Submitted:

10 January 2025

Posted:

13 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Biomass and Activating Agents

2.2. Pyrolysis Experimental Set-Up

2.3. Characterization of Biomass and the Activated Materials

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Char Yield, Proximate Analysis, and Elemental Composition

3.2. SEM Images and Porosity

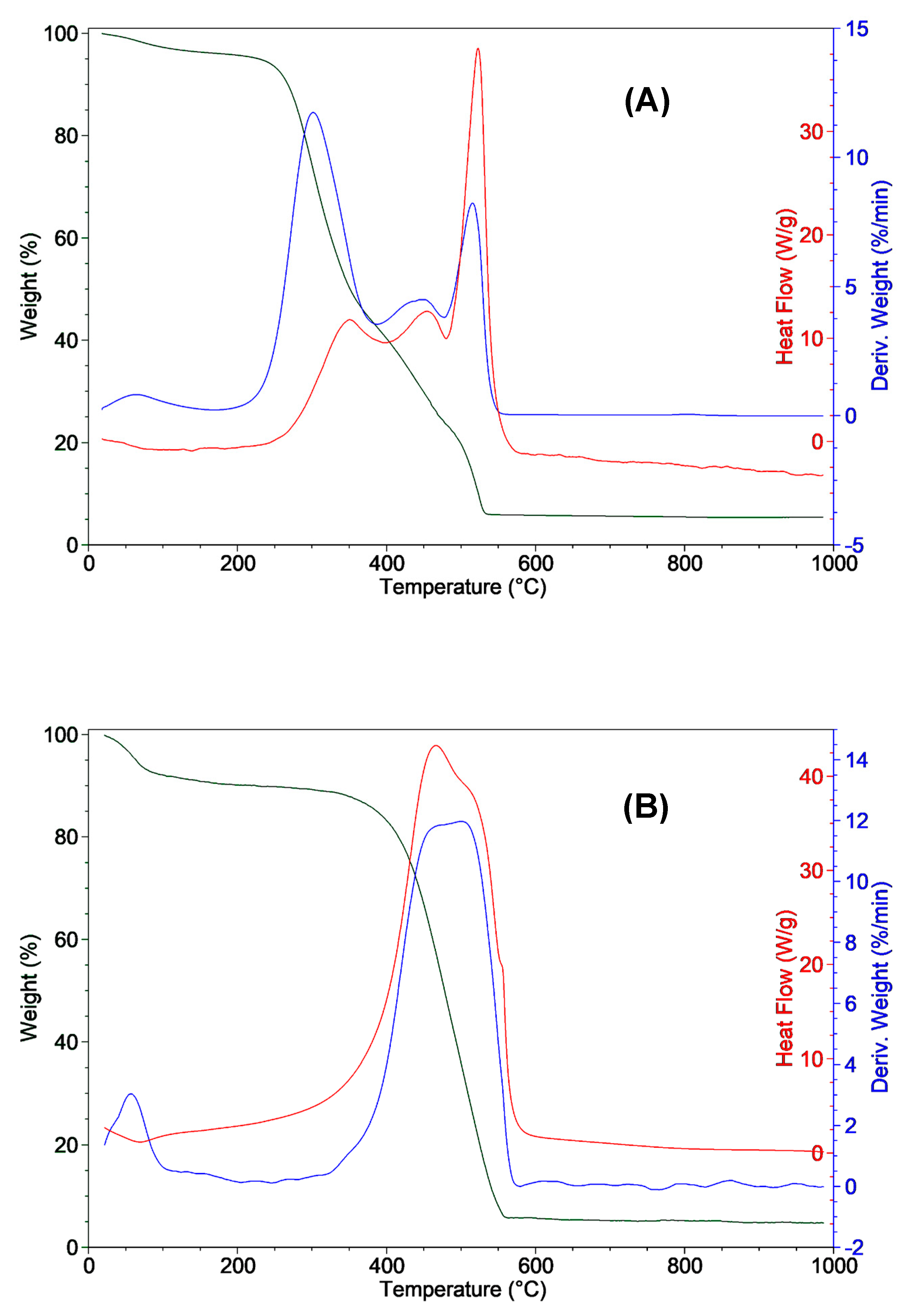

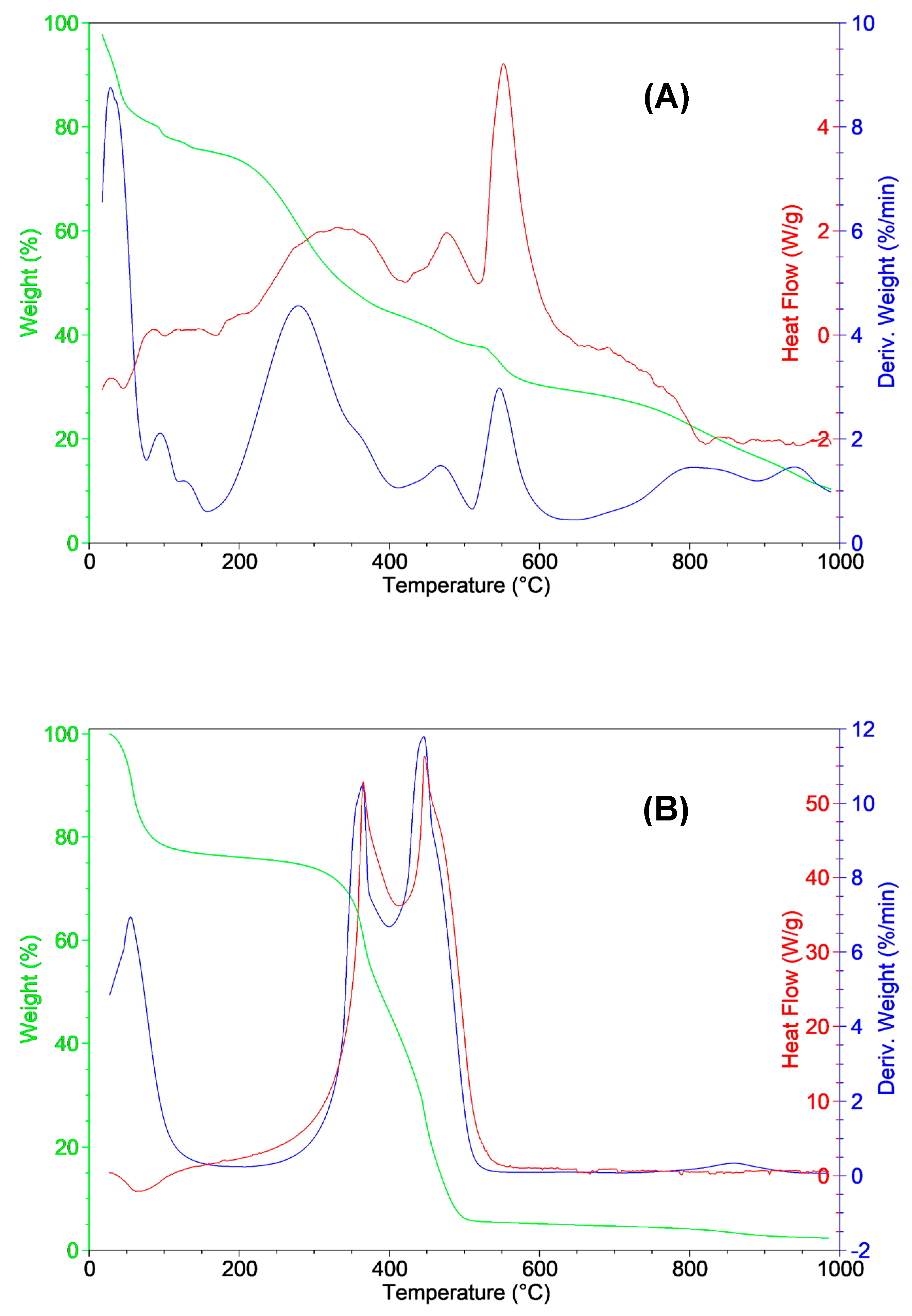

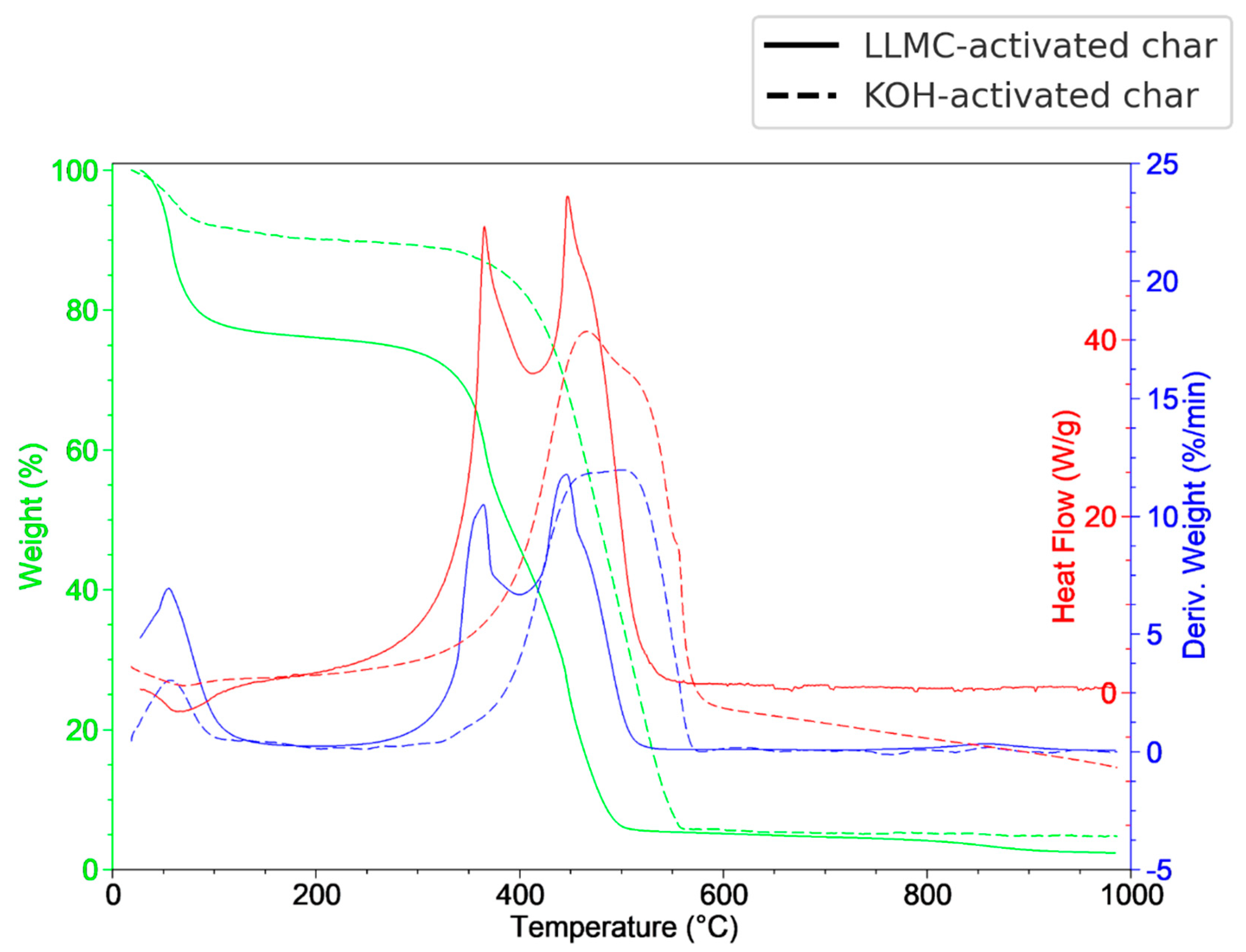

3.3. Thermal Analysis

4. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, W.; Gu, Z.; Ran, G.; Li, Q. Application of membrane separation technology in the treatment of leachate in China: A review. Waste Manag. 2021, 121, 127–140. [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Cui, H.; Li, Y.; Song, X.; Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; Hou, H.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, F.; et al. Challenges and engineering application of landfill leachate concentrate treatment. Environ. Res. 2023, 231, 116028. [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, R.; Porto, R.F.; Quintaes, B.R.; Bila, D.M.; Lavagnolo, M.C.; Campos, J.C. A review on membrane concentrate management from landfill leachate treatment plants: The relevance of resource recovery to close the leachate treatment loop. Waste Manag. Res. J. a Sustain. Circ. Econ. 2023, 41, 264–284. [CrossRef]

- Fang, D.; Wang, J.; Cui, D.; Dong, X.; Tang, C.; Zhang, L.; Yue, D. Recent Advances of Landfill Leachate Treatment. J. Indian Inst. Sci. 2021, 101, 685–724. [CrossRef]

- Keyikoglu, R.; Karatas, O.; Rezania, H.; Kobya, M.; Vatanpour, V.; Khataee, A. A review on treatment of membrane concentrates generated from landfill leachate treatment processes. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2021, 259, 118182. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J.; Li, M.; Dong, X.; Yue, D. Fabricating functionalized carbon nitride using leachate evaporation residue and its adsorptive application. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 341, 126961. [CrossRef]

- Johnson, K.; Liu, Y.; Lu, M. A Review of Recent Advances in Spent Coffee Grounds Upcycle Technologies and Practices. Front. Chem. Eng. 2022, 4, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Wachter, I.; Rantuch, P.; Drienovský, M.; Martinka, J.; Ház, A.; Štefko, T. Determining the Activation Energy of Spent Coffee Grounds By the Thermogravimetric Analysis. J. Chem. Technol. Metall. 2022, 57, 1006–1018.

- Mata, T.M.; Martins, A.A.; Caetano, N.S. Bio-refinery approach for spent coffee grounds valorization. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 247, 1077–1084. [CrossRef]

- Mussatto, S.I.; Machado, E.M.S.; Martins, S.; Teixeira, J.A. Production, Composition, and Application of Coffee and Its Industrial Residues. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2011, 4, 661–672. [CrossRef]

- Saxena, R.; Laddha, H.; Bhoi, R.G. Sustainable management of spent coffee grounds: applications, decompositions techniques and structural analysis. J. Mater. Cycles Waste Manag. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Manyà, J.J.; Azuara, M.; Manso, J.A. Biochar production through slow pyrolysis of different biomass materials: Seeking the best operating conditions. Biomass and Bioenergy 2018, 117, 115–123. [CrossRef]

- Manikandan, S.; Vickram, S.; Subbaiya, R.; Karmegam, N.; Woong Chang, S.; Ravindran, B.; Kumar Awasthi, M. Comprehensive review on recent production trends and applications of biochar for greener environment. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 388, 129725. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Gupta, R.; Zhang, Q.; You, S. Review of biochar production via crop residue pyrolysis: Development and perspectives. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 369, 128423. [CrossRef]

- Conte, P.; Bertani, R.; Sgarbossa, P.; Bambina, P.; Schmidt, H.-P.; Raga, R.; Lo Papa, G.; Chillura Martino, D.F.; Lo Meo, P. Recent Developments in Understanding Biochar’s Physical–Chemistry. Agronomy 2021, 11, 615. [CrossRef]

- Manyà, J.J. Pyrolysis for Biochar Purposes: A Review to Establish Current Knowledge Gaps and Research Needs. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 7939–7954. [CrossRef]

- Bertero, M.; Sedran, U. Coprocessing of Bio-oil in Fluid Catalytic Cracking. In Recent Advances in Thermo-Chemical Conversion of Biomass; Elsevier, 2015; pp. 355–381 ISBN 9780444632906.

- Qian, K.; Tian, W.; Li, W.; Wu, S.; Chen, D.; Feng, Y. Catalytic Pyrolysis of Waste Plastics over Industrial Organic Solid-Waste-Derived Activated Carbon: Impacts of Activation Agents. Processes 2022, 10, 2668. [CrossRef]

- Gurav, R.; Mandal, S.; Smith, L.M.; Shi, S.Q.; Hwang, S. The potential of self-activated carbon for adsorptive removal of toxic phenoxyacetic acid herbicide from water. Chemosphere 2023, 339, 139715. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, M.; Chen, M.; Min, F.; Zhang, S.; Ren, Z.; Yan, Y. Catalytic effects of six inorganic compounds on pyrolysis of three kinds of biomass. Thermochim. Acta 2006, 444, 110–114. [CrossRef]

- Rosson, E.; Garbo, F.; Marangoni, G.; Bertani, R.; Lavagnolo, M.C.; Moretti, E.; Talon, A.; Mozzon, M.; Sgarbossa, P. Activated Carbon from Spent Coffee Grounds: A Good Competitor of Commercial Carbons for Water Decontamination. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5598. [CrossRef]

- Wongmat, Y.; Wagner, D.R. Effect of Potassium Salts on Biochar Pyrolysis. Energies 2022, 15, 5779. [CrossRef]

- Safar, M.; Lin, B.-J.; Chen, W.-H.; Langauer, D.; Chang, J.-S.; Raclavska, H.; Pétrissans, A.; Rousset, P.; Pétrissans, M. Catalytic effects of potassium on biomass pyrolysis, combustion and torrefaction. Appl. Energy 2019, 235, 346–355. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Lemaire, R.; Bensakhria, A.; Luart, D. Review on the catalytic effects of alkali and alkaline earth metals (AAEMs) including sodium, potassium, calcium and magnesium on the pyrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass and on the co-pyrolysis of coal with biomass. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2022, 163, 105479. [CrossRef]

- Prado, L.L.; Melo, V.F.; Braga, M.C.; Motta, A.C. V.; Araújo, E.M. Pyrolyzed sewage sludge used in the decontamination of landfill leachate: ammonium adsorption. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 20, 9129–9142. [CrossRef]

- Celso Monteiro Zanona, V.R.; Rodrigues Barquilha, C.E.; Borba Braga, M.C. Removal of recalcitrant organic matter of landfill leachate by adsorption onto biochar from sewage sludge: A quali-quantitative analysis. J. Environ. Manage. 2023, 344, 118387. [CrossRef]

- Nav, T.Z.; Pümpel, T.; Bosch, D.; Bockreis, A. Insight into the application of biochars produced from wood residues for removing different fractions of dissolved organic material (DOM) from bio-treated wastewater. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2023, 32, 103271. [CrossRef]

- Yek, P.N.Y.; Li, C.; Peng, W.; Wong, C.S.; Liew, R.K.; Wan Mahari, W.A.; Sonne, C.; Lam, S.S. Production of modified biochar to treat landfill leachate using integrated microwave pyrolytic CO2 activation. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 425, 131886. [CrossRef]

- Igwegbe, C.A.; Kozłowski, M.; Wąsowicz, J.; Pęczek, E.; Białowiec, A. Nitrogen Removal from Landfill Leachate Using Biochar Derived from Wheat Straw. Materials (Basel). 2024, 17, 928. [CrossRef]

- Ben Hassen-Trabelsi, A.; Kallel, A.; Ben Amor, E.; Cherbib, A.; Naoui, S.; Trabelsi, I. Up-Grading Biofuel Production by Co-pyrolysis of Landfill Leachate Concentrate and Sewage Sludge Mixture. Waste and Biomass Valorization 2020, 11, 291–301. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, L.; Liu, P.; Zhou, Z.; Huhetaoli; Wu, Y.; Lei, T. Characteristics and adsorption of Cr(VI) of biochar pyrolyzed from landfill leachate sludge. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2022, 162, 105449. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Yue, Q.; Gao, B.; Li, A. Insight into activated carbon from different kinds of chemical activating agents: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 746, 141094. [CrossRef]

- de Almeida, R.; Lanero, F.; Lavagnolo, M.C.; Sgarbossa, P.; Bertani, R.; Vianna, M.M.; Campos, J.C. Thermal Characterization of Biochars Produced in Slow Co-Pyrolysis of Spent Coffee Ground and Concentrated Landfill Leachate Residue. In Proceedings of the ECP 2023; MDPI: Basel Switzerland, 2023; p. 12. [CrossRef]

- Grossule, V.; Fang, D.; Yue, D.; Lavagnolo, M.C.; Raga, R. Preparation of artificial MSW leachate for treatment studies: Testing on black soldier fly larvae process. Waste Manag. Res. J. a Sustain. Circ. Econ. 2022, 0734242X2110667. [CrossRef]

- Almeida, R. De Landfill Leachate Treatment by Membrane-based Technologies: Cost-benefit Analysis, Membrane Concentrate Management, and Perspectives, Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, 2022.

- ASTM Standard Test Method for Chemical Analysis of Wood Charcoal 2021, 2. [CrossRef]

- Bardestani, R.; Patience, G.S. Experimental methods in chemical engineering : specific surface area and pore size distribution measurements — BET ,. 2019, 2781–2791. [CrossRef]

- Rijo, B.; Soares Dias, A.P.; de Jesus, N.; Pereira, M.F. Home Trash Biomass Valorization by Catalytic Pyrolysis. Environments 2023, 10, 186. [CrossRef]

- Montane, D.; Torné-Fernández, V.; Fierro, V. Activated carbons from lignin: kinetic modeling of the pyrolysis of Kraft lignin activated with phosphoric acid. Chem. Eng. J. 2005, 106, 1–12. [CrossRef]

- Illingworth, J.M.; Rand, B.; Williams, P.T. Understanding the mechanism of two-step, pyrolysis-alkali chemical activation of fibrous biomass for the production of activated carbon fibre matting. Fuel Process. Technol. 2022, 235, 107348. [CrossRef]

- Tibola, F.; de Oliveira, T.; Cerqueira, D.; Ataíde, C.; Cardoso, C. Kinetic parameters study for the slow pyrolysis of coffee residues based on thermogravimetric analysis. Quim. Nova 2020, 43, 426–434. [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-W.; Li, Y.-H.; Xiao, K.-L.; Lasek, J. Cofiring characteristics of coal blended with torrefied Miscanthus biochar optimized with three Taguchi indexes. Energy 2019, 172, 566–579. [CrossRef]

- Heidarinejad, Z.; Dehghani, M.H.; Heidari, M.; Javedan, G.; Ali, I.; Sillanpää, M. Methods for preparation and activation of activated carbon: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 18, 393–415. [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros, L.F.; Teixeira, J.A.; Mussatto, S.I. Chemical, Functional, and Structural Properties of Spent Coffee Grounds and Coffee Silverskin. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2014, 7, 3493–3503. [CrossRef]

- Alcaraz, L.; Escudero, M.E.; Alguacil, F.J.; Llorente, I.; Urbieta, A.; Fernández, P.; López, F.A. Dysprosium Removal from Water Using Active Carbons Obtained from Spent Coffee Ground. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 1372. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Fu, X.; Zou, Y.; Li, Q.; Luo, Z. Integrated natural deep eutectic solvent and pulse-ultrasonication for efficient extraction of crocins from gardenia fruits (Gardenia jasminoides Ellis) and its bioactivities. Food Chem. 2022, 380, 132216. [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Guo, S.; Xu, Y.; Ettoumi, F.; Fang, J.; Yan, X.; Xie, Z.; Luo, Z.; Cheng, K. Valorization and protection of anthocyanins from strawberries (Fragaria×ananassa Duch.) by acidified natural deep eutectic solvent based on intermolecular interaction. Food Chem. 2024, 447, 138971. [CrossRef]

- Bhat, S.; Uthappa, U.T.; Sadhasivam, T.; Altalhi, T.; Soo Han, S.; Kurkuri, M.D. Abundant cilantro derived high surface area activated carbon (AC) for superior adsorption performances of cationic/anionic dyes and supercapacitor application. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 459, 141577. [CrossRef]

- Thue, P.S.; Ramos, D.; Lima, E.C.; Teixeira, R.A.; Glaydson, S.; Dias, S.L.P.; Machado, F.M. Comparative studies of physicochemical and adsorptive properties of biochar materials from biomass using different zinc salts as activating agents. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107632. [CrossRef]

- Rouquerol, J.; Avnir, D.; Fairbridge, C.W.; Everett, D.H.; Haynes, J.H.; Pernicone, N.; Ramsay, J.D.F.; Sing, K.S.W.; Unger, K.K. Recommendations for the characterization of porous solids (Technical Report); 1994; Vol. 66;.

- Bejenari, V.; Marcu, A.; Ipate, A.-M.; Rusu, D.; Tudorachi, N.; Anghel, I.; Şofran, I.-E.; Lisa, G. Physicochemical characterization and energy recovery of spent coffee grounds. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 15, 4437–4451. [CrossRef]

- Cárdenas-Aguiar, E.; Gascó, G.; Paz-Ferreiro, J.; Méndez, A. Thermogravimetric analysis and carbon stability of chars produced from slow pyrolysis and hydrothermal carbonization of manure waste. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2019, 140, 434–443. [CrossRef]

- Protásio, T. de P.; Melo, I.C.N.A. de; Guimarães Junior, M.; Mendes, R.F.; Trugilho, P.F. Thermal decomposition of torrefied and carbonized briquettes of residues from coffee grain processing. Ciência e Agrotecnologia 2013, 37, 221–228. [CrossRef]

- Amalina, F.; Razak, A.S.A.; Krishnan, S.; Sulaiman, H.; Zularisam, A.W.; Nasrullah, M. Biochar production techniques utilizing biomass waste-derived materials and environmental applications – A review. J. Hazard. Mater. Adv. 2022, 7, 100134. [CrossRef]

- Leng, L.; Huang, H. An overview of the effect of pyrolysis process parameters on biochar stability. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 270, 627–642. [CrossRef]

- Haynes, W.M. CRC Handbook of Chemistry and Physics; Haynes, W.M., Ed.; CRC Press, 2014; ISBN 9780429170195.

- Ben Abdallah, A.; Ben Hassen Trabelsi, A.; Navarro, M.V.; Veses, A.; García, T.; Mihoubi, D. Pyrolysis of tea and coffee wastes: effect of physicochemical properties on kinetic and thermodynamic characteristics. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2023, 148, 2501–2515. [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Yao, X.; Li, H.; Liu, Z.; Ma, W.; Liang, X. Thermal Stability of Oxygen-Containing Functional Groups on Activated Carbon Surfaces in a Thermal Oxidative Environment. J. Chem. Eng. JAPAN 2014, 47, 21–27. [CrossRef]

- El-Hendawy, A.N.A.; Alexander, A.J.; Andrews, R.J.; Forrest, G. Effects of activation schemes on porous, surface and thermal properties of activated carbons prepared from cotton stalks. J. Anal. Appl. Pyrolysis 2008, 82, 272–278. [CrossRef]

- Plavniece, A.; Dobele, G.; Volperts, A.; Zhurinsh, A. Hydrothermal Carbonization vs. Pyrolysis: Effect on the Porosity of the Activated Carbon Materials. Sustain. 2022, 14. [CrossRef]

- ISO 17225-1 International Standard for Solid biofuels — Fuel specifications and classes. 2021, 2021.

| Proximate analysis (wt%) | *Ultimate analysis (dry basis, wt%) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MC | VM | Ashes | FC | C | O | Na | K | Mg | Cl | S | |

| LLMC residue | 2.46 | 23.55 | 51.23 | 22.76 | 13.32±2.23 | 33.99±4.33 | 39.28±1.99 | 8.085±0.78 | 0.256±0.08 | 3.83±0.66 | 0.745±0.435 |

| SCG | Biochar | KOH-activated char | LLMC-activated char | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mass yield (wt%) | ─ | 23.9 | 21.2 | 18.6 |

| MC (wt%) | 3.78 | 9.2 | 5.8 | 23.3 |

| VM (wt%) | 94.91 | 58.4 | 47.9 | 44.4 |

| Ashes (wt%) | 1.26 | 5.8 | 1.3 | 7.0 |

| FC (wt%) | 1.25 | 33.0 | 25.6 | 20.4 |

| Material | Elemental composition (dry basis, wt%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | O | Na | K | Mg | Ca | Al | Cl | S | |

| SCG | 47.73 | 47.49 | n.d | 3.19 | n.d | 0.91 | n.d | n.d | 0.68 |

| LLMC residue | 14.55 | 37.04 | 40.86 | 2.26 | n.d | n.d | 0.78 | 2.63 | 1.55 |

| SCG char | 46.06 | 45.26 | n.d | 3.87 | 0.40 | n.d | n.d | n.d | 0.52 |

| KOH-activated char | 85.30 | 13.70 | n.d | 0.87 | 0.02 | n.d | n.d | n.d | 0.10 |

| LLMC-activated char | 63.97 | 20.16 | 4.32 | 4.14 | 1.00 | 2.87 | n.d | 0.47 | 1.43 |

| Sample | BET surface area (m² g-1) | Average pore size (nm) |

|---|---|---|

| SCG | 4.5 | 10.7 |

| SCG char | 463 | 4.8 |

| KOH-activated char | 1960 | 1.8 |

| LLMC-activated char | 1138 | 5.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).