Submitted:

23 March 2023

Posted:

27 March 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

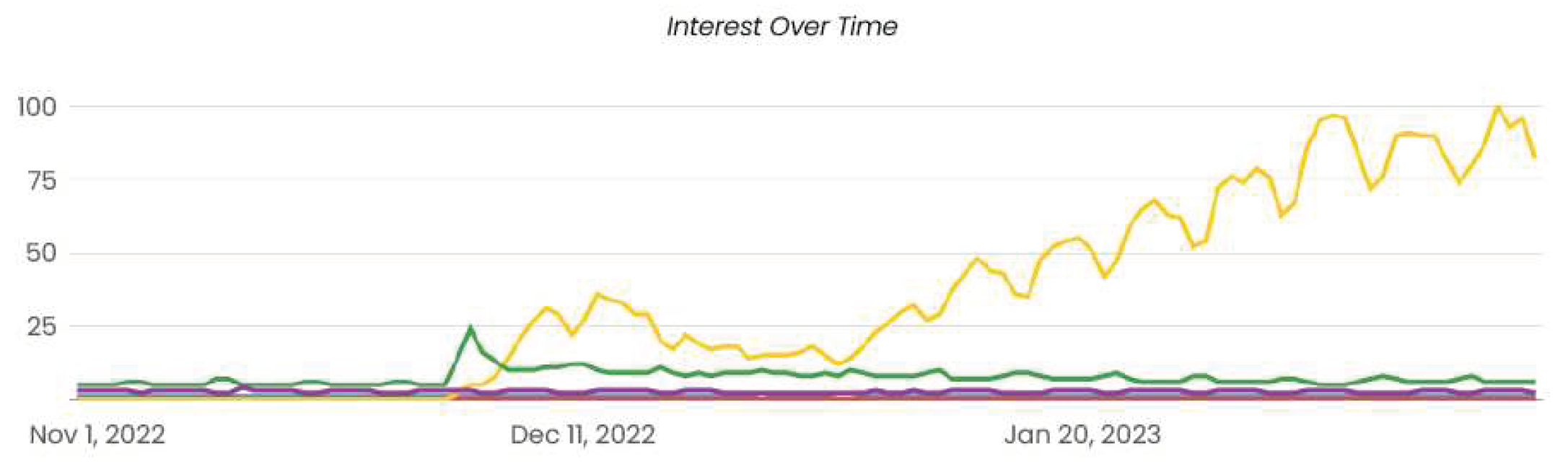

1.1. Why ChatGPT Became Popular?

- Limited context awareness: typical chatbot systems are trained on a limited context that serves the business requirements, such as customer service or e-commerce. This can limit their understanding capabilities and result in unsatisfying interactions for users. Furthermore, within the same context, these chatbots may struggle to address user queries if the intent is unclear enough to the engine due to limited pre-programmed rules and responses. This usually leads to unsatisfying interactions with users’ experience. However, ChatGPT has demonstrated superior performance compared to existing chatbots in its ability to understand broad contexts in natural language conversations. Its advanced language model allows it to analyze and interpret the meaning behind user queries, leading to more accurate and satisfying responses.

- Limited scale: Another limitation of traditional chatbot systems is their limited scale. These systems are typically trained on a relatively small amount of data related to the context of operation due to the high cost of data labeling and training for large data sizes. In contrast, ChatGPT has overcome these barriers by being trained on a massive amount of data from the internet, with a size of 570GB. This large-scale language model used in ChatGPT allows it to generate human-like responses that can mimic the tone, style, and humor of a human conversation. Traditional chatbots often provide robotic and impersonal responses, which can lead to unsatisfactory interactions with users. However, ChatGPT’s advanced language model and large-scale training allow it to generate more natural and engaging responses.

- Limited text generation ability: Traditional chatbot systems often lack the flexibility and adaptability required to handle complex and dynamic natural language understanding and generation. They often rely on pre-written intents, responses, or templates, leading to repetitive, predictable, or irrelevant answers that fail to engage users or meet their needs. Moreover, they struggle to generalize to new, unseen data, limiting their usefulness in real-world scenarios where the topics and contexts can vary widely. In contrast, ChatGPT leverages a powerful transformer architecture and a massive amount of training data to generate high-quality and diverse text outputs that closely resemble human language. By learning patterns and relationships between words and phrases from various sources, ChatGPT can capture the nuances and subtleties of different domains and produce relevant and coherent responses even to open-ended or ambiguous queries.

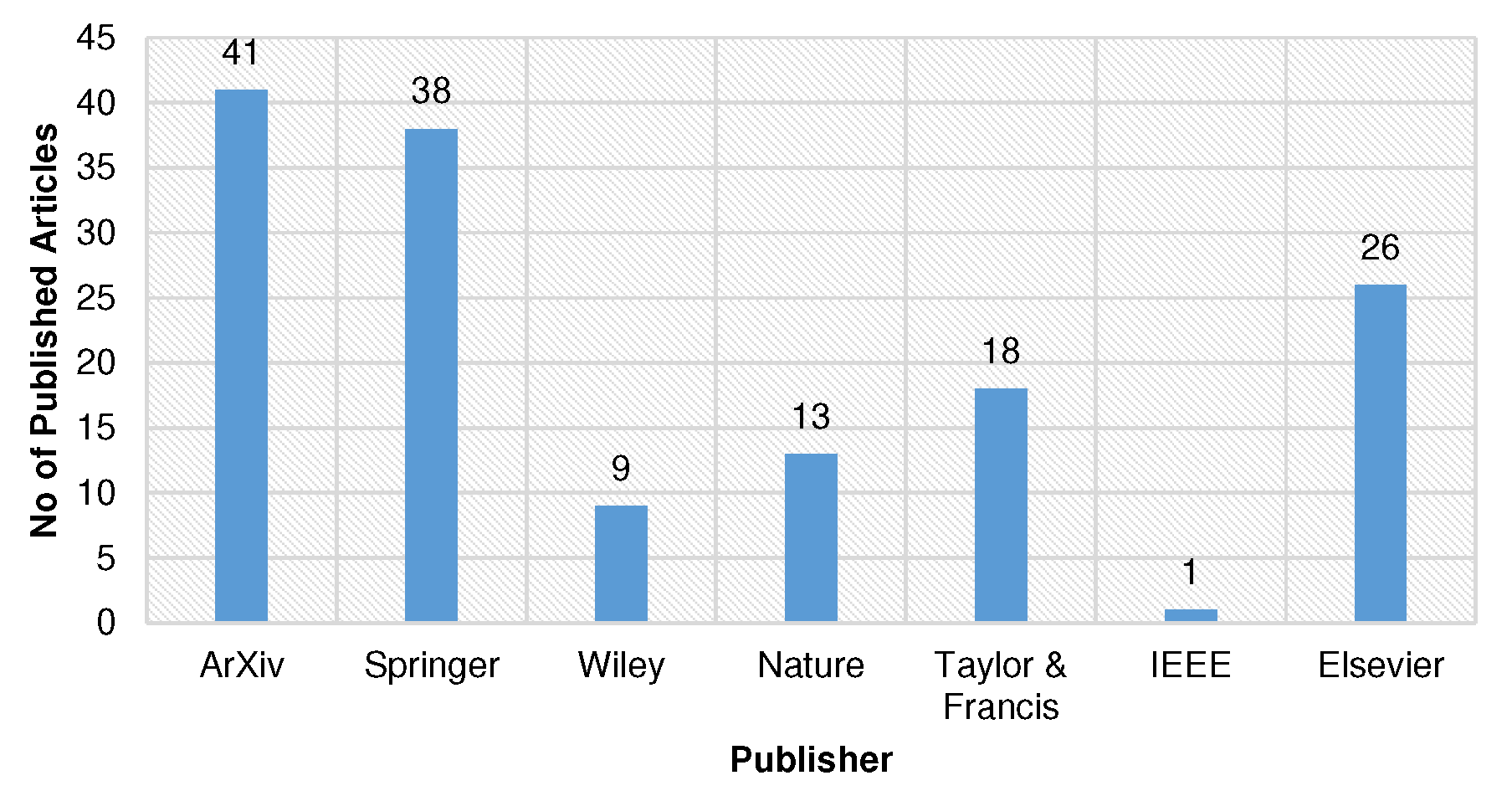

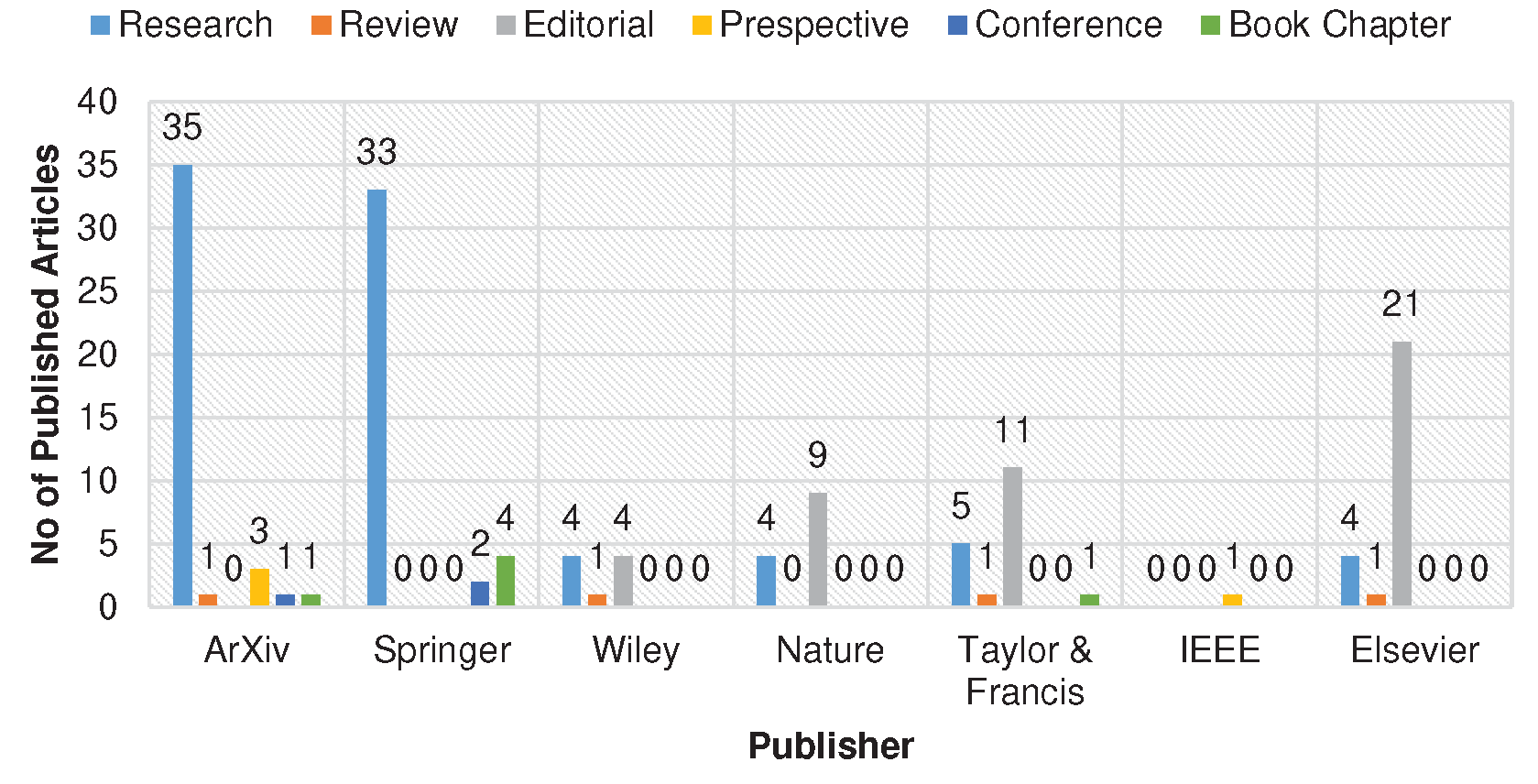

1.2. Related Surveys

1.3. Contributions and Research-Structure

- We provide an in-depth analysis of the technical advancements and innovations that distinguish ChatGPT from its predecessors, including generative models and chatbot systems. This analysis elucidates the underlying mechanisms contributing to ChatGPT’s enhanced performance and capabilities.

- We develop a comprehensive taxonomy of recent ChatGPT research, classifying studies based on their application domains. This classification enables a thorough examination of the contributions and limitations present in the current literature. Additionally, we conduct a comparative evaluation of emerging ChatGPT alternatives, highlighting their competitive advantages and drawbacks.

- We identify and discuss the limitations and challenges associated with ChatGPT, delving into potential areas of improvement and unexplored research opportunities. This discussion paves the way for future advancements in the field, guiding researchers and practitioners in addressing the current gaps in ChatGPT research and applications.

2. Background and Main Concepts

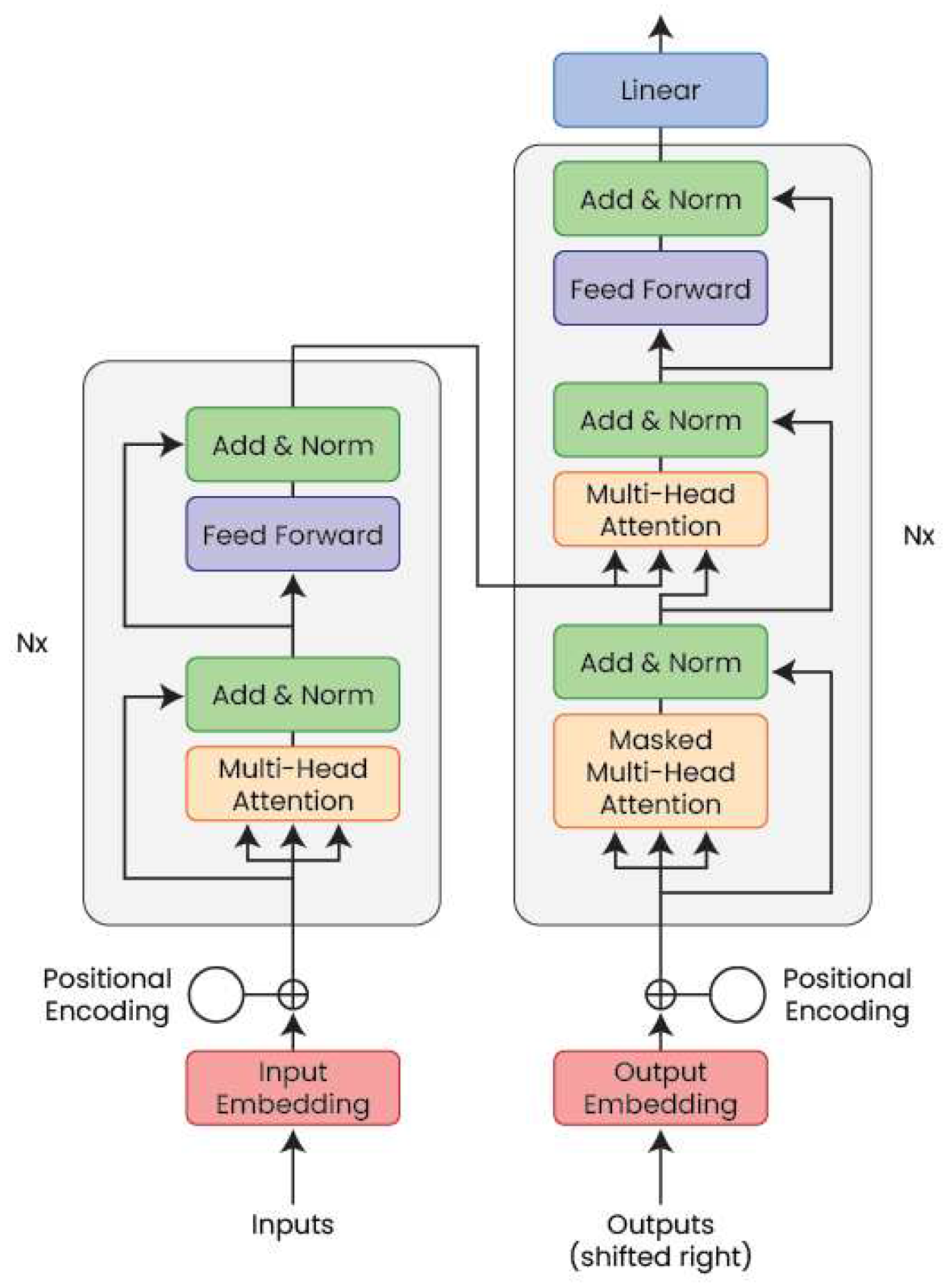

2.1. GPT-3 Model: Leveraging Transformers

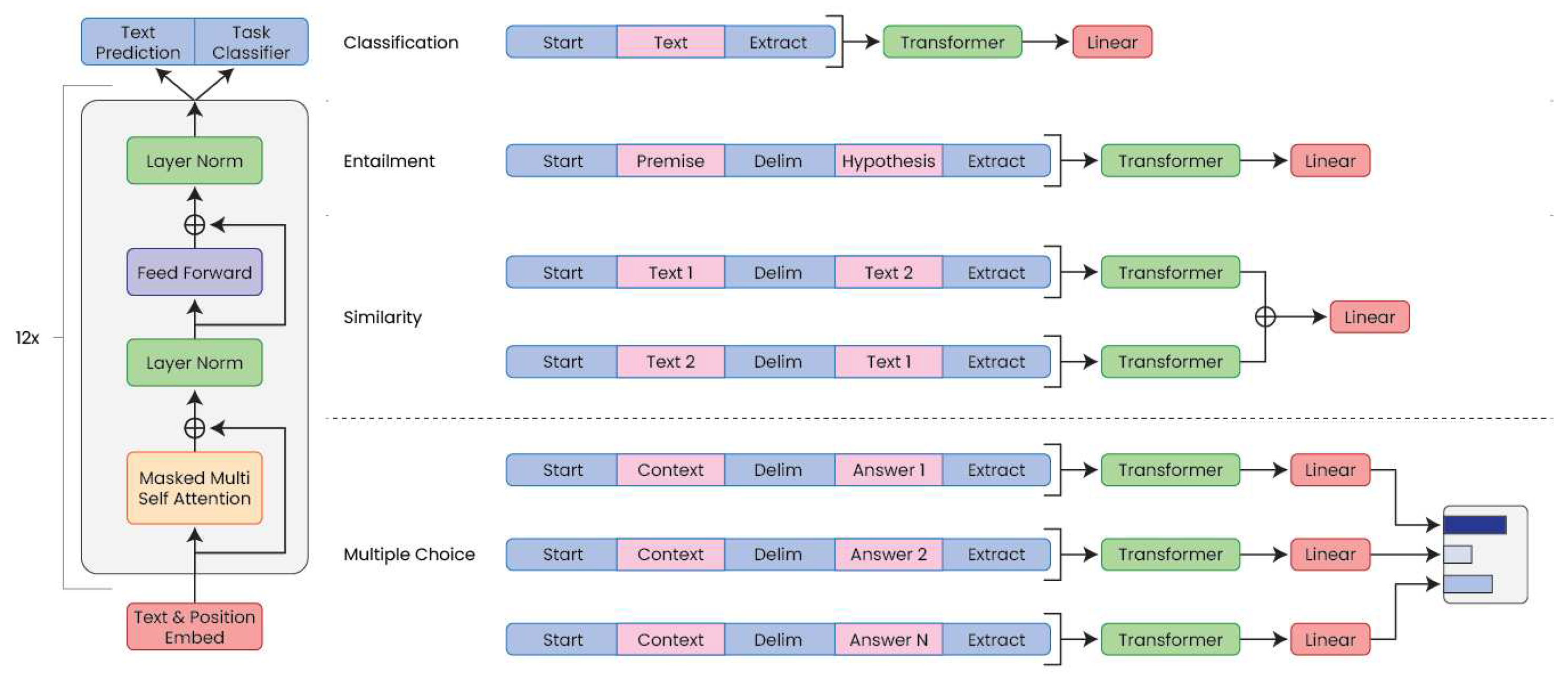

2.1.1. Transformers as Core Technology

2.1.2. Encoder-Decoder Architecture

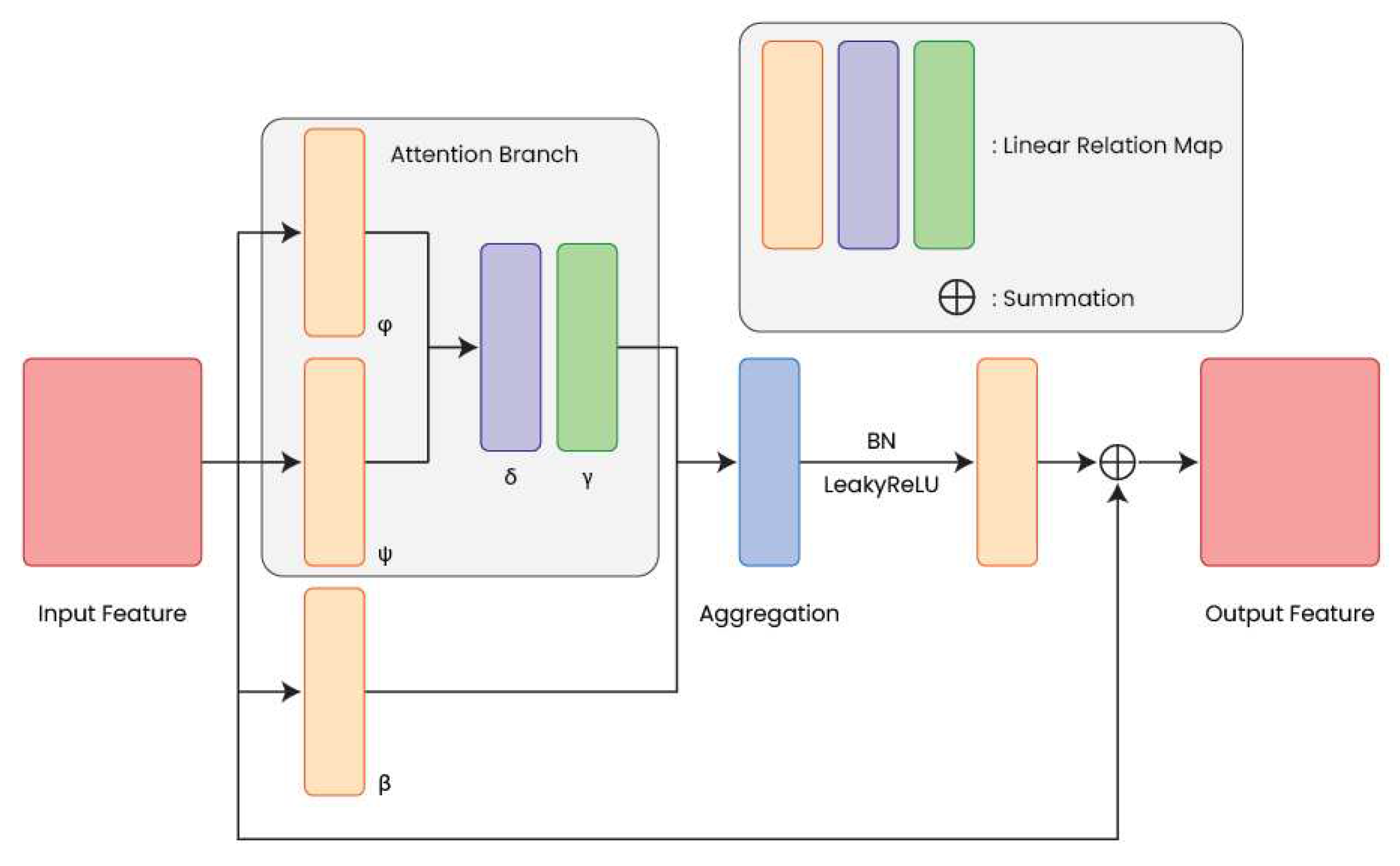

2.1.3. Self-Attention Module

- The Query (Q): This vector represents a single token (e.g., word embedding) in the input sequence. This token is used as a query to measure its similarity to all other tokens in the input sequences, equivalent to a document in an information retrieval context.

- The Key (K):This vector represents all other tokens in the input sequence apart from the query token. The key vectors are used to measure the similarity to the query vector.

- The Value (V): This vector represents all tokens in the input sequence. The value vectors are used to compute the weighted sum of the elements in the sequence, where the weights are determined by the attention weights computed from the query and key vectors through a dot-product.

| Algorithm 1: Self-Attention Module with Mask |

|

Require: Q, K, and V matrices of dimensions , , and , respectively Ensure: Z matrix of dimension Step 1: Compute the scaled dot product of Q and K matrices: Step 2: Apply the mask to the computed attention scores (if applicable): if mask is not None then {Element-wise multiplication} end if Step 3: Compute the weighted sum of V matrix using A matrix as weights: Step 4: Return the final output matrix Z. |

2.1.4. Multi-Head Attention

2.1.5. Positional Embedding

| Model Name | No. of Params | No. of Layers | Embedding Size | No. of Heads | Head Size | Batch Size | Learning Rate |

| GPT3-Small | 125M | 12 | 768 | 12 | 64 | 0.5M | 6.0 × 10−4 |

| GPT3-Medium | 350M | 24 | 1024 | 16 | 64 | 0.5M | 3.0 × 10−4 |

| GPT3-Large | 760M | 24 | 1536 | 16 | 96 | 0.5M | 2.5 × 10−4 |

| GPT3-XL | 1.3M | 24 | 2048 | 24 | 128 | 1M | 2.0 × 10−4 |

| GPT3-2.7B | 2.7B | 32 | 2560 | 32 | 80 | 1M | 1.6 × 10−4 |

| GPT3-6.7B | 6.7B | 32 | 4096 | 32 | 128 | 2M | 1.2 × 10−4 |

| GPT3-13B | 13B | 40 | 5140 | 40 | 128 | 2M | 1.0 × 10−4 |

| GPT3-175B | 175B | 96 | 12288 | 96 | 128 | 3M | 0.6 × 10−4 |

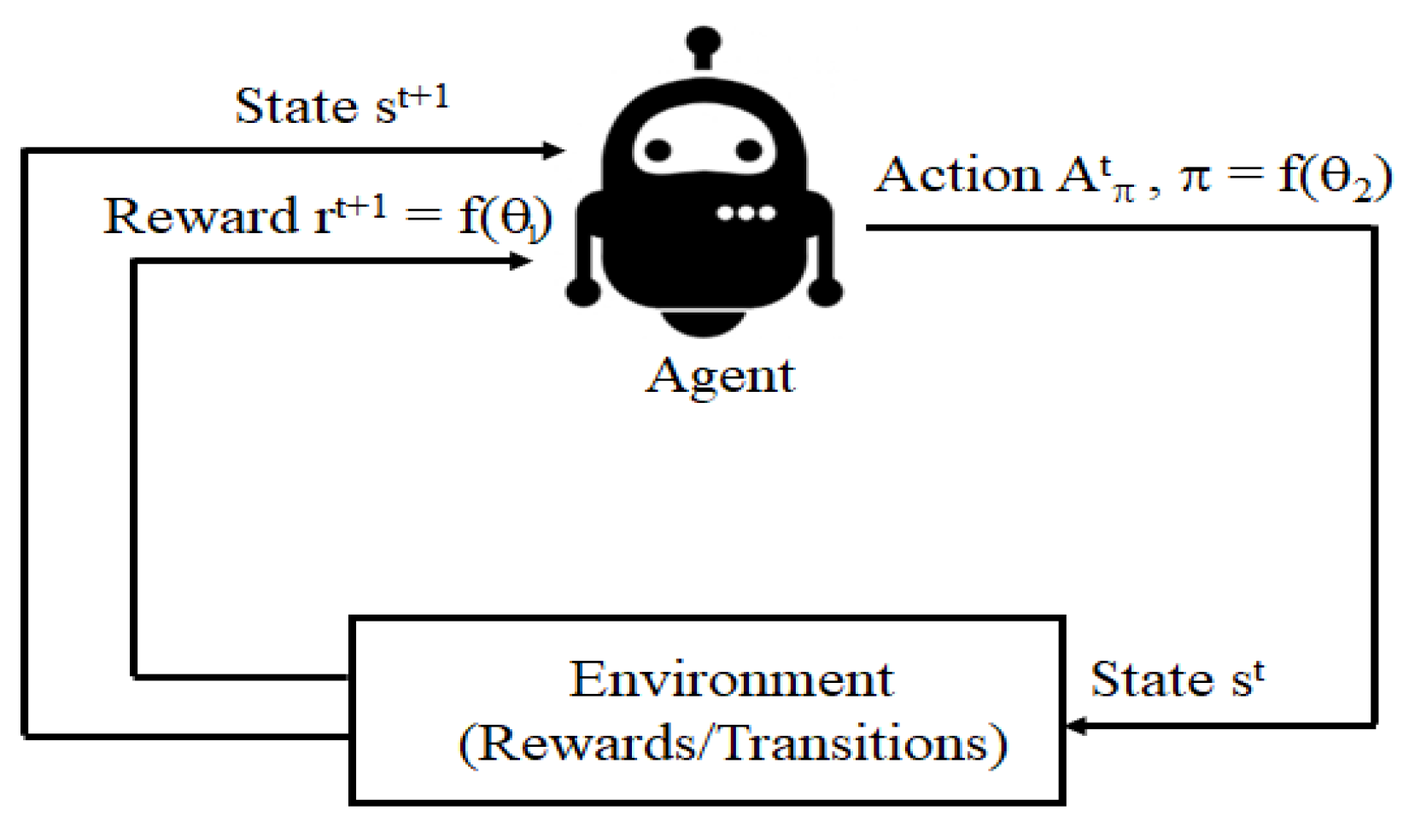

2.2. From GPT3 to InstructGPT: : Leveraging Reinforcement Learning

2.2.1. Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback (RLHF)

- : Set of states where each state, , "encodes" the environment (i.e., the user prompts and agent completions).

- : Set of actions that the dialogue agent can take at any step t by generating a new prompt completion.

- : Transition probabilities when taking action at state to reach state .

- : Reward achieved when taking action to transition from to . When fine-tuning dialogue agents, it is a common practice to assume the rewards independent of the actions.

- : Discount (or forgetting) factor set to a positive number smaller than 1. For simplicity, can be fixed to a typical value such as ..

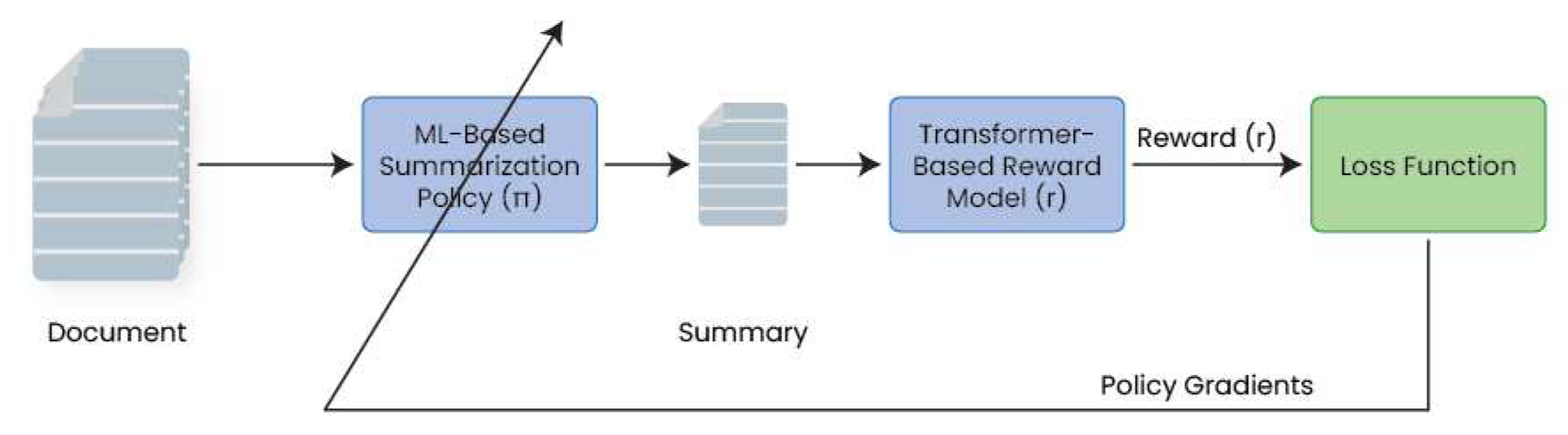

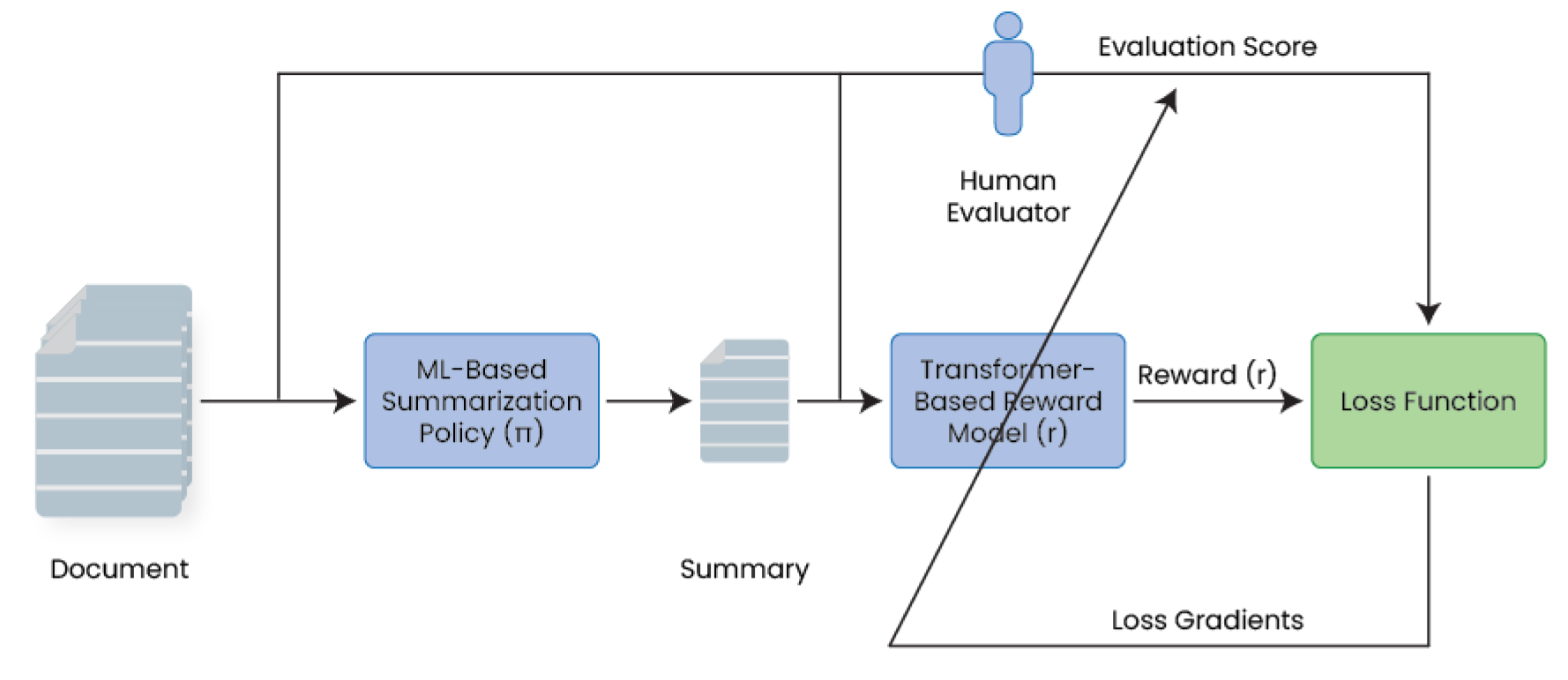

2.2.2. State-of-the-Art Related to RLHF-Based Dialogue Systems

3. ChatGPT Competitors

3.1. Google Bard

3.2. Chatsonic

3.3. Jasper Chat

3.4. OpenAI Playground

3.5. Caktus AI

3.6. Replika

3.7. Chai AI

3.8. Neeva AI

3.9. Rytr

3.10. PepperType

4. Applications of ChatGPT

4.1. Natural Language Processing

| Reference | Main Contributions | Strengths | Shortcomings |

|---|---|---|---|

| [34] |

|

|

|

| [35] |

|

|

|

| [39] |

|

|

|

| [40] |

|

|

|

| [41] |

|

|

|

| [42] |

|

|

|

| [43] |

|

|

|

| [38] |

|

|

|

4.2. Healthcare

| Reference | Main Contributions | Strengths | Shortcomings |

|---|---|---|---|

| [45] |

|

|

|

| [3] |

|

|

|

| [46] |

|

|

|

| [51] |

|

|

|

| [53] |

|

|

|

4.3. Ethics

| Reference | Main Contributions | Strengths | Shortcomings |

|---|---|---|---|

| [55] |

|

|

|

| [56] |

|

|

|

| [57] |

|

|

|

4.4. Education

| Reference | Main Contributions | Strengths | Shortcomings |

|---|---|---|---|

| [4] |

|

|

|

| [58] |

|

|

|

| [59] |

|

|

|

| [60] |

|

|

|

4.5. Industry

| Reference | Main Contributions | Strengths | Shortcomings |

|---|---|---|---|

| [64] |

|

|

|

| [63] |

|

|

|

| [66] |

|

|

|

5. Challenges and Future Directions

5.1. Challenges

-

Data Privacy and Ethics: The challenge of Data Privacy and Ethics for ChatGPT is complex and multifaceted. One aspect of this challenge is related to data privacy, which involves protecting personal information collected by ChatGPT. ChatGPT relies on vast amounts of data to train its language model, which often includes sensitive user information, such as chat logs and personal details. Therefore, ensuring that user data is kept private and secure is essential to maintain user trust in the technology [67,68].Another aspect of the Data Privacy and Ethics challenge for ChatGPT is related to ethical considerations. ChatGPT has the potential to be used in various applications, including social media, online communication, and customer service. However, the technology’s capabilities also pose ethical concerns, particularly in areas such as spreading false information and manipulating individuals [69,70]. The potential for ChatGPT to be used maliciously highlights the need for ethical considerations in its development and deployment.To address these challenges, researchers and developers need to implement robust data privacy and security measures in the design and development of ChatGPT. This includes encryption, data anonymization, and access control mechanisms. Additionally, ethical considerations should be integrated into the development process, such as developing guidelines for appropriate use and ensuring technology deployment transparency. By taking these steps, the development and deployment of ChatGPT can proceed ethically and responsibly, safeguarding users’ privacy and security while promoting its positive impact.

-

Bias and Fairness: Bias and fairness are critical issues related to developing and deploying chatbot systems like ChatGPT. Bias refers to the systematic and unfair treatment of individuals or groups based on their personal characteristics, such as race, gender, or religion. In chatbots, bias can occur in several ways [71,72]. For example, biased language models can lead to biased responses that perpetuate stereotypes or discriminate against certain groups. Biased training data can also result in a chatbot system that provides inaccurate or incomplete information to users.Fairness, on the other hand, relates to treating all users equally without discrimination. Chatbots like ChatGPT must be developed and deployed in a way that promotes fairness and prevents discrimination. For instance, a chatbot must provide equal access to information or services, regardless of the user’s background or personal characteristics.To address bias and fairness concerns, developers of chatbots like ChatGPT must use unbiased training data and language models. Additionally, the chatbot system must be regularly monitored and audited to identify and address any potential biases. Fairness can be promoted by ensuring that the chatbot system provides equal access to information or services and does not discriminate against any particular group. The development and deployment of chatbots must be done with a clear understanding of the ethical considerations and a commitment to uphold principles of fairness and non-discrimination.

- Robustness and Explainability: Robustness and explainability are two critical challenges that must be addressed when deploying ChatGPT in real-world applications [7].

5.2. Future Directions

- Multilingual Language Processing: Multilingual Language Processing is a crucial area for future work related to ChatGPT [35]. Despite ChatGPT’s impressive performance in English language processing, its effectiveness in multilingual contexts is still an area of exploration. To address this, researchers may explore ways to develop and fine-tune ChatGPT models for different languages and domains and investigate cross-lingual transfer learning techniques to improve the generalization ability of ChatGPT. Additionally, future work in multilingual language processing for ChatGPT may focus on developing multilingual conversational agents that can communicate with users in different languages. This may involve addressing challenges such as code-switching, where users may switch between languages within a single conversation. Furthermore, research in multilingual language processing for ChatGPT may also investigate ways to improve the model’s handling of low-resource languages, which may have limited training data available.

-

Low-Resource Language Processing: One of the future works for ChatGPT is to extend its capabilities to low-resource language processing. This is particularly important as a significant portion of the world’s population speaks low-resource languages with limited amounts of labeled data for training machine learning models. Therefore, developing ChatGPT models that can effectively process low-resource languages could have significant implications for enabling communication and access to information in these communities.To achieve this goal, researchers can explore several approaches. One possible solution is to develop pretraining techniques that can learn from limited amounts of data, such as transfer learning, domain adaptation, and cross-lingual learning. Another approach is to develop new data augmentation techniques that can generate synthetic data to supplement the limited labeled data available for low-resource languages. Additionally, researchers can investigate new evaluation metrics and benchmarks that are specific to low-resource languages.Developing ChatGPT models that can effectively process low-resource languages is a crucial area of research for the future. It has the potential to enable access to information and communication for communities that have been historically marginalized due to language barriers.

- Domain-Specific Language Processing: Domain-specific language processing refers to developing and applying language models trained on text data from specific domains or industries, such as healthcare, finance, or law. ChatGPT, with its remarkable capabilities in natural language processing, has the potential to be applied to various domains and industries to improve communication, decision-making, and automation.

6. Conclusions

Funding

References

- A. S. George and A. H. George, “A review of chatgpt ai’s impact on several business sectors,” Partners Universal International Innovation Journal, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 9–23, 2023.

- M. Verma, “Integration of ai-based chatbot (chatgpt) and supply chain management solution to enhance tracking and queries response.

- K. Jeblick, B. Schachtner, J. Dexl, A. Mittermeier, A. T. Stüber, J. Topalis, T. Weber, P. Wesp, B. Sabel, J. Ricke et al., “Chatgpt makes medicine easy to swallow: An exploratory case study on simplified radiology reports,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.14882, 2022.

- S. Frieder, L. Pinchetti, R.-R. Griffiths, T. Salvatori, T. Lukasiewicz, P. C. Petersen, A. Chevalier, and J. Berner, “Mathematical capabilities of chatgpt,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2301.13867, 2023.

- S. Shahriar and K. Hayawi, “Let’s have a chat! a conversation with chatgpt: Technology, applications, and limitations,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.13817, 2023.

- A. Lecler, L. Duron, and P. Soyer, “Revolutionizing radiology with gpt-based models: Current applications, future possibilities and limitations of chatgpt,” Diagnostic and Interventional Imaging, 2023.

- R. Omar, O. Mangukiya, P. Kalnis, and E. Mansour, “Chatgpt versus traditional question answering for knowledge graphs: Current status and future directions towards knowledge graph chatbots,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.06466, 2023. C.

- A. Haleem, M. Javaid, and R. P. Singh, “An era of chatgpt as a significant futuristic support tool: A study on features, abilities, and challenges,” BenchCouncil Transactions on Benchmarks, Standards and Evaluations, p. 100089, 2023.

- T. B. Brown, B. Mann, N. Ryder, M. Subbiah, J. Kaplan, P. Dhariwal, A. Neelakantan, P. Shyam, G. Sastry, A. Askell, S. Agarwal, A. Herbert-Voss, G. Krueger, T. Henighan, R. Child, A. Ramesh, D. M. Ziegler, J. Wu, C. Winter, C. Hesse, M. Chen, E. Sigler, M. Litwin, S. Gray, B. Chess, J. Clark, C. Berner, S. McCandlish, A. Radford, I. Sutskever, and D. Amodei, “Language models are few-shot learners,” CoRR, vol. abs/2005.14165, 2020.

- A. Vaswani, N. Shazeer, N. Parmar, J. Uszkoreit, L. Jones, A. N. Gomez, L. u. Kaiser, and I. Polosukhin, “Attention is all you need,” in Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, I. Guyon, U. V. Luxburg, S. Bengio, H. Wallach, R. Fergus, S. Vishwanathan, and R. Garnett, Eds., vol. 30. Curran Associates, Inc., 2017. [Online]. Available online: https://proceedings.neurips.cc/paper/2017/file/3f5ee243547dee91fbd053c1c4a845aa-Paper.pdf.

- J. Devlin, M.-W. Chang, K. Lee, and K. Toutanova, “Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.04805, 2018.

- A. Radford, K. Narasimhan, T. Salimans, and I. Sutskever, “Improving language understanding by generative pre-training,” URL https://s3-us-west-2. amazonaws. com/openai-assets/researchcovers/languageunsupervised/language_understanding_paper. pdf, 2018.

- P. F. Christiano, J. Leike, T. Brown, M. Martic, S. Legg, and D. Amodei, “Deep reinforcement learning from human preferences,” Advances in neural information processing systems, vol. 30, 2017.

- L. Ouyang, J. Wu, X. Jiang, D. Almeida, C. L. Wainwright, P. Mishkin, C. Zhang, S. Agarwal, K. Slama, A. Ray, J. Schulman, J. Hilton, F. Kelton, L. Miller, M. Simens, A. Askell, P. Welinder, P. Christiano, J. Leike, and R. Lowe, “Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback,” 2022.

- H. H. Thorp, “Chatgpt is fun, but not an author,” Science, vol. 379, no. 6630, pp. 313–313, 2023.

- R. S. Sutton and A. G. Barto, Reinforcement learning: An introduction. MIT press, 2018.

- J. Ho and S. Ermon, “Generative adversarial imitation learning,” Advances in neural information processing systems, vol. 29, 2016.

- J. Schulman, S. Levine, P. Abbeel, M. Jordan, and P. Moritz, “Trust region policy optimization,” in International conference on machine learning, 2015, pp. 1889–1897.

- V. Mnih, A. P. Badia, M. Mirza, A. Graves, T. Lillicrap, T. Harley, D. Silver, and K. Kavukcuoglu, “Asynchronous methods for deep reinforcement learning,” in International conference on machine learning, 2016, pp. 1928–1937.

- J. Schulman, F. Wolski, P. Dhariwal, A. Radford, and O. Klimov, “Proximal policy optimization algorithms,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1707.06347, 2017.

- Y. Wang, H. He, and X. Tan, “Truly proximal policy optimization,” in Uncertainty in Artificial Intelligence. PMLR, 2020, pp. 113–122.

- A. Glaese, N. McAleese, M. Trębacz, J. Aslanides, V. Firoiu, T. Ewalds, M. Rauh, L. Weidinger, M. Chadwick, P. Thacker et al., “Improving alignment of dialogue agents via targeted human judgements,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.14375, 2022.

- Y. Bai, A. Jones, K. Ndousse, A. Askell, A. Chen, N. DasSarma, D. Drain, S. Fort, D. Ganguli, T. Henighan et al., “Training a helpful and harmless assistant with reinforcement learning from human feedback,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.05862, 2022.

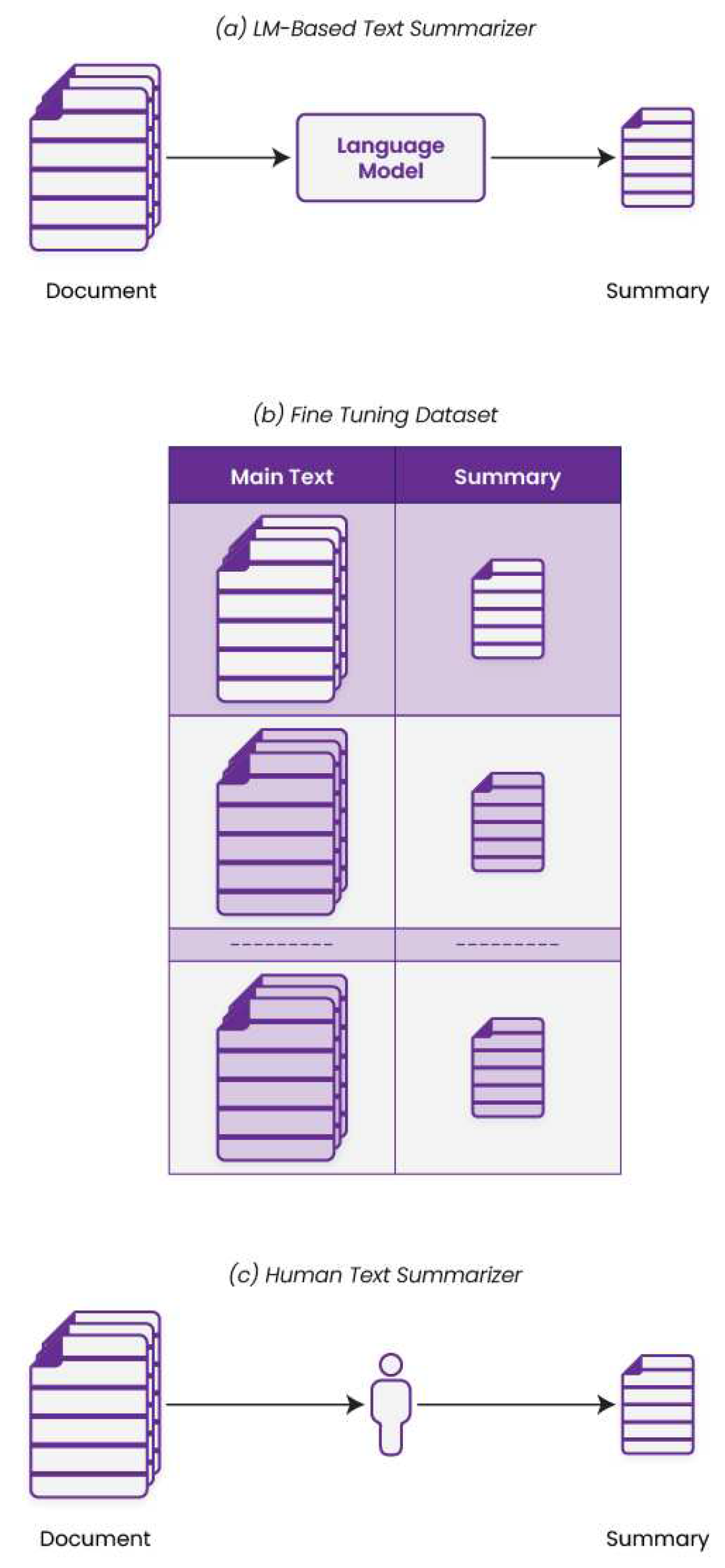

- N. Stiennon, L. Ouyang, J. Wu, D. Ziegler, R. Lowe, C. Voss, A. Radford, D. Amodei, and P. F. Christiano, “Learning to summarize with human feedback,” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 33, pp. 3008–3021, 2020.

- V. Malhotra, “Google introduces bard ai as a rival to chatgpt,” 2023, https://beebom.com/google-bard-chatgpt-rival-introduced/.

- S. Garg, “What is chatsonic, and how to use it?” 2023, https://writesonic.com/blog/what-is-chatsonic/.

- Jasper, “Jasper chat - ai chat assistant,” 2023, https://www.jasper.ai/.

- OpenAI, “Welcome to openai,” 2023, https://platform.openai.com/overview.

- C. AI, “Caktus - open writing with ai,” 2023, https://www.caktus.ai/caktus_student/.

- E. Kuyda, “What is chatsonic, and how to use it?” 2023, https://help.replika.com/hc/en-us/articles/115001070951-What-is-Replika-.

- C. Research, “Chai gpt - ai more human, less filters,” 2023, https://www.chai-research.com/.

- Rytr, “Rytr - take your writing assistant,” 2023, https://rytr.me/.

- Peppertype.ai, “Peppertype.ai - your virtual content assistant,” 2023, https://www.peppertype.ai/.

- B. Guo, X. Zhang, Z. Wang, M. Jiang, J. Nie, Y. Ding, J. Yue, and Y. Wu, “How close is chatgpt to human experts? comparison corpus, evaluation, and detection,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2301.07597, 2023.

- Y. Bang, S. Cahyawijaya, N. Lee, W. Dai, D. Su, B. Wilie, H. Lovenia, Z. Ji, T. Yu, W. Chung et al., “A multitask, multilingual, multimodal evaluation of chatgpt on reasoning, hallucination, and interactivity,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.04023, 2023.

- N. Muennighoff, “Sgpt: Gpt sentence embeddings for semantic search,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2202.08904, 2022.

- C. Zhou, Q. Li, C. Li, J. Yu, Y. Liu, G. Wang, K. Zhang, C. Ji, Q. Yan, L. He et al., “A comprehensive survey on pretrained foundation models: A history from bert to chatgpt,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.09419, 2023.

- C. Qin, A. Zhang, Z. Zhang, J. Chen, M. Yasunaga, and D. Yang, “Is chatgpt a general-purpose natural language processing task solver?” arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.06476, 2023.

- M. Ortega-Martín, Ó. García-Sierra, A. Ardoiz, J. Álvarez, J. C. Armenteros, and A. Alonso, “Linguistic ambiguity analysis in chatgpt,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.06426, 2023.

- A. Borji, “A categorical archive of chatgpt failures,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.03494, 2023.

- X. Yang, Y. Li, X. Zhang, H. Chen, and W. Cheng, “Exploring the limits of chatgpt for query or aspect-based text summarization,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.08081, 2023.

- W. Jiao, W. Wang, J.-t. Huang, X. Wang, and Z. Tu, “Is chatgpt a good translator? a preliminary study,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2301.08745, 2023.

- J. Kocoń, I. Cichecki, O. Kaszyca, M. Kochanek, D. Szydło, J. Baran, J. Bielaniewicz, M. Gruza, A. Janz, K. Kanclerz et al., “Chatgpt: Jack of all trades, master of none,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.10724, 2023.

- D. L. Mann, “Artificial intelligence discusses the role of artificial intelligence in translational medicine: A jacc: Basic to translational science interview with chatgpt,” Basic to Translational Science, 2023.

- F. Antaki, S. Touma, D. Milad, J. El-Khoury, and R. Duval, “Evaluating the performance of chatgpt in ophthalmology: An analysis of its successes and shortcomings,” medRxiv, pp. 2023–01, 2023.

- T. H. Kung, M. Cheatham, A. Medenilla, C. Sillos, L. De Leon, C. Elepaño, M. Madriaga, R. Aggabao, G. Diaz-Candido, J. Maningo et al., “Performance of chatgpt on usmle: Potential for ai-assisted medical education using large language models,” PLOS Digital Health, vol. 2, no. 2, p. e0000198, 2023.

- J. Dahmen, M. Kayaalp, M. Ollivier, A. Pareek, M. T. Hirschmann, J. Karlsson, and P. W. Winkler, “Artificial intelligence bot chatgpt in medical research: the potential game changer as a double-edged sword,” pp. 1–3, 2023.

- M. R. King, “The future of ai in medicine: a perspective from a chatbot,” Annals of Biomedical Engineering, pp. 1–5, 2022.

- K. Bhattacharya, A. S. Bhattacharya, N. Bhattacharya, V. D. Yagnik, P. Garg, and S. Kumar, “Chatgpt in surgical practice—a new kid on the block,” Indian Journal of Surgery, pp. 1–4, 2023.

- T. B. Arif, U. Munaf, and I. Ul-Haque, “The future of medical education and research: Is chatgpt a blessing or blight in disguise?” p. 2181052, 2023.

- L. B. Anderson, D. Kanneganti, M. B. Houk, R. H. Holm, and T. R. Smith, “Generative ai as a tool for environmental health research translation,” medRxiv, pp. 2023–02, 2023.

- N. Kurian, J. Cherian, N. Sudharson, K. Varghese, and S. Wadhwa, “Ai is now everywhere,” British Dental Journal, vol. 234, no. 2, pp. 72–72, 2023.

- S. Wang, H. Scells, B. Koopman, and G. Zuccon, “Can chatgpt write a good boolean query for systematic review literature search?” arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.03495, 2023.

- A. Graf and R. E. Bernardi, “Chatgpt in research: Balancing ethics, transparency and advancement.” Neuroscience, pp. S0306–4522, 2023.

- P. Hacker, A. Engel, and M. Mauer, “Regulating chatgpt and other large generative ai models,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.02337, 2023.

- M. Khalil and E. Er, “Will chatgpt get you caught? rethinking of plagiarism detection,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.04335, 2023.

- T. Y. Zhuo, Y. Huang, C. Chen, and Z. Xing, “Exploring ai ethics of chatgpt: A diagnostic analysis,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2301.12867, 2023.

- X. Chen, “Chatgpt and its possible impact on library reference services,” Internet Reference Services Quarterly, pp. 1–9, 2023.

- T. Susnjak, “Chatgpt: The end of online exam integrity?” arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.09292, 2022.

- A. Tlili, B. Shehata, M. A. Adarkwah, A. Bozkurt, D. T. Hickey, R. Huang, and B. Agyemang, “What if the devil is my guardian angel: Chatgpt as a case study of using chatbots in education,” Smart Learning Environments, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 1–24, 2023.

- M. Salvagno, F. S. Taccone, A. G. Gerli et al., “Can artificial intelligence help for scientific writing?” Critical Care, vol. 27, no. 1, pp. 1–5, 2023.

- M. R. King and chatGPT, “A conversation on artificial intelligence, chatbots, and plagiarism in higher education,” Cellular and Molecular Bioengineering, pp. 1–2, 2023.

- S. A. Prieto, E. T. Mengiste, and B. G. de Soto, “Investigating the use of chatgpt for the scheduling of construction projects,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.02805, 2023.

- M. Dowling and B. Lucey, “Chatgpt for (finance) research: The bananarama conjecture,” Finance Research Letters, p. 103662, 2023.

- R. Gozalo-Brizuela and E. C. Garrido-Merchan, “Chatgpt is not all you need. a state of the art review of large generative ai models,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2301.04655, 2023.

- A. Baki Kocaballi, “Conversational ai-powered design: Chatgpt as designer, user, and product,” arXiv e-prints, pp. arXiv–2302, 2023.

- H. Harkous, K. Fawaz, K. G. Shin, and K. Aberer, “Pribots: Conversational privacy with chatbots,” in Workshop on the Future of Privacy Notices and Indicators, at the Twelfth Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security, SOUPS 2016, no. CONF, 2016.

- M. Hasal, J. Nowaková, K. Ahmed Saghair, H. Abdulla, V. Snášel, and L. Ogiela, “Chatbots: Security, privacy, data protection, and social aspects,” Concurrency and Computation: Practice and Experience, vol. 33, no. 19, p. e6426, 2021.

- E. Ruane, A. Birhane, and A. Ventresque, “Conversational ai: Social and ethical considerations.” in AICS, 2019, pp. 104–115.

- N. Park, K.N. Park, K. Jang, S. Cho, and J. Choi, “Use of offensive language in human-artificial intelligence chatbot interaction: The effects of ethical ideology, social competence, and perceived humanlikeness,” Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 121, p. 106795, 2021.

- H. Beattie, L. Watkins, W. H. Robinson, A. Rubin, and S. Watkins, “Measuring and mitigating bias in ai-chatbots,” in 2022 IEEE International Conference on Assured Autonomy (ICAA). IEEE, 2022, pp. 117–123.

- Y. K. Dwivedi, N. Kshetri, L. Hughes, E. L. Slade, A. Jeyaraj, A. K. Kar, A. M. Baabdullah, A. Koohang, V. Raghavan, M. Ahuja et al., ““so what if chatgpt wrote it?” multidisciplinary perspectives on opportunities, challenges and implications of generative conversational ai for research, practice and policy,” International Journal of Information Management, vol. 71, p. 102642, 2023.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).