Submitted:

02 September 2024

Posted:

03 September 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results and Discussion

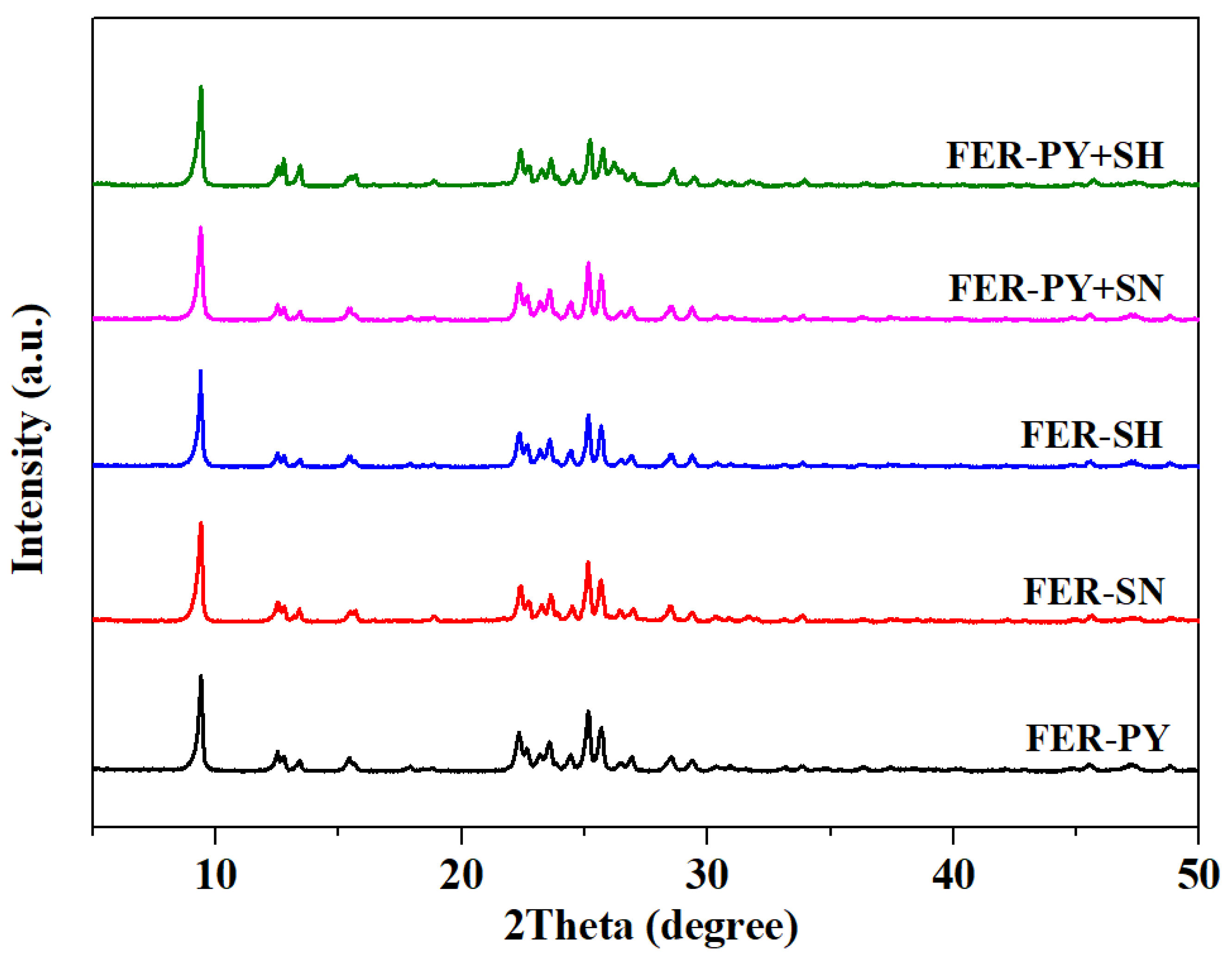

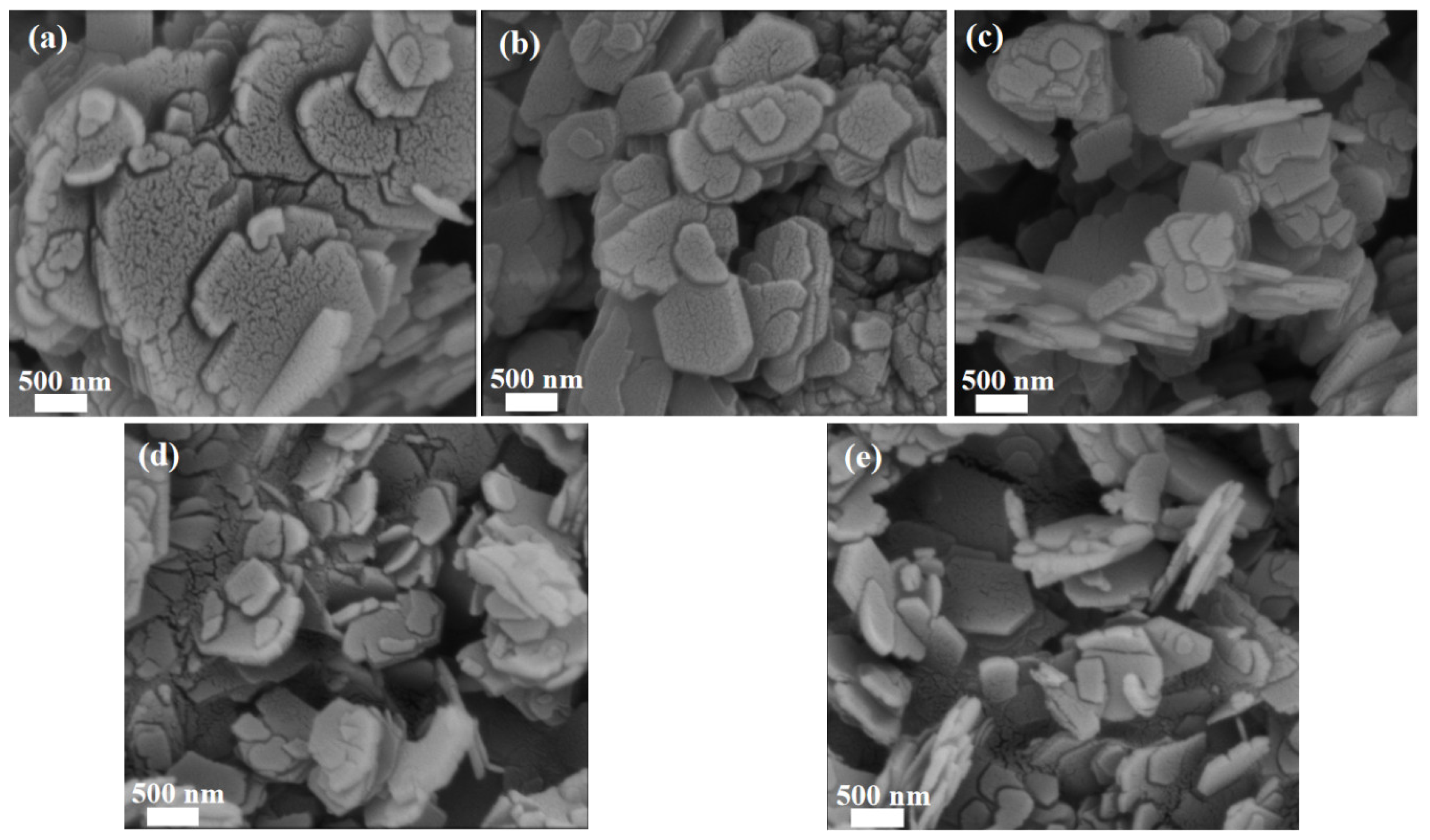

2.1. Structural and Textural Properties

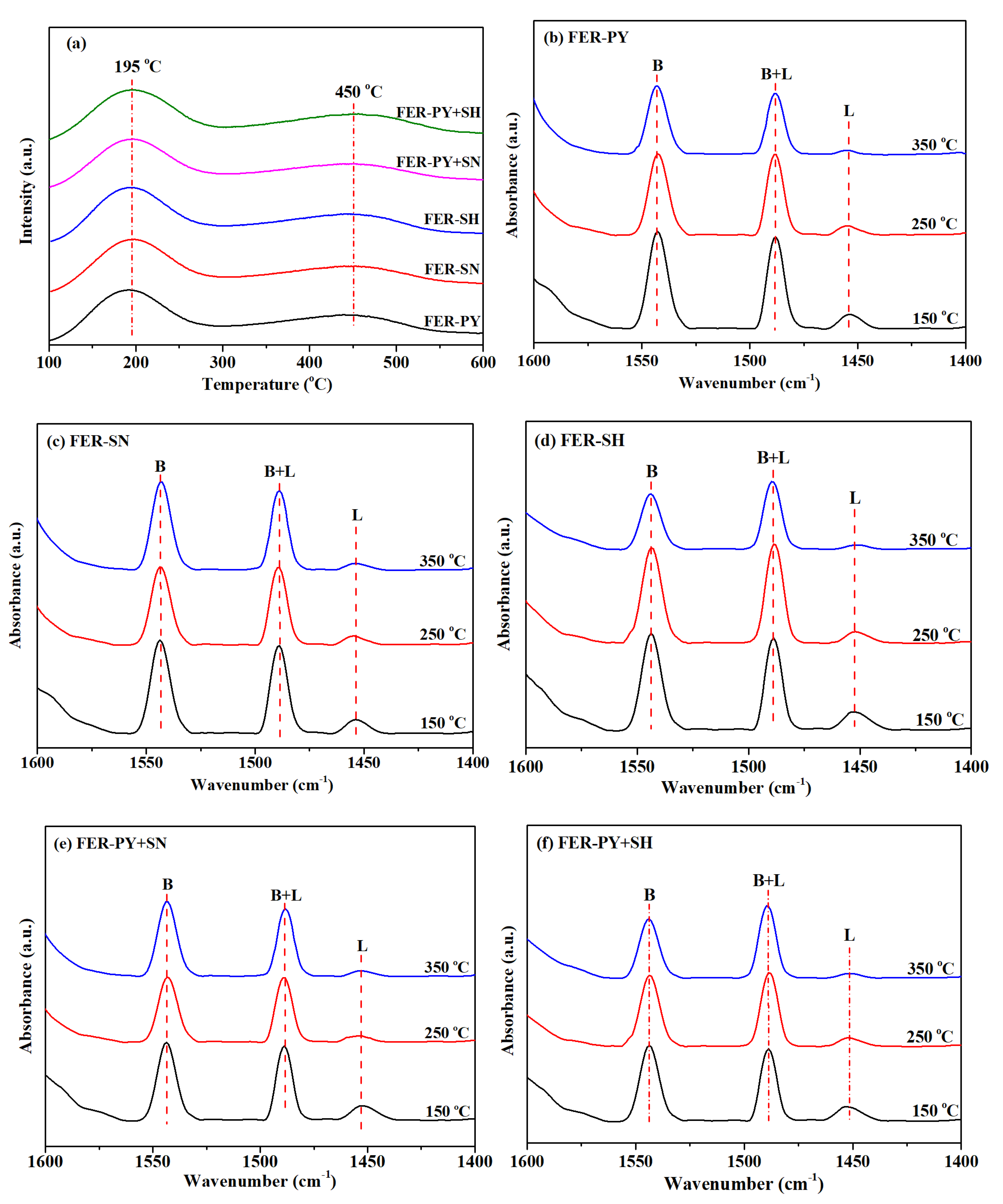

2.2. Acidity Characterization

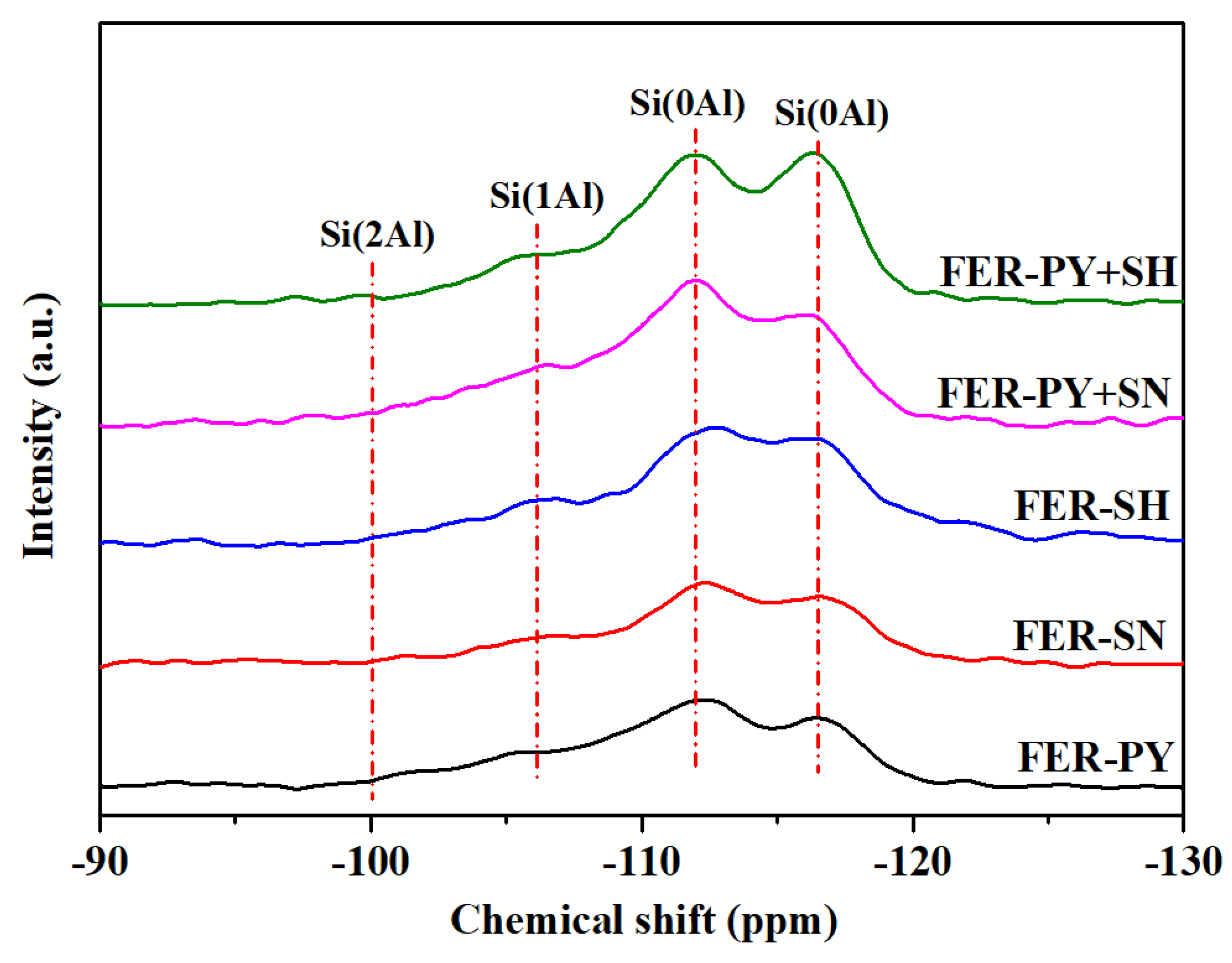

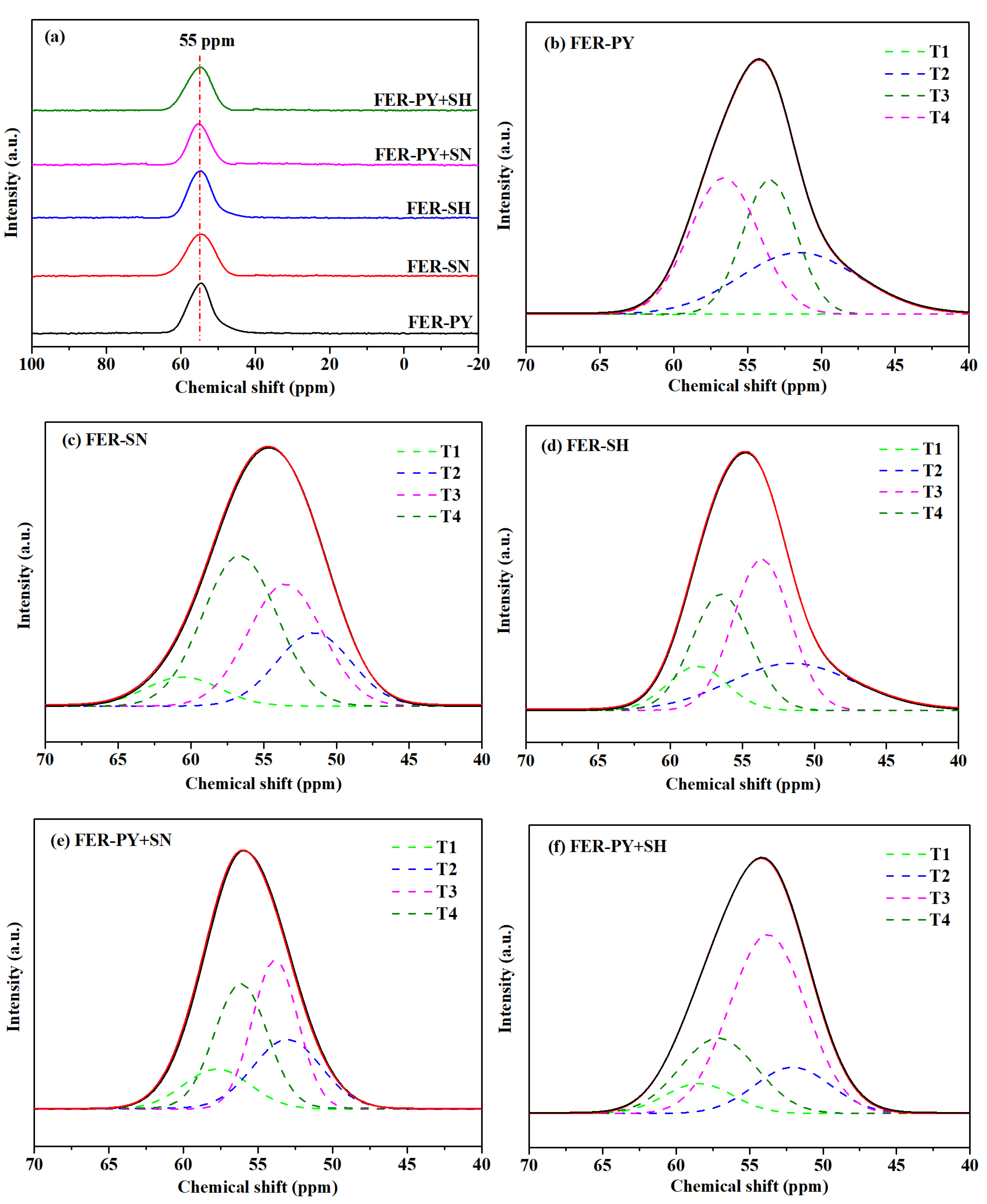

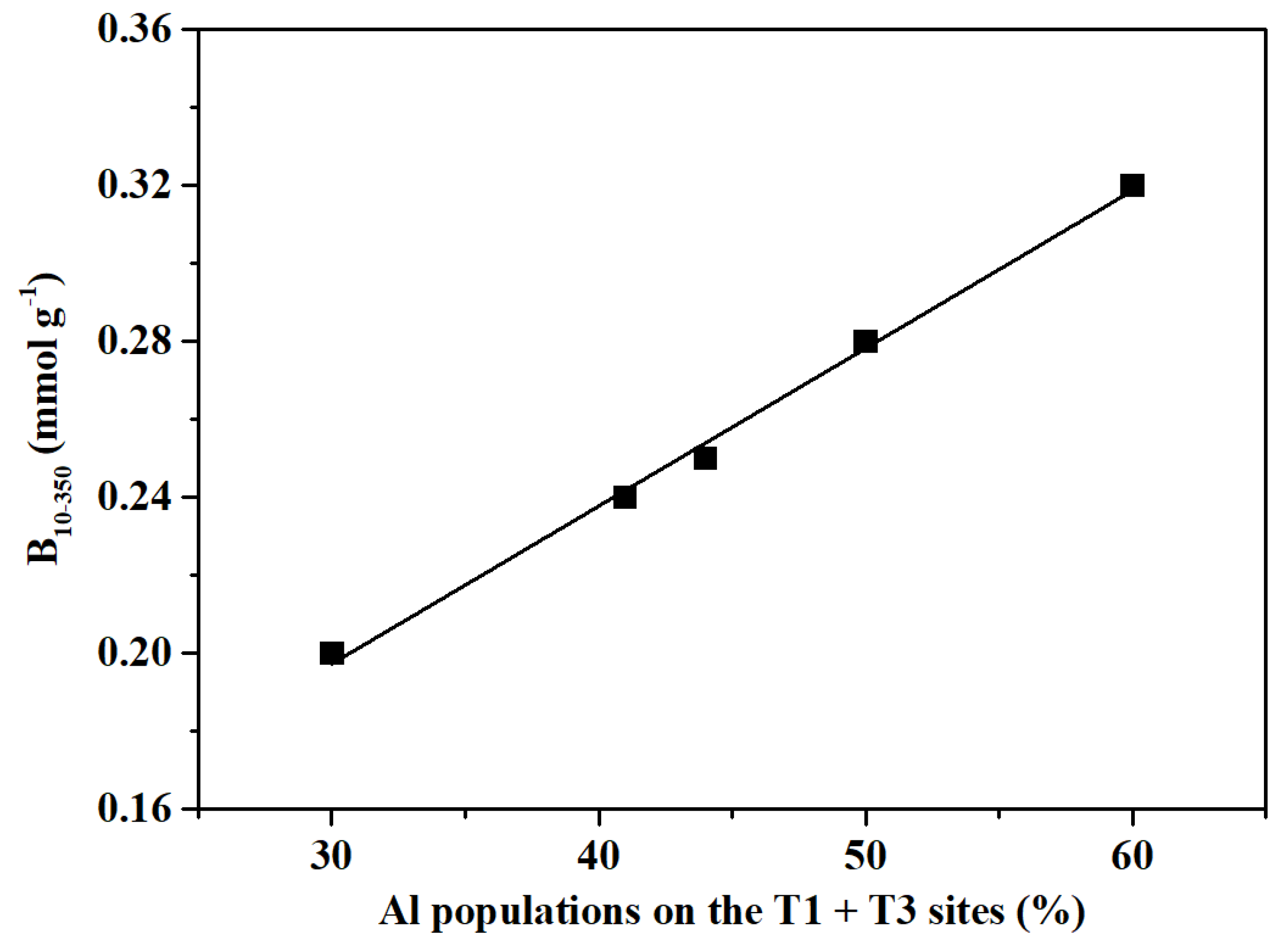

2.3. 29Si and 27Al MAS NMR

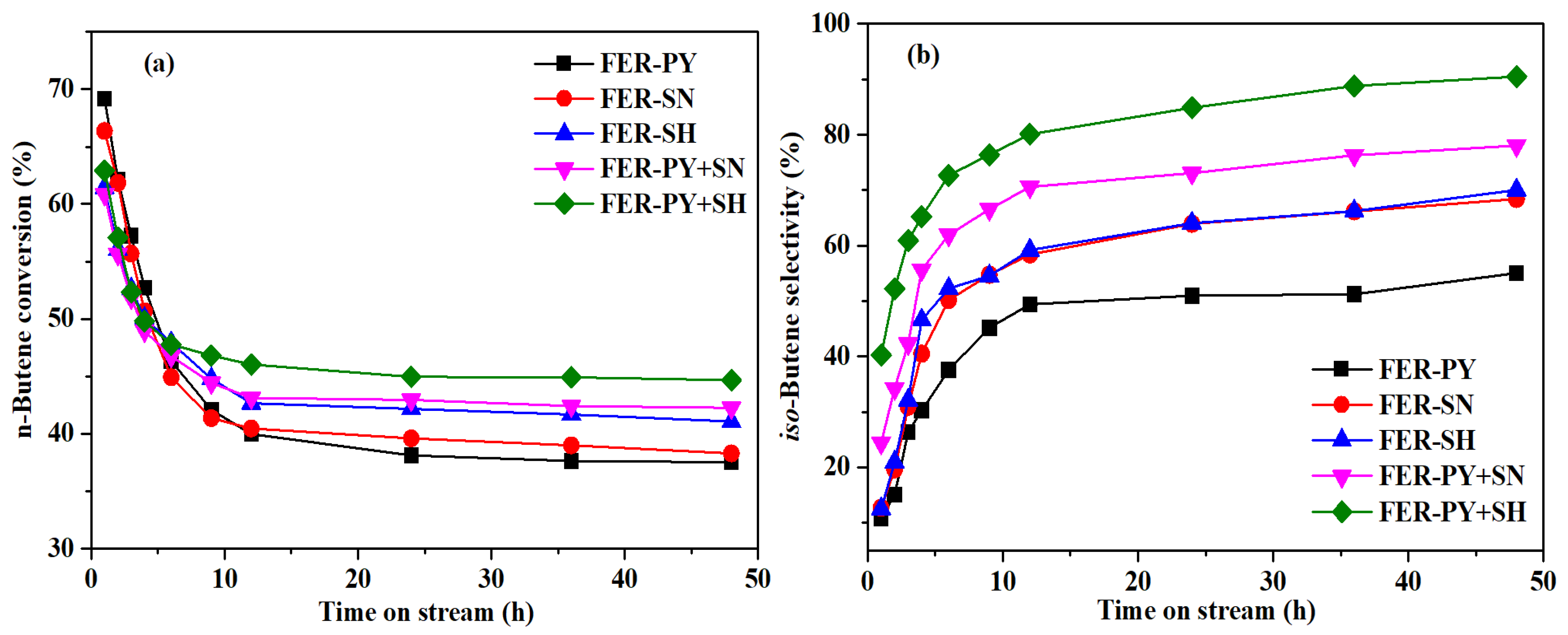

2.4. Catalytic Performance

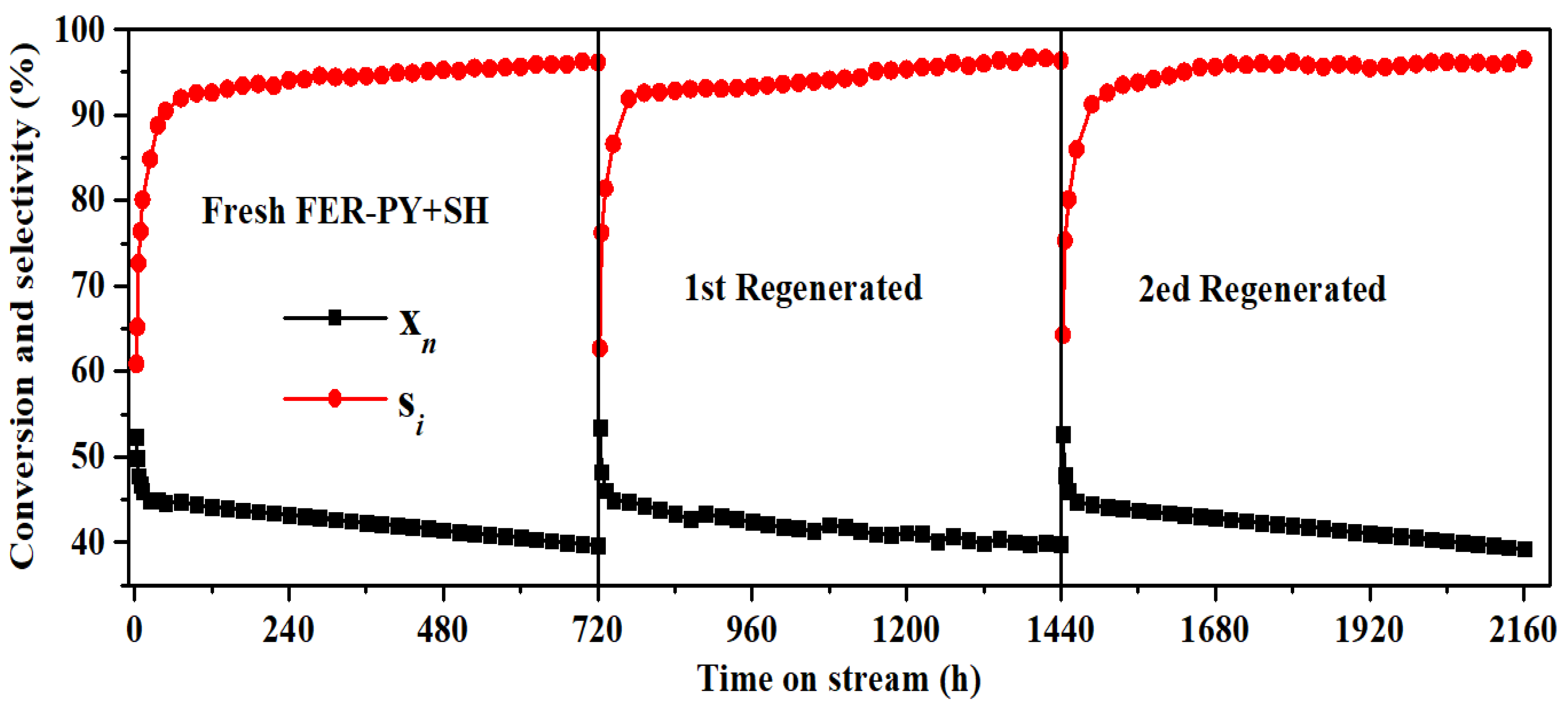

2.5. Catalyst Stability

3. Experimental

3.1. Materials

3.2. Preparation of FER-X Zeolites

3.2.1. Preparation of Seeds

3.2.2. Preparation of Seed-Derived FER-X zeolites

3.2.3. Preparation of H-form FER zeolites

3.3. Characterization of Catalysts

3.4. Catalyst Evaluation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Heriberto Díaz Velázquez, Likhanova N, Aljammal N,et al. New Insights into the Progress on the Isobutane/Butene Alkylation Reaction and Related Processes for High-Quality Fuel Production. A Critical Review[J]. Energy & Fuels 2020, 34, 15525–15556. [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q, Yang W, Chen Z; et al. Formation and regeneration of shape-selective ZSM-35 catalysts for n-Butene skeletal isomerization to isobutylene[J]. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 8202–8211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corma, A. Inorganic solid acids and their use in acid-catalyzed hydrocarbon reactions[J]. Chemical Reviews 1995, 95, 559–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houzvicka J, Ponec V. Skeletal isomerization of n -Butenes[J]. Catalysis Reviews. Science and Engineering 1997, 39, 319–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul M, Naccache C. Skeletal isomerisation of n-butenes catalyzed by medium-pore zeolites and aluminophosphates[J]. Advances in Catalysis 2010, 31, 505–543. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan P, A. The crystal structure of the zeolite ferrierite[J]. Acta Crystallographica, 1966, 21, 983–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu H, Zhu J, Zhu L, Zhou E, Shen C. Advances in the synthesis of ferrierite zeolite[J]. Molecules 2020, 25, 3722–3739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooiweer H H, de Jong K P, Kraushaar-Czarnetzki B, Stork W H J, Krutzen B C H. Skeletal isomerisation of olefins with the zeolite ferrierite as catalyst[J]. Studies in Surface Science and Catalysis 1994, 84, 2327–2334. [Google Scholar]

- Wichterlová B, Ilkova N, Uvarova E; et al. Effect of Broensted and Lewis sites in ferrierites on skeletal isomerization of n-Butenes[J]. Applied Catalysis A General 1999, 182, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domokos L, Lefferts L, Seshan K; et al. The importance of acid site locations for n-Butene skeletal isomerization on ferrierite[J]. Journal of Molecular Catalysis A Chemical 2000, 162, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinar A B, Márquez-álvarez C, Grande-Casas M; et al. Template-controlled acidity and catalytic activity of ferrierite crystals[J]. Journal of Catalysis 2009, 263, 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo G, Jeong H S, Hong S B; et al. Skeletal isomerization of 1-Butene over ferrierite and ZSM-5 zeolites: Influence of zeolite acidity[J]. Catalysis Letters 1996, 36, 249–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donk S V, Bus E, Broersma A; et al. Probing the accessible sites for n-Butene skeletal isomerization over aged and selective H-Ferrierite with d3-acetonitrile[J]. Journal of Catalysis 2002, 212, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corma, A. From Microporous to Mesoporous Molecular Sieve Materials and Their Use in Catalysis[J]. Chem. ReV. 1997, 97, 2373–2420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li J, Gao M, Yan W; et al. Regulation of the Si/Al ratios and Al distributions of zeolites and their impact on properties[J]. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 1935–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mercedes,B; Corma A. What Is Measured When Measuring Acidity in Zeolites with Probe Molecules?[J]. ACS Catalysis 2019, 9, 1539–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palcic A V, V. Analysis and control of acid sites in zeolites[J]. Applied Catalysis, A. General: An International Journal Devoted to Catalytic Science and Its Applications 2020, 606, 117795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong Z P, Qi G D, Bai L Y; et al. Preferential population of Al atoms at the T4 site of ZSM-35 for the carbonylation of dimethylether[J]. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2022, 12, 4993–4997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohinc R, Hoszowska J, Dousse J C; et al. Distribution of aluminum over different T-sites in ferrierite zeolites studied with aluminum valence to core X-ray emission spectroscopy[J]. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics 2017, 19, 29271–29277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinar A B, Verel R, Pariente P P; et al. Direct evidence of the effect of synthesis conditions on aluminum sitting in zeolite ferrierite: A 27Al MQ MAS NMR study[J]. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2014, 193, 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Pinar A B, Hortiguela L G, McCusker L B; et al. Controlling the Aluminum Distribution in the Zeolite Ferrierite via the Organic Structure Directing Agent[J]. Chem. Mater. 2013, 25, 3654–3661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez C M, Pinar A B, García R; et al. Influence of Al distribution and defects concentration of ferrierite catalysts synthesised from na-free gels in the skeletal isomerisation of n-Butene[J]. Top Catal 2009, 52, 1281–1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leshkov Y R, Moliner M, Davis M E. Impact of Controlling the Site Distribution of Al Atoms on Catalytic Properties in Ferrierite-Type Zeolites[J]. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 1096–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu W F, Liu X N, Yang Z Q; et al. Constrained Al sites in FER-type zeolites[J]. Chinese Journal of Catalysis 2021, 42, 2078–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim S, Park G, Woo M H; et al. Control of hierarchical structure and framework-Al distribution of ZSM-5 via adjusting crystallization temperature and their effects on methanol conversion[J]. ACS Catalysis 2019, 9, 2880–2892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabova V, Dedecek J, Cejka. Control of Al distribution in ZSM-5 by conditions of zeolite synthesis[J]. J. Chem. Commun. 2003, 10, 1196–1197. [Google Scholar]

- Nishitoba T, Yoshida N, Kondo J N; et al. Control of Al distribution in the CHA-type aluminosilicate zeolites and its impact on the hydrothermal stability and catalytic properties[J]. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res 2018, 57, 3914–3922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heard C J, Luká G, Nachtigall P. The effect of water on the validity of Lwenstein’s rule[J]. Chemical Science 2019, 10, 5705–5711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iorio J R D, Gounder R. Controlling the isolation and pairing of aluminum in Chabazite zeolites using mixtures of organic and inorganic structure-directing agents[J]. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 2236–2247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iorio J R D, Li S, Jones C B; et al. Cooperative and competitive occlusion of organic and inorganic structure directing agents within Chabazite zeolites influences their aluminum arrangement[J]. Journal of the American Chemical Society 2020, 142, 4807–4819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher R E, Ling S, Slater B. Violations of Löwensteins rule in zeolites[J]. Chem Sci 2017, 8, 7483–7491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inagaki S, Yamada N, Nishii M; et al. Control of framework Al distribution in ZSM-5 zeolite via post-synthetic TiCl4 treatment[J]. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2020, 302, 1102231–1102239. [Google Scholar]

- Vjunov A, Fulton J L, Huthwelker T; et al. Quantitatively Probing the Al Distribution in Zeolites[J]. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 8296–8306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holzinger J, Beato P, Lundegaard, L F; et al. Distribution of Aluminum over the tetrahedral sites in ZSM-5 zeolites and their evolution after steam treatment[J]. The journal of physical chemistry, C, Nanomaterials and interfaces 2018, 122, 15595–15613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng X J, Xiao F S. Green routes for synthesis of zeolites[J]. Chemical Reviews 2014, 114, 1521–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye Z, Zhang H, Zhang Y; et al. Seed-induced synthesis of functional MFI zeolite materials:Method development, crystallization mechanisms, and catalytic properties[J]. Front. Chem. Sci. Eng. 2020, 14, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Zhao Y, Zhang H; et al. Tailoring zeolite ZSM-5 crystal morphology porosity through flexible utilization of Silicalite-1 seeds as templates: Unusual crystallization pathways in a heterogeneous system[J]. Chemistry-A European Journal 2016, 22, 7141–7151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji Y, Wang Y, Xie B; et al. Zeolite Seeds: Third Type of Structure Directing Agents in the Synthesis of Zeolites[J]. Comments on Inorganic Chemistry 2016, 36, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang H, Guo Q, Ren L; et al. Organotemplate-free synthesis of high-silica ferrierite zeolite induced by CDO-structure zeolite building units[J]. Journal of Materials Chemistry 2011, 21, 9494–9497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ham H, Junga H S, Kim H S; et al. Gas-phase carbonylation of dimethyl ether on the stable seed derived Ferrierite[J]. ACS Catal 2020, 10, 5135–5146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kima J, Hama H, Junga H S; et al. Dimethyl ether carbonylation to methyl acetate over highly crystalline zeolite-seed derived Ferrierite[J]. Catalysis Science & Technology 2018, 8, 3060–3072. [Google Scholar]

- Kwak S J, Kim H S, Park N; et al. Recent progress on Al distribution over zeolite frameworks: Linking theories and experiments[J]. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2021, 38, 1117–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo Y X, Wang S, Geng R; et al. Enhancement of the dimethyl ether carbonylation activation via regulating acid sites distribution in FER zeolite framework[J]. iScience 2023, 26, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Xue T, Li S S, Wu H H. Surfactant-promoted synthesis of hierarchical zeolite ferrierite nano-sheets[J]. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials 2021, 312, 1107481–1107488. [Google Scholar]

- Xie S J, Peng J B, Xu L Y; et al. Synthesis of ZSM-35 zeolite using cyclohexylamine as organic template and its catalytic performance[J]. Chinese Journal of Catalysis 2003, 24, 531–534. [Google Scholar]

- Houzvicka J, Nienhuis J G, Ponec V. The role of the acid strength of the catalysts in the skeletal isomerisation of n-Butene[J]. Applied Catalysis A General 1998, 174, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu W Q, Yin Y G, Suib S L; et al. Modification of non-template synthesized ferrierite/ZSM-35 for n-Butene skeletal isomerization to isobutylene[J]. Journal of Catalysis 1996, 163, 232–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raúl, A. Comelli. Skeletal Isomerization of Linear Butenes on Boron Promoted Ferrierite: Effect of the Catalyst Preparation Technique[J]. Catalysis Letters 2008, 122, 302–309. [Google Scholar]

- Emeis C A. Determination of Integrated Molar Extinction Coefficients for Infrared Absorption Bands of Pyridine Adsorbed on Solid Acid Catalysts[J]. Journal of Catalysis 1993, 141, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Sample | Na2O(mg/g) | SARs | Crystallinity(%) | Surface Area (m2/g) | Pore Volume (cm3/g) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Micro | Total | Micro | ||||

| FER-PY | 40 | 25.6 | 100 | 431 | 388 | 0.27 | 0.14 |

| FER-SN | 39 | 25.3 | 101 | 428 | 386 | 0.27 | 0.14 |

| FER-SH | 36 | 24.6 | 99 | 422 | 380 | 0.26 | 0.13 |

| FER-PY+SN | 42 | 25.3 | 100 | 430 | 378 | 0.28 | 0.14 |

| FER-PY+SH | 41 | 24.8 | 101 | 432 | 390 | 0.28 | 0.15 |

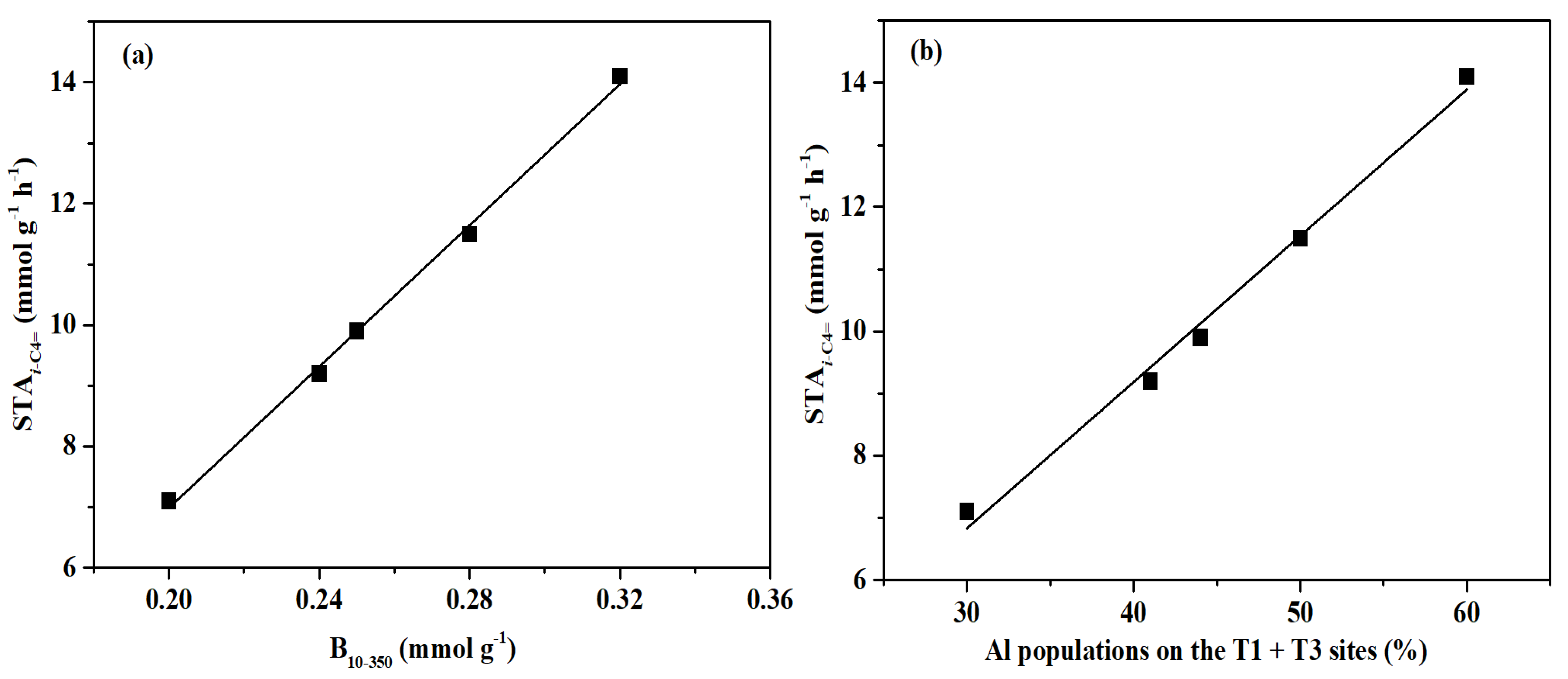

| Sample | Acidity by NH3-TPDa(mmol/g) | Acidity by Py-IRb(mmol/g) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weak | Strong | Total | Brønsted | Lewis | Total | B10-350c | |

| FER-PY | 0.79 | 0.56 | 1.35 | 0.29 | 0.03 | 0.32 | 0.20 |

| FER-SN | 0.78 | 0.55 | 1.33 | 0.28 | 0.03 | 0.31 | 0.24 |

| FER-SH | 0.75 | 0.53 | 1.28 | 0.28 | 0.03 | 0.31 | 0.25 |

| FER-PY+SN | 0.76 | 0.52 | 1.28 | 0.30 | 0.03 | 0.33 | 0.28 |

| FER-PY+SH | 0.81 | 0.56 | 1.37 | 0.34 | 0.02 | 0.35 | 0.32 |

| Sample | Aluminum Distribution (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T1+T3 | |

| FER-PY | 0 | 30 | 30 | 39 | 30 |

| FER-SN | 8 | 19 | 33 | 40 | 41 |

| FER-SH | 10 | 25 | 34 | 31 | 44 |

| FER-PY+SN | 12 | 21 | 38 | 29 | 50 |

| FER-PY+SH | 6 | 15 | 54 | 25 | 60 |

| Composition | wt / % |

|---|---|

| Propane | 0.12 |

| Propylene | 0.15 |

| iso-Butane | 52.86 |

| Butane | 10.94 |

| trans-2-Butene | 13.76 |

| 1-Butene | 12.00 |

| isobutene | 0.26 |

| cis-2-Butene | 9.91 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).