Submitted:

24 October 2024

Posted:

25 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

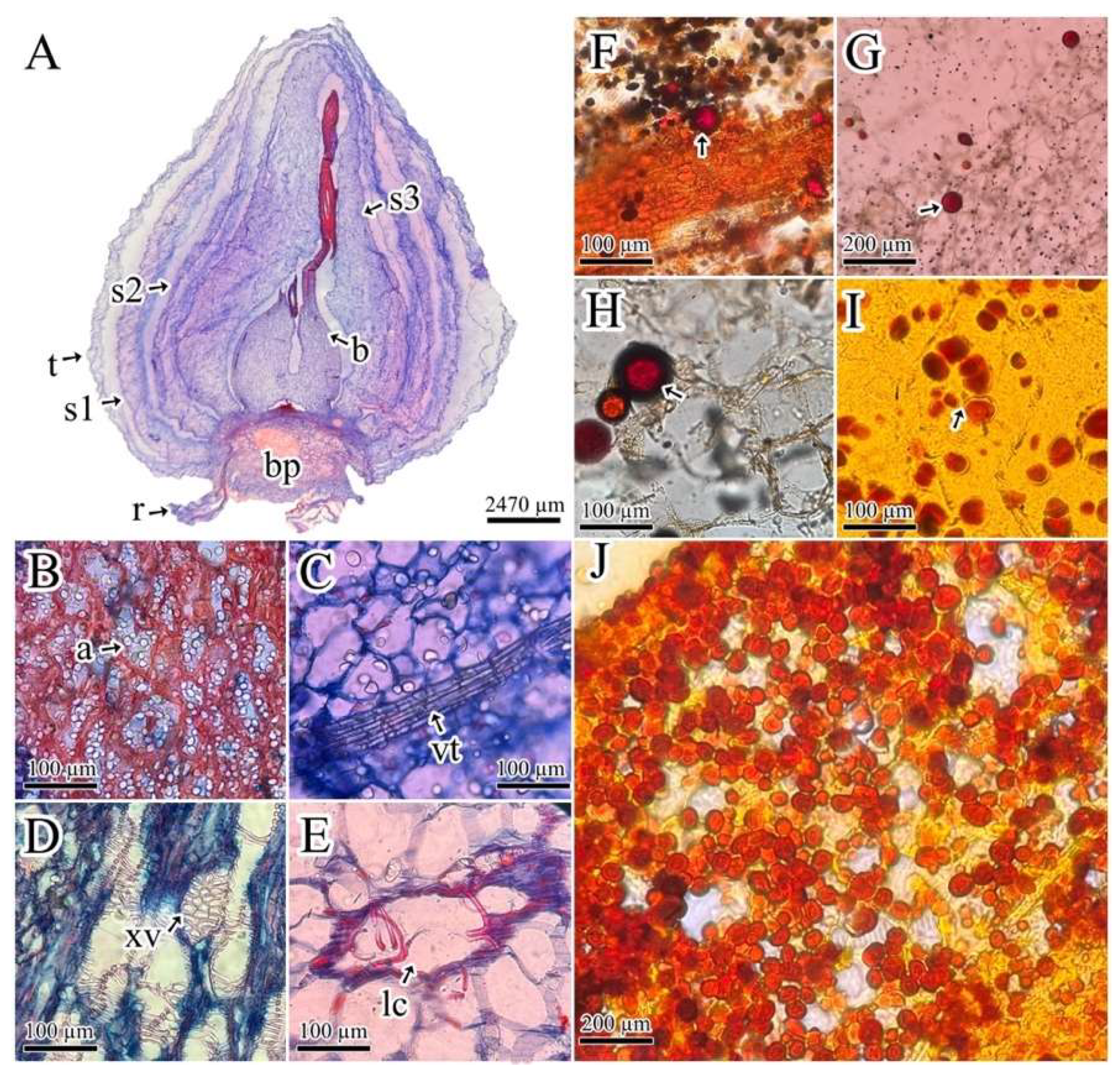

2.1. Histochemical Analysis

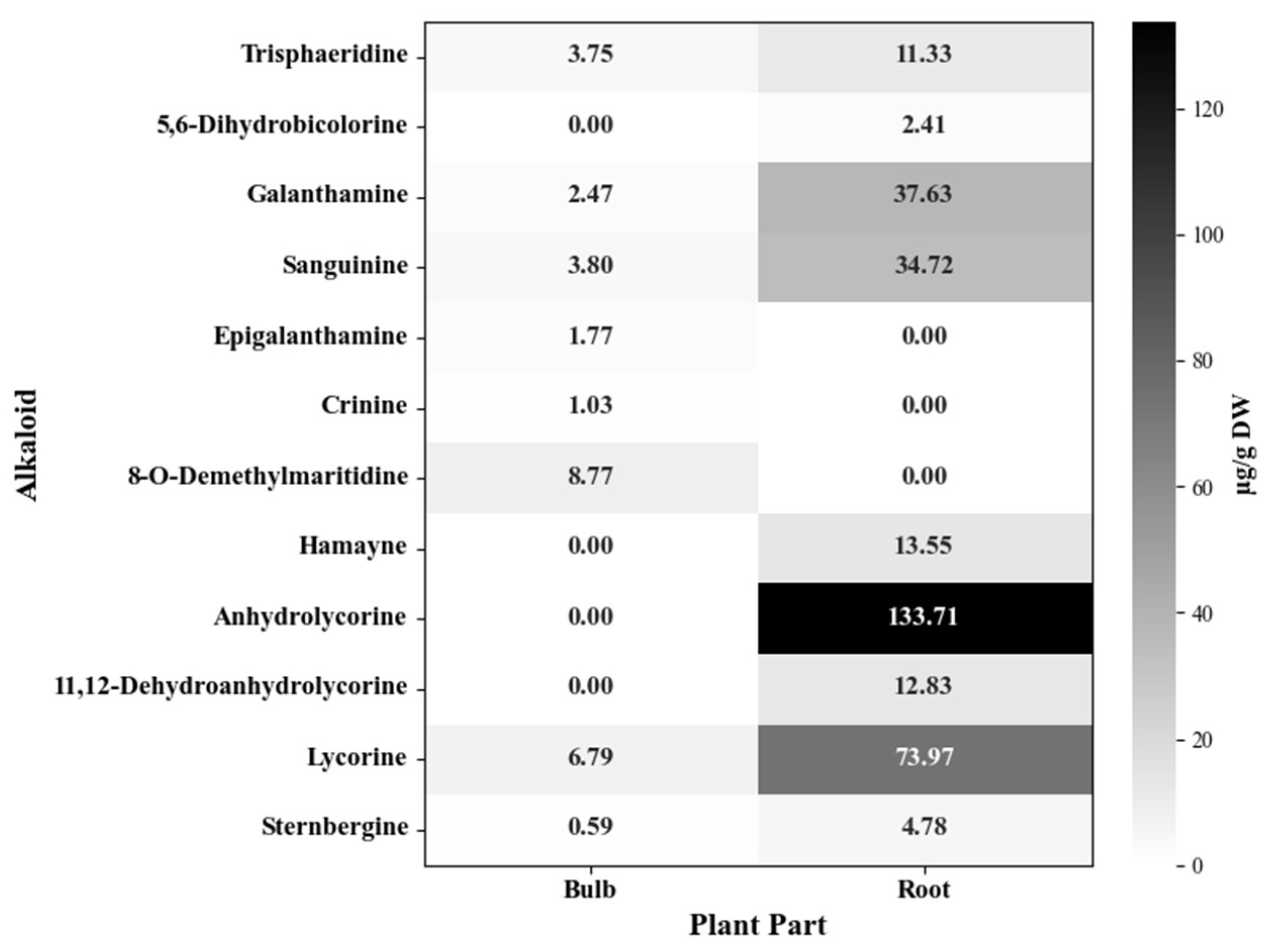

2.2. Chromatographic Analysis of Alkaloids from P. lehmannii

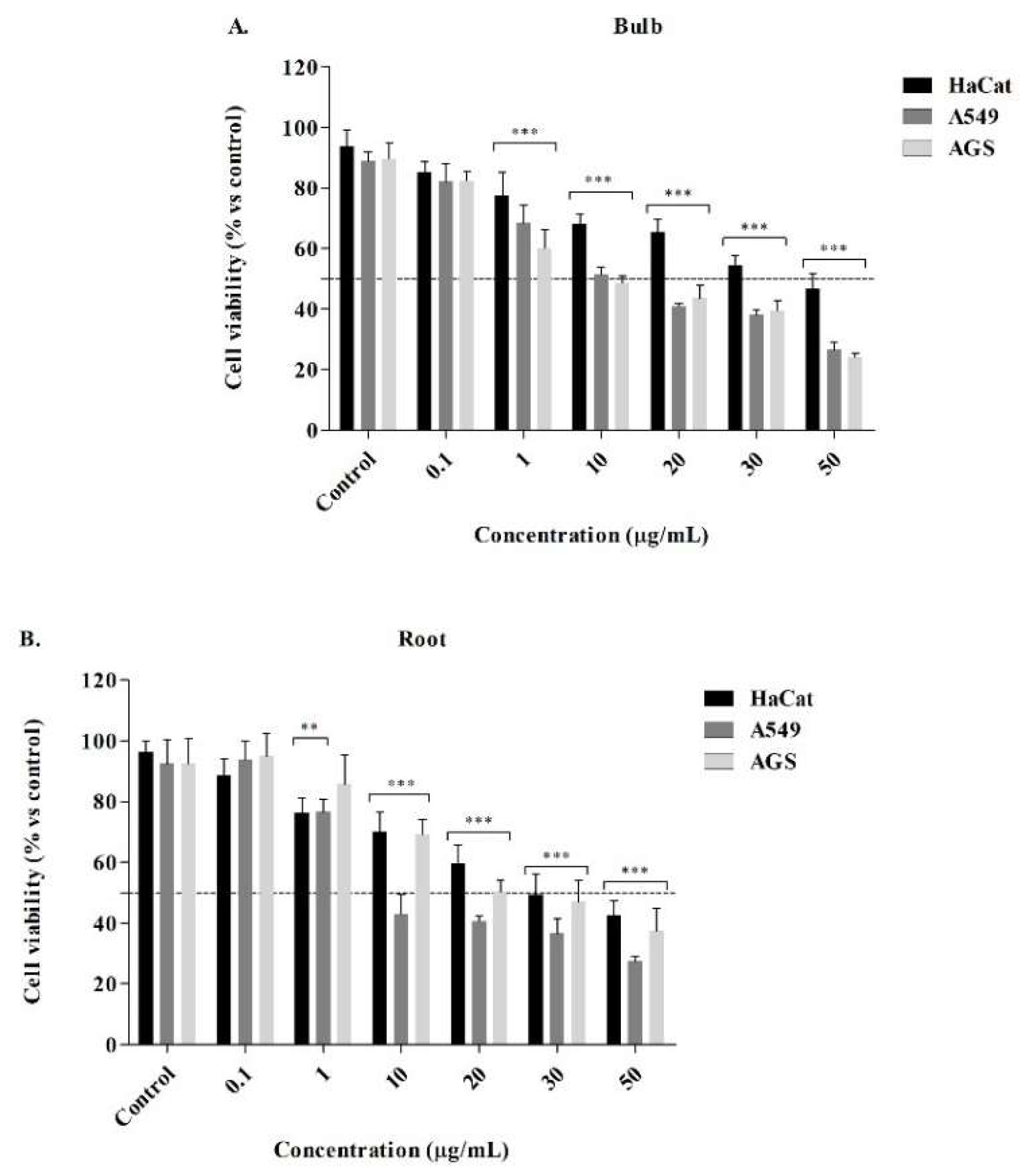

2.3. Cytotoxic Activity from P. lehmannii alkaloids

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Material

4.2. Histochemical Analysis

4.3. Extraction of Alkaloids

4.4. Chromatographic Analysis of Alkaloids

4.5. Determination of the Alkaloid Profile

4.6. Cell Viability of Alkaloid Fraction

4.7. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cahlíková, L.; Kawano, I.; Řezáčová, M.; Blunden, G.; Hulcová, D.; Havelek, R. The Amaryllidaceae alkaloids haemanthamine, haemanthidine and their semisynthetic derivatives as potential drugs. Phytochem. Rev. 2021, 20, 303–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkov, S.; Osorio, E.; Viladomat, F.; Bastida, J. Chemodiversity, chemotaxonomy and chemoecology of Amaryllidaceae alkaloids. In The Alkaloids Chemistry and Biology, Cordell, G.A., Ed.; Elsevier-Academic Press: New York, EEUU, 2020; Volume 83, pp. 113–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, A.; Magne, K.; Massot, S.; Tallini, L.R.; Scopel, M.; Bastida, J.; Ratet, P.; Zuanazzi, J.A.S. Amaryllidaceae alkaloids: identification and partial characterization of montanine production in Rhodophiala bifida plant. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 8471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sierra, K.; de Andrade, J.P.; Tallini, L.R.; Osorio, E.H.; Yañéz, O.; Osorio, M.I.; Oleas, N.H.; García-Beltrán, O.; Borges, W.; Bastida, J.; Osorio, E.; Cortes, N. In vitro and in silico analysis of galanthine from Zephyranthes carinata as an inhibitor of acetylcholinesterase. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 150, 113016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, M. Chapter 4 – Galanthamine from Galanthus and other amaryllidaceae – chemistry and biology based on traditional use. In The Alkaloids Chemistry and Biology; Cordell, G.A., Ed.; Elsevier-Academic Press: New York, EEUU, 2010; Volume 68, pp. 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Havelek, R.; Muthna, D.; Tomsik, P.; Kralovec, K.; Seifrtova, M.; Cahlikova, L.; Hostalkova, A.; Safratova, M.; Perwein, M.; Cermakova, E.; Rezacova, M. Anticancer potential of Amaryllidaceae alkaloids evaluated by screening with a panel of human cells, real-time cellular analysis and Ehrlich tumor-bearing mice. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2017, 275, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo, L.; Bedoya, J.; Cortés, N.; Osorio, E.H.; Gallego, J.C.; Leiva, H.; Castro, D.; Osorio, E. Cytotoxic activity of Amaryllidaceae plants against cancer cells: biotechnological, in vitro, and in silico approaches. Molecules. 2023, 28, 260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trujillo-Chacón, L.M.; Alarcón-Enos, J.E.; Céspedes-Acuña, C.L.; Bustamante, L.; Baeza, M.; López, M.G.; Fernández-Mendívil, C.; Cabezas, F.; Pastene-Navarrete, E.R. Neuroprotective activity of isoquinoline alkaloids from of Chilean Amaryllidaceae plants against oxidative stress-induced cytotoxicity on human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells and mouse hippocampal slice culture. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2019, 132, 110665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzate, F.; Lesmes, M.; Cortés, N.; Varela, S.; Osorio, E. Sinopsis de la familia Amaryllidaceae en Colombia. Biota Colombiana. 2019, 20, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, R.; Tallini, L.R.; Salazar, C.; Osorio, E.H.; Montero, E.; Bastida, J.; Oleas, N.H.; Acosta León, K. Chemical profiling and cholinesterase inhibitory activity of five Phaedranassa Herb. (Amaryllidaceae) species from Ecuador. Molecules 2020, 25, 2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osorio, E.; Berkov, S.; Brun, R.; Codina, C.; Viladomat, F.; Cabezas, F.; Bastida, J. In vitro antiprotozoal activity of alkaloids from Phaedranassa dubia (Amaryllidaceae). Phytochem. Lett. 2010, 3, 161–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León, K.A.; Inca, A.; Tallini, L.R.; Osorio, E.H.; Robles, J.; Bastida, J.; Oleas, N.H. Alkaloids of Phaedranassa dubia (Kunth) J.F. Macbr. and Phaedranassa brevifolia Meerow (Amaryllidaceae) from Ecuador and its cholinesterase-inhibitory activity. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2021, 136, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, N.; Castañeda, C.; Osorio, E.H.; Cardona-Gomez, G.P.; Osorio, E. Amaryllidaceae alkaloids as agents with protective effects against oxidative neural cell injury. Life Sci. 2018, 203, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cortes, N.; Sierra, K.; Alzate, F.; Osorio, E.H.; Osorio, E. Alkaloids of Amaryllidaceae as inhibitors of cholinesterases (AChEs and BChEs): An integrated bioguided study. Phytochem. Anal. 2018, 29, 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, J.J.; Bastida, J.; Viladomat, F.; van Staden, J. Cytotoxic agents of the crinane series of Amaryllidaceae alkaloids. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2012, 7, 1677–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, J.J.; van Staden, J. Cytotoxicity studies of lycorine alkaloids of the Amaryllidaceae. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2014, 9, 1193–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haist, G.; Sidjimova, B.; Yankova-Tsvetkova, E.; Nikolova, M.; Denev, R.; Semerdjieva, I.; Bastida, J.; Berkov, S. Metabolite profiling and histochemical localization of alkaloids in Hippeastrum papilio (Ravena) van Scheepen. J. Plant Physiol. 2024, 296, 154223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bantho, S.; Naidoo, Y.; Dewir, Y.H. The secretory scales of Combretum erythrophyllum (Combretaceae): Micromorphology, ultrastructure and histochemistry. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2020, 131, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanilova, M.I.; Molle, E.D.; Yanev, S.G. Chapter 5 - Galanthamine production by Leucojum aestivum cultures in vitro. In The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Biology; Cordell, G.A., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, EEUU, 2010; Volume 68, pp. 167–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartmańska, A.; Tronina, T.; Popłoński, J.; Milczarek, M.; Filip-Psurska, B.; Wietrzyk, J. Highly cancer selective antiproliferative activity of natural prenylated flavonoids. Molecules. 2018, 23, 2922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wink, M. Ecological roles of alkaloids. In: Modern alkaloids: Structure, isolation, synthesis and biology, Fattorusso, E.; Taglialatela-Scafati, O., Eds.; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA; Weinheim, Germany, 2008, pp. 3–52. [CrossRef]

- Kuntorini, E.M.; Nugroho, L.H. Structural development and bioactive content of red bulb plant (Eleutherine americana); a traditional medicines for local Kalimantan people. Biodiversitas. 2009, 11, 102–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferdausi, A.; Chang, X.; Hall, A.; Jones, M. Galanthamine production in tissue culture and metabolomic study on Amaryllidaceae alkaloids in Narcissus pseudonarcissus cv. Carlton. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 144, 112058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewes-Neto, B.; Gomes-Copeland, K.K.P.; Silveira, D.; Gomes, S.M.; Craesmeyer, J.M.M.; de Castro Nizio, D.A.; Fagg, C.W. Influence of sucrose and activated charcoal on phytochemistry and vegetative growth in Zephyranthes irwiniana (Ravenna) Nic. García (Amaryllidaceae). Plants 2024, 13, 569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubbe, A.; Gude, H.; Verpoorte, R.; Choi, Y.H. Seasonal accumulation of major alkaloids in organs of pharmaceutical crop Narcissus Carlton. Phytochemistry. 2013, 88, 43–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koirala, M.; Karimzadegan, V.; Liyanage, N.S., Mérindol, N.; Desgagné-Penix, I. Biotechnological approaches to optimize the production of Amaryllidaceae alkaloids. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 893. [CrossRef]

- Georgiev, V.; Ivanov, I.; Pavlov, A. Recent progress in Amaryllidaceae biotechnology. Molecules. 2020, 25, 4670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S. Galantamine delivery for Alzheimer’s disease. In Sustainable Agriculture Reviews 43: Pharmaceutical Technology for Natural Products Delivery; Saneja, A., Panda, A.K., Lichtfouse, E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Berlin, Germany, 2020; Volume 1, pp. 131–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petruczynik, A.; Misiurek, J.; Tuzimski, T.; Uszyński, R.; Szymczak, G.; Chernetskyy, M.; Waksmundzka-Hajnos, M. Comparison of different HPLC systems for analysis of galantamine and lycorine in various species of Amaryllidaceae family. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. 2016, 39, 574–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, A.; Desgagné-Penix, I. Metabolic engineering for the production of plant isoquinoline alkaloids. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2016, 14, 1319–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, S.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Chen, W.K.; Wang, R. Fungal endophytes promote the accumulation of Amaryllidaceae alkaloids in Lycoris radiata. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 22, 1421–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkov, S.; Bastida, J.; Sidjimova, B.; Viladomat, F.; Codina, C. Alkaloid diversity in Galanthus elwesii and Galanthus nivalis. Chem. Biodivers. 2011, 8, 115–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, H.; Chahal, S.; Jha, P.; Lekhak, M.M.; Shekhawat, M.S.; Naidoo, D.; Arencibia, A.D.; Ochatt, S.J.; Kumar, V. Harnessing plant biotechnology-based strategies for in vitro galanthamine (GAL) biosynthesis: A potent drug against Alzheimer’s disease. Plant Cell Tiss. Organ Cult. 2022, 149, 81–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sena, S.; Kaur, H.; Kumar, V. Lycorine as a lead molecule in the treatment of cancer and strategies for its biosynthesis using the in vitro culture technique. Phytochem. Rev. 2024, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L. , Wen, K. S., Ruan, X., Zhao, Y. X., Wei, F., & Wang, Q. Response of plant secondary metabolites to environmental factors. Molecules. 2018, 23, 762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, M.; Liang, L.; Xiao, X.; Feng, P.; Ye, M.; Liu, J. Lycorine: A prospective natural lead for anticancer drug discovery. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 107, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, M.; Qu, C.; Gao, O.; Hu, X.; Hong, X. Biological and pharmacological activities of Amaryllidaceae alkaloids. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 16562–16574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Wu, P.; Sun, Y.; Sharopov, F.S.; Yang, Q.; Chen, F.; Wang, P; Liang, Z. Lycorine possesses notable anticancer potentials in on-small cell lung carcinoma cells via blocking Wnt/β-catenin signaling and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2018, 495, 911–921. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Yuan, H.H.; Zhang, X.; Li, Y.P.; Shang, L.Q.; Yin, Z. Novel lycorine derivatives as anticancer agents: synthesis and in vitro biological evaluation. Molecules. 2014, 19, 2469–2480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johansen, D.A. Plant Microtechnique, MeGraw-Hill Book Company: New York, EEUU, 1940; pp. 1–523.

- Ruzin, S. Plant Microtechnique and Microscopy, Oxford University Press: Oxford, England, 1999; pp. 1–322.

- Tolivia, D.; Tolivia, J. Fasga: A new polychromatic method for simultaneous and differential staining of plant tissues. J. Microsc. 1987, 148, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demarco, D. Histochemical analysis of plant secretory structures. In Histochemistry of Single Molecules: Methods and Protocols, Methods in Molecular Biology, Pellicciari, C.; Biggiogera, M., Ed.; Humana: New York, EEUU, 2017; Volume 1560, pp. 313–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brechú-Franco, A.E.; Laguna-Hernández, G.; De-La-Cruz-Chacón, I.; González-Esquinca, A.R. In situ histochemical localization of alkaloids and acetogenins in the endosperm and embryonic axis of Annona macroprophyllata Donn. Sm. seeds during germination. Eur. J. Histochem. 2016, 60, 2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández, G.L.; Franco, A.B.; De-la-Cruz-Chacón, I.; González-Esquinca, A.R. Histochemical detection of acetogenins and storage molecules in the endosperm of Annona macroprophyllata Donn Sm. seeds. Eur. J. Histochem. 2015, 59, 2502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Vásquez, M.R.; Rodríguez-Muñoz, C.A.; Tallini, L.R.; Bastida, J. Alkaloid composition and biological activities of the Amaryllidaceae species Ismene amancaes (Ker Gawl.). Herb. Plants. 2022, 11, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, N.; Sabogal-guaqueta, A.M.; Cardona-Gomez, G.P.; Osorio, E. Neuroprotection and improvement of the histopathological and behavioral impairments in a murine Alzheimer’s model treated with Zephyranthes carinata alkaloids. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 110, 482–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| IC50 (µg/mL) ± SD1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A5492 | SI4 | AGS2 | SI4 | HaCat3 | |

| Bulb | 11.76 ± 0.99 | 4.39 | 8.00 ± 1.35 | 6.45 | 51.59 ± 7.98 |

| Root | 2.59 ± 0.56 | 15.29 | 18.74 ± 1.99 | 2.11 | 39.60 ± 7.86 |

| Lycorine5 | 4.97 ± 0.89 | 7.92 | 4.07 ± 0.21 | 9.68 | 39.39 ± 0.94 |

| Doxorubicin5 | 5.52 ± 0.21 | 0.81 | 5.84 ± 0.65 | 0.77 | 4.48 ± 0.45 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).