1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Magneto Hydrodynamic (MHD) propulsion represents a promising alternative to conventional marine propulsion systems, offering significant environmental benefits. Unlike traditional systems that rely on propellers and combustion engines, MHD propulsion utilizes electromagnetic forces to move a conductive fluid, such as seawater, without moving mechanical parts. By passing an electric current through seawater in the presence of a magnetic field, the system generates thrust through the Lorentz force, propelling the ship forward. This process drastically reduces noise pollution, as there are no mechanical components to create noise underwater, and eliminates harmful emissions associated with fossil fuel combustion, contributing to reduced air pollution.

Despite its advantages, MHD propulsion has not yet gained widespread adoption in commercial shipping. Current applications are limited to experimental naval vessels and small-scale prototypes, as the technology still faces several critical challenges. These challenges primarily revolve around the system’s energy demands, the cost of implementation, and the durability of materials used in the harsh marine environment. Addressing these issues is essential to making MHD propulsion a viable option for commercial and naval shipping industries.

1.2. Problem Statement

The feasibility of MHD propulsion in commercial ships is currently hindered by three major factors:

1.2.1. Energy Requirements:

The need for a substantial amount of electrical energy, particularly to generate powerful magnetic fields, presents a significant barrier. The most practical existing solutions, such as nuclear reactors or large-scale batteries, are not feasible for most commercial vessels due to size, cost, and operational constraints.

1.2.2. Cost

The initial investment and ongoing maintenance costs associated with high-powered electromagnets, energy infrastructure, and specialized materials increase the overall cost of using MHD propulsion. For commercial ships, where operational costs are critical, these expenses limit widespread adoption.

1.2.3. Material Durability

System components, particularly electrodes, are exposed to corrosive seawater and high electric currents, leading to wear and corrosion. Developing durable materials that can withstand these conditions is vital for the long-term operation of MHD propulsion systems.

1.3. Research Objectives

This research aims to evaluate the feasibility of implementing MHD propulsion systems in commercial shipping by addressing the following key questions:

How can the high energy demand of MHD propulsion be met efficiently using available or emerging technologies?

What technological advancements or economic strategies can reduce the overall cost of MHD system implementation?

What new materials or design improvements are necessary to enhance the durability of system components exposed to corrosive marine environments?

By answering these questions, this research seeks to explore the potential for MHD propulsion to become a practical and cost-effective solution for commercial maritime industries.

1.4. Significance

The significance of this research lies in its potential contribution to the future of sustainable marine transportation. Conventional ship propulsion systems, powered by diesel or gas turbines, produce substantial noise and emissions that contribute to marine and atmospheric pollution. As environmental regulations in the shipping industry become stricter, there is a growing need for alternative propulsion technologies that reduce these harmful impacts. MHD propulsion, with its ability to eliminate noise and emissions, offers a forward-looking solution that could revolutionize the shipping industry. However, for it to be viable on a large scale, advancements in energy storage, cost management, and material sciences must be achieved. This research addresses these barriers, providing insight into how MHD propulsion could transition from experimental use to widespread adoption in commercial shipping.

2. Literature Review

This section reviews key contributions in this field of MHD.

- (a)

-

The text

Marine Propellers and Propulsion [

1] provides a comprehensive overview of the advancements and key findings in the development of propulsion systems. Several notable insights regarding these systems are highlighted below:

“The thrust of an MHD drive is proportional to σB2, where σ is the conductivity of the liquid being pumped; in the case of a ship this being sea water. The necessary magnetic fields can be large even by modern standards. For torpedoes with a high-top speed it may be necessary to create fields in the range 15–20 T; however, for ships and submarines at typical speeds the magnetic field can be lower, around 5–10 T.”

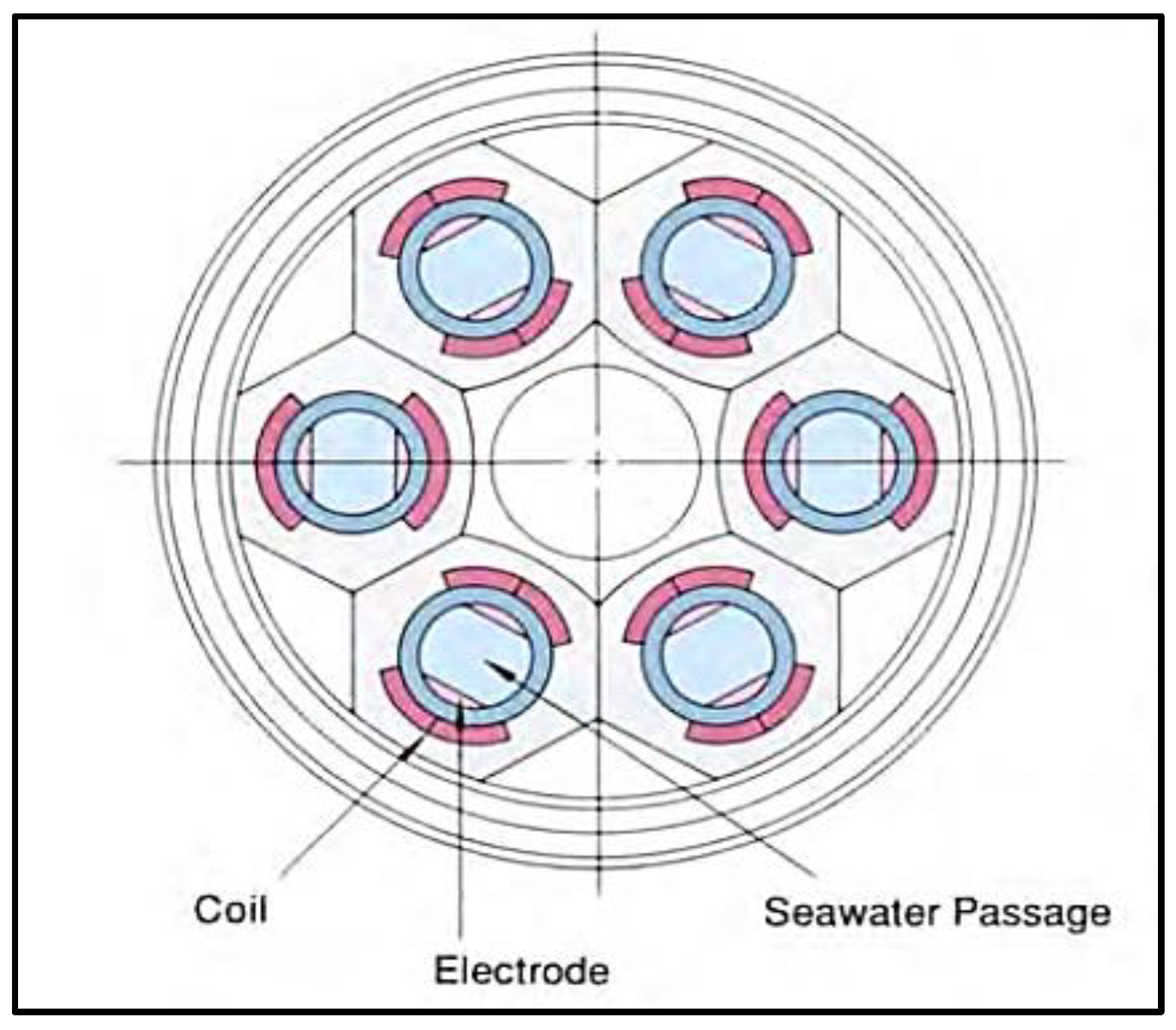

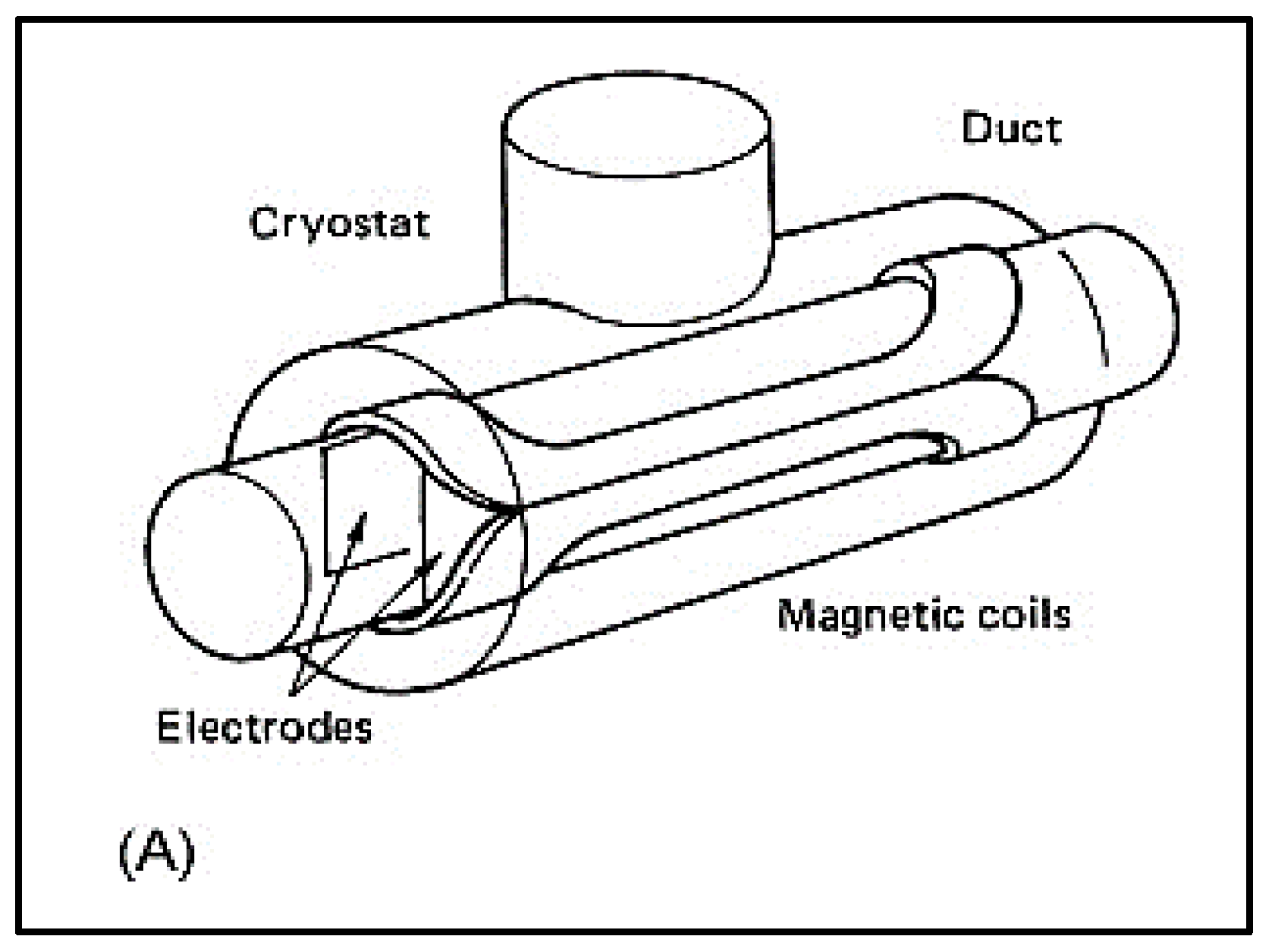

“In theory, the electrical field can be generated either internally or externally, in the latter case by positioning a system of electrodes in the bottom of the ship. This, however, is a relatively inefficient method for ship propulsion and the environmental impact of the internal system is considerably reduced due to the containment of the electromagnetic fields. Most work, therefore, has concentrated on systems using internal magnetic fields and the principle of this type of system is shown in

Figure 1 in which a duct, through which sea water flows, is surrounded by superconducting magnetic coils, which are immersed in a cryostat. Two electrodes are placed inside the duct, which create the electric field necessary to interact with the magnetic field to create the Lorentz forces for propulsion. Nevertheless, the efficiency of a unit is low. The efficiency, however, is proportional to the square of the magnetic flux intensity and to the flow speed, which is a function of ship speed. Consequently, to arrive at a reasonable efficiency, it is necessary to create a strong magnetic flux intensity through the use of powerful magnets.”

“Magnetohydrodynamic propulsion does have certain potential advantages in terms of providing a basis for noise and vibration-free hydrodynamic propulsion. However, a major obstacle to the development of this form of propulsion until relatively recently was that of the design of the superconducting coil and its attendant refrigeration equipment to maintain its zero-resistance property. However, developments in superconductivity have in the last few years shown potential to produce marine propulsion motors using the high-temperature superconductors.”

- (b)

-

The

Yamato-1 [

2], recognized as the world's first superconducting magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) propulsion ship, was developed after six years of research and development, culminating in 1991. This pioneering work led to significant practical advancements, demonstrating the feasibility of MHD propulsion in real-world applications. Several key findings from this research are highlighted below as citations:

“The most important result was gaining the manufacturing technology for a lightweight but large-size superconducting magnet with a stable and strong magnetic field of 4 Tesla with 23 megajoules (MJ).”

“According to the results reached by our group, it seems that ships with such propulsion systems would be justified for commercial operation, if we could raise the magnetic field magnitude of the MHD thruster to 20 to 30 Tesla.”

“Although we used the superconducting coils to create such a magnetic field, it may be possible eventually to use a magnetic field in the form of a permanent magnet if science and technology make progress in this area. Then the hoop stress problem we had to deal with painstakingly in the case of the Yamato-I would be solved more easily.”

“Displacement” is the weight of a ship. A 185-ton displacement in the case of a passenger ship generally means a size large enough to carry 500 passengers comfortably. However, in the case of the Yamato-I, due to its extremely heavy propulsion system and overall related systems, the complement was only 10 people in spite of her 185-ton displacement.

Figure 2.

Cross section of MHD thruster. Source: Adapted from [

2].

Figure 2.

Cross section of MHD thruster. Source: Adapted from [

2].

- (c)

-

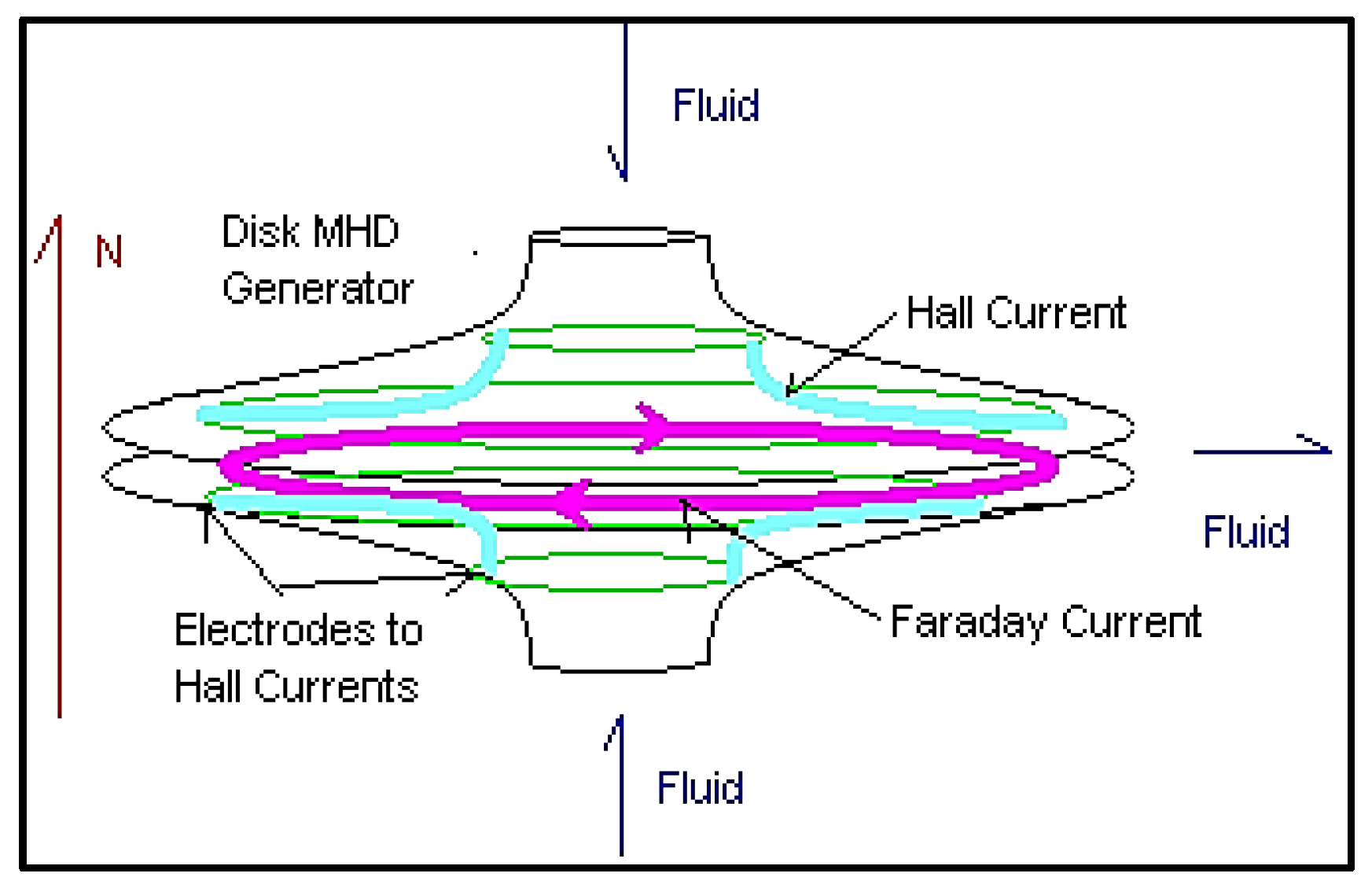

Additionally, another study [

3] explored the benefits of utilizing an efficient magnetic field. The research highlights the advantage of employing a strong magnetic field generated through a disk-shaped generator, as detailed below:

“Another advantage of this design is that the application of the magnetic field is more efficient, has a parallel field configuration, and the working fluid is processed in the magnetic disk closer so that the magnetic strength increases.”

Figure 3.

Disk Generator. Source: Adapted from [

3].

Figure 3.

Disk Generator. Source: Adapted from [

3].

- (d)

-

The principle of superposition, as discussed in the website [

4], explains how the magnetic field generated by an iron core within a solenoid significantly exceeds the magnetic field initially produced by the solenoid itself. This amplification effect is central to understanding the enhanced magnetic field strength in such systems.

-

“It comes down to superposition. The magnetic field generated by the coil is augmented by the magnetic field generated by the core (that itself is caused by the magnetic field from the coil). As the ferromagnetic atoms with their unpaired outer electrons are aligned by the coil’s magnetic field, their own now aligned magnetic fields are added to the field that caused them. In fact, the magnetic field contributed by the core is much stronger than the coil’s magnetic field that ‘triggered’ it.”

Furthermore, in Wikipedia [

6], an idea of how powerful a magnetic field can be created by an iron core is obtainable. It is cited as below:

“Soft (annealed) iron is used in magnetic assemblies, direct current (DC) electromagnets and in some electric motors; and it can create a concentrated field that is as much as 50,000 times more intense than an air core.”

- (e)

-

The study [

6] also highlights that the realization of such ships remaining unfeasible due to the insufficient magnetic field generated:

“For magnets based MHD ships, the strength of the magnets currently available actually limits the efficiency at this order of magnitude. To obtain the same efficiency than conventional propellers, MHD thrusters require compact and light generators of approximately 10 Tesla magnetic fields, which still remains challenging nowadays.”

- (f)

-

Further exploration led to the identification of healthcare devices utilizing strong magnetic fields, as highlighted in [

7]. One such device, developed for magnetic field therapy, employs pulsating electromagnetic fields capable of reaching 4 Tesla in magnitude. This technology is primarily used for pain relief and the treatment of musculoskeletal disorders. The following citation was obtained in support of this finding.

- (g)

-

Subsequent investigations focused on low-field MRI technology, which emerged as a relevant area of interest due to its emphasis on achieving high magnetic field uniformity over large volumes through cost-effective methods, while maintaining minimal weight and size. These objectives aligned closely with our own research goals. To make MRI technology more accessible, particularly given the prohibitive costs associated with traditional high-field MRI systems, numerous studies have been conducted on low-cost MRI solutions. Notably, [

8] documents significant efforts toward the development of affordable low-field MRI systems, with relevant citations provided below.

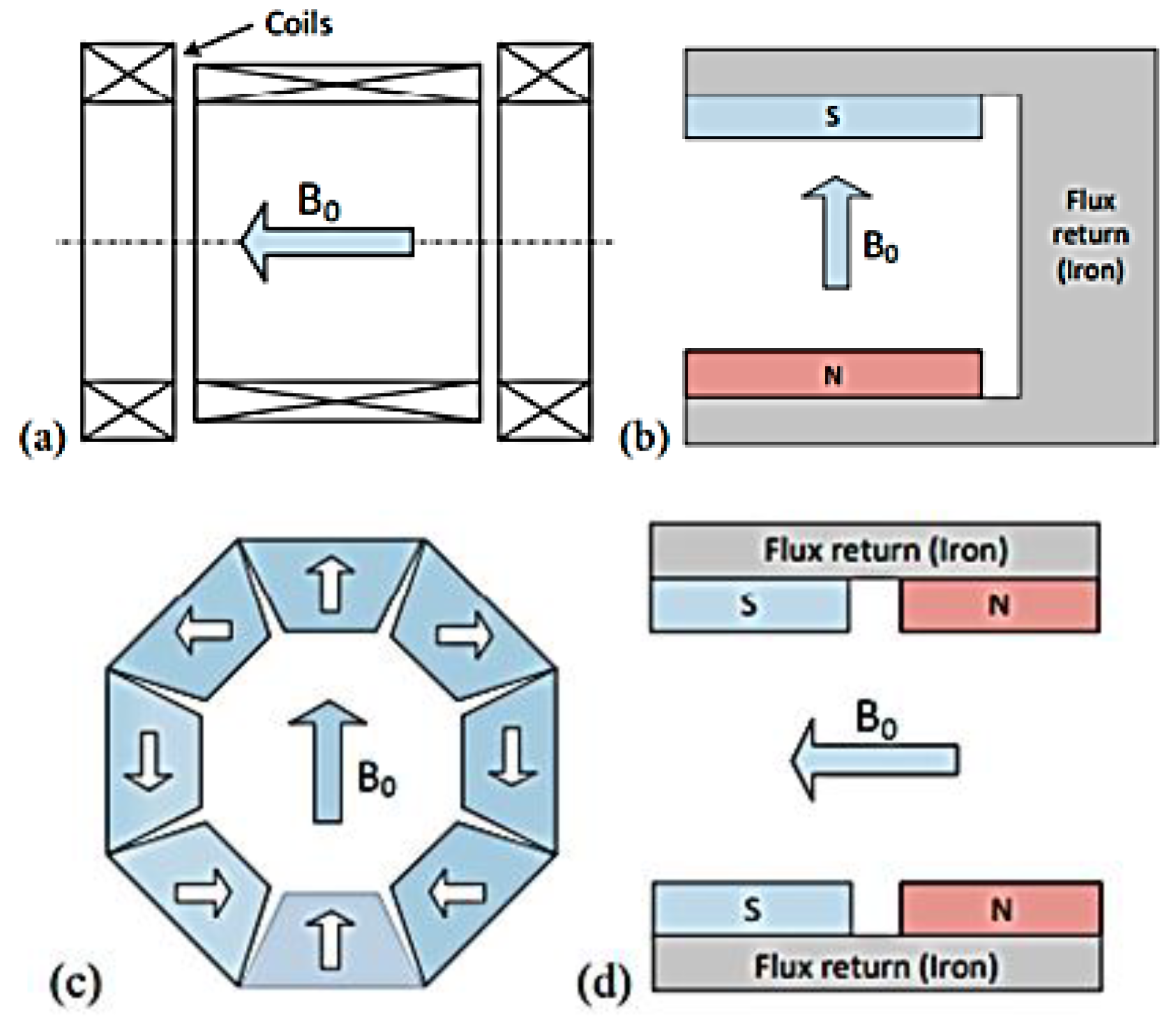

“The basic concept of the new magnet design (Fig. 1d) involves two identical rectangular pole structures, comprising a backing yoke of low-carbon steel on which are mounted magnetized blocks of Neodymium-Boron-Iron (Nd-B-Fe) permanent magnets. The north and the south poles on the two halves of the assembly are arranged to oppose each other symmetrically, thus generating the net magnetic field B0 in the central region between the poles is parallel to the x-axis.”

“The designed field of 0.15 Tesla at an accessible gap of 220 mm was chosen as a realistically achievable target using Nd-B-Fe permanent magnets while having a proven record of providing clinically useful MRI images.

Figure 4.

diagram showing sketches of magnets of types (a) solenoid, (b) conventional open. (c) Halbach Ring and (d) proposed open magnet with field parallel to the pole faces. Source: Adapted from [

8].

Figure 4.

diagram showing sketches of magnets of types (a) solenoid, (b) conventional open. (c) Halbach Ring and (d) proposed open magnet with field parallel to the pole faces. Source: Adapted from [

8].

- (h)

-

Next was a research article [

9] on the design of an efficient electromagnet for homogeneous low field MRI which turned out to be an eye opener. Here the efficiency was improved because of the use of a ferromagnetic housing of 10mm thickness. Maximum achievable field strength was 80mT. Citations offered several insights as below:

“Effective implementation succeeded through the unique use of steel plates as a housing system. This setup increased the effectiveness of the B0 field and eliminated adjacent stray fields. The steel housing serves as a magnetic return circuit, amplifies the generated B0 field, and simultaneously provides several opportunities for shimming (e.g., by using permanent magnets on the outer and inner sides of the housing). In addition, the housing effectively shields interferences and comprises a stable mounting suspension of the magnet coils and gradient system. Another special feature is the compact design of the gradient coil system, which is embedded within the magnet coils and therefore does not require additional space. The system operates at a B0 field strength of 23mT (965 kHz) generated by a 500 W amplifier.”

“At a similar B0 field strength, less power is needed in the presence of such high magnetic susceptibility housing; thus, at a constant total weight, magnetic efficiency increases. For instance, the B0 field decreases from 23 to 6 mT when calculated for the same coil geometry but in the absence of the steel housing.”

“In this paper, we present a low-cost and compact electromagnet that consists of a steel housing with copper coils. The housing was used for field enhancement, homogenization, and shielding. This concept ensures a compromise between large sample volumes, high homogeneity, high B0 field, low power consumption, light weight, simple fabrication, and conserved mobility, without the necessity of a dedicated water-cooling system.”

Figure 5.

Alternative low field MRI design developed for infants. Source: Adapted from [

9].

Figure 5.

Alternative low field MRI design developed for infants. Source: Adapted from [

9].

3. Objectives

From the literature review, it was evident that the most critical factor in making magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) propulsion systems practically feasible is the ability to maintain a strong and uniform magnetic field over a large volume of conducting fluid for extended periods. The challenge of meeting this criterion formed the basis of this research. Existing prototypes and experiments have been constrained by the inability to scale the magnetic field strength sufficiently, which in turn has limited the thrust generated. Overcoming this limitation would significantly enhance the viability of MHD propulsion systems, particularly given their environmentally friendly potential.

For instance, the Yamato-1 [

2] study reported expending 23 million joules of energy to generate a magnetic field of 4 Tesla over a large volume of water. However, achieving this required an extremely heavy propulsion system, which significantly reduced the ship's cargo capacity. Therefore, this research focuses on developing methods to generate such magnetic fields with reduced energy consumption, thereby decreasing associated costs.

4. Research Gaps

Among the various alternatives explored, the use of a hybrid magnetic field has emerged as a promising solution for enhancing magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) propulsion systems. By incorporating permanent magnets, the dependence on large power supplies for generating the necessary electromagnetic fields can be significantly reduced, thus decreasing both energy consumption and operational costs. This approach also addresses the hoop stress issue identified in the Yamato-1 research [

2], thereby improving system feasibility.

Additionally, as demonstrated in [

9], the magnetic field produced by electromagnets in low-field MRI systems (6mT) was substantially increased to 23mT by adding a steel housing, illustrating the beneficial role of ferromagnetic materials in reducing magnetic flux leakage and enhancing overall field strength. The combination of permanent magnets with ferromagnetic materials, when appropriately arranged, can augment or supplement the magnetic fields produced by electromagnets. This method also reduces the reliance on cryogenic cooling systems and the associated energy costs, ultimately improving the ship’s carrying capacity. In other words, the feasibility issue is addressed.

This paper seeks to address this research gap, focusing on the integration of permanent magnets and ferromagnetic materials within hybrid systems to enhance the scalability and practicality of MHD propulsion technology.

5. Opportunities and Constraints

5.1. Technological Opportunities

5.1.1. Environmental Impact:

One of the most promising aspects of Magneto Hydrodynamic (MHD) propulsion systems is their potential to significantly reduce the environmental impact of commercial shipping. Traditional propulsion systems powered by diesel or gas turbines contribute to air pollution through carbon emissions and create noise pollution that can disturb marine life. MHD propulsion, by contrast, generates thrust using electromagnetic fields, eliminating both exhaust emissions and the noise generated by rotating propellers. This makes MHD an attractive option for shipping companies aiming to comply with increasingly strict environmental regulations and to reduce their ecological footprint.

5.1.2. Innovation in Marine Propulsion:

MHD technology presents an opportunity for the marine industry to adopt a revolutionary propulsion system that could redefine ship design and operation. The absence of moving mechanical parts reduces mechanical wear, lowering maintenance requirements and potentially increasing vessel longevity. Furthermore, the ability to generate thrust without relying on conventional fuels opens the door to integrating MHD with renewable energy sources, such as solar or wind power, to create entirely emission-free vessels.

5.1.3. Research and Development:

The ongoing advancements in related fields, such as superconducting materials, energy storage, and material science, present opportunities to overcome many of the current limitations of MHD propulsion. Research into high-temperature superconductors, for example, could lead to more efficient magnetic field generation, reducing energy consumption and making MHD systems more feasible for a wider range of commercial vessels. Similarly, the development of advanced battery technologies or hybrid energy systems could address the high energy requirements, enabling more efficient and longer-range MHD-powered ships.

5.2. Economic and Industrial Constraints

5.2.1. High Initial Costs:

Despite the potential long-term benefits of MHD propulsion, the high upfront costs remain a significant constraint for widespread adoption. The cost of installing high-powered electromagnets, energy generation systems, and advanced cooling infrastructure can be prohibitive for many shipping companies. These expenses are further compounded by the need for advanced materials to withstand corrosion and wear in the harsh marine environment, driving up both initial investment and ongoing maintenance costs.

5.2.2. Energy Supply and Infrastructure:

One of the most critical constraints is the requirement for substantial electrical energy to power MHD systems. Current commercial vessels are not equipped with the necessary infrastructure to support high-energy demands, particularly for long-range journeys. The integration of nuclear reactors, large-scale batteries, or renewable energy systems into commercial ships is still in its experimental stages, and developing cost-effective, scalable energy solutions remains a major hurdle.

5.2.3. Limited Scalability for Smaller Vessels:

While MHD propulsion holds great promise for large vessels or military applications, its scalability for smaller or mid-sized commercial ships remains limited. Smaller vessels often lack the space and weight allowances needed for the large power systems required to drive MHD propulsion. Moreover, the high energy consumption relative to the thrust generated means that MHD technology may not be as efficient for smaller ships, where conventional propulsion methods still offer more cost-effective solutions.

5.3. Material and Durability Constraints

5.3.1. Material Limitations:

One of the primary challenges in MHD propulsion is the durability of system components, particularly those exposed to seawater and high electrical currents. Electrodes, magnets, and other key parts are susceptible to corrosion and material degradation over time, especially in the highly corrosive saltwater environment. Current materials used in MHD systems often require frequent maintenance or replacement, raising operational costs and limiting the long-term viability of the technology.

5.3.2. Advancements in Material Science:

Opportunities lie in the development of new, corrosion-resistant materials that can withstand prolonged exposure to seawater without degrading. Advanced alloys, ceramics, and graphene-based coatings are being explored for their potential to increase the lifespan of MHD components. Innovations in material science, particularly self-healing materials that can repair minor damage autonomously, could further reduce the maintenance requirements and improve the overall durability of MHD systems.

5.4. Regulatory and Market Constraints

5.4.1. Regulatory Challenges:

While MHD propulsion offers significant environmental benefits, regulatory frameworks around the world are not yet fully equipped to handle the integration of this new technology into commercial shipping. Current maritime laws and standards are largely focused on conventional propulsion methods, and the lack of established guidelines for MHD systems may create legal and bureaucratic hurdles for shipping companies looking to adopt the technology. Developing international standards and regulations for MHD propulsion is critical to ensuring its safe and efficient implementation.

5.4.2. Market Demand:

The commercial shipping industry is heavily influenced by cost-efficiency and return on investment. MHD propulsion, in its current form, is not yet seen as a cost-competitive alternative to traditional propulsion systems. Until significant cost reductions are achieved and energy efficiency improves, the market demand for MHD technology is likely to remain limited. However, as environmental regulations become stricter and the demand for greener shipping solutions grows, MHD propulsion could become a more attractive option for shipping companies looking to future-proof their fleets.

5.5. Future Prospects

Despite the constraints, the long-term prospects for MHD propulsion are promising, particularly as advancements in energy storage, materials, and superconducting technology continue to accelerate. The increasing pressure on the shipping industry to reduce carbon emissions and noise pollution will likely drive further investment in MHD research and development. If the key technological and economic barriers can be overcome, MHD propulsion has the potential to transform the future of commercial shipping, offering a cleaner, quieter, and more efficient mode of maritime transportation.

6. Conclusions

6.1. Summary of Key Findings

Magneto Hydrodynamic (MHD) propulsion offers a highly innovative and environmentally sustainable alternative to traditional marine propulsion systems. The absence of moving parts and reliance on electromagnetic fields to generate thrust allows for significant reductions in noise pollution and the complete elimination of harmful exhaust emissions, aligning with the growing global emphasis on greener shipping solutions. However, the practical implementation of MHD technology in commercial ships faces several critical challenges, including the substantial energy demands, high installation and maintenance costs, and the material durability required to operate efficiently in a corrosive marine environment. This research investigates the challenges associated with the development of magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) propulsion systems and identifies potential solutions, drawing parallels from advancements in magnetic field generation within MRI technologies. The findings suggest that further refinement of these methodologies holds significant promise for improving MHD propulsion systems, in addition to the use of high-temperature superconducting (HTS) magnets.

6.2. Implications for the Future

The environmental benefits of MHD propulsion make it an attractive option for the future of the shipping industry, particularly as environmental regulations become stricter. The potential for quiet, emission-free propulsion systems could revolutionize both commercial and naval applications, improving the sustainability and ecological footprint of global maritime transportation. In particular, MHD propulsion systems could play a pivotal role in reducing marine noise pollution, a growing concern as shipping traffic continues to increase.

Furthermore, the development of hybrid propulsion systems that combine MHD with traditional engines or renewable energy sources could bridge the gap between the current limitations and the future potential of MHD technology. This hybrid approach would allow shipping companies to adopt MHD for low-speed or noise-sensitive operations while relying on conventional methods for high-speed or long-distance travel.

6.3. Recommendations for Further Research

To fully realize the potential of MHD propulsion, several areas of research require further investigation:

6.3.1. Energy Efficiency:

Continued exploration of advanced energy storage systems, including high-capacity batteries, renewable energy integration, and superconducting technologies, is essential to addressing the high energy demands of MHD propulsion. Research into more compact and cost-effective power systems will be crucial for making MHD a viable option for a broader range of vessels.

6.3.2. Cost Reduction Strategies:

Further development of scalable production techniques, along with government incentives and subsidies, could help lower the financial barriers to adopting MHD propulsion. Research into cost-effective superconducting magnets and mass production techniques will play a key role in reducing the overall cost of implementing this technology.

6.3.3. Material Durability:

Advancements in corrosion-resistant alloys, ceramics, graphene coatings, and self-healing materials are necessary to extend the operational lifespan of MHD propulsion components. Material science research will be critical to reducing maintenance costs and improving the reliability of MHD systems.

6.3.4. Regulatory Frameworks:

International maritime regulatory bodies must begin developing guidelines and standards for MHD propulsion technology to facilitate its integration into the shipping industry. Collaborative efforts between researchers, governments, and the shipping industry will be essential to ensure the safe and efficient adoption of MHD propulsion.

6.4. Concluding Remarks

MHD propulsion represents a transformative opportunity for the maritime industry, with the potential to significantly reduce environmental impact while enhancing the efficiency of marine transportation. However, realizing this potential will require sustained research, technological advancements, and collaboration across various sectors. As innovations in energy, cost management, and material science continue to evolve, the future of MHD propulsion looks increasingly promising. With the right investments and breakthroughs, MHD technology could become a cornerstone of sustainable marine propulsion, contributing to a quieter, cleaner, and more efficient global shipping industry.

References

- J.S. Carlton FREng, Marine Propellers and Propulsion (Fourth Edition): Elsevier Ltd., 2019. [CrossRef]

- Under editorial Supervision of Yohei Sasakawa n.d. “Yamato-1”. 21 September. https://www.spf.org/en/_opri_media/publication/docs/yamato-1.pdf# (accessed on 21 September 2024).

- Wiwik Purwati W (1), Slamet Priyo Atmojo (2), Margana (3), Suwarti (4), Budhi Prasetiyo (5), Ikhwatinah Khoiroh (6), Performance of Magneto Hydro Dynamic (MHD) as a Power Generation Support Tool: Eksergi, Vol. 18, No. 2. May 2022. [CrossRef]

- Robin Bornoff, “Demystifying Electromagnetics, Part 5 – Ferromagnetic Cores”, blogs.sw.siemens.com, June 14, 2021. [Online]. Available: https://blogs.sw.siemens.com/simulating-the-real-world/2021/06/14/demystifying-electromagnetics-part-5-ferromagnetic-cores/ (accessed on 22 September 2024).

- “Magnetic core”, en.wikipedia.org/, Last edited on 4 July 2024. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Magnetic_core (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- David Cébron, Sylvain Viroulet, Jérémie Vidal, Jean-Paul Masson, Philippe Viroulet, “Experimental and Theoretical Study of Magnetohydrodynamic Ship Models”: HAL, 5 Jul 2017. [CrossRef]

- “4T-Magnetic field therapy”, https://tom-mallorca.com/en/. [Online]. Available: https://tom-mallorca.com/en/treatments/4t-therapy/ (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- John V.M. McGinley, Mihailo Ristic ⇑, Ian R. Young, A permanent MRI magnet for magic angle imaging having its field parallel to the poles, Journal of Magnetic Resonance 271 (2016) 60–67: Elsevier Ltd. [CrossRef]

- Steffen Lother, Steven J. Schiff, Thomas Neuberger, Peter M. Jakob, Florian Fidler, Design of a mobile, homogeneous, and efficient electromagnet with a large field of view for neonatal low field MRI, Magnetic Resonance Materials in Physics: ESMRMB 2016. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).