Submitted:

02 January 2024

Posted:

03 January 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

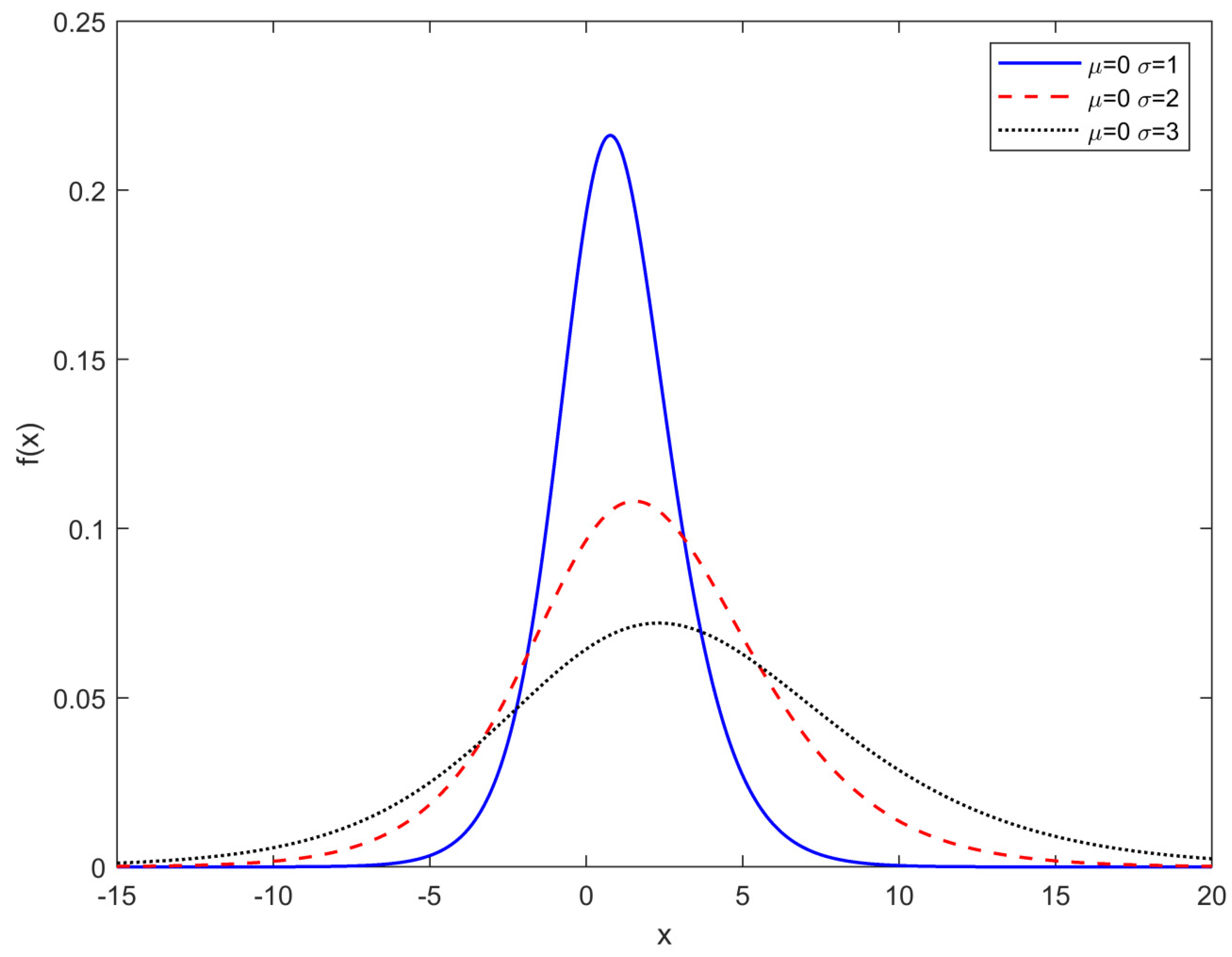

2.1. Two-Parameter Exponentially-Modified Logistic Distribution

2.2. Maximum Likelihood Estimation

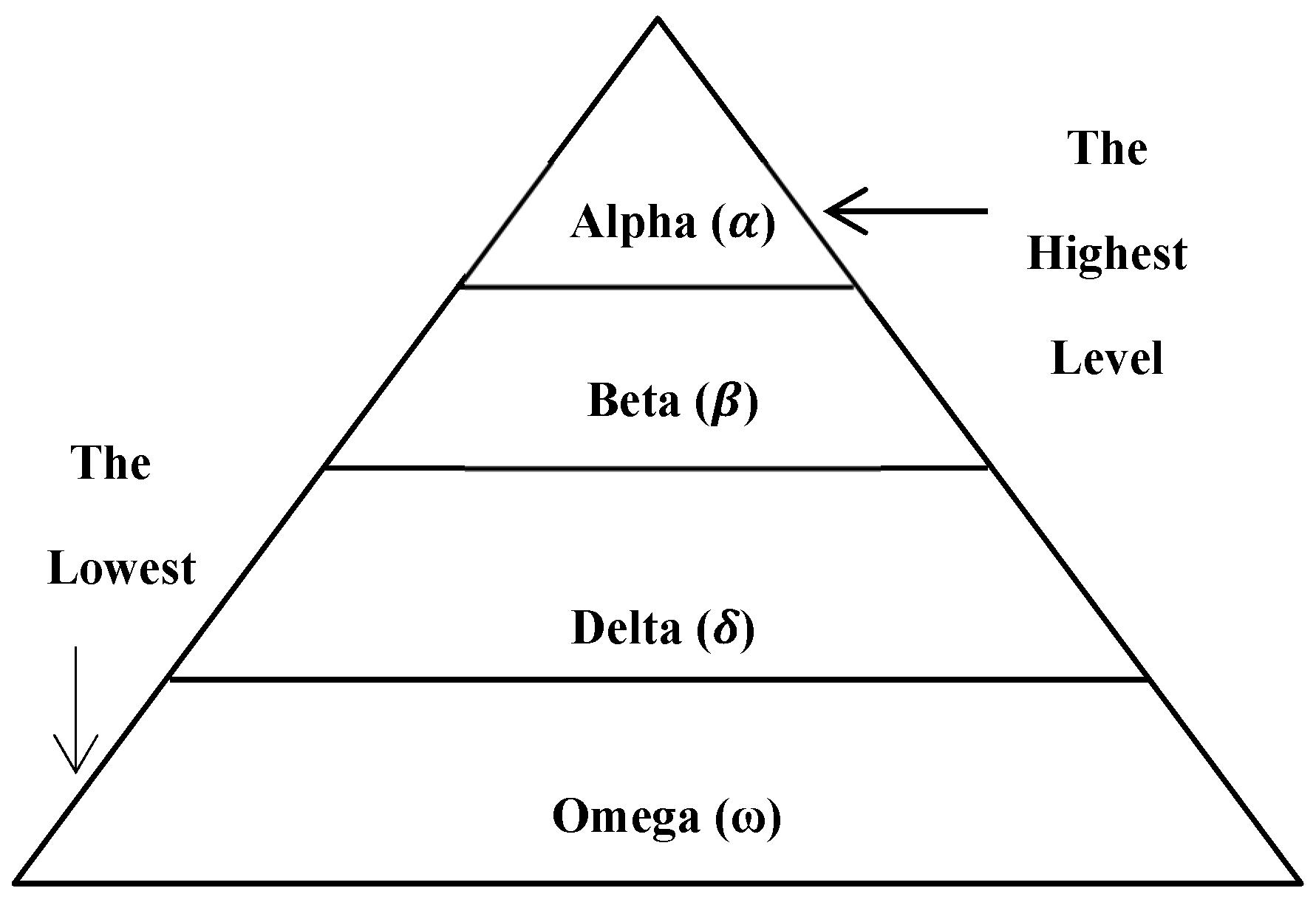

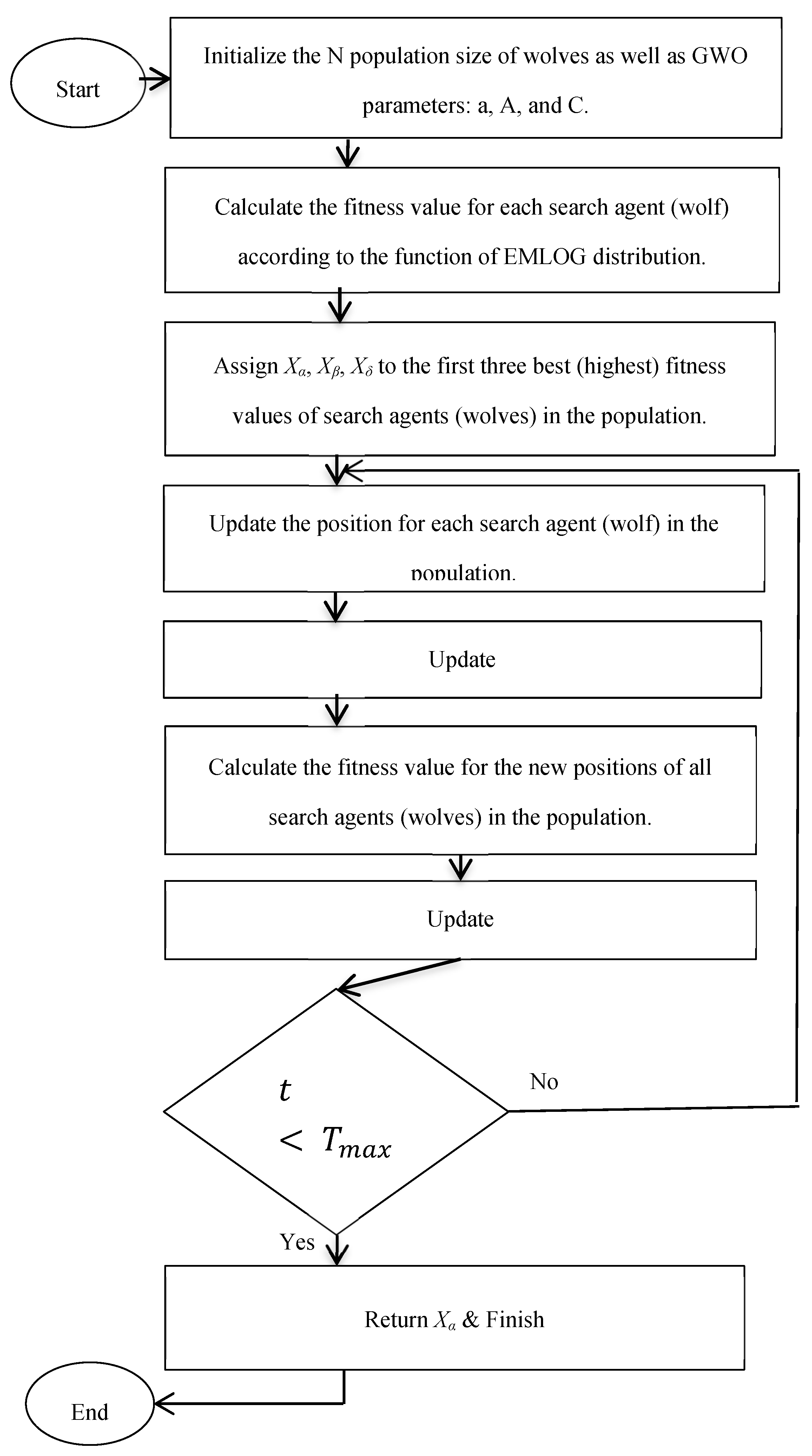

2.2.1. Grey Wolf Optimization (GWO)

- Control parameter (a), which is an important parameter that declines linearly for each iteration in the range [0,2] used in this algorithm. This parameter can indeed be determined using the formula:where the iteration in progress (current) and the entire number of iterations are denoted by t and Tmax, respectively.

- The coefficient vectors, A and C, can be found using the following formulas:where r1 and r2 are arbitrary vectors ranging from [0,1].

- Calculate the fitness value of each wolf type according to the fitness function, which is the same as the objective function represented by the ln L function in this study, and this fitness value refers to each wolf’s site in the pack. The highest value of the fitness function is considered the best position and assigned to the wolf of type alpha (α). The second and third highest fitness values are assigned to beta (β) and delta (δ) types of wolves, respectively. Steps 1 and 2 represent the searching phase of GWO.

- Update the position of each wolf in the pack surrounding the prey by calculating the distance between the current location (denoted by D) and the next location (denoted by) using the equations below.where is the current position vector at iteration t and Xp(t) is the best solution’s position vector (optimal) when iterating to the tth time. This step represents the phase of encircling behavior.

- Calculate the average value of the first three best solutions that refer to alpha (α), beta (β), and delta (δ) types of wolves because they have the best positions in the population. Besides that, they have the best knowledge of the prey’s potential location, which forces and obliges all the other wolves, including omega (ω), to change their current positions toward the best position, which has been determined by the following equations:whereand

- 4.

- Finally, go back to step 3 to continue iteration until the convergence is satisfied by reaching the stopping criterion and the needed number of maximum iterations to overall acquire the most appropriate (optimal) solution. The solution values are called the GWO estimates of the parameters.

2.2.2. Whale Optimization Algorithm (WOA)

- Initialize the position of the whale population randomly in the search space for the first iteration.

- Initiate the WOA parameters (a), A, and C, which are similar to GWO parameters previously calculated by Equations (11), (12), and (13), respectively, as well as other parameters such as parameter (b), which is a fixed value used to define the shape of the logarithmic spiral, and (l), a number drawn at random from the interval [–1,1]. Finally, the probability parameter (P) is set to 0.5 to give an equal chance of simulating both the shrinking surrounding and spiral approach movements of whales.

- Evaluate each whale’s fitness value in relation to the fitness function, which is considered the same as the objective function represented by the objective function ln L in this study. The best whale position in the initialized population is found and saved.

- If P < 0.5 and |A| < 1, the ongoing whale’s location is updated using the same Equations (14) and (15) as in GWO. Otherwise, if |A| > 1, one of the whales is chosen at random, and its position is updated using the following formulas:where Xrand is the position vector of any whale chosen at random from the current whale population.

- If P > 0.5, the current whale’s location is updated by the following formulas:where D’ refers to the path length between both the ith whale and the best solution (prey) currently available.

- Verify that no whale’s updated position exceeds the search space, then go back to step 4 to continue iterating until the number of repetitions required for convergence is achieved. The solution values are called the WOA parameter estimates.

2.2.3. Sine Cosine Algorithm

- Initialize the position of N numbers of the population solutions randomly within the search space for the first iteration as well as the random parameters r1, r2, r3, and r4 of this algorithm, which are incorporated to strike a balance between exploration and exploitation capabilities and thus to avoid settling for local optimums. The parameter r1 helps in determining whether an updated solution position or the movement direction of the next position is towards the best solution in the search space (r1 < 1) or outwards from it (r1 > 1). The r1 parameter falls linearly from a constant (a) to 0, as seen in the equation:

- 2.

- Evaluate the fitness value of each solution using using the fitness effect represented by the objective function in this study. Each fitness value refers to the position of each solution. The best (highest) value in the population is found and saved.

- 3.

- Update the main parameters, which are r1 by using Equation (23), and r2, r3, and r4 randomly.

- 4.

- Update the positions of all solution agents by utilizing the given equation:where denotes the position of the current solution in the ith dimension at the tth iteration and denotes the position of the target destination point in the dimension.

- 5.

- Loop back to step 2 to continue iterating until the maximum number of iterations is reached. The solution values are called the SCA parameter estimates.

2.2.3. Particle Swarm Optimization

- Initialize randomly the position and velocity of N number of population solutions (particles) for the first iteration as well as the algorithm parameters, which are c1, c2 representing acceleration coefficients, r1, r2 representing random numbers uniformly distributed among 0 and 1, and ω indicating the inertia weight parameter.

- Evaluate the fitness value of each solution (particle) by the fitness function ln L in this study. Each fitness value refers to the position of each solution. The best (highest) value of each particle in the population is found, compared with its previous historical movement, and then saved as a personal best solution (pbest) value. At the same time, the best value for fitness of each and every particle is found, compared with the previous historical global best, and saved as a (gbest) value.

- Update each solution’s position and velocity using the following equations:where represents particle i’s velocity at iteration t, is the location of particle i during iteration t, is the best position of a particle at iteration, and is the most optimal (best) location of the group at iteration t.

- Loop back to step 2 again until the convergence is satisfied. The solution values are called the PSO parameter estimates.

3. Results

4. Applications

4.1. Dataset 1: Tensile Tensile Strength of 69 Carbon Fibers

4.2. Dataset 2: Strengths of Glass Fibers.

4.3. Dataset 3: Bladder Cancer Patients.

4.4. Dataset 4: Waiting Times (in Minutes) of 100 Bank Customers.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Reyes J, Venegas O, Gómez H W (2018) Exponentially-modified logistic distribution with application to mining and nutrition data. Appl. Math. Inf. Sci. 12(6):1109-1116. [CrossRef]

- Hinde J (2011) Logistic Normal Distribution, in International Encyclopedia of Statistical Science (pp. 754-755). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. [CrossRef]

- Kissell R L, Poserina J (2017) Advanced Math and Statistics. In Optimal Sports Math, Statistics, and Fantasy, 1st edn. Elsevier, pp 103-135. [CrossRef]

- Gupta S S, Balakrishnan N (1992) Logistic order statistics and their properties. Handbook of the Logistic Distribution, 123.

- Gupta S S, & Gnanadesikan M (1966) Estimation of the parameters of the logistic distribution. Biometrika, 53(3-4): 565-570. [CrossRef]

- Gupta A K, Zeng W B, Yanhong Wu (2010) Exponential Distribution, in Probability and Statistical Models. Birkhäuser, Boston, MA pp 23-43. [CrossRef]

- Rasekhi M, Alizadeh M, Altun E, Hamedani G G, Afify A Z, Ahmad M (2017) THE MODIFIED Exponential Distribution With Applications. Pakistan Journal of Statistics, 33(5): 383-398.

- Aldahlan M A, Afify A Z (2020) The odd exponentiated half-logistic exponential distribution: estimation methods and application to engineering data. Mathematics, 8(10):1684. [CrossRef]

- Gómez Y M, Bolfarine H, Gómez H W (2014) A new extension of the exponential distribution. Revista Colombiana de Estadística, 37(1):25-34. [CrossRef]

- Hussein M, Elsayed H, Cordeiro G M (2022) A New Family of Continuous Distributions: Properties and Estimation. Symmetry, 14(2):276. [CrossRef]

- Gupta R D, Kundu D (2001) Exponentiated exponential family: an alternative to gamma and Weibull distributions. Biometrical Journal: Journal of Mathematical Methods in Biosciences, 43(1):117-130. [CrossRef]

- Pal M, Ali M M, Woo J (2006) Exponentiated weibull distribution. Statistica, 66(2):139-147. [CrossRef]

- Nadarajah S, Gupta A K (2007) The exponentiated gamma distribution with application to drought data. Calcutta Statistical Association Bulletin, 59(1-2):29-54. [CrossRef]

- Nadarajah S, Haghighi F (2011) An extension of the exponential distribution. Statistics, 45(6):543-558. [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary A K(1019) Frequentist Parameter Estimation of Two-Parameter Exponentiated Log-logistic Distribution BB. NCC Journal, 4(1):1-8. [CrossRef]

- Yuan K H, Schuster C, 18 Overview of Statistical Estimation Methods. The Oxford handbook of quantitative methods, 361. [CrossRef]

- Bartolucci F, Scrucca L (2010) Point Estimation Methods with Applications to Item Response Theory Models. [CrossRef]

- Pratihar D K (2012) Traditional vs non-traditional optimization tools. In: Basu K (ed) Computational Optimization and Applications, Narosa Publishing House Pvt. Ltd, New Delhi, pp 25-33.

- Sreenivas P, Kumar S V (2015) A review on non-traditional optimization algorithm for simultaneous scheduling problems. Journal of Mechanical and Civil Engineering, 12(2):50-53. [CrossRef]

- Hole, A. R., & Yoo, H. I. (2017). The use of heuristic optimization algorithms to facilitate maximum simulated likelihood estimation of random parameter logit models. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series C (Applied Statistics), 997-1013. [CrossRef]

- Özsoy, V. S., Ünsal, M. G., & Örkcü, H. H. (2020). Use of the heuristic optimization in the parameter estimation of generalized gamma distribution: comparison of GA, DE, PSO and SA methods. Computational Statistics, 35(4), 1895-1925. [CrossRef]

- Alrashidi, M., Rahman, S., & Pipattanasomporn, M. (2020). Metaheuristic optimization algorithms to estimate statistical distribution parameters for characterizing wind speeds. Renewable Energy, 149, 664-681. [CrossRef]

- Guedes, K. S., de Andrade, C. F., Rocha, P. A., Mangueira, R. D. S., & de Moura, E. P. (2020). Performance analysis of metaheuristic optimization algorithms in estimating the parameters of several wind speed distributions. Applied energy, 268, 114952. [CrossRef]

- YONAR, A., & PEHLİVAN, N. Y. (2021). Parameter estimation based on maximum likelihood estimation method for Weibull distribution using dragonfly algorithm. Mugla Journal of Science and Technology, 7(2), 84-90. [CrossRef]

- Kennedy J, Eberhart R (1995) Particle swarm optimization. in Proceedings of ICNN’95-international conference on neural networks. 4:1942-1948. IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili S, Mirjalili S M, Lewis A (2014) Grey wolf optimizer. Advances in engineering software, 69:46-61. [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili S, Lewis A (2016) The whale optimization algorithm. Advances in engineering software, 95:51-67. [CrossRef]

- Wang, F. K., & Huang, P. R. (2014). Implementing particle swarm optimization algorithm to estimate the mixture of two Weibull parameters with censored data. Journal of Statistical Computation and Simulation, 84(9), 1975-1989. [CrossRef]

- Okafor, E. G., EZUGWU, E., Jemitola, P. O., SUN, Y., & Lu, Z. (2018). Weibull parameter estimation using particle swarm optimization algorithm. International Journal of Engineering and Technology, 7, 3-32.

- Sancar, N., & Inan, D. (2021). A new alternative estimation method for Liu-type logistic estimator via particle swarm optimization: an application to data of collapse of Turkish commercial banks during the Asian financial crisis. Journal of Applied Statistics, 48(13-15), 2499-2514. [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, S. W., & Algamal, Z. Y. (2021). Reliability Estimation of Three Parameters Gamma Distribution via Particle Swarm Optimization. Thailand Statistician, 19(2), 308-316.

- Abdullah, Z. M., Hussain, N. K., Fawzi, F. A., Abdal-Hammed, M. K., & Khaleel, M. A. (2022). Estimating parameters of Marshall Olkin Topp Leon exponential distribution via grey wolf optimization and conjugate gradient with application. International Journal of Nonlinear Analysis and Applications, 13(1), 3491-3503. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J., Huang, X., Li, Q., & Ma, X. (2018). Comparison of seven methods for determining the optimal statistical distribution parameters: A case study of wind energy assessment in the large-scale wind farms of China. Energy, 164, 432-448. [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, W. A. D. I. (2021). Five different distributions and metaheuristics to model wind speed distribution. Journal of Thermal Engineering, 7(Supp 14), 1898-1920. [CrossRef]

- Wadi, M., & Elmasry, W. (2023). A comparative assessment of five different distributions based on five different optimization methods for modeling wind speed distribution. Gazi University Journal of Science. [CrossRef]

- Al-Mhairat, B., & Al-Quraan, A. (2022). Assessment of wind energy resources in jordan using different optimization techniques. Processes, 10(1), 105. [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili S (2016) SCA: a sine cosine algorithm for solving optimization problems. Knowledge-based systems, 96: 120-133. [CrossRef]

- Turgut, M. S., Sağban, H. M., Turgut, O. E., & Özmen, Ö. T. (2021). Whale optimization and sine–cosine optimization algorithms with cellular topology for parameter identification of chaotic systems and Schottky barrier diode models. Soft Computing, 25(2), 1365-1409. [CrossRef]

- Altintasi, C. (2021). Sine Cosine Algorithm Approaches for Directly Estimation of Power System Harmonics & Interharmonics Parameters. IEEE Access, 9, 73169-73181. [CrossRef]

- Montoya, O. D., Gil-González, W., & Grisales-Noreña, L. F. (2020, October). Sine-cosine algorithm for parameters’ estimation in solar cells using datasheet information. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series (Vol. 1671, No. 1, p. 012008). IOP Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Faris H, Aljarah I, Al-Betar M A, Mirjalili S (2018) Grey wolf optimizer: a review of recent variants and applications. Neural computing and applications, 30(2):413-435. [CrossRef]

- Gupta S, Deep K (2019) A novel random walk grey wolf optimizer. Swarm and evolutionary computation, 44:101-112. [CrossRef]

- Joshi H, Arora S (2017) Enhanced grey wolf optimization algorithm for global optimization. Fundamenta Informaticae, 153(3):235-264. [CrossRef]

- Kraiem H, Aymen F, Yahya L, Triviño A, Alharthi M, Ghoneim S S (2021) A comparison between particle swarm and grey wolf optimization algorithms for improving the battery autonomy in a photovoltaic system. Applied Sciences, 11(16):7732. [CrossRef]

- KARAKOYUN M, Onur I, İhtisam A (2019) Grey Wolf Optimizer (GWO) Algorithm to Solve the Partitional Clustering Problem. International Journal of Intelligent Systems and Applications in Engineering, 7(4): 201-206. [CrossRef]

- Salam M A, Ali M (2020) Optimizing Extreme Learning Machine using GWO Algorithm for Sentiment Analysis. International Journal of Computer Applications, 975:8887. [CrossRef]

- Rana N, Latiff M S A, Abdulhamid S M, Chiroma H (2020), Whale optimization algorithm: a systematic review of contemporary applications, modifications and developments. Neural Computing and Applications, 32(20):16245-16277. [CrossRef]

- Hu H, Bai Y, Xu T (2016) A whale optimization algorithm with inertia weight. WSEAS Trans. Comput, 15:319-326.

- Yan Z, Wang S, Liu B, Li X (2018) Application of whale optimization algorithm in optimal allocation of water resources. in E3S Web of Conferences (Vol. 53, p. 04019). EDP Sciences. [CrossRef]

- Abualigah L, Diabat A (2021) Advances in sine cosine algorithm: a comprehensive survey. 54(4):2567-2608. [CrossRef]

- Suid M H, Ahmad M A, Ismail M R T R, Ghazali M R, Irawan A, Tumari M Z, (2018) An improved sine cosine algorithm for solving optimization problems. In 2018 IEEE Conference on Systems, Process and Control (ICSPC): 209-213.IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Rizk-Allah, R M, Mageed H A, El-Sehiemy R A, Aleem S H E A, El Shahat A (2017) A new sine cosine optimization algorithm for solving combined non-convex economic and emission power dispatch problems. Int J Energy Convers, 5(6):180-192. [CrossRef]

- Gabis A B, Meraihi Y, Mirjalili S, Ramdane-Cherif A (2021) A comprehensive survey of sine cosine algorithm: variants and applications. Artificial Intelligence Review, 54(7):5469-5540. [CrossRef]

- Júnior S F A X, Xavier É F M, da Silva Jale J, de Oliveira T A, Sabino A L C (2020). An application of Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) algorithm with daily precipitation data in Campina Grande, Paraíba, Brazil. Research, Society and Development, 9(8): e444985841-e444985841. [CrossRef]

- El-Shorbagy M A, Hassanien A E (2018) Particle swarm optimization from theory to applications. International Journal of Rough Sets and Data Analysis (IJRSDA), 5(2):1-24. [CrossRef]

- Ren C, An N, Wang J, Li L, Hu B, Shang D (2014) Optimal parameters selection for BP neural network based on particle swarm optimization: A case study of wind speed forecasting. Knowledge-based systems, 56:226-239. [CrossRef]

- Ab Talib M H, Mat Darus I Z (2017) Intelligent fuzzy logic with firefly algorithm and particle swarm optimization for semi-active suspension system using magneto-rheological damper. Journal of Vibration and Control, 23(3): 501-514. [CrossRef]

- Anderson D R, Burnham K P, White G C (1998) Comparison of Akaike information criterion and consistent Akaike information criterion for model selection and statistical inference from capture-recapture studies. Journal of Applied Statistics, 25(2):263-282. [CrossRef]

- Neath A A, Cavanaugh J E (2012) The Bayesian information criterion: background, derivation, and applications. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Statistics, 4(2):199-203. [CrossRef]

- Ayalew S, Babu M C, Rao L M (2012) Comparison of new approach criteria for estimating the order of autoregressive process. IOSR Journall of Mathematics, 1(3):10-20. [CrossRef]

- Ijaz M, Mashwani W K, Belhaouari S B (2020) A novel family of lifetime distribution with applications to real and simulated data. Plos one, 15(10):e0238746. [CrossRef]

- Bader M G, Priest A M (1982) Statistical aspects of fibre and bundle strength in hybrid composites. Progress in science and engineering of composites, 1129-1136.

- Alakuş K, Erilli N A (2019) Point and Confidence Interval Estimation of the Parameter and Survival Function for Lindley Distribution Under Censored and Uncensored Data. Türkiye Klinikleri Biyoistatistik, 11(3):198-212. [CrossRef]

- Smith R L, Naylor J (1987) A comparison of maximum likelihood and Bayesian estimators for the three-parameter Weibull distribution. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series C (Applied Statistics), 36(3):358-369. [CrossRef]

- Lee E T, Wang J (2003) Statistical methods for survival data analysis.

- Sen S, Afify A Z, Al-Mofleh H, Ahsanullah, M (2019) The quasi xgamma-geometric distribution with application in medicine. Filomat, 33(16):5291-5330. [CrossRef]

- Kumar C S, Nair S R (2021) A generalization to the log-inverse Weibull distribution and its applications in cancer research. Journal of Statistical Distributions and Applications, 8(1):1-30. [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz M C, Yousof H M, Rasekhi M, Hamedani G G (2018) The odd Lindley Burr XII model: Bayesian analysis, classical inference and characterizations. Journal of Data Science, 16(2):327-353. [CrossRef]

- Irshad M R, Chesneau C, Nitin S L, Shibu D S, Maya R (2021) The Generalized DUS Transformed Log-Normal Distribution and Its Applications to Cancer and Heart Transplant Datasets. Mathematics, 9(23):3113. [CrossRef]

- Bhati D, Malik M, Jose K K (2016) A new 3-parameter extension of generalized lindley distribution. arXiv preprint arXiv:1601.01045. [CrossRef]

- Cordeiro G M, Afify A Z, Yousof H M, Pescim R R, Aryal G R (2017) The exponentiated Weibull-H family of distributions: Theory and Applications. Mediterranean Journal of Mathematics, 14(4):1-22. [CrossRef]

- Shukla K K (2019) A comparative study of one parameter lifetime distributions. Biometrics & Biostatistics International Journal, 8(4):111-123. [CrossRef]

- Ghitany M E, Atieh B, Nadarajah S (2008) Lindley distribution and its application. Mathematics and computers in simulation, 78(4):493-506. [CrossRef]

|

Method |

Mean | Variance | Bias | MSE | Mean | Variance | Bias | MSE | Def | |||||||||

| 30 | GWO | 0.0153 | 0.1463 | 0.0153 | 0.1465 | 0.9909 | 0.0219 | -0.0091 | 0.022 | 0.1685 | ||||||||

| WOA | 0.0155 | 0.1463 | 0.0155 | 0.1465 | 0.9908 | 0.0219 | -0.0092 | 0.022 | 0.1685 | |||||||||

| SCA | 0.9941 | 18.7710 | 0.9941 | 19.7592 | 0.9435 | 0.0633 | -0.0565 | 0.0665 | 19.8257 | |||||||||

| PSO | -0.0541 | 0.2880 | -0.0541 | 0.2909 | 1.0376 | 0.0820 | 0.0376 | 0.0834 | 0.3743 | |||||||||

| 50 | GWO | 0.0198 | 0.0832 | 0.0198 | 0.0836 | 0.9817 | 0.0127 | -0.0183 | 0.0130 | 0.0966 | ||||||||

| WOA | 0.0393 | 0.4822 | 0.0393 | 0.4837 | 0.9811 | 0.0133 | -0.0189 | 0.0137 | 0.4974 | |||||||||

| SCA | 0.7148 | 13.6000 | 0.7148 | 14.1109 | 0.9482 | 0.0433 | -0.0518 | 0.0460 | 14.1569 | |||||||||

| PSO | -0.0639 | 0.2861 | -0.0639 | 0.2902 | 1.0287 | 0.0762 | 0.0287 | 0.0770 | 0.3672 | |||||||||

| 100 | GWO | 0.0061 | 0.0409 | 0.0061 | 0.0409 | 0.9907 | 0.0068 | -0.0093 | 0.0069 | 0.0478 | ||||||||

| WOA | 0.0061 | 0.0409 | 0.0061 | 0.0409 | 0.9907 | 0.0068 | -0.0094 | 0.0069 | 0.0478 | |||||||||

| SCA | 0.8865 | 16.8700 | 0.8865 | 17.6559 | 0.9494 | 0.0445 | -0.0506 | 0.0471 | 17.7029 | |||||||||

| PSO | -0.0695 | 0.1923 | -0.0695 | 0.1971 | 1.0330 | 0.0615 | 0.0330 | 0.0626 | 0.2597 | |||||||||

| 150 | GWO | 0.0069 | 0.0278 | 0.0069 | 0.0278 | 0.9965 | 0.0044 | -0.0035 | 0.0044 | 0.0323 | ||||||||

| WOA | 0.0266 | 0.4275 | 0.0266 | 0.4282 | 0.9955 | 0.0054 | -0.0045 | 0.0054 | 0.4336 | |||||||||

| SCA | 0.7053 | 13.5430 | 0.7053 | 14.0404 | 0.9640 | 0.0350 | -0.0361 | 0.0363 | 14.0768 | |||||||||

| PSO | -0.0784 | 0.2568 | -0.0784 | 0.2629 | 1.0491 | 0.0815 | 0.0491 | 0.0839 | 0.3469 | |||||||||

| 200 | GWO | 0.0078 | 0.0211 | 0.0078 | 0.0212 | 0.9947 | 0.0035 | -0.0053 | 0.0035 | 0.0247 | ||||||||

| WOA | 0.0277 | 0.4208 | 0.0277 | 0.4216 | 0.9938 | 0.0043 | -0.0062 | 0.0043 | 0.4259 | |||||||||

| SCA | 0.7057 | 13.5360 | 0.7057 | 14.0340 | 0.9611 | 0.0341 | -0.0389 | 0.0356 | 14.0696 | |||||||||

| PSO | -0.0618 | 0.1450 | -0.0618 | 0.1488 | 1.0446 | 0.0656 | 0.0446 | 0.0676 | 0.2164 | |||||||||

| 30 | GWO | 0.0358 | 0.5668 | 0.0358 | 0.5681 | 1.955 | 0.0867 | -0.045 | 0.0887 | 0.6568 | ||||||||

| WOA | 0.0359 | 0.5670 | 0.0359 | 0.5683 | 1.955 | 0.0867 | -0.045 | 0.0887 | 0.6570 | |||||||||

| SCA | 0.6339 | 12.1620 | 0.6339 | 12.5638 | 1.9009 | 0.1909 | -0.0991 | 0.2007 | 12.7646 | |||||||||

| PSO | 0.0281 | 0.6443 | 0.0281 | 0.6451 | 1.9737 | 0.1036 | -0.0263 | 0.1043 | 0.7494 | |||||||||

| 50 | GWO | 0.0150 | 0.3327 | 0.0150 | 0.3329 | 1.9736 | 0.0533 | -0.0264 | 0.0540 | 0.3869 | ||||||||

| WOA | 0.0150 | 0.3327 | 0.0150 | 0.3329 | 1.9736 | 0.0533 | -0.0264 | 0.0540 | 0.3869 | |||||||||

| SCA | 0.4812 | 9.7752 | 0.4812 | 10.0068 | 1.9277 | 0.1431 | -0.0723 | 0.1483 | 10.1551 | |||||||||

| PSO | -0.0120 | 0.3795 | -0.0120 | 0.3796 | 1.9891 | 0.0623 | -0.0109 | 0.0624 | 0.4421 | |||||||||

| 100 | GWO | 0.0028 | 0.1794 | 0.0028 | 0.1794 | 1.9870 | 0.0266 | -0.0130 | 0.0268 | 0.2062 | ||||||||

| WOA | 0.0029 | 0.1795 | 0.0029 | 0.1795 | 1.9870 | 0.0266 | -0.0130 | 0.0268 | 0.2063 | |||||||||

| SCA | 0.3899 | 8.1199 | 0.3899 | 8.2719 | 1.9473 | 0.1040 | -0.0527 | 0.1068 | 8.3787 | |||||||||

| PSO | -0.0201 | 0.2167 | -0.0201 | 0.2171 | 1.9981 | 0.0343 | -0.0019 | 0.0343 | 0.2514 | |||||||||

| 150 | GWO | -0.0013 | 0.1119 | -0.0013 | 0.1119 | 1.9871 | 0.0164 | -0.0129 | 0.0166 | 0.1285 | ||||||||

| WOA | -0.0011 | 0.1120 | -0.0011 | 0.1120 | 1.9871 | 0.0164 | -0.0129 | 0.0166 | 0.1286 | |||||||||

| SCA | 0.2604 | 5.2478 | 0.2604 | 5.3156 | 1.9615 | 0.0645 | -0.0385 | 0.0660 | 5.3816 | |||||||||

| PSO | -0.0194 | 0.1379 | -0.0194 | 0.1383 | 2.0054 | 0.0344 | 0.0054 | 0.0344 | 0.1727 | |||||||||

| 200 | GWO | 0.0088 | 0.0848 | 0.0088 | 0.0849 | 1.9855 | 0.0136 | -0.0145 | 0.0138 | 0.0987 | ||||||||

| WOA | 0.0089 | 0.0848 | 0.0089 | 0.0849 | 1.9855 | 0.0136 | -0.0145 | 0.0138 | 0.0987 | |||||||||

| SCA | 0.1885 | 3.6525 | 0.1885 | 3.6880 | 1.9687 | 0.0470 | -0.0313 | 0.0480 | 3.7360 | |||||||||

| PSO | -0.0024 | 0.0988 | -0.0024 | 0.0988 | 1.9959 | 0.0238 | -0.0041 | 0.0238 | 0.1226 | |||||||||

|

Method |

Mean | Variance | Bias | MSE | Mean | Variance | Bias | MSE | Def | |||||||||||

| 30 | GWO | 1.0289 | 0.1366 | 0.0289 | 0.1374 | 0.9768 | 0.0218 | -0.0232 | 0.0223 | 0.1598 | ||||||||||

| WOA | 1.0477 | 0.4966 | 0.0477 | 0.4989 | 0.9760 | 0.0226 | -0.0240 | 0.0232 | 0.5221 | |||||||||||

| SCA | 2.0237 | 17.8320 | 1.0237 | 18.8800 | 0.9270 | 0.0652 | -0.0730 | 0.0705 | 18.9505 | |||||||||||

| PSO | 0.9325 | 0.3457 | -0.0675 | 0.3503 | 1.0387 | 0.1069 | 0.0387 | 0.1084 | 0.4587 | |||||||||||

| 50 | GWO | 1.0100 | 0.0913 | 0.0100 | 0.0914 | 1.0002 | 0.0132 | 0.0002 | 0.0132 | 0.1046 | ||||||||||

| WOA | 1.0680 | 1.1704 | 0.0680 | 1.1750 | 0.9976 | 0.0158 | -0.0024 | 0.0158 | 1.1908 | |||||||||||

| SCA | 2.2017 | 21.4220 | 1.2017 | 22.8661 | 0.9408 | 0.0688 | -0.0592 | 0.0723 | 22.9384 | |||||||||||

| PSO | 0.9635 | 0.1723 | -0.0365 | 0.1736 | 1.0285 | 0.0419 | 0.0285 | 0.0427 | 0.2163 | |||||||||||

| 100 | GWO | 1.0103 | 0.0401 | 0.0103 | 0.0402 | 0.9926 | 0.0070 | -0.0074 | 0.0071 | 0.0473 | ||||||||||

| WOA | 1.0292 | 0.4007 | 0.0292 | 0.4016 | 0.9915 | 0.0079 | -0.0085 | 0.0080 | 0.4095 | |||||||||||

| SCA | 2.0745 | 19.1190 | 1.0745 | 20.2736 | 0.9394 | 0.0546 | -0.0606 | 0.0583 | 20.3318 | |||||||||||

| PSO | 0.9286 | 0.2145 | -0.0714 | 0.2196 | 1.0408 | 0.0784 | 0.0408 | 0.0801 | 0.2997 | |||||||||||

| 150 | GWO | 1.0035 | 0.0277 | 0.0035 | 0.0277 | 0.9988 | 0.0040 | -0.0012 | 0.0040 | 0.0317 | ||||||||||

| WOA | 1.0037 | 0.0277 | 0.0037 | 0.0277 | 0.9987 | 0.0040 | -0.0013 | 0.0040 | 0.0317 | |||||||||||

| SCA | 1.7817 | 14.2310 | 0.7818 | 14.8422 | 0.9598 | 0.0400 | -0.0402 | 0.0416 | 14.8838 | |||||||||||

| PSO | 0.9331 | 0.2009 | -0.0669 | 0.2054 | 1.0434 | 0.0665 | 0.0434 | 0.0684 | 0.2738 | |||||||||||

| 200 | GWO | 1.0038 | 0.0222 | 0.0038 | 0.0222 | 0.9971 | 0.0033 | -0.0029 | 0.0033 | 0.0255 | ||||||||||

| WOA | 1.0226 | 0.3830 | 0.0226 | 0.3835 | 0.9966 | 0.0037 | -0.0034 | 0.0037 | 0.3872 | |||||||||||

| SCA | 1.8953 | 16.2030 | 0.8953 | 17.0046 | 0.9519 | 0.0445 | -0.0481 | 0.0468 | 17.0514 | |||||||||||

| PSO | 0.9356 | 0.1518 | -0.0644 | 0.1559 | 1.0407 | 0.0550 | 0.0407 | 0.0567 | 0.2126 | |||||||||||

| 30 | GWO | 1.0427 | 0.5660 | 0.0427 | 0.5678 | 1.9587 | 0.0905 | -0.0413 | 0.0922 | 0.6600 | ||||||||||

| WOA | 1.0611 | 0.9251 | 0.0611 | 0.9288 | 1.9566 | 0.0938 | -0.0434 | 0.0957 | 1.0245 | |||||||||||

| SCA | 1.7568 | 13.7140 | 0.7569 | 14.2869 | 1.8889 | 0.2220 | -0.1111 | 0.2343 | 14.5212 | |||||||||||

| PSO | 1.0185 | 0.6051 | 0.0185 | 0.6054 | 1.9751 | 0.1007 | -0.0249 | 0.1013 | 0.7068 | |||||||||||

| 50 | GWO | 1.0120 | 0.3241 | 0.0120 | 0.3242 | 1.9685 | 0.0504 | -0.0315 | 0.0514 | 0.3756 | ||||||||||

| WOA | 1.0121 | 0.3242 | 0.0121 | 0.3243 | 1.9685 | 0.0504 | -0.0315 | 0.0514 | 0.3757 | |||||||||||

| SCA | 1.4822 | 9.1786 | 0.4822 | 9.4111 | 1.9197 | 0.1437 | -0.0803 | 0.1501 | 9.5613 | |||||||||||

| PSO | 0.9932 | 0.3727 | -0.0068 | 0.3727 | 1.9882 | 0.0671 | -0.0118 | 0.0672 | 0.4400 | |||||||||||

| 100 | GWO | 0.9993 | 0.1657 | -0.0007 | 0.1657 | 1.9815 | 0.0271 | -0.0185 | 0.0274 | 0.1931 | ||||||||||

| WOA | 0.9989 | 0.1658 | -0.0011 | 0.1658 | 1.9815 | 0.0271 | -0.0185 | 0.0274 | 0.1932 | |||||||||||

| SCA | 1.3018 | 5.8544 | 0.3018 | 5.9455 | 1.9517 | 0.0862 | -0.0483 | 0.0885 | 6.0340 | |||||||||||

| PSO | 0.9628 | 0.2391 | -0.0372 | 0.2405 | 2.0028 | 0.0449 | 0.0028 | 0.0449 | 0.2854 | |||||||||||

| 150 | GWO | 1.0100 | 0.1128 | 0.0100 | 0.1129 | 1.9831 | 0.0173 | -0.0169 | 0.0176 | 0.1305 | ||||||||||

| WOA | 1.0291 | 0.4732 | 0.0291 | 0.4740 | 1.9812 | 0.0210 | -0.0188 | 0.0214 | 0.4954 | |||||||||||

| SCA | 1.1800 | 3.3322 | 0.1800 | 3.3646 | 1.9667 | 0.0506 | -0.0333 | 0.0517 | 3.4163 | |||||||||||

| PSO | 0.9913 | 0.1655 | -0.0087 | 0.1656 | 2.0034 | 0.0369 | 0.0034 | 0.0369 | 0.2025 | |||||||||||

| 200 | GWO | 1.0204 | 0.0907 | 0.0204 | 0.0911 | 1.9788 | 0.0120 | -0.0212 | 0.0124 | 0.1036 | ||||||||||

| WOA | 1.0200 | 0.0909 | 0.0200 | 0.0913 | 1.9788 | 0.0120 | -0.0212 | 0.0124 | 0.1037 | |||||||||||

| SCA | 1.2482 | 4.3658 | 0.2483 | 4.4275 | 1.9562 | 0.0565 | -0.0438 | 0.0584 | 4.4859 | |||||||||||

| PSO | 0.9955 | 0.1422 | -0.0045 | 0.1422 | 1.9972 | 0.0294 | -0.0028 | 0.0294 | 0.1716 | |||||||||||

|

Method |

Mean | Variance | Bias | MSE | Mean | Variance | Bias | MSE | Def | |||||||||||

| 30 | GWO | 2.0404 | 0.1378 | 0.0404 | 0.1394 | 0.9720 | 0.0211 | -0.0280 | 0.0219 | 0.1613 | ||||||||||

| WOA | 2.0409 | 0.1378 | 0.0409 | 0.1395 | 0.9719 | 0.0211 | -0.0281 | 0.0219 | 0.1614 | |||||||||||

| SCA | 3.3470 | 21.9970 | 1.3470 | 23.8114 | 0.9044 | 0.0802 | -0.0956 | 0.0893 | 23.9007 | |||||||||||

| PSO | 1.9795 | 0.2660 | -0.0205 | 0.2664 | 1.0245 | 0.1029 | 0.0245 | 0.1035 | 0.3699 | |||||||||||

| 50 | GWO | 2.0138 | 0.0865 | 0.0138 | 0.0867 | 0.9834 | 0.0127 | -0.0166 | 0.0130 | 0.0997 | ||||||||||

| WOA | 2.0311 | 0.4098 | 0.0311 | 0.4108 | 0.9830 | 0.0134 | -0.0171 | 0.0137 | 0.4245 | |||||||||||

| SCA | 3.3727 | 22.9320 | 1.3727 | 24.8163 | 0.9096 | 0.0756 | -0.0904 | 0.0838 | 24.9001 | |||||||||||

| PSO | 1.9425 | 0.2365 | -0.0575 | 0.2398 | 1.0414 | 0.1003 | 0.0414 | 0.1020 | 0.3418 | |||||||||||

| 100 | GWO | 2.0158 | 0.0455 | 0.0158 | 0.0457 | 0.9961 | 0.0069 | -0.0039 | 0.0069 | 0.0527 | ||||||||||

| WOA | 2.0161 | 0.0455 | 0.0161 | 0.0458 | 0.9960 | 0.0069 | -0.0040 | 0.0069 | 0.0527 | |||||||||||

| SCA | 3.1106 | 18.5920 | 1.1106 | 19.8254 | 0.9389 | 0.0594 | -0.0611 | 0.0631 | 19.8886 | |||||||||||

| PSO | 1.9336 | 0.2321 | -0.0664 | 0.2365 | 1.0511 | 0.0886 | 0.0511 | 0.0912 | 0.3277 | |||||||||||

| 150 | GWO | 1.9984 | 0.0264 | -0.0016 | 0.0264 | 0.9940 | 0.0043 | -0.0060 | 0.0043 | 0.0307 | ||||||||||

| WOA | 1.9982 | 0.0264 | -0.0018 | 0.0264 | 0.9939 | 0.0043 | -0.0061 | 0.0043 | 0.0307 | |||||||||||

| SCA | 2.8450 | 14.5540 | 0.8450 | 15.2680 | 0.9485 | 0.0451 | -0.0515 | 0.0478 | 15.3158 | |||||||||||

| PSO | 1.9311 | 0.1683 | -0.0689 | 0.1730 | 1.0391 | 0.0699 | 0.0391 | 0.0714 | 0.2445 | |||||||||||

| 200 | GWO | 2.0016 | 0.0207 | 0.0016 | 0.0207 | 1.0001 | 0.0033 | 0.0001 | 0.0033 | 0.0240 | ||||||||||

| WOA | 2.0019 | 0.0207 | 0.0019 | 0.0207 | 1.0002 | 0.0033 | 0.0002 | 0.0033 | 0.0240 | |||||||||||

| SCA | 2.7336 | 12.8290 | 0.7336 | 13.3672 | 0.9601 | 0.0408 | -0.0399 | 0.0424 | 13.4096 | |||||||||||

| PSO | 1.9299 | 0.2492 | -0.0701 | 0.2541 | 1.0501 | 0.0766 | 0.0501 | 0.0791 | 0.3332 | |||||||||||

| 30 | GWO | 2.0178 | 0.5961 | 0.0178 | 0.5964 | 1.9516 | 0.0887 | -0.0484 | 0.0910 | 0.6875 | ||||||||||

| WOA | 2.0175 | 0.5962 | 0.0175 | 0.5965 | 1.9516 | 0.0887 | -0.0484 | 0.0910 | 0.6875 | |||||||||||

| SCA | 2.6082 | 10.9120 | 0.6082 | 11.2819 | 1.8901 | 0.2033 | -0.1100 | 0.2154 | 11.4973 | |||||||||||

| PSO | 1.9918 | 0.6671 | -0.0082 | 0.6672 | 1.9734 | 0.1048 | -0.0266 | 0.1055 | 0.7727 | |||||||||||

| 50 | GWO | 1.9974 | 0.3451 | -0.0026 | 0.3451 | 1.9631 | 0.0523 | -0.0369 | 0.0537 | 0.3988 | ||||||||||

| WOA | 1.9971 | 0.3451 | -0.0029 | 0.3451 | 1.9630 | 0.0523 | -0.0370 | 0.0537 | 0.3988 | |||||||||||

| SCA | 2.5401 | 9.7643 | 0.5401 | 10.0560 | 1.9078 | 0.1589 | -0.0922 | 0.1674 | 10.2234 | |||||||||||

| PSO | 1.9639 | 0.4095 | -0.0361 | 0.4108 | 1.9886 | 0.0764 | -0.0114 | 0.0765 | 0.4873 | |||||||||||

| 100 | GWO | 2.0392 | 0.1603 | 0.0392 | 0.1618 | 1.9707 | 0.0239 | -0.0293 | 0.0248 | 0.1866 | ||||||||||

| WOA | 2.0395 | 0.1603 | 0.0395 | 0.1619 | 1.9707 | 0.0239 | -0.0293 | 0.0248 | 0.1866 | |||||||||||

| SCA | 2.1851 | 2.7227 | 0.1851 | 2.7570 | 1.9555 | 0.0534 | -0.0445 | 0.0554 | 2.8123 | |||||||||||

| PSO | 2.0046 | 0.2233 | 0.0046 | 0.2233 | 1.9917 | 0.0425 | -0.0083 | 0.0426 | 0.2659 | |||||||||||

| 150 | GWO | 1.9935 | 0.1175 | -0.0065 | 0.1175 | 1.9745 | 0.0178 | -0.0255 | 0.0185 | 0.1360 | ||||||||||

| WOA | 1.9938 | 0.1176 | -0.0062 | 0.1176 | 1.9744 | 0.0178 | -0.0256 | 0.0185 | 0.1361 | |||||||||||

| SCA | 2.0829 | 1.7308 | 0.0829 | 1.7377 | 1.9658 | 0.0364 | -0.0342 | 0.0376 | 1.7752 | |||||||||||

| PSO | 1.9712 | 0.1582 | -0.0288 | 0.1590 | 1.9931 | 0.0329 | -0.0069 | 0.0329 | 0.1920 | |||||||||||

| 200 | GWO | 1.9927 | 0.0850 | -0.0073 | 0.0851 | 1.9859 | 0.0130 | -0.0141 | 0.0132 | 0.0983 | ||||||||||

| WOA | 2.0103 | 0.4093 | 0.0103 | 0.4094 | 1.9841 | 0.0168 | -0.0159 | 0.0171 | 0.4265 | |||||||||||

| SCA | 2.1341 | 2.6630 | 0.1341 | 2.6810 | 1.9716 | 0.0429 | -0.0284 | 0.0437 | 2.7247 | |||||||||||

| PSO | 1.9731 | 0.1099 | -0.0269 | 0.1106 | 1.9989 | 0.0230 | -0.0011 | 0.0230 | 0.1336 | |||||||||||

|

Method |

Mean | Variance | Bias | MSE | Mean | Variance | Bias | MSE | Def | ||||||||||

| 30 | GWO | 3.0124 | 0.1393 | 0.0124 | 0.1395 | 0.9817 | 0.0219 | -0.0183 | 0.0222 | 0.1617 | |||||||||

| WOA | 3.0286 | 0.4277 | 0.0286 | 0.4285 | 0.9812 | 0.0227 | -0.0188 | 0.0231 | 0.4516 | ||||||||||

| SCA | 4.4228 | 22.4900 | 1.4228 | 24.5144 | 0.9025 | 0.0906 | -0.0976 | 0.1001 | 24.6145 | ||||||||||

| PSO | 2.9348 | 0.2984 | -0.0652 | 0.3027 | 1.0295 | 0.0889 | 0.0295 | 0.0898 | 0.3924 | ||||||||||

| 50 | GWO | 3.0151 | 0.0839 | 0.0151 | 0.0841 | 0.9933 | 0.0135 | -0.0067 | 0.0135 | 0.0977 | |||||||||

| WOA | 3.0146 | 0.0839 | 0.0146 | 0.0841 | 0.9931 | 0.0135 | -0.0069 | 0.0135 | 0.0977 | ||||||||||

| SCA | 4.3549 | 21.0940 | 1.3549 | 22.9298 | 0.9192 | 0.0805 | -0.0808 | 0.0870 | 23.0168 | ||||||||||

| PSO | 2.9608 | 0.2002 | -0.0392 | 0.2017 | 1.0302 | 0.0621 | 0.0302 | 0.0630 | 0.2647 | ||||||||||

| 100 | GWO | 3.0014 | 0.0441 | 0.0014 | 0.0441 | 0.9943 | 0.0064 | -0.0057 | 0.0064 | 0.0505 | |||||||||

| WOA | 3.0349 | 0.6214 | 0.0349 | 0.6226 | 0.9926 | 0.0082 | -0.0074 | 0.0083 | 0.6309 | ||||||||||

| SCA | 4.2779 | 20.1040 | 1.2779 | 21.7370 | 0.9234 | 0.0699 | -0.0767 | 0.0758 | 21.8128 | ||||||||||

| PSO | 2.9291 | 0.1967 | -0.0709 | 0.2017 | 1.0422 | 0.0639 | 0.0422 | 0.0657 | 0.2674 | ||||||||||

| 150 | GWO | 3.0066 | 0.0299 | 0.0066 | 0.0299 | 0.9987 | 0.0043 | -0.0013 | 0.0043 | 0.0342 | |||||||||

| WOA | 3.0234 | 0.3187 | 0.0234 | 0.3192 | 0.9978 | 0.0052 | -0.0022 | 0.0052 | 0.3245 | ||||||||||

| SCA | 4.1678 | 18.3840 | 1.1678 | 19.7478 | 0.9332 | 0.0639 | -0.0668 | 0.0684 | 19.8161 | ||||||||||

| PSO | 2.9208 | 0.2204 | -0.0792 | 0.2267 | 1.0512 | 0.0725 | 0.0512 | 0.0751 | 0.3018 | ||||||||||

| 200 | GWO | 3.0032 | 0.0221 | 0.0032 | 0.0221 | 0.9958 | 0.0034 | -0.0042 | 0.0034 | 0.0255 | |||||||||

| WOA | 3.0362 | 0.5993 | 0.0362 | 0.6006 | 0.9941 | 0.0051 | -0.0059 | 0.0051 | 0.6057 | ||||||||||

| SCA | 3.7839 | 12.7150 | 0.7839 | 13.3295 | 0.9521 | 0.0441 | -0.0479 | 0.0464 | 13.3759 | ||||||||||

| PSO | 2.9389 | 0.1504 | -0.0611 | 0.1541 | 1.0511 | 0.0865 | 0.0511 | 0.0891 | 0.2432 | ||||||||||

| 30 | GWO | 3.0225 | 0.6012 | 0.0225 | 0.6017 | 1.9468 | 0.0841 | -0.0532 | 0.0869 | 0.6886 | |||||||||

| WOA | 3.0224 | 0.6012 | 0.0224 | 0.6017 | 1.9468 | 0.0842 | -0.0532 | 0.0870 | 0.6887 | ||||||||||

| SCA | 3.6743 | 11.9780 | 0.6743 | 12.4327 | 1.8690 | 0.2285 | -0.1310 | 0.2457 | 12.6783 | ||||||||||

| PSO | 2.9904 | 0.6933 | -0.0096 | 0.6934 | 1.9725 | 0.1022 | -0.0275 | 0.1030 | 0.7963 | ||||||||||

| 50 | GWO | 3.0107 | 0.3429 | 0.0107 | 0.3430 | 1.9676 | 0.0537 | -0.0324 | 0.0547 | 0.3978 | |||||||||

| WOA | 3.0110 | 0.3430 | 0.0110 | 0.3431 | 1.9675 | 0.0537 | -0.0325 | 0.0548 | 0.3979 | ||||||||||

| SCA | 3.2505 | 4.3296 | 0.2505 | 4.3924 | 1.9430 | 0.1048 | -0.0570 | 0.1080 | 4.5004 | ||||||||||

| PSO | 2.9927 | 0.3700 | -0.0073 | 0.3701 | 1.9843 | 0.0655 | -0.0157 | 0.0657 | 0.4358 | ||||||||||

| 100 | GWO | 2.9949 | 0.1723 | -0.0051 | 0.1723 | 1.9730 | 0.0268 | -0.0270 | 0.0275 | 0.1999 | |||||||||

| WOA | 2.9952 | 0.1726 | -0.0048 | 0.1726 | 1.9728 | 0.0268 | -0.0272 | 0.0275 | 0.2002 | ||||||||||

| SCA | 3.2988 | 5.2872 | 0.2988 | 5.3765 | 1.9401 | 0.0927 | -0.0599 | 0.0963 | 5.4728 | ||||||||||

| PSO | 2.9636 | 0.2362 | -0.0364 | 0.2375 | 1.9934 | 0.0475 | -0.0066 | 0.0475 | 0.2851 | ||||||||||

| 150 | GWO | 2.9939 | 0.1153 | -0.0061 | 0.1153 | 1.9735 | 0.0167 | -0.0265 | 0.0174 | 0.1327 | |||||||||

| WOA | 2.9941 | 0.1153 | -0.0059 | 0.1153 | 1.9734 | 0.0167 | -0.0266 | 0.0174 | 0.1327 | ||||||||||

| SCA | 3.2557 | 4.8181 | 0.2557 | 4.8835 | 1.9407 | 0.0793 | -0.0593 | 0.0828 | 4.9663 | ||||||||||

| PSO | 2.9686 | 0.1893 | -0.0314 | 0.1903 | 1.9977 | 0.0426 | -0.0023 | 0.0426 | 0.2329 | ||||||||||

| 200 | GWO | 3.0112 | 0.0830 | 0.0112 | 0.0831 | 1.9764 | 0.0141 | -0.0236 | 0.0147 | 0.0978 | |||||||||

| WOA | 3.0112 | 0.0830 | 0.0112 | 0.0831 | 1.9764 | 0.0141 | -0.0236 | 0.0147 | 0.0978 | ||||||||||

| SCA | 3.2250 | 3.8130 | 0.2250 | 3.8636 | 1.9489 | 0.0657 | -0.0511 | 0.0683 | 3.9319 | ||||||||||

| PSO | 2.9890 | 0.1246 | -0.0110 | 0.1247 | 1.9888 | 0.0276 | -0.0112 | 0.0277 | 0.1524 | ||||||||||

| n | Min | 1st Qu. | Mean | Mode | Median | 3rd Qu. | Max | S2 | γ1 | γ2 |

| 69 | 1.3120 | 2.0892 | 2.4553 | 2.3010 | 2.4780 | 2.7797 | 3.8580 | 0.2554 | 0.1021 | 3.2253 |

| -ln L | AIC | AICC | CAIC | BIC | HQIC | ||||

| EMLOG | - | 2.2141 | 0.2472 | 50.4143 | 104.8286 | 105.0104 | 111.2968 | 109.2968 | 106.6013 |

| Gamma | 22.8047 | - | 0.1077 | 50.9856 | 105.9712 | 106.1530 | 112.4394 | 110.4394 | 107.7439 |

| Lognormal | - | 0.8762 | 0.2161 | 52.1663 | 108.3326 | 108.5144 | 114.8008 | 112.8008 | 110.1053 |

| Log-logistic | - | 0.8883 | 0.1187 | 51.4346 | 106.8692 | 107.0510 | 113.3374 | 111.3374 | 108.6419 |

| Weibull | 2.6585 | - | 5.2702 | 51.7165 | 107.4330 | 107.6148 | 113.9012 | 111.9012 | 109.2057 |

| Rayleigh | - | - | 1.7720 | 87.4975 | 176.9950 | 177.0547 | 180.2291 | 179.2291 | 177.8813 |

| Exponential | - | 2.4553 | - | 130.979 | 263.9580 | 264.0177 | 267.1921 | 266.1921 | 264.8443 |

| n | min | 1st Qu. | mean | mode | median | 3rd Qu. | max | S2 | γ1 | γ2 |

| 63 | 0.55 | 1.3675 | 1.5068 | 1.61 | 1.59 | 1.6875 | 2.24 | 0.1051 | -0.8999 | 3.9238 |

| -ln L | AIC | AICC | CAIC | BIC | HQIC | ||||

| EMLOG | - | 1.3923 | 0.1550 | 18.1280 | 40.2560 | 40.4560 | 46.5423 | 44.5423 | 41.9418 |

| Gamma | 17.4396 | - | 0.0864 | 23.9515 | 51.9030 | 52.1030 | 58.1893 | 56.1893 | 53.5888 |

| Lognormal | - | 0.3811 | 0.2599 | 28.0089 | 60.0178 | 60.2178 | 66.3041 | 64.3041 | 61.7036 |

| Log-logistic | - | 0.4228 | 0.1262 | 22.7900 | 49.5800 | 49.7800 | 55.8663 | 53.8663 | 51.2658 |

| Rayleigh | - | - | 1.0895 | 49.7909 | 101.5818 | 101.6474 | 104.7249 | 103.7249 | 102.4247 |

| Exponential | - | 1.5068 | - | 88.8303 | 179.6606 | 179.7262 | 182.8037 | 181.8037 | 180.5035 |

| n | min | 1st Qu. | mean | mode | median | 3rd Qu. | max | S2 | γ1 | γ2 |

| 128 | 0.08 | 3.3350 | 9.2094 | 2.02 | 6.28 | 11.7150 | 79.05 | 108.2132 | 3.3987 | 19.3942 |

| -ln L | AIC | AICC | CAIC | BIC | HQIC | |||

| EMLOG | 4.1273 | 3.7637 | 450.4944 | 904.9888 | 905.0848 | 912.6929 | 910.6929 | 907.3064 |

| Normal | 9.2094 | 10.4026 | 480.9070 | 965.8140 | 965.9100 | 973.5181 | 971.5181 | 968.1316 |

| Logistic | 7.4546 | 4.3693 | 453.7950 | 911.5900 | 911.6860 | 919.2941 | 917.2941 | 913.9076 |

| n | min | 1st Qu. | mean | mode | median | 3rd Qu. | max | S2 | γ1 | γ2 |

| 100 | 0.80 | 4.65 | 9.8770 | 7.10 | 8.10 | 13.05 | 38.50 | 52.3741 | 1.4728 | 5.5403 |

| -ln L | AIC | AICC | CAIC | BIC | HQIC | |||

| EMLOG | 5.9090 | 3.2337 | 331.9065 | 667.8130 | 667.9367 | 675.0233 | 673.0233 | 669.9217 |

| Normal | 9.8770 | 7.2370 | 339.3140 | 682.6280 | 682.7517 | 689.8383 | 687.8383 | 684.7367 |

| Logistic | 8.9296 | 3.7895 | 334.6980 | 673.3960 | 673.5197 | 680.6063 | 678.6063 | 675.5047 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).