1. Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a condition defined by episodes in which the upper airway partially (hypopnea) or completely (apnea) collapses [

1]. These breathing disruptions cause intermittent disturbances in blood gases, along with periods of increased sympathetic nervous system activity [

2].

The severity of OSA is classified based on the Apnea-Hypopnea Index (AHI) as follows: mild (AHI = 5–14), moderate (AHI = 15–29), and severe (AHI ≥ 30). The prevalence of OSA in the general adult population in Europe is estimated to be around 44%, with approximately 23% of individuals affected by moderate to severe OSA (AHI ≥ 15) [

3]. Loud snoring, unrefreshing sleep, excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS), fatigue, and observed apneas are the most commonly reported symptoms in patients with OSA. In addition, symptoms such as gastroesophageal reflux, nocturia, and chronic morning headaches are more frequently seen in OSA patients compared to the general population [

4]. The disorder is associated with a wide range of metabolic disturbances and an increased risk of both all-cause mortality and cardiovascular mortality [

5]. Intermittent hypoxia during sleep is the primary pathophysiological mechanism underlying the development of various diseases in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). This repeated cycle of oxygen desaturation and reoxygenation during sleep plays a crucial role in the onset and progression of comorbid conditions associated with OSA [

6]. Among other things, systemic inflammation and its effects are crucial aspects in patients with OSA, while intermittent hypoxia also induces the activation of inflammatory cells and the release of inflammatory mediators [

7]. One such mediator is Galectin-3, a chimera-type member of the galectin family, which has emerged as a key player in cardiac inflammation and vascular processes [

8].

Galectins are a family of widely expressed β-galactoside-binding lectins that play a key role in modulating both "cell-to-cell" and "cell-to-matrix" interactions across all organisms. They are categorized into three subgroups based on the number of carbohydrate recognition domains (CRDs) they contain and their functional properties: proto-type galectins (e.g., galectin-1, -2, -5, -7, -10, -11, -13, -14, and -15), tandem-repeat galectins (e.g., galectin-4, -6, -8, -9, and -12) and chimera-type galectin (e.g., galectin-3) [

9]. Galectin-3, as focus of this paper, plays a key role in inflammation and fibrosis across a range of diseases, affecting vital organs such as the heart, liver, kidneys, lungs, and brain. The primary cell types involved in Galectin-3-driven disease processes include myofibroblast, epithelial cells, endothelial cells and macrophages [

10]. Galectin-3 exerts its effects by modulating various cellular compartments. It amplifies cytokine production, immune cell activation, and fibrosis cascades in a hierarchical manner, thereby influencing a broad spectrum of cardiovascular disorders [

11]. Also, Galectin-3 is extensively expressed in lung tissues, including bronchial and alveolae epithelial cells, the pulmonary vasculature and immune cells such as alveolar macrophage. It has been shown to be significantly upregulated in various types of pneumonia, including bacterial, viral and fungal pneumonia, also in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and COPD exacerbations. It is suggested to play a crucial role as a key regulator of the inflammatory response in these conditions [

12].

In many studies, Galectin-3 is described as a novel prognostic biomarker with strong predictive value for cardiovascular mortality and hospital re-admission in heart failure (HF), conditions that are prevalent in patients with OSA [

13].

There are still insufficient studies on the connection between galectin-3 and OSA, but some findings suggest elevated galectin-3 levels in women with OSA [

14]. The present study aims to investigate the correlation between galectin-3 values and the severity of OSA, as well as the correlation with other important laboratory and clinical parameters.

2. Materials and Methods

A total of 191 participant from University Clinical Hospital Center Bezanijska Kosa, Belgrade, Serbia, between January 2023, and May 2024. was included in the analyses. The examinations were conducted in the morning following an overnight fast. The assessment included a review of medical and medication history, anthropometric measurements, glucose levels, and hemoglobin A1c. Blood pressure was measured upon hospital admission after a 5-minute sitting rest using an automated device. Hypertension was defined as a history of high blood pressure, the use of antihypertensive medications, or a blood pressure reading exceeding 140/90 mmHg. All participants underwent an overnight, in hospital sleep apnea evaluation. The sleep study was performed using the Polypro H2 series, that provides a validated estimate of the Apnea Hypopnea Index (AHI) using information from finger pulse oximetry, chest movement, snoring and body position were also recorded. The severity of sleep apnea was defined by using conventional clinical categories: none (AHI≤5 apnea-hypopnea events per hour), mild (AHI >5 to ≤15 apnea-hypopnea events per hour), moderate (AHI >15 to ≤30 apnea/hypopnea events per hour), and severe (AHI>30 apnea-hypopnea events per hour). Oxygen desaturation index (ODI) was also recorded. The ODI is the number of oxygen desaturation events (4% minimum desaturation) per estimate hour of sleep.

Biomarkers were measured at the University Clinical Hospital Center Bezanijska Kosa central laboratory. Galectin-3 was measured using a chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay on an Alinity instrument (Abbott, Abbott Park, IL) in EDTA-plasma. The Alinity galectin-3 assay has a limit of detection of 1.1 ng/mL and a limit of quantitation of 4.0 ng/mL. Inter-assay coefficients of variation were 5.2%, 3.3%, and 2.3% at mean galectin-3 levels of 8.8 ng/mL, 19.2 ng/mL and 72.0 ng/ml, respectively.

Additionally, we measured high-sensitivity troponin-T (hsTnT), a biomarker of myocardial injury, as well as N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), which indicates hemodynamic stress and neurohormonal activation. C-reactive protein (CRP), a marker of inflammatory processes, was also assessed. Arterial blood gas analysis and spirometry were conducted for all patients.

2.1. Statistical Analysis

Numerical data were presented as mean with 95% confidence interval, or median with 25th and 75th percentile. Categorical variables were summarized by absolute numbers with percentages. Baseline characteristics of the study population were organized by categorizing individuals according to the severity of their sleep apnea. Correlations between numerical variables and galectin-3 were assessed by the Pearson or Spearman correlation coefficient. Univariate and multivariate linear regression models were used to assess predictors of galectin-3 values. In all analyses, the significance level was set at 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS statistical software (SPSS for Windows, release 25.0, SPSS, Chicago, IL).

2.2. Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Medical Center Bezanijska Kosa (protocol number 41/2024).

3. Results

A total of 191 patient, with mean age of 56.2 years, and mostly male (68.9%) was included in the study. Of comorbidities, two thirds of patients had hypertension (66.1%), 46.8% had hyperlipoproteinemia, and 21.1% had diabetes mellitus. Demographic data and comorbidities in the study population and their correlation with galectin-3 were presented in

Table 1.

In

Table 2, arterial gas analysis parameters of the study population and their correlation with galectin-3 were presented. Positive correlation was found between lactate and galectin-3 values, where higher values od lactate were associated with higher values of galectin-3 (r=0.203; p=0.011). No significant correlation was observed between other examined arterial gas analysis parameters and galectin-3 (p>0.05).

Clinical, lipids and inflammation parameters of the study population and their correlation with galectin-3 are presented in

Table 3. Positive correlation was found between galectin-3 values and neutrophils (r=0.198; p=0.011), urea (r=0.554; p<0.001), creatinine (r=0.399; p<0.001), LDH (r=0.159; p=0.042), troponine (rho=0.303; p<0.001), NTproBNP (rho=0.423; p<0.001), HbA1c (r=0.247; p=0.002), TSH (rho=0.180; p=0.021), fibrinogen (r=0.195; p=0.015), and microalbumine/Cr ratio (rho=0.179; p=0.025). Significant negative correlation was observed between galectin-3 values and cholesterol values (r=-0.229; p=0.003), LDL (r=-0.225; p=0.004), nonHDL (r=-0.252; p=0.002) and albumine values (r=-0.209; p=0.007).

In

Table 4, respiratory parameters of the study population and their correlation with galectin-3 are presented. Significant negative correlations between FVC, FEV1 and galectin-3 values were found, where higher values of galectin-3 were associated with lower values of FVC and FEV1 (p=0.020 and p=0.011, respectively). Significant positive correlation was found between galectin-3 values and ODI (rho=0.016; p=0.016).

In

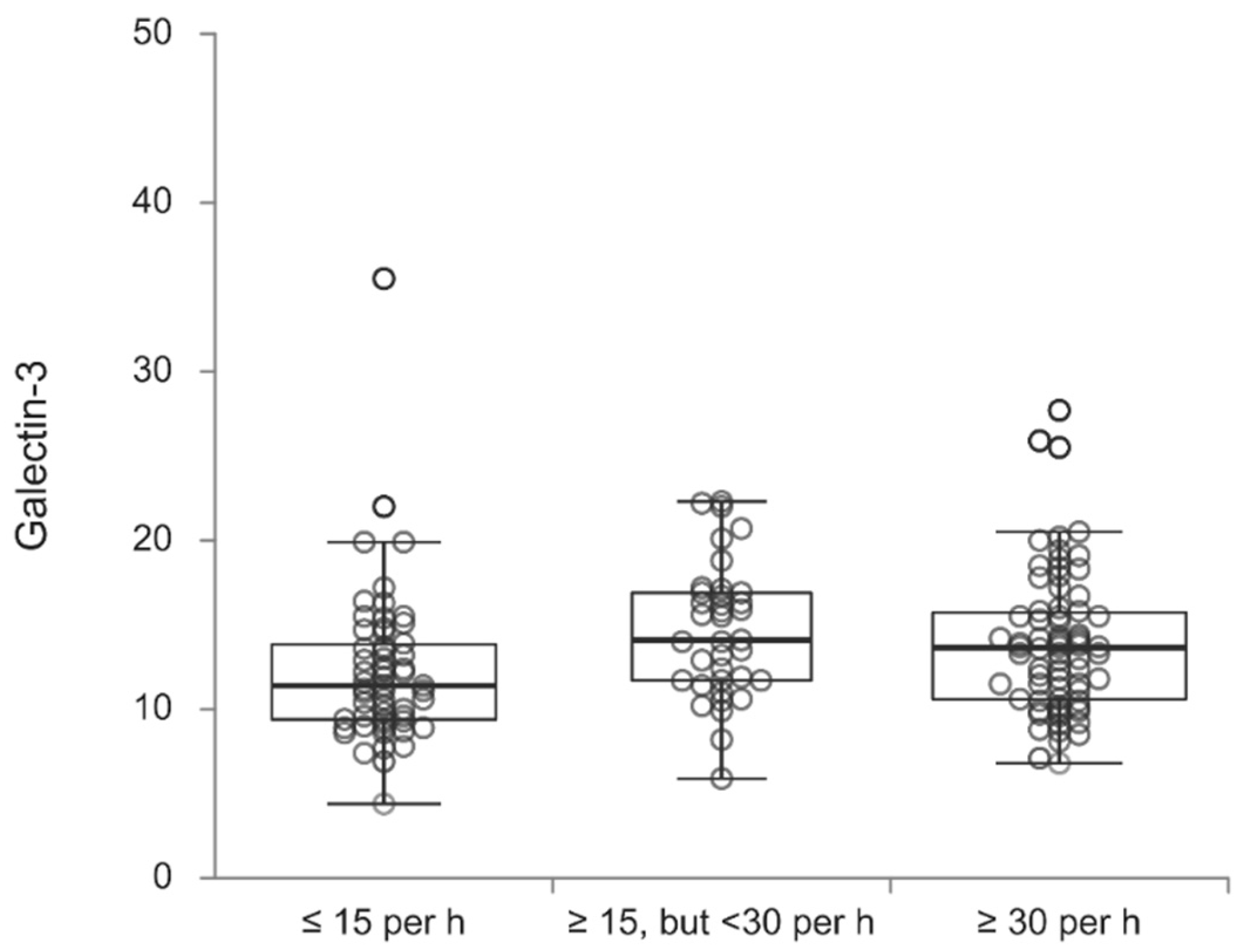

Table 5, galectin-3 values according to the OSA severity are presented. Galectin-3 values significantly differed according to the examined groups (p=0.038), where patients who had an AHI of less than fifteen events per hour more often had lower values of galectin-3 in contrast to patients who had AHI of at least 15 events per hour, but fewer than 30 (p=0.019) and an AHI of at least 30 events per hour (p=0.046) (

Table 5,

Figure 1).

In

Table 6, univariate linear regression analysis with galectin-3 as dependent variable is presented. Out of demographic data and comorbidities of the study population, significant predictors of galectin-3 were: older age (p<0.001), waist circumference (p=0.003), BMI (p=0.015), smoking (p=0.032), presence of hypertension (p<0.001), diabetes mellitus (p=0.005), hypoventilation syndrome (p<0.001), coronary disease (p<0.001) and cardiomyopathy (p<0.001). Higher values of lactate (p=0.011), neutrophils (p=0.011), urea (p<0.001), creatinine (p<0.001), direct bilirubin (p=0.023), LDH (p=0.042), GGT (p=0.012), troponine (p=0.032), NTproBNP (p<0.001), HbA1c (p=0.002) and fibrinogen (p=0.015), as well as lower values of cholesterol (p=0.003), albumine (p=0.007), LDL (p=0.004), and nonLDL (p=0.002) were significant predictors of higher values of galectin-3. Out of respiratory parameters of the study population, significant predictors of higher values of galectin-3 were lower FVC (p=0.020) and FEV1 (p=0.011).

Multivariate linear regression analysis with galectin-3 as dependent variable is presented in

Table 7. Significant independant predictors of higher galectin-3 values were: older age (p<0.001), presence of coronary disease (p<0.001), and hypoventilation syndrome (p=0.025), higher BMI (p=0.034), NTproBNP (p<0.001), lactate (p=0.005), creatinine (p=0.009), lower LDL (p=0.023) and lower FEV1 (p=0.011).

4. Discussion

In the present study, where we assessed the role of galectin-3 in predicting the severity of OSA, galectin-3 levels were significantly elevated in patients with severe obstructive sleep apnea. Systemic inflammation and its impact are critical factors in OSA patients, as intermittent hypoxia triggers the activation of inflammatory cells and the release of inflammatory mediators [

7]. Furthermore, galectin-3 plays a key role in inflammation and fibrosis across various diseases, affecting vital organs such as the heart, lungs, brain, liver and kidneys.

Among the demographic data and comorbidities of the study population, significant predictors included older age, waist circumference, body mass index (BMI), smoking, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hypoventilation syndrome, coronary artery disease, and cardiomyopathy.

A major finding in our study was the strong association between elevated galectin-3 levels and traditional metabolic biomarkers. This result supports existing literature that highlights galectin-3's important role in the pathophysiology of cardiometabolic diseases [

15]. Galectin-3 was found to be positively correlated with neutrophil count, urea, creatinine, troponin, NT-proBNP, LDH, HbA1c, TSH, fibrinogen, and the microalbumin/creatinine ratio.

Tan et al. [

16] reported that diabetic patients with complications, who had significantly poorer glycemic control (with an HbA1c of 9.45 ± 2.31% as a reference), exhibited markedly higher serum galectin-3 levels compared to diabetic patients without complications (P < 0.001). Similarly, studies by Weigert et al. [

17], Jin Qi-hui et al. [

18], and Hodeib et al. [

19] also found a positive correlation between plasma galectin-3 levels and HbA1c levels.

Galectin-3 enhances the adhesion of human neutrophils [20, 21]. Furthermore, in an in vivo mouse model of streptococcal pneumonia, neutrophil extravasation was closely linked to the accumulation of Galectin-3 in the alveolar space, a process that occurred independently of β2-integrin [

21], thus affects the global respiratory function.

In our study, a negative correlation was found between galectin-3 levels and both FVC and FEV1, confirming that galectin-3 levels could be higher during exacerbations of COPD and asthma, which are characterized by lower values of FEV1 and FVC. Two studies have shown that galectin-3 levels are elevated in both blood and lung tissues of COPD patients [22, 23]. Consistent with these findings, it is suggested that galectin-3 may serve as a valuable marker for the early detection of exacerbations [

24]. Aside from OSA, Galectin-3 is involved in various crucial mechanisms of asthma pathophysiology, such as the allergic response, eosinophil activation, and non-Th2 inflammation. As a result, galectin-3 holds potential as a valuable biomarker for diagnosing and monitoring asthma over time [

25].

NT-proBNP, released by cardiomyocytes in response to ventricular strain, is a marker of right ventricular dysfunction [

24]. When combined with BNP, galectin-3 improves predictive accuracy in patients discharged after an acute decompensated heart failure episode, offering better prognostic value than BNP alone [

26]. In our study, we found a significant positive correlation between galectin-3 and NT-proBNP levels. Increased galectin-3 levels may be associated with higher pulmonary vascular resistance due to hypoxia, oxidative stress, and both systemic and pulmonary inflammation.

Berber NK et al. reported a negative correlation between serum galectin-3 levels and PaO2 levels [

24]. In our study, we observed a positive correlation between lactate and galectin-3 levels, but no significant correlation was found between galectin-3 and other examined arterial blood gas parameters.

Albumin, an acute-phase negative protein, also has antioxidant properties. During the acute-phase response, circulating albumin levels generally decrease [

27]. In line with this, our study found a negative correlation between galectin-3 levels and albumin levels. This suggests that an increased systemic inflammatory response and oxidative stress may contribute to elevated galectin-3 concentrations and reduced albumin levels in OSA patients.

The repetitive cycles of hypoxia and reoxygenation during sleep in OSA contribute to oxidative stress, driven by increased production of reactive oxygen species, angiogenesis, and enhanced sympathetic activation [

28]. Galectin-3 has been identified as a critical regulator of oxidative stress, and its inhibition has been shown to restore the antioxidant peroxiredoxin-4, thereby alleviating oxidative stress [

29].

However, research on the role of galectin-3 in obstructive sleep apnea is still insufficient. Future studies will shed light on the importance of this biomarker for the prognosis of patients with OSA.

Although this is a single-center study, it is practically the first study to demonstrate a correlation between the severity of OSA and the level of galectin-3, along with its correlation with other clinical and laboratory. Further research is needed to evaluate the usefulness of galectin-3 as a parameter in monitoring patients after the initiation of therapy, as well as to analyze its association with outcomes such as hospitalization rates, cardiovascular complications, and mortality.

5. Conclusions

Considering that galectin-3 is linked to the severity of OSA and plays a crucial role in inflammation induced by intermittent hypoxia in OSA, further screening and interventions targeting galectin-3 could aid in preventing inflammatory diseases related to sleep disturbances.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B. (Milica Brajkovic), M.Z.; methodology, M.B. (Milica Brajkovic), M.Z., V.P.; software, N.M., N.R; validation, M.B. (Marija Brankovic), N.N., A.S.; formal analysis, N.M. and N.R.; investigation, S.N., V.P., B.M.; resources, M.S., S.P., B.M.; data curation, S.N. and V.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B. (Milica Brajkovic), S.N., V.P.; writing—review and editing, M.Z., V.P.; visualization, N.M. and N.R.; supervision, M.Z.; project administration, M.Z. and V.P.; funding acquisition, M.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Faculty of Medicine, University of Belgrade, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia (number 200110).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University Hospital Medical Center Bezanijska Kosa (protocol number 41/2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (M.B.) upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Slowik JM, Sankari A, Collen JF. Obstructive Sleep Apnea. [Updated 2024 Mar 21]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459252/.

- Eckert DJ, Malhotra A. Pathophysiology of adult obstructive sleep apnea. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5(2):144-53. [CrossRef]

- 3. Polecka A, Olszewska N, Danielski Ł, Olszewska E. Association between Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Heart Failure in Adults-A Systematic Review. J Clin Med. 2023;12(19):6139. [CrossRef]

- Peker Y, Akdeniz B, Altay S, Balcan B, Başaran Ö, Baysal E, Çelik A, Dursunoğlu D, Dursunoğlu N, Fırat S, Gündüz Gürkan C, Öztürk Ö, Taşbakan MS, Aytekin V. Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Cardiovascular Disease: Where Do We Stand? Anatol J Cardiol. 2023;27(7):375-389. [CrossRef]

- Popadic V, Brajkovic M, Klasnja S, Milic N, Rajovic N, Lisulov DP, Divac A, Ivankovic T, Manojlovic A, Nikolic N, Memon L, Brankovic M, Popovic M, Sekulic A, Macut JB, Markovic O, Djurasevic S, Stojkovic M, Todorovic Z, Zdravkovic M. Correlation of Dyslipidemia and Inflammation With Obstructive Sleep Apnea Severity. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:897279. [CrossRef]

- Tuleta I, França CN, Wenzel D, Fleischmann B, Nickenig G, Werner N, Skowasch D. Hypoxia-induced endothelial dysfunction in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice; effects of infliximab and L-glutathione. Atherosclerosis. 2014;236(2):400-10. [CrossRef]

- Unnikrishnan D, Jun J, Polotsky V. Inflammation in sleep apnea: an update. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2015;16(1):25-34. [CrossRef]

- Seropian IM, El-Diasty M, El-Sherbini AH, González GE, Rabinovich GA. Central role of Galectin-3 at the cross-roads of cardiac inflammation and fibrosis: Implications for heart failure and transplantation. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2024:S1359-6101(24)00081-9. [CrossRef]

- Hara A, Niwa M, Noguchi K, Kanayama T, Niwa A, Matsuo M, Hatano Y, Tomita H. Galectin-3 as a Next-Generation Biomarker for Detecting Early Stage of Various Diseases. Biomolecules. 2020;10(3):389. [CrossRef]

- Bouffette S, Botez I, De Ceuninck F. Targeting galectin-3 in inflammatory and fibrotic diseases. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2023;44(8):519-531. [CrossRef]

- Seropian IM, El-Diasty M, El-Sherbini AH, González GE, Rabinovich GA. Central role of Galectin-3 at the cross-roads of cardiac inflammation and fibrosis: Implications for heart failure and transplantation. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2024:S1359-6101(24)00081-9. [CrossRef]

- Jia Q, Yang Y, Yao S, Chen X, Hu Z. Emerging Roles of Galectin-3 in Pulmonary Diseases. Lung. 2024;202(4):385-403. [CrossRef]

- Amin HZ, Amin LZ, Wijaya IP. Galectin-3: a novel biomarker for the prognosis of heart failure. Clujul Med. 2017;90(2):129-132. [CrossRef]

- Singh M, Hanis CL, Redline S, Ballantyne CM, Hamzeh I, Aguilar D. Sleep apnea and galectin-3: possible sex-specific relationship. Sleep Breath. 2019;23(4):1107-1114. [CrossRef]

- Liu L, Zhen J, Liu S, Ren L, Zhao G, Liang J, Xu A, Li C, Wu J, Cheung BMY. Association between sleep patterns and galectin-3 in a Chinese community population. BMC Public Health. 2024;24(1):1323. [CrossRef]

- Tan KCB, Cheung CL, Lee ACH, Lam JKY, Wong Y, Shiu SWM. Galectin-3 is independently associated with progression of nephropathy in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2018;61:1212–9. [CrossRef]

- Weigert J, Neumeier M, Wanninger J, Bauer S, Farkas S, Scherer MN, et al. Serum galectin-3 is elevated in obesity and negatively correlates with glycosylated hemoglobin in type 2 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:1404–11. [CrossRef]

- Jin QH, Lou YF, Li TL, Chen HH, Liu Q, He XJ. Serum galectin-3: a risk factor for vascular complications in type 2 diabetes mellitus Chin Med J (Engl). 2013;126(11):2109-15.

- Hodeib H, Hagras MM, Abdelhai D, Watany MM, Selim A, Tawfik MA, et al. Galectin-3 as a prognostic biomarker for diabetic nephropathy. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes. 2019;12:325–31. [CrossRef]

- Kuwabara I, Liu FT: Galectin-3 potiče prianjanje ljudskih neutrofila na laminin. J Immunol. 1996, 156: 3939-3944.

- Sato S, Ouellet N, Pelletier I, Simard M, Rancourt A, Bergeron MG: Uloga galektina-3 kao adhezijske molekule za ekstravazaciju neutrofila tijekom streptokokne pneumonije. J Immunol. 2002, 168: 1813-1822.

- Pilette, C.; Colinet, B.; Kiss, R.; Andre, S.; Kaltner, H.; Gabius, H.-J.; Delos, M.; Vaerman, J.-P.; Decramer, M.; Sibille, Y. Increased galectin-3 expression and intra-epithelial neutrophils in small airways in severe COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 2007, 29, 914–922.

- Feng, W.; Wu, X.; Li, S.; Zhai, C.; Wang, J.; Shi, W.; Li, M. Association of Serum Galectin-3 with the Acute Exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Med. Sci. Monit. 2017, 23, 4612–4618. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Berber NK, Atlı S, Geçkil AA, Erdem M, Kıran TR, Otlu Ö, İn E. Diagnostic Value of Galectin-3 in Exacerbations of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. Medicina. 2024; 60(4):529.

- 25. Portacci A, Iorillo I, Maselli L, Amendolara M, Quaranta VN, Dragonieri S, Carpagnano GE. The Role of Galectins in Asthma Pathophysiology: A Comprehensive Review. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2024; 46(5):4271-4285.

- Feola M, Testa M, Leto L, Cardone M, Sola M, Rosso GL. Role of galectin-3 and plasma B type-natriuretic peptide in predicting prognosis in discharged chronic heart failure patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(26):e4014. [CrossRef]

- Gabay, C.; Kushner, I. Acute-phase proteins and other systemic responses to inflammation. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 340, 448–454. [Google Scholar]

- Dewan NA, Nieto FJ, Somers VK. Intermittent hypoxemia and OSA: implications for comorbidities. Chest. 2015;147:266–74.

- Ibarrola J, Arrieta V, Sadaba R, Martinez-Martinez E, Garcia-Pena A, Alvarez V, et al. Galectin-3 down-regulates antioxidant peroxiredoxin-4 in human cardiac fibroblasts: a new pathway to induce cardiac damage. Clin Sc.(Lond). 2018;132:1471–85.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).