1. Introduction

Given a set of numbers

such that

An addition sequence [

1,

2] for the set

N, denoted by ASeq(

N), is an increasing sequence of numbers

such that (1)

(2)

(3)

and (4)

i.e., each number

should appear in the sequence

The number

l is called the length of ASeq(

N). The minimal length of an ASeq(

N) is denoted by

In the case of

the sequence is called addition chain [

1,

2].

The problem of generating a shortest ASeq(N) is equivalent to the simultaneous evaluation of k power monomials with a minimum number of multiplications.

For example, let The following are two ASeqs with lengths 15 and 13, respectively.

The elements of the first ASeq are: 1, 2=1+1, 3=2+1, 6=3+3, 12=6+6, 13=12+1, 26=13+13, 39=26+13, 40=39+1, 53=40+13, 106=53+53, 159=106+53, 160=159+1, 163=160+3, 203=163+40, 363=203+160.

The elements of the second ASeq are: 1, 2=1+1, 3=2+1, 5=3+2, 10=5+5, 13=10+3, 20=10+10, 40=20+20, 53=40+13, 80=40+40, 160=80+80, 163=160+3, 203=163+40, 363=203+160

The evaluation of

using the first sequence is

while the evaluation of the same powers using the second sequence is

A step

i is called star if

and non-star if

. In case of

the step is called doubling. If all steps in the sequence are stars, then the sequence is called star. If

denotes to the minimal length of star ASeq(

N), then we have

Yao [

3] showed that:

for some constant

.

Bleichenbacher [

4] computed the lower bound

where

ASeqs have received a lot of consideration among mathematicians and computer scientists for the following reasons:

The first reason is that one of the fundamental operations that play an important role in the efficiency of many public key cryptosystems and protocols is group exponentiation (sometimes it is called

multi-

modular exponentiation [

2,

5]), i.e., computing

simultaneously with a minimal number of operations, where

g is an element in a group. Designing a fast algorithm for generating a shortest (or short) ASeq increases the efficiency of such public key cryptosystems and protocols since evaluating

with a minimal number of multiplications is equivalent to finding a shortest ASeq(

N).

The second reason is that ASeqs (including addition chains) are generalized to the following:

- (i)

B-chains [

7], where every element in the B-chain has the form

and the binary operation

o belongs to a finite set of binary operations over the set of natural numbers

B, i.e.

. Guzmán-Trampe et. al. [

8] proposed a method for generating addition-subtraction,

sequence for the Kachisa–Schaefer–Scott family of pairing-friendly elliptic curves.

- (ii)

Vectorial addition chain [

9,

10]: it is a sequence of

k-dimensional vectors of nonnegative integers

, such that (1)

,

, …,

, (2)

, and (3)

Finding a shortest vectorial addition chain is equivalent to evaluating, multi-exponentiation, i.e., the product

with the minimal number of multiplications.

The third reason is that in Internet of Things, IoT, devices with limited resources have a problem when they perform some public-key primitives, such as decryption and signature, because most public-key primitives are

(i) time-consuming compared with symmetric-key cryptosystems; and

(ii) using private information. One of the common solutions to this problem is to use what is called “server aided secret computation protocols”, denoted by SASCP [

11], or sometimes it is called outsourcing protocols [

12].

In SASCP, devices with limited power and resources, such as smart cards, can execute public-key primitives efficiently with the aid of an untrusted powerful server without revealing the private information. Examples of such protocols that used ASeqs are [

6,

11,

13]. Other protocols and their security analysis are [

12,

14]. Another and similar solution to the problem is to define a delegation protocol. It is a protocol that satisfies two security objectives:

(i) privacy: the private information should not be recovered by a passive attacker; and

(ii) verifiability: the untrusted server should not be able to make the devices accept an invalid value as the result of the delegated computation. Examples of such protocols and their security analysis are [

12,

15,

16,

17].

The main challenge of finding a shortest ASeq, i.e., the minimal number of additions needed to compute all elements of

N, that it is NP-complete [

4]. Additionally, when the size of

N is large and the size of exponents is large, the running time for finding ASeq is very large [

18]. Therefore, designing a fast algorithm for generating a short (not necessarily shortest) ASeq is interesting using metaheuristics techniques such as simulated annulling, ant colony and evolutionary algorithms.

In this paper, a new metaheuristic algorithm based on simulated annealing strategy is proposed to find a short ASeq for the set N. The proposed simulated annulling algorithm for ASeq has three advantages over the previous ASeq algorithms. The first advantage is the designed algorithm has running time less than the exact algorithm. The second advantage is the length of ASeq generated by the proposed algorithm is shorter than the ASeq generated by previous heuristic algorithms. The third advantage is that there is no comparative study between suboptimal algorithms and the exact algorithm in terms of the length of ASeq.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 includes the related works of ASeq. In

Section 3, the details of the proposed algorithm is given. Section 4 includes the dataset used in the experiments, and the results and analysis of the experimental studies for the proposed simulated annulling algorithm and other algorithms. Finally,

Section 5 includes the conclusion of this paper and the future works.

2. Related Works

Algorithms for generating ASeq, i.e.

can be classified into two categories. The first category is to find a shortest ASeq. In fact, there are a few papers that discussed a generation of shortest ASeqs. Bleichenbacher [

4] suggested an algorithm to find a shortest ASeq(

N) with length

r provided that we previously computed

for all numbers

and

He used the suggested algorithm to generate a shortest addition chain up to a certain number.

The authors in [

18] suggested a branch and bound depth-first search algorithm to generate a shortest ASeq for any set

N. The algorithm starts by computing a lower bound, Eq(3), and looking for an addition chain for the first element

in the set

N. Then, it extends the chain to addition sequence for

, and so on until it generates ASeq(

N). The algorithm uses different strategies to speed up the generation as follows. (

i) Using bounding sequences to prune some branches in the search tree, which cannot lead to a shortest ASeq. (

ii) Determining an upper bound of

(

iii) Using some sufficient conditions for star steps to skip the generation of non-star steps.

(vi) If no ASeq(

N) of length

l is found, then the algorithm increases

l by one and repeats the process until either

l is equal to the length of the generated short ASeq produced by continued fraction (CF) method [

19] or the algorithms finds a shortest ASeq. Recently, the authors in [

20] used multicore systems to improve the generation of a shortest ASeq.

The second category is to find a short ASeq. Yao [

3] presented an algorithm to compute

in

multiplications for some constant

c. Bos and Coster [

21] proposed four methods to generate a short ASeq to use it in the window method [

21]. The upper bound of the length of generated an ASeq

, by the four methods, could be estimated, experimentally, by

for

Bergeron et al. [

19] proposed an efficient method based on CF. The suggested method can be considered as an extension and unifying approach of some previously known methods (such as binary and

k-ary methods [

1]) for generating a short addition chain, i.e., ASeq with

k=1.

Recall that the CF expansion of

denoted by

…,

is

where

d is an integer in the range

Bergeron et al. [

19] suggested different strategies for choosing the value of

d. One of the efficient strategies that produces a good suboptimal ASeq is dichotomic strategy, where

Let

denotes the length of the ASeq(

) generated by CF using dichotomic strategy. Then

where

and

where

d is defined by Eq. (6).

Enge

et. al. [

22] proposed a special method to construct a short ASeq to find the first

k nonzero terms in the sparse q-series belonging to the Dedekind eta function or the Jacobi theta constants. Nadia and Mourelle [

23] used Anti Colony strategy to find a short ASeq. They tested the strategy for a small set of numbers. Abbas and Gustafsson [

24] proposed a method based on integer linear programming to generate a short ASeq for a small set of numbers.

In all previous studies, there was not enough experimental study for generating a short ASeq with different sizes of the set N, or with different range values of each number in the set N. Also, there is no comparative study between suboptimal algorithms and the exact algorithm in terms of the length of ASeq.

3. The Proposed Method

In this section, we first present a brief description of the proposed algorithm that is based on simulated annealing strategy to find short ASeq, and then we present its details. The algorithm is named SAAS for simulated annealing addition sequence.

Initially, the algorithm starts by generating the initial state,

, using the CF method [

19], and its energy is equal to the length of

,

. Then, the algorithm assigns these two values to the best state and the best energy, respectively. After that, the algorithm repeats the following steps based on the number of Metropolis cycles,

m, for a fixed temperature. In each iteration of this loop, the algorithm performs the following steps:

The first step is generating a new state, , and its energy, . The second step is determining whether the algorithm accepts this new state or not. The algorithm accepts the new state and its energy, and then assigns these values to the best state and best energy if either of the following conditions is true. (1) if the energy of the new state is lower than the energy of the best state. (2) If the Boltzmann distribution is greater than a random real number in the range [0,1].

After completing the number of Metropolis cycles for a fixed temperature, the algorithm updates the temperature using the Kirkpatrick quenching method and repeats this process until it reaches the maximum number of annealing iterations.

The details of the algorithm steps are as follows.

Step 1: Generate the initial state, , using CF method for the set of exponents , where such that (1) and , (2) s.t. and , (3) such that and .

Step 2: Repeat the following m times:

Step 2.1: Generate a random integer number, r, from the range . This number will be used as a start point of mutation based on the elements of N.

Step 2.2: Generate a new state, , by mutate , from the location . If r=0, then the algorithm mutates from the element . Otherwise, the algorithm mutates the state from to . The process of generating the new elements from to is based on the following rules.

Rule # 1: Doubling the current element, .

Rule # 2: Summing the last two elements, .

Rule # 3: Summing the last element with any other random element in the sequence, +, .

This step can be done as follows (Steps 2.2.1-2.2.3).

Step 2.2.1 (Generate one element in the sequence): If the current goal is and the current ASeq is , then the steps of generating a new element in the chain are as follows.

If then apply rule # 1

Else if then apply rule # 2

Else if then

Generate a random real number

If then apply the rule # 1

Else

Generate a random real number

If then apply the rule # 2

Else

Generate a random integer number

Apply the rule # 3, where h=r.

Else //

Generate a random integer number

Apply the rule # 3, where h=r.

If the new element is less than or equal to then the element is

accepted. Otherwise, decrease the value of r and apply rule #3 until

we found a certain value of h such that the new element is less than or

equal to .

Step 2.2.2 (Generate all elements between and ): Repeat Step 2.2.1 starting from , and , until the algorithm finds . In this case, the algorithm updates the value of

Step 2.3.3 (Generate the ASeq from to ): Repeat Steps 2.2.1 and 2.2.2 until generate . Therefore,; and .

Step 3: Test the acceptance of the new state by the following substeps.

If then and

Else generate a random real number .

If then and

Step 4: Decrease the temperature using Kirkpatrick quenching method: , where .

Step 5: Repeat Steps 2, 3, and 4 until reach the maximum number of annealing iterations.

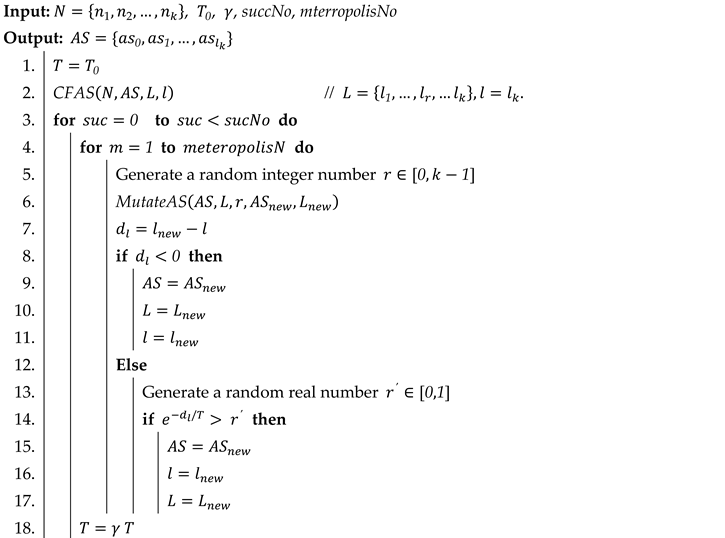

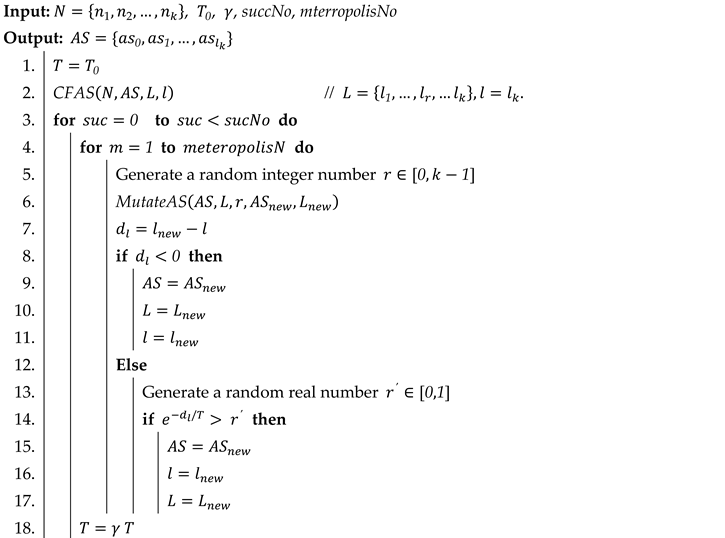

The complete pseudocodes for the new proposed SAAS is given in Algorithms 1 and 2.

| Algorithm 1: SAAS |

|

| Algorithm 2: MutateAS |

|

3. Results and Discussions

This section demonstrates the experimental study and its analysis for measuring the performance of the SAAS algorithm compared to the exact and heuristic solutions, ExAS and CFAS, respectively. The three algorithms were programmed using the C language and run on a machine with a processor of speed of 2.5 GHz and a memory of 16 GB. Also, the three algorithms were compared by measuring the execution time in milliseconds and the length of the short/shortest sequence. The section consists of two subsections: data generation and results.

3.1. Data Generation

The data used in the experimental study is based on two factors. The first factor is the number of elements k in the set of exponents . The experimental values of k are 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10. The second factor is the domain of each exponent in the set N. According to the window method and its variations, the range of exponents is the integer interval , where e is the window length (of size e-bits). Also, according to the performance of the window method, the value of each exponent should be odd. The experimental values of e are equal to 7, 8, 9, and 10. The reason for starting the values of e with 7, the running times for all compared algorithms are fast when

The methodology of generating the ASeq is based on fixing the size of the window, i.e., e-bits, say e=7, and then generating different sets with lengths k= 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10. For each value of k, the algorithm generates 25 sets of exponents in the range. The process of generating different sets of exponents is as follows.

Set e to the maximum number of bits in the exponents, i.e., the window size.

Set the set and i=2.

While do the following

Construct a new set by adding two randomly odd numbers, in the range to the set { the two generated randomly odd numbers}

Set i=i+2.

Make sure that is sorted.

Repeat Steps 2-4, 25 times to generate 25 sets of exponents with at most e-bits.

Repeat Steps 1-5 for different size of exponents e=7, 8, 9, and 10.

The following example illustrates the generation of five sets with different values of k and fixed size of exponents e=8.

3.2. Results

The results of implementing the three algorithms on the generated data in terms of the length of the output are shown in

Table 1. The first two columns represent the two factors

e and

k, while the three last columns represent the percentage of differences in the lengths of the output for the following cases: (1) ExAS and SAAS algorithms, (2) ExAS and CFAS algorithms, and (3) SAAS and CFAS algorithms. Since the exact algorithm always produces the shortest ASeq, the methodology for analyzing the results is computing the number of cases in which the lengths of ASeqs generated by the SAAS and CFAS algorithms are greater than the shortest ASeq generated by the ExAs algorithm. The percentages of these cases represent the third and fourth columns. Also,

Table 1 presents the difference between the lengths of the ASeqs generated by the SAAS algorithm and those generated by the CFAS algorithm, see the, the last column in

Table 1.

The analysis of data results shows the following observations.

First, as in

Table 1, the percentage of the difference between the lengths of the ASeq generated by the exact algorithm, ExAS, and the heuristic algorithms, SAAS and CFAS, increases with the increase in the number of elements in the set

N. For example, for fixed

e=7 and

k=2, 4, 6, 8, and 10, the percentages of cases that the exact algorithm generates ASeq with a length less than that generated by the SAAS algorithm are 12%, 40%, 56%, 76%, and 88%. Similarly, for the CFAS algorithm, the differences are 28%, 64%, 76%, 84%, and 92%.

Second, as in

Table 1, the comparison between the lengths of ASeqs generated by the SAAS and CFAS algorithms, independent of the ExAS algorithm, , is presented in the last column. The data shows that the SAAS algorithm outperforms the CFAS algorithm in terms of the short ASeq for all studied cases.

Third, the length of the output generated by the SAAS algorithm is near to the shortest length compared to that generated by the CFAS algorithm.

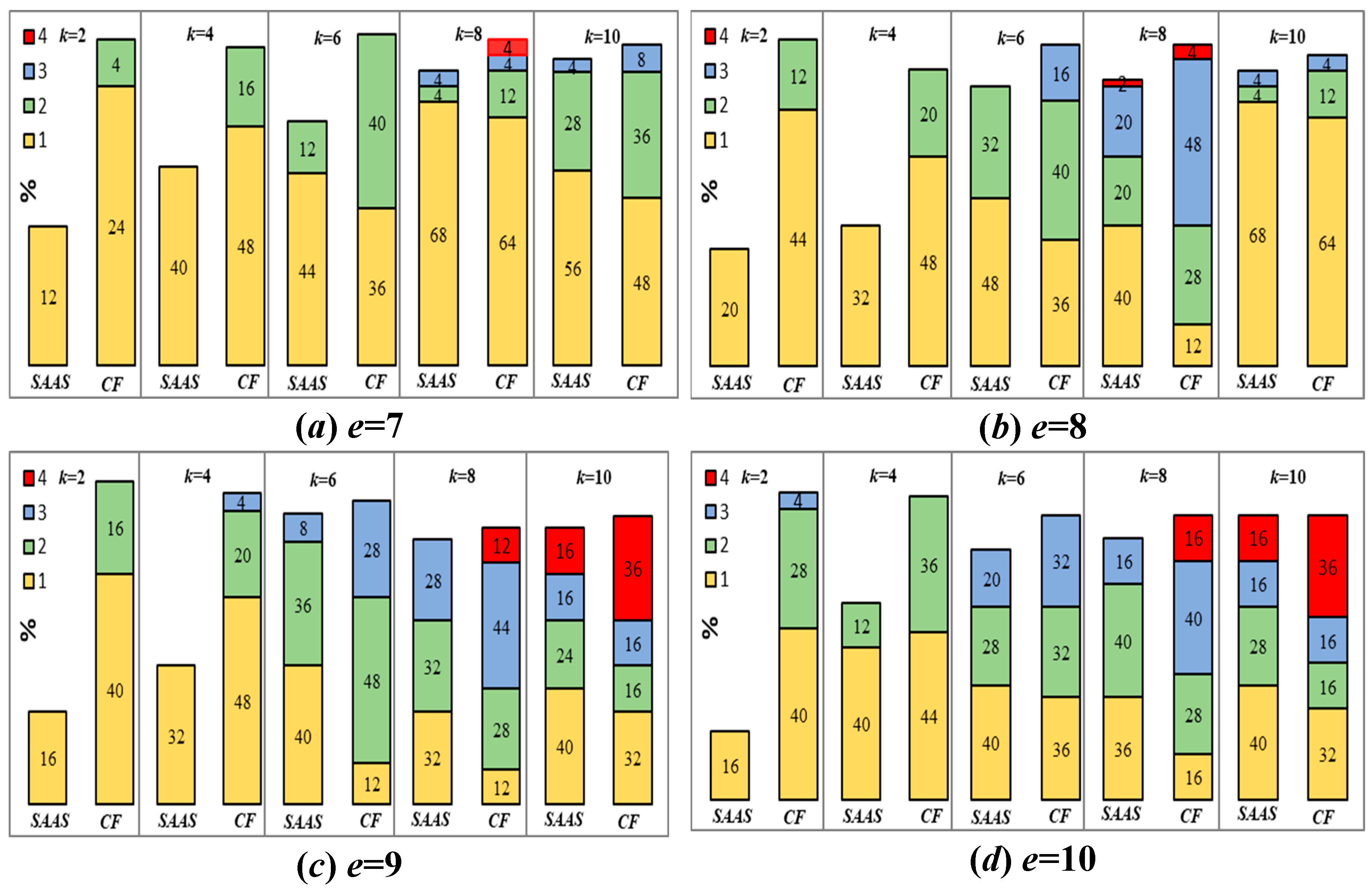

Figure 1 shows the distribution of difference between the length of the output for the SAAS algorithm (similarly the CFAS algorithm) and the output of the exact algorithm. It is clear that the SAAS algorithm generates short ASeq with lengths that are near to the shortest ASeq than that generated by the CFAS algorithm. For example, when

e=8 and

k=2, there are 20% of the instances where the length of ASeq generated by the SAAS algorithm is greater by one than the length of ASeq generated by the ExAS algorithm. On the other side, using the CFAS algorithm, there are 44% and 20% of instances have lengths greater than the shortest by one and two, respectively.

The comparison between the three algorithms, ExAS, SAAS, and CFAS, in terms of execution time is shown in

Table 2. The analysis of data in the table demonstrates the following observations. (1) The fastest running time for all compared algorithms is CFAS algorithm. (2) The CFAS algorithm is not affected by the values of

e and

k in general. On the other side, the SAAS algorithm is slightly affected by increasing

e and

k, whereas the ExAS algorithm is significantly affected by increasing

e and

k. (3) The running time for the SAAS algorithm is affected by the two parameters,

succNo and

metropolis. The increase in the values of two parameters leads to a slight increase in the running time. (4) The running time for SAAS algorithm is faster than the exact algorithm, and the difference between the two algorithms in running time increases with increase in

e and

k. (5) The last column of

Table 2 shows the percentage improvement for the SAAS algorithm compared to the exact algorithm.

5. Conclusion and Future Works

In this paper, finding a short addition sequence for a set of positive integers was studied. A new metaheuristic algorithm was proposed to find an addition sequence with short length. The proposed algorithm starts with generating sequence using continued fraction and then apply the simulated annealing strategy to improve the length of the sequence. The proposed algorithm is fast compared to the exact algorithm and able to generate addition sequence with length less than the previous heuristic algorithm.

The efficiency of the proposed algorithm was conducted with considering different parameters such as the number of elements in the set and the size of positive integer.

There are many research directions related to addition sequence such as (1) extend the concept of B-chains and verctorial chain to ASeq, (2) use high-performance system to accelerate the computation of ASeq, and (3) accelerating the multi-modular exponentiation used ASeq.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Hazem B. and Hatem M.; methodology, Hazem B. and Hatem M.; software, Hazem B. and Hatem M.; validation, Hazem B., Hatem B.; formal analysis, Hazem B.; data curation, Hatem B.; writing—original draft preparation, Hazem B., M. H., and Hatem M.; writing—review and editing, Hazem B., M.H., and Hatem B.; visualization, Hazem B., and M.H.; supervision, Hazem B.; project administration, Hazem B.; funding acquisition, Hazem B.

Funding

This research has been funded by Scientific Research Deanship at University of Ha’il - Saudi Arabia through project number IFP-22 025.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the support provided by Scientific Research Deanship at University of Ha’il - Saudi Arabia through project number IFP-22 025.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Knuth, D.E. The Art of Computer Programming: Seminumerical Algorithms, 3rd ed.; Addison-Wesley: Reading, UK, 1997; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Menezes, A.; van Oorschot, P.; Vanstone, S. Handbook of Applied Cryptography; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, A. On the Evaluation of Powers. SIAM J. Comput. 1976, 5, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleichenbacher, D. Efficiency and Security of Cryptosystems Based on Number Theory. Ph.D. Thesis, Swiss Federal Institue of Technology Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fathy, K.; Bahig, H.; Farag, M. Speeding up multi-exponentiation algorithm on a multicore system. J. Egypt. Math. Soc. 2018, 26, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laih, C.; Yen, S.; Harn, L. Two efficient server-aided secret computation protocols based on the addition sequence. In Proceedings of the Advances in Cryptology-ASIACRYPT’91, Fujiyoshida, Japan, 11–14 November 1991; pp. 450–459. [Google Scholar]

- Bahig, H.M.; Nassr, D.I. Generating a Shortest B-Chain using Multi-GPUs. Inf. Sci. Lett. 2022, 11, 745–750. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán-Trampe, J.E.; Cruz-Cortés, N.; Perez, L.J.D.; Ortiz-Arroyo, D.; Rodríguez-Henríquez, F. Low-cost addition–subtraction sequences for the final exponentiation in pairings. Finite Fields Their Appl. 2014, 29, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thurber, E.; Clift, N. Addition chains, vector chains, and efficient computation. Discret. Math. 2021, 344, 112200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downey, P.; Leong, B.; Sethi, R. Computing sequences with addition chains. SIAM J. Comput. 1981, 10, 638–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laih, C.; Yen, S. Secure addition sequence and its applications on the server-aided secret computation protocols. In Proceedings of the Advances in cryptology-AUSCRYPT’92, Gold Coast, Australia, 13–16 December 1992; Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Volume 718, pp. 219–229. [Google Scholar]

- Bouillaguet, C.; Martinez, F.; Vergnaud, D. Cryptanalysis of Modular Exponentiation Outsourcing Protocols. Comput. J. 2022, 65, 2299–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, T.; Kato, K.; Imai, H. Speeding Up Secret Computations with Insecure Auxiliary Devices. In Advances in Cryptology — CRYPTO’ 88. CRYPTO 1988; Goldwasser, S., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1990; Volume 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.; Shparlinski, I.E. On the Insecurity of a Server-Aided RSA Protocol. In Advances in Cryp-tology — ASIACRYPT 2001. ASIACRYPT 2001; Boyd, C., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2001; Volume 2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Li, J.; Ma, J.; Tang, Q.; Lou, W. New Algorithms for Secure Outsourcing of Modular Exponentiations. IEEE Trans. Parallel Distrib. Syst. 2014, 25, 2386–2396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevalier, C.; Laguillaumie, F.; Vergnaud, D. Privately outsourcing exponentiation to a single server: cryptanalysis and optimal constructions. Comput. Secur.–ESORICS 2016, 261–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Crescenzo, G.; Khodjaeva, M.; Kahrobaei, D.; Shpilrain, V. Delegating a Product of Group Exponentiations with Application to Signature Schemes (Submission to Special NutMiC 2019 Issue of JMC). J. Math. Cryptol. 2020, 14, 438–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahig, H.M. A new strategy for generating shortest addition sequences. Computing 2011, 91, 285–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, F.; Berstel, J.; Brlek, S. Efficient computation of addition chains. J Theor Nombres Bord 1994, 6, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahig, H.M.; Kotb, Y. An Efficient Multicore Algorithm for Minimal Length Addition Chains. Computers 2019, 8, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, J.; Coster, M. Addition Chain Heuristics. In Advances in Cryptology — CRYPTO’ 89 Proceedings. CRYPTO 1989; Brassard, G., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1990; Volume 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enge, A.; Hart, W.; Johansson, F. Short Addition Sequences for Theta Functions. J. Integer Seq. 2018, 21, 18.2.4. [Google Scholar]

- Nedjah, N.; de Macedo Mourelle, L. Colony. In Knowledge-Based Intelligent Information and Engineering Systems; Khosla, R., Howlett, R.J., Jain, L.C., Eds.; KES 2005. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005; Volume 3684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, M.; Gustafsson, O. Integer Linear Programming Modeling of Addition Sequences with Additional Constraints for Evaluation of Power Terms. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.15002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).