2. Materials and Methods

As mentioned in the introduction, we are concerned with two types of entropy,

Sconfig related to network configuration and

Stherm, related to energy conversion.

Stherm is computed as described above in terms of voltage, current and temperature.

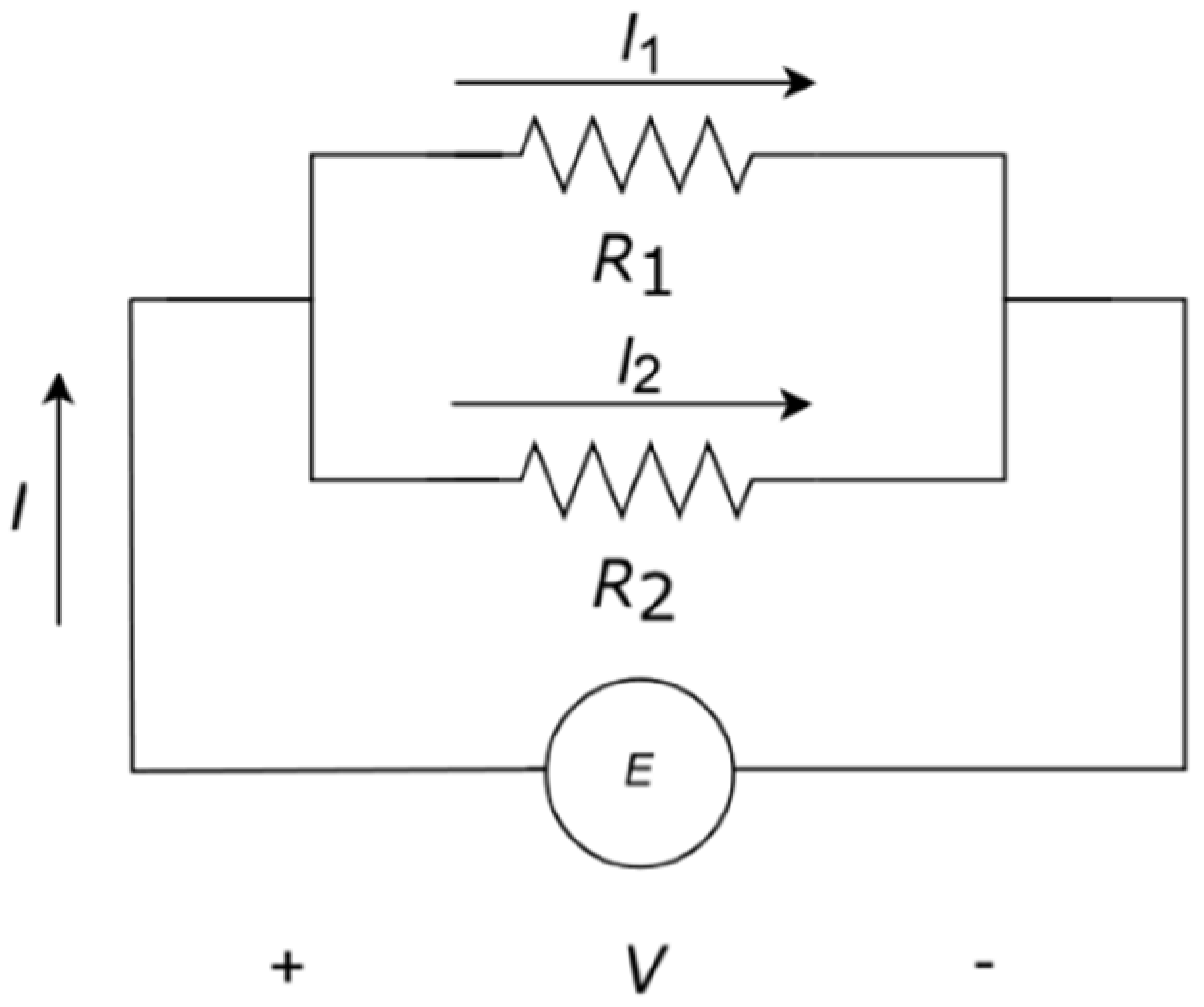

Sconfig is calculated in terms of the probability of network configurations. We describe the analysis of the entropy calculation for two resistors in parallel, in the configuration shown in

Figure 1. Applying Kirchhoff laws, we can write the relationship between currents and voltages in terms of a network matrix.

The probabilistic interpretation of this expression in terms of conductances can be found in [

8], but for our purposes in relating it to thermal entropy we retain the resistive form. We aim to calculate the entropy of this matrix. As the matrix is diagonal, we can use the Shannon entropy using the expression:

This equation thus provides information about the configuration or complexity of the system, which in this case has two degrees of freedom. Landauer proposed this approach, but he did not develop it [

38]. In this expression,

p(

x) represents the probability of current flowing through one resistor. Considering the two resistors together, and assuming a constant temperature

T, the result is:

It can be seen that the probability of current flowing through one resistor or the other is simply given by the current divider solution given in (10). This gives us the configurational entropy of a circuit.

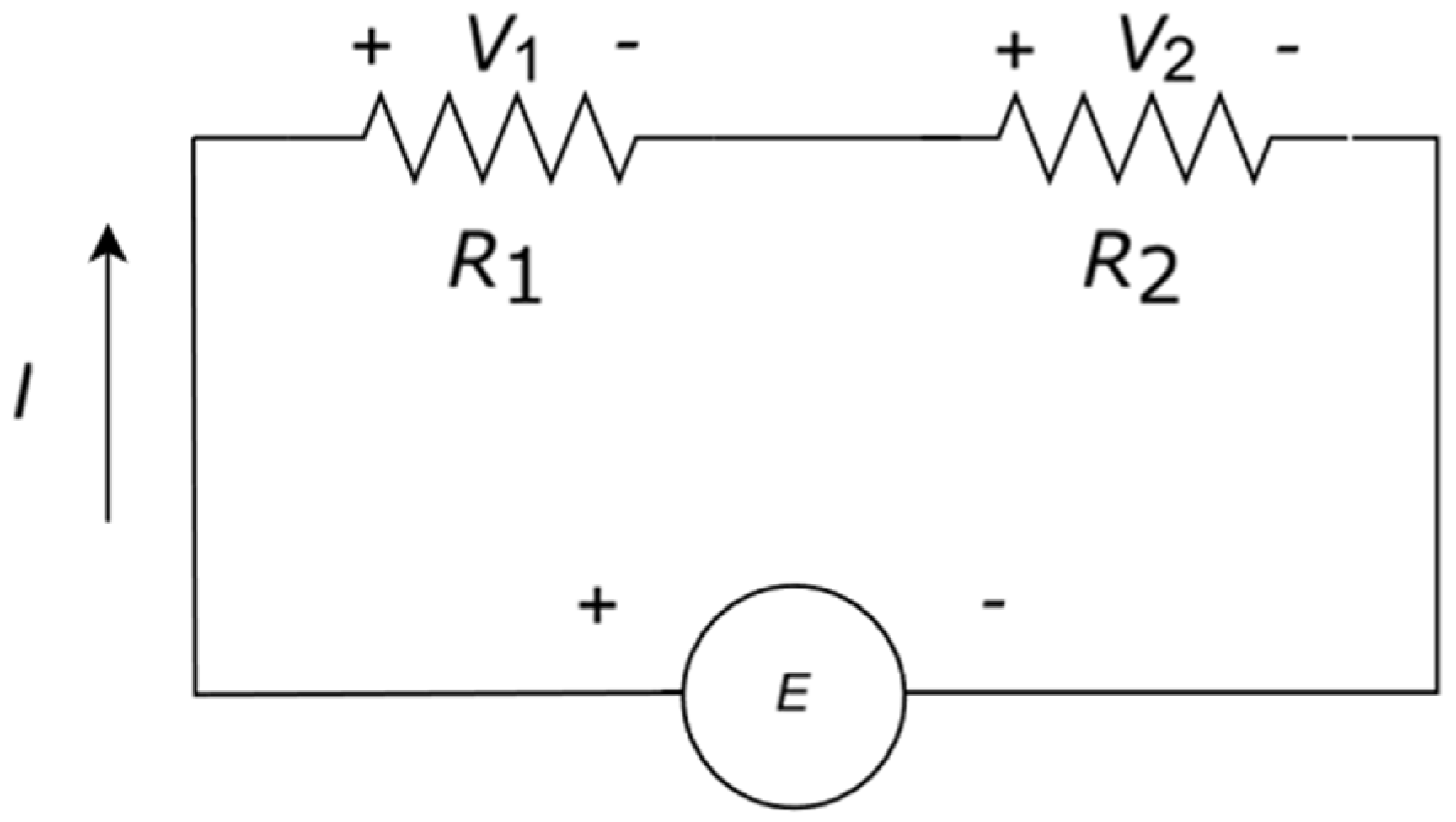

Another resistor configuration is two resistors in series (See

Figure 2). In this case, the circuit considered is a voltage divider instead of a current divider, defined by:

We want to determine

Sconfig using the same procedure that as for parallel resistors. The matrix is again diagonal:

In this particular case,

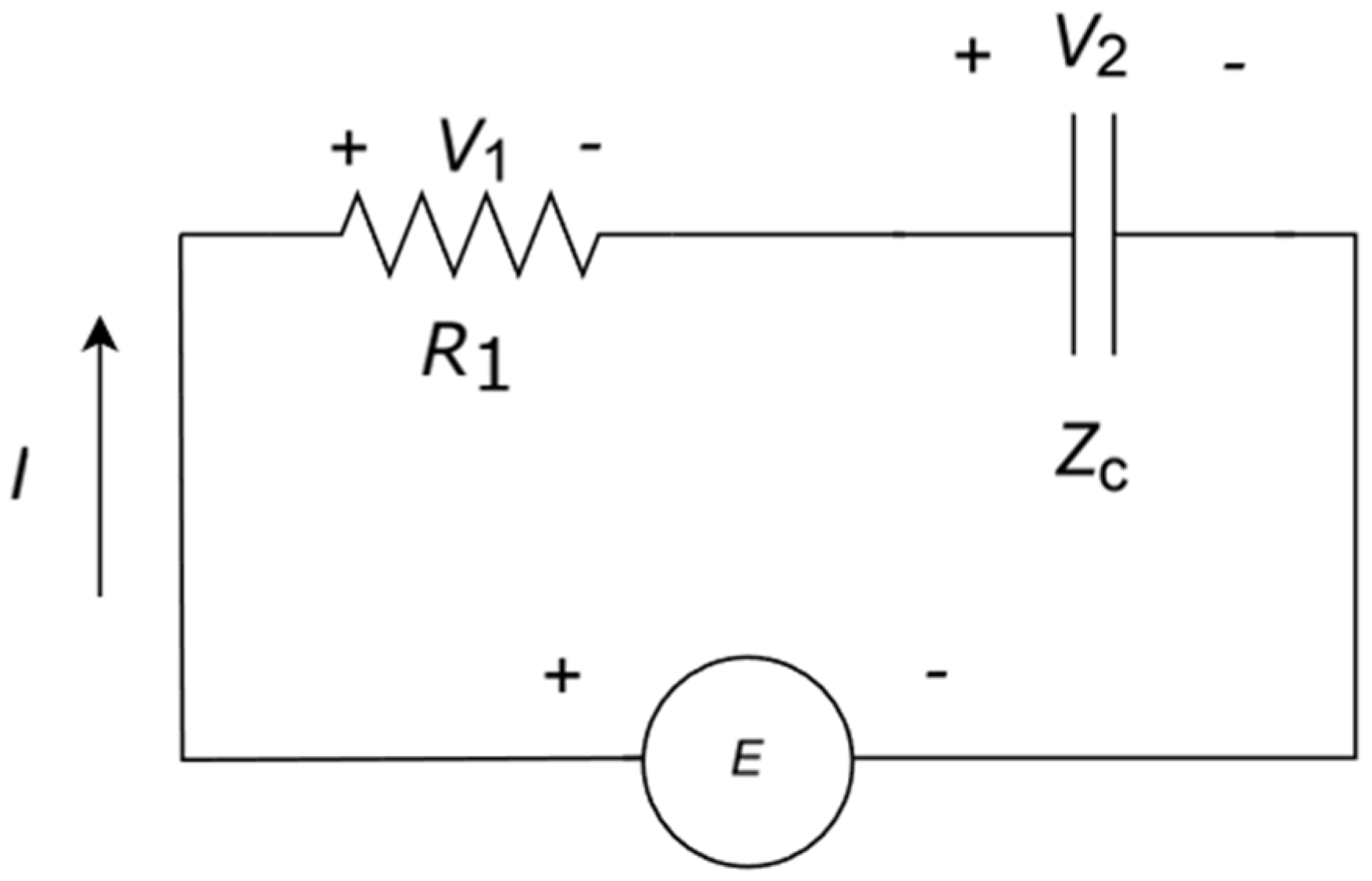

Sconfig is the same for both parallel and series resistors. We extend this analysis to

R-C networks, which are less common. Following our considerations on

Sconfig, we notice that this circuit (

Figure 3) has only one degree of freedom in the DC analysis and the entropy is zero.

If

E is time-dependent, e.g., a sinusoidal source in steady state, then the capacitor impedance is frequency-dependent

, which introduces a new degree of freedom. Accordingly, we can write

Sconfig as

where ln (

r e

iθ) = ln

r + i

θ is the principal value of the logarithm. The use of complex Shannon entropy has already been studied [

39,

40].

To obtain Stherm for these circuits, we follow the description of the state of the art described in (12). For capacitive networks, Stherm can be evaluated either in the time domain or in the frequency domain, taking advantage of the invariance of energy and entropy under time transformations. For simplicity, we consider a single sinusoidal excitation signal characterised by its root mean square voltage (Vrms).

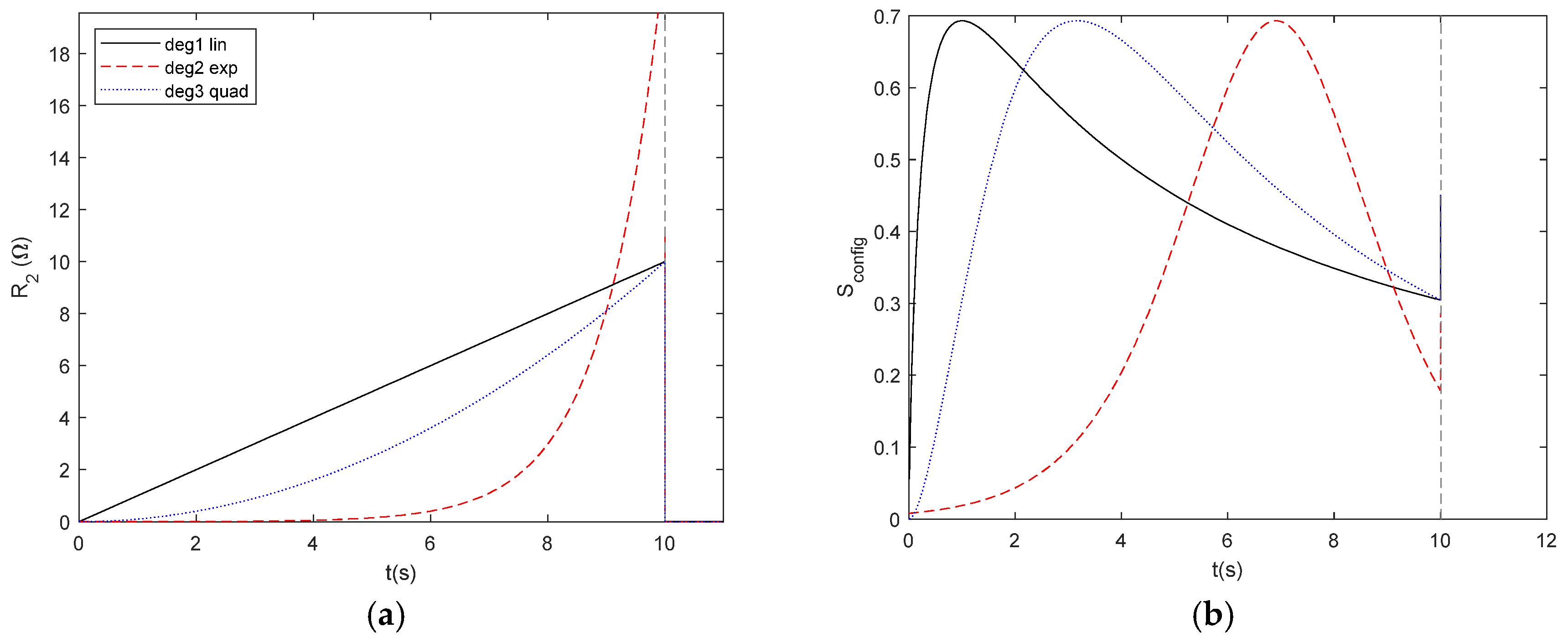

For completeness, we also investigate the time dependence in systems undergoing degradation. In this case, we consider

Sconfig as a function of time, and

Sthermal obtained from the time integration of the power. We consider three different types of degradation, described by a linear function,

a quadratic function

and an exponential function

which are commonly used in fatigue and breakdown studies. Each function describes material fatigue as an increase in

Sconfig. In addition, we also introduce an entropy threshold with a Heaviside function, which describes structure breakdown, in case that it is reached. The multiplying constants in

R2deg2 and

R2deg3 are chosen to keep the degradation in the same range for

t = 10 s. We substitute

R2 for

R2deg in entropy calculations.

4. Discussion

So far, we have obtained valuable results that are worth discussing: the entropies relation, the effect on constructal law and the theorem of maximum power transfer, and the effect of time on entropy in R-C circuits and degradation.

We can begin with entropy itself. It is found in literature a discussion between Claude Shannon and John Von Neumann about entropy. C. Shannon said “My greatest concern was what to call it. I thought of calling it ‘information,’ but the word was overly used, so I decided to call it ‘uncertainty.’ When I discussed it with John von Neumann, he had a better idea. Von Neumann told me, ‘You should call it entropy, for two reasons. In the first place your uncertainty function has been used in statistical mechanics under that name, so it already has a name. In the second place, and more important, no one really knows what entropy really is, so in a debate you will always have the advantage.

”. Whether the story is true or not, it is certain that the concept of entropy still generates some debates on its interpretation and, as a physical magnitude and a mathematical property, it is worth devoting more research effort to it.

We use the quote to point out that they were probably both right. Entropy is a mathematical property that can be applied in different disciplines, but it has a different physical meaning in each problem. As mentioned above, Jaynes prevents us from confusing information entropy and thermodynamic entropy unless we are dealing with thermodynamic problems. So what we have tried to investigate in this paper is not whether they are the same thing, but how they are related, as there are two types of entropies describing different characteristics of the system: this is the purpose of relating Sconfig to Stherm. Stherm is clearly related to energy conversion, i.e., when the energy enters the circuit it is converted into heat. Sconfig is related to network structure, and is either decided by us, i.e., we decide whether to design a series or parallel circuit, or it evolve naturally over time due to degradation induced by energy dissipation. It is important to note that if the relationship R2/R1 ratio changes due to energy dissipation, we have a causal relationship between Sconfig and Stherm. Conversely, if we change the ratio arbitrarily or manually, there is a correlation, but not a causal relationship between Sconfig and Stherm. The same happens with temperature, and here we find the origin of the problem inferred from (14). We found that the change in entropy of the resistor (system) was not previously considered when its temperature changed. Taking this into account, the relationship Sconfig – Stherm helps to clarify the understanding that we can consider the entropy as a function of state of Sconfig and Stherm for the network system, but we also need to consider the entropy change in the universe to introduce the change in the network.

In order to investigate both entropies, as to our knowledge, entropies of a system are not usually correlated in complex systems, we investigate how energy is transformed in a linear system as a function of the network configuration. On the one hand,

Sconfig was derived from a probability of the electrical circuit, and on the other hand,

Stherm is inferred from thermodynamic relations. Understanding entropy derived from a probability allows us to deal with causal and not-causal systems. Obviously,

Stherm is causal because it is governed by the laws of thermodynamics. But

Sconfig is not causal, the network change is decided by the design of the electric circuit. In probability, if the system is not causal, the probability spaces are likely to be independent in many cases, and thus, the probabilities can be computed as independent. In our opinion, this approach allows an interdisciplinary approach to complex problems, as it allows to deal with different properties of the system to be treated with the same magnitude. For instance, the studied

Sconfig and

Sthermal are independent as long as

Sconfig is not modified by the same energy. This explanation is consistent with the constructal law, as we proposed in the results section, which states that “for a finite size flow to persist in time (to survive) it must evolve in such a way that it provides easier and easier access to the currents that flow through it” [

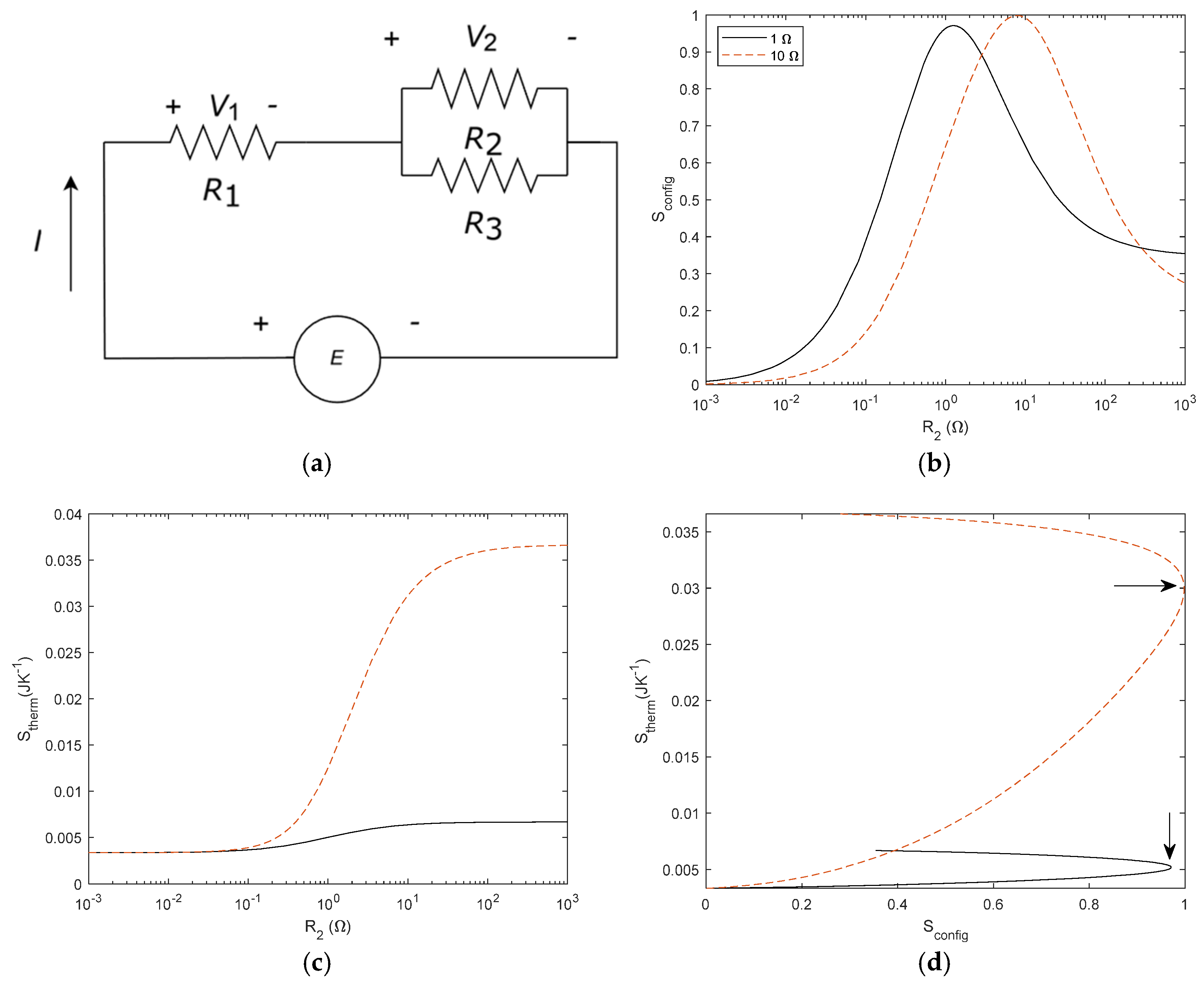

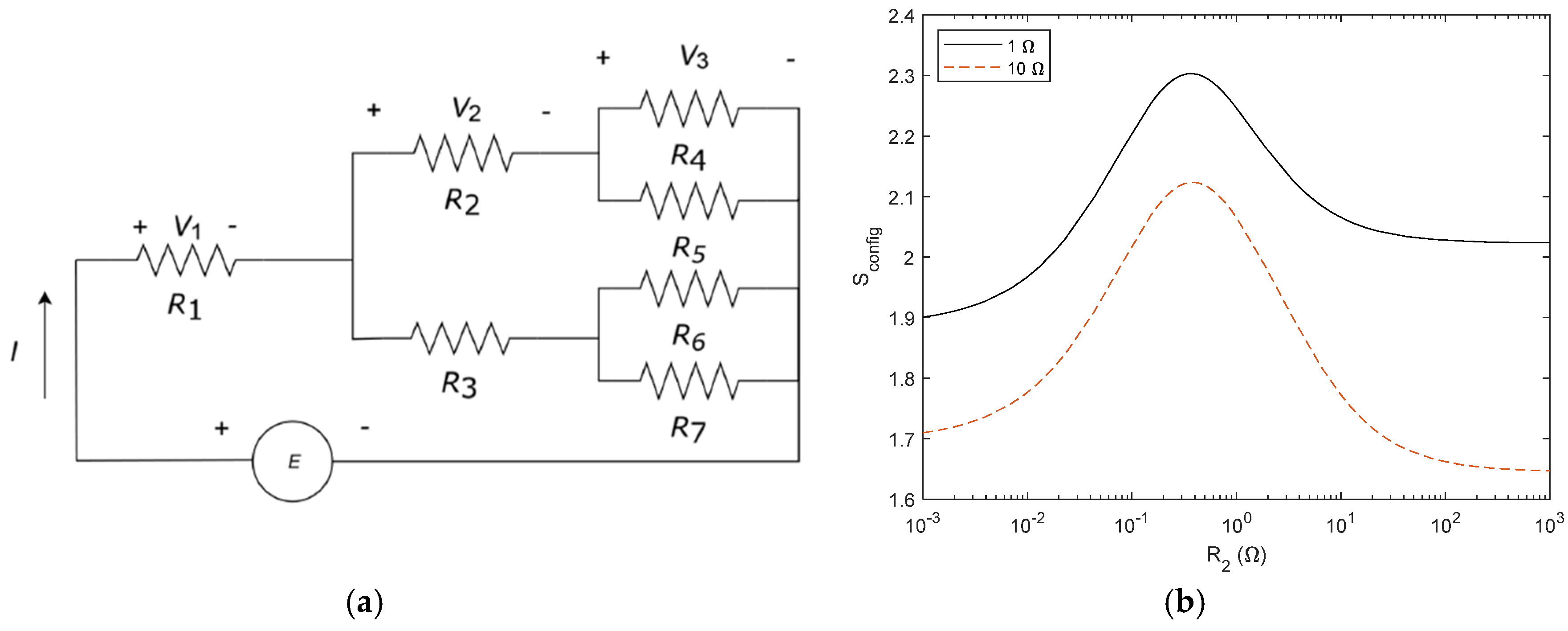

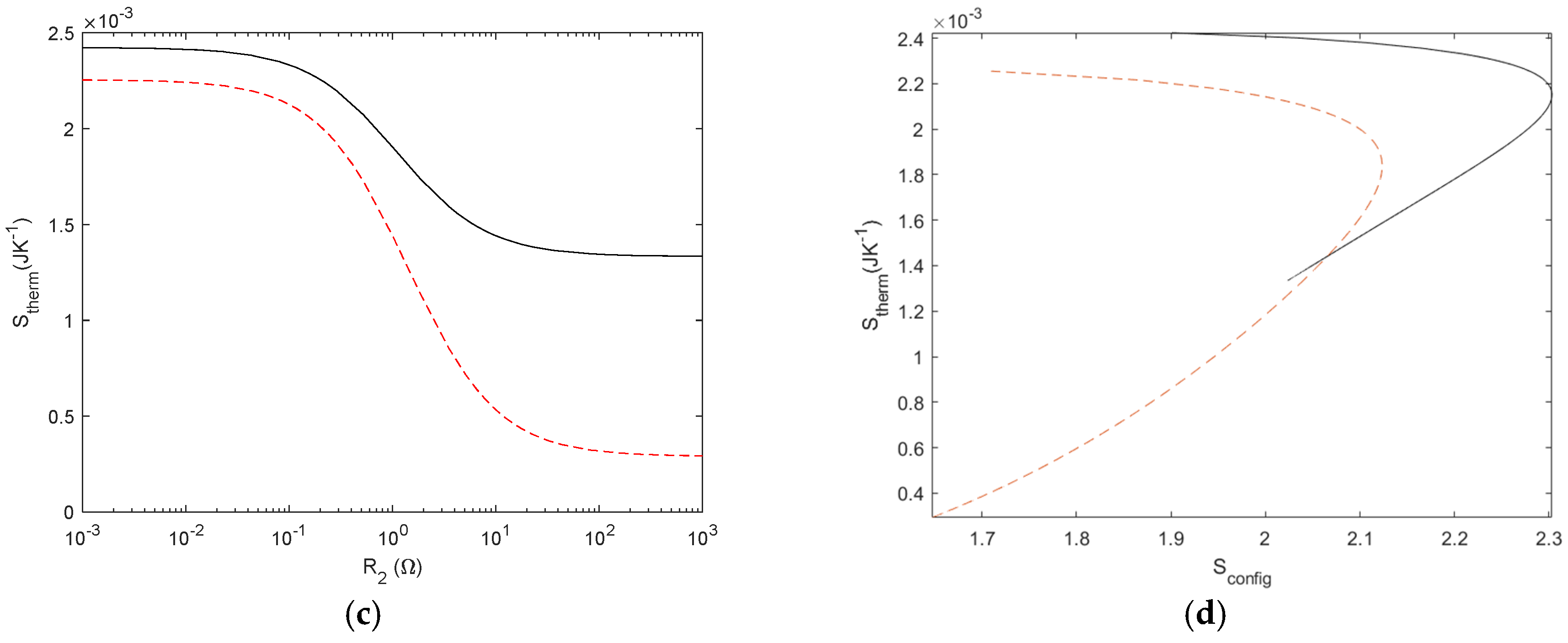

23] and to our knowledge, it has not been illustrated using this approach, which can help to clarify its understanding. For a better understanding of it, we considered the typical examples of this law, such as tree-shaped structures, that can be found either in rivers or blood capillaries. To gain a deeper insight into this result, we obtained the entropies correlation for a tree-shaped structures with three and seven elements (See

Figure

12 for three elements and in

Figure 13 for seven elements). In these networks, the symmetry of the resistor configuration is broken and thus,

Sconfig (

R2/

R1) is not symmetric anymore. It is important to note that the maximum of

Sconfig corresponds to an extreme of the

Stherm. As indicated by Bejan, the design of the structure organizes to fit the flows. From our results, and in other words, the organisation obeys a causal relationship between the energy involved in the process and the final network structure. From Bejan’s definition, we had understood that design configured the energy

Sconfig –

Stherm but it seems to be more convenient to plot

Stherm –

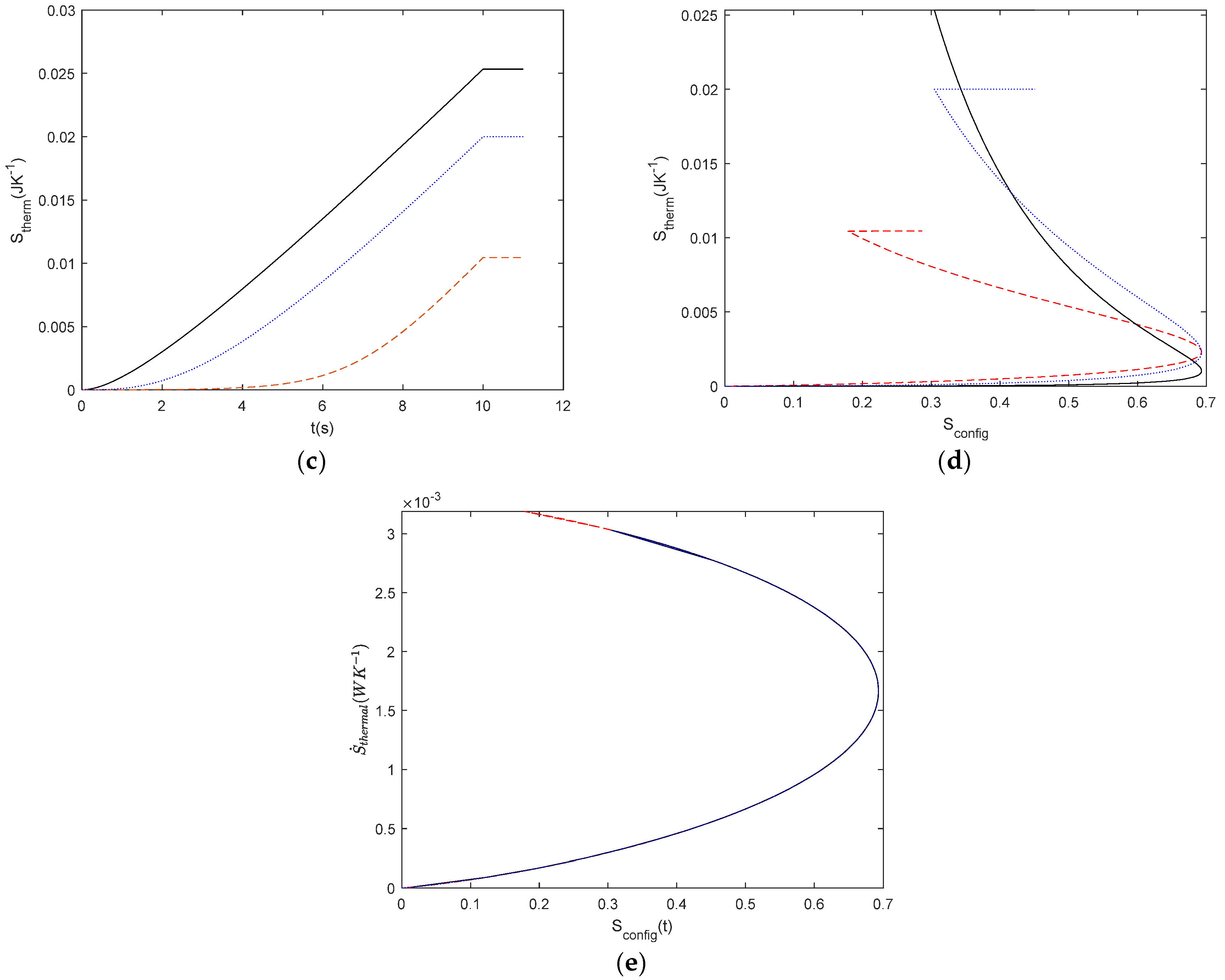

Sconfig. For instance, replotting

Figure 18 (d) with the axis exchanged, it is easy to write a function

Sconfig =

f(

Stherm) as illustrated in

Figure 19 so that constructal law satisfies the condition

And the correlation between both entropies leads to a maximum in which the constructal law is satisfied. This approach therefore opens up the possibility of exploring a law for the dual (gradients), which has not been considered before, since gradients behave similarly to flows and also of exploring causal and non-causal interdisciplinary problems.

Continuing with the constructal law applied to resistors, we can also interpret that (17) depends on the geometry if we consider that the resistance is given by R=ρ l/A, where ρ is the resistivity, l is the length and A is the area of the resistor. This agrees with the relationship between geometry design and energy dissipation given in the law.

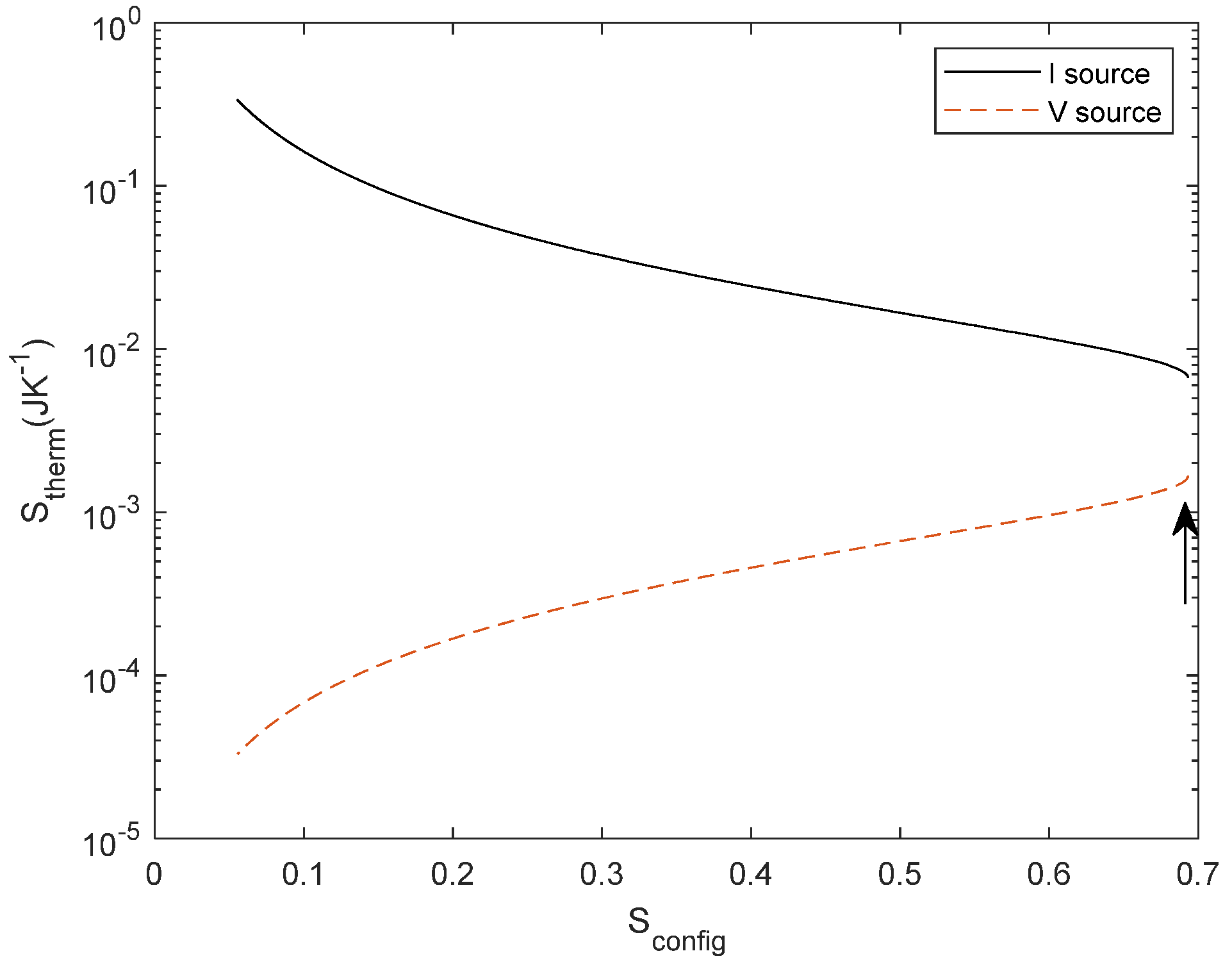

Another interesting result concerns the theorem of maximum power transfer. This theorem is traditionally derived from a minimisation process of the energy transferred. In

Figure 10, we found that the minimum point corresponds to the theorem. It is not surprising that this theorem depends simultaneously on the network and thermal entropies, since its classical derivation minimises the power for the network. However, using our approach

Sconfig =

f(

Stherm), we can have a better understanding of the power transfer not only at the extremal point but also as a function of the network configuration, allowing further predictions of circuit performance.

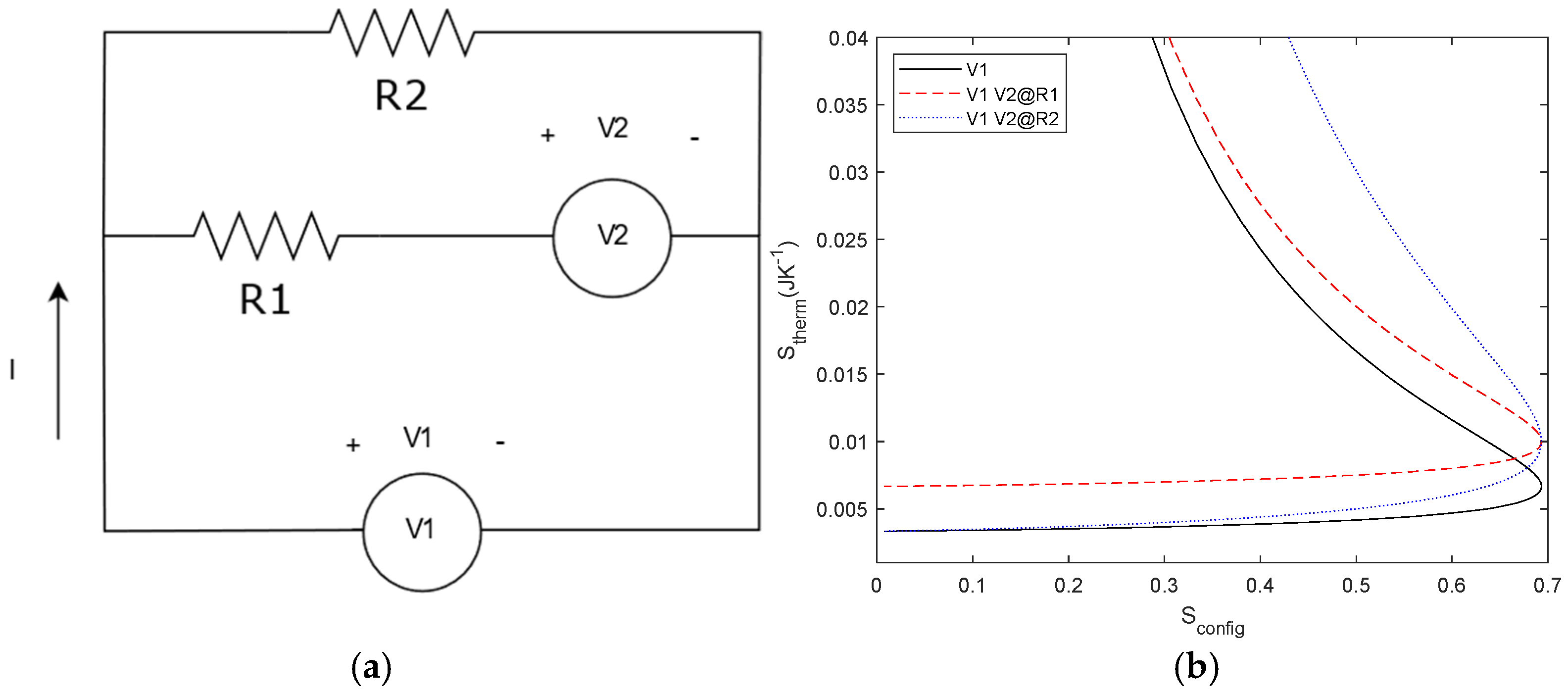

Regarding the increase in complexity with more resistors or power sources, we can point out that changing the power sources affects the energy conversion but not the network configuration, and thus, while Stherm changes, Sconfig remains the same. On the contrary, increasing the number of resistors in the network introduces an entropy term for each resistor, thus changing Scon This is an interesting issue that we can discuss using the 3-resistors circuit illustrated in

Figure 12a. From an electrical point of view, we can connect the resistors in parallel and in series to find the equivalent resistor. The dissipated power will be the same for R1, R2 and R3, R1+R2//R3 or Req = (R1+R2//R3) where // means connected in parallel. However, the entropies associated with each case, assuming all resistors with R = 1 Ω, are 0.9634, 0.6365 and 0 respectively. Obviously, the entropy decreases as the circuit simplifies.

Time-dependent results are also interesting. On the one hand the degradation studies and on the other hand, the complex entropy in

R-C systems. Degradation is a causal constraint of network modification due to energy dissipation, which can be described by

Sthermal. We proposed three arbitrary time-dependent curves. We previously investigated the physical degradation of resistors [

32] and capacitors [

33], having established the interest of

. In this contribution, we have confirmed the interest not only of this entropy but also of

Sconfig, which had already been pointed out in [

32] as a possible explanation of the fatigue and breakdown of the resistor. An interesting result, which could be worthy of further research, is that the relationship between

Sconfig and

is invariant to the degradation mechanism, as long as they are the only entropies involved in the process. However,

Sconfig and

Sthermal are dependent on the degradation mechanism. Both results can be useful for degradation characterisation, in order to complement the approaches given in [

32,

37].

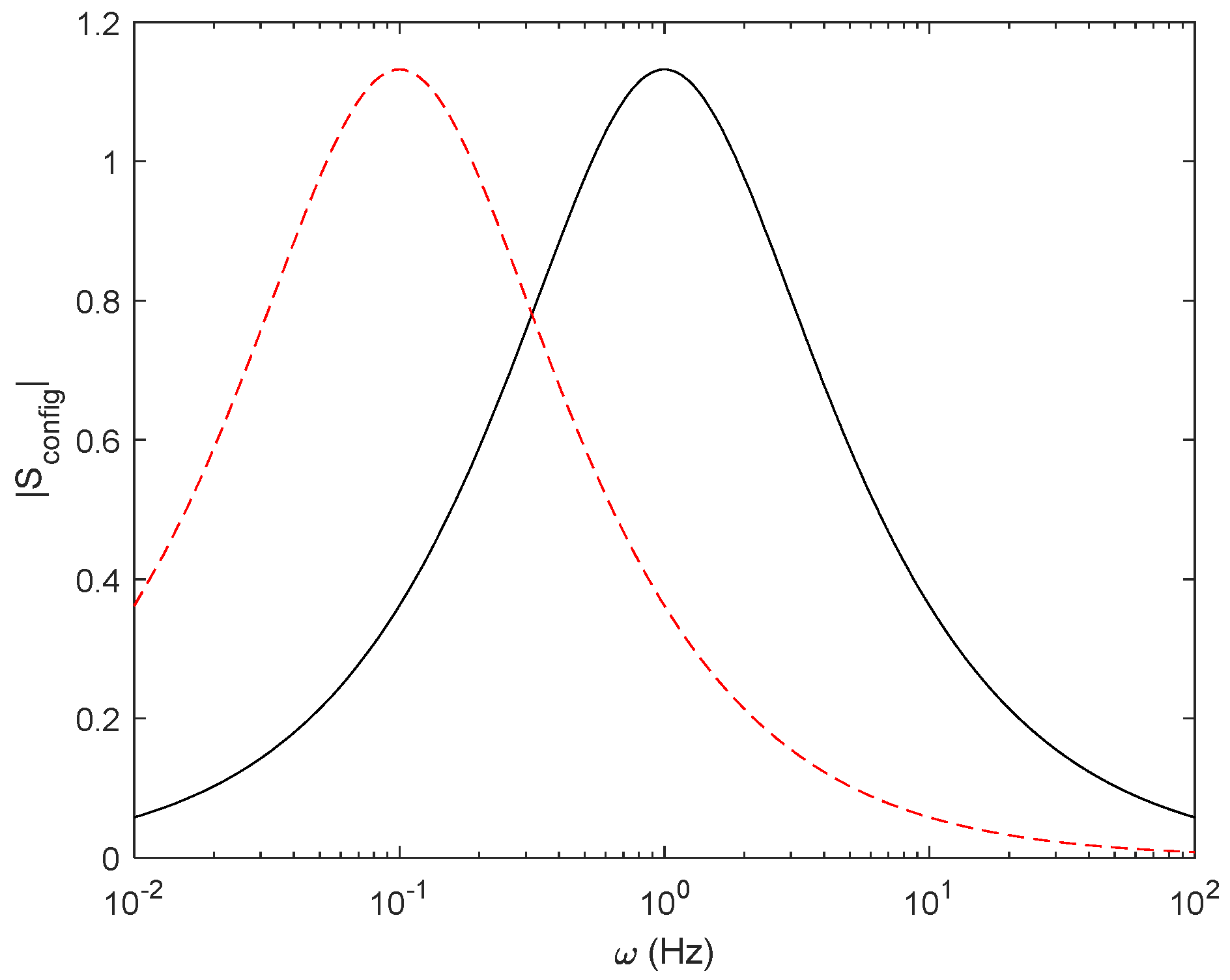

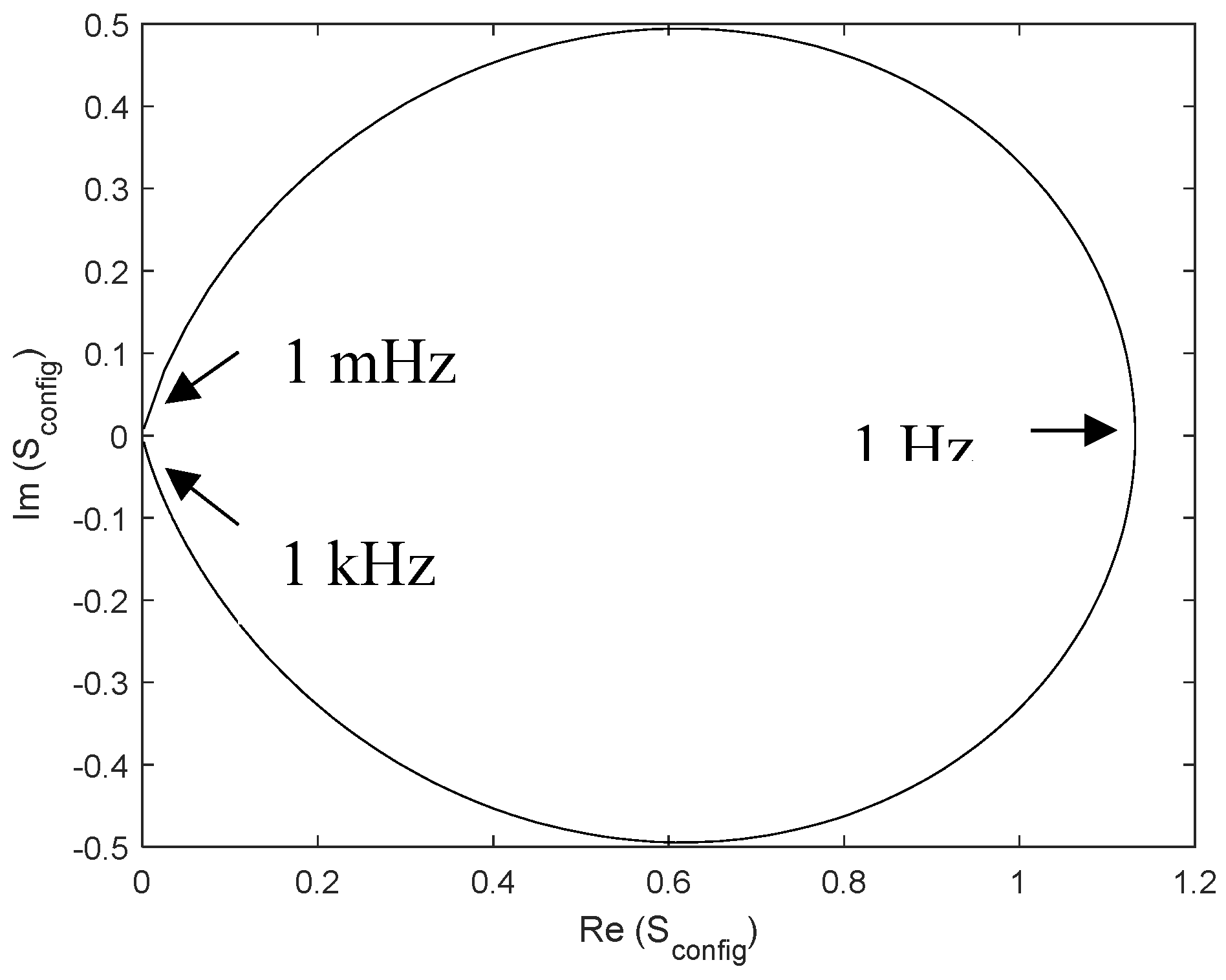

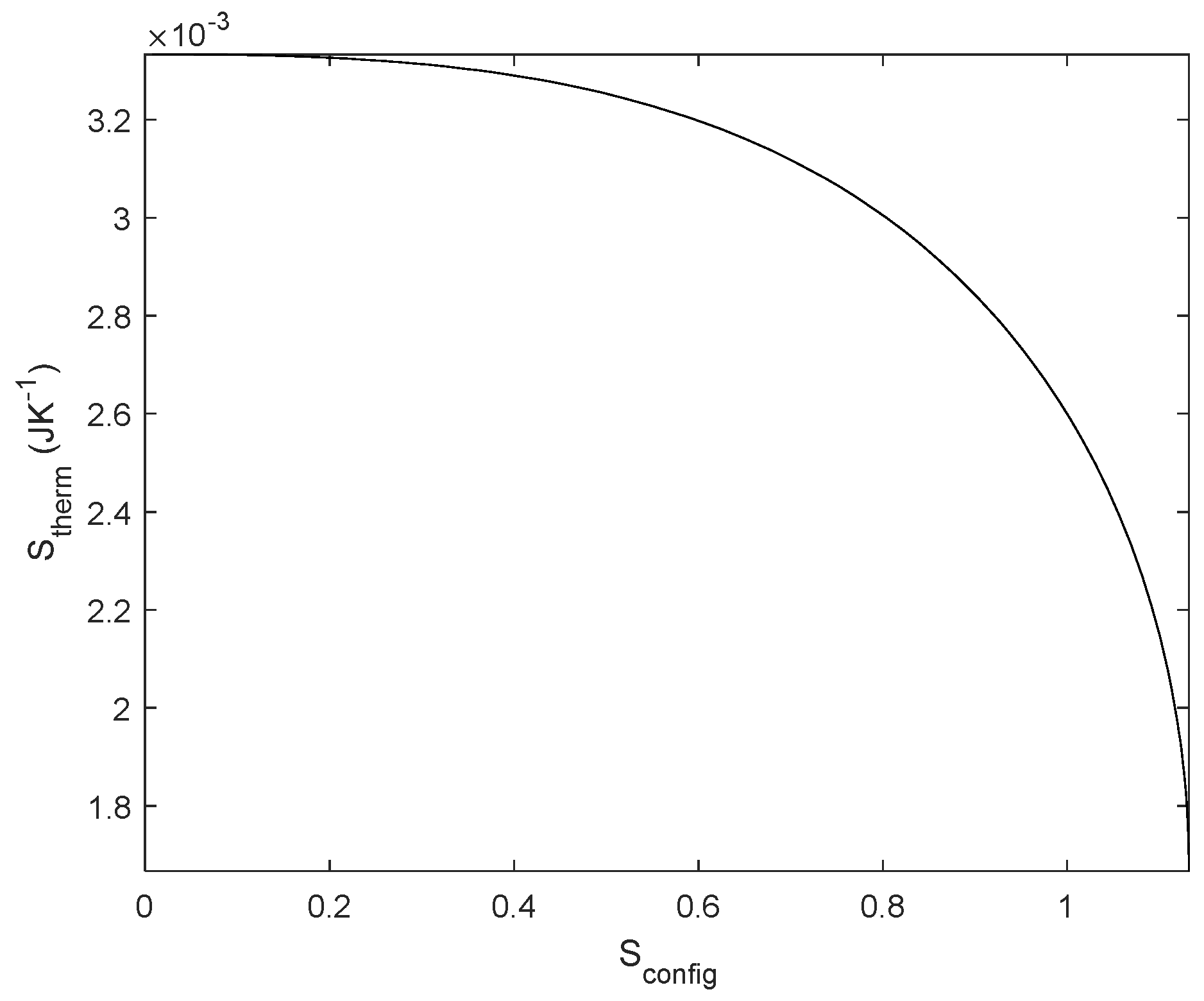

The presence of imaginary entropy in R-C configuration is related to the time-dependent behaviour of the capacitance. However, it is striking that when the real part is maximum, and the imaginary part is zero, the entropy is maximum, which also corresponds to the same impedance modulus of the resistance and the capacitance at the point of maximum power transfer ratio. This behaviour could be further investigated in terms of active and reactive power.

Figure 1.

Current divider with two resistors in parallel. E describes a power source, either of voltage or current.

Figure 1.

Current divider with two resistors in parallel. E describes a power source, either of voltage or current.

Figure 2.

Voltage divider with two resistors in series. E stands either for a voltage or current source.

Figure 2.

Voltage divider with two resistors in series. E stands either for a voltage or current source.

Figure 3.

Equivalent series resistance and capacitor with a power source E.

Figure 3.

Equivalent series resistance and capacitor with a power source E.

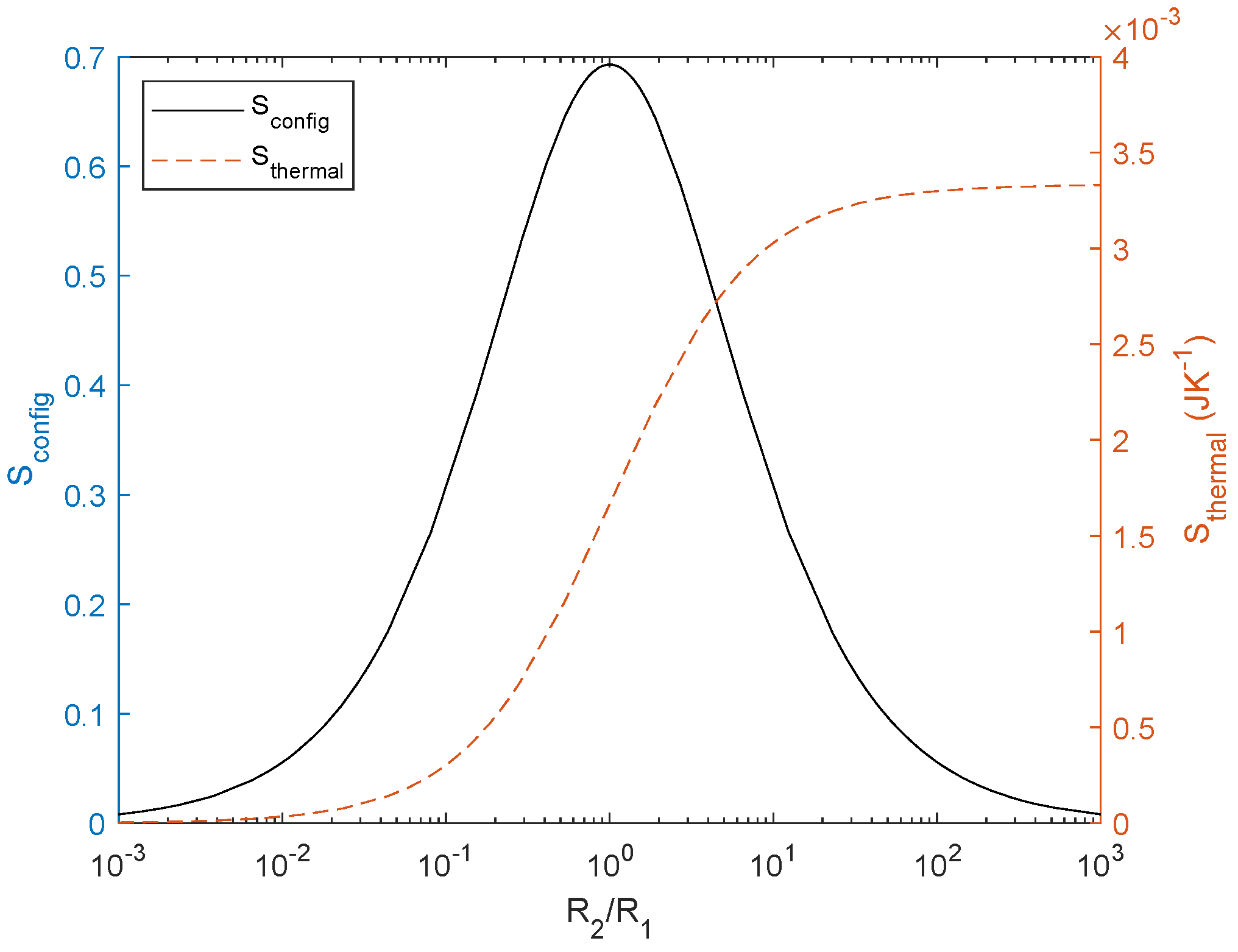

Figure 4.

Configurational entropy (left) and thermal entropy (right) as a function of the normalized resistor ratio for a current source of 1 A and integration time of 1 s. Sconfig maximum is 0.68 for equal resistors and evolve to 0 when the difference between resistors increases. Stherm increases with R2.

Figure 4.

Configurational entropy (left) and thermal entropy (right) as a function of the normalized resistor ratio for a current source of 1 A and integration time of 1 s. Sconfig maximum is 0.68 for equal resistors and evolve to 0 when the difference between resistors increases. Stherm increases with R2.

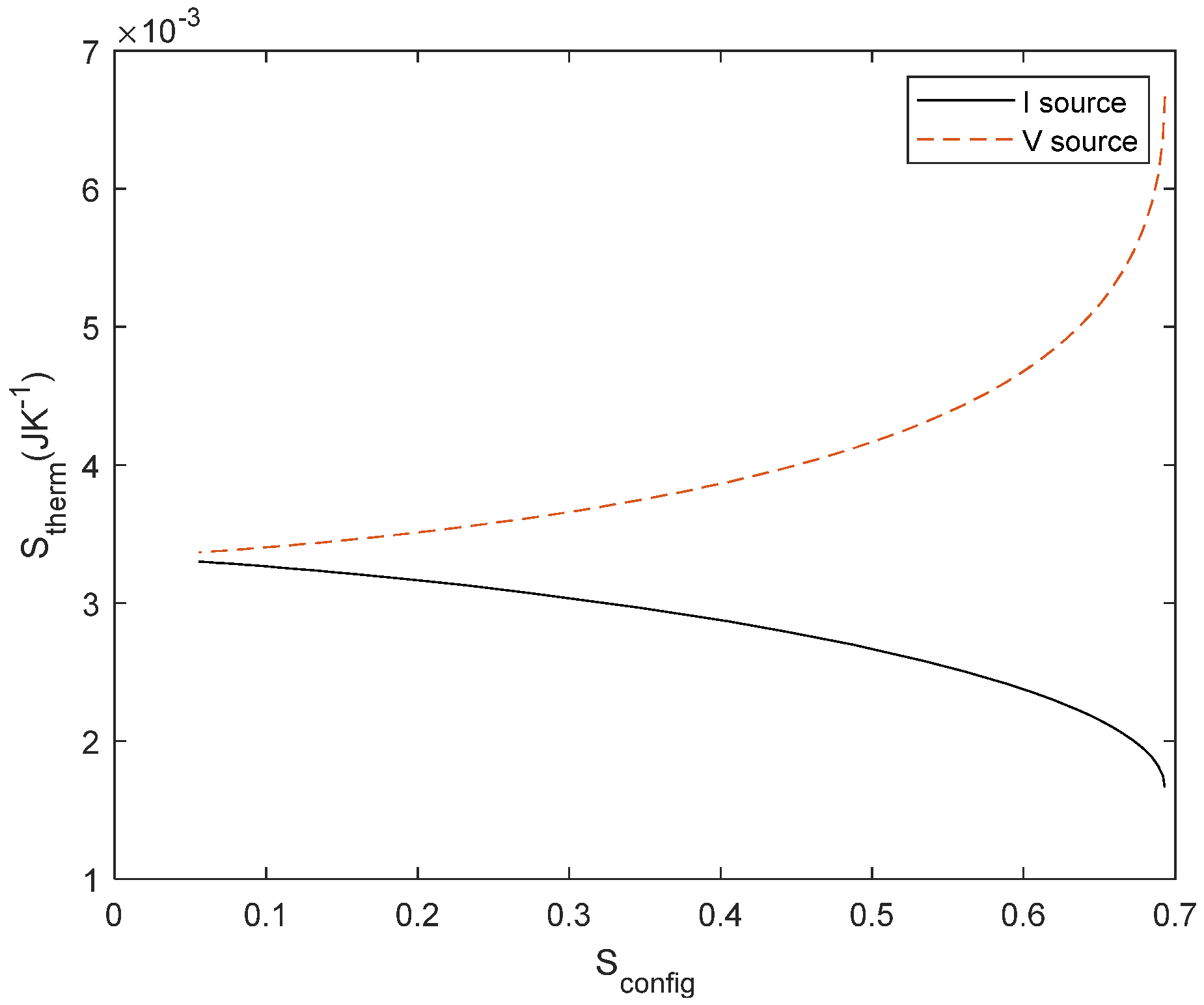

Figure 5.

Thermodynamic entropy vs. Configurational entropy from a normalized current source (1 A, in black) and normalized voltage source (1 V, in red) and integrated for 1 s.

Figure 5.

Thermodynamic entropy vs. Configurational entropy from a normalized current source (1 A, in black) and normalized voltage source (1 V, in red) and integrated for 1 s.

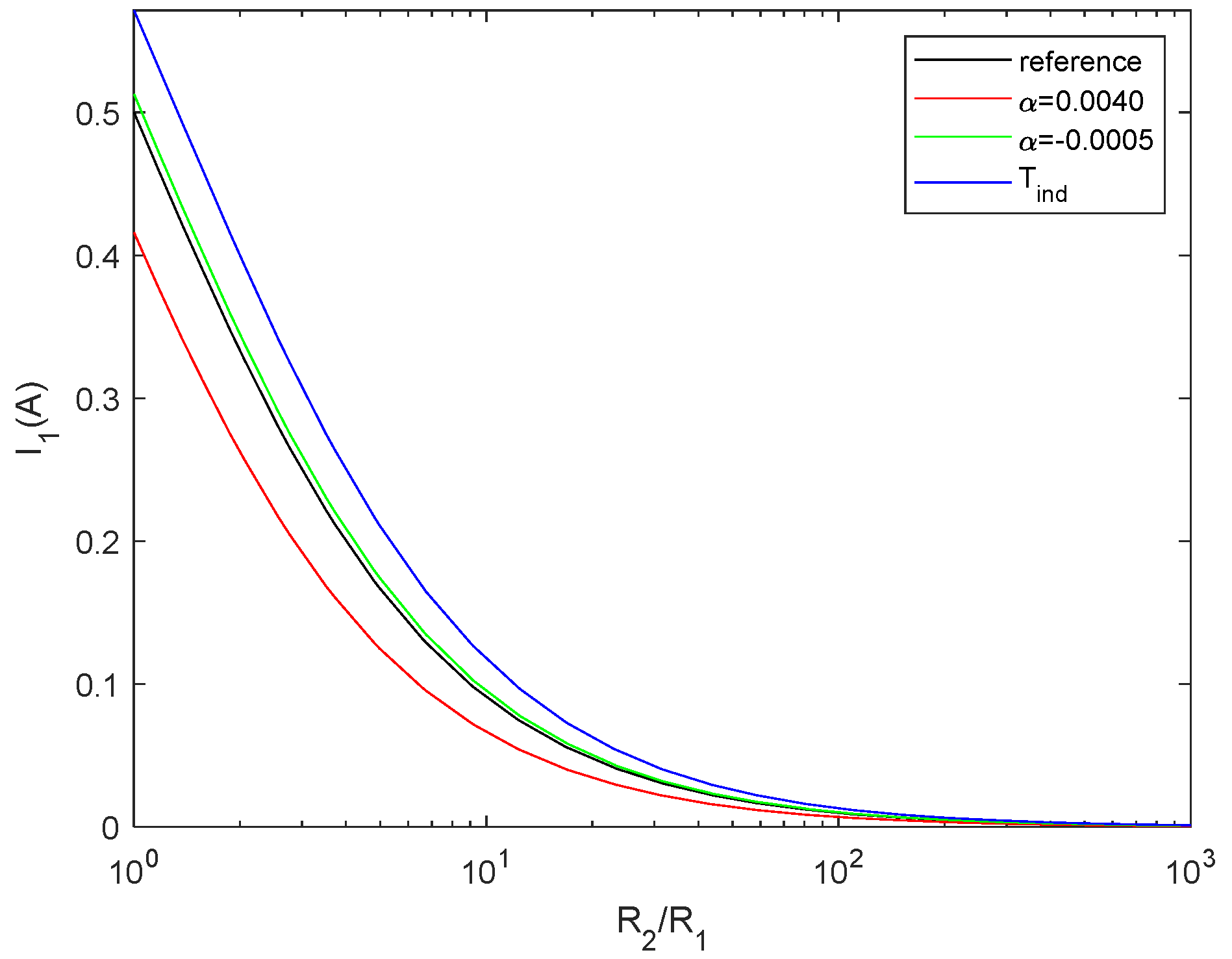

Figure 6.

Current through R2 for reference case (black), temperature-dependent resistor with α = 0.0040 (red), temperature-dependent resistor with α = -0.0005 (green) and temperature-independent resistors (blue). All cases considered T1 = 300 K and T2 = 400 K.

Figure 6.

Current through R2 for reference case (black), temperature-dependent resistor with α = 0.0040 (red), temperature-dependent resistor with α = -0.0005 (green) and temperature-independent resistors (blue). All cases considered T1 = 300 K and T2 = 400 K.

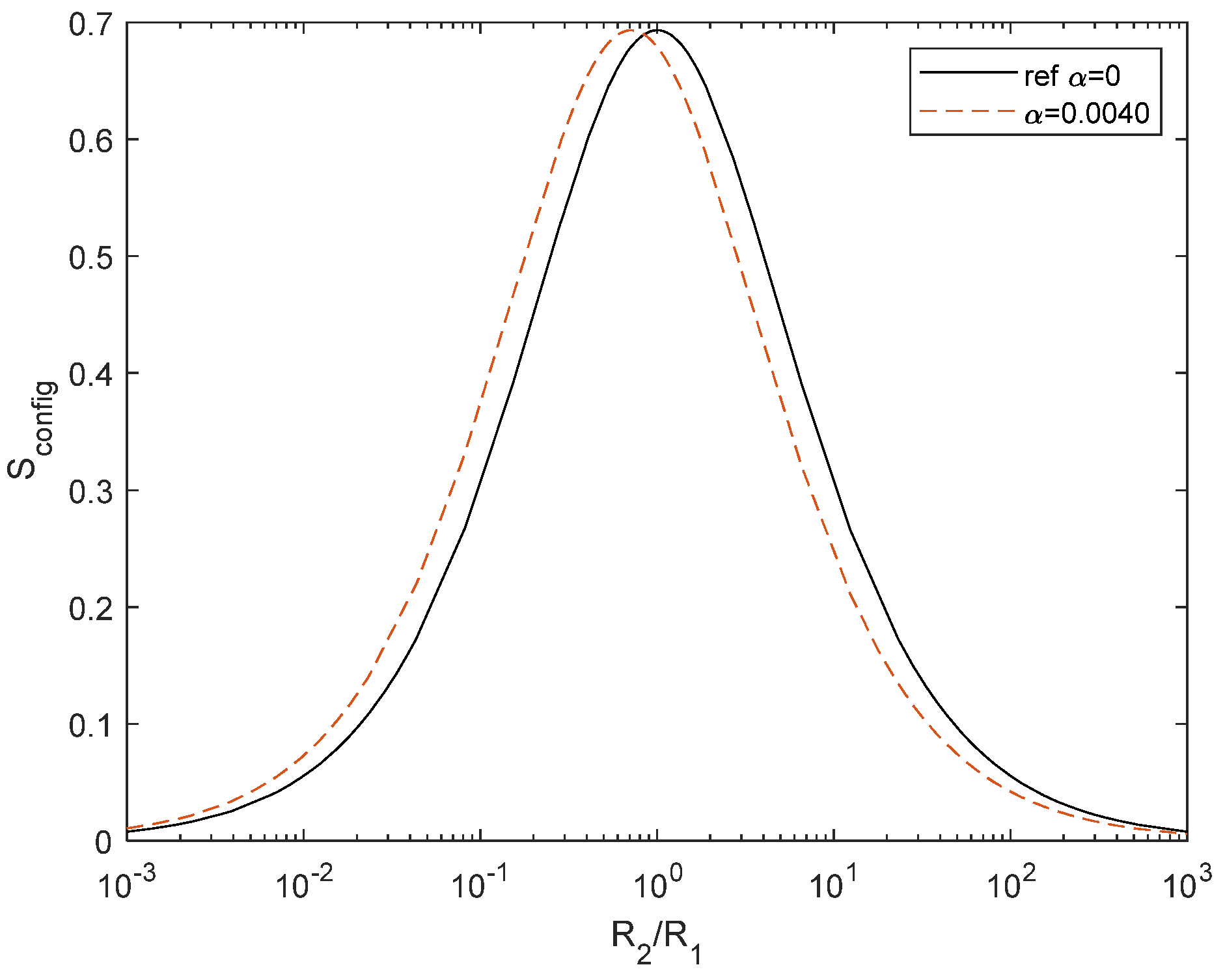

Figure 7.

Sconfig change due to resistance variation on temperature with α = 0.0040 (red) with respect to the reference configuration (black).

Figure 7.

Sconfig change due to resistance variation on temperature with α = 0.0040 (red) with respect to the reference configuration (black).

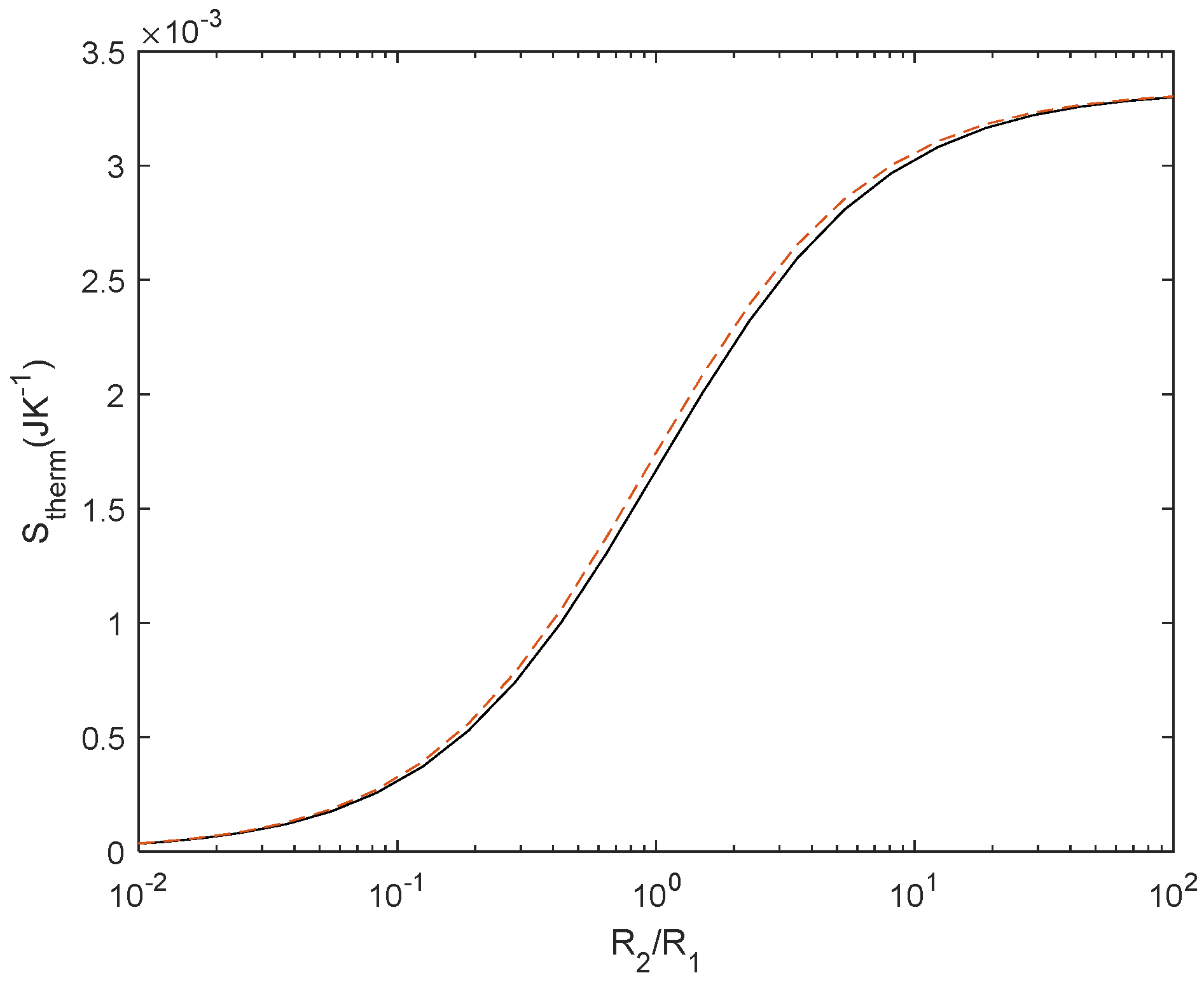

Figure 8.

Stherm for reference case (black) and for temperature-dependent resistor with α = 0.0040 (in red).

Figure 8.

Stherm for reference case (black) and for temperature-dependent resistor with α = 0.0040 (in red).

Figure 9.

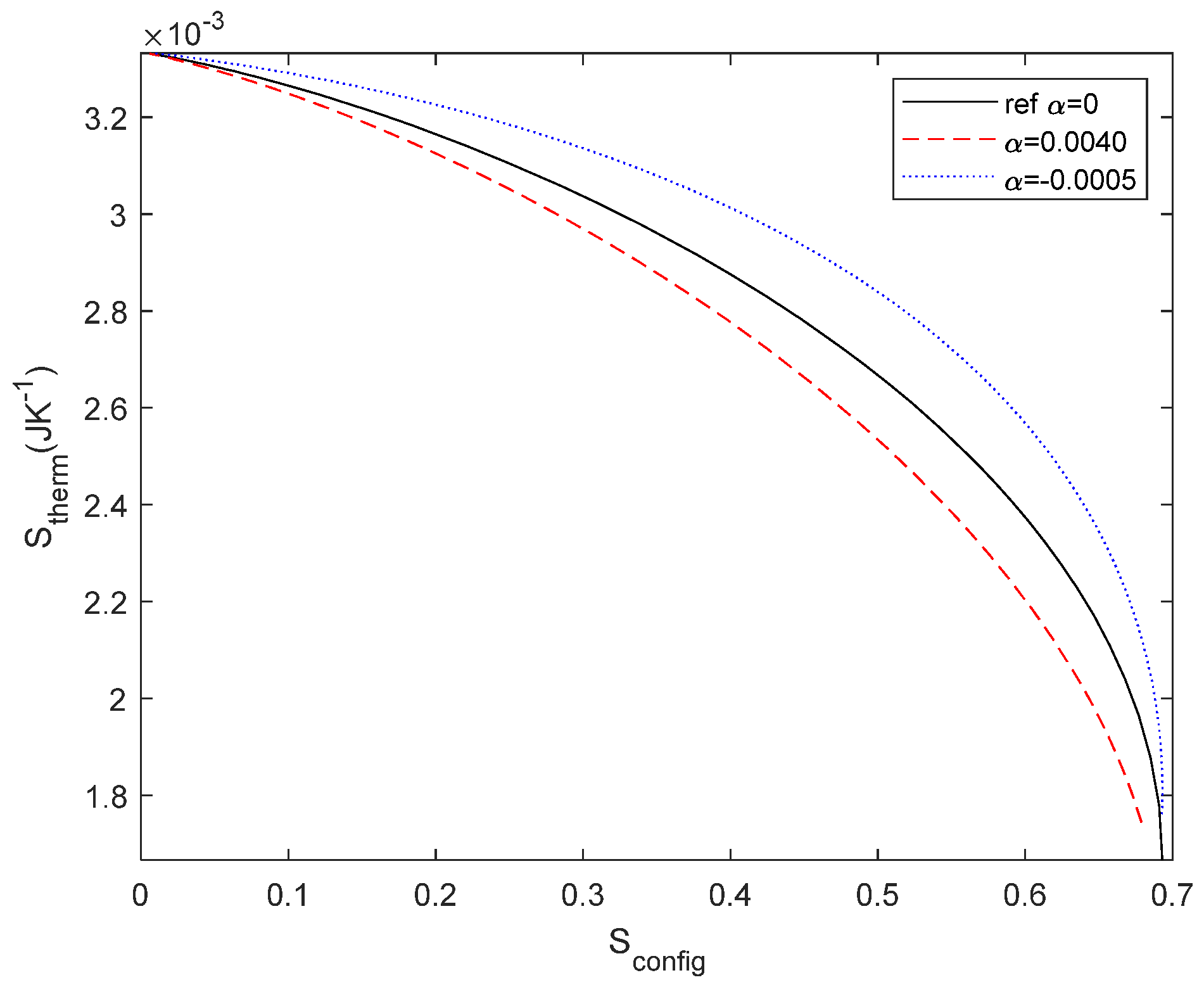

Stherm as a function of Sconfig for reference configuration (black) and thermal-dependent resistor (red) with α = 0.0040 (red), α =-0.0005 (green) for a current source of 1 A. The difference between curves is related to the entropy change of the resistor.

Figure 9.

Stherm as a function of Sconfig for reference configuration (black) and thermal-dependent resistor (red) with α = 0.0040 (red), α =-0.0005 (green) for a current source of 1 A. The difference between curves is related to the entropy change of the resistor.

Figure 10.

Stherm as a function of Sconfig for current source (black) and voltage source (red) for series resistors. The red point of maximum Sconfig and maximum Stherm corresponds to R1 = R2 as described by the maximum power transfer theorem and pointed out with the arrow.

Figure 10.

Stherm as a function of Sconfig for current source (black) and voltage source (red) for series resistors. The red point of maximum Sconfig and maximum Stherm corresponds to R1 = R2 as described by the maximum power transfer theorem and pointed out with the arrow.

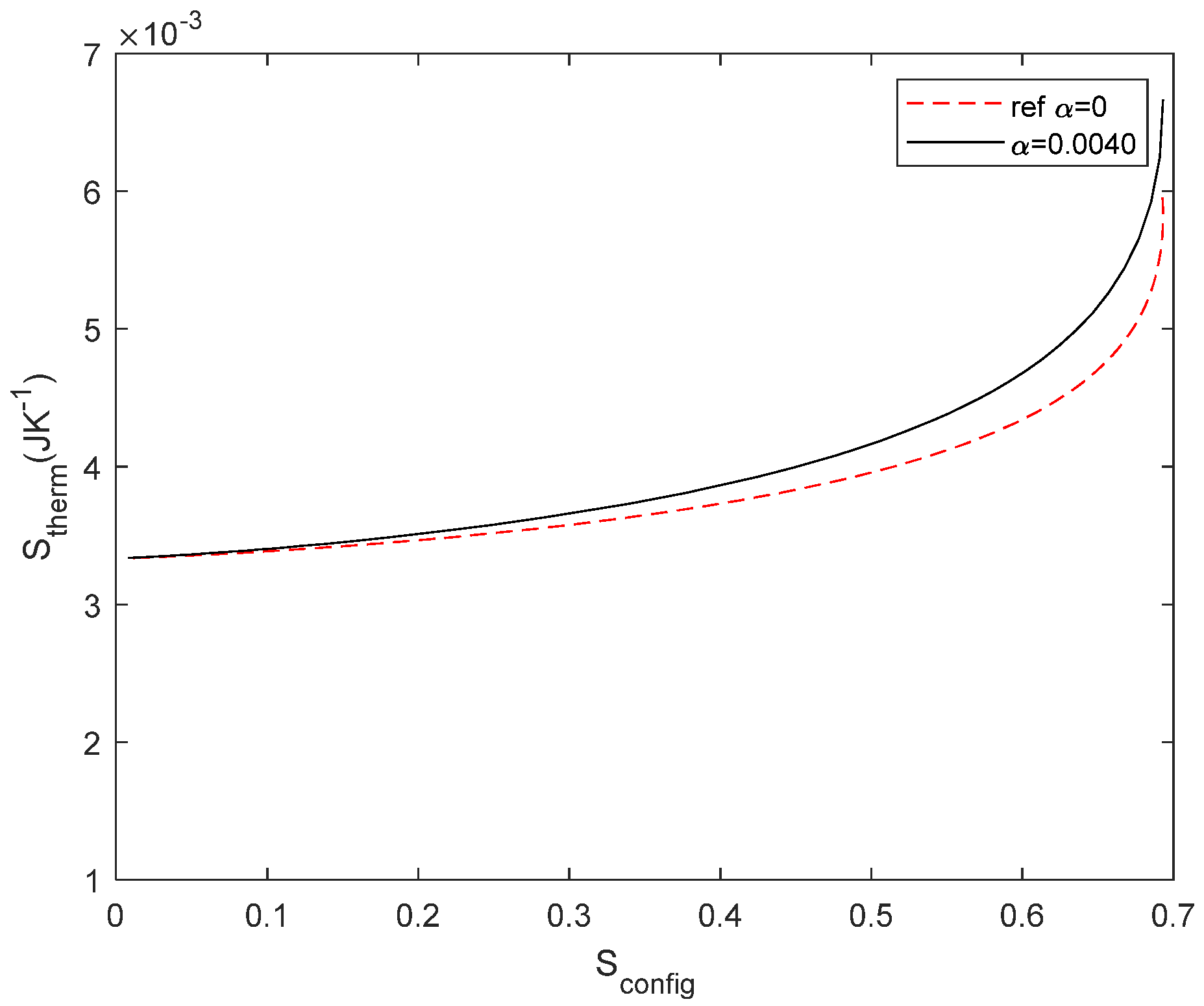

Figure 11.

Stherm as a function of Sconfig for reference configuration (black) and thermal-dependent resistor (red) with α = 0.0040 for a voltage source. The difference between both curves is related to the entropy change of the resistor.

Figure 11.

Stherm as a function of Sconfig for reference configuration (black) and thermal-dependent resistor (red) with α = 0.0040 for a voltage source. The difference between both curves is related to the entropy change of the resistor.

Figure 12.

(a) Tree shape network with three elements (b) Sconfig for 3 resistor circuit. R2 is variable and R3 = 1 Ω (black line) and R3=10 Ω (dashed red line). All other resistors are fixed to 1 Ω. (c) Stherm for the circuit with R3 = 1 Ω (black line) and R3=10 Ω (dashed red line) E = 1 V and (d) Sconfig and Stherm relationship with R3 = 1 Ω (black line) and R3=10 Ω (dashed red line), R2 as a variable and E = 1 V. R symmetry is lost when R3 and R1 are different. The arrows point at the maximum Sconfig.

Figure 12.

(a) Tree shape network with three elements (b) Sconfig for 3 resistor circuit. R2 is variable and R3 = 1 Ω (black line) and R3=10 Ω (dashed red line). All other resistors are fixed to 1 Ω. (c) Stherm for the circuit with R3 = 1 Ω (black line) and R3=10 Ω (dashed red line) E = 1 V and (d) Sconfig and Stherm relationship with R3 = 1 Ω (black line) and R3=10 Ω (dashed red line), R2 as a variable and E = 1 V. R symmetry is lost when R3 and R1 are different. The arrows point at the maximum Sconfig.

Figure 13.

(a) Tree shape network with seven elements (b) Sconfig for 7 resistor circuit. R2 is variable and R3 = 1 Ω (black line) and R3=10 Ω (dashed red line). All other resistors are fixed to 1 Ω. (c) Stherm for the circuit with R3 = 1 Ω (black line) and R3=10 Ω (dashed red line) E = 1 V and (d) Sconfig and Stherm relationship with R3 = 1 Ω (black line) and R3=10 Ω (dashed red line), R2 as a variable and E = 1 V. Symmetry is lost when R3 and R1 are different.

Figure 13.

(a) Tree shape network with seven elements (b) Sconfig for 7 resistor circuit. R2 is variable and R3 = 1 Ω (black line) and R3=10 Ω (dashed red line). All other resistors are fixed to 1 Ω. (c) Stherm for the circuit with R3 = 1 Ω (black line) and R3=10 Ω (dashed red line) E = 1 V and (d) Sconfig and Stherm relationship with R3 = 1 Ω (black line) and R3=10 Ω (dashed red line), R2 as a variable and E = 1 V. Symmetry is lost when R3 and R1 are different.

Figure 14.

Circuit with two voltage sources. In the figure, V2 is in series with R1. We simulated the cases V2 in series with R1 and in series with R2. Sconfig-Sthermal relationship for the reference circuit (V2 = 0) and two sources with V2 in series to R1 (red) and V2 in series to R1, as R2 is the swept variable.

Figure 14.

Circuit with two voltage sources. In the figure, V2 is in series with R1. We simulated the cases V2 in series with R1 and in series with R2. Sconfig-Sthermal relationship for the reference circuit (V2 = 0) and two sources with V2 in series to R1 (red) and V2 in series to R1, as R2 is the swept variable.

Figure 15.

– Modulus of Sconfig as a function of frequency for C = 1 F, R = 1 Ω (Black) and R= 10 Ω (red).

Figure 15.

– Modulus of Sconfig as a function of frequency for C = 1 F, R = 1 Ω (Black) and R= 10 Ω (red).

Figure 16.

Nyquist plot for Sconfig for R = 1 Ω, C = 1 F and 1 mHz < ω < 1 kHz.

Figure 16.

Nyquist plot for Sconfig for R = 1 Ω, C = 1 F and 1 mHz < ω < 1 kHz.

Figure 17.

– Relationship between Sconfig and Stherm for an R-C system (R = 1 Ω, C = 1 F and T = 300 K). A similar behaviour to resistor circuits is found, showing the generality of the method for linear systems.

Figure 17.

– Relationship between Sconfig and Stherm for an R-C system (R = 1 Ω, C = 1 F and T = 300 K). A similar behaviour to resistor circuits is found, showing the generality of the method for linear systems.

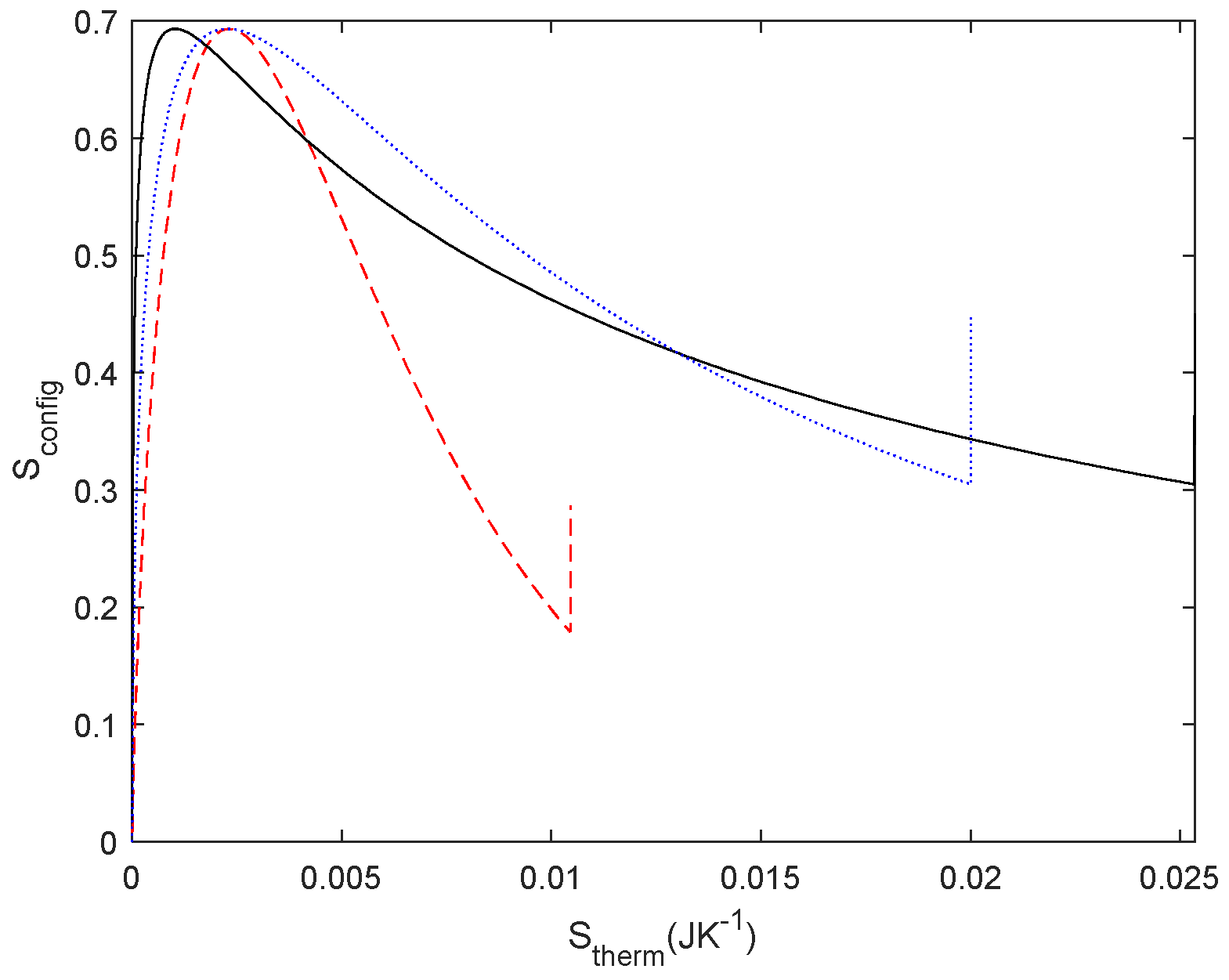

Figure 18.

Time dependent profiles for degradation in a parallel R1//R2 circuit with R1 = 1 Ω, T=300 K and I = 1 A. (a) time evolution of resistor degradation according to Equations (22)–(24) (b) Time dependent evolution of Sconfig (c) Time dependent evolution of Sthermal (d) relationship between Sconfig- Sthermal and (e) relationship between Sconfig and

Figure 18.

Time dependent profiles for degradation in a parallel R1//R2 circuit with R1 = 1 Ω, T=300 K and I = 1 A. (a) time evolution of resistor degradation according to Equations (22)–(24) (b) Time dependent evolution of Sconfig (c) Time dependent evolution of Sthermal (d) relationship between Sconfig- Sthermal and (e) relationship between Sconfig and

Figure 19.

– Relationship between

Stherm –

Sconfig. It is same data of

Figure 18 (d) with the axis exchanged.

Figure 19.

– Relationship between

Stherm –

Sconfig. It is same data of

Figure 18 (d) with the axis exchanged.