Submitted:

13 November 2024

Posted:

14 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthetic Dataset

2.1.1. Simulation Setup

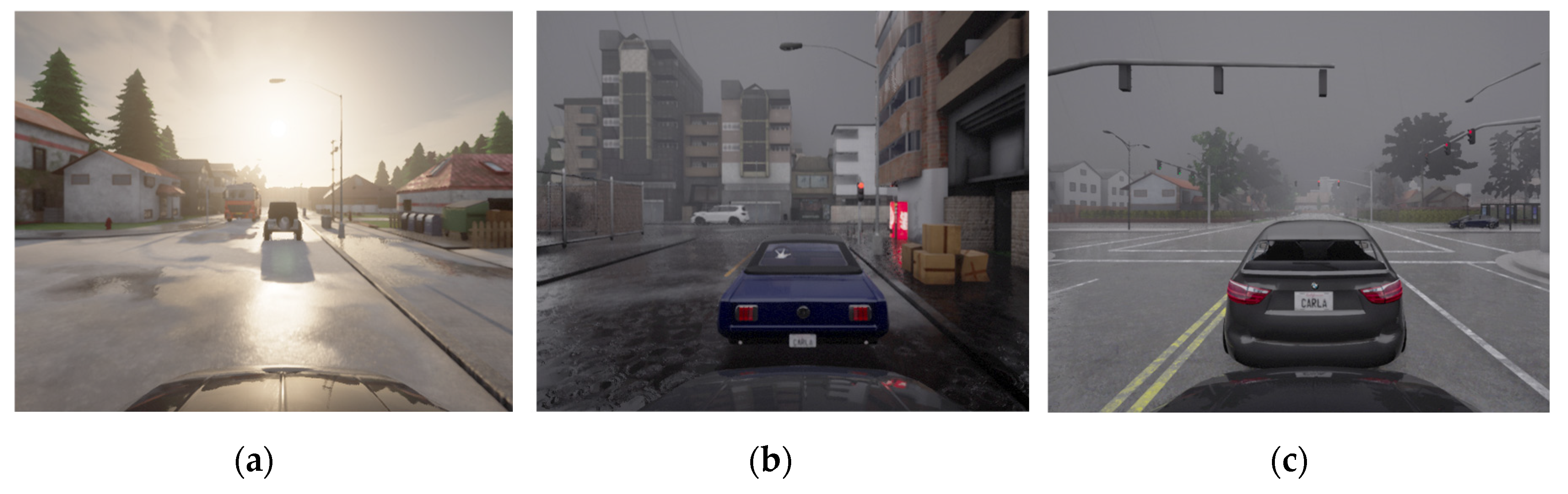

- (a)

- Town01 is a small simple residential village.

- (b)

- Town02 is a simple town with a mixture of residential and commercial buildings.

- (c)

- Town03 is a medium sized urban map with junctions and a roundabout.

- (d)

- Town04 is a small mountain village with an infinite loop highway.

- (e)

- Town05 is a squared-grid town with cross junctions and a bridge. It has multiple lanes in each direction to perform lane changes.

- (f)

- Town10 is a larger urban environment with skyscrapers and residential buildings.

2.1.2. Simulation Design

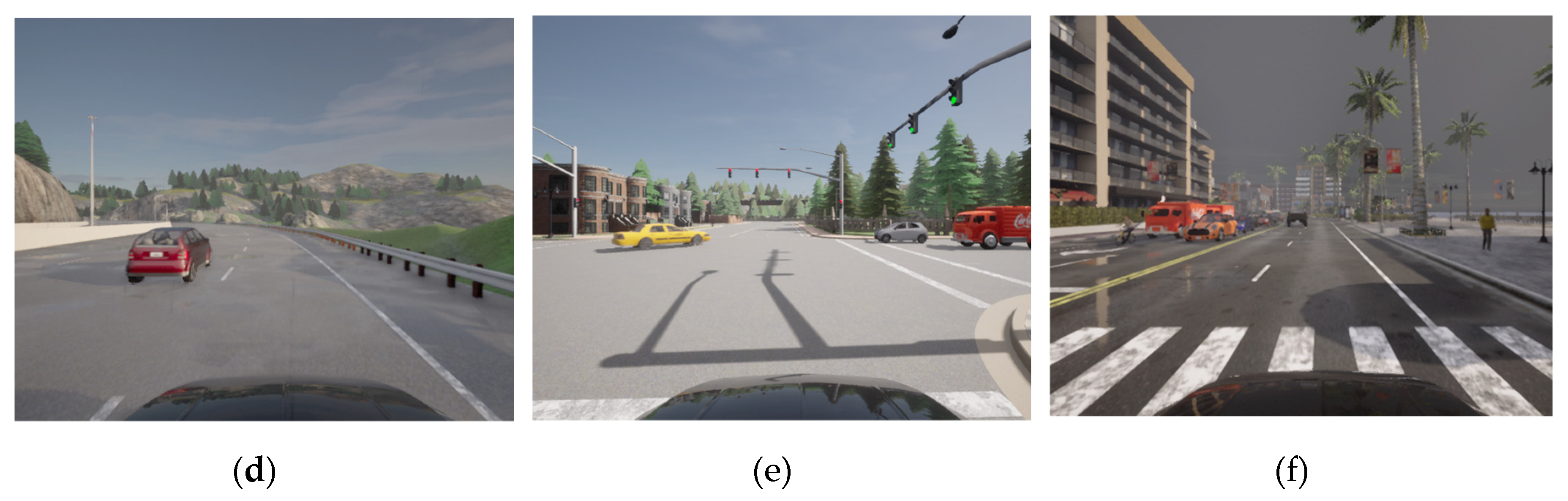

2.2. End-to-End Architecture Design

3. Results

3.1. Model Configuration

- The Mean Absolute Error (MAE) which is the average of the absolute differences between the predicted and actual values.

- The Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE) which is calculated dividing the MAE by the range of the speed and angle data. The range is the difference between the maximum and minimum values of the variables to predict.

- The coefficient of determination, R2 was used to evaluate the quality of the results obtained by the model.

3.2. Application of the Pretrained CNN for Training with a Real-World Dataset

3.2.1. Real-World Dataset

3.2.2. Baseline Training with Only Real-World Data

3.2.3. Pretraining with the Synthetic Dataset

3.3. Analysis of the Architecture with and Without Edge Detection Layers for Transfer Learning

4. Discussion

| Authors, Ref. | Dataset | Data Type | Input | Output | MAE (km/h)/ (°) | MAPE (%) | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bojarski et al., [45,47] | Udacity | Synthetic | RGB | Steering Angle | 4.26 | - | - |

| Yang et al., [45] | Udacity | Synthetic | RGB | Speed/ Steering Angle | 0.68 / 1.26 | - | - |

| SAIC | Real | RGB | Speed | 1.62 | - | - | |

| Xu et al., [48] | BDDV | Real | RGB | Steering Angle | - | 15.4 | - |

| Wang et al., [46] | GAC | Real | RGB | Speed/Steering Angle | 4.25 / 3.55 | - | - |

| GTAV | Synthetic | RGB | Speed/Steering Angle | 3.28 / 2.84 | - | - | |

| Navarro et al., [9] | UPCT | Real | RGB + IMU | Speed/Steering Angle | 0.98 / 3.61 | 1.69 / 0.43 | - |

| Prasad [49] | - | Real | RGB | Steering Angle | - | - | 0.819 |

| Proposed: BorderNet | Carla | Synthetic | RGBD + IMU | Speed/Steering Angle | 1.47 / 0.51 | 1.59 / 0.55 | 0.977 / 0.948 |

| UPCT | Real World | RGBD + IMU | Speed/Steering Angle | 0.61 / 0.41 | 1.04 / 0.53 | 0.989 / 0.973 |

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Navarro, P. J.; Fernández, C.; Borraz, R.; Alonso, D. A Machine Learning Approach to Pedestrian Detection for Autonomous Vehicles Using High-Definition 3D Range Data. Sensors 2017, 17.

- Ros García, A.; Miller, L.; Fernández, C.; Navarro, P. J. Obstacle Detection using a Time of Flight Range Camera. In 2018 IEEE International Conference on Vehicular Electronics and Safety (ICVES); 2018; pp. 1–6.

- Akai, N.; Morales, L. Y.; Yamaguchi, T.; Takeuchi, E.; Yoshihara, Y.; Okuda, H.; Suzuki, T.; Ninomiya, Y. Autonomous driving based on accurate localization using multilayer LiDAR and dead reckoning. In 2017 IEEE 20th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC); 2017; pp. 1–6.

- Teng, S.; Hu, X.; Deng, P.; Li, B.; Li, Y.; Ai, Y.; Yang, D.; Li, L.; Xuanyuan, Z.; Zhu, F.; Chen, L. Motion Planning for Autonomous Driving: The State of the Art and Future Perspectives. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Vehicles 2023, 8, 3692–3711.

- Borraz, R.; Navarro, P. J.; Fernández, C.; Alcover, P. M. Cloud Incubator Car: A Reliable Platform for Autonomous Driving. Applied Sciences 2018, 8.

- Kong, J.; Pfeiffer, M.; Schildbach, G.; Borrelli, F. Kinematic and dynamic vehicle models for autonomous driving control design. In 2015 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV); 2015; pp. 1094–1099.

- Wu, P.; Jia, X.; Chen, L.; Yan, J.; Li, H.; Qiao, Y. Trajectory-guided Control Prediction for End-to-end Autonomous Driving: A Simple yet Strong Baseline. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2022; pp. 6119–6132.

- Chitta, K.; Prakash, A.; Geiger, A. NEAT: Neural Attention Fields for End-to-End Autonomous Driving. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV); 2021; pp. 15793–15803.

- Navarro, P. J.; Miller, L.; Rosique, F.; Fernández-Isla, C.; Gila-Navarro, A. End-to-End Deep Neural Network Architectures for Speed and Steering Wheel Angle Prediction in Autonomous Driving. Electronics (Switzerland) 2021, 10.

- Mozaffari, S.; Al-Jarrah, O. Y.; Dianati, M.; Jennings, P.; Mouzakitis, A. Deep Learning-Based Vehicle Behavior Prediction for Autonomous Driving Applications: A Review. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2022, 23, 33–47.

- Xu, J.; Wu, T. End-to-end autonomous driving based on image plane waypoint prediction. In 2022 International Symposium on Control Engineering and Robotics (ISCER); 2022; pp. 132–137.

- Wu, P.; Jia, X.; Chen, L.; Yan, J.; Li, H.; Qiao, Y. Trajectory-guided Control Prediction for End-to-end Autonomous Driving: A Simple yet Strong Baseline. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2022; pp. 6119–6132.

- Cai, P.; Wang, S.; Wang, H.; Liu, M. Carl-Lead: Lidar-based End-to-End Autonomous Driving with Contrastive Deep Reinforcement Learning. 2021, 2109.08473.

- Shao, H.; Wang, L.; Chen, R.; Li, H.; Liu, Y. Safety-Enhanced Autonomous Driving Using Interpretable Sensor Fusion Transformer. In Proceedings of The 6th Conference on Robot Learning; 2023; pp. 726–737.

- Chitta, K.; Prakash, A.; Jaeger, B.; Yu, Z.; Renz, K.; Geiger, A. TransFuser: Imitation With Transformer-Based Sensor Fusion for Autonomous Driving. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell 2023, 45, 12878–12895.

- Chen, D.; Krahenbuhl, P. Learning From All Vehicles. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2022; pp. 17222–17231.

- Li, W.; Gu, J.; Dong, Y.; Dong, Y.; Han, J. Indoor scene understanding via RGB-D image segmentation employing depth-based CNN and CRFs. Multimed Tools Appl 2019, 79, 35475–35489.

- Xiao, Y.; Codevilla, F.; Gurram, A.; Urfalioglu, O.; López, A. M. Multimodal End-to-End Autonomous Driving. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2022, 23, 537–547.

- Chen, L.; Wu, P.; Chitta, K.; Jaeger, B.; Geiger, A.; Li, H. End-to-end Autonomous Driving: Challenges and Frontiers. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell 2024, 1–20.

- Chen, Y.; Rong, F.; Duggal, S.; Wang, S.; Yan, X.; Manivasagam, S.; Xue, S.; Yumer, E.; Urtasun, R. GeoSim: Realistic Video Simulation via Geometry-Aware Composition for Self-Driving. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2021; pp. 7230–7240.

- Zhang, L.; Wen, T.; Min, J.; Wang, J.; Han, D.; Shi, J. Learning Object Placement by Inpainting for Compositional Data Augmentation. In {Computer Vision - ECCV 2020; 2020; pp. 566–581.

- Chen, Y.; Li, W.; Sakaridis, C.; Dai, D.; Van Gool, L. Domain Adaptive Faster R-CNN for Object Detection in the Wild. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2018.

- Zhang, H.; Luo, G.; Tian, Y.; Wang, K.; He, H.; Wang, F.-Y. A Virtual-Real Interaction Approach to Object Instance Segmentation in Traffic Scenes. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2021, 22, 863–875.

- Rosique, F.; Navarro, P. J.; Miller, L.; Salas, E. Autonomous Vehicle Dataset with Real Multi-Driver Scenes and Biometric Data. Sensors 2023, 23.

- Song, Z.; He, Z.; Li, X.; Ma, Q.; Ming, R.; Mao, Z.; Pei, H.; Peng, L.; Hu, J.; Yao, D.; Zhang, Y. Synthetic Datasets for Autonomous Driving: A Survey. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Vehicles 2024, 9, 1847–1864.

- Paulin, G.; Ivasic-Kos, M. Review and analysis of synthetic dataset generation methods and techniques for application in computer vision. Artif Intell Rev 2023, 56, 9221–9265.

- Sakaridis, C.; Dai, D.; Van Gool, L. Semantic Foggy Scene Understanding with Synthetic Data. Int J Comput Vis 2018, 126, 973–992.

- Sun, T.; Segu, M.; Postels, J.; Wang, Y.; Van Gool, L.; Schiele, B.; Tombari, F.; Yu, F. SHIFT: A Synthetic Driving Dataset for Continuous Multi-Task Domain Adaptation. IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR) 2022, 21371–21382.

- Alberti, E.; Tavera, A.; Masone, C.; Caputo, B. IDDA: A Large-Scale Multi-Domain Dataset for Autonomous Driving. IEEE Robot Autom Lett 2020, 5, 5526–5533.

- Kloukiniotis, A.; Papandreou, A.; Anagnostopoulos, C.; Lalos, A.; Kapsalas, P.; Nguyen, D-, V.; Moustakas, K. CarlaScenes: A synthetic dataset for odometry in autonomous driving. In IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops; 2022; pp. 4519–4527.

- Ramesh, A. N.; Correas-Serrano, A. M. G.-H. SCaRL- A Synthetic Multi-Modal Dataset for Autonomous Driving. In International Conference on Microwaves for Intelligent Mobility; 2024.

- Pitropov, M.; Garcia, D. E.; Rebello, J.; Smart, M.; Wang, C.; Czarnecki, K.; Waslander, S. Canadian Adverse Driving Conditions dataset. Int J Rob Res 2020, 40, 681–690.

- Yin, H.; Berger, C. When to use what data set for your self-driving car algorithm: An overview of publicly available driving datasets. In IEEE 20th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC); 2017; pp. 1–8.

- Ros, G.; Sellart, L.; Materzynska, J.; Vazquez, D.; Lopez, A. M. The SYNTHIA Dataset: A Large Collection of Synthetic Images for Semantic Segmentation of Urban Scenes. In IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2016; pp. 3234–3243.

- Saleh, F. S.; Aliakbarian, M. S.; Salzmann, M.; Petersson, L.; Alvarez, J. M. Effective Use of Synthetic Data for Urban Scene Semantic Segmentation. In European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV); 2018.

- Li, X.; Wang, K.; Tian, Y.; Yan, L.; Deng, F.; Wang, F.-Y. The ParallelEye Dataset: A Large Collection of Virtual Images for Traffic Vision Research. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2019, 20, 2072–2084.

- Hurl, B.; Czarnecki, K.; Waslander, S. Precise Synthetic Image and LiDAR (PreSIL) Dataset for Autonomous Vehicle Perception. In IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV); 2019.

- Koopman, P.; Wagner, M. Challenges in Autonomous Vehicle Testing and Validation. SAE Int J Transp Saf 2016, 4, 15–24.

- Tampuu, A.; Matiisen, T.; Semikin, M.; Fishman, D.; Muhammad, N. A Survey of End-to-End Driving: Architectures and Training Methods. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst 2022, 33, 1364–1384.

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Ros, G.; Codevilla, F.; Lopez, A.; Koltun, V. CARLA: An Open Urban Driving Simulator. In Proceedings of the 1st Annual Conference on Robot Learning; 2017; pp. 1–16.

- {Vitols, G.; Bumanis, N.; Arhipova, I.; Meirane, I. LiDAR and Camera Data for Smart Urban Traffic Monitoring: Challenges of Automated Data Capturing and Synchronization. In Applied Informatics; 2021; pp. 421–432.

- Tan, M.; Le, Q. V EfficientNetV2: Smaller Models and Faster Training. In INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON MACHINE LEARNING, VOL 139; 2021; pp. 7102–7110.

- Dosovitskiy, A.; Beyer, L.; Kolesnikov, A.; Weissenborn, D.; Zhai, X.; Unterthiner, T.; Dehghan, M.; Minderer, M.; Heigold, G.; Gelly, S.; Uszkoreit, J.; Houlsby, N. AN IMAGE IS WORTH 16X16 WORDS: TRANSFORMERS FOR IMAGE RECOGNITION AT SCALE. In International Conference on Learning Representations; 2021.

- Masand, A.; Chauhan, S.; Jangid, M.; Kumar, R.; Roy, S. ScrapNet: An Efficient Approach to Trash Classification. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 130947–130958.

- Yang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, J.; Cai, J.; Luo, J. End-to-end Multi-Modal Multi-Task Vehicle Control for Self-Driving Cars with Visual Perceptions. In 24th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR); 2018; pp. 2289–2294.

- Wang, D.; Wen, J.; Wang, Y.; Huang, X.; Pei, F. End-to-End Self-Driving Using Deep Neural Networks with Multi-auxiliary Tasks. Automotive Innovation 2019, 2, 127–136.

- Bojarski, M.; Yeres, P.; Choromanska, A.; Choromanski, K.; Firner, B.; Jackel, L.; Muller, U. Explaining How a Deep Neural Network Trained withEnd-to-End Learning Steers a Car. In Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (cs.CV); 2017.

- Xu, H.; Gao, Y.; Yu, F.; Darrell, T. End-To-End Learning of Driving Models From Large-Scale Video Datasets. In IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2017; pp. 2174–2182.

- Prasad Mygapula, D. V; Adarsh, S.; Sajith Variyar, V. V; Soman, K. P. CNN based End to End Learning Steering Angle Prediction for Autonomous Electric Vehicle. In Fourth International Conference on Electrical, Computer and Communication Technologies (ICECCT); 2021; pp. 1–6.

| Dataset/Year | Samples | Image Type | IMU | LIDAR | RADAR | Vehicle Control | Raw Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Udacity [33]/2016 | 34 K | RGB | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| SYNTHIA [34]/2016 | 213K | RGB | No | No | No | No | No |

| VEIS [35]/2018 | 61K | RGB | No | No | No | No | No |

| ParallelEye [36]/2019 | 40 K | RGB | No | No | No | No | No |

| PreSIL 6[37]/2019 | 50 K | RGB | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| IDDA [29]/2020 | 1M | RGB, D | No | No | No | No | No |

| CarlaScenes [30]/2021 | - | RGB, D | Yes | Yes | No | No | Partial |

| SHIFT[28]/2022 | 2.6 M | RGB, D | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Proposed: CarlaMRD | 150K | RGB, D | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Sensor | Data Type |

|---|---|

| RGB Camera | RGB image 640x480, fov=90°. |

| Depth Camera | Depth image 640x480, fov=90°. |

| IMU |

Acceleration x,y,z (m/s2). Angular Velocity x,y,z (°/s). Orientation x,y,z (°). |

| LIDAR |

3D pointcloud, x,y,z,intensity. Channels=64, f=20, range=100m, points per second = 500000. |

| RADAR |

2D pointcloud: polar coordinates, distance and velocity. Horizontal fov=45°, Vertical fov=30°. |

| Vehicle Control |

Steering angle (rad). Speed (km/h). Accelerator pedal (Value from 0 to 1). Brake pedals (Value from 0 to 1). |

| Parameter | Variable |

|---|---|

| Batch size | 20 |

| Optimization algorithm | RMSprop |

| Loss function | Huber |

| Metric | Mean Absolute Error |

| Learning rate | 0.001 |

| Fold | Variable | MAE (Km/h, °) | MAPE | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Speed | 1.66 | 1.80 % | 0.973 |

| Angle | 0.65 | 0.71 % | 0.944 | |

| 2 | Speed | 1.21 | 1.32 % | 0.986 |

| Angle | 0.41 | 0.46 % | 0.952 | |

| 3 | Speed | 1.41 | 1.53 % | 0.978 |

| Angle | 0.45 | 0.50 % | 0.952 | |

| 4 | Speed | 1.80 | 1.95 % | 0.971 |

| Angle | 0.96 | 0.62 % | 0.939 | |

| 5 | Speed | 1.27 | 1.37 % | 0.981 |

| Angle | 0.45 | 0.49 % | 0.954 |

| Variable | MAE (Km/h, °) | MAPE | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Speed | 1.47 | 1.59 % | 0.978 |

| Angle | 0.51 | 0.55 % | 0.948 |

| Fold | Variable | MAE (Km/h, °) | MAPE | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Speed | 0.39 | 0.67 % | 0.996 |

| Angle | 0.34 | 0.44 % | 0.985 | |

| 2 | Speed | 0.48 | 0.82 % | 0.995 |

| Angle | 0.49 | 0.62 % | 0.953 | |

| 3 | Speed | 0.34 | 0.58 % | 0.997 |

| Angle | 0.34 | 0.44 % | 0.984 | |

| 4 | Speed | 0.44 | 0.75 % | 0.995 |

| Angle | 0.39 | 0.50 % | 0.969 | |

| 5 | Speed | 0.38 | 0.66 % | 0.996 |

| Angle | 0.40 | 0.51 % | 0.977 |

| Variable | MAE (Km/h, °) | MAPE | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Speed | 0.40 | 0.69 % | 0.996 |

| Angle | 0.39 | 0.50 % | 0.974 |

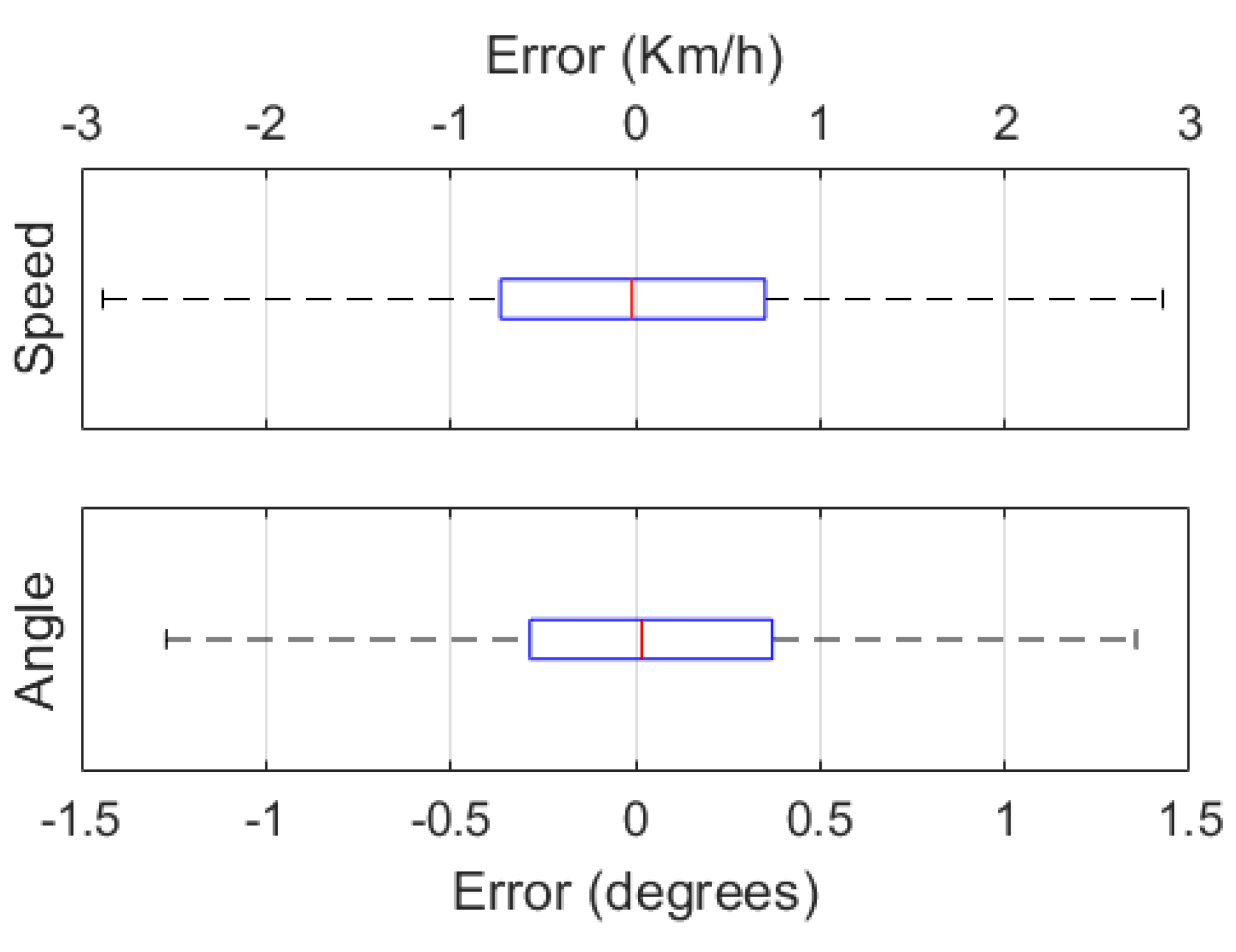

| Fold | Variable | MAE (Km/h, °) | MAPE | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Speed | 0.68 | 1.17 % | 0.987 |

| Angle | 0.43 | 0.55 % | 0.969 | |

| 2 | Speed | 0.54 | 0.94 % | 0.992 |

| Angle | 0.36 | 0.47 % | 0.976 | |

| 3 | Speed | 0.52 | 0.90 % | 0.992 |

| Angle | 0.39 | 0.50 % | 0.978 | |

| 4 | Speed | 0.70 | 1.21 % | 0.987 |

| Angle | 0.50 | 0.64 % | 0.961 | |

| 5 | Speed | 0.58 | 0.99 % | 0.989 |

| Angle | 0.38 | 0.49 % | 0.981 |

| Variable | MAE (Km/h, °) | MAPE | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Speed | 0.61 | 1.04 % | 0.989 |

| Angle | 0.41 | 0.53 % | 0.973 |

| Dataset | Variable | MAE (Km/h, °) | MAPE | R2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| w edges | w/o edges | w edges | w/o edges | w edges | w/o edges | ||

| CarlaMRD | Speed | 1.47 | 0.40 | 1.59 % | 0.69 % | 0.978 | 0.996 |

| Angle | 0.50 | 0.39 | 0.55 % | 0.50 % | 0.948 | 0.974 | |

| UPCT | Speed | 0.40 | 0.39 | 0.69 % | 0.68 % | 0.996 | 0.995 |

| Angle | 0.39 | 0.39 | 0.50 % | 0.51 % | 0.974 | 0.972 | |

| UPCT pretrained | Speed | 0.60 | 1.66 | 1.04 % | 2.86 % | 0.989 | 0.911 |

| Angle | 0.41 | 0.60 | 0.52 % | 0.77 % | 0.973 | 0.929 | |

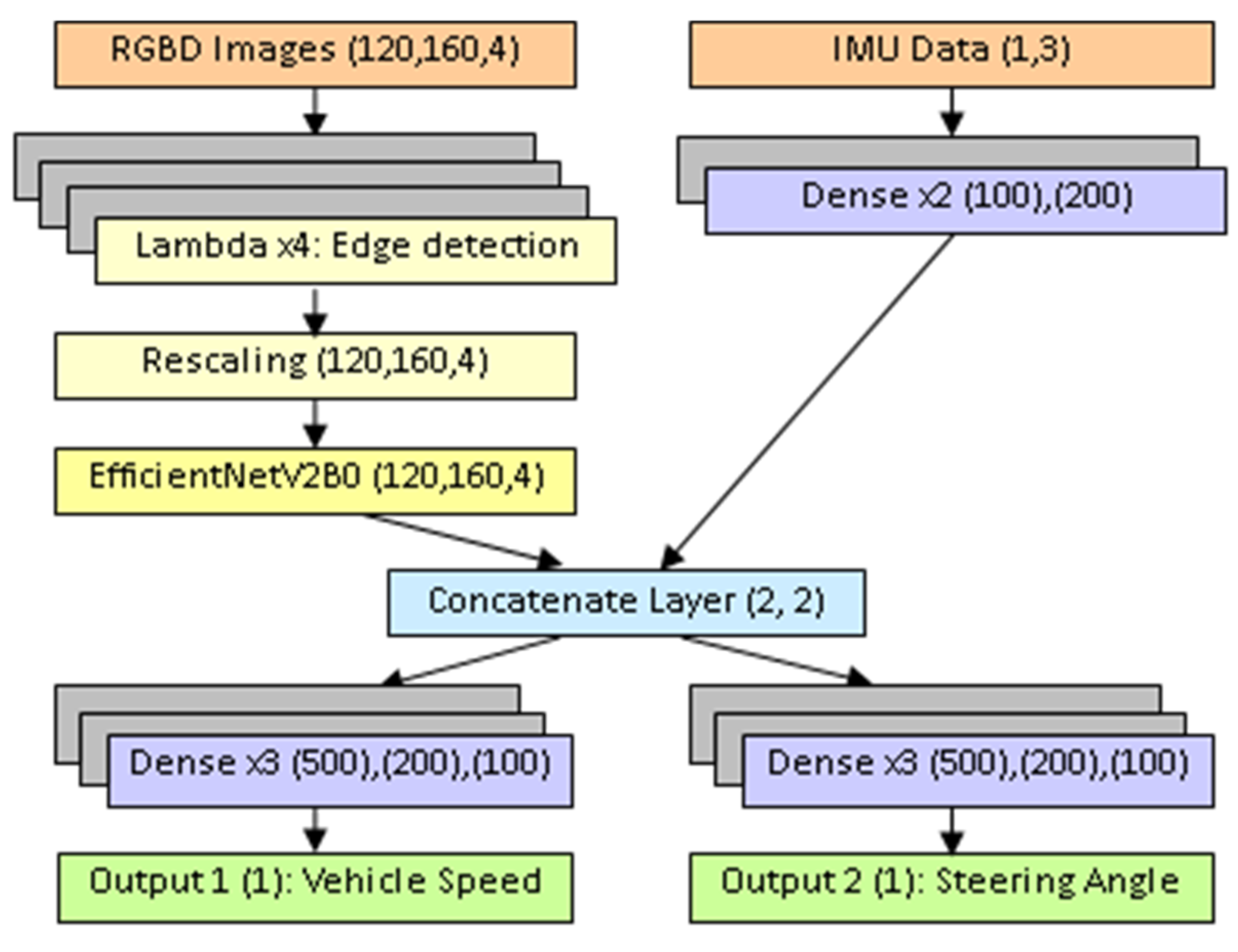

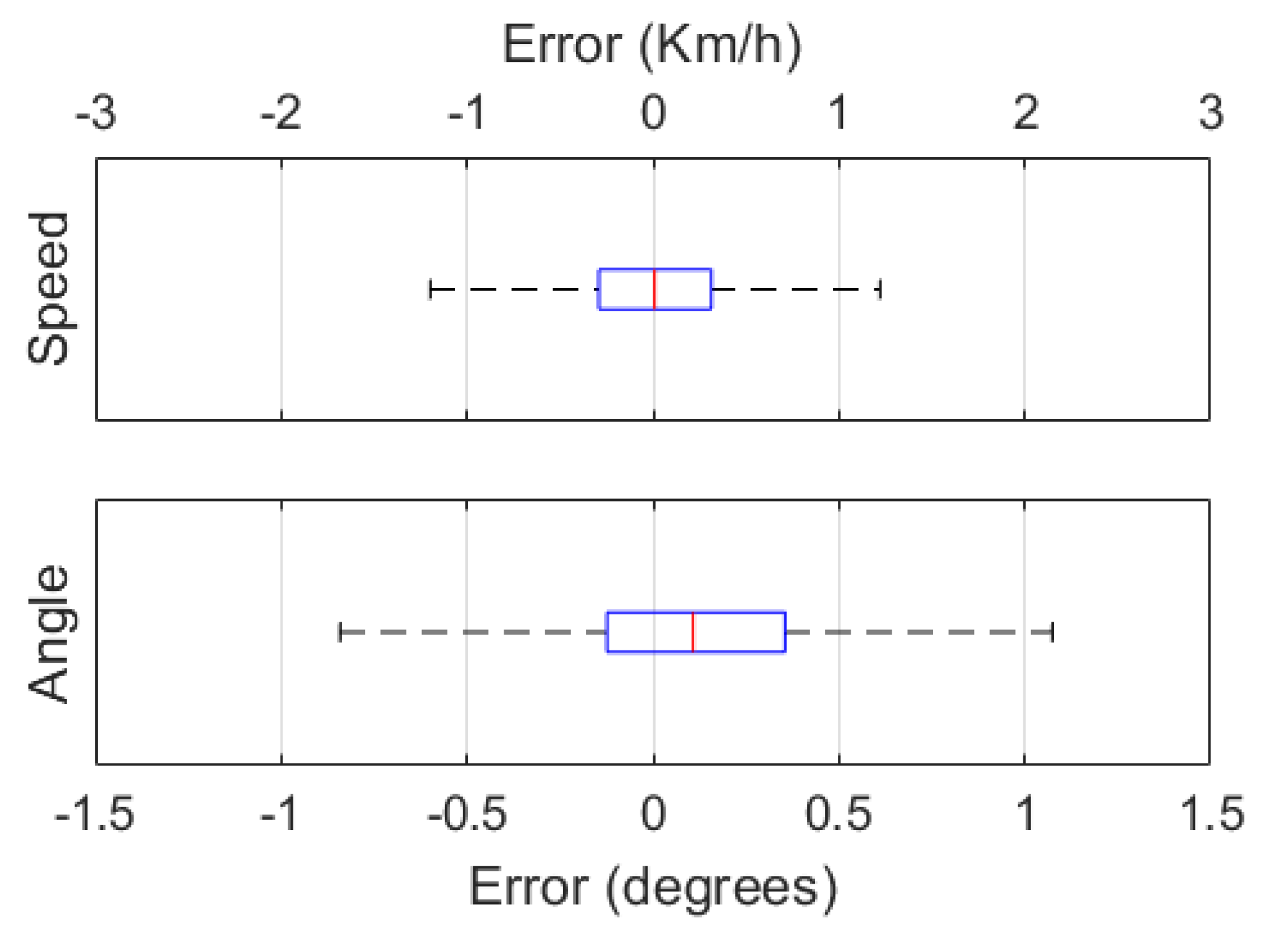

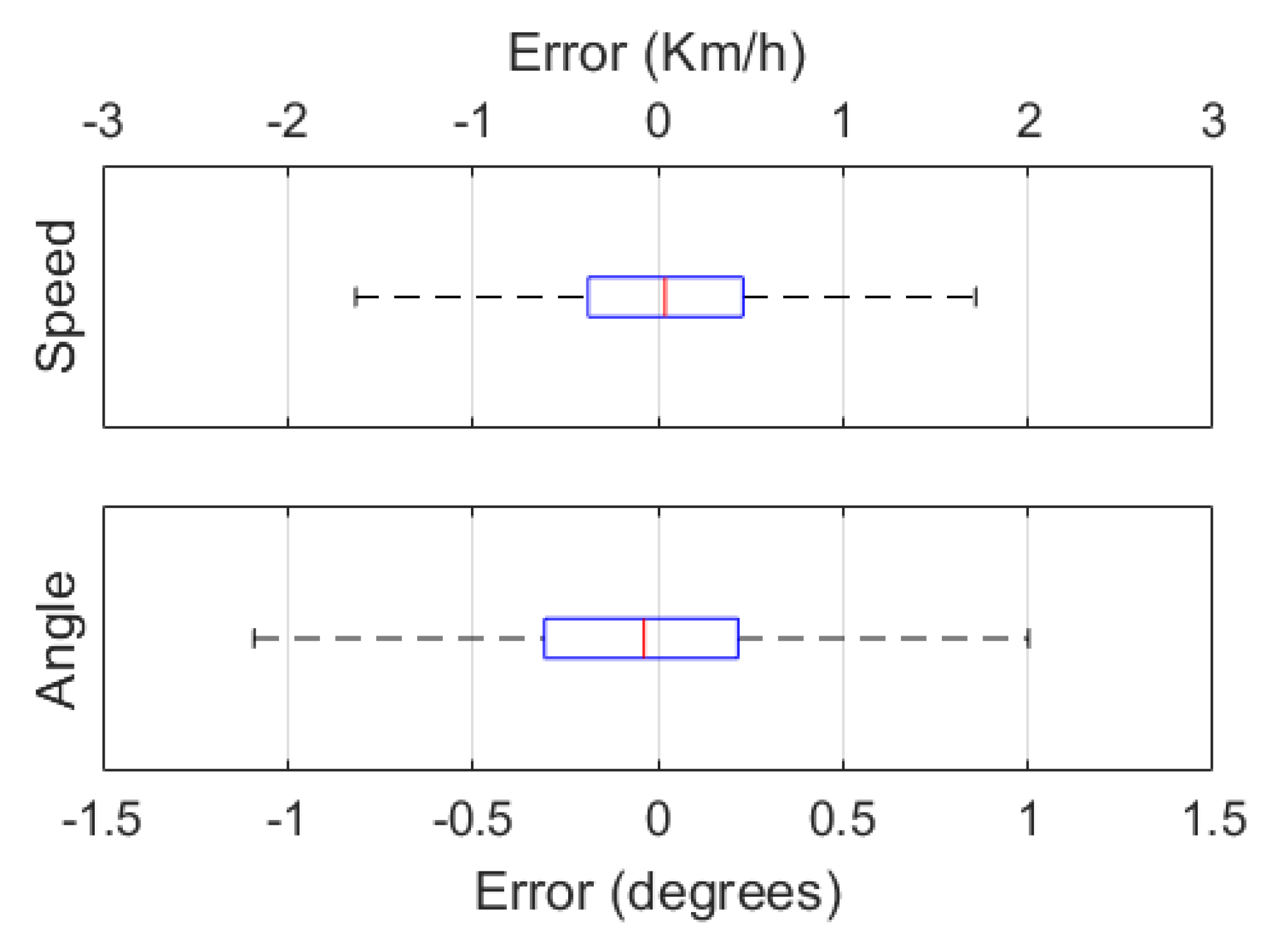

| Dataset | Variable | Q1 | Q2 (Median) | Q3 | IQR | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| w edges | w/o edges | w edges | w/o edges | w edges | w/o edges | w edges | w/o edges | ||

| UPCT pretrained | Speed (Km/h) | -0.461 | -0.703 | -0.040 | 0.019 | 0.375 | 0.731 | 0.836 | 1.434 |

| Angle (°) | -0.306 | -0.285 | -0.037 | 0.017 | 0.217 | 0.371 | 0.523 | 0.656 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).