Submitted:

12 November 2024

Posted:

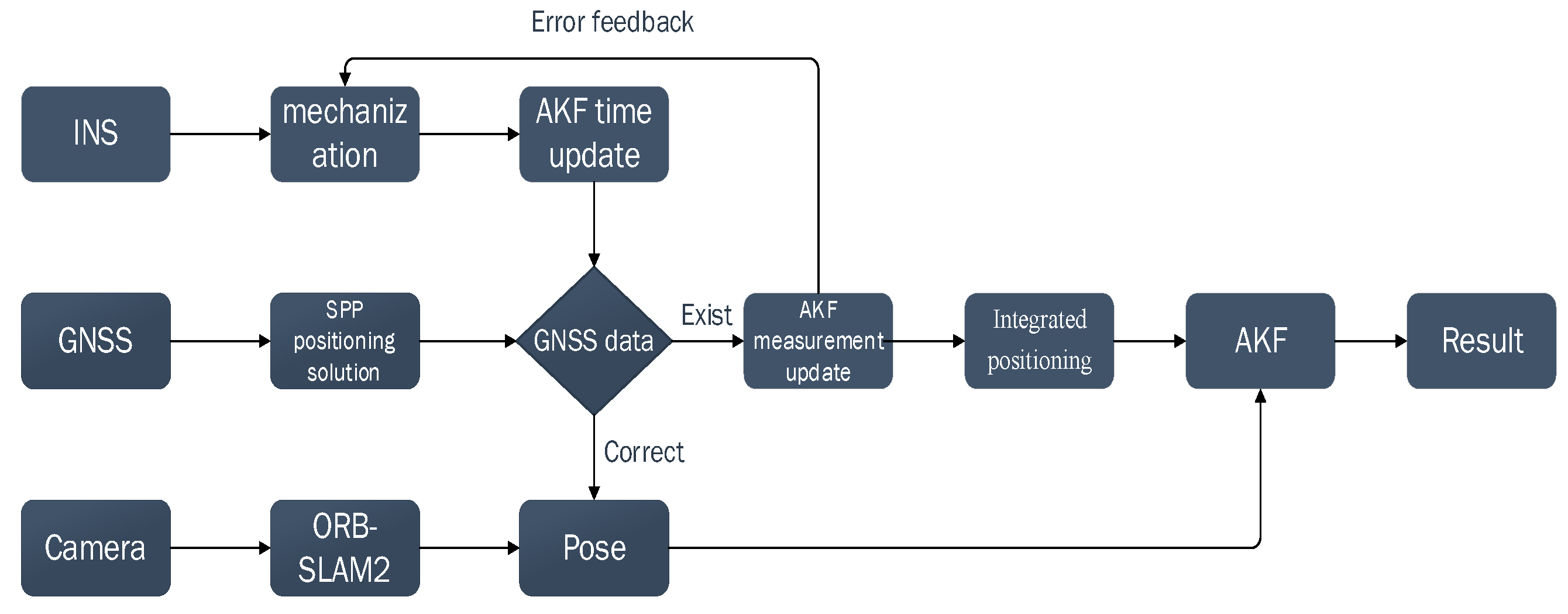

14 November 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

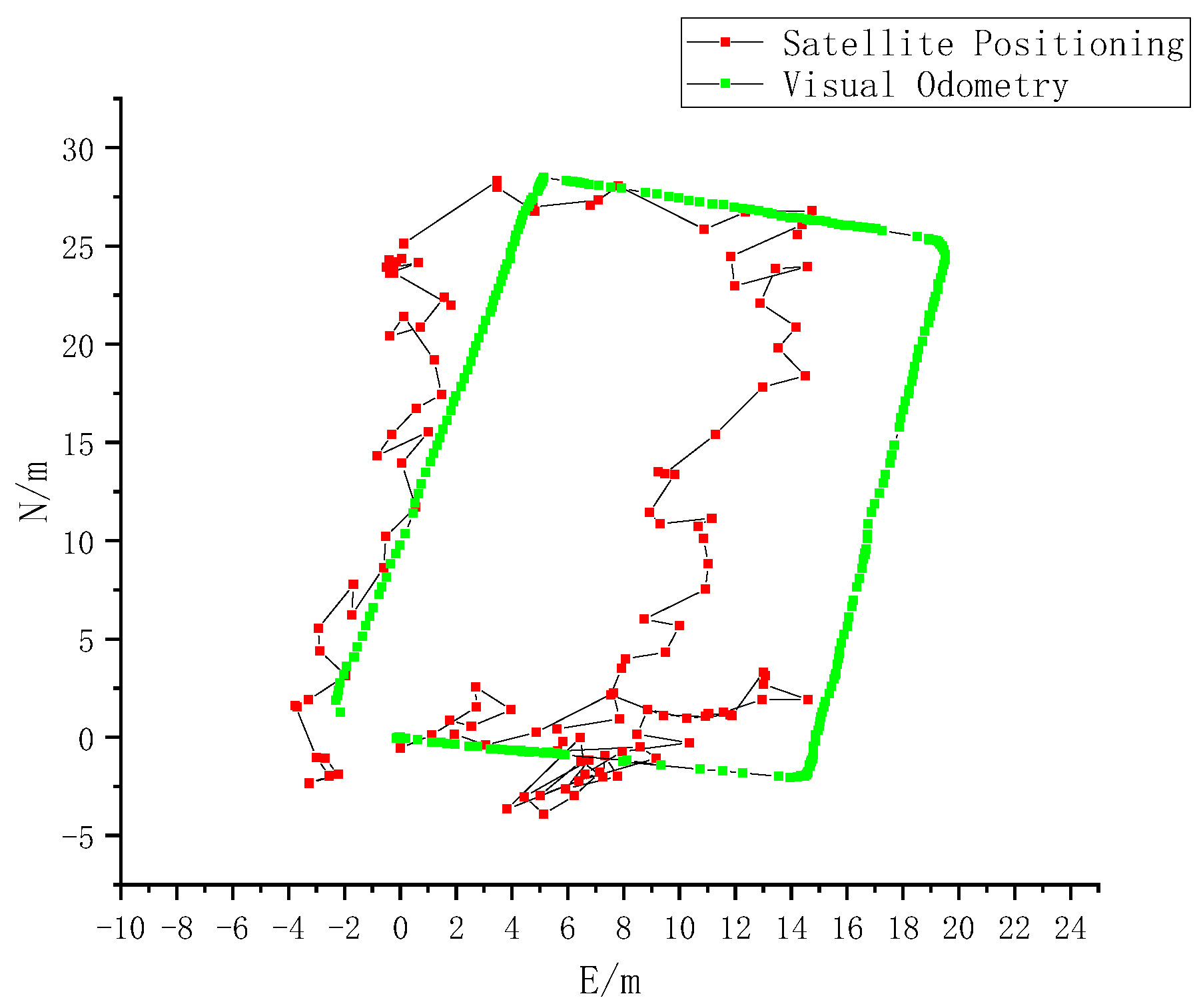

2. Visual Odometry Algorithm

3. Overall Design of GNSS/IMU/Visual Fusion Positioning

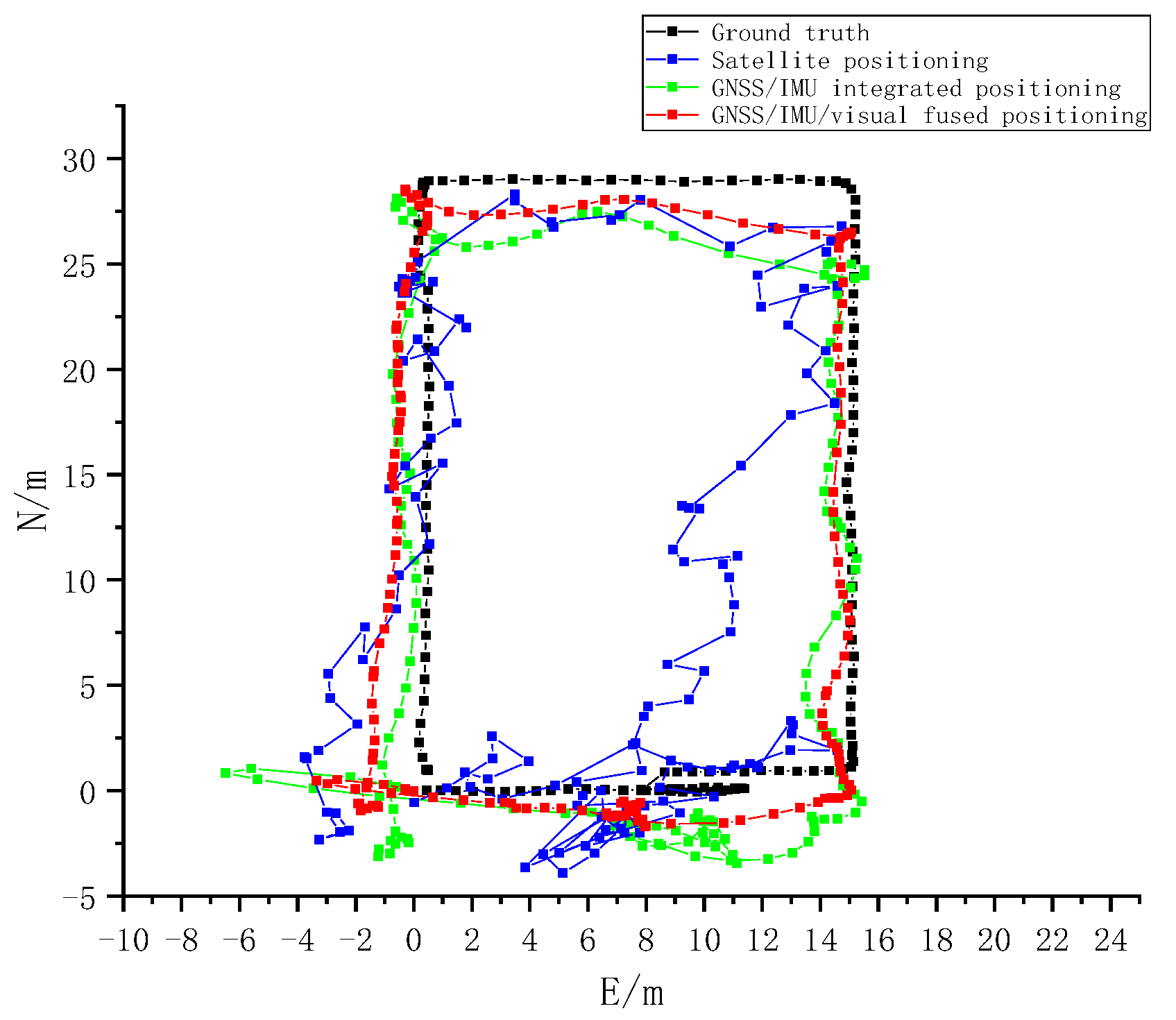

4. Experimental Analysis and Results

4.1. Experimental Analysis

4.2. Experimental Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Z. Peng, Y. Gao, C. Gao, R. Shang, and L. Gan, “Improving smartphone GNSS positioning accuracy using inequality constraints,” Remote Sens., vol. 15, no. 8, pp. 2062-2084, 2023. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhao et al., “Improving performances of GNSS positioning correction using multiview deep reinforcement learning with sparse representa tion,” GPS Solut., vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 98–120, 2024.

- Mohamed A H, Schwarz K P. Adaptive Kalman filtering for INS/GPS[J]. Journal of geodesy, 1999, 73: 193-203.

- Qiu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, L. A Study on Graph Optimization Method for GNSS/IMU Integrated Navigation System Based on Virtual Constraints. Sensors, vol. 24, no. 13, pp. 4419-4436,2024. [CrossRef]

- Yi D et al., “Precise positioning utilizing smartphone GNSS/IMU integration with the combination of Galileo high accuracy service (HAS) corrections and broadcast ephemerides”. GPS Solut., vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 140–155, 2024.

- Beuchert J, Camurri M, Fallon M. Factor graph fusion of raw GNSS sensing with IMU and lidar for precise robot localization without a base station[C]//2023 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA). IEEE, 2023: 8415-8421.

- Yangjie P. Vision and Multi-sensor Fusion BasedMobile Robot Localization in Indoor Environment [D].Zhejiang University,2019.

- FANG Xinqi, FAN Lei. Accuracy analysis of BDS-2/BDS-3 standard point positioning[J]. GNSS World of China, 2020, 45(1): 19-25.

- Xueyuan L,Lili L,Yunyun D,et al. Improved Adaptive Filtering Algorithm for GNSS/SINS Integrated Navigation System[J]. Geomatics and Information Science of Wuhan University,2023,48(01):127-134.

- R. Mur-Artal and J. D. Tardós, "ORB-SLAM2: An Open-Source SLAM System for Monocular, Stereo, and RGB-D Cameras," in IEEE Transactions on Robotics, vol. 33, no. 5, pp. 1255-1262, Oct. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Q. Sun et al., "Efficient Solution to PnP Problem Based on Vision Geometry," in IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters, vol. 9, no. 4, pp. 3100-3107, April 2024. [CrossRef]

- Yan G, Liu P, Li Z, et al. An adaptive Kalman filter based on soft Chi-square test[J]. Navig. Positioning Timing, 2023, 10: 81-86.

| Sensor | Parameter | Technical data |

|---|---|---|

| Bosch BMI 260 | Programmable measurement range | |

| Zero bias | ||

| Sensitivity Error | ||

| Noise density | ||

| Hi 1105 | Eastward Positioning Accuracy(SPP) | |

| Northward Positioning Accuracy(SPP) | ||

| Upward Positioning Accuracy(SPP) | ||

| Xtion | Eastward Positioning Accuracy(After Correction) | |

| Northward Positioning Accuracy(After Correction) | ||

| BD930 | Eastward Positioning Accuracy(Differential Positioning) | |

| Northward Positioning Accuracy(Differential Positioning) |

| Environment | Experimental sequence | Satellite positioning /m | GNSS/IMU integrated positioning /m | GNSS/IMU/visual fused positioning /m |

Accuracy improvement (satellite positioning)/% | Accuracy improvement (integrated positioning)/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unobstructed | First | 2.8945 | 2.3597 | 1.7611 | 39.2 | 25.4 |

| Second | 3.3586 | 1.9683 | 1.4131 | 57.9 | 28.2 | |

| Third | 5.2161 | 3.6935 | 3.147 | 39.7 | 14.8 | |

| Average | 3.8231 | 2.6738 | 2.1071 | 44.9 | 21.2 | |

| Obstructed | Fourth | 6.1739 | 5.4834 | 3.0609 | 50.4 | 44.2 |

| Fifth | 9.5697 | 4.7627 | 4.2512 | 55.6 | 10.7 | |

| Sixth | 6.9074 | 5.5784 | 2.8931 | 58.1 | 48.1 | |

| Average | 7.5503 | 5.2748 | 3.4017 | 54.9 | 35.5 |

| Environment | Experimental sequence | Satellite positioning /m | GNSS/IMU integrated positioning /m | GNSS/IMU/visual fused positioning /m |

Accuracy improvement (satellite positioning)/% | Accuracy improvement (integrated positioning)/% |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unobstructed | First | 4.1966 | 3.9723 | 2.7378 | 34.3 | 31.1 |

| Second | 4.7599 | 2.4307 | 1.8422 | 61.3 | 24.2 | |

| Third | 8.482 | 5.0603 | 4.0758 | 51.9 | 19.5 | |

| Average | 5.8128 | 3.8178 | 2.8853 | 50.4 | 24.4 | |

| Obstructed | Fourth | 9.0871 | 6.7426 | 3.6645 | 59.7 | 45.7 |

| Fifth | 11.6945 | 5.7192 | 4.7475 | 59.4 | 17 | |

| Sixth | 11.2584 | 8.9399 | 5.1084 | 54.6 | 42.9 | |

| Average | 10.68 | 7.1339 | 4.5068 | 57.8 | 36.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).