1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance continues to reduce the effectiveness of conventional antibiotics, reviving interest in alternative or adjunctive antimicrobials, including silver in nanoscale form [

1,

2]. Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) exhibit broad-spectrum antibacterial activity and have been explored in wound care, device coatings, and as potentiators of existing antibiotics [

3]. Their nanoscale dimensions confer a high surface-area-to-volume ratio and size-dependent physicochemical properties that can enhance antimicrobial effects relative to bulk silver [

4,

5]. AgNPs provides antibacterial activity through the sustained release of silver ions, which interact with bacterial membranes, and bind to ribosomal subunits or key enzymes to inhibit protein synthesis [

6,

7].

The antibacterial performance of AgNPs is not an inherent property of silver but a function of particle size, morphology, surface chemistry, and colloidal stability [

8,

9]. Parameters such as core size and dispersity (nucleation or growth control), capping environment, and zeta potential affect the nanoparticles approach to adhere and disrupt bacterial envelopes [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. While higher colloidal stability generally preserves dispersion, bioavailability, and shelf life, excessive stabilization can decrease reactivity at the cell-nanoparticle interface [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Thus, identifying formulations that balance stability and reactivity is the key to optimizing bactericidal efficacy [

14,

17].

Chemical reduction remains the most accessible and scalable route to AgNPs [

18]. However, the choice and combination of reductants and stabilizers—such as trisodium citrate, sodium borohydride (NaBH

4), polyethylene glycol (PEG), polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), and oxidants like hydrogen peroxide (H

2O

2)— affect the nucleation rates, growth pathways, particle yield, size distribution, and surface charge [

19,

20]. Literature reports often contradict one another regarding structure–property–activity relationships because synthesis variables are not systematically controlled across methods [

14,

21,

22]. A comparison across different AgNP formulations, physicochemical characterization, and microbiological testing is required to clarify how specific reduction chemistries affect antibacterial outcomes.

To address this gap, AgNPs was synthesized via five different chemical routes—(i) citrate-only reduction, (ii) NaBH

4 reduction, (iii) NaBH

4 with citrate as a secondary reductant, (iv) citrate/NaBH

4 in the presence of H

2O

2, and (v) a PEG/PVP-assisted method—followed by standardized purification and characterization [

23,

24,

25,

26,

27]. Bactericidal performance was evaluated by minimum bactericidal concentration (MBC) assays against methicillin-resistant

Escherichia coli. The antibacterial activity was tested against

Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Klebsiella, Bacillus, and

Staphylococcus, using agar well diffusion method.

The present study is aimed to synthesize silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) using different reducing agents and assess their antimicrobial activity against methicillin-resistant E. coli. The research examines how different sizes and shapes of nanoparticles affect the way they interact with bacterial cells, ultimately aiming to find the most suitable features that would allow nanoparticles to kill bacteria most effectively. The objective of the research is to co-optimize size and stability of chemically synthesized AgNPs using different formulation approaches to achieve reliable antibacterial outcomes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Silver nitrate (AgNO3) was collected from Honeywell Fulka, polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP 40000), Polyethylene glycol, and sodium borohydride from Sigma-Aldrich. In addition, hydrogen peroxide and trisodium citrate was purchased from Roth, whereas ethanol and ammonium hydroxide were purchased from Merck. All chemicals and reagents were used as received without further purification. Water used in all procedures was obtained from a water purification system (Purelab from ELGA) and had a measured resistivity of 18.2 MΩ cm−1.

2.2. Instruments

Experiments were conducted using various instruments like UV–vis double beam spectrophotometer (PG Instrument, UK T60 U), Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) (Model Joel JSM-7600FE, Japan). In addition, Ultra Sonicator (Power-Sonic, Korea), Hotplate Stirrer (Stuart), Micro Centrifuge Machine (Tomy, MX-305), Orbital shaker Incubator (JSR) and Laboratory incubator (Incucell), Particle Size Analyzer (Malvern), Freeze Dryer, TGA (Hitachi instrument - TG/DTA 7200) are also used as per manufacturer’s instructions.

2.3. Experimental Methods

2.3.1. Formula One (F1). AgNP Synthesis Using Trisodium Citrate as a Reducing Agent

150 ml of 7 mM Trisodium Citrate solution was prepared in a beaker at room temperature and placed on a magnetic stirrer. The solution was first brought to boil while being stirred and then 1.5 ml of 0.1 M aqueous silver nitrate was added to start the reaction. The color of the reaction was observed to change slowly from colorless to yellow, then turbid. At last, no more change took place indicating that the reaction was completed [

23].

2.3.2. Formula Two (F2). AgNP Synthesis Using Sodium Borohydride as Reducing Agent

About 30 ml of 2 mM Sodium Borohydride solution was prepared and chilled at 4°C for 20 minutes. The solution was poured into a beaker and placed on a magnetic stirrer. A 2.5 ml solution of 0.01M Silver Nitrate was added dropwise to the beaker while the mixture was continuously stirred. The solution turned pale yellow after only a few drops and brighter yellow after all the solution had been poured, following which stirring was stopped [

24].

2.3.3. Formula Three (F3). AgNP Synthesis by a Combined Method Using Sodium Borohydride as Primary Reductant and Trisodium Citrate as Secondary Reductant

A mixture of 72 mL of distilled water, 2 mL of 0.01M trisodium citrate, and 2 mL of 0.01 M silver nitrate was stirred for 3 minutes at 10°C. Then, 3 mL of 0.002 M sodium borohydride was added to the mixture, and immediately after the addition, stirring was stopped. Following that, the color of the solution turned golden yellow, indicating the formation of nanoparticles [

25].

2.3.4. Formula Four (F4). AgNP Synthesis by a Combined Method Using Trisodium Citrate and Sodium Borohydride as Reducing Agent in the Presence of Hydrogen Peroxide

At first, an aqueous solution combining 0.05 M, 50 μL silver nitrate, 0.075 M, 0.5 mL trisodium citrate, and 30% (v/v) 20 μL H

2O

2, each prepared separately, was stirred vigorously at room temperature to allow homogenous mixing. Then 100 mM, 250 μL sodium borohydride was injected into the solution mixture to initiate the reaction. Initially, the color of the solution was light yellow, which gradually became deep reddish yellow after 3-4 minutes under continuous stirring [

26].

2.3.5. Formula Five (F5). AgNP Synthesis Using Polyethylene Glycol as a Reducing Agent

0.5 g of polyethene glycol (PEG) was completely dissolved in 60 mL of distilled water under magnetic stirring by heating at 120°C. Then, 1.5 g of Polyvinyl pyrrolidine (PVP) and 0.05 g AgNO

3 were added to the solution and stirred for 45 minutes, continuing heating. The solution's color slowly changed from light to brighter yellow, and the stirring was stopped [

27].

2.4. Purification

The previously synthesized silver nanoparticle has been purified using centrifugation at 14000 rpm for 15 minutes. For all methods where sodium borohydride was used as a reducing agent, the nanoparticle formulation was freeze-dried before centrifugation to reduce two-thirds of the volume. After centrifugation, the supernatant was discarded, and the pellet was resuspended in 80 ml ethanol and centrifuged again at 14000 rpm for another 15 minutes. Finally, the pellet was collected.

In the formula where PEG was used as a reducing agent, the pellet obtained after the first centrifugation was suspended in 150 ml acetone and centrifuged at 14000 rpm for 15 minutes. After that, a small amount of orange floating pellet appeared at the bottom of the falcon tube, carefully collected by discarding the supernatant from the top. Then, 20 ml of ethanol was added to the pellet and centrifuged under the same parameters, and the final pellet was collected.

2.5. Chemical Characterization

The optical absorption spectra for nanoparticles in colloidal preparation were recorded using a double beam PG UV-Visible spectrophotometer, UK-T60 U. Rectangular quartz cells of path length 1 cm were used throughout the investigation. The Malvern DLS measurement Instrument measured the size and size distribution of the nanoparticles synthesized in the colloidal solution. The same equipment was used to determine zeta potential (ζ) for a surface charge of Ag nanoparticles. The cuvette used in this experiment was the universal dip cell. The Huckel equation was used to calculate the electrophoretic mobilities of silver nanoparticles.

Morphological analyses of nanoparticles were carried out using the JEOL analytical scanning electron microscope (SEM) model JSM-7600FE. Dried purified AgNP powder was spread on the carbon-coated aluminum stubs for the measurements at an acceleration voltage of 20 kV. TGA was studied by a Hitachi instrument (TG/DTA 7200) in the 20–800°C temperature range under a Nitrogen gas atmosphere at a per-minute heating rate of 10°C.

2.6. Microbiological Characterization of AgNP Formulations

The antimicrobial studies of this research were carried out in the Laboratory of Microbiology of the Department of Mathematics and Natural Sciences of BRAC University. The antibacterial activities of AgNPs synthesized by five different methods were compared through the well diffusion method. The efficiency of the same concentration of silver nitrate was also measured, as silver nitrate was the basis of silver nanoparticle synthesis in all five methods. Apart from that, the Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC) of five nanoparticles was determined against an E. coli isolate.

2.6.1. Collection of Bacterial Strains

Klebsiella spp. was collected from Mohakhali TB Hospital, and a few sample strains of E. coli were collected at Uttara Adhunik Medical College Hospital. Salmonella Typhi, Staphylococcus spp., and Bacillus spp. were also collected from BRAC University Microbiology laboratory. These strains were subcultured in Nutrient Agar Media every week without fail, ensuring their viability and preventing contamination. The freshly cultured colonies were then used in the procedure, providing reliable and consistent results.

2.6.2. Well Diffusion Assay

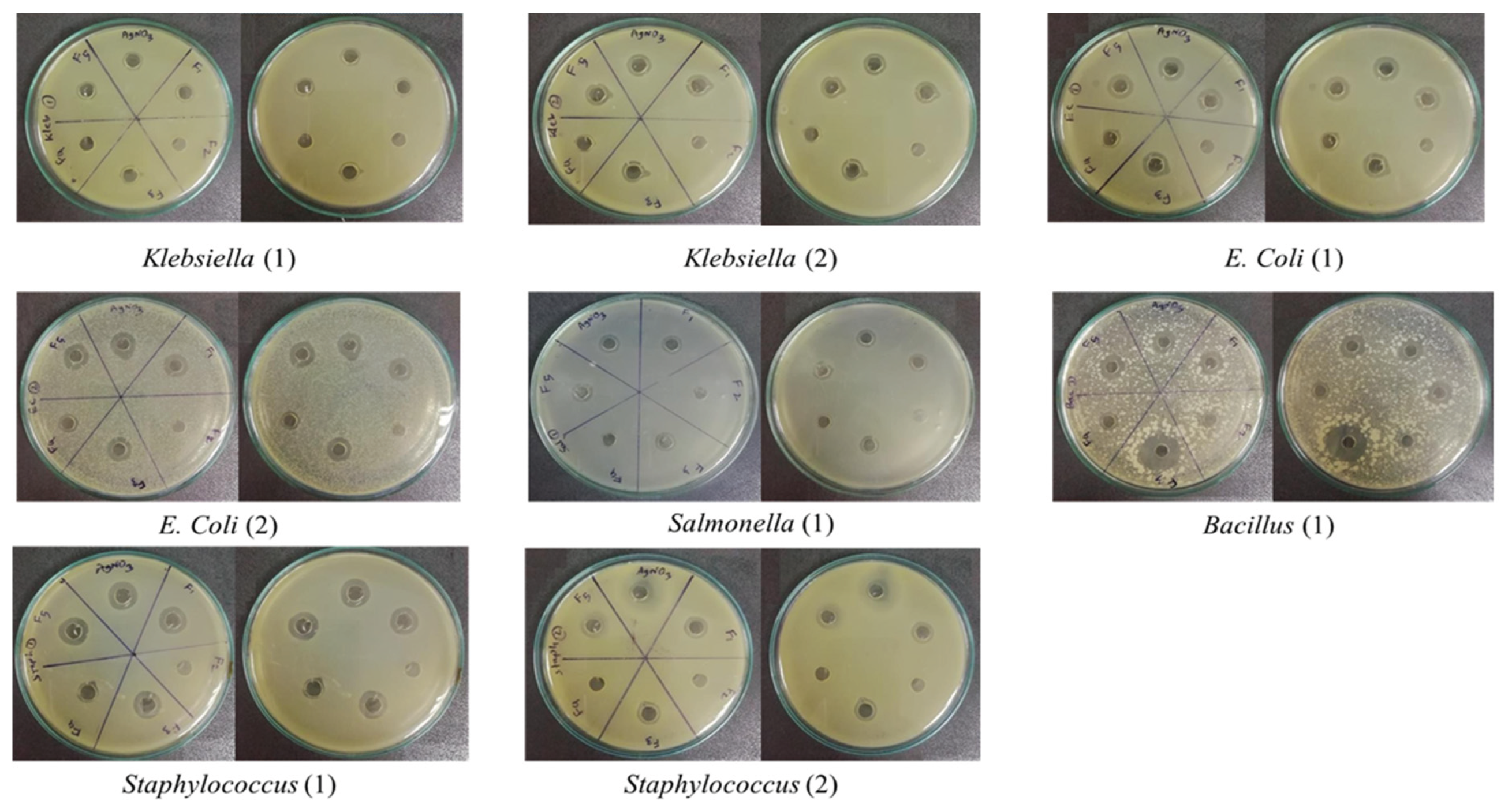

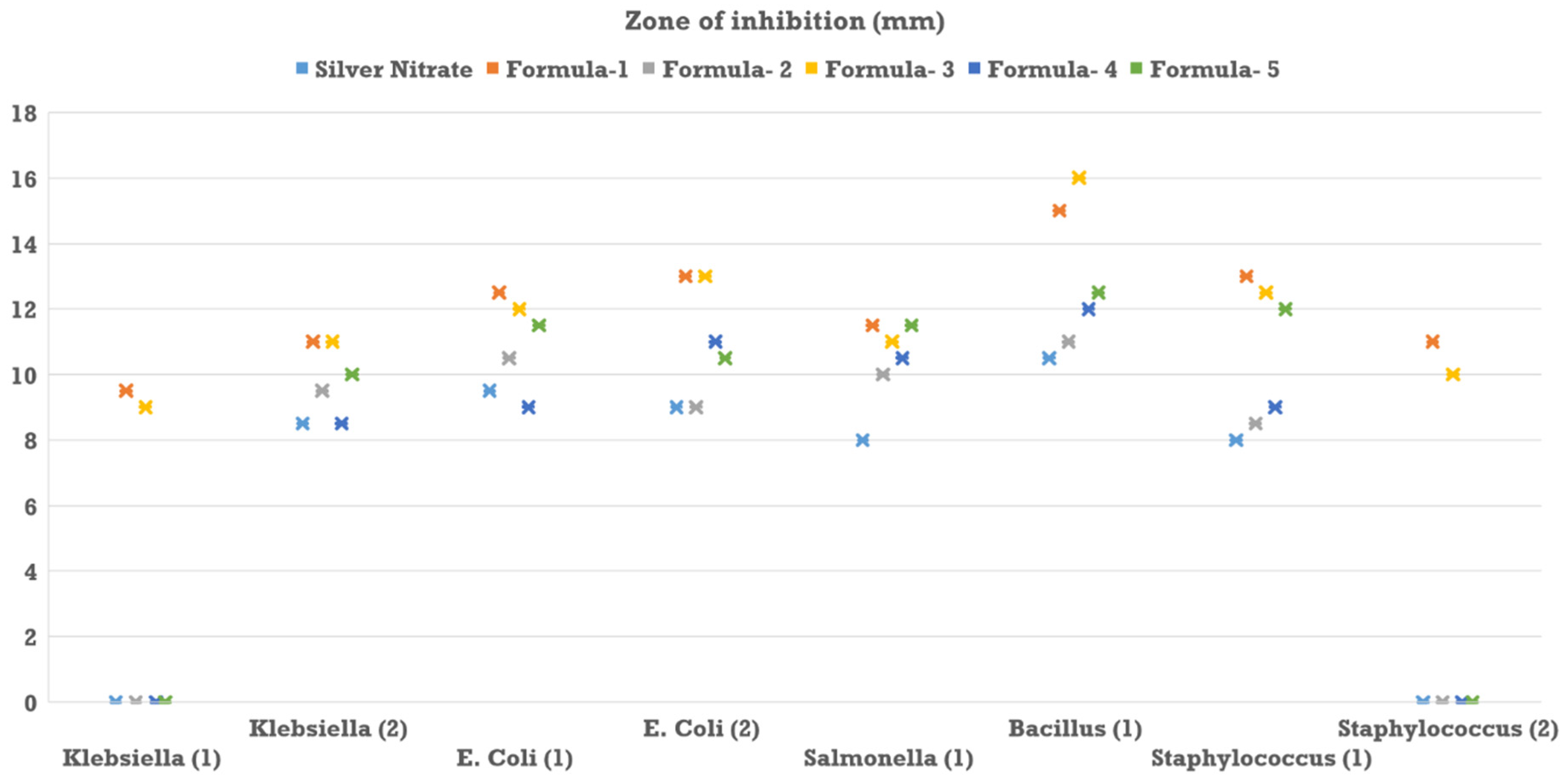

Mueller-Hinton agar was utilized as the culture medium for the agar well diffusion assay. two isolates of Klebsiella species, two isolates of E. coli, one isolate of Bacillus species, one isolate of Salmonella species, and two isolates of Staphylococcus were inoculated onto a separate petri dish. In every dish, six wells were created to assess the antimicrobial activity of five different nanoparticle formulations and a silver nitrate solution, all at the same concentration.

Here, same quantity of silver nitrate was incorporated into each silver nanoparticle synthesis, ensuring that the presumed concentration of silver nanoparticles remained consistent across all samples, assuming complete conversion of silver nitrate to nanoparticles. The nanoparticle concentration for each method was standardized to approximately 80 ppm, and a silver nitrate solution of matching concentration was also prepared. For each well, 40 μl of the respective nanoparticle solution was added, with the final well receiving an equal volume of silver nitrate solution. Following overnight incubation, the zones of inhibition produced by each nanoparticle type and the silver nitrate were measured to evaluate antimicrobial efficacy (

Figure 1).

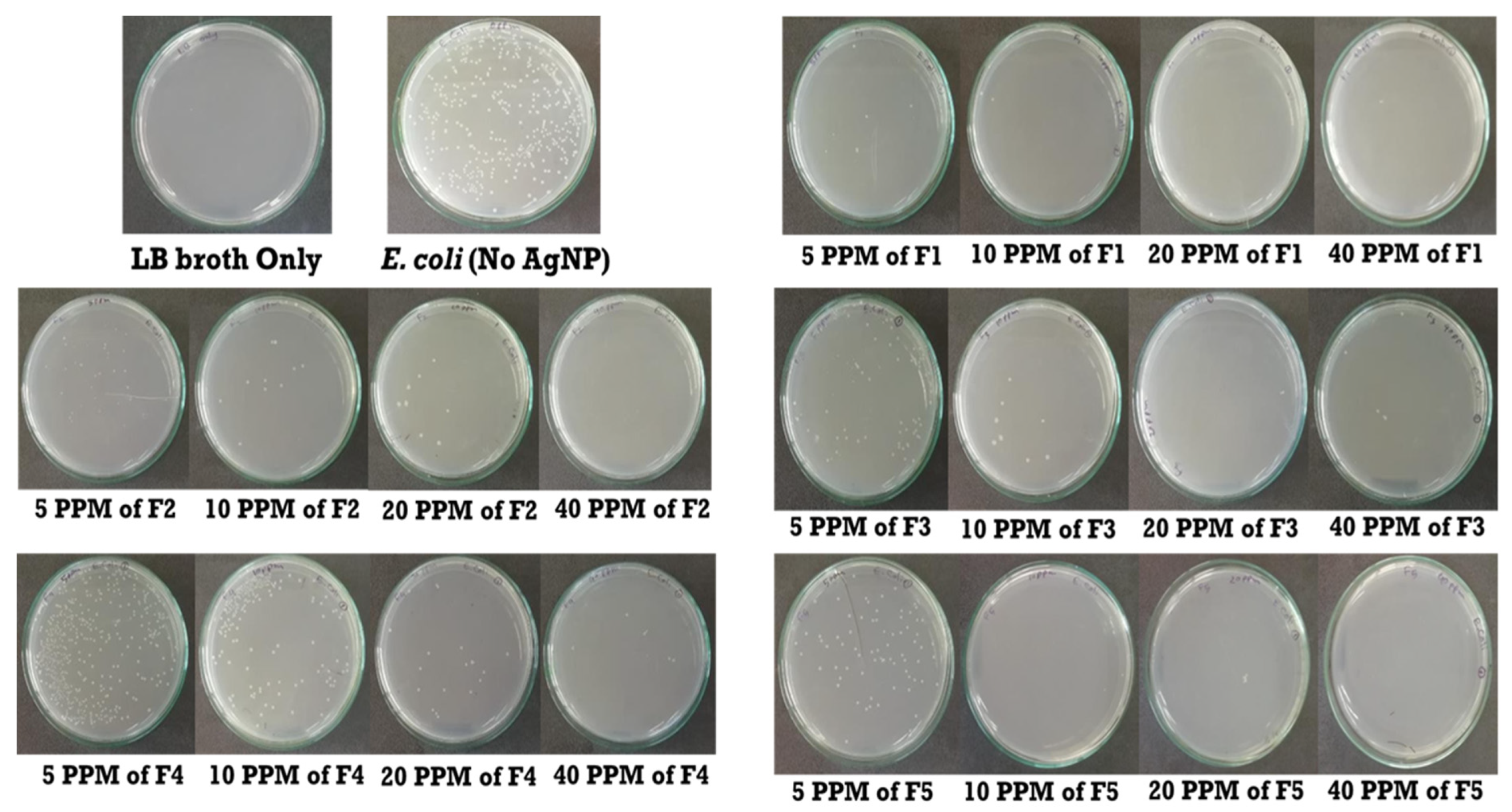

2.6.3. Determination of Minimum Bactericidal Concentration (MBC)

The methicillin-resistant

E. coli culture was grown on Luria Bertani broth till the desired range of Optical Density was reached. 1 ml of culture was diluted ten times before using the organism in a series of test tubes containing different concentrations of AgNPs. For each type of AgNPs formulations, a series of test tubes containing Luria Bertani broth was prepared using the serial dilution method. Five test tubes contained 0 ppm, 5 ppm, 10 ppm, 20 ppm, 40 ppm of AgNPs, and an additional test tube contained only LB broth. 50 μl of the cell from the diluted culture was applied to each test tube except the last one, which contains LB broth only. After 2 hours of incubation, 5 μl from each test tube were spread into separate petri dishes containing nutrient agar. This step was followed by overnight incubation before counting the colonies per petri dish (

Figure 2). The LB broth was cultured to ensure a contamination-free procedure in determining MBC for each type of AgNPs formulation.

3. Results and Discussions

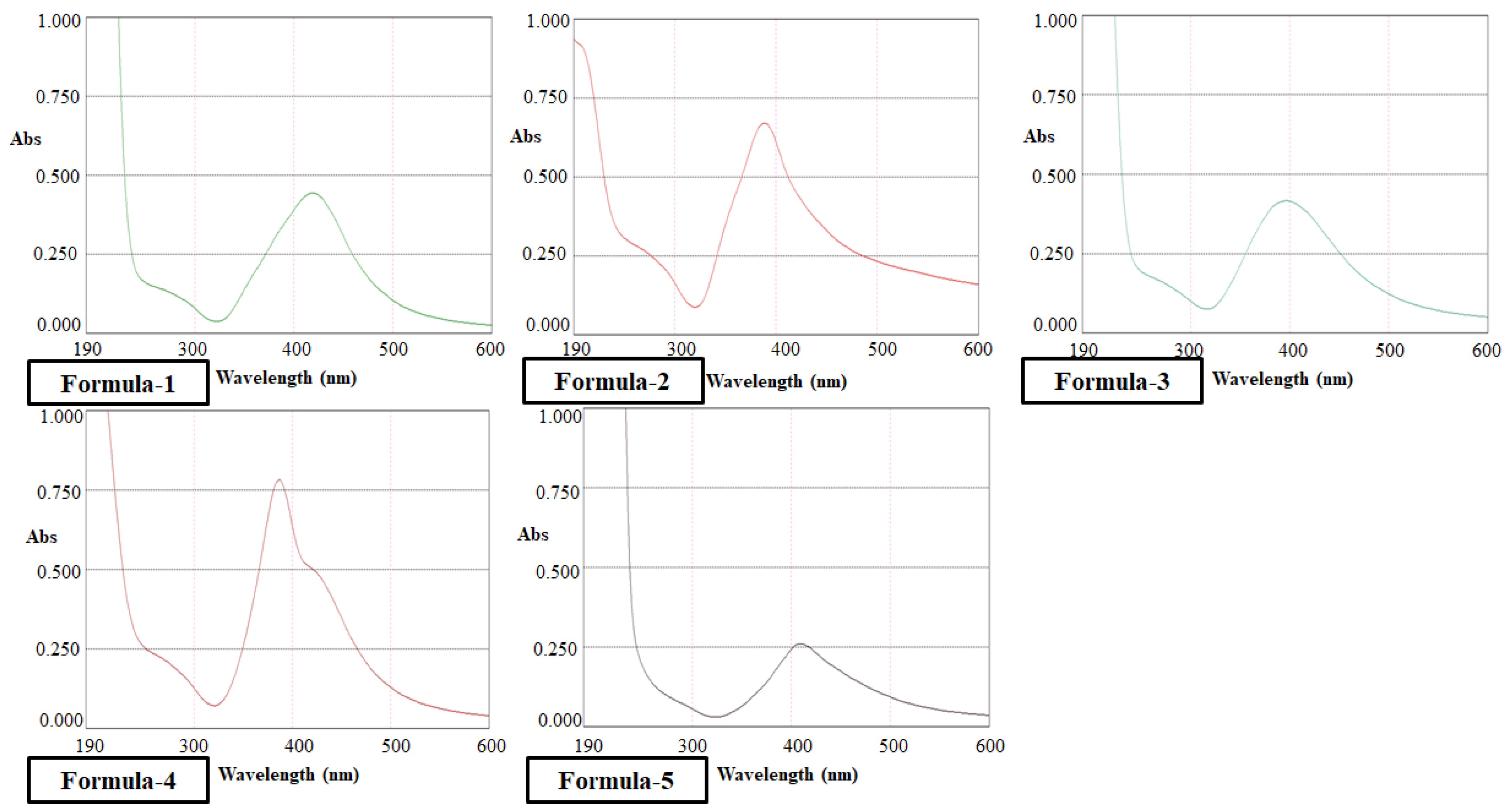

3.1. Quantitative Analysis

Due to surface plasmon resonance, Ag nanoparticle shows a strong absorption peak around 400 nm (

Figure 3). Formulation of AgNPs produced from different methods showed absorption peaks exactly in that region which confirmed nanoparticle formation.

Formulation four due to the presence of H

2O

2 showed the highest absorbance and the second highest absorbance was found for formulation one. This confirmed the highest abundance of nanoparticle formation for these two methods. Analysis for Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) by TDS Meter (

Table 1) also supports the change in AgNPs concentration among different formulations i.e.,

F2 < F5 < F3 < F1 < F4.

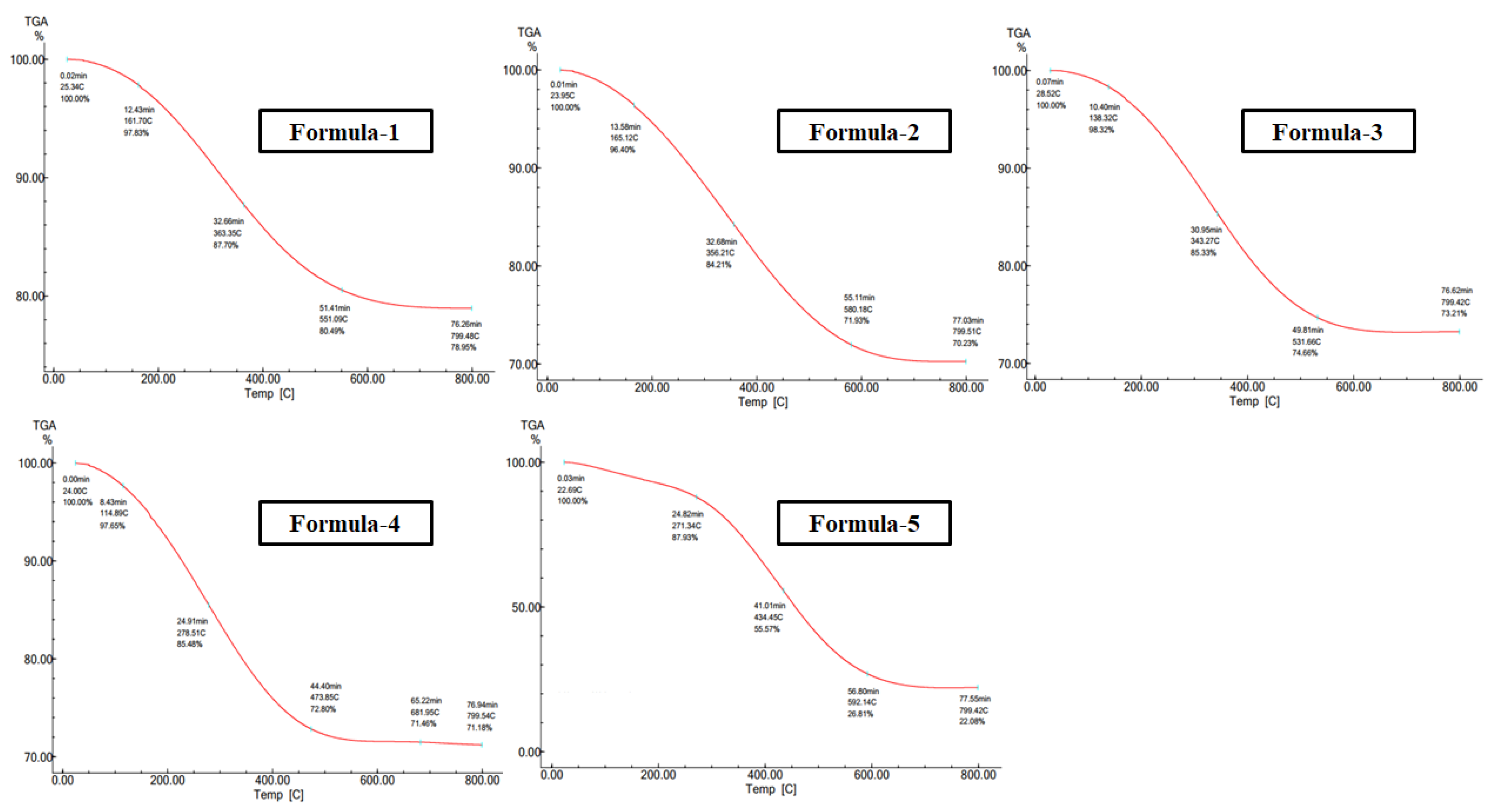

3.2. Thermogravimetric Analysis

TG thermograms of AgNP (

Figure 4) provided information about the percent weight loss of silver nanoparticles upon increasing temperature. To decompose the AgNPs, the samples were heated from 20

∘ C to 800

∘ C; at 270 - 350

∘C the decomposition of the samples starts and its size decreases gradually up to 470 - 590

∘C.

3.3. Morphological Analysis

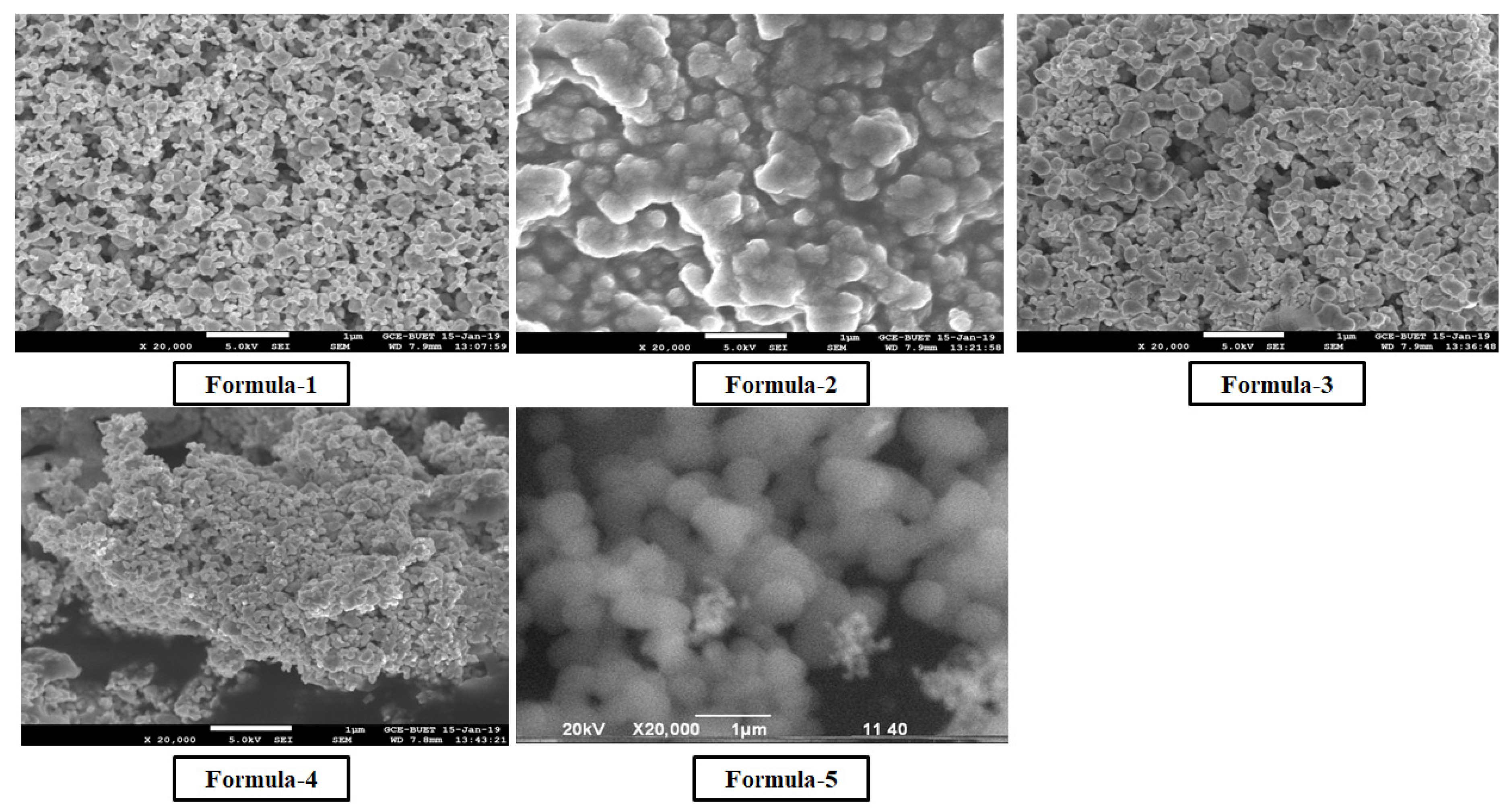

SEM image of nanoparticle (

Figure 5) formed Provides an idea on the size and shape of particle synthesized by five methods, which also supported with the DLS data (

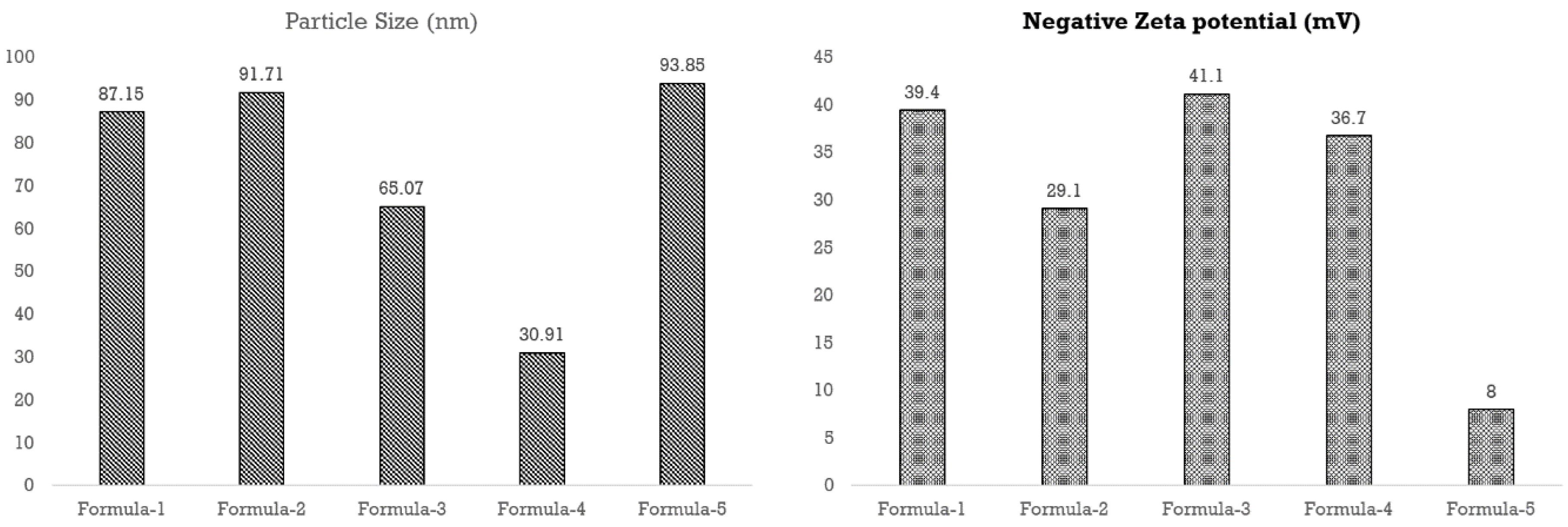

Table 1).

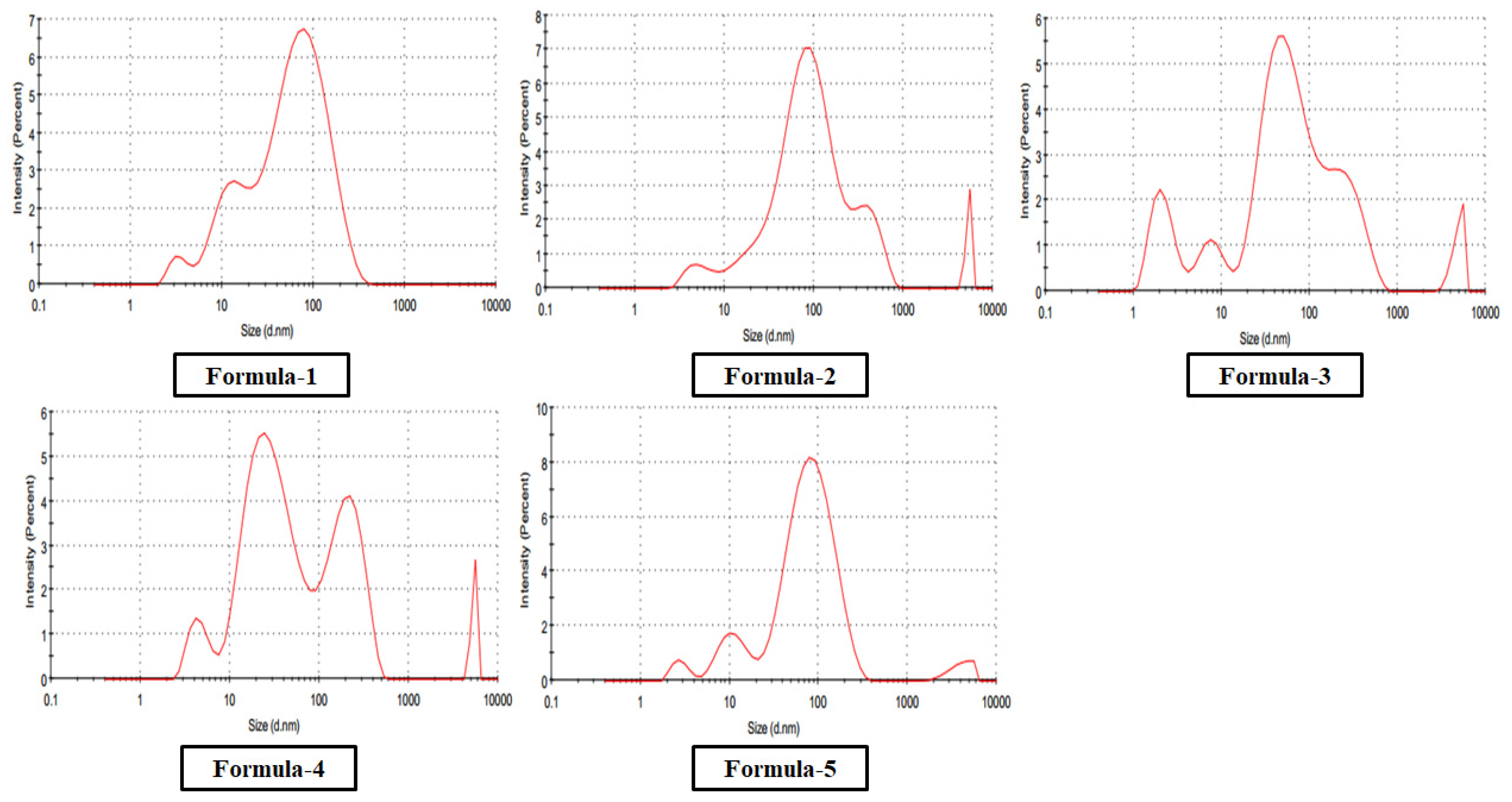

Particle size analysis using DLS (

Figure 6) confirmed nanoparticle formation and conjugation. The size of nanoparticles for all five methods was below or around and 100 nm and the smallest particle was formed for method four. Electrical Conductivity (EC) Analysis (

Table 1) by EC Meter also indicates the change in the mean nanoparticle size and size distribution among different formulations i.e.,

F4 < F3 < F1 < F2 < F5.

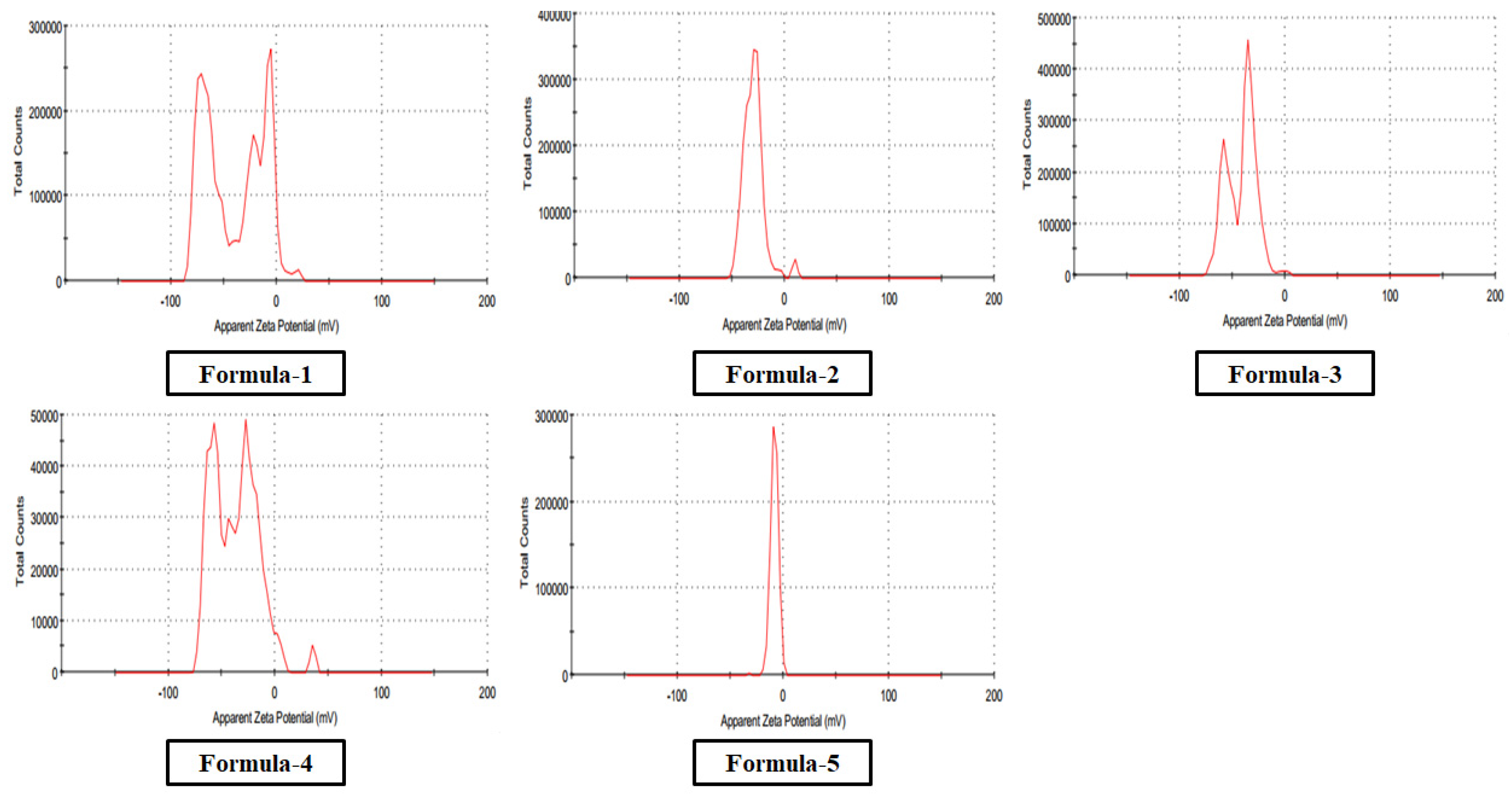

3.4. Stability Analysis

Zeta potentials of the nanoparticle (

Figure 7) formed using the first four methods were below or around -30 mV, which confirms the good stability of the colloidal preparations. Besides, for the fifth method, it was -8 mV, which indicates that this formulation was less stable than others (

Table 1).

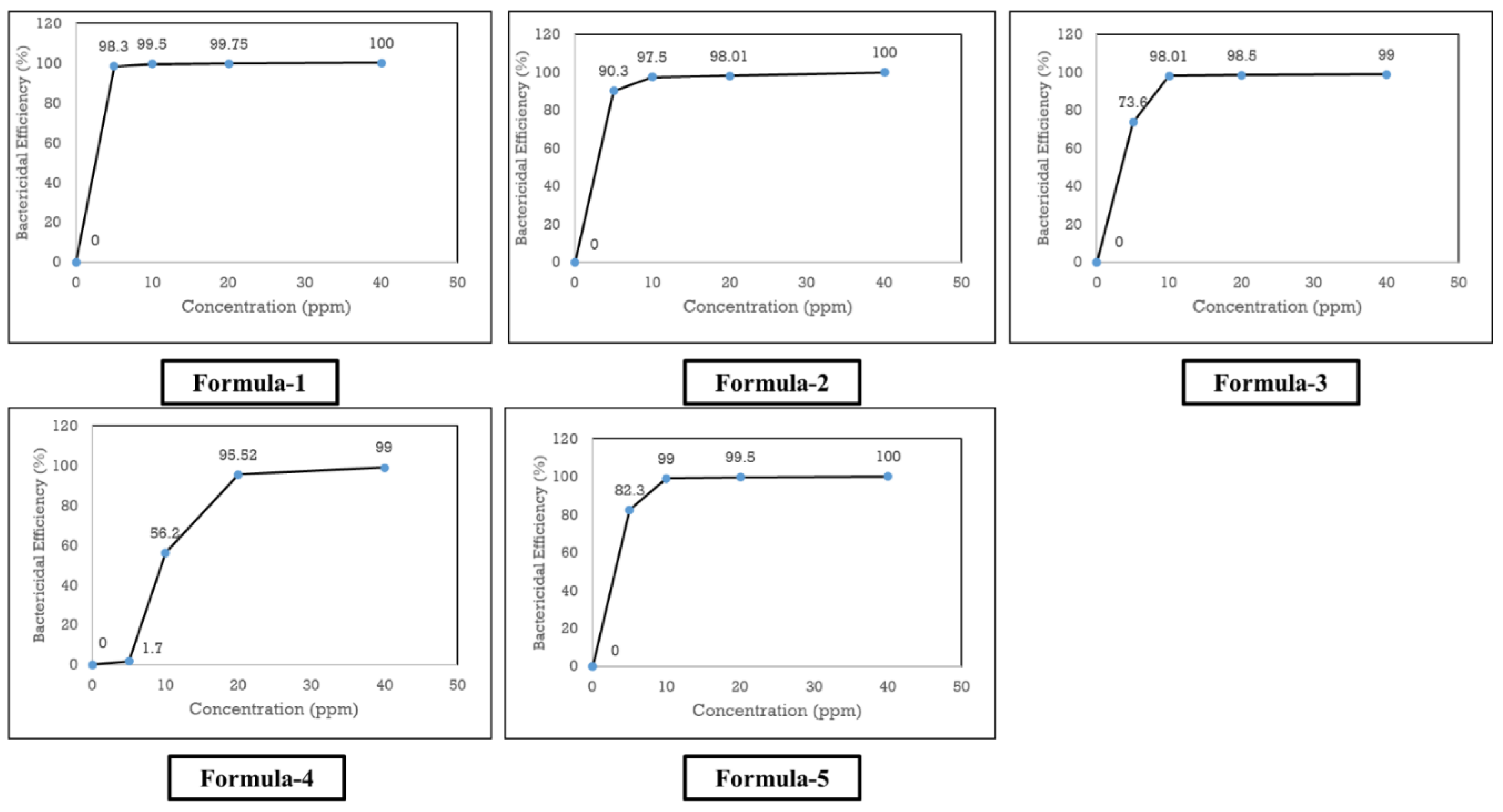

3.5. Bactericidal Efficacy of AgNPs

Before inoculation, the OD of

the E. coli culture was set to 0.440. The numbers of colonies of each petri dish were counted (

Table 2). The petri dish containing only LB broth showed no visible microbial colony growth. Thus, it was ensured that the procedure was contamination-free. Also, 402 colonies were found for 0 ppm concentration of silver nanoparticles, which contained no nanoparticles (

Table 2). The number of colonies for other ppm concentrations was also counted to determine the survival rate of

E. coli. The number of colonies significantly declined even on a lower concentration of silver nitrate (5 ppm) for formula one. Besides, the number of colonies moderately declined at 5 ppm concentration of formulas two, three, and five. Lastly, the number of colonies very slowly declined for formula four (

Table 2).

The survival percentage of

E. coli for AgNPs synthesized by formula one, two, and five were least at the 20 ppm concentration, whereas it declined to zero at 40 ppm concentration (

Table 2). Thus, it can be concluded that 40 ppm or a lower ppm concentration of AgNPs was MBC of formula one, two, and five (

Figure 8). On the other hand, nanoparticles of formula three and four had the lowest survival rate at 40 ppm concentration. Similarly, MBC for formula three and four nanoparticles would be more than 40 ppm concentration (

Figure 8). After analyzing MBC, AgNPs synthesized by formula-one found to be the most effective, followed by formula-five and formula-two respectively. On the contrary, formula-three and formula-four provided least bactericidal efficiency in the case of MBC.

3.6. Antibacterial Activity of AgNPs

Nanoparticle synthesized by formula one was most effective against the second isolate of

E. coli,

Bacillus, and the first isolate of

Staphylococcus species in the well diffusion assay (

Figure 9). It was found to be least efficient against the first isolate of

Klebsiella. It should be mentioned that silver nitrate showed almost the same efficiency as formula one except for

Bacillus isolate (

Figure 9). On the contrary, formula one is least effective against the first isolate of

Klebsiella (

Figure 9). However, nanoparticles synthesized by formula two seemed ineffective against any isolates.

Apart from that, nanoparticles synthesized by formula three were observed to be most effective against the

Bacillus isolate and least effective against the first isolate of

Klebsiella. Besides, nanoparticles of formula four were most effective against

Bacillus and the second isolate of

E. coli and least effective against the first isolate of

Klebsiella and the second isolate of Staphylococcus (

Figure 9). Furthermore, nanoparticles synthesized by formula five were observed to be the most effective against all the clinical strains except

Bacillus.

3.7. Interpretation of Findings

AgNPs synthesized with trisodium citrate were most effective against methicillin-resistant

E. coli due to their optimum particle size and stability (

Figure 10). AgNPs synthesized with PEG and PVP were the least stable; however, their optimal particle size led to significant bactericidal efficacy (

Figure 10). Although AgNPs synthesized with only sodium borohydride demonstrated optimal particle size and moderate stability, their inferior yield value may lead to subsidized antimicrobial efficacy (

Figure 10). In contrast, AgNPs synthesized with a combination of trisodium citrate and sodium borohydride enhanced the yield but reduced the particle size and, subsequently, the antibacterial activity (

Figure 10). Meanwhile, the addition of hydrogen peroxide caused a further decline in particle size and bacteria-killing efficacy while improving the yield (

Figure 10).

The efficiency of silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) in demonstrating antimicrobial behavior is mainly due to their size and shape, which influence their interaction with bacterial cells. However, these properties may vary based on interactions with other components in microbial cells. The stability of AgNPs in relation to their antimicrobial activity depends on morphology, surface variations, and conditions of preparation. In general, higher stability of AgNPs is linked to improved antimicrobial efficiency but too much stability might impair their reactivity and effectiveness. Hence, optimizing those parameters to establish the equilibrium between stability and reactivity holds the key to effectively using them in antimicrobial strategies.

4. Conclusion

The study showed that the choice of reduction chemistry leads to significant, formulation-dependent differences in antibacterial activity, with citrate-reduced AgNPs demonstrating the most effective bactericidal performance against methicillin-resistant E. coli, due to an optimal combination of particle size and stability. These findings underscore the importance of optimizing size and stability to achieve reliable antibacterial outcomes from chemically synthesized AgNPs. Further investigation of the impact of particle size and stability on the antibacterial activity of AgNPs is necessary to optimize the formulation.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the supporting materials.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

AgNPs = Silver nanoparticles, NaBH4 = Sodium borohydride, H2O2 = hydrogen peroxide, PEG = Polyethylene glycol, PVP = Polyvinyl pyrrolidine

References

- Murray, CJL; Ikuta, KS; Sharara, F; Swetschinski, L; Robles Aguilar, G; Gray, A; et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. The Lancet 2022, 399(10325), 629–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Global antibiotic resistance surveillance report 2025 2025 [updated October 13, 2025. 1 December 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240116337/.

- Sondi, I; Salopek-Sondi, B. Silver nanoparticles as antimicrobial agent: a case study on E. coli as a model for Gram-negative bacteria. Journal of colloid and interface science 2004, 275(1), 177–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marambio-Jones, C; Hoek, EMV. A review of the antibacterial effects of silver nanomaterials and potential implications for human health and the environment. Journal of Nanoparticle Research 2010, 12(5), 1531–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morones, JR; Elechiguerra, JL; Camacho, A; Holt, K; Kouri, JB; Ramírez, JT; et al. The bactericidal effect of silver nanoparticles. Nanotechnology 2005, 16(10), 2346–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, S; Poulose, EK. Silver nanoparticles: mechanism of antimicrobial action, synthesis, medical applications, and toxicity effects. International Nano Letters 2012, 2(1), 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, M; Yadav, A; Gade, A. Silver nanoparticles as a new generation of antimicrobials. Biotechnol Adv. 2009, 27(1), 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, S; Tak, YK; Song, JM. Does the antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles depend on the shape of the nanoparticle? A study of the Gram-negative bacterium Escherichia coli. Applied and environmental microbiology 2007, 73(6), 1712–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, M; Dille, J; Godet, S. Synthesis and antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria; nanotechnology, biology, and medicine: Nanomedicine, 2012; Volume 8, 1, pp. 37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Ansari, MA; Khan, HM; Khan, AA; Ahmad, MK; Mahdi, AA; Pal, R; et al. Interaction of silver nanoparticles with Escherichia coli and their cell envelope biomolecules. Journal of basic microbiology 2014, 54(9), 905–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, DE; Dhinojwala, A; Moore, FB-G. Effect of substrate and bacterial zeta potential on adhesion of Mycobacterium smegmatis. Langmuir 2019, 35(21), 7035–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, N; Goshisht, MK. Recent advances and mechanistic insights into antibacterial activity, antibiofilm activity, and cytotoxicity of silver nanoparticles. ACS Applied Bio Materials 2022, 5(4), 1391–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franci, G; Falanga, A; Galdiero, S; Palomba, L; Rai, M; Morelli, G; et al. Silver nanoparticles as potential antibacterial agents. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2015, 20(5), 8856–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pareek, V; Gupta, R; Panwar, J. Do physico-chemical properties of silver nanoparticles decide their interaction with biological media and bactericidal action? A review. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2018, 90, 739–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Ouay, B; Stellacci, F. Antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles: A surface science insight. Nano today 2015, 10(3), 339–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, A; Wei, Y; Syed, F; Tahir, K; Rehman, AU; Khan, A; et al. The effects of bacteria-nanoparticles interface on the antibacterial activity of green synthesized silver nanoparticles. Microbial pathogenesis 2017, 102, 133–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menichetti, A; Mavridi-Printezi, A; Mordini, D; Montalti, M. Effect of Size, Shape and Surface Functionalization on the Antibacterial Activity of Silver Nanoparticles. Journal of Functional Biomaterials 2023, 14(5), 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudikandula, K; Charya Maringanti, S. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles by chemical and biological methods and their antimicrobial properties. Journal of Experimental Nanoscience 2016, 11(9), 714–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo, CV; Villa, CC. Synthesis of silver nanoparticles, influence of capping agents, and dependence on size and shape: A review. Environmental Nanotechnology, Monitoring & Management 2021, 15, 100428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillai, ZS; Kamat, PV. What factors control the size and shape of silver nanoparticles in the citrate ion reduction method? The Journal of Physical Chemistry B 2004, 108(3), 945–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S; Zheng, J. Antibacterial activity of silver nanoparticles: structural effects. Advanced healthcare materials 2018, 7(13), 1701503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samberg, ME; Orndorff, PE; Monteiro-Riviere, NA. Antibacterial efficacy of silver nanoparticles of different sizes, surface conditions and synthesis methods. Nanotoxicology 2011, 5(2), 244–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, X; Ji, X; Wu, H; Zhao, L; Li, J; Yang, W. Shape Control of Silver Nanoparticles by Stepwise Citrate Reduction. The Journal of Physical Chemistry C 2009, 113(16), 6573–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulfinger, L; Solomon, SD; Bahadory, M; Jeyarajasingam, AV; Rutkowsky, SA; Boritz, C. Synthesis and Study of Silver Nanoparticles. Journal of Chemical Education 2007, 84(2), 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, AN; Smith, K; Samuels, TA; Lu, J; Obare, SO; Scott, ME. Nanoparticles functionalized with ampicillin destroy multiple-antibiotic-resistant isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Enterobacter aerogenes and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Applied and environmental microbiology 2012, 78(8), 2768–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q; Li, N; Goebl, J; Lu, Z; Yin, Y. A systematic study of the synthesis of silver nanoplates: is citrate a "magic" reagent? Journal of the American Chemical Society 2011, 133(46), 18931–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, JFA; Saito, A; Bido, AT; Kobarg, J; Stassen, HK; Cardoso, MB. Defeating Bacterial Resistance and Preventing Mammalian Cells Toxicity Through Rational Design of Antibiotic-Functionalized Nanoparticles. Scientific reports 2017, 7(1), 1326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).