1. Introduction

It has been known for a long time that recreational water has a significant impact on health and wellbeing. Seaports, lakes, rivers, pools, and spas are examples of clean, well-managed recreational water assets that serve as both a community hub and an economic driver for visitors and sporting events. However, more freshwater and coastal beaches are vulnerable to contamination due to untreated sewage overflows, animal excrement from surrounding farms running off, or algae blooms brought on by excessive nutrient loads as a result of increased human activity and climate change [

1,

2].

Regular checks for chemical contaminants and disease-causing microbes during recreational activities, such as swimming, are necessary to prevent any negative impact on human health. Current recreational water quality guidelines, intended to protect swimmers from illness due to exposure to disease-causing microorganisms in these waters, have a solid foundation thanks to scientific studies [

3].

Pool water can transmit several diseases, but the likelihood of acquiring an illness in a well-maintained pool is minimal. Individuals could harbor germs, viruses, and parasites on their skin, both inside and outside. It is possible to introduce certain organisms into the pool water to infect other swimmers. Organisms can enter the body via the oral cavity, nasal passages, auditory canals, and ocular openings. Breaks in the skin can serve as a pathway for transmission as well. Prior to entering a pool, individuals should cleanse their bodies with a shower in order to eliminate any impurities present on their skin. Individuals who have experienced diarrhea within the past 14 days or currently have open wounds are not allowed to swim [

4]. The majority of countries worldwide have implemented legislation or sanitary decrees in accordance with the guidelines set by the World Health Organization (WHO) to enhance the safety of swimming pools [

5].

The chance of experiencing acute gastrointestinal illness (AGI) after swimming ranges from 3% to 8%. The populations at highest risk for acute gastroenteritis (AGI) include children under the age of 5, particularly those who have not received the rotavirus vaccine, as well as elderly individuals and patients with weakened immune systems. Children are especially susceptible to danger due to their increased ingestion of water while swimming, prolonged exposure to water, and engagement in activities in shallow water and sand, which tend to have higher levels of contamination. Individuals who engage in water-intensive sports such as triathlon and kitesurfing are particularly susceptible to increased risk. Even activities that include limited water contact, such as boating and fishing, entail a 40% to 50% higher likelihood of acquiring gastrointestinal infections (AGI) compared to non-water leisure activities. Stool cultures should be performed when there is suspicion of a recreational water disease, and the clinical dehydration scale is a valuable tool for evaluating the treatment requirements of affected youngsters. Water quality is regularly monitored to prevent any negative impact on human health during recreational activities like swimming or boating. This includes the monitoring of chemical contaminants and disease-causing bacteria. This study establishes a robust scientific basis for current guidelines on recreational water quality, which aim to safeguard swimmers from getting sick as a result of being exposed to disease-causing microorganisms in recreational waters [

6].

From 2000 to 2014, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) received reports of 493 outbreaks associated with treated recreational water. These outbreaks led to 27,219 instances of illnesses and 8 fatalities.1 Further instances of outbreaks have been documented in relation to untreated freshwater and seawater. Pediatricians must be prepared to identify and treat these infections and provide suitable guidance to families regarding clean water practices [

7,

8].

Even though the COVID-19 disease does not appear to be transmissible to humans by fresh or marine water (lakes, rivers, ponds, and seas), hot tubs, splash pads, or any other type of pool or spa water operators and managers must ensure that pools, hot tubs, and splash pads are properly disinfected with chlorine or bromine should render the virus inactive [

9,

10,

11]. In every case where a swimming pool is used, the water must be disinfected, and stringent health precautions must be followed. The appropriate application of these precautions is ensured by measuring the amount of residual chlorine in the water. This is done chromatographically using the N, N-diethyl-p-phenylenediamine method, and the results must strictly fall between 0.4 and 0.7 mg/l. The WHO's guidelines state that in order to guard against SARS-CoV-2, the residual chlorine content of tank water should be between 1-3 mg/l for swimming pools and up to 5 mg/l for water massage tanks [

4,

8,

12]. Recreational water diseases (RWIs) result from the presence of microorganisms and chemical substances in the water that we swim or engage in recreational activities in, such as swimming pools, water parks, hot tubs, splash pads, lakes, rivers, or oceans. The transmission of the disease occurs by ingestion, inhalation, or direct contact with water that has been polluted [

5].

The objective of this study was to assess the enforcement of extremely strict COVID-19 health protocols in the hotel industry in Crete, Greece, during the summer tourist seasons of 2020-2022, focusing on microbiological hygiene and physicochemical water parameters, and to compare these findings with the 2019 tourist season (pre-COVID-19).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inspections: Sample Collection

A total of 23 pools from randomly selected hotels in the region of Crete inspected, from which a total of 708 water samples were collected from pools and analyzed for microbiological indicators according to the national legislation and public health organization directives. The 175 samples were collected and analyzed in the tourist season of 2019, 151 samples in the tourist season of 2020, 222 samples in the tourist season of 2021, 160 samples in the tourist season of 2022, in the context of the self-control of the hotel units. The staff of the Food, Microbiology, Water and Environment Department of Clinical Microbiology and Microbial Pathogenesis, School of Medicine, University of Crete, collected all samples. According to data protection regulations, the laboratory keeps a database containing all the annual results of the chemical and microbiological analyses, as well as measurements of the physicochemical parameters of the water for each hotel. This allowed the authors to conduct the current study by comparing data collected before and after the COVID-19 pandemic.

The samples were collected in accordance with ISO 19458:2006 [

9]. Specifically, the sampling of recreational water was performed using the following methodology: Two samples were obtained from the swimming pools and placed in bottles of 500 ml each. The samples were obtained from the pool's basin at points near outlets (skimmers or gutters). Sodium thiosulfate (Na

2S

2O

3) was used in an 80 mg/l water solution. The sampling points selected were the point of entry into the tank, the point of exit of water, the middle of the tank (20 cm below the water's surface), and before and after the filters. Finally, the samples were labeled and temporarily stored in a cold box at a temperature of up to 5(±3) ˚C, protected from direct light, before being delivered to the laboratory immediately after sampling (not >24 h).

2.2. Detection of Coliform Bacteria, E. coli and P. aeruginosa

Escherichia Coli (E. coli) and coliform bacteria were counted in accordance with ISO 9308-1:2014 AMD 1:2016. Membrane filtration served as the foundation for the procedure, which also included chromogenic medium cultivation and a final computation of the desired microorganism count in the water sample. Waters with low bacterial populations, which will produce <80 colonies on the CCA chromogenic substrate, were very well suited for this approach. These samples included treated water, swimming pool disinfected water, and drinking water. Certain β-D-glucuronidase-negative strains of Escherichia coli, such O157, will not be identified as Escherichia coli. On this chromogenic agar, they will manifest as coliforms if they are β-D-galactosidase-positive.

Enterobacteriaceae, which includes coliforms, are known to express β-D-galactosidase. Enterobacteriaceae, which includes E. coli, express both β-D-glucuronidase and β-D-galactosidase. The process involved passing a predetermined amount of water (often 100 ml) through a sterile membrane filter with a 0.45 µm pore size that could hold microorganisms. After the filter was put, it was incubated at 36± 2˚C for 21 to 24 hours on a solid chromogenic substrate (Coliform Chromocult Agar, Chromocult Coliform Agar, 1.10426, Merck Millipore). Next, colonies that showed positive results for β-D-galactosidase (pink-red colonies) were counted as potential non-E. coli coliforms. Negative oxidase response evidence was used to validate questionable colonies to prevent false-positive outcomes. Furthermore, colonies that were positive for β-D-glucuronidase and β-D-galactosidase (dark blue-violet) were counted as E. coli. Oxidase negative pink-red colonies and dark blue-violet colonies added up to total coliforms.

Filtration was used to concentrate the water samples, which were then re-suspended in distilled deionized water. A 200 µl volume of the suspension was applied to glycine vancomycin poly-myxin cycloheximide (GVPC), bioMérieux's BCYE sans cysteine, and buffered charcoal yeast extract (BCYE). Petri dishes: I immediately after filtering; ii) after 30 minutes of incubation at 50˚C; iii) after adding an acid buffer (0.2 mol/l HCl solution, pH 2.2) and waiting at least 15 minutes. The method's detection limit was 50 CFU/l. For ten days, the inoculation plates were incubated at 36±1˚C in 2.5% CO2 with higher humidity. Random selection was used to choose suspected colonies for subculturing on BCYE without cysteine, BCYE, and GVPC agar.

The laboratory employed membrane filtering methodology in accordance with ISO 16266:2006 for P. aeruginosa detection and enumeration. An accurately measured 100 milliliter water sample, or a diluted version of the sample, was passed through a 0.45 micrometer sterile membrane filter. The selective medium was covered with the membrane filter, and it was incubated for 44±4 hours at 36±2˚C according to the medium's instructions.

After incubation, the number of distinctive colonies on the membrane filter was counted to determine the number of presumed P. aeruginosa. Although certain fluorescing or reddish-brown colonies need confirmation, colonies that produced phycocyanin were formerly thought to be authentic P. aeruginosa colonies. The membrane filter is used to create subcultures of colonies that need to be confirmed on nutrient agar plates. After being incubated at 36±2˚C for 22±2 hours, non-fluorescent cultures were subjected to an oxidase reaction test, and cultures that tested positive for oxidase were evaluated for fluorescence and ammonia production from acetamide. The capacity of initially fluorescent cultures to generate ammonia from acetamide was examined. We determined the number of confirmed P. aeruginosa colonies in the volume of filtered water by counting the characteristic colonies on the membranes and accounting for the percentage of confirmatory tests conducted.

2.3. Data Collection

During the sample process, physicochemical parameters including water temperature, pH level and residual chlorine concentration were documented. The inspections were conducted with a checklist that was designed to gather specific information, including the name and address of the building, the kind of hot water production system, the water disinfection system, the frequency and type of maintenance and cleaning of the water supply system, as well as the number of rooms and beds.

On the sampling forms, we noted essential details such as the date and time of the sampling, the purpose of the sampling, and the names and capacities of the samplers. Descriptive data, including the building's location, weather conditions, precise sampling point, parameters for analysis, disinfectants used, and circumstances for sample transportation to the laboratory (such as refrigeration), were also gathered.

Measurements were recorded using calibrated instruments, including temperature, residual chlorine and pH. More precisely, the temperatures were assessed by employing a calibrated thermometer positioned at the center of the swimming pool. The levels of free chlorine and pH were determined using a calibrated portable photometer that operates on a microprocessor. The specimens were gathered in aseptic 1-liter receptacles with a sufficient quantity of Na2S2O3 (20 mg) to counteract any chlorine or other oxidizing biocides.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

The statistical analyses were performed using the PSPP 2.0.1 software, which is freely available under the GNU General Public License. Additionally, the Epi-Info 2000 Build 7.2.6 free software from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA, USA, and the free electronic version of the MedCalc Relative Risk Statistical Calculation Software (19) were also utilized. The relative risk (RR) was computed using a 95% confidence interval (CI). A significance level of P<0.05 was used to determine if there was a statistically meaningful difference. The linear correlation was calculated using Pearson's coefficient (r). The results were considered statistically significant when the p value was <0.05 and highly significant when the p value was <0.0001.

4. Discussion

In March 2020, acknowledging the necessity to strengthen global resources to combat the pandemic, numerous states consulted the WHO to urge the establishment of a global repository for intellectual property pertaining to technology for the detection, prevention, control, and treatment of COVID-19 [

15]. According to US CDC there was no existing evidence suggesting that the SARS-CoV-2 virus can be transmitted to individuals via water in swimming pools, hot tubs, splash pads, or through freshwater or marine environments, including lakes, rivers, ponds, and seas. Proper water disinfection using chlorine or bromine should effectively inactivate the virus in pools, hot tubs, and splash pads. Operators and managers of public pools, hot tubs, splash pads, or freshwater or marine beaches must adhere to federal, state, local, tribal, or territorial directives and collaborate with local health authorities [

16].

Most countries around the world implemented stricter regulations and planned additional measures to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 in recreational aquatic environments. To this regard, the Greek Tourism Ministry has mandated the implementation of health protocols in all hotels nationwide to ensure their secure reopening and operation after the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic.

In the design, building, and operation of swimming pools, it was established an implementation of preventative measures to mitigate the transmission of diseases and guarantee user’s comfort. During pool operation, disinfection and filtration of the water is essential for eliminating microorganisms and removing impurities, respectively (22). Chlorine- or bromine-based disinfectants are utilized in many swimming pools to inhibit microbial growth. Nonetheless, chlorination is the predominant procedure employed (23). Consequently, checking for free chlorine and sustaining appropriate chlorine levels in swimming pools is a critical safety measure.

The primary source of recreational water contamination, and consequently the most significant public health concern, is from microorganisms present in polluted faeces and vomits. The quality of pool water is influenced by various elements, including water pollution levels, the number of bathers and their behavior, the ventilation system (for enclosed pools), as well as the temperature of both water and air, and the water circulation system. The outcomes of physicochemical analyses of pool water quality parameters, conducted by health inspection authorities, are regarded as supplementary to the evaluation of its contamination level (27). The outcomes of microbiological analyses and the evaluation of the facility's sanitary state are essential. Prior to the onset of the pandemic, more strict criteria were established for water treatment and the maintenance of quality in swimming pools (25). Water must be filtered and disinfected, conforming to the physical, chemical, and microbiological standards established by Greek legislation. The current legislation stipulates the necessary monitoring frequencies for physicochemical and microbiological indicators, as well as the protocols for closing and maintaining the tank in instances of non-compliance (26).

Disinfectants introduced into water must eliminate or deactivate bacteria while preserving the integrity of swimmers' skin, eyes, and mucous membranes. Chlorine is frequently utilized because of its economical nature, ease of application, and safety. Cleaning and disinfection protocols must be complemented by stringent hygiene and conduct regulations for bathers, together with a cap on the number of bathers permitted (10).

Chlorine was employed by the operators of the examined swimming pools as the primary disinfection strategy. It is shown that elevated residual chlorine levels, mandated by health guidelines, significantly impacted the microbial cleanliness of the analyzed swimming pool water. More specifically, water samples measured with incompatible free chlorine levels, water temperatures above 25 ˚C and pH values over 7.8, were found likewise beyond regulatory limitations for bacteria, as indicated in similar studies (24-26).

In this study, the Physicochemical characteristics of water samples for the operating years 2020, 2021 and 2022 in swimming pools, which correspond to the COVID-19 era, are compared to the reference year 2019, which describes the pre-COVID19 status.

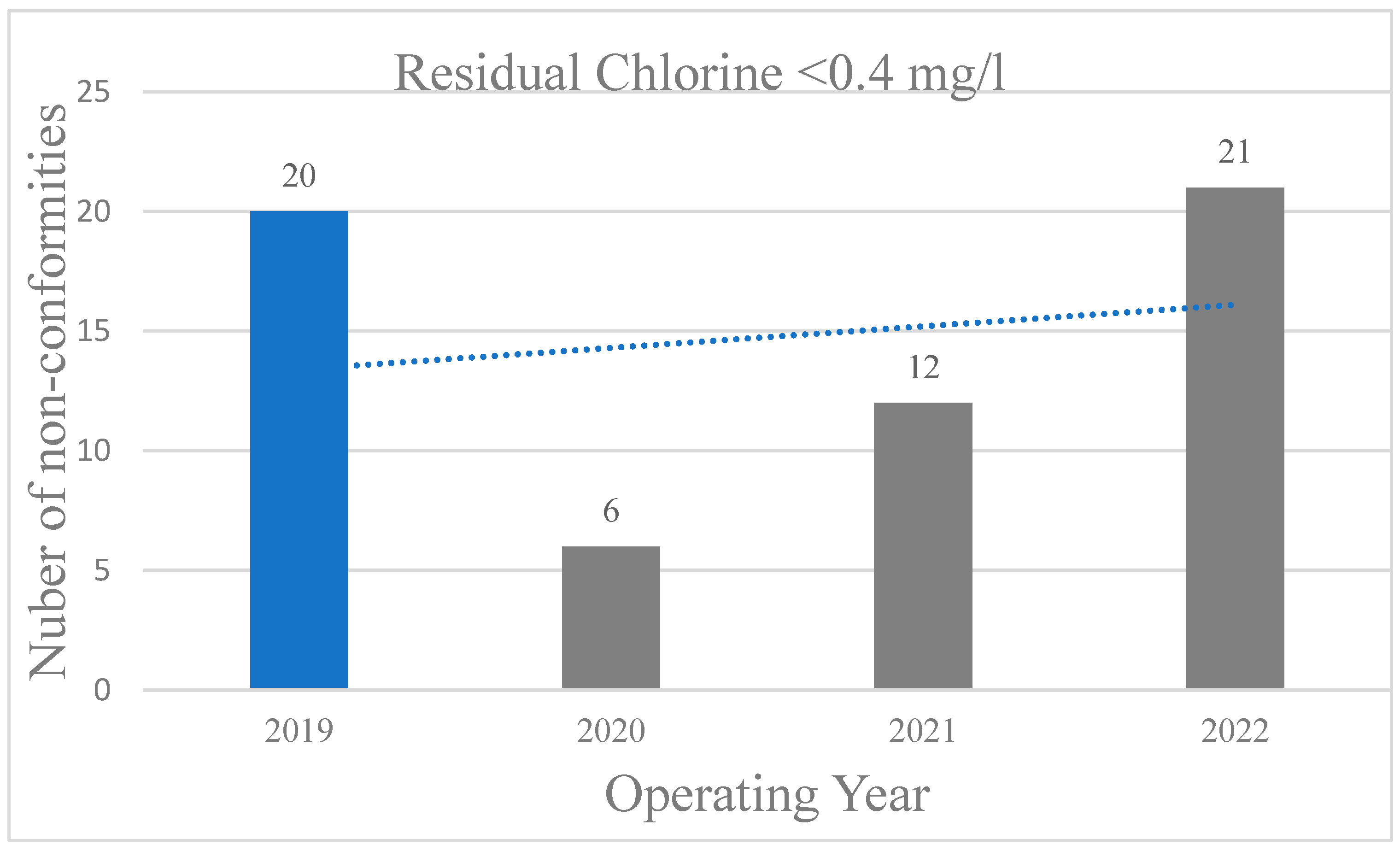

First, the non-conformities of residual chlorine levels less than 0.4 mg/L for the mentioned years are presented (

Figure 1). It is reported a vast reduction of 67% and 58% in non-conformities in 2020 and 2021 respectively, that is attributed to the elevated precautionary measures to combat COVID-19. In our previous study, we have showed an analogous reduction of non-conformities at 79% between 2019 and 2020 [

17]. On the other hand, the increase in non-conformities in 2022 suggests the inability of operators to manage and retain strict protocols over time, which led to restoring chlorine levels to previous statuses. Concerning chlorine as a disinfectant in swimming pool water, a study by Mellou et al. (5) utilized a questionnaire to assess adherence to more strict health protocols in hotel swimming pools during the COVID-19 pandemic. The study found again that 70% of facilities met the regulatory standard for free chlorine in pool water (1-3 mg/l).

In 2019, despite the legislative requirement for residual chlorine being 0.4 to 0.7 mg/L, many hotels applied 0.4 to 3 mg/L, which were global guidelines. In this study, for non-compliances below 1, 2 and 3 mg/l, a similar behavior is observed for all years during the COVID-19 period (

Table 1). As the amount of residual chlorine increased from 1, 2 to 3 mg/l, the non-compliances also increased from 17,57%, 53.38% to 74.32% for 2020, from 16.9%, 47.89% to 69.95% for 2021 and from 19,35%, 44.52% to 70.32% for 2022 respectively. This is attributed to the fact that strict chlorination at 1-3 mg/l are costly and non-viable for the operators even though a high compliance is reported by them in the study of Mellou et al. (5).

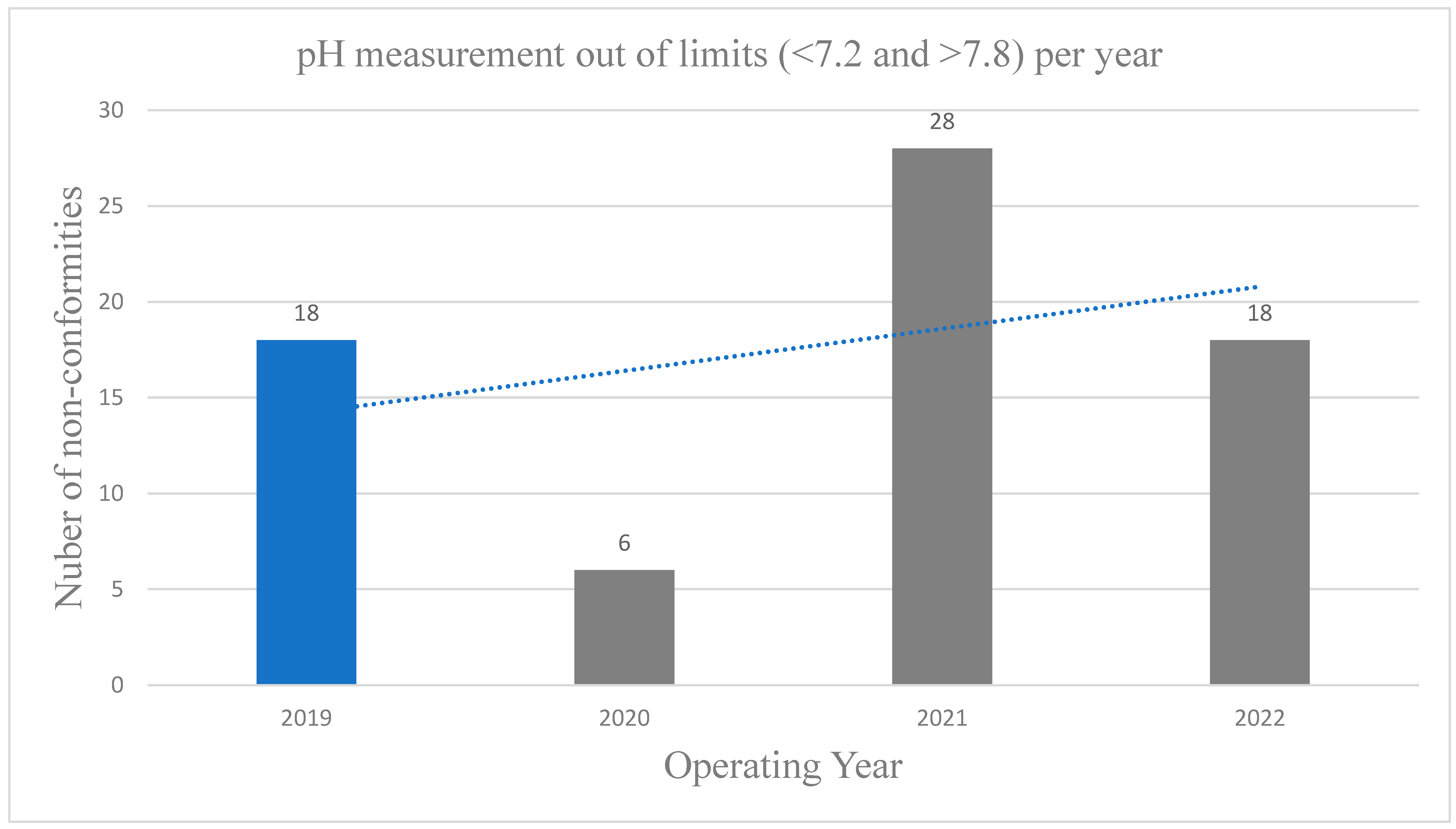

Next, the pH values must be sustained between 7.2 and 7.8 for chlorine disinfectants (16). Global public health organizations indicate that a pH value level below 7.2 may lead to ocular discomfort due to increased chloramine production, rapid depletion of chlorine, erosion of exposed cement, and metal corrosion. A pH value greater than 7.6 may diminish the efficacy of chlorine disinfection, elevate chlorine demand, cause ocular irritation, lead to skin desiccation, result in murky water, and promote scale accumulation (35). The research conducted by Masoud et al. (24) found that most swimming pools failed to adhere to the established pH value requirement. In the present study, the comparison of the pH values during Covid-19 and pro-Covid-19 revealed a 69% reduction in non-conformities in the year 2020 with the strictest protocols. Even though, 2021 and 2022 were expected to be years with similar levels of reduction in non-conformities, a negligible reduction of 1% for 2021 and 3% for 2022 was observed (

Figure 2). This suggests a relaxation of the preventative measures which resulted also in pH values out of the acceptable limits.

Similarly, according to national legislation it is imperative that the water temperature must remain below 25 °C. Maintaining the appropriate water temperature in a swimming pool is crucial for optimizing performance, comfort, and safety of swimmers [

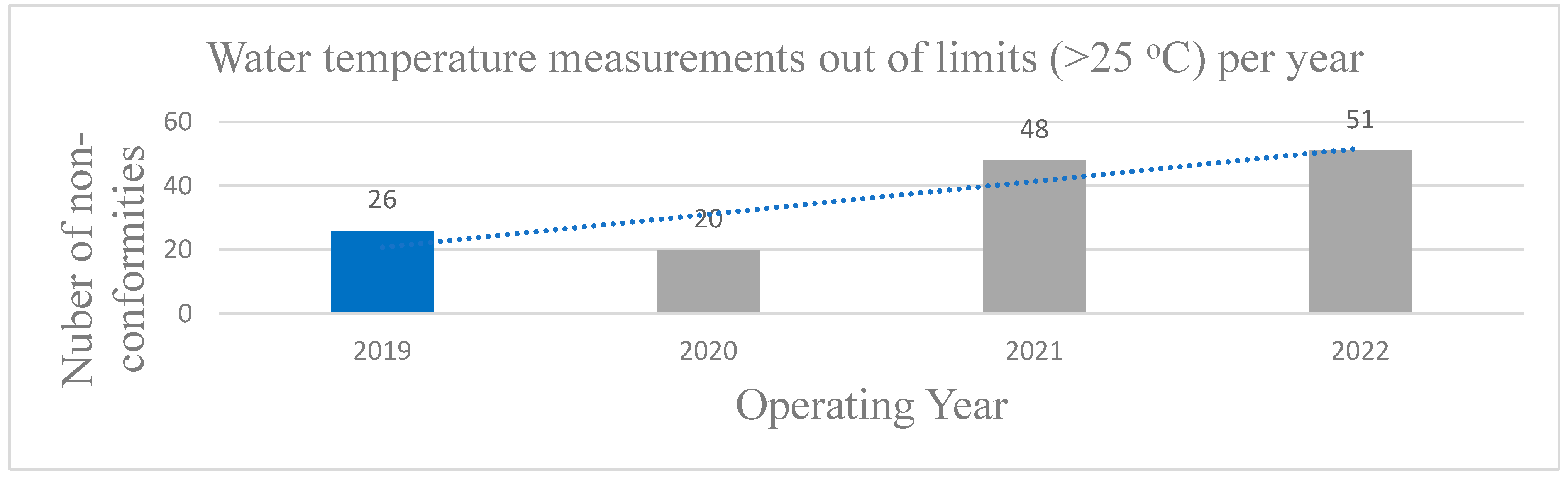

18]. Nonetheless, in a Mediterranean country as Greece with elevated temperatures in summer touristic season, this limit regulation poses a problem since, the majority of swimming pools are outdoor and exposed to sunlight and thus hot temperatures. The latter also affects the quantity of free chlorine deactivating the disinfection process. Herein, a vast issue is observed for the samples measured during COVID-19 since the number of non-conformities of the water temperature values are increased from 2020 to 2022 (

Figure 3) up to two times (from 26 in 2019 to 51 in 2022), which is related to the relaxation of the strict protocols, during time, leading to a total degradation of the operating rules and non-regulation of the basic physicochemical parameters.

Overall, the evaluation of the physicochemical parameters measured for the years 2019 to 2022 shows that tourist operators followed the guidelines and strict protocols primarily during the first year of the pandemic, which led to very characteristic compliance for 2020 across all parameters. However, after two years and the implementation of strict measures, the operators were excluded from this management, reaching a point of complete non-compliance and disregard for operational rules that could create public health problems. Next, we will see how non-compliance with simple rules of chlorination, pH adjustment, and temperature affects the development of harmful microorganisms for public health.

The Microbiological quality of swimming pools is crucial for preventing waterborne diseases and ensuring swimmer safety. Various studies highlight the importance of monitoring microbial contaminants, including fecal coliforms, staphylococci,

Legionella pneumophila and

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which can indicate health risks associated with swimming activities [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. While the focus on microbial quality is vital, it is also important to consider the potential for over-regulation, which may lead to unnecessary closures of facilities, impacting public health and recreation. Balancing safety with accessibility remains a challenge in pool management.

The microbiological hygiene of swimming pools was even more important during the pandemic, and achieving it was more difficult due to the technical problems caused by the country's long period of lockdown. The long-term closure or underperformance of the pools led to water stagnation and inadequate chlorination disinfection.

In this study, the existence of microbiological parameters in 708 water samples, namely

E. coli and

P. aeruginosa, total coliforms and total microbial flora was observed (

Table 2). A comparison of the compliance to the legislation measures between 2019 and 2020-2022 years of COVID-19 pandemic was made. Seemingly, a compliance to

E. coli, total coliforms and total microbial flora microbiological parameters is observed during the years which is attributed to the strict protocols, high chlorination of water, increased water circularity and finally, lower capacity of swimmers per m

2. This comes in agreement with our previous study, in which the comparison of 2019 and 2020 showed significant reduction in these parameters[

17]. Overall, despite the relaxed measures and irregularities from the operators on keeping the physicochemical standards within limits during pandemic,

E. coli, total coliforms and total microbial flora remained under acceptable limits. This is attributed to also to the high sensitivity of the pathogens to chlorine disinfection.

On the contrary, in 2021 there was a reduction in the growth of P. aeruginosa, nonetheless, in the years, 2020 and 2022 the growth is increased to higher values compared to 2019. This indicates that the regulation of P. aeruginosa, is more challenging than other microbiological parameters, which validates the assertions and directives of international public health agencies and the scientific community.

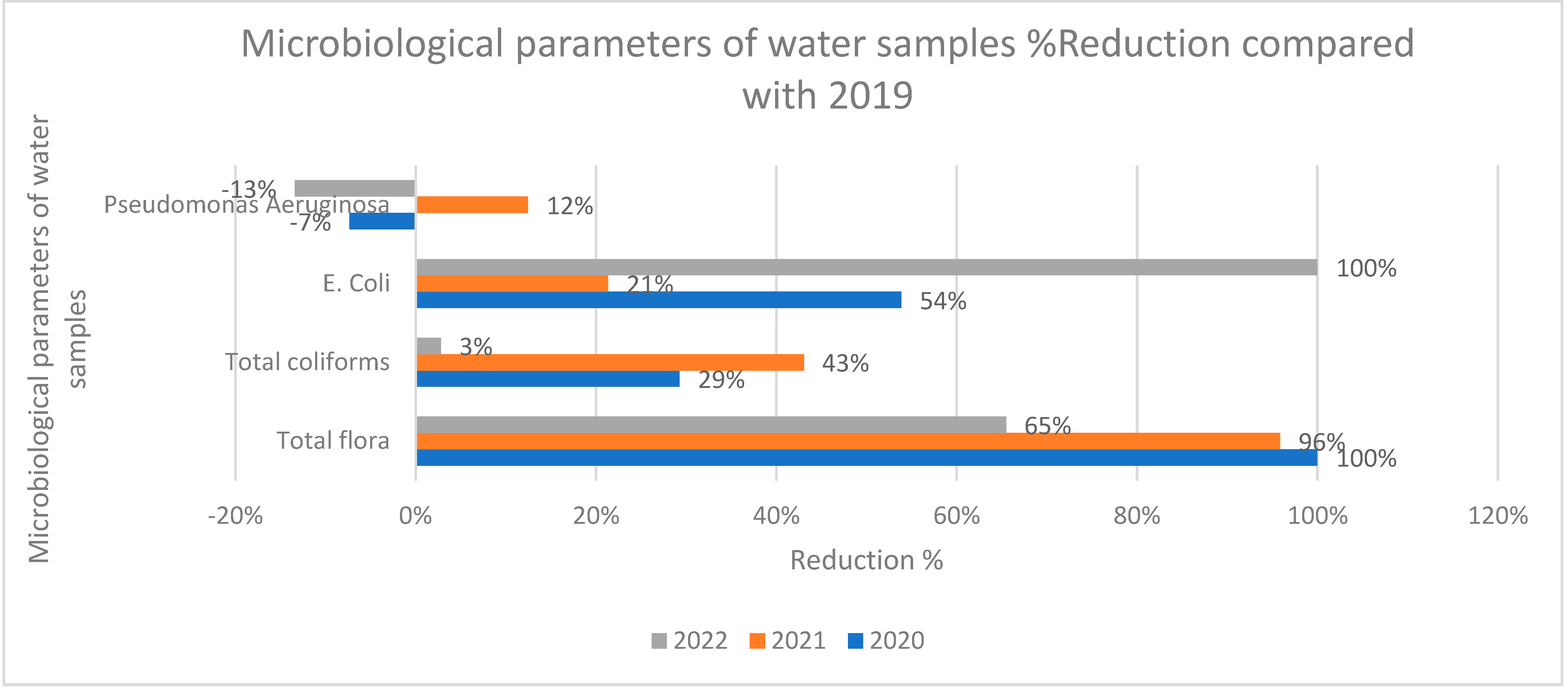

The reduction of non-conformities of microbiological parameters for the pandemic years of 2020-2022 compared to 2019 are presented in

Figure 4. For the total flora, the reduction of non-compliances for the years 2020 and 2021 are significantly higher than 2022 which comes in agreement with the discussion for the irregularities in parameters and incompliance of operators with protocols through that year. In accordance, the evaluation of the reduction of non-conformities in total coliforms showed a medium reduction through 2020 and 2021 and a negligible reduction in 2022. In contrast with this trend, E coli conformities were high in 2020 and 2021 and even higher in 2022 showing a higher reduction in 2022. It has been shown that E. coli is a highly sensitive parameter in disinfection procedures and thus similar studies suggest the usage of other indicators such as free chlorine, pH and total coliforms for the determination of hygiene recreational water [

24]. Finally, the current investigation identified abnormal prevalence rates of the pathogenic bacterium

P. aeruginosa in the reference years 2020, 2021 and 2022, in accordance to other studies (17,32,33). P. aeruginosa is found in aquatic environments and exhibits resistance to chemical disinfectants, including chlorine. P. aeruginosa induces several disorders, including bursitis, otitis externa, keratitis, urinary tract infections, and gastrointestinal infections via exposure to the skin, ears, eyes, urinary system, lungs, and intestines. Seventy-nine percent of ear infections in swimmers are ascribed to P. aeruginosa, with symptoms including ear pain and hearing loss (32,33). A assessment of water-borne infections in the USA from 1999 to 2008 indicated that P. aeruginosa was the second most prevalent water-borne pathogen, following Cryptosporidium.

Next, the statistical analysis on the entity of samples for all operating years showed that an odds ratio for increased temperatures of water inside the pool was correlated with the presence of

P. Aeruginosa. Similarly, the relative risk of the presence of the

P. aeruginosa, Total microbial flora and coliform bacteria and

E. Coli, related to low chlorination of <0.4 mg/L was greater than 1. The P-values were statistically significant in most of parameters (

Table 3).

Finally, the Linear Regression analysis showed a positive association with unacceptable occurrence of

P. aeruginosa in water samples (

Table 4).

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, the enhanced safety protocols implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic led to higher compliance with national and international regulations, increased vigilance, self-discipline, and motivation among swimming pool managers and operators, as well as more systematic inspections and sampling by authorized public health authorities, thereby contributing to safer pool operations. This study showed that the application of the strict sanitary protocols, showed a tendency to improve the microbiological parameters as well as the physicochemical properties of the water in the pools studied. More specifically, compliance to the national legislation limits was higher in the first year of application of the strict protocols, while in the following two years it decreased, and for some parameters, the excesses were higher than the reference year 2019 (before the COVID-19 pandemic) saving resources (financial, personnel) and fatigue from strict protocols.

In Greece, the modernization of swimming pool operational regulations, encompassing risk analysis and the incorporation of legislative mandates for limit compliance and other essential microbiological indicators, such as P. aeruginosa, Cryptosporidium, and the use of Staphylococcus aureus as an additional indicator when applicable, is critically important. Furthermore, based on international standards, it is necessary to amend the allowable pH range under the existing Greek legislation from 7.2-8.2 to 7.2-7.8 to enhance disinfection efficacy and mitigate the adverse effects of chlorination.

In order to prevent both microbiological and chemical risks, it is necessary to maintain a balance. According to the WHO guidelines, since 2004, it is advocated to create and execute "water safety plans" for recreational waters in hotel facilities similarly to water for human consumption. This preventative measure would substantially enhance the rapid and effective management of developing public health concerns and issues related to recreational waters (e.g., Legionella spp., P. aeruginosa, Cryptosporidium, Staphylococcus aureus, and other infections). More rigorous safety standards for swimming pool environments in hotels, more attentiveness and incentive of pool operators through training, and more systematic inspections by authorities may result in improved public health practices, fewer fines, lower cost for corrective actions, and fewer customer indemnities in these settings.