Submitted:

14 November 2024

Posted:

18 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

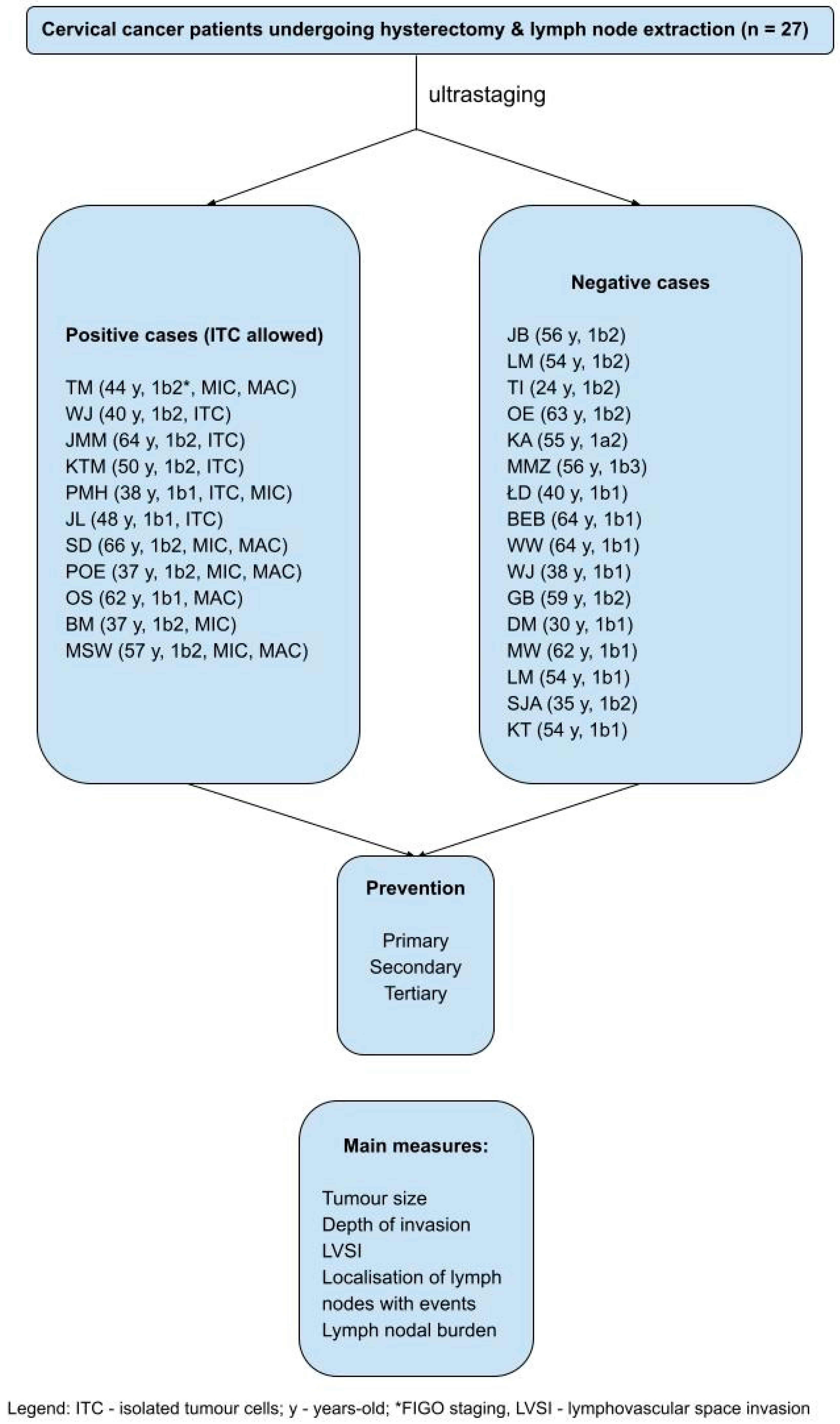

Methods

Results

General Results

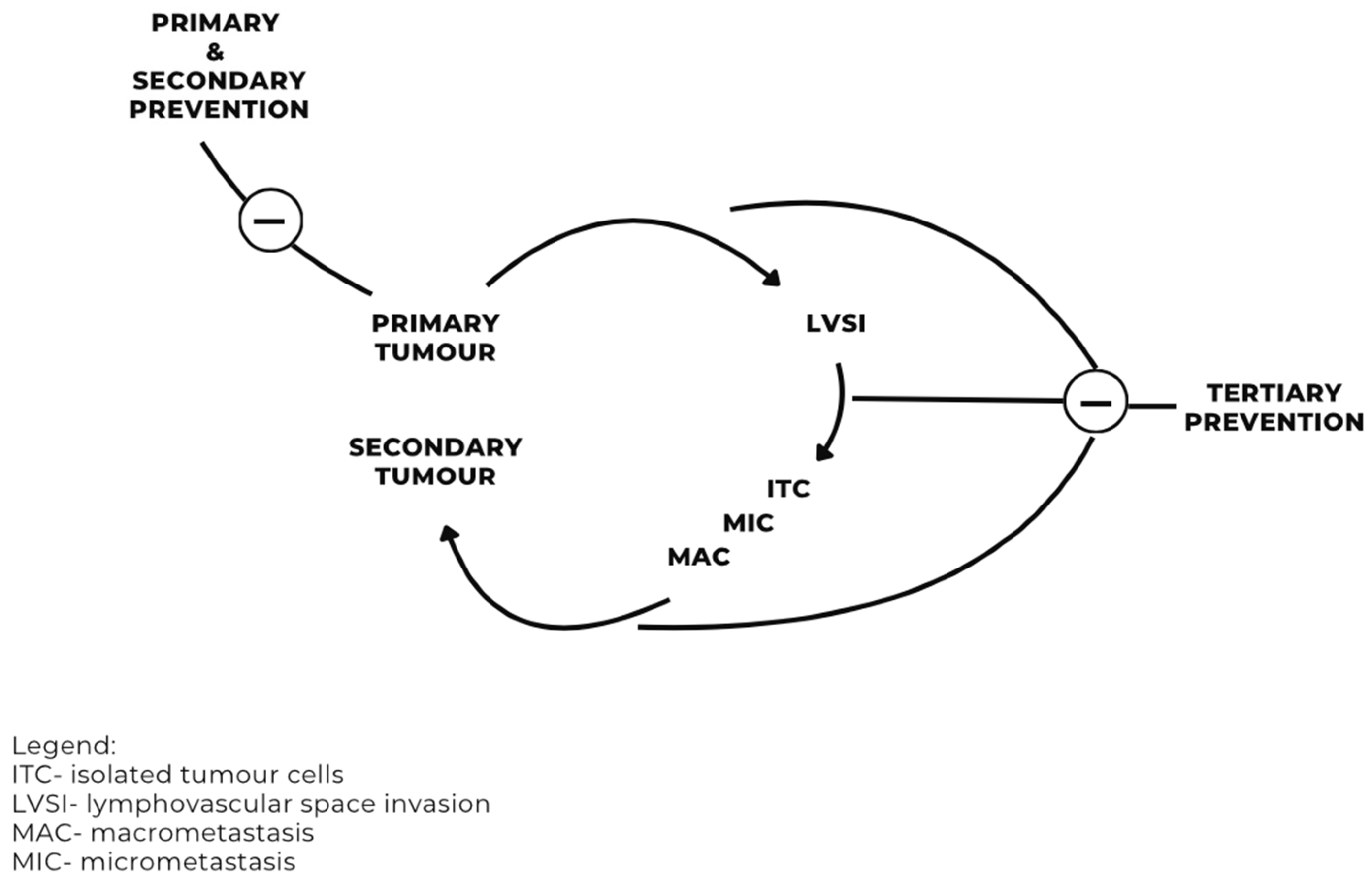

Prevention

Lymphatic Tracts

Discussion

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

Recommendation for Prevention

Author Contributions

Funding

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Consent for Publication

Availability of Data and Materials

Acknowledgments

Competing Interests

List of Abbreviations

| AJCC | American Joint Committee on Cancer |

| ARRM | Annual Recurrence Risk Model |

| AUB | Abnormal uterine bleeding |

| ESGO | European Society of Gynaecological Oncology |

| ESMO | European Society of Medical Oncology |

| ITCs | Isolated tumor cells |

| LND | Lymphadenectomy |

| LNE | Lymph node events |

| LVSI | Lymphovascular space invasion |

| MAC | Macrometastasis |

| MIC | Micrometastasis |

| NCCN | National Comprehensive Cancer Network |

| SLN | Sentinel lymph node |

| SLND | Sentinel lymph node dissection |

| STROBE | STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology |

| TNM | Tumor-Node-Metastasis (system) |

| nSLN | Non-sentinel lymph node |

References

- Van Trappen, P.O.; Pepper, M.S. Lymphatic dissemination of tumour cells and the formation of micrometastases. Lancet Oncol. 2002, 3, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abati, A.; Liotta, L.A. Looking forward in diagnostic pathology: the molecular superhighway. Cancer 1996, 78, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benedetti-Panici, P.; Maneschi, F.; D’Andrea, G.; Cutillo, G.; Rabitti, C.; Congiu, M.; Coronetta, F.; Capelli, A. Early cervical carcinoma: the natural history of lymph node involvement redefined on the basis of thorough parametrectomy and giant section study. Cancer 2000, 88, 2267–2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śniadecki, M.; Poniewierza, P.; Jaworek, P.; Szymańczyk, A.; Andersson, G.; Stasiak, M.; Brzeziński, M.; Bońkowska, M.; Krajewska, M.; Konarzewska, J.; Klasa-Mazurkiewicz, D.; Guzik, P.; Wydra, D.G. Thousands of Women’s Lives Depend on the Improvement of Poland’s Cervical Cancer Screening and Prevention Education as Well as Better Networking Strategies Amongst Cervical Cancer Facilities. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022, 12(8), 1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morice, P.; Scambia, G.; Abu-Rustum, N.R.; Acien, M.; Arena, A.; Brucker, S.; Cheong, Y.; Collinet, P.; Fanfani, F.; Filippi, F.; Eriksson, A.G.Z.; Gouy, S.; Harter, P.; Matias-Guiu, X.; Pados, G.; Pakiz, M.; Querleu, D.; Rodolakis, A.; Rousset-Jablonski, C.; Stepanyan, A.; Testa, A.C.; Macklon, K.T.; Tsolakidis, D.; De Vos, M.; Planchamp, F.; Grynberg, M. Fertility-sparing treatment and follow-up in patients with cervical cancer, ovarian cancer, and borderline ovarian tumours: guidelines from ESGO, ESHRE, and ESGE. The Lancet Oncology 2024, 25(11), e602–e610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, W. J.; Abu-Rustum, N. R.; Bean, S.; Bradley, K.; Campos, S. M.; Cho, K. R.; Chon, H. S.; Chu, C.; Clark, R.; Cohn, D.; Crispens, M. A.; Damast, S.; Dorigo, O.; Eifel, P. J.; Fisher, C. M.; Frederick, P.; Gaffney, D. K.; Han, E.; Huh, W. K.; Lurain, J. R.; Mariani, A.; Mutch, D.; Nagel, C.; Nekhlyudov, L.; Fader, A.N.; Remmenga, S.W.; Reynolds, R.K.; Tillmanns, T.; Ueda, S.; Wyse, E.; Yashar, C.M.; McMillian, N.R.; Scavone, J. L. Cervical Cancer, Version 3.2019, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2019, 17(1), 64–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cibula, D.; Dostálek, L.; Jarkovsky, J.; Mom, C. H.; Lopez, A.; Falconer, H.; Scambia, G.; Ayhan, A.; Kim, S. H.; Isla Ortiz, D.; Klat, J.; Obermair, A.; Di Martino, G.; Pareja, R.; Manchanda, R.; Kosťun, J.; Dos Reis, R.; Meydanli, M. M.; Odetto, D.; Laky, R.; Zapardiel, I.; Weinberger, V.; Benešová, K.; Borčinová, M.; Cardenas, F.; Wallin, E.; Pedone Anchora, L.; Akilli, H.; Abu-Rustum, N.R.; Barquet-Muñoz, S.A.; Javůrková, V.; Fischerová, D.; van Lonkhuijzen, L. R. C. W. Post-recurrence survival in patients with cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2022, 164(2), 362–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olawaiye, A.B.; Baker, T.P.; Washington, M.K.; Mutch, D.G. The new (Version 9) American Joint Committee on Cancer tumor, node, metastasis staging for cervical cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021, 71(4), 287–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dostálek, L.; Benešová, K.; Klát, J.; Kim, S. H.; Falconer, H.; Kostun, J.; Dos Reis, R.; Zapardiel, I.; Landoni, F.; Ortiz, D. I.; van Lonkhuijzen, L. R. C. W.; Lopez, A.; Odetto, D.; Borčinová, M.; Jarkovsky, J.; Salehi, S.; Němejcová, K.; Bajsová, S.; Park, K. J.; Javůrková, V.; Abu-Rustum, N.R.; Dundr, P.; Cibula, D. Stratification of lymph node metastases as macrometastases, micrometastases, or isolated tumor cells has no clinical implication in patients with cervical cancer: Subgroup analysis of the SCCAN project. Gynecol Oncol. 2023, 168, 151–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derbie, A.; Amare, B.; Misgan, E.; Nibret, E.; Maier, M.; Woldeamanuel, Y.; Abebe, T. Histopathological profile of cervical punch biopsies and risk factors associated with high-grade cervical precancerous lesions and cancer in northwest Ethiopia. PLoS One 2022, 17(9), e0274466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinohara, S.; Ochi, T.; Miyazaki, T.; Fujii, T.; Kawamura, M.; Mochizuki, T.; Ito, M. Histopathological prognostic factors in patients with cervical cancer treated with radical hysterectomy and postoperative radiotherapy. Int J Clin Oncol. 2004, 9(6), 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sniadecki, M.; Wydra, D.G.; Wojtylak, S.; Wycinka, E.; Liro, M.; Sniadecka, N.; Mrozińska, A.; Sawicki, S. The impact of low volume lymph node metastases and stage migration after pathologic ultrastaging of non-sentinel lymph nodes in early-stage cervical cancer: a study of 54 patients with 4.2 years of follow up. Ginekol Pol. 2019, 90, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barranger, E.; Cortez, A.; Commo, F.; Marpeau, O.; Uzan, S.; Darai, E.; Callard, P. Histopathological validation of the sentinel node concept in cervical cancer. Ann Oncol. 2004, 15(6), 870–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D. G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S. J.; Gøtzsche, P. C.; Vandenbroucke, J. P.; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. BMJ. 2007, 335(7624), 806–808, [Published simultaneously in eight journals; https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/strobe/]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sniadecki, M.; Sawicki, S.; Wojtylak, S.; Liro, M.; Wydra, D. Clinical feasibility and diagnostic accuracy of detecting micrometastatic lymph node disease in sentinel and non-sentinel lymph nodes in cervical cancer: outcomes and implications. Ginekol Pol. 2014, 85(1), 10–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhatla, N.; Berek, J.S.; Cuello Fredes, M.; Denny, L.A.; Grenman, S.; Karunaratne, K.; Kehoe, S. T.; Konishi, I.; Olawaiye, A. B.; Prat, J.; Sankaranarayanan, R.; Brierley, J.; Mutch, D.; Querleu, D.; Cibula, D.; Quinn, M.; Botha, H.; Sigurd, L.; Rice, L.; Ryu, H. S.; Ngan, H.; Mäenpää, J.; Andrijono, A.; Purwoto, G.; Maheshwari, A.; Bafna, U.D.; Plante, M.; Natarajan, J. Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the cervix uteri. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2019, 145(1), 129–135, [published correction appears in Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2019, 147(2), 279–280]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pache, B.; Tantari, M.; Guani, B.; Mathevet, P.; Magaud, L.; Lecuru, F.; Balaya, V.; SENTICOL Group. Predictors of Non-Sentinel Lymph Node Metastasis in Patients with Positive Sentinel Lymph Node in Early-Stage Cervical Cancer: A SENTICOL GROUP Study. Cancers (Basel) 2023, 15(19), 4737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tantari, M.; Bogliolo, S.; Morotti, M.; Balaya, V.; Bouttitie, F.; Buenerd, A. Lymph Node Involvement in Early-Stage Cervical Cancer: Is Lymphangiogenesis a Risk Factor? Results from the MICROCOL Study. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14(1), 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lécuru, F.; Mathevet, P.; Querleu, D.; Leblanc, E.; Morice, P.; Daraï, E.; Marret, H.; Magaud, L.; Gillaizeau, F.; Chatellier, G.; Dargent, D. Bilateral negative sentinel nodes accurately predict absence of lymph node metastasis in early cervical cancer: results of the SENTICOL study. J Clin Oncol. 2011, 29(13), 1686–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lührs, O.; Bollino, M.; Ekdahl, L.; Lönnerfors, C.; Geppert, B.; Persson, J. Similar distribution of pelvic sentinel lymph nodes and nodal metastases in cervical and endometrial cancer. A prospective study based on lymphatic anatomy. Gynecol Oncol. 2022, 165(3), 466–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, J.; He, X.; Wang, H.; Dong, W.; Zhang, Y.; Zhao, J.; Willborn, K. C.; Huang, B.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, P. Topographic distribution of lymph node metastasis in patients with stage IB1 cervical cancer: an analysis of 8314 lymph nodes. Radiat Oncol. 2021, 16(1), 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathevet, P.; Guani, B.; Ciobanu, A.; Lamarche, E. M.; Boutitie, F.; Balaya, V.; Lecuru, F. Histopathologic Validation of the Sentinel Node Technique for Early-Stage Cervical Cancer Patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021, 28(7), 3629–3635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śniadecki, M.; Guani, B.; Jaworek, P.; Klasa-Mazurkiewicz, D.; Mahiou, K.; Mosakowska, K.; Buda, A.; Poniewierza, P.; Piątek, O.; Crestani, A.; Stasiak, M.; Balaya, V.; Musielak, O.; Piłat, L.; Maliszewska, K.; Aristei, C.; Guzik, P.; Wojtylak, S.; Liro, M.; Gaillard, T.; Kocian, R.; Gołąbiewska, A.; Chmielewska, Z.; Wydra, D. Tertiary prevention strategies for micrometastatic lymph node cervical cancer: A systematic review and a prototype of an adapted model of care. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2024, 197, 104329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jóźwiak, W. Krótka historia edukacji seksualnej w Polsce. Available online: https://edukacjaseksualna.com/standardy-edukacji-seksualnej-na-swiecie-i-w-polsce/ (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- World Health Organisation. Comprehensive sexuality education. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/comprehensive-sexuality-education (accessed on 9 September 2024).

- Cibula, D.; Dostálek, L.; Jarkovsky, J.; Mom, C.H.; Lopez, A.; Falconer, H.; Fagotti, A.; Ayhan, A.; Kim, S. H.; Isla Ortiz, D.; Klat, J.; Obermair, A.; Landoni, F.; Rodriguez, J.; Manchanda, R.; Kosťun, J.; Dos Reis, R.; Meydanli, M. M.; Odetto, D.; Laky, R.; Zapardiel, I.; Weinberger, V.; Benešová, K.; Borčinová, M.; Pari, D.; Salehi, S.; Bizzarri, N.; Akilli, H.; Abu-Rustum, N.R.; Salcedo-Hernández, R.A.; Javůrková, V.; Sláma, J.; van Lonkhuijzen, L. R. C. W. The annual recurrence risk model for tailored surveillance strategy in patients with cervical cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2021, 158, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kechagias, K. S.; Kalliala, I.; Bowden, S. J.; Athanasiou, A.; Paraskevaidi, M.; Paraskevaidis, E.; Dillner, J.; Nieminen, P.; Strander, B.; Sasieni, P.; Veroniki, A. A.; Kyrgiou, M. Role of human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination on HPV infection and recurrence of HPV related disease after local surgical treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2022, 378, e070135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegde, M.; Naliyadhara, N.; Unnikrishnan, J.; Alqahtani, M.S.; Abbas, M.; Girisa, S.; Sethi, G.; Kunnumakkara, A.B. Nanoparticles in the diagnosis and treatment of cancer metastases: Current and future perspectives. Cancer Lett. 2023, 556, 216066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Creasman, W.T.; Kohler, M.F. Is lymph vascular space involvement an independent prognostic factor in early cervical cancer? Gynecol Oncol. 2004, 92(2), 525–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slama, J.; Dundr, P.; Dusek, L.; Cibula, D. High false negative rate of frozen section examination of sentinel lymph nodes in patients with cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2013, 129(2), 384–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cibula, D.; Abu-Rustum, N.R.; Dusek, L.; Zikán, M.; Zaal, A.; Sevcik, L. Prognostic significance of low volume sentinel lymph node disease in early-stage cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2004, 94(1), 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cibula, D.; Abu-Rustum, N. R.; Dusek, L.; Slama, J.; Zikán, M.; Zaal, A.; Sevcik, L.; Kenter, G.; Querleu, D.; Jach, R.; Bats, A. S.; Dyduch, G.; Graf, P.; Klat, J.; Meijer, C. J.; Mery, E.; Verheijen, R.; Zweemer, R. P. Bilateral ultrastaging of sentinel lymph node in cervical cancer: Lowering the false-negative rate and improving the detection of micrometastasis. Gynecol Oncol. 2012, 127(3), 462–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bats, A.S.; Frati, A.; Mathevet, P.; Orliaguet, I.; Querleu, D.; Zerdoud, S. Contribution of lymphoscintigraphy to intraoperative sentinel lymph node detection in early cervical cancer: Analysis of the prospective multicentre SENTICOL cohort. Gynecol Oncol. 2015, 137(2), 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouldamer, L.; Marret, H.; Acker, O.; Barillot, I.; Body, G. Unusual localizations of sentinel lymph nodes in early stage cervical cancer: a review. Surg Oncol. 2012, 21(3), e153–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathevet, P.; Lécuru, F.; Uzan, C.; Boutitie, F.; Magaud, L.; Guyon, F.; Querleu, D.; Fourchotte, V.; Baron, M.; Bats, A. S.; Senticol 2 group. Sentinel lymph node biopsy and morbidity outcomes in early cervical cancer: Results of a multicentre randomised trial (SENTICOL-2). Eur J Cancer. 2021, 148, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cibula, D.; Dostalek, L.; Hillemanns, P.; Scambia, G.; Jarkovsky, J.; Persson, J.; Raspagliesi, F.; Novak, Z.; Jaeger, A.; Capilna, M. E.; Weinberger, V.; Klat, J.; Schmidt, R. L.; Lopez, A.; Scibilia, G.; Pareja, R.; Kucukmetin, A.; Kreitner, L.; El-Balat, A.; Pereira, G. J. R.; Laufhütte, S.; Isla-Ortiz, D.; Toptas, T.; Gil-Ibanez, B.; Vergote, I.; Runnenbaum, I. Completion of radical hysterectomy does not improve survival of patients with cervical cancer and intraoperatively detected lymph node involvement: ABRAX international retrospective cohort study. Eur J Cancer. 2021, 143, 88–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plante, M.; Kwon, J. S.; Ferguson, S.; Samouëlian, V.; Ferron, G.; Maulard, A.; de Kroon, C.; Van Driel, W.; Tidy, J.; Williamson, K.; Mahner, S.; Kommoss, S.; Goffin, F.; Tamussino, K.; Eyjólfsdóttir, B.; Kim, J. W.; Gleeson, N.; Brotto, L.; Tu, D.; Shepherd, L.E.; CX.5 SHAPE Investigators. Simple versus Radical Hysterectomy in Women with Low-Risk Cervical Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2024, 390(9), 819–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Characteristic | Result |

|---|---|

| Age of a patient (average years) | 49.6 (24 - 66) |

| Primary prevention | No |

| Secondary prevention | Pap smear |

| Tertiary prevention | Follow up |

|

First symptoms attributed to cervical cancer (number of cases per cent) AUB Discharge Mixed No symptoms at all No data |

9 (33.5) 3 (11.0) 3 (11.0) 2 (7.5) 10 (37.0) |

| Time from the first symptoms to admission (average in months) | 1 - 6 (3.8) |

| Tumor size at histopathologic examination (average in millimetres) | 22.4 (6.0 - 55.0) |

|

FIGO stage (2018-) (number of cases) Ib1 Ib2 Ib3 |

11 14 1 |

| Depth of cancer invasion (average in millimetres) | 10.0 (4.0 - 20.0) |

|

Cancer type (number of cases) squamous cell carcinoma adenocarcinoma |

25 2 |

|

Tumor grade (number of cases) 1 2 3 |

2 14 11 |

|

LVSI (number of cases) intratumoral extratumoral intratumoral and extratumoral no |

10 2 2 13 |

|

ITC (number of cases) Per node*^ Per patient# |

12 4 |

|

MIC (number of cases) Per node*^ Per patient# |

24 2 |

|

MAC (number of cases) Per node*^ Per patient# |

30 5 |

| Level of prevention | Main representative | Description | Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | Controlling risk factors | Education on cervical cancer risk factors and HR-HPV vaccines | 0 |

| Secondary | Cytology (Pap smear) | Pap 1 Pap 2 Pap 3 (ASCUS) Pap 4 (HSIL) Pap 5 (CA) No data |

1 3 2 4 2 15 |

| Tertiary | Follow up |

Subgroup with LNE (n1=11) On site Outside the centre Mixed Unknown* Subgroup without LNE (n2=16) On site Outside the centre Mixed Unknown* |

4 5 1 1 4 8 3 1 |

| Characteristic | Lymph nodal status (event-positive vs. -negative) |

|---|---|

| Histological tumor subtype | p=0.31344* (NS) |

| Grade | p=0.19669* (NS) |

| Tumor size | p=0.23763* (NS) |

| Depth of invasion | p=0.310^ (NS) |

| LVSI | p=0.02278* (S) |

|

Patient |

FIGO stage (2018-) |

Maximal lesion type |

Total maximal lymph node burden (mm) |

Minimal lymph node burden (mm |

Maximal lymph node burden (mm) |

Localisation of lymph node events | |||||||

| Right external iliac nodes | Left external iliac nodes | Right obturator | Left obturator | Right common iliac | Left common iliac | Paraaortic | Parametrial | ||||||

| TM | 1b2 | MAC | 18.3 | 0.3 | 7.0 | MAC, MIC | MAC, MIC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | MAC, MIC |

| WJ | 1b2 | ITC | <0.2 | N/A | N/A | 0 | ITC | 0 | ITC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| JMM | 1b2 | ITC | <0.2 | N/A | N/A | ITC | 0 | ITC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| KTM | 1b2 | ITC | <0.2 | N/A | N/A | ITC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PMH | 1b1 | MIC | 2.8 | N/A | 1.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | MIC | 0 | MIC, ITC | 0 | 0 |

| JL | 1b1 | ITC | <0.2 | N/A | N/A | 0 | ITC | 0 | ITC | 0 | ITC | 0 | ITC |

| SD | 1b2 | MAC | 34.0 | 2.0 | 13.0 | MAC, MIC | MAC | MAC, MIC | MAC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| P-OE | 1b2 | MAC | 106.0 | 2.0 | 17.0 | 0 | MAC, MIC | MAC, MIC | MAC | MIC | MAC | 0 | 0 |

| OS | 1b1 | MAC | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 0 | 0 | MAC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| BM | 1b2 | MIC | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | MIC | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| MSW | 1b2 | MAC | 12.5 | 0.3 | 10.0 | MIC | MAC, MIC | 0 | 0 | 0 | MIC | MIC | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).