1. Introduction

Adhesively bonded joints have been used with great success in several fabrication processes, because they promote a more even stress distribution, when compared to other conventional joints, such as bolting, riveting and spot welding, where high stress concentrations can occur. The possibility of obtaining lighter and waterproof structures with reduced corrosion risks contributes greatly for the adhesive joints use, working as an alternative to the conventional joints in several industries, including aerospace, automotive, and energy.

The fabrication of adhesive bond joints can originate defects of three different types: adhesive defects that are related to the weak bonding between the adhesive and the adherend, cohesive defects related to the mechanical properties of the adhesive, and gross defects, such as cracking, disbonding, porosity, and voids, [

1]. The formation of voids or absence of adhesive in the bond line is a great concern in industry [

2], so such defects will be studied and characterized in this work.

The development of non-destructive methods is essential for the condition monitoring of bonded structures. Probably, one of the most used methods is based on ultrasound guided waves. When compared to conventional point by point method, the guided waves are more attractive, because once generated they propagate over considerable distances with low attenuation, which allows inspecting large parts with considerable time saving.

Guided waves have often been used for defect detection in structures like strips, plates, or pipes [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10]. They have also proved to be effective for inspecting adhesive joints [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15] and adhesive bonds between composites [

16,

17], and for the adhesion level evaluation [

18]. Several studies using the ultrasound guided waves to assess the bonding quality of metal/epoxy/metal joints can be found in the literature, such as, comparison between air coupling and immersion techniques [

19], analysis of the spectra of the lowest-order antisymmetric (A

0) Lamb wave mode for tangential bond stiffness evaluation [

20], defects detection in the adhesive films and evaluation of their geometry by means of a weighted root mean square damage imaging algorithm [

21,

22], evaluation of interference effects of elastic waves generated by piezo sensors, excited with tone bursts of different extensions, with the length of the disbond [

23], study of the non-linear Lamb wave behavior [

24,

25], and development of a finite difference model to simulate and validate experiments using PZTs in bonded aluminium plates [

26].

Simulation allows predicting the ultrasound wave propagation in a particular medium and can be used to prove analytical and experimental approaches. Currently, the improvement of computational resources makes the implementation of numerical or grid-based methods possible. Recent works have used finite element methods (FEM) to accurately mimic wave propagation through bonded lap joints [

19,

23,

26,

27,

28,

29]. One of the major drawbacks of elastic wave models based on low-order finite difference or finite element schemes is the large number of grid points per wavelength required to avoid numerical dispersion. As an alternative, the k-Wave, which is an available third-party MATLAB toolbox, makes use of a Fourier domain pseudo spectral method for faster simulation and reconstruction of photoacoustic wave fields in a way that uses less memory and is user-friendly [

30,

31]. Many authors have used the k-Wave toolbox in diverse NDT applications related to nonlinear ultrasound propagation in absorbing media [

32], attenuation in ultrasonic computed tomography [

33], time domain power law attenuation in breast and liver tissues [

34], one-sided ultrasonic nondestructive evaluation [

35], high intensity focused ultrasound [

36], ultrasonic transducer field modelling [

37], 3-D ultrasound imaging [

38], A-scan ultrasound simulation in ophthalmology [

39], microflaw detection in carbon fiber reinforced polymers [

40], and guided waves in layered structures [

41,

42].

In the present study, the authors intend to implement a 3D simulation model of two aluminium plates bonded by an epoxy adhesive layer, using the k-Wave tool. Simulated defects with different sizes are introduced in the adhesive layer. A pitch and catch experimental setup is also used to detect and characterize the same type of defects. Simulated results are then compared with the experimental ones.

2. Theory

2.1. Ultrasound Guided Waves Propagation in a Single Plate

Lamb waves are a type of guided ultrasonic waves that exist in plate structures placed in vacuum, which can propagate relatively long distances. They are very useful to detect disbonds, corrosion and delaminations, efficiently [

43,

44,

45,

46]. If plates are immersed in water these waves are called leaky Lamb waves, due to the energy leakage into the surrounding fluid. The well-known dispersion equations that govern symmetrical (Eq.1) and antisymmetric (Eq.2) leaky Lamb wave modes were introduced by Viktorov [

43],

where i is the unit imaginary number, h is half the thickness of the plate,

,

, where

,

,

,

, ω is the angular frequency,

is the longitudinal velocity in the plate,

the transversal velocity in the plate,

is the phase velocity of a certain propagation mode and

is the velocity in the surrounding fluid. The plate and fluid densities are

and

, respectively.

The transcendental Eqs. (1) and (2) give rise to an infinite number of solutions that correspond to the propagation modes. The imaginary part of each equation represents the fluid influence. If this is not present, the equations characterize the plate in vacuum. The leakage to the fluid is responsible for attenuation, which is strongly dependent on the ratio of in-plane and out-of-plane displacements at the plate surfaces, for a given mode. For a particular propagation mode the phase velocity is complex,

, which gives rise to a complex wavenumber,

[

47]. The real part

represents the propagation properties of the wave and

is related to leakage attenuation. Considering that usually

, then after some manipulation the complex wavenumber can be represented as,

The absolute value of the imaginary part of Eq. 3 represents an exponential decay, usually called attenuation coefficient, α (Np/m). The solutions of the dispersion equations for a plate in vacuum are very similar to the real part of the solutions for an immersed plate, because it has been shown that the surrounding fluid gives rise to very small variations in the wave velocity [

48].

The particle displacement variation with plate thickness for each propagation mode is also very important. For the case of an immersed plate, if long range propagation is needed, then a low out-of-plane displacement must be assured to prevent the occurrence of great losses, due to leakage to the fluid. The displacements can be obtained using the method of potentials and the boundary conditions at plate surface. For a plate in vacuum oriented in X direction and with the thickness in Z direction, coincident with wave propagation direction, the in-plane (

uxs) and out-of-plane (

uzs) displacements of symmetric modes are given by [

43,

44]

and the displacements for the anti-symmetric modes (

uxa) and (

uza) by

For the case of a water immersed plate, equations (4) to (7) become complex, which can be interpreted physically as a small angle rotation of the ellipse displacement axes from the reference coordinate system [

49]. Nevertheless, the real part of the displacements practically coincides with the displacements obtained from equations (4) to (7) [

44]. So, as approximation, these equations can be used to represent the displacements as a function of plate thickness in immersion cases.

In analogy with optical phenomena, when an ultrasound wave reaches a boundary between two different media obliquely, refracted waves can occur with different transmission angles than the incident one. The incident (

) and transmitted (

) angles related to the normal plane are correlated by the well-known Snell's law, given by

where

and

are the propagation velocities in the different media. In practice, if one intends exciting a specific propagation mode in a plate, the phase velocity

(obtained from the dispersion curves) coincides with

, and in this case

, since the propagation develops along the plate. Then, knowing the

value, which corresponds to the propagation velocity in the fluid (

), the angle of incidence

can be easily obtained, to generate the desired propagation mode

Each Lamb wave mode is associated with an angle of re-emission, that by reciprocity is equal to the angle of incidence.

2.2. Propagation of Ultrasonic Guided Waves in Adhesively Bond Joints

The ultrasound guided wave propagation in a bonded lap joint can be modeled as the propagation in a multilayer structure, composed of two adherents and one adhesive. The transfer matrix method is certainly the most important technique used to study this problem and find the complex phase velocity of each one propagation modes. First used by Haskell [

50] for modelling propagation in seismology, the method was later adapted for studying the ultrasound guided wave propagation, by several researchers [

51,

52,

53,

54,

55]. The method considers that there are four generic waves in each layer, such as, two longitudinal waves (L+, L-) and two transversal ones (T+, T-), where the sign (+) indicates upward direction, and (-) indicates downward direction. So, a field matrix (D) that describes the relationship between the displacements (u), stresses (σ) and wave amplitudes (A) at any location in a layer, can be established as

In the process, the equations for the intermediate interfaces are eliminated, so that the fields in all layers of the structure are described only in terms of the external boundary conditions. The modal solutions can be obtained by solving the resulting matrix system and the so-called dispersion curves, which represent the allowed propagation guided modes in the structure as function of frequency. The behavior of these guided modes is like those obtained through Eq. (1) and (2). Details about the method are described elsewhere [

56].

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Simulation model

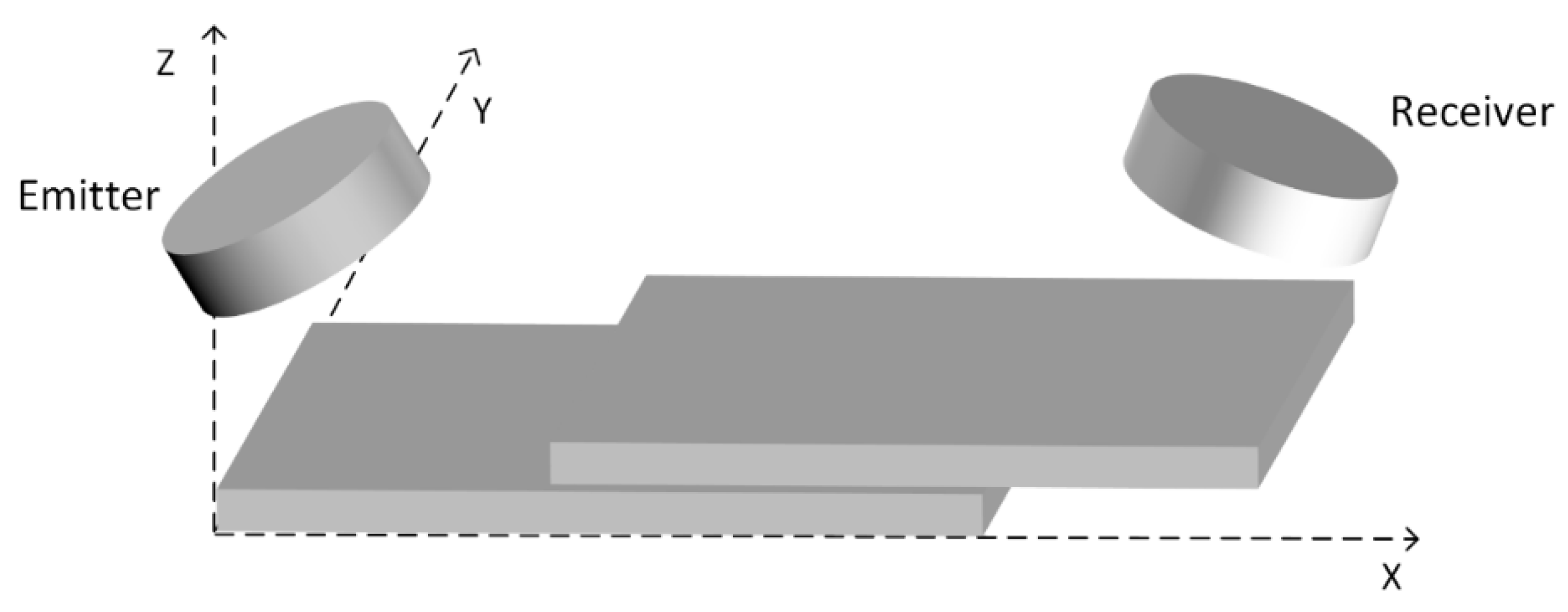

The simulation functions in k-Wave require four input structures, namely the properties of the computational grid, representing the medium through which the acoustic waves propagate, the material properties of the medium, the properties and locations of acoustic sources, and the properties and locations of the sensor points used to collect the pressure and velocity fields over time. When the acoustic waves reach the edge of the computational domain, they are absorbed by a special type of anisotropic absorbing boundary layer known as a perfectly matched layer (PML). The schematic of the 3D simulation setup is presented in

Figure 1 and its dimensions are: X=126 mm, Y=32 mm and Z=18 mm. The spatial resolution is 150 µm. Each plate is 90 mm in length, 30 mm in width and 4 mm in thickness. The section of bonded region is of 60 mm x 30 mm. The adhesive thickness is 150 µm. The emitter and receiver transducers are identical, with 25 mm in diameter. The incidence and reception angles are equal and given by Eq. (9). The defects were simulated by introducing air (absence of adhesive) with circular shape in the center of the joint region.

The acoustic properties of the materials used in the simulation are presented in

Table 1. For water and air, the values were taken from literature [

57]. For aluminium and epoxy the properties were obtained experimentally using a conventional pulse echo technique. For aluminium a 10 MHz transducer was used, due to the small thickness of the plates. As the thickness of the epoxy layer is very small, a cylinder with 20 mm height and 300 mm diameter was constructed to allow velocities’ measurements. The densities were taken from manufacturer's specifications.

3.2. Experimental setup

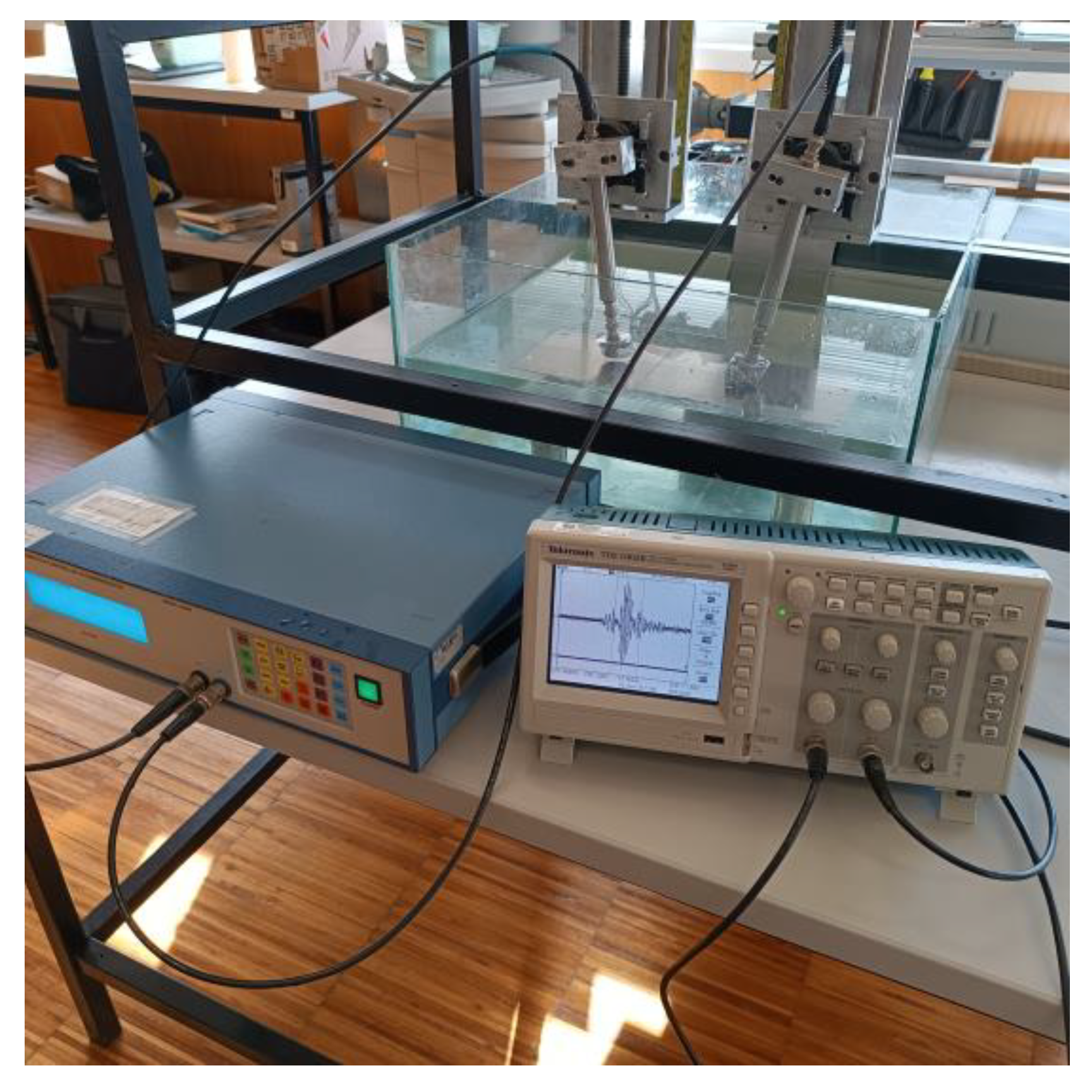

The ultrasonic experimental setup illustrated in

Figure 2 was used to evaluate the defects. It is composed by a Panametrics pulser/receiver model 5800, a pair of immersion broadband transducers (Imasonic model IM 0.5 25 P) with 500 kHz central frequency and 25 mm active diameter, and a Tektronix digital oscilloscope (model TDS1002B). The aluminium alloy (5083-O) plates are 200 mm in length, 125 mm in width and 4 mm in thickness. The size of bonded region is of 60 mm x 125 mm (whole width). The bonded zone has the same dimensions as the one presented in the simulation model described in the previous section.

The used plates were bonded together by means of an epoxy adhesive (Araldite 2014, Vantico, Duxford, Cambridge, UK), of 150 μm in thickness, achieved by a uniform pressure of 0.1 Kg/m2. The adhesive was then cured according to the manufacturer’s instructions at room temperature (25°C) for 24 h.

The used approach to produce artificial defects in the bonded line consisted of removing a circular portion of aluminium equal to the adhesive thickness in one of the plates, and then that zone is covered with sticky tape to avoid adhesive penetration, as described in [

47].

4. Results

4.1. Phase velocities and displacements in a single plate in water

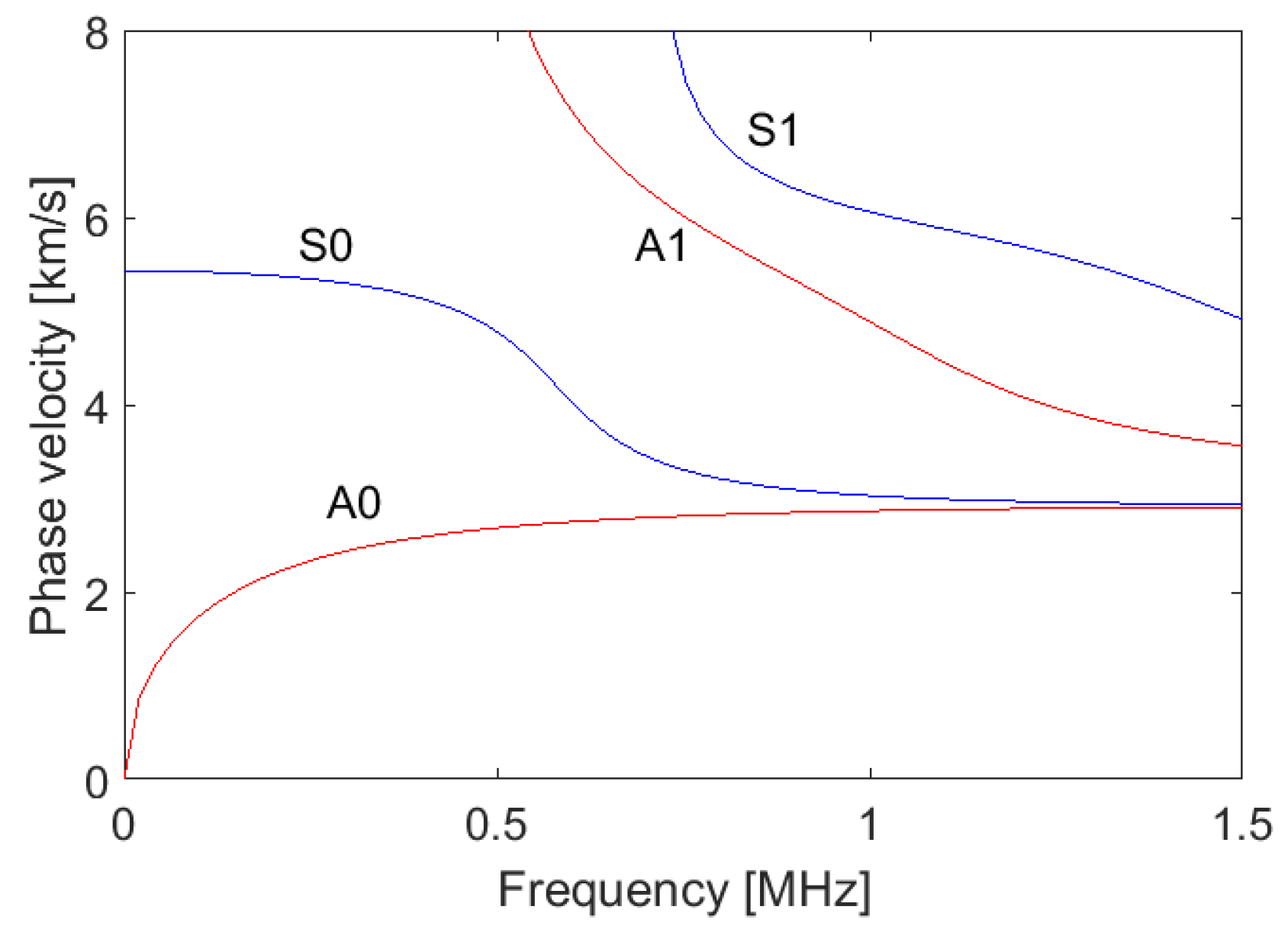

The solutions for the phase velocity were obtained from Eq. (1) and (2) using an iterative optimization algorithm. The first four propagation modes that correspond to the real part of the solutions for the aluminium plates used in this study, are shown in

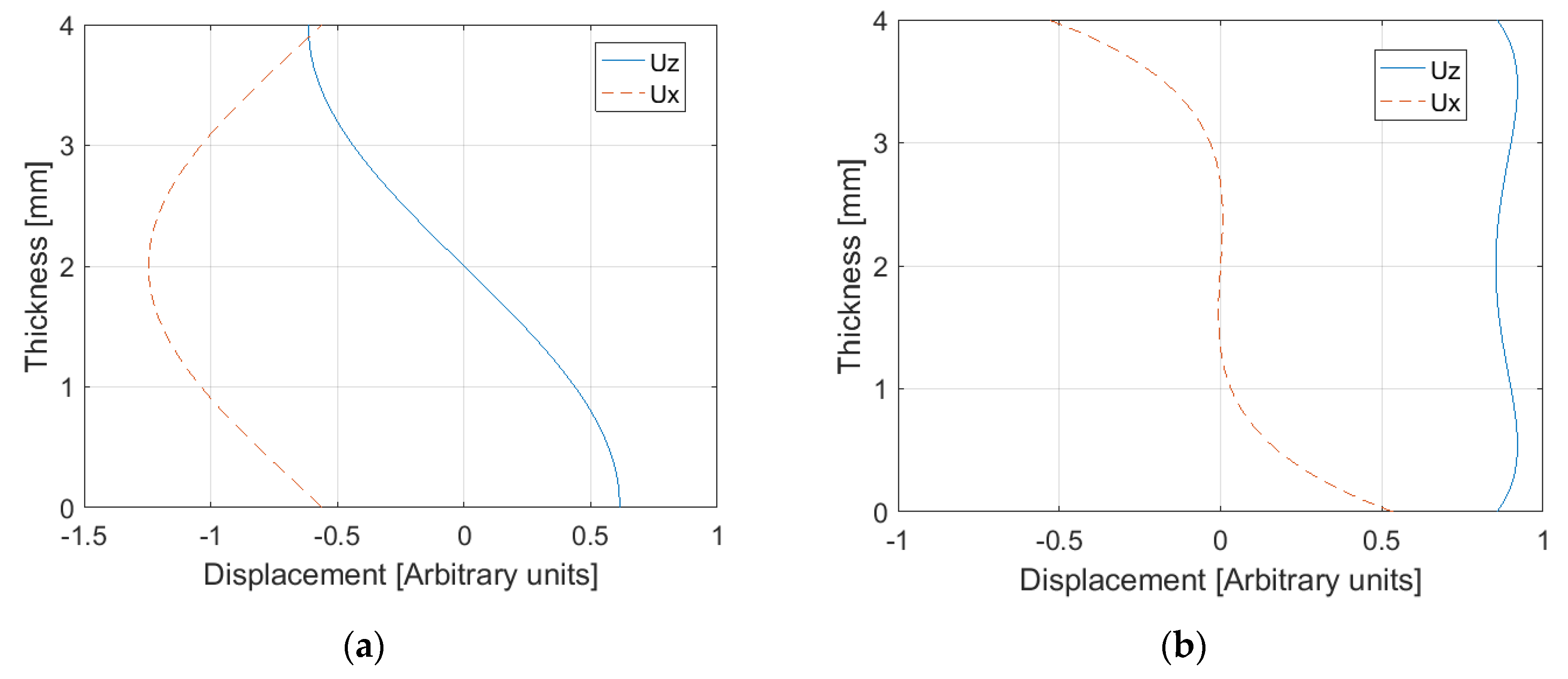

Figure 3.

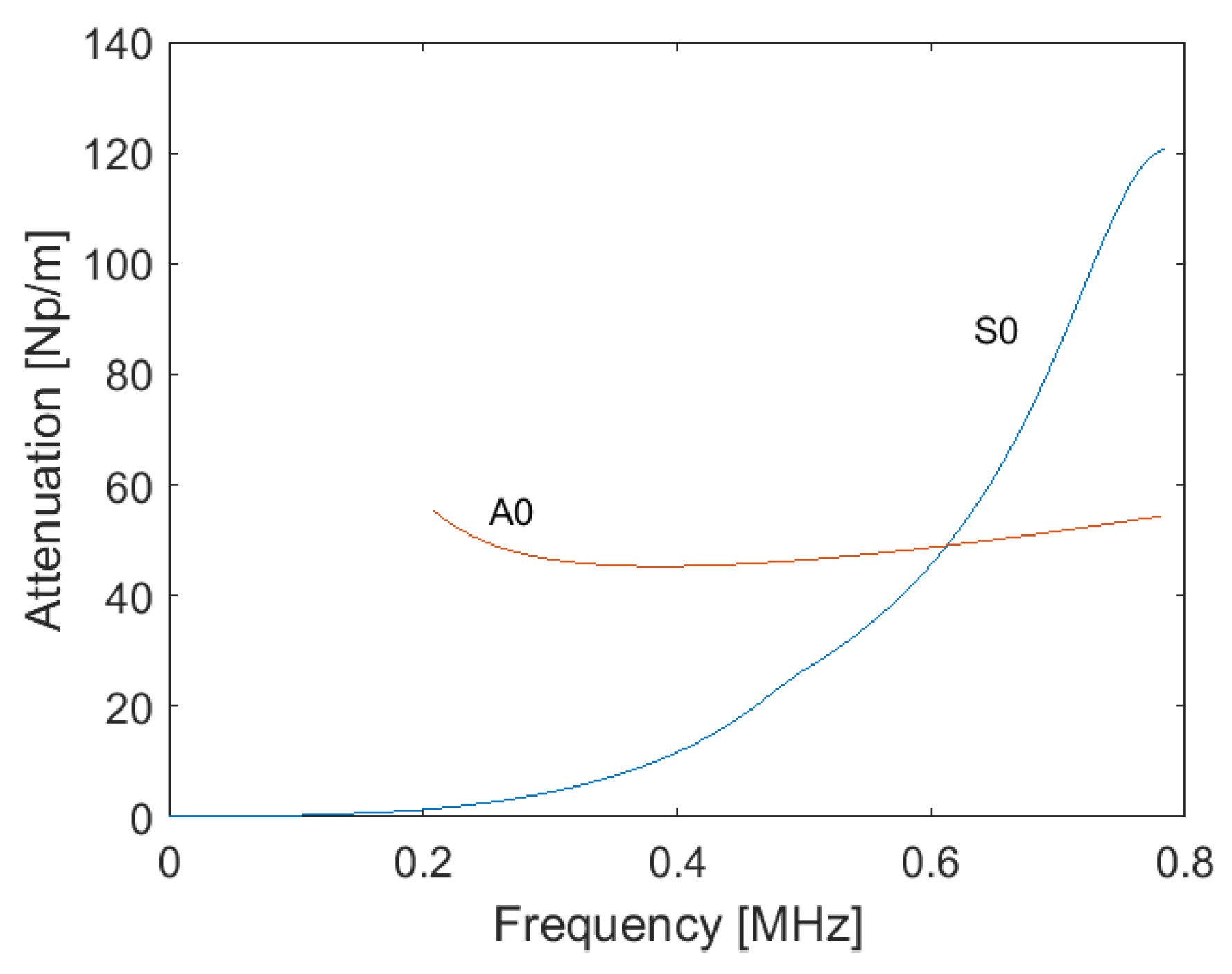

Figure 4 presents the leakage attenuation due to water, for the fundamental modes S0 and A0, obtained from the imaginary part of the equation (3). According to the used frequency (500kHz), it was selected the propagation mode S0, due to the high spatial separation compared to the other modes and the low attenuation compared to A0, allowing easier amplitude measurements.

From Eq. (4) to (7), there were obtained the in-plane (

ux) and out-of-plane (

uz) displacements for S0 and A0, which are presented in

Figure 5. The higher value of

uz for A0 mode, when compared to S0 mode, justify the high value of leakage attenuation observed in the

Figure 4.

4.2. Phase velocities and displacements in a bonded lap joint in water

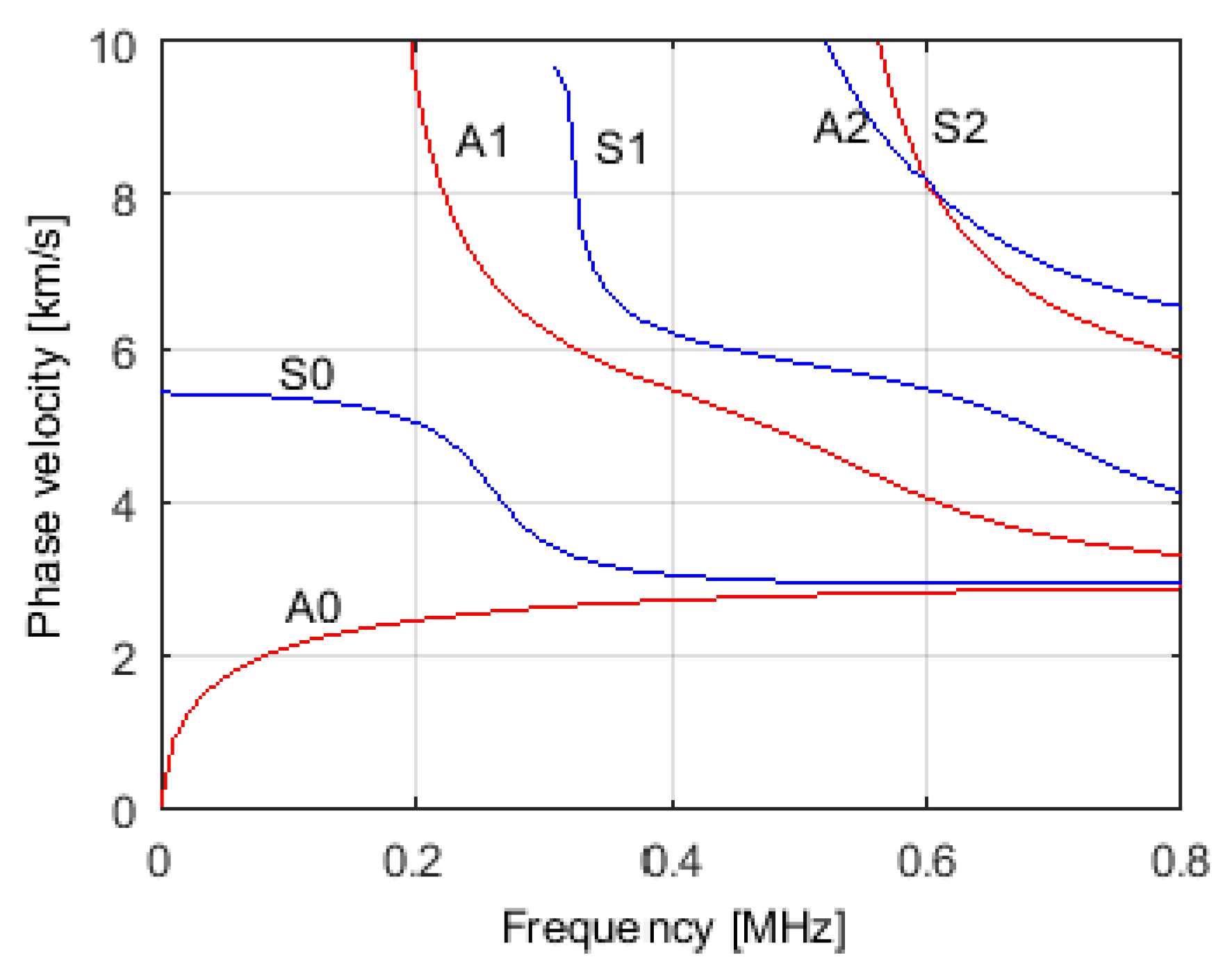

For the bonded region the transfer matrix method introduced in the

Section 2.2 was used to obtain the modal solutions of the matrix system. The real part of the solutions, which is the phase velocity of the different modes, is presented in

Figure 6.

The total thickness of the system is 8.15 mm (two 4 mm aluminium plates and 0.15 mm adhesive), so for the working frequency, four differences modes coexist: A0, S0, A1 and S1. The behavior is very similar to the previously obtained for the single plate, which is justified by the fact the system is mostly composed by aluminium with a very small amount of epoxy. The behavior difference characterizes by an increase of the number of propagation modes, which is related to the increase of the thickness. The attenuation values due to leakage for 500 kHz were obtained in the same way as previously for the single plate and are presented in

Table 2.

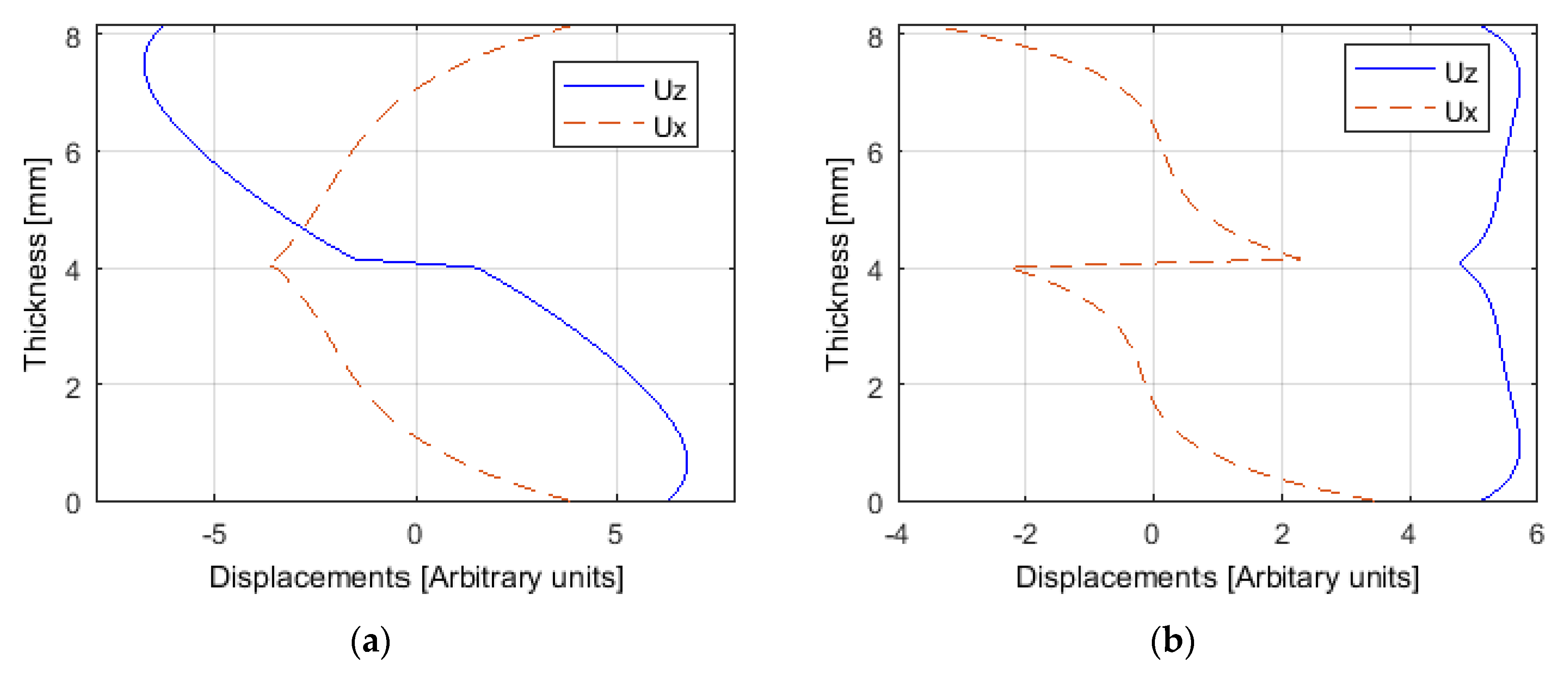

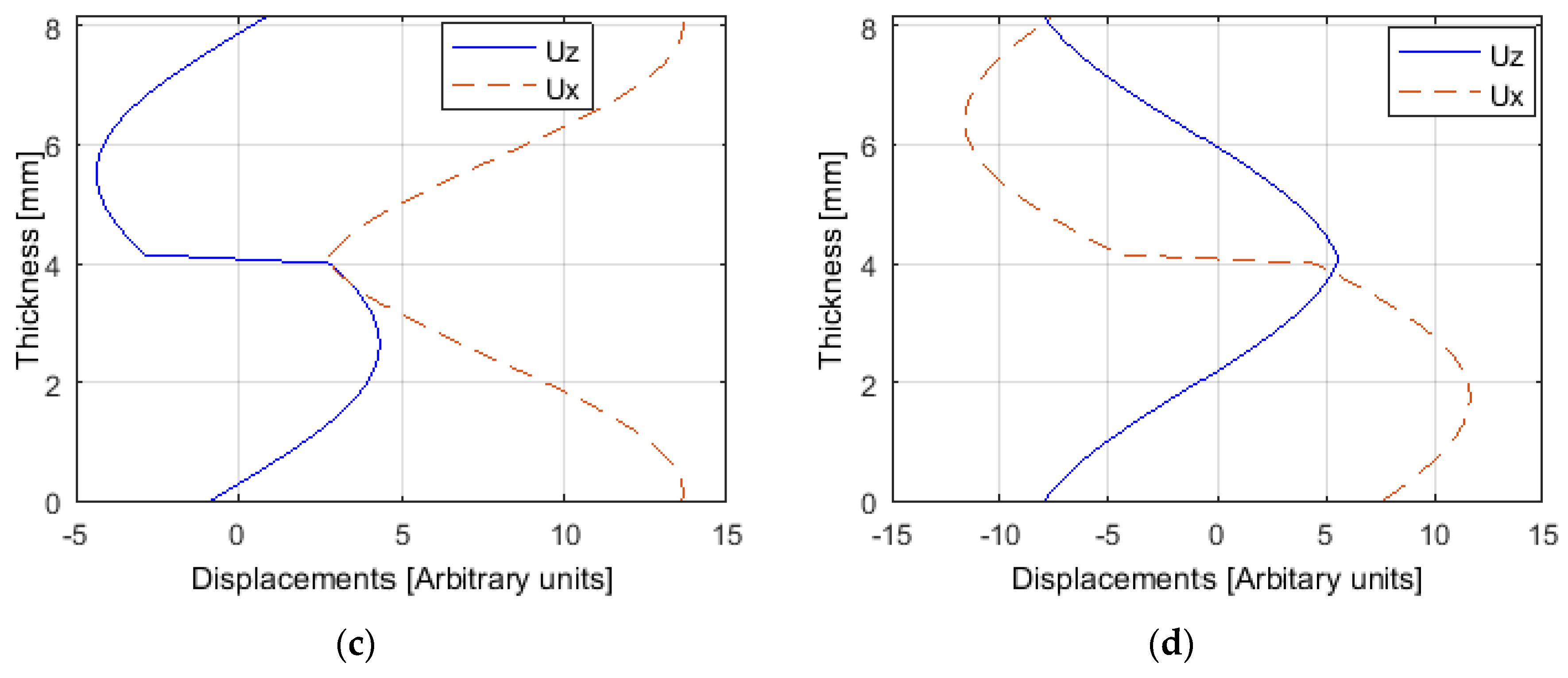

The displacements for the mentioned modes can be also obtained using the matrix method [

56]. Considering the boundary conditions for all interfaces, it is obtained a matrix composed by the amplitude coefficients for the three layers. As the system is immersed, there are two additional unknowns corresponding to the amplitude of longitudinal waves at the water bottom boundary and at the top boundary water. By solving the matrix system, the displacement values in arbitrary units as a function of the thickness were evaluated and are presented in

Figure 7. There is now a more complex pattern when compared with the single plate one, which is due to the epoxy adhesive layer. Looking at the displacements at the surface of the system, that are in contact with the water, the relation between the out-of-plane and in-plane values agrees with the attenuation values presented in

Table 2. For example, for the S1 mode the displacement is essentially in-plane, giving rise to extremely low attenuation values. For the A1 mode, the two types of displacements are similar, giving rise to already noticeable attenuation values. Finally, for A0 and S0 modes, the out-of-plane displacements are greater than the in-plane ones, leading to higher attenuations.

4.3. Guided waves propagation simulation

The k-Wave function used for the simulation is pstdElastic3D, based on the pseudo spectral time domain (PSTD) method, which is able to simulate the time-domain propagation of elastic waves through a three-dimensional homogeneous or heterogeneous medium [

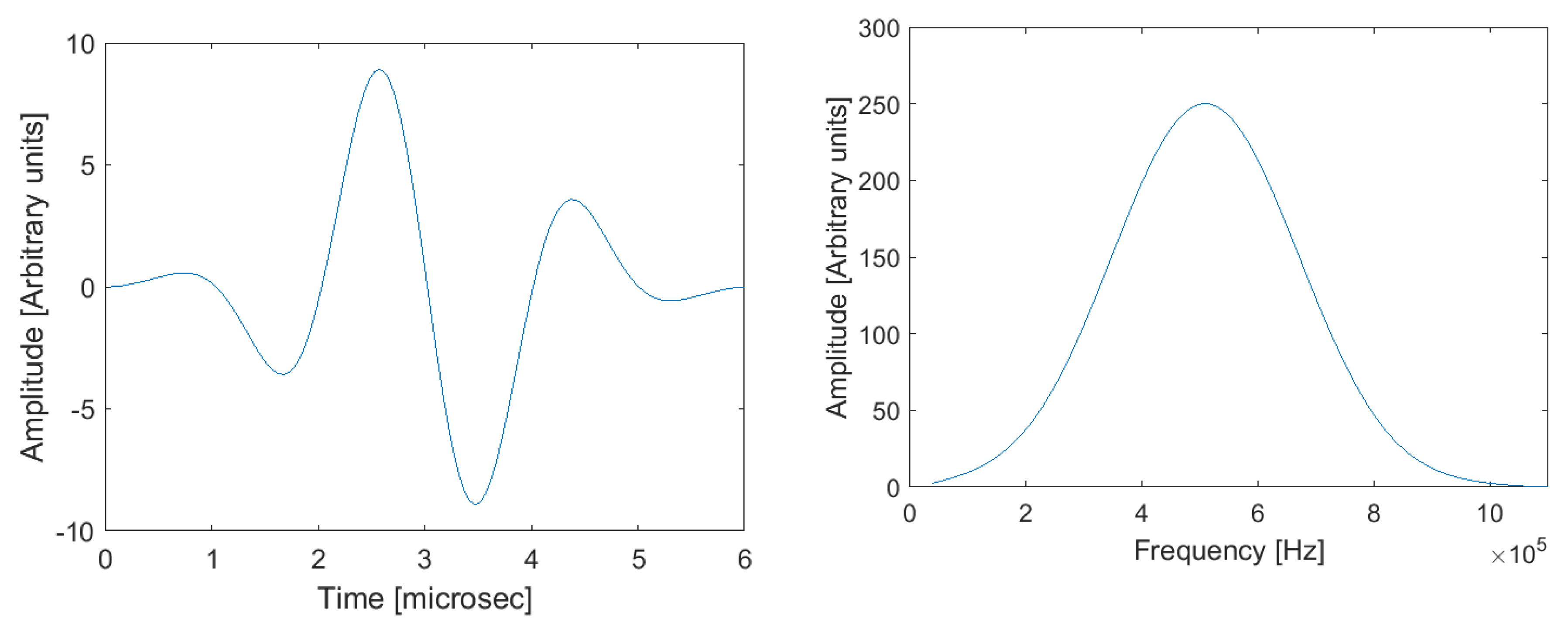

58]. The simulation model presented in section 2.3 was implemented in a computer with an Intel® Core™ i7-4790 processor and 16GB RAM, with a Nvidea GeForce GTX1080 Ti GPU, 11.26 GB RAM. For the available hardware and the presented geometry, the maximum resolution (minimum grid point spacing) was limited to 150 μm. This resolution gave rise to 21.47x106 voxels (840x213x120). The source was excited with a three-cycle burst, 500 kHz central frequency, as shown in

Figure 8 (a).

Figure 8 (b) illustrates the respective spectrum.

For model validation, first the propagation in an aluminium single plate was tested. For that purpose, the theoretical phase velocity extracted from

Figure 3 for 500 kHz was used in the Eq. (9). The resulting incident angle for S0 mode, which is the same as the receiving angle, is 18.2°.

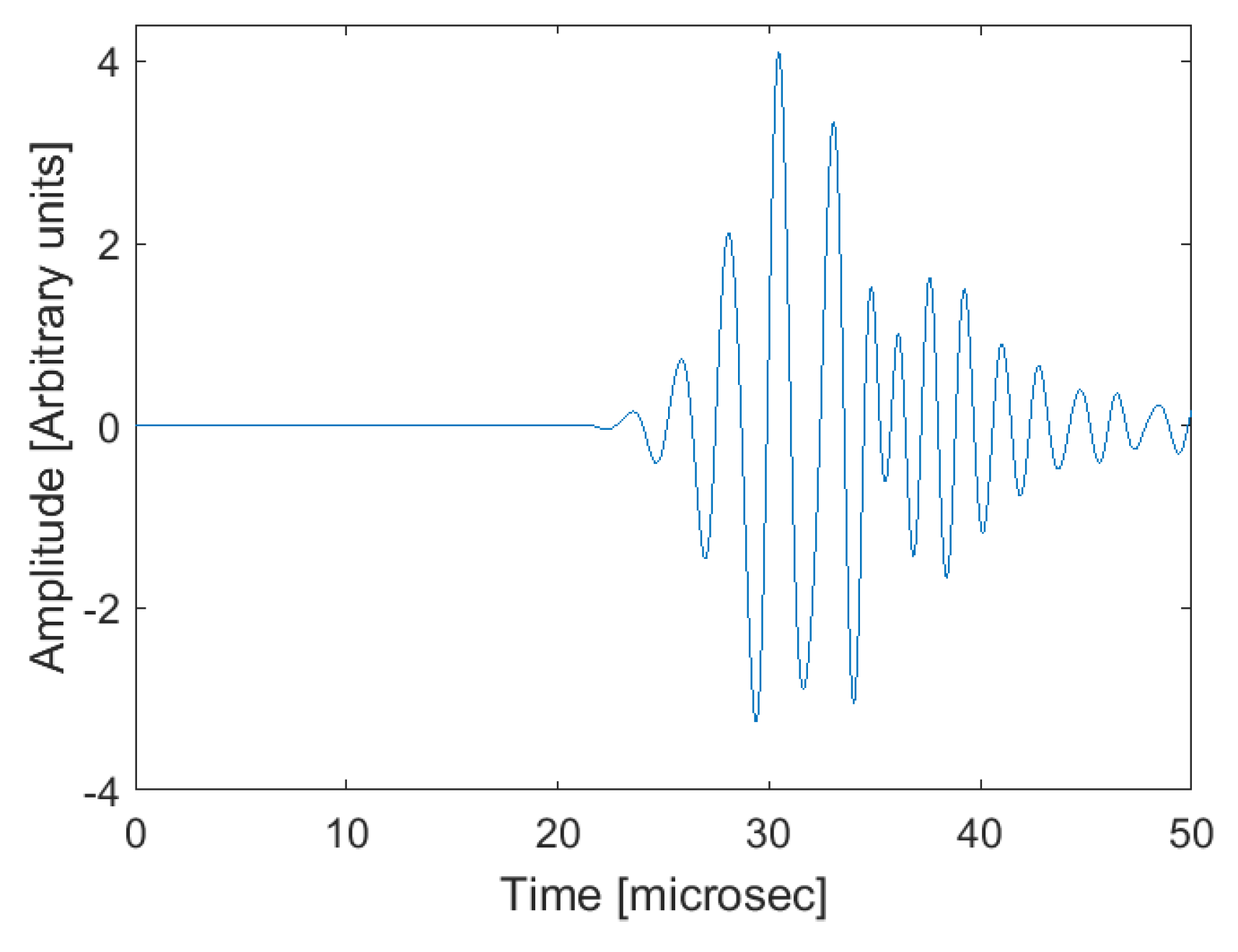

The signal collected at the receiver is presented in

Figure 9. It is observed an increase in the pulse length, due to the dispersion behavior of the S0 mode phase velocity, when compared with the original three cycle excitation burst (

Figure 8 (a)). Besides the direct signal propagated between the transmitter and the receiver, it is also observed an interference signal corresponding to the round trip in the water path at the emitter. To avoid that interference, the distance between the emitter transducer and the plate should be increased, however such was not possible in the present simulation by limited computational resources. Nevertheless, this fact has not prevented the peak-to-peak amplitude value from being correctly evaluated.

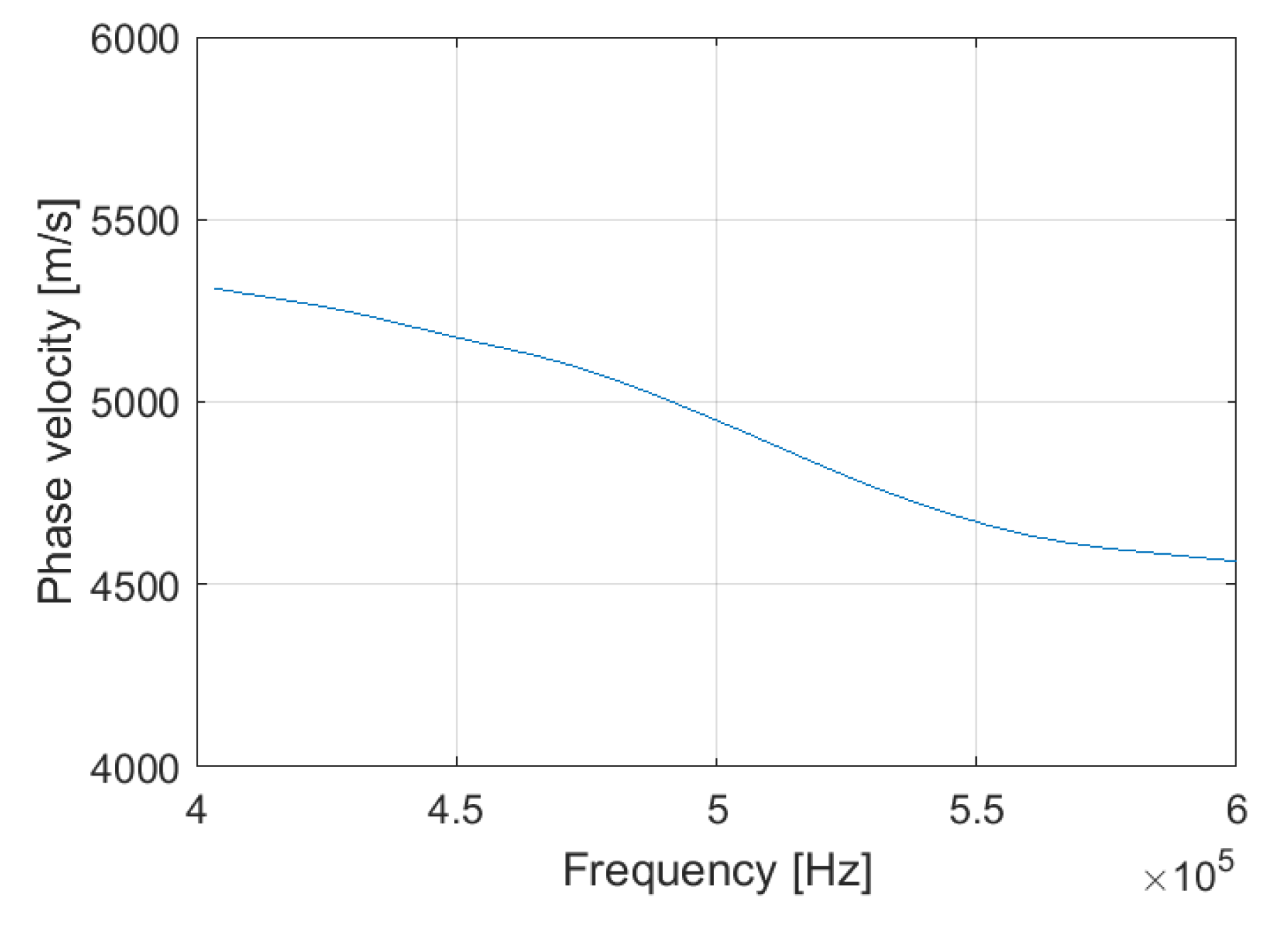

To confirm that the excited propagation mode is indeed S0, the phase velocity

was calculated through the phase spectrum approach [

56], as

where

f is the frequency,

L is the path difference between two collected signals, and Δϕ is the respective difference in the phase spectrum.

Figure 10 illustrates the phase velocity obtained by this method for L=20mm. There is a clear agreement between the presented phase velocity in

Figure 10 and the theoretical one shown in

Figure 3.

Comparing the peak-to-peak amplitudes of the two above mentioned signals, the attenuation was also computed, resulting in 27.5 Np/m. Again, this value is in full agreement with the theoretical one shown in

Figure 4.

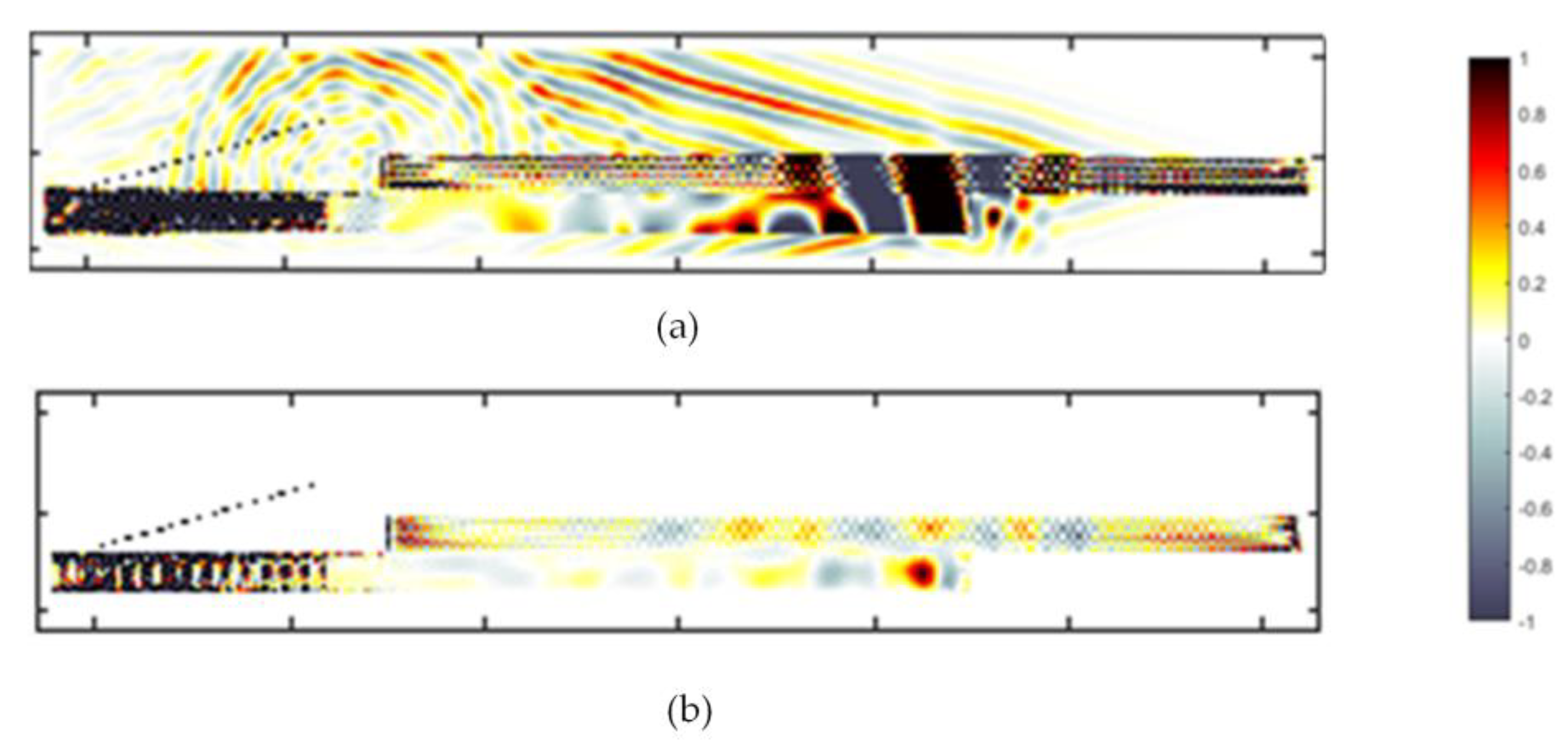

The same methodology was used to simulate the propagation of S0 mode in the aluminium bonded plates presented in the

Figure 1.

Figure 11 illustrates snapshots of the normal and shear stresses in the XZ plane during the simulation. The emitter transducer is represented by a dashed line on the left. It is clear the high stress values inside the plates. It is also evident the energy leakage surrounding the plates and the absence of shear stress in the water.

The received signal amplitudes corresponding to the propagation in a single plate and in the bonded plates obtained using the same test conditions, were compared. An amplitude decrease of about 10% was observed for the bonded plates compared with the single plate one, which can be justified by the higher attenuation values in the bonded region, when compared to the attenuation of S0 mode in a single plate. This high attenuation is related to the behavior of the existing modes in the bonded zone as result of mode conversion when the wave in the transmitter plate converts to one or more modes at the location where it first meets the adhesive layer. Those modes, which then travel in the bonded region are the natural modes (A0, S0, A1 and S1) of the three-layer system aluminium/adhesive/aluminium. Theoretically, it is expected that to excite a specific mode in the bonded zone, the mode shape in the bottom plate of the bonded zone should be similar to the mode shape in the single transmitter plate [

13,

59]. Comparing S0 displacement in the single plate (

Figure 5 (a)) with the natural modes in bonded plates (

Figure 7), it can be said that A1 and S1 modes has completely different shapes, so their amplitude should be very low. The same comparison was made with A0 and S0 mode shapes. Now, despite not being perfectly equal, they have great similarities with S0 in the transmitter plate, which allows saying that these are the dominant modes in the bonded zone. As the mode shape in the bottom plate of the bonded zone is more or less the same for A0 and S0, it can be admitted the same conversion degree for both modes, and using data of

Table 2 the average attenuation is 30 Np/m. This value is higher than the one for the single plate, which justify the smaller amplitude measured in the bonded plates.

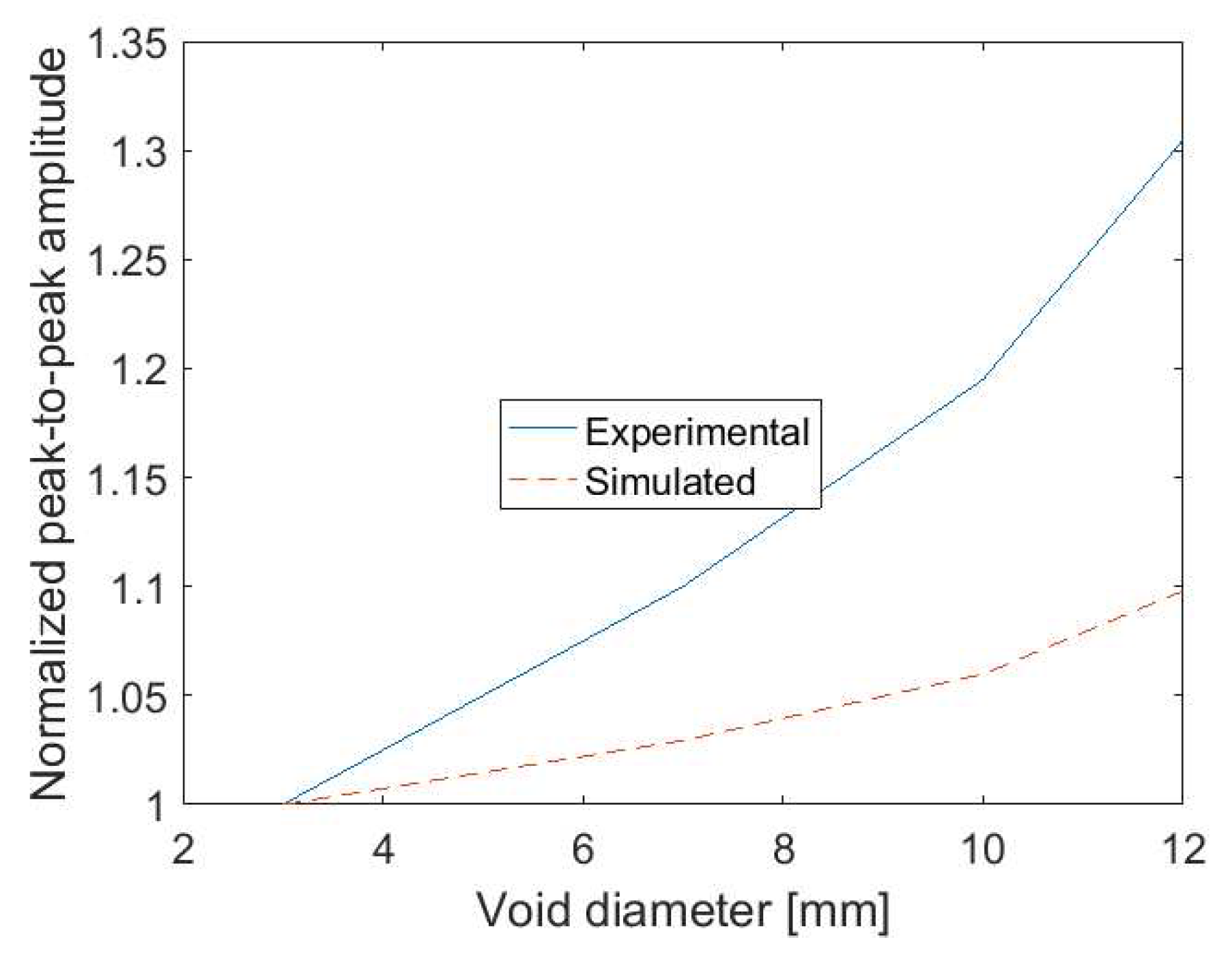

To evaluate the presence of voids and its influence in the received signal, round air defects (bubbles) with different diameters were simulated, characterizing the absence of the adhesive component between the plates.

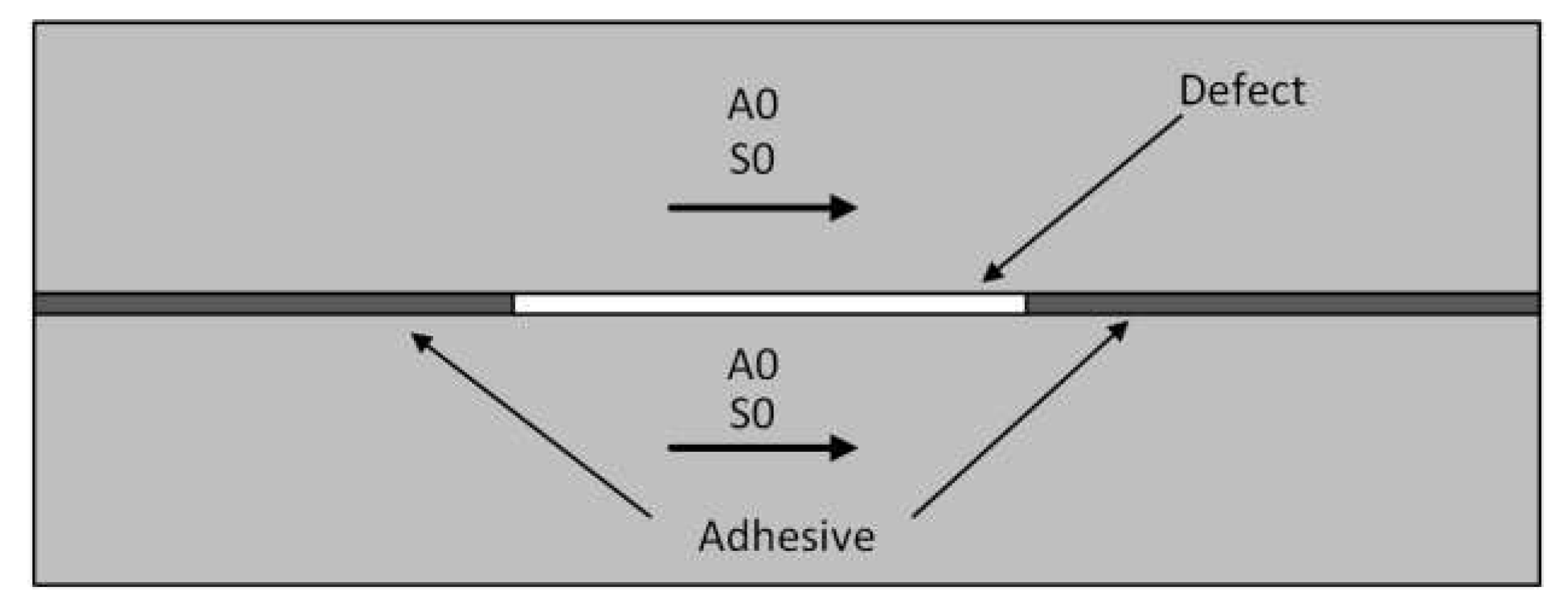

Figure 12 presents the peak-to-peak amplitude of the receiving signal as a function of void dimensions, normalized with respect to the small void considered (3mm). There is a signal amplitude increase with the void dimensions. The justification for this behavior can be explained because in the presence of a defect, the dominant modes that exist in the bonded joint give rise to additional modes (by mode conversion) that propagates around the defect. In this case this zone could be considered as two isolated semi-immersed plates (at one side there is water and at the other side there is air) where only A0 and S0 mode are allowed to propagate.

Figure 13 describes schematically this situation. So, the propagation in the defective bonded joint this zone is similar to the observed in a single plate, and two phenomena contribute to the increase of amplitudes as the defect size increase: (a) as shown previously, the attenuation in the single plate is lower than in the bonded plates, (b) and as one side of the plate is in contact with air, the leakage is half of the verified when the plate is immersed. The experimental results are also presented in the

Figure 12. Qualitatively there is reasonable agreement between the simulated and experimental. The observed deviation can be due to the different characteristics of the experimental and simulated defects, which inevitably do not have the same scattering effects.

5. Discussion

In this work the authors present an analytical, simulated, and experimental study about the behavior of ultrasound guided waves propagating in a single plate and in two plates of aluminium, bonded by an epoxy adhesive layer. Both configurations were immersed in water.

For a single plate, a classical iterative optimization algorithm was used to solve the complex dispersion equations in order to obtain the phase velocity, the leakage attenuation and the displacement curves of each propagation mode. It was verified that the high out-of-plane displacement values in the plate surfaces give rise to high attenuation values. For the bonded plates the transfer matrix method was used to obtain the same parameters above. Similar correlations between attenuation and out-of-plane displacements were obtained, as the ones for the single plates. A 3D simulation using the k-Wave MATLAB toolbox was implemented and the results proved its effectiveness to characterize the propagation of guided waves in single and bonded structures, concerning to the correct excitation of a certain mode, and the phase velocity and attenuation measurements. Simulated and experimental air voids with different dimensions were produced in the adhesive region of the bonded joint. An increase in the amplitude of the received signal was observed as the defect size also increased for both simulated and experimental approaches. That behavior is justified by the fact the defective region can be considered as a single plate with lower attenuation, in terms of guided waves propagation. Also, as only one plate surface is in contact with water (the other one is in contact with air), the leakage to water is smaller. The experimental results are in qualitative agreement with the simulated ones. The deviation is related to the inevitable impossibility to reproduce the same defects exactly in simulation and experimental.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.S. and J.S.; methodology, M.S. and J.S.; software, M.S.; validation, M.S. and J.S.; formal analysis, M.S. and J.S.; investigation, M.S. and J.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.S.; writing—review and editing, M.S. and J.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

This research is sponsored by national funds through FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, under the project UIDB/00285/2020 and LA/P/0112/2020.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adams, R.D.; Drinkwater, B.W. Nondestructive testing of adhesively-bonded joints. NDT&E 1997, 30, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allin, J.M.; Cawley, P.; Lowe, M.J. Adhesive disbond detection of automotive components using first mode ultrasonic resonance. NDT&E 2003, 36, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansfield, T.L. Lamb wave inspection of aluminium sheet. Mater Eval 1975, 33, 96–100. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, D.F.; Shewring, D. Some problems in the use of Lamb waves for the inspection of cold-rolled steel sheet coil. Nondestruct Test 1976, 39, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alleyne, D.N.; Cawley, P. Optimization of Lamb wave inspection techniques. NDT&E 1992, 25, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alleyne, D.N.; Cawley, P. The interaction of Lamb waves with defects. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control 1992, 39, 381–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.; Alers, G.; Tennison, M. Application of direct electromagnetic Lamb wave in generation to gas pipeline inspection. In: IEEE Ultrasonic symposium proceedings, NY, USA, 1972. [CrossRef]

- Rose, J.L.; Jiao, D.; Spanner, J. Ultrasonic guided wave NDT for piping. Mater Eval 1996, 54, 1310. [Google Scholar]

- Quarry, M.; Rose, J.L. Multimode guided wave inspection of piping using comb transducers. Mater Eval 1999, 57, 1089–1090. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, Y.; Kundu, T.; Ehsani, M. Internal discontinuity detection in concrete by Lamb waves. Mater Eval 2001, 59, 418–423. [Google Scholar]

- Rokhlin, S. Lamb wave interaction with lap-shear adhesive joints: Theory and experiment. J Acoust Soc Am 1991, 89, 2758–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, J.L.; Rajana, K.M.; Hansch, M.K.T. Ultrasonic guided waves for NDE of adhesively bonded structures. J Adhes 1995, 50, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, M.J.S.; Challis, R.E.; Chan, C.W. The transmission of Lamb waves across adhesively bonded lap joints. J Acoust Soc Am 2000, 107, 1333–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Scalea, F.L.; Bonomo, M.; Tuzzeo, D. Ultrasonic guided wave inspection of bonded lap joints: Noncontact method and photoelastic visualization. J Res Nondestruct Eval 2001, 13, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rokhlin, S.I.; Xie, B.; Baltazar, A. Quantitative ultrasonic characterization of environmental degradation of adhesive bonds. J Adhes Sci Technol 2004, 18, 327–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baiyang, R.C.; Lissenden, J. Ultrasonic guided wave inspection of adhesive bonds between composite laminates. International Journal of Adhesion and Adhesives 2013, 45, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matt, H.; Bartoli, I.; Di Scalea, F.L. Ultrasonic guided wave monitoring of composite wing skin-to-spar bonded joints in aerospace structures. J Acoust Soc Am 2005, 118, 2240–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gauthier, C.; El-Kettani, M.; Galyc, J.; Predoi, M.; Leduc, D.; Izbicki, J. Lamb waves characterization of adhesion levels in aluminum/epoxy bi-layers with different cohesive and adhesive properties. International Journal of Adhesion and Adhesives 2017, 74, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, B.; Asokkumar, A.; Jasiunien, E.; Kažys, R. Air-Coupled, Contact, and Immersion Ultrasonic Non-Destructive Testing: Comparison for Bonding Quality Evaluation. Appl Sci 2020, 10, 6757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, N.; Wakabayashi, D.; Hayashi, T. Tangential bond stiffness evaluation of adhesive lap joints by spectral interference of the low-frequency A0 lamb wave. International Journal of Adhesion and Adhesives 2022, 113, 103071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucka, M.; Wojtczak, E.; Lachowicz, J. Damage Imaging in Lamb Wave-Based Inspection of Adhesive Joints. Appl Sci 2018, 8, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wojtczak, E.; Rucka, M. Wave Frequency Effects on Damage Imaging in Adhesive Joints Using Lamb Waves and RMS. Materials 2019, 12, 1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicassio, F.; Carrino, S.; Scarselli, G. Elastic waves interference for the analysis of disbonds in single lap joints. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing 2019, 128, 340–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicassio, F.; Carrino, S.; Scarselli, G. Non-linear Lamb Waves for Locating Defects in Single-Lap Joints. Front Built Environ Sec. Computational Methods in Structural Engineering 2020, 6, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Liu, M.; Su, Z.; Guo, S.; Cui, F. Mode-mismatching enhanced disbond detection using material nonlinearity in guided waves at low frequency. Journal of Sound and Vibration 2021, 490, 115733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrino, S.; Nicassio, F.; Scarselli, G.; Vitolo, R. Finite difference model of wave motion for structural health monitoring of single lap joints. International Journal of Solids and Structures 2019, 161, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moria, N.; Kusaka, T. Reflection and transmission characteristics of Lamb waves at an adhesive lap joint of plates. J Acoust Soc Am 2019, 145, 3075–3085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Chen, S.; Wong, Z.; Yao, K.; Cui, F. In situ disbond detection in adhesive bonded multi-layer metallic joint using time-of-flight variation of guided wave. Ultrasonics 2020, 102, 106062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, D.; Le Duff, A.; Painchaud-April, G.; Belanger, P. Simulation-Based Inversion for the Characterization of Adhesively Bonded Joints Using Ultrasonic Guided Waves. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control 2022, 69, 2400–2407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treeby, B.; Cox, B. k-Wave: MATLAB toolbox for the simulation and reconstruction of photoacoustic wave-fields. J Biomed Opt 2010, 15, 021314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treeby, B.; Jaros, J.; Rendell, A.; Cox, B. Modeling nonlinear ultrasound propagation in heterogeneous media with power law absorption using a k-space pseudospectral method. J Acoust Soc Am 2012, 131, 4324–4336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Teoh, E.; Jaros, J.; Treeby, B. Modelling nonlinear ultrasound propagation in absorbing media using the k-Wave toolbox: Experimental validation. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium, Dresden, Germany, 7–10 October 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Liva, M.; Herraiz, J.; Udías, J.; Miller, E.; Cox, B.; Treeby, B. Time domain reconstruction of sound speed and attenuation in ultrasound computed tomography using full wave inversion. J Acoust Soc Am 2017, 141, 1595–1604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; McGougha, R. Time-domain analysis of power law attenuation in space-fractional wave equations. J Acoust Soc Am 2018, 144, 467–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almansourin, H.; Venkatakrishnan, S.; Bouman, C.; Santos-Villalobos, H. Model-Based Iterative Reconstruction for One-Sided Ultrasonic Nondestructive Evaluation. IEEE Trans Comput Imaging 2019, 5, 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsui, K.; Azuma, T.; Fujiwara, K.; Takeuchi, H.; Itani, K.; Wang, J.; Sakuma, I. Improving high-intensity focused ultrasound beam imaging via a backscattering suppression algorithm. Jpn J Appl Phys 2017, 56, 57301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acquaticci, F.; Guarracino, J.; Gwirc, S.; Lew, S. A polydimethylsiloxane-based axicon lens for focused ultrasonic brain stimulation techniques. Acoust Sci Technol 2019, 40, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui,W. ; Qin, K. Fast 3-D Ultrasonic Imaging Using Time-Domain Synthetic Aperture Focusing Techniques Based on Circular Scan Conversions. IEEE Trans Comput Imaging 2018, 4, 632–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrella, L.; Perdigão, F.; Caixinha, M.; Santos, M.; Lopes, M.; Gomes, M.; Santos, J. A-scan ultrasound in ophthalmology: A simulation tool. Med Eng Phys 2021, 97, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.; Santos, J.; Petrella, L. Computational simulation of microflaw detection in carbon-fiber-reinforced polymers. Electronics 2022, 11, 2836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brill, T.; Klieber, C. Reflection and mode-conversion of ultrasonic leaky Lamb waves at inaccessible discontinuities in layered structures. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium, Tours, France, 18–21 September 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klieber, C.; Brill, T. Mapping of ultrasonic Lamb-wave field in elastic layered structures using laser probes. In Proceedings of the 173rd Meeting of Acoustical Society of America and 8th Forum Acusticum, Boston, MA, USA, 25–29 June 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viktorov, A. Rayleigh and Lamb Waves—Physical Theory and Applications, Plenum, New York, USA, 1967, pp. 117–118.

- Rose, J. Ultrasonic Waves in Solid Media, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 1999, pp.113-115. [CrossRef]

- Cawley, P.; Alleyne, D. The Use of Lamb Waves for the Long Range Inspection of Large Structures. Ultrasonics 1996, 34, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carboni, M.; Gianneo, A.; Giglio, M. A Lamb Waves Based Statistical Approach to Structural Health Monitoring of Carbon Fibre Reinforced Polymer Composites. Ultrasonics 2015, 60, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.; Perdigão, J. Leaky Lamb waves for the detection and sizing of defects in bonded aluminium lap joints. NDT&E Int 2005, 38, 561–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimenti, D.; Rokhlin, S. Relationship between leaky Lamb modes and reflection coefficient zeroes for a fluid-coupled elastic layer. J Acoust Soc Am 1990, 88, 1603–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, A.; Lowe, M.; Deschamps, M. Guided waves energy velocity in absorbing and non-absorbing plates. J Acoust Soc Am 2001, 110, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haskell, N. Dispersion of surface waves on multilayered media. Bull Seismol Soc Am 1953, 43, 17–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, M. Matrix techniques for modeling ultrasonic waves in multilayered media. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control 1995, 42, 525–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Rokhlin, S. Stable reformulation of transfer matrix method for wave propagation in layered anisotropic media. Ultrasonics 2001, 39, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.; Xu, Y. A modified transfer matrix method for prediction of transmission loss of multilayer acoustic materials. J Sound Vib 2009, 326, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, J. Ultrasonic Guided Waves in Solid Media. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, 2014, pp. 227–230. [CrossRef]

- Armin, H.; Sause, M. Classification of solutions for guided waves in anisotropic composites with large numbers of layers. J Acoust Soc Am 2018, 144, 3236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.; Faia, P. Propagation of Ultrasonic Lamb Waves in Aluminium Adhesively Bonded Lap Joints and in Single Plates. Res Nondestruct Evaluation 2009, 20, 178–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krautkramer, J.; Krautkramer, H. Ultrasonic Testing of Materials, Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg GmbH, 1990, pp. 561. [CrossRef]

- Treeby, B.; Wise, E.; Cox, B. Nonstandard Fourier Pseudospectral Time Domain (PSTD) Schemes for Partial Differential Equations. Commun Comput Phys 2018, 24, 623–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auld, B.; Kino, G. Normal mode theory for acoustic waves and its application to the interdigital transducer. IEEE Trans Electron Devices 1971, 18, 898–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).