Submitted:

02 January 2024

Posted:

04 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Yield of Extraction

2.2. Antibacterial Activity

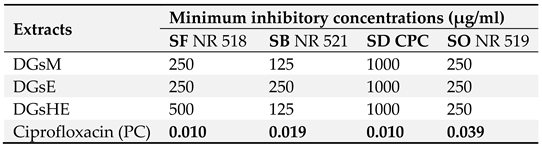

2.2.1. Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations (MICs)

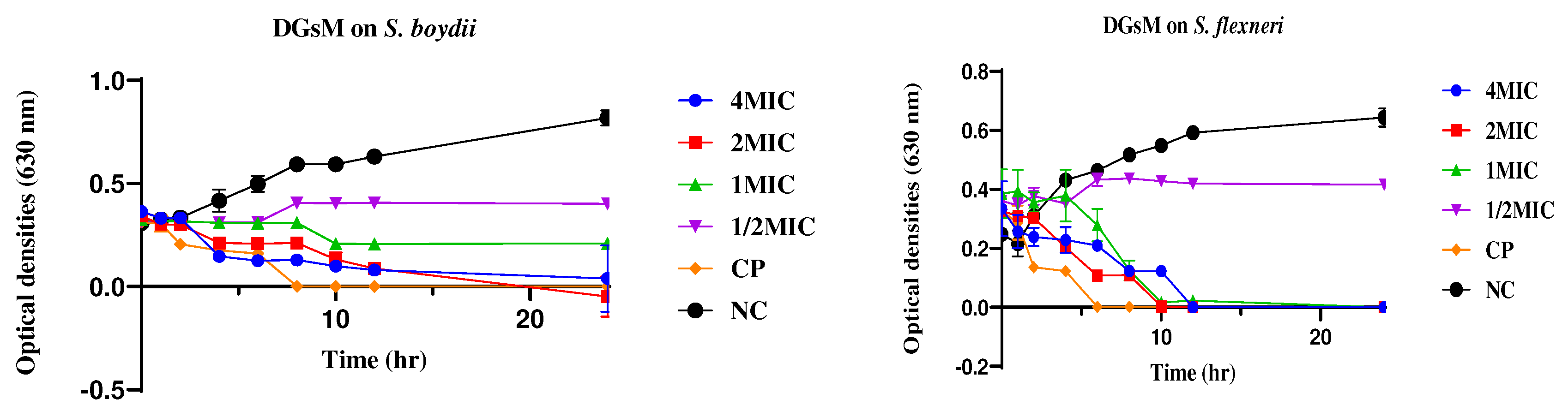

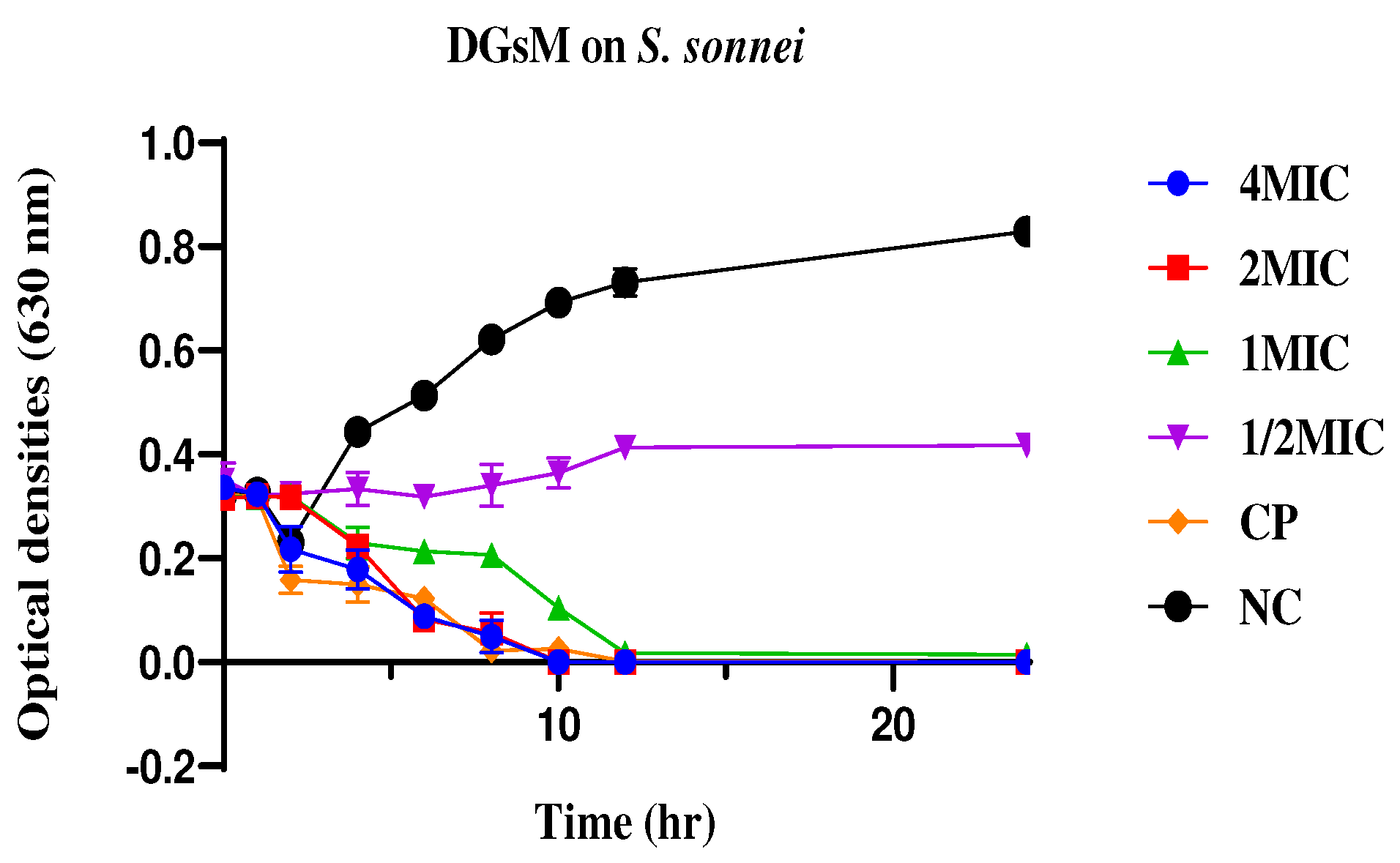

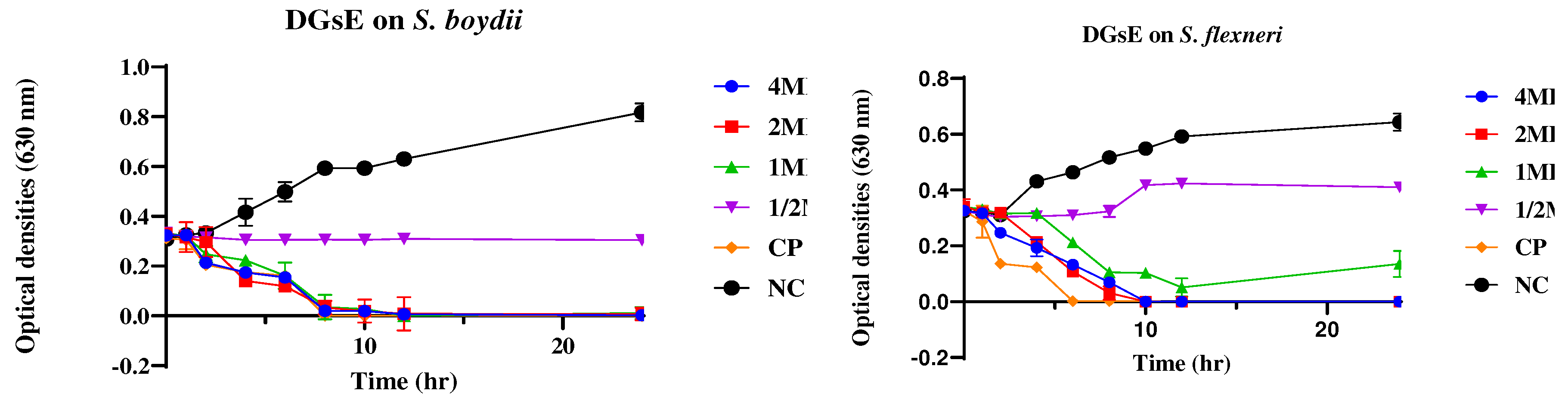

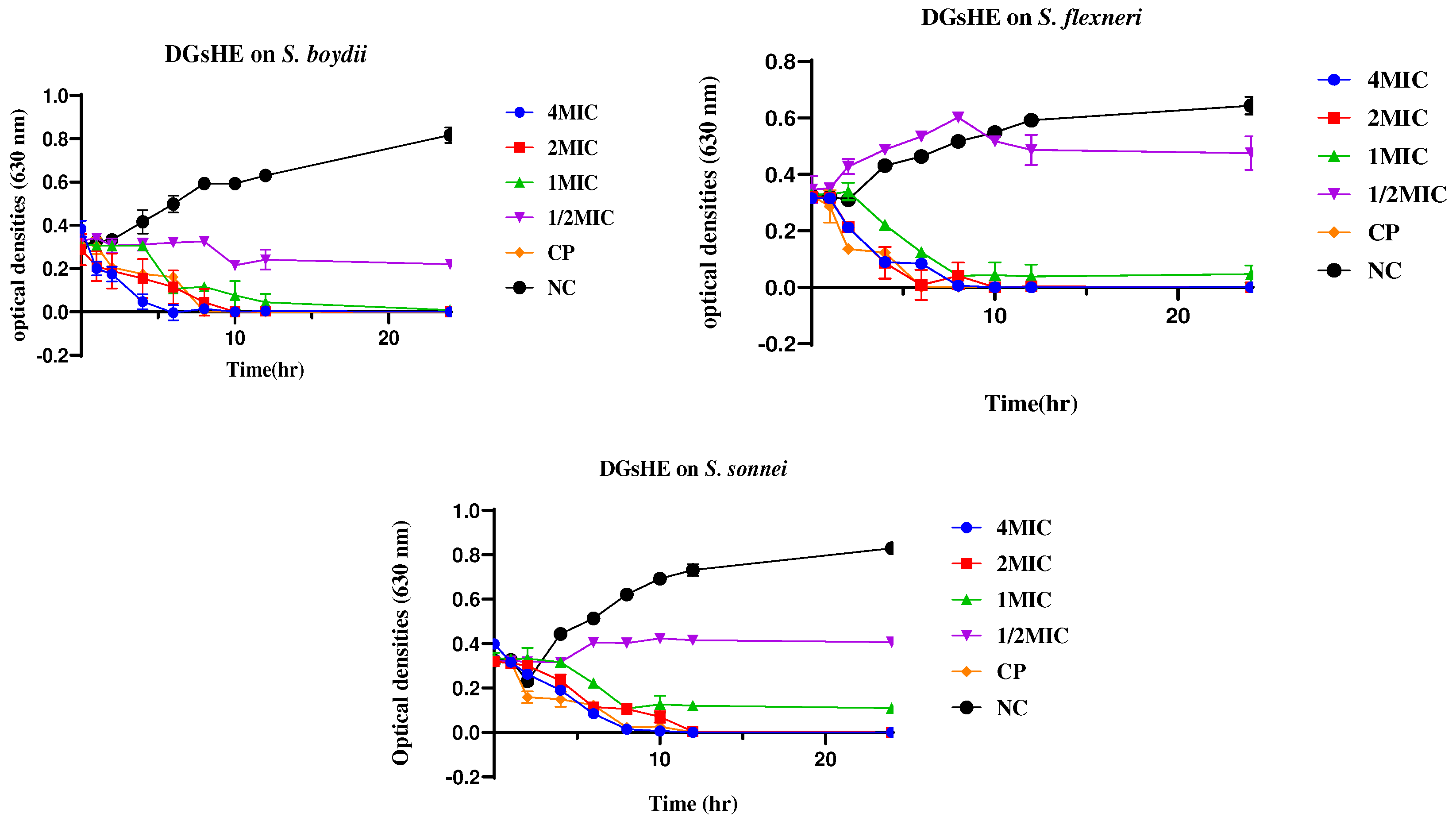

2.2.2. Time Kill Kinetics

2.2.3. Plausible Antibacterial Mechanisms of Action

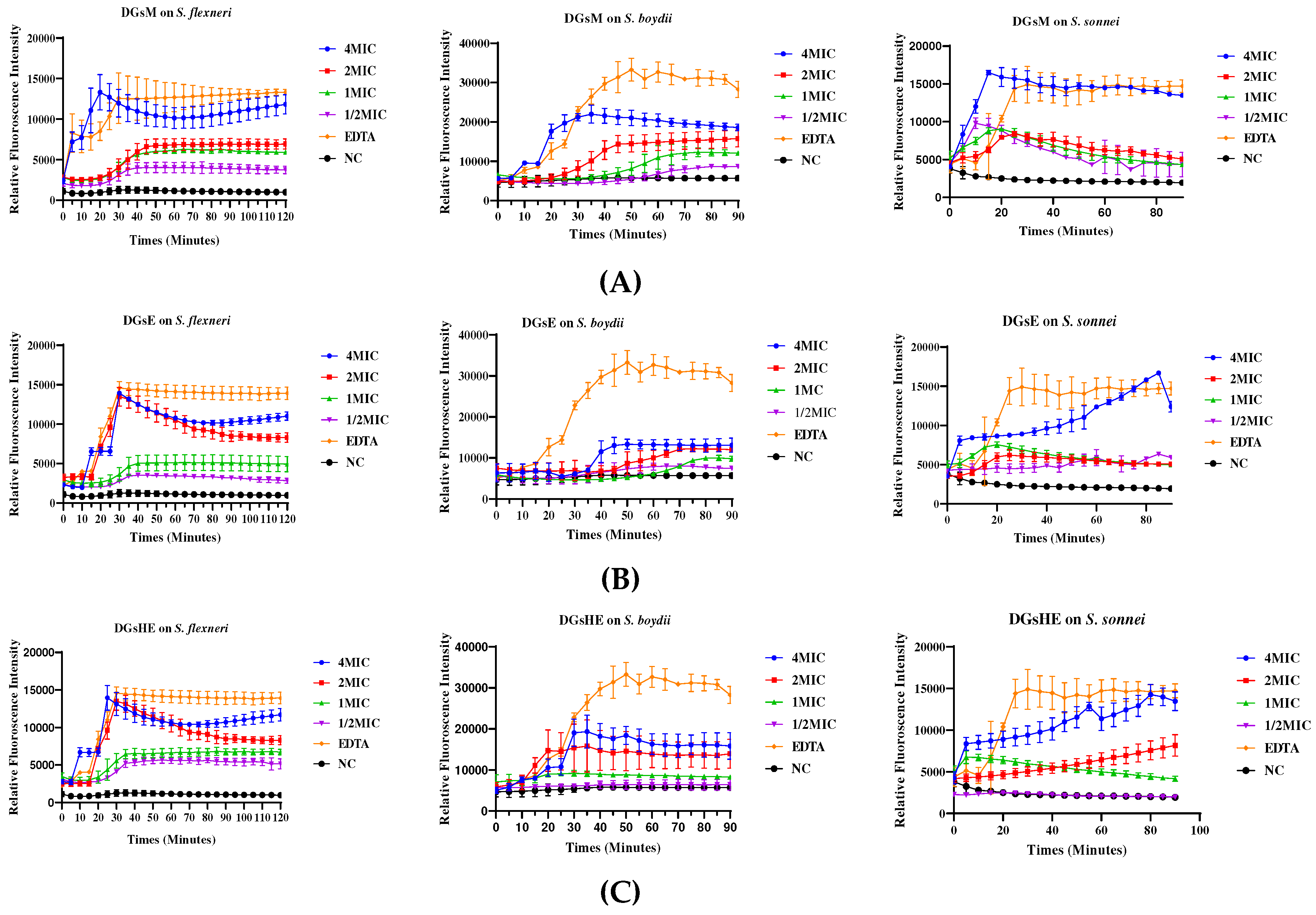

Effect of Extracts on N-phenylnaphthylamine Uptake by Bacteria

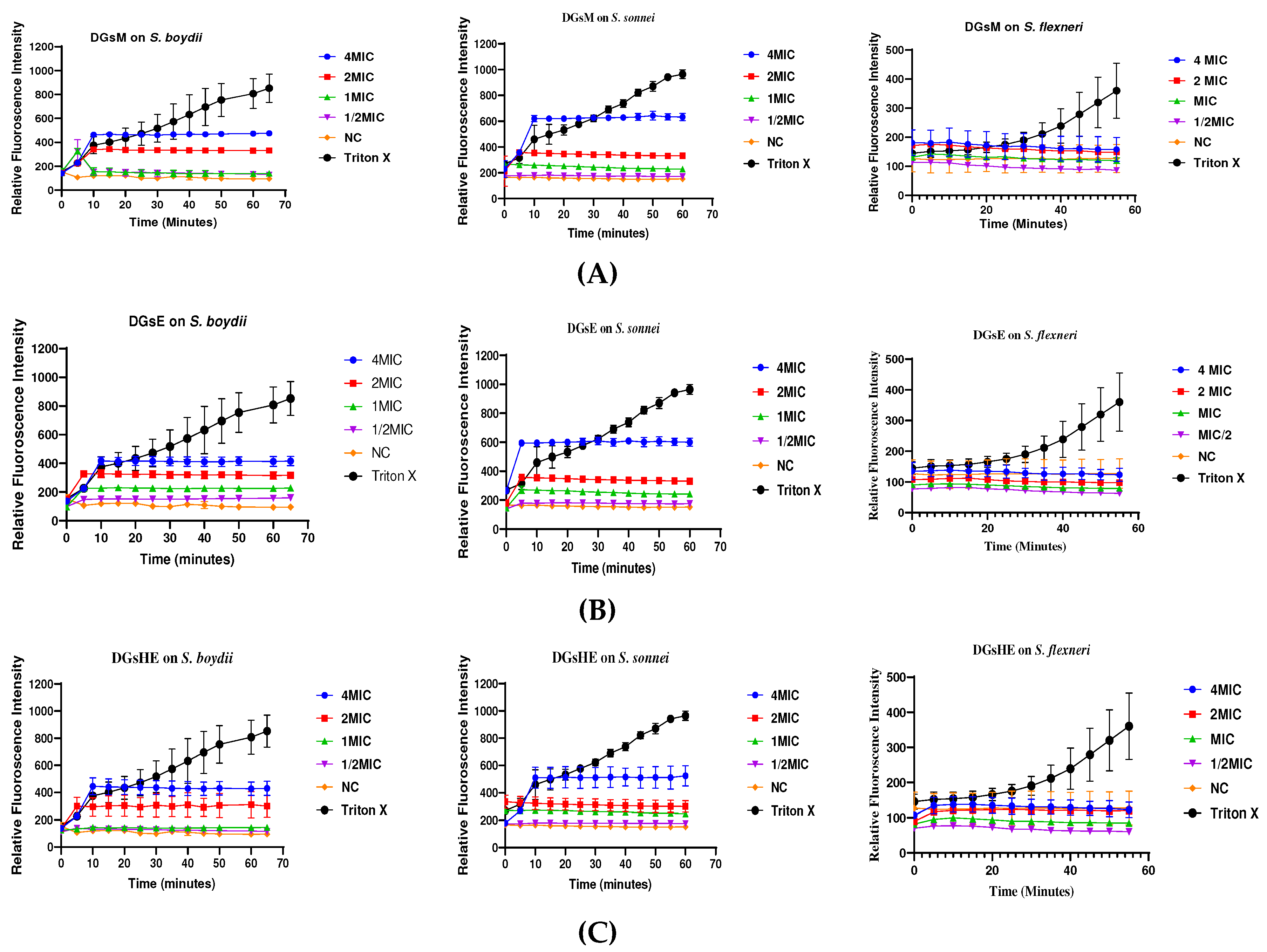

Propidium Iodide Uptake Assay

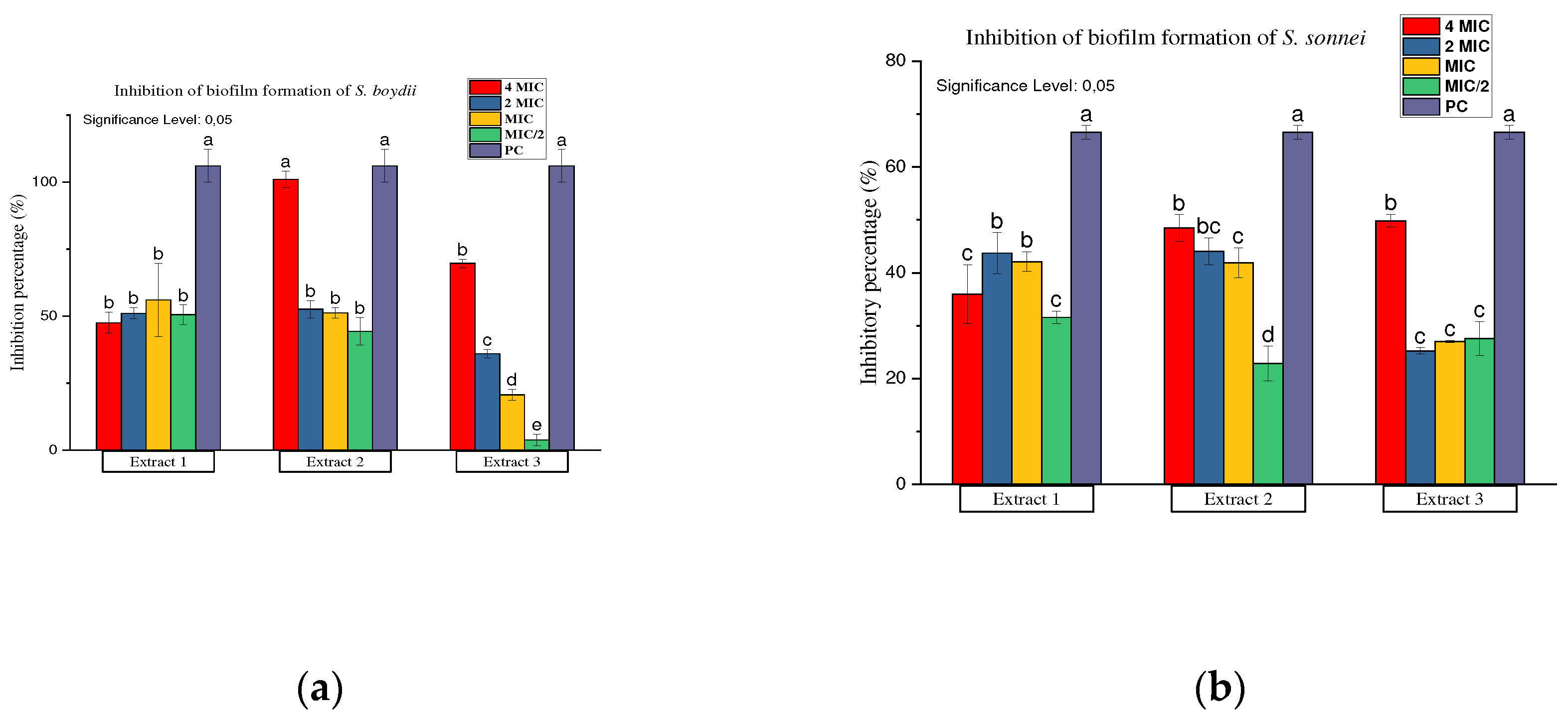

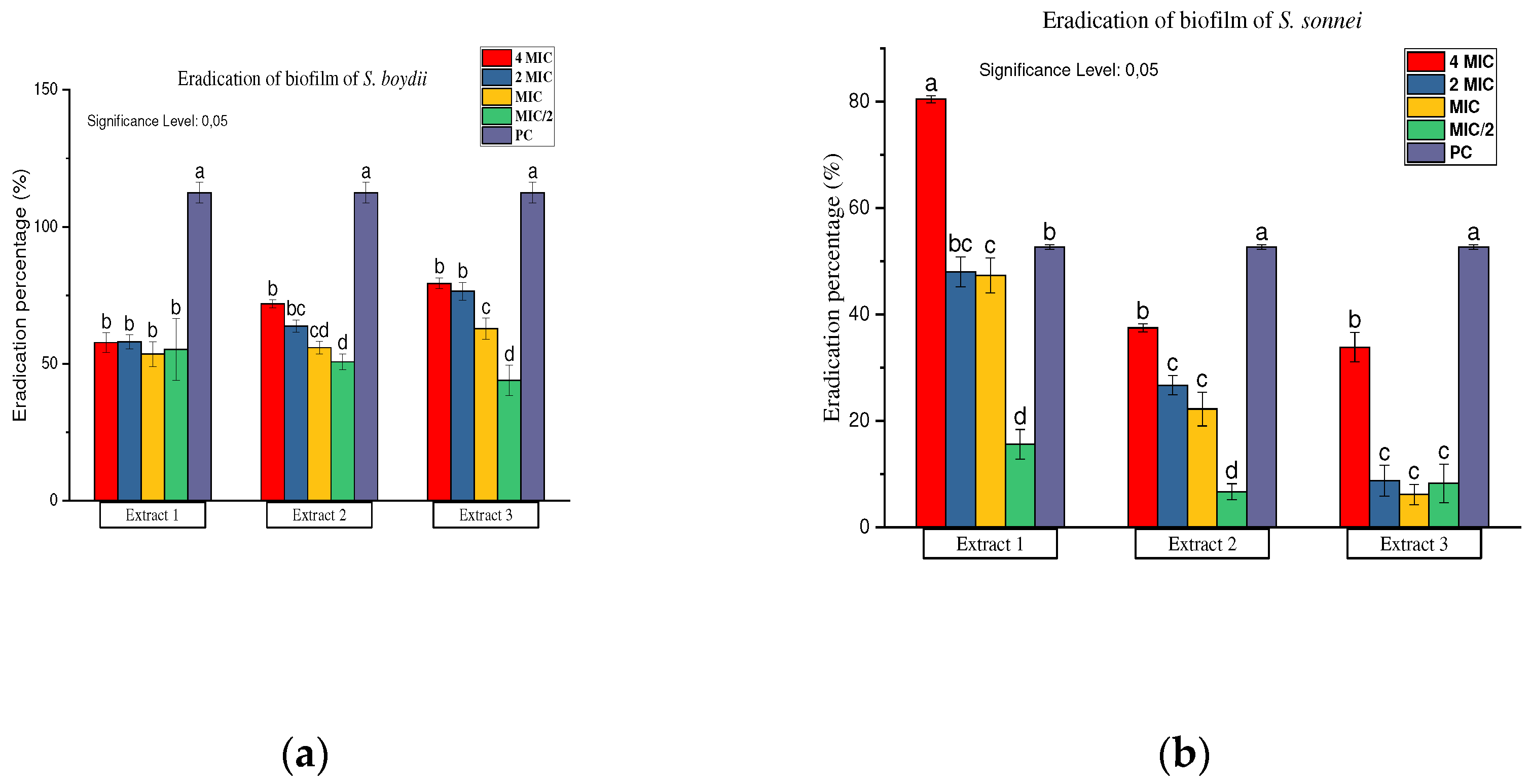

Inhibition and Eradication of Bacterial Biofilms

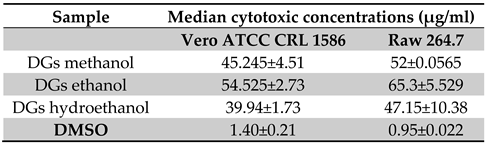

2.2.4. Cytotoxicity Studies

3. Discussion

4. Material and Methods

4.1. Material

4.1.1. Plant Material

4.1.2. Microbiological Material

4.2. Methods

4.2.1. Antibacterial Activity

4.2.2. Time Kill Kinetics

4.2.3. Evaluation of Possible Mechanisms of Action

Membrane Permeabilization

Antibiofilm Activity

4.2.4. Cytotoxicity Test

Determination of Median Cytotoxic Concentrations (CC50)

4.3. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Dahmoshi, H.; Al-Khafaji, N.; Al-Allak, M.; Salman, W.; Alabbasi, A. A review on shigellosis: Pathogenesis and antibiotic resistance. Drug Invent. Today 2020, 15(5) 793-798.

- Puzari, M.; Sharma, M.; Chetia, P. Emergence of antibiotic resistant Shigella species: A matter of concern. J. Infect. Public Health 2018, 11, 451-454. [CrossRef]

- Merzon, E.; Gutbir, Y.; Vinker, S.; Golan Cohen, A.; Horwitz, D.; Ashkenazi, S.; Sadaka, Y. Early childhood shigellosis and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A population-based cohort study with a prolonged follow-up. J. Atten. Disord. 2021, 25, 1791-1800. [CrossRef]

- The World Health Organization (WHO), 2023. Diarrhoeal disease. The Key Facts. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diarrhoeal-disease, Accessed on 23rd December 2023.

- Reiner, R.C.Jr.; Graetz, N.; Casey, D.C.; Troeger, C.; Garcia, G.M.; Mosser, J.F.; Deshpande, A.; Swartz, S.J.; Ray, S.E.; Blacker, B.F.; Rao, P.C.; Osgood-Zimmerman, A.; Burstein, R.; Pigott, D.M.; Davis, I.M.; Letourneau, I.D.; Earl, L.; Ross, J.M.; Khalil, I.A.; Farag, T.H.; Brady, O.J.; Kraemer, M.U.G.; Smith, D.L.; Bhatt, S.; Weiss, D.J.; Gething, P.W.; Kassebaum, N.J.; Mokdad, A.H.; Murray, C.J.L.; Hay, S.I. Variation in childhood diarrheal morbidity and mortality in Africa, 2000-2015. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379 (12) 1128-1138. [CrossRef]

- Njunda, A.L.; Assob, J.C.; Nsagha, D.S.; Kamga, H.L.; Awafong, M.P.; Weledji, E.P. Epidemiological, clinical features and susceptibility pattern of shigellosis in the buea health district, Cameroon. BMC Res. Notes 2012, 5, 54. [CrossRef]

- Ateudjieu, J.; Bita’a, L.; Guenou, E.; Chebe, A.; Chukuwchindun, B.; Goura, A.; Bisseck, A. Profile and antibiotic susceptibility pattern of bacterial pathogens associated with diarrheas in patients presenting at the Kousseri Regional Hospital Anne, Far North, Cameroon. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2018, 29 (170).

- Aslam, A.; Okafor, C.N. Shigella, in: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL), 2022.

- Sheikh, A.F.; Moosavian, M.; Abdi, M.; Heidary, M.; Shahi, F.; Jomehzadeh, N.; Seyed-Mohammadi, S.; Saki, M.; Khoshnood, S. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of Shigella species isolated from diarrheal patients in Ahvaz, southwest Iran. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019, 12, 249-253. [CrossRef]

- Libby, T.E.; Delawalla, M.L.M.; Al-Shimari, F.; MacLennan, C.A.; Vannice, K.S.; Pavlinac, P.B. Consequences of Shigella infection in young children: a systematic review. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 129, 78-95. [CrossRef]

- 11. The World Health Organization (WHO), 2021: Global priority pathogens. Google Scholar [WWW Document]. URL https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?author=World%20Health%20Organization&publication_year=2017&journal=WHO+global+priority+pathogens+list+of+antibiotic-resistant+bacteria (accessed 5.22.23).

- Ranjbar, R.; Farahani, A. Shigella: Antibiotic-resistance mechanisms and new horizons for treatment. Infect. Drug Resist. 2019, 12, 3137-3167. [CrossRef]

- Cowan, M.M. Plant products as antimicrobial agents. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1999, 12(4), 564-582. [CrossRef]

- Tameye, N.S.J.; Akak, C.M.; Happi, G.M.; Frese, M.; Stammler, H.-G.; Neumann, B.; Lenta, B.N.; Sewald, N.; Nkengfack, A.E. Antioxidant norbergenin derivatives from the leaves of Diospyros gilletii De Wild (Ebenaceae). Phytochem. Lett. 2020, 36, 63-67. [CrossRef]

- Maroyi, A. Diospyros lycioides Desf.: Review of its botany, medicinal uses, pharmacological activities and phytochemistry. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Biomed. 2018, 8, 130. [CrossRef]

- Rauf, A.; Uddin, G.; Patel, S.; Khan, A.; Halim, S.; Bawazeer, S.; Ahmad, K.; Muhammad, N.; Mubarak, M. 2017. Diospyros, an under-utilized, multi-purpose plant genus: A review. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 91, 714–730. [CrossRef]

- Anywar, G.U.; Kakudidi, E.; Oryem-Origa, H.; Schubert, A.; Jassoy, C. Cytotoxicity of medicinal plant species used by traditional healers in treating people suffering from HIV/AIDS in Uganda. Front. Toxicol. 2022 May 2;4:832780. [CrossRef]

- Kotloff, K.L.; Riddle, M.S.; Platts-Mills, J.A.; Pavlinac, P.; Zaidi, A.K.M. Shigellosis. The Lancet 2018, 391, 801-812.

- Lefèvre, S.; Njamkepo, E.; Feldman, S.; Ruckly, C.; Carle, I.; Lejay-Collin, M.; Fabre, L.; Yassine, I.; Frézal, L.; Pardos de la Gandara, M.; Fontanet, A.; Weill, F.X. Rapid emergence of extensively drug-resistant Shigella sonnei in France. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14 (1) 462. [CrossRef]

- Nur Syukriah, A.R.; Liza, M.S.; Harisun, Y.; Fadzillah, A.A.M. Effect of solvent extraction on antioxidant and antibacterial activities from Quercus infectoria (Manjakani). Int. Food Res. J. 2014, 21(3) 1067-1073.

- Tamokou, J.D.D.; Mbaveng, A.; Kuete, V. 2017. Antimicrobial activities of African medicinal spices and vegetables, in: Medicinal Spices and Vegetables from Africa: Therapeutic Potential Against Metabolic, Inflammatory, Infectious and Systemic Diseases. pp. 207-237. [CrossRef]

- Franklin Loic, T.T.; Boniface, P.K.; Vincent, N.; Zuriatou Y.T.; Victorine Lorette, Y.; Julius, N.N.; Paul, K.L.; Fabrice, F.B. Biological synthesis and characterization of silver-doped nanocomposites: Antibacterial and mechanistic studies. Drugs Drug Candidates 2024, 3, 13-32.

- Brice Rostan P.; Boniface, P.K.; Eutrophe Le Doux K.; Vincent N.; Yanick Kevin M.D.; Paul, K.L.; Fabrice, F.B. Extracts from Cardiospermum grandiflorum and Blighia welwitschii (Sapindaceae) reveal antibacterial activity against Shigella species. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2024, 164, 419-428.

- Van Bambeke, F.; Mingeot-Leclercq, M.-P.; Struelens, M.J.; Tulkens, P.M. The bacterial envelope as a target for novel anti-MRSA antibiotics. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2008, 29, 124-134. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Kim, H.; Halvorsen, T.M.; Buie, C.R. Leveraging microfluidic dielectrophoresis to distinguish compositional variations of lipopolysaccharide in E. coli (preprint). Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2023, 11, 991784. [CrossRef]

- Loh, B.; Grant, C.; Hancock, R.E. Use of the fluorescent probe 1-N-phenylnaphthylamine to study the interactions of aminoglycoside antibiotics with the outer membrane of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1984, 26, 546-551. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, J.Y.; Kim, M.K.; Mereuta, L.; Seo, C.H.; Luchian, T.; Park, Y. Mechanism of action of antimicrobial peptide P5 truncations against Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus. AMB Express. 2019, 9, 122. [CrossRef]

- Van Moll, L.; De Smet, J.; Paas, A.; Tegtmeier, D.; Vilcinskas, A.; Cos, P.; Van Campenhout, L. In vitro evaluation of antimicrobial peptides from the black soldier fly (Hermetia Illucens) against a selection of human pathogens. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e01664-21. [CrossRef]

- Qu, Y.; Locock, K.; Verma-Gaur, J.; Hay, I.D.; Meagher, L.; Traven, A. Searching for new strategies against polymicrobial biofilm infections: guanylated polymethacrylates kill mixed fungal/bacterial biofilms. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 71(2) 413-421. [CrossRef]

- Wolfmeier H, Pletzer D, Mansour SC, Hancock REW. New perspectives in biofilm eradication. ACS Infect. Dis. 2018, 4(2), 93-106. [CrossRef]

- Ogbole, O.O.; Segun, P.A.; Adeniji, A.J. In vitro cytotoxic activity of medicinal plants from Nigeria ethnomedicine on Rhabdomyosarcoma cancer cell line and HPLC analysis of active extracts. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2017, 17, 494. [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Vega, R.; Pérez-Gutiérrez, S.; Alarcón-Aguilar, F.; Almanza-Pérez, J.; Pérez-González, C.; González-Chávez, M.M. Phytochemical composition, anti-inflammatory and cytotoxic activities of chloroform extract of Senna crotalarioides Kunth. Am. J. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 887-900. [CrossRef]

- CLSI, 2012. CLSI Publishes 2012 Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing Standards - Medical Design and Outsourcing. https://www.medicaldesignandoutsourcing.com/clsi-publishes-2012-antimicrobial-susceptibility-testing-standards/ (accessed 6.7.23).

- Klepser, M.E.; Ernst, E.J.; Lewis, R.E.; Ernst, M.E.; Pfaller, M.A. Influence of test conditions on antifungal time-kill curve results: proposal for standardized methods. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998, 42, 1207-121. [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yao, H.; Zhao, X.; Ge, C. Biofilm formation and control of foodborne pathogenic bacteria. Molecules 2023, 28, 243. [CrossRef]

- Kalia, M.; Singh, D.; Sharma, D.; Narvi, S.; Agarwal, V. Senna alexandriana mill as a potential inhibitor for quorum sensing-controlled virulence factors and biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Phcog. Mag. 2020, 16, 80. [CrossRef]

- Bowling, T.; Mercer, L.; Don, R.; Jacobs, R.; Nare, B. Application of a resazurin-based high-throughput screening assay for the identification and progression of new treatments for human African trypanosomiasis. Int. J. Parasitol. Drugs Drug Resist. 2012, 2, 262-27. [CrossRef]

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).