Submitted:

11 October 2024

Posted:

11 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Surface Topography and Chemical Composition

3.2. XPS Depth Profiling of Chemical States for Si and Its Dopants

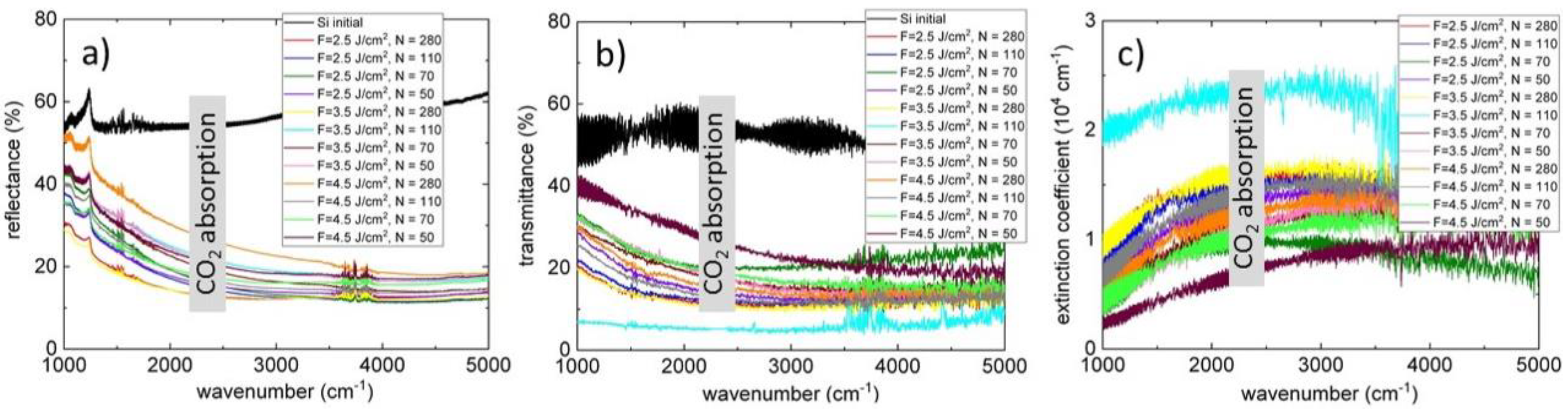

3.3. Raman and FT-IR Spectroscopic Characterization

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huang, C.; FuJ.isawa, S.; de Lima, T.F.; et al. A silicon photonic–electronic neural network for fibre nonlinearity compensation. Nat. Electron. 2021, 4, 837-844. [CrossRef]

- Xiang, C.; J.in, W.; Huang, D.; et al. High-performance silicon photonics using heterogeneous integration. IEEE J. SEL TOP QUANT 2021, 28, 1-15. [CrossRef]

- Carroll, L.; Lee, J. S.; Scarcella, C.; et al. Photonic packaging: transforming silicon photonic integrated circuits into photonic devices. Appl. Sci. 2016, 6, 426. [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; Bu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, D.; Pi X. Hyperdoped silicon: Processing, properties, and devices. J. Semicond. 2022, 43, 093101. [CrossRef]

- Recht, D.; Smith, M.J..; Charnvanichborikarn, S.; et al. Supersaturating silicon with transition metals by ion implantation and pulsed laser melting. J. Appl. Phys. 2013, 114, 124903. [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.Q.; Williams, J..S. Electrical and Optical Doping of Silicon by Pulsed-Laser Melting, Micro. 2021, 2, 1–22. [CrossRef]

- Fu, J..; Yang, D.; Yu X. Hyperdoped crystalline silicon for infrared photodetectors by pulsed laser melting: A review. Phys. Status Solidi. 2022, 219, 2100772. [CrossRef]

- Kudryashov, S. I.; Nguyen, L. V.; Kirilenko, D. A.; et al. Large-scale laser fabrication of antifouling silicon-surface nanosheet arrays via nanoplasmonic ablative self-organization in liquid CS2 tracked by a sulfur dopant. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2018, 1, 2461-2468. [CrossRef]

- Kudryashov, S.; Nastulyavichus, A.; Kirilenko, D.; et al. Mid-Ir-sensitive n/p-J.unction fabricated on p-type Si surface via ultrashort pulse laser n-type hyperdoping and high-temperature annealing. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2021, 3(2), 769-777. [CrossRef]

- Shimabayashi, M.; Kaneko, T.; Sasaki, K. Nitriding of 4H-SiC by irradiation of fourth harmonics of Nd: YAG laser pulses in liquid nitrogen. SN Appl. Sci. 2020, 2, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Sher, M.-J..; Hemme, E.G. Hyperdoped silicon materials: from basic materials properties to sub-bandgap infrared photodetectors. Semicond. Sci. Technol. 2023, 38, 033001. [CrossRef]

- Ferdous, N.; Ertekin, E. Atomic scale origins of sub-band gap optical absorption in goldhyperdoped silicon, AIP Adv. 2018, 8, 055014. [CrossRef]

- Kudryashov, S.; Boldyrev, K.; Nastulyavichus, A.; et al. Near-far IR photoconductivity damping in hyperdoped Si at low temperatures. Optical Materials Express 2021, 11, 3792-3800. [CrossRef]

- Sher, M.-J..; Mazur, E. Intermediate band conduction in femtosecond-laser hyperdoped silicon, Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 105, 032103. [CrossRef]

- Shao, H.; Liang, C.; Zhu, Z.; et al. Hybrid functional studies on impurity-concentration-controlled band engineering of chalcogen-hyperdoped silicon. Appl. Phys. Express 2013, 6, 085801. [CrossRef]

- Ertekin, E.; Winkler, M. T.; Recht, D.; et al. Insulator-to-metal transition in selenium-hyperdoped silicon: observation and origin. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2012, 108, 026401. [CrossRef]

- Vavilov, V.S.; Chelyadinskii, A.R. Impurity ion implantation into silicon single crystals: efficiency and radiation damage. Phys. Usp. 1995, 38, 333–343. [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, S.S.; Pallat, N.O.; Chow, P.K.; et al. Carrier lifetimes in gold–hyperdoped silicon—Influence of dopant incorporation methods and concentration profiles. APL Mater. 2022, 10, 111106. [CrossRef]

- Sher, M.J..; Simmons, C.B.; Krich, J..J..; et al. Picosecond carrier recombination dynamics in chalcogen-hyperdoped silicon. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 105, 053905. [CrossRef]

- Newman, B. K.; Sher, M. J..; Mazur, E.; Buonassisi, T. Reactivation of sub-bandgap absorption in chalcogen-hyperdoped silicon. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2011, 98, 251905. [CrossRef]

- Kudryashov, S.; Nastulyavichus, A.; Krasin, G.; et al. CMOS-compatible direct laser writing of sulfur-ultrahyperdoped silicon: Breakthrough pre-requisite for UV-THz optoelectronic nano/microintegration. Opt. Laser Technol. 2023, 158, 108873. [CrossRef]

- Iori, F.; Degoli, E.; Palummo, M.; Ossicini, S. Novel optoelectronic properties of simultaneously n-and p-doped silicon nanostructures. Superlattice Microst. 2008, 44, 337-347. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.Y.; Zhou, R.H.; Liu, Y.F.; et al. Simulation and typical application of multi-step diffusion method for MEMS device layers. Key Eng. Mat. 2015, 645, 341-346. [CrossRef]

- Kudryashov, S.I.; Nastulyavichus, A.A.; Pryakhina, V.I.; et al. Nanosecond-laser nitridation and nitrogen doping of silicon wafer surface in liquid nitrogen. Ceram. Int. 2024, submitted. [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Ma, X.; Fan, R.; et al. Oxygen precipitation in nitrogen-doped Czochralski silicon. Physica B: Condensed Matter. 1999, 273, 308-311. [CrossRef]

- Akatsuka, M.; Sueoka, K. Pinning effect of punched-out dislocations in carbon-, nitrogen-or boron-doped silicon wafers. J.PN J. Appl. Phys. 2001, 40, 1240. [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Chu, J..; Xu, J..; Que D. Behavior of oxidation-induced stacking faults in annealed Czochralski silicon doped by nitrogen. J. Appl. Phys. 2003, 93, 8926-8929. [CrossRef]

- Ammon, W.; Ho¨lzl, R.; Virbulis, J..; et al. The impact of nitrogen on the defect aggregation in silicon. J. Cryst. Growth. 2001, 226, 19-30. [CrossRef]

- Yu, X. Yang, D.; Hoshikawa K. Investigation of nitrogen behaviors during Czochralski silicon crystal growth. J. Cryst. Growth 2011, 318, 178-182. [CrossRef]

- Masuda, A.; Itoh, K.I.; Matsuda, K.; et al. Y. Nitrogen-doping effects on electrical, optical, and structural properties in hydrogenated amorphous silicon. J. Appl. Phys. 1997, 81, 6729-6737. [CrossRef]

- Sgourou, E. N.; Angeletos, T.; Chroneos, A.; Londos, C.A. Infrared study of defects in nitrogen-doped electron irradiated silicon. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2016, 27, 2054–2061. [CrossRef]

- Platonenko, A.; Gentile, F.S.; Pascale, F.; et al. Nitrogen substitutional defects in silicon. A quantum mechanical investigation of the structural, electronic and vibrational properties. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 20939–20950. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ma, S.X.; Liu, X.; et al. NO2 gas sensor with excellent performance based on thermally modified nitrogen-hyperdoped silicon. Sensors Actuators B: Chem. 2022, 354, 131193. [CrossRef]

- Potsidi, M.S.; Kuganathan, N.; Christopoulos, S.-R. G.; et al. Theoretical investigation of nitrogen-vacancy defects in silicon. AIP Adv. 2022, 12, 025112. [CrossRef]

- Yatsurugi, Y.; Akiyama, N.; Endo, Y.; Nozaki, T. Concentration, solubility, and equilibrium distribution coefficient of nitrogen and oxygen in semiconductor silicon. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1973, 120, 975-979. [CrossRef]

- Belli, M.; Fanciulli, M. Electron Spin–Lattice Relaxation of Substitutional Nitrogen in Silicon: The Role of Disorder and Motional Effects. Nanomaterials 2023, 14, 21. [CrossRef]

- Murakami, K.; Itoh, H.; Takita, K.; Masuda, K. Substitutional nitrogen impurities in pulsed-laser annealed silicon. Appl. Phys. Lett. 1984, 45, 176–178. [CrossRef]

- J.ones, R.; Hahn, I.; Goss, J..P.; et al. Structure and Electronic Properties of Nitrogen Defects in Silicon. Solid State Phenom. 2003, 95-96, 93–98. [CrossRef]

- Dong, X.; Li, N.; Zhu Z. A nitrogen-hyperdoped silicon material formed by femtosecond laser irradiation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 104, 091907. [CrossRef]

- Stein, H.J. Nitrogen in Crystalline Si. MRS Online Proceedings Library 1985, 59, 523–535. [CrossRef]

- Stein, H.J. Nitrogen related donors in silicon. J. Electrochem. Soc. 1987, 134, 2592. [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, S.I. IR spectroscopic study of silicon nitride films grown at a low substrate temperature using very high frequency plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition. World J. Condensed Matter Phys. 2016, 6, 287-293. [CrossRef]

- Mihailescu, I.N.; Litã, A.; Teodorescu, V.S.; et al. Synthesis and deposition of silicon nitride films by laser reactive ablation of silicon in low pressure ammonia: A parametric study. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. A 1996, 14, 1986-1994. [CrossRef]

- Blumenthal, D. J..; Heideman, R.; Geuzebroek, D.; et al. Silicon nitride in silicon photonics. Proceedings of the IEEE 2018, 106, 2209-2231. [CrossRef]

- Barkby, J..; Moro, F.; Perego, M.; et al. Fabrication of nitrogen-hyperdoped silicon by high-pressure gas immersion excimer laser doping. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 19640. [CrossRef]

- Kanaya, K.; Okayama, S. Penetration and energy-loss theory of electrons in solid targets. J. Phys. D. Appl. Phys. 1972, 5, 43. [CrossRef]

- Kudryashov, S.I.; Allen, S.D. Photoacoustic study of KrF laser heating of Si: Implications for laser particle removal. J. Appl. Phys. 2002, 92, 5627-5631. [CrossRef]

- Wada, N.; Solin, S.A.; Wong, J..; Prochazka, S. Raman and IR absorption spectroscopic studies on α, β, and amorphous Si3N4. J. of Non-Cryst. Solids 1981; 43, 7-15. [CrossRef]

- NIST X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy Database. Available online: https://srdata.nist.gov/xps/ElmComposition (accessed 15 J.une 2024).

- Ermolieff, A.; Bernard, P.; Marthon, S.; Camargo da Costa, J. Nitridation of Si (100) made by radio frequency plasma as studied by in situ angular resolved x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy. J. Appl. Phys. 1986, 60, 3162–3166. [CrossRef]

- Peters, S.; Peredkov, S.; Neeb, M.; et al. Size-dependent XPS spectra of small supported Au-clusters. Surf. Sci. 2013, 608, 129–134. [CrossRef]

- Palik, E.D. Handbook of optical constants of solids, 3rd ed.; Academic press: San Diego, USA, 1998; p. 1000.

- Goss, J. P.; Hahn, I.; J.ones, R.; et al. Vibrational modes and electronic properties of nitrogen defects in silicon. Phys. Rev. B 2003, 67, 045206. [CrossRef]

- Viera G., Huet, S.; Boufendi, L. Crystal size and temperature measurements in nanostructured silicon using Raman spectroscopy. J. Appl. Phys. 2001, 90, 4175-4183. [CrossRef]

- Ehara, T. Electron spin resonance study of nitrogen-doped microcrystalline silicon and amorphous silicon. Appl. Surf. Sci. 1997, 113, 126-129. [CrossRef]

- Luongo, J.P. IR study of amorphous silicon nitride films. Appl. Spectrosc. 1984, 38, 195-199. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).