1. Introduction

The rapid proliferation of information in the digital age has transformed the way individuals consume news and interact with content. While access to diverse perspectives can enhance public discourse, it has also given rise to a troubling surge in misinformation and disinformation. Misinformation, defined as false or misleading information spread without intent to deceive, and disinformation, which is deliberately misleading, pose significant threats to informed decision-making and democratic processes. The consequences of these phenomena are far-reaching, affecting public health, political stability, and societal cohesion [

1].

As the public increasingly relies on online platforms for news consumption, the challenge of distinguishing credible information from false narratives has never been more critical [

2]. Traditional methods of fact-checking are often insufficient to keep pace with the volume and speed of information dissemination. Consequently, there is a pressing need for innovative solutions that leverage advanced technologies to combat misinformation effectively.

In recent years, machine learning techniques, particularly in the domain of natural language processing (NLP), have shown promise in automating the classification of fake news. Models such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers (BERT), and Generative Pre-trained Transformers (GPT) have emerged as powerful tools for analyzing textual data. These models utilize complex algorithms to understand language context, semantics, and patterns, offering new avenues for accurate fake news detection.

This paper aims to investigate the effectiveness of CNN, BERT, and GPT models in classifying fake news, contributing to the ongoing discourse on how technology can enhance information integrity. By comparing these models, we seek to identify best practices for developing robust tools that can aid journalists, policymakers, and the general public in navigating the complex landscape of information. Ultimately, our research aspires to foster a more informed society, equipped with the resources needed to discern truth from falsehood in an increasingly complex media environment.

This research aims to address the pressing issue of misinformation in the news industry through a three-pronged approach:

Evaluating AI Models: We will assess the effectiveness of advanced AI models, particularly Large Language Models (LLMs), in classifying news articles and identifying fake news.

Comparative Performance Analysis: The research will compare the performance of various models both before and after fine-tuning using few-shot learning techniques. This comparison will provide insights into the adaptability and robustness of these models in real-world scenarios.

-

Exploring Unanswered Questions: We aim to investigate critical questions that have yet to be thoroughly examined in previous studies:

Q1: Do traditional NLP and CNN models or LLMs are more accurate in spam detection tasks?

Q2: Among the GPT-4 Omni family, which model performs best prior to fine-tuning?

Q3: After fine-tuning with few-shot learning, which model in the GPT-4 Omni family demonstrates superior performance?

Q4: What is the significance of the costs associated with fine-tuning LLMs, and how do these costs impact performance in the news sector?

Q5: How can LLMs be effectively leveraged to assess fake news, and what transformative effects can they have on the news industry through automated detection and actionable insights?

To achieve these objectives, we will conduct a comprehensive review of existing literature on fake news classification, emphasizing the role of LLMs in the news sector (

Section 2).

Section 3 will detail the materials and methodologies employed in our research, providing transparency in our approach.

Section 4 will present the predictive results for the models analyzed, showcasing their performance both before and after fine-tuning. Finally, in

Section 5, we will engage in an in-depth discussion of our findings, extracting meaningful insights that contribute to the ongoing conversation about misinformation in the media landscape.

2. Literature Review

The exponential growth of social media has amplified both the creation and dissemination of information, making it easier for misleading or false information to proliferate widely and rapidly. This phenomenon has necessitated the development of robust methods to detect fake news and misinformation, as both customer satisfaction and user engagement are heavily influenced by the credibility of shared content [

3]. These aspects are nowadays strongly taken into account by organizations that want to draw the public’s attention to the content they deliver [

4]. Researchers in the field have employed various approaches, predominantly focusing on the extraction and utilization of key features that distinguish false from legitimate content. These features range from linguistic and stylistic elements within the text to metadata and behavioral patterns observable in how content is shared.

This section reviews several feature-based detection approaches that researchers have proposed to address the unique challenges of fake news detection. By examining recent advancements in supervised learning and computational tools, this overview highlights key contributions in feature extraction, dataset development, and classification methods.

2.1. Feature-Based Detection Approaches

Recent studies have increasingly focused on effective methods for detecting fake news, particularly in social media contexts. Reis et al. (2019) [

5] investigate supervised learning techniques, emphasizing the extraction of features from news articles and social media posts. They introduce a novel set of features and evaluate the predictive performance of existing approaches, revealing critical insights into the effectiveness of various features in identifying false information. Their findings underscore practical applications while identifying challenges and opportunities in the field.

Building on this, Pérez-Rosas et al. (2018) [

6] address the challenge of misleading information in accessible media by presenting two novel datasets designed for fake news detection across seven news domains. They detail the collection, annotation, and validation processes and conduct exploratory analyses of linguistic differences between fake and legitimate news. Their comparative experiments demonstrate the advantages of automated methods over manual identification, highlighting the importance of computational tools for addressing misinformation.

Additionally, Al Asaad et al. (2018) [

7] examine the implications of the “post-truth” era, where emotional appeals often overshadow objective facts, leading to misinformation. They propose a machine learning framework that utilizes supervised learning for fake news detection, employing models such as Bag-of-Words and TF-IDF for feature extraction. Their experiments reveal that linear classification with TF-IDF yields the highest accuracy in content classification, while bigram frequency models perform less effectively. This work emphasizes the significance of feature selection and classification strategies in developing effective detection tools.

2.2. Deep Learning Techniques

In contrast to traditional approaches, recent advancements in deep learning have significantly enhanced the capability to detect fake news. Thota et al. (2018) [

8] propose a deep learning approach to fake news detection, underscoring the need for automated systems in light of the increasing prevalence of misinformation. They argue that existing models often treat the problem as a binary classification task, limiting their effectiveness in understanding the nuanced relationships between news articles and their veracity. To address this, the authors present a neural network architecture designed to predict the stance between headlines and article bodies, achieving an accuracy of 94.21%—a 2.5% improvement over previous models.

Furthering this research, Kaliyar et al. (2020) [

9] introduce FNDNet, a deep CNN specifically designed for fake news detection. Unlike traditional methods that rely on hand-crafted features, FNDNet automatically learns discriminative features through multiple hidden layers. Their model, trained and tested on benchmark datasets, achieves an impressive accuracy of 98.36%, demonstrating substantial improvements over existing techniques. This research emphasizes the potential of CNN-based models in enhancing fake news classification and broadening understanding in this domain.

Finally, Yang et al. (2018) [

10] explore the fake news detection challenge with the TI-CNN model, which incorporates both textual and visual information. Recognizing the impact of fake news on public perception, especially during significant events like the 2016 U.S. presidential election, the authors identify useful explicit features from text and images. They also uncover hidden patterns through latent feature extraction via multiple convolutional layers. By integrating explicit and latent features into a unified framework, TI-CNN shows promise in effectively identifying fake news across real-world datasets.

2.3. Multi-Modal and Hybrid Approaches

The surge in fake news on social media necessitates advanced detection systems that can analyze multiple content types. In response, Singhal et al. (2019) [

11] introduce SpotFake, a multi-modal framework designed for effective fake news detection. Unlike existing systems that rely on additional subtasks (such as event discrimination), SpotFake addresses fake news detection directly by leveraging both textual and visual features. The authors utilize advanced language NLP models like BERT for text feature extraction and VGG-19 for image feature extraction. Their experiments on the Twitter and Weibo datasets demonstrate improved performance, surpassing state-of-the-art results by 3.27% and 6.83%, respectively.

Expanding on this concept, Devarajan et al. (2023) [

12] propose an AI-Assisted Deep NLP-Based Approach for detecting fake news from social media users. Recognizing the limitations of traditional content analysis methods, their model incorporates social features and operates across four layers: publisher, social media networking, enabled edge, and cloud. The methodology encompasses data acquisition, information retrieval, NLP-based processing, and deep learning classification. Evaluating the model on datasets such as Buzzface, FakeNewsNet, and Twitter, they report an impressive average accuracy of 99.72% and an F1 score of 98.33%, significantly outperforming existing techniques.

Furthermore, Almarashy et al. (2023) [

13] tackle the challenge of fake news detection by enhancing accuracy through a multi-feature classification model. Their approach extracts global, spatial, and temporal features from text, which are then classified using a fast learning network (FLN). The model consists of two phases: global features are obtained using TF-IDF, spatial features through a CNN, and temporal features via bi-directional long short-term memory (BiLSTM). Experiments conducted on two datasets, ISOT and FA-KES, demonstrate the model’s superiority over previous methods, underscoring the effectiveness of combining diverse feature extraction techniques.

2.4. NLP and Machine Learning

The intersection of NLP and machine learning is pivotal in addressing the challenges of fake news detection. Oshikawa et al. (2020) [

14] provide a comprehensive survey of this domain, highlighting the critical need for automatic detection methods due to the rapid dissemination of misinformation on social media. They systematically review existing datasets, task formulations, and NLP solutions, discussing their potential and limitations. The authors emphasize the distinction between fake news detection and other related tasks, advocating for more refined and practical detection models to enhance effectiveness in combating misinformation.

Complementing this perspective, Mehta et al. (2024) [

15] focus on the efficacy of NLP and supervised learning in classifying fake news articles. Their study demonstrates the application of NLP techniques for feature extraction from textual data, followed by the training of a supervised learning model. Using a dataset of fake news articles, they evaluate model performance through metrics such as accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score. Their results indicate that the approach achieves high accuracy and robustness in classification. Furthermore, feature importance analysis reveals significant contributors to successful classification, providing valuable insights for addressing fake news in online media.

In addition, Madani et al. (2023) [

16] address the growing concern of fake news with a two-phase model that combines NLP and machine learning. The first phase involves extracting both new structural features and established key features from news samples. The second phase employs a hybrid method based on curriculum learning, integrating statistical data and a k-nearest neighbor algorithm to enhance the performance of deep learning models. Their findings demonstrate the model’s superior capability in detecting fake news compared to benchmark models, underscoring the potential of combining innovative feature extraction and advanced machine learning techniques.

2.5. Network-Based Detection Approaches

The rise of fake news has intensified the need for innovative detection methods. Zhou et al. (2019) [

17] propose a network-based pattern-driven approach to fake news detection that transcends traditional content analysis. Their study emphasizes the importance of understanding how fake news propagates through social networks, focusing on the patterns of dissemination, the actors involved, and their interconnections. By applying social psychological theories, the authors present empirical evidence of these patterns, which are analyzed at various network levels—including node, ego, triad, community, and overall network. This comprehensive approach not only enhances feature engineering for fake news detection but also improves the explainability of the detection process. Experiments on real-world data indicate that their method outperforms existing state-of-the-art techniques.

In a complementary vein, Conroy et al. (2015) [

18] explore hybrid detection approaches that combine linguistic cues with network analysis to tackle deception in online news. Their work highlights the potential of integrating multiple methodologies to enhance the effectiveness of fake news detection strategies. By leveraging both content-based and network-based insights, these hybrid approaches offer a more robust framework for identifying and combating misinformation in digital spaces.

2.6. Meta-Analytic and Comparative Studies

Kozik et al. (2024) [

19] conduct a comprehensive survey of state-of-the-art technologies for fake news detection, defining the task as categorizing news along a veracity continuum with a measure of certainty. The authors highlight the challenges posed by the evolving landscape of online news publication, where traditional fact-checking methods struggle against a deluge of content. They categorize veracity assessment methods into two primary types: linguistic cue approaches, often enhanced by machine learning, and network analysis techniques. The paper advocates for a hybrid approach that merges linguistic cues with network-based behavioral data, offering a more nuanced understanding of the factors influencing news veracity. Additionally, the authors propose operational guidelines to facilitate the development of effective fake news detection systems.

Building on these insights, Farhangian et al. (2024) [

20] address the challenges posed by the proliferation of social networks in combating fake news. Their paper revisits definitions of fake news and introduces an updated taxonomy based on four criteria: types of features used, detection perspectives, feature representation methods, and classification approaches. They conduct an extensive empirical study evaluating various feature extraction and classification techniques in terms of accuracy and computational cost. Their findings indicate that optimal feature extraction methods are dataset-dependent, with context-aware models, particularly transformer-based approaches, demonstrating superior performance. The study emphasizes the value of combining multiple feature representation methods and classification algorithms, including classical ones, for improved generalization and efficiency.

2.7. Specialized Detection Models

Alghamdi et al. (2023) [

21] investigate the detection of COVID-19 fake news using transformer-based models, noting the surge of misinformation during the pandemic as a significant public health concern. The paper evaluates various machine learning algorithms and the effectiveness of fine-tuning pre-trained transformer models, such as BERT and COVID-Twitter-BERT (CT-BERT), for this purpose. By integrating downstream neural network structures, including CNN and BiGRU layers, with either frozen or unfrozen parameters, the authors conduct experiments on a real-world COVID-19 fake news dataset. Their findings reveal that augmenting CT-BERT with a BiGRU layer yields a state-of-the-art F1 score of 98%, underscoring the promise of advanced machine learning techniques in combating misinformation.

Similarly, Mahmud et al. (2023) [

22] address concerns surrounding news authenticity in the context of socio-political influences and biased news dissemination. They propose a novel evaluation framework for Bengali language news that integrates blockchain technology, smart contracts, and incremental machine learning. This framework combines machine classification with human expert opinion on a decentralized platform to assess news credibility. The NLP model undergoes continuous training, achieving initial accuracies of 84.94% for training and 84.99% for testing, which improve to 93.75% and 93.80% after nine rounds of incremental training. Their simulation on the Ethereum test network demonstrates the successful implementation of this innovative system, highlighting the potential of leveraging blockchain for enhancing news verification processes.

2.8. Emerging Trends and Novel Techniques

In exploring novel approaches to fake news detection, Yang et al. (2019) [

23] introduce an unsupervised method utilizing a generative model. Acknowledging the rapid dissemination of news on social media and the challenges posed by traditional supervised learning methods, which require extensive labeled datasets, this study employs a Bayesian network to treat news truths and user credibility as latent variables. By utilizing user engagement data to infer the authenticity of news without labeled data, the authors demonstrate a notable improvement over existing unsupervised methods across two datasets.

Building on this idea of early detection, Liu et al. (2020) [

24] developed FNED, a deep neural network designed for the timely identification of fake news on social media. They address the challenge of limited early-stage data by proposing a model with three innovative components: (1) a feature extractor that combines user text responses and profiles, (2) a position-aware attention mechanism to prioritize significant user responses, and (3) a multi-region mean-pooling mechanism for effective feature aggregation. Their experiments show that FNED achieves over 90% accuracy within five minutes of news propagation, significantly outperforming state-of-the-art baselines while requiring only 10% labeled samples.

In a related effort, Wani et al. (2023) [

25] focus on toxic fake news detection in the context of COVID-19 misinformation. Recognizing the detrimental effects of toxic fake news on society, they collect datasets from various social media platforms, labeling instances as toxic or nontoxic through toxicity analysis. The study employs both traditional machine learning techniques (such as linear SVM and random forest) and transformer-based methods (including BERT) for classification. Their findings reveal that the linear SVM method achieved an accuracy of 92% alongside impressive F1, F2, and F0.5 scores. This research indicates that their toxicity-oriented approach effectively distinguishes toxic fake news from non-toxic content, suggesting a promising direction for future investigations into combating misinformation.

2.9. Augmentation and Transfer Learning

Kapusta et al. (2024) [

26] examined text data augmentation techniques for enhancing word embeddings in fake news classification. They highlighted that contemporary language models require large corpora for training to effectively capture semantic relationships. To address the limitations of existing corpora, the authors explored three data augmentation methods: Synonym Replacement, Back Translation, and Reduction of Function Words (FWD). By applying these techniques, they generated diverse versions of a corpus used to train Word2Vec Skip-gram models. Their results showed significant statistical differences in classifier performance between augmented and original corpora, with Back Translation particularly enhancing accuracy in Support Vector and Bernoulli Naive Bayes models. In contrast, FWD improved Logistic Regression, while the original corpus yielded superior results in Random Forest classification. Additionally, an intrinsic evaluation of lexical semantic relations indicated that the Back Translation corpus aligned more closely with established lexical resources, suggesting improvements in understanding specific semantic relationships.

In a different context, Raja et al. (2023) [

27] focused on fake news detection in Dravidian languages using a transfer learning approach with adaptive fine-tuning. Acknowledging the challenge posed by fake news, especially in low-resource languages, they introduced the Dravidian_Fake dataset for fake news classification in Dravidian languages and created multilingual datasets by combining it with the English ISOT dataset. Their approach involved fine-tuning the mBERT and XLM-R pretrained transformer models using adaptive learning strategies. The classification model demonstrated an average accuracy of 93.31% on the Dravidian fake news dataset, outperforming existing methods and proving effective for sentence-level classification in resource-constrained environments.

Liu et al. (2024) [

28] proposed a novel few-shot fake news detection (FS-FND) framework utilizing LLMs. This approach aims to distinguish fake news from real news in low-resource scenarios, leveraging the prior knowledge and in-context learning capabilities of LLMs. They introduced the Dual-perspective Augmented Fake News Detection (DAFND) model, which consists of several modules: a Detection Module identifies keywords in the news, an Investigation Module retrieves relevant information, a Judge Module produces two prediction results, and a Determination Module integrates these results for the final classification. Their extensive experiments on publicly available datasets demonstrated the effectiveness of DAFND, particularly in low-resource settings, highlighting its potential to improve fake news detection.

2.10. Cooperative and Feedback-Based Models

Mallick et al. (2023) [

29] developed a cooperative deep learning model for fake news detection in online social networks. Recognizing the rapid spread of fake news—which often distorts facts for viral purposes and causes significant societal issues such as misinformation and misunderstanding—the authors highlight the limitations of existing detection algorithms, particularly their lack of human engagement. To address this challenge, their proposed model incorporates user feedback to assess news trust levels, with news ranking based on these assessments.

In their framework, lower-ranked news articles undergo further language processing to verify their authenticity, while higher-ranked content is classified as genuine. The model employs a CNN to convert user feedback into rankings within the deep learning architecture. Additionally, negatively rated news articles are reintroduced into the system to refine and retrain the CNN model. The proposed approach achieved a remarkable accuracy rate of 98% for detecting fake news, outperforming many existing language processing-based models.

2.11. Toxic News and Multiclass Classification

Shushkevich et al. (2023) [

30] explore the challenges of fake news detection (FND) in a landscape marked by the easy creation and sharing of information. While traditional FND research often relies on binary classification focused on specific topics, this study expands the framework to a multiclass classification approach that categorizes news articles into true, false, partially false, and other categories. The authors examine the performance of three BERT-based models—SBERT, RoBERTa, and mBERT—while also leveraging ChatGPT-generated synthetic data to enhance class balance in the dataset. They implement a two-step binary classification procedure to further improve detection outcomes. Focusing on the CheckThat! Lab dataset from CLEF-2022, the authors report superior performance relative to existing methods.

Based on the reviewed studies the fight against fake news is a multifaceted challenge that requires continued innovation in detection methodologies. Recent advancements in machine learning, deep learning, and user-centric approaches have laid a solid foundation for more effective detection systems.

3. Materials and Methods

In our literature review, we examined prior studies on AI’s role in fake news detection, revealing a broad range of AI applications currently employed to help news publishers and users access more reliable information. However, these approaches often fall short in adapting to complex linguistic patterns and evolving fake news tactics.

Our study addresses this gap by leveraging the advanced capabilities of LLMs, particularly the latest GPT Omni models and well-established CNN and BERT models in natural language processing. The GPT Omni family includes two models: the high-performance GPT-4o, OpenAI’s flagship for complex, multi-step tasks, and GPT-4o-mini, optimized for efficiency in faster, lightweight tasks. Both are significant upgrades from earlier models, delivering double the speed and reduced cost compared to gpt-4-turbo and gpt-3.5-turbo [

31].

The core goal of our research is to rigorously evaluate these models’ effectiveness in fake news classification to assess their potential for real-world, robust fake news detection. In the first phase, we pre-processed and cleaned our dataset, then used the GPT base models in a zero-shot setup to classify news articles as real or fake. We followed this by fine-tuning CNN, BERT, and both GPT Omni models with few-shot learning and parameter adjustments, prompting them again on the same dataset. Through direct comparison and analysis of the results, our study aims to demonstrate how these cutting-edge models can elevate fake news detection to new standards of accuracy and reliability.

3.1. Dataset Cleaning, Preprocessing, and Splitting

To ensure data quality and reliability, we sourced the “Fake News Classification” dataset from Kaggle, a trusted repository popular among data scientists for its vast array of datasets across different domains. This dataset, known as WELFake, comprises 72,134 news articles—35,028 labeled as real and 37,106 as fake. Created by merging four reputable sources (Kaggle, McIntire, Reuters, and BuzzFeed Political), this comprehensive dataset minimizes the risk of model overfitting and provides a richer foundation for training machine learning models. The dataset includes four columns: Serial Number (starting at 0), Title (the headline of the article), Text (the article content), and Label (0 for fake, 1 for real), spanning a total size of 245.09 MB. With a usability rating of 10, it is well-regarded for its robustness and ease of use, and it’s available under the Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International license, permitting public redistribution and adaptation for non-commercial purposes with proper credit and licensing attribution [

32,

33].

3.1.1. Dataset Preprocessing

To ensure optimal data quality and suitability for our predictive modeling and fine-tuning processes, we followed a structured, multi-step approach to preparing the dataset. Each phase of the preparation process was designed to maximize the data’s relevance and effectiveness for our classification task.

We began with an initial dataset containing four columns: “Serial Number,” “Title,” “Text,” and “Label,” with a class distribution of 37,106 entries labeled as 1 (fake) and 35,028 labeled as 0 (real).

Column Removal: The first step involved removing the “Unnamed: 0” column, which was deemed redundant and irrelevant to our analysis.

Empty Row Removal: We performed a thorough check across the “Title,” “Text,” and “Label” columns to identify and delete any rows with missing values. This ensured that all remaining entries were complete and would contribute fully to the model’s training and validation processes.

Column Merging: We combined the “Title” and “Text” columns into a new consolidated column, named “Text.” This allowed the model to process the headline and article content together, enhancing the context available for classification.

Label Standardization: The “label” column was standardized and renamed “Label” to ensure consistency across our data and streamline integration with our modeling pipeline.

Text Length Restriction: We restricted the “Text” column entries to a maximum length of 2,560 characters. Limiting input size at 2,560 characters is especially effective for training CNN and BERT models, as it provides sufficient contextual information while keeping memory and processing efficiency manageable. After this truncation, the dataset contained 7,573 entries labeled as 1 and 7,313 entries labeled as 0.

Data Standardization: Following the character limit restriction, we standardized the dataset to improve feature consistency and facilitate model convergence. Post-standardization, we re-checked for any empty rows that may have emerged and removed them, resulting in 7,568 entries labeled as 1 and 7,313 entries labeled as 0.

Balanced Sampling: To ensure a balanced dataset, we selected 5,000 entries with stratified sampling based on the “Label” column, yielding 2,500 entries per class (Label 1 and Label 0).

ID Addition: We introduced a unique identifier (ID) for each entry to aid in referencing and error tracking throughout the modeling process.

3.1.2. Dataset Splitting

The dataset was subsequently divided into training, testing, and validation sets, using a stratified approach within the train_test_split function to maintain balanced label distribution. First, we split the data into 80% for training and 20% for testing. From the training set, we further allocated 20% for validation, reserving the remaining 80% for continued training. This approach allowed the training set to effectively support the model’s learning of patterns and relationships within the data, improving its prediction accuracy. The validation set served as a crucial tool for tuning hyperparameters and optimizing model configurations. By monitoring performance on the validation set, we adjusted settings to improve generalization and minimize overfitting risks.

After splitting, the dataset consisted of a test set with 1,000 samples, a training set with 3,200 samples, and a validation set with 800 samples, each evenly balanced across both labels.

3.2. LLM Prompt Engineering

Our objective was to create a prompt that seamlessly integrates with various LLMs, enhancing both the functionality and accessibility of their outputs through well-crafted code. We focused not only on crafting the prompt’s content but also on making the output clear and easy to use, broadening its applicability across different use cases.

To achieve compatibility across multiple LLMs like GPT, Claude, and LLaMA—each with unique strengths and constraints—we first needed a detailed understanding of each model’s characteristics. Designing a prompt that could elicit coherent and consistent responses from all these models, while maintaining ease of use, presented a complex challenge. To address this, we implemented two main prompt engineering strategies tailored to the specific needs of each model [

34]:

Content Independent of Model Architecture: We designed the prompt to be versatile and not dependent on any single model’s framework. This flexibility ensures that it can be applied across different LLMs with minimal adjustment, focusing on clear communication of the task with relevant context and instructions interpretable by any LLM.

Structured Output for Accessibility: Recognizing the importance of usability, we created a response format that aligns with coding and accessibility standards. The output was organized in compliance with the JSON standard, offering a logical, intuitive structure that meets both human readability and machine processing requirements.

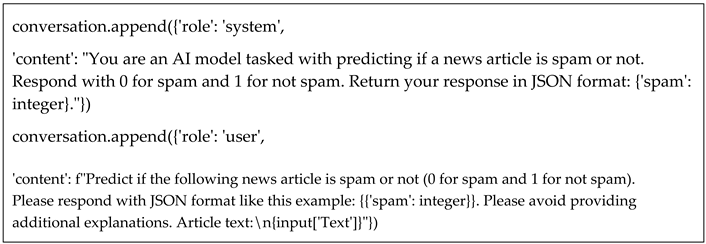

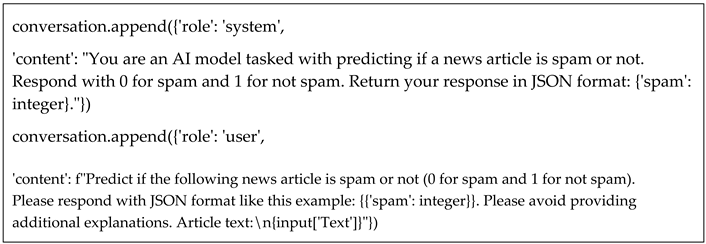

After multiple testing rounds and refinements with different LLMs, we finalized a prompt that consistently produces outputs in the intended format, making it easy for both humans and models to interpret. The final version is illustrated in Listing 1.

|

Listing 1. Model-agnostic prompt. |

|

3.3. Model Deployment, Fine-Tuning, and Predictive Evaluation

The purpose of this study is to assess which of our four models most effectively identifies spam content in the provided article, specifically for classification tasks. By pinpointing the model that best captures the context between words, we aim to create a robust tool for automatically extracting insights from news articles. This tool would empower individuals and organizations to make well-informed decisions, enhance business strategies, and drive improved results and overall success.

To accomplish this, each of the three models was tasked with generating predictions on the test set, both prior to and after fine-tuning through few-shot learning. To ensure fair training conditions, we maintained consistent hyperparameters across all models: a learning rate of 2 × 10⁻⁵, a batch size of 6, and three training epochs, using the Adam optimizer for fine-tuning.

The BERT and CNN models are typically designed to process inputs up to a 512-token limit, roughly equivalent to 2,560 characters. For articles or texts exceeding this length, these models must truncate content to fit within the token constraint, which can lead to the loss of valuable context or critical information from longer texts. While techniques such as chunking (dividing texts into manageable segments) or hierarchical processing (analyzing segments in separate parts and then synthesizing results) are potential solutions for handling longer inputs, these methods add considerable complexity to the processing pipeline [

35]. Specifically, these approaches can require additional layers of interpretation and synthesis to combine segmented outputs accurately, potentially affecting both the efficiency and precision of the results.

In contrast, models like GPT-4ο—especially those configured with extended context windows—can handle significantly longer inputs than 512 tokens. Some versions of GPT-4 can process inputs up to 128,000 tokens [

31], enabling the model to accommodate entire articles, books, or other complex documents in a single pass. This large token capacity allows GPT-4 to capture and integrate information across a much broader context, resulting in a more comprehensive understanding of lengthy texts without requiring chunking or hierarchical processing.

However, these significant differences in token capacity between BERT/CNN models and LLMs such as GPT-4 present challenges when trying to compare their performance directly. To enable a fair comparison, longer articles were removed from the training, validation, and test sets, as described in

Section 3.1.1, ensuring that only articles with a maximum length of 2,560 characters remained. This selection process helped standardize input sizes across models, limiting them to a shared input length, which allowed for a balanced assessment without the need for complex chunking methods or truncation inconsistencies.

Below, we present the deployment strategy for each model, outlining our tailored approach to applying them for spam detection and classification tasks.

3.3.1. GPT Model Deployment and Fine-Tuning

In this phase, we deployed models from the GPT Omni family, specifically the gpt-4o and gpt-4o-mini versions, both in their original (base) forms and after additional training (fine-tuning), to classify news articles as either spam or not spam. Initially, we used the base models in a zero-shot setting, applying the prompt in Listing 1 to make predictions on the test set without any prior fine-tuning. Due to their comprehensive pre-training on extensive datasets, these GPT models can provide relatively accurate predictions even without further training.

To enable interaction between our software and the GPT models, we utilized OpenAI’s official API, which allowed us to submit prompts with article text from the feature column (Text) and receive predictions in JSON format. We saved the predictions from each model in separate columns within the test_set.csv file for easy comparison.

During fine-tuning, these models were further fine-tuned to enhance their accuracy by learning from prompt-response pairs in our training dataset. This additional training enabled the models to better capture subtle patterns and intricacies within the data. We employed a multi-epoch training strategy, which allowed the models to improve iteratively across multiple passes through the data, resulting in more precise predictions and better overall task performance. This iterative approach was key to equipping the models with a nuanced understanding that enhanced their predictive accuracy and insights in the later prediction phase.

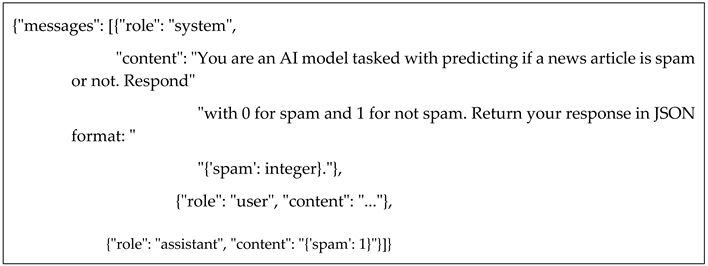

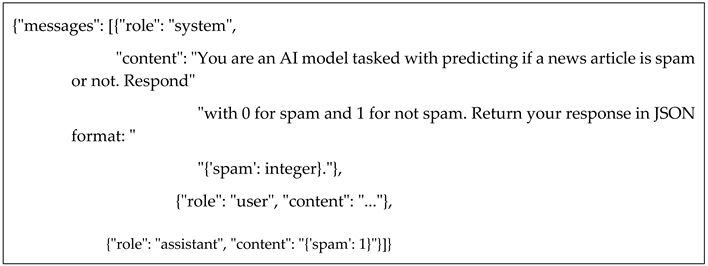

To conduct the fine-tuning, we created two JSONL files that included pairs of prompts and their corresponding completions, as outlined in Listing 2.

|

Listing 2. Prompt and completion pairs – JSONL files. |

|

Following the creation of the validation and train JSONL files, we carried out two fine-tuning tasks by uploading the JSONL files through OpenAI’s user interface. Each fine-tuning task was assigned a unique job ID for tracking: ftjob-i1zEALsbx85pLcGpwLjqz3iL and ftjob-KArKEywkigUn7DTGgZDeEbwp.

The first fine-tuning task was conducted with the gpt-4o model, which was trained on a dataset containing a total of 2,181,792 tokens. The model’s training loss started at 0.8089 and gradually decreased to 0.0000, indicating consistent improvement in fitting the training data. After completing the fine-tuning, the model’s validation loss—a measure of its ability to generalize—stood at 0.0073, demonstrating effective learning across the dataset.

The second task involved fine-tuning the gpt-4o-mini model on the same dataset with 2,181,792 tokens. This model began with an initial training loss of 0.6504, which also dropped to 0.0000 over the course of fine-tuning. Its final validation loss reached 0.0077, reflecting its ability to generalize successfully. These training metrics underscore both models’ suitability for the classification task and their robust learning during fine-tuning.

Once the fine-tuning process was complete, we used both models to generate predictions on the same test set they had initially seen in their base versions. The results from each model were then stored in individual columns within the dataset, allowing for an organized comparison between the fine-tuned and base model predictions.

3.3.2. BERT Model Deployment and Fine-Tuning

In this phase, we focused on training the BERT model, specifically the bert-base-uncased variant, to perform the same classification task that had been previously tackled by the LLMs [

36]. For this, we used the BertForSequenceClassification class from the Hugging Face Transformers library. This variant of BERT incorporates an additional classification head specifically designed for sequence classification tasks. The classification head generally includes a fully connected layer, enabling BERT to convert its output into class probabilities, making it suitable for tasks like spam detection.

The bert-base-uncased model architecture consists of 12 transformer layers, each with 768 hidden units and 12 attention heads, totaling around 110 million parameters. These self-attention mechanisms within BERT are highly effective at capturing contextual dependencies across tokens within an input sequence [

37].

For the prediction phase, we used the pre-trained bert-base-uncased model, which was loaded directly using the from_pretrained method, taking advantage of the model’s robust pre-trained capabilities [

38].

During fine-tuning, we adapted the BERT model for spam classification by training it on labeled data containing labeled news articles, specifying each article as either spam or not spam. This training process was conducted on Google Colab, leveraging the processing power of a Tesla V100-SXM2-16GB GPU [

39]. The dataset was stored on Google Drive, with preprocessing steps that included tokenization via BERT’s tokenizer to prepare the text input in a format suitable for BERT.

Fine-tuning involved careful adjustments to hyperparameters, and we employed the Adaptive Moment Estimation (Adam) optimizer for efficient optimization. Training was executed over three epochs, with progress tracked via the tqdm library to visualize real-time updates [

40]. Within each epoch, backpropagation and optimization were applied to refine the model’s weights, while validation was conducted using the same dataset previously used with the GPT-4o models, ensuring consistency in the evaluation process.

Our fine-tuning approach was methodical, tailored to meet the specific demands of the spam classification task, and aimed at optimizing the model’s performance for this purpose. After fine-tuning, the trained model generated predictions on the same test set used by the GPT-4o models, allowing for a direct comparison.

The full codebase, along with classes for training the BERT and GPT models, as well as metrics for training and validation loss and accuracy, is available in an ipynb notebook hosted on GitHub [

41]. This resource also includes all relevant scripts and detailed documentation to facilitate replication and further experimentation.

3.3.3. CNN Model Deployment and Fine-Tuning

In this phase, we designed a CNN specifically aimed at classifying news articles into spam and non-spam categories. For data manipulation, we employed the Pandas library in Python, which facilitated efficient handling and preprocessing of our datasets. The model development was carried out using TensorFlow’s Keras API, a powerful tool for building and training deep learning models. To streamline our methodology, we created a custom class named CNNTraining, which encompassed essential functions such as hyperparameter initialization—setting the learning rate, number of epochs, batch size, and maximum sequence length—as well as mechanisms for storing training history and performance metrics.

The dataset was sourced from CSV files stored on Google Drive, enabling easy access and management. We employed Keras’s Tokenizer for the text tokenization process, which converted the articles into sequences of integers based on word frequency [

42]. Following tokenization, we applied the pad_sequences function to standardize the input length across all samples, ensuring compatibility with the neural network. The architecture of our CNN included an Embedding layer to transform word indices into dense vector representations, followed by a 1D Convolutional layer designed to extract local features from the text. This was complemented by a Global Max Pooling layer to reduce dimensionality and capture the most salient features, and two Dense layers: one with a ReLU activation function for hidden representations and another with a sigmoid activation function for outputting probabilities of class membership.

The model was compiled using the Adam optimizer, known for its efficiency in training deep learning models, and the binary cross-entropy loss function, which is suitable for binary classification tasks. The training process was executed over three epochs with predefined batch sizes, and validation metrics, such as loss and accuracy, were monitored throughout the training to assess model performance. Upon completion of the training phase, we assessed the model’s performance by utilizing the validation dataset, which allowed us to gauge its accuracy and effectiveness in classifying news articles. Following this evaluation, the trained model was then employed to make predictions on the test set, providing insights into its ability to generalize to unseen data. This two-step evaluation process ensured that we not only understood how well the model performed on the data it was trained on, but also how reliably it could classify new articles, further validating its practical applicability in real-world scenarios.

4. Results

In

Section 3, we undertook a comprehensive examination of the methodology used to implement and fine-tune the LLMs, CNN, and NLP models, thoroughly detailing the processes through which these models were fine-tuned to classify news articles in the test set as either spam or non-spam. This section provides a comparative analysis of the four models, with particular emphasis on their performance metrics prior to and following fine-tuning.

4.1. Overview of Fine-Tuning Metrics

During fine-tuning, we gathered key metrics for each model, including training loss, validation loss, training time, and training cost, all of which are detailed in

Table 1.

Training loss measures the model’s effectiveness during the training phase by capturing the difference between its predictions and actual target values (e.g., 0 for spam and 1 for non-spam); a lower training loss suggests the model is learning effectively from the data.

Conversely, validation loss evaluates the model’s performance on a separate validation set that was not involved in training. This metric is essential for assessing the model’s generalization capability. Ideally, validation loss should decrease as the model improves, but if it starts to increase while training loss continues to decline, this may indicate overfitting [

43].

It is worth noting that direct comparisons of validation and training losses between fine-tuned CNN, NLP models and LLMs can be challenging due to differences in their architectures. However, comparisons among models with similar architectures, such as gpt-4o and gpt-4o-mini, are feasible due to shared structural characteristics and design principles. Since these models are variations within the same foundational framework, the differences observed in training and validation losses likely reflect the scale of the models rather than significant architectural differences. This shared foundation allows for more precise comparisons of their relative performance on similar tasks.

4.2. Model Evaluation Phase

Before we present our findings, it’s crucial to highlight the importance of model evaluation. In the fields of machine learning and natural language processing, assessing models allows us to gauge their effectiveness, make data-driven decisions, and refine tuning to suit particular tasks.

Table 2 provides a summary of each model’s evaluation, featuring essential metrics such as accuracy, recall, and F1-score.

4.2.1. Pre-Fine-Tuning Evaluation

In the initial phase of our research, we deployed two baseline models from the GPT omni family—gpt-4o and gpt-4o-mini—to assess their capabilities in zero-shot spam detection and classification. The results, as summarized in

Table 2, were unexpectedly low, with gpt-4o achieving an accuracy of only 13.9%, while gpt-4o-mini performed marginally better at 14.7%, indicating a minor 0.8% improvement by the smaller model. This unexpected performance gap raised questions about the models’ ability to handle this task without prior training. Initially, we hypothesized that the complexity of the prompt might have contributed to the models’ underperformance. To test this, we created two additional, simplified prompts intended to clarify the task for the models. However, even with these modifications, the classification results remained low, suggesting that prompt complexity was not the primary issue.

This led us to reconsider our expectations for zero-shot capabilities in detecting spam. In this task, distinguishing spam content from legitimate information often requires subtle contextual understanding, which an untrained model might lack. This is particularly relevant given that even human readers sometimes struggle to identify spam without prior knowledge of the topic. This reflection underscored a key limitation in the zero-shot application of LLMs for nuanced classification tasks and pointed to the need for more targeted fine-tuning. Consequently, these findings provided a strong motivation to pursue further fine-tuning of the models, enabling them to develop the specific knowledge and context needed to excel in spam detection tasks.

4.2.2. Post-Fine-Tuning Evaluation

The results following fine-tuning reveal a striking enhancement in model performance, with both fine-tuned gpt-4o (ft:gpt-4o) and its smaller variant, gpt-4o-mini (ft:gpt-4o-mini), achieving a remarkable accuracy of 98.8%. This represents an improvement of 84.9% and 84.1%, respectively, over their base models, underscoring the significant impact of task-specific tuning. The marginal 0.8% advantage of ft:gpt-4o over ft:gpt-4o-mini may be attributed to the larger parameter count in the gpt-4o model, which likely provides a slight edge in capturing subtle distinctions within the data. However, the identical 98.8% accuracy of both models led to further investigation, as a more pronounced difference was anticipated based on their varying parameter sizes. To ensure the accuracy of these results, we conducted multiple rounds of model re-fine-tuning and verification using OpenAI’s panel, each time confirming the same accuracy. This consistency suggests that the specific dataset and task may have enabled gpt-4o-mini to achieve a performance level nearly equal to its larger counterpart, despite the fewer parameters.

These findings have compelling implications for model efficiency in targeted applications. The comparable performance of gpt-4o-mini suggests that, for certain well-defined tasks, smaller models may serve as cost-effective alternatives to larger ones without significant sacrifices in accuracy. This parameter efficiency could benefit scenarios where computational resources or deployment costs are limited.

In contrast, fine-tuned BERT (ft:bert-adam) and CNN (ft:cnn-adam) models produced notably different results. Ft:bert-adam achieved 97.5% accuracy, indicating a strong performance, while ft:bert-cnn lagged significantly with only 58.6% accuracy. This disparity highlights the critical role of model architecture and pretraining in the effectiveness of fine-tuning for specialized tasks. Transformer-based architectures like GPT and BERT have an inherent advantage in NLP and classification tasks due to extensive pretraining on diverse, large-scale datasets. Conversely, CNN models, although highly effective for structured or image-based data, often require a large volume of labeled data to excel in more complex language-based tasks, where subtle semantic patterns are crucial for accurate classification.

The relatively low accuracy of the CNN model in this study may thus be due not to architectural limitations, but rather to an insufficient amount of labeled data to learn and recognize the intricate spam patterns in the task. Unlike pre-trained transformers, which come with a broad foundational understanding from large, generalized datasets, CNNs must acquire such nuance from labeled data specific to the task. In applications like spam detection, where recognizing subtle semantic variations is essential, CNNs likely benefit from substantial labeled datasets to achieve high accuracy, highlighting the importance of dataset size and quality for such architectures.

5. Discussion

In the preceding sections, we explored the spam detection and classification abilities of two LLMs from the same omni family, alongside the BERT model and the CNN. To start, we assessed the base models in a zero-shot framework, where they predicted whether each news article in the test set was spam or non-spam purely based on its content, without any prior task-specific training. Following this, we conducted fine-tuning using few-shot learning and efficient parameter tuning techniques, tailoring each model to a specialized training dataset. Once fine-tuned, the models were re-assessed on the same test set, and their results were analyzed in detail.

In this section, we will leverage these classification outcomes to address the research questions presented in the introduction.

5.1. Evaluating Traditional NLP Models vs. LLMs in Fake News Detection

Research Question 1: Do traditional NLP and CNN models or LLMs are more accurate in spam detection tasks?

Research Statement 1: Fine-tuned LLMs outperform traditional NLP and CNN models in spam detection, achieving near-perfect accuracy.

In the comparative analysis of traditional NLP, CNN models, and LLMs in spam detection tasks, our study underscores several insights about model architecture, pretraining scope, and language comprehension capabilities. Fine-tuned LLMs, especially the GPT-4 Omni models, demonstrate a clear edge over both BERT-based models and CNN architectures, with accuracy levels reaching 98.8% for both GPT-4o and GPT-4o-mini. This near-perfect accuracy suggests that, once fine-tuned, LLMs can detect spam with high precision, making them valuable for tasks requiring fine semantic distinctions. The substantial margin over traditional models is particularly noteworthy because it showcases the advanced language understanding that LLMs bring to complex classification tasks, where subtle contextual cues determine the difference between legitimate content and spam.

The role of pretraining and architecture: Unlike CNNs, which are primarily designed for pattern recognition in structured data like images [

44], LLMs are built with transformer-based architectures that allow for deep attention mechanisms and sequence-based learning. These transformers, pretrained on vast and diverse datasets, are adept at capturing language patterns, idiomatic expressions, and subtle semantic relationships. In spam detection, this translates to a model that can understand nuanced phrasing or stylistic cues typical of spam, even when these cues are subtle or context-dependent.

CNN limitations: The CNN model (ft:cnn_adam) in the study achieved only 58.6% accuracy, which is markedly lower than the transformer-based models. CNNs are effective at identifying repetitive, structured patterns but fall short when tasked with understanding the complexities of human language, especially when spam content relies on nuanced or indirect language. Since CNNs don’t inherently process sequential information as effectively as transformers, they struggle to recognize the sequential and contextual patterns often necessary for distinguishing spam. Furthermore, CNNs require substantial labeled data tailored to the target task to perform well in NLP tasks, given their lack of extensive pretraining on varied textual data [

45].

Comparing BERT and GPT models in spam detection: The BERT model (ft:bert-adam), while achieving a respectable 97.5% accuracy, still fell short of the fine-tuned GPT-4 Omni models. This difference, although minor, may be attributed to the GPT-4 Omni models’ extensive pretraining and perhaps larger scale compared to BERT. Additionally, while both BERT and GPT are transformer-based, GPT models are autoregressive, which means they are trained to predict the next word in a sequence, potentially enhancing their understanding of sentence flow and structure—elements that are crucial for detecting deceptive or misleading language. BERT’s bidirectional nature gives it a slight advantage in understanding context but might limit its proficiency in tasks requiring generation or classification of nuanced language.

The findings suggest that transformer-based models, especially fine-tuned LLMs, are highly effective for spam detection tasks. This holds implications for organizations that require accurate spam filtering, as LLMs can minimize false positives and false negatives more effectively than traditional models. The results also highlight that, while BERT remains a viable option, GPT-based models offer a marginally higher level of performance, likely due to their extensive training on diverse language patterns. On the other hand, CNN models may not be suitable for spam detection due to their architectural limitations and heavy reliance on task-specific labeled data.

5.2. Pre-Fine-Tuning Performance Assessment Within the GPT-4 Omni Family

Research Question 2: Among the GPT-4 Omni family, which model performs best prior to fine-tuning?

Research Statement 2: Prior to fine-tuning, GPT-4 Omni models perform poorly in spam detection, highlighting the necessity of task-specific training.

Our analysis of GPT-4 Omni family models before fine-tuning reveals several key insights about their performance capabilities, limitations, and the nature of zero-shot learning in specialized tasks like spam detection.

Baseline performance and lack of task-specific knowledge: The low accuracy scores of 13.9% for GPT-4o and 14.7% for GPT-4o-mini underscore that both models lack the task-specific knowledge required for effective spam detection in a zero-shot setting. These results suggest that while LLMs have extensive general language understanding, applying this to a nuanced, specialized task like spam detection is challenging without specific tuning. Spam classification often relies on recognizing subtle cues, phrasing patterns, and contextual red flags that are challenging for general-purpose models to identify without tailored training.

The minimal performance gap between models: The 0.8% difference in accuracy between GPT-4o and GPT-4o-mini is marginal, indicating that, prior to fine-tuning, neither model’s scale provides a significant advantage. This close performance suggests that the larger parameter count of GPT-4o does not inherently improve its capability in zero-shot spam detection. The lack of significant disparity in results points to an underlying need for task-specific adaptation that even a larger model cannot overcome in a zero-shot context. This result aligns with findings in NLP research showing that model size alone doesn’t necessarily enhance performance in specialized classification tasks without targeted training.

Challenges of zero-shot spam detection: Spam detection is a complex task that requires not only general language understanding but also the ability to differentiate between legitimate and deceptive communication. Spam content often imitates legitimate language, which makes it difficult to classify correctly without exposure to examples during training [

39]. Zero-shot models, despite their general versatility, lack the fine-grained knowledge to identify these distinctions [

46]. This is especially true in domains like spam detection, where subtle stylistic or structural cues might signal spam, and understanding these cues requires domain-specific data exposure.

Implications of prompt complexity: Attempts to simplify prompts did not result in significant improvements in zero-shot performance, suggesting that prompt engineering alone may not be sufficient to bridge the knowledge gap in specialized tasks [

47]. While prompt optimization can enhance zero-shot performance in some general tasks, its limited impact here implies that spam detection requires more than refined prompting; it needs models that have been trained on data specific to the task. This finding emphasizes that while LLMs are powerful, there are limits to what can be achieved through zero-shot learning alone in cases where the task requires deep contextual familiarity.

5.3. Fine-Tuning Impact on GPT-4 Omni Models with Few-Shot Learning

Research Question 3: After fine-tuning with few-shot learning, which model in the GPT-4 Omni family demonstrates superior performance?

Research Statement 3: After fine-tuning with few-shot learning, GPT-4o and GPT-4o-mini both achieve 98.8% accuracy, with GPT-4o-mini offering a resource-efficient alternative.

Examining the performance of GPT-4o and GPT-4o-mini after fine-tuning with few-shot learning offers insights into the effectiveness of fine-tuning and the strategic advantages of smaller models in targeted applications.

High accuracy and comparable performance: Both GPT-4o and GPT-4o-mini achieved a remarkable accuracy of 98.8% after fine-tuning, suggesting that fine-tuning with few-shot learning equipped both models with a deep understanding of spam-related cues and patterns. This high accuracy indicates that fine-tuning enabled these models to internalize task-specific patterns, transforming general-purpose models into highly competent classifiers. The minimal difference between the two models implies that few-shot learning was sufficient for the task, effectively compensating for any initial knowledge gaps.

The marginal advantage of GPT-4o: The 0.8% advantage of GPT-4o over GPT-4o-mini could be attributed to its larger parameter size, which theoretically allows for more detailed representations of data patterns. The larger model may have a slight edge in capturing subtle distinctions in spam characteristics, such as variations in tone, language, or structure. However, this difference in performance is marginal, implying that while larger models may have more capacity, they don’t always translate that into substantial performance gains for specific tasks, especially when smaller models perform almost as well after fine-tuning.

Fine-tuning efficacy across model sizes: Fine-tuning proved equally effective for both the large and smaller model, suggesting that even a model with fewer parameters, like GPT-4o-mini, can achieve high accuracy when task-specific knowledge is provided through fine-tuning. This reinforces that model scaling is not always necessary for high performance in specialized tasks if effective fine-tuning methods, like few-shot learning, are applied. It also demonstrates that a smaller model, given the right training, can leverage its pre-existing language understanding to learn task-specific requirements efficiently.

Scalability and flexibility in model deployment: The fact that GPT-4o-mini can achieve comparable performance to GPT-4o after fine-tuning suggests that smaller models in the GPT-4 Omni family can be scaled down without sacrificing substantial accuracy. This scalability is particularly beneficial for businesses or developers looking to deploy multiple models across various tasks, as smaller models require less computational power for deployment and can be trained more quickly [

48]. Organizations that need to adapt quickly to new spam detection patterns, for instance, might find GPT-4o-mini advantageous, as it combines high performance with adaptability and cost-effectiveness.

Strategic model selection for application needs: For organizations with stringent accuracy standards in spam detection, both models offer strong choices. However, GPT-4o-mini’s close performance to GPT-4o and its lower computational footprint make it particularly suitable for real-time spam detection systems, mobile applications, or cloud deployments where resource limitations are a concern [

49]. By achieving high accuracy with fewer resources, GPT-4o-mini serves as an example of how model selection can be aligned with specific operational and budgetary needs without compromising on task accuracy [

50].

5.4. Cost-Performance Analysis of Fine-Tuning LLMs for Spam Detection

Research Question 4: What is the significance of the costs associated with fine-tuning LLMs, and how do these costs impact performance in the news sector?

Research Statement 4: Fine-tuning LLMs like GPT-4o incurs high costs, but GPT-4o-mini offers nearly equal performance, making it a cost-effective and sustainable choice for the news sector.

The significance of fine-tuning costs for LLMs is particularly relevant in sectors like news, where budget constraints and scalability are critical. While fine-tuning improves model performance substantially, as seen with GPT-4o and GPT-4o-mini, the associated costs and computational resources required for larger models raise several strategic considerations for the news industry.

Cost-performance trade-offs: Fine-tuning costs can vary dramatically between models, particularly as model size and parameter count increase. While larger models like GPT-4o may offer slight accuracy improvements, these benefits often come with exponentially higher computational costs due to the additional resources needed for training and storage. The results of this study suggest that smaller models like GPT-4o-mini can achieve nearly the same accuracy (98.8%) as larger models, meaning that news organizations can achieve high performance without committing to the costs associated with the largest models. For resource-constrained sectors, this cost-performance balance is essential, allowing organizations to access LLM capabilities without overwhelming financial investments.

Scalability and resource allocation in newsrooms: Many newsrooms, especially smaller or independent ones, operate on limited budgets, making high-cost fine-tuning of large models unfeasible. GPT-4o-mini’s near-parity in performance with GPT-4o after fine-tuning suggests that news organizations could allocate their resources more efficiently by selecting smaller models that require fewer computational resources. By doing so, they can implement robust AI solutions across multiple tasks—such as spam detection, fake news analysis, and content moderation—without incurring prohibitive costs. This approach makes AI-powered solutions more scalable and accessible across diverse newsroom environments.

Sustainability and environmental impacts: Computationally intensive fine-tuning contributes to energy consumption, which has significant environmental implications [

51]. The use of a smaller model like GPT-4o-mini, which requires less power and computational time, aligns with sustainability goals by reducing the carbon footprint associated with model training. For news organizations committed to minimizing their environmental impact, smaller models represent a more sustainable alternative that still delivers high performance. This consideration is becoming increasingly important for industries striving to balance technological advancement with environmental responsibility.

5.5. Harnessing LLMs for Fake News Detection: Impact and Industry Transformation

Research Question 5: How can LLMs be effectively leveraged to assess fake news, and what trans-formative effects can they have on the news industry through automated detection and actionable insights?

Research Statement 5: LLMs can revolutionize fake news detection in the news industry by automating fact-checking, analyzing misinformation patterns, and optimizing journalistic workflows.

Leveraging LLMs like GPT-4o and GPT-4o-mini for fake news assessment offers a significant opportunity for the news industry due to their advanced language understanding and ability to detect subtle nuances in text. These models can automate the fact-checking process, help reduce misinformation, and ultimately enhance public trust in news outlets. Below, we outline the transformative impacts and specific advantages these models could offer to the news sector, along with potential opportunities for future research in this area.

Automated fake news detection and verification: LLMs excel in detecting subtle linguistic cues, including tone, intent, and inconsistencies in phrasing that may indicate misinformation. By analyzing text with high sensitivity to such patterns, these models can flag potentially deceptive articles, posts, or statements [

52]. Automating fake news detection enables near-instant identification of suspicious content, providing journalists and editors with a tool to screen and verify information before it reaches the public. This real-time verification can significantly reduce the spread of fake news by catching it early in the content distribution pipeline.

Analyzing patterns and trends in missinformation: LLMs can analyze large datasets to identify recurring patterns in misinformation [

53]. For instance, they can detect repeated themes, sources, or specific phrasing commonly associated with fake news, which helps newsrooms understand how misinformation is structured and spread. These insights allow media organizations to better understand the origins and propagation mechanisms of fake news, helping them create targeted counter-narratives and education campaigns to inform the public. Moreover, such analysis can assist journalists in investigating and debunking trends in misinformation at their root, reducing their overall impact.

Efficient allocation of journalistic resources: Fake news detection traditionally requires extensive time and effort from journalists to verify sources, cross-check facts, and consult experts. With LLMs automating much of this initial verification process, journalists are free to focus on in-depth investigative reporting or nuanced storytelling. LLMs can serve as frontline tools, handling large volumes of content for preliminary screening and allowing human editors to prioritize the content that truly needs expert analysis [

54]. This efficiency can lead to increased productivity in newsrooms, allowing them to cover more stories and provide richer, more balanced perspectives.

Content moderation and community engagement: News outlets can deploy LLMs to moderate user-generated content, such as comments on articles or social media platforms, where misinformation often proliferates. By filtering out or flagging misleading comments in real-time, LLMs could enable news organizations to maintain respectful and informative discussions around their content. This content moderation creates a safer, more reliable environment for audience engagement, reducing misinformation on news platforms and fostering healthier community discourse [

55].

6. Conclusions

In this study, we evaluated the effectiveness of LLMs, specifically the fine-tuned GPT-4 Omni models, in spam detection for news content. Our results show that fine-tuned GPT-4o and GPT-4o-mini models achieved an impressive 98.8% accuracy, significantly outperforming traditional models like CNN, which lagged at 58.6%. The GPT-4 models, despite their size difference, performed similarly post-fine-tuning, highlighting the cost-effectiveness of smaller models without sacrificing accuracy. This research underscores the importance of fine-tuning for specialized tasks like spam detection, where LLMs excel due to their ability to understand complex language patterns. It also emphasizes the potential for news organizations to leverage LLMs, particularly smaller models, to efficiently combat misinformation, balancing performance with computational cost. Ultimately, our findings contribute to the growing potential of AI in enhancing journalistic integrity and automating spam and fake news detection, offering actionable insights for the future of news media.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.I.R. and N.D.T.; methodology, K.I.R., N.D.T. and D.K.N.; software, K.I.R.; validation, K.I.R. and N.D.T.; formal analysis, K.I.R., N.D.T. and D.K.N.; investigation, K.I.R., N.D.T. and D.K.N.; resources, K.I.R.; data curation, K.I.R.; writing—original draft preparation, K.I.R. and N.D.T.; writing—review and editing, K.I.R., N.D.T. and D.K.N.; visualization, K.I.R.; supervision, D.K.N. and N.D.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting the reported results can be found at ref [

41].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Papageorgiou, E.; Chronis, C.; Varlamis, I.; Himeur, Y. A Survey on the Use of Large Language Models (LLMs) in Fake News. Future Internet 2024, Vol. 16, Page 298 2024, 16, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ShuKai; SlivaAmy; WangSuhang; TangJiliang; LiuHuan Fake News Detection on Social Media. ACM SIGKDD Explorations Newsletter 2017, 19, 22–36. [CrossRef]

- Sakas, D.P.; Reklitis, D.P.; Trivellas, P. Social Media Analytics for Customer Satisfaction Based on User Engagement and Interactions in the Tourism Industry. Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics 2024, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poulopoulos, V.; Vassilakis, C.; Wallace, M.; Antoniou, A.; Lepouras, G. The Effect of Social Media Trending Topics Related to Cultural Venues’ Content. Proceedings - 13th International Workshop on Semantic and Social Media Adaptation and Personalization, SMAP 2018 2018, 7–12. [CrossRef]

- Reis, J.C.S.; Correia, A.; Murai, F.; Veloso, A.; Benevenuto, F.; Cambria, E. Supervised Learning for Fake News Detection. IEEE Intell Syst 2019, 34, 76–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rosas, V.; Kleinberg, B.; Lefevre, A.; Mihalcea, R. Automatic Detection of Fake News. COLING 2018 - 27th International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Proceedings 2017, 3391–3401.

- Al Asaad, B.; Erascu, M. A Tool for Fake News Detection. Proceedings - 2018 20th International Symposium on Symbolic and Numeric Algorithms for Scientific Computing, SYNASC 2018 2018, 379–386. [CrossRef]

- Thota, A.; Tilak, P.; Ahluwalia, S.; Lohia, N. Fake News Detection: A Deep Learning Approach. SMU Data Science Review 2018, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Kaliyar, R.K.; Goswami, A.; Narang, P.; Sinha, S. FNDNet – A Deep Convolutional Neural Network for Fake News Detection. Cogn Syst Res 2020, 61, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zheng, L.; Zhang, J.; Cui, Q.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Yu, P.S. TI-CNN: Convolutional Neural Networks for Fake News Detection. 2018.

- Singhal, S.; Shah, R.R.; Chakraborty, T.; Kumaraguru, P.; Satoh, S. SpotFake: A Multi-Modal Framework for Fake News Detection. Proceedings - 2019 IEEE 5th International Conference on Multimedia Big Data, BigMM 2019 2019, 39–47. [CrossRef]

- Devarajan, G.G.; Nagarajan, S.M.; Amanullah, S.I.; Mary, S.A.S.A.; Bashir, A.K. AI-Assisted Deep NLP-Based Approach for Prediction of Fake News from Social Media Users. IEEE Trans Comput Soc Syst 2024, 11, 4975–4985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almarashy, A.H.J.; Feizi-Derakhshi, M.R.; Salehpour, P. Enhancing Fake News Detection by Multi-Feature Classification. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 139601–139613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oshikawa, R.; Qian, J.; Wang, W.Y. A Survey on Natural Language Processing for Fake News Detection. LREC 2020 - 12th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation, Conference Proceedings 2018, 6086–6093.

- Mehta, D.; Patel, M.; Dangi, A.; Patwa, N.; Patel, Z.; Jain, R.; Shah, P.; Suthar, B. Exploring the Efficacy of Natural Language Processing and Supervised Learning in the Classification of Fake News Articles. Advances in Robotic Technology 2024, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madani, M.; Motameni, H.; Roshani, R. Fake News Detection Using Feature Extraction, Natural Language Processing, Curriculum Learning, and Deep Learning. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219622023500347

2023, 23, 1063-1098, 10.1142/S0219622023500347.

- ZhouXinyi; ZafaraniReza Network-Based Fake News Detection. ACM SIGKDD Explorations Newsletter 2019, 21, 48–60. [CrossRef]

- Conroy, N.J.; Rubin, V.L.; Chen, Y. Automatic Deception Detection: Methods for Finding Fake News. Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology 2015, 52, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozik, R.; Pawlicka, A.; Pawlicki, M.; Choraś, M.; Mazurczyk, W.; Cabaj, K. A Meta-Analysis of State-of-the-Art Automated Fake News Detection Methods. IEEE Trans Comput Soc Syst 2024, 11, 5219–5229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farhangian, F.; Cruz, R.M.O.; Cavalcanti, G.D.C. Fake News Detection: Taxonomy and Comparative Study. Information Fusion 2024, 103, 102140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alghamdi, J.; Lin, Y.; Luo, S. Towards COVID-19 Fake News Detection Using Transformer-Based Models. Knowl Based Syst 2023, 274, 110642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, M.A.I.; Talha Talukder, A.A.; Sultana, A.; Bhuiyan, K.I.A.; Rahman, M.S.; Pranto, T.H.; Rahman, R.M. Toward News Authenticity: Synthesizing Natural Language Processing and Human Expert Opinion to Evaluate News. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 11405–11421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Shu, K.; Wang, S.; Gu, R.; Wu, F.; Liu, H. Unsupervised Fake News Detection on Social Media: A Generative Approach. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence 2019, 33, 5644–5651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Wu, Y.F.B. FNED. ACM Transactions on Information Systems (TOIS) 2020, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wani, M.A.; Elaffendi, M.; Shakil, K.A.; Abuhaimed, I.M.; Nayyar, A.; Hussain, A.; El-Latif, A.A.A. Toxic Fake News Detection and Classification for Combating COVID-19 Misinformation. IEEE Trans Comput Soc Syst 2024, 11, 5101–5118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapusta, J.; Držik, D.; Šteflovič, K.; Nagy, K.S. Text Data Augmentation Techniques for Word Embeddings in Fake News Classification. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 31538–31550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, E.; Soni, B.; Borgohain, S.K. Fake News Detection in Dravidian Languages Using Transfer Learning with Adaptive Finetuning. Eng Appl Artif Intell 2023, 126, 106877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]