Introduction

Across the Abrahamic traditions, figures later recognized as prophets were rarely accepted at the time they appeared. The historical record is consistent on this point. Prophets were ignored, resisted, mocked, or persecuted while alive, and only later were their words preserved, authorized, and absorbed into religious canon. Recognition, when it came, followed disruption rather than preceding it, a pattern noted repeatedly in both scriptural narrative and historical analysis (Weber, 1978). Existing scholarship tends to approach this problem indirectly. Prophets are studied theologically, textually, or historically after canonization has already occurred, while episodes of rejection are treated as narrative features rather than as indicators of a broader recognition mechanism. Authority is examined once it is established, not while it’s contested. As a result, rejection is described, but the structural conditions that reliably produce it are not systematically analyzed (Merton, 1968).

This paper asks whether the conditions that produced recognition failure in the past remain operative today. Specifically, it examines whether contemporary expectation frameworks align with the traits historically present at recognition time, or whether those frameworks have shifted in ways that systematically exclude the very profiles they later come to endorse. The central claim examined here is that contemporary recognition tools operate in ways inverted relative to historical precedent. Traits that accompanied recognition at origin are treated as disqualifying, while traits that appeared only after authority was established are treated as prerequisites, a pattern consistent with broader dynamics of post hoc legitimacy formation (Kuhn, 1962). The scope of the analysis is deliberately limited. The paper examines only figures canonically recognized across Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, using crosstraditional agreement as a methodological boundary rather than a theological judgment. The aim is not to evaluate truth claims, assert prophetic continuation, or identify present figures, but to reconstruct a recognition time profile from shared historical cases and to compare that profile to contemporary expectations.

The paper proceeds by establishing a conceptual framework that distinguishes prophetic recognition from related categories, outlining the methodological approach used to reconstruct recognition time traits, examining the historical record to identify a consistent profile across canonical cases, and analyzing contemporary expectation frameworks to show how recognition filters have inverted. The discussion considers the implications of this inversion for recognition systems more broadly, and the conclusion summarizes the findings without prescribing outcomes.

Framework

This paper relies on a small set of distinctions that are often blurred in religious discussion but are necessary for understanding how recognition operates. When different roles are collapsed into one, expectations drift away from how authority historically appeared and toward traits that only emerge after legitimacy has already been secured. Work in the sociology of knowledge has long noted that once beliefs or authorities stabilize, their origins are rewritten to appear inevitable rather than contested (Berger and Luckmann, 1966).

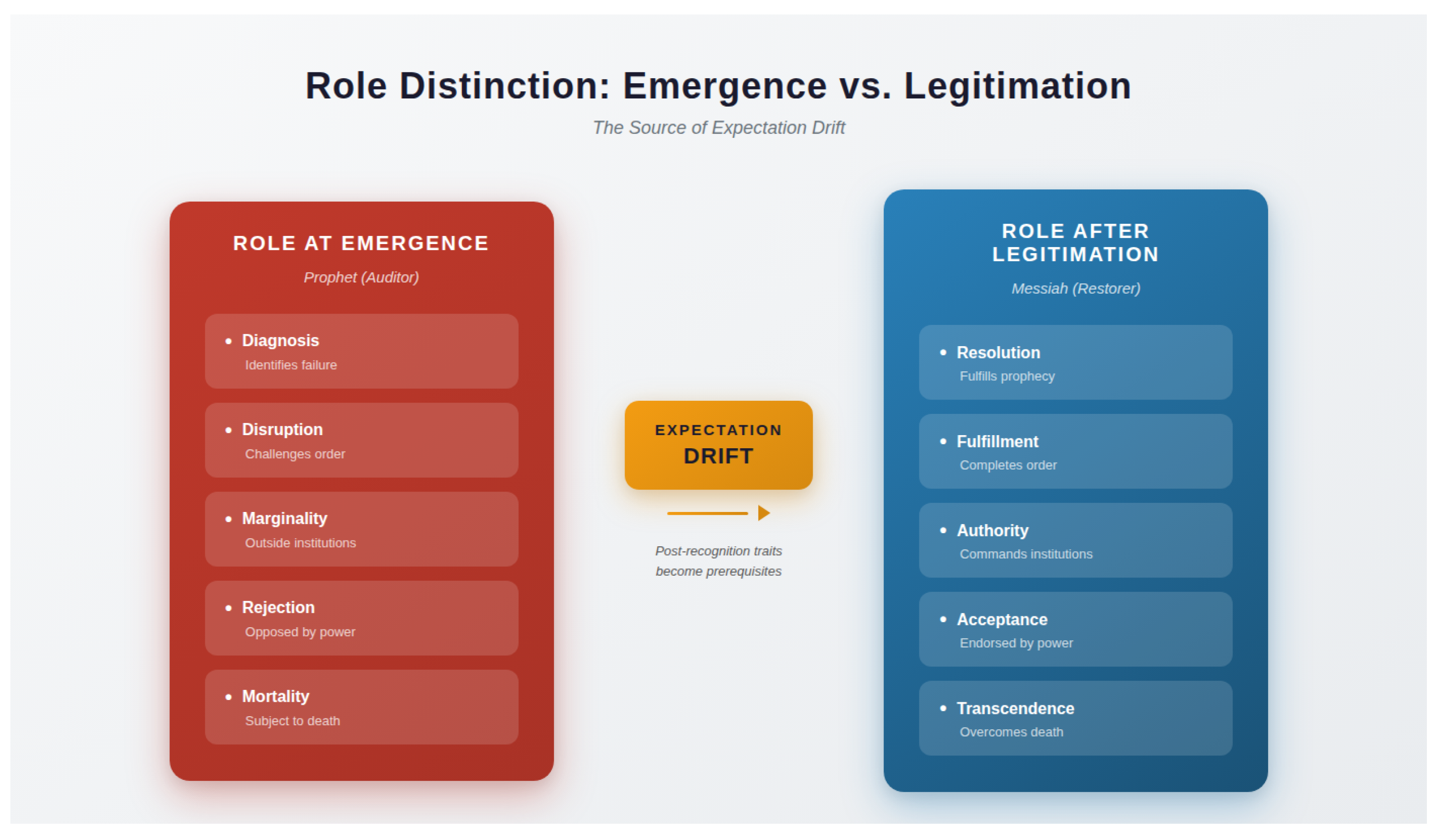

Within this framework, a prophet is treated as an auditor. The role of the prophet is to identify moral failure within existing structures of power, not to resolve history or to establish lasting political order. Prophetic speech is disruptive by nature and tends to move upward, confronting institutions rather than affirming them. This diagnostic function stands in contrast to figures whose primary role is restoration. A messiah is oriented toward resolution, whether political or eschatological, and is associated with fulfillment rather than critique. A founder-leader occupies a different role entirely, centered on organizing followers, building institutions, and stabilizing authority over time. Confusing these roles leads to misplaced expectations, where traits associated with restoration or institution-building are applied to the moment of prophetic emergence, even though they historically appear later.

Several key terms are used consistently throughout the analysis. Recognition time traits refer to characteristics visible when a figure first appears and is judged by contemporaries, before authority or acceptance has formed. Post-recognition traits refer to attributes emphasized after legitimacy has been established through canonization, institutional endorsement, or collective memory. Expectation drift describes the process by which post-recognition traits are gradually mistaken for recognition time requirements, a pattern consistent with studies of how authority is naturalized after the fact (Bourdieu, 1991). Filter inversion names the outcome of this process, where traits that historically accompanied recognition are treated as reasons for dismissal, while traits that historically followed recognition are treated as prerequisites. Canonical recognition refers to crosstraditional agreement on a figure’s status and is used here as a methodological boundary rather than a theological claim.

This framework does not argue for how recognition ought to occur, nor does it prescribe responses by religious traditions. Its purpose is limited to providing clear terms for comparing how recognition historically unfolded with how legitimacy is currently assessed, allowing structural misalignment to be identified without appealing to belief, revelation, or authority claims. These distinctions are not theoretical background alone; they define the method used in the analysis that follows. This paper uses a constrained comparative method to examine how prophetic recognition has historically occurred and how contemporary expectation frameworks differ from that pattern. The method is descriptive and structural, not theological or normative. The scope of analysis is limited to figures recognized as prophets across Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. This boundary is methodological rather than evaluative. Crosstraditional recognition functions as a reliability filter, reducing the influence of internal doctrinal expansion or later tradition-building within any single community. Figures central to only one tradition are excluded not because of judgment about their significance, but because they do not meet the cross-recognition criterion required for comparative stability.

The primary data sources are scriptural texts and historically grounded scholarship that reconstructs the social context, reception, and self-understanding of prophetic figures. Scriptural material is treated as historical evidence for how figures were presented and received, not as proof of metaphysical claims. Historical and comparative studies are used to clarify social position, institutional response, and timing of recognition (Collins, 2019). Crosstraditional agreement is used as an additional reliability check. Where communities that differ sharply in doctrine nevertheless agree on lineage, identity, and role attribution, this agreement is treated as a strong indicator that the pattern under examination is not an artifact of a single tradition’s theology (Silverstein, 2010). The analytical approach proceeds in three steps. First, recognition time traits are reconstructed by examining what is visible at the moment prophetic figures first appear in the historical record, before authority, canonization, or institutional validation have formed. Second, these traits are compared to contemporary expectation frameworks drawn from religious discourse, education, and popular representation. A full empirical survey of contemporary recognition expectations lies outside the scope of this analysis; the comparison is structural rather than sociological. Third, points of alignment and misalignment are identified, with particular attention to traits that historically accompanied recognition but are now treated as disqualifying. This methodology does not claim that prophetic activity continues, that it has ceased, or that any present individual fits the reconstructed profile. It does not identify candidates, issue predictions, or adjudicate theological truth. Its sole purpose is to evaluate whether contemporary recognition frameworks remain structurally capable of detecting the profile their own histories record (Smith, 2004). With the analytical framework established, the next step is to examine how prophetic recognition appears in the shared historical record.

This section reconstructs a recognition time profile from figures treated as prophets within the shared Abrahamic canon. The purpose is structural description, not theological evaluation. The analysis asks what traits are present at the point where recognition first begins, before authority, institutional adoption, or retrospective interpretation reshape the figure’s public meaning. If a consistent profile appears across the shared record, that profile can serve as a baseline for evaluating contemporary recognition frameworks. The methodological boundary is crosstraditional recognition. Only figures treated as prophets within Judaism, Christianity, and Islam are used as the primary dataset. This restriction is not a claim about prophetic validity outside this set. It serves as a control that limits disagreement over canon and prevents the analysis from collapsing into inter-traditional adjudication. These figures are not selected for representativeness but for maximal crosstraditional agreement, which minimizes interpretive dispute at the cost of breadth. Scholars widely recognize that prophetic texts emerge from social conflict and are later reinterpreted through institutional memory, which makes reconstruction of early reception both difficult and necessary (Sharp, 2016; Barton, 2019).

Moses

Moses was born into slavery, raised in ambiguous cultural position, and fled Egypt after killing an overseer. When called at the burning bush, his response was refusal: "Please send someone else" (Exodus 4:13). He cited lack of eloquence and requested a replacement. God appointed Aaron to assist, but the reluctance is preserved in the text without apology. Upon returning to Egypt, Moses faced rejection from Pharaoh and resistance from the Israelites themselves. Even after the Exodus, the people "constantly grumbled against Moses" during the desert period (Numbers 14:2), and he endured multiple rebellions including the golden calf incident and Korah’s challenge to his authority. Moses died before entering the promised land. His status as the preeminent prophet of Judaism was secured only by later generations, who canonized his writings and elevated him to a position he never claimed during his lifetime. He is now "considered the most important prophet in Judaism" and is highly esteemed in Christianity and Islam, but this recognition is entirely posthumous in its full form.

Elijah

Elijah appeared from rural obscurity, identified only as "the Tishbite from Gilead" (1 Kings 17:1). He held no institutional office and emerged from no prophetic school. His ministry consisted of direct confrontation with royal power, specifically King Ahab and Queen Jezebel, who had promoted Baal worship throughout Israel. Elijah’s public contest against the prophets of Baal on Mount Carmel produced a dramatic result, but national repentance did not follow. Instead, Jezebel issued a death warrant, and Elijah fled into the wilderness, where he asked God to take his life (1 Kings 19:4). He described himself as alone, the only faithful one remaining. His departure from the earth, taken up in a whirlwind, was witnessed only by his successor Elisha. Recognition of Elijah’s significance came later, when Malachi prophesied his return before the "great and dreadful day of the Lord" (Malachi 4:5). He became a central figure in Jewish eschatology, honored in later Jewish tradition at Passover with an empty chair, and acknowledged in Christianity and Islam as a great prophet. But during his active ministry, he was hunted, despairing, and largely ignored by the nation he was sent to address.

Jeremiah

Jeremiah was called as a young man and immediately resisted: "I do not know how to speak; I am too young" (Jeremiah 1:6). God overruled the objection, but the reluctance is recorded without revision. Jeremiah’s ministry spanned the final decades of the Kingdom of Judah, during which he delivered repeated warnings of coming destruction. The response was not acceptance but persecution. He was mocked, publicly beaten, placed in stocks, imprisoned multiple times, and thrown into a cistern where he sank into mud and was left to die (Jeremiah 38:6). The king cut up and burned his written scroll (Jeremiah 36:23). Religious leaders, political officials, and the general population rejected his message. Only after Jerusalem fell to Babylon in 586 BCE, exactly as Jeremiah had warned, was his prophetic status vindicated. His writings were preserved and canonized by the very community that had rejected him. Recognition came, but only after catastrophe confirmed what resistance had refused to hear.

Jesus

Jesus emerged from a working-class family in Galilee, identified in the gospels as a carpenter’s son from Nazareth. He held no religious office and operated outside the institutional structures of the Temple and the Sanhedrin. His teaching generated immediate friction with established authorities. The gospels record repeated conflict with Pharisees, Sadducees, and scribes, culminating in a capital trial and execution by crucifixion. Even among those closest to him, recognition was incomplete. Peter denied him three times. The disciples fled at his arrest. On the night before his death, Jesus prayed for the cup to pass from him (Matthew 26:39), a moment of reluctance preserved in the canonical record. Recognition of Jesus as messiah and prophet came after the resurrection accounts and through the missionary work of the early church. The authority now attributed to him was not present during his ministry, when he was an itinerant teacher executed as a criminal. The gospels themselves record that "a prophet is not without honor except in his own town" (Matthew 13:57).

The following diagram represents the recognition sequence observed across canonical prophets. It is not a genealogy or a claim of succession. It is a structural representation of how recognition unfolds relative to emergence and authority. The diagram introduces no new claims; it visualizes relationships already described in text. This process is summarized schematically in

Figure 1.

The shared record yields a consistent recognition time profile. Within the bounded dataset, prophets appear as reluctant figures without early institutional backing, operating from marginal positions, directing moral critique upward at existing power structures, and encountering resistance before later legitimation. This profile is not constructed from marginal or disputed texts. It’s drawn from passages central to each figure’s narrative, preserved by traditions that otherwise disagree sharply on theology.

The pattern can be summarized in five elements:

Lineage: All canonical prophets recognized across the three traditions are males within the lineage tradition identifies as ancestral to the Jewish people. This commonality reflects the scope of crosstraditional agreement rather than a proposed criterion.

Reluctance: Among figures with explicit calling narratives, resistance to the prophetic role is documented at the point of calling.

Marginality: Early legitimacy is not grounded in institutional status or elite social position.

Rejection: Prophetic speech generates friction, not consensus; recognition is delayed.

Posthumous authority: Full legitimation occurs after death, through canonization and institutional adoption.

This profile describes conditions under which recognition historically emerged, not conditions that guarantee legitimacy. The following conditional structure summarizes the analytical move:

If a crosstraditional shared canon exists, it can function as a bounded dataset.

If that dataset contains recurring recognition time traits, a recognition time profile can be stated.

If contemporary frameworks require opposite traits at the point of first appearance, then those frameworks are misaligned with the recorded baseline.

This profile can be reconstructed without asserting prophetic continuation and without identifying any contemporary individuals. Its role in the paper is instrumental. It establishes a baseline against which modern recognition frameworks can be evaluated.

A second structural shift becomes visible after the canonical period closes. Following the canonization of Jesus, traits retrospectively emphasized in gospel narrative miracles, divine spectacle, and cosmic authority begin to function as prerequisites rather than outcomes of recognition. Events preserved in the New Testament, transmitted through later non-Jewish interpretive communities move from post-recognition interpretation to expectation at first appearance. These elements enter the recognition filter not as descriptions of how authority historically emerged, but as requirements imposed in advance:

Virgin birth (Matthew 1:18-25; Luke 1:26-38)

Turning water into wine (John 2:1-11)

Walking on water (Matthew 14:22-33; Mark 6:45-52; John 6:16-21)

These post-recognition traits did not originate within Jewish prophetic tradition itself. This shift is not attributed here to a single doctrinal decision, institutional decree, or intentional effort to prevent future recognition. Rather, it reflects a gradual structural transformation produced by canonization, narrative emphasis, and expectation drift over time. Traits that originally functioned as retrospective markers of authority became normalized through repeated transmission and theological consolidation, eventually operating as implicit prerequisites without being formally defined as such. The analysis therefore identifies a systemic outcome rather than assigning motive, responsibility, or agency to any single community or historical moment. They entered the recognition framework through later interpretive communities operating outside that tradition, as narratives about Jesus circulated in increasingly non-Jewish contexts. In this process, extraordinary elements that functioned as retrospective markers of authority were elevated into normative expectations. The result was an implicit ceiling. Recognition criteria were set at levels that no subsequent figure operating within the historical prophetic pattern could plausibly satisfy. This shift did not merely raise the bar; it transformed recognition into a category defined by exception rather than diagnosis. Recognition became structurally improbable by design rather than by absence. The conceptual distinction between prophetic emergence and post-recognition legitimation is summarized schematically in

Figure 2.

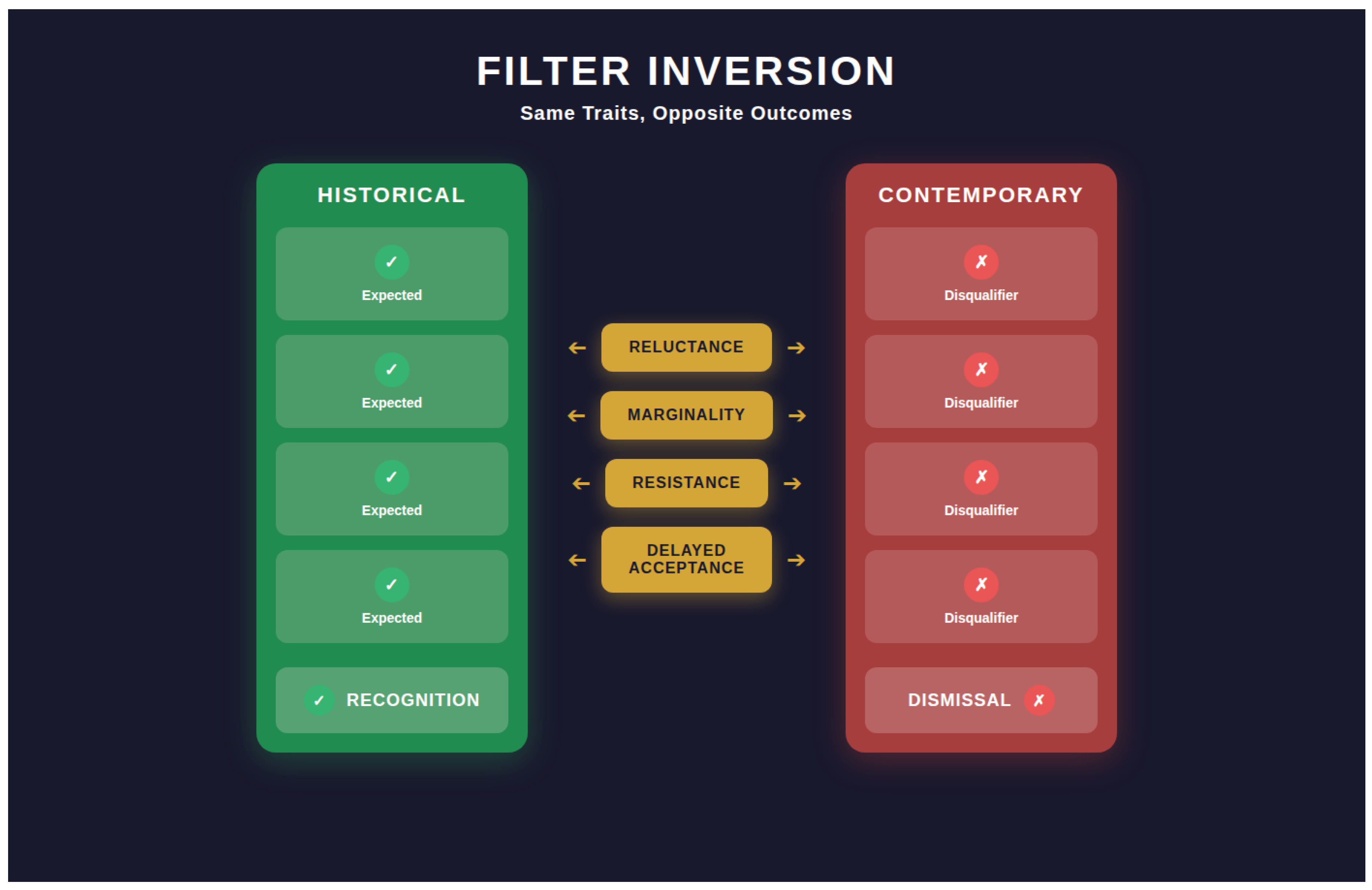

Filter Inversion: The recognition time profile reconstructed in the preceding section describes how prophetic figures historically appeared and how they were initially received. This section examines how recognition is commonly expected to occur in contemporary settings. The focus is not theological belief, but the structural traits that are implicitly treated as prerequisites for legitimacy at first appearance. These expectations can be observed across religious education, institutional discourse, and popular representation. The analysis is descriptive rather than normative and does not assess whether these expectations are justified. When compared directly to the historical baseline, a clear reversal becomes visible. Contemporary expectation frameworks tend to privilege traits associated with authority rather than disruption. Figures are expected to appear with legitimacy already established rather than contested. Institutional affiliation is treated as evidence of credibility rather than as a later outcome. Public recognition is assumed to precede critique instead of following it. Confidence and self-assertion are interpreted as indicators of truth, while hesitation or reluctance is treated as a signal of weakness or fraud. These expectations operate implicitly rather than through formal doctrine.

The following traits are commonly privileged at the point of first appearance:

Institutional authority or formal affiliation

Public legitimacy and broad visibility

Confidence, certainty, and self-assured presentation

Early acceptance rather than resistance

Spectacle or confirmatory signs presented in advance

These traits function as filters. Figures lacking them are dismissed before substantive evaluation occurs. Marginality is interpreted as irrelevance. Conflict is interpreted as failure. Delay in recognition is treated as disconfirmation rather than as a recurring historical feature. This filtering process does not require explicit intent and can operate through habit, pedagogy, and inherited expectation. The origin of these expectations lies in post-recognition narratives rather than recognition time conditions. After authority stabilizes, later retellings emphasize elements that mark power, certainty, and transcendence. Canonization magnifies spectacle because extraordinary elements are more easily preserved, transmitted, and defended. Over time, these elements dominate the narrative while the conditions of early rejection and resistance are compressed or omitted. This narrative compression is a common feature of institutional memory.

As retellings accumulate, authority is projected backward. Recognition appears inevitable rather than contested. The social friction surrounding emergence is reframed as misunderstanding rather than as a defining feature. In this process, miracles and extraordinary signs move from narrative description to implied requirement. What originally functioned as retrospective interpretation becomes an expectation imposed in advance, even when no formal requirement is stated. This shift is not attributed here to a single doctrinal decision or institutional decree. It reflects a gradual structural transformation produced by canonization, repetition, and expectation drift over time. Traits that historically followed recognition are normalized and treated as indicators of legitimacy at first appearance. The analysis identifies a systemic outcome rather than assigning motive, responsibility, or agency to any specific group or historical moment. The result is a recognition filter that no longer aligns with the historical pattern preserved in the shared canonical record.

The outcome of this process is a structural inversion. Recognition time traits documented across canonical prophets now function as disqualifiers. Post-recognition traits are treated as prerequisites. The order preserved in the historical record is reversed:

Reluctance becomes evidence against credibility

Marginality becomes evidence against relevance

Resistance becomes evidence against truth

Delay in acceptance becomes evidence against legitimacy

At the same time:

Authority is expected at first appearance

Acceptance is expected before critique

Spectacle is expected before diagnosis

This inversion does not merely raise the bar for recognition. It renders recognition structurally improbable for any figure operating within the historical prophetic pattern. The framework does not fail because prophetic emergence no longer occurs. It fails because the criteria applied no longer correspond to the profile the traditions themselves preserve. This conclusion follows from structural comparison rather than theological judgment. This section does not argue that recognition should occur differently, that prophecy continues, or that any present individual fits the profile. It establishes only that contemporary expectation frameworks are structurally misaligned with the recognition time conditions recorded in their own histories.

What This Section Does Not Claim

This analysis does not claim that the pattern must continue, that prophecy remains active, or that any present figure fits the profile. It does not evaluate theological truth or prescribe recognition. It observes only that the traditions themselves preserve a consistent recognition time profile, and that this profile can be compared to contemporary expectations without requiring belief in prophetic metaphysics. Rejection is necessary but not sufficient for this profile; many rejected figures remain rejected without subsequent canonization. The presence of recognition time traits does not itself constitute evidence of prophetic status.

The Filtered Profile

The preceding sections established a recognition time profile derived from crosstraditionally recognized prophetic figures and demonstrated a structural shift in how recognition criteria now operate. This section isolates that shift by identifying specific traits that historically accompanied prophetic emergence but are presently treated as disqualifying, alongside traits that historically followed recognition but are now treated as prerequisites. The purpose of this section is not to assess motivation, sincerity, legitimacy, or theological truth claims, nor to attribute intent, deliberation, or agency to any tradition, institution, or community, but to describe how filtering criteria have changed in function as a matter of structural comparison. The analysis proceeds by direct comparison between recognition time conditions preserved in the shared record and contemporary recognition filters as they are commonly applied within institutional, educational, and cultural contexts. Historical reconstruction shows that several traits repeatedly present at the point of prophetic emergence are now interpreted as indicators of inauthenticity, instability, or failure. These traits were not incidental but structurally connected to the prophetic role as it historically appeared, and their contemporary reclassification alters the recognition environment itself rather than the underlying profile being evaluated. This dynamic reflects broader patterns of legitimacy reconstruction observed across institutional contexts (DiMaggio and Powell, 1983).

Reluctance toward authority historically functioned as a recurring feature of prophetic calling narratives. Figures resisted the role, expressed doubt, or attempted withdrawal, not as a rhetorical device but as a recorded reaction to the burden of the task. Moses protested his inadequacy and begged God to send another (Exodus 4:13), while Jeremiah objected that he was too young to speak (Jeremiah 1:6). In contemporary frameworks, reluctance is commonly interpreted as lack of conviction or absence of genuine authority, particularly in environments that associate leadership with assertiveness and confidence (Judge, Bono, Ilies, and Gerhardt, 2002). This reversal transforms reluctance from an expected indicator into a signal of disqualification. Absence of self-promotion similarly functioned as a recognition time trait. Prophetic figures did not market themselves, seek followers through strategic messaging, or frame their role in terms of personal advancement. Their authority, where it emerged, followed confrontation and rejection rather than intentional visibility. Contemporary recognition systems, however, often rely on visibility, branding, and narrative control as proxies for legitimacy (Hearn, 2008). Lack of self-promotion is therefore interpreted not as integrity or restraint, but as evidence of irrelevance or lack of seriousness. Marginal social position was a defining feature of prophetic emergence. Figures operated outside elite institutions, lacked formal credentials, and were frequently positioned at the periphery of economic and political power. Amos explicitly disclaimed prophetic office, stating "I was neither a prophet nor the son of a prophet, but I was a shepherd" (Amos 7:14). This marginality enabled upward moral critique but also produced resistance. In contemporary contexts, marginality is frequently treated as a credibility deficit rather than a structural condition of critique (Collins, 1998). Authority is expected to originate within recognized centers rather than challenge them from outside.

Lack of institutional endorsement likewise functioned historically as a recognition time condition rather than a defect. Prophetic speech preceded validation, and institutional alignment typically followed only after vindication or canonization. Present recognition filters invert this sequence by treating endorsement as a prerequisite rather than an outcome (Meyer and Rowan, 1977). Absence of institutional backing is therefore interpreted as disqualifying rather than provisional. Upward moral audit, defined as critique directed toward existing power structures, historically constituted the core function of prophetic speech. Nathan confronted King David directly over the Bathsheba affair (2 Samuel 12:1-14), and Elijah publicly opposed Ahab and Jezebel at the height of royal power (1 Kings 18-19). This orientation generated conflict and resistance but also defined the role. In contemporary settings, upward critique is often reframed as antagonism, lack of cooperation, or ideological extremism, particularly when it challenges established authorities (Hirschman, 1970). The diagnostic function is thus reinterpreted as a failure of alignment. Social friction and initial rejection were not anomalies but structural features of prophetic emergence. Resistance, hostility, and dismissal preceded later recognition across the shared record. Jesus himself noted this pattern: "A prophet is not without honor except in his own town and in his own home" (Matthew 13:57). Contemporary frameworks, however, frequently treat friction and rejection as indicators of falsehood or failure rather than expected conditions of emergence (Coser, 1956). Early resistance is interpreted as final verdict rather than provisional response.

The inversion of disqualifying traits is accompanied by a parallel elevation of traits that historically followed recognition into present-day prerequisites, a shift that alters the sequence through which legitimacy is assessed. Credentials now function as a primary indicator of authenticity across many recognition systems. Formal education, certification, or institutional affiliation are treated as evidence of authority, despite the absence of such credentials at the point of prophetic emergence in the historical record (Collins, 1979). Credentialing, where it existed historically, followed recognition rather than enabled it. Immediate legitimacy has likewise become an expectation. Contemporary frameworks often assume that valid authority should be recognized quickly, publicly, and without sustained resistance. This assumption contradicts the historical pattern in which recognition was delayed, contested, and frequently posthumous (Heschel, 1962). The expectation of immediate validation therefore filters out profiles that align with the recorded baseline. Public affirmation operates as a reinforcing prerequisite. Popular acceptance, audience size, or visible support is treated as evidence of legitimacy, even though prophetic emergence historically occurred in contexts of minority reception and opposition. The biblical record explicitly notes that prophets spoke to audiences who "have ears but do not hear" (Ezekiel 12:2). Public affirmation thus substitutes consensus for diagnosis.

Confidence is frequently treated as an authenticity marker, with certainty and assertiveness interpreted as indicators of truth (Anderson and Kilduff, 2009). Historical narratives, however, preserve doubt, hesitation, and internal conflict at the point of calling. Elijah, after his greatest public victory, fled into the wilderness and asked God to take his life (1 Kings 19:4). The elevation of confidence into a prerequisite excludes profiles consistent with recorded emergence conditions. Authority itself has become a prerequisite rather than an outcome. Contemporary recognition systems often require demonstrated authority before recognition is extended, creating a circular condition in which authority must precede its own validation (Suchman, 1995). This inversion structurally prevents recognition of figures who lack prior status. Spectacle functions as a final verification mechanism. Extraordinary displays, visible success, or dramatic validation are treated as evidence of legitimacy (Alexander, 2004). While extraordinary events appear in post-recognition narratives, they did not function as entry conditions in the historical record. Their elevation into prerequisites raises recognition thresholds beyond the conditions under which recognition historically occurred.

Taken together, the comparative analysis yields a consistent structural conclusion. Traits that historically preceded recognition within the shared Abrahamic record now function as disqualifiers within contemporary recognition frameworks, while traits that historically followed recognition now function as prerequisites. The result is a filtered profile in which alignment with the historical recognition pattern reduces the probability of recognition rather than increases it. This inversion does not depend on claims about prophetic continuation or cessation. It follows directly from the comparison of preserved recognition time conditions with present filtering criteria. The profile that historically preceded recognition now fails contemporary filters. This inversion is represented schematically in

Figure 3.

Discussion

The analysis developed in the preceding sections indicates that recognition failure, as it appears in contemporary frameworks, is best understood as a structural condition rather than a moral, intellectual, or individual failure. The historical record does not suggest that prophetic figures failed because they lacked sincerity, clarity, or truth, nor does it show that communities rejected them due to careful diagnostic error correction. Instead, recognition failure consistently emerged from the interaction between disruptive diagnostic speech and institutional systems oriented toward stability, a dynamic consistent with broader patterns of institutional resistance to external challenge (Hirschman, 1970). Contemporary recognition breakdowns therefore do not indicate that valid profiles are absent, but that existing systems are not designed to detect them at the point of emergence. Institutions are structurally optimized to detect legitimacy after it has stabilized, not to diagnose disruption while it is occurring (Meyer and Rowan, 1977). Their primary function is to preserve coherence, continuity, and authority within an established order. Diagnostic figures, by contrast, operate by identifying failure within that order. This produces an inherent asymmetry. Systems designed to maintain stability cannot easily accommodate actors whose function is to audit and unsettle them, a tension that reflects the structural incompatibility between institutional maintenance and prophetic diagnosis identified in classical sociological accounts of charismatic authority (Weber, 1978). As a result, rejection is not an anomaly within recognition processes but a predictable outcome of system design. Stability suppresses auditors not because of malice or ignorance, but because systems that fail to suppress destabilizing inputs cease to function as institutions (DiMaggio and Powell, 1983).

No evidence appears in the historical or contemporary record of meaningful redesign of recognition frameworks to correct this structural inversion. The criteria that govern initial recognition remain largely unchanged despite repeated documentation of delayed, contested, and posthumous legitimation across canonical cases (Heschel, 1962). Initial recognition filters continue to prioritize indicators that historically followed recognition rather than preceded it. Credentialing, endorsement, visibility, confidence, and spectacle remain dominant signals, while reluctance, marginality, friction, and resistance remain interpreted as failure modes (Collins, 1979; Suchman, 1995). The conditions that produced historical recognition delay therefore remain fully operative. This persistence has several implications. Post hoc legitimacy detection dominates recognition systems, meaning that authority is primarily identified after it has already been consolidated through institutional, cultural, or narrative reinforcement (Berger and Luckmann, 1966). Canonization further obscures reception history by collapsing early rejection into later affirmation, creating the appearance of inevitable recognition where none existed at the time (Barton, 2019). Confidence increasingly replaces correctness as a signal of authenticity, particularly in environments that associate authority with assertiveness and coherence rather than diagnostic accuracy (Anderson and Kilduff, 2009). The combined effect is a persistent recognition blind spot in which profiles consistent with historical emergence conditions are systematically filtered out.

Expectation frameworks have therefore not merely drifted but have hardened into thresholds that no historical case ever met at the point of recognition. The criteria now applied would have disqualified the very figures whose recognition histories established the canonical baseline. Recognition failure under these conditions is not accidental but is instead a predictable consequence of applying post-recognition attributes as entry requirements, a structural outcome rather than an evaluative judgment. Several clarifications bound this analysis. This analysis does not assert the presence of contemporary prophetic figures, nor does it identify or imply any specific individuals. It does not claim that prophecy continues, that it has ceased, or that recognition ought to occur differently. No normative prescription is offered. The argument is limited to structural comparison between preserved recognition time conditions and contemporary filtering mechanisms. Its sole claim is that existing frameworks are not configured to detect the profiles their own histories record.

Conclusions

This paper has argued that a recognition time profile exists within the shared Abrahamic record and that this profile can be reconstructed with reasonable stability using crosstraditional sources. That profile is characterized by marginality, reluctance, institutional resistance, delayed validation, and posthumous legitimation. These traits appear consistently at the point of emergence across canonical cases and are preserved by traditions that otherwise diverge sharply in theology and doctrine. The analysis further demonstrated that contemporary recognition frameworks operate in inversion relative to this historical pattern. Traits that historically preceded recognition now function as disqualifiers, while traits that historically followed recognition now function as prerequisites. This inversion alters the sequence through which legitimacy is assessed and transforms recognition from a diagnostic process into a retrospective one. Authority is no longer identified through disruption and critique but is instead inferred from stability, endorsement, confidence, and spectacle.

These conditions are not episodic or accidental. The structural features that produced delayed recognition in the historical record remain operative in contemporary frameworks, and no evidence of systematic redesign has been identified. Recognition failure, where it occurs, is therefore best understood as a consequence of filter configuration rather than absence of qualifying profiles. Systems optimized for stability continue to suppress auditors by design, not through error, but through function. This analysis makes no claim about the continuation or cessation of prophecy, identifies no contemporary individuals, and offers no normative prescription. Its contribution is limited to structural comparison. It asks only whether the mechanisms now used to assess legitimacy remain aligned with the conditions under which legitimacy historically emerged. The question is not whether prophetic recognition should occur, but whether existing frameworks are capable of recognizing the profile their own histories record.

References

- Weber, M. Economy and Society; University of California Press, 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Merton, R. K. Social Theory and Social Structure; Free Press, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, T. S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions; University of Chicago Press, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, P. L.; Luckmann, T. The Social Construction of Reality; Anchor Books, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Language and Symbolic Power; Harvard University Press, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, J. J. What Are Biblical Values? What the Bible Says on Key Ethical Issues; Yale University Press, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein, A. J. Islamic History: A Very Short Introduction; Oxford University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

-

The Oxford Handbook of the Prophets; Sharp, Carolyn J., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, John. A History of the Bible: The Story of the World’s Most Influential Book; Viking: New York, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J. Z. Relating Religion: Essays in the Study of Religion; University of Chicago Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- DiMaggio, Paul J.; Powell, Walter W. The Iron Cage Revisited: Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields. American Sociological Review 1983, 48(2), 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Judge, Timothy A.; Bono, Joyce E.; Ilies, Remus; Gerhardt, Megan W. Personality and Leadership: A Qualitative and Quantitative Review. Journal of Applied Psychology 2002, 87(4), 765–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hearn, Alison. ’Meat, Mask, Burden’: Probing the Contours of the Branded Self. Journal of Consumer Culture 2008, 8(2), 197–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, Randall. The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, John W.; Rowan, Brian. Institutionalized Organizations: Formal Structure as Myth and Ceremony. American Journal of Sociology 1977, 83(2), 340–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschman, Albert O. Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Coser, Lewis A. The Functions of Social Conflict; Free Press: Glencoe, IL, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Randall. The Credential Society: An Historical Sociology of Education and Stratification; Academic Press: New York, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Heschel, Abraham Joshua. The Prophets; Harper & Row: New York, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, Cameron; Kilduff, Gavin J. Why Do Dominant Personalities Attain Influence in Face-to-Face Groups? The Competence-Signaling Effects of Trait Dominance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2009, 96(2), 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suchman, Mark C. Managing Legitimacy: Strategic and Institutional Approaches. Academy of Management Review 1995, 20(3), 571–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, Jeffrey C. Cultural Pragmatics: Social Performance Between Ritual and Strategy. Sociological Theory 2004, 22(4), 527–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).