Submitted:

03 January 2024

Posted:

16 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

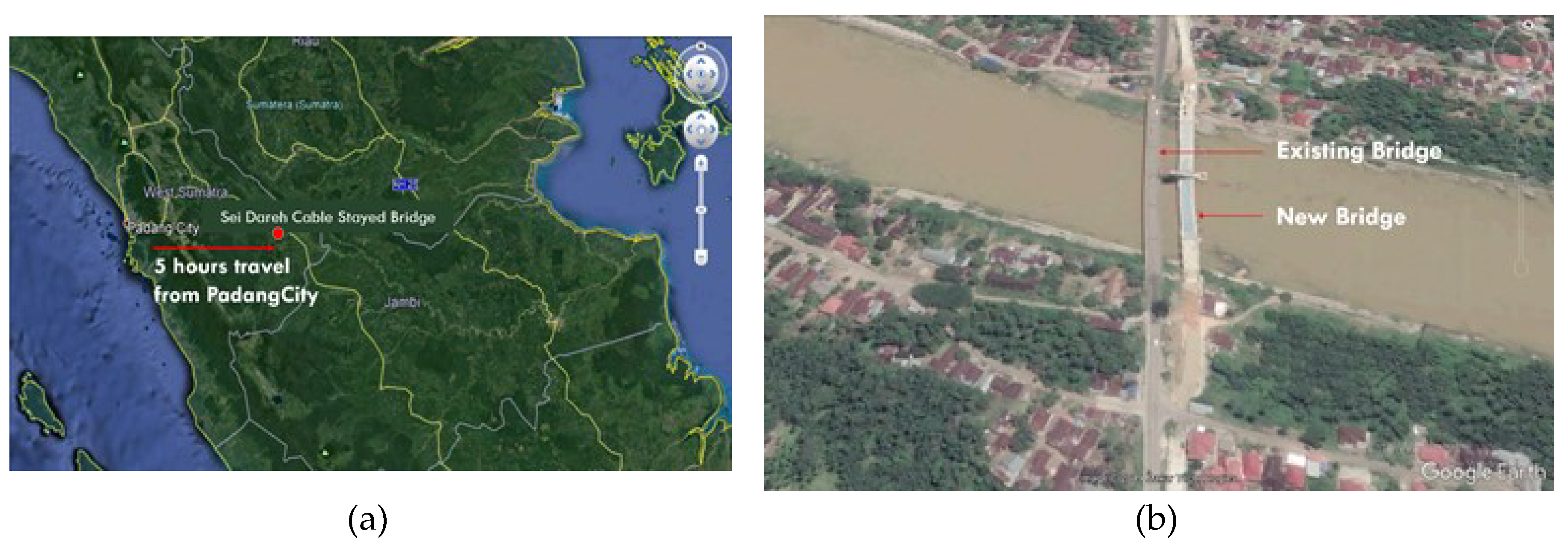

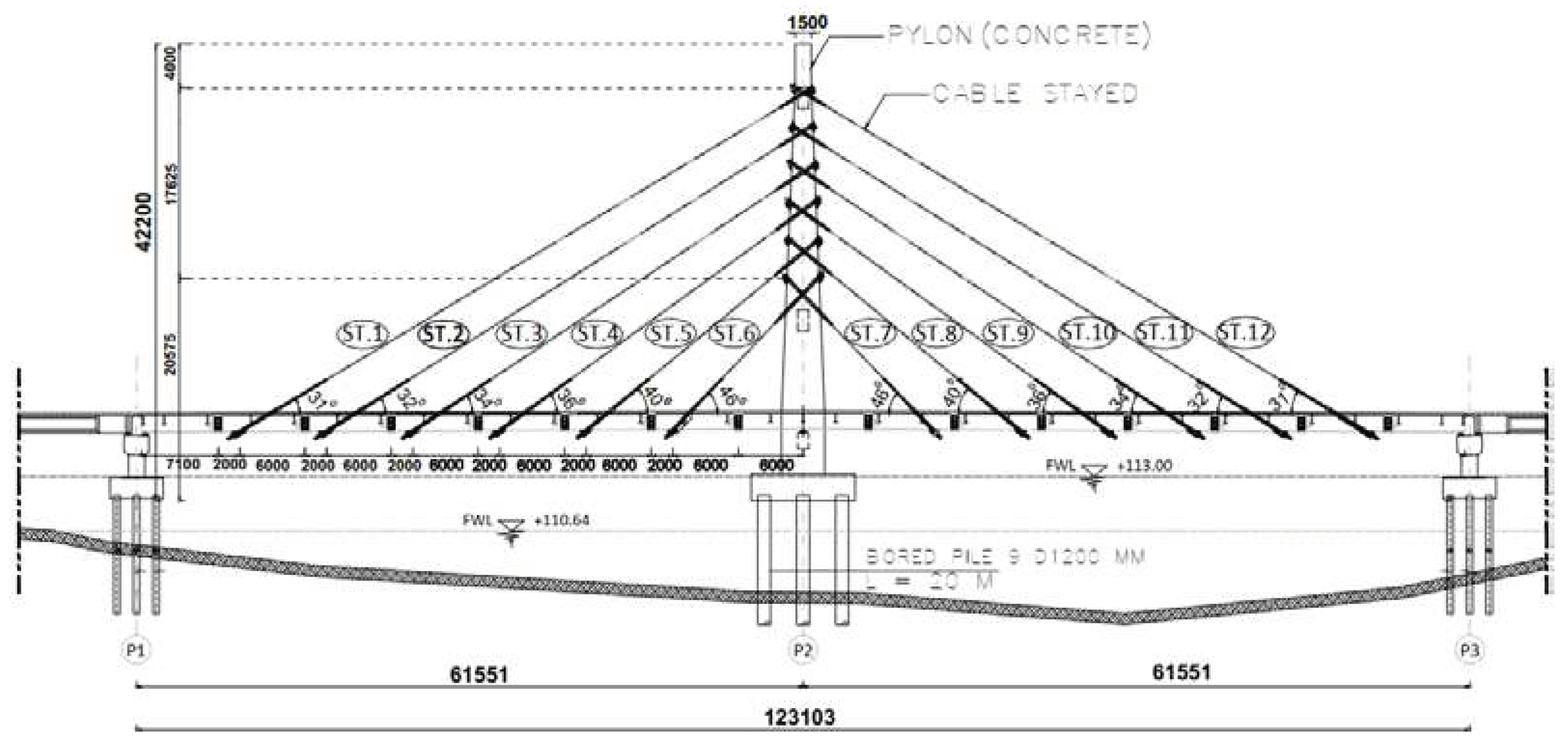

2. The Sei Dareh Cable Stayed Bridge

2.1. Tested Bridge

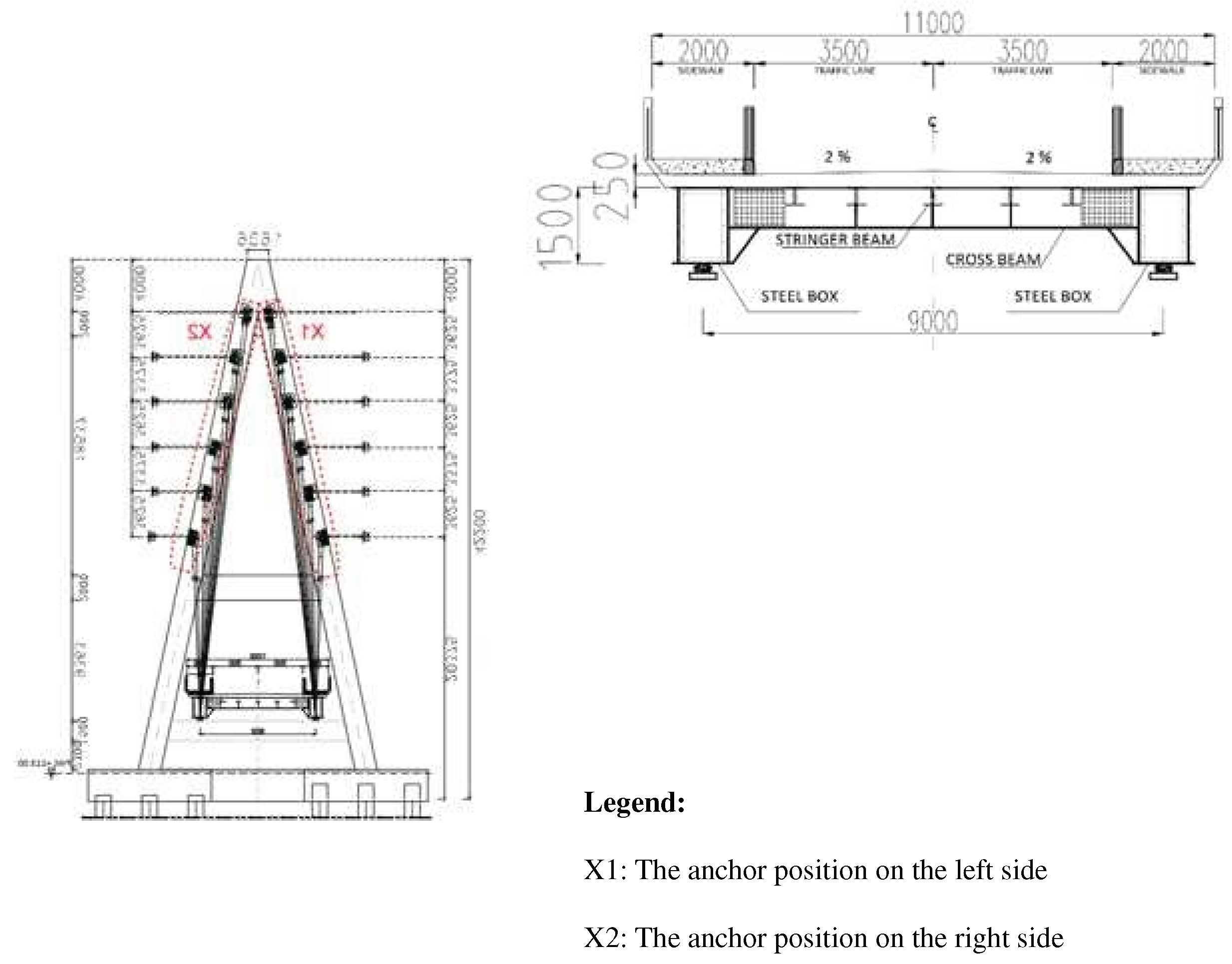

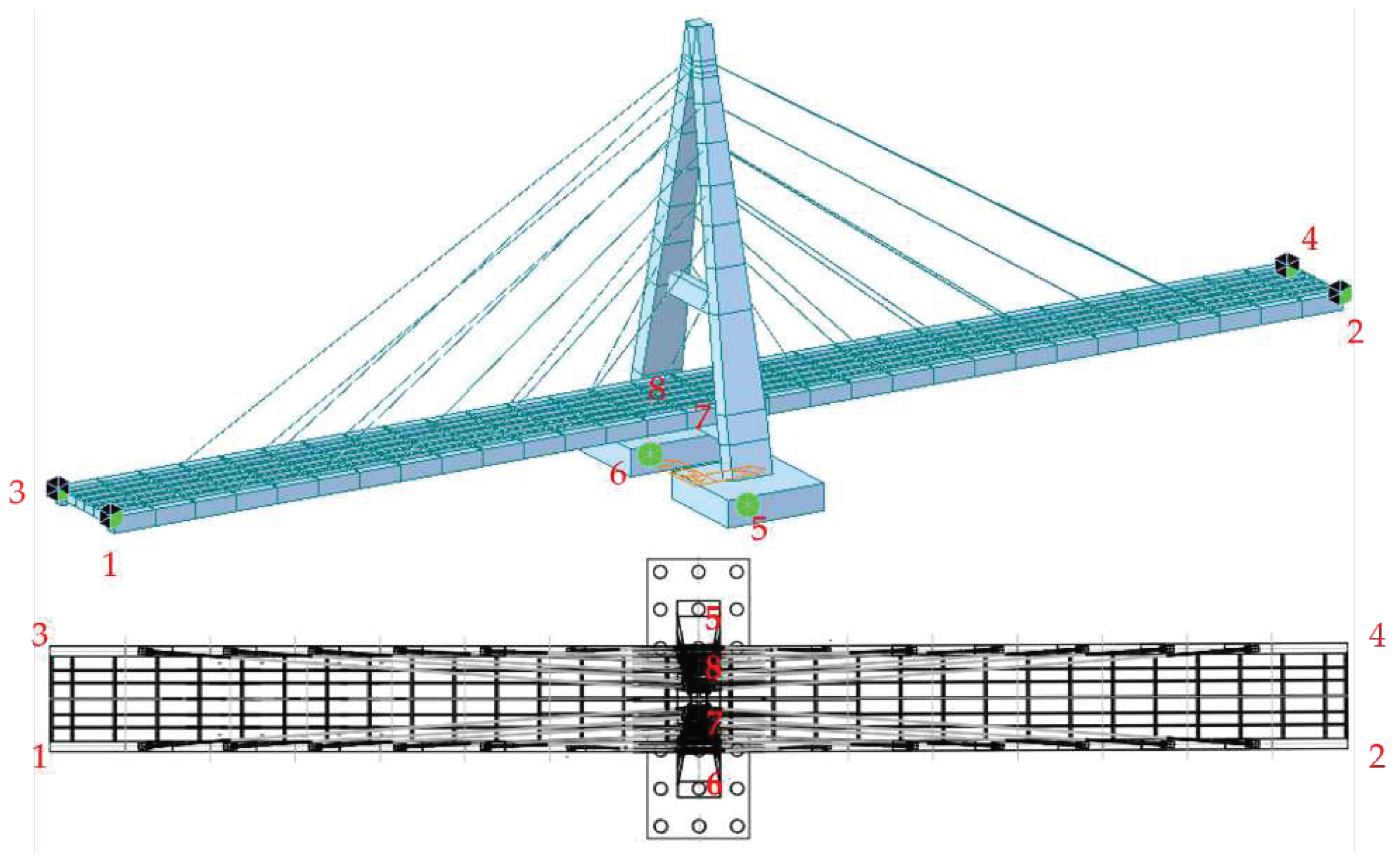

2.2. Finite Element Model of Bridge

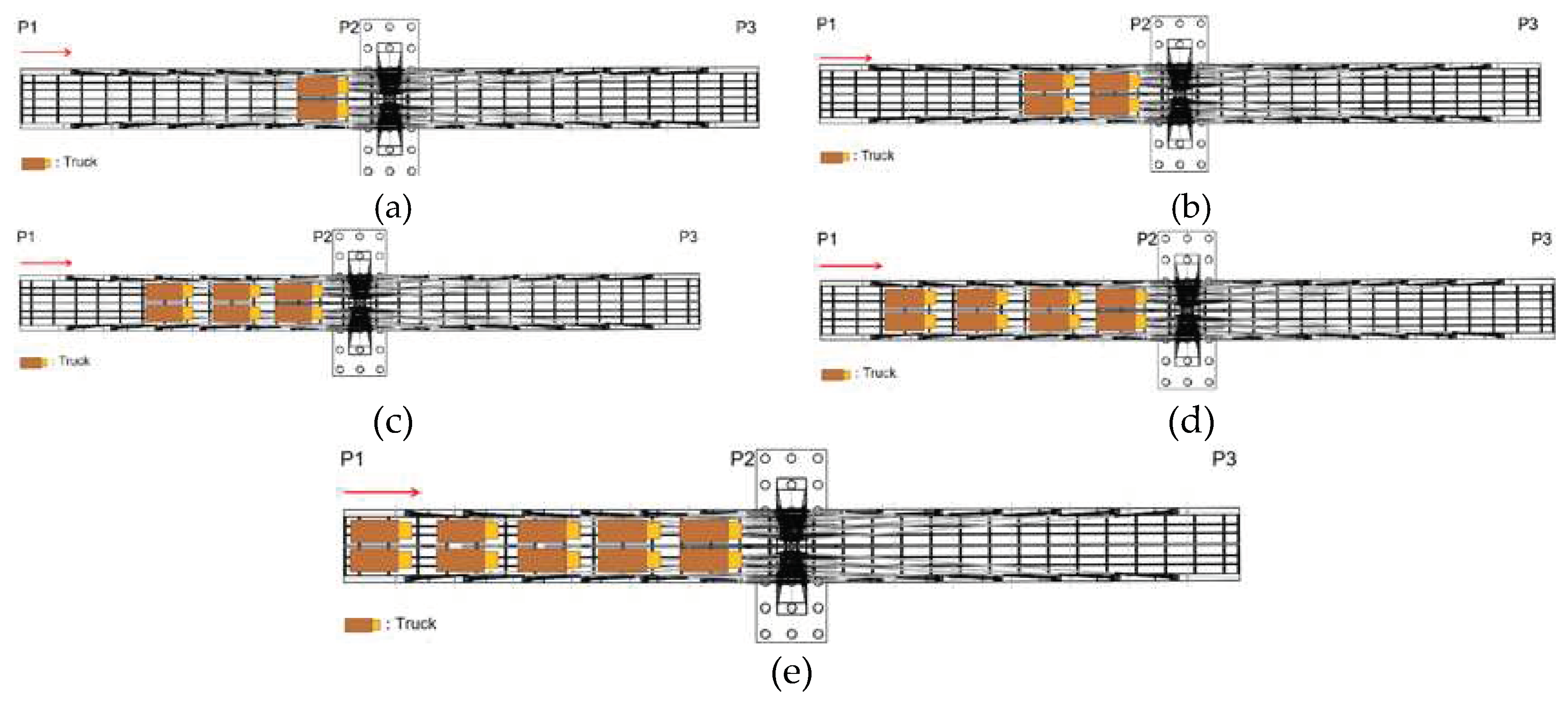

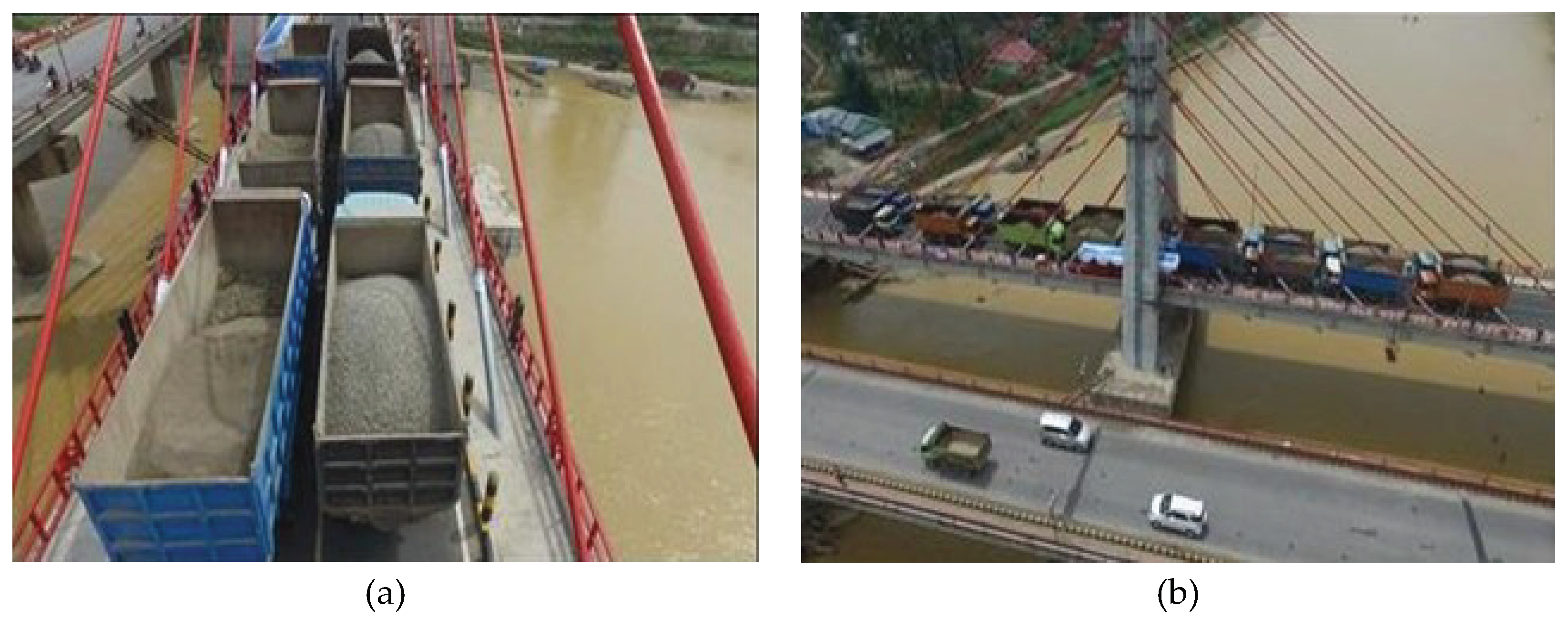

2.3. Static Load Test

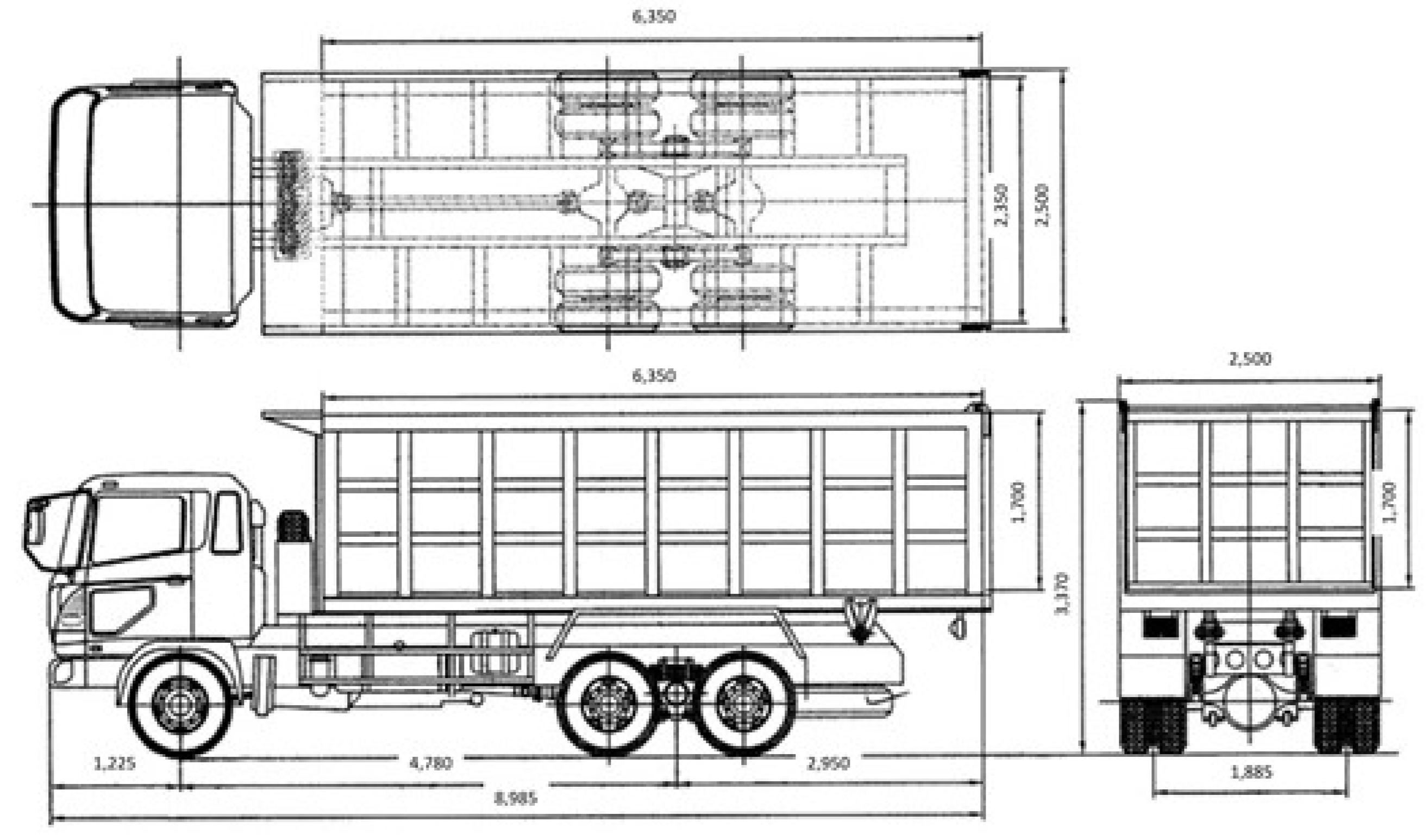

- The length of span L = 2 (61.5 m) = 123 meters and the vehicle floor width is 7.0 meters which results in a vehicle floor area of (61.5 m) (7 m) = 430.5 m2.

- sup>∙ Since L > 30 meters then the UDL, q = 9.0 (0.5 + 15 / L) = 6.70 kN/m2 ≈ 0,683 ton/m2

- Loading test should not be less than 70% of UDL, 70% (6.7 kN/m2) = 4.69 kN/m2 ≈ 0.478 ton/m2.

- Sidewalk live load is 5 kN/m2 (or 0.5 ton/m2), and the width of the sidewalk is 2 meters on the left and right, then the total width of the sidewalk is 4 meters,

- The load test on the sidewalk is 4 m (5 kN/m2) = 20 kN/m x 70% = 14 kN/m ≈ 1.4 t/m and the total pedestrian load test on the bridge is 14 kN/m x 61.5 m = 861 kN ≈ 86.1 tons

- Total UDL and pedestrian load test, (430.5 m2) x (4.69 kN/m2) = 2019 kN + 861 kN = 2880 kN ≈ 294 tons.

- Using a truck with a load of 294 kN or 30 tons including the truck's weight, which means that the number of trucks in one span is (294 tons/ 30 tons) ≈ 10 trucks.

- This truckload is 73% of the UDL design load. The total number of trucks needed for span P1-P2-P3 is 20 trucks.

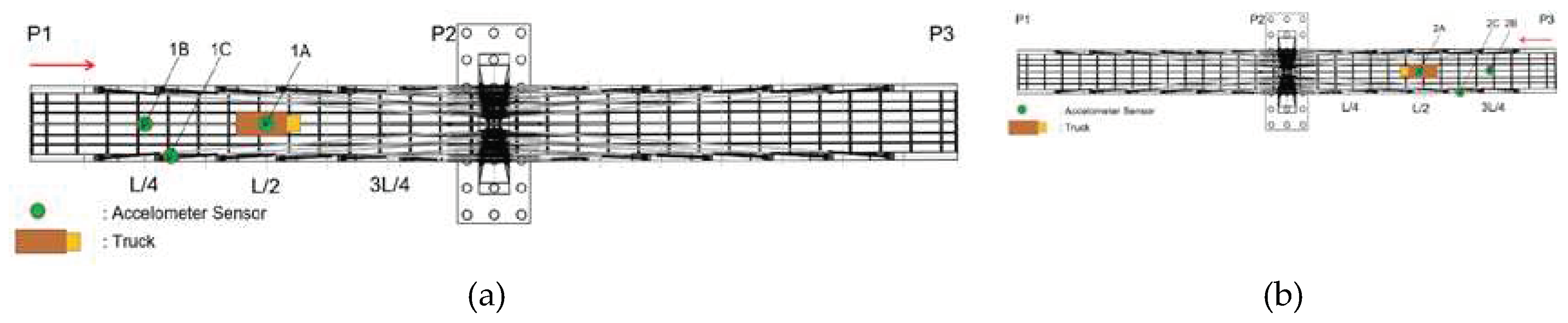

2.4. Dynamic Load Test

3. Results

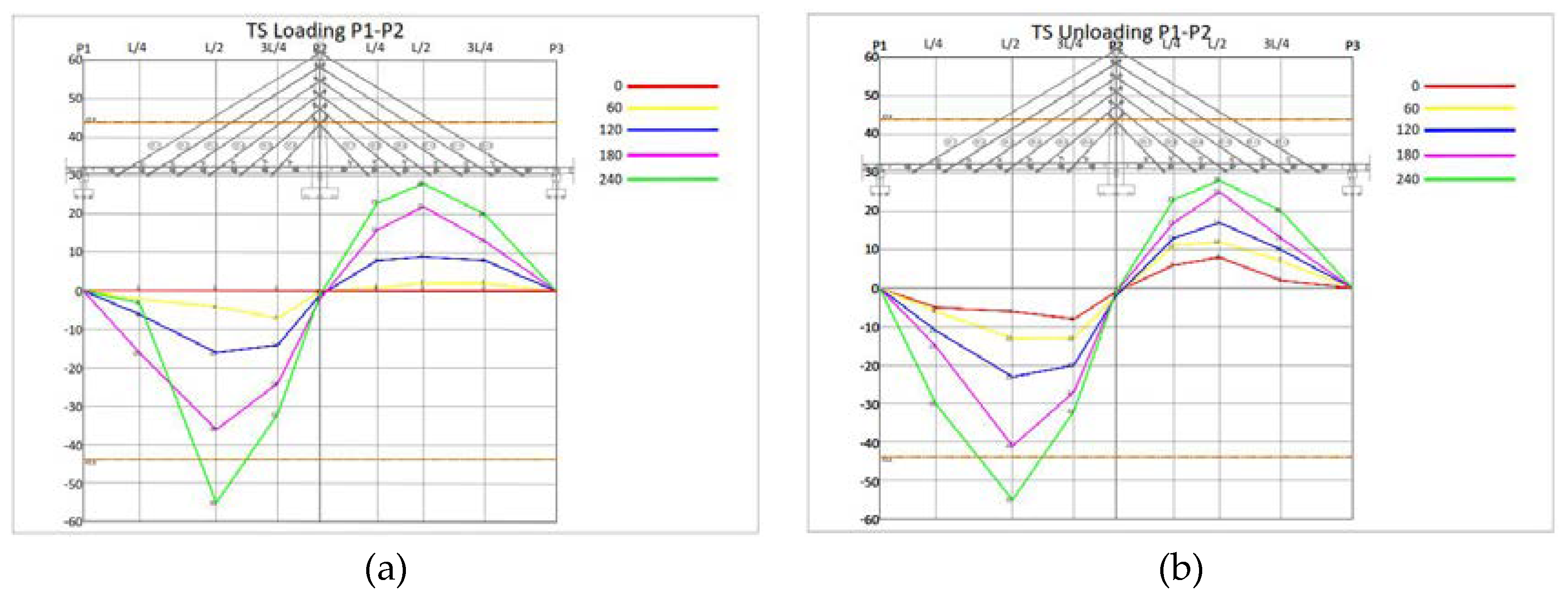

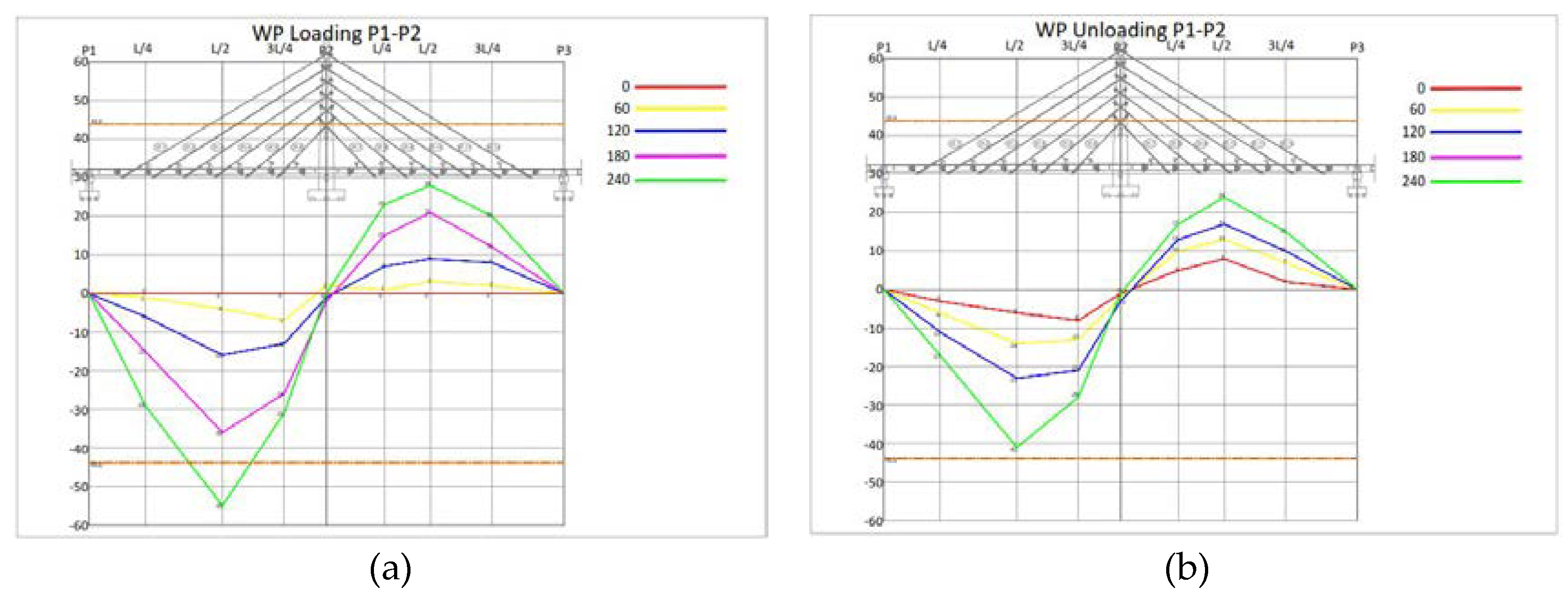

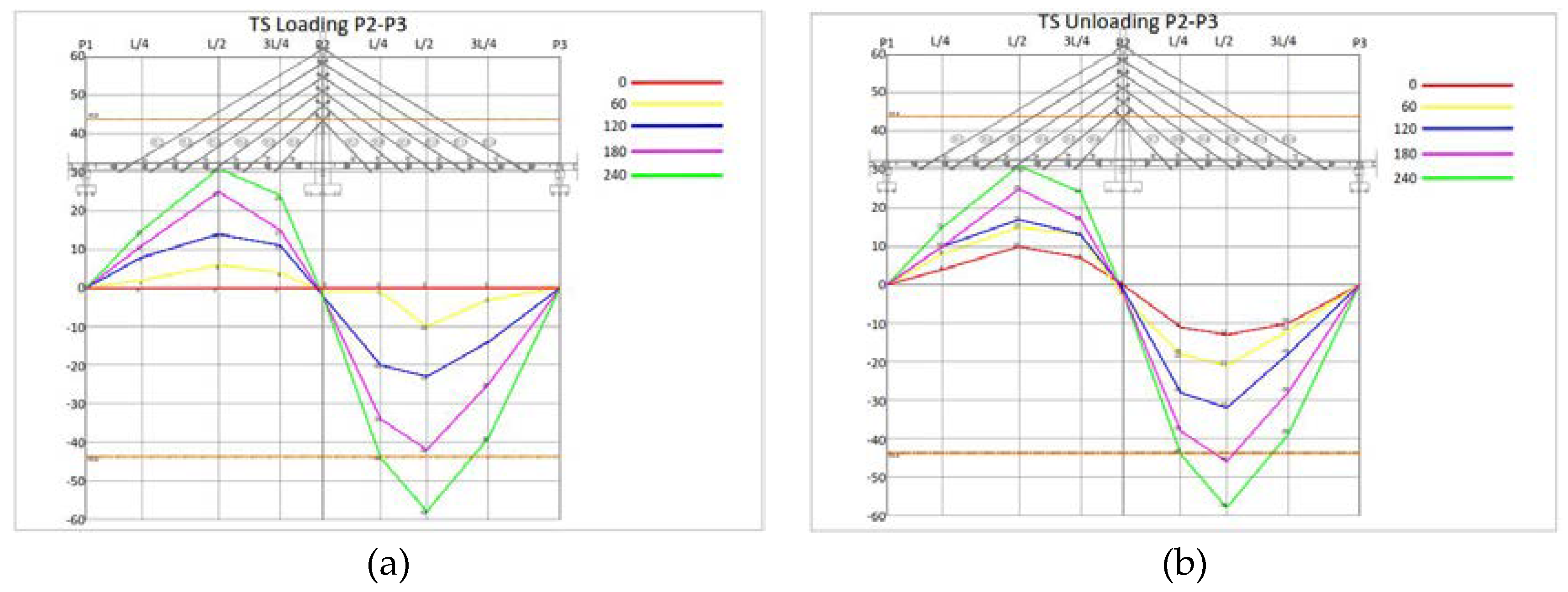

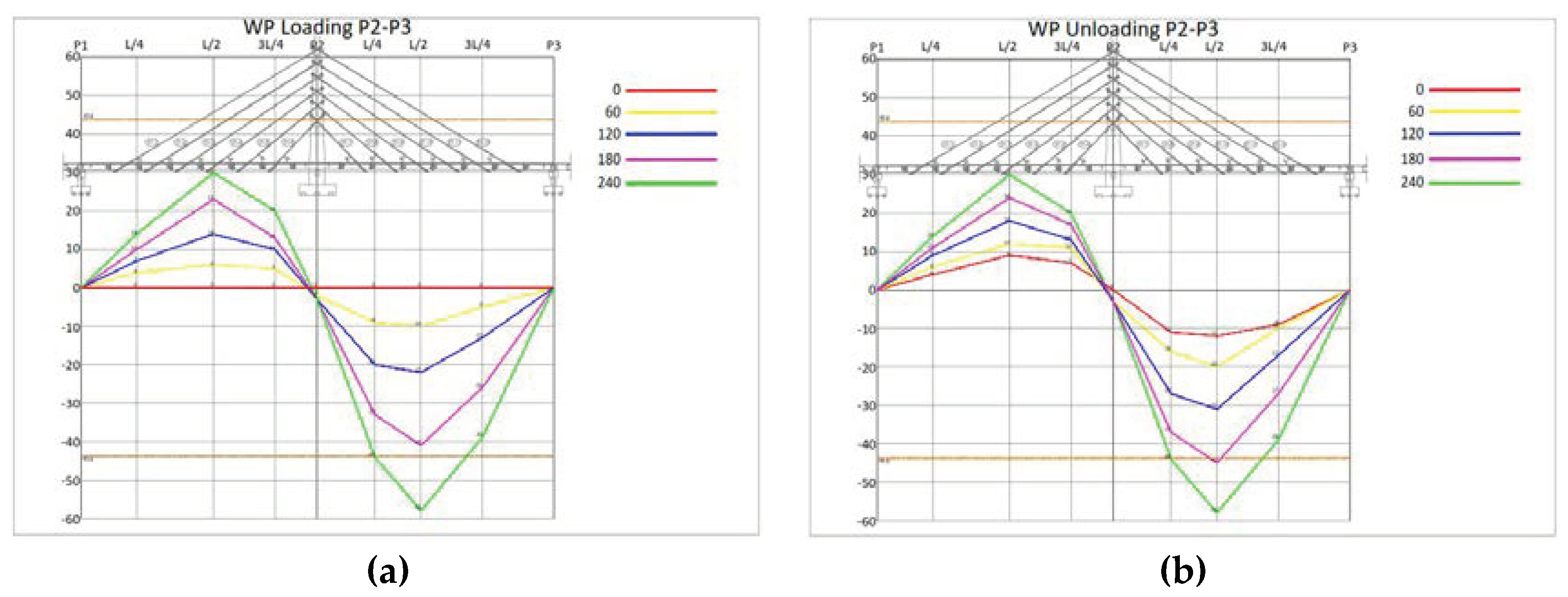

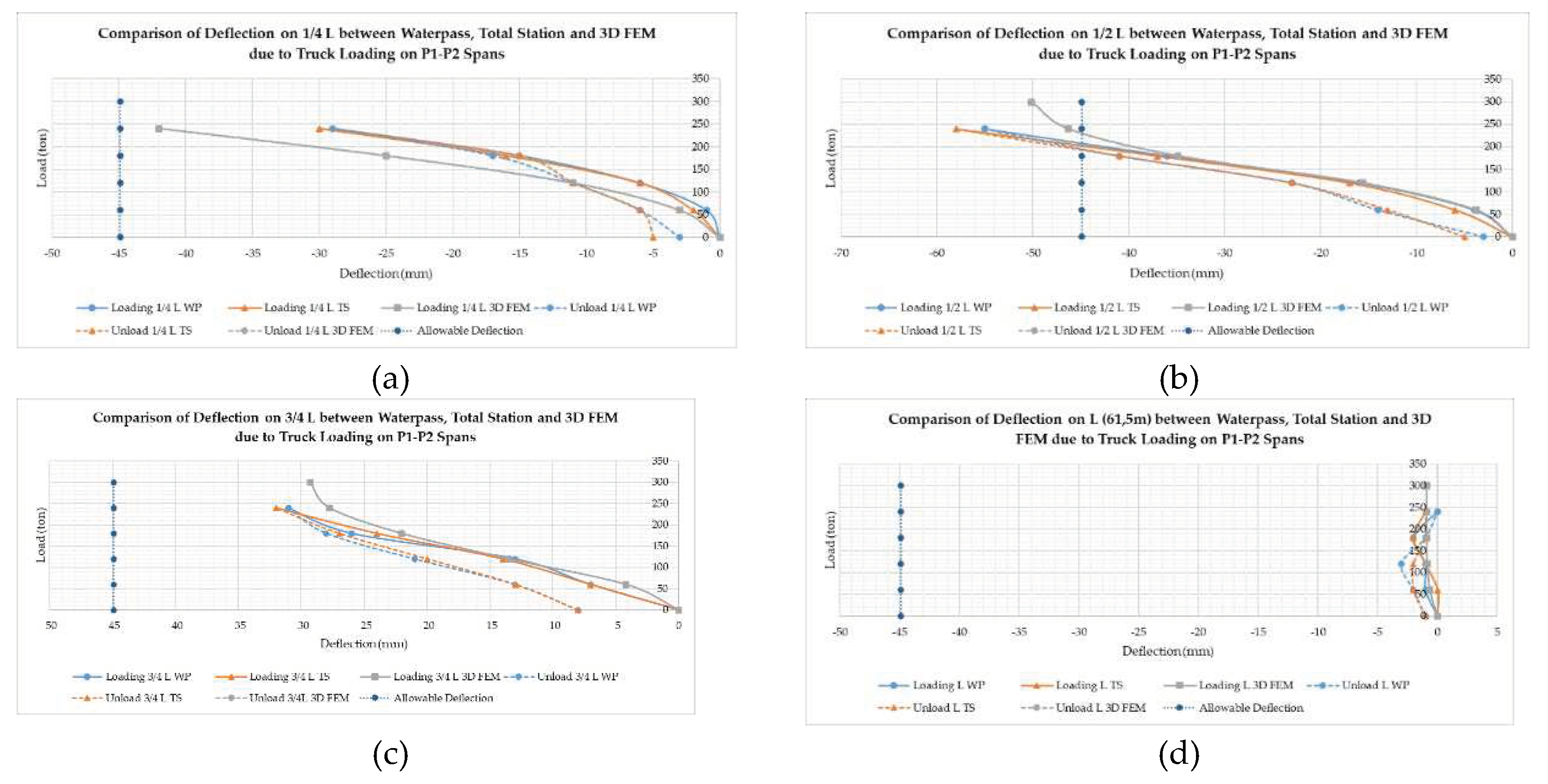

3.1. Result of Static Load Test

3.2. Result of Dynamic Load Test

4. Discussion

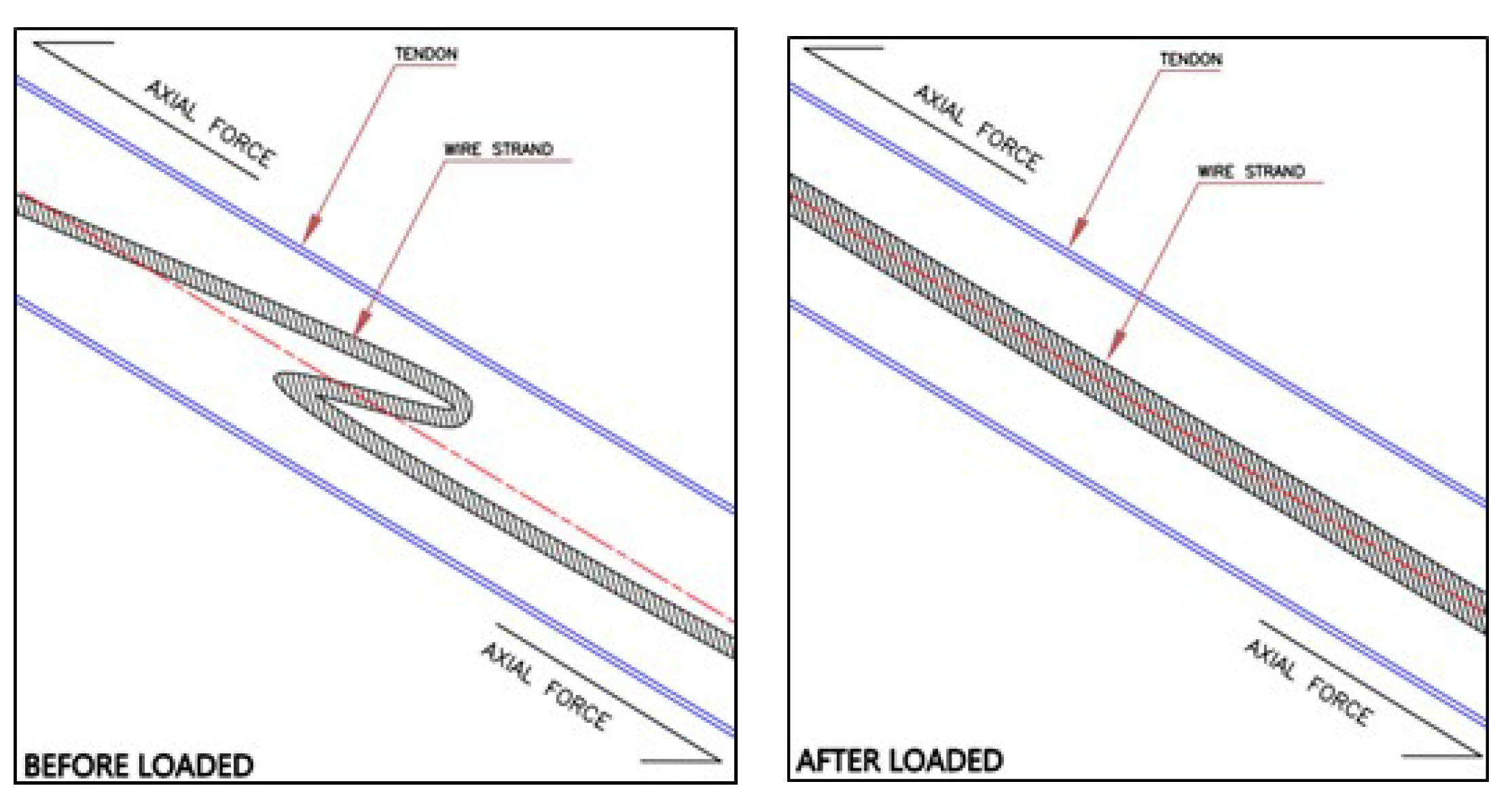

4.1. The Cause of a Loud Clanging Sound

4.2. Cable Stay Takes a Long Time to Return to an Undeformed State

5. Conclusions

- The static test was halted before the planned loads due to excessive deflection. Specifically, the test was stopped at 240 tons instead of 300 tons and 480 tons instead of 600 tons.

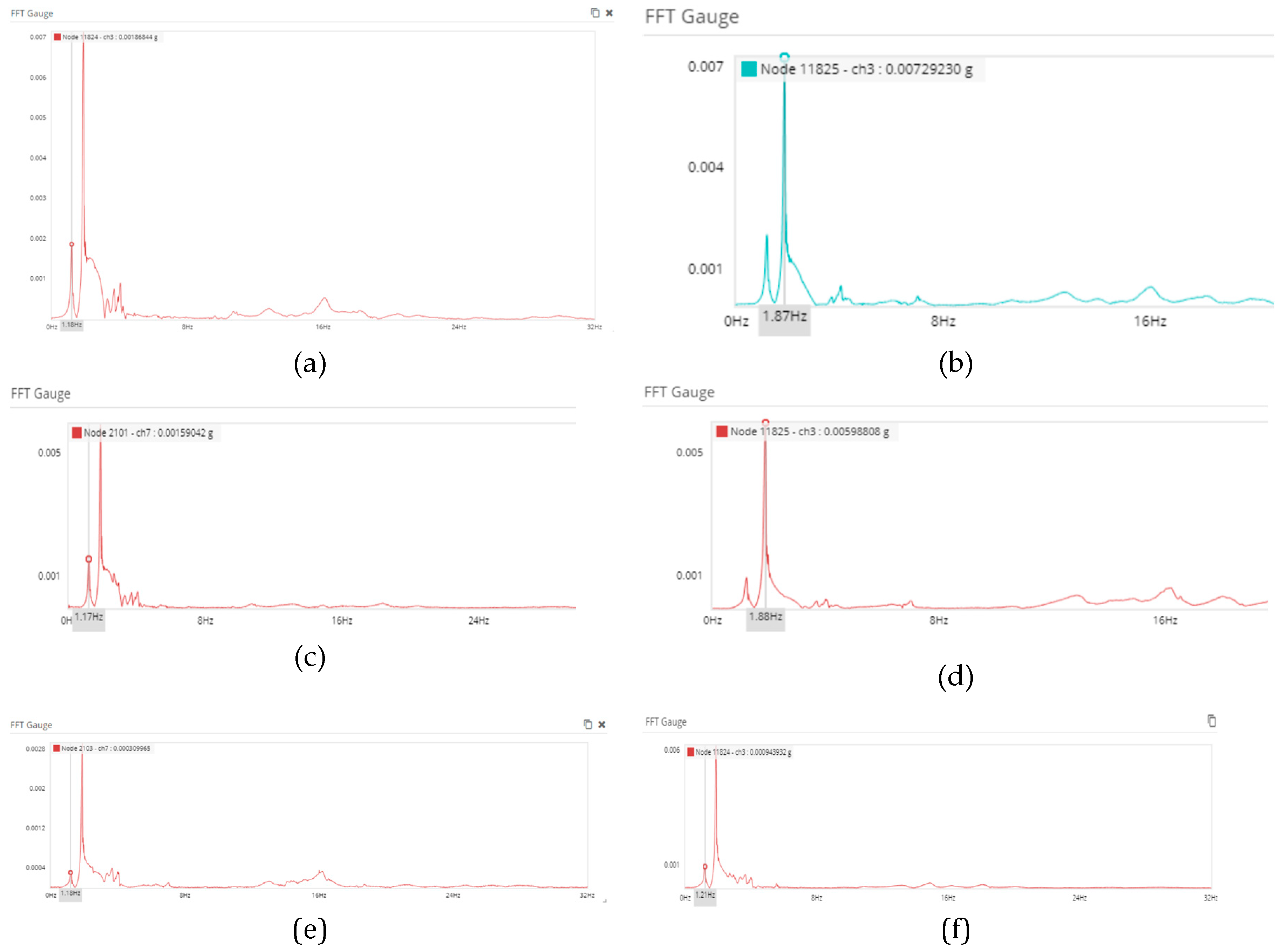

- b. Several dynamic tests consistently report a natural frequency of f = 1.18 Hz for the first peak and f = 1.88 Hz for the second peak.

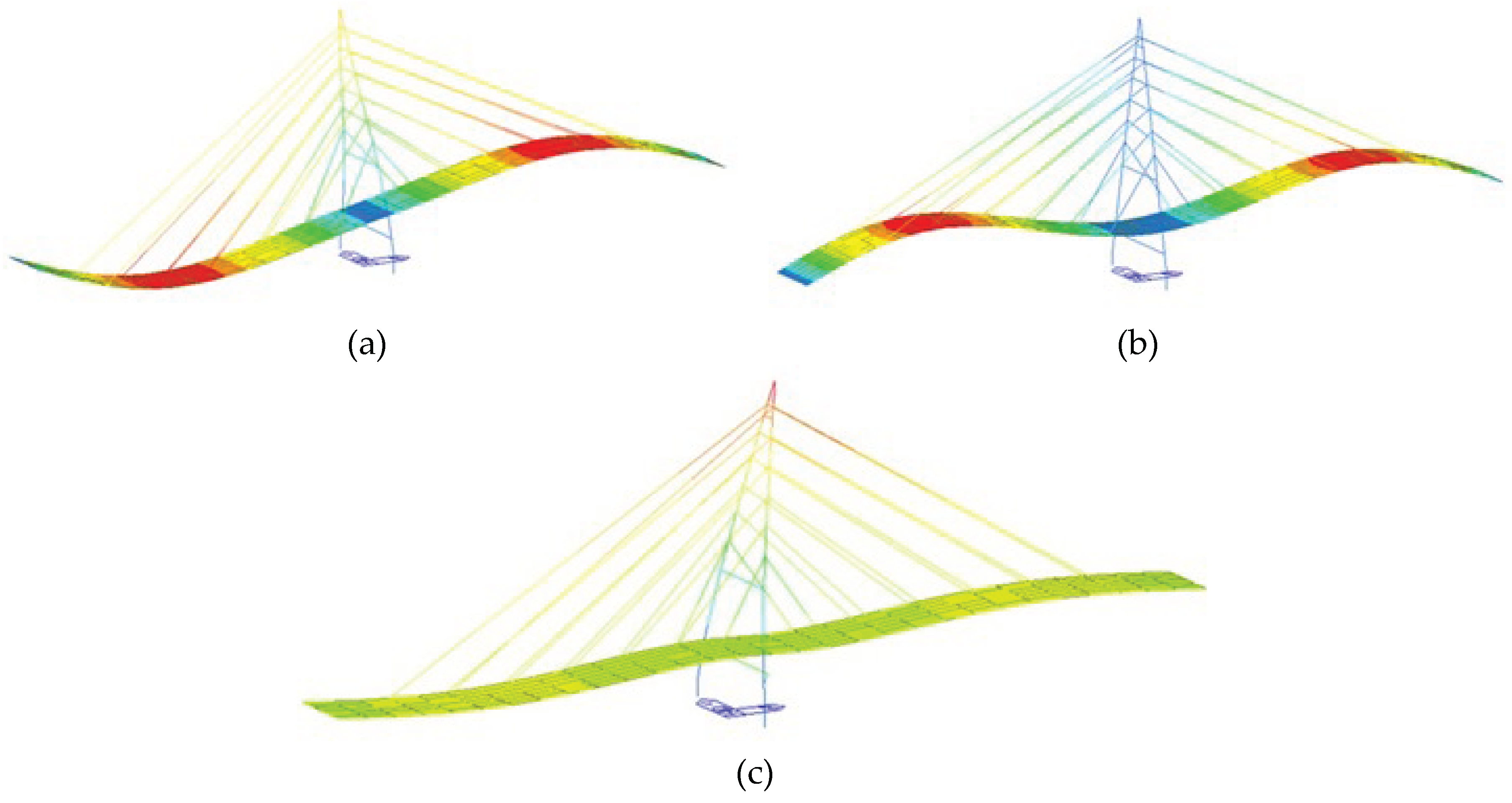

- c. The dynamic tests carried out on the P1-P2 and P2-P3 spans have shown that the two symmetrical spans have the same frequency. The numerical analysis results indicate a natural frequency of f = 1.19 Hz, while the test results show a natural frequency of f = 1.18 Hz. This demonstrates that the Midas structural model aligns with the field measurement results.

- d. There are two options available for opening the bridge to the public: (1) reduce traffic loads up to 70% of the design load by using traffic signs, or (2) carry out continuous monitoring to measure deformation and stress at critical points. The first option was chosen, and as a result, the bridge is currently in good condition.

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chen, W.F. & Duan, L. B. Bridge Engineering Handbook, 1st ed.; CRC Press, Washington, 1999; pp. 89-80.

- Wikipedia. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_longest_cable-stayed_bridge_spans (accessed on 18 May 2021).

- Bayraktar, A., Türker, T., Tadla, J., Kurşun, A., & Erdiş, A. Static and dynamic field load testing of the long span Nissibi cable-stayed bridge. Soil Dynamics and Earthquake Engineering, 2017, 94, 136-157. [CrossRef]

- Salamak, M., Owerko, T., & Lazinski, P. Displacement of cable stayed bridge measured with the use of traditional and modern tecniques. Architecture Civil Engineering Environment, 2016, 4, 89-97. [CrossRef]

- Wilson, J. & Liu, T. Ambient vibration measurement on a cable-stayed bridge. Earthquake Engineering and Structural Dynamics, 1991, 20, 723-747. [CrossRef]

- Casas, J. Full scale dynamic testing of the Alamillo cable-stayed bridge in Sevilla (Spain). Earthquake Engineering and Structural Dynamic, 1995, 24, 35-51. [CrossRef]

- Clemente, P., Marulo, F., Lecce, L., & Bifulco, A. Experimental modal analysis of the Garigliano cable-stayed bridge. Soil Dynamic and Earthquake Engineering, 1998, 485-493. [CrossRef]

- Ren, W. X., Lin, Y. Q, & Peng, X. L. Field load test and numerical analysis of Qingzhou cable-stayed bridge. Journal of Bridge Engineering, 2007, 261-270. [CrossRef]

- Cunha, A., Caetano, E., & Delgado, R. Dynamic tests on large cable-stayed bridge. Journal of Bridge Engineering, 2001, 6(1), 54-62. [CrossRef]

- Fang, I. K., Chen, C. R., & Chang, I. S. Field static load test on Kao-Ping-Hsi cable-stayed bridge. Journal of Bridge Engineering, 2004, 9(6), 531-540. [CrossRef]

- Jian, X.Y., Lei, Z., & Gang, L.X. Static loading test and assessment of cable-stayed bridge which specialized for rail transit. Archives of Current Research International, 2015, 2(2), 59-65. [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y. C., Zhang, Q. W., & Liu, J. F. Dynamic property evaluation of a long-span cable-stayed bridge (Sutong bridge) by a Bayesian method. International Journal of Structural Stability and Dynamics, 2019, 19(01), 1940010. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X., Xu, Y.L., & Zhu, Q. Multiscale modeling and model updating of a cable-stayed bridge. II : Model updating using modal frequencies and influence lines. Journal of Bridge Engineering, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Ding, Y., & Li, A. Finite element model updating for the Runyang cable-stayed bridge tower using ambient vibration test results. Advance in Structural Engineering, 2008, 11, 323-335. [CrossRef]

- Brownjohn, J. M., & Xia, P. Q. Dynamic assessment of curved cable-stayed bridge by model updating. Journal of structural engineering, 2000, 126(2), 252-260. [CrossRef]

- Li, H., & Ou, J. The state of the art in structural health monitoring of cable-stayed bridge. Journal of Civil Structural Health Monitoring, 2015, 6, 43-67. [CrossRef]

- Ge, C., & Chen, A. Vibration characteristics identification of ultra-long cables of a cable stayed bridge in normal operation based on half-year monitoring data, Structure and Infrastructure Engineering, 2019, 15(12), 1567-1582. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Mao, J.X., & Li, A.Q. Modal identification of Sutong Cable-Stayed Bridge during Typhoon Haikui using wavelet transform method, Journal of Performance of Constructed Facilities, 2016, 30(6). [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y., & Sun, L. A comprehensive study of the thermal response of a long-span cable-stayed bridge : from monitoring phenomena to underlying mechanism, Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, 2019, 124, 330-348. [CrossRef]

- Santoso, H. T. Penilaian Kondisi Jembatan Untuk Persyaratan Laik Fungsi Dengan Uji Getar. Portal: Jurnal Teknik Sipil, 2020, 12(1), 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Setiati, N. R., & Surviyanto, A. Analisis Uji Beban Kendaraan Terhadap Jembatan Integral Penuh (Loading Test Analysis of Full Integral Bridge). Jurnal Teknik Sipil, 2013, 190-204.

- Kim, S. H., Park, S. Y., & Jeon, S. J. Long-Term Characteristics of Prestressing Force in Post-Tensioned Structures Measured Using Smart Strands. Applied Sciences, 2020 10(12), 4084. [CrossRef]

| Element | Section | Size (mm) |

Elastic Modulus (MPa) | Yield Stress (MPa) |

Ultimate Stress (MPa) |

Poisson Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steel Element | ||||||

| Primary girder | Box | 1200x1500 thickness = 30 |

205000 | 325 | 490 | 0,3 |

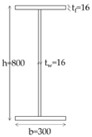

| Cross girder | IWF | 800.300.16.24

|

||||

| Stringer beam | H | 350.350.12.19 | ||||

| IWF | 350.175.7.11 | |||||

| Concrete Element | ||||||

| Main pylon (non-prismatic) |

Rectangle | 1700x4000 bottom |

25743 | - | - | 0,3 |

| 1700x1500 top | ||||||

| Crossbeam bottom pylon | 1500x100 | |||||

| Crossbeam middle pylon | 2000x1000 | |||||

| Cable Element | ||||||

| Material | : A416-270 (Normal Relaxation Strand) – ASTM A416-74 | |||||

| Diameter | : 0.6 inch (15.24 mm) | |||||

| Diameter+epoxy | : 0.648 inch (16.46 mm) | |||||

| Modulus elasticity | : E= 195000 MPa | |||||

| Poisson ratio | : = 0.3 | |||||

| Ultimate stress | : Fs’=1861.6 MPa | |||||

| Yield stress | : Fpy = 1675.4 MPa | |||||

| Allowable stress (0,45 ultimate stress) |

: Fallow = 837.7 MPa | |||||

| Cable | Cable Force (N) | Number of strands |

|---|---|---|

| ST 1, 12 | 1254825 | 22 |

| ST 2, 11 | 850768 | 22 |

| ST 3, 10 | 556230 | 22 |

| ST 4, 9 | 513760 | 22 |

| ST 5, 8 | 573650 | 22 |

| ST 6, 7 | 636090 | 19 |

| Node/DOF | Dx | Dy | Dz | Rx | Ry | Rz |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 7* | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 8* | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1: degree of freedom in this direction is restrained | ||||||

| 0: degree of freedom to this direction is released | ||||||

| *: the boundary condition is link | ||||||

| Scheme | Load Impact Position | Accelerometer Position |

|---|---|---|

| 1A | L/2 of P1–P2 | L/2 of P1-P2 |

| 1B | L/4 of P1-P2 | |

| 1C | Sidewalk of P1-P2 | |

| 2A | L/2 of P2–P3 | L/2 P2-P3 |

| 2B | 3L/4 P2-P3 | |

| 2C | Sidewalk P2-P3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).