharge process under high voltage conditions has a higher temperature and energy density. At a rotational speed of 300 r/min, both the arc discharge frequency and temperature reach the lowest point.

Figure 9 shows the temperature change of carbon brushes under different voltages,

Figure 9 (a) shows the temperature change of carbon brushes under 10v voltage, the highest temperature of carbon brushes under 300r/min is lower, meanwhile, the voltage is gradually increased to 20v, 30v, it can be seen from

Figure 9 b,c that the temperature becomes higher but with the same law, both of them have the lowest temperature under the rotational speed of 300r/min, which is opposite to the result of Fig. 8. . It is concluded that when the carbon brushes are connected to the positive pole, the temperature will be the highest at low voltage and low rotational speed, and the temperature decreases when the rotational speed reaches 300r/min, and the arc power frequency decreases. At high voltage and large rotational speed, the frequency of arc generation is close, the size is close and the maximum value of temperature is close.

3.1.2. Negative Temperature and Arc Power Variation

Figure 10 demonstrates the variation curves of arc power versus temperature for the negative electrode under different voltage and rotational speed conditions.

Figure 10a shows the variation of temperature at different rotational speeds for a voltage of 10V. The results show that the maximum temperature is similar to that of the positive electrode condition, while the lowest temperature is found at 300 r/min rotational speed. 300 r/min rotational speed corresponds to the lowest frequency of arc discharge (

Figure 10d). As the voltage increases,

Figure 10b,c show that the maximum value of the temperature increases, but the effect of the rotational speed on the temperature is more limited and the overall temperature change remains insignificant. At the same time, the maximum temperature that can be achieved when the negative terminal is connected is significantly lower than that of the positive terminal condition. Further analyzing

Figure 10e,f, it can be found that with the increase of voltage, the arc power shows an overall increasing trend, and the corresponding arc discharge frequency also increases gradually.

Figure 10g illustrates the average temperature variation curves under different voltage and rotational speed conditions, while

Figure 10h shows the corresponding average arc power variation curves. The results indicate that at low voltages, the trends of temperature and arc power are similar to those observed under the positive electrode condition, At a rotational speed of 300 r/min, both the average temperature and arc power reach their minimum values. As the voltage increases, the influence of rotational speed on temperature becomes negligible, and temperature changes are no longer significant. This may be due to the lower frequency of arc discharges at this rotational speed, which reduces energy input and minimizes heat generation.

However, as the voltage increases, the trends in temperature and arc power change. While rotational speed remains a variable, its effect on temperature becomes nearly negligible at higher voltages, indicating that temperature is no longer significantly influenced by rotational speed. This suggests that at higher voltages, arc power, and heat generation are primarily determined by the voltage, while the influence of rotational speed weakens. This may be because higher voltages can substantially increase arc power and temperature, whereas variations in rotational speed have a lesser impact on these parameters.

Figure 11 shows the temperature changes of carbon brushes under different voltages.

Figure 11a illustrates the temperature variation at 10 V, where the maximum temperature at 300 r/min is only 49.77°C, the lowest observed value. As the voltage gradually increases to 20 V and 30 V,

Figure 11b,c show that the overall temperature is not significantly affected by the higher rotational speeds.

In general, at higher voltages, the temperature when the negative terminal is connected is always lower than when the positive terminal is connected. When the carbon brushes are connected to the positive terminal, the temperature is highest at low speeds and decreases significantly as the speed increases to 300 r/min, accompanied by a decrease in arc discharge frequency. However, when the speed is further increased to 400 r/min, the discharge frequency rises, and the temperature increases slightly. In contrast, when the carbon brushes are connected to the negative terminal, the firing frequency increases significantly with increasing voltage, but the effect of rotational speed on the firing frequency becomes smaller as the voltage increases. The influence of rotational speed on temperature change is also more limited under these conditions.

3.1.3. Ablation Surface and Mechanism Analysis

Figure 12 demonstrates the morphology of the brush/ring ablation surface when the carbon brush is connected to the positive electrode at different voltages and rotational speeds. At 10 V, there are almost no ablation marks on the ring surface, as shown in

Figure 12a, and only a few ablation spots appear at 200r/min rotational speed. Further observing

Figure 12b,c, when the rotational speed is increased, the ablation marks are almost invisible. As the voltage increases to 20 V, obvious flaky ablation marks appear on the ring surface, and

Figure 12d–f demonstrate this change. However, it can be seen from the figures that the rotational speed has less effect on the ablation marks and the degree of ablation is mainly affected by the voltage. At 30 V, as shown in

Figure 12g–i, a large area of ablation appears on the ring surface, indicating that higher voltages significantly exacerbate the ablation phenomenon. Nonetheless, at 300 r/min rotational speed, the ablation traces are instead lighter, which is consistent with the above trend of temperature and frequency of arc occurrence, indicating that lower rotational speed helps to reduce the degree of ablation.

Figure 13 demonstrates the ablation morphology of the corresponding ring surface of the negative electrode under different operating parameters. Unlike the flaky ablation traces produced by the positive electrode, the surface of the negative electrode ring mostly shows pitting ablation pits. At 10V, only a small number of ablation pits appeared on the ring surface, as shown in

Figure 13a. Further observation of

Figure 13b,c shows that the ablation traces almost disappeared when the rotational speed increased. As the voltage increases to 20V, obvious pitting ablation marks appear on the ring surface, and

Figure 13d–f demonstrate this change. However, it can be seen from the figure that the rotational speed has less effect on the ablation marks and the degree of ablation is mainly affected by the voltage. At a voltage of 30V,

Figure 13g–i shows a large number of pitting ablation traces on the ring surface.

To further explore the effects of polarity and voltage on ablation, the ablation morphology of the carbon brush surface was analyzed under different operating conditions. A rotational speed of 200 r/min was selected to study the ablation areas under various polarities and voltages (

Figure 14).

Figure 14a shows that when the carbon brush is connected to the positive terminal, the main area of ablation is concentrated in the center, while the edges show relatively light ablation. In contrast, when the carbon brush is connected to the negative terminal, the center appears relatively smooth, but significant ablation occurs at the edges. As the voltage increases,

Figure 14b shows that at 20 V, large ablation areas appear on the carbon brush, with the most severe ablation occurring at the center. This suggests that the concentration of current at the positive terminal leads to a higher energy density in the center region, causing more severe ablation. When the carbon brush is connected to the negative electrode, as shown in

Figure 14e, the ablation is more severe than at 10 V, indicating that the discharge effect of the negative electrode becomes more significant at higher voltages.

Figure 14c shows the ablation of the positive carbon brush at 30 V. With further voltage increase, the depth and area of the ablation pits enlarge significantly, even leading to the phenomenon of the carbon brush being shattered by electric sparks, with almost no intact surface remaining. When the carbon brush is connected to the negative terminal, the entire carbon brush experiences severe ablation, as shown in

Figure 14f. This contrasts with the concentrated discharge pattern at the positive terminal, while the discharge at the negative terminal exhibits a more scattered characteristic. Overall, voltage and polarity have a significant impact on the ablation pattern of the carbon brushes, with more centralized ablation at the positive connection and more extensive marginal ablation at the negative connection.

In exploring the causes of the temperature variations and ablation conditions at the positive and negative electrodes in the brush/ring system, an operating parameter of 200 r/min and 30 V was chosen to observe its effect on arc characteristics and temperature distribution. Under this operating condition,

Figure 15a shows the sparking condition of the positive electrode in the air gap operating mode. It is observed that the positive electrode spark is concentrated and blue, indicating a high operating temperature, likely due to the intensity and energy concentration of the spark. Blue sparks are typically associated with high temperatures, suggesting that the positive electrode reaches a higher temperature. In contrast,

Figure 15b shows the operation of the negative electrode. Despite the larger size of the negative electrode sparks, their dispersion is significant, indicating a broader distribution of spark energy. This dispersion suggests that the surface temperature of the negative electrode is lower, allowing for more effective heat dissipation.

By comparing the spark characteristics of the positive and negative electrodes, the temperature change mechanism of the two can be analyzed, which is corresponding to the above conclusion. The positive electrode, due to its concentrated spark and higher current density, leads to an increase in temperature, so the ablation is mainly concentrated in the middle part, showing flake ablation; while the negative electrode, due to the dispersal of spark and relatively low current density, maintains a lower temperature, the carbon brushes are ablated at the edge position, and the ring surface is pitted with pitting ablation craters.

Figure 16 illustrates the cause of the phenomenon described above. When the carbon brush is connected to the negative terminal, the carbon brush emits electrons to the positive ring specimen. The gas particles formed in the high-temperature environment are drawn toward the ring under the arc force. The high-speed rotation of the ring imparts tangential velocity to the gas particles, and the centrifugal force causes them to be ejected. The trajectory of this ejection forms the observed streamlines. At the same time, the high-temperature gas particles rapidly cool upon contact with the surrounding air, causing them to burst and generate a spark. This results in spark discharge along the tangential direction of rotation, while the ablation location on the ring surface appears black, indicating the attachment of carbon powder, as shown in

Figure 16a.When the carbon brushes are connected to the positive terminal, the ring surface emits electrons to the carbon brushes, causing the breakdown of the gap gas and the formation of a current. Since the area of the ring specimen that emits electrons is much larger than the area of the carbon brush specimen that receives electrons, and the carbon brush remains relatively stationary, the arc force pushes the discharge particles toward the ring specimen continuously. These particles accumulate at the contact point's gap, generating a strong high-temperature arc discharge, as shown in

Figure 16b.