1. Introduction

Several applications areas, such as remote sensing, satellite communications, radar, and health engineering call for antenna solutions capable of realizing circularly polarized (CP) beams. No need of reciprocal alignment, improved resistance to multipath fading, and capability to easily overcome obstacles on the data link, confer to CP regime an increased appeal. With respect to other modern techniques, based on metasurfaces in transmitting or reflecting mode (see, e.g., [

1,

2,

3,

4]), CP leaky-wave antennas (LWAs), using a single-element structure, offer interesting advantages in terms of compactness, planar geometries, and simple feeding schemes, critical for antennas in integrated complex systems.

LWAs are a class of traveling-wave radiators based on open waveguides. The leaky-wave theory is exploited to design both one-dimensional (1-D) and two-dimensional (2-D) antennas. While for the first category a fundamental direction is set, a radial symmetry of power flow is characteristic for the second one. For both categories, on the elevation plane, the frequency dispersion of the complex propagation wavenumber

is exploited to promptly reconfigure both the pointing angle and the directivity of the far-field beam. This latter condition naturally simplifies the feeding network which may consist in simple, non-directive, dipole-like linearly polarized sources [

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15]. Typical for a vast majority of LWAs, planar geometries and interfaces, can be suitably modified by further deposing metallic, dielectric or metallic-dielectric electrically thin layers, commonly recreating periodic patterns. Due to their ability to manipulate the interacting electromagnetic field, it is common to refer to such structures as to

. Depending on the specific application and desired features within the framework of leaky-wave antennas, the latter can be operated in homogenization regime, with the periodicity of the lattice being a small fraction of the operating wavelength and beyond, where the two dimensions become comparable and space harmonics appear [

8].

Substrate integrated waveguides (SIWs) represent a well-established technology for 1-D LWAs [

16,

17]. In [

18] a scanning CP fan beam is obtained from a SIW based on a T-shaped inter-digital slot unit cell and fed by a simple coaxial cable. A similar idea is exploited in [

19], where a periodically loaded benzene-ring-shaped slot is patterned on a SIW, realizing a wide frequency-driven CP scan from the backward half-plane to the forward one. In particular, the proposed periodic 1-D LWAs offer a potentially feasible way to radiate an elevation-directive CP fan beam while scanning both backward and forward quadrants through the broadside thanks to the open stop-band (OSB) suppression [

8], without being able to reconfigure the fan-shaped radiation pattern over the azimuth plane.

In this respect, Fabry–Perot cavity antennas (FPCAs) [

20], offer a flexible and advantageous solution. As well known [

21], FPCAs can be modeled as 2-D LWAs and are often designed to radiate either a linearly polarized (LP) pencil beam at broadside or an LP scanned (almost omnidirectional) conical beam [

11]. Progress has recently been made in realizing CP beams as well as in beam-shaping techniques.

Independent excitation of both a TM and a TE leaky waves has been proven as an effective technique in [

22]. A way to ensure the two required field modes, consists in employing two distinct sources. A vertical electric dipole (VED) is obtained by the insertion of a coaxial cable through the ground plane to excite a TM leaky wave, whereas the TE counterpart can be excited by an equivalent vertical magnetic dipole (VMD) or, more practically, by a circular array of slots etched in the ground plane [

23,

24]. Considering a resonant cavity bounded by a ground plane and a homogenized partially reflective surface (PRS), the proposed approach leads to a swift polarization customization, easily switching from a radiated linearly polarized field to a circularly polarized one thanks to the antenna biasing system, equalizing the magnitudes of vertical and horizontal far-field components and providing the desired phase shift quadrature [

22]. While preserving high elevation gain thanks to high reflectivity characterizing the PRS [

20,

21], due to symmetry constraints, a broadside radiation null is unavoidable [

11]. The antenna design in [

22] demonstrates the flexibility in obtaining CP beams, once two complementary feeders are provided in the cavity. With the aim of reducing the complexity of the feeding structure, different antenna architectures for producing CP beams were explored, which do not necessarily require complementary feeders.

Linear-to-circular polarization conversion has been investigated through different techniques. A self-polarizing FPCA architecture has been proposed in [

25], employing a nonresonant frequency selective surface (FSS) to induce resonance and a further twisting surface to produce the desired feature of circular polarization. A simple LP feeder is employed to generate resonance inside the cavity, which allows partial power leakage towards a polarizing ground plane, producing the complementary field component. Accurate cavity optimization allows to radiate a pure CP beam at broadside.

Profitable use of PRS has been further investigated to obtain other compact planar geometries devoted to polarization conversion. In [

26,

27] the typical highly reflective PRS is designed as a layered superposition of dielectric substrates and metals. Specifically, in [

27] two separated patches decoupled by a metallic plane are considered in a transmitting-receiving scheme, with the bottom one exhibiting a high reflectivity necessary for high elevation selectivity, and the upper shaped one responsible for polarization conversion.

On the other hand, electronic beam-control methods, as part of beam-shaping, have been proposed in [

28,

29,

30,

31], tuning the dimensions of the design elements and thus the modal features of the supported leaky-wave solutions. A classic strategy to perform electronic beam-steering consists in exploiting the standard array theory. Simple free-space arrays may require a large number of elements to obtain a fine direction tuning, suffering from parasite cross-talk phenomena among elements, grating lobes, and requiring complex feeding systems [

32]. Embedding multiple sources in resonant cavities has been proven effective in [

33,

34], in terms of array thinning, simplification of feeding scheme, and grating lobes mitigation.

In this work, we combine the two different concepts of polarization conversion and electronic array-based beam-steering, designing a novel polarization-conversion meatasurface (PCM) with an increased axial-ratio (AR) elevation stability and an enhanced azimuthal symmetry of the unit cell. The main goal of this study is to design an FPCA able to radiate highly directive CP pencil beams in any desired direction within a certain angular range by exploiting both the leaky-wave frequency scanning behavior and the use of multiple feeders.

This paper is organized as follows. In Sec. II, the theoretical background and the PCM design strategy are presented. The latter is exploited in Sec. III, where the element patterns of an optimized, original unit cell are obtained through computationally efficient full-wave simulations based on the reciprocity theorem. The consequence of embedding multiple sources is then illustrated in Sec. IV, for a few case studies. Final remarks and future perspectives are discussed in Sec. V.

2. Unit-Cell Design and Analysis Strategy

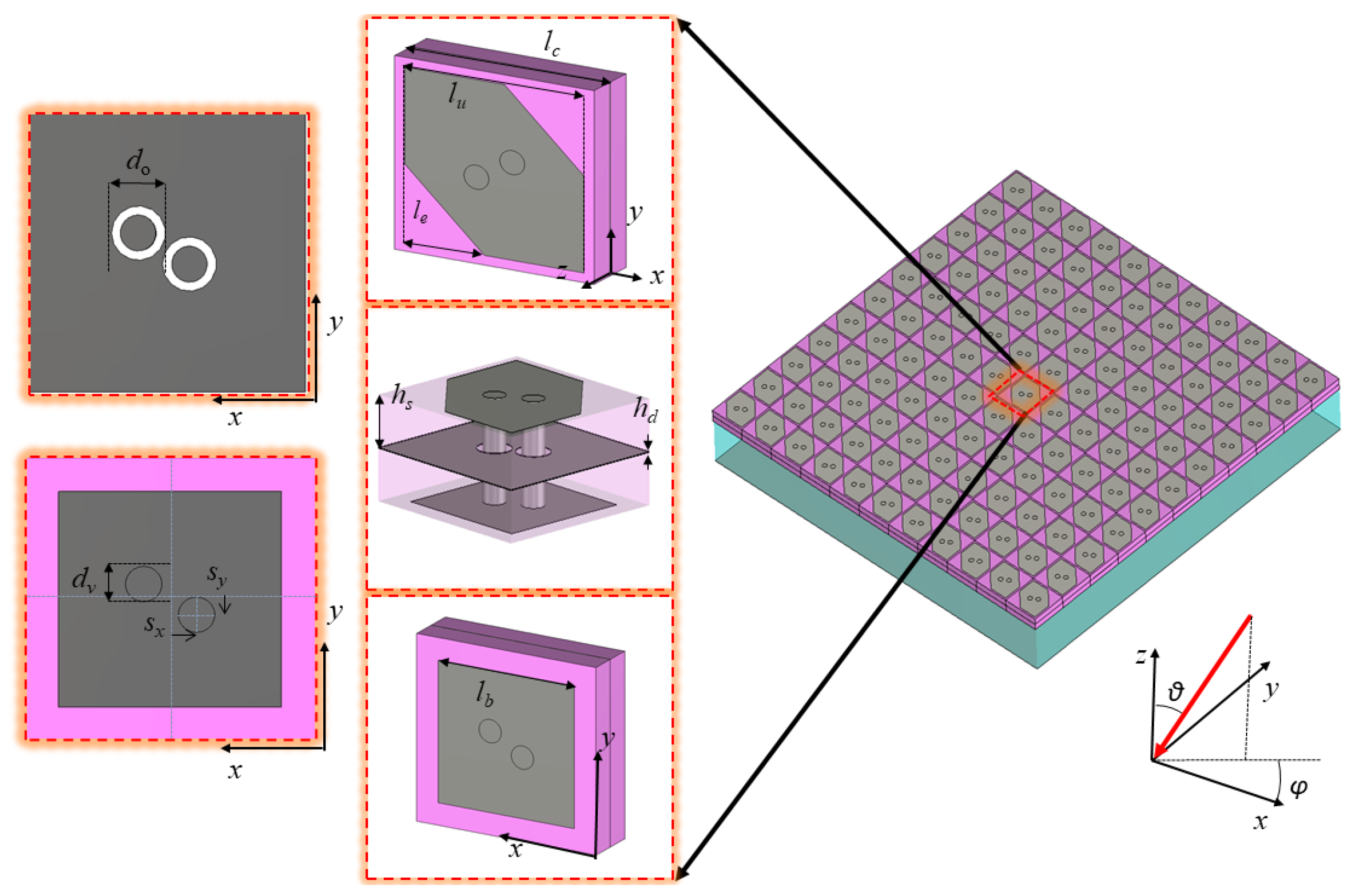

The antenna structure is presented in

Figure 1, as well as a detailed zoom on the PCM unit cell. Three main components should be distinguished: the PCM, the ground plane, and a simple horizontal electric dipole (HED) oriented along the

y axis and placed in the middle of the cavity to have maximum gain [

35]. Here, we consider both the ground plane and the PCM of infinite extent without taking into account possible truncation effects, as it is typical for leaky-wave antennas with high aperture efficiency [

11]. As concerns the source, an FPCA is commonly fed by any LP dipole-like radiator [

21]. The use of a horizontal magnetic dipole (HMD), typically implemented through a resonant slot on the ground plane [

36], or an HED, usually in the form of a L-probe [

21], allows for obtaining broadside pencil beams, which are instead not possible with vertical dipole sources [

11].

Concerning the PCM, this has been designed on the basis of the one proposed in [

27], which has been suitably improved in order to ensure a good performance at different elevation and azimuth angles to allow for an efficient electronic scan of the beam. In particular, the PCM consists of three metallic patches on top of two square Rogers RO3203 dielectric substrates, whose dimensions are reported in

Table 1. The bottom metallic square patch is responsible of field reflections inside the cavity [

27], while the top metallic patch is shaped to obtain an LP-to-CP conversion [

26]. The symmetry of the upper metallic patch with respect to the diagonal plane (see

Figure 1) is instrumental to obtain a right-hand circular polarization (RHCP) [

26,

27]. The two top/bottom metallic sheets are separated by a further metallic layer located between them; the electrical coupling between the top and bottom layers is ensured by a pair (rather than a single, as in [

27]) vertical via holes, whose symmetric location with respect to the center of the unit cell helps in improving the scanning performance of the resulting antenna.

As in [

27], thanks to the stratified geometry of the PCM, one may optimize transmission features by tailoring the top patch without significantly affecting the reflection features, which are essentially established by the bottom patch. The phase of the reflection coefficient is used, in particular, to dimension the cavity height

h for maximum radiated power at broadside according to von Trentini’s formula [

20]. A broadside pencil beam is obtained for

.

Since typical multiple reflections inside a FPCA are supposed to modify the conversion properties of the free-standing PCM, we directly optimize the polarization-conversion properties of the latter in a reciprocity-based scenario. The latter accounts for multiple bounces that define the actual behavior of the device.

The optimization of the PCM top patch is performed by tuning the dimensions of its constituent elements on a given azimuthal plane, here the plane, such that the CP conditions are fulfilled, i.e., =, and 90°.

The standard reciprocity-theorem formulation is given by

where

and

represent the electric current density and the electric field, respectively, in the presence of the source (subscript ’HED’) or of a test dipole in the far-field region producing an impinging plane wave (subscript ’test’).

By reciprocity, the electric fields sampled by an ideal probe (oriented as the original HED), produced by plane waves impinging on the structure from different azimuthal and elevation angles, allow for recovering the overall 3-D far-field pattern for the

and

components from the incident TE and TM Floquet waves in the unit cell [

37]. The CP components are finally obtained by the following transformation:

with

and

being the right-hand and left-hand circular-polarization components, respectively.

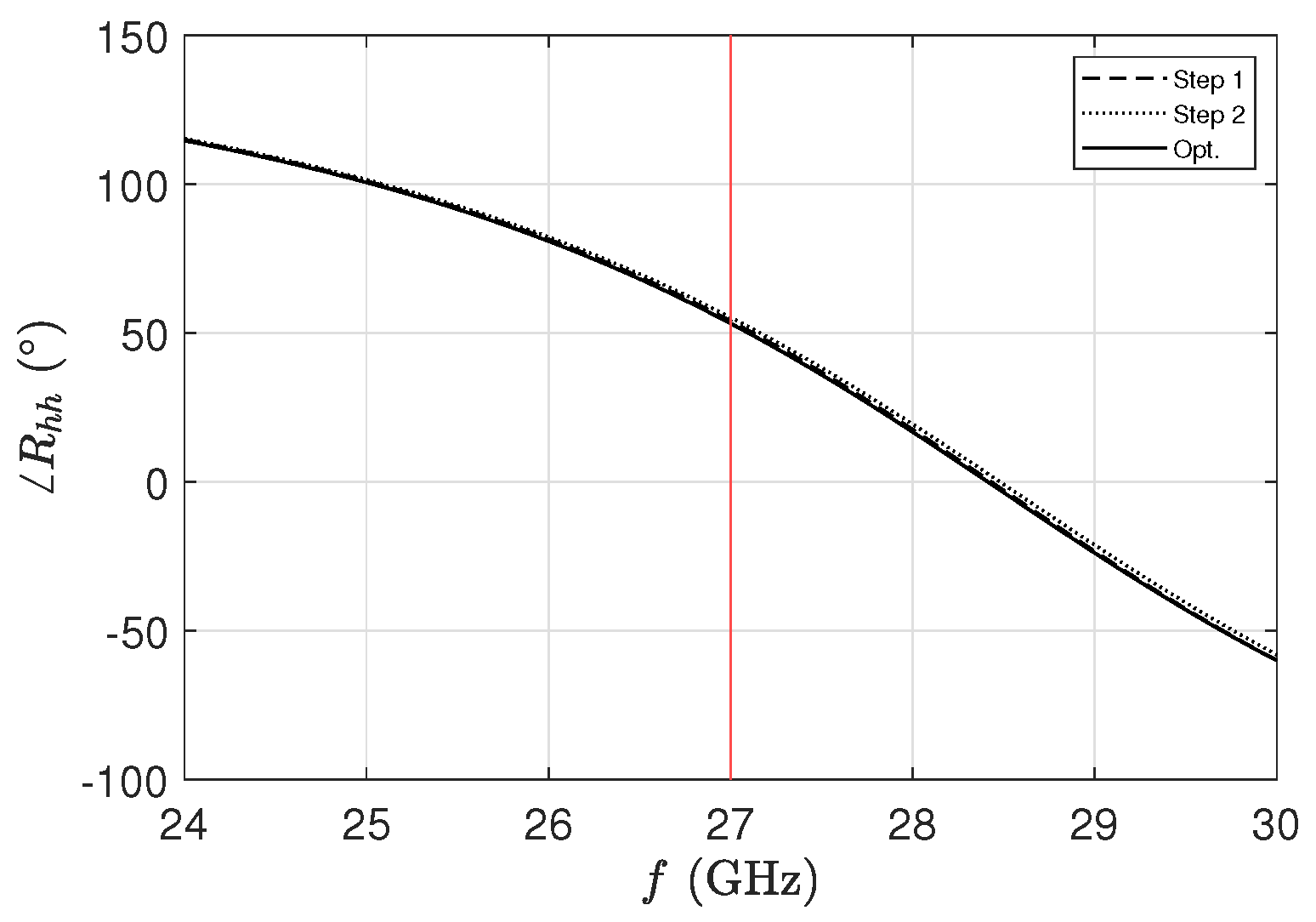

The design parameters of the PCM are here optimized to have an RHCP broadside pencil beam at 27 GHz with low cross-polarization levels. Thanks to the aforementioned decoupling between the top and bottom layers of the PCM, the modifications introduced in the optimization of the top layer have very little impact on the reflection coefficient and hence on the cavity height. This concept is corroborated in

Figure 2, where the reflection-coefficient phase is reported for different optimization steps showing a quasi-perfect superposition.

The complete list of optimized unit-cell parameters is reported in Table 1, (see

Figure 1 for the definition of the symbols).

3. FPCA: Element Patterns and Far-Field Polarization

At this stage, one can evaluate the far-field components

and

over different directions, and, thus, obtain the corresponding

and

quantities through (

2). The far-field pattern of the

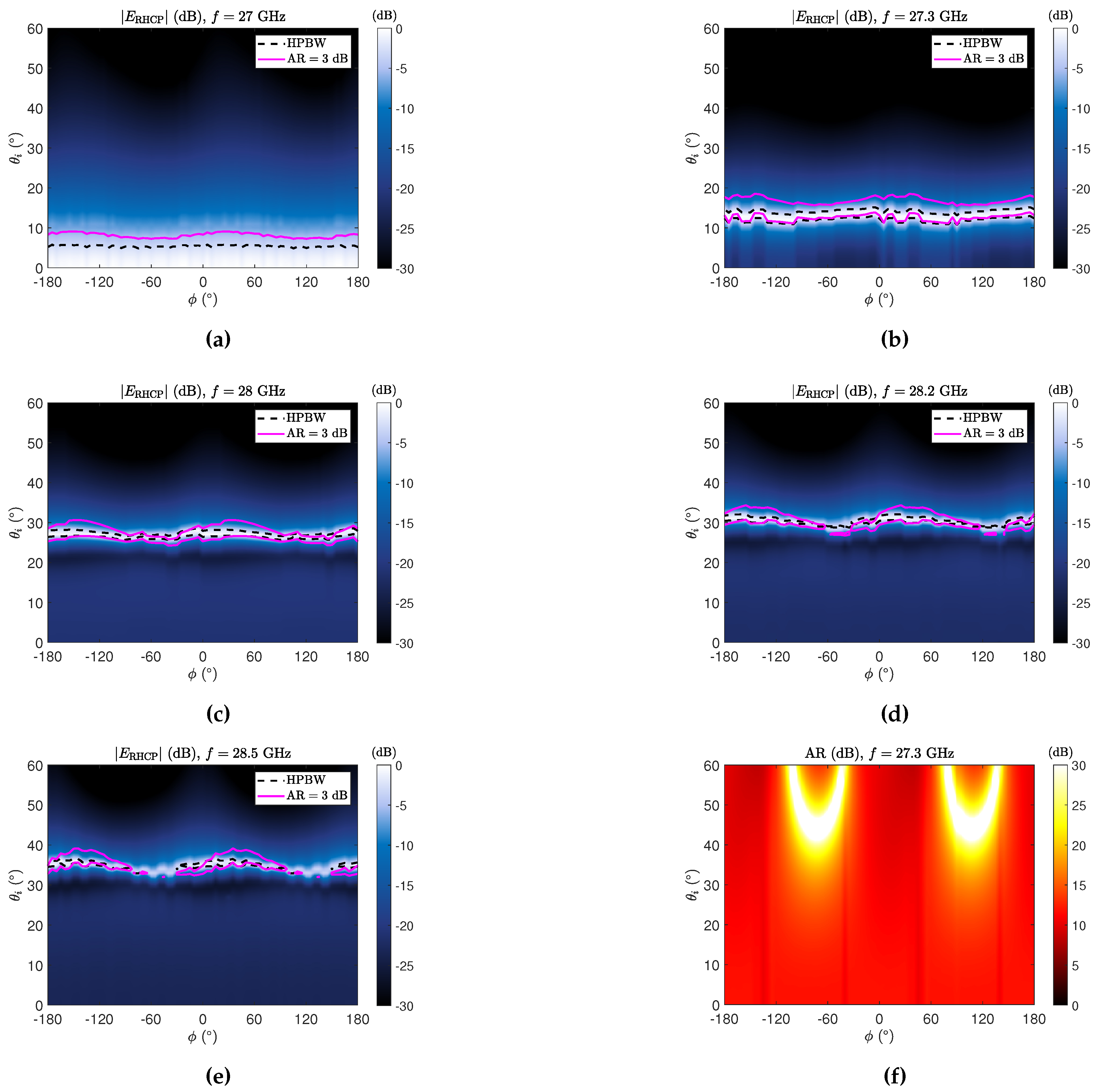

component is reported in

Figure 3(a)–(e), for different frequencies in the overall range 27–28.5 GHz. As expected, in

Figure 3(a) a broadside pencil beam is observed at 27 GHz. The −3 dB gain and 3 dB AR isolines are reported with a dashed black line and solid magenta line, respectively. It is manifest that the design process effectively led to a CP narrow beam at broadside for 27 GHz.

As expected, as frequency increases, the pencil beam turns into a conical beam preserving its CP feature. As shown in

Figure 3(b), at 27.3 GHz, an almost azimuthally symmetric beam pointing at

= 12° is obtained with a half-power beamwidth (HPBW) well within the 3 dB AR range, thus demonstrating that the CP condition is maintained over the main beam. At higher frequencies, namely up to 28.2 GHz, one may observe from

Figure 3(c) and

Figure 3(d) that a CP beam is maintained at elevation angle as large as

. However, in this latter operating condition, the azimuthal symmetry of the beam is affected and the CP condition compromised around

= -50° and

= 130°. Such behavior is more evident at even larger frequencies (see results for 28.5 GHz in

Figure 3(e)), where CP condition is compromised over larger azimuthal ranges, with the radiation maximum occurring for

. Additional increase in frequency, although not shown, further enlarges the regions outside the CP regime, thus worsening the antenna radiation performance.

Finally, in

Figure 3(f), the importance of choosing the unit-cell design parameters in a

cavity environment is stressed. The colormap shows the AR considering the PCM in a

free-standing environment, after the reciprocity-driven optimization process. As is manifest, the AR levels are completely outside those limits that enclose the CP region, thus suggesting that the ground plane presence strongly modifies the PCM behavior.

4. FPCA: Array Feeding and Azimuth Scan

So far, the presented FPCA results confirm the possibility of scanning by frequency the elevation plane with a directive CP beam thanks to the proposed PCM. However, the proposed solution does not allow for both having a pencil beam off broadside and varying the azimuthal angle of the beam. For this purpose, a 2-D grid of sources can be used by exploiting the pattern multiplication principle of array theory. This idea has been demonstrated in [

38] (an overview about array-fed 2-D LWAs is given in [

39]) for LP beams using a planar array of feeders to gain further control of the beam features of an FPCA. In particular, the leaky-wave dispersion is exploited to scan by frequency the beam in elevation, whereas the phasing of the feeders allows for scanning in azimuth. This technique is here suitably modified for CP beams.

As is known from basic theory, the far electric-field pattern

radiated by the array is given by:

where

is the element-pattern radiated by a single HED source placed at the origin of the reference system and

is the relevant array factor. Here the HEDs are arranged in a uniform planar 2-D array configuration so that the array factor is given by [

32]:

where

N is the number of elements along the

x axis,

M the number along the

y axis and the quantities

and

depend on the spherical angles

, and the phase shifts

along

through:

where

k is the wavenumber and

and

stand for inter-element spacing along

x and

y axes, respectively.

Here, we consider

and

, for a total number of 40 elements. A common design criterion in standard antenna array theory consists in requiring the distance between adjacent elements being lower than half a wavelength. This is to avoid grating lobes, specially if it is necessary to scan elevation angles far from broadside, namely up to 60° and beyond. Here, the elevation angle is limited to approximately 40°, so grating lobes should not appear even if such a condition is not strictly met. Additionally, possible unwanted lobes at different pointing angles are washed away due to high elevation selectivity of the element pattern, suggesting that sparser feeding grids can be considered. Consequently, an equal inter-element spacing along the two directions, viz.

, has been chosen, setting a distance equal to twice the unit-cell periodicity,

mm. Since the lower frequency is 27 GHz, corresponding to

mm, the element spacing is slightly higher than half a wavelength but results in

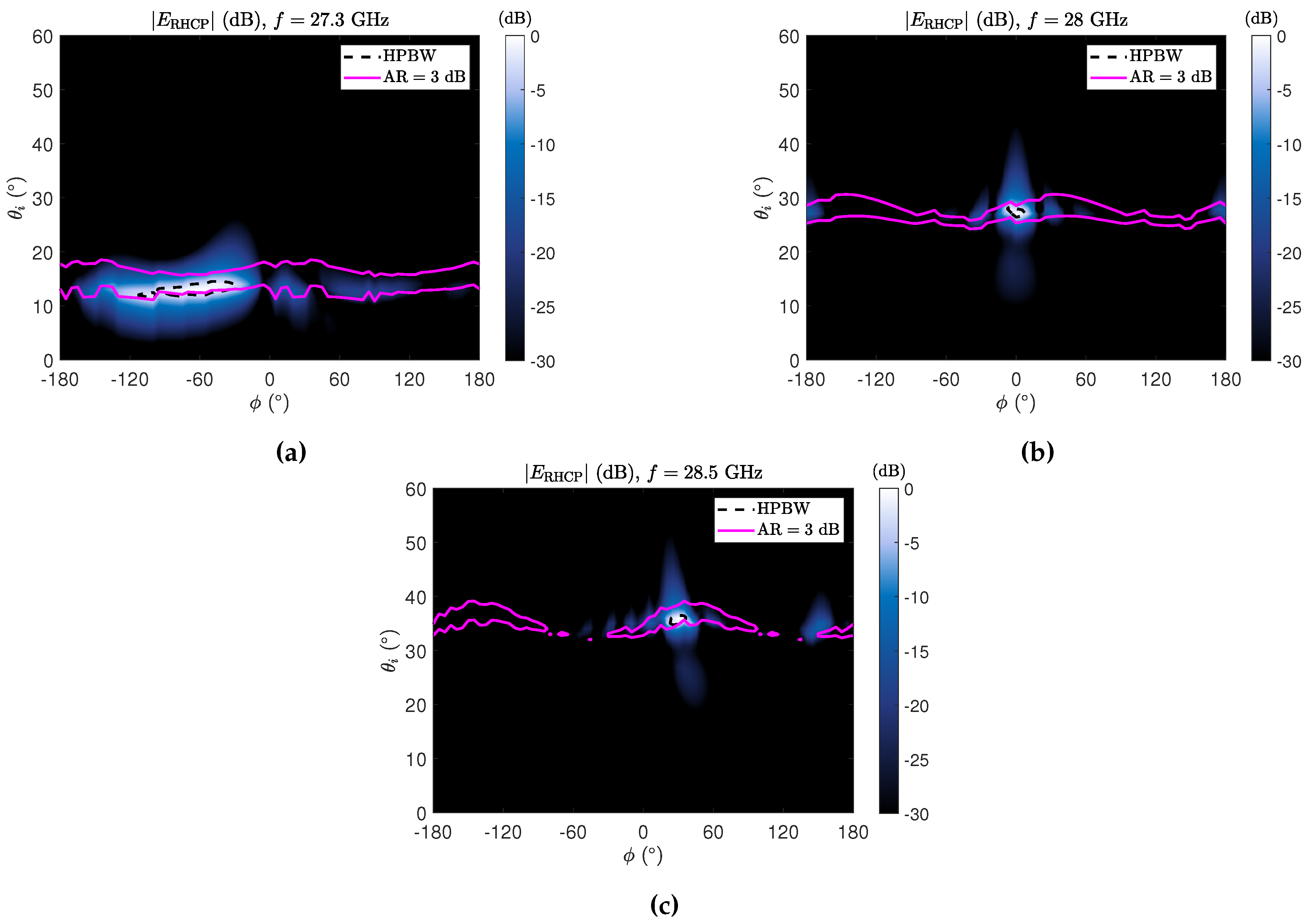

Figure 4 confirm that we still manage to suppress all the spurious lobes. In particular, in

Figure 4, the ability of the proposed FPCA to radiate a CP pencil beam in any elevation direction (between

and

) as well as any azimuthal direction is demonstrated. Specifically, in

Figure 4(a) we show the possibility of producing a CP beam with the maximum at

on the

plane. The desired elevation angle is obtained by considering a 27.3 GHz working frequency, by exploiting the inherent frequency-scanning property of the LWA element pattern [see

Figure 3(b)]. As concerns the azimuth-angle pointing direction

, the array theory is used achieving, through (

5), the required inter-element phase difference values of

and

. In a similar manner, by fixing the working frequency at 28 GHz and setting

and

, we ensure a perfect CP pencil-beam with the maximum on

at

[see

Figure 4(b)]. Similarly, by further increasing the frequency to 28.5 GHz and, thus, considering the maximum of the element pattern at

, a perfectly CP pencil beam can be obtained on the

plane imposing

and

[see

Figure 4(c)].

We have thus demonstrated that the proposed array-fed FPCA is able to generate a pure CP pencil beam pointing at various directions. It is worthwhile to point out that the proposed approach does not consider the mutual coupling among the sources. However, as shown in [

38] and experimentally validated in [

40], this effect can be taken into account and easily mitigated, keeping cross-coupling scattering coefficients well under the threshold of

dB.